Abstract

Transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes is not simply determined by the DNA sequence, but rather mediated through dynamic chromatin modifications and remodeling. Recent studies have shown that reversible and rapid changes in histone acetylation play an essential role in chromatin modification, induce genome-wide and specific changes in gene expression, and affect a variety of biological processes in response to internal and external signals, such as cell differentiation, growth, development, light, temperature, and abiotic and biotic stresses. Moreover, histone acetylation and deacetylation are associated with RNA interference and other chromatin modifications including DNA and histone methylation. The reversible changes in histone acetylation also contribute to cell cycle regulation and epigenetic silencing of rDNA and redundant genes in response to interspecific hybridization and polyploidy.

Keywords: Histone acetylation, Gene silencing, Epigenetics, Stress, Development, Hybrids, Polyploidy

1. Introduction

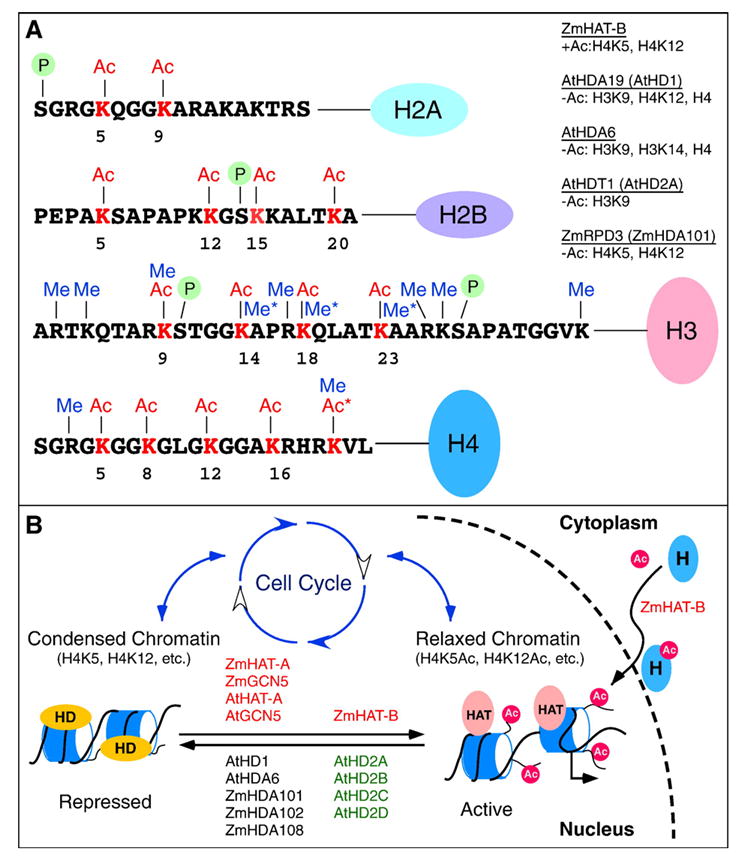

In eukaryotes, the genomic DNA is tightly compacted into a complex structure known as chromatin. Although this compaction enables DNA to be constricted into the limited space of the nucleus, it greatly impedes any biological processes that require access to DNA, such as gene transcription, DNA repair, recombination, and replication [1]. To facilitate cellular activities, the accessibility of chromatin is dynamically regulated during growth and development. Chromatin is comprised by nucleosomes, each of which consists of ~146 bp of DNA wrapped around a histone octamer (two molecules of each of the four core histone proteins, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) [2]. X-ray crystallography has shown that the globular domains of histones are essential for maintaining the structural integrity of nucleosome core particles [3]. The amino-terminal tails protruding from the nucleosomes are responsible for interaction with DNA and thereby facilitate the chromatin assembly via post-translational modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, glycosylation, ADP ribosylation, carbonylation, sumoylation, and biotinylation [4-7] (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Post-translational modifications of core histones and cell cycle control. (A) The modifications include acetylation (Ac, red), methylation (Me, blue), phosphorylation (P in green circle), and ubiquitination (not shown) [13]. In plants, ZmHAT-B has been shown to acetylate specifically lysines (K) 5 and 12 of H4 [27], and the deacetylase ZmRpd3 can specifically deacetylate this distinct acetylation pattern [52,54]. Asterisks indicate plant-specific acetylation of H4 lysine 20 and plant-specific methylation of H3 lysines 14, 18, and 23. Histone H3 lysine-9 can be modified by acetylation and methylation in all plant species investigated. Specific sites of histone acetylation (+Ac) and deacetylation (−Ac) that have been characterized in plants are listed under the histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases, respectively. (B) Histones (marked as H in blue oval circle) are acetylated by type B HAT (e.g., ZmHAT-B) in cytoplasm and transported into nucleus for chromatin assembly. A small circular dashed line indicates the nuclear membrane. Each nucleosome (blue) is wrapped with a DNA strand (black line). The acetylated histones (with HAT in pink circles and Ac in small red circles) are associated with relaxed chromatin and can be subsequently modified by histone deacetylases (HDs, in yellow circles) (e.g., AtHD1 and ZmHDA101, below the arrows) to form condensed chromatin. Acetylation by type A or GCN5-like HATs (e.g., AtGCN5 and ZmGCN5, above the arrows) may revert the condensed chromatin to a relaxed form. ZmHAT-B is localized in nucleus as well as cytoplasm and may possess a function similar to that of type A HATs. Different acetylation patterns (e.g., H4K5Ac and H4K8Ac) and chromatin status may result in reversible changes in gene expression and alternate during cell cycle progression as discussed in the text.

Histone acetylation is dynamic and reversible. It was proposed more than 40 years ago that there is a general correlation between histone acetylation and transcriptional activity [8]. The amino-terminal tails of histones are highly basic due to a high content of lysine and arginine amino acids [9]. The acetylation of conserved lysine residues neutralizes the positive charge of the histone tails and decreases their affinity for negatively charged DNA; thereby promoting the accessibility of chromatin to transcriptional regulators [10]. Alternatively, the “histone code” hypothesis proposes that the combination of different covalent modification states of lysine and/or arginine residues on histone tails, including histone acetylation and methylation, provide signals for recruitment of specific chromatin-associated proteins, which in turn alter chromatin states and affect transcriptional regulation [4,11]. The current review updates the data and views about histone acetylation and deacetylation in plants [12-16] with an emphasis on the roles of histone acetylation in gene expression in response to interspecific hybridization and changes in developmental programs and environmental cues. Readers should also refer to a plethora of data demonstrating the roles of histone acetylation and deacteylation in gene activation, silencing, and disease syndromes that have been extensively reviewed [4,5,10,17-21].

2. Histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases

Histone acetylation and deacetylation are catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDs, HDAs, or HDACs), respectively [10,20,22] (Tables 1 and 2). Many of the studies were carried out in the model organisms Arabidopsis and maize.

Table 1.

Summary of histone acetyltransferases characterized in plants a

| Enzymes | Plants | Associated protein factors | Specificity | Function [reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAT-B (U90274) | Maize | Retinoblastoma associated protein RbAp48 | H4K5, H4K12 | Acetylation of newly synthesized histone H4 during DNA replication [25-27] |

| AtGCN5 (At3g54610) | Arabidopsis | Transcription adaptors ADA2a and ADA2b, transcription factor CBF1 | H3 (H3K9), ADA2a, ADA2b | Activation of cold-regulated genes during cold acclimation, root and shoot differentiation during embryogenesis, developmental effects [32,36,38,40] |

| ZmGCN5 (AJ428540) | Maize | ZmADA2, bZip class transcription factor ZmO2 | H3 | Transcriptional activation [33,37] |

| p300/CBP (PCAT2) (At1g79000) | Arabidopsis | ND | H3, H4, H2A and H2B | [31] |

| TAFII250 (HAF2) (At3g19040) | Arabidopsis | ND | H3 | Integration of light signals to regulate gene expression and growth [108] |

ND: not determined.

Other genes that are predicted to encode histone acetyltransferases and chromatin proteins in Arabidopsis and other plant species can be found at The Plant Chromatin Database (http://www.chromdb.org/).

Table 2.

