Abstract

In Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the balance between acquiring enough iron and avoiding iron-induced toxicity is regulated in part by Fur (ferric uptake regulator). A fur mutant was constructed to address the physiological role of the regulator. Atypically, the mutant did not show alterations in the levels of siderophore biosynthesis and the expression of iron transport genes. However, the fur mutant was more sensitive than the wild type to an iron chelator, 2,2′-dipyridyl, and was also more resistant to an iron-activated antibiotic, streptonigrin, suggesting that Fur has a role in regulating iron concentrations. A. tumefaciens sitA, the periplasmic binding protein of a putative ABC-type iron and manganese transport system (sitABCD), was strongly repressed by Mn2+ and, to a lesser extent, by Fe2+, and this regulation was Fur dependent. Moreover, the fur mutant was more sensitive to manganese than the wild type. This was consistent with the fact that the fur mutant showed constitutive up-expression of the manganese uptake sit operon. FurAt showed a regulatory role under iron-limiting conditions. Furthermore, Fur has a role in determining oxidative resistance levels. The fur mutant was hypersensitive to hydrogen peroxide and had reduced catalase activity. The virulence assay showed that the fur mutant had a reduced ability to cause tumors on tobacco leaves compared to wild-type NTL4.

Iron is required for the growth of most living organisms due to the element's importance in many biological processes. Bacteria have evolved various iron-sequestering mechanisms to acquire iron from the environment and maintain intracellular homeostasis. Despite the indispensability of iron, it can be toxic in excess due to its ability to catalyze the production of highly deleterious hydroxyl radicals via the Fenton reaction (28). The generated reactive hydroxyl radicals can damage DNA, proteins, and lipids. Iron transport, storage, and consumption are coregulated to help maintain the balance between acquiring enough iron to grow and avoiding iron-induced toxicity. In many bacteria, this regulation is mediated in part by the Fur (ferric uptake regulator) protein (2, 7). Fur functions as a transcriptional repressor of iron uptake systems and iron-regulated genes when sufficient iron is available. The molecular basis of iron regulation by Fur has been most extensively studied in Escherichia coli, providing the classic model of Fur regulation (2). Fur binds to its corepressor ferrous ion (Fe2+) and the Fe2+-Fur complex binds to the conserved sequence, known as the Fur box (GATAATGATAATCATTATC), which is located in the promoter regions of Fur-regulated genes. In the absence of the cofactor Fe2+, Fur no longer binds to the regulated promoters, leading to derepression of iron uptake systems under the iron-deficient conditions. Fur could mediate targeted-gene repression in its apo form as observed in Helicobacter pylori, where the iron-free form of Fur binds to pfr (60) and sodB (17) promoters. Fur has also been reported to be an activator. This positive regulation by Fur observed in E. coli occurs via an indirect, Fur-mediated repression of a small RNA molecule, RhyB, which acts as a regulatory RNA that blocks gene expression by binding to and degrading target mRNAs (34, 35). Nonetheless, direct activation of gene transcription by Fur has been found in Neisseria meningitidis (13).

Several studies have shown that Fur's regulatory function is not limited to the control of iron metabolism genes. Fur has also been reported to regulate genes involved in acid tolerance (22, 60), the production of toxins (4, 8), and virulence factors (20, 31, 36), and defense against oxidative stress (27, 57). The wide range of genes controlled by Fur indicates that Fur serves as a global regulator.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a gram-negative, α-proteobacterium that causes crown gall tumor disease on dicotyledonous plants. The infection process involves attachment of the bacteria to wounded plant cells and subsequent transfer of a segment of DNA from the bacterium's tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant cells (67). In response to microbial infection, one active plant defense response is increased production of reactive oxygen species. In addition, plants possess mechanisms that deprive invading microbes of iron (37, 41, 51). Microbes need to overcome both oxidative stress and iron deprivation to survive and proliferate. The iron-sensing regulatory fur genes from plant pathogens have been shown to play a critical role during the plant-pathogen interaction. Reduced virulence associated with mutations in fur genes has been reported in Erwinia chrysanthemi (18) and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (53).

Interestingly, it has emerged that the metal specificity and function of Fur-like proteins from members of the α-proteobacteria are different than in the model γ-proteobacterium E. coli. Fur is best known as an iron-sensing regulator; however, there are reports that indicate a different role for Fur-like proteins from Rhizobium leguminosarum (FurRl) and Sinorhizobium meliloti (FurSm). Disruption of the fur gene had no effect on the expression of several genes that are involved in iron acquisition (10, 44, 61). Instead, FurRl and FurSm physiologically function in response to manganese by repressing transcription of the sitABCD operon, which encodes a Mn2+ uptake system, under manganese-replete conditions (10, 14, 44). In R. leguminosarum and S. meliloti, a transcriptional regulator, RirA (rhizobial iron regulator), showing no sequence similarity to Fur has been shown to replace typical Fur functions in the regulation of iron-responsive genes for controlling iron homeostasis (11, 56). The RirA regulon includes genes for the synthesis (vbs) and uptake (fhu) of the siderophore vicibactin, genes involved in heme uptake (hmu and tonB), genes that probably participate in the transport of Fe3+ (sfu), a putative ferri-siderophore ABC transporter (rrp1), a gene that specifies an extracytoplasmic function RNA polymerase δ factor (rpoI), genes for the synthesis of Fe-S clusters (suf), an iron response regulator (irrA), and rirA itself (55). The RirA protein belongs to the Rrf2 family of putative transcription regulators. The close RirA homologues appear to be confined to other members of α-proteobacteria, the rhizobium Mesorhizobium, the human pathogen Bartonella, the animal pathogen Brucella, and the phytopathogen A. tumefaciens. The RirA-like protein does not exist in Bradyrhizobium japonicum, a member of the α-proteobacteria, and its regulation of iron metabolism is, at least in part, still modulated by Fur-like protein (FurBj) in cooperation with another regulator called Irr (iron response regulator) through controlling the heme biosynthesis pathway (23, 24). The B. japonicum Irr protein was first described as a repressor of hemB, the gene encoding the enzyme δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase that catalyzes the second step in heme biosynthesis, under iron-restricted conditions to prevent the accumulation of toxic protoporphyrin intermediates from exceeding iron availability. The presence of iron causes repression of irr transcription via Fur (19, 24) and degradation of Irr protein by oxidation in a heme-dependent mechanism (46, 65). Both these transcriptional and posttranslational controls lead to derepression of heme biosynthesis under iron-replete conditions. Subsequently, it has been shown that Irr was both a transcriptional activator and a repressor of many genes involved in iron transport, storage, and metabolism (49). Moreover, Irr also controlled genes involved in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, energy metabolism, and oxidative stress response (49). It is notable that B. japonicum and R. leguminosarum each have a second irr gene named irrB with unknown function(s).

