Abstract

Pertussis is an infectious disease of the respiratory tract that is caused by the gram-negative bacterium Bordetella pertussis. Although acellular pertussis (aP) vaccines are safe, they are not fully effective and thus require improvement. In contrast to whole-cell pertussis (wP) vaccines, aP vaccines do not contain lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and Neisseria meningitidis LpxL2 LPS have been shown to display immune-stimulating activity while exerting little endotoxin activity. Therefore, we evaluated whether these LPS analogs could increase the efficacy of the aP vaccine. Mice were vaccinated with diphtheria-tetanus-aP vaccine with aluminum, MPL, or LpxL2 LPS adjuvant before intranasal challenge with B. pertussis. Compared to vaccination with the aluminum adjuvant, vaccination with either LPS analog resulted in lower colonization and a higher pertussis toxin-specific serum immunoglobulin G level, indicating increased efficacy. Vaccination with either LPS analog resulted in reduced lung eosinophilia, reduced eosinophil numbers in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and the ex vivo production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) by bronchial lymph node cells and IL-5 by spleen cells, suggesting reduced type I hypersensitivity. Vaccination with either LPS analog increased serum IL-6 levels, although these levels remained well below the level induced by wP, suggesting that supplementation with LPS analogs may induce some reactogenicity but reactogenicity considerably less than that induced by the wP vaccine. In conclusion, these results indicate that supplementation with LPS analogs forms a promising strategy that can be used to improve aP vaccines.

Pertussis is caused by Bordetella pertussis infection of the respiratory tract and is among the 10 infectious diseases with the highest rates of morbidity and mortality worldwide. After introduction of whole-cell pertussis (wP) vaccines in the 1950s, the incidence of pertussis has decreased significantly. Although they are efficacious, wP vaccines were found to be reactogenic, leading to concerns about their safety in the 1970s. Therefore, acellular pertussis (aP) vaccines that comprise purified B. pertussis proteins have been developed. In many countries, pertussis has recently reemerged, despite the high rates of vaccine coverage (13). Several approaches to reducing disease incidence and severity have been suggested, one of them being the improvement of the existing aP vaccines.

In contrast to wP vaccines, aP vaccines are devoid of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). By engaging Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), this molecule induces Th1 adaptive immunity (12, 15, 22, 29, 39). Consequently, concerns have been raised with respect to the relative efficacies of aP vaccines compared with those of wP vaccines as well as those of simultaneously administered vaccines, such as diphtheria, tetanus, polio, and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccines. In fact, this concern has been substantiated by an increase in the incidence of invasive Hib disease in the United Kingdom that coincided with the distribution of combination vaccines that contain aP vaccine instead of wP vaccine (28). Thus, while the reactogenicity of LPS precludes its use, its adjuvanticity is, regrettably, missed.

We and others have shown that LPS is an essential component of wP vaccines in mice, as wP-vaccinated C3H/HeJ mice that have a point mutation in the Tlr4 gene, which results in defective signal transduction, failed to clear a B. pertussis challenge (21; H. A. Banus et al., unpublished data). This result underlines the important role of LPS in generating a productive immune response, at least in mice. Additionally, we have shown that a functional polymorphism in TLR4 was associated with reduced pertussis toxin (Ptx)-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) titers in wP-vaccinated children 1 year of age (H. A. Banus et al., submitted for publication). Together, these findings strongly suggest an important role of LPS in wP vaccines.

To make use of this role of LPS, the development and use of LPS derivatives and novel LPS species have been investigated. The nontoxic LPS derivative monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) engages TLR4 (17, 33), inducing Th1 adaptive immunity and changing Th2-directed responses to Th1-directed responses (3, 34, 38, 48). MPL combined with aluminum (denoted AS04) is registered for clinical use as an adjuvant in viral vaccines, such as the hepatitis B virus vaccine (6) and the human papillomavirus vaccine (18), while MPL combined with l-tyrosine is registered for clinical use as an adjuvant in allergy therapy (2, 27). Furthermore, a Neisseria meningitidis strain deficient for the late acyltransferase LpxL2 displayed a strongly decreased endotoxic activity when it was tested for its ability to stimulate human macrophages (46). This mutant LPS still exhibited immune-stimulating activity (46).

In mice, Tlr4 is critical for the clearance of B. pertussis and the ensuing adaptive immunity (4, 20, 25). The engagement of this receptor by MPL suggests that addition of this molecule to aP vaccines may induce a vaccination response that mimics natural infection better than the aP vaccine alone does, with favorable outcomes. Furthermore, vaccination, and particularly aP vaccination, induced type I hypersensitivity, a Th2-driven response (44). Since MPL can redirect responses from Th2 to Th1, it is conceivable that this hypersensitivity may be reduced by including this molecule in the vaccine.

Here, we first investigated whether the replacement of aluminum by MPL in a diphtheria-tetanus-aP vaccine would beneficially affect the vaccine in a mouse model system. In a second series of experiments, LpxL2 LPS was also included as an alternative adjuvant. The clearance of a B. pertussis challenge, the Ptx-specific serum IgG levels, the parameters of type I hypersensitivity, and serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels (elevated IL-6 levels suggest reactogenicity) were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccines and adjuvants. (i) Series 1.

The acellular (DTaP) vaccine was a combined vaccine consisting of diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, and a 3-component aP vaccine (25 μg formaldehyde- and glutaraldehyde-detoxified Ptx, 25 μg filamentous hemagglutinin, and 8 μg pertactin; GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium) in 0.5 ml saline (1 human dose [HD]). The vaccine contained aluminum hydroxide as an adjuvant (<0.625 mg aluminum/HD).

The DTaP vaccine was supplemented with two adjuvants, aluminum adjuvant [2% Al(OH)3 gel; Serva, Heidelberg, Germany] or MPL. To 1 HD DTaP vaccine, 2 ml aluminum-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 1/3 [vol/vol]) was added. MPL (from Salmonella enterica serotype Minnesota Re 595) was from Sigma-Aldrich, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands. To 1 HD DTaP vaccine, 2 ml of 100 μg/ml MPL-PBS was added. The amount of MPL administered is less than the amount that showed no toxicological effects in a single-dose toxicity study (2).