Summary of histone deacetylases characterized in plants a

| Enzymes | Plants | Associated protein factors | Specificity | Function [reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZmRpd3/101 (AF384032) | Maize | Retinoblastoma-related protein ZmBRB1 ZmRbAp1 | H4K5, H4K12 | Cell cycle progression [50-52,156] |

| ZmRpd3/102 (AF440228) | ||||

| ZmRpd3/108 (AF440226) | ||||

| AtHD1 (AtHDA19) | Arabidopsis | Transcription repressors, AP2/EREBP-type and AtSAP18, an ortholog of human SAP18 | H3K9, H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, H4K16 | Global regulator of plant development, root and shoot differentiation, salt, ABA, and drought stress response, jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling of pathogen response [40,56,58-60,68,69] |

| (At4g38130) | ||||

| AtHDA6 (At5g63110) | Arabidopsis | ND | H3K14, H4K5, H4K12 | Silencing of transgenes, transposable elements, and rDNA [62-67] |

| AtHDA18 (At5g61070) | Arabidopsis | ND | ND | cellular patterning of the root epidermis [72] |

| OsHDAC1 (AF513382) | Rice | ND | H4K5, H4K8, H4K12, H4K16 | Growth rate and plant architecture [61] |

| OsHDAC2 (AF513383) | ||||

| OsHDAC3 (AF513384) | ||||

| ZmHDA1 (AF332918) | Maize | ND | ND | Transcriptional repression [73] |

| AtHD2A (HDT1) | Arabidopsis | ND | H3K9 | Transcriptional repression, seed abortion, rRNA gene silencing nucleolar dominance [74-76,79] |

| (At3g44750) | ||||

| AtHD2B (At5g22650) | Arabidopsis | ND | ND | Transcriptional repression [74,75] |

| AtHD2C (At5g03740) | Arabidopsis | ND | ND | Transcriptional repression, ABA responses [70,74,75] |

| AtHD2D (At2g27840) | Arabidopsis | ND | ND | Transcriptional repression [76] |

| ScHD2 (AY346455) | Potato | ND | ND | Induced expression by fertilization [77] |

| ZmHD2 (U82815) | Maize | ND | H2A, H2B, H3, H4 | [45,52] |

| AtSRT1 (At5g55760) | Arabidopsis | ND | ND | [28] |

| AtSRT2 (At5g09230) | Arabidopsis | ND | ND | [28] |

ND: not determined.

Other genes that are predicted to encode histone deacetylases [28] and chromatin proteins in Arabidopsis and other plant species can be found at The Plant Chromatin Database (http://www.chromdb.org/).

2.1. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs)

HATs are classified into two categories based on their subcellular distribution [20,22] (Table 1). Type B HATs are cytoplasmic proteins that catalyze histone acetylation in cytoplasm, particularly at lysine 5 and 12 of histone H4, prior to histone incorporation into newly replicated chromatin [23,24] (Fig. 1). A type B HAT has been characterized in maize, and it functions as a heterodimeric complex [25,26]. However, maize type B HAT is not only localized in cytoplasm, but also significantly accumulates in nuclei, suggesting that the plant type B HAT has an additional nuclear function [26]. The 50-kDa subunit is the homolog of yeast HAT1 and the 45-kDa subunit is related to the Retinoblastoma associated protein (RbAp) in mammals. Similar to yeast HAT1, the maize type B HAT is highly specific for histone H4 and selectively acetylates lysines 12 and 5 in a sequential manner [27] (Fig. 1A). Sequence analysis also predicts a homolog of the type B HAT in Arabidopsis [28].

The type A HATs are responsible for acetylation of nuclear histones and thus are directly involved in regulating chromatin assembly and gene transcription [29] (Fig. 1B). The type A HATs, including GCN5-related acetyltransferases (GNATs), MYST (for ‘MOZ, Ybf2/Sas3, Sas2 and Tip60)-related HATs, p300/CBP HATs, and the TFIID subunit TAF250, have counterparts in many eukaryotes including plants [28-30]. Mammals have an additional HAT family, the nuclear hormone-related HATs, namely, SRC1 and ACTR (SRC3) that are not present in plants, fungi or other animals. Five p300/CBP-type A HATs are predicted in the Arabidopsis genome [28], and at least one, PCAT2 (p300/CBP acetyltransferase-related protein 2), possesses HAT activity [31].

Arabidopsis and maize GCN5-type HATs, AtGCN5 and ZmGCN5, have been well characterized and exhibit HAT activity in vitro [32,33]. In yeast, GCN5 protein is a component of several multisubunit protein complexes, such as ADA and SAGA [34]. In each complex, GCN5 coordinates with other common subunits such as the ADA2 and ADA3 proteins to stimulate transcriptional activation [35]. Similarly, AtGCN5 appears to interact with the Arabidopsis homologs of the yeast transcriptional adaptor proteins ADA2a and ADA2b [32,36]. Maize homologs of GCN5 (ZmGCN5) and ADA2 (ZmADA2) also interact with each other in vitro and in vivo [33,37]. [37]Notably, the ZmGCN5 protein level decreases in response to an elevated acetylation level caused by the treatment of a deacetylase inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA), whereas reduction in ZmGCN5 protein leads to less abundance of histone deacetylase protein [33]. These data suggest that transcription of histone-modifying genes is also dependent on histone acetylation and deacetylation.

Plant GCN5 homologs are involved in response to stresses and developmental changes. The Arabidopsis AtGCN5 and ADA2 proteins interact with transcription factor (e.g., C-repeat/DRE binding factor 1, CBF1) that is responsible for cold-induced gene expression. Mutations disrupting ADA2b and GCN5 induce various pleiotropic defects in Arabidopsis, including dwarfism, aberrant root development, short petals and stamens, and reduced expression of cold-regulated genes in cold acclimation [38]. The data suggest that histone acetylation plays an important role in plant gene expression in response to environmental changes. Interestingly, AtGCN5 not only acetylates cytoplasmic and nucleosomal histones, but also acetylates ADA2 proteins at a site unique to plant homologs but not present in fungal or animal homologs [36], suggesting a novel role of HATs in autoregulation of plant histone acetyltransferase complexes.

Recent studies have suggested a variety of roles for GCN5 during plant development [39,40]. Maize Opaque-2 (ZmO2), a bZip class transcription factor that promotes the expression of seed storage proteins and modulates transcriptional regulation through interaction with both ZmGCN5 and ZmADA2 [37]. Mutations in AtGCN5 affect spatial expression of transcription factor genes WUS and AG that are required for shoot and floral meristem integrity [41], resulting in the production of terminal flowers and the homeotic transformation of flower organs [39]. AtGCN5 has also been isolated in the suppressor screen for a topless-1 mutation (tpl-1) that transforms the shoot pole into a second root pole during embryogenesis [40]. Mutation of AtGCN5 in the tpl-1 background corrects the expression pattern of misregulated WUS, thereby restoring proper differentiation of the shoot pole [40]. However, it is not clear whether WUS is the direct or indirect target of AtGCN5. AtGCN5 might indirectly repress WUS transcription through activation of its repressor or directly recruit the repressor to its promoter region.

2.2. Histone deacetylases (HD, HDAs or HDACs)

The histone deacetylase, RPD3, was first identified as a positive and negative transcriptional regulator for a subset of yeast genes [42]. The link between histone deacetylation and transcriptional repression was not established until a mammalian RPD3 homolog HD1 was shown to exhibit histone deacetylase activity [43]. Since then, four types of histone deacetylases have been identified in various species including plants [14] (Table 2). Class I, II and III consist of enzymes homologous to yeast RPD3 (reduced potassium dependency protein 3), HDA1 (histone deacetylase 1 protein), and SIR2 (silent information regulator protein 2) proteins, respectively, which have been extensively studied in several model systems, including yeast, human and plant. The fourth class of HDACs, the HD2-like proteins, discovered in maize, appears to be a plant-specific histone deacetylase [44,45]. Studies in yeast have shown that different histone deacetylases are involved in distinct biological processes but may also have some overlapping functions [46-48].

2.3. RPD3-like HDACs

A plant RPD3 homologue was first identified in maize, which complements a yeast rpd3 null mutant [49]. Three maize RPD3-related histone deacetylases, ZmRpd3/101 (ZmHDA101, ZmRpd3I or ZmHD1BI), ZmRpd3/102 (ZmHDA102), and ZmRpd3/108 (ZmHD1BII or ZmHDA108), have similar transcription profiles in all organs and cellular components analyzed, although the relative amounts of transcripts differ, indicating a possible functional redundancy among gene family members [50]. The ZmRpd3 proteins interact with the maize retinoblastoma-related protein, ZmRBR1, a key regulator of the G1/S transition [51], and with the maize retinoblastoma-associated protein, ZmRbAp1, a histone-binding protein involved in nucleosome assembly [52], suggesting a role in cell cycle progression [50] (Fig. 1B). Like yeast RPD3 [53], ZmRpd3 proteins appear to specifically remove an acetyl group from histone H4 at lysine 5 and 12 [54], thus reversing the acetylation events promoted by type B HATs on the newly synthesized histones prior to their incorporation into chromatin [27].

