Abstract

Burkholderia strains are promising candidates for biotechnological applications. Unfortunately, most of these strains belong to species of the Burkholderia cepacia complex (Bcc) involved in human infections, hampering potential applications. Novel diazotrophic Burkholderia species, phylogenetically distant from the Bcc species, have been discovered recently, but their environmental distribution and relevant features for agro-biotechnological applications are little known. In this work, the occurrence of N2-fixing Burkholderia species in the rhizospheres and rhizoplanes of tomato plants field grown in Mexico was assessed. The results revealed a high level of diversity of diazotrophic Burkholderia species, including B. unamae, B. xenovorans, B. tropica, and two other unknown species, one of them phylogenetically closely related to B. kururiensis. These N2-fixing Burkholderia species exhibited activities involved in bioremediation, plant growth promotion, or biological control in vitro. Remarkably, B. unamae and B. kururiensis grew with aromatic compounds (phenol and benzene) as carbon sources, and the presence of aromatic oxygenase genes was confirmed in both species. The rhizospheric and endophyte nature of B. unamae and its ability to degrade aromatic compounds suggest that it could be used in rhizoremediation and for improvement of phytoremediation. B. kururiensis and other Burkholderia sp. strains grew with toluene. B. unamae and B. xenovorans exhibited ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid) deaminase activity, and the occurrence of acdS genes encoding ACC deaminase was confirmed. Mineral phosphate solubilization through organic acid production appears to be the mechanism used by most diazotrophic Burkholderia species, but in B. tropica, there presumably exists an additional unknown mechanism. Most of the diazotrophic Burkholderia species produced hydroxamate-type siderophores. Certainly, the N2-fixing Burkholderia species associated with plants have great potential for agro-biotechnological applications.

It is well known that hundreds of thousands of bacterial species remain to be discovered and cultured, representing a substantial reservoir of genetic diversity and great potential for biotechnological applications. Although most of the bacteria inhabiting common environments (e.g., agricultural soils and plants) have not yet been grown in culture, many of them could be cultivated using standard methods. However, for many environments, research on microbial taxonomy and ecology is lacking. Unfortunately, novel bacterial species are often described based on the analysis of a very limited set of isolates (59), commonly one to three. This is true for many bacterial species, including several belonging to the genus Burkholderia. For example, the species B. kururiensis (80), B. sacchari (9), B. phenoliruptrix (16), B. terrae (79), B. tuberum, and B. phymatum (73) were recently described on the basis of a single isolate analyzed, and consequently, their environmental distribution and ecological role are unknown. B. kururiensis and B. sacchari were described as species with abilities to degrade trichloroethylene and to biotechnologically produce polyhydroxyalkanoic acids, respectively, but new studies related to their ecologies or applications are largely lacking. The nitrogen-fixing species B. xenovorans was described on the basis of three isolates (32); strain LB400T was isolated from polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)-contaminated soil in Moreau, NY, strain CAC-124 was isolated from the rhizosphere of a coffee plant cultivated in Veracruz, Mexico, and strain CCUG 28445 was recovered from a blood culture in Sweden. Although strain LB400T is the best-studied PCB degrader, and its pathways for degradation of these compounds have been extensively characterized at the genetic and molecular levels (25, 35), strains CAC-124 and CCUG 28445 have been only partially analyzed and do not share the biphenyl-biodegrading capacities of strain LB400T (32). Recently, one B. xenovorans isolate was recovered from the rhizosphere of maize cultivated in The Netherlands (62). Although the complete genome of B. xenovorans LB400T was recently sequenced (12), it is noteworthy that the four extant B. xenovorans strains described in diverse studies have been randomly recovered from different environments and widely distant geographical regions, and there are no studies on the distribution of this PCB-degrading, nitrogen-fixing species or its association with plants. Emphasis has been given to studies of the isolation, taxonomy, and distribution of Burkholderia species related to human opportunistic pathogens, especially the B. cepacia complex species found in cystic fibrosis patients (33, 45, 52; for reviews, see references 15 and 42). In contrast, few studies have been performed on the overall diversity of the genus Burkholderia (61, 63), even though nonpathogenic Burkholderia species are frequently recovered from different environments (6, 40, 70), and despite their biotechnological potential in bioremediation and other applications (34, 70; for a review, see reference 48). Knowledge of novel diazotrophic Burkholderia species (11, 32, 50, 54), including legume nodule symbionts (14, 73), phylogenetically greatly distant from the B. cepacia complex species, has come very recently, but their environmental distribution and relevant features for agronomic and environmental applications are little known (13, 27, 32, 49).

Bacteria are involved in degradation processes of many aromatic compounds released into the environment by the decay of plant material or by anthropogenic activity. Phenolic compounds and polymers containing benzene rings (e.g., lignins) are natural aromatic compounds (21, 29). However, phenol is a man-made aromatic compound and along with its derivatives is considered a major hazardous compound in industrial wastewater. Similarly, aromatic hydrocarbons like benzene and toluene are common pollutants of soil and groundwater (78). Soil microorganisms are capable of using aromatic compounds as sole carbon sources, owing to aerobic biodegradation catalyzed by mono- or dioxygenases (3, 78). In the last few years, rhizoremediation (microbial degradation of hazardous compounds in the rhizosphere) and phytoremediation (the use of plants to extract and degrade harmful substances) have been considered alternatives for decontamination of soils. In addition, bacteria are able to exert positive effects on plants through various mechanisms. For instance, nitrogen fixation (the natural transformation of atmospheric N2 to ammonia) contributes organic nitrogen for plant growth (28), while the bacterial enzyme 1-amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase hydrolyzes ACC (the immediate precursor of ethylene) and lowers the levels of ethylene produced in developing or stressed plants, promoting root elongation (30). Some bacteria solubilize insoluble minerals through the production of acids, increasing the availability of phosphorus and other nutrients to plants in deficient soils (55). Several bacteria improve plant growth through suppression of pathogens by competing for nutrients, by antibiosis, or by synthesizing siderophores, which can solubilize and chelate iron from the soil and inhibit the growth of phytopathogenic microorganisms (23).

This work was aimed at revealing the occurrence of nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species associated with tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants cultivated in different locations in Mexico. We found that the rhizosphere of tomato is a reservoir of different known and unknown diazotrophic Burkholderia species that are able to exhibit in vitro some activities involved in bioremediation, plant growth promotion, and biological control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crop and locations.

Saladet variety tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants were collected in Atlatlahuacan and Tetecala (two collections from different farms), Morelos, and Nepantla and Santa Inés, State of Mexico, Mexico (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Diazotrophic Burkholderia species isolated from the rhizospheres of Saladet variety tomato plants cultivated in different geographical regions of Mexico

| Locality | Species | Strain | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coatlán del Río, Morelos | B. xenovorans | TCo-26 | Rhizoplane |

| Coatlán del Río, Morelos | B. xenovorans | TCo-213 | Rhizosphere |

| Coatlán del Río, Morelos | B. xenovorans | TCo-39 | Rhizosphere |

| Coatlán del Río, Morelos | B. xenovorans | TCo-382 | Rhizosphere |

| Atlatlahuacan, Morelos | B. unamae | TAtl-371 | Rhizosphere |

| Atlatlahuacan, Morelos | B. unamae | TAtl-3711 | Rhizoplane |

| Atlatlahuacan, Morelos | B. unamae | TAtl-3742 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | B. unamae | TNe-832 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | B. unamae | TNe-873 | Rhizosphere |

| Santa Inés, State of Mexico | B. unamae | TSi-883 | Rhizosphere |

| Tetecala, Morelos | B. unamae | TTe-829 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | B. tropica | TNe-865 | Rhizoplane |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | B. tropica | TNe-831 | Rhizosphere |

| Santa Inés, State of Mexico | B. tropica | TSi-882 | Rhizoplane |

| Santa Inés, State of Mexico | B. tropica | TSi-887 | Rhizoplane |

| Santa Inés, State of Mexico | B. tropica | TSi-888 | Rhizoplane |

| Tetecala, Morelos | B. tropica | TTe-791 | Rhizosphere |

| Tetecala, Morelos | B. tropica | TTe-797 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. (Bkr) | TNe-834 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. (Bkr) | TNe-841 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. (Bkr) | TNe-8641 | Rhizoplane |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. (Bkr) | TNe-8682 | Rhizosphere |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. (Bkr) | TNe-878 | Rhizoplane |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. | TNe-861 | Rhizoplane |

| Nepantla, State of Mexico | Burkholderia sp. | TNe-862 | Rhizoplane |

Tomato plant samples.