(ii) Series 2.

The same DTaP vaccine used for series 1 was used for series 2.

The wP vaccine was prepared from B. pertussis strain B213, a streptomycin-resistant derivative of strain Tohama I (23). The bacteria were grown in synthetic THIJS medium (43) for 68 h at 35°C while the mixture was shaken (175 rpm). The bacterial cell suspensions were heat inactivated for 10 min at 56°C in the presence of 8 mM formaldehyde, after which the cells were collected by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 10 min and resuspended in PBS to an A590 of 2.5, i.e., 50 international opacity units per ml (∼1.6 HD/ml). The suspensions were stored at 4°C.

Before immunization, the DTaP and wP vaccines were diluted in PBS to 1/10 HD, after which 3 mg/ml aluminum phosphate (Brenntag, Dordrecht, The Netherlands), 40 μg/ml MPL (Sigma-Aldrich), or 40 μg/ml N. meningitidis LpxL2 LPS (46) was added as an adjuvant.

Animals.

Female BALB/c mice were used at 6 to 8 weeks of age. They were obtained from the breeding colony of the Vaccine Institute (Bilthoven, The Netherlands) or from Harlan (Horst, The Netherlands). The diet consisted of ground standard laboratory chow (RMH-B; Hope Farms, Woerden, The Netherlands). Food and water were given ad libitum. All animal experiments were performed according to national and international guidelines.

Vaccination. (i) Series 1.

Mice received a subcutaneous (s.c.) injection of 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine in 0.5 ml aluminum, 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine in 0.5 ml MPL, 0.5 ml aluminum alone, or 0.5 ml MPL alone 28 and 14 days before infection. In one experiment, mice received an s.c. injection with 1/5, 1/25, or 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine in 0.5 ml aluminum; 1/5, 1/25, or 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine in 0.5 ml MPL; 0.5 ml aluminum alone; or 0.5 ml MPL alone.

(ii) Series 2.

Mice received an s.c. injection with 1/10 HD wP vaccine in 0.5 ml aluminum, 1/10 HD DTaP vaccine in 0.5 ml aluminum, 1/10 HD in 0.5 ml LpxL2 LPS, 1/10 HD in 0.5 ml MPL, or 0.5 ml PBS 28 and 14 days before infection.

Bacterial strain and growth conditions.

B. pertussis Tohama strain B213 was used. The Tohama strain has been shown to multiply in the lungs of mice (8, 16, 19). The bacteria were grown on Bordet-Gengou (BG) agar plates supplemented with 30 μg/ml streptomycin (Tritium, Veldhoven, The Netherlands) at 35°C for 3 days. Subsequently, the bacteria were plated on BG agar plates without antibiotics, cultured for 3 days, resuspended in Verwey medium (NVI, Bilthoven, The Netherlands), and used for infection.

Infection of mice and autopsy.

Intranasal infection was performed as described previously (47). Briefly, the mice were lightly anesthetized and a single drop of a 40-μl inoculum containing 2 × 107 B. pertussis cells was carefully placed on the top of the nose and allowed to be inhaled.

The mice were killed at 3, 5, or 7 days after infection. The animals were anesthetized with ketamine, xylazine (Rompun), and atropine; and blood was collected from the orbital plexus. Perfusion of the right ventricle was performed with 2 ml PBS supplemented with 3.5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (PAA, Linz, Austria). The lungs were excised and used either to obtain bronchial lymph nodes (LNs) and lung lobes for enumeration of the bacteria and for histological examinations or to obtain bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) cells.

Lung lobes, CFU determination, and histological examination.

A ligature was made around the right bronchus, after which the right lobes were removed for the enumeration of the bacteria. The lobes were homogenized in 900 μl of Verwey medium by using a tissue homogenizer (Pro-200; ProScientific, Monroe, CT) at maximum speed for 10 s. The homogenates were diluted in Verwey medium 10- and 100-fold for the immunized mice and 1,000-fold for the control mice, and 100-μl aliquots of the dilutions were plated on BG agar plates supplemented with streptomycin and incubated at 35°C for 5 days. The remaining left lung lobes were fixed intratracheally by using 4% formalin for 24 h. After dehydration overnight, they were embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Histological lesions were semiquantitatively scored as absent (0), minimal (1), slight (2), moderate (3), strong (4), or severe (5), respectively. This score incorporates the frequency as well as the severity of the lesions.

Ptx-specific IgG.

Ptx-specific IgG was measured essentially as described previously for the analysis of human sera (14). Briefly, 96-well plates (Immuno Plate; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were precoated with Ptx (NVI). Positive control serum was a pool of sera obtained from a previous experiment in which mice were vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine plus either aluminum or MPL and challenged with B. pertussis. The concentration of the positive control serum was arbitrarily set at 1,000 U. Dilution series of test sera and positive control sera were prepared in blocking buffer (0.5% bovine serum albumin [Sigma-Aldrich, Axel, The Netherlands] and 0.01% Tween 20 [Merck, Amsterdam, The Netherlands] in PBS). The plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and washed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS. The plates were then incubated with 2,000-fold-diluted peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) in blocking buffer for 1 h at 37°C and washed. Finally, the plates were incubated with substrate solution (10% sodium acetate, 1.66% tetramethylbenzidine [Sigma-Aldrich], and 0.02% H2O2) for 5 min and read at 450 nm.

Total serum IgE.

Blood was allowed to clot at 4°C overnight and was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 2 min. Total serum IgE was measured as described previously (44).

BALF cells.

A cannula was placed intratracheally and was fixed with a suture. The lungs were placed in a 50-ml tube filled with PBS. One milliliter PBS was brought into the lung and sucked up. This was repeated twice. BALF cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in PBS, counted with a Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics, Luton, United Kingdom), and visually differentiated after they were stained with Giemsa stain.

Cell culture.

