Abstract

We investigated the effect of afforestation and reforestation of pastures on methane oxidation and the methanotrophic communities in soils from three different New Zealand sites. Methane oxidation was measured in soils from two pine (Pinus radiata) forests and one shrubland (mainly Kunzea ericoides var. ericoides) and three adjacent permanent pastures. The methane oxidation rate was consistently higher in the pine forest or shrubland soils than in the adjacent pasture soils. A combination of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) and stable isotope probing (SIP) analyses of these soils revealed that different methanotrophic communities were active in soils under the different vegetations. The C18 PLFAs (signature of type II methanotrophs) predominated under pine and shrublands, and C16 PLFAs (type I methanotrophs) predominated under pastures. Analysis of the methanotrophs by molecular methods revealed further differences in methanotrophic community structure under the different vegetation types. Cloning and sequencing and terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of the particulate methane oxygenase gene (pmoA) from different samples confirmed the PLFA-SIP results that methanotrophic bacteria related to type II methanotrophs were dominant in pine forest and shrubland, and type I methanotrophs (related to Methylococcus capsulatus) were dominant in all pasture soils. We report that afforestation and reforestation of pastures caused changes in methane oxidation by altering the community structure of methanotrophic bacteria in these soils.

Methane (CH4) is an important greenhouse gas which accounts for up to 20% of global warming (33). It is present in the atmosphere at a mixing ratio of about 1.75 ppm by volume (ppmv), and its concentration has been increasing over the past 200 years, mainly due to anthropogenic activities such as fossil fuel exploration, rice production, large-scale animal husbandry of ruminants, biomass burning, and landfill use (10). Land use changes have also resulted in a change in CH4 oxidation by soils (1, 28, 29, 30, 43). For example, as a result of conversion of forests to agricultural land, the soil methane sink has been estimated to have decreased by up to 60% in different ecosystems and regions of the earth (40).

Methane oxidation by soil methanotrophic bacteria is a major terrestrial sink, accounting for up to 10% of the global CH4 sink (26). Methanotrophic bacteria are a unique gram-negative and aerobic group and are ubiquitous in nature. Based on physiological and biochemical characteristics, methanotrophs are traditionally divided into two main groups: type I methanotrophs (members of the gammaproteobacteria) and type II methanotrophs (members of the alphaproteobacteria) (17). As methanotrophs are exclusively responsible for oxidation of CH4 in soil and are potentially influenced by anthropogenic activities, there has been considerable interest in determining the community composition and physiological capabilities of methanotrophs and the impact of various treatments on the ambient-CH4-oxidizing bacterial community (6, 9, 24, 35). Bacteria that oxidize CH4 at an ambient concentration are notoriously difficult to culture and are, therefore, characterized mainly by culture-independent methods. Because phospholipids are considered to be indicators of living microorganisms in soil (45), phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis is widely used for the characterization of soil microbial communities, including methanotrophs (9). The PLFA method has low resolution and, therefore, cannot be used to identify individual species (38, 39). However, by combining PLFA with stable isotope probing (SIP), it is possible to identify the functional organisms that have utilized a particular substrate (9, 43), thereby enhancing the specificity of the method.

Identification of methanotrophs in soil is often performed by the cultivation-independent detection of a fragment of pmoA, a gene encoding a subunit of particulate methane monooxygenase (24, 27). The pmoA gene is present in all known methanotrophs except Methylocella spp. (13). Because sequence-based pmoA phylogeny correlates well with 16S rRNA gene-based phylogeny, it is considered an excellent marker and has been widely used to characterize methanotrophic communities in soils as well as to assign specific genera and species affiliations to methanotrophs (20, 23, 24, 33).

As the soil sink for atmospheric CH4 is microbially mediated, it is sensitive to environmental factors and disturbance by management (34). Different CH4 flux rates have been reported for a variety of land uses, soil types, and climatic conditions (3, 32, 40), suggesting that land use change can also influence CH4 uptake rates, with inhibition of CH4 oxidation being attributed to disturbance effects on methanotroph populations and activity. Most of these studies report a higher rate of CH4 oxidation in soils afforested from croplands or pastures (1, 29, 43). However, the mechanisms underlying these differences caused by afforestation are poorly understood. The change in CH4 uptake resulting from land use change is attributed to changes in soil porosity, moisture content, and the numbers of methanotrophs (32).

Here, we compare soil methanotrophic communities and their physiological capabilities in soils from two pine forests and a shrubland and from the three adjacent pastures using PLFA-SIP. Further, we used terminal-restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) and cloning and sequencing of the pmoA gene to characterize and identify the shifts in methanotroph communities due to afforestation on pastures. Our objectives were to examine whether the increase in CH4 uptake observed when pastures are afforested or reforested was due at least in part to changes in methanotrophic communities as revealed by biochemical and molecular methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sites and soil sampling.

Three independent sites in New Zealand were investigated for this study: Puruki and Westview, under Pinus radiata and pastures, and Waiouru, under shrubland and pasture. Soil characteristics measured for all soil samples are listed in Table 1. The Puruki site in the Purukohukohu Experimental Catchments is situated in central North Island at 38°36′S, 176°13′E. The soils are Oruanui sandy loams (Andisols) formed in ca. 1,800-year-old pumice. A detailed description of the Puruki site is given by Beets and Brownlie (2). Briefly, a fertilized, grazed (sheep and cattle) grass-clover pasture was developed in 1957. Plant species included Dactylus glomerate, Holcus lanatus, Lolium perenne, Anthoxanthum odoratum, Poa spp., and Trifolium repens (36). The first forest of P. radiata (pine) was planted in 1973 and harvested in April 1997. This site was replanted with P. radiata in September 1997.

TABLE 1.