Analysis of the A. tumefaciens genome revealed three fur homologues, named fur (Atu0354), irr (Atu0153), and zur (zinc uptake regulator; Atu1518) (64). However, the functions of these transcriptional regulators have not been defined. In the present study, the physiological function of the A. tumefaciens fur gene (furAt) was investigated. The important roles of furAt in metal and oxidative stress responses are demonstrated. In addition, Fur contributes significantly to the virulence of A. tumefaciens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. A. tumefaciens strains were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 28°C with shaking at 150 rpm. The medium was supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin (Ap) ml−1, 25 μg of chloramphenicol (Cm) ml−1, 90 μg of gentamicin (Gm) ml−1, or 10 μg of tetracycline (Tc) ml−1 as required. E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C in LB medium supplemented with 100 μg of Ap ml−1, 30 μg of Gm ml−1, or 15 μg of Tc ml−1 as required.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| A. tumefaciens | ||

| NTL4 | Wild type | S. K. Farrand |

| NTLfur | fur mutant, a derivative of NTL4 in which fur was disrupted by pKNOCKfur; Gmr | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | supE Δlac(φ80dlacZΔM15) hsdR recA endA gyrA thi relA | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T-Easy | Cloning vector; Apr | Promega |

| pKNOCK-Gm | Suicide vector; Gmr | Alexeyev (1) |

| pKNOCKfur | pKNOCK-Gm containing a 169-bp BamHI-EcoRI fragment of fur coding region; Gmr | This study |

| pBBR1MCS-4 | Expression vector; Apr | Kovach et al. (29) |

| pFur | Full-length fur coding region cloned into pBBR1MCS-4, Apr | This study |

| pUFR027lacZ | Promoter probe vector; Tcr | DeFeyter et al. (12) |

| pPfhuA-lacZ | 414-bp PCR fragment containing fhuA promoter cloned into pUFR027lacZ; Tcr | This study |

| pPkatA-lacZ | 330-bp PCR fragment containing katA promoter cloned into pUFR027lacZ; Tcr | Nakjarung et al. (40) |

| pCMA1 | pTiC58traM::nptII; Kmr | S. K. Farrand |

Gmr, Gm resistance; Tcr, Tc resistance; Apr, Ap resistance; Kmr, Km resistance.

Molecular techniques.

Unless otherwise stated, general molecular techniques were performed by using standard procedures (50). Plasmid purification was performed by using the QIAprep kit (QIAGEN). DNA was sequenced by using a BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (PE Biosystems) on an ABI 310 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Plasmids (50 to 100 ng) were transferred into A. tumefaciens strains by electroporation (9).

A. tumefaciens fur mutant construction and analysis.

The fur mutant was constructed by insertional inactivation of the fur gene on the chromosome by a single homologous recombination. The primers BT772-5′-TCAGGAATCAGCCGATCATC-3′ and BT773-5′-ATGACCACGCTGTTCTTCAG-3′, designed from the sequence of a putative fur gene (Atu0354) identified from the A. tumefaciens C58 genome sequence (64), were used to amplify a 219-bp fragment of fur coding region using Taq DNA polymerase and A. tumefaciens NTL4 genomic DNA as a template. The PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega), and the insert's nucleotide sequence was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing. Subsequently, the 169-bp BamHI-EcoRI fragment of the PCR clone was filled in with the Klenow enzyme and subcloned into pKNOCK-Gm (1), a nonreplicative plasmid in Agrobacterium, digested at the unique SmaI site. The resultant plasmid, pKNOCKfur (2.16 kb), was then transferred to A. tumefaciens by conjugation (9). Recombination of the cloned fur fragment in the suicide plasmid with the homologous counterpart on the A. tumefaciens chromosome resulted in the disruption of the fur gene. The fur mutant was selected on LB agar containing 25 μg of Cm ml−1 and 90 μg of Gm ml−1. To verify the fur mutant, Southern blot analysis was performed by using a standard protocol (50). Chromosomal DNA samples from the fur mutant and wild-type A. tumefaciens NTL4 were digested with SphI, separated, and blotted onto a nylon membrane. The blot was hybridized to 169-bp BamHI-EcoRI radioactively labeled fur probes. Probes were radioactively labeled by using a random priming kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and [α-32P]dCTP. A single hybridizing band of 0.86 kb was obtained from wild-type NTL4, as expected from the genomic sequence. In contrast, a hybridizing band of 3.02 kb was detected in the fur mutant, confirming that pKNOCKfur had correctly integrated into the fur gene. The fur mutant was named NTLfur.

Construction of full-length fur.

The full-length wild-type fur gene was amplified from A. tumefaciens NTL4 genomic DNA with the primers BT692-5′-CCAGAAGACGTGATAGACCT-3′ and BT693-5′-CGGCGTCTCAGCGTTCTTCG-3′ using Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega). The 438-bp PCR product was cloned into the unique SmaI site of an expression vector, pBBR1MCS-4 (29), creating the recombinant plasmid pFur. The cloned DNA region was confirmed by automated DNA sequencing.

Reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of sitABCD transcripts.

Bacteria grown overnight in LB medium were subcultured into fresh LB medium to give an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Exponential-phase cells (OD600 of 0.5 after incubation for 4 h) were treated with 50 μM FeCl3 or 50 μM MnCl2 for 15 min. Total RNA was extracted from untreated and treated cells by using the RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN), and the RNA samples were treated with DNase I by using the DNA-free kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Reverse transcription (converts mRNA to cDNA before PCR) was accomplished by using SuperScript II RT (Invitrogen) with reverse primer BT662 (see below) for sitA or BT1422 (see below) for 16S rRNA. Reverse-transcribed RNA sample (2 μg) from each condition was used in the PCR. Control reactions, where RT was omitted, were run in parallel to ensure there was no DNA contamination. Positive controls were performed with genomic DNA. Gene-specific primers for sitA (BT661-5′-TGATGTGACGGTGAGCGATG-3′ and BT662-5′-GGCGCCTTCGCTCGTTACCA-3′ to generate the 280-bp PCR product) and 16S rRNA (BT1421-5′-GAATCTACCCATCTCTGCGG-3′ and BT1422-5′-AAGGCCTTCATCACTCACGC-3′ to generate the 280-bp PCR product) were used for separate PCRs using the Taq PCR master mix kit (QIAGEN). PCRs were carried out with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, annealing at 58°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. RT-PCR products were visualized through gel electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining.

Sensitivity to Dipy.

Overnight cultures grown in LB medium were washed once with fresh LB medium. Cells were diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 in 5 ml of LB medium. An iron-limiting condition was achieved by adding a 300 μM concentration of the iron chelator 2,2′-dipyridyl (Dipy; Sigma). Growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 after incubation at 28°C with shaking for 24 h. The effect of addition of metal ions on bacterial growth in the presence of Dipy was assayed on LB agar plates containing 300 μM Dipy and supplemented with various metals. Cells grown on LB agar plates at 28°C for 2 days were washed and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.01 in LB medium. Tenfold serial dilutions were made. An aliquot (10 μl) of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates containing 300 μM Dipy and 100 μM concentrations of FeCl3, MnCl2, ZnCl2, or CuSO4 and then incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Cells spotted onto an LB agar plate were used as a control.

Sensitivity to SNG.

Overnight cultures were streaked on LB agar plates containing 300 μM Dipy and incubated at 28°C for 2 days. Cells were washed once with fresh LB medium. Cells (104) were treated with streptonigrin (SNG) at a concentration of 100 μg ml−1 in LB medium. SNG was prepared as a stock solution at 10 mg ml−1 in dimethyl sulfoxide. Control cells (untreated) received equivalent amounts of dimethyl sulfoxide. The cells were incubated at 28°C with shaking for 24 h and were diluted (10-fold serial dilutions). An aliquot (10 μl) of each dilution was spotted onto an LB agar plate and incubated at 28°C for 2 days. Each strain was tested in duplicate, and the experiment was repeated twice.

Siderophore analysis.