The culture medium used was RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 IU/ml penicillin. Cell suspensions were made by pressing the LNs or spleens through a cell strainer (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The cells were counted with a Coulter Counter. LN cell suspensions were cultured at 106 cells per ml culture medium with 5 μg/ml concanavalin A (ConA; MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) in flat-bottom 12-well culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24 h. Spleen cell suspensions were cultured at 106 cells per ml culture medium with 5 μg/ml ConA or B. pertussis (105 heat-inactivated bacteria per well) in 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunc) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 72 h. The bacteria were heat inactivated at 56°C for 30 min.

Cytokine measurements.

The cytokine concentrations in the culture supernatants were measured by using a five-plex panel containing beads for mouse IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) or an eight-plex panel containing beads for mouse IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-12p70, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), as described previously (44). IL-6 concentrations in the sera were quantified by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, according to the manufacturer's instructions (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

Statistics.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test was performed when the data for multiple groups were compared (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The independent-samples t test was used when the data for two groups were compared (SPSS). Histological data were analyzed by using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test (SPSS).

RESULTS

B. pertussis colonization of the lungs.

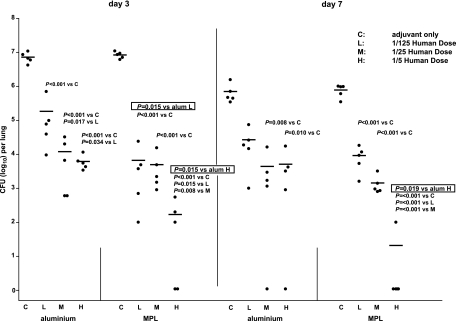

To analyze whether supplementation of the DTaP vaccine with MPL improved the efficacy of the vaccine in comparison with that achieved with supplementation with aluminum, mice were vaccinated twice with 1/5, 1/25, or 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine supplemented with either MPL or aluminum as the adjuvant and were then challenged intranasally with B. pertussis. At 3 and 7 days after infection, the mice were killed and the CFU in the lungs was enumerated. Animals treated with the adjuvants only showed a decreased number of CFU at day 7 after infection compared to that at day 3 after infection (Fig. 1). Vaccination with 1/5, 1/25, or 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine resulted in a reduced number of CFU at day 3 after infection, independent of the adjuvant used. Also at day 7 postinfection, the vaccinated animals showed a reduced number of CFU compared to the number in animals treated with adjuvant only, although the difference was not significant in the case of mice vaccinated with 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum. Importantly, vaccination with 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant resulted in a lower number of CFU than the number obtained when the same dose DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant was used both at day 3 and at day 7 after infection. At day 3 after infection, this was also observed when 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine was used. In conclusion, the MPL-supplemented vaccine provided better protection than the aluminum-supplemented vaccine.

FIG. 1.

Colonization of the lungs by B. pertussis. Mice were subcutaneously injected with (H) 1/5, (M) 1/25, or (L) 1/125 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum (alum) or MPL or (C) with the adjuvants only twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. At 3 and 7 days after infection the lungs were excised and the number of viable B. pertussis organisms in the right lung lobes was determined. Each symbol represents the number of bacteria in the lung of an individual mouse; horizontal lines represent the group average. Nonboxed numbers show P values when the different vaccine doses were compared for the same adjuvant and day of killing. Boxed numbers show P values when the different adjuvants are compared for the same vaccine dose and day of killing. ANOVA was followed by t test. The results of a single representative experiment of three are shown.

Ptx-specific IgG.

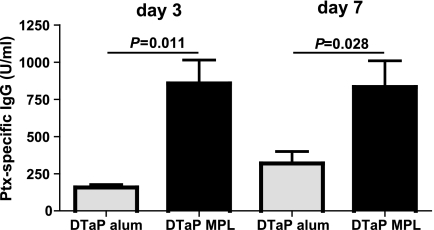

Since Ptx-specific IgG titers have previously been shown to correlate with protective immunity (11, 41), Ptx-specific IgG levels were measured in serum. When MPL was used as the adjuvant, the vaccinated animals showed 5.4- and 2.6-fold higher Ptx-specific IgG levels at days 3 and 7, respectively, compared to the levels in the mice vaccinated with DTaP vaccine plus aluminum (Fig. 2). Treatment with aluminum or MPL only did not result in detectable Ptx-specific IgG levels. In conclusion, the better protection observed in the case of the MPL-supplemented vaccine correlated with higher Ptx-specific IgG levels.

FIG. 2.

Ptx-specific IgG in serum. Mice were injected s.c. with 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum (alum) or MPL or with the adjuvants only twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. At 3 and 7 days after infection, the mice were euthanized. Serum was taken, and serial dilutions of test and positive control sera were tested for Ptx-specific IgG. The data are indicated as the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 5). ANOVA was followed by t test. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

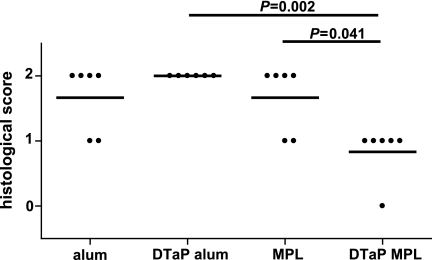

Evaluation of histological changes.

We have previously shown that mice vaccinated with DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant and subsequently challenged with B. pertussis revealed increased lung pathology compared to that in mice that were treated only with the adjuvant before challenge (44). To address whether the adjuvant in the vaccine influenced lung pathology, the lung histology was scored 3 days after infection. For both types of adjuvant, the vaccinated animals showed increased perivasculitis (P = 0.009 compared to the results obtained with aluminum only and P = 0.015 compared to the results obtained with MPL only). The level of eosinophilia was lower in mice vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant than in mice that received MPL only and than in mice that received the DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant (Fig. 3). Vaccination resulted in minor increases in peribronchiolitis, hypertrophy of the bronchiolar mucus cells, and alveolitis (data not shown). In conclusion, the MPL-supplemented vaccine induced lower levels of eosinophilia than the aluminum-supplemented one, which is suggestive of a lower type I hypersensitivity.

FIG. 3.