Eight to 10 complete flowering plants, field grown 20 m apart in each region, were randomly collected. Care was taken to keep the rhizosphere intact around the root. Samples of the rhizospheres and rhizoplanes (root surfaces) of the tomato plants were analyzed for recovery of the N2-fixing isolates 4 to 5 hours after collection.

Media, culture conditions, and diazotrophic Burkholderia isolation.

Rhizosphere and plant samples were treated as described previously (27). Purified colonies were assayed for nitrogenase activity by the acetylene reduction activity (ARA) method (10) with vials containing 5 ml of N-free semisolid Burkholderia malate-glucose-mannitol (BMGM) medium (27). ARA-positive colonies were maintained in 20% glycerol at −80°C prior to characterization.

Total DNA isolation and 16S rRNA-specific primers.

Genomic DNA was isolated from bacterial cells by using published protocols (2). ARA-positive isolates were presumptively assigned to the genera Burkholderia and Ralstonia by amplifying the 16S rRNA gene with the specific primers BuRa-16-1 and BuRa-16-2, using PCR conditions described previously (5). In addition, a new specific primer pair was designed in order to get a PCR-amplified product larger than the 409-bp amplicon obtained with primers BuRa-16-1/BuRa-16-2. Burkholderia-Ralstonia 16S rRNA genes were amplified using the PCR primer GB-F (5′-AGTAATACATCGGAACRTGT-3′), described previously (49), and a primer named GB-R (5′-GGSTTGGCRACCCTCTGTT-3′), designed in the present study. The specificity of the GB-F/GB-R primer pair was tested with most (31 out of 40) of the well-known Burkholderia species as well as with Ralstonia pickettii and Ralstonia solanacearum strains. The PCR mixtures contained 20 ng of genomic DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, a 250 μM concentration of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5 pmol of each primer, and 1.0 U of Taq polymerase. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation for 30 s at 94°C, annealing for 45 s at 58°C, and elongation for 1 min at 72°C, followed by a final 5-min elongation at 72°C. The reaction amplified a 1,100-bp fragment.

ARA-positive isolates were confirmed as belonging to the genus Burkholderia by amplifying the 16S rRNA genes with the GB-F/GBN2-R-specific primer pair, using PCR conditions described previously (49).

ARDRA.

Primers fD1 and rD1 were used for amplifying the 16S rRNA gene (77), using PCR conditions described previously (27). The PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes (ca. 1.5 kb) were restricted with seven enzymes (AluI, DdeI, HaeIII, HhaI, HinfI, MspI, and RsaI), and the restriction fragments were separated as described previously (27). The restriction patterns were compared, and each isolate was assigned to an amplified 16S rRNA gene restriction analysis (ARDRA) genotype, defined by the combination of the restriction patterns obtained with the seven restriction endonucleases (27). Similarities among the 16S rRNA gene sequences were estimated from the proportions of shared restriction fragments by using the method of Nei and Li (47). A dendrogram was constructed from the resulting distance matrix by using the unweighted pair group method with averages (67).

16S rRNA gene sequencing and phylogenetic analysis.

Representative acetylene-reducing strains corresponding to each ARDRA genotype identified among isolates recovered from tomato plants were chosen for 16S rRNA gene sequencing. To obtain 16S rRNA sequences, PCR products were cloned as described previously (49), and the 16S rRNA gene sequences were determined at the Biotechnology Institute, UNAM (Mexico). The 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited in the EMBL/GenBank database. These sequences were compared with previously published 16S rRNA gene sequences from Burkholderia species and related bacteria, such as Ralstonia and Pandorea. The multiple alignments of the sequences were performed with CLUSTAL W software (69). The tree topology was inferred by the neighbor-joining method (60), based on 1,310 DNA sites, and distance matrix analyses were performed according to Jukes and Cantor (38), using the program MEGA version 2.1 (41).

SDS-PAGE of whole-cell proteins.

Preparation of whole-cell proteins from diazotrophic isolates and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) assays were performed as described previously (27).

PCR amplification of nifH genes.

Primers IGK (51) and NDR-1 (71) were used for the amplification of the nifH genes, using PCR conditions described previously (49). The reaction amplified a 1.2-kb fragment comprising the entire nifH gene, the intergenic spacer region, and the 5′ end of the nifD gene (71).

Growth on aromatic compounds.

Nitrogen-free semisolid BAz mineral medium (composition in grams/liter: azelaic acid, 2.0; K2HPO4, 0.4; KH2PO4, 0.4; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.2; CaCl2, 0.02; Na2MoO4·H2O, 0.002; FeCl3, 0.01; bromothymol blue, 0.075), usually used for enrichment of nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species (11, 27, 49, 54), was modified for testing bacterial growth on aromatic compounds. The mineral medium was supplemented with ammonium sulfate (0.05%), the azelaic acid was omitted, and aromatic compounds were included as sole carbon sources; this medium was named SAAC (salts-ammonium-aromatic compound). For growth in agar (1.8% [wt/vol]) plates, 150-μl volumes of the volatile aromatic compounds benzene, isopropylbenzene (cumene), and toluene were independently added on filter paper circles (6-cm diameters) placed in the lids of petri dishes, which were sealed with polyethylene tape and incubated upside down within closed polypropylene containers at 29°C. Naphthalene and biphenyl were tested similarly, but using 50 mg of crystals. Phenol (0.05%) was directly added to the SAAC mineral medium. SAAC medium without a carbon source was used as a negative control for bacterial growth; succinic acid (0.2%) as a carbon source was a positive control. The isolates were grown in BSE liquid medium (27) for 18 h at 29°C with reciprocal shaking (250 rpm). The cultures were harvested and the pellets washed with 10 mM MgSO4·7H2O and adjusted to an optical density (OD) of 0.25 at 600 nm (approximately 2 × 108 cells per ml). Aliquots of the cultures were inoculated with a multipoint replicator on SAAC medium plates containing the aromatic compounds described above and incubated for 4 to 10 days.

PCR amplification and sequencing of aromatic oxygenase genes.

All of the isolates that were capable of growing with aromatic compounds as sole carbon sources, as well as type and reference strains of well-known diazotrophic Burkholderia species, were analyzed for the presence of di- and monooxygenase genes. Toluene/biphenyl dioxygenase genes were PCR amplified with the bphAf668-3/bphAr1153-2 primers, using conditions described previously (78). Primers RDEG-F/RDEG-R and RMO-F/RMO-R were used for amplification of the sequences of the large subunits of toluene monooxygenases and primers PHE-F/PHE-R for amplification of phenol monooxygenases, using the PCR conditions described by Baldwin et al. (3). The reactions amplify a 466-bp fragment with both the RDEG and the RMO primer pairs and a 206-bp product with the PHE primer pair. PCR products from one or two strains from each species were cloned into the pCR2.1 vector according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen), and the aromatic oxygenase gene sequences were determined at the Biotechnology Institute, UNAM (Mexico). These gene sequences were deposited in the EMBL/GenBank database and compared with previously published sequences.

PCR amplification of acdS (encoding ACC deaminase) genes.

Putative ACC deaminase gene sequences annotated (NCBI GenBank database) in the complete genomes of B. xenovorans LB400T (accession number NC_007952), B. vietnamiensis G4 (NZ_AAEH00000000), Burkholderia sp. strain 383 (NC_007511), B. mallei ATCC 23344 (NC_006349), B. pseudomallei K96243 (NC_006351), and Pseudomonas sp. strain ACP (M73488) were aligned, and primers with minimal degeneracies (5′ACC [5′ACGCCGATCCARCCGCTM3′] and 3′ACC [5′TCCAGCGTGCCSTCGTTC3′]) were designed for PCR amplification of acdS genes. The PCR mixture was composed of 20 ng of genomic DNA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 25 μM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 5 pmol of each primer, and 1.0 U of Taq polymerase. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation for 5 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation for 45 s at 95°C, annealing for 45 s at 67°C, and elongation for 1 min at 72°C, followed by a final 5-min elongation at 72°C. The reaction amplified a 785-bp fragment.

ACC deaminase activity assay.

The isolates were grown in BSE liquid medium (27) for 18 h at 29°C with reciprocal shaking (250 rpm). The cultures were harvested and the pellets washed twice with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The pellets were resuspended in 20 ml salts medium (composition in grams/liter: succinic acid, 2.0; K2HPO4, 1.0; KH2PO4, 1.0; MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5; CaCl2, 0.13; FeSO4, 0.013) supplemented with either 3.0 mM ACC or 3.0 mM NH4Cl, pH, 5.7, and then the cultures were grown as described above. The cells were collected and the pellets washed twice with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) before being resuspended in 1 ml 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) (65) and ruptured using a French press at 900 lb/in2. Crude extracts were harvested by centrifugation, and the ACC deaminase activity was measured by following the production of α- ketobutyrate as described by Honma and Shimomura (37). Total protein content in extracts was determined using the method described by Bradford (8).

