Abstract

Cataracts are a clinically diverse and genetically heterogeneous disorder of the crystalline lens and a leading cause of visual impairment. Here we report linkage of autosomal dominant “progressive childhood posterior subcapsular” cataracts segregating in a white family to short tandem repeat (STR) markers D20S847 (LOD score [Z] 5.50 at recombination fraction [θ] 0.0) and D20S195 (Z=3.65 at θ=0.0) on 20q, and identify a refined disease interval (rs2057262–(3.8 Mb)–rs1291139) by use of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers. Mutation profiling of positional-candidate genes detected a heterozygous transversion (c.386A→T) in exon 3 of the gene for chromatin modifying protein-4B (CHMP4B) that was predicted to result in the nonconservative substitution of a valine residue for a phylogenetically conserved aspartic acid residue at codon 129 (p.D129V). In addition, we have detected a heterozygous transition (c.481G→A) in exon 3 of CHMP4B cosegregating with autosomal dominant posterior polar cataracts in a Japanese family that was predicted to result in the missense substitution of lysine for a conserved glutamic acid residue at codon 161 (p.E161K). Transfection studies of cultured cells revealed that a truncated form of recombinant D129V-CHMP4B had a different subcellular distribution than wild type and an increased capacity to inhibit release of virus-like particles from the cell surface, consistent with deleterious gain-of-function effects. These data provide the first evidence that CHMP4B, which encodes a key component of the endosome sorting complex required for the transport-III (ESCRT-III) system of mammalian cells, plays a vital role in the maintenance of lens transparency.

Hereditary forms of cataracts are usually diagnosed at birth (congenital), during infancy, or during childhood and are clinically important as a cause of impaired form vision development.1 In addition to being found in >50 genetic syndromes involving other ocular defects (e.g., microphthalmia [MIM 212550]) and systemic abnormalities (e.g., galactokinase deficiency [MIM 230200]), cataracts may be inherited as an isolated lens phenotype, most frequently by autosomal dominant transmission.2 So far, genetic linkage studies of >60 families worldwide have mapped at least 25 independent loci for clinically diverse forms of nonsyndromic cataracts on 15 human chromosomes, involving some 17 lens-abundant genes.2 The majority of associated mutations have been identified in 10 crystallin genes (CRYAA [MIM 123580], CRYAB [MIM 123590], CRYBB1 [MIM 600929], CRYBB2 [MIM 123620], CRYBB3 [MIM 123630], CRYBA1 [MIM 123610], CRYBA4 [MIM 123631], CRYGC [MIM 123680], CRYGD [MIM 123690], and CRYGS [MIM 123730]),3–11 which encode the major “refractive” proteins of the lens. The remaining mutations have been identified in seven functionally diverse genes, including those coding for gap-junction connexin proteins (GJA3 [MIM 121015], GJA8 [MIM 600897]),12,13 a heat-shock transcription factor (HSF4 [MIM 602438]),14 an aquaporin water channel (MIP [MIM 154050])15 a claudin-like cell-junction protein (LIM2 [MIM 154045]),16 and intermediate-filament-like cytoskeletal proteins (BFSP1 [MIM 603307], BFSP2 [MIM 603212]).17,18 In addition to the known genes, at least 10 novel genes for autosomal dominant or recessive forms of nonsyndromic cataracts remain to be identified at loci on chromosomes 1 (CCV [MIM 115665], CTPP1 [MIM 116600]), 2 (PCC [MIM 601286], CCNP [MIM 607304, MIM 115800]), 3 (CATC2 [MIM 610019]), 9 (CAAR [MIM 605749]), 15 (CCSSO [MIM 605728]), 17 (CTAA2 [MIM 601202], CCA1 [MIM 115660]), 19 (CATCN1 [MIM 609376]), and 20 (CPP3 [MIM 605387]).19–32 Here we have fine-mapped a locus for autosomal dominant cataracts on chromosome 20q and, subsequently, have identified underlying missense mutations in the gene for chromatin modifying protein-4B (CHMP4B [MIM 610897]), also known as charged multi-vesicular body protein-4B, which has not previously been associated with human disease.

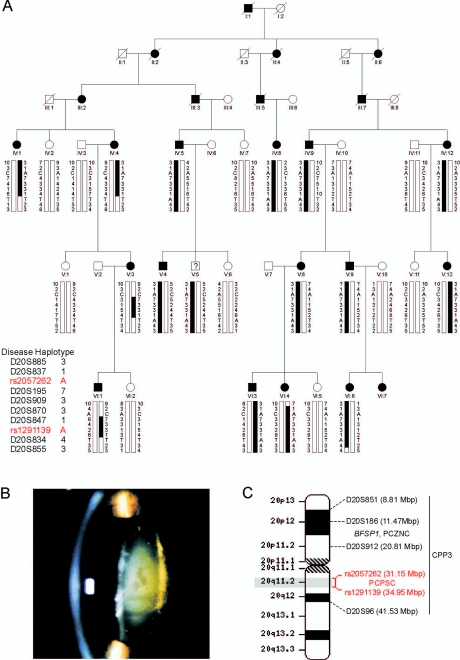

Linkage studies.—We investigated a six-generation white family from the United States (family Sk) segregating autosomal dominant progressive childhood posterior subcapsular cataracts (PCPSC) in the absence of other ocular or systemic abnormalities (fig. 1A). Ophthalmic records indicated that the cataracts presented in both eyes as disc-shaped posterior subcapsular opacities, progressing with age to affect the nucleus and anterior subcapsular regions of the lens (fig. 1B). The age at diagnosis varied from 4 to 20 years, and the age at surgery ranged from 4 to 40 years. Postsurgical corrected visual acuity varied from 20/20 to 20/200 in the better eye. Blood samples were obtained from 27 family members, and leukocyte genomic DNA was purified and quantified using standard techniques (Qiagen). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Washington University Human Research Protection Office, and written informed consent was provided by all participants prior to enrollment, in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Figure 1. .

Autosomal dominant PCPSC in a six-generation family (Sk). A, Pedigree and haplotype analysis showing segregation of eight STR markers and two SNP markers on 20q, listed in descending order from the centromere. Squares and circles denote males and females, respectively. Filled symbols and bars denote affected status and haplotypes, respectively. Individual V:5 is marked with a question mark (?) to denote unknown status. Pedigree and haplotype data were managed using Cyrillic 2.1 software (FamilyGenetix). B, Slit-lamp image of lens from affected female V:12 (age 40 years) showing posterior subcapsular, nuclear, and anterior subcapsular opacities. C, Ideogram of chromosome 20, comparing the cytogenetic location of SNP markers defining the PCPSC locus in this study (red) with those of STR markers defining loci for CPP3 and PCZNC.31,32

For linkage analysis, 15 affected individuals, 8 unaffected individuals, and 4 spouses from family Sk were genotyped using STR markers from the combined Généthon, Marshfield, and deCODE genetic linkage maps (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI]), as described elsewhere.33 Following exclusion of linkage to known loci for autosomal dominant cataracts on chromosomes 1–3, 10–13, 15–17, 19, 21, and 22 (table 1), we obtained significant evidence of linkage (table 2) for markers D20S847 (Z=5.50 and θ=0), D20S195 (Z=3.65 and θ=0), and D20S870 (Z=3.11 and θ=0).