Lung eosinophilia. Mice were injected s.c. with 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum (alum) or MPL or with the adjuvants only twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. At 3 days after infection, the left lung lobes were excised. Each symbol represents an individual mouse; horizontal lines represent the group average. The Mann-Whitney U test was used. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

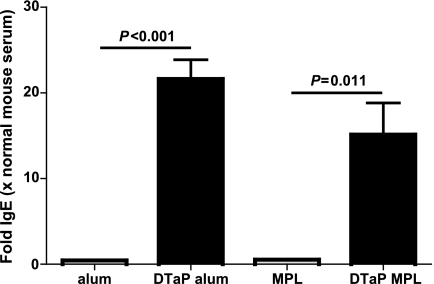

Total serum IgE levels.

Another parameter of type I hypersensitivity is an increased serum IgE level. We have previously shown that mice vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant and subsequently challenged with B. pertussis displayed a large increase in serum IgE levels compared to the levels in mice that were treated only with adjuvant before challenge (44). To investigate whether supplementation of the DTaP vaccine with MPL instead of aluminum resulted in lower total serum IgE levels, serum was taken 3 days after infection and analyzed. The total IgE level was higher in both vaccinated groups, and no significant differences that depended on the type of adjuvant in the vaccine were seen (Fig. 4). Thus, the type of adjuvant used in the vaccine did not influence total serum IgE levels.

FIG. 4.

Total serum IgE. Mice were injected s.c. with 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum (alum) or MPL or with the adjuvants only twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. At 3 days after infection, serum was taken and assayed for total IgE. The data are indicated as the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 6). ANOVA was followed by use of the Bonferroni correction. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

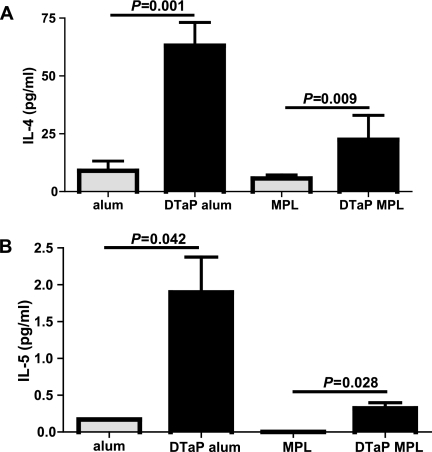

Cytokine production by bronchial LN cells.

Next to lung eosinophilia, the increased production of the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 was suggestive of a type I hypersensitivity response in previous vaccination experiments with the DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant (44). As MPL can redirect Th2 to Th1 responses, we reasoned that the hypersensitivity response might be lower after vaccination with the MPL-supplemented vaccine. To examine this possibility further, bronchial LN cells were cultured in the presence of ConA for 24 h and the supernatants were analyzed for their cytokine contents by using an eight-plex assay that measured three Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10), one Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ), and four additional cytokines involved in immune regulation (IL-2, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, and TNF-α). Bronchial LN cells from mice that were vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant showed higher levels of IL-4 production than those from mice that received aluminum only or mice that were vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant (Fig. 5A). No treatment-related differences were seen for IL-2 and IFN-γ. The levels of production of IL-5, IL-10, IL-12p70, GM-CSF, and TNF-α by the bronchial LN cells from mice that received aluminum only were below the detection limit. Bronchial LN cells from mice that were vaccinated with DTaP vaccine in MPL showed higher levels of TNF-α production than those of mice that received MPL only (P = 0.011). No further differences were seen when the production of these cytokines by the bronchial LNs of mice vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine in MPL was compared with those of mice vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine in aluminum or mice that received MPL only (data not shown). In conclusion, vaccination with the vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant resulted in lower levels of ex vivo ConA-induced IL-4 production by bronchial LNs compared to those achieved after vaccination with the aluminum-supplemented vaccine, indicating that the immune response was skewed more toward a Th1-type response.

FIG. 5.

(A) IL-4 production by ex vivo ConA-stimulated bronchial LN cells. Mice were injected s.c. with 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum (alum) or MPL or with the adjuvants only twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. Three days after infection, the bronchial LNs were excised, the cells were cultured with ConA for 24 h, and the supernatants were analyzed for their cytokine contents. (B) IL-5 production by splenocytes stimulated ex vivo with heat-killed B. pertussis. The splenocytes were cultured with heat-killed B. pertussis for 72 h, and the supernatants were analyzed for their cytokine contents. The data are indicated as the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 6). ANOVA was followed by use of the Bonferroni correction. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

Cytokine production by splenocytes.

To evaluate whether the adjuvant used in the vaccine affected ex vivo cytokine production by splenocytes, these cells from vaccinated and control mice were isolated and cultured in the presence of heat-killed B. pertussis for 72 h and the supernatants were analyzed for their cytokine contents by using a five-plex assay that measured four Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13) and one Th1 cytokine (IFN-γ). Splenocytes from mice that were vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine in aluminum showed higher levels of IL-5 production than those from mice that received aluminum only or mice that were vaccinated with the DTaP vaccine in MPL (Fig. 5B). No IL-4 production by the splenocytes from animals that received either of the adjuvants only was detected, whereas the splenocytes of the vaccinated animals showed mutually similar levels of IL-4 production of ∼7 pg/ml (data not shown). Splenocytes from all treatment groups showed similar levels of IFN-γ production of ∼8 pg/ml, while IL-10 and IL-13 production could not be detected (data not shown). In conclusion, the lower level of ex vivo B. pertussis-induced IL-5 production by splenocytes from the mice vaccinated with MPL-DTaP vaccine compared to that by splenocytes from the mice vaccinated with aluminum-DTaP vaccine is again suggestive of a more Th1-type response.

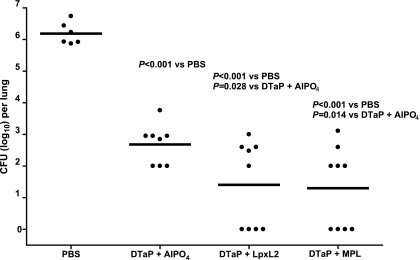

B. pertussis colonization of the lungs.

The results presented so far indicate that MPL compares favorably to aluminum as an adjuvant for the DTaP vaccine. To determine whether LpxL2 LPS would also be a suitable adjuvant, a second series of experiments was performed in which the mice were vaccinated twice with 1/10 HD DTaP vaccine plus either aluminum, LpxL2 LPS, or MPL before intranasal B. pertussis infection. Five days after infection, the mice were killed and the CFU in their lungs was enumerated. Compared to the control group that received PBS, all three vaccines conferred significant protection against colonization (Fig. 6). Importantly, the vaccines with LpxL2 LPS and MPL as the adjuvants provided significantly better protection than the vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant. Thus, with respect to efficacy, LpxL2, like MPL, compared favorably to aluminum as the adjuvant in the vaccine.

FIG. 6.

Colonization of the lungs by B. pertussis. Mice were injected s.c. with PBS or 1/10 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum, LpxL2 LPS, or MPL twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. At 5 days after infection the lungs were excised, and the number of viable B. pertussis organisms was determined. Each symbol represents the number of bacteria in the lung of an individual mouse; horizontal lines represent the group average. ANOVA was followed by t test. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

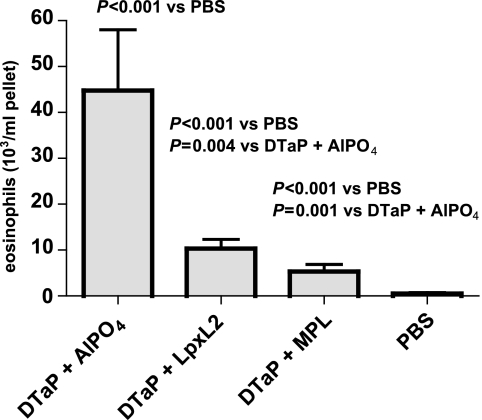

BALF cells.

In order to determine whether the various adjuvants in the vaccine affected the cell-type distribution differently, lung lavage was performed 5 days after infection, and the BALF cells were counted and visually differentiated. The percentages and numbers of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes were similar in all groups; and the total number of BALF cells was also not differentially affected. However, the group immunized with the DTaP vaccine plus aluminum showed a significantly higher number of eosinophils than all other groups (Fig. 7). In conclusion, the use of LpxL2 LPS, like the use of MPL, instead of aluminum as the adjuvant in the DTaP vaccine resulted in a lower percentage and a lower number of eosinophils in the BALF, which is indicative of a lower type I hypersensitivity.

FIG. 7.

BALF eosinophil numbers. Mice were injected s.c. with 1/10 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum, LpxL2 LPS, or MPL or with PBS twice before intranasal B. pertussis infection. At 5 days after infection, lung lavage was performed and the BALF cells were counted and visually differentiated. The data are indicated as the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 6). ANOVA was followed by use of the Bonferroni correction. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

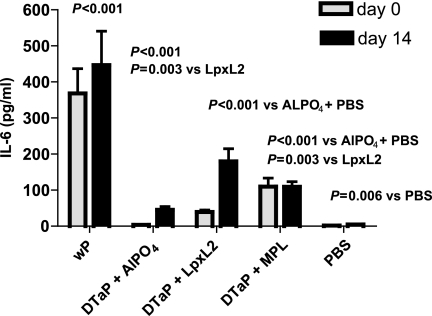

Vaccine reactogenicity.

While both LPS analogs, in comparison to aluminum, improve the efficacy of the DTaP vaccine and reduce type I hypersensitivity, they should not increase the reactogenicity of the DTaP vaccine. To address this issue, the concentration of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 was analyzed in serum samples taken 4 h after primary or booster immunization. A group of mice immunized with a wP vaccine, which is known to display considerable reactogenicity, was included as an additional control in these experiments. Consistent with the relatively high reactogenicity of the wP vaccine, significantly higher serum IL-6 levels were elicited in the group of mice that received this vaccine compared to the levels elicited in all other groups (Fig. 8). The IL-6 levels elicited by vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant were similar to those elicited by PBS (as a control). Importantly, supplementation of the vaccine with either LPS analog elicited IL-6 levels higher than those elicited by supplementation of the vaccine with aluminum, although these IL-6 levels were considerably lower than those elicited by the wP vaccine. Vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant elicited higher IL-6 levels during booster immunization than during primary immunization (P = 0.004); a similar effect was observed for vaccination with the DTaP vaccine with LpxL2 LPS as the adjuvant (P = 0.007) but not with the DTaP vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant. In conclusion, the higher IL-6 levels obtained when LpxL2 LPS or MPL was used as the adjuvant in the DTaP vaccine may suggest some reactogenicity. The considerably lower IL-6 level induced by the DTaP vaccine than the level induced by the wP vaccine suggests that the DTaP vaccine supplemented with LPS analogs has a lower reactogenicity than the wP vaccine.

FIG. 8.

Serum IL-6. Mice were injected s.c. with 1/10 HD wP vaccine; 1/10 HD DTaP vaccine plus aluminum, LpxL2 LPS, or MPL; or PBS. Serum IL-6 concentrations were determined 4 h postimmunization. The data are indicated as the means ± standard errors of the means (n = 7). ANOVA was followed by use of the Bonferroni correction. The results of a single representative experiment of two are shown.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have shown that the replacement of aluminum by either one of two LPS analogs, MPL or LpxL2 LPS, as the adjuvant in the DTaP vaccine improves the vaccine in two ways; first, it enhances its efficacy, as shown by the reduced colonization of the lungs after challenge and (in the case of MPL) increased the Ptx-specific IgG titer; second, it skews the response more toward a Th1-type response, as indicated by the lower levels of Th2 cytokine production, resulting in a decrease in the parameters indicative of type I hypersensitivity, i.e., lung eosinophilia and eosinophil numbers. The higher IL-6 levels induced by these supplemented DTaP vaccines compared to those induced by the DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant may suggest some reactogenicity, although the reactogenicity is well below that of the wP vaccine.

