Abstract

Large-scale proteomic analysis of the mammalian brain has been successfully performed with mass spectrometry techniques, such as Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT), to identify hundreds to thousands of proteins. Strategies to efficiently quantify protein expression levels in the brain in a large-scale fashion, however, are lacking. Here, we demonstrate a novel quantification strategy for brain proteomics called SILAM (Stable Isotope Labeling in Mammals). We utilized a 15N metabolically labeled rat brain as an internal standard to perform quantitative MudPIT analysis on the synaptosomal fraction of the cerebellum during post-natal development. We quantified the protein expression level of 1138 proteins in four developmental time points, and 196 protein alterations were determined to be statistically significant. Over 50% of the developmental changes observed have been previously reported using other protein quantification techniques, and we also identified proteins as potential novel regulators of neurodevelopment. We report the first large-scale proteomic analysis of synaptic development in the cerebellum, and we demonstrate a useful quantitative strategy for studying animal models of neurological disease.

In the last decade, liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC/LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a high-throughput analysis tool for “shotgun” protein identification. One common LC/LC-MS/MS technique is Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT) (Washburn et al. 2001). In a typical MudPIT experiment, a protein sample is digested with proteases to create a complex mixture of peptides, separated by multidimensional chromatography, and the peptides are eluted directly into a tandem mass spectrometer, where tandem mass spectra are generated for each peptide. Computer algorithms, such as SEQUEST, are then used to extract the amino acid sequence from the spectra and determine the identity of the proteins in the sample (Eng et al. 1994). MudPIT experiments can identify hundreds to thousands of proteins from a single biological sample. The fractionation of cellular components (e.g., organelles) before MudPIT analysis can provide additional information on protein localization (Yates et al. 2005). Since protein expression and localization are dynamic, quantification using mass spectrometry data has recently been under intense development.

One means of quantifying MS data is by comparing an unlabeled or “light” peptide (composed of naturally abundant stable isotopes) to a chemically identical peptide with the exception that the atoms are enriched with a stable “heavy” isotope (e.g., 13C or 15N) (Oda et al. 1999; Conrads et al. 2001). An abundance ratio between the labeled and unlabeled peptides can then be calculated from the respective ion chromatograms (MacCoss et al. 2003; Gruhler et al. 2005; Everley et al. 2006; Pan et al. 2006). Metabolic labeling is commonly employed to enrich a protein sample with stable isotopes (Goodlett et al. 2001; Hunter et al. 2001; Ong et al. 2002; Washburn et al. 2002; Zhu et al. 2002), and then, alterations in protein expression induced by a stimulus can be determined by analyzing two samples utilizing the same labeled internal standard. For example, to analyze the yeast proteome in response to osmotic shock, a mixture of unlabeled yeast mixed 1:1 with 15N-labeled yeast is digested and analyzed by MudPIT, and the ratio between unlabeled and labeled proteins is calculated. A second sample is then analyzed consisting of unlabeled yeast that has undergone osmotic shock mixed with the same 15N-labeled yeast analyzed in the first sample. Thus, the 15N peptides are used as internal standards, and the difference in the 14N/15N ratios between the two experiments reveals protein expression altered by osmotic shock (MacCoss et al. 2003). Besides yeast, metabolic labeling of cultured mammalian cells using one or two stable isotope-labeled amino acids strategy is commonly employed to generate high-throughput quantitative data (Zhu et al. 2002; Blagoev et al. 2003). Multicellular organisms, such as Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, have also been metabolically labeled with stable isotopes (Krijgsveld et al. 2003). Thus, employing metabolic labeling for quantitative mass spectrometry has been successful in many different biological systems and has the advantage of using the synthetic machinery of the cell to insert labels into proteins.

The complexity of the mammalian brain, however, still presents a technical and biological challenge to mass spectrometry. The brain consists of many distinct functional regions, each of which consists of different cell types. The structural and functional connections between these regions exacerbate the complexity of the biology. For example, the cell body and axon terminal of the same neuron are often located in two different functional regions. Although some laboratories have demonstrated MudPIT as an efficient platform for high-throughput protein identification of the brain proteome (Wu et al. 2003; Phillips et al. 2004; Cagney et al. 2005; Schrimpf et al. 2005; Witzmann et al. 2005), a large-scale quantitative methodology is lacking for analysis of the brain proteome. For example, using the AQUA (absolute protein identification) strategy, the differential expression of 32 proteins between brain regions has been reported (Peng et al. 2004; Cheng et al. 2006). In this method, known amounts of labeled peptides are mixed with a complex protein sample, and by comparison to the labeled peptides, the protein expression is calculated. Since the labeled peptides are made individually, the number of proteins that can be quantified is limited. Alternatively, peptides from brain tissue have been labeled in vitro with isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT), isotopic labeling with a beta-elimination/Michael addition-based (BEMAD) approach, or amine-specific isobaric tags (iTRAQ) to calculate biological differences between brain samples (Hansen et al. 2003; Haqqani et al. 2005; Jin et al. 2005; Prokai et al. 2005; Vosseller et al. 2005; Hu et al. 2006). In these in vitro labeling strategies, the labeled and unlabeled samples are fractionated separately, which allows for the accumulation of systematic errors. In addition, some of these strategies only label peptides with a specific functional group, which means only a subset of the sample is quantifiable. Ishihama et al. (2005) took a creative approach by using a metabolically labeled 15N Neuro2A mouse cell line as an internal standard for mouse brain. One drawback to this strategy is that the Neuro2A and brain proteome do not completely overlap. For example, neurons in vivo form synapses, while Neuro2A-cultured cells do not. Therefore, Neuro2A cells are a suboptimal internal standard to quantify all brain proteins.

To develop a quantitative MS method for brain tissue, we developed SILAM (stable isotope labeling of mammals), a method to metabolically label an entire rat by feeding it a specialized diet consisting of 15N (Wu et al. 2004). We recently reported an improved SILAM method to achieve 94% labeling in rat brains (McClatchy et al. 2007). We now report a proteomic approach using metabolically labeled rats and MudPIT to detect biological changes within synapses of the cerebellum during post-natal development. The synaptic proteome of the cerebellum is a complex dynamic structure with many known changes in protein expression during post-natal development. For example, there is a well-documented burst in synaptogenesis during post-natal development (Erecinska et al. 2004). We quantified the expression of proteins in the synapse at four different time points using 15N-labeled brain tissue as an internal standard. Statistical analysis of the MS data determined significant differences during post-natal development, and Western blot analysis and previous reports verified the accuracy of our data. Overall, this study demonstrates the use of SILAM as a novel strategy to quantitatively study animal models of neurological disease in a large-scale fashion.

Results

Protein identification

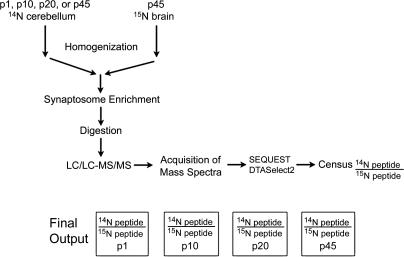

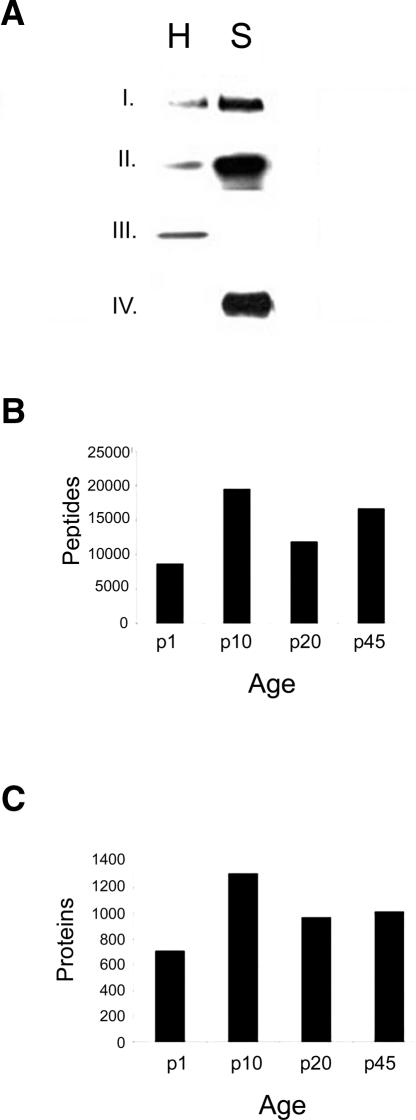

A summary of the quantitative experiment is shown in Figure 1. We dissected the cerebellum from Sprague-Dawley rats at four different developmental time points: post-natal day 1 (p1), p10, p20, and p45. The cerebella were subjected to homogenization, upon which synapses form closed vesicles termed synaptosomes (Whittaker et al. 1964). After each cerebellar homogenate was mixed with an equal amount of total brain homogenate from a p45 15N-labeled rat, synaptosomes from each mixture were isolated via a sucrose gradient. The enrichment of synaptosomes was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A). The synaptosomal fraction was digested, and each digestion was analyzed three times by MudPIT. The peptides were identified from the mass spectra by SEQUEST, and at least two peptides were required for valid protein identification. In all experiments, 56,684 peptides and 4001 proteins were identified (Fig. 2B,C).