Table 1. .

Two-point LOD scores (Z) Showing Exclusion of Linkage between the Autosomal Dominant Cataract Locus and STR Markers near Candidate Genes or Loci on Chromosomes Other Than 20

| Marker | Za | θ | Chromosome | Gene/Locus |

| D1S243 | −2.77 | .10 | 1p36 | CCV, CPP1 |

| D1S214 | −2.93 | .10 | ||

| D1S2748 | −2.14 | .20 | 1p32 | FOXE3[MIM 601094] |

| D1S305 | −2.01 | .20 | 1q21 | GJA8 |

| D2S2333 | −2.35 | .20 | 2p12 | CCNP |

| D2S128 | −3.19 | .05 | 2q32-q36 | CRYGC, CRYGD, CRYBA2 |

| D2S2248 | −2.75 | .20 | ||

| D3S1768 | −∞ | .00 | 3p21.1-p21.3 | CATC2 |

| D3S3564 | −2.34 | .05 | ||

| D3S1292 | −1.76 | .05 | 3q22.1 | BFSP2 |

| D3S3686 | −4.04 | .10 | 3q27.2 | CRYGS |

| D5S2014 | −2.05 | .05 | 5q33.1 | SPARC [MIM 182120] |

| D6S1710 | −2.37 | .05 | 6q12 | GLULD1 |

| D9S303 | −1.31 | .05 | 9q21.31 | CAAR |

| D9S1120 | −1.28 | .05 | ||

| D10S566 | −2.94 | .10 | 10q24-q25 | PITX3[MIM 602669] |

| D10S1697 | −3.01 | .10 | ||

| D11S4154 | −2.63 | .05 | 11p13 | PAX6 [MIM 607108] |

| D11S4192 | −2.55 | .10 | 11q23.1 | CRYAB |

| D11S1347 | −3.28 | .05 | ||

| D12S368 | −1.94 | .10 | 12q13.3 | MIP |

| D13S175 | −2.34 | .05 | 13q11 | GJA3 |

| D14S1047 | −2.12 | .05 | 14q24.3 | CHX10[MIM 142993] |

| D15S209 | −3.14 | .05 | 15q21-q22 | CCSSO |

| D15S1036 | −2.41 | .20 | ||

| D16S412 | −2.51 | .10 | 16p12.3 | CRYM[MIM 123740] |

| D16S3095 | −2.99 | .10 | 16q22.1 | HSF4 |

| D17S1840 | −2.45 | .05 | 17p13 | CTAA2 |

| D17S796 | −2.13 | .10 | ||

| D17S799 | −1.79 | .05 | 17q11.2 | CRYBA1 |

| D17S798 | −1.18 | .05 | ||

| D17S785 | −2.14 | .10 | 17q24 | GALK1[MIM 604313] |

| D17S802 | −1.91 | .05 | 17q24 | CCA1 |

| D17S784 | −2.67 | .10 | ||

| D19S412 | −2.41 | .15 | 19q13 | LIM2 |

| D20S112 | 2.58 | .08 | 20p11.23 | BFSP1 |

| D20S885 | 2.71 | .10 | 20p12–20q12 | CPP3 |

| D20S847 | 5.08 | .04 | ||

| D21S1259 | −2.78 | .10 | 21q22.3 | CRYAA |

| D21S1885 | −.81 | .00 | ||

| D22S1154 | −2.20 | .15 | 22q11.23-q21.1 | CRYBA4, CRYBB1-4 |

A gene frequency of 0.0001 and a penetrance of 100% were assumed for the disease locus.

Table 2. .

Two-Point LOD Scores (Z) for Linkage between the Cataract Locus and Markers on Chromosome 20q Listed in Physical Order (Mb) from the Short-Arm Telomere (p-tel)[Note]

| Distance from p-tel |

Za at θ = |

|||||||||

| Marker | cM | Mb | .00 | .05 | .10 | .20 | .30 | .40 | Zmax | θmax |

| D20S885 | 39.9 | 17.91 | −7.79 | 2.51 | 2.72 | 2.35 | 1.60 | .74 | 2.72 | .10 |

| D20S111 | 49.2 | 29.94 | −2.82 | 1.14 | 1.17 | .91 | .54 | .19 | 1.18 | .08 |

| D20S837 | 50.7 | 30.73 | −.81 | 4.15 | 3.98 | 3.18 | 2.14 | 1.01 | 4.15 | .05 |

| rs2057262 | 31.15 | −4.03 | −.02 | .14 | .16 | .09 | .03 | .17 | .15 | |

| D20S195 | 50.2 | 31.29 | 3.65 | 4.17 | 3.88 | 2.96 | 1.90 | .87 | 4.20 | .03 |

| CHMP4B (A>T) | 31.90 | 6.24 | 5.87 | 5.37 | 4.19 | 2.82 | 1.36 | 6.24 | .00 | |

| D20S909 | 50.7 | 33.92 | 1.89 | 1.88 | 1.72 | 1.25 | .73 | .33 | 1.91 | .02 |

| D20S896 | 50.2 | 34.16 | 2.88 | 2.60 | 2.30 | 1.68 | 1.05 | .46 | 2.88 | .00 |

| D20S870 | 50.7 | 34.16 | 3.11 | 2.93 | 2.63 | 1.94 | 1.23 | .59 | 3.11 | .00 |

| D20S847 | 50.2 | 34.32 | 5.50 | 5.18 | 4.72 | 3.60 | 2.33 | 1.05 | 5.50 | .00 |

| rs1291139 | 34.95 | −1.85 | .99 | 1.10 | .96 | .66 | .30 | 1.10 | .11 | |

| D20S834 | 50.7 | 35.43 | −1.08 | 2.07 | 1.91 | 1.30 | .65 | .19 | 2.07 | .05 |

| D20S607 | 54.9 | 38.23 | −1.61 | 1.85 | 2.02 | 1.81 | 1.30 | .66 | 2.03 | .11 |

| D20S855 | 56.0 | 39.08 | −.29 | 3.26 | 3.19 | 2.58 | 1.71 | .77 | 3.27 | .06 |

Note.— STR marker allele frequencies used for linkage analysis were those calculated by Généthon/Marshfield/deCODE. A gene frequency of .0001 and a penetrance of 95% were assumed for the disease locus.

Z values were calculated using the MLINK subprogram from the LINKAGE (5.1) package of programs.34

Haplotype analysis detected seven recombinant individuals within the Sk pedigree (fig. 1A). First, two affected females, VI:4 and VI:6, were obligate recombinants, proximally at D20S885 and distally at D20S855, respectively. Second, three affected females (IV:1, IV:4, and V:3) and one affected male (VI:1) were obligate recombinants distally at D20S834. Third, one affected female (V:3) and her affected son (VI:1) were obligate recombinants proximally at D20S837. However, with the exception of individual V:5 (see below), no further recombinant individuals were detected at four other intervening STR markers, suggesting that the cataract locus lay in the physical interval, D20S837–(4.7 Mb)–D20S834.