Among 4 closely related members of RPD3-like histone deacetylase genes in Arabidopsis, AtHD1 and AtHDA6 are best characterized and exhibit divergent and overlapping functions. AtHD1 (AtHDA19 or AtRPD3A) is constitutively expressed [55,56]. Unlike ZmRpd3/108 that is localized in both nucleus and cytoplasm [50], AtHD1 is predominantly accumulated in the nucleus presumably in the euchromatic regions and excluded from the nucleolus [57]. Down-regulation of AtHD1 results in accumulation of hyperacetylated histone H3 and H4 [58-60], whereas overexpression of AtHD1 reduces the amount of tetra-acetylated histone H3 [56], implying that AtHD1 possesses histone deacetylase activity. Indeed, AtHD1 exhibits a moderate amount of histone deacetylase activity in vitro [57].

A fusion protein of AtHD1 with a DNA-binding domain represses transcription of a reporter gene [55], providing evidence for the role of histone deacetylases in transcriptional repression in plants. Down-regulation of AtHD1 by antisense inhibition or T-DNA insertion in Arabidopsis induces various developmental defects, including early senescence, serrated leaves, aerial rosettes, defects in floral organ identity and late flowering [55,58,60]. AtHD1 may also coordinate with TPL (topless) to allow proper root and shoot differentiation during embryogenesis [40]. In rice, overexpression of rice HD1 homolog OsHDAC1-3 in transgenic rice leads to increased growth rate and altered architecture [61]. Transcriptome analysis shows that over 7% of the genes involved in cellular biogenesis, protein synthesis, ionic homeostasis, protein transport and plant hormonal regulation, are up- or down-regulated in a T-DNA insertion line of AtHD1 (athd1-1) in Arabidopsis [60], suggesting a general role of HDA19 in gene expression and development.

AtHDA6 (AtRPD3B) encodes another RPD3-like histone deacetylase homologous to AtHD1 [55,62]. AtHDA6 is expressed in various tissues, including leaf, flower, siliques and young seedlings, at a lower level than AtHD1 (Plant ChromDB, http://www.chromdb.org). AtHDA6 mutants are identified in two independent screens for the chromatin factors that affect transgene expression [62,63]. The expression of auxin-responsive transgenes but not endogenous auxin-response genes is elevated in AtHDA6 mutants [62]. In another AtHDA6 mutant allele, rts1 (RNA-mediated transcriptional silencing), a silenced transgene is derepressed, resulting in a partial loss of methylation in the promoter region [63]. In contrast to AtHD1 mutants, AtHDA6 mutants do not show obvious abnormal phenotypes.

In Arabidopsis interspecific hybrids and allotetraploids, AtHDA6 is predominately localized in the nucleoli and is required for inactivation of NORs (nucleolus organization region) inherited from one parent [64,65]. AtHDA6 is also detected in other nuclear foci, supporting the roles of AtHDA6 in silencing transgenes and transposable elements [62,63,66,67]. AtHDA6 is a broad-specificity HDAC that is capable of removing acetyl groups from multiple lysine residues of multiple histones, including lysine 14 of histone H3 and lysine 5 and 12 of histone H4 [65]. Although the overall levels of histone H4 acetylation are only slightly affected in the AtHDA6 mutant (sil) [64], hyperacetylation appears to be restricted to the NOR regions that contain rDNA repeats [64,65]. The data suggest that unlike AtHD1, AtHDA6 is mainly responsible for repression of repetitive transgenic and endogenous genes as well as maintenance of NORs.

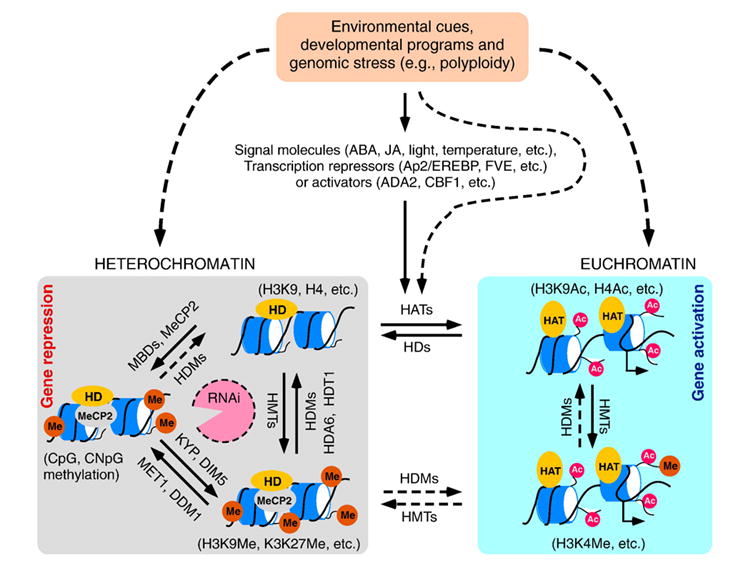

Arabidopsis AtHD1 and AtHDA6 are also involved in response to pathogens and environmental stresses. AtHD1 transcripts have been shown to be up-regulated by wounding, pathogen infection, and the plant hormones JA and ethylene that accumulate in response to pathogen infections [56]. The corepressor multiprotein complex containing AtHD1 could be recruited to stress-responsive genes to mediate transcriptional repression under stress conditions, suggesting a role for histone deacetylase in biotic and abiotic stress signal transduction pathways [55,61,68,69]. AtHD1 and AtHDA6 expression is induced by ethylene and JA [56]. ABA and JA antagonistically regulate the expression of salt stress-inducible genes. ABA represses, whereas JA activates stress responsive genes [70] and defense related genes [71]. It is unclear why AtHD1 and AtHD6 are both elevated by these phytohormones that have an opposing effect on expression of stress-related genes. Some effects may be indirect. For example, increased expression of AtHD1 in response to photohormones may affect expression of a repressor or activator that changes the expression of downstream genes in stress pathways. AtHD1 is part of a corepressor complex that is thought to mediate gene expression in response to various stress conditions [68,69]. The data suggest that different HDAC family members may play different roles in gene expression for stress-related pathways (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Model of how changes in environmental cues, developmental programs, and genome composition (e.g., polyploidy) induce molecular cascades that can lead to alteration of chromatin structure via histone modifications (acetylation in red circle and methylation in orange circles) and DNA methylation. Locus-specific changes in histone acetylation are mediated by the interactions between signal molecules and transcriptional activators or repressors and HATs or HDs, respectively. The relationships among histone modifications and DNA methylation are interactive and circular. The histone acetylation status works in combination with histone methylation and DNA methylation to maintain a relatively stable structure of chromatin-mediated gene repression. RNA interference (in red open circle) by short interfering RNAs, (siRNAs) may establish and reinforce heterochromatin formation via DNA methylation and histone methylation [142]. As a result, changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation or histone methylation facilitate proper expression of target genes in response to light, temperatures, abiotic and biotic stresses, and polyploidy. There is also evidence for physiologically or stress-induced changes in DNA recombination and gene expression (dashed lines) [154,155], which may suggest epigenetic inheritance of induced memory. Dashed arrows indicate that the connections may be established with additional experimental data. ABA: abscisic acid; JA: jasmonic acid; HAT: histone acetyltransferase; HD (HDA, HDT): histone deacetylase; HDM: histone demethylase; HMT: histone methyltransferase; KYP: KRYPTONITE, a histone methyltransferase; DIM5: a SET domain protein for histone methyltransferase; MET1: DNA methyltransferase 1; DDM1: a SWI2/SNF2 chromatin protein affecting DNA methylation; MBD: methyl-binding domain; and MeCP: methyl CpG binding protein.

Other members of RPD3-related HDACs are not well understood. Arabidopsis AtHDA18 has been demonstrated to participate in cellular patterning of the root epidermis [72]. The expression of a patterning gene WER was decreased in hda18 mutant, leading to hair cell development at non-hair positions in the root.

Little is known about HDA1-like histone deacetylases in plants. ZmHDA1 is the only plant HDA1-type HDAC that has been characterized to date [73]. The 84-kDa protein is enzymatically inactive and is subsequently processed to an active 48 kDa HDAC by proteolytic removal of the C-terminal part [73]. Consistent with the enzymatic activity, only the 48-kDa protein can efficiently repress transcription of a reporter gene, whereas the full-length protein exhibits very little repression.