Selected properties of different soils

| Sample | pH | Organic matter (%) | Water content (%) | Sand (%) | Silt (%) | Clay (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puruki pine | 4.6 | 21 | 42 | 70 | 27 | 2 |

| Puruki pasture | 4.7 | 27 | 50 | 71 | 27 | 2 |

| Westview pine | 4.9 | 12 | 39 | 53 | 40 | 6 |

| Westview pasture | 5.2 | 10 | 52 | 61 | 34 | 5 |

| Waiouru shrubland | 5.8 | 12 | 46 | 55 | 39 | 6 |

| Waiouru pasture | 6.0 | 10 | 45 | 60 | 35 | 5 |

The Westview site is located in the Pohangina Valley near Ashhurst, Manawatu (40°11′S, 175°49′E), and is used for sheep, beef, deer, and dairy farming with some forestry blocks. The soil is a poorly drained Halcombe hill soil formed from loess, sandstone, and greywacke gravels. The sampling areas selected were on a high terrace in a 14-year-old, first-rotation P. radiata stand and an adjacent pasture. The pasture comprised mainly L. perenne and T. repens, with some low-fertility grasses (e.g., Agrostis capillaris and Anthaxantham odoratum).

The Waiouru site, 70 km south of Lake Taupo (39°33′S, 175°41′E), comprised sheep and beef farming. The soil at the site is an Irirangi steepland soil (an Andisol). The reverting shrubland contained mainly ca. 50-year-old kanuka, Kunzea ericoides (A. Rich) J. Thompson, but also had a substantial grass cover, and it is used for shelter by grazing stock. The adjacent grazed pasture was dominated by Agrostis capillaris and H. lanatus.

At both the Puruki and Westview sites, we selected two locations of ca. 1 ha in each land cover type on north-facing (sunny) slopes, within which soil samples were collected. At Puruki, the locations (with a slope of ca. 10° and a northern aspect) under pine were about 200 m apart, whereas in the adjacent pasture, they were about 100 m apart. In the Westview pine plantation, soil samples were taken at one location under pine litter and another under a rank grass cover. Sampling in the Westview pasture was again from two locations about 100 m apart and ca. 200 m from the areas sampled under pine. At the Waiouru site, the sampling areas selected were on a northwestern slope, with only one location under shrubs and one under pasture being available. At the Waiouru site, three replicate areas about 20 m apart were selected under pasture and under shrubs. Three large cores (100-mm diameter, 0- to 100-mm depth) were taken for further analysis. Plant roots from soils were removed by hand before incubation.

Experimental procedures for methane oxidation by soils.

For oxidation of methane at ambient concentration, three replicate soil samples (10 g) from each site were placed separately in 1-liter seal-tight bottles in the dark at 20°C. Three sealed bottles without soils served as controls. Gas samples were collected in 5-ml gas-tight syringes at regular intervals to assess methane fluxes. Details of the gas analysis procedure have been described previously (18, 37). Briefly, evacuated Exetainers (6 ml) were overfilled with a 12-ml gas sample from the syringes to create a positive pressure in the Exetainer and then loaded on an automated gas analysis system (18). Methane concentration was measured by a gas chromatograph (GC) fitted with a flame ionization detector (Shimadzu-2010 gas chromatograph), and Shimadzu GC Solution version 2.21 SUI software was used to automatically integrate peak data, produce calibration curves, and calculate CH4 concentrations in each sample.

Analysis of active methanotrophs by PLFA-SIP.

Triplicate soil samples (10 g; 0- to 100-mm depth) from each site were transferred in 125-ml serum bottles. Bottles were then sealed with rubber stoppers compressed with an aluminum seal. After being sealed, each sample was injected with 13CH4 (>99 atom%; Novachem, Collingwood, Australia) through the rubber septum to achieve a concentration of 10 ppmv. Samples were incubated at 20°C in the dark for 13 days. Another set of samples was also incubated under the same conditions, except that they received 12CH4 and acted as controls. The CH4 concentration was measured at regular intervals. After 13 days, the soil samples were freeze-dried and finely ground, and 500 mg was used for extracting PLFAs (15, 16, 45).

Separation of individual PLFAs was achieved using a Thermo Finnigan Trace Ultra GC fitted with a J&W DB-5 capillary GC column (60-m by 0.25-mm inside diameter by 0.25-μm film thickness), using He as carrier gas. A 3-μl sample was injected, using splitless with surge injection (1 min splitless, 1 min surge at 103 kPa, and injector temperature at 150°C). The oven temperature was programmed to follow an isothermal hold at 100°C for 1 min, to 190°C at a rate of 20°C min−1, then to 235°C at a rate of 1.5°C min−1, and then to 295°C at a rate of 20°C min−1. This was followed by an isothermal hold for 10 min. The GC was interfaced to the continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (CF-IRMS; Deltaplus XP; Thermo Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) via an online combustion unit (GC Combustion III; Thermo Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an open split and a CO2 reference gas injection. Samples were then combusted and resultant compounds introduced to the IRMS via the open split. Separated compounds were measured against the CO2 reference gas of known isotopic composition. All δ13C values were corrected for the C added during the derivatization process for GC separation using a mass balance equation. We used the method of Holmes et al. (20) to calculate total isotope labeling in each PLFA fragment.

T-RFLP analysis of pmoA genes.