Phosphate solubilization.

Isolates were tested using NBRIP medium agar plates containing insoluble tricalcium phosphate [Ca3(PO4)2] as the sole phosphorous source (46). Phosphate solubilization assays were carried out with NBRIP medium strongly buffered with MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) buffer (4.4 g/liter) and on unbuffered medium. The isolates were grown in iron-restricted Casamino Acids (CAA) liquid medium (44) supplemented with succinic acid (3 g/liter) for 18 h at 29°C. The cultures were harvested and the pellets washed with 10 mM MgSO4·7H2O and adjusted to an OD of 0.25 at 600 nm. Aliquots of the cultures were inoculated on NBRIP agar plates with a multipoint replicator. The solubilization haloes around colonies and colony diameters were measured after 3, 5, and 7 days of incubation at 29°C. Halo size was determined by subtracting the colony diameter from the total diameter.

Siderophore production.

The method used to detect siderophores was adapted from the universal chemical assay on chrome azurol S (CAS) agar plates (64). The time-consuming and laborious deferrization process of solutions was omitted, and piperazine was not added; MM9 growth medium was replaced by CAA medium supplemented with succinic acid (3 g/liter). The isolates were grown in CAA liquid medium for 18 h at 29°C with reciprocal shaking (250 rpm). The cultures were harvested and the pellets washed and adjusted to an OD of 0.25 as described for the phosphate solubilization assays. Aliquots of the cultures were inoculated with a multipoint replicator on modified CAS medium (CAS-CAA) and then incubated for 72 h at 29°C. Orange haloes that formed around the colonies on blue agar were considered indicative of siderophore production. Halo size was determined by subtracting the colony diameter from the total diameter. Similarly, the isolates were grown in CAA liquid medium and hydroxamate-type siderophores were identified using the Czàky test (19), after hydrolysis with 3 N sulfuric acid at 120°C for 30 min (53), and buffered with 3 ml of 35% sodium acetate (19). Catechol-type siderophores were identified using the Arnow test (1).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited in the EMBL/GenBank database under accession numbers EF139178, EF139179, EF139180, and EF139181 for B. unamae strains TNe-873, TATl-3742, TSi-883, and TATl-371, respectively; the accession numbers for B. tropica strains TNe-865 and TSi-887 were EF139182 and EF139183, respectively; Burkholderia sp. strains TNe-862, TNe-878, and TNe-841 were deposited under accession numbers EF139184, EF139185, and EF139186, respectively; and the accession numbers for B. xenovorans strains TCo-382 and TCo-26 were EF139187 and EF139188, respectively. The phenol hydroxylase (aromatic oxygenase) gene sequences were deposited in the EMBL/GenBank database under accession numbers EF151008, EF151009, EF151010, and EF158449 for Burkholderia sp. strain TNe-862, B. unamae strains TSi-883 and MTI-641T, and “B. brasilensis” M130, respectively. Toluene-3-monoxygenase gene sequences were deposited under accession numbers EF151011, EF151012, and EF151013 for “B. brasilensis” M130, B. kururiensis KP23T, and Burkholderia sp. strain TNe-862, respectively. The acdS gene sequences were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers EF408192 and EF408193 for B. xenovorans strains TCo-26 and TCo-382, respectively, and EF408194 for B. unamae TAtl-3742.

RESULTS

Isolation.

Enrichment cultures for N2-fixing Burkholderia were made in N-free semisolid BAz medium, followed by further isolation and colony purification on BAc agar plates (27). Screening of 420 colonies allowed the recovery of a total of 54 isolates that showed consistent nitrogenase activity as measured by the ARA method. Although it is possible that a few isolates did not show ARA, due to suboptimal growth conditions or loss of plasmids, ARA-negative colonies were discarded, and no attempt was made to determine their taxonomic positions.

16S rRNA-specific primers.

ARA-positive isolates gave PCR-amplified products of the correct size (409 bp) with primers BuRa-16-1/BuRa-16-2, confirming their taxonomic statuses as members of the genera Burkholderia-Ralstonia. In addition, use of the specific primer pair GB-F/GB-R (designed in the present study to get a PCR-amplified product of around 1,100 bp) confirmed that the ARA-positive isolates belong to the genera Burkholderia-Ralstonia. The specificity of the GB-F/GB-R primer pair was confirmed with all of the 31 type strains of the known Burkholderia species tested and of Ralstonia pickettii and Ralstonia solanacearum (data not shown). All of the 54 ARA-positive isolates were confirmed as belonging to the genus Burkholderia by amplifying the 16S rRNA genes with the GB-F/GBN2-R specific primer pair, described previously (49).

ARDRA.

A total of eight ARDRA profiles were identified from among the 54 acetylene-reducing Burkholderia isolates recovered from the rhizosphere and rhizoplane of tomato (data not shown). One ARDRA profile identified among 11 acetylene-reducing isolates (e.g., TCo-26 and TCo-382) differed slightly from the profile of B. xenovorans LMG 16224. Three ARDRA genotypes identified among 11 isolates were identical to genotypes 16 (1 isolate), 17 (3 isolates), and 19 (7 isolates), described previously as belonging to the species B. tropica (54). Two ARDRA genotypes (14 isolates) were slightly different from that of strain MTl-641T and from other genotypes of B. unamae described previously (11). One ARDRA profile similar to that of B. kururiensis KP23T was identified among 12 ARA-positive isolates (e.g., TNe-841 and TNe-878), hereafter referred to in the text as B. kururiensis-resembling (Bkr) group or Bkr-type isolates. One ARDRA profile (six isolates) was different from those ARDRA profiles observed in other known diazotrophic Burkholderia species, hereafter referred to in the text as Burkholderia sp.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences.

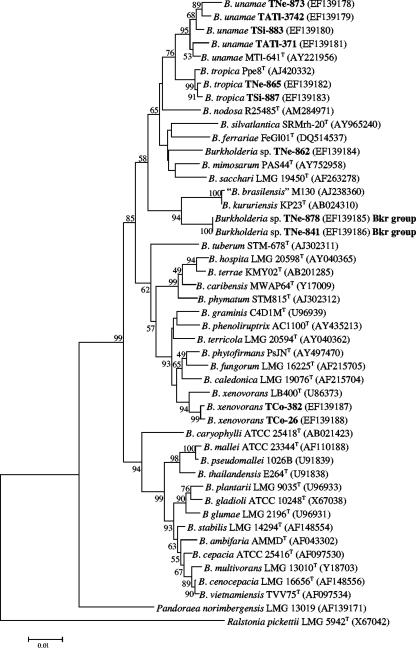

The 16S rRNA genes from one to four acetylene-reducing strains of each ARDRA genotype identified among the isolates recovered from tomato plants cultivated on different farms were sequenced and then compared with available 16S rRNA sequences from all of the Burkholderia species. Analysis of the 16S rRNA genes from strains TCo-26 and TCo-382 showed 98 to 99% identity with strain LB400T of B. xenovorans (NCBI sequence database accession number U86373; P. C. K. Lau and H. Bergeron, unpublished; CP000271 chromosome 2 and CP000270 chromosome 1, complete sequence), which strongly suggested that they belong to this species (Fig. 1). Similarly, 16S rRNA gene sequences from strains TSi-873, TNe-883, TAtl-371, and TAtl-3742, all having ARDRA profiles slightly different from that of B. unamae MTl-641T, showed 98 to 99% identity with this and other strains of B. unamae (e.g., NCBI accession numbers AY221955, AY221956, and AY221957) (11), and isolates TNe-865 and TSi-887 showed 99% identity with B. tropica strains (e.g., accession numbers AJ420332, AY128103, AY321306, AY128105, and AY128104) (54). Likewise, 16S rRNA gene sequences from strains TNe-841 and TNe-878 (Bkr group) showed 97.9% identity with B. kururiensis KP23T (accession number AB024310) (80) and 97.8% identity with “B. brasilensis” M130 (accession number AJ238360) (unpublished), which is a species not officially validated but referred to in the relevant literature (17, 39, 57, 58, 61). According to 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the strain TNe-862 showed 98% identity with Burkholderia sp. legume-nodulating strains mpa3.2 and mpa2.1a (accession numbers DQ156081 and DQ156080, respectively) and 97% identity with type strain SRMrh-20T of B. silvatlantica (accession number AY965240) (50).

