Abstract

Twenty-one free-ranging Central Kalahari lions (Panthera leo) exhibited a high prevalence rate of feline herpesvirus (100%) and feline immunodeficiency virus (71.4%). Canine distemper virus and feline calicivirus occurred with a low prevalence. All individuals tested negative for feline coronavirus, feline parvovirus, feline leukemia virus, Ehrlichia canis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

Viruses can be categorized as either endemic or epidemic. Endemic viruses are constantly highly prevalent in a population but exhibit low pathogenicity (1), thereby often causing permanent infection (12). Epidemic viruses, in contrast, infect a population briefly but cause higher host mortality (2) and leave a small proportion of infected hosts as asymptomatic carriers. While endemic diseases can persevere even in low-density populations, epidemic diseases need certain threshold densities of susceptibilities for their establishment in natural populations. Thus, epidemic outbreaks depend on large numbers of susceptibilities (12), and their extent depends on the size of the susceptible host population (4, 8). In the Serengeti, infections of canine distemper virus (CDV), feline coronavirus (FCoV), and feline parvovirus (FPV) have occurred in times of high-population density, while feline calicivirus infections (FCV) seemed to be density independent (12). Thus, low-density populations should be less affected by epidemic diseases, while endemic viruses should exhibit a similarly high prevalence in low- and high-density populations due to their density independence.

To verify these assumptions, we analyzed 21 blood samples from a low-density population of free-ranging lions in the Khutse and the Central Kalahari Game Reserves in Botswana. Due to the semiarid climate and the low prey availability, lion density in this area is as low as 0.021 lions/km2 (S. Ramsauer and B. König, unpublished data) compared to other regions in east Africa with densities of 0.1 to 0.4 lions/km2 (6, 15).

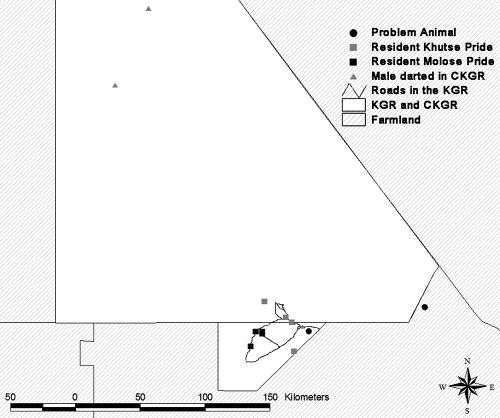

Twenty-one samples from 13 females and 8 males were collected in the Khutse and the Central Kalahari Game Reserves in Botswana (for location of sampling events see Fig. 1; for detailed information about each sampled animal see Table 1; for exact procedure of sampling see S. Ramsauer and B. König, submitted for publication). All serum samples were tested for the presence of antibodies to feline viruses CDV, feline herpesvirus (FHV), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), FCV, FCoV, FPV, and feline leukemia virus (FeLV) under conditions described in detail by G. Bay et al. (submitted for publication). Additionