Abstract

Purpose

This study describes the partner selection process in 15 U.S. communities developing community-researcher partnerships for the Connect to Protect® (C2P): Partnerships for Youth Prevention Interventions, an initiative of the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions.

Methods

Each site generated an epidemiological profile of urban youth in their community, selected a focus population and geographic area of youth at risk for HIV, conducted a series of successive structured interviews, and engaged in a process of relationship-building efforts culminating in a collaborative network of community agencies.

Results

Sites chose as their primary target population young women who have sex with men (n=8 sites), young men who have sex with men (n=6), and intravenous drug users (n=1). Of 1,162 agencies initially interviewed, 281 of 335 approached (84%) agreed to join the partnership (average 19/site). A diverse array of community agencies were represented in the final collaborative network; specific characteristics included: 93% served the sites' target population, 54% were predominantly youth-oriented, 59% were located in the geographical area of focus, and 39% reported provision of HIV/STI prevention services. Relationship-building activities, development of collaborative relationships, and lessons learned, including barriers and facilitators to partnership, are also described.

Conclusions

Study findings address a major gap in the community partner research literature. Health researchers and policy makers need an effective partner selection framework whereby community-researcher partnerships can develop a solid foundation to address public health concerns.

Keywords: Collaboration, Coalition, Community Involvement, Partnership Selection, Community Researcher Partnership, Neighborhood Collaboratives

Introduction

Community mobilization approaches to systems change are used to address a number of intractable public health issues, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 such as poor educational attainment,7 pregnancy,8,9 violence, 10 asthma,11 immunization,12 healthy cities, 13,14 and health disparities.15 Policy and program experts report that the complexity of current social and health problems calls for comprehensive approaches towards interventions and broad policies that address the problems in a structural context, 5,16,17 making partnership efforts even more salient.14,18,19

Research has taken a more prominent role within community collaboration models, placing community-researcher partner models in a strategic and critical role unheard of in the past. 5,20,21,22,23 One reason for this shift is that coalitions have been found to be an effective universal intervention20,24 that can affect community issues by leveraging resources, 24,25 increasing efficiency of service integration and coordination, 27 and allowing partners to share the risk.20 Given the importance placed by funding agents on investing in demonstrably effective interventions,25 the importance of research in community interventions remains high.

Despite the volume of literature describing effective collaboration development, management and goal setting, there is little that describes partner attributes or offers criteria for partner selection. 22,25,26 Partners and agencies that do not have synergy with one another, the vision, or objectives can contribute to failure of the collaborative effort.16,29 Connect to Protect® (C2P), a federally funded community–based collaborative research project of the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN), is working to develop an effective approach to community systems change for HIV prevention through community mobilization efforts.30 This paper describes C2P's model of partnership selection.

Connect to Protect® (C2P) Overview

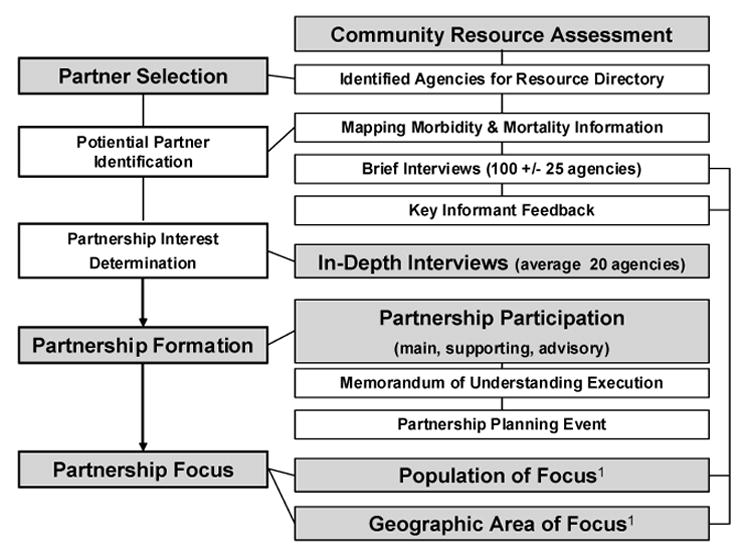

The ATN is an NIH-funded, multi-center collaborative network established in March 2001 to implement clinical, biological and behavioral research with youth living with and at risk for HIV infection. Member sites are major medical research institutions with expertise in caring for youth with HIV/AIDS in 15 urban communities throughout the United States. C2P is a community-focused, multi-phase prevention research initiative managed by a National Coordinating Center (NCC) based at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (Jonathan Ellen MD, Protocol Chair). C2P seeks to combine the strengths of communities and researchers in the effort to protect young people from HIV infection by fostering community-researcher collaborative partnerships focused on modifying the community's structural elements (i.e. policies, programs and practices) to lead to sustainable outcomes, such as decreased rates of HIV. To accomplish this mission each of the 15 ATN clinical research sites completed Phase I of C2P, focusing on accomplishing three goals: (1) gathering and mapping data on disease epidemiology, risk, and community resources 31; (2) assessing neighborhood needs and opportunities by examining how disease and risk rates correspond with service availability 32; and (3) building researcher-community partnerships to address local youth-related HIV prevention needs and priorities. Phase II will further develop the partnerships through a series of meetings as additional data is collected and shared and community partner capacity is built for mobilization efforts (e.g concepts of structural change, advocacy, building leadership, etc.). Phase III will involve a strategic planning session in which coalition members and other community representatives will draft a plan to address community needs through a community mobilization effort. For a detailed description of the overall C2P project, see Ziff, 2006. 30 This paper's objective is to describe goal three of Phase I, the partnership process, which incorporates three components: partnership selection, formation and focus (Figure 1). This research was reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at all 15 local sites and determined to be exempt.