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relatedness among the nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species associated with tomato plants (strain designations in bold) and related Burkholderia species. The bar represents one nucleotide substitution per 100 nucleotides. The nodal robustness of the tree was assessed using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The NCBI GenBank accession number for each strain is shown in parentheses.

SDS-PAGE of whole-cell proteins.

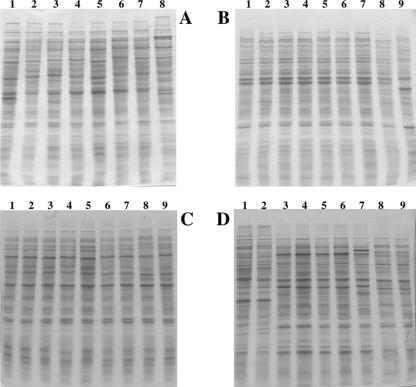

Whole-cell protein extracts were prepared from 25 representative acetylene-reducing Burkholderia isolates (recovered from diverse tomato plants and farms) showing different ARDRA profiles and their protein profiles compared with those from type and reference strains of Burkholderia species that showed identical or very similar ARDRA profiles. The protein patterns of some representative strains are shown in Fig. 2. In general, the similarity in whole-cell protein profiles between isolates recovered in this study and those profiles from type or reference strains of a particular diazotrophic Burkholderia species is striking (for example, B. xenovorans LMG 16224 and strains TCo-382 and TCo-213 [Fig. 2A], isolated in this work). Similar results were observed among B. unamae MTl-641T as well as B. tropica Ppe8T and strains recovered from the environment of tomato plants (Fig. 2B and C). It is remarkable that B. kururiensis KP23T and “B. brasilensis” M130 show almost identical protein profiles (Fig. 2D). In contrast, Bkr isolates (those with ARDRA profiles similar to that of B. kururiensis KP23T) showed major differences between their protein patterns and KP23T profiles. Similarly, strains TNe-862 and TNe-861 (Table 1) showed significant differences in their SDS-PAGE profiles from those of the phylogenetically closest species, Burkholderia sp. strain mpa2.1a and B. silvatlantica strains (data not shown). Bkr isolates as well as strains TNe-862 and TNe-861 appear to represent two novel diazotrophic Burkholderia species.

FIG. 2.

Whole-cell protein profiles of representative acetylene-reducing isolates recovered in the present study, type and reference strains of known diazotrophic Burkholderia species, and other closely related species. (A) Lanes 1 to 7, B. xenovorans LB400T, CAC-124, LMG 16224 (type and reference strains) (32), TCo-26, TCo-39, TCo-382, and TCo-213; lane 8, B. caledonica LMG19076T. (B) Lanes 1 to 8, B. unamae TSi-883, MTl-641T, CGC-321 (reference strain) (11), TAtl-3742, TTe-829, TNe-873, TAtl-3711, and TNe-832; lane 9, B. sacchari IPT101T. (C) Lanes 1 to 9, B. tropica TSi-888, TSj-882, Ppe8T, TSi-887, TTe-797, TTe-791, MTo-672 (reference strain) (54), TNe-865, and TNe-831. (D) Lane 1, “B. brasilensis” M130; lane 2, B. kururiensis KP23T; lanes 3 to 7, Burkholderia sp. (Bkr group) strains TNe-8641, TNe-8682, TNe-878, TNe-841, and TNe-834; lanes 8 and 9, Burkholderia sp. strains TNe-862 and TNe-861.

PCR amplification of nifH genes.

Twenty-five representative acetylene-reducing Burkholderia isolates were analyzed (Table 1), yielding a PCR product of the expected size of 1.2 kb (data not shown) with the nifH primers used. These results confirmed the nitrogen-fixing abilities of the Burkholderia isolates.

Growth with aromatic compounds.

The abilities of the diazotrophic Burkholderia species to grow on aromatic compounds as carbon sources were variable and dependent on each species (Table 2). B. xenovorans strains recovered from tomato plants (Table 2) and reference strains CAC-124 and CCUG 28445 (data not shown) were unable to grow with aromatic compounds; type strain LB400T grew with biphenyl as expected but not with any other aromatic compound tested. Interestingly, all of the B. unamae isolates recovered from tomato plants, except strains TAtl-3711 and TAtl-3742, were able to grow with benzene and phenol but not with biphenyl or other aromatic compounds tested (Table 2), and this feature was confirmed for seven other B. unamae strains, including the type strain, isolated from different plants and locations described previously (11). All of the B. tropica isolates recovered from tomato plants and seven other strains of this species isolated from different plants cultivated in widely distant regions (54) were unable to grow with any aromatic compound. While Bkr isolates were able to grow only with benzene as a carbon source, B. kururiensis KP23T and “B. brasilensis” M130 grew on toluene and phenol (Table 2). Burkholderia sp. strains TNe-862 and TNe-861 grew on toluene, phenol, and benzene (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Growth with aromatic compounds as carbon sources and PCR amplification of genes encoding aromatic oxygenases in N2-fixing Burkholderia species associated with tomato plantsa

| Species or strain (n) | Presence (+) or absence (-)b of:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth with aromatic compound:

|

PCR amplification of genes encoding:

|

||||||||

| Toluene | Phenol | Cumene | Benzene | Biphenyl | Naphthalene | Aromatic monooxygenase

|

Aromatic dioxygenase (biphenyl) | ||

| Toluene | Phenol | ||||||||

| B. unamae (5) | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| B. unamae (7)c | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| B. xenovorans (4) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. xenovorans LB400T | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Bkr group (4) | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. kururiensis KP23T | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| “B. brasilensis” M130 | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| B. tropica (7) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| B. tropica (7)c | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Burkholderia sp. (2) | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − |

PCR amplification of the toluene monooxygenase gene was obtained with primers RMO-F/RMO-R but not with primers RDEG-F/RDEG-R.

+, good growth or gene presence; -, no growth or gene absence.

Includes type and reference strains.

PCR amplification and sequencing of aromatic oxygenase genes.

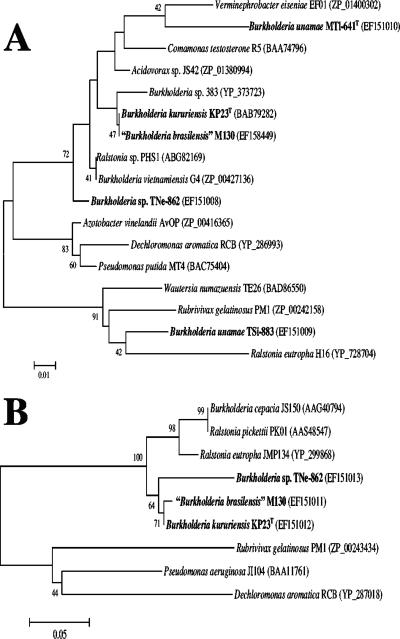

None of the nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia isolates associated with tomato plants (Table 1), including the B. xenovorans strains, yielded a PCR-amplified product with the bphAf668-3/bphAr1153-2 primers, used to amply toluene/biphenyl dioxygenase genes (Table 2), while these primers gave PCR products of the correct sizes (525 to 531 bp) with B. xenovorans LB400T as described previously (78). Diazotrophic Burkholderia strains that were able to grow using phenol or toluene as a carbon source yielded PCR products of the expected sizes with the specific primer pair used to amplify the corresponding aromatic oxygenase gene (Table 2). Subsequent gene sequencing and BLASTN analysis with available sequences deposited at the NCBI database confirmed the presence of phenol hydroxylases in B. unamae strains MTl-641T and TSi-883, B. kururiensis KP23T, “B. brasilensis” M130, and Burkholderia sp. strain TNe-862 as well as the presence of toluene-3-monooxygenases in B. kururiensis KP23T, “B. brasilensis” M130, and Burkholderia sp. strain TNe-862. Phylogenetic trees derived from aromatic oxygenase-related sequences are illustrated in Fig. 3A and B. Although several replicates were done with different clones, the phenol hydroxylase gene fragments (203 bp) from B. unamae strains MTl-641T and TSi-883 (associated with tomato) were, surprisingly but very interestingly, widely dissimilar. In contrast, the phenol hydroxylase gene fragments of B. kururiensis KP23T and “B. brasilensis” M130 analyzed in this work as well as the phenol hydroxylase gene sequence from B. kururiensis KP23T reported previously (81) were almost identical. B. kururiensis KP23T and “B. brasilensis” M130 differed very slightly (99.34% identity) between their toluene-3-monooxygenase gene sequences, and these were closely related to the sequence from Burkholderia sp. strain TNe-862 (associated with tomato), and all of these toluene-3-monooxygenase sequences were more closely related to B. cepacia as well as Ralstonia eutropha and R. pickettii than to other toluene-degrading bacterial species.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on aromatic oxygenases showing the relatedness among the diazotrophic Burkholderia species associated with tomato plants (strain designations in bold) and degrader species of volatile aromatic compounds. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of phenol hydroxylase amino acid sequences; the analysis included 67 sites. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of toluene-3-monoxygenase amino acid sequences; the analysis included 153 sites. Bootstrapping analysis was used to test the statistical reliability of tree branch points. One thousand bootstrap samplings were performed. The NCBI GenBank accession number for each strain is indicated in parentheses.