At the time of our study, individual V:5 was 17 years of age and phenotypically unaffected; however, he inherited the complete disease haplotype (fig. 1A), suggesting that he was either nonpenetrant or presymptomatic for cataracts. The two-point LOD scores shown in table 2 were calculated with the assumption of unaffected status for individual V:5 and 95% penetrance in family Sk; however, even when 100% penetrance was assumed, we still retained significant evidence of linkage proximally at D20S195 (Zmax=4.31 at θmax=0.04) and distally at D20S847 (Zmax=5.08 at θmax=0.04). Conversely, if individual V:5 developed cataracts later in life, perhaps extending the age-at-onset range in family Sk, and was included with the assumption of preaffected status and 100% penetrance, we would obtain enhanced evidence for linkage (D20S195, Zmax=5.12 at θmax=0.0; D20S847, Zmax=6.97 at θmax=0.0). However, regardless of whether individual V:5 was included or excluded, we found no evidence of linkage at other candidate genes or loci for autosomal dominant cataracts (table 1).

To further refine the disease interval, we genotyped family Sk with biallelic SNP markers (NCBI) located within the STR interval using conventional dye-terminator cycle-sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems). Critical affected individuals IV:1, IV:4, and V:3 were also found to be recombinant at SNP marker rs1291139 (A/T), which lies ∼0.5 Mb centromeric to D20S834. Similarly, critical affected individuals V:3, and VI:1 were also recombinant at marker rs2057262 (A/C) located ∼0.4 Mb telomeric to D20S837 (fig. 1A). However, individual V:5 excepted, no further recombination events were detected at intervening SNP markers, indicating that the cataract locus lay in the reduced (∼0.9 Mb) physical interval, rs2057262–(3.8 Mb)–rs1291139 (fig. 1C).

Mutation analysis.—The refined SNP interval contained ∼80 positional-candidate genes, none of which were obvious functional candidates for cataracts in family Sk (NCBI Map Viewer). We prioritized genes for mutation analysis of exons and intron boundaries (splice sites) on the basis of three main criteria.

-

1.

NCBI reference sequence status, with those genes designated “reviewed” or “provisional” selected over those designated “model” or “pseudogene.”

-

2.

Evidence of expression in (fetal) eye, from the UniGene EST database.

-

3.

Number of exons or amplicons required for coverage of the coding region, starting with smaller genes first.

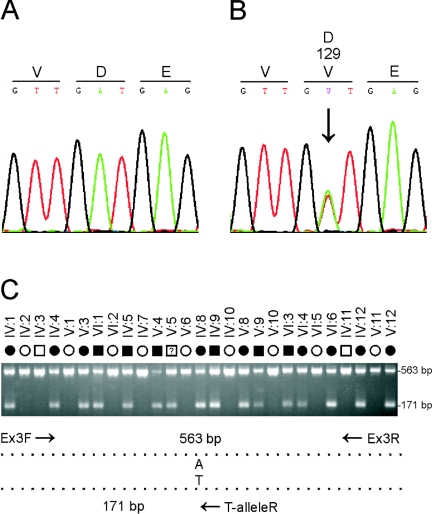

Resequencing analysis of individuals IV:5, V:6, V:10, and VI:6 from the Sk pedigree (fig. 1A) excluded the presence of coding or splice-site mutations in eight genes (data not shown), including EPB41L1 (MIM 602879), E2F1 (MIM 189971), ZNF341, PXMP4, ITGB4BP (MIM 602912), APBA2BP, SCAND1 (MIM 610416), and DYNLRB1 (MIM 607167). However, resequencing of a 5-exon gene symbolized CHMP4B (GeneID: 128866) identified a heterozygous c.386A→T transversion in exon 3 that was not present in wild type (fig. 2B). This single-nucleotide change did not result in the gain or loss of a convenient restriction site; therefore, we designed allele-specific (A/T) PCR analysis to confirm that the mutant “T” allele cosegregated with affected but not unaffected members of family Sk, with the exception of individual V:5 (fig. 2C). Furthermore, when we tested the c.386A→T transversion as a biallelic marker, with a notional allelic frequency of 1%, in a two-point LOD score analysis of the cataract locus (table 2) we obtained further compelling evidence of linkage (Z=6.52 at θ=0). In addition, we confirmed that the c.386A→T transversion was not listed in the NCBI SNP database (dbSNP), and we excluded it as a SNP in a panel of 192 normal, unrelated individuals (i.e., 384 chromosomes), using the allele-specific PCR analysis described in fig. 2C (data not shown). Although it is possible that an undetected mutation lay elsewhere within the disease-haplotype interval (3.8 Mb), our genotype data strongly suggested that the c.386A→T transversion in exon 3 of CHMP4B represented a causative mutation rather than a benign SNP in linkage disequilibrium with the cataract phenotype.

Figure 2. .

Mutation analysis of CHMP4B in family Sk. A, Sequence trace of the wild-type allele, showing translation of aspartic-acid (D) at codon 129 (GAT). B, Sequence trace of the mutant allele, showing the heterozygous c.386A→T transversion (denoted as W by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry [IUPAC] code) that is predicted to result in the missense substitution of valine (GTT) for aspartate at codon 129 (p.D129V). Exons and flanking intron regions were amplified with gene-specific primers (M13-tailed) by use of the AmpliTaq PCR Master Mix in a GeneAmp 9700 thermal-cycler (Applied Biosystems). Resulting amplicons were purified using the QIAquick gel-extraction kit (Qiagen) and then direct sequenced in both directions with M13-primers and the BigDye Terminator (v.3.1) cycle sequencing kit on a 3130xl genetic analyzer running SeqScape mutation-profiling software (Applied Biosystems). C, Allele-specific PCR analysis using the three primers (table 3) indicated by arrows in the schematic diagram; exon 3 was amplified as above with the sense (anchor) primer located in intron 2 (Ex3F), the anti-sense primer located in intron 3 (Ex3R), and the nested mutant primer specific for the T allele in codon 129 (T-alleleR). PCR products were visualized (302 nm) on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (EtBr). Note that only affected members of family Sk are heterozygous for the T allele (171 bp), with the exception of individual V:5, who is believed to be presymptomatic or nonpenetrant for cataracts.