Figure 1.

Project Overview

1 Sites also examined supplemental public use epidemiologic data and other behavioral risk and demographic data.

Methods

Partnership Selection

The process of selecting potential community partners included 1) initial relationship-building activities, 2) assessing community resource information to determine potential partners, and 3) conducting an in-depth interview process to determine the potential roles that partners would play during the collaborative process.

Initial relationship-building activities

Initial relationship building with the community occurred over several years and involved site staff “spreading the word” about C2P. They were encouraged to attend community events familiarizing agencies and key community members with the project and the mission and sharing national and local materials. Site staff were also charged with establishing systems to provide assistance to community agencies, as well as acting as “honest brokers” by learning the needs of the community agencies and connecting them with resources. This process was meant to build upon the already established community presence of the site Principal Investigators and their clinics and coincide with the formal assessments outlined below.

Community resource assessment

The community resource assessment included collecting data for a community resource directory and then conducting brief surveys to describe neighborhood services, map where morbidity and mortality intersect with community resources in each city (i.e. creating an epidemiologic profile), and determine interest in potential collaborative public health work.32 Staff conducted brief surveys with a convenience sample of 100 (+/− 25) entities that provided services to adolescents and/or young adults in the highest risk areas of the city, as evidenced by the epidemiologic profile. In order to identify entities, sites obtained existing directories, conducted web searches, read local newspapers, and asked other CBOs for referrals (i.e. snowball technique) to provide starting points. So as to keep the listing manageable, sites focused on agencies that provided services to adolescents and young adults (i.e. sexual health-related prevention and education, outreach, medical services, etc.). Utilizing a brief survey template designed by the NCC,32 agencies were asked about their mission, contact information, populations served, types of services provided and areas of service provision. The brief survey was conducted either in person or by phone, with organizations with whom a significant relationship existed or was desired. Remaining surveys were conducted by U.S. mail, FAX, or e-mail for self-administration with those organizations which sites had reasonable a priori expectation would only contribute to the resource directory and would be less interested in collaborating as a community partner (i.e. a CBO whose services were not predominately youth-oriented, etc.).

In-depth interviews

Next, sites narrowed down this brief survey list to approximately 20 organizations for an in-depth interview, which was intended to aid C2P staff in making decisions about the particular roles potential partners would subsequently be invited to play (i.e., ranging from commitment-intensive to very limited involvement) and to allow C2P staff access to the organization's insights on collaborations and perceptions of what constitutes—and what can hinder—a successful partnership. Specific criteria for selection for the in-depth interview list was based on site staffs' perceptions, taking into account reflective feedback by the NCC, of whether or not each organization had a mission or goal that was congruent with C2P objectives, was able to provide information on and have access to at-risk adolescent and young adult populations, provided sexual health-promotion and/or disease prevention in neighborhoods with high disease incidence or risk rates, and had the interest in and capacity for implementing new HIV prevention initiatives. The in-depth interview captured things such as characteristics of youth populations served by the agency (e.g. age, gender, sexual orientation, HIV risk behaviors, protective factors in the community); youth hang-out places; presence of community gatekeepers; access to youth at these venues; information on other HIV prevention efforts; agencies' past collaborative experiences; past experience specifically with research or university entities; agency area of expertise and future program plans. This interview was administered in person to the executive director/head of the organization or another designated individual. Because it was considered a relationship building step, the intent was to offer partnership to each organization that completed the in-depth interview process.