PCR amplification and sequencing of acdS genes and ACC deaminase activity.

Each of the B. unamae and B. xenovorans isolates analyzed (Table 1) yielded a 785-bp DNA fragment (data not shown) by use of the specific primer pair 5′ACC/3′ACC (designed in the present study). Gene sequencing and BLASTN analysis confirmed the presence of acdS genes in representative B. unamae and B. xenovorans strains associated with tomato plants. ACC deaminase activity levels were 22.93 (standard deviation [SD] = 01.68) and 25.42 (SD = 0.30) μM α-ketobutyrate/h/mg protein in B. unamae strains TAtl-3742 and TSi-883, respectively, and 24.91 (SD = 0.73) μM α-ketobutyrate in B. xenovorans TCo-26. All of these data clearly support the presence of the ACC deaminase enzyme and its expression in the B. unamae and B. xenovorans species.

Phosphate solubilization.

Phosphate solubilization ability was variable among the diazotrophic Burkholderia species associated with tomato plants (Table 3). B. tropica exhibited the most notable phosphate-dissolving capability, showing the largest halo diameter in medium with Ca3(PO4)2 as the sole P source in either the absence or the presence of MES buffer after incubation for 72 h. Although B. unamae TATl-371 exhibited a small solubilization halo (2 mm) in the presence of MES buffer, all of the other isolates of this species as well as Bkr and Burkholderia sp. isolates were able to dissolve insoluble phosphates only in the absence of MES buffer after incubation for 3 to 5 days. B. xenovorans isolates were unable to dissolve tricalcium phosphate, except for strain CAC-124, which showed a small solubilization halo of 2 mm, but only in the absence of MES buffer.

TABLE 3.

Phosphate solubilization and biosynthesis of siderophores by N2-fixing Burkholderia species associated with tomato plants

| Species or strain (n) | Halo size (mm)a on NBRI medium for Ca3(PO4)2 solubilization

|

Value for siderophore production

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without MES buffer

|

With MES buffer

|

Halo size (mm)a on CAS medium | Hydroxamate concn (μM)b | |||

| 3 days | 7 days | 3 days | 7 days | |||

| B. tropica (6) | 7.1 | 9.5 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 14.2 | 0.23-1.10 |

| B. tropica (3)d | 7.3 | 9.7 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 14.0 | 0.38-0.42 |

| B. unamae (6) | 0.0 | 2.3c | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.5c | 3.04-8.31 |

| B. unamae (3)d | 1.3 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 3.11-6.29 |

| B. xenovorans (4) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.8 | 4.70-5.91 |

| B. xenovorans LB400T | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 19.5 |

| Bkr group (5) | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.33-1.63 |

| B. kururiensis KP23T | 0.0 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 |

| Burkholderia sp. (2) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.33-0.70 |

Values represent the average halo sizes formed by the strains tested and are means for two replicate cultures.

Siderophore production range by the strains tested.

Halo sizes produced by B. unamae TAtl-371 were not included in the average, as this strain was exceptional in siderophore production and phosphate solubilization with respect to all of the strains of this species.

Includes type and reference strains tested.

Siderophore production.

All of the diazotrophic Burkholderia isolates associated with tomato plants were able to produce siderophores on CAS medium agar plates (Table 3). In this medium, B. unamae isolates formed orange haloes (indicative of siderophore production) with diameters ranging from 5 to 8 mm, except for strain TAtl-371, which produced the largest diameter halo (22 mm) among all of the diazotrophic Burkholderia strains tested. Generally, B. xenovorans strains produced the largest halo sizes (13 to 19 mm), followed by B. tropica strains (12 to 17 mm), the Bkr group (2 to 14 mm), and Burkholderia sp. isolates (3 mm). Except for the Burkholderia sp. isolates, all of these diazotrophic Burkholderia species produced hydroxamate-type siderophores (Table 3), but none produced catechol-type siderophores under the assay conditions used (data not shown). Generally, halo size was not correlated with amount of hydroxamate determined in liquid culture (Table 3). However, B. unamae TAtl-371 produced the largest amount of hydroxamate (8.3 μM) among all of the isolates recovered from the tomato environment, which otherwise produced hydroxamates in concentrations less than 5 μM (Table 3). Interestingly, B. xenovorans strains LB400T, CCUG 28445, and CAC-124, included as controls in different assays, produced hydroxamates in concentrations as high as 19.5, 16, and 7.8 μM, respectively.

DISCUSSION

A total of 54 isolates recovered from the rhizospheres and rhizoplanes of tomato plants showed consistent nitrogenase activity as measured by the ARA method, and the presence of nifH genes was detected in all of the isolates (data not shown), confirming their diazotrophic abilities. The taxonomic statuses of all these isolates as members of the genera Burkholderia and Ralstonia were confirmed with two specific primer sets, BuRa-16-1/BuRa-16-2 (described previously [5]) and GB-F/GB-R (designed in the present study). All 54 of the diazotrophic isolates were confirmed as belonging to the genus Burkholderia by amplifying the 16S rRNA genes with the GB-F/GBN2-R-specific primer pair, described previously (49). A total of eight ARDRA profiles were identified from among the 54 diazotrophic Burkholderia isolates, and on this basis, only 25 representative N2-fixing isolates of each ARDRA genotype identified among isolates recovered from tomato plants cultivated on different farms were further analyzed. Based on 16S rRNA sequences and whole-cell protein profiles, which provide strong evidence for the delineation of bacterial species (74), B. xenovorans, B. unamae, and B. tropica species were identified. In addition, two other unknown nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species were cultured in the present study, one of them closely phylogenetically related to B. kururiensis and the other one to legume-nodulating strains and to B. silvatlantica.

It is worth noting the substantial ability of the bacterial species to colonize different environments, including taxonomically distinct plants cultivated in distantly separated geographical regions. For example, B. xenovorans strains TCo-213 and TCo-382 were recovered from the rhizosphere of tomato in the present work, and strains CAC-124 and LMG 16224 were isolated from the rhizosphere of a coffee plant in Mexico and from a blood culture in Sweden, respectively (32). Similarly, in the present study B. tropica was found associated with tomato plants, but it has been isolated from sugarcane and maize varieties in Brazil, South Africa, and Mexico (49, 54). Recently, based on the 16S rRNA sequence, one isolate recovered from within dune grass (Ammophila arenaria) showed 99% identity with B. tropica strains (20). Although B. unamae has been found predominantly associated with sugarcane in Mexico (49), its isolation from sugarcane varieties cultivated in Brazil and South Africa (NCBI GenBank database accession number AY391282) (49) as well as from other crop plants, including maize and coffee (11), has been documented. Although 16S rRNA gene sequences from Bkr isolates associated with tomato plants showed high identity levels (97%) with B. kururiensis KP23T and “B. brasilensis” M130, the protein patterns visualized in the Bkr isolates were clearly different from those observed in strains KP23T and M130, which strengthens the notion that Bkr isolates do not belong to the species B. kururiensis or “B. brasilensis.” However, it is remarkable that B. kururiensis KP23T and “B. brasilensis” M130 show almost identical protein profiles. Previously, it was suggested that strains KP23T of B. kururiensis and “B. brasilensis” M130 belong to the same species, since both strains were able to fix N2 in similar manners, showed the same ARDRA profile, and had identity levels of 99.9% between their 16S rRNA sequences (27). In addition, strains KP23T and M130 differ at a single gene locus of 12 enzyme gene loci (multilocus genotypes) tested in multilocus enzyme electrophoresis assays (data not shown) and display other very similar features, such as the ability to grow using phenol and toluene as single carbon sources, with the corresponding gene sequences (phenol hydroxylase and toluene-3-monooxygenase) being almost identical. High identity levels between glnB or nifH genes in both strains were observed previously (43). On the basis of these data, strain M130 should be considered a member of the species B. kururiensis, and we recommend that reference to the species “Burkholderia brasilensis” be omitted in future literature to avoid further confusion. Nonetheless, the wide geographic distribution and substantial ability of B. kururiensis to colonize such dissimilar environments is striking; while the trichloroethylene-degrading strain KP23T was isolated from an aquifer polluted with trichloroethylene in Japan (80), strain M130 was recovered from surface-sterilized roots of rice grown in Brazil (76). Based on these findings, it appears conceivable to find new host plants or other unexpected habitats for B. unamae or B. kururiensis and other well-known or unknown species, as observed with B. xenovorans and Burkholderia spp. recovered in the present study.