To verify that the c.386A→T transversion in CHMP4B was present at the RNA transcript level in family Sk, we performed allele-specific RT-PCR analysis of peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs), which have been shown to express CHMP4B.35 PCR primers (table 3) were designed to amplify the entire coding region of CHMP4B (codons 1–224) in the presence of a nested mutant (T allele) primer to detect heterozygosity in three consenting relatives, including individual V:5 (fig. 3A). The affected father (IV:5) and his son (V:5) were heterozygous for the wild-type (A allele) and mutant (T allele) transcripts, whereas his unaffected daughter (V:6) was homozygous for the wild-type (A allele) transcript. To gain a more accurate comparison of wild-type versus mutant CHMP4B transcript levels in PBL RNA, we then performed quantitative (q)RT-PCR with SYBR Green-1 in real time (fig. 3B), using a sense anchor primer paired with either a mutant (T allele) or wild-type (A allele) primer (table 3). When standardized against transcript levels for the midabundance ribosomal protein-L19 (RPL19), the ratio of wild-type to mutant CHMP4B transcripts was estimated to be 60(A):40(T), suggesting decreased expression and/or increased turnover of the mutant transcript in affected individuals. Overall, the transcript and genotype data are consistent for these individuals (fig. 1A and fig. 3A) and support the view that the clinically unaffected son (V:5) is either presymptomatic or nonpenetrant for the cataract phenotype. Moreover, the ability to amplify the intact coding region of CHMP4B transcripts from affected individuals was consistent with correct mRNA splicing, suggesting that the c.386A→T transversion, which is located near the beginning of exon 3, did not activate a cryptic splice site.36 Finally, we also confirmed that the intact coding region of CHMP4B transcripts could be amplified from human and mouse post mortem lenses (fig. 3C), consistent with a functional role for CHMP4B in lens biology.

Table 3. .

PCR Primers for Mutation Screening and Transcript Analysis of CHMP4B

| Primer | Location | Strand | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

| Ex1F | Exon 1 | Sense | gtagtcagtggcgcgttg |

| Ex1R | Intron 1 | Antisense | aggcgagtctgatgaaggtg |

| Ex2F | Intron 1 | Sense | cactagaacctcaccctgtgc |

| Ex2R | Intron 2 | Antisense | aaacaaactcaggtgctcgaa |

| Ex3F | Intron 2 | Sense | tcacagggagtcattgcaggg |

| Ex3R | Intron 3 | Antisense | cccaccctggaaaggtgcag |

| Ex3R2 | Intron 3 | Antisense | agggacagcctcagggtatcattt |

| Ex4F | Intron 3 | Sense | cacagggtctggaacctggaa |

| Ex4R | Intron 4 | Antisense | tgggcaagctcaggacacaga |

| Ex5F1 | Intron 4 | Sense | aacatgttgaacgcaccagtc |

| Ex5R1 | Exon 5 | Antisense | AGGTCATTTCAACTGCAACCA |

| Ex5F2 | Exon 5 | Sense | CGCTGACTCCACTGCTGAATCC |

| Ex5R2 | Exon 5 | Antisense | ctggaaagggtcagctcccg |

| StartF | Exon 1 | Sense | caccATGTCGGTGTTCGGGAAGCT |

| EndR | Exon 5 | Antisense | CATGGATCCAGCCCAGTTCTCCAA |

| A-alleleR | Exon 3 | Antisense | CAGCAATGTCCTGCATTAACTCAT |

| T-alleleR | Exon 3 | Antisense | CAGCAATGTCCTGCATTAACTCAA |

Noncoding sequence is shown in lowercase, coding sequence in uppercase.

Figure 3. .

RT-PCR analysis of CHMP4B transcripts in peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) and eye lens. A, Agarose-gel electrophoresis showing nested amplification products of CHMP4B transcripts in PBL RNA from family Sk, confirming that individuals IV:5 and V:5 are heterozygous for the mutant T allele (413 bp), whereas individual V:6 is homozygous for the wild-type A allele (676 bp). PBL RNA was purified using the Versagene kit (Gentra), reverse transcribed with the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad), and PCR amplified as above with three primers (StartF, nested T-alleleR, and EndR) (table 3). B, Quantitative amplification of CHMP4B transcripts from PBL RNA with allele-specific primers (StartF + A-alleleR, or StartF + T-alleleR) (table 3) showing the relative levels of wild-type (A allele) and mutant (T allele) transcripts in individuals IV:5, V:5, and V:6 from family Sk. RT-PCR products were amplified in a 10-fold dilution series (in triplicate) by use of the iQ SYBR Green Supermix in an iCycler fitted with a MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). Allele-specific CHMP4B transcripts were detected by melt-curve analysis and standardization against control RPL19 transcript, which was amplified separately in a similar 10-fold dilution series of the same PBL RT-PCR products by use of RPL19 forward (5′-catccgcaagcctgtgac-3′) and reverse (5′-gtgaccttctctggcattcg-3′) primers. C, Agarose-gel electrophoresis showing amplicons containing the entire coding region (codons 1–224) of CHMP4B transcripts (676 bp) from human (Hs) lens (∼30 years old), mouse (Mm) lens (postnatal day 6), and HEK 293 cells. Post mortem human lenses were obtained from the Lions Eye Bank of Oregon, and RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Following euthanasia (CO2 gas), mouse lenses were dissected into RNAlater tissue preservative, and RNA was extracted using the RNAqueous kit (Ambion). RNA was extracted from cultured HEK 293 cells as for mouse lenses. RT-PCR of lens and HEK 293 RNA was performed as for PBL RNA above, with use of StartF and EndR primers (table 3), and the resulting amplicons were verified by sequencing.

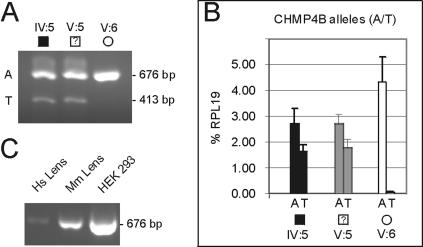

CHMP4B is cytogenetically distinct from BFSP1 and an interval on 20p (fig. 1C) that was linked recently with autosomal dominant progressive congenital zonular nuclear cataract (PCZNC) segregating in a Chinese family.32 However, CHMP4B is located within a much larger region spanning 20p12–20q12 that was previously linked with autosomal dominant posterior polar cataract (CPP3 [MIM 605387]) segregating in a Japanese family.31 Like the cataracts in family Sk, CPP3 was characterized by a juvenile onset and progressive disc-shaped posterior subcapsular opacities along with some cortical opacification.37 To investigate the possibility of allelism, we performed a similar mutation screen of CHMP4B in the CPP3 family and identified a heterozygous c.481G→A transition in exon 3 that was not present in wild type (fig. 4A and 4B) or in the SNP database. This single-nucleotide change removed an adjacent Mnl1 restriction enzyme-site, and restriction fragment length analysis confirmed that the heterozygous A allele cosegregated with affected members of the CPP3 family but was not present in unaffected relatives or our control panel (fig. 4C and data not shown). The identification of a second coding nucleotide change in a geographically and ethnically distinct family provided strong supporting evidence for CHMP4B as the causative gene for cataracts linked to 20q. In addition, the locus for lens opacity-4 (Lop4)38 has been linked to a region of murine chromosome 2 that is syntenic with human 20q11.2 raising the possibility of a mouse model for the cataracts described here.

Figure 4. .