Partnership Formation

Based on mapping results, responses to interviews and input from key community members, C2P staff determined the likely partnership roles of each organization that was subsequently invited to participate in the collaboration as “main”, “supporting”, or “advisory” partners. Criteria for selecting main and supporting partner organizations included: knowledge of the at-risk behaviors and venues where target populations could be found; knowledge of existing or previous HIV programs in their communities; interest in implementing new HIV prevention initiatives; capacity to work with researchers on obtaining additional funding to implement and evaluate the chosen HIV prevention intervention; strengths in terms of fostering community assent, ownership, and buy in; strengths in reaching/recruiting the target population, as evidenced by mapping results and interview responses; and personnel and time to devote to C2P efforts. Main partners were meant to play the most significant role in terms of time and staff commitment, with expectations to: (1) attend all local C2P researcher-community partner meetings; (2) share information about their community and at-risk populations; (3) be directly involved in the decision-making process for choosing an intervention; and (4) eventually, aid in the recruitment of youth for interventions. Supporting partners would aid the C2P staff and main partner efforts and would be expected to attend local C2P researcher-community partner meetings when possible, share information about their community, and be involved in roles that reinforce C2P, such as raising awareness of the project, encouraging community ownership and buy in, and backing recruitment efforts. The significant difference between main and supporting partners would be the level of time commitment required and the level of involvement in anticipated recruitment activities. Advisory partners were partners who did not have the time or resources to participate at such a committed level as the main or supporting members; they would not be required to attend C2P meetings or be directly involved in the decision making process. They could be kept on a C2P mailing list, review and comment on meeting minutes and participate in C2P awareness raising events or other activities related to fostering community ownership and assent to research-based interventions.

Sites submitted to the NCC a list of organizations for which they intended to partner. The NCC reviewed these submissions and provided reflective feedback to the sites encouraging them to think strategically and outside traditional partnering landscape, keeping in mind the overall protocol objectives of building an HIV prevention intervention. Sites then officially invited organization representatives to participate. The protocol suggested that each site have 1-3 main and 3-5 supporting partners. For these partners, a “Memorandum of Understanding” (MOU) outlining roles and responsibilities was signed, designating the organization as an official partner. Organizations that completed in-depth interviews but did not meet the criteria for main or supporting partners were offered the role of advisory partner; these partners were not asked to sign an MOU. Organizations who declined to participate at the suggested level could be offered participation at an alternative level with the process continuing until the requisite numbers of main and supporting partnerships were formed.

Once the partnerships were formed, each site hosted the first official meeting for the community partners and other key constituents. The purpose of this event was to introduce official main and supporting partners and other key parties to C2P and to each other, give a formal presentation of C2P and the epidemiologic and community resource data collected, start a dialogue on HIV and youth, address partnership questions and concerns and lay out ideas and a general plan for future meetings.

Partnership Focus: Population and Geographic Area

Relevant to the partnership selection process was the identification and selection of a geographic area and population of focus, a strategy which allowed C2P to take a more targeted approach. In Phase I of C2P, staff at each site developed an epidemiological profile using Geographic Information Systems methods to “map” aggregate public health, crime and demographic data in order to reveal the highest risk areas within each urban location. Each site was also instructed to select a population of focus for subsequent interventions that appeared to be at greatest risk for HIV in their respective communities. Prospectively, it was anticipated that sites would find either young men who have sex with men or young women who have sex with men as the two top risk groups. Sites examined epidemiologic data; including local morbidity, behavioral risk, and demographic data from the mapping process; AIDS transmission category data; and information from a survey of youth conducted previously by all ATN sites addressing risk factors for HIV. Once higher-risk populations were identified, sites evaluated opportunities for accessing those groups with the assistance of community partners, via the brief surveys and in-depth interviews and other methods. Please see other literature,30-32 for more detailed descriptions of these phases of the project.

Materials

For this manuscript, a team of individuals representing different roles within the project collected and analyzed information on the partner selection phase of C2P. The Data Operations Center for the ATN was responsible for collating much of the data utilized for this paper. Additional source documents analyzed by team members included multiple memos and ongoing reports required by all sites. Finally, in order to collect additional and missing data from the primary collection, an e-mail survey designed by the manuscript team was sent to C2P staff at all 15 sites.

Results

Laying the Groundwork for Partnership

Over a several year period, in order to establish the project as a community presence and begin building relationships, site staff attended community meetings, planning groups, coalitions and events, shared local and national project information, and became familiar with both available resources and needs within the community agencies. With this information, they began to establish systems to support community agencies in their efforts. For example, they assisted agencies in applying for funding by collating and sharing grant and funding opportunities, generating data tool kits with compiled epidemiologic data and maps, and mapping additional agency data. They became brokers of resources, i.e., if an agency needed volunteers to staff a community event, C2P staff linked the agency with a pool of volunteers. Early in the project, they established listserves and newsletters to connect agencies and promote communication. Site staff compiled local data and presented it at community forums, provided training on HIV/STD or related topics, and identified and connected speakers for community events. With their varied research and public health backgrounds, site staff reviewed data, presentations and grant applications, offering themselves as resources and support; this unbridled sharing of data and resources was invaluable in establishing C2P as a committed and resourceful presence in the community.