Siderophore production was analyzed using chrome azural S (CAS) agar plates (52). Solid CAS medium was made by adding 10 ml of CAS stock (52) to 100 ml of YEM medium (59) containing 1.5% agar. Overnight cultures grown in LB medium (5 μl at an OD600 of 0.1) were spotted onto YEM+CAS plates containing 50 μM FeCl3 or 200 μM Dipy, followed by incubation at 28°C for 2 days. Siderophore production is indicated by the presence of an orange halo zone around the bacteria. This occurs because siderophores produced by bacteria remove iron from the original blue CAS-Fe3+ complex contained in the plate, resulting in a change in color of the dye.

Sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide and MnCl2.

Cells grown on LB agar plates at 28°C for 2 days were washed and adjusted to an OD600 of 0.01 in LB medium. Tenfold serial dilutions were made. An aliquot (10 μl) of each dilution was spotted onto LB agar plates containing 450 μM H2O2 or 10 mM MnCl2 and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Cells spotted on an LB agar plate were used as a control. Each strain was tested in duplicate, and the experiment was repeated twice.

Construction of fhuA-lacZ fusion.

The putative fhuA promoter region was amplified from A. tumefaciens NTL4 genomic DNA with primers BT1095-5′-CGTAGCTCGAATGTATCCGC-3′ and BT1096-5′-CGCGACATAACCTTTCACCG-3′ using Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega). The 414-bp PCR product was cloned into the unique HindIII site (end-gap fill with Klenow enzyme) of the promoter probe vector pUFR027lacZ, a derivative of pUFR027 (12). The resultant recombinant plasmid was named pPfhuA-lacZ and was transferred into wild-type NTL4 and the NTLfur mutant. Bacteria grown overnight in LB medium were subcultured into fresh LB medium to give an OD600 of 0.1. Exponential-phase cells (OD600 of 0.5 after incubation for 4 h) were treated with 50 μM FeCl3 or 200 μM Dipy for 1 h. Cells were harvested and used for a β-galactosidase activity assay.

Enzyme activity assays.

Crude bacterial lysates were prepared by using bacterial suspensions in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, a protease inhibitor. Cell suspensions were lysed by brief sonication, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Clear lysates were used for total protein determination, a β-galactosidase assay, and a catalase activity assay. Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bradford Bio-Rad protein assay. The β-galactosidase assay was done as described previously (38) and was presented in units per mg of protein (U mg of protein−1). Catalase activity was monitored through the decomposition of H2O2 by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 240 nm (5). One unit of catalase was defined as the amount of enzyme capable of catalyzing the turnover of 1 μmol of substrate per min under the assay conditions.

Tumor formation assays.

A. tumefaciens strains containing pCMA1 plasmid were used to infect tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves according to the method described previously (32). Bacterial cells were grown on LB agar plates at 28°C for 2 days. The cells were washed with hormone-free MS liquid medium (39), and the cell concentration was adjusted to an OD600 of 0.01 in 20 ml of hormone-free MS medium. The cell suspensions were cocultivated with ∼0.5-cm squares of tobacco leaves (30 leaf squares for each bacterial strain) at room temperature for 10 min. Tobacco leaf pieces incubated in hormone-free MS medium without bacterial cells were used as a negative control. The tobacco leaf pieces were transferred onto hormone-free MS agar plates containing 300 μM acetosyringone and incubated at 28°C in the dark for 2 days. The tobacco leaf pieces were then transferred onto hormone-free MS agar plates containing 200 μg of timentin ml−1 and incubated at 28°C in the dark. The tumors on each leaf piece were observed after 14 days. The experiments were repeated twice.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. tumefaciens Fur.

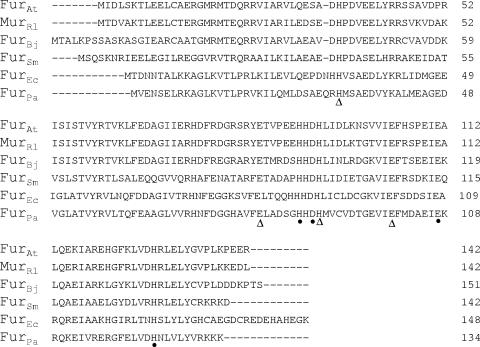

Analysis of the A. tumefaciens genome revealed three fur homologues, named fur, irr (iron response regulator), and zur (zinc uptake regulator) (64). The A. tumefaciens fur-like gene (Atu0354), furAt, is flanked upstream by a gene encoding a putative acetyltransferase (Atu0353) and downstream by plsC, a gene encoding a glycerol phosphate acyltransferase (Atu0355). The furAt gene is 429 bp long and encodes a protein of 142 amino acid residues with a deduced molecular mass of 16.7 kDa. The FurAt protein has a high degree of similarity to many Fur proteins, with the most closely related proteins from α-proteobacteria including R. leguminosarum (84%), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (68%), and S. meliloti (45%). FurAt has moderate levels of identity to Fur from γ-proteobacteria such as E. coli (37%) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (32%). The putative regulatory Fe-sensing site (S1) consisted of amino acid residues H86, D88, E107, and H124. The second binding site (S2) was a structural Zn-binding site involving H32, E80, H89, and E100. All eight of these amino acids are highly conserved among Fur proteins from many bacteria, including A. tumefaciens (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Primary sequence alignment generated by using CLUSTAL W (43) for selected proteins belonging to the Fur superfamily. Sequences shown are those from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (FurAt), Rhizobium leguminosarum (MurRl), Bradyrhizobium japonicum (FurBj), Sinorhizobium meliloti (FurSm), Escherichia coli (FurEc), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (FurPa). Sequences were from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank) and accession numbers are as follows: FurAt (NP_531060), MurRl (CAA74010), FurBj (AAC32180), FurSm (CAC47604), FurEc (NP_415209), and FurPa (AAC05679). The putative regulatory Fe-sensing site residues (S1) are indicated with circles (•), and the structural Zn-binding site residues (S2) are indicated with triangles (▵).

Fur is essential for A. tumefaciens survival under iron-limiting conditions.

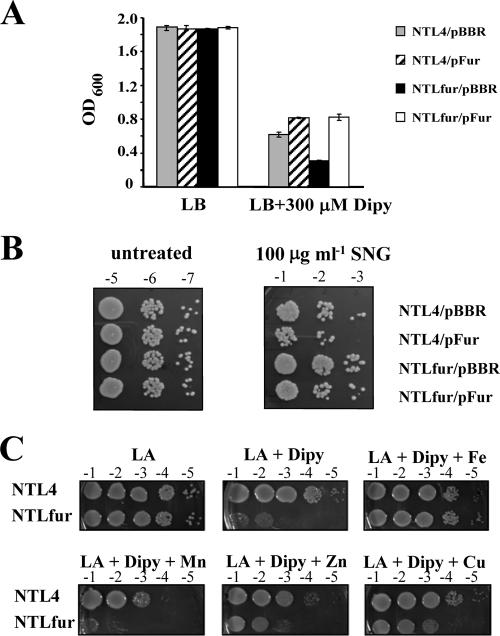

In order to determine the functional role of the fur gene in A. tumefaciens, a chromosomal fur mutant strain (NTLfur) was constructed by suicide plasmid integration into the fur gene and was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown and see Materials and Methods). First, we investigated the biological effect of fur inactivation in the response to iron by culturing NTL4 and NTLfur strains under iron-sufficient (LB) and iron-deficient (LB + 300 μM Dipy) conditions (Fig. 2A). In LB medium, NTL4 and NTLfur strains harboring the plasmid vector pBBR1MCS-4 (NTL4/pBBR and NTLfur/pBBR) or a plasmid for the expression of functional Fur (NTL4/pFur and NTLfur/pFur) showed no differences in growth. In the presence of an iron chelator Dipy (LB + 300 μM Dipy), the fur mutant had slower growth as judged by the observation that the OD600 obtained from NTLfur/pBBR (0.32 ± 0.01) was lower than the OD600 for NTL/pBBR (0.62 ± 0.02). The Dipy-sensitive phenotype of NTLfur could be complemented by expression of the functional fur on the expression vector (NTLfur/pFur). Moreover, overproduction of Fur conferred additional tolerance to Dipy, as shown by higher growth (OD600) of strains harboring pFur, NTL4/pFur (0.82 ± 0.01) and NTLfur/pFur (0.83 ± 0.02), compared to a strain harboring the vector control, NTL4/pBBR (0.62 ± 0.02), in the presence of the iron chelator. This suggests that Fur has a regulatory role in maintaining intracellular iron under iron-limiting growth conditions. However, the mechanism by which Fur regulates the process is not known.

