Abstract

A recombinant protein expression system working at low temperatures is expected to be useful for the production of thermolabile proteins. We constructed a low-temperature expression system using an Antarctic cold-adapted bacterium, Shewanella sp. strain Ac10, as the host. We evaluated the promoters for proteins abundantly produced at 4°C in this bacterium to express foreign proteins. We used 27 promoters and a broad-host-range vector, pJRD215, to produce β-lactamase in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. The maximum yield was obtained when the promoter for putative alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) was used and the recombinant cells were grown to late stationary phase. The yield was 91 mg/liter of culture at 4°C and 139 mg/liter of culture at 18°C. We used this system to produce putative peptidases, PepF, LAP, and PepQ, and a putative glucosidase, BglA, from a psychrophilic bacterium, Desulfotalea psychrophila DSM12343. We obtained 48, 7.1, 28, and 5.4 mg/liter of culture of these proteins, respectively, in a soluble fraction. The amounts of PepF and PepQ produced by this system were greater than those produced by the Escherichia coli T7 promoter system.

The recombinant protein expression system has contributedg greatly to structural and functional analyses of proteins and their applications. Recombinant protein expression systems are usually employed for the overproduction of proteins whose isolation from their original producers is difficult due to their low content (5). In order to characterize proteins encoded by environmental DNAs whose sources are not culturable, it is essential to produce them as recombinant proteins in a different host.

Many host-vector systems have been constructed for the production of recombinant proteins using various organisms, including bacteria (21, 27), eukaryotic microorganisms (7), insects (20), and mammalian cells (5). Nevertheless, there are still many proteins whose overproduction by a recombinant protein expression system is difficult. These include proteins with low stability (6), proteins that are toxic to the host, and proteins that tend to form inclusion bodies.

In this study, we constructed a new protein expression system using a cold-adapted bacterium, Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 (10), as the host. The strain was isolated from Antarctic seawater and grows well at low temperatures close to 0°C (10). Protein expression at low temperatures is expected to alleviate the heat denaturation of proteins and would be suitable for the production of thermolabile proteins. A low-temperature expression system is also useful for the production of enzymes whose activities are harmful to the host cells, such as proteases that degrade the essential components of the host, because the enzyme activities can be suppressed by lowering the temperature. The system would also be favorable to the overproduction of proteins that tend to form inclusion bodies because the formation of inclusion bodies is sometimes avoided by lowering the cultivation temperature (24). When Escherichia coli is used as the host, the cultivation temperature is sometimes decreased to about 18°C to suppress the formation of inclusion bodies. With protein expression systems constructed with a cold-adapted microorganism as the host, it is possible to decrease the cultivation temperature to about 0°C, which would suppress the formation of inclusion bodies more effectively.

Despite these attractive prospects, there are only a few reports on low-temperature expression systems constructed with a cold-adapted bacterium as the host (2, 4, 15). Duilio et al. constructed a system with Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125 to produce various recombinant proteins, such as cold-active α-amylase from P. haloplanktis TAB23 (4). However, the low-temperature expression system is still in a very early stage of development, and further improvement of the system is required, in particular, to increase the yield of proteins.

We recently analyzed the whole genome sequence of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10, and its draft genome sequence is currently available. Using this information, we conducted proteomic analysis of the strain to identify low-temperature-inducible proteins, which may play an important role in the cold adaptation of the strain (J. Kawamoto, T. Kurihara, M. Kitagawa, I. Kato, and N. Esaki, unpublished data). Such information would be helpful in genetically engineering the strain to make it more suitable for the production of foreign proteins. Thus, we developed a new protein expression system using Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 as the host. Here, we report the construction of expression vectors for this strain and the production of foreign proteins at low temperatures using this newly developed system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms, media, and plasmids.

Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 isolated from Antarctic seawater was used as the host for the production of foreign proteins. E. coli DH5α was used as the host for plasmid construction, and E. coli S17-1 was used as the donor strain in the conjugation experiments. Desulfotalea psychrophila DSM12343, a psychrophilic bacterium, was used as a source of the genes to be expressed in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. Shewanella sp. strain Ac10, E. coli DH5α, and E. coli S17-1 were grown in LB broth in the presence or absence of kanamycin (40 μg/ml). D. psychrophila DSM12343 was anaerobically grown in DSM medium 861 (9). A broad-host-range vector, pJRD215 (3), was used to construct plasmids for protein expression in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10.

2D PAGE analysis and identification of proteins.

Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 was grown at 4°C and 18°C. Soluble proteins and membrane proteins were analyzed by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D PAGE) with Immobiline Drystrip (pI range, 4 to 7; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for the first dimension and gradient gels (10 to 20% acrylamide) (PAG large “Daiichi” 2D-10/20; Daiichi Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) for the second dimension. Proteins were stained with SYPRO Ruby (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and analyzed with PDQuest ver. 7.0 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Protein identification was done by peptide mass fingerprinting.