2.4. HD2-like HDACs

HD2s consist of a group of plant-specific histone deacetylases that do not share sequence similarities with other known HDAC proteins [28]. Some members of HD2 histone deacetylases are localized in nucleoli, and others play a role in ovule and seed development. The specific and unique roles of HD2 histone deacetylases in plants have to be further elucidated and established.

The HD2 protein was first purified from maize; the active form is a phosphoprotein [45,52]. Four HD2 homologs have been identified in Arabidopsis [55,74,75]. AtHD2A, AtHD2B and AtHD2C mediate repression of a reporter gene through interactions with transcription factors [75]. These three AtHD2s are highly expressed in ovules, embryos, shoot apical meristems, and primary leaves, and during somatic embryogenesis, whereas AtHD2D is expressed in stems, flowers, and young siliques, suggesting that AtHD2D may have diverged its functions [76]. Both down-regulation and overexpression of AtHD2A induce abortive seeds [74,76]. Moreover, some genes involved in seed development and maturation were repressed in the transgenic plants overexpressing AtHD2A. ScHD2a, an ortholog of AtHD2A in Solanum chacoense (a wild species related to potato), is strongly induced in ovules after fertilization [77]. Collectively, the data suggest a role of AtHD2 in gene expression during seed development.

HD2 proteins may function in the same biological process as RPD3-related HDACs [78,79]. Nucleolar localization of maize HD2 suggests a possible role of ZmHD2 in the expression of ribosomal RNAs [45]. AtHD2A (HDT1) is also localized in the nucleolus and is required for H3 lysine 9 deacetylation and subsequent H3 lysine 9 methylation in the NORs, suggesting that AtHD2A works with AtHDA6 in silencing rRNA genes subjected to nucleolar dominance (silencing of rRNA genes originating from one progenitor in an interspecific hybrid or allopolyploid) [65].

AtHD2C mediates abscisic acid (ABA) responses in Arabi-dopsis [78]. AtHD2C expression is moderately repressed by ABA. Transgenic plants overexpressing AtHD2C show tolerance to salt and drought, which is contrary to a simple prediction of reduced tolerance in these plants. The data suggest an indirect effect of AtHD2C on stress-induced gene expression. Notably, HD2 is not related to RPD3-like proteins [45], but it shares some sequence similarities with nuclear FK506-binding protein (FKBP) family members that interact with RPD3-like HDACs in yeast and mammals [80,81]. A FKBP, a member of the peptidyl prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) family, is a histone chaperone that is required for rDNA silencing [82]. HD2 may modulate gene expression in a complex containing an RPD3-like HDACs, such as AtHDA6 and AtHD1, although it is yet to be determined whether any HD2 members interact with RPD3-like proteins.

2.5. SIR2-like HDACs

SIR2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase that is associated with longevity in yeast [83,84]. A mammalian SIR2 homolog, SIRT1, appears to control the cellular response to stress by regulating the FOXO family of Forkhead transcription factors, leading to an increase in organismal longevity [85]. Another human SIR2 homolog, hSIRT3, gains deacetylase activity through proteolytic cleavage [86], as observed in maize ZmHDA1[73], suggesting that proteolysis might represent a mechanism for the function of some histone deacetylases. Two SIR2 homologs are identified in Arabidopsis [28], and their functions are yet to be determined.

3. Roles of histone acetylation and deacetylation in cell cycle progression

Newly replicated chromatin contains acetylated histones [87], which are immediately deacetylated after being incorporated into chromatin [88] (Fig. 1B). The phenomenon is very conserved among a variety of organisms, including animals and plants. Deposition-related acetylation occurs in newly synthesized histones during S-phase at lysines 5 and 12 of H4 [89-91], lysine 16 in the dicot field bean [90], and lysine 8 in barley [91]. Both lysines 5 and 12 of histone H4 are specific acetylation substrates of the type B histone acetyltransferase HAT1p in yeast [24] and its homologue HAT-B in maize [25,54]. Histone acetyltransferase activity of HAT-B coincides with DNA replication in maize meristematic cells, further suggesting the involvement of H4K5 and H4K12 in histone deposition and chromatin assembly during S phase [54]. In maize, both HAT-B and RPD3-like histone deacetylases (ZmRpd3) interact with the maize retinoblastoma-associated protein, ZmRbAp1 [54]. ZmRpd3 protein also interacts with the maize retinoblastoma-related protein, ZmRBR1, a key regulator of the G1/S transition [51].

Studies using antibodies against specific histone isoforms have revealed cell cycle-dependent modulation of histone acetylation at specific chromatin domains (nucleolus organizers, euchromatin and heterochromatin) during interphase in mammals [92,93] and plants [90,91,94]. H4K5 and H4K12 are highly acetylated in NORs from prophase to anaphase followed by simultaneous deacetylation during telophase and interphase; pair-wise acetylation of H4K8 and H4K16 is associated with the distal regions (gene-rich regions) on the chromosomes; high levels of H4K5, H4K8 and H4K12 acetylation in the centromeric region remain in the interphase but disappear throughout mitosis [90,95].

The temporal and spatial histone acetylation patterns share common features as well as display some differences [94]. Euchromatic regions are associated with acetylated histones, which are abundant during early and mid-S phase and decreased from late S through M to G1 [12,90,91,94]. Histones are heavily acetylated at heterochromatic domains during late S and G2 stages and quickly deacetylated before mitosis. The temporal histone acetylation patterns of the chromosome coincide with the replication timing of different chromosomal domains, as heterochromatin is found to replicate latest in S phase. In contrast, histone acetylation in the earliest replicated NORs is most intense during mitosis, decreases in G1 toward a minimum in S, and increases again in late S. However, different histone lysine residues are subjected to cell cycle-dependent modulation. As in mammals, deposition-related acetylation of H4K5 and H4K12 in field bean and barley displays similar acetylation dynamics. H4K8 in barley [91] and H4K16 in field bean [90] may also be subjected to deposition-related acetylation. Treatment with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) induces acetylation of H4K5, K12 and K16 (but not K8) and alters heterochromatin structure in field bean [96]. Only H4K16 in Arabidopsis displays cell cycle-dependent modulation, whereas H4K5, K12 and K8 remain constantly acetylated through G1, S, late S/early G2 and G2 stages [94]. In contrast to the lack of cell cycle-dependent changes of histone H3 acetylation in field bean and barley [90,91], Arabidopsis histone H3K18 (but not H3K9) displays similar changes in acetylation as H4K16 does [94].

Chromosomes are subjected to a high level of condensation during transition from interphase to mitosis, which ensures accurate transmission of genetic information during cell division. Reversible acetylation and deacetylation of nucleosome core histones contribute substantially to modulation of chromatin conformation and compaction [97-99] (Fig. 1B). H3K9 and H4K5 acetylation levels are reduced in mammalian mitotic cells during mitosis [100]. However, it is unclear whether histone deacetylation is essential for progression through mitosis in mammalian cells. Although TSA treatment of human fibroblast cells results in hyperacetylated chromatin [100,101], this treatment did not have a significant effect on chromosome condensation or progress through mitosis [100]. In contrast, a recent study suggests that hyperacetylated chromatin impairs chromosome condensation, which further interferes with sister chromatid separation and regular mitotic progression [101]. Similarly, a study in tobacco protoplasts found that acetylation of H4 and H3K9/14 was dramatically reduced during mitosis in a phasespecific manner [102]. TSA treatments lead to dramatic increase in histone H3 and H4 acetylation and caused mitotic arrest in protoplast cells. TSA also inhibits mitosis in pea [103]. In barley, histone H4 acetylation levels are not always reduced during mitosis, but instead are dependent on a combination of the specific lysine residue, developmental stage, and chromosomal region [91,95]. Thus in both plants and animals, mitosis is associated with changes in acetylation status of histones that is correlated with dynamic changes in chromosome structure and function.

4. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in response to environmental cues

Plants are sessile organisms that cannot choose their living environments; therefore, it is essential for them to develop rapid responses to changes in environmental conditions for their adaptation and survival. The precise control of chromatin modification may play a central role in regulating gene expression in response to environmental cues because the switch between permissive and repressive chromatin allows alteration of gene expression in response to environmental changes. A number of studies have shown that plants are capable of adapting their growth and development to environment changes such as light, temperature, biotic and abiotic stresses through modulation of histone acetylation (Fig. 2).

Light signals are amongst the most important environmental factors regulating plant growth and development throughout the entire life cycle [104,105]. Plants can sense and measure the intensity, direction, duration and wavelength of light and effectively adapt to growth conditions. It was first demonstrated in tobacco green shoots that transcriptional activation of light-induced pea plastocyanin gene (PetE) is associated with hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 [106,107], suggesting a role for histone acetylation in a regulatory switch that integrates light signals into control of gene transcription. Mutation of an Arabidopsis TAFII250-type histone acetyltransferase, HAF2, results in reduced expression of the light-inducible genes, RBCS-1A and CAB2, correlated with the reduction of histone H3 or H4 acetylation in the light responsive promoter regions [108]. A mammalian homolog of Damaged DNA-binding protein 1 (DDB1) interacts with GCN5-type histone acetyltransferase [109].

Interestingly, a recent study on the expression of a maize C4-specific gene encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (C4-PEPC) regulated by both light and nitrogen availability has indicated that illumination is sufficient and necessary to induce hyperacetylation of histone H4 at the C4-PEPC promoter regardless of the nitrogen depletion and therefore independent of the transcriptional state of C4-PEPC[110]. Thus, illumination can alter acetylation status of a promoter in the absence of a change in transcription, implying that the acetylation change is a direct result of illumination rather than an indirect effect on transcription.

The requirement of low temperature prior to flowering (vernalization) helps plants to avoid flowering in cold weather and reproduce successfully after the winter. FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), a MADS-box floral repressor, is a key regulator in the vernalization pathway [111,112]. Prolonged exposure to cold temperature induces changes in histone modifications and reduction of FLCexpression and hence promotes early flowering [113-116]. The VERNALIZATION INSENSITIVE 3 (VIN3) gene, which encodes a PHD finger protein, is induced in response to prolonged cold exposure [117]. Its activity is necessary for histone deacetylation of the FLC gene and is essential for the initial establishment of FLC silencing. It is probable that histone deacetylation may lead to histone H3K9 and H3K27 dimethylation (H3K9me2 and H3K27me2) by VRN2, a process that is required for the heterochromatin formation at the FLC locus and thus responsible for the maintenance of FLC repression [118,119]. FVE, a gene involved in autonomous pathway of flowering time, encodes a homolog of retinoblastoma-associated protein [120]. FVE has dual roles in regulating FLC and cold-responses [121].

A recent study has further demonstrated that the repression of FLC by vernalization is proportionally correlated with the reduced level of histone acetylation at the FLC locus [122]. With increasing periods of cold treatment, the quantitative decrease in FLC expression appears to be conversely correlated with a quantitative increase in expression of VIN3 [117]. Therefore, the time-dependent repression of FLC by vernalization is determined by the extent of the initial repression induced by cold exposure. Epigenetic silencing of FLC requires A.thaliana LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN 1 (LHP1). LHP1 is enriched at FLC chromatin after exposure to cold, and LHP1 activity is needed to maintain the increased levels of H3K9me2 at FLC chromatin that are characteristic of the vernalized state [123,124].

Plants inevitably encounter temperature fluctuations during their life cycles in natural conditions, and many plants have evolved freezing tolerance in response to low and non-freezing temperatures, which is known as cold acclimation [125]. The C-repeat binding factor (CBF) is a transcriptional co-activator involved in the cold response pathway [126]. Interaction between the GCN5-type histone acetyltransferase complex and the CBF1 protein stimulates the transcription of many cold-regulated (COR) genes [32,36,38].

Both cold acclimation and vernalization help plants adapt to low temperatures during growth and development. In contrast to the long period of cold exposure during vernalization, cold acclimation can also be achieved in a much shorter time [113]. Therefore plants are capable of measuring the length of cold exposure via a rapid and short-term response to freezing or a long-term response to the cold winter. This sensing system may be perceived through differential histone modifications, and reversible histone acetylation and deacetylation may be responsible for rapidly switching “on” or “off” cold-regulated gene expression in response to the environmental changes (Fig. 2). Over time, stable histone methylation may be established following initial histone deacetylation, leading to the stable repression of specific genes after being subjected to long-term changes such as vernalization. Cold accumulation and flowering may be related via histone acetylation.

Plants also respond to abiotic and biotic stresses via plant hormones such as ethylene, ABA, and jasmonic acid (JA) [127,128]. Several histone deacetylases or protein factors that interact with HDs have been identified as factors that contribute to plant responses to various stresses, suggesting a role of histone acetylation and deacetylation in integrating ABA, ethylene and JA signals to modulate the expression of stress responsive genes [56,78,129]. The Arabidopsis RPD3-type HDAC, HDA6 (CIP3), interacts with COI1, an F-box protein, which is required for JA-mediated plant defense responses [129].

Although it is not yet determined whether AtHD1 physically interacts with COI1, overexpression of AtHD1 induces the expression of ethylene- and JA-regulated PATHOGENESIS-RELATED (PR) genes and leads to an increased resistance to plant pathogens [56]. AtHD1 expression is induced by wounding, pathogens, JA, and ethylene. In contrast, the expression of AtHD2C is repressed by ABA [78]. The data suggest that HDACs of different families might play different roles in plant response to stresses. In yeast and mammalian systems, histone deacetylases mediate transcriptional repression in a multiprotein complex containing SIN3, SAP18, SAP30 and RbAp46 [130-132]. In plants, ethylene responsive element binding factors (ERFs) recruit a histone deacetylase complex containing AtHD1 and plant homologs of AP2/EREBP, SAP18 and SIN3 to the promoter regions of stress responsive genes, thereby mediating specific responses to ABA-related stresses, such as drought and high salt [68,69]. Differential acetylation is also associated with salt stress in alfalfa [133].

5. Interactive roles of histone acetylation, histone methylation, and DNA methylation in response to genomic stress

Global analysis of histone acetylation and methylation patterns in the yeast genome suggests that histone acetylation occurs predominantly at the beginning of genes, whereas methylation can occur throughout the regions of actively transcribed genes [134]. The data suggest sequential modifications between histone acetylation and methylation. Among histone acetylation modifications, one group of lysine acetylation is located adjacent to the transcriptional start site and does not appear to correlate with transcription, whereas the other group of modifications occurs in gradients through the coding regions of genes in a pattern associated with transcription [135]. These results are consistent with notion that multiple modifications share the same role.

A general model is that reversible reactions of histone acetylation and deacetylation are responsible for perceiving environmental and developmental signals and may lead to stable modifications involving histone and DNA methylation (Fig. 2). These environmental signals are exerted by interacting with transcription activators (e.g., ADA2 and CBF1) [32,36,38,126], repressors (e.g., FVE and AP2/EREBP) [68,69,120], and/or molecules involved in signal transduction (e.g., ABA, JA, and light) [56,78,110,129]. These molecules recruit histone deacetylases (e.g., RPD3, AtHD1) to the promoters of the environmental or developmental responsive genes, which in turn remodels the chromatin and activates or represses transcription.

Mechanistically, histone acetylation works with other modifications including histone methylation and DNA methylation to modulate transcriptional regulation. Biochemical studies in mammalian cells indicate that histone deacetylases exist within a complex containing methylcytosine-binding proteins (MeCP2) [136,137], and that HD is recruited by MeCP2 to repress gene activity. Knockdown of Arabidopsis AtHDA6 and AtHDT1 induces histone methylation in allopolyploids [65,79], suggesting a relationship between histone acetylation and methylation. Moreover, blocking histone deacetylases using the inhibitor TSA induces locus-specific DNA methylation loss in Neurospora, linking histone acetylation to DNA hypomethylation [138].

Histone acetylation, DNA methylation, and RNA interference are interdependent mechanisms for gene silencing [4,139,140]. In Arabidopsis, HDA6 enhances DNA methylation induced by RNA-directed transcriptional silencing [63]. Arabidopsis AGO4, together with siRNAs, affects histone methylation, non-CpG DNA methylation and heterochromatin silencing [141,142]. Histone methylation usually affects DNA methylation. In the fungus Neurospora crassa, DIM-5 is a homolog to SET [Su(var)3–9, Enhancer-of-zeste, Trithorax] domain proteins that form a family that can alter gene expression through histone methylation [143]. DIM-5 has histone methyltransferase (HMT) activity and catalyzes H3K9me2; dim-5 mutation causes genome-wide loss of histone H3 dimethylation [144], suggesting that H3K9 methylation serves as a histone marker for DNA methylation. In Arabidopsis, KRYPTONITE, a methyltransferase specific to H3K9, affects cytosine methylation at CpNpG sites and contributes to silencing of endogenous retrotransposons [145]. Decrease in DNA methylation gene (DDM1) encodes a protein related to SWI2/SNF2 chromatin remodeling factors, and ddm1 mutation affects both CG and CNG DNA methylation, preferentially in repetitive DNA sequences and heterochromatic regions [146].