FIG. 2.

(A) Sensitivity to Dipy (Dipy). NTL4/pBBR and NTLfur/pBBR strains are the wild type and the fur mutant, respectively, containing the plasmid vector pBBR1MCS-4. NTL4/pFur and NTLfur/pFur strains are the wild type and the fur mutant, respectively, expressing functional Fur from the plasmid pFur. Cells were grown under iron-sufficient (LB) and iron-limiting (LB + 300 μM Dipy) conditions. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD600 after incubation at 28°C with shaking for 24 h. The values presented are means, and the error bars indicate the standard deviations of three replicates. (B) Sensitivity to SNG. Cells were untreated and treated with 100 μg ml−1 of SNG at 28°C for 24 h. Cells were diluted and spotted on LB agar plates. Tenfold serial dilutions are marked above each column. (C) Effect of addition of metal ions to the growth in the presence of Dipy. Cells were diluted and spotted onto LB agar plates containing 300 μM Dipy and 100 μM concentrations of either FeCl3, MnCl2, ZnCl2, or CuSO4 and then incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Cells spotted onto an LB agar plate (LA) were used as a control.

Levels of FurAt affect cellular iron concentrations.

The hypersensitivity of NTLfur to Dipy led us to ask whether fur has an effect on cellular iron concentrations. SNG has been used to assess free iron levels in bacterial cells (16, 53, 63). SNG is an aminoquinone that is capable of cyclic reduction and oxidation inside bacteria to produce superoxide and hydroxyl radicals which damage cells (21, 25). The availability of intracellular iron is an important factor in the action of SNG. Increased sensitivity to SNG was shown to correlate with an increase in the levels of intracellular free iron (62, 66). Relative intracellular iron levels in NTL4 and the NTLfur mutant were assessed by SNG sensitivity assays. Cells grown under the iron-deficient condition (LB agar plates containing 300 μM Dipy) for 2 days were used for SNG sensitivity assays (see Materials and Methods). The results in Fig. 2B show that untreated cells exhibited similar viability. However, the NTLfur/pBBR mutant had greater tolerance to 100 μg ml−1 of SNG treatment than wild-type NTL4/pBBR. These data provided evidence that the fur mutant has lower levels of intracellular free iron relative to levels in the wild-type. Another possible explanation for increased resistance to SNG could be the overproduction of superoxide dismutase (SOD) (21). The A. tumefaciens genome contains three sod-like genes (Atu0876, Atu4583, and Atu4726) (64). Identification of SOD isozymes by selective inhibition with KCN or H2O2 revealed that all three SOD isozymes were Fe-SODs (unpublished data). Moreover, SOD activity gel staining assays showed that NTL4/pBBR and NTLfur/pBBR had similar levels of SOD activity (data not shown). Thus, increased resistance of the NTLfur mutant to SNG was not due to the overproduction of SOD enzymes. Complementation of the mutant by overproduction of functional Fur from the plasmid pFur, NTLfur/pFur, could restore SNG sensitivity to a similar level as that of wild-type NTL4/pBBR. These results suggested that levels of FurAt affected cellular iron concentrations. Further evidence supports this: overproduction of functional Fur in the wild-type background, NTL4/pFur, enhanced sensitivity to SNG compared to NTL4/pBBR.

Dipy is known to sequester external iron, as well as intracellular labile Fe2+ pool and possibly other metal ions. We further sought to determine whether the increased sensitivity to Dipy in the NTLfur mutant was primarily due to iron starvation and not other metals. The effect of the addition of metal ions (100 μM FeCl3, MnCl2, ZnSO4, and CuSO4) on the growth on LB agar plates containing 300 μM Dipy of NTLfur compared to wild-type NTL4 was investigated. The results showed that only the addition of iron complemented the Dipy-sensitive phenotype of NTLfur and restored the growth of NTLfur to similar levels of wild-type NTL4 (LA + Dipy + Fe) (Fig. 2C). These data clearly demonstrated that the growth defect of NTLfur in the presence of Dipy was iron specific and that the loss of fur led to iron deficiency in NTLfur.

Inactivation of fur in most bacteria leads to increased expression of genes involved in iron uptake and transport (2, 53, 57). Hence, these mutants are overloaded with iron. Thus, the iron deficiency of the A. tumefaciens fur mutant makes it different from typical bacterial fur mutants.

Fur is not the iron-responsive regulator of the siderophore biosynthesis and transport genes in A. tumefaciens.

Siderophores are ferric-ion-chelating molecules synthesized and secreted by bacteria growing under low-iron stress. In many bacteria, synthesis of siderophores is negatively regulated by iron and the Fur protein. One of the common phenotypes in fur mutants is the loss of iron-mediated regulation of siderophore synthesis, resulting in overproduction or constitutive secretion of siderophores (26, 27, 33, 53, 54). To determine whether the furAt mutation affects siderophore biosynthesis, production of siderophores by the NTLfur mutant was compared to that of the wild-type NTL4 on YEM+CAS plates under iron-replete (50 μM FeCl3) and -depleted (200 μM Dipy) conditions. As shown in Fig. 3A, wild-type NTL4 and mutant NTLfur did not produce siderophores under iron-replete conditions. Both strains produced siderophores only under iron-limiting conditions (Fig. 3B), as indicated by the halo zones. In addition, the sizes of the halo zones surrounding the bacterial colonies were similar for the two strains. This indicated that iron-mediated regulation of siderophore synthesis was normally maintained in the NTLfur mutant, as in the wild-type NTL4; therefore, fur is not involved in iron regulation of siderophore production in A. tumefaciens.

FIG. 3.

Effect of the fur mutation on siderophore production. Analysis of siderophore production was performed using siderophore indicator CAS agar plates. Wild-type NTL4 and mutant NTLfur strains were spotted onto YEM+CAS agar plates containing 50 μM FeCl3 (A) or 200 μM Dipy (B) and incubated at 28°C for 2 days. The halo zone surrounding bacteria indicates the production of siderophores.