Conjugation.

pJRD215 and its derivatives were introduced into E. coli S17-1 by electroporation and then transferred to Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 by conjugation as follows. E. coli S17-1 harboring pJRD215 and its derivatives was cultivated at 37°C aerobically in 5 ml of LB medium without antibiotics until the optical density at 600 nm reached 1.0. Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 was cultivated in 5 ml of LB medium at 18°C aerobically until the optical density at 600 nm reached 2.0. The cells (100 μl) were mixed with the E. coli S17-1 cells (100 μl) and incubated on LB plates at 18°C for 24 h. The bacteria grown on the plate were collected with LB medium and spread onto LB plates containing 40 μg/ml kanamycin. The plates were incubated at 18°C, and pinkish colonies of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 harboring the plasmid were selected.

Quantification of pJRD215 in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 by real-time PCR.

The copy number of pJRD215 in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 was estimated by real-time PCR with Stratagene Mx3000 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The SuperScript III PlatinumR SYBR Green One-Step qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to amplify a fragment of pJRD215 with 0.1 ng to 100 ng of total DNA from the cells harboring pJRD215, which were cultivated to log phase at 4°C and 18°C. The standard amplification curve was obtained with 0.1 pg to 1,000 pg of purified pJRD215. We used two primer sets yielding a 200-bp PCR product. KmR-f and KmR-r were used to amplify the internal region of the kanamycin resistance (Kanr) gene, and Ori-f and Ori-r were used to amplify the replication origin (ori) of pJRD215 (3) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min and 50 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The number of pJRD215 plasmids (10.2 kbp) per chromosome (4,550 kbp) was determined.

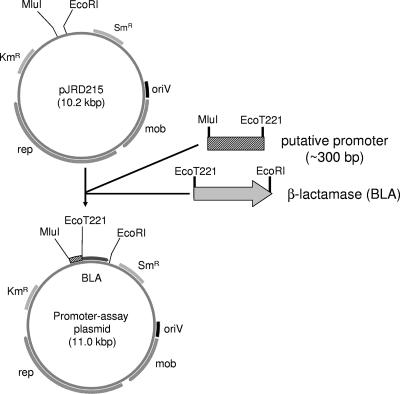

Construction of plasmids for the promoter assay.

Plasmids were constructed by standard genetic manipulations (18). DNA fragments containing the upstream regions (300 bp) of the genes listed in Table 1 were amplified by PCR with the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material using KOD plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) or Phusion DNA polymerase (Finzymes, Oy, Finland) following the manufacturers' instructions. The PCR products were digested with MluI and EcoT221 or NdeI. The β-lactamase gene to be used as a reporter was amplified by PCR with pBR322 as a template, and either BLA-f_EcoT221 and BLA-r_EcoRI or BLA-f_NdeI and BLA-r_EcoRI were used as the primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were digested with EcoT221 and EcoRI or NdeI and EcoRI. pJRD215 was digested with MluI and EcoRI. After digestion, the PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and ligated to pJRD215 (Fig. 1). The sequences of these plasmids were verified by nucleotide sequencing with the ABI prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The plasmids were introduced into Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 as described above.

TABLE 1.

List of promoters used for the production of foreign proteins in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10

| Protein | Accession no. | Intensity

|

Ratio (4°C/18°C) | Promoter name (promoter assay plasmid) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4°C | 18°C | ||||

| Low-temperature-inducible proteins | |||||

| Long-chain fatty acid transport protein (FadL) | AB284095 | 2,050 | 839 | 2.44 | LI1 (pLI1) |

| Nucleoside-binding outer membrane protein (Tsx) | AB284082 | 1,890 | <30 | >63 | LI2 (pLI2) |

| Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) | AB283025 | 7,320 | 1,480 | 4.95 | LI3 (pLI3) |

| Predicted outer membrane proteina | AB284079 | 1,520 | <30 | >50.7 | LI4 (pLI4), LI12 |

| (pLI12) | |||||

| Outer membrane protein (OmpC) | AB284090 | 3,040 | 1,430 | 2.13 | LI5 (pLI5) |

| Electron transfer flavoprotein α subunit (FixB) | AB284109 | 2,410 | <30 | >80.3 | LI6 (pLI6) |

| Ribosomal protein S1 (RpsA) | AB285527 | 3,820 | 1,170 | 3.26 | LI7 (pLI7) |

| 6Fe-6S prismane cluster-containing protein (Ppx1) | AB284110 | 988 | <30 | >32.9 | LI8 (pLI8) |