Mutation analysis of CHMP4B in the CPP3 family. A, Sequence trace of the wild-type allele showing translation of glutamic-acid (E) at codon 161 (GAG). B, Sequence trace of the mutant allele showing the heterozygous c.481G→A transition (denoted R by the IUPAC code) that is predicted to result in the missense substitution of lysine (AAG) for glutamate at codon 161 (p.E161K). C, Restriction-fragment–length analysis showing loss of an Mnl1 site (3′-GGAGN6) that cosegregates only with affected individuals from the Japanese family31 heterozygous for the c.481G→A transversion (103 bp). Exon 3 was amplified with PCR primers (table 3) shown in the schematic diagram and resulting amplicons (326 bp) digested (at 37°C for 1 h) with Mnl1 (5 U; New England BioLabs). Restriction fragments (>75 bp) were visualized on 2% agarose-EtBr gels.

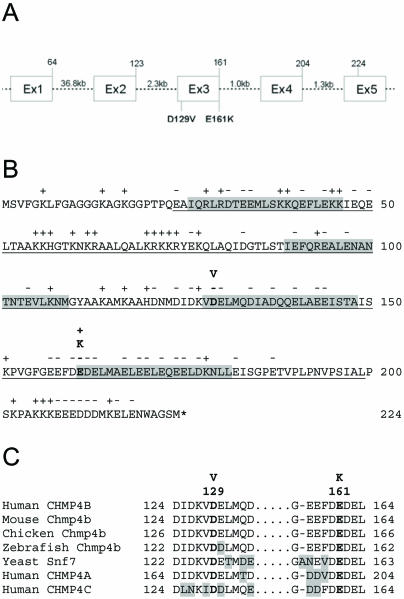

CHMP4B encodes a highly charged helical protein (∼25 kDa) with N-terminal basic and C-terminal acidic halves (fig. 5B). The c.386A→T transversion in exon 3 occurred at the second base of codon 129 (GAT→GTT), and is predicted to result in the missense substitution of aspartic acid to valine (p.D129V) at the level of translation. Similarly, the c.481G→A transition occurred at the first base of codon 161 (GAG→AAG) of exon 3, and is predicted to translate as a missense substitution of glutamic acid to lysine (p.E161K). Cross-species alignment of the amino acid sequences for CHMP4B present in the Entrez Protein database, performed by means of ClustalW, revealed that p.D129 and p.E161 are phylogenetically conserved from yeast to man (fig. 5C). Moreover, the predicted p.D129V and p.E161K substitutions represented nonconservative amino acid changes, with the acidic side-group (−CH2COOH) of aspartic acid replaced by the neutral, hydrophobic side-group (−CH−C2H6) of valine, and the acidic side-group (−C2H4COOH) of glutamic acid replaced by the basic side-group (−C4H8NH2) of lysine, respectively, suggestive of functional consequences.

Figure 5. .

Gene structure and protein domains of CHMP4B. A, Exon organization and mutation profile of CHMP4B. Intron sizes are indicated (kb), and codons are numbered above each exon. B, Amino acid sequence of CHMP4B, showing the conserved SNF7 domain (underlined) of this protein family (Conserved Domain Databse, pfam03357) containing at least four predicted helical domains (grey). The proposed p.D129V and p.E161K substitutions are predicted to be located in the C-terminal acidic half of the protein, near the start of adjacent helices within the SNF7 domain. Charged amino acids (+, −) and the translation stop codon (*) are also indicated. C, Amino acid sequence alignment of human CHMP4B and orthologs from other species, showing phylogenetic conservation of D129 and E161.

Functional expression studies.—Eleven CHMP genes have been identified in the human genome and, on the basis of phylogenetic analyses, have been divided into seven subfamilies, some with multiple members.39,40 CHMP4B is one of three human orthologs of yeast Snf7/Vps32 (sucrose non-fermenting-7 or vacuolar protein sorting-32), which functions in protein sorting and transport in the endosome-lysosome pathway.39 In the current model, CHMP4B is a core subunit of the endosomal-sorting complex required for transport-III (ESCRT-III), which facilitates the biogenesis of multivesicular bodies (MVBs).39 The only CHMP gene so far implicated in human disease is CHMP2B (yeast ortholog Vps2/Did4 [MIM 609512]), which has been reported to harbor mutations infrequently associated with frontotemporal dementia (FTD [MIM 600795]) and amyotropic lateral sclerosis (ALS [MIM 609512]).41–43

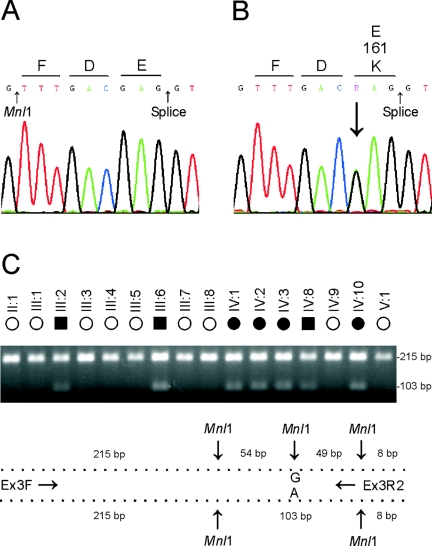

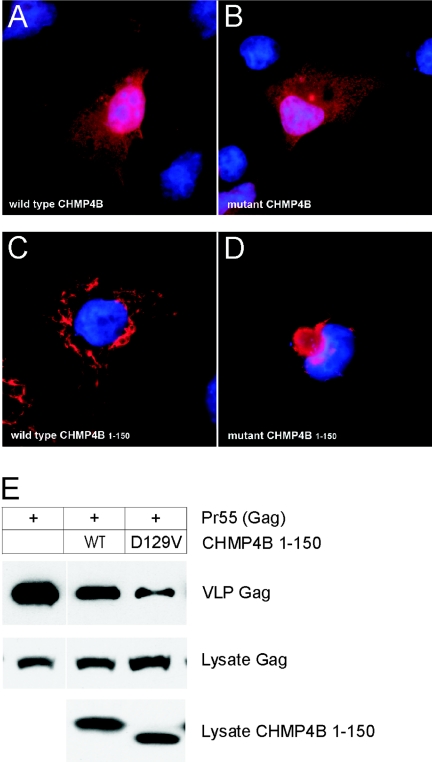

CHMP4B is found diffusely throughout the cytoplasm and/or in association with endosome-like compartments when expressed in cultured mammalian cells.44,45 To determine the effect of the p.D129V substitution on the subcellular distribution of CHMP4B, we transfected African green monkey kidney (COS-7) cells with expression plasmids46 encoding either wild-type or mutant forms of CHMP4B tagged at the N-terminus with the FLAG epitope. Immunofluorescence microscopy with FLAG antibody revealed that full-length wild-type (FLAG-CHMP4B) and mutant protein (FLAG-D129V-CHMP4B) were diffusely distributed (fig. 6A and 6B). At higher expression levels, both were associated with endosome-like compartments (data not shown). Overall, there were no notable differences in the subcellular localization of wild type and p.D129V mutant protein. In contrast, similar expression studies of a splicing mutation in CHMP2B underlying FTD, which resulted in truncation (36 amino acids) and miscoding (29 amino acids) at the C-terminus of the full-length protein (residues 1–213), has been associated with redistribution of CHMP2B and the formation of dysmorphic organelles of the late endosomal pathway.41

Figure 6. .