Figure 1.

Experimental outline. Cerebella were dissected and homogenized from unlabeled (14N) rats at p1, p10, p20, or p45. Homogenates were then mixed in a 1:1 ratio with total brain homogenate from a 15N p45 rat. The synaptosomal fraction was isolated from each mixture, and then this fraction was digested with proteinase K. One hundred micrograms from each developmental period was analyzed three times by MudPIT for a total of 300 μg for each developmental period. From the mass spectra, proteins were identified by SEQUEST, and the 14N/15N ratio for each identified peptide was calculated by Census. The peptide ratios for each protein were compared between the developmental periods.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis and protein identification of the synaptosomal fraction. (A) To verify the enrichment of the synaptosomes, we performed Western blot analysis with known synaptic markers. We observed a dramatic increase in the immunoreactivity of synapsin-1 (I, presynaptic marker) and PSD-95 (II, postsynaptic marker) in the synaptosomal fraction (S) compared with unfractionated homogenate (H). In addition, we also observe an increase in the immunoreactivity of cytochrome c oxidase (IV, mitochondria marker) in the synaptosomal fraction consistent with the synaptic localization of mitochondria. We, however, observed more immunoreactivity of H3 histone (III) in the homogenate consistent with its localization in the nucleus and not in the synapses. In this study, we identified 4001 proteins (C) and 56,684 peptides (B).

Protein quantification

Next, we quantified the peptides using Census, which is an algorithm that converts mass spectrometry–derived data of peptides into relative protein abundances. Essentially, the program uses a linear least-squares correlation to calculate the peptide intensity ratio for each 14N and 15N pair (Fig. 3A). In addition, Census generates a correlation number between the labeled and unlabeled chromatograms, which indicates the quality of the quantitative measurement. After filtering, 18,359 peptides comprising 1138 proteins were quantified by high-quality ion chromatograms. Seventy-four percent of these proteins were quantified with two or more peptides (Fig. 3B). We performed ANOVA analysis on the proteins quantified in at least three time points to determine any statistical differences in expression (Fig. 3C). We observed 196 proteins having a significant difference (P value < 0.05) in expression during post-natal development. We performed an additional statistical test on these proteins to determine if there was a linear trend of protein expression. Out of the identified proteins with annotated genes, we observed that the expression of 105 proteins had a positive slope, while 19 had a negative slope (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Quantitation of the synaptosomal proteome. (A) The Census graphical output for the peptide, MRAPPGAPEKQPAPGDAYGDA, from synaptophysin. The peptide elution peak is highlighted in yellow, and red line represents the 15N-labeled peptide, while the blue line represents 14N peptide. The Y-axis is relative intensity, and the X-axis is time. In the p1 sample, the 14N peptide is less intense than the 15N peptide, but the same peptide in the p45 sample is more intense than the 15N peptide. Census calculated the 14N/15N ratios as 0.27(p1) and 1.2(p45) consistent with the well-documented increase in synaptophysin during post-natal development. (B) Organizing the results as the number of quantified peptides per protein demonstrates 74% of the proteins were quantified with two or more peptides. In C, the X-axis represents the number of developmental periods in which a protein was quantified. (D) We performed ANOVA analysis on proteins that were quantified in at least three developmental periods, which was 298 proteins. One hundred ninety-six proteins were determined to have a statistical significant change in expression during development, and 141 of these proteins have annotated genes. We further analyzed these 141 proteins with an additional statistical test to determine if there is a statistically significant (P < 0.05) linear change of protein expression. We observed 105 proteins with positive slope and 19 proteins with a negative slope during development.

Validation of quantitative data

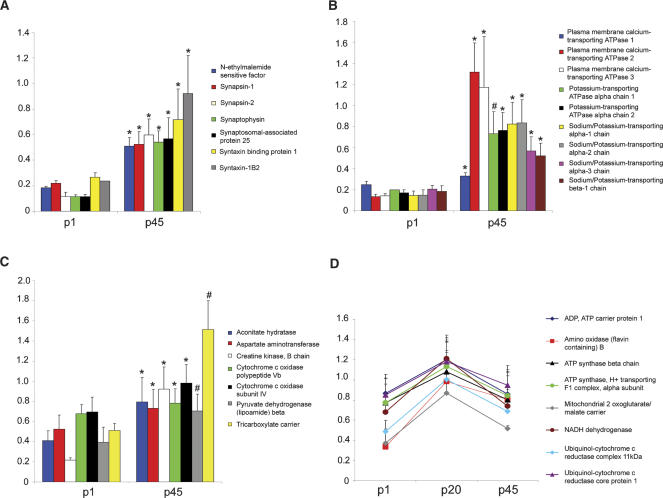

To verify our quantification was accurate, we performed an extensive literature search for protein changes during post-natal brain development to determine if our data corresponded to reports on protein expression via other protein quantification methods (Fig. 3D; Supplemental Table 1). Two major changes during post-natal development involve synapses and energy utilization. During the post-natal development, there is a burst in synaptogenesis (Erecinska et al. 2004). Consistent with this increase in synaptic density, we observed an increased expression from p1 to p45 of resident presynaptic proteins essential for neurotransmitter release (Fig. 4A). Following a similar time course as synaptogenesis, neurons exhibit changes in membrane potential during post-natal development (Crepel 1972). Membrane potential is generated by a precise distribution of ions (Na+, K+, and Ca2+) across the membrane. Enzymes utilizing ATP, ATPases, are required to move ions against their gradients across the membrane to maintain and regulate membrane potential at the synapses, which is essential for neurotransmitter release (McMahon and Nicholls 1991; Nicholls 1993). We observed a variety of ATPases that increased during the experimental time course (Fig. 4B). The mammalian brain has been described as a steady-state system where ATP production equals ATP utilization (Erecinska et al. 2004). Consistent with this theory, we observed the expression of proteins of the mitochondria, which generates 90% of cellular ATP, increasing linearly during post-natal development (Fig. 4C). The expression of mitochondrial proteins in this study also demonstrated another distinct developmental pattern, where peak expression was measured at p20 and then dropped dramatically at p45 (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Altered expression of different classes of proteins during post-natal development. The expression of proteins essential for neurotransmission (A) and ATPases (B) significantly increased from p1 to p45. The expression of mitochondrial proteins exhibited two distinct trends in expression during post-natal development. The expression of some mitochondrial proteins significantly increased from p1 to p45 (C), while the expression of other mitochondrial proteins significantly increased from p1 to p20 but then the expression decreased dramatically (D). After the change in protein expression was determined significant in an ANOVA analysis, a Bonferroni post-hoc test was performed. The significant difference in 14N/15N ratios between p1 and p45 for the Bonferroni post-hoc test are represented for A, B, and C by * (P-value < 0.001) and # (P-value < 0.01). The significant difference in 14N/15N ratios between p1 and p20 for the Bonferroni post-hoc test in D are as follows: ADP, ATP carrier protein 1, ATP synthase beta chain, ATP synthase, H+ transporting, mitochondrial F1 complex, alpha subunit, isoform 1, NADH dehydrogenase, and Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein I had P-values < 0.001, and Amine oxidase [flavin-containing] B, Mitochondrial 2-oxoglutarate/malate carrier protein, and Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase complex 11-kDa protein had P-values < 0.05. There was no significant difference detected for any of the proteins between the 14N/15N ratios between p1 and p45 in D. The Y-axis represents 14N/15N ratio.