| Cell division GTPase (FtsZ) | AB284074 | 1,150 | <30 | >38.3 | LI9 (pLI9) |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase α subunit (RpoA) | AB284093 | 782 | <30 | >26.1 | LI10 (pLI10) |

| Inorganic diphosphatase | AB284081 | 1,030 | <30 | >34.3 | LI11 (pLI11) |

| Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase (DeoC) | AB284104 | 1,870 | <30 | >62.3 | LI13 (pLI13) |

| Cold shock protein (CspA) | AB284087 | 17,300 | <30 | >577 | LI14 (pLI14) |

| Peptidyl prolyl isomerase (Tig) | AB284101 | 4,790 | <30 | >160 | LI15 (pLI15) |

| Phosphoribosylamine glycine ligase | AB284115 | 1,350 | <30 | >45 | LI16 (pLI16) |

| Dihydrolipoamide acyltransferase | AB284092 | 667 | <30 | >22.2 | LI17 (pLI17) |

| Heat shock protein (DnaK) | AB284103 | 14,000 | <30 | >467 | LI18 (pLI18) |

| ABC-type multidrug/protein/lipid transport system (MdlB) | AB284078 | 1,120 | <30 | >37.3 | LI19 (pLI19) |

| Flagellar-hook protein (FlgE) | AB284085 | 780 | <30 | >26 | LI20 (pLI20) |

| Proteins abundantly produced at low temperatures | |||||

| ATP synthase β subunit | AB284111 | 13,900 | 8,100 | 1.72 | AP1 (pAP1) |

| Heat shock protein (GroES) | AB284105 | 10,800 | 6,410 | 1.69 | AP2 (pAP2) |

| Other proteins | |||||

| Polyketide synthase modules and related proteins | AB284096 | OP1 (pOP1) | |||

| AB284097 | OP2 (pOP2) | ||||

| AB284098 | OP3 (pOP3) | ||||

| Cold shock protein (CspA) | AB284076 | OP4 (pOP4) | |||

| AB284099 | OP5 (pOP5) | ||||

The gene for the predicted outer membrane protein (AB284079) has two putative promoter sequences (LI4 and LI12).

FIG. 1.

Construction of the plasmids for the promoter assay. rep, replication-related genes; mob, mobilization-related genes; oriV, replication origin; Kmr, kanamycin resistance gene; Smr, streptomycin resistance gene.

β-Lactamase assay.

The recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells harboring various plasmids were cultivated aerobically in 5 ml of a liquid LB medium containing 20 μg/ml kanamycin at 4°C or 18°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C or 18°C and suspended in 1 ml of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The cells were homogenized by sonication. The debris was removed by centrifugation at 21,000 × g for 15 min. The cell extracts and the culture supernatant were used for the enzyme assay.

The β-lactamase activity was measured at 30°C with 100 μM nitrocefin, a chromogenic substrate, in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The formation of the product was monitored by measuring the increase of the absorbance at 486 nm with SPECTRA MAX 190 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The molar extinction coefficient of hydrolyzed nitrocefin is 20,500 M−1 cm−1. One unit of the enzyme was defined as the amount of the enzyme that catalyzed the formation of 1 μmol of the product in 1 min.

RNA isolation and primer extension.

Total RNA was isolated from the recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells harboring pJRD215, pAP2, pLI3, and pLI14 grown at 18°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 1.0 using the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Primer extension reactions were performed with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled BLA primer (FITC-BLA) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and ThermoScript RT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The products were analyzed with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sizes of the primer extension products were compared with the sizes of the sequencing reaction products generated using the Thermo Sequenase Primer Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) with the same plasmid as a template and the same primer as those used for the reverse transcription reactions.

Protein assay.

The protein concentration was determined with a protein assay kit (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The yields of recombinant proteins in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 were estimated by analyzing the intensity of the protein bands with ImageQuant 5.2 software (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Cloning and expression of the genes from D. psychrophila DSM12343.

We performed PCR amplification of the LI3 promoter (Table 1) of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 and the DNA fragments coding for an oligoendopeptidase homolog (PepF; accession no. CAG36171), a leucylaminopeptidase homolog (LAP; accession no. CAG37333), a prolidase homolog (PepQ; accession no. CAG37144), and a β-glucosidase homolog (BglA; accession no. YP_066184) from D. psychrophila DSM12343 with KOD plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), the genomic DNA as a template, and the primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The DNA fragments coding for PepF, LAP, PepQ, and BglA were connected with the LI3 promoter by overlap extension (8). The fragments obtained were digested with MluI and EcoRI and ligated with pJRD215 digested with the same restriction enzymes to produce pLI3-PepF, pLI3-LAP, pLI3-PepQ, and pLI3-BglA, respectively. The plasmids were introduced into Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 for the production of the proteins. The recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells were cultivated in 5 ml of LB medium containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin at 18°C for 48 h or at 4°C for 96 h.