Total DNA was extracted from soils (0.5 g from each sample) using the UltraClean soil DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The extracted DNA was used for amplification of the pmoA gene. A nested PCR approach was implemented to amplify only the pmoA gene. In the first PCR, soil DNA was used as a template to amplify pmoA genes using primers pmoA-189F and pmoA-682R (19). This set of primers amplifies pmoA as well as some amoA (ammonia monooxygenase) genes. For the nested step, PCR products from the first round were used as templates for amplification in combination with the primer pair pmoA-189F and pmoA-650R (4), which exclusively amplify pmoA genes. For T-RFLP analysis, primer pmoA-189F used for the second round of amplification was labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) dye (all primers from Applied Biosystems, United Kingdom). The final PCR mix (50-μl final reaction volume) contained 5 μl of 10× NH4 reaction buffer, 2 μl of 50 μM MgCl2, 0.5 μl of 20 μM of deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.5 μl of Biotaq DNA polymerase (all reagents from Bioline, London, United Kingdom), 1 μl of 20 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, United Kingdom), and 38 μl of sterilized water. The 100 pmol of each primer was added in the reaction mix.

The PCR was performed on a DYAD DNA Engine Peltier thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA) using a program which consisted of 95°C for 5 min for denaturation, after which primers were added to each PCR tube. This was followed by 10 cycles of touchdown reaction, which consisted of 94°C for 60 s, an annealing step of 62 to 52°C for 60 s (start at 62°C and decrease by 1°C for every cycle), and 72°C for 60 s. This was followed by 20 cycles where the annealing temperature was maintained at 52°C for 60 s. For final extension, the reaction was held at 72°C for 10 min. To check the purity and size of PCR amplicons, 5 μl of each reaction mix was run on a 1% agarose gel (wt/vol). The PCR products were purified using a GeneElute PCR clean-up kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, United Kingdom) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Purified DNA was quantified using a Biophotometer (Eppendorf, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Aliquots of purified DNA (500 ng) were digested with HhaI. In a 20-μl reaction mix, the appropriate volume of DNA (for 500 ng) was mixed with 2 μl of HhaI enzyme, 2 μl of 10× buffer, and 0.2 μl of bovine serum albumin, and the volume was made up by the addition of sterile water. Samples were then digested for 3 hours at 37°C on a thermocycler, and the reaction was stopped by a further incubation at 95°C for 15 min. Aliquots (1 μl) of digested PCR products were mixed with 12 μl of formamide loading dyes (ABI, United Kingdom) and 1 μl of internal size standard (GS 500Liz; ABI) and then denatured for 5 min at 95°C. T-RFLP analysis was carried out on an automated sequencer, an ABI Prism 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom). Terminal restriction fragments (TRFs) generated by the sequencer were analyzed using GeneMapper 3.7 (ABI, United Kingdom). The relative abundance of TRFs in a T-RFLP profile was detected by peak height using the advance logarithm with a minimum peak area of 50 relative fluorescence units. Only peaks between 50 and 500 bp were considered to avoid TRFs caused by primer-dimers and to obtain fragments within the linear range of the internal size standard. The overall structure of methanotrophic communities among the different sites was analyzed by comparing profiles obtained from different samples.

Cloning and sequencing analysis of pmoA genes.

The PCR products for cloning and sequencing of pmoA genes were generated in the same way as detailed earlier for T-RFLP, except that no fluorescently labeled primer was used. In total, six separate clone libraries were obtained, one each for the individual site (two for pine forests, one for shrubland, and three for pastures). For each of the six samples, three replicates were pooled prior to cloning in order to minimize PCR bias and sample variation.

The pmoA gene amplicons obtained from selected samples were cloned in E. coli using a TOPO cloning kit (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom). About 50 clones were selected for each library. The correct insert size in each clone was checked by vector-targeted PCR (primers M13 F and M13 R) and gel electrophoresis. PCR amplicons were purified as described above. Sequencing was performed with the Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing reaction kit (ABI, United Kingdom) using vector-specific T3 and T7 primers on an automated DNA sequencer (ABI, United Kingdom). The quality of sequence was checked by the sequence analysis software (ABI), and products of forward (T3) and reverse (T7) primers were aligned using Kodon (Applied Maths, Saint-Martens-Latem, Belgium). Analyzed sequences were compared with prokaryotic genes using a FASTA-3 search of the EMBL database (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/fasta33). FASTA-3 and the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) were used to classify individual sequences into different groups, depending on the sequence similarity, using Kodon. For this purpose, two sequences that differed from each other by more than 2% were considered as a unique operational taxonomic unit (OTU) (46). All sequences were manually checked for chimeras, and the sequences with a split in alignment were removed from further analysis. Later, one sequence from each group was used for construction of a phylogenetic tree. The sequences were aligned using Bioedit (Ilbis Theraputics, Carlsband, CA), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using PAUP version 4* 0b10 by performing neighbor-joining tree analysis with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using the Juke-Cantor algorithm.

To match individual clones with a specific TRF, DNA from selected clones was separately amplified using 189F (FAM-labeled) and 650R primers as described above. PCR products were digested with HhaI, and TRFs were obtained as described above. TRF obtained from an individual clone was matched with TRFs obtained from soil samples.

Statistical analysis.

To investigate the difference in methane oxidation between different kinds of vegetation and at different sites, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out using GenStat version 8 (VSN International Ltd., Hempstead, United Kingdom). Principal coordinates (PCO) analysis with a Jaccard similarity matrix was used on binary data generated from T-RFLP profiles to obtain an ordination diagram. Further, we carried out ANOVAs on PCO scores for the first five dimensions to quantify the effect of site and vegetation on methanotrophic communities.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences for the pmoA genes have been deposited in EMBL under accession numbers AM712923 to AM713174.

RESULTS

Methane oxidation activity.