In this work, N2-fixing Burkholderia isolates associated with tomato plants were assessed for their abilities to grow with some common volatile pollutant compounds as sole carbon sources. Very interestingly, all of the B. unamae isolates associated with tomato plants were able to grow with benzene and phenol as sole carbon sources, and the ability to grow on phenol was confirmed with the detection and sequencing of phenol monooxygenase genes by PCR. This feature was confirmed to be characteristic of this species as well as for seven other B. unamae strains, including type strain MTl-641, associated with different plants cultivated in widely distant regions (11). However, complete sequences of phenol monooxygenase genes from B. unamae strains MTl-641T and TSi-883 should be obtained to determine the divergence between them, as these sequences differed greatly in the small (203-bp) DNA fragments analyzed. In addition, the complete phenol monooxygenase genes of more B. unamae strains should be analyzed to determine their evolutionary origins in populations of this species. These dissimilarities strongly contrast with the 100% identity found between phenol monooxygenase genes from B. kururiensis KP23T and M130 isolated from two widely separated regions of the world. No less remarkable is the finding that B. tropica (54), B. sacchari (9), and B. ferrariae (72), all closely phylogenetically related to B. unamae, were unable to grow with the aromatic compounds benzene and phenol (data not shown). Nevertheless, very recently one B. tropica strain able to degrade benzene, toluene, and xylene was described (22), but this strain was identified only on the basis of PCR amplification and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes, which may be insufficient evidence to define its exact taxonomic position, considering that B. tropica and B. unamae show identity levels higher than 98% between their 16S rRNA gene sequences (11). Moreover, this B. tropica strain was identified (31) before B. unamae was described (11) and their 16S rRNA gene sequences could be compared. If the taxonomic status of the B. tropica strain is confirmed by means of polyphasic taxonomy criteria, then considering the inabilities of several B. tropica strains tested in this study to grow on aromatic compounds, this would indicate a case of lateral gene transfer, as has been suggested for the biphenyl pathway for PCB degradation expressed by B. xenovorans LB400T but absent in two other strains of this species (12, 32). In the present study, such a lateral gene transfer in LB400T is supported by the finding that the B. xenovorans isolates (e.g., TCo-26 and TCo-382) associated with tomato plants were incapable of growing with biphenyl as the sole carbon source, and biphenyl dioxygenase genes were not PCR amplified from these strains, though this occurred, as expected, in strain LB400T. Undoubtedly, more B. xenovorans isolates should be analyzed to confirm that the ability to degrade biphenyl and other aromatic compounds is a typical characteristic in this species and not a unique feature of strain LB400T. Considering the habitat of B. xenovorans (soil and rhizosphere), the ability to degrade aromatic compounds originating from root exudates and root turnover could be important (12). Similarly, since about 25% of the Earth's biomass consists of compounds having a benzene ring as the main structural component (29), and phenolic compounds are widely distributed in the plant kingdom (21), the ability of B. unamae to use benzene and phenol as carbon sources could be advantageous for its survival in the rhizospheric and endophyte environments, both common habitats of this species (11). Unfortunately, in this study we did not analyze the endophyte environment of tomato for recovering diazotrophic Burkholderia species. However, the ability of B. unamae to grow using aromatic hydrocarbons, as well as its widespread association with different plant species (11, 49), suggests that it could be suitable for applications in rhizosphere remediation of common soil pollutants. In addition, taking into consideration the host plant range of B. unamae and its endophytic character, it would be of great interest to know the natural ability of this species to improve phytoremediation of volatile organic pollutants, as has been suggested with the application of engineered endophytic bacteria (4, 68).

In the present work, several bacterial plant growth-promoting mechanisms were analyzed and detected in diazotrophic Burkholderia isolates associated with tomato plants. In previous studies, ACC deaminase activity was proposed as a bacterial mechanism that may enhance plant growth by lowering plant ethylene levels (30), which is especially true in stressed dicots such as tomato, since monocots are less sensitive to ethylene (36). Based on these data, and supported by the occurrence of acdS genes (PCR amplified using a primer pair designed in this study and verified by sequencing) in B. unamae and B. xenovorans as well as by the corresponding ACC deaminase activities expressed by strains of these species associated with tomato plants, it could be suggested that both B. unamae and B. xenovorans possess the potential for improving plant growth. In fact, maize inoculation with wild-type strains of B. unamae promotes maize plant growth (unpublished results), and experiments using different mutants to determine the mechanism of plant growth promotion are in progress. Conversely, although ACC activity has been detected in B. tropica strain BM-273, and the corresponding acdS gene was detected in this strain and in strain BM-16 (7), we were unable either to detect ACC activity or to amplify the acdS gene in any of the B. tropica strains analyzed. This discrepancy could be attributed to the different sets of primers used for amplification in both studies. However, based on acdS phylogenetic analysis, an extensive horizontal transfer of acdS genes has been suggested, which could explain the occurrence of this gene in strains BM-273 and BM-16 (both isolated from maize plants inoculated with soil from the same field [26]) but not in B. tropica strains associated with tomato plants or in seven other strains of this species recovered from plants cultivated in different locations (54). These discrepancies deserve further analysis, which was beyond the scope of this study.

In the present work, the highest mineral phosphate-dissolving capability was detected in B. tropica isolates; this capability was lower in B. unamae and Burkholderia sp. isolates and null in most B. xenovorans strains. Even though mineral phosphate-dissolving capability in most bacteria has been related to organic acid production (55), recent results indicate that this is not the only mechanism of mineral phosphate solubilization by bacteria (56). Mineral phosphate solubilization through organic acid production appears to occur in most diazotrophic Burkholderia species associated with tomato plants, but in B. tropica, an additional, unknown mechanism presumably exists, since this species solubilized tricalcium phosphate in less than 72 h even in a strongly buffered culture medium. Regardless of the mechanism used by B. tropica, its remarkable ability to convert insoluble mineral phosphorus to an available form is an important trait for allowing this diazotrophic species to be defined as a plant growth-promoting rhizobacterium. Seed inoculation with efficient phosphate-solubilizing bacteria is known to increase solubilization of fixed soil phosphorus and immobilized phosphates in the soil after application of mineral fertilizers, resulting in higher crop yields (23, 56).

Production of siderophores by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria is considered to be important in the suppression of deleterious microorganisms and soilborne plant pathogens (66) and in some cases appears to trigger induced systemic resistance (18, 75). The production of hydroxamate-type siderophores by B. unamae and B. tropica strains has been described previously (11, 54) and confirmed in the present work as a characteristic feature in these species. B. xenovorans strain LB400T is widely known as an effective PCB degrader, but the synthesis of hydroxamate-type siderophores in large amounts by this species is described for the first time in this work. In accordance with this finding, homologs of biosynthesis genes encoding two hydroxamate-type siderophores, pyoverdine and ornibactin, were found on chromosome 2 of B. xenovorans LB400T (12). While this chromosome also carries a homolog encoding pyochelin (catechol siderophore) synthesis (12), we were unable to detect catechol-type siderophores in LB400T liquid cultures. The lack of catechol-type siderophores detected in strain LB400T, as well as in all of the other diazotrophic Burkholderia isolates, could be related to the CAA culture medium used in the assay, since pyochelin production and that of its precursor salicylic acid vary according to the minerals and carbon sources available (24). In addition, the lack of correlation between the largest orange haloes exhibited on CAS-CAA medium and the very small amounts of hydroxamate siderophores found in liquid cultures from B. xenovorans isolates associated with tomato plants (even smaller amounts are found in cultures from all of the B. tropica strains) suggests that other types of siderophores, different from hydroxamates, are produced by strains of these species. Accordingly, all of the diazotrophic Burkholderia species siderophore producers associated with tomato could play a major role in the biocontrol of phytopathogens, either in tomato or in other host plants of these diazotrophs.

Certainly, the nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species associated with tomato plants represent a great potential for agro-biotechnological applications, which could lead toward using consortia of these species as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and, concomitantly, in rhizoremediation and/or for improvement of phytoremediation and for biological control of plant pathogens. However, the potential beneficial role of the Burkholderia species revealed in this study should be established under natural conditions, since a particular bacterial activity exhibited in the laboratory is not guaranteed to function in association with a host plant.