Transient expression of CHMP4B in cultured cells. A–D, Subcellular localization of CHMP4B proteins in COS-7 cells, visualized by immunostaining with FLAG antibody and epifluorescence microscopy. A, Full-length wild-type FLAG-CHMP4B. B, Full-length mutant FLAG-D129V-CHMP4B. C, Truncated wild-type FLAG-CHMP4B1–150. D, Truncated mutant FLAG-D129V-CHMP4B1–150. For full-length constructs, the coding sequence (codons 1–224) of human CHMP4B was PCR amplified from HeLa cDNA (Clontech) with forward (5′-gtagatctatgtcggtgttcgggaagctgttcgg-3′) and reverse (5′-cactcgagttacatggatccagcccagttctcc-3′) primers and then subcloned into the BamHI and XhoI restriction sites in the poly-linker of pcDNA3.1-FLAG.46 The D129V substitution was generated using the QuickChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). For truncated CHMP4B constructs, amplicons corresponding to codons 1–150 were amplified using the full-length constructs as templates and were subcloned into pcDNA3.1-FLAG as above. Plasmid DNA was prepared using the QIAprep spin kit (Qiagen), and inserts were verified by sequencing using the T7 primer. For transient expression, cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco-BRL) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL), 5% supplemented calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories), and 2 mM glutamine. Cells were transfected with expression plasmids by use of Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). At 18–24 h after transfection, COS-7 cells grown on glass cover slips were fixed in 3.5% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, and immunostained with rabbit FLAG antibody (Sigma) followed by Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes). Cell nuclei were counterstained (blue) with DAPI (4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole [Molecular Probes]). E, Immunoblot analysis of VLPs produced by HEK 293T cells cotransfected with plasmids encoding Gag (p24 antibody) and CHMP4B1–150 (FLAG antibody). Top blot shows Gag recovered in VLPs, and middle blot shows Gag in cell lysates. Bottom blot shows that the levels of CHMP4B1–150 were similar in cell lysates; however, the D129V substitution increased the electrophoretic mobility of the mutant fragment on SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate) polyacrylamide gels compared with its wild-type counterpart. For VLPs, HEK 293T cells were transfected with 4 μg pCMV55 encoding HIV Gag, alone or together with 1μg of the indicated CHMP4B construct. At 18–24 h after transfection, media containing VLPs was harvested and clarified by passing through a 0.45 μm filter. VLPs were pelleted by centrifugation (3 h) through a 20% sucrose cushion at 26,000 rpm in SW41 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter). VLPs and cell lysates were resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer, were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then were analyzed by immunoblotting using rabbit antibody against p24, the capsid domain of HIV Gag, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, and the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce). Immunoblot signals were quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor Bioscience).

The p.D129V missense substitution was predicted to be located centrally in CHMP4B and to result in the net loss of a negatively charged residue (fig. 5B). Domain expression studies have revealed that the N-terminal half of CHMP4A (MIM 610051), an isoform of CHMP4B, is responsible for self-association into polymers and binding to membrane phospholipids.46 To better appreciate the effects of the p.D129V substitution, we compared the subcellular localization of wild-type and mutant N-terminal fragments of CHMP4B (residues 1–150) comparable to those previously studied.46,47 As expected, the distribution of the truncated wild-type fragment (FLAG-CHMP4B1–150) differed from that of the full-length wild-type protein; the former appeared to be in large polymers and sometimes associated with vacuolar structures (fig. 6C), whereas the latter was diffuse (fig. 6A). Similarly, the truncated mutant fragment (FLAG-D129V-CHMP4B1–150) differed from the full-length mutant protein; the former was concentrated on a punctate perinuclear structure (fig. 6D), and the latter was again diffuse (fig. 6B). Consistently, however, the truncated mutant fragment (fig. 6D) displayed a different subcellular distribution pattern from that of the truncated wild-type fragment (fig. 6C).

In addition to MVB formation, CHMP4B is thought to participate in the budding of a number of RNA viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1), from the surface of infected cells.45 To further investigate the effect of the p.D129V substitution on CHMP4B activity in a functional assay, we compared the effect of expressing wild-type and mutant protein on release of HIV-1 virus-like-particles (VLPs). To monitor VLP production, human embryonic kidney (HEK 293T) cells were cotransfected with a plasmid encoding the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein (Pr55) and a plasmid encoding wild-type or mutant CHMP4B. HIV-1 Gag forms VLPs in the absence of other viral proteins,48 and expression of Gag and CHMP4B within cells and release of Gag into the media as VLPs was detected by immunoblotting (fig. 6E). As expected on the basis of previous results,49 expression of the truncated wild-type fragment (FLAG-CHMP4B1–150) inhibited VLP release. Interestingly, the truncated mutant fragment (FLAG-D129V-CHMP4B1–150) was a more potent inhibitor than truncated wild type allowing release of only 53% ± 7% (average ± SD) as much Gag in VLPs. Correspondingly, the level of Gag expression in cells expressing the mutant fragment was 1.4 ± 0.3 times that of cells expressing the wild-type fragment. In contrast, neither the wild type nor the mutant forms of full-length CHMP4B significantly inhibited Gag production or VLP release (data not shown).

Precisely how the p.D129V substitution affects the function of CHMP4B is unclear. In this study, we found that the p.D129V substitution changed the subcellular distribution and effects of CHMP4B on VLP release when the protein’s acidic C-terminus was removed. Previous studies suggest that the acidic C-termini of CHMPs are regulatory domains that interact specifically with their cognate N-terminal basic domains in an auto-inhibitory manner.46,49,50 Thus, it is possible that when CHMP4B is relieved from auto-inhibition (mimicked here by truncation), the p.D129V substitution is exposed resulting in deleterious gain-of-function effects. On the basis of expression analysis of the N-terminal region of CHMP4A,46 we speculate that, once unmasked, the p.D129V substitution alters the polymerization and/or membrane-binding properties of CHMP4B; however, other mechanisms cannot be excluded. Further work will be required to understand how the p.D129V change affects the behavior of intact CHMP4B. Functional expression studies are also underway to determine how the p.E161K substitution affects CHMP4B. Although little is known about the role of CHMP proteins in lens development, endosome-like compartments have been observed in the newborn mouse lens.51 Further characterization of endosomal pathways in the lens should provide insight into the pathogenetic mechanisms linking CHMP4B dysfunction with cataractogenesis.

In conclusion, our data identify the first mutations (p.D129V, p.E161K) in a novel gene (CHMP4B) for inherited cataracts linked to 20q, and they suggest that gain-of-function defects in an endosome-sorting complex (ESCRT-III) subunit triggers loss of lens transparency.