We have investigated whether MPL is able to enhance vaccine efficacy by performing a dose-response analysis. While vaccination with 1/5 HD DTaP vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant resulted in a significantly decreased colonization compared to that achieved with the DTaP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant, this was not observed with 1/25 and 1/125 HD, suggesting that MPL is more effective than aluminum only at a relatively high DTaP vaccine dosage. When LpxL2 LPS and MPL were compared as adjuvants, both LPS analogs seemed to improve the efficacy of the DTaP vaccine to similar extents when 1/10 HD DTaP vaccine was used.

There is controversy regarding the correlation between Ptx-specific IgG levels and protective immunity. Ptx-specific IgG levels have been shown to correlate with protection in both humans (11, 41, 42) and mice (7). Cell-mediated immunity, however, also critically contributes to protection in both humans (1, 9, 24) and mice (30). The latter notion may be an explanation of the various degrees of association between the IgG levels against B. pertussis antigens in serum and protective immunity. The association between Ptx-specific IgG levels and protective immunity is most apparent early after vaccination (10). We measured the Ptx-specific IgG titers 17 and 21 days after the second vaccination, that is, relatively early after vaccination, making it plausible that in our study Ptx-specific IgG levels indeed correlated with protection.

The use of MPL as the adjuvant resulted in higher Ptx-specific IgG levels than those achieved when aluminum was used, suggesting improved protection. Thus, both the improved clearance of B. pertussis and the higher Ptx-specific IgG levels suggest a more efficacious vaccine when MPL is used as the adjuvant in the DTaP vaccine. In both humans (5) and mice (37, 45), aP vaccines induce much higher Ptx-specific IgG levels than wP vaccines. However, in the present study we compared the Ptx-specific IgG levels between aP-vaccinated mice only. It may be suggested that the Ptx-specific IgG levels that are induced by vaccination are affected by bacterial challenge. Prechallenge levels are, however, similar to the levels detected at 3 and 7 days postchallenge (R. M. Stenger and R. J. Vandebriel, unpublished observations).

We have previously shown that pertussis vaccination, especially with the DTaP vaccine, resulted in type I hypersensitivity. IL-4-knockout mice that showed a reduced hypersensitivity response showed an unaffected clearance, suggesting that the hypersensitivity is not beneficial and is possibly detrimental to the host (44). As MPL can redirect Th2 to Th1 responses (3, 34, 38, 48), we reasoned that the hypersensitivity response might be decreased by adding MPL to the DTaP vaccine. Indeed, the level of lung eosinophilia, lung eosinophil numbers, and the level of Th2 cytokine production were all decreased when MPL was added to the DTaP vaccine. The increase in the total IgE level in serum was, however, unaffected by the addition of MPL. Possibly, the immune-modulating capacity of MPL is too small to affect this response or the underlying mechanism(s) of this response is (partly) different from that for Th2 to Th1 redirection.

LpxL2 LPS harbors strongly reduced endotoxic activity while still exhibiting some adjuvant activity compared to that of wild-type N. meningitidis LPS (46). We speculated that it might also be effective in redirecting Th2 to Th1 responses. Consistently, lung eosinophil numbers were reduced when the DTaP vaccine was supplemented with LpxL2 LPS.

The levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 in serum samples taken 4 h after the primary and booster immunizations were higher when either of the LPS analogs was used as the adjuvant than when aluminum was used as the adjuvant. As expected, the IL-6 levels induced by the wP vaccine were significantly higher than those induced by the DTaP vaccine with any of the three adjuvants. Thus, the higher IL-6 levels induced by the DTaP vaccine supplemented with either LPS may suggest some reactogenicity, albeit a reactogenicity considerably lower than that of the wP vaccine. Unexpectedly, vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant evoked significantly higher IL-6 levels during booster immunization than during primary immunization (P = 0.004). This suggests that booster immunization, also in the absence of strong immune stimulatory molecules such as LPS, may elicit a stronger IL-6 response than primary immunization. A similar effect was observed for vaccination with the DTaP vaccine with LpxL2 LPS as the adjuvant (P = 0.007) but not with the DTaP vaccine with MPL as the adjuvant. The latter finding may suggest that LpxL2 LPS and MPL differ in their mechanism(s) of action.

We have chosen to measure IL-6 as the parameter for reactogenicity, as this cytokine had the most sensitive response to several pyrogens in an in vitro system based on a human monocytic cell line and the ex vivo human whole-blood culture test system. The latter test represents the rabbit pyrogen test (31). While low or moderate IL-6 levels form an essential part of the immune response, excessive levels may be detrimental. A level that can be taken as a threshold for reactogenicity has not been established, however, and we therefore interpret increased serum IL-6 levels as being suggestive of reactogenicity.

Although the effects of MPL are believed to mimic the effects of LPS, albeit with a considerably lower toxicity, differences in cytokine induction between these two molecules have been reported, with MPL inducing IL-10 and IL-12 and LPS inducing only IL-12 (40). This finding may be explained by later studies that have shown that MPL engages both TLR2 and TLR4, whereas LPS acts only on TLR4 (26), with TLR2 agonists inducing IL-10 and TLR4 agonists inducing IL-12 (35, 36). The lack of induction of IL-1β and caspase 1 may also be an expression of the reduced toxicity of MPL compared to that of LPS (32). Knowledge of the mechanisms of action of LpxL2 regarding receptor specificity and downstream effects are currently lacking.