Plasmids for the production of PepF, LAP, PepQ, and BglA under the control of the T7 promoter in E. coli were constructed as follows. The genes coding for these proteins were amplified by PCR with KOD plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). The primers used are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The PCR products were digested with NdeI and XhoI or NheI and XhoI and inserted into pET21a(+) digested with the same restriction enzymes. The resultant plasmids, pET-PepF, pET-LAP, pET-PepQ, and pET-BglA, were introduced into E. coli BL21(DE3) to produce the proteins. The recombinant E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were cultivated in 5 ml of LB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37°C or 18°C until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.2 to 0.8. The culture was supplemented with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, and the cells were grown for another 3 h at 37°C or 12 h at 18°C.

Proteins produced by the recombinant cells were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-PAGE and quantified with ImageQuant 5.2 software (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The activities of PepF, LAP, PepQ, and BglA were measured according to methods described previously (12-14, 19). To examine their thermostabilities, the proteins were preincubated in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 30 min at various temperatures, and the remaining activities were measured.

RESULTS

A search for promoters to express foreign proteins in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10.

In order to construct a protein expression system operating at low temperatures, we searched for DNA fragments showing high promoter activities in a psychrotrophic bacterium, Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. We analyzed the proteins of this psychrotroph grown at 4°C and 18°C by 2D PAGE (Kawamoto et al., unpublished) and identified proteins whose intensities at 4°C were more than two times higher than those at 18°C (Table 1, low-temperature-inducible proteins). We also identified proteins whose intensities at 4°C were higher than 10,000 ppm (1% of the total proteins) (Table 1, proteins abundantly produced at low temperatures). The promoters of the genes coding for these proteins were tested for their abilities to produce foreign proteins at low temperatures in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. The promoters for other proteins listed in Table 1 were also tested. These proteins included polyketide synthase modules and related proteins, which are supposed to catalyze the synthesis of eicosapentaenoic acid, the amount of which is increased at low temperatures (10).

For the promoter assay, we used a gram-negative broad-host-range vector, pJRD215, which replicates in both Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 and E. coli. The copy numbers of this plasmid were 1.1 and 2.7 to 2.9, respectively, in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 grown at 4°C and 18°C. We amplified the immediate upstream regions (about 300 bp) of the initiation codons of the genes coding for the proteins listed in Table 1. The amplified DNA fragment was fused with the β-lactamase gene from E. coli and introduced into pJRD215 as described in Materials and Methods. The plasmids obtained were introduced into E. coli S17-1 and then transferred to Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 by conjugation.

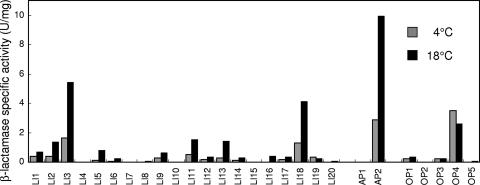

The recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells were grown to late-log phase at 4°C and 18°C, and the β-lactamase activities in the cell lysate and the culture supernatant were measured. We found that the total activities in the culture supernatant were less than 5% of the total activities in the cell lysate (data not shown). The specific activities of β-lactamase in the cell lysate are shown in Fig. 2. The highest activity was found in the cells harboring pAP2 [Ac10(pAP2)] grown at 18°C, followed by the cells harboring pLI3 [Ac10(pLI3)] grown at 18°C. These plasmids contained promoters for the putative chaperonin GroES and the putative alkyl hydroperoxide reductase AhpC, respectively (Table 1). Although GroES and AhpC were produced more abundantly at 4°C than at 18°C in the wild-type strain (Table 1), the specific activities of β-lactamase in Ac10(pAP2) and Ac10(pLI3) were higher at 18°C than at 4°C. When the β-lactamase activities of all the recombinant strains were compared at 4°C, the cells harboring pOP4 [Ac10(pOP4)] showed the highest activity (Fig. 2). The plasmid contained a promoter for the putative cold shock protein CspA (Table 1). The β-lactamase activity in Ac10(pOP4) was 1.3 times higher at 4°C than at 18°C.

FIG. 2.

Specific activities of β-lactamases from recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells grown at 4°C and 18°C.