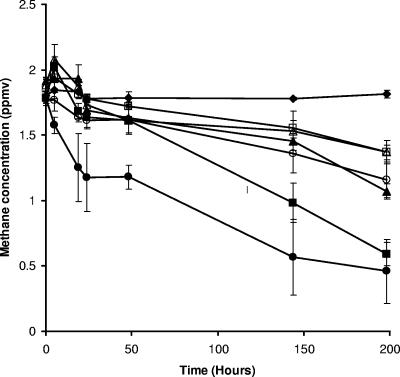

When soils were incubated at an ambient CH4 concentration, oxidation started immediately, but the rate of increase in oxidation was low initially. The most rapid oxidation was observed in soils from Waiouru shrubland and Puruki pine, which were significantly different from all other soil samples (P < 0.05). The CH4 oxidation rates of the Westview pine and Waiouru pasture soils were similar and higher than the rates for the Puruki and Westview pasture soils (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). Soils which were incubated with 10 ppm CH4 showed similar rates of oxidation, except that the difference between Westview pine and pasture soils was not apparent (data not shown). After 144 h of incubation, almost all methane was consumed in the Puruki pine soil and Waiouru shrubland and pasture samples. In the Westview pine and pasture soils, less than 40% and 30% methane, respectively, was oxidized.

FIG. 1.

Methane oxidation in different soil samples. The results are the means of three independent replicates, and error bars on each point represent the standard errors. Symbols: ⧫, control; ▪, soils from Puruki pine; □, soils from Puruki pasture; ▴, soils from Westview pine; ▵, soils from Westview pasture; •, soils from Waiouru shrub; ○, soils from Waiouru pasture.

PLFA-SIP analysis of methanotrophic communities.

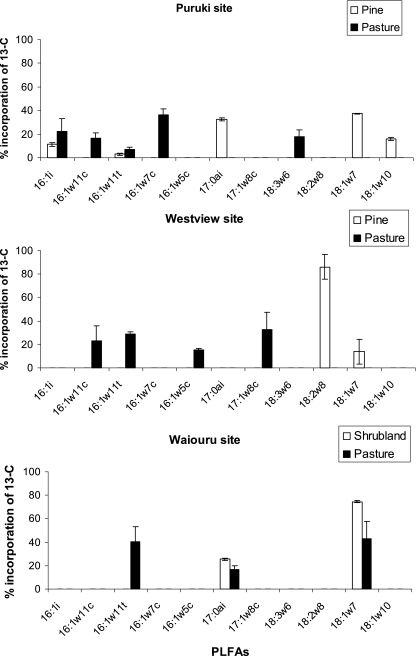

The PLFA analysis demonstrated the presence of a complete distribution, with saturated and mono- and polyunsaturated straight- and branched chain acids in each sample. The relative (% incorporation) δ13C value of individual PLFAs determined by GC-CF-IRMS for each site is presented in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Percentage incorporation of 13C into each PLFA extracted from Puruki, Westview, and Waiouru soils following incubation with 13CH4 (10 ppmv). Each bar represents PLFA which was enriched with 13C as a percentage of the total 13C in all fractions in each soil sample. The percentage incorporation between pasture and pine or shrubland soils in individual PLFA is distinguished by the color of the bar. Error bars represent standard errors obtained for three replicates.

The amount of δ13C labeling was higher in the Puruki pine than in the Puruki pasture soils. In Puruki pine soils, the most enriched PLFAs were 17:0ai, 18:1ω7, and 18:1ω10, whereas in the Puruki pasture soils, the most enriched PLFAs were 16:1ω7 and 16:1ω11c (Fig. 2). Minor labeling of some other PLFAs was also detected. Similar results were obtained for samples from the Westview sites, but δ13C enrichment of the PLFAs was lower than in the Puruki samples and did not differ significantly between the pine and pasture soils (data not shown). However, the δ13C labeling of particular PLFAs was different, with mainly C18 acids being labeled in the pine soil and C16 acids in the pasture soil (Fig. 2). A contrasting δ13C labeling was obtained for samples from the Waiouru site, where in the shrubland soils, labeling occurred only in 17:0ai and 18:1ω7, with no significant C16 PLFA enrichment. In the Waiouru pasture soil, by contrast, all three PLFAs from methanotrophs were enriched with δ13C (Fig. 2).

T-RFLP analysis of pmoA genes.