From the Community Resource Assessment to Potential Partners

In conjunction with establishing the project's presence, and in order to determine appropriate potential partners, the site staff began a community resource assessment, in which they conducted brief surveys with 1,162 agencies across the 15 sites (average 78/site, range 30 – 109). Eight sites that focused on young women who have sex with men (YWSM) conducted brief surveys with 649 agencies, 93% (n=604) of which reported providing services specifically to young females. Of the agencies serving females, 51% (n=308) reported focusing specifically on youth, 51% (n=308) reported providing HIV/STI prevention services, and 57% (n=345) were located in the geographic area of focus. Six sites that focused on young men who have sex with men (YMSM) completed brief surveys with 438 agencies, 65% (n=286) of which reported primarily serving bi-sexual, gay and questioning youth. Of the agencies serving bi-sexual, gay, and questioning youth, 54% (n=154) reported primarily focusing on youth, 52% (n=149) reported providing HIV/STI prevention services, and 85% (n=242) were located in the geographic area of focus. Only one site focused on the intravenous drug using population (IVDU). Characteristics of the 75 agencies they interviewed included the following: 37% (n=28) reported focusing on services for youth, 48% (n=36) reported providing HIV/STI services, and 40% (n=30) were located in the geographic area of focus.

Determining Potential Partner Interest

The next integral step in partner formation was the selection of agencies for the in-depth interview; site staff only approached those agencies to whom they intended to offer some level of partnership. When considering criteria for potential partners, sites most often cited the importance of agencies to provide sexual, health promotion and/or disease prevention services to young people in or near their geographic area of focus. A congruent mission with C2P, interest in implementation of new initiatives and previous collaborative work were also mentioned as important criteria for partner consideration. Several sites mentioned the importance of inviting agencies or individuals for community buy-in and one site specifically mentioned inviting one or more partners to promote agency referrals amongst partners. A total of 335 agencies were selected from the brief survey sample, of which 281 agencies (84%, average 19/site) agreed to both the in-depth interview and to partnering. Fifty one agencies refused to or did not respond to repeated offers to participate in the in-depth interviews (see Table 1 for reasons for refusal). For reasons of incompatibility, three agencies were not invited to partner after completing the in-depth interview. Site staff provided additional insight into partner refusal in a follow-up survey explaining that while an agency may not have been able to partner and invest time and resources at this time, they often wanted to be kept informed of C2P progress. Additionally, for agencies who were repeatedly unresponsive to requests for interviews, site staff surmised that agencies felt their mission and vision were inconsistent with C2P's; that they were not health care focused, did not target the same population or did not focus specifically on prevention. Site staff also reported that unresponsiveness was often the result of staff turn-over in key personnel with whom site staff had established a relationship. Information packets and invitations to C2P meetings for those agencies who refused or were unresponsive to the interview process were often extended for future partnering possibilities.

Table 1.

Reasons for Refusal of In Depth Interview

| REASON | Number | Percent of Total Refusals |

|---|---|---|

| Staff Turnover | 8 | 16% |

| Unresponsive to Interview Request | 25 | 49% |

| Repeated Interview Cancellation by Agency | 3 | 6% |

| Funding/ Financial issues/ Other Reasons | 3 | 6% |

| Already involved in Other Partnership | 2 | 4% |

| Did not Know nor Understand C2P | 1 | 2% |

| Incomplete interview, further requests declined | 1 | 2% |

| Different Mission | 2 | 4% |

| Time Constraints | 3 | 6% |

| Declined- no reason provided | 2 | 4% |

| Agency closure | 1 | 2% |

| TOTAL | 51 |

Sites conducted 88% of the in-depth interviews in person, 28% with executive directors, and the rest with other designated staff including case managers, program directors, deputy directors or outreach coordinators. Challenges encountered in conducting the in-depth interviews included both the length of the interview (on average, approximately 90 minutes to complete) and connecting with the right person in the agency to answer the questions. Agency management turnover was also noted as a significant barrier in completion of the interview. Facilitators for completing the in-depth interview included connections in and pre-existing relationships with community agencies established and built upon during the early networking and honest brokering activities of site staff; groundwork that had been laid by sharing epidemiological data and maps; and persistence, patience and flexibility of the C2P staff.

From Partner Interest to Partner Formation: Who are the partners?

The relationship building over the early phases of the project was crucial in moving “partner interest to partnership formation.” This included attending agency meetings and serving as agency board members; supporting partner led events; and providing data/maps, presentations and technical assistance. Providing these deliverables along with the resource directory solidified C2P as a committed, established and “real” presence and partner in the community. In addition to providing assistance to the partners, several sites mentioned the value and importance of recognizing the knowledge and expertise of the partners, as utilizing and acknowledging them as resources was valuable in building the early trust and partnership.

Of the 281 organizations that agreed to partner, 42 (average 3/site) were identified as main partners, 73 (average 5/site) supporting partners, 154 (average 11/site) advisory partners and 12 partners were unidentified as to their partnership level initially. Only main and supporting partners signed MOUs. While partner level designation was an internal term, and sites did not make a significant distinction with partners about their roles, upon signing MOUs and outlining expectations with partners, 12 sites, responding in a follow-up survey reported that in general all partners approached for partnering agreed to the level of involvement and expectations of the partnerships; two sites did not respond; one site reported that one partner disagreed with their role. Where an agency was reluctant to commit at the level requested, sites noted limited resources and staffing, often asking to be kept involved or informed at a lower level. One site reported specifically that some agencies, which initially intended to play a lesser role actually became more involved. Characteristics of final partners are described in detail in tables two (partner organization type by designated partner role) and three (specific partner characteristics and types of services provided).