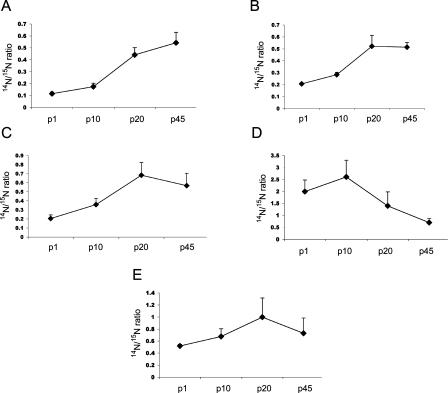

The time courses of expression that were observed during development also corresponded to previous reports. For example, the expression of synaptophysin, a presynaptic protein, has been previously reported to increase dramatically up to p20 and then gradually plateau into adulthood in the cerebellum (Wright et al. 1991). Our quantitative mass spectrometry data show a similar trend (Fig. 5A). Consistent with antibody expression data on the glutamate receptor 2 protein (GluR2) in the cerebellum (Hafidi and Hillman 1997), we observed GluR2 expression at birth, and it peaked at p20, which is then maintained into adulthood (Fig. 5B). Electrophysiological studies have demonstrated that between p10 and p20, there is a significant increase in the resting potential of neurons, and this is the result of an increase in resting Na+/K+ pumping. Although Na+/K+ ATPase can be acutely activated by phosphorylation, it has been demonstrated that this electrophysiological phenomenon is due to an increase in the expression of this enzyme (Molnar et al. 1999), consistent with our data (Fig. 5C). We also observed different developmental patterns between the two homologous proteins of the elongation 1A (eEF1A) family. eEF1A1 and eEF1A2 share 92% amino acid homology but have distinct developmental expression profiles in the brain. Consistent with measurements performed with isoform-specific antibodies (Khalyfa et al. 2001), eEF1A1 is down-regulated, while eEF1A2 is up-regulated during post-natal brain development (Fig. 5D,E).

Figure 5.

Time course of protein expression during post-natal development. We identified significant linear trends of synaptic proteins during four developmental time points. (A) synaptophysin (P < 0.0001, P-value of linear trend post-hoc test), (B) GluR2 (P < 0.0001), (C) Na+/K+ ATPase alpha-1 (P < 0.0001), (D) eEF1A1 (P < 0.0001), and (E) eEF1A2 (P < 0.0007).

We also compared our results with quantitative Western blot analysis (Fig. 6). Our MS data were generated from one synaptosomal preparation for each developmental time point, but there can be variability between different synaptosomal preparations. To address this issue, we performed Western blot analysis on six separate synaptosomal preparations (three from p1 and three from p45), each consisting of three different cerebella. Statistically significant changes in the protein expression level between p1 and p45 were observed and were in agreement with the SILAM analysis (Fig. 6). For example, the expression of GluR2 was observed to be significantly increased during post-natal development in both SILAM and Western blot analysis, while alpha-tubulin expression was observed to be decreased during post-natal development in both analyses. In addition, no significant change was observed for the expression of cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 between p1 and p45 in either analysis. All of the proteins analyzed were consistent with the SILAM analysis, but the magnitude of the change in protein expression appeared to be underestimated in the SILAM analysis. This underestimation of differences between 14N/15N peptide abundance ratios by the LTQ linear ion trap (IT) mass spectrometer that was employed in this study has been previously observed (Venable et al. 2004). It is possible that the observed change in protein expression may not actually be a change in protein expression, but a change in localization. For example, a protein may have the same expression level at p1 and p45, but the protein may not fractionate into the synaptosomal fraction at p1, resulting in an observed decrease of the protein at p1. To address this issue, we also performed quantitative Western blot analysis of total cerebellar homogenate. We observed a significant change of immunoreactivity in the total cerebellar homogenate between p1 and p45, similar to the change observed with the synaptosomal fraction. This suggests these observed changes represent differential expression not localization.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Western blot and mass spectrometry analysis. We probed the synaptosomal fraction with different antibodies to confirm our quantitative mass spectrometry results. Immunoblot analysis was performed twice on three different synaptosomal fractions from p1 and p45, and the intensity of the immunoreactivity was measured. A representative immunoblot is shown for each antibody tested, and a bar graph with the immunoreactivity measurements from the synaptosomal preparations (black). N = 6 for each development period for each antibody. The Y-axis represents mean pixel intensity. Proteins that demonstrated a significant change in immunoreactivity in the synaptosomal fraction were also tested to determine if the significant change was also presented in total cerebellar homogenate (white). Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed t-test. The following antibodies were employed: (A) Glutamate receptor subunit 2/3, (B) Na+/K+ ATPase alpha-1 chain, (C) alpha-tubulin, (D) cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1. Next to the immunoblot is the SILAM analysis of the same protein. The white bars represent the p1 sample, and the black bars represent the p45 sample. The Y-axis represents the 14N/15N ratio. The SILAM data were determined to be significantly altered (P < 0.05) during post-natal development by one-way ANOVA analysis followed by a Bonferroni post-hoc test to determine the significant difference of the protein expression between p1 and p45. The SILAM bar graph for alpha-tubulin represents the average mass spectrometry data for four proteins: tubulin alpha-1, tubulin alpha-2, tubulin alpha-3, and tubulin alpha-8. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.001.

Discussion

LC/LC-MS/MS strategies have been proven to be invaluable in elucidating the proteomes of many different organisms. Recent reports have demonstrated successful strategies for quantifying these proteomes, but these strategies are inapplicable or less efficient for the complexity of brain tissue. We demonstrate, here, the usefulness of SILAM to quantify the brain proteome. We chose to examine the rat cerebellum during post-natal development because of known dramatic changes of electrophysiological and structural characteristics (Altman and Bayer 1997). Although this is the first large-scale analysis of the cerebellum during post-natal development, there are many reports of changes of individual cerebellar proteins during development using other quantification methods to confirm our data. Overall, we identified 196 proteins whose expression was significantly altered during post-natal development. Of the annotated proteins in our data set, >50% of the protein expression changes were already described in the literature.

There are relatively few large scale published analyses for quantifying brain tissue that do not employ two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE). Although 2-DE followed by mass spectrometry analysis is able to identify proteins, it is ineffective in detecting proteins of low abundance, extreme pI, high molecular weight, or high hydrophobicity (Choudhary and Grant 2004). Many of the recent gel-free approaches employ in vitro labeling of peptides. For example, a recent study quantifying the differences of plasma membrane proteins between different brain regions using the HysTag reagent quantified 555 proteins (Olsen et al. 2007). Since the HysTag reagent targets only cysteine-containing peptides, the quantification of more than 70% of the proteins relied on one peptide (Olsen et al. 2007). Alternatively, Hu et al. (2006) used the iTRAQ reagent to quantify changes in the cerebellum of a plasma membrane calcium ATPase 2 knockout mouse and quantified 953 proteins. Unlike HysTag, the iTRAQ reagent binds primary amine groups and has the potential to bind all peptides unless both lysine and a reactive N-terminal group are lacking from a peptide. Although the number of proteins quantified is similar, our study quantified a far greater number of peptides. Hu et al. (2006) quantified 953 proteins from 5457 peptides, while we quantified 1138 proteins from 18,365 peptides. This iTRAQ study employed matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) coupled with a time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer, while we employed electrospray ionization (ESI) coupled with an IT mass spectrometer. It has been documented that an ESI-IT results in greater protein sequence coverage compared to a MALDI-TOF (Lim et al. 2003). The iTRAQ quantification is not applicable to IT instruments due to their inefficiency in detecting the low-mass iTRAQ reagent fragments, but it has been recently reported that pulsed-Q dissociation (PQD) aids in the detection of these low mass fragments in IT mass spectrometers(Meany et al. 2007). In addition, the labeled and unlabeled samples are fractionated separately in these in vitro labeling strategies, while the labeled and unlabeled samples were mixed before fractionation using SILAM. Mixing the labeled and unlabeled samples at the earliest point in the sample preparation helps to eliminate the accumulation of systematic errors. Thus, SILAM combined with an ESI-IT mass spectrometer quantifies a greater number of peptides from brain tissue compared to previous reports using in vitro labeling strategies.

Although previous studies have used the entire brain for LC/LC-MS/MS methodology development, protein expression in individual brain regions is distinctively regulated in development and disease (Mattson et al. 1999; Erecinska et al. 2004). For example, spinocerebellar ataxias are a group of neurodegenerative disorders primarily involving cerebellar dysfunction (Duenas et al. 2006), while Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by specific neurodegeneration of the basal ganglia (Vernier et al. 2004). To investigate changes in protein expression between regions using the same internal standard in future studies, 15N total brain homogenate was employed as an internal standard in this study instead of just the 15N cerebellar homogenate. Consistent with using total 15N-labeled brain as an internal standard, proteins with the largest 14N/15N ratios in the p45 cerebellum analysis are proteins that have been reported to be highly expressed in the cerebellum compared to other brain regions (Supplemental Table 2). For example, the gamma-aminobutyric-acid receptor alpha-6 subunit and metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 are abundantly expressed in the cerebellum and had 14N/15N ratios of 2.14 and 2.37, respectively (Luddens et al. 1990; Shigemoto et al. 1992). Thus, future investigation into proteomic differences between brain regions with our SILAM strategy will facilitate the molecular understanding of their unique biological activity and their specific vulnerability in neurological diseases.

The most complex developmental patterns were observed with mitochondrial proteins. It has been shown that an increase in activity of mitochondrial enzymes does occur during post-natal development (Szutowicz et al. 1982; Bukato et al. 1992; Almeida et al. 1995). Although enzyme activity and expression do not necessarily correspond, we observed significant increases in the expression of mitochondrial proteins from p1 to p45 that correspond to reports on enzyme activity. Diverse developmental patterns of mitochondrial activity during post-natal brain development, however, also have been reported. For example, it has been reported complex I activity does not change during post-natal development, complex IV activity peaks a p20, and complex V activity increases linearly from p10 to p60 in the brain (Almeida et al. 1995). These complex developmental patterns have also been previously reported for the expression of similar functional mitochondrial proteins. For example, it has been reported that cytochrome aa3 and cc1 expression are significantly increased from p5 to p90, but there is no significant difference between the expression of cytochrome b between these time points (Kalous et al. 2001). However, cytochrome b expression was significantly increased at p30 compared to p5 and p90 (Kalous et al. 2001). We observed two major trends of mitochondrial protein expression. One developmental pattern was the expression increasing linearly with development, while the other pattern was expression peaking at p20 and then decreasing rapidly. The biological significance of these different developmental patterns is not understood. One hypothesis is that specific energy demands are greater for the developing brain compared to the adult brain. For example, myelination is complete after the first month of post-natal development, and thus in the adult, there are little energy demands connected with the synthesis of membrane phospholipids and lipids necessary for myelination. Overall, it is known that synaptic mitochondria redistribute and enhance their activity upon neuronal stimulation (Miller and Sheetz 2004), but the exact role(s) of the high density of mitochondria at the synapses remains elusive (Ly and Verstreken 2006). Neurological diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and hereditary spastic paraplegia, are hypothesized to result from the disruption of mitochondria delivery to the synapse (Reid 2003; Shaw 2005). Thus, further investigation of the mitochondrial proteome during synaptic development will elucidate mitochondrial functions at the synapse and provide insight into potential therapy for neurological disorders.

If protein expression increases during post-natal development and maintains this elevated expression level in the adult brain, this indicates the protein is necessary for the mature neuronal circuits to maintain adult brain function. For example, adult knockout mice lacking the GluR2 subunit of the AMPA receptor appear normal but are impaired in motor coordination and novelty-induced exploratory activities in the adult (Jia et al. 1996). If, however, the expression decreases during post-natal development, this suggests a role in the correct formation of the complex circuitry of the adult brain. For example, it is well known that the neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAMs) play a pivotal role in the formation of accurate neural connections during development (Jessell 1988), and the expression of the NCAM proteins decrease during post-natal development (Kamiguchi et al. 1998). In contrast to GluR2, dramatic malformations of the brain are observed in L1 NCAM knockout mice consistent with the brain malformations caused by L1 NCAM mutations in human disease (Akopians et al. 2003). In our analysis, we quantified 19 proteins whose expression decreased during post-natal development. For example, we observed a decrease in the protein expression of the neural NCAM-1, which is the founding member of the NCAM protein family (Linnemann and Bock 1989). We also observed a decrease in the expression of G-protein-coupled receptor 56 during post-natal development, which has been previously described (Piao et al. 2004). Mutations in this protein have been reported to cause a human brain cortical malformation called bilateral frontoparietal polymicrogyria (BFPP), which is characterized by disorganized cortical lamination (Piao et al. 2004). In addition, we observed a decrease in expression of previously uncharacterized proteins. For example, the expression of p100 was also observed to decrease from p1 to p45. Although this protein has yet to be characterized in the brain, it has been demonstrated to interact with STAT6 (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription member 6), whose expression has been reported to decrease during post-natal development (De-Fraja et al. 1998; Yang et al. 2002). Interestingly, STAT6 has been hypothesized to play a role in the neurodevelopmental disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but the molecular mechanism is not known (Tsai 2006). Another relatively uncharacterized brain protein, whose expression decreased during post-natal development in our study, was solute carrier family 25 member 1 protein. Although this protein has not been studied during post-natal development, polymorphisms in its gene have been linked to schizophrenia (Williams et al. 2002), which is hypothesized to manifest from abnormal neurodevelopment (Arnold et al. 2005). Ultimately, the decrease in the expression of the proteins observed in this study previously with no known role in neurodevelopment may provide novel insight into the correct formation of neural networks.

The synapse is a very challenging proteome to validate our quantification strategy. Synapses are complex organelles, which are not only equipped with the proteins required for neurotransmission and a variety of receptor signaling pathways but also contain their own metabolic pathways and organelles (mitochondria) for local generation of energy, as well as the cytoskeletal structures for moving vesicles and for changing the shape of the synapse. These synapses are also highly dynamic due to changes in local translation and degradation, in addition to the ease of protein traffic in and out of this “open” organelle (Sutton and Schuman 2005; Bingol and Schuman 2006). Although the molecular understanding of functional synapses is still in its early stages, the most consistent model is that the synapse is not one linear biochemical pathway but a complex interplay of hundreds of proteins to form a complicated molecular network. If this is true, a complete understanding of the complexities of synapses during development will require large-scale quantitative proteomic analysis. Thus, the global and unbiased analysis of mass spectrometry holds great potential to provide valuable insight into brain function, but the generation of appropriate internal standards for quantitative analysis has been problematic. We circumvented this problem by employing SILAM. In addition, this is the first large-scale quantitative analysis of synaptic proteins during post-natal development, which is the beginning of a valuable database for biomedical research. Many neurological diseases, including Rett syndrome, autism, and schizophrenia, are caused by alterations during neurodevelopment, but the cellular mechanisms are poorly understood (Hagberg et al. 1983; Belichenko et al. 1997; Amir et al. 1999; Belmonte et al. 2004; Arnold et al. 2005). The documentation of changes in protein expression during normal neurodevelopment is necessary, however, before aberrations in protein expression of neurodevelopment diseases can be identified. Thus, the quantitative method we describe here provides a novel approach to study animal models of neurological diseases.

Methods

Metabolic 15N labeling of rat brains

Sprague-Dawley rats were labeled with 15N as previously described (Wu and MacCoss 2004; McClatchy et al. 2007) Briefly, a female rat was fed an 15N-labeled protein diet starting after weaning, remaining on the 15N diet through its pregnancy and while weaning its pups. On post-natal day 45 (p45), the pups were subjected to halothane by inhalation until unresponsive, and the brains were quickly removed and frozen with liquid nitrogen. The brains were homogenized in 0.32 M sucrose, 4 mM HEPES, and protease inhibitors, and the homogenates were stored at –80°C. The 15N enrichment was determined to be 94% using a previously described protocol (MacCoss et al. 2005). All methods involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Research Committee and accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Isolation and digestion of synaptosomes

Sprague-Dawley rats at four post-natal development time points (p1, p10, p20, and p45,) were sacrificed, and the brains were quickly removed, dissected, and then frozen with liquid nitrogen. The cerebella from multiple rats from the same age group were homogenized together in 0.32 M sucrose, 4 mM HEPES, and protease inhibitors. After a BCA protein assay (Pierce), each developmental cerebellar homogenate was mixed in a 1:1 (w/w) ratio with 15N-labeled rat brain homogenate, and synaptosomes were isolated as previously described (Carlin et al. 1980). Aliquots of the same 15N-labeled rat brain homogenate were used for each developmental period to ensure uniform quantitation. The synaptosomal fraction was digested with proteinase K (Roche Applied Science) as previously described (Wu et al. 2003).

Western blot analysis

Synaptosomal fractions and total cerebellar homogenate were prepared in 2% SDS, separated by 8%–16% Tris-Glycine gel (Invitrogen), and electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). Membranes were processed as previously described (Berkeley and Levey 2000). Membranes were probed with the following antibodies: rabbit glutamate receptor 2/3 antibody, rabbit Na+/K+ ATPase alpha-1 chain antibody, and H3 histone antibody (Upstate Biotechnology), mouse alpha-tubulin antibody (Sigma), mouse cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1, mouse PSD-95 antibody, and rabbit synapsin antibody (Molecular Probes).