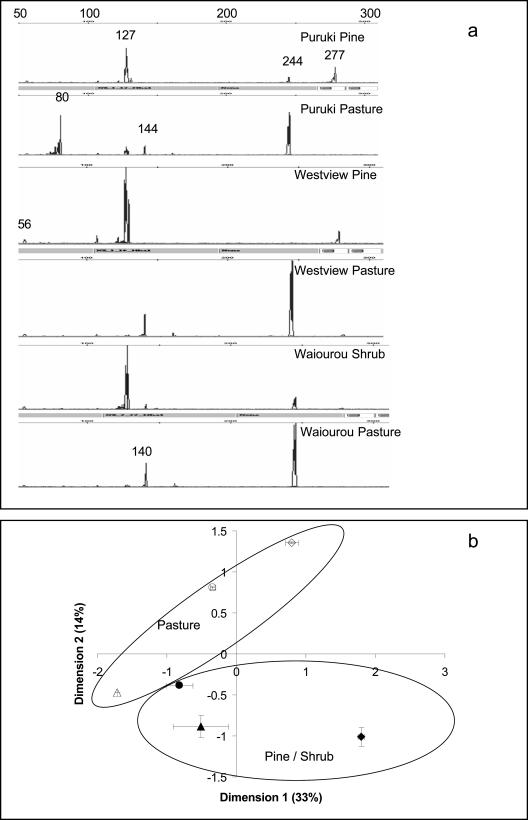

Most of the replicates produced similar T-RFLP profiles of methanotrophs, but there were marked differences between profiles from the pasture, pine, and shrubland sites (Fig. 3a). The two most dominant TRFs in most samples were of the 127- and 244-bp size, which were also responsible for the shift in methanotrophs in the pasture and pine soils. In general, a 127-bp TRF was most dominant in the pine soils, whereas a 244-bp TRF was dominant in the pasture soils. None of the Westview pasture samples had a 127-bp TRF, but it was dominant in the Westview pine soil (21.3%). A 127-bp TRF was less abundant in the Puruki pasture (29%) than in the pine (47%). However, this difference was not apparent in all replicates at the Waiouru site, where a 127-bp TRF was present at low abundance in all samples. A 244-bp TRF was present in almost all samples and was relatively more abundant in the Puruki pasture (20%) than in the Puruki pine (10%) samples. This difference was not as apparent in soils from the Westview site, although in one Westview pine replicate, no 244-bp TRF was present. Similarly, there was no significant difference in relative abundance of 244-bp TRFs between the Waiouru pasture and shrubland samples. The 140-bp TRF was present in almost all samples except those from the Puruki sites (pasture and pine), while the 277-bp TRF was present in all replicates of Puruki pine (relative abundance, 32%), and one replicate of the Westview pine (8%) soils. The 80-bp TRF was present only in the Puruki pasture soils (relative abundance, 32%). The 280-bp TRF was present only at the Waiouru site.

FIG. 3.

Effect of soil type or land use on T-RFLP profiles of methanotrophic communities. (a) Comparison of pmoA-based T-RFLP profiles obtained from Puruki, Westview, and Waiouru soils. The scale is marked with the size of TRFs in base pairs. The major TRFs are identified in base pair size. (b) Ordination diagram obtained from the principal-coordinate analysis of the presence and absence of the TRFs in different samples. Symbols: ⧫, Puruki pine; ⋄, Puruki pasture; ▴, Westview pine; ▵, Westview pasture; •, Waiorou shrubland; ○, Waiouru pasture.

The ordination diagram obtained from principal-coordinate analysis of the presence and absence of TRFs in each sample is presented in Fig. 3b to show the similarity of profiles from different vegetations. ANOVA on PCO scores for the first five dimensions suggested that dimension two was significantly influenced by the vegetation types (P = 0.002), while dimensions one and four were influenced by the site from which samples were collected (P = 0.001 and 0.04, respectively). PCO dimension three was influenced by both location and vegetation type (P = 0.003 and 0.007, respectively).

Cloning and sequencing of pmoA genes.

The Puruki pine soils showed the highest number of OTUs of the pmoA gene (n = 13), and Westview pasture soils had the lowest number of OTUs (n = 2). In general, the pine forest soils had a higher number and percentage of OTUs than the pasture soils. However, at the Waiouru sites, both pasture and shrub soils had the same number of OTUs (n = 5) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

OTUs in pmoA clone libraries

| Soil | Total no. of clones screened | No. of unique OTUs | % of unique OTUs in each library |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puruki pine | 40 | 13 | 32.5 |

| Puruki pasture | 41 | 5 | 12.2 |

| Westview pine | 48 | 13 | 27.1 |

| Westview pasture | 47 | 2 | 4.3 |

| Waiouru shrub | 35 | 5 | 14.3 |

| Waiouru pasture | 41 | 5 | 12.2 |

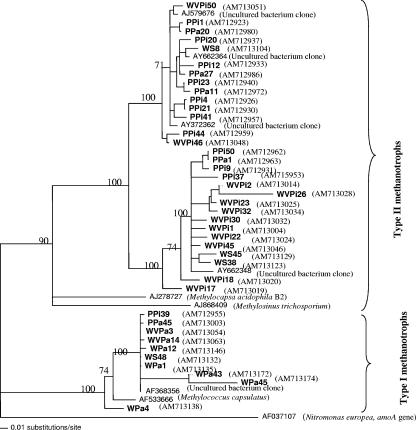

Individual sequences were searched against the EMBL and NCBI databases. Most of the sequences in the pine forest and shrubland soils were not similar to any cultured methanotrophs. However, they were very similar to a pmoA gene related to type II methanotrophs extracted from environmental samples (accession no. AY662348, AY662364, AY662365, AY372362, CT005232, and AJ579676). By contrast, clone analysis revealed that type I methanotrophs were dominant in all pasture soils. Sequences were further analyzed for phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 4). Most of the clones from the Puruki pine, Westview pine, and Waiouru shrubland samples cluster around uncultured bacteria distantly related to a Methylocapsa sp. (type II methanotrophs), while clones from all pasture samples cluster mainly around type I methanotrophs (Methylococcus capsulatus).

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of representative pmoA sequences retrieved from different soil samples (in bold) to pmoA sequences in the public domain. For this tree, one sequence from each OTU was aligned with selected sequences from the public database using Bioedit (Ilbis Theraputics, Carlsbad, CA). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using PAUP version 4* 0b10 by performing neighbor-joining tree analysis with 1,000 bootstrap replicates using the Jukes-Cantor algorithm. Bootstrap values (>50%) are indicated at the nodes of major branches. Sequences in the tree can be identified by sample name followed by clone number, where PPi is Puruki pine, PPa is Puruki pasture, WVPi is Westview pine, WVPa is Westview pasture, WS is Waiouru shrub, and WPa is Waiouru pasture.

A few randomly chosen clones from each sample were further PCR amplified and analyzed for TRF size to compare the relative abundance of pmoA clones in the clone libraries to their corresponding TRFs in the T-RFLP profile from soils. Most of the dominant TRFs from the soil T-RFLP profiles were accounted for by TRFs from the clone libraries. Results revealed that 127-bp TRFs originated mainly from uncultured soil type II methanotrophs (related to sequences with the accession no. AJ868264 and AY662360), a distant relative of a Methylocapsa sp., while 244-bp TRFs originated mainly from type I methanotrophs (related to Methylococcus capsulatus). The 56-bp TRF originated from a bacterium closely related to an uncultured methanotroph (accession no. AJ579676). Other TRFs which were detected in clones were 140-, 144-, and 277-bp TRFs, which originated from the pmoA most similar to that of M. capsulatus and were distantly related to pmoA from uncultured type II methanotrophs (accession no. AY662365) and M. capsulatus, respectively. Further, we used the REMA program (www.macaulay.ac.uk/rema) to predict the TRF size from all clones obtained for this study by simulated digestion with HhaI (41). The result was in complete agreement with the TRF size obtained from the actual T-RFLP profiles of selected clones. Only TRF 160 was not detected in clone libraries by either approach.