Discussion

The continuous erosion of public funds and the growing fissure between what is needed and what individual service organizations and health care institutions can realistically provide compel a need to form partnerships to combat complex public health problems.15 Findings from national and international collaborative efforts demonstrate that much more can be accomplished by pooling resources and sharing a common vision, goals and manpower. 19,22 Research has shown that the importance of building on local resources and strengths should not be underestimated when developing community-researcher partnerships. 33-34 Critical to this concept are the people who bring the resources to the common community table, as the combination of personalities, agency characteristics and agendas involved can either move a coalition to success or failure. 5,30

The partnership selection and formation process of the ATN's C2P community-researcher partnership provides a possible framework by which community partnerships can be developed for community mobilization and structural change in support of youth. The partner selection process, especially the in-depth interviews, aided sites in determining if potential partners had a shared vision with the project. The partner formation process allowed community relationships to develop, trust to be strengthened and a clear understanding of the role of C2P to emerge locally. Partnership studies have shown that collective actions can be strengthened by bringing together partners that share similar vision or services.30 Likewise, it is also the people who bring the resources to the common community table, along with the combination of personalities, agency dynamics and political agendas involved that can either move a coalition to success or failure.5,30 The result of this project is a diverse, solid foundation to address the common vision of reducing HIV transmission among youth.

Although this project was focused on HIV prevention, the elements outlined could be applied to other community-research partnerships developed to affect other public health outcomes. When surveyed, 87% (n=13) of the sites agreed or strongly agreed that this process is generalizable to other public health issues beyond HIV. Site staff gave additional suggestions to enhance its generalizability, including broadening the community assessment efforts beyond the epidemiologic focus and including more community input earlier on in the community assessment efforts (i.e., conducting focus groups with community members).

A unique feature of this project was the continuing oversight of a national organization and NIH funding support , implying that developing a similar collaborative without such support and funding could be a daunting task. However, when surveyed, sites reported in the affirmative that the NCC role was one of monitoring, support and guidance, not directing activities. Additionally, although the core staff for C2P were funded directly by government funding, the bulk of the project's funding was necessary for research evaluation, not programmatic purposes. The project is meant to be self-sustaining, with resources (i.e., manpower and external funding streams) coming from resources already found within the community. Thus, recreation of the programmatic portion and development of local networks could be done with creative, but much less ambitious, funding strategies developed collaboratively.

Lessons Learned

Regarding lessons learned that could be applicable to any similar collaborative, sites cautioned against focusing too much on only HIV prevention providers during HIV prevention activities and partner formation. They recommended developing an understanding of the relationship between HIV and other public health concerns (i.e. pregnancy, substance abuse) when considering partners. Utilizing national level organizations (i.e. NIDA, SAMHSA, community planning through the CDC, HRSA) as resources to assist in generating community involvement can be helpful. Similarly, public health problems do not occur in a vacuum, but represent a complex interplay of multiple issues and socially driven factors; thus programmatic responses and policies should be addressed accordingly with a multi-pronged and comprehensive approach.

Another lesson learned related to the size of the collaborative. Larger coalitions have resulted in difficulties both managing partner input and focusing on collective actions,16,17 and experts caution against them, stating that attempting synergy across diverse groups is not always effective and that much can be accomplished with smaller groups.16 The C2P process demonstrated the ability to develop synergy with greater numbers because of the structured nature of partnership selection and formation, spending time and resources selecting a smaller number of key partners with designated roles.

Additional lessons learned may be less applicable in replicating this model on a local level. Several sites commented on the timeline for the C2P project. Given the magnitude of this multi-center project, there was much variability in length of time required for each site to complete required steps, and multiple adjustments were necessary over time, with a significant “learning curve” for all involved. A more streamlined approach with earlier community involvement and strategic planning and a faster initial pace may have aided in sustaining community interest at some sites - certainly achievable if this process were replicated on a smaller scale at a local level. Despite the structured approach, sites complained of a lack of clarity of purpose at the outset which may have affected the partnership process, for example in making alternate partner choices; again, easily achieved at a local level.

As the health of the partnership and sense of true collaboration from all partners are vital to the success of such a partnership, ongoing and future research includes qualitative assessments of community- researcher partner relationships35,36 and continued monitoring of coalition building and community mobilizing activities by an external program evaluation team. Additionally, surveillance of health outcomes of community youth are planned to determine program impact.

Summary and Importance

Community–researcher partnerships can play a central role in the process of community transformation.2,5,19 In identifying and utilizing community resources and selecting partners that will be agents of social change, a collaborating process is established and a culture of teamwork is created. 30,36 C2P's approach to partner selection and formation allowed sites to determine if potential partners shared a common vision, strengthened community relationships and built trust and permitted a clear understanding of the role of C2P to emerge locally. The direct and systematic process described in this paper provides a framework by which community-researcher partnerships can be developed for community mobilization and structural change in support of youth.

Table 2.