Acknowledgments

We thank family members for participating in this study, Dr. Olivera Boskovska for help with ascertaining family Sk, and Dr. Donna Mackay for preliminary linkage analysis. Dr. Kenneth Johnson kindly provided the pcDNA3.1-FLAG plasmid, and Dr. Lee Ratner kindly provided the HIV GAG expression plasmid (pCMV55) and p24 antibody. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Eye Institute grants EY012284 (to A.S.) and EY02687, and American Heart Association grants 0550148Z and 0750178Z (to P.I.H.).

Web Resources

Accession numbers and URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- ClustalW multiple sequence alignment, http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/http

- Conserved Domain Database (CDD), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/cdd.shtml

- Entrez Protein database, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=Protein

- Généthon, Marshfield, and deCODE genetic linkage maps, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/guide/human/

- LINKAGE/MLINK, http://linkage.rockefeller.edu/soft/

- NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/index.html

- NCBI Map Viewer, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mapview/

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.govOMIM

- SNP database (dbSNP), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/

- UniGene, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=unigene

References

- 1.Zetterstrom C, Lundvall A, Kugelberg M (2005) Cataracts in children. J Cataract Refract Surg 31:824–840 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shiels A, Hejtmancik JF (2007) Genetic origins of cataract. Arch Ophthalmol 125:165–173 10.1001/archopht.125.2.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litt M, Kramer P, LaMorticella DM, Murphey W, Lovrien EW, Weleber RG (1998) Autosomal dominant congenital cataract associated with a missense mutation in the human alpha crystallin gene CRYAA. Hum Mol Genet 7:471–474 10.1093/hmg/7.3.471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry V, Francis P, Reddy MA, Collyer D, Vithana E, MacKay I, Dawson G, Carey AH, Moore A, Bhattacharya SS, et al (2001) Alpha-B crystallin gene (CRYAB) mutation causes dominant congenital posterior polar cataract in humans. Am J Hum Genet 69:1141–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackay DS, Boskovska OB, Knopf HL, Lampi KJ, Shiels A (2002) A nonsense mutation in CRYBB1 associated with autosomal dominant cataract linked to human chromosome 22q. Am J Hum Genet 71:1216–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Litt M, Carrero-Valenzuela R, LaMorticella DM, Schiltz DW, Mitchell TN, Kramer P, Maumenee IH (1997) Autosomal dominant cerulean cataract is associated with a chain termination mutation in the human β-crystallin gene CRYBB2. Hum Mol Genet 6:665–668 10.1093/hmg/6.5.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riazuddin SA, Yasmeen A, Yao W, Sergeev YV, Zhang Q, Zulfigar F, Riaz A, Riazuddin S, Hejtmancik JF (2005) Mutations in βB3-crystallin associated with autosomal recessive cataract in two Pakistani families. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46:2100–2106 10.1167/iovs.04-1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannabiran C, Rogan PK, Olmos L, Basti S, Rao GN, Kaiser-Kupfer M, Hejtmancik JF (1998) Autosomal dominant zonular cataract with sutural opacities is associated with a splice mutation in the βA3/A1-crystallin gene. Mol Vis 4:21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billingsley G, Santhiya ST, Paterson AD, Ogata K, Wodak S, Hosseni SM, Manisastry SM, Vijayalakshmi P, Gopinath PM, Graw J, et al (2006) CRYBA4 a novel human cataract gene is also involved in microphthalmia. Am J Hum Genet 79:702–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santhiya ST, Shyam Manohar M, Rawlley D, Vijayalakshmi P, Namperumalsamy P, Gopinath PM, Loster J, Graw J (2002) Novel mutations in the γ-crystallin genes cause autosomal dominant congenital cataracts. J Med Genet 39:352–358 10.1136/jmg.39.5.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun H, Ma Z, Li Y, Liu B, Li Z, Ding X, GaoY, Ma W, Tang X, Li X, et al (2005) Gamma-S crystallin gene (CRYGS) mutation causes dominant progressive cortical cataract in humans. J Med Genet 42:706–710 10.1136/jmg.2004.028274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackay D, Ionides A, Kibar Z, Rouleau G, Berry V, Moore A, Shiels A, Bhattacharya S (1999) Connexin46 mutations in autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Am J Hum Genet 64:1357–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shiels A, Mackay D, Ionides A, Berry V, Moore A, Bhattacharya S (1998) A missense mutation in the human connexin50 gene (GJA8) underlies autosomal dominant zonular pulverulent cataract on chromosome 1q. Am J Hum Genet 62:526–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bu L, Jin Y, Shi Y, Chu R, Ban A, Eiberg H, Andres L, Jiang H, Zheng G, Qian M, et al (2002) Mutant DNA binding domain of HSF4 is associated with autosomal dominant lamellar and Marner cataract. Nat Genet 31:276–278 10.1038/ng921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry V, Francis P, Kaushal S, Moore A, Bhattacharya S (2000) Missense mutations in MIP underlie autosomal dominant polymorphic and lamellar cataracts linked to 12q. Nat Genet 25:15–17 10.1038/75538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pras E, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Bakhan T, Lahat H, Assia E, Geffin-Carmi N, Frydman M, Goldman B, Pras E (2002) A missense mutation in the LIM2 gene is associated with autosomal recessive presenile cataract in an inbred Iraqi Jewish family. Am J Hum Genet 70:1363–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramachandran RD, Perumalsamy V, Hejtmancik JF (2007) Autosomal recessive juvenile onset cataract associated with mutation in BFSP1. Hum Genet 121:475–482 10.1007/s00439-006-0319-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conley YP, Erturk D, Keverline A, Mah TS, Keravala A, Barnes LR, Bruchis A, Hess JF, FitzGerald PG, Weeks DE, et al (2000) A juvenile-onset progressive cataract locus on chromosome 3q21-q22 is associated with a missense mutation in the beaded filament structural protein-2. Am J Hum Genet 66:1426–1431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eiberg H, Lund AM, Warburg M, Rosenberg T (1995) Assignment of congenital cataract Volkmann type (CCV) to chromosome 1p36. Hum Genet 96:33–38 10.1007/BF00214183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ionides ACW, Berry V, Mackay DS, Moore AT, Bhattacharya SS, Shiels A (1997) A locus for autosomal dominant posterior polar cataract on chromosome 1p. Hum Mol Genet 6:47–51 10.1093/hmg/6.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKay JD, Patterson B, Craig JE, Russell-Eggitt IM, Wirth MG, Burdon KP, Hewitt AW, Cohn AC, Kerdraon Y, Mackey DA (2005) The telomere of human chromosome 1p contains at least two independent autosomal dominant congenital cataract genes. Br J Ophthalmol 89:831–834 10.1136/bjo.2004.058495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogaev EI, Rogaeva EA, Korovaitseva GI, Farrer LA, Petrin AN, Keryanov SA, Turaeva S, Chumakov I, St George-Hyslop P, Ginter EK (1996) Linkage of polymorphic congenital cataract to the gamma-crystallin gene locus on human chromosome 2q33–35. Hum Mol Genet 5:699–703 10.1093/hmg/5.5.699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khaliq S, Hameed A, Ismail M, Anwar K, Mehdi SQ (2002) A novel locus for autosomal dominant nuclear cataract mapped to chromosome 2p12 in a Pakistani family. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43:2083–2087 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao L, Qin W, Cui H, Feng G, Liu P, Gao W, Ma L, Li P, He L, Fu S (2005) A novel locus of coralliform cataract mapped to chromosome 2p24-pter. J Hum Genet 50:305–310 10.1007/s10038-005-0251-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pras E, Pras E, Bakhan T, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Lahat H, Assia EI, Garzozi HJ, Kastner DL, Goldman B, Frydman M (2001) A gene causing autosomal recessive cataract maps to the short arm of chromosome 3. Isr Med Assoc J 3:559–562 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heon E, Paterson AD, Fraser M, Billingsley G, Priston M, Balmer A, Schorderet DF, Verner A, Hudson TJ, Munier FL (2001) A progressive autosomal recessive cataract locus maps to chromosome 9q13-q22. Am J Hum Genet 68:772–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanita, Singh JR, Sarhadi VK, Singh D, Reis A, Rueschendorf F, Becker-Follmann J, Jung M, Sperling K (2001) A novel form of central pouchlike cataract with sutural opacities maps to chromosome 15q21-22. Am J Hum Genet 68:509–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armitage MM, Kivlin JD, Ferrell RE (1995) A progressive early onset cataract gene maps to human chromosome 17q24. Nat Genet 9:37–40 10.1038/ng0195-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berry V, Ionides AC, Moore AT, Plant C, Bhattacharya SS, Shiels A (1996) A locus for autosomal dominant anterior polar cataract on chromosome 17p. Hum Mol Genet 5:415–419 10.1093/hmg/5.3.415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riazuddin SA, Yasmeen A, Zhang Q, Yao W, Sabar MF, Ahmed Z, Riazuddin S, Hejtmancik JF (2005) A new locus for autosomal recessive nuclear cataract mapped to chromosome 19q13 in a Pakistani family. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46:623–626 10.1167/iovs.04-0955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada K, Tomita H, Yoshiura K, Kondo S, Wakui K, Fukushima Y, Ikegawa S, Nakamura Y, Amemiya T, Niikawa N (2000) An autosomal dominant posterior polar cataract locus maps to human chromosome 20p12-q12. Eur J Hum Genet 8:535–539 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li N, Yang Y, Bu J, Zhao C, Lu S, Zhao J, Yan L, Cui L, Zheng R, Li J, et al (2006) An autosomal dominant progressive congenital zonular nuclear cataract linked to chromosome 20p12.2-p11.23. Mol Vis 12:1506–1510 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackay DS, Andley UP, Shiels A (2003) Cell death triggered by a novel mutation in the alphaA-crystallin gene underlies autosomal dominant cataract linked to chromosome 21q. Eur J Hum Genet 11:784–793 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lathrop GM, Lalouel JM, Julier C, Ott J (1984) Strategies for multilocus linkage analysis in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 81:3443–3446 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katoh K, Shibata H, Hatta K, Maki M (2004) CHMP4b is a major binding partner of the ALG-2-interacting protein Alix among the three CHMP4 isoforms. Arch Biochem Biophys 421:159–165 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cartegni L, Chew SL, Krainer AR (2002) Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat Rev Genet 3:285–298 10.1038/nrg775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada K, Tomita HA, Kanazawa S, Mera A, Amemiya T, Niikawa N (2000) Genetically distinct autosomal dominant posterior polar cataract in a four-generation Japanese family. Am J Ophthalmol 129:159–165 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00313-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.West JD, Fisher G (1986) Further experience of the mouse dominant cataract mutation test from an experiment with ethylnitrosourea. Mutat Res 164:127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurley JH, Emr SD (2006) The ESCRT complexes: structure and mechanism of a membrane-trafficking network. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 35:277–298 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horii M, Shibata H, Kobayashi R, Katoh K, Yorikawa C, Yasuda J, Maki M (2006) CHMP7 a novel ESCRT-III related protein associates with CHMP4b and functions in the endosomal sorting pathway. Biochem J 400:23–32 10.1042/BJ20060897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skibinski G, Parkinson NJ, Brown JM, Chakrabarti L, Lloyd SL, Hummerich H, Nielsen JE, Hodges JR, Spillantini MG, Thursgaard T, et al (2005) Mutations in the endosomal ESCRT-III complex subunit CHMP2B in frontotemporal dementia. Nat Genet 37:806–808 10.1038/ng1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parkinson N, Ince PG, Smith MO, Highley R, Skibinski G, Andersen PM, Morrison KE, Pall HS, Hardiman O, Collinge J, et al (2006) ALS phenotypes with mutations in CHMP2B (charged multivesicular body protein 2B). Neurology 67:1074–1077 10.1212/01.wnl.0000231510.89311.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Talbot K, Ansorge O (2006) Recent advances in the genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: common pathways in neurodegenerative disease. Hum Mol Genet 15:R182–R187 10.1093/hmg/ddl202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katoh K, Shibata H, Suzuki H, Nara A, Ishidoh K, Kominami E, Yoshimori T, Maki M (2003) The ALG-2-interacting protein Alix associates with CHMP4b a human homologue of yeast Snf7 that is involved in multivesicular body sorting. J Biol Chem 278:39104–39113 10.1074/jbc.M301604200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Schwedler UK, Stuchell M, Muller B, Ward DM, Chung HY, Morita E, Wang HE, Davis T, He GP, Cimbora DM, et al (2003) The protein network of HIV budding. Cell 114:701–713 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00714-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin Y, Kimpler LA, Naismith TV, Lauer JM, Hanson PI (2005) Interaction of the mammalian endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) III protein hSnf7-1 with itself membranes and the AAA+ ATPase SKD1. J Biol Chem 280:12799–12809 10.1074/jbc.M413968200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muziol T, Pineda-Molina E, Ravelli RB, Zamborlini A, Usami Y, Gottlinger H, Weissenhorn W (2006) Structural basis for budding by the ESCRT-III factor CHMP3. Dev Cell 10:821–830 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Accola MA, Strack B, Gottlinger HG (2000) Efficient particle production by minimal Gag constructs which retain the carboxy-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid-p2 and a late assembly domain. J Virol 74:5395–5402 10.1128/JVI.74.12.5395-5402.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zamborlini A, Usami Y, Radoshitzky SR, Popova E, Palu G, Gottlinger H (2006) Release of autoinhibition converts ESCRT-III components into potent inhibitors of HIV-1 budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19140–19145 10.1073/pnas.0603788103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitley P, Reaves BJ, Hashimoto M, Riley AM, Potter BVL, Holman GD (2003) Identification of mammalian Vps24p as an effector of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate-dependent endosome compartmentalization. J Biol Chem 278:38786–38795 10.1074/jbc.M306864200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beebe D, Garcia C, Wang X, Rajagopal R, Feldmeier M, Kim J-Y, Chytil A, Moses H, Ashery-Padan R, Rauchman M (2004) Contributions by members of the TGFbeta superfamily to lens development. Int J Dev Biol 48:845–856 10.1387/ijdb.041869db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]