To investigate a potential role for FurAt in iron regulation of the outer membrane siderophore receptor, expression of fhuA from the fhuA-lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid (pPfhuA-lacZ) was monitored in wild-type and fur mutant backgrounds. β-Galactosidase activities were measured from wild-type NTL4 and the NTLfur mutant containing pPfhuA-lacZ grown under iron-replete (LB + 50 μM FeCl3) and iron-depleted (LB + 200 μM Dipy) conditions. The levels of β-galactosidase activity from wild-type NTL4/pPfhuA-lacZ and mutant NTLfur/pPfhuA-lacZ were higher when cells were grown under the iron-depleted condition (382 ± 24 and 380 ± 25 U mg of protein−1, respectively). The expression of fhuA was reduced under the iron-replete condition in both wild-type NTL4/pPfhuA-lacZ and mutant NTLfur/pPfhuA-lacZ backgrounds (249 ± 21 and 220 ± 10 U mg of protein−1, respectively). The iron-controlled expression of fhuA was similar in the wild-type and in the fur mutant, indicating that iron-regulated fhuA expression was not mediated by FurAt. The finding that mutation of fur does not affect siderophore biosynthesis and transport genes is not unique to A. tumefaciens. Similar findings have been reported for the rhizobia R. leguminosarum (61) and S. meliloti (10), where instead of Fur, the RirA proteins have been shown to regulate siderophore biosynthesis and transport genes (56, 58). A homologue of rirA (Atu0201) is also present in the A. tumefaciens genome (64); however, its functions have not been studied. Although A. tumefaciens Fur is not the dominant regulator of iron transport and siderophore synthesis (Fig. 3), we show here that Fur is important for survival under iron-limiting conditions (Fig. 2A).

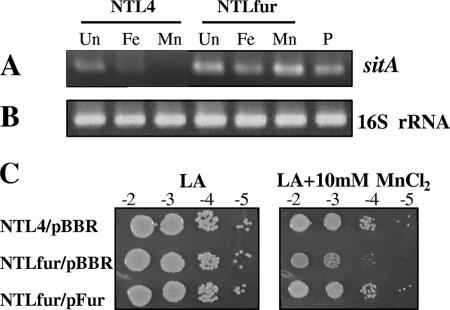

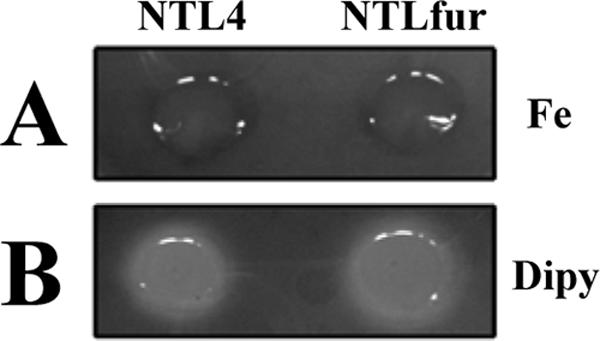

FurAt is the repressor of sitA.

It has been reported that MurRl and FurSm function in response to manganese by repressing transcription of the sitABCD operon, which encodes a Mn2+ uptake system, under manganese-replete conditions (10, 14, 44). Analysis of the A. tumefaciens genome revealed a putative sitABCD operon (Atu4471, Atu4470, Atu4469, and Atu4468, respectively). To determine the role of FurAt in the regulation of sitABCD expression, RT-PCR was used to analyze the expression of sitA in RNA samples isolated from NTL4 and NTLfur grown in the absence or presence of metals (Fig. 4). 16S rRNA was used as a loading control and to quantitate the amount of RNA in RT-PCRs. Unlike the 16S rRNA RT-PCR products (Fig. 4B), the amount of sitA RT-PCR products differed depending on the various culture conditions (Fig. 4A). Expression of sitA in NTL4 was detectable in untreated cells, and the addition of 50 μM manganese fully repressed sitA expression. Similarly, the addition of 50 μM iron greatly reduced, but did not abolish, the expression of sitA. Regulation of sitA expression by iron and manganese was lost in the NTLfur mutant, resulting in constitutively high expression of sitA in the presence of iron or manganese. These data indicated that FurAt is involved in metal-dependent repression of sitA. In S. meliloti, the mnt (sit) operon is repressed strongly by Mn2+ and moderately by Fe2+. The Mn2+-mediated repression of the mntABCD operon is Fur dependent, whereas the Fe2+-mediated repression is only partially affected by Fur (10). In regulation of the sitABCD operon, MurRl has been shown to bind the 7-N7-7 inverted repeats, instead of the conventional E. coli Fur box, within the sitABCD promoter region called the Mur-responsive sequence (MRS1 [TGCAATT-N7-AATTGCA] and MRS2 [TGCAAAT-N7-AATCGCA] separated by 16 bp) (15). MRS-like motifs, MRS1 (TGGTATT-N7-AATCGCA) and MRS2 (TTAAATT-N7-ATTTGCA) separated by 31 bp, are also found in the putative promoter region of the A. tumefaciens sitABCD operon. This suggests that FurAt senses manganese and directly regulates the sitABCD operon by a mechanism similar to that of MurRl. However, the R. leguminosarum sitABCD operon is repressed by manganese but not iron (14). Thus, regulation of the sit operon in A. tumefaciens shares similarity with the operon's regulation in S. meliloti but differs from that in R. leguminosarum.

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR was used to analyze the mRNA levels for the sitA gene (A) and 16S rRNA (B). RNA samples were isolated from wild-type NTL4 and mutant NTLfur culture untreated (Un) or treated with 50 μM FeCl3 (Fe) and 50 μM MnCl2 (Mn) for 15 min. P, positive controls were performed with genomic DNA. (C) Sensitivity to MnCl2. Cells were diluted and spotted onto an LB agar plate containing 10 mM MnCl2 and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Cells spotted on an LB agar plate (LA) were used as a control. NTL4/pBBR and NTLfur/pBBR strains are the wild type and the fur mutant, respectively, expressing the plasmid vector pBBR1MCS-4. NTLfur/pFur is the fur mutant expressing functional Fur from the plasmid pFur.

In other bacteria inactivation of fur genes leads to the derepression of iron uptake and transport genes, resulting in iron overload in the cells. Whereas the A. tumefaciens fur mutant was unable to utilize iron under iron-depleted conditions (Fig. 2) and showed derepression of the manganese uptake sit operon (Fig. 4A), we tested whether inactivation of fur affected the sensitivity of A. tumefaciens to manganese. Wild-type NTL4 and the NTLfur mutant were grown on an LB agar plate containing 10 mM MnCl2. The results showed that NTLfur/pBBR was apparently more sensitive to manganese than was wild-type NTL4/pBBR (Fig. 4C). These data suggested the loss of control of manganese transport and manganese overload in the NTLfur mutant, resulting in manganese toxicity, at least due to the constitutive up-expression of the sit operon. The manganese-sensitive phenotype of NTLfur could be complemented by expression of the functional fur on the expression vector (NTLfur/pFur) (Fig. 4C). This further confirmed that A. tumefaciens Fur has a regulatory role in maintaining intracellular manganese concentrations.

It is becoming increasingly clear that in some members of the α-proteobacteria such as A. tumefaciens and rhizobia, Fur-like proteins have evolved to respond to manganese, and yet the regulator does not serve as a typical global regulator of iron-responsive genes (10, 14, 44).

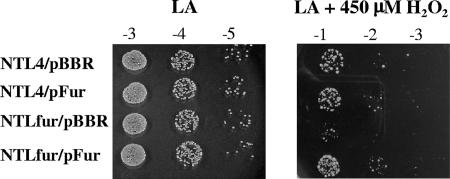

The NTLfur mutant is hypersensitive to hydrogen peroxide and exhibits reduced catalase activity.