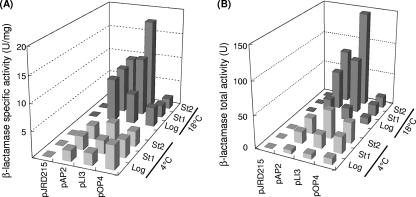

Ac10(pAP2), Ac10(pLI3), and Ac10(pOP4) were grown to late log phase, stationary phase, and late stationary phase at 4°C and 18°C, and the β-lactamase activities in the cell lysates were measured (Fig. 3). The highest specific activity was found in Ac10(pLI3) grown to late stationary phase at 18°C (Fig. 3A). When the activities were compared at 4°C, the highest specific activity was found in Ac10(pOP4) grown to late log phase (Fig. 3A). As the cultivation proceeded, the specific activity of the enzyme in Ac10(pLI3) increased, whereas that in Ac10(pOP4) decreased. The specific activity in Ac10(pAP2) did not change significantly during the cultivation. The highest total activity was found in Ac10(pLI3) grown to late stationary phase at both 4°C and 18°C (Fig. 3B). SDS-PAGE analysis of the proteins in Ac10(pLI3) grown to late stationary phase indicated that the amounts of β-lactamase produced were 91 mg/liter of culture at 4°C and 139 mg/liter of culture at 18°C.

FIG. 3.

Activities of β-lactamases from recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells. (A) Specific activities of β-lactamases from cells harboring pJRD215, pAP2, pLI3, and pOP4. Cells harboring pJRD215 were used as a negative control. (B) Total activities of β-lactamase from recombinant Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells. Log, log phase; St1, stationary phase (24 h at 18°C and 72 h at 4°C); St2, stationary phase (48 h at 18°C and 96 h at 4°C).

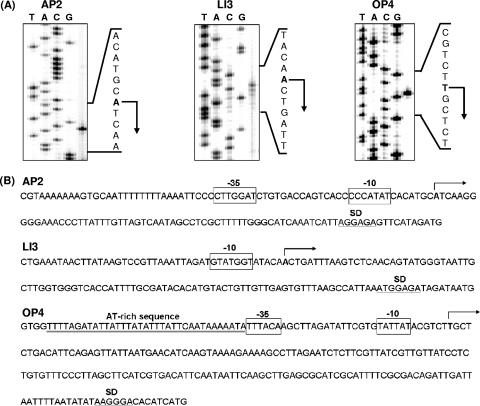

Determination of transcription initiation sites.

To determine the transcription initiation sites, primer extension experiments were carried out using a FITC-labeled primer complementary to the 5′ region of the β-lactamase gene. The transcription initiation sites from AP2, LI3, and OP4 were determined as shown in Fig. 4A. In the upstream region of the transcript from AP2, a σ32-type promoter sequence was found (Fig. 4B). The −35 sequence (CTTGGAT) and the −10 sequence (CCCATAT) resembled the −35 consensus sequence (CTTGAAA) and the −10 consensus sequence (CCCATNT), respectively, of the E. coli promoters recognized by σ32 (26). In the upstream region of the transcript from LI3, a sequence, GTATGGT, showing weak similarity to the −10 consensus sequence of the E. coli σ38-type promoter, CTATACT, was found (23) (Fig. 4B). In the upstream region of the transcript from OP4, a σ70-type promoter sequence was found (Fig. 4B). The −35 sequence (TTTACA) and the −10 sequence (TATTAT) were similar to the −35 consensus sequence (TTGACA) and the −10 consensus sequence (TATAAT), respectively, recognized by σ70 of E. coli (26). We found that OP4 has an AT-rich sequence immediately upstream of the −35 region and that the transcript from OP4 has an unusually long 5′ untranslated region (179 bases).

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis. (A) Primer extension analysis of transcripts from the promoters AP2, LI3, and OP4. The transcripts are shown by arrows. The sequencing ladders were generated using the same primers as those used in the dideoxy sequencing reactions. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the putative promoter regions. The transcription initiation sites are marked by arrows above the nucleotide sequences. The consensus promoter sequences (−35 and −10) are boxed. The potential ribosome-binding sites (SD) are underlined. The AT-rich sequence region of OP4 is double underlined below the nucleotide sequence.

Production of proteins from a psychrophilic bacterium, D. psychrophila DSM12343.

We produced proteins from a psychrophilic bacterium, D. psychrophila DSM12343, using Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 as the host. D. psychrophila DSM12343 is similar to Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 in that it is cold adapted, but it is not closely related to Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 phylogenetically, as it belongs to the deltaproteobacteria, whereas Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 belongs to the gammaproteobacteria. The complete genomic DNA sequence of D. psychrophila DSM12343 was recently determined (17), and we used this information to clone the genes from the bacterium. Since D. psychrophila DSM12343 is psychrophilic, the majority of its proteins are supposed to be thermolabile and suitable for the evaluation of the low-temperature protein expression system.