Undoubtedly, the isolation of B. unamae, B. xenovorans, B. tropica, and two other unknown N2-fixing Burkholderia species, as well as their very attractive features for agronomic and environmental applications, some detected for the first time in these species, emphasizes the significance of performing studies on taxonomy and the suitability of exploring common environments, such as the rhizosphere, for isolation of bacterial species with biotechnological potential.

Acknowledgments

We thank Socorro Cruz and Guadalupe Paredes for technical assistance. We are grateful to Michael Dunn (CCG-UNAM) for reading the manuscript and to Rosa M. Pitard (EMBRAPA-Seropédica, Brazil) for supplying strain “B. brasilensis” M130. We also thank Matthew A. Parker (State University of New York at Binghamton) for supplying Burkholderia sp. strain mpa2.1a. We acknowledge Martín Arellano, Antonio Trujillo, and José Leyva for plant collection.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arnow, L. E. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine tyrosine mixture. J. Biol. Chem. 118:531-537. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. More, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1987. Current protocols in molecular microbiology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 3.Baldwin, B. R., C. H. Nakatsu, and L. Nies. 2003. Detection and enumeration of aromatic oxygenase genes by multiplex and real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3350-3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barac, T., S. Taghavi, B. Borremans, A. Provoost, L. Oeyen, J. V. Colpaert, J. Vangronsveld, and D. van der Lelie. 2004. Engineered endophytic bacteria improve phytoremediation of water-soluble, volatile, organic pollutants. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:583-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauernfeind, A., I. Schneider, R. Jungwirth, and C. Roller. 1999. Discrimination of Burkholderia multivorans and Burkholderia vietnamiensis from Burkholderia cepacia genomovars I, III, and IV by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1335-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belova, S. E., T. A. Pankratov, and S. N. Dedysh. 2006. Bacteria of the genus Burkholderia as a typical component of the microbial community of Sphagnum peat bogs. Microbiology 75:90-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaha, D., C. Prigent-Combaret, M. S. Mirza, and Y. Moënne-Loccoz. 2006. Phylogeny of the 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid deaminase-encoding gene acdS in phytobeneficial and pathogenic Proteobacteria and relation with strain biogeography. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 56:455-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brämer, C. O., P. Vandamme, L. F. da Silva, J. G. C. Gomez, and A. Steinbüchel. 2001. Burkholderia sacchari sp. nov., a polyhydroxyalkanoate-accumulating bacterium isolated from soil of a sugar-cane plantation in Brazil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1709-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burris, R. H. 1972. Nitrogen fixation assay—methods and techniques. Methods Enzymol. 24B:415-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caballero-Mellado, J., L. Martínez-Aguilar, G. Paredes-Valdez, and P. Estrada-de los Santos. 2004. Burkholderia unamae sp nov., an N2-fixing rhizospheric and endophytic species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1165-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chain, P. S. G., V. J. Denef, K. T. Konstantinidis, L. M. Vergez, L. Agulló, V. L. Reyes, L. Hauser, M. Córdova, L. Gómez, M. González, M. Land, V. Lao, F. Larimer, J. J. LiPuma, E. Mahenthiralingam, S. A. Malfatti, C. J. Marx, J. J. Parnell, A. Ramette, P. Richardson, M. Seeger, D. Smith, T. Spilker, W. J. Sul, T. V. Tsoi, L. E. Ulrich, I. B. Zhulin, and J. M. Tiedje. 2006. Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 harbors a multi-replicon, 9.73-Mbp genome shaped for versatility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:15280-15287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, W. M., S. M. de Faria, R. Straliotto, R. M. Pitard, J. L. Simões-Araujo, J.-H. Chou, Y.-J. Chou, E. Barrios, A. R. Prescott, G. N. Elliott, J. I. Sprent, J. P. W. Young, and E. K. James. 2005. Proof that Burkholderia strains form effective symbioses with legumes: a study of novel Mimosa-nodulating strains from South America. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7461-7471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, W.-M., E. K. James, T. Coenye, J.-H. Chou, E. Barrios, S. M. de Faria, G. N. Elliott, S.-Y. Sheu, J. I. Sprent, and P. Vandamme. 2006. Burkholderia mimosarum sp. nov., isolated from root nodules of Mimosa spp. from Taiwan and South America. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:1847-1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiarini, L., A. Bevivino, C. Dalmastri, S. Tabacchioni, and P. Visca. 2006. Burkholderia cepacia complex species: health hazards and biotechnological potential. Trends Microbiol. 14:277-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coenye, T., D. Henry, D. P. Speert, and P. Vandamme. 2004. Burkholderia phenoliruptrix sp. nov., to accommodate the 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid and halophenol-degrading strain AC1100. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27:623-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coenye, T., and P. Vandamme. 2003. Diversity and significance of Burkholderia species occupying diverse ecological niches. Environ. Microbiol. 5:719-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Compant, S., B. Duffy, J. Nowak, C. Clément, and E. A. Barka. 2005. Use of plant growth-promoting bacteria for biocontrol of plant diseases: principles, mechanisms of action, and future prospects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4951-4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czàky, T. Z. 1948. On the estimation of bound hydroxylamine in biological materials. Acta Chem. Scand. 2:450-454. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalton, D. A., S. Dramer, N. Azios, S. Fusaro, E. Cahill, and C. Kennedy. 2004. Endophytic nitrogen fixation in dune grasses (Ammophilia arenaria and Elymus mollis) from Oregon. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniel, O., M. S. Meier, J. Schlatter, and P. Frischknecht. 1999. Selected phenolic compounds in cultivated plants: ecologic functions, health implications, and modulation by pesticides. Environ. Health Perspect. 107:109-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de los Cobos-Vasconcelos, D., F. Santoyo-Tepole, C. Juárez-Ramírez, N. Ruiz-Ordaz, and C. J. J. Galíndez-Mayer. 2006. Cometabolic degradation of chlorophenols by a strain of Burkholderia in fed-batch culture. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 40:57-60. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobbelaere, S., J. Vanderleyden, and Y. Okon. 2003. Plant growth-promoting effects of diazotrophs in the rhizosphere. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 22:107-149. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy, B. K., and G. Défago. 1999. Environmental factors modulating antibiotic and siderophore biosynthesis by Pseudomonas fluorescens biocontrol strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2429-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erickson, B. D., and F. J. Mondello. 1992. Nucleotide sequencing and transcriptional mapping of the genes encoding biphenyl dioxygenase, a multicomponent polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading enzyme in Pseudomonas strain LB400. J. Bacteriol. 174:2903-2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Estrada, P., P. Mavingui, B. Cournoyer, F. Fontaine, J. Balandreau, and J. Caballero-Mellado. 2002. A N2-fixing endophytic Burkholderia sp. associated with maize plants cultivated in Mexico. Can. J. Microbiol. 48:285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estrada-de los Santos, P., R. Bustillos-Cristales, and J. Caballero-Mellado. 2001. Burkholderia, a genus rich in plant-associated nitrogen fixers with wide environmental and geographic distribution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2790-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuentes-Ramírez, L. E., and J. Caballero-Mellado. 2005. Bacterial biofertilizers, p. 143-172. In Z. A. Siddiqui (ed.), PGPR: biocontrol and biofertilization. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 29.Gibson, J., and C. S. Harwood. 2002. Metabolic diversity in aromatic compound utilization by anaerobic microbes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:345-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glick, B. R., D. M. Penrose, and J. Li. 1998. A model for the lowering of plant ethylene concentrations by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. J. Theor. Biol. 190:63-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goméz-de-Jesús, A., A. Lara-Rodríguez, F. Santoyo-Tepole, C. Juárez-Ramírez, E. Cristiani-Urbina, N. Ruiz-Ordaz, and J. Galíndez Mayer. 2003. Biodegradation of the water-soluble gasoline components in a novel hybrid bioreactor. Eng. Life Sci. 3:306-312. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goris, J., P. de Vos, J. Caballero-Mellado, J.-H. Park, E. Falsen, J. F. Quensen III, J. M. Tiedje, and P. Vandamme. 2004. Classification of the PCB- and biphenyl-degrading strain LB400 and relatives as Burkholderia xenovorans sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:1677-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Govindarajan, M., J. Balandreau, R. Muthukumarasamy, G. Revathi, and C. Lakshminarasimhan. 2006. Improved yield of micropropagated sugarcane following inoculation by endophytic Burkholderia vietnamiensis. Plant Soil 280:239-252. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayatsu, M., M. Hirano, and S. Tokuda. 2000. Involvement of two plasmids in fenitrothion degradation by Burkholderia sp. strain NF100. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1737-1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hofer, B., L. D. Eltis, D. N. Dowling, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Genetic analysis of a Pseudomonas locus encoding a pathway for biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. Gene 130:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holguin, G., and B. R. Glick. 2003. Transformation of Azospirillum brasilense Cd with an ACC deaminase gene from Enterobacter cloacae UW4 fused to the Tetr promoter improves its fitness and plant growth promoting ability. Microb. Ecol. 46:122-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Honma, M., and T. Shimomura. 1978. Metabolism of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid. Agric. Biol. Chem. 42:1825-1831. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jukes, T. H., and C. R. Cantor. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules, p. 21-132. In H. N. Munro (ed.), Mammalian protein metabolism. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 39.Kennedy, I. R., A. T. M. A. Choudhury, and M. L. Kecskés. 2004. Non-symbiotic bacterial diazotrophs in crop-farming systems: can their potential for plant growth promotion be better exploited? Soil Biol. Biochem. 36:1229-1244. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kikuchi, Y., X.-Y. Meng, and T. Fukatsu. 2005. Gut symbiotic bacteria of the genus Burkholderia in the broad-headed bugs Riptortus clavatus and Leptocorisa chinensis (Heteroptera: Alydidae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4035-4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. A. Urban, and J. B. Goldberg. 2005. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:144-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marin, V. A., K. R. S. Teixeira, and J. I. Baldani. 2003. Characterization of amplified polymerase chain reaction glnB and nifH gene fragments of nitrogen-fixing Burkholderia species. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 36:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meyer, J. M., A. Stintzi, D. de Vos, P. Cornelis, R. Tappe, K. Taraz, and H. Budzikiewicz. 1997. Use of siderophores to type pseudomonads: the three Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyoverdine systems. Microbiology 143:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller, S. C. M., J. J. LiPuma, and J. L. Parke. 2002. Culture-based and non-growth-dependent detection of the Burkholderia cepacia complex in soil environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3750-3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nautiyal, C. S. 1999. An efficient microbiological growth medium for screening phosphate solubilizing microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 170:265-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nei, M., and W. H. Li. 1979. Mathematical model for studying genetic variations in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:5269-5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Sullivan, L. A., and E. Mahenthiralingam. 2005. Biotechnological potential within the genus Burkholderia. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 41:8-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perin, L., L. Martínez-Aguilar, R. Castro-González, P. Estrada-de los Santos, T. Cabellos-Avelar, H. V. Guedes, V. M. Reis, and J. Caballero-Mellado. 2006. Diazotrophic Burkholderia species associated with field-grown maize and sugarcane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3103-3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perin, L., L. Martínez-Aguilar, G. Paredes-Valdez, J. I. Baldani, P. Estrada-de los Santos, V. M. Reis, and J. Caballero-Mellado. 2006. Burkholderia silvatlantica sp. nov., a diazotrophic bacterium associated with sugar cane and maize. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:1931-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Poly, F., L. Jocteur-Monrozier, and R. Bally. 2001. Improvement in the RFLP procedure for studying the diversity of nifH genes in communities of nitrogen fixers in soil. Res. Microbiol. 152:95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramette, A., J. J. LiPuma, and J. M. Tiedje. 2005. Species abundance and diversity of Burkholderia cepacia complex in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1193-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reeves, M. W., L. Pine, J. B. Neilands, and A. Balows. 1983. Absence of siderophore activity in Legionella species grown in iron-deficient media. J. Bacteriol. 154:324-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reis, V. M., P. Estrada-de los Santos, S. Tenorio-Salgado, J. Vogel, M. Stoffels, S. Guyon, P. Mavingui, V. L. D. Baldani, M. Schmid, J. I. Baldani, J. Balandreau, A. Hartmann, and J. Caballero-Mellado. 2004. Burkholderia tropica sp nov., a novel nitrogen-fixing, plant-associated bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54:2155-2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez, H., and R. Fraga. 1999. Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotechnol. Adv. 17:319-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodríguez, H., R. Fraga, T. Gonzalez, and Y. Bashan. 2006. Genetics of phosphate solubilization and its potential applications for improving plant growth-promoting bacteria. Plant Soil 287:15-21. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roesch, L. F. W., F. L. Olivares, L. M. P. Passaglia, P. A. Selbach, E. L. S. de Sa, and F. A. O. de Camargo. 2006. Characterization of diazotrophic bacteria associated with maize: effect of plant genotype, ontogeny and nitrogen-supply. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22:967-974. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rösch, C., A. Mergel, and H. Bothe. 2002. Biodiversity of denitrifying and dinitrogen-fixing bacteria in an acid forest soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3818-3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roselló-Mora, R., and R. Amann. 2001. The species concept for prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:39-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salles, J. F., F. A. de Souza, and J. D. van Elsas. 2002. Molecular method to assess the diversity of Burkholderia species in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1595-1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Salles, J. F., E. Samyn, P. Vandamme, J. A. van Veen, and J. D. van Elsas. 2006. Changes in agricultural management drive the diversity of Burkholderia species isolated from soil on PCAT medium. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38:661-673. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salles, J. F., J. A. van Veen, and J. D. van Elsas. 2004. Multivariate analyses of Burkholderia species in soil: effect of crop and land use history. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4012-4020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwyn, B., and J. B. Neilands. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shah, S., J. Li., B. A. Moffatt, and B. R. Glick. 1998. Isolation and characterization of ACC deaminase genes from two different plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:833-843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siddiqui, Z. A. 2005. PGPR: prospective biocontrol agents of plant pathogens, p. 111-142. In Z. A. Siddiqui (ed.), PGPR: biocontrol and biofertilization. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 67.Sneath, P. H. A., and R. R. Sokal. 1973. Numerical taxonomy. W. H. Freeman & Co., San Francisco, CA.