Increased production and accumulation of ROS such as H2O2, superoxides, and organic peroxides are part of the initial plant defense response against microbial invasion (3). Intracellular iron concentrations also have a crucial role in the cell's oxidative stress levels. The role of Fur in the response of A. tumefaciens to H2O2 was determined. NTLfur/pBBR was more sensitive than NTL4/pBBR to 450 μM H2O2 (Fig. 5). Expression of a functional fur gene in the mutant could complement the H2O2-hypersensitive phenotype, as shown by similarity in the H2O2 resistance levels between NTLfur/pFur and NTL4/pBBR. Nonetheless, overproduction of Fur in NTL4 did not confer additional resistance to H2O2 (Fig. 5). These data confirmed that disruption of fur was responsible for the H2O2-hypersensitive phenotype, indicating an important role for FurAt in the response to oxidative stress.

FIG. 5.

Sensitivity to H2O2. Cells were diluted and spotted onto LB agar plates containing 450 μM H2O2 and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. Tenfold serial dilutions are marked above each column. Cells spotted onto an LB agar plate (LA) were used as a control. NTL4/pBBR and NTLfur/pBBR strains are the wild type and the fur mutant, respectively, expressing the plasmid vector pBBR1MCS-4. NTL4/pFur and NTLfur/pFur strains are the wild type and the fur mutant, respectively, expressing functional Fur from the plasmid pFur.

We have shown that catalase is the major H2O2 detoxification enzyme responsible for H2O2 resistance levels in A. tumefaciens (45). Hence, catalase levels were determined in NTLfur. NTLfur (6.9 ± 0.2 U mg of protein−1) had 30% lower total catalase activity than NTL4 (9.8 ± 0.6 U mg of protein−1). This indicates that the increased H2O2 sensitivity phenotype of NTLfur was due to the reduction in total catalase activity. There are two catalase genes in A. tumefaciens, the major catalase encoded by katA, which is the enzyme responsible for H2O2 resistance, and a minor stationary-phase catE (45). The role of Fur in the regulation of katA expression was investigated by using a katA promoter fused to a reporter lacZ on a plasmid (pPkatA-lacZ) (40) in NTL4 and NTLfur. The β-galactosidase activity obtained from NTLfur/pPkatA-lacZ (9,609 ± 293 U mg of protein−1) was 20% lower than the activity in NTL4/pPkatA-lacZ (12,212 ± 389 U mg of protein−1). The data show that the decrease in catalase levels in the NTLfur mutant resulted from decreased katA expression. This suggests that katA expression is either directly or indirectly regulated by Fur. The promoter region of the katA gene contains a potential Fur-binding site (GTGGATGATCATCGGCATC), which matches the E. coli Fur box at 12 of 19 positions; however, there is no sequence resembling the MRS-like motif found in the sit operon promoter. Although the levels of total catalase in the NTLfur were about 30% reduced compared to wild-type NTL4 levels, NTLfur had increased sensitivity to H2O2. These findings imply that catalase is the major component involved in H2O2 resistance of A. tumefaciens.

The NTLfur mutant has reduced virulence.

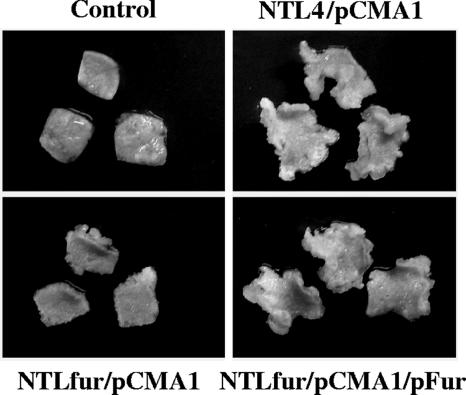

In many pathogenic bacteria, fur mutants have a reduced-virulence phenotype (27, 42, 47). Among plant pathogens, mutations in the fur genes of Erwinia chrysanthemi (18) and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (53) led to attenuated virulence. A. tumefaciens induces the formation of crown gall tumors by transferring T-DNA from the bacterium's tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into host plant cells. We tested whether fur is important in A. tumefaciens virulence by assessing the ability of various mutants to form tumors on tobacco leaf discs. Tobacco leaf pieces were infected with either NTL4 or NTLfur containing the pCMA1 plasmid. A. tumefaciens strains lacking the pCMA1 plasmid were not able to cause tumors on tobacco leaves (data not shown). The results in Fig. 6 show that NTLfur/pCMA1 was significantly less virulent than the wild-type strain NTL4/pCMA1. The tumors that formed on tobacco leaf pieces infected with NTLfur/pCMA1 were much fewer and smaller than those caused by NTL4/pCMA1. Furthermore, the attenuated virulence of the NTLfur/pCMA1 mutant could be complemented by pFur, as shown by the fact that the tumor-inducing ability of NTLfur/pCMA1/pFur was completely restored to NTL4/pCMA1 levels (Fig. 6). A control, NTLfur/pCMA1/pBBR1MCS-4, did not exhibit complementation of the reduced-virulence phenotype of the mutant (data not shown). These results confirmed that inactivation of fur was responsible for the attenuated virulence and that A. tumefaciens fur is important in the bacterium's pathogenesis on a plant host.

FIG. 6.

Virulence assay. Tumor formation was determined on tobacco leaf squares infected with A. tumefaciens wild-type NTL4 or mutant NTLfur containing the pCMA1 plasmid (NTL4/pCMA1 and NTLfur/pCMA1, respectively). The NTLfur mutant was complemented by expression of functional Fur from the plasmid pFur (NTLfur/pCMA1/pFur). Control refers to tobacco leaf squares without infection. Representative leaf pieces (from n = 30) are shown.

The A. tumefaciens fur mutant (NTLfur) was highly attenuated in virulence on tobacco leaves (Fig. 6). In some organisms, Fur plays a role in resistance to low pH (6, 22, 60). It is known that a wounded plant cell is an acidic environment. It is possible that the reduced virulence of the NTLfur mutant could result from decreased acid tolerance. We therefore examined the ability of the NTLfur mutant to grow under acidic conditions. The growth rates of the NTLfur mutant in IB medium (pH 5.5), which has been shown to resemble the bacterial growth condition in plant tissues (30), and in MS medium (pH 5.5) (39) were compared to the growth rates of wild-type NTL4 by measuring the OD600. The NTLfur mutant had growth rates similar to those of NTL4 in both media (data not shown). Thus, the attenuated phenotype was not due to the mutant's inability to grow at lower pH. A. tumefaciens fur has regulatory roles in the response to iron starvation and oxidative stress. Inactivation of the furAt gene caused cells to become more sensitive to iron limitation (Fig. 2A) and H2O2 (Fig. 5). This suggests that the virulence deficiency of the NTLfur mutant could be due, at least in part, to an impaired ability to cope with the iron-restricted and oxidative stress conditions which are an important component of the plant defense response to microbial infection.