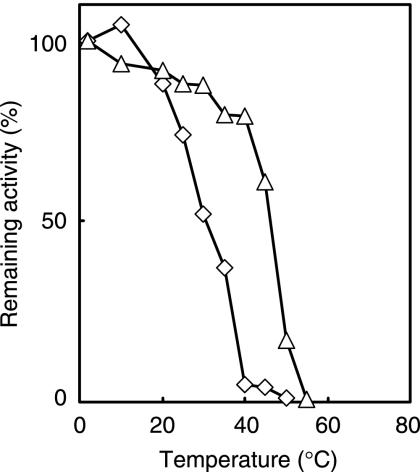

The proteins we produced were putative peptidases, PepF, LAP, and PepQ, and a putative glucosidase, BglA, which are expected to be useful for food processing (12-14, 19). We first examined the thermostabilities of these proteins (Fig. 5). The PepF activity in the extract from the recombinant E. coli cells was stable at 10°C for 30 min but unstable at temperatures above 20°C. The half-life of the enzyme at 30°C was about 30 min. BglA was fairly stable at 40°C for 30 min (80% of its original activity remained), but half of the activity was lost after incubation at 45°C for 30 min. The thermostabilities of these proteins are lower than those of their homologs from mesophiles and thermophiles (Table 2). The results supported our speculation that the proteins from D. psychrophila DSM12343 are generally thermolabile. The thermostabilities of PepQ and LAP could not be determined because the activities of PepQ and LAP were not detectable under the assay conditions employed: these proteins probably have activities other than those predicted from their primary structures.

FIG. 5.

Thermal stabilities of PepF (⋄) and BglA (▵) from D. psychrophila DSM12343. PepF and BglA in the extract from the recombinant E. coli cells were preincubated in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for 30 min at the indicated temperatures, and the remaining activities were measured.

TABLE 2.

Thermostabilities of PepF and BglA homologs

| Protein | Organism | Identity (%)a | Half-life | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PepF | D. psychrophila DSM12343 (psychrophile) | 100 | 0.5 h at 30°C | This study |

| Bacillus licheniformis N22 (mesophile) | 27 | 0.5 h at 50°C | 1 | |

| Geobacillus collagenovorans MO-1 (thermophile) | 26 | 0.5 h at 75°C | 12 | |

| BglA | D. psychrophila DSM12343 (psychrophile) | 100 | 0.5 h at 45°C | This study |

| Streptomyces sp. strain QM-B814 (mesophile) | 42 | >0.5 h at 50°C | 16 | |

| Thermus nonproteolyticus HG102 (thermophile) | 42 | 2.5 h at 90°C | 25 |

Sequence identity to the homolog from D. psychrophila DSM12343.

We produced PepF, LAP, PepQ, and BglA in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 using the LI3 promoter, with which we obtained the highest productivity of the reporter protein (Fig. 3B). As shown in Fig. 6, all four proteins were successfully produced as soluble proteins in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 at 18°C. Their yields as determined by quantifying the bands in the SDS-PAGE gel were 48, 7.1, 28, and 5.4 mg/liter of culture (Fig. 6B). At 4°C, the amounts of PepF, LAP, and PepQ produced in the soluble fraction were 25, 2.0, and 1.7 mg/liter of culture, respectively. The activity of BglA was detected in the cell extract (data not shown), but the amount of the protein was not estimated because its band was not identified in the SDS-PAGE gel.

FIG. 6.

Production of proteins from D. psychrophila DSM12343. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of cell extracts of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 harboring pPepF, pLAP, pPepQ, and pBglA. The arrowheads indicate the positions of PepF, LAP, PepQ, and BglA. Each lane contained 20 μg of total protein. M, marker; NC, negative control (Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 cells harboring pJRD215). (B) Yields of recombinant proteins. The yields were determined by analyzing the SDS-PAGE gel with ImageQuant 5.2 software.

Next, we compared the Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 expression system with the E. coli system (Fig. 6B). The four proteins from D. psychrophila DSM12343 were produced using the T7 promoter system, which is regarded as one of the most powerful expression systems currently available. At 37°C, only BglA was produced in the soluble fraction, while a comparable amount of BglA was also found in the insoluble fraction. All other proteins were found exclusively in the insoluble fraction. In contrast, all four proteins were produced in the soluble fraction at 18°C. We found that LAP and BglA were produced more abundantly in E. coli, whereas PepF and PepQ were produced more abundantly in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10.

DISCUSSION

We characterized various promoters to express foreign proteins in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. Most of the promoters we used are located in the upstream region of the genes coding for low-temperature-inducible proteins in the original strain (Table 1). Nevertheless, the promoter assay experiments indicated that the amounts of the reporter protein, β-lactamase, produced in the recombinant cells were higher at 18°C than at 4°C for most of the promoters tested (Fig. 2). This result can be partly explained by the copy number of the vector, which was higher at 18°C (2.7 to 2.9) than at 4°C (1.1). However, the difference in the copy number (2.5- to 2.6-fold) is not large enough to explain the higher activity of β-lactamase at 18°C, because the induction ratios of most of the proteins listed in Table 1 were much higher than 2.5- to 2.6-fold. Thus, the results suggest that the production of the proteins listed in Table 1 is regulated mainly at the level of translation.