- 68.Taghavi, S., T. Barac, B. Greenberg, B. Borremans, J. Vangronsveld, and D. van der Lelie. 2005. Horizontal gene transfer to endogenous endophytic bacteria from poplar improves phytoremediation of toluene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8500-8505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tillmann, S., C. Strömpl, K. N. Timmis, and W.-R. Abraham. 2005. Stable isotope probing reveals the dominant role of Burkholderia species in aerobic degradation of PCBs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 52:207-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Valdés, M., N. O. Pérez, P. Estrada-de los Santos, J. Caballero-Mellado, J. J. Peña-Cabriales, P. Normand, and A. M. Hirsch. 2005. Non-Frankia actinomycetes isolated from surface-sterilized roots of Casuarina equisetifolia fix nitrogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:460-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Valverde, A., P. Delvasto, A. Peix, E. Velásquez, I. Santa-Regina, A. Ballester, C. Rodríguez-Barrueco, C. Garcia-Balboa, and J. M. Igual. 2006. Burkholderia ferrariae sp nov., isolated from an iron ore in Brazil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:2421-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vandamme, P., J. Goris, W.-M. Chen, P. de Vos, and A. Willems. 2002. Burkholderia tuberum sp. nov. and Burkholderia phymatum sp. nov., nodulate the roots of tropical legumes. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 25:507-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vandamme, P., B. Pot, M. Gillis, P. de Vos, K. Kersters, and J. Swings. 1996. Polyphasic taxonomy, a consensus approach to bacterial systematics. Microbiol. Rev. 60:407-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Loon, L. C., P. A. H. M. Bakker, and C. M. J. Pieterse. 1998. Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 36:453-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weber, O. B., V. L. D. Baldani, K. R. S. Teixeira, G. Kirchhof, J. I. Baldani, and J. Döbereiner. 1999. Isolation and characterization of diazotrophic bacteria from banana and pineapple plants. Plant Soil 210:103-113. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weisburg, W. G., S. M. Barns, D. A. Pelletier, and D. J. Lane. 1991. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173:697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Witzig, R., H. Junca, H.-J. Hecht, and D. H. Pieper. 2006. Assessment of toluene/biphenyl dioxygenase gene diversity in benzene-polluted soils: links between benzene biodegradation and genes similar to those encoding isopropylbenzene dioxygenases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3504-3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang, H.-C., W.-T. Im, K. K. Kim, D.-S. An, and S.-T. Lee. 2006. Burkholderia terrae sp. nov., isolated from a forest soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:453-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang, H., S. Hanada, T. Shigematsu, K. Shibuya, Y. Kamagata, T. Kanagawa, and R. Kurane. 2000. Burkholderia kururiensis sp. nov., a trichloroethylene (TCE)-degrading bacterium isolated from aquifer polluted with TCE. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50:743-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang, H., H. Luo, and Y. Kamagata. 2003. Characterization of the phenol hydroxylase from Burkholderia kururiensis KP23 involved in trichloroethylene degradation by gene cloning and disruption. Microbes Environ. 18:167-173. [Google Scholar]