Chromatin modifications and RNAi pathways provide general mechanisms for gene expression variation in response to environmental and developmental changes as well as to the interspecific hybridization or genomic stress predicted by Barbara McClintock [147] (Fig. 2). Over time, different species may evolve to possess chromatin- and RNA-mediated pathways in response to environmental and developmental changes [148,149]. The combination of distinct genomes in allopolyploids may generate genomic stress and thus induce chromatin remodeling and RNA-mediated pathways. The rRNA genes subjected to nucleolar dominance suggest that DNA methylation and histone acetylation and methylation are interrelated [79]. Arabidopsis HDT1 is localized in nucleoli and involved in rRNA gene silencing [65]. Disruption of HDA6 reduces levels of promoter cytosine methylation and causes replacement of histone H3K9me2 with H3K4me3, H3K9 acetylation, H3K14 acetylation, and histone H4 tetra-acetylation, suggesting a role of concerted histone acetylation and methylation in silencing endogenous repetitive genes. In Arabidopsis synthetic allotetraploids that are formed by interspecific hybridization between A. thaliana and A. arenosa, A. thaliana FLC is trans-activated by A. arenosa FRI via histone H3K9 acetylation and H3K4 methylation, leading to late flowering in the allotetraploids [150]. Knockdown of the genes encoding DNA methyltransferases, histone deacetylases, and RNA interference pathway proteins are available in Arabidopsis allotetraploids [151,152]. Preliminary data indicate that DNA methylation affects a subset of heterochromatic genes that are subjected to silencing during interspecific hybridization [152,153], which is different from those affected by histone deacetylation or RNAi (M. Chen, L. Tian, and Z. J. Chen, unpublished). It is conceivable that chromatin of homologous loci may be remodeled by histone acetylation during early stages of polyploid formation, some of which are reinforced by stable modifications such as histone and DNA methylation. As predicted [148], histone and other chromatin modifications may also affect transcription of miRNA precursors and small RNAs that in turn alter the expression of the target genes in interspecific hybrids or allopolyploids.

Acknowledgments

We thank Enamul Huq, Andrew Woodward, and Keqiang Wu for critical suggestions to improve the manuscript, and the National Institutes of Health (GM067015) and the National Science Foundation Plant Genome Program (DBI0501712) for support of research in the Chen laboratory. We apologize for not citing additional relevant references owing to space limitations.