The present study has shown that supplementation of the DTaP vaccine with LPS analogs improves the efficacy of the vaccine and reduces type I hypersensitivity. Follow-up studies are, however, required. In such studies, the aP vaccine with aluminum as the adjuvant should be compared to the aP vaccine with LPS analogs as adjuvants in the total absence of aluminum, a reference B. pertussis strain should be used for challenge, and pre- and postchallenge T-cell responses against the individual vaccine components should be measured.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that use of the DTaP vaccine with the LPS analogs MPL or LpxL2 LPS as the adjuvant improves vaccine efficacy and redirects the immune response from a Th2- to a Th1-type response, thereby reducing type I hypersensitivity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tjeerd Kimman and Willem van Eden for discussion. We thank Bert Elvers for providing Ptx-coated plates and Jihane Naji for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausiello, C. M., R. Lande, F. Urbani, A. la Sala, P. Stefanelli, S. Salmaso, P. Mastrantonio, and A. Cassone. 1999. Cell-mediated immune responses in four-year-old children after primary immunization with acellular pertussis vaccines. Infect. Immun. 674064-4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldrick, P., D. Richardson, A. W. Wheeler, and S. R. Woroniecki. 2004. Safety evaluation of a new allergy vaccine containing the adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) for the treatment of grass pollen allergy. J. Appl. Toxicol. 24261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldridge, J. R., Y. Yorgensen, J. R. Ward, and J. T. Ulrich. 2000. Monophosphoryl lipid A enhances mucosal and systemic immunity to vaccine antigens following intranasal administration. Vaccine 182416-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banus, H. A., R. J. Vandebriel, H. de Ruiter, J. A. Dormans, N. J. Nagelkerke, F. R. Mooi, B. Hoebee, H. J. van Kranen, and T. G. Kimman. 2006. Host genetics of Bordetella pertussis infection in mice: significance of Toll-like receptor 4 in genetic susceptibility and pathobiology. Infect. Immun. 742596-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berbers, G. A., A. B. Lafeber, J. Labadie, P. E. Vermeer-de Bondt, D. J. Bolscher, and A. D. Plantinga. 1999. A randomized controlled study with whole-cell or acellular pertussis vaccines in combination with regular DT-IPV vaccine and a new poliomyelitis (IPV Vero) component in children 4 years of age in The Netherlands. http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/105000001.pdf.