Previous analyses of fur from other α-proteobacteria suggest that the gene has almost no physiological role in iron homeostasis (10, 14, 44, 61). The role of Fur-like proteins seems to be restricted to the regulation of manganese uptake gene, and thus Fur was renamed Mur (10, 14). Recently, comparative genomics and computational approaches were used to establish the iron and manganese regulatory network in α-proteobacteria (48). The results showed that, in the Rhizobiales and Rhodobacteraceae, Fur-like proteins evolved to become a regulator of the manganese uptake systems in response to manganese concentrations and thus had become Mur. In these two lineages, the role of Fur in regulating iron homeostasis was taken by RirA and Irr, and this had been confirmed experimentally in R. leguminosarum and S. meliloti (11, 55, 56, 58). Furthermore, genome scanning for RirA-box (IRO), Irr-box (ICE), and Fur/Mur-box (MRS) in the upstream regions of genes involved in iron and manganese homeostasis led to identification of candidates for the RirA, Irr, and Fur/Mur regulons. Analysis of the A. tumefaciens genome revealed that the iron regulatory motifs IRO and ICE were found in most genes involved in iron uptake, storage, and usage (48). These imply that, instead of Fur, RirA and Irr have a major role in controlling iron homeostasis in A. tumefaciens. There were only two manganese transporter systems, sitABCD and mntH, which were predicted to be members of the Fur (Mur) regulon in A. tumefaciens (48). Here, we show that FurAt is the repressor of the sit operon (Fig. 4A). Nonetheless, FurAt has a regulatory role under iron-limiting conditions (Fig. 2A) through an as-yet-unidentified mechanism(s). Inactivation of furAt leads to multiple changes in the cellular phenotypes, suggesting that Fur has global regulatory functions involving gene regulation in many pathways from iron and manganese homeostasis to oxidative stress response. Physiologically, the most important defect in the fur mutant is its inability to form tumors on a plant host. This suggests that the regulation of metal homeostasis and oxidative response are crucial during plant-microbe interactions and subsequent disease progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. K. Farrand for the plasmid pCMA1.