References

- 1.Horn PJ, Peterson CL. Heterochromatin assembly: a new twist on an old model. Chromosome Res. 2006;14:83–94. doi: 10.1007/s10577-005-1018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornberg RD. Structure of chromatin. Ann Rev Biochem. 1977;46:931–954. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.46.070177.004435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner BM. Cellular memory and the histone code. Cell. 2002;111:285–291. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner BM. Histone acetylation and an epigenetic code. BioEssays. 2000;22:836–845. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200009)22:9<836::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allfrey VG, Faulkner R, Mirsky AE. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1964;51:786–794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luger K, Richmond TJ. The histone tails of the nucleosome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo MH, Allis CD. Roles of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases in gene regulation. BioEssays. 1998;20:615–626. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<615::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tse C, Sera T, Wolffe AP, Hansen JC. Disruption of higher-order folding by core histone acetylation dramatically enhances transcription of nucleosomal arrays by RNA polymerase III. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4629–4638. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuchs J, Demidov D, Houben A, Schubert I. Chromosomal histone modification patterns — from conservation to diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loidl P. A plant dialect of the histone language. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lusser A, Kolle D, Loidl P. Histone acetylation: lessons from the plant kingdom. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(00)01839-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waterborg JH. Dynamics of histone acetylation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:27602–27609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waterborg JH. Identification of five sites of acetylation in alfalfa histone H4. Biochemistry. 1992;31:6211–6219. doi: 10.1021/bi00142a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuks F, Burgers WA, Brehm A, Hughes-Davies L, Kouzarides T. DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 associates with histone deacetylase activity. Nat Genet. 2000;24:88–91. doi: 10.1038/71750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bestor TH. Gene silencing. Methylation meets acetylation. Nature. 1998;393:311–312. doi: 10.1038/30613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards EJ, Elgin SC. Epigenetic codes for heterochromatin formation and silencing: rounding up the usual suspects. Cell. 2002;108:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brownell JE, Allis CD. Special HATs for special occasions: linking histone acetylation to chromatin assembly and gene activation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cress WD, Seto E. Histone deacetylases, transcriptional control, and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2000;184:1–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200007)184:1<1::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth SY, Denu JM, Allis CD. Histone acetyltransferases. Ann Rev Biochem. 2001;70:81–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verreault A, Kaufman PD, Kobayashi R, Stillman B. Nucleosomal DNA regulates the core-histone-binding subunit of the human Hat1 acetyltransferase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:96–108. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parthun MR, Widom J, Gottschling DE. The major cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase in yeast: links to chromatin replication and histone metabolism. Cell. 1996;87:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eberharter A, Lechner T, Goralik-Schramel M, Loidl P. Purification and characterization of the cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferase B of maize embryos. FEBS Lett. 1996;386:75–81. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lusser A, Eberharter A, Loidl A, Goralik-Schramel M, Horngacher M, Haas H, Loidl P. Analysis of the histone acetyltransferase B complex of maize embryos. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4427–4435. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolle D, Sarg B, Lindner H, Loidl P. Substrate and sequential site specificity of cytoplasmic histone acetyltransferases of maize and rat liver. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pandey R, Muller A, Napoli CA, Selinger DA, Pikaard CS, Richards EJ, Bender J, Mount DW, Jorgensen RA. Analysis of histone acetyltransferase and histone deacetylase families of Arabidopsis thaliana suggests functional diversification of chromatin modification among multicellular eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5036–5055. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carrozza MJ, Utley RT, Workman JL, Cote J. The diverse functions of histone acetyltransferase complexes. Trends Genet. 2003;19:321–329. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00115-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sterner DE, Berger SL. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:435–459. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.435-459.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bordoli L, Netsch M, Luthi U, Lutz W, Eckner R. Plant orthologs of p300/CBP: conservation of a core domain in metazoan p300/CBP acetyltransferase-related proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:589–597. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stockinger EJ, Mao Y, Regier MK, Triezenberg SJ, Thomashow MF. Transcriptional adaptor and histone acetyltransferase proteins in Arabidopsis and their interactions with CBF1, a transcriptional activator involved in cold-regulated gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1524–1533. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhat RA, Riehl M, Santandrea G, Velasco R, Slocombe S, Donn G, Steinbiss HH, Thompson RD, Becker HA. Alteration of GCN5 levels in maize reveals dynamic responses to manipulating histone acetylation. Plant J. 2003;33:455–469. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant PA, Duggan L, Cote J, Roberts SM, Brownell JE, Candau R, Ohba R, Owen-Hughes T, Allis CD, Winston F, Berger SL, Workman JL. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balasubramanian R, Pray-Grant MG, Selleck W, Grant PA, Tan S. Role of the Ada2 and Ada3 transcriptional coactivators in histone acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7989–7995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao Y, Pavangadkar KA, Thomashow MF, Triezenberg SJ. Physical and functional interactions of Arabidopsis ADA2 transcriptional coactivator proteins with the acetyltransferase GCN5 and with the cold-induced transcription factor CBF1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1759:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhat RA, Borst JW, Riehl M, Thompson RD. Interaction of maize Opaque-2 and the transcriptional co-activators GCN5 and ADA2, in the modulation of transcriptional activity. Plant Mol Biol. 2004;55:239–252. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vlachonasios KE, Thomashow MF, Triezenberg SJ. Disruption mutations of ADA2b and GCN5 transcriptional adaptor genes dramatically affect Arabidopsis growth, development, and gene expression. Plant Cell. 2003;15:626–638. doi: 10.1105/tpc.007922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertrand C, Bergounioux C, Domenichini S, Delarue M, Zhou DX. Arabidopsis histone acetyltransferase AtGCN5 regulates the floral meristem activity through the WUSCHEL/AGAMOUS pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28246–28251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302787200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Long JA, Ohno C, Smith ZR, Meyerowitz EM. TOPLESS regulates apical embryonic fate in Arabidopsis. Science. 2006;312:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.1123841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laux T, Mayer KF, Berger J, Jurgens G. The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development. 1996;122:87–96. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vidal M, Gaber RF. RPD3 encodes a second factor required to achieve maximum positive and negative transcriptional states in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6317–6327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taunton J, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brosch G, Goralik-Schramel M, Loidl P. Purification of histone deacetylase HD1-A of germinating maize embryos. FEBS Lett. 1996;393:287–291. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00909-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lusser A, Brosch G, Loidl A, Haas H, Loidl P. Identification of maize histone deacetylase HD2 as an acidic nucleolar phosphoprotein. Science. 1997;277:88–91. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bernstein BE, Tong JK, Schreiber SL. Genome-wide studies of histone deacetylase function in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13708–13713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250477697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes TR, Marton MJ, Jones AR, Roberts CJ, Stoughton R, Armour CD, Bennett HA, Coffey E, Dai H, He YD, Kidd MJ, King AM, Meyer MR, Slade D, Lum PY, Stepaniants SB, Shoemaker DD, Gachotte D, Chakraburtty K, Simon J, Bard M, Friend SH. Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell. 2000;102:109–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robyr D, Suka Y, Xenarios I, Kurdistani SK, Wang A, Suka N, Grunstein M. Microarray deacetylation maps determine genome-wide functions for yeast histone deacetylases. Cell. 2002;109:437–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00746-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossi V, Hartings H, Motto M. Identification and characterisation of an RPD3 homologue from maize (Zea mays L.) that is able to complement an rpd3 null mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;258:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s004380050733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varotto S, Locatelli S, Canova S, Pipal A, Motto M, Rossi V. Expression profile and cellular localization of maize Rpd3-type histone deacetylases during plant development. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:606–617. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.025403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rossi V, Varotto S. Insights into the G1/S transition in plants. Planta. 2002;215:345–356. doi: 10.1007/s00425-002-0780-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kolle D, Brosch G, Lechner T, Pipal A, Helliger W, Taplick J, Loidl P. Different types of maize histone deacetylases are distinguished by a highly complex substrate and site specificity. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6769–6773. doi: 10.1021/bi982702v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rundlett SE, Carmen AA, Suka N, Turner BM, Grunstein M. Transcriptional repression by UME6 involves deacetylation of lysine 5 of histone H4 by RPD3. Nature. 1998;392:831–835. doi: 10.1038/33952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lechner T, Lusser A, Pipal A, Brosch G, Loidl A, Goralik-Schramel M, Sendra R, Wegener S, Walton JD, Loidl P. RPD3-type histone deacetylases in maize embryos. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1683–1692. doi: 10.1021/bi9918184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu K, Malik K, Tian L, Brown D, Miki B. Functional analysis of a RPD3 histone deacetylase homologue in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;44:167–176. doi: 10.1023/a:1006498413543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhou C, Zhang L, Duan J, Miki B, Wu K. Histone deacetylase19 is involved in jasmonic acid and ethylene signaling of pathogen response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1196–1204. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fong PM, Tian L, Chen ZJ. Arabidopsis thaliana histone deacetylase 1 (AtHD1) is localized in euchromatic regions and demonstrates histone deacetylase activity in vitro. Cell Res. 2006;16:479–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tian L, Chen ZJ. Blocking histone deacetylation in Arabidopsis induces pleiotropic effects on plant gene regulation and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:200–205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011347998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian L, Wang J, Fong MP, Chen M, Cao H, Gelvin SB, Chen ZJ. Genetic control of developmental changes induced by disruption of Arabidopsis histone deacetylase 1 (AtHD1) expression. Genetics. 2003;165:399–409. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.1.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tian L, Fong MP, Wang JJ, Wei NE, Jiang H, Doerge RW, Chen ZJ. Reversible histone acetylation and deacetylation mediate genomewide, promoter-dependent and locus-specific changes in gene expression during plant development. Genetics. 2005;169:337–345. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jang IC, Pahk YM, Song SI, Kwon HJ, Nahm BH, Kim JK. Structure and expression of the rice class-I type histone deacetylase genes OsHDAC1-3: OsHDAC1 overexpression in transgenic plants leads to increased growth rate and altered architecture. Plant J. 2003;33:531–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murfett J, Wang XJ, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Identification of Arabidopsis histone deacetylase hda6 mutants that affect transgene expression. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1047–1061. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aufsatz W, Mette MF, Van Der Winden J, Matzke M, Matzke AJ. HDA6, a putative histone deacetylase needed to enhance DNA methylation induced by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2002;2002:6832–6841. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Probst AV, Fagard M, Proux F, Mourrain P, Boutet S, Earley K, Lawrence RJ, Pikaard CS, Murfett J, Furner I, Vaucheret H, Scheid OM. Arabidopsis histone deacetylase HDA6 is required for maintenance of transcriptional gene silencing and determines nuclear organization of rDNA repeats. Plant Cell. 2004;16:1021–1034. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Earley K, Lawrence RJ, Pontes O, Reuther R, Enciso AJ, Silva M, Neves N, Gross M, Viegas W, Pikaard CS. Erasure of histone acetylation by Arabidopsis HDA6 mediates large-scale gene silencing in nucleolar dominance. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1283–1293. doi: 10.1101/gad.1417706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lippman Z, May B, Yordan C, Singer T, Martienssen R. Distinct mechanisms determine transposon inheritance and methylation via small interfering RNA and histone modification. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E67. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.May BP, Lippman ZB, Fang Y, Spector DL, Martienssen RA. Differential regulation of strand-specific transcripts from Arabidopsis centromeric satellite repeats. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song CP, Agarwal M, Ohta M, Guo Y, Halfter U, Wang P, Zhu JK. Role of an Arabidopsis AP2/EREBP-type transcriptional repressor in abscisic acid and drought stress responses. Plant Cell. 2005;17:2384–2396. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Song CP, Galbraith DW. AtSAP18, an orthologue of human SAP18, is involved in the regulation of salt stress and mediates transcriptional repression in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60:241–257. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-3880-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moons A, Gielen J, Vandekerckhove J, Van der Straeten D, Gheysen G, Van Montagu M. An abscisic-acid- and salt-stress-responsive rice cDNA from a novel plant gene family. Planta. 1997;202:443–454. doi: 10.1007/s004250050148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson JP, Badruzsaufari E, Schenk PM, Manners JM, Desmond OJ, Ehlert C, Maclean DJ, Ebert PR, Kazan K. Antagonistic interaction between abscisic acid and jasmonate-ethylene signaling pathways modulates defense gene expression and disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3460–3479. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu CR, Liu C, Wang YL, Li LC, Chen WQ, Xu ZH, Bai SN. Histone acetylation affects expression of cellular patterning genes in the Arabidopsis root epidermis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14469–14474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503143102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pipal A, Goralik-Schramel M, Lusser A, Lanzanova C, Sarg B, Loidl A, Lindner H, Rossi V, Loidl P. Regulation and processing of maize histone deacetylase Hda1 by limited proteolysis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1904–1917. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dangl M, Brosch G, Haas H, Loidl P, Lusser A. Comparative analysis of HD2 type histone deacetylases in higher plants. Planta. 2001;213:280–285. doi: 10.1007/s004250000506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu K, Tian L, Zhou C, Brown D, Miki B. Repression of gene expression by Arabidopsis HD2 histone deacetylases. Plant J. 2003;34:241–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou C, Labbe H, Sridha S, Wang L, Tian L, Latoszek-Green M, Yang Z, Brown D, Miki B, Wu K. Expression and function of HD2-type histone deacetylases in Arabidopsis development. Plant J. 2004;38:715–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lagace M, Chantha SC, Major G, Matton DP. Fertilization induces strong accumulation of a histone deacetylase (HD2) and of other chromatin-remodeling proteins in restricted areas of the ovules. Plant Mol Biol. 2003;53:759–769. doi: 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000023665.36676.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sridha S, Wu K. Identification of AtHD2C as a novel regulator of abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;46:124–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lawrence RJ, Earley K, Pontes O, Silva M, Chen ZJ, Neves N, Viegas W, Pikaard CS. A concerted DNA methylation/histone methylation switch regulates rRNA gene dosage control and nucleolar dominance. Mol Cell. 2004;13:599–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang WM, Yao YL, Seto E. The FK506-binding protein 25 functionally associates with histone deacetylases and with transcription factor YY1. EMBO J. 2001;20:4814–4825. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arevalo-Rodriguez M, Cardenas ME, Wu X, Hanes SD, Heitman J. Cyclophilin A and Ess1 interact with and regulate silencing by the Sin3–Rpd3 histone deacetylase. EMBO J. 2000;19:3739–3749. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuzuhara T, Horikoshi M. A nuclear FK506-binding protein is a histone chaperone regulating rDNA silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:275–283. doi: 10.1038/nsmb733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith JS, Brachmann CB, Celic I, Kenna MA, Muhammad S, Starai VJ, Avalos JL, Escalante-Semerena JC, Grubmeyer C, Wolberger C, Boeke JD. A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6658–6663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, Tran H, Ross SE, Mostoslavsky R, Cohen HY, Hu LS, Cheng HL, Jedrychowski MP, Gygi SP, Sinclair DA, Alt FW, Greenberg ME. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwer B, North BJ, Frye RA, Ott M, Verdin E. The human silent information regulator (Sir)2 homologue hSIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:647–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ruiz-Carrillo A, Wangh LJ, Allfrey VG. Processing of newly synthesized histone molecules. Science. 1975;190:117–128. doi: 10.1126/science.1166303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jackson V, Shires A, Tanphaichitr N, Chalkley R. Modifications to histones immediately after synthesis. J Mol Biol. 1976;104:471–483. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sobel RE, Cook RG, Perry CA, Annunziato AT, Allis CD. Conservation of deposition-related acetylation sites in newly synthesized histones H3 and H4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1237–1241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jasencakova Z, Meister A, Walter J, Turner BM, Schubert I. Histone H4 acetylation of euchromatin and heterochromatin is cell cycle dependent and correlated with replication rather than with transcription. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2087–2100. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jasencakova Z, Meister A, Schubert I. Chromatin organization and its relation to replication and histone acetylation during the cell cycle in barley. Chromosoma. 2001;110:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s004120100132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taddei A, Roche D, Sibarita JB, Turner BM, Almouzni G. Duplication and maintenance of heterochromatin domains. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1153–1166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sadoni N, Langer S, Fauth C, Bernardi G, Cremer T, Turner BM, Zink D. Nuclear organization of mammalian genomes. Polar chromosome territories build up functionally distinct higher order compartments. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:1211–1226. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.6.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jasencakova Z, Soppe WJ, Meister A, Gernand D, Turner BM, Schubert I. Histone modifications in Arabidopsis — high methylation of H3 lysine 9 is dispensable for constitutive heterochromatin. Plant J. 2003;33:471–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wako T, Fukuda M, Furushima-Shimogawara R, Belyaev ND, Fukui K. Cell cycle-dependent and lysine residue-specific dynamic changes of histone H4 acetylation in barley. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49:645–653. doi: 10.1023/a:1015554124675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Belyaev ND, Houben A, Baranczewski P, Schubert I. Histone H4 acetylation in plant heterochromatin is altered during the cell cycle. Chromosoma. 1997;106:193–197. doi: 10.1007/s004120050239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wade PA, Wolffe AP. Histone acetyltransferases in control. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R82–R84. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shogren-Knaak M, Ishii H, Sun JM, Pazin MJ, Davie JR, Peterson CL. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311:844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kruhlak MJ, Hendzel MJ, Fischle W, Bertos NR, Hameed S, Yang XJ, Verdin E, Bazett-Jones DP. Regulation of global acetylation in mitosis through loss of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases from chromatin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38307–38319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cimini D, Mattiuzzo M, Torosantucci L, Degrassi F. Histone hyperacetylation in mitosis prevents sister chromatid separation and produces chromosome segregation defects. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3821–3833. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li Y, Butenko Y, Grafi G. Histone deacetylation is required for progression through mitosis in tobacco cells. Plant J. 2005;41:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Murphy JP, McAleer JP, Uglialoro A, Papile J, Weniger J, Bethelmie F, Tramontano WA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and cell proliferation in pea root meristems. Phytochemistry. 2000;55:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Franklin KA, Whitelam GC. Light signals, phytochromes and crosstalk with other environmental cues. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:271–276. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Neff MM, Fankhauser C, Chory J. Light: an indicator of time and place. Genes Dev. 2000;14:257–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chua YL, Brown AP, Gray JC. Targeted histone acetylation and altered nuclease accessibility over short regions of the pea plastocyanin gene. Plant Cell. 2001;13:599–612. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chua YL, Watson LA, Gray JC. The transcriptional enhancer of the pea plastocyanin gene associates with the nuclear matrix and regulates gene expression through histone acetylation. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1468–1479. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bertrand C, Benhamed M, Li YF, Ayadi M, Lemonnier G, Renou JP, Delarue M, Zhou DX. Arabidopsis HAF2 gene encoding TATAbinding protein (TBP)-associated factor TAF1, is required to integrate light signals to regulate gene expression and growth. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1465–1473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brand M, Moggs JG, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Lejeune F, Dilworth FJ, Stevenin J, Almouzni G, Tora L. UV-damaged DNA-binding protein in the TFTC complex links DNA damage recognition to nucleosome acetylation. EMBO J. 2001;20:3187–3196. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Offermann S, Danker T, Dreymuller D, Kalamajka R, Topsch S, Weyand K, Peterhansel C. Illumination is necessary and sufficient to induce histone acetylation independent of transcriptional activity at the C4-specific phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase promoter in maize. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1078–1088. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.080457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sheldon CC, Rouse DT, Finnegan EJ, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. The molecular basis of vernalization: the central role of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3753–3758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060023597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Michaels SD, Amasino RM. Loss of FLOWERING LOCUS C activity eliminates the late-flowering phenotype of FRIGIDA and autonomous pathway mutations but not responsiveness to vernalization. Plant Cell. 2001;13:935–941. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sung S, Amasino RM. Vernalization and epigenetics: how plants remember winter. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2004;7:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.He Y, Amasino RM. Role of chromatin modification in flowering-time control. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sung S, Amasino RM. Remembering winter: toward a molecular understanding of vernalization. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2005;56:491–508. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Simpson GG, Dean C. Arabidopsis, the Rosetta stone of flowering time? Science. 2002;296:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5566.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sung S, Amasino RM. Vernalization in Arabidopsis thaliana is mediated by the PHD finger protein VIN3. Nature. 2004;427:159–164. doi: 10.1038/nature02195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gendall AR, Levy YY, Wilson A, Dean C. The VERNALIZATION 2 gene mediates the epigenetic regulation of vernalization in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2001;107:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00573-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bastow R, Mylne JS, Lister C, Lippman Z, Martienssen RA, Dean C. Vernalization requires epigenetic silencing of FLC by histone methylation. Nature. 2004;427:164–167. doi: 10.1038/nature02269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ausin I, Alonso-Blanco C, Jarillo JA, Ruiz-Garcia L, Martinez-Zapater JM. Regulation of flowering time by FVE, a retinoblastoma-associated protein. Nat Genet. 2004;36:162–166. doi: 10.1038/ng1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kim HJ, Hyun Y, Park JY, Park MJ, Park MK, Kim MD, Lee MH, Moon J, Lee I, Kim J. A genetic link between cold responses and flowering time through FVE in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Genet. 2004;36:167–171. doi: 10.1038/ng1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sheldon CC, Finnegan EJ, Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. Quantitative effects of vernalization on FLC and SOC1 expression. Plant J. 2006;45:871–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sung S, He Y, Eshoo TW, Tamada Y, Johnson L, Nakahigashi K, Goto K, Jacobsen SE, Amasino RM. Epigenetic maintenance of the vernalized state in Arabidopsis thaliana requires like heterochromatin protein 1. Nat Genet. 2006;38:706–710. doi: 10.1038/ng1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mylne JS, Barrett L, Tessadori F, Mesnage S, Johnson L, Bernatavichute YV, Jacobsen SE, Fransz P, Dean C. LHP1, the Arabidopsis homologue of HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN1, is required for epigenetic silencing of FLC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5012–5017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507427103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Thomashow MF. Plant cold acclimation: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:571–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thomashow MF. So what’s new in the field of plant cold acclimation? Lots! Plant Physiol. 2001;125:89–93. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Finkelstein RR, Gampala SS, Rock CD. Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell. 2002;(14 Suppl):S15–S45. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wang KL, Li H, Ecker JR. Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. Plant Cell. 2002;(14 Suppl):S131–S151. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Devoto A, Nieto-Rostro M, Xie D, Ellis C, Harmston R, Patrick E, Davis J, Sherratt L, Coleman M, Turner JG. COI1 links jasmonate signalling and fertility to the SCF ubiquitin–ligase complex in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002;32:457–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]