Partner Organization Type by Designated Partnership Role

| Partner Level | Main Number/Percent | Supporting Number/Percent | Advisory Number/Percent | Total Number/Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partner Organization Type1 | ||||

| Community-Based Organization | 37/88% | 46/63% | 99/60% | 182/67.6% |

| Medical Health Care | 9/21.4% | 19/26% | 30/19.4% | 58/21.6% |

| Mental Health Care | 7/16.6% | 14/19.1% | 19/12.3% | 40/14.8% |

| Local Government Agency | 3/7.1% | 9/12.3% | 25/15.2% | 37/13.7% |

| Faith-based/Spiritual | 2/4.7% | 7/9.5% | 15/9.7% | 24/8.9% |

| Cultural/Social Institution | 2/4.7% | 6/8.2% | 13/8.4% | 21/7.8% |

| Coalition | 5/11.9% | 4/5.4% | 4/2.5% | 13/4.8% |

| Planning Council | 2/4.7% | 3/4.1% | 3/1.9% | 8/2.9% |

| Youth Community Advisory Board | 1/2.3% | 1/1.3% | 3/1.9% | 5/1.8% |

| Missing | 1/2.3% | 0/0 | 1/0.6% | 2/0.7% |

| Other2 | 6/14.2% | 13/17.8% | 26/15.8% | 45/16.7% |

| Total | 75 | 122 | 238 | 435 |

| Partner Level Type Total | 42/15.6% | 73/27.1% | 154/57.2% | 2693 |

| Located in Geographic Area Of Focus | 28/18.3% | 39/26.8% | 86/56.2% | 153/58.7% |

Note that “partner organization type” was a multi-factorial question and organizations could describe themselves as fitting into more than one category.

“Other” signified non “traditional” partners and included boards of education, after-school programs, substance abuse facilities, local bar/club owner, mobile van, local and federal law enforcement and public defenders offices and a funeral home.

Note that total number of partners here equals 269, less than the total number of partners noted in the text (281) due to the 12 partners initially unidentified as to designated partnership role

Table 3.

Final Partner Characteristics

| PARTNER CHARACTERISTICS1 | SERVICE PROVISION2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | # Partners Per Site | Population3 Of Focus | Power Broker | Interest/New HIV Initiative | Foster Collaboration | Community Presence | C2P Buy-In | Research Interest | GAF | TP | YF | HIVF |

| 1 | 19 | YWSM | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 19 | 7 | 7 |

| 2 | 16 | YMSM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 16 | 4 | 8 |

| 3 | 13 | YWSM | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| 4 | 19 | YMSM | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 18 | 19 | 3 | 15 |

| 5 | 21 | YWSM | 1 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 18 | 7 | 11 |

| 6 | 19 | IVDU | 4 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 19 | 10 | 12 | 12 |

| 7 | 21 | YWSM | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 21 | 9 | 3 |

| 8 | 23 | YMSM | 2 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 20 | 21 | 5 |

| 9 | 12 | YMSM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 7 | 4 |

| 10 | 20 | YWSM | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 9 | 4 |

| 11 | 17 | YMSM | 0 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 16 | 17 | 11 | 3 |

| 12 | 20 | YWSM | 3 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 19 | 11 | 11 |

| 13 | 20 | YWSM | 3 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 20 | 15 | 7 |

| 14 | 20 | YWSM | 3 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 19 | 16 | 7 |

| 15 | 21 | YMSM | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 18 | 14 | 4 |

| Total | 281 | 30 | 52 | 66 | 67 | 56 | 39 | 65 | 258 | 152 | 107 | |

| % of total partners* | 11% | 19% | 23% | 24% | 20% | 14% | 59% | 92% | 54% | 38% | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Average #/site with identified characteristic: | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total | 19/site | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 18 | 10 | 7 | |

Characteristics = partner was considered a “power broker”, expressed particular interest in new HIV initiatives, would foster collaboration, had significant community presence, had significant C2P “buy-in”, and/or was interested in research collaboration.

Service = GAF: Serves Geographical Area of Focus, PF: Serves Population of Focus; YF: Youth Focused; HIVF: HIV Focused

Population of Focus = YWSM: Young Women Who Have Sex with Men; YMSM: Young Men Who Have Sex with Men; IVDU: Intravenous Drug Users

Questions on characteristics were not mutually exclusive and partners could use more than one characteristic to describe themselves. Thus, total percents add up to more than 100%.