We found that the promoter for groES (AP2) has putative −35 and −10 sequences similar to the −35 and −10 consensus sequences of the promoters of E. coli recognized by σ32 (Fig. 4B) (26). Although σ32 is known as a heat shock sigma factor, GroES of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 was more abundantly produced at 4°C than at 18°C (Table 1). Furthermore, the β-lactamase gene under the control of the AP2 promoter was expressed not only at 18°C, but also at 4°C (Fig. 2 and 3). Considering that the copy number of pJRD215 is 2.5- to 2.6-fold higher at 18°C, the promoter activity of AP2 at 4°C is comparable to that at 18°C. Thus, it is likely that the inducible nature of the sigma factor of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 that recognizes the AP2 promoter is different from that of σ32 of E. coli.

In the promoter for ahpC (LI3), we found a putative −10 sequence, GTATGGT, showing weak similarity to the −10 consensus sequence, CTATACT, of the E. coli σ38-type promoter (23) (Fig. 4B). Although the similarity between these two sequences is low, it is likely that the transcription of the ahpC gene is controlled by a sigma factor similar to σ38 of E. coli, because σ38 is a stationary-phase sigma factor and the amount of AhpC was increased in the stationary phase (Fig. 3).

The cspA promoter (OP4) contains sequences similar to the −35 and −10 consensus sequences of the E. coli promoters recognized by σ70, the principal sigma factor of E. coli (26) (Fig. 4B). In addition to these sequences, the cspA promoter has an AT-rich sequence immediately upstream of the −35 region (Fig. 4B). A similar AT-rich sequence exists in the upstream region of the cspA gene of E. coli, and it is considered to play an important role in efficient transcription initiation at low temperatures (11). Furthermore, mRNA for CspA of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 contains an unusually long 5′ untranslated region (179 bases). The mRNA for CspA of E. coli also contains a long 5′ untranslated region (160 bases), and this region is considered to be important for mRNA stability and translation efficiency (22). The AT-rich sequence and the long 5′ untranslated region of the cspA gene of Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 probably play important roles in increasing the productivity of proteins at low temperatures.

With the system we constructed, we obtained more than 100 mg per liter of culture of β-lactamase and more than 10 mg per liter of culture of PepF and PepQ from a psychrophilic bacterium, D. psychrophila DSM12343 (Fig. 6). The yields are among the highest obtained so far with cold-adapted bacteria as the hosts (2, 4, 15). Overall, the system is comparable to the E. coli T7 promoter system, which is regarded as one of the most powerful protein expression systems. Some foreign proteins (PepF and PepQ) were produced more abundantly in Shewanella sp. strain Ac10. The results suggest that the Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 system would be suitable for the production of thermolabile proteins because PepF is thermolabile, as described in Results. Considering that the Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 system is at a much earlier stage of development than the E. coli system, there is a good prospect that the productivity of the Shewanella sp. strain Ac10 system will be significantly improved by modifying the host and the vector. The system would contribute greatly to fundamental and application studies of a number of thermolabile and other proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for 21st Century COE on Kyoto University Alliance for Chemistry from MEXT (to N.E.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 17404021 from JSPS (to T.K.), the Industrial Technology Research Grant Program from NEDO (to T.K.), a research grant from the Asahi Glass Foundation (to T.K.), a grant for Research for Promoting Technological Seeds from JST (to T.K.), and JSPS Research Fellowships for Young Scientists (to R.M.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 May 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asdornnithee, S., E. Himeji, K. Akiyama, T. Sasaki, and R. Takata. 1995. Isolation and characterization of Pz-peptidase from Bacillus licheniformis N22. J. Ferm. Bioeng. 79:200-204. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cusano, A. M., E. Parrilli, A. Duilio, G. Sannia, G. Marino, and M. L. Tutino. 2006. Secretion of psychrophilic α-amylase deletion mutants in Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 258:67-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davison, J., M. Heusterspreute, N. Chevalier, V. Ha-Thi, and F. Brunel. 1987. Vectors with restriction site banks. V. pJRD215, a wide-host-range cosmid vector with multiple cloning sites. Gene 51:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duilio, A., M. L. Tutino, and G. Marino. 2004. Recombinant protein production in Antarctic Gram-negative bacteria. Methods Mol. Biol. 267:225-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gellissen, G. 2005. Production of recombinant proteins. Novel microbial and eukaryotic expression systems. WILEY-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 6.Gerday, C., M. Aittaleb, M. Bentahir, J. P. Chessa, P. Claverie, T. Collins, S. D'Amico, J. Dumont, G. Garsoux, D. Georlette, A. Hoyoux, T. Lonhienne, M. A. Meuwis, and G. Feller. 2000. Cold-adapted enzymes: from fundamentals to biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 18:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gouka, R. J., P. J. Punt, and C. A. van den Hondel. 1997. Efficient production of secreted proteins by Aspergillus: progress, limitations and prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horton, R. M., H. D. Hunt, S. N. Ho, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene 77:61-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knoblauch, C., K. Sahm, and B. B. Jorgensen. 1999. Psychrophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria isolated from permanently cold arctic marine sediments: description of Desulfofrigus oceanense gen. nov., sp. nov., Desulfofrigus fragile sp. nov., Desulfofaba gelida gen. nov., sp. nov., Desulfotalea psychrophila gen. nov., sp. nov. and Desulfotalea arctica sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:1631-1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulakova, L., A. Galkin, T. Kurihara, T. Yoshimura, and N. Esaki. 1999. Cold-active serine alkaline protease from the psychrotrophic bacterium Shewanella strain Ac10: gene cloning and enzyme purification and characterization. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 65:611-617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitta, M., L. Fang, and M. Inouye. 1997. Deletion analysis of cspA of Escherichia coli: requirement of the AT-rich UP element for cspA transcription and the downstream box in the coding region for its cold shock induction. Mol. Microbiol. 26:321-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyake, R., Y. Shigeri, Y. Tatsu, N. Yumoto, M. Umekawa, Y. Tsujimoto, H. Matsui, and K. Watanabe. 2005. Two thimet oligopeptidase-like Pz peptidases produced by a collagen-degrading thermophile, Geobacillus collagenovorans MO-1. J. Bacteriol. 187:4140-4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mock, W. L. 2004. X-Pro dipeptidase (bacteria). Elsevier, London, United Kingdom.