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of our study was to investigate the biological factors responsible for enhanced soil CH4 oxidation observed with afforestation or reforestation of pastures in New Zealand (42, 44). Soil microbial communities are susceptible to change with vegetation type driven mainly by changes in the carbon source (rhizodeposition, leaf and litter decomposition, etc.) (38). In our study, we used PLFA-SIP to examine the active methanotrophs in soil samples from sites under pastures, pine, and native shrubland. Consistent with our studies on these soils using ambient CH4 concentrations, all pasture soils showed lower CH4 oxidation rates than soils from adjacent sites afforested or reforested with pine or native shrubland. These results generally confirmed previous studies on the impact of land use change on CH4 oxidation (8, 12, 40, 43).

The amount of 13C labeling was much higher in the Puruki pine than the Puruki pasture soils and is consistent with the pattern for net CH4 uptake. This suggested CH4 oxidation was mediated by very active methanotrophs in the Puruki pine samples. This observation was confirmed by the soil incubation study, in which most of the added 13CH4 (10 μl liter−1) was utilized within 6 days. By contrast, about 50% of the added 13CH4 remained after incubating the Puruki pasture soil for 13 days. The CH4 oxidation in the Westview soils was slow compared to the other sites and, consequently, samples from this site had the lowest 13C labeling in the PLFAs. Nonetheless, relatively higher CH4 oxidation was again observed in the pine than in the pasture soils at this site.

PLFA analysis has been successfully used to characterize different methanotrophs, based on the presence of specific signature fatty acids (5, 9). PLFAs consisting of C14 and C16 fatty acids are dominant in type I methanotrophs, and PLFAs with C18 fatty acids dominate in type II methanotrophs. Some type I and II methanotrophs can produce 16:1ω8c and 18:1ω8c (35). In the Puruki pine soils, the PLFA most highly enriched with 13C was 18:1ω7, which is the principal fatty acid of Methylocapsa acidiphila and Methylocella spp., both type II methanotrophs (11, 24). However, 17:0ai was also highly labeled in this soil, and this has been linked to unknown methanotrophic bacteria (6, 9). By contrast, the PLFAs in the Puruki pasture soil were most highly labeled in 16:1ω7 and 16:1ω11c, which are representative of type I methanotrophs (5). The comparatively low methanotrophic activity of the Westview soil samples was reflected in the low 13C labeling of their PLFAs. Nonetheless, higher 13C enrichment of C18 PLFAs in the pine soil and of C16 PLFAs in the pasture soil again suggests that different microbial communities were responsible for CH4 oxidation under these two vegetation types. The results for the Waiouru soil were in contrast, whereas in the shrubland soils, only 17:0ai and 18:1ω7 were significantly labeled with 13C, but in the pasture soils, all three main PLFAs (including C16) were enriched. This suggests that type II and unknown methanotrophs were active in the shrubland, while CH4 oxidation activity was distributed between type I, type II, and unknown methanotrophs in the pastures. This different pattern from the other sites might be, in part, due to the presence of a good grass cover. Some recent studies (14, 25) have shown that type II methanotrophs are generally involved in atmospheric CH4 oxidation, while type I methanotrophs are less oligotrophic and utilize CH4 produced in soil with mixing ratios of more that 100 ppmv. Animal treading effects combined with abundant grass roots would favor more anaerobic microsites in soil where CH4 production can occur, and this could help to explain our results.

Overall, our results for the soils from three sites suggest that type II methanotrophs are dominant in pine and shrubland soils and exhibit the highest CH4 oxidation capacity. These results are consistent with evidence that consumption of atmospheric CH4 in native forests is controlled primarily by type II methanotrophs (14). Furthermore, type I methanotrophs have been suggested to be dominant in aquatic environments (17). This may explain the shift in methanotroph communities from pasture to pine and shrubland sites. It is well known that soil moisture content is often higher in grassland than in adjacent forests (29, 43, 44).