- 6.Boland, G., J. Beran, M. Lievens, J. Sasadeusz, P. Dentico, H. Nothdurft, J. N. Zuckerman, B. Genton, R. Steffen, L. Loutan, J. Van Hattum, and M. Stoffel. 2004. Safety and immunogenicity profile of an experimental hepatitis B vaccine adjuvanted with AS04. Vaccine 23316-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruss, J. B., and G. R. Siber. 2002. Quantitative priming with inactivated pertussis toxoid vaccine in the aerosol challenge model. Infect. Immun. 704600-4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carbonetti, N. H., G. V. Artamonova, R. M. Mays, and Z. E. Worthington. 2003. Pertussis toxin plays an early role in respiratory tract colonization by Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 716358-6366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassone, A., C. M. Ausiello, F. Urbani, R. Lande, M. Giuliano, A. La Sala, A. Piscitelli, S. Salmaso, et al. 1997. Cell-mediated and antibody responses to Bordetella pertussis antigens in children vaccinated with acellular or whole-cell pertussis vaccines. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 151283-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassone, A., P. Mastrantonio, and C. M. Ausiello. 2000. Are only antibody levels involved in the protection against pertussis in acellular pertussis vaccine recipients? J. Infect. Dis. 1821575-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherry, J. D., J. Gornbein, U. Heininger, and K. Stehr. 1998. A search for serologic correlates of immunity to Bordetella pertussis cough illnesses. Vaccine 161901-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dabbagh, K., and D. B. Lewis. 2003. Toll-like receptors and T-helper-1/T-helper-2 responses. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Melker, H. E., M. A. Conyn-van Spaendonck, H. C. Rumke, J. K. van Wijngaarden, F. R. Mooi, and J. F. Schellekens. 1997. Pertussis in The Netherlands: an outbreak despite high levels of immunization with whole-cell vaccine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 3175-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Melker, H. E., F. G. Versteegh, M. A. Conyn-Van Spaendonck, L. H. Elvers, G. A. Berbers, A. van der Zee, and J. F. Schellekens. 2000. Specificity and sensitivity of high levels of immunoglobulin G antibodies against pertussis toxin in a single serum sample for diagnosis of infection with Bordetella pertussis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38800-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dillon, S., A. Agrawal, T. Van Dyke, G. Landreth, L. McCauley, A. Koh, C. Maliszewski, S. Akira, and B. Pulendran. 2004. A Toll-like receptor 2 ligand stimulates Th2 responses in vivo, via induction of extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Fos in dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1724733-4743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elder, K. D., and E. T. Harvill. 2004. Strain-dependent role of BrkA during Bordetella pertussis infection of the murine respiratory tract. Infect. Immun. 725919-5924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans, J. T., C. W. Cluff, D. A. Johnson, M. J. Lacy, D. H. Persing, and J. R. Baldridge. 2003. Enhancement of antigen-specific immunity via the TLR4 ligands MPL adjuvant and Ribi 529. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2219-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giannini, S. L., E. Hanon, P. Moris, M. Van Mechelen, S. Morel, F. Dessy, M. A. Fourneau, B. Colau, J. Suzich, G. Losonksy, M. T. Martin, G. Dubin, and M. A. Wettendorff. 2006. Enhanced humoral and memory B cellular immunity using HPV16/18 L1 VLP vaccine formulated with the MPL/aluminum salt combination (AS04) compared to aluminum salt only. Vaccine 245937-5949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harvill, E. T., P. A. Cotter, and J. F. Miller. 1999. Pregenomic comparative analysis between Bordetella bronchiseptica RB50 and Bordetella pertussis Tohama I in murine models of respiratory tract infection. Infect. Immun. 676109-6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins, S. C., E. C. Lavelle, C. McCann, B. Keogh, E. McNeela, P. Byrne, B. O'Gorman, A. Jarnicki, P. McGuirk, and K. H. Mills. 2003. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate IL-10 activates antigen-specific regulatory T cells and confers resistance to Bordetella pertussis by inhibiting inflammatory pathology. J. Immunol. 1713119-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins, S. C., A. G. Jarnicki, E. C. Lavelle, and K. H. Mills. 2006. TLR4 mediates vaccine-induced protective cellular immunity to Bordetella pertussis: role of IL-17-producing T cells. J. Immunol. 1777980-7989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapsenberg, M. L. 2003. Dendritic-cell control of pathogen-driven T-cell polarization. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3984-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King, A. J., G. Berbers, H. F. van Oirschot, P. Hoogerhout, K. Knipping, and F. R. Mooi. 2001. Role of the polymorphic region 1 of the Bordetella pertussis protein pertactin in immunity. Microbiology 1472885-2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahon, B. P., M. T. Brady, and K. H. Mills. 2000. Protection against Bordetella pertussis in mice in the absence of detectable circulating antibody: implications for long-term immunity in children. J. Infect. Dis. 1812087-2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann, P. B., D. Wolfe, E. Latz, D. Golenbock, A. Preston, and E. T. Harvill. 2005. Comparative Toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate host defense to Bordetella infection. Infect. Immun. 738144-8152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, M., S. M. Michalek, and J. Katz. 2003. Role of innate immune factors in the adjuvant activity of monophosphoryl lipid A. Infect. Immun. 712498-2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormack, P. L., and A. J. Wagstaff. 2006. Ultra-short-course seasonal allergy vaccine (Pollinex Quattro). Drugs 66931-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McVernon, J., N. Andrews, M. P. Slack, and M. E. Ramsay. 2003. Risk of vaccine failure after Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) combination vaccines with acellular pertussis. Lancet 3611521-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medzhitov, R. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1135-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills, K. H., M. Ryan, E. Ryan, and B. P. Mahon. 1998. A murine model in which protection correlates with pertussis vaccine efficacy in children reveals complementary roles for humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection against Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 66594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa, Y., H. Maeda, and T. Murai. 2002. Evaluation of the in vitro pyrogen test system based on proinflammatory cytokine release from human monocytes: comparison with a human whole blood culture test system and with the rabbit pyrogen test. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9588-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okemoto, K., K. Kawasaki, K. Hanada, M. Miura, and M. Nishijima. 2006. A potent adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A triggers various immune responses, but not secretion of IL-1beta or activation of caspase-1. J. Immunol. 1761203-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Persing, D. H., R. N. Coler, M. J. Lacy, D. A. Johnson, J. R. Baldridge, R. M. Hershberg, and S. G. Reed. 2002. Taking toll: lipid A mimetics as adjuvants and immunomodulators. Trends Microbiol. 10S32-S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puggioni, F., S. R. Durham, and J. N. Francis. 2005. Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) promotes allergen-induced immune deviation in favour of Th1 responses. Allergy 60678-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Re, F., and J. L. Strominger. 2001. Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 differentially activate human dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27637692-37699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Re, F., and J. L. Strominger. 2004. IL-10 released by concomitant TLR2 stimulation blocks the induction of a subset of Th1 cytokines that are specifically induced by TLR4 or TLR3 in human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1737548-7555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Redhead, K., J. Watkins, A. Barnard, and K. H. Mills. 1993. Effective immunization against Bordetella pertussis respiratory infection in mice is dependent on induction of cell-mediated immunity. Infect. Immun. 613190-3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reed, S. G., R. N. Coler, and A. Campos-Neto. 2003. Development of a leishmaniasis vaccine: the importance of MPL. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2239-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saito, K., T. Yajima, H. Nishimura, K. Aiba, R. Ishimitsu, T. Matsuguchi, T. Fushimi, Y. Ohshima, Y. Tsukamoto, and Y. Yoshikai. 2003. Soluble branched beta-(1,4)glucans from Acetobacter species show strong activities to induce interleukin-12 in vitro and inhibit T-helper 2 cellular response with immunoglobulin E production in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 27838571-38578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salkowski, C. A., G. R. Detore, and S. N. Vogel. 1997. Lipopolysaccharide and monophosphoryl lipid A differentially regulate interleukin-12, gamma interferon, and interleukin-10 mRNA production in murine macrophages. Infect. Immun. 653239-3247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Storsaeter, J., H. O. Hallander, L. Gustafsson, and P. Olin. 1998. Levels of anti-pertussis antibodies related to protection after household exposure to Bordetella pertussis. Vaccine 161907-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taranger, J., B. Trollfors, T. Lagergard, V. Sundh, D. A. Bryla, R. Schneerson, and J. B. Robbins. 2000. Correlation between pertussis toxin IgG antibodies in postvaccination sera and subsequent protection against pertussis. J. Infect. Dis. 1811010-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thalen, M., J. van den IJssel, W. Jiskoot, B. Zomer, P. Roholl, C. de Gooijer, C. Beuvery, and J. Trampen. 1999. Rational medium design for Bordetella pertussis: basic metabolism. J. Biotechnol. 75147-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vandebriel, R. J., E. R. Gremmer, J. P. Vermeulen, S. M. Hellwig, J. A. Dormans, P. J. Roholl, and F. R. Mooi. 2007. Lung pathology and immediate hypersensitivity in a mouse model after vaccination with pertussis vaccines and challenge with Bordetella pertussis. Vaccine 252346-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van den Berg, B. M., S. David, H. Beekhuizen, F. R. Mooi, and R. van Furth. 2000. Protection and humoral immune responses against Bordetella pertussis infection in mice immunized with acellular or cellular pertussis immunogens. Vaccine 191118-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Ley, P., L. Steeghs, H. J. Hamstra, J. ten Hove, B. Zomer, and L. van Alphen. 2001. Modification of lipid A biosynthesis in Neisseria meningitidis lpxL mutants: influence on lipopolysaccharide structure, toxicity, and adjuvant activity. Infect. Immun. 695981-5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willems, R. J., J. Kamerbeek, C. A. Geuijen, J. Top, H. Gielen, W. Gaastra, and F. R. Mooi. 1998. The efficacy of a whole cell pertussis vaccine and fimbriae against Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis infections in a respiratory mouse model. Vaccine 16410-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, P., Q. B. Yang, D. F. Balkovetz, J. P. Lewis, J. D. Clements, S. M. Michalek, and J. Katz. 2005. Effectiveness of the B subunit of cholera toxin in potentiating immune responses to the recombinant hemagglutinin/adhesin domain of the gingipain Kgp from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Vaccine 234734-4744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]