Quantitative Western blot analysis

Three synaptosomal fractions were generated from p1 cerebella, and three synaptosomal fractions were generated from p45 cerebella. The starting material for each preparation was cerebellar homogenate pooled from three cerebella. In total, 18 cerebella were homogenized. For a particular antibody, two immunoblots were performed each consisting of three p1 and three p45 samples. For antibodies where both the synaptosomal fraction and total homogenate was analyzed, two immunoblots were performed for each fraction making a total of four immunoblots. The immunoreactivity of each antibody was determined by PhotoShop (Adobe Systems) on two different immunoblots, and thus, N = 6 for each developmental period for each antibody. Briefly, the scanned image of an immunoblot was first inverted, and then the threshold was adjusted until the least intense immunoreactive band was barely visible. The mean pixel intensity was recorded for each band on the image employing a rectangular cursor of identical dimensions for each band.

Multidimensional Protein Identification Technology (MudPIT)

The digestion products from each developmental period were analyzed three times by MudPIT. For a single analysis, 100 μg of the digested sample was pressure-loaded onto a fused silica capillary desalting column containing 5 cm of 5 μm Polaris C18-A material (Metachem) packed into a 250-μm i.d. capillary with a 2-μm filtered union (UpChurch Scientific). The desalting column was washed with buffer containing 95% water, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid. After desalting, a 100-μm i.d. capillary with a 5-μm pulled tip packed with 7 cm of 5-μm Aqua C18 material (Phenomenex) followed by 3 cm of 5-μm Partisphere strong cation exchanger (Whatman) was attached to the filter union, and the entire split-column (desalting column–filter union–analytical column) was placed inline with an Agilent 1100 quaternary HPLC and analyzed using a modified 12-step separation described previously (Washburn et al. 2001). The buffer solutions used were 5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (buffer A), 80% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (buffer B), and 500 mM ammonium acetate/5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid (buffer C). Step 1 consisted of a 100-min gradient from 0%–100% buffer B. Steps 2–11 had the following profile: 3 min of 100% buffer A, 2 min of X% buffer C, a 10-min gradient from 0%–15% buffer B, and a 97-min gradient from 15%–45% buffer B. The 2-min buffer C percentages (X) were 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 35%, 40%, 45%, 50%, and 60%, respectively, for the 12-step analysis. The final step, the gradient contained: 3 min of 100% buffer A, 20 min of 100% buffer C, a 10-min gradient from 0%–15% buffer B, and a 107-min gradient from 15%–70% buffer B.

As peptides eluted from the microcapillary column, they were electrosprayed directly into an LTQ 2-dimensional IT mass spectrometer (ThermoFinnigan) with the application of a distal 2.4-kV spray voltage. A cycle of one full-scan mass spectrum (400–1400 m/z) followed by six data-dependent tandem mass spectra was repeated continuously throughout each step of the multidimensional separation. All tandem mass spectra were collected using normalized collision energy (a setting of 35%), an isolation window of 3 m/z, and 1 μscan. Application of mass spectrometer scan functions and HPLC solvent gradients were controlled by the XCalibur data system (ThermoFinnigan).

Interpretation of tandem mass spectra

Both MS and tandem mass spectra were extracted from the XCalibur data system format (.RAW) into MS1 and MS2 formats (McDonald et al. 2004) using in house software (RAW_Xtractor). Tandem mass spectra were interpreted by SEQUEST (Eng et al. 1994), which was parallelized on a Beowulf cluster of 100 computers (Sadygov et al. 2002), and results were filtered, sorted, and displayed using the DTASelect2 program using a decoy database strategy (Elias and Gygi 2007). For each MudPIT analysis, the protein false-positive rate was <1%. Specifically, the distribution of SEQUEST values (i.e., Xcorr, DeltaCN, and DeltaMass) for (1) direct and (2) decoy database hits was obtained, and the two subsets were separated by quadratic discriminant analysis. Outlier points in the two distributions (e.g., matches with very low Xcorr but very high DeltCN) were discarded. Full separation of the direct and decoy subsets is not generally possible; therefore, the discriminant score was set such that a false-positive rate of 5% was determined based on the number of accepted decoy database peptides. In addition, a minimum sequence length of seven amino acid residues was required, and each protein on the list was supported by at least two peptide identifications. These additional requirements—especially the latter—resulted in the elimination of most decoy database and false-positive hits, as these tended to be overwhelmingly present as proteins identified by single peptide matches. After this last filtering step, the false identification rate was reduced to below 1%. Searches were performed against the rat International Protein Index (IPI) database (IPI, v3.05).

Quantitative analysis using Census

After filtering the results from SEQUEST using DTASelect2, ion chromatograms were generated using an updated version of a program previously written in our laboratory (MacCoss et al. 2003). This software, called Census (Park et al. 2006), is available from the authors for individual use and evaluation through an Institutional Software Transfer Agreement (for details, see http://fields.scripps.edu/census).

First, the elemental compositions and corresponding isotopic distributions for both the unlabeled and labeled peptides were calculated, and this information was then used to determine the appropriate m/z range from which to extract ion intensities, which included all isotopes with >5% of the calculated isotope cluster base peak abundance. MS1 files were used to generate chromatograms from the m/z range surrounding both the unlabeled and labeled precursor peptides.

Census calculates peptide ion intensity ratios for each pair of extracted ion chromatograms. The heart of the program is a linear least-squares correlation that is used to calculate the ratio (i.e., slope of the line) and closeness of fit (i.e., correlation coefficient [r]) between the data points of the unlabeled and labeled ion chromatograms. Census allows users to filter peptide ratio measurements based on a correlation threshold because the correlation coefficient (values between zero and one) represents the quality of the correlation between the unlabeled and labeled chromatograms, and can be used to filter out poor quality measurements. In this study, only peptide ratios with correlation values >0.5 were used for further analysis. In addition, Census provides an automated method for detecting and removing statistical outliers. In brief, standard deviations are calculated for all proteins using their respective peptide ratio measurements. The Grubbs test (P < 0.01) is then applied to remove outlier peptides. The outlier algorithm is used only when there are more than three peptides found in the same proteins, because the algorithm becomes unreliable for a small number of measurements.

Statistical analysis

Before statistical analysis, the median of the natural log of the ratios from each MudPIT analysis was calculated, and then, all the medians were shifted to zero. The calculated medians were very similar, and it was assumed any shift in the median was due to human error in the protein mixing. For statistical analysis, each 14N/15N peptide ratio for a given protein was considered one measurement or N = 1. The peptide ratios from the three analyses for one development stage were combined for a given protein. First, one-way ANOVA analysis was performed on proteins that were quantified in at least three developmental stages. If protein changes had a P value < 0.05, then two post-hoc tests were performed: Bonferroni test and a test for a linear trend. All statistical tests were performed using Prism 4 Software (GraphPad).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Greg Cantin for his critical reading of this manuscript. We acknowledge financial support from National Institutes of Health grants 5R01 MH067880-02 and P41 RR11823-10.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.6375007