The PLFA-SIP results obtained in this study are mostly consistent with cloning and sequencing data obtained for pmoA genes from different soils. In our pasture soils, type I methanotrophs were dominant, while in the pine soils, clones from the uncultivable bacteria of type II methanotrophs, distantly related to the pmoA from Methylocapsa and Methylosinus, were dominant. However, results for the Waiouru site differed slightly from those for the other sites. The clone libraries suggested that only type I methanotrophs were present in the pasture soil at this site, while 25% of the clones from the shrubland soil were type II methanotrophs. However, the PLFA data suggest that type II and unknown methanotrophs were dominant in the shrubland soil, while the pasture soils had an even distribution of type I and II methanotrophs. There may be several explanations for these apparent anomalies. First, it may be possible that both type I and type II methanotrophs were present in the shrubland soil, with the most active being type II, which were detected by the PLFA-SIP. Another explanation is a bias in the PCR, with cloning resulting in preferential amplification of type II methanotrophs (although this is unlikely; Murrell et al., unpublished observation). Last, we may not have been able to pick one of the most active groups of methanotrophs at this site (belonging to 17:0ai PLFA), which is considered not identifiable at present by any currently available methods (6, 9). Nonetheless, cloning and sequencing and further phylogenetic analysis of pmoA genes from all samples have indicated that the type I methanotrophs dominate in the pasture soils, while uncultured bacteria from type II methanotrophs dominate in the pine soils. In the Waiouru shrub soil, low numbers of type II methanotrophs compared to those in the Puruki and Westview pine soils (although higher than in the Waiouru pasture soil) may be attributed to the extensive grass understory and the effects of cattle accessing the shrub site for shelter. Similarly, there were minor discrepancies between T-RFLP and cloning and sequencing data in terms of relative abundances of methanotrophs in the different soils. Data from these two methods for the Puruki and Westview soils were similar and comparable. However, at the Waiouru site, the T-RFLP data showed that the relative abundances of 244- and 127-bp TRFs did not differ between the pasture and shrub soils, but the cloning and sequencing data revealed that 25% of the methanotroph population was of type II in the shrub soil but was completely absent in the pasture soil. Such discrepancies between these methods are well documented for 16S rRNA genes (7, 21) and the pmoA genes (22, 31). There is currently no simple explanation for this variation. This may be due to PCR or cloning bias or to an error in the correlation of TRFs. Nonetheless, all three methods have confirmed that type II methanotrophs are the most dominant and active methane oxidizers in the pine and shrub soils, while type I methanotrophs dominate the activity and populations in all the pasture soils.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department and the Macaulay Development Trust (for B.K.S., G.K., and P.M.), the New Zealand Foundation for Research, Science and Technology (for K.R.T. and C.B.H.), and the National Environmental Research Council (for J.C.M.; grant NERC/A/S/2002/00876) for funding.

We are thankful to Shane Connell and Nicola Shadbolt (Pohangina Valley, Manawatu) and Peter Beets (Scion, Rotorua) for access to the Westview and Puruki sites. Hugh Wilde (Landcare Research, Palmerston North) arranged access and provided soil information for the Waiouru site. We also thank Des Ross (Landcare, NZ) and Rebekka Artz (MI) for critically reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 15 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ball, B. C., I. P McTaggart, and C. A. Watson. 2002. Influence of organic ley-arable management and afforestation in sandy loam to clay loam soils on fluxes of N2O and CH4 in Scotland. Agric. Ecosys. Environ. 90:305-317. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beets, P. N., and R. K. Brownlie. 1987. Puruki experimental catchment: site, climate, forest management and research. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 17:137-160. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borken, W., and F. Beese. 2006. Methane and nitrous oxide fluxes of soils in pure and mixed stands of European beech and Norway spruce. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 57:617-625. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourne, D. G., I. R. McDonald, and J. C. Murrell. 2001. Comparison of pmoA PCR primer sets as tools for investigating methanotroph diversity in three Danish soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3802-3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman, J. P., L. I. Sly, P. D. Nichols, and A. C. Hayward. 1993. Revised taxonomy of the methanotrophs: description of Methylobacter gen. nov. emendation of Methylococcus, validation of Methylosinus and Methylocystis species, and a proposal that the family Methylococcaceae includes only the group-I methanotrophs. Intl. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:735-753. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bull, I. D., N. R. Parekh, G. H. Hall, P. Ineson, and R. P. Evershed. 2000. Detection and classification of atmospheric methane oxidising bacteria in soil. Nature 405:175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin, K. J., T. Lukow, and R. Conrad. 1999. Effect of temperature on structure and function of the methanogenic archaeal community in an anoxic rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2341-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crill, P. M., P. J. Martikainen, H. Nykanen, and J. Silvola. 1994. Temperature and N-fertilization on methane oxidation in a drained peatland soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 26:1331-1339. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crossman, Z. M., P. Ineson, and E. R. Evershed. 2005. The use of C-13 labelling of bacterial lipids in the characterisation of ambient methane-oxiding bacteria in soils. Org. Geochem. 36:769-778. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crutzen, P. J. 1991. Atmospheric chemistry: methane sinks and sources. Nature 350:380-381. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dedysh, S. N., V. N. Khmelenina, N. E. Suzina, Y. A. Trotsenko, J. D. Semrau, W. Liesack, and J. M. Tiedje. 2002. Methylocapsa acidiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel methane-oxidizing and dinitrogen-fixing acidophilic bacterium from Sphagnum bog. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunfield, P., and R. Knowles. 1995. Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in a humisol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3129-3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunfield, P. F., V. N. Khmelenina, N. E. Suzina, Y. A. Trotsenko, and S. N. Dedysh. 2003. Methylocella silvestris sp. nov., a novel methanotroph isolated from an acidic forest cambisol. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:1231-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunfield, P. F., W. Liesack, T. Henckel, R. Knowles, and R. Conrad. 1999. High-affinity methane oxidation by a soil enrichment culture containing a type II methanotroph. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1009-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frostegård, Å., A. Tunlid, and E. Bååth. 1991. Microbial biomass measured as total lipid phosphate in soils of different organic content. J. Microbiol. Methods 14:151-163. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frostegård, Å., E. Bååth, and A. Tunlid. 1993. Shifts in the structure of soil microbial communities in limed forests as revealed by phospholipid fatty acid analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 25:723-730. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson, R. S., and T. E. Hanson. 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60:439-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedley, C. B., S. Saggar, and K. R. Tate. 2006. Procedure for fast simultaneous analysis of the greenhouse gases: nitrous oxide, methane and carbon dioxide, in air samples. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 37:1501-1510. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes, A. J., N. J. P. Owens, and J. C. Murrell. 1995. Detection of novel marine methanotrophs using phylogenetic and functional gene probes after methane enrichment. Microbiology 141:1947-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmes, A. J., P. Roslev, I. R. McDonald, N. Iverson, K. Henrikson, and J. C. Murrell. 1999. Characterization of methanotrophic bacterial populations in soils showing atmospheric methane uptake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3312-3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horz, H. P., M. T. Yimga, and W. Liesack. 2001. Detection of methanotroph diversity on roots of submerged rice plants by molecular retrieval of pmoA, mmoX, mxaF, and 16S rRNA and ribosomal DNA, including pmoA-based terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profiling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4177-4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horz, H. P., V. Rich, S. Avrahami, and B. J. M. Bohannan. 2005. Methane-oxidizing bacteria in a California upland grassland soil: diversity and response to simulated global change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2642-2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen, S., A. J. Holmes, R. A. Olsen, and J. C. Murrell. 2000. Detection of methane oxidizing bacteria in forest soil by monooxygenase PCR amplification. Microb. Ecol. 39:282-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knief, C., A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2003. Diversity and activity of methanotrophic bacteria in different upland soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6703-6714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knief, C., S. Kolb, P. L. E. Bodelier, A. Lipski, and P. F. Dunfield. 2006. The active methanotrophic community in hydromorphic soils changes in response to changing methane concentration. Environ. Microbiol. 8:321-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe, D. C. 2006. A green source of surprise. Nature 439:146-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonald, I. R., and J. C. Murrell. 1997. The particulate methane monooxygenase gene pmoA and its use as a functional gene probe for methanotrophs. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 156:205-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menyailo, O. V., and B. A. Hungate. 2003. Interactive effects of tree species and soil moisture on methane consumption. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35:625-628. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merino, A., P. Perez-Batallon, and F. Macias. 2004. Responses of soil organic matter and greenhouse gas fluxes to soil management and land use changes in a humid temperate region of southern Europe. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36:917-925. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ojima, D. S., D. W. Valentine, A. R. Mosier, W. J. Parton, and D. S. Schimel. 1993. Effect of land-use change on methane oxidation in temperate forest and grassland soils. Chemosphere 26:675-685. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pester, M., M. W. Friedrich, B. Schink, and A. Brune. 2004. pmoA-based analysis of methanotrophs in a littoral lake sediment reveals a diverse and stable community in a dynamic environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3138-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Priemé, A., S. Christensen, K. E. Dobbie, and K. A. Smith. 1997. Slow increase in rate of methane oxidation in soils with time, following land-use change from arable agriculture to woodland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 29:1269-1273. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reay, D. S., S. Radajewski, J. C. Murrell, N. McNamara, and D. B. Nedwell. 2001. Effects of land-use on the activity and diversity of methane oxidizing bacteria in forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33:1613-1623. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeburg, W. S., S. C. Whalen, and M. J. Alperin. 1993. The role of methanotrophy in the global methane budget, p. 1-14. In J. C. Murrell and D. P. Kelly (ed.), Microbial growth on C1 compounds. Intercept Ltd., Andover, United Kingdom.