Acknowledgments

The following ATN sites participated in this study: University of South Florida: Patricia Emmanuel, MD, Diane Straub, MD, Shannon Cho, BS, Georgette King, MPA, Mellita Mills, BS, and Chodaesessie Morgan, MPH. Childrens Hospital of Los Angeles: Marvin Belzer, MD, Miguel Martinez, MSW/MPH, Veronica Montenegro, Ana Quiran, Angele Santiago, Gabriela Segura, BA, and George Weiss, BA. Children's Hospital National Medical Center: Lawrence D'Angelo, MD, William Barnes, PhD, Bendu Cooper, MPH, and Cassandra McFerson, BA. The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: Bret Rudy, MD, Antonio Cardoso, BBA and Marne Castillo, M.Ed. John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital and the CORE Center: Lisa Henry-Reid, MD, Jaime Martinez, MD, Zephyr Beason, MSW, and Draco Forte, MEd University of Puerto Rico: Irma Febo, MD, Ileana Blasini, MD, Ibrahim Ramos-Pomales, MPHE, and Carmen Rivera-Torres, MPH. Montefiore Medical Center: Donna Futterman, MD, Sharon S. Kim, MPH, Lissette Marrero, Stephen Stafford, and Carol Tobkes, MPH. Mount Sinai Medical Center: Linda Levin, MD, Meg Jones, MPH, Christopher Moore, MPH and Kelly Sykes, PhD. University of California at San Francisco: Barbara Moscicki, MD, Coco Auerswald, MD, Catherine Geanuracos, MSW, Kevin Sniecinski, BS. Tulane University Health Sciences Center: Sue Ellen Abdalian, MD, Lisa Doyle, Trimika Fernandez, MS, and Sybil Schroeder, PhD. University of Maryland: Ligia Peralta, MD, Bethany Griffin Deeds, MA, PhD, Sandra Hipszer, MPH, Maria Metcalf, MPH, and Kalima Young, BA. University of Miami School of Medicine: Lawrence Friedman, MD, Angie Lee, Kenia Sanchez, MSW, Benjamin Quiles, BSW and Shirleta Reid. Children's Diagnostic and Treatment Center: Ana Puga, MD, Dianne Batchelder, RN, Jamie Blood, MSW, Pam Ford, MS, and Jessica Roy, MSW. Children's Hospital Boston: Cathryn Samples, MD, Wanda Allen, Lisa Heughan, BA, and Judith Palmer-Castor, MA, PhD. University of California at San Diego: Stephen Spector, MD, Rolando Viani, MD, Stephanie Lehman, PhD, and Mauricio Perez.

The authors would also like to acknowledge Connect to Protect's National Coordinating Center at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and DePaul University's Quality Assurance Team including staff members and consultants Nancy Willard, B.A., Suzanne Maman, PhD, Marizaida Sánchez-Cesáreo, PhD, Shayna Cunningham, MHS, Matthew Bowdy, MA, Rachel Lynch, MPH, Audrey Bangi, PhD, Mimi Doll, PhD, Jason Johnson, BA, Danish Meherally, BS, Grisel Robles, BA, and Leah Neubauer, BA. We would also like to thank the ATN Data and Operations Center (Westat, Inc.) including Jim Korelitz, Barbara Driver, Lori Perez, Rick Mitchell, Stephanie Sierkierka, and Dina Monte, and individuals from the ATN Coordinating Center at the University of Alabama at Birmingham including Craig Wilson, MD, Cindy Partlow, MEd, Marcia Berck and Pam Gore.

Finally, a special thanks to all the youth who have participated in our national and local youth community advisory boards for their thoughtful contributions to the work of this project and to the staff at local community based organizations, public health departments, police departments, state agencies, and other institutions or agencies who provided data and gave generously of their time.