References

- Akopians A., Runyan S.A., Phelps P.E., Runyan S.A., Phelps P.E., Phelps P.E. Expression of L1 decreases during postnatal development of rat spinal cord. J. Comp. Neurol. 2003;467:375–388. doi: 10.1002/cne.10956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A., Brooks K.J., Sammut I., Keelan J., Davey G.P., Clark J.B., Bates T.E., Brooks K.J., Sammut I., Keelan J., Davey G.P., Clark J.B., Bates T.E., Sammut I., Keelan J., Davey G.P., Clark J.B., Bates T.E., Keelan J., Davey G.P., Clark J.B., Bates T.E., Davey G.P., Clark J.B., Bates T.E., Clark J.B., Bates T.E., Bates T.E. Postnatal development of the complexes of the electron transport chain in synaptic mitochondria from rat brain. Dev. Neurosci. 1995;17:212–218. doi: 10.1159/000111289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J., Bayer S.A., Bayer S.A. Development of the cerebellar system. CRC Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Amir R.E., Van den Veyver I.B., Wan M., Tran C.Q., Francke U., Zoghbi H.Y., Van den Veyver I.B., Wan M., Tran C.Q., Francke U., Zoghbi H.Y., Wan M., Tran C.Q., Francke U., Zoghbi H.Y., Tran C.Q., Francke U., Zoghbi H.Y., Francke U., Zoghbi H.Y., Zoghbi H.Y. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:185–188. doi: 10.1038/13810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold S.E., Talbot K., Hahn C.G., Talbot K., Hahn C.G., Hahn C.G. Neurodevelopment, neuroplasticity, and new genes for schizophrenia. Prog. Brain Res. 2005;147:319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(04)47023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belichenko P.V., Hagberg B., Dahlstrom A., Hagberg B., Dahlstrom A., Dahlstrom A. Morphological study of neocortical areas in Rett syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 1997;93:50–61. doi: 10.1007/s004010050582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte M.K., Allen G., Beckel-Mitchener A., Boulanger L.M., Carper R.A., Webb S.J., Allen G., Beckel-Mitchener A., Boulanger L.M., Carper R.A., Webb S.J., Beckel-Mitchener A., Boulanger L.M., Carper R.A., Webb S.J., Boulanger L.M., Carper R.A., Webb S.J., Carper R.A., Webb S.J., Webb S.J. Autism and abnormal development of brain connectivity. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9228–9231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3340-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley J.L., Levey A.I., Levey A.I. Muscarinic activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:487–493. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingol B., Schuman E.M., Schuman E.M. Activity-dependent dynamics and sequestration of proteasomes in dendritic spines. Nature. 2006;441:1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature04769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Ong S.E., Nielsen M., Foster L.J., Mann M., Kratchmarova I., Ong S.E., Nielsen M., Foster L.J., Mann M., Ong S.E., Nielsen M., Foster L.J., Mann M., Nielsen M., Foster L.J., Mann M., Foster L.J., Mann M., Mann M. A proteomics strategy to elucidate functional protein-protein interactions applied to EGF signaling. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:315–318. doi: 10.1038/nbt790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukato G., Kochan Z., Swierczynski J., Kochan Z., Swierczynski J., Swierczynski J. Changes of malic enzyme activity in the developing rat brain are due to both the increase of mitochondrial protein content and the increase of specific activity. Int. J. Biochem. 1992;24:267–273. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(92)90257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagney G., Park S., Chung C., Tong B., O’Dushlaine C., Shields D.C., Emili A., Park S., Chung C., Tong B., O’Dushlaine C., Shields D.C., Emili A., Chung C., Tong B., O’Dushlaine C., Shields D.C., Emili A., Tong B., O’Dushlaine C., Shields D.C., Emili A., O’Dushlaine C., Shields D.C., Emili A., Shields D.C., Emili A., Emili A. Human tissue profiling with multidimensional protein identification technology. J. Proteome Res. 2005;4:1757–1767. doi: 10.1021/pr0500354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin R.K., Grab D.J., Cohen R.S., Siekevitz P., Grab D.J., Cohen R.S., Siekevitz P., Cohen R.S., Siekevitz P., Siekevitz P. Isolation and characterization of postsynaptic densities from various brain regions: Enrichment of different types of postsynaptic densities. J. Cell Biol. 1980;86:831–845. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng D., Hoogenraad C.C., Rush J., Ramm E., Schlager M.A., Duong D.M., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Hoogenraad C.C., Rush J., Ramm E., Schlager M.A., Duong D.M., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Rush J., Ramm E., Schlager M.A., Duong D.M., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Ramm E., Schlager M.A., Duong D.M., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Schlager M.A., Duong D.M., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Duong D.M., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Xu P., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Wijayawardana S.R., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Hanfelt J., Nakagawa T., Nakagawa T., et al. Relative and absolute quantification of postsynaptic density proteome isolated from rat forebrain and cerebellum. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:1158–1170. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D500009-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary J., Grant S.G., Grant S.G. Proteomics in postgenomic neuroscience: The end of the beginning. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:440–445. doi: 10.1038/nn1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrads T.P., Alving K., Veenstra T.D., Belov M.E., Anderson G.A., Anderson D.J., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Alving K., Veenstra T.D., Belov M.E., Anderson G.A., Anderson D.J., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Veenstra T.D., Belov M.E., Anderson G.A., Anderson D.J., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Belov M.E., Anderson G.A., Anderson D.J., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Anderson G.A., Anderson D.J., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Anderson D.J., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Lipton M.S., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Pasa-Tolic L., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Udseth H.R., Chrisler W.B., Chrisler W.B., et al. Quantitative analysis of bacterial and mammalian proteomes using a combination of cysteine affinity tags and 15N-metabolic labeling. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:2132–2139. doi: 10.1021/ac001487x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepel F. Maturation of the cerebellar Purkinje cell: Postnatal evolution of the Purkinje cell spontaneous firing in the rat. Exp. Brain Res. 1972;14:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- De-Fraja C., Conti L., Magrassi L., Govoni S., Cattaneo E., Conti L., Magrassi L., Govoni S., Cattaneo E., Magrassi L., Govoni S., Cattaneo E., Govoni S., Cattaneo E., Cattaneo E. Members of the JAK/STAT proteins are expressed and regulated during development in the mammalian forebrain. J. Neurosci. Res. 1998;54:320–330. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19981101)54:3<320::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duenas A.M., Goold R., Giunti P., Goold R., Giunti P., Giunti P. Molecular pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxias. Brain. 2006;129:1357–1370. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias J.E., Gygi S.P., Gygi S.P. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng J.K., McCormack A.L., Yates J.R., McCormack A.L., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecinska M., Cherian S., Silver I.A., Cherian S., Silver I.A., Silver I.A. Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004;73:397–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everley P.A., Bakalarski C.E., Elias J.E., Waghorne C.G., Beausoleil S.A., Gerber S.A., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Bakalarski C.E., Elias J.E., Waghorne C.G., Beausoleil S.A., Gerber S.A., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Elias J.E., Waghorne C.G., Beausoleil S.A., Gerber S.A., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Waghorne C.G., Beausoleil S.A., Gerber S.A., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Beausoleil S.A., Gerber S.A., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Gerber S.A., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Faherty B.K., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Zetter B.R., Gygi S.P., Gygi S.P. Enhanced analysis of metastatic prostate cancer using stable isotopes and high mass accuracy instrumentation. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5:1224–1231. doi: 10.1021/pr0504891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett D.R., Keller A., Watts J.D., Newitt R., Yi E.C., Purvine S., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Keller A., Watts J.D., Newitt R., Yi E.C., Purvine S., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Watts J.D., Newitt R., Yi E.C., Purvine S., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Newitt R., Yi E.C., Purvine S., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Yi E.C., Purvine S., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Purvine S., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Eng J.K., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., von Haller P., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Aebersold R., Kolker E., Kolker E. Differential stable isotope labeling of peptides for quantitation and de novo sequence derivation. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:1214–1221. doi: 10.1002/rcm.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruhler A., Olsen J.V., Mohammed S., Mortensen P., Faergeman N.J., Mann M., Jensen O.N., Olsen J.V., Mohammed S., Mortensen P., Faergeman N.J., Mann M., Jensen O.N., Mohammed S., Mortensen P., Faergeman N.J., Mann M., Jensen O.N., Mortensen P., Faergeman N.J., Mann M., Jensen O.N., Faergeman N.J., Mann M., Jensen O.N., Mann M., Jensen O.N., Jensen O.N. Quantitative phosphoproteomics applied to the yeast pheromone signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:310–327. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400219-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafidi A., Hillman D.E., Hillman D.E. Distribution of glutamate receptors GluR 2/3 and NR1 in the developing rat cerebellum. Neuroscience. 1997;81:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg B., Aicardi J., Dias K., Ramos O., Aicardi J., Dias K., Ramos O., Dias K., Ramos O., Ramos O. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett’s syndrome: report of 35 cases. Ann. Neurol. 1983;14:471–479. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K.C., Schmitt-Ulms G., Chalkley R.J., Hirsch J., Baldwin M.A., Burlingame A.L., Schmitt-Ulms G., Chalkley R.J., Hirsch J., Baldwin M.A., Burlingame A.L., Chalkley R.J., Hirsch J., Baldwin M.A., Burlingame A.L., Hirsch J., Baldwin M.A., Burlingame A.L., Baldwin M.A., Burlingame A.L., Burlingame A.L. Mass spectrometric analysis of protein mixtures at low levels using cleavable 13C-isotope-coded affinity tag and multidimensional chromatography. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2003;2:299–314. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300021-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haqqani A.S., Nesic M., Preston E., Baumann E., Kelly J., Stanimirovic D., Nesic M., Preston E., Baumann E., Kelly J., Stanimirovic D., Preston E., Baumann E., Kelly J., Stanimirovic D., Baumann E., Kelly J., Stanimirovic D., Kelly J., Stanimirovic D., Stanimirovic D. Characterization of vascular protein expression patterns in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion using laser capture microdissection and ICAT-nanoLC-MS/MS. FASEB J. 2005;19:1809–1821. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3793com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Qian J., Borisov O., Pan S., Li Y., Liu T., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Qian J., Borisov O., Pan S., Li Y., Liu T., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Borisov O., Pan S., Li Y., Liu T., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Pan S., Li Y., Liu T., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Li Y., Liu T., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Liu T., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Deng L., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Wannemacher K., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Kurnellas M., Patterson C., Patterson C., et al. Optimized proteomic analysis of a mouse model of cerebellar dysfunction using amine-specific isobaric tags. Proteomics. 2006;6:4321–4334. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T.C., Yang L., Zhu H., Majidi V., Bradbury E.M., Chen X., Yang L., Zhu H., Majidi V., Bradbury E.M., Chen X., Zhu H., Majidi V., Bradbury E.M., Chen X., Majidi V., Bradbury E.M., Chen X., Bradbury E.M., Chen X., Chen X. Peptide mass mapping constrained with stable isotope-tagged peptides for identification of protein mixtures. Anal. Chem. 2001;73:4891–4902. doi: 10.1021/ac0103322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama Y., Sato T., Tabata T., Miyamoto N., Sagane K., Nagasu T., Oda Y., Sato T., Tabata T., Miyamoto N., Sagane K., Nagasu T., Oda Y., Tabata T., Miyamoto N., Sagane K., Nagasu T., Oda Y., Miyamoto N., Sagane K., Nagasu T., Oda Y., Sagane K., Nagasu T., Oda Y., Nagasu T., Oda Y., Oda Y. Quantitative mouse brain proteomics using culture-derived isotope tags as internal standards. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:617–621. doi: 10.1038/nbt1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessell T.M. Adhesion molecules and the hierarchy of neural development. Neuron. 1988;1:3–13. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Z., Agopyan N., Miu P., Xiong Z., Henderson J., Gerlai R., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Agopyan N., Miu P., Xiong Z., Henderson J., Gerlai R., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Miu P., Xiong Z., Henderson J., Gerlai R., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Xiong Z., Henderson J., Gerlai R., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Henderson J., Gerlai R., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Gerlai R., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Taverna F.A., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Velumian A., MacDonald J., Carlen P., MacDonald J., Carlen P., Carlen P., et al. Enhanced LTP in mice deficient in the AMPA receptor GluR2. Neuron. 1996;17:945–956. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J., Meredith G.E., Chen L., Zhou Y., Xu J., Shie F.S., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Meredith G.E., Chen L., Zhou Y., Xu J., Shie F.S., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Chen L., Zhou Y., Xu J., Shie F.S., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Zhou Y., Xu J., Shie F.S., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Xu J., Shie F.S., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Shie F.S., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Lockhart P., Zhang J., Zhang J. Quantitative proteomic analysis of mitochondrial proteins: Relevance to Lewy body formation and Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2005;134:119–138. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalous K., Rauchová H., Drahota Z., Rauchová H., Drahota Z., Drahota Z. Postnatal development of energy metabolism in the rat brain. Physiol. Res. 2001;50:315–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiguchi H., Hlavin M.L., Lemmon V., Hlavin M.L., Lemmon V., Lemmon V. Role of L1 in neural development: What the knockouts tell us. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1998;12:48–55. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalyfa A., Bourbeau D., Chen E., Petroulakis E., Pan J., Xu S., Wang E., Bourbeau D., Chen E., Petroulakis E., Pan J., Xu S., Wang E., Chen E., Petroulakis E., Pan J., Xu S., Wang E., Petroulakis E., Pan J., Xu S., Wang E., Pan J., Xu S., Wang E., Xu S., Wang E., Wang E. Characterization of elongation factor-1A (eEF1A-1) and eEF1A-2/S1 protein expression in normal and wasted mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:22915–22922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krijgsveld J., Ketting R.F., Mahmoudi T., Johansen J., Artal-Sanz M., Verrijzer C.P., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Ketting R.F., Mahmoudi T., Johansen J., Artal-Sanz M., Verrijzer C.P., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Mahmoudi T., Johansen J., Artal-Sanz M., Verrijzer C.P., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Johansen J., Artal-Sanz M., Verrijzer C.P., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Artal-Sanz M., Verrijzer C.P., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Verrijzer C.P., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Plasterk R.H., Heck A.J., Heck A.J. Metabolic labeling of C. elegans and D. melanogaster for quantitative proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:927–931. doi: 10.1038/nbt848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H., Eng J., Yates J.R., Tollaksen S.L., Giometti C.S., Holden J.F., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Eng J., Yates J.R., Tollaksen S.L., Giometti C.S., Holden J.F., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Yates J.R., Tollaksen S.L., Giometti C.S., Holden J.F., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Tollaksen S.L., Giometti C.S., Holden J.F., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Giometti C.S., Holden J.F., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Holden J.F., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Adams M.W., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Reich C.I., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Olsen G.J., Hays L.G., Hays L.G. Identification of 2D-gel proteins: A comparison of MALDI/TOF peptide mass mapping to mu LC-ESI tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:957–970. doi: 10.1016/s1044-0305(03)00144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnemann D., Bock E., Bock E. Cell adhesion molecules in neural development. Dev. Neurosci. 1989;11:149–173. doi: 10.1159/000111896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luddens H., Pritchett D.B., Kohler M., Killisch I., Keinanen K., Monyer H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Pritchett D.B., Kohler M., Killisch I., Keinanen K., Monyer H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Kohler M., Killisch I., Keinanen K., Monyer H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Killisch I., Keinanen K., Monyer H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Keinanen K., Monyer H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Monyer H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Sprengel R., Seeburg P.H., Seeburg P.H. Cerebellar GABAA receptor selective for a behavioural alcohol antagonist. Nature. 1990;346:648–651. doi: 10.1038/346648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly C.V., Verstreken P., Verstreken P. Mitochondria at the synapse. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:291–299. doi: 10.1177/1073858406287661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCoss M.J., Wu C.C., Liu H., Sadygov R., Yates J.R., Wu C.C., Liu H., Sadygov R., Yates J.R., Liu H., Sadygov R., Yates J.R., Sadygov R., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. A correlation algorithm for the automated quantitative analysis of shotgun proteomics data. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:6912–6921. doi: 10.1021/ac034790h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCoss M.J., Wu C.C., Matthews D.E., Yates J.R., Wu C.C., Matthews D.E., Yates J.R., Matthews D.E., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. Measurement of the isotope enrichment of stable isotope-labeled proteins using high-resolution mass spectra of peptides. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:7646–7653. doi: 10.1021/ac0508393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M.P., Pedersen W.A., Duan W., Culmsee C., Camandola S., Pedersen W.A., Duan W., Culmsee C., Camandola S., Duan W., Culmsee C., Camandola S., Culmsee C., Camandola S., Camandola S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying perturbed energy metabolism and neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;893:154–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClatchy D.B., Dong M.Q., Wu C.C., Venable J.D., Yates J.R., Dong M.Q., Wu C.C., Venable J.D., Yates J.R., Wu C.C., Venable J.D., Yates J.R., Venable J.D., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. 15N metabolic labeling of mammalian tissue with slow protein turnover. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:2005–2010. doi: 10.1021/pr060599n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald W.H., Tabb D.L., Sadygov R.G., MacCoss M.J., Venable J., Graumann J., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., Tabb D.L., Sadygov R.G., MacCoss M.J., Venable J., Graumann J., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., Sadygov R.G., MacCoss M.J., Venable J., Graumann J., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., MacCoss M.J., Venable J., Graumann J., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., Venable J., Graumann J., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., Graumann J., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., Johnson J.R., Cociorva D., Cociorva D. MS1, MS2, and SQT—Three unified, compact, and easily parsed file formats for the storage of shotgun proteomic spectra and identifications. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2162–2168. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon H.T., Nicholls D.G., Nicholls D.G. The bioenergetics of neurotransmitter release. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1991;1059:243–264. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meany D.L., Xie H., Thompson L.V., Arriaga E.A., Griffin T.J., Xie H., Thompson L.V., Arriaga E.A., Griffin T.J., Thompson L.V., Arriaga E.A., Griffin T.J., Arriaga E.A., Griffin T.J., Griffin T.J. Identification of carbonylated proteins from enriched rat skeletal muscle mitochondria using affinity chromatography-stable isotope labeling and tandem mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2007;7:1150–1163. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K.E., Sheetz M.P., Sheetz M.P. Axonal mitochondrial transport and potential are correlated. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2791–2804. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar L.R., Thayne K.A., Fleming W.W., Taylor D.A., Thayne K.A., Fleming W.W., Taylor D.A., Fleming W.W., Taylor D.A., Taylor D.A. The role of the sodium pump in the developmental regulation of membrane electrical properties of cerebellar Purkinje neurons of the rat. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1999;112:287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls D.G. The glutamatergic nerve terminal. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;212:613–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y., Huang K., Cross F.R., Cowburn D., Chait B.T., Huang K., Cross F.R., Cowburn D., Chait B.T., Cross F.R., Cowburn D., Chait B.T., Cowburn D., Chait B.T., Chait B.T. Accurate quantitation of protein expression and site specific phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96:6591–6596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J.V., Nielsen P.A., Andersen J.R., Mann M., Wisniewski J.R., Nielsen P.A., Andersen J.R., Mann M., Wisniewski J.R., Andersen J.R., Mann M., Wisniewski J.R., Mann M., Wisniewski J.R., Wisniewski J.R. Quantitative proteomic profiling of membrane proteins from the mouse brain cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum using the HysTag reagent: Mapping of neurotransmitter receptors and ion channels. Brain Res. 2007;1134:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong S.-E., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D.B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D.B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D.B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M., Kristensen D.B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M., Pandey A., Mann M., Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1:376–386. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200025-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C., Kora G., McDonald W.H., Tabb D.L., Verberkmoes N.C., Hurst G.B., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Kora G., McDonald W.H., Tabb D.L., Verberkmoes N.C., Hurst G.B., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., McDonald W.H., Tabb D.L., Verberkmoes N.C., Hurst G.B., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Tabb D.L., Verberkmoes N.C., Hurst G.B., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Verberkmoes N.C., Hurst G.B., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Hurst G.B., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Pelletier D.A., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Samatova N.F., Hettich R.L., Hettich R.L. ProRata: A quantitative proteomics program for accurate protein abundance ratio estimation with confidence interval evaluation. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:7121–7131. doi: 10.1021/ac060654b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.K., Venable J.D., Xu T., Liao L., Yates J.R., Venable J.D., Xu T., Liao L., Yates J.R., Xu T., Liao L., Yates J.R., Liao L., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. Human Proteome Organisation Fifth Annual World Congress. Long Beach; CA: 2006. A tool for quantitative analysis of high-throughput mass spectrometry data. [Google Scholar]