- 35.Roslev, P., and N. Iversen. 1999. Radioactive fingerprinting of microorganisms that oxidize atmospheric methane in different soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4064-4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross, D. J., K. R. Tate, N. A. Scott, and C. W. Feltham. 1999. Land-use change effects on soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus pools and fluxes in three adjacent ecosystems. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31:803-813. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saggar, S., K. R. Tate, C. Hedley, and A. Carran. 2004. Methane emissions from cattle dung and methane consumption in New Zealand grazed pastures, p. 52-56. Proceedings of the Trace Gas Workshop, Wellington, New Zealand.

- 38.Singh, B. K., P. Millard, A. Whiteley, and J. C. Murrell. 2004. Unravelling rhizosphere-microbial interactions: opportunities and limitations. Trends Microbiol. 12:386-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh, B. K., S. Munro, E. Reid, B. Ord, J. M. Potts, E. Paterson, and P. Millard. 2006. Investigating microbial community structure in soils by physiological, biochemical and molecular fingerprinting methods. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 57:72-82. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith, K. A., K. E. Dobbie, B. C. Ball, L. R. Bakken, B. K. Sitaula, S. Hansen, R. Brumme, W. Borken, S. Christensen, A. Priemé, and D. Fowler. 2000. Oxidation of atmospheric methane in Northern European soils, comparison with other ecosystems, and uncertainties in the global terrestrial sink. Global Change Biol. 6:791-803. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szubert, J., C. Reiff, A. Thorburn, and B. K. Singh. 2007. REMA: a computer-based mapping tool for analysis of restriction sites in multiple DNA sequence. J. Microbiol. Methods 69:411-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tate, K. R., D. J. Ross, N. A. Scott, N. J. Rodda, J. A. Townsend, and G. C. Arnold. 2006. Post-harvest patterns of carbon dioxide production, methane uptake and nitrous oxide production in a Pinus radiata D. Don plantation. For. Ecol. Manag. 228:40-50. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tate, K. R., D. J. Ross, S. Saggar, C. B. Hedley, J. Dando, B. K. Singh, and S. Lambie. 2007. Methane uptake in soils from Pinus radiata plantations, a reverting shrubland and adjacent pastures: effects of land-use change, and soil texture, water and mineral nitrogen. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39:1437-1439. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tate, K. R., N. A. Scott, D. J. Ross, A. Parshotam, and J. J. Claydon. 2000. Plant effects on soil carbon storage and turnover in a montane beech (Nothofagus) forest and adjacent tussock grassland in New Zealand. Austral. J. Soil Res. 38:685-698. [Google Scholar]

- 45.White, D. C., W. M. Davis, J. S. Nickels, J. D., King, and R. J. Bobbie. 1979. Determination of the sedimentary microbial biomass by extractable lipid phosphate. Oecologia 40:51-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yan, T., J. Zhou, and C. L. Zhang. 2006. Diversity of functional genes for methanotrophs in sediments associated with gas hydrates and hydrocarbon seeps in the Gulf of Mexico. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 57:251-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]