This study was supported by a Research Scholar Grant (TRG4780004) from the Thailand Research Fund to R.S., a Research Team Strengthening Grant from the BIOTEC to S.M., and a grant from the ESTM through the Higher Education Development Project of the Ministry of Education.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 1 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexeyev, M. F. 1999. The pKNOCK series of broad-host-range mobilizable suicide vectors for gene knockout and targeted DNA insertion into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. BioTechniques 26:824-826, 828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews, S. C., A. K. Robinson, and F. Rodriguez-Quinones. 2003. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 27:215-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker, C. J., and E. W. Orlandi. 1995. Active oxygen in plant pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 33:299-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barton, H. A., Z. Johnson, C. D. Cox, A. I. Vasil, and M. L. Vasil. 1996. Ferric uptake regulator mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with distinct alterations in the iron-dependent repression of exotoxin A and siderophores in aerobic and microaerobic environments. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1001-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beers, R. F., Jr., and I. W. Sizer. 1952. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the break down of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195:133-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bijlsma, J. J., B. Waidner, A. H. Vliet, N. J. Hughes, S. Hag, S. Bereswill, D. J. Kelly, C. M. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, M. Kist, and J. G. Kusters. 2002. The Helicobacter pylori homologue of the ferric uptake regulator is involved in acid resistance. Infect. Immun. 70:606-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, V. 1995. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the gram-negative outer membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 16:295-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calderwood, S. B., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Iron regulation of Shiga-like toxin expression in Escherichia coli is mediated by the fur locus. J. Bacteriol. 169:4759-4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cangelosi, G. A., E. A. Best, G. Martinetti, and E. W. Nester. 1991. Genetic analysis of Agrobacterium. Methods Enzymol. 204:384-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chao, T. C., A. Becker, J. Buhrmester, A. Puhler, and S. Weidner. 2004. The Sinorhizobium meliloti fur gene regulates, with dependence on Mn(II), transcription of the sitABCD operon, encoding a metal-type transporter. J. Bacteriol. 186:3609-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao, T. C., J. Buhrmester, N. Hansmeier, A. Puhler, and S. Weidner. 2005. Role of the regulatory gene rirA in the transcriptional response of Sinorhizobium meliloti to iron limitation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5969-5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeFeyter, R., C. I. Kado, and D. W. Gabriel. 1990. Small, stable shuttle vectors for use in Xanthomonas. Gene 88:65-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delany, I., R. Rappuoli, and V. Scarlato. 2004. Fur functions as an activator and as a repressor of putative virulence genes in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1081-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Mireles, E., M. Wexler, G. Sawers, D. Bellini, J. D. Todd, and A. W. Johnston. 2004. The Fur-like protein Mur of Rhizobium leguminosarum is a Mn2+-responsive transcriptional regulator. Microbiology 150:1447-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz-Mireles, E., M. Wexler, J. D. Todd, D. Bellini, A. W. Johnston, and R. G. Sawers. 2005. The manganese-responsive repressor Mur of Rhizobium leguminosarum is a member of the Fur-superfamily that recognizes an unusual operator sequence. Microbiology 151:4071-4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elgrably-Weiss, M., S. Park, E. Schlosser-Silverman, I. Rosenshine, I. Imlay, and S. Altuvia. 2002. A Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium hemA mutant is highly susceptible to oxidative DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 184:3774-3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ernst, F. D., G. Homuth, J. Stoof, U. Mader, B. Waidner, E. J. Kuipers, M. Kist, J. G. Kusters, S. Bereswill, and A. H. van Vliet. 2005. Iron-responsive regulation of the Helicobacter pylori iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase SodB is mediated by Fur. J. Bacteriol. 187:3687-3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franza, T., C. Sauvage, and D. Expert. 1999. Iron regulation and pathogenicity in Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937: role of the Fur repressor protein. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 12:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman, Y. E., and M. R. O'Brian. 2004. The ferric uptake regulator (Fur) protein from Bradyrhizobium japonicum is an iron-responsive transcriptional repressor in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 279:32100-32105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg, M. B., S. A. Boyko, and S. B. Calderwood. 1991. Positive transcriptional regulation of an iron-regulated virulence gene in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:1125-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gregory, E. M., and I. Fridovich. 1973. Oxygen toxicity and the superoxide dismutase. J. Bacteriol. 114:1193-1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall, H. K., and J. W. Foster. 1996. The role of fur in the acid tolerance response of Salmonella typhimurium is physiologically and genetically separable from its role in iron acquisition. J. Bacteriol. 178:5683-5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamza, I., S. Chauhan, R. Hassett, and M. R. O'Brian. 1998. The bacterial irr protein is required for coordination of heme biosynthesis with iron availability. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21669-21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamza, I., N. D. King, and M. R. O'Brian. 2000. Fur-independent regulation of iron metabolism by Irr in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Microbiology 146:669-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassett, D. J., B. E. Britigan, T. Svendsen, G. M. Rosen, and M. S. Cohen. 1987. Bacteria form intracellular free radicals in response to paraquat and streptonigrin. Demonstration of the potency of hydroxyl radical. J. Biol. Chem. 262:13404-13408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassett, D. J., P. A. Sokol, M. L. Howell, J. F. Ma, H. T. Schweizer, U. Ochsner, and M. L. Vasil. 1996. Ferric uptake regulator (Fur) mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa demonstrate defective siderophore-mediated iron uptake, altered aerobic growth, and decreased superoxide dismutase and catalase activities. J. Bacteriol. 178:3996-4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horsburgh, M. J., E. Ingham, and S. J. Foster. 2001. In Staphylococcus aureus, Fur is an interactive regulator with PerR, contributes to virulence, and is necessary for oxidative stress resistance through positive regulation of catalase and iron homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 183:468-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Imlay, J. A., S. M. Chin, and S. Linn. 1988. Toxic DNA damage by hydrogen peroxide through the Fenton reaction in vivo and in vitro. Science 240:640-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kovach, M. E., P. H. Elzer, D. S. Hill, G. T. Robertson, M. A. Farris, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, L., Y. Li, T. M. Lim, and S. Q. Pan. 1999. GFP-aided confocal laser scanning microscopy can monitor Agrobacterium tumefaciens cell morphology and gene expression associated with infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litwin, C. M., and S. B. Calderwood. 1993. Role of iron in regulation of virulence genes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6:137-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, P., D. Wood, and E. W. Nester. 2005. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase is an acid-induced, chromosomally encoded virulence factor in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J. Bacteriol. 187:6039-6045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loprasert, S., R. Sallabhan, W. Whangsuk, and S. Mongkolsuk. 2000. Characterization and mutagenesis of fur gene from Burkholderia pseudomallei. Gene 254:129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masse, E., F. E. Escorcia, and S. Gottesman. 2003. Coupled degradation of a small regulatory RNA and its mRNA targets in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 17:2374-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masse, E., and S. Gottesman. 2002. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4620-4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mey, A. R., E. E. Wyckoff, V. Kanukurthy, C. R. Fisher, and S. M. Payne. 2005. Iron and fur regulation in Vibrio cholerae and the role of fur in virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:8167-8178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mila, I., A. Scalbert, and D. Expert. 1996. Iron withholding by plant polyphenols and resistance to pathogens and rots. Phytochemistry 42:1551-1555. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 39.Murashige, T., and F. Skoog. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue culture. Plant Physiol. 15:473-496. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakjarung, K., S. Mongkolsuk, and P. Vattanaviboon. 2003. The oxyR from Agrobacterium tumefaciens: evaluation of its role in the regulation of catalase and peroxide responses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304:41-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neema, C., J. P. Laulhere, and D. Expert. 1993. Iron deficiency induced by chrysobactin in Saintpaulia leaves inoculated with Erwinia chrysanthemi. Plant Physiol. 102:967-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palyada, K., D. Threadgill, and A. Stintzi. 2004. Iron acquisition and regulation in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 186:4714-4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson, W. R. 1990. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 183:63-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Platero, R., L. Peixoto, M. R. O'Brian, and E. Fabiano. 2004. Fur is involved in manganese-dependent regulation of mntA (sitA) expression in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4349-4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prapagdee, B., W. Eiamphungporn, P. Saenkham, S. Mongkolsuk, and P. Vattanaviboon. 2004. Analysis of growth phase regulated KatA and CatE and their physiological roles in determining hydrogen peroxide resistance in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237:219-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qi, Z., and M. R. O'Brian. 2002. Interaction between the bacterial iron response regulator and ferrochelatase mediates genetic control of heme biosynthesis. Mol. Cell 9:155-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rea, R. B., C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 2004. Disruption of putative regulatory loci in Listeria monocytogenes demonstrates a significant role for Fur and PerR in virulence. Infect. Immun. 72:717-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodionov, D. A., M. S. Gelfand, J. D. Todd, A. R. Curson, and A. W. Johnston. 2006. Computational reconstruction of iron- and manganese-responsive transcriptional networks in alpha-proteobacteria. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2:1568-1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolph, G., G. Semini, F. Hauser, A. Lindemann, M. Friberg, H. Hennecke, and H. M. Fischer. 2006. The iron control element, acting in positive and negative control of iron-regulated Bradyrhizobium japonicum genes, is a target for the Irr protein. J. Bacteriol. 188:733-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 51.Scalbert, A. 1991. Antimicrobial properties of tannins. Phytochemistry 30:3875-3883. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwyn, B., and J. B. Neilands. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Subramoni, S., and V. S. Ramesh. 2005. Growth deficiency of a Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae fur mutant in rice leaves is rescued by ascorbic acid supplementation. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 18:644-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson, D. K., A. S. Beliaev, C. S. Giometti, S. L. Tollaksen, T. Khare, D. P. Lies, K. H. Nealson, H. Lim, J. Yates III, C. C. Brandt, J. M. Tiedje, and J. Zhou. 2002. Transcriptional and proteomic analysis of a ferric uptake regulator (fur) mutant of Shewanella oneidensis: possible involvement of fur in energy metabolism, transcriptional regulation, and oxidative stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:881-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Todd, J. D., G. Sawers, D. A. Rodionov, and A. W. Johnston. 2006. The Rhizobium leguminosarum regulator IrrA affects the transcription of a wide range of genes in response to Fe availability. Mol. Gen. Genomics 275:564-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Todd, J. D., M. Wexler, G. Sawers, K. H. Yeoman, P. S. Poole, and A. W. Johnston. 2002. RirA, an iron-responsive regulator in the symbiotic bacterium Rhizobium leguminosarum. Microbiology 148:4059-4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Touati, D., M. Jacques, B. Tardat, L. Bouchard, and S. Despied. 1995. Lethal oxidative damage and mutagenesis are generated by iron in delta fur mutants of Escherichia coli: protective role of superoxide dismutase. J. Bacteriol. 177:2305-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viguier, C., P. O. Cuiv, P. Clarke, and M. O'Connell. 2005. RirA is the iron response regulator of the rhizobactin 1021 biosynthesis and transport genes in Sinorhizobium meliloti 2011. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 246:235-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vincent, J. M. 1970. A manual for the practical study of root nodule bacteria. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 60.Waidner, B., S. Greiner, S. Odenbreit, H. Kavermann, J. Velayudhan, F. Stahler, J. Guhl, E. Bisse, A. H. van Vliet, S. C. Andrews, J. G. Kusters, D. J. KellY, R. Haas, M. Kist, and S. Bereswill. 2002. Essential role of ferritin Pfr in Helicobacter pylori iron metabolism and gastric colonization. Infect. Immun. 70:3923-3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wexler, M., J. D. Todd, O. Kolade, D. Bellini, A. M. Hemmings, G. Sawers, and A. W. Johnston. 2003. Fur is not the global regulator of iron uptake genes in Rhizobium leguminosarum. Microbiology 149:1357-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White, J. R., and H. N. Yeowell. 1982. Iron enhances the bactericidal action of streptonigrin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 106:407-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson, T. J., N. Bertrand, J. L. Tang, J. X. Feng, M. Q. Pan, C. E. Barber, J. M. Dow, and M. J. Daniels. 1998. The rpfA gene of Xanthomonas campestris pathovar campestris, which is involved in the regulation of pathogenicity factor production, encodes an aconitase. Mol. Microbiol. 28:961-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wood, D. W., J. C. Setubal, R. Kaul, D. E. Monks, J. P. Kitajima, V. K. Okura, Y. Zhou, L. Chen, G. E. Wood, N. F. Almeida, Jr., L. Woo, Y. Chen, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, P. D. Karp, D. Bovee, Sr., P. Chapman, J. Clendenning, G. Deatherage, W. Gillet, C. Grant, T. Kutyavin, R. Levy, M. J. Li, E. McClelland, A. Palmieri, C. Raymond, G. Rouse, C. Saenphimmachak, Z. Wu, P. Romero, D. Gordon, S. Zhang, H. Yoo, Y. Tao, P. Biddle, M. Jung, W. Krespan, M. Perry, B. Gordon-Kamm, L. Liao, S. Kim, C. Hendrick, Z. Y. Zhao, M. Dolan, F. Chumley, S. V. Tingey, J. F. Tomb, M. P. Gordon, M. V. Olson, and E. W. Nester. 2001. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science 294:2317-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang, J., H. R. Panek, and M. R. O'Brian. 2006. Oxidative stress promotes degradation of the Irr protein to regulate haem biosynthesis in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol. Microbiol. 60:209-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yeowell, H. N., and J. White. 1982. Iron requirement in the bactericidal mechanism of streptonigrin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:961-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ziemienowicz, A. 2001. Odyssey of Agrobacterium T-DNA. Acta Biochim. Pol. 48:623-635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]