Funding support: The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) and Connect to Protect are funded by grant Nos. U01 HD40506-01 and U01 HD40533 from the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Audrey Smith Rogers, Robert Nugent, Leslie Serchuck), with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (Nicolette Borek), Mental Health (Andrew Forsyth, Pim Brouwers), and Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Kendall Bryant).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brown P, Garg S. Foundations and comprehensive community initiatives: the challenges of partnership. Chicago, Ill: Chapin Hall Center for Children, University of Chicago Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edwards SL, Stern RF. Building and sustaining community partnerships for teen pregnancy prevention: A working paper. Cornerstone Consulting Group, Inc; 1998. [accessed March 31, 2005]. Available at: http://aspe.hhs/gov/hsp/teenp/teenpreg/teenpreg.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fawcett SB, Paine AL, Francisco VT, Vliet M. Promoting health through community development. In: Glenwick DS, Jason LA, editors. Promoting health and mental health in children, youth, and families. Vol. 27. 1993. pp. 233–255. (Springer series on Behavior Therapy and Behavioral Medicine). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butterfoss FD, Goodman RM, Wandersman A. Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion: factors predicting satisfaction, participation, and planning. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(1):65–79. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israel BA, Schultz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. An Rev of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francisco VT, Fawcett SB, et al. Toward a research-based typology of health and human service coalitions. Amherst, MA: AHEC/Community Partners; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liontos LB. ERIC Digest Series, Number EA 48. ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management; Eugene, OR: 1990. [accessed May 06, 2005]. Collaboration between schools and social services. [SJJ69850] Available at: http://gateway.ut.ovid.com/gw1/ovidweb.cgi. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paine-Andrews A, Harris KJ, Fisher JL, Lewis RK, Williams EL, Fawcett SB, Vincent ML. Effects of a replication of a school/community model for preventing adolescent pregnancy in three Kansas communities. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;31(4):182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paine-Andrews A, Fisher JL, Harris KJ, Lewis RK, Williams EL, Vincent M, Fawcett SB, Campuzano MK. Some experiential lessons in supporting and evaluating community-based initiatives for preventing adolescent pregnancy. Health Promotion Practice. 2000;1(1):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sege RD. The multisite violence prevention project: a commentary from academic research. Am J of Preventive Medicine. 2004;26(l1):78–79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterfoss FD, Kelly C, Taylor-Fishwick J. Health planning that magnifies the community's voice: allies against asthma. Health Education Behavior. 2005;32(1):113–28. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butterfoss FD, Webster JD, Morrow AL, Rosenthal J. Immunization coalitions that work: training for public health professionals. J of Public Health Management Practice. 1998;4(6):79–87. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kegler M, Twiss JM, Look V. Assessing community change at multiple levels: the genesis of an evaluation framework for the california healthy cities project. Health Education Behavior. 2000;27(6):760–79. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff T. Community coalition building – contemporary practice and research: introduction. Am J of Community Psychology. 2001;29(2):165–172. doi: 10.1023/A:1010314326787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavery SH, Smith ML, Esparza AA, Hrushow A, Moore M, Reed DF. The community action model: a community-driven model designed to address disparities in health. Am J of Public Health. 2005;95(4):611–618. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubisch AC, Weiss CH, Shorr LB, Connell JP. Introduction in New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives, Concepts, Methods and Concepts. New York: Aspen Institute – Roundtable on Comprehensive Community Initiatives For Children and Families; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaskin RJ, Brown P, Venkatesh S, Vidal A. Building Community Capacity. New York: Aldine De Gruyter Press; 2000. Collaborations, Partnerships and Organizational Networks. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knox C. [accessed March31, 2005];Northern Ireland executive briefing paper: partnership. 2002 Available at: http://www.rpani.gov.uk/partnerships/index.htm.

- 19.Roussos S, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. An Rev of Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantz PM, Viruell-Fuentes E, Israel BA, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. J of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blumenthal DS, Yancey E. Community based research: An introduction in community based health research, issues and methods. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker E, Homan S, Schonhoff R, Kreuter M. Principles of practice for academic practice community research partnerships. Am J of Preventive Medicine. 1999;16(35):86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heffner GG, Zandee GL, Schwander L. Listening to community voices: community-based research, a first step in partnership and outreach. J of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement. 2003;8(1):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland BA, Gelmon S, Green L, Greene-Morton E, Stanton T. Community-university partnerships: What do we know? San Diego, CA: 2003. Prepared for discussion at a national symposium jointly sponsored by community-campus partnerships for health and HUD's office of university partnerships. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chavis DM. Building community capacity to prevent violence through coalitions and partnerships. J of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1995;6(2):234–245. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattesich PW, Murray-Close M, Monsey BR. Collaboration: what makes it work. 2. Appen A. St Paul MI: Amherst Wilder Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff T. A practitioner's guide to successful coalitions. Am J of Community Psychology. 2001;29(2):173–191. doi: 10.1023/A:1010366310857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster-Fishman P, Berkowitz S, Lounsbury DW, Jacobson S, Allen NA. Building collaborative capacity in community coalitions: a review and integrative framework. Am J of Community Psychology. 2001;29(2):241–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1010378613583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasker RD, Weiss ES, Miller R. Partnership Synergy: A Practical Framework for Studying and Strengthening the Collaborative Advantage. The Millbank Quarterly. 2001;79(2):179–205. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziff M, Harper G, Chutuape K, Deeds BG, Futterman D, Ellen J. for the Adolescent Trial Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Laying the foundation for Connect to Protect®: A multi-site community mobilization intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS incidence and prevalence among urban youth. J of Urban Health. 2006;83(3):506–522. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geanuracos C, Cunningham SD, Weiss G, Forte D, Henry Reid LM, Ellen JM. Using Geographic Information Systems for HIV Prevention Intervention Planning for High-Risk Youth. 2006. for the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Intervention. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deeds BG, Straub DM, Willard N, Castor J, Ellen J, Peralta L, Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions . Journal of Adolescent Health. Vol. 38. Society of Adolescent Medicine; Boston, MA: Mar 22-25, 2006. 2006. Fertile ground: The role of a community asset assessment in 15 community-researcher partnerships promoting adolescent health; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Introduction to community empowerment participatory education, and health. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):141–148. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruossos S, Fawcett SB, Francisco VT, Berkley JY, Lopez CM. A behavioral analysis of collaborative partnerships for community health. In: Lamal PA, editor. Cultural Contingencies: Behavior Analytic Perspectives on Cultural Practices. Greenwich, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harper GW, Bangi A, Contreras R, et al. Diverse phases of collaboration: working together in improve Community-Based HIV Interventions for Adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(34):193–204. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027005.03280.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harper GW, Salina DD. Building collaborative partnerships to improve community-based HIV prevention research: The university collaborative partnership (UCCP) model. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2000;19(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]