- Peng J., Kim M.J., Cheng D., Duong D.M., Gygi S.P., Sheng M., Kim M.J., Cheng D., Duong D.M., Gygi S.P., Sheng M., Cheng D., Duong D.M., Gygi S.P., Sheng M., Duong D.M., Gygi S.P., Sheng M., Gygi S.P., Sheng M., Sheng M. Semiquantitative proteomic analysis of rat forebrain postsynaptic density fractions by mass spectrometry. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21003–21011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G.R., Anderson T.R., Florens L., Gudas C., Magda G., Yates J.R., Colman D.R., Anderson T.R., Florens L., Gudas C., Magda G., Yates J.R., Colman D.R., Florens L., Gudas C., Magda G., Yates J.R., Colman D.R., Gudas C., Magda G., Yates J.R., Colman D.R., Magda G., Yates J.R., Colman D.R., Yates J.R., Colman D.R., Colman D.R. Actin-binding proteins in a postsynaptic preparation: Lasp-1 is a component of central nervous system synapses and dendritic spines. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;78:38–48. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao X., Hill R.S., Bodell A., Chang B.S., Basel-Vanagaite L., Straussberg R., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Hill R.S., Bodell A., Chang B.S., Basel-Vanagaite L., Straussberg R., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Bodell A., Chang B.S., Basel-Vanagaite L., Straussberg R., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Chang B.S., Basel-Vanagaite L., Straussberg R., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Basel-Vanagaite L., Straussberg R., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Straussberg R., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Dobyns W.B., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Qasrawi B., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Winter R.M., Innes A.M., Innes A.M., et al. G protein-coupled receptor-dependent development of human frontal cortex. Science. 2004;303:2033–2036. doi: 10.1126/science.1092780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokai L., Zharikova A.D., Stevens S.M., Zharikova A.D., Stevens S.M., Stevens S.M. Effect of chronic morphine exposure on the synaptic plasma-membrane subproteome of rats: A quantitative protein profiling study based on isotope-coded affinity tags and liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2005;40:169–175. doi: 10.1002/jms.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid E. Science in motion: common molecular pathological themes emerge in the hereditary spastic paraplegias. J. Med. Genet. 2003;40:81–86. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadygov R.G., Eng J., Durr E., Saraf A., McDonald H., MacCoss M.J., Yates J.R., Eng J., Durr E., Saraf A., McDonald H., MacCoss M.J., Yates J.R., Durr E., Saraf A., McDonald H., MacCoss M.J., Yates J.R., Saraf A., McDonald H., MacCoss M.J., Yates J.R., McDonald H., MacCoss M.J., Yates J.R., MacCoss M.J., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. Code developments to improve the efficiency of automated MS/MS spectra interpretation. J. Proteome Res. 2002;1:211–215. doi: 10.1021/pr015514r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimpf S.P., Meskenaite V., Brunner E., Rutishauser D., Walther P., Eng J., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Meskenaite V., Brunner E., Rutishauser D., Walther P., Eng J., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Brunner E., Rutishauser D., Walther P., Eng J., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Rutishauser D., Walther P., Eng J., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Walther P., Eng J., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Eng J., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Aebersold R., Sonderegger P., Sonderegger P. Proteomic analysis of synaptosomes using isotope-coded affinity tags and mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2005;5:2531–2541. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P.J. Molecular and cellular pathways of neurodegeneration in motor neurone disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2005;76:1046–1057. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R., Nakanishi S., Mizuno N., Nakanishi S., Mizuno N., Mizuno N. Distribution of the mRNA for a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) in the central nervous system: An in situ hybridization study in adult and developing rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1992;322:121–135. doi: 10.1002/cne.903220110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M.A., Schuman E.M., Schuman E.M. Local translational control in dendrites and its role in long-term synaptic plasticity. J. Neurobiol. 2005;64:116–131. doi: 10.1002/neu.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szutowicz A., Kabata J., Bielarczyk H., Kabata J., Bielarczyk H., Bielarczyk H. The contribution of citrate to the synthesis of acetyl units in synaptosomes of developing rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1982;38:1196–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb07891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S.J. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A speculative hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses. 2006;67:1342–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venable J.D., Dong M.Q., Wohlschlegel J., Dillin A., Yates J.R., Dong M.Q., Wohlschlegel J., Dillin A., Yates J.R., Wohlschlegel J., Dillin A., Yates J.R., Dillin A., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. Automated approach for quantitative analysis of complex peptide mixtures from tandem mass spectra. Nat. Methods. 2004;1:39–45. doi: 10.1038/nmeth705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernier P., Moret F., Callier S., Snapyan M., Wersinger C., Sidhu A., Moret F., Callier S., Snapyan M., Wersinger C., Sidhu A., Callier S., Snapyan M., Wersinger C., Sidhu A., Snapyan M., Wersinger C., Sidhu A., Wersinger C., Sidhu A., Sidhu A. The degeneration of dopamine neurons in Parkinson’s disease: Insights from embryology and evolution of the mesostriatocortical system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1035:231–249. doi: 10.1196/annals.1332.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosseller K., Hansen K.C., Chalkley R.J., Trinidad J.C., Wells L., Hart G.W., Burlingame A.L., Hansen K.C., Chalkley R.J., Trinidad J.C., Wells L., Hart G.W., Burlingame A.L., Chalkley R.J., Trinidad J.C., Wells L., Hart G.W., Burlingame A.L., Trinidad J.C., Wells L., Hart G.W., Burlingame A.L., Wells L., Hart G.W., Burlingame A.L., Hart G.W., Burlingame A.L., Burlingame A.L. Quantitative analysis of both protein expression and serine/threonine post-translational modifications through stable isotope labeling with dithiothreitol. Proteomics. 2005;5:388–398. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn M.P., Wolters D., Yates J.R., Wolters D., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn M.P., Ulaszek R., Deciu C., Schieltz D.M., Yates J.R., Ulaszek R., Deciu C., Schieltz D.M., Yates J.R., Deciu C., Schieltz D.M., Yates J.R., Schieltz D.M., Yates J.R., Yates J.R. Analysis of quantitative proteomic data generated via multidimensional protein identification technology. Anal. Chem. 2002;74:1650–1657. doi: 10.1021/ac015704l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker V.P., Michaelson I.A., Kirkland R.J., Michaelson I.A., Kirkland R.J., Kirkland R.J. The separation of synaptic vesicles from nerve-ending particles (“synaptosomes”) Biochem. J. 1964;90:293–303. doi: 10.1042/bj0900293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]