- 14.Murai, A., Y. Tsujimoto, H. Matsui, and K. Watanabe. 2004. An Aneurinibacillus sp. strain AM-1 produces a proline-specific aminopeptidase useful for collagen degradation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96:810-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakashima, N., and T. Tamura. 2004. A novel system for expressing recombinant proteins over a wide temperature range from 4 to 35°C. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86:136-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Pons, J. A., A. Cayetano, X. Rebordosa, J. Lloberas, A. Guasch, and E. Querol. 1994. A β-glucosidase gene (bgl3) from Streptomyces sp. strain QM-B814. Molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, purification and characterization of the encoded enzyme, a new member of family 1 glycosyl hydrolases. Eur. J. Biochem. 223:557-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabus, R., A. Ruepp, T. Frickey, T. Rattei, B. Fartmann, M. Stark, M. Bauer, A. Zibat, T. Lombardot, I. Becker, J. Amann, K. Gellner, H. Teeling, W. D. Leuschner, F.-O. Glöckner, A. N. Lupas, R. Amann, and H.-P. Klenk. 2004. The genome of Desulfotalea psychrophila, a sulfate-reducing bacterium from permanently cold Arctic sediments. Environ. Microbiol. 6:887-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 19.Shipkowski, S., and J. E. Brenchley. 2005. Characterization of an unusual cold-active β-glucosidase belonging to family 3 of the glycoside hydrolases from the psychrophilic isolate Paenibacillus sp. strain C7. Appl. Environ Microbiol. 71:4225-4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith, G. E., M. D. Summers, and M. J. Fraser. 1983. Production of human beta interferon in insect cells infected with a baculovirus expression vector. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:2156-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorensen, H. P., and K. K. Mortensen. 2005. Advanced genetic strategies for recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 115:113-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanabe, H., J. Goldstein, M. Yang, and M. Inouye. 1992. Identification of the promoter region of the Escherichia coli major cold shock gene, cspA. J. Bacteriol. 174:3867-3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Typas, A., and R. Hengge. 2006. Role of the spacer between the −35 and −10 regions in σs promoter selectivity in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1037-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vasina, J. A., and F. Baneyx. 1997. Expression of aggregation-prone recombinant proteins at low temperatures: a comparative study of the Escherichia coli cspA and tac promoter systems. Protein Expr. Purif. 9:211-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, X., X. He, S. Yang, X. An, W. Chang, and D. Liang. 2003. Structural basis for thermostability of β-glycosidase from the thermophilic eubacterium Thermus nonproteolyticus HG102. J. Bacteriol. 185:4248-4255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wosten, M. M. 1998. Eubacterial sigma-factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22:127-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamagata, H., K. Nakahama, Y. Suzuki, A. Kakinuma, N. Tsukagoshi, and S. Udaka. 1989. Use of Bacillus brevis for efficient synthesis and secretion of human epidermal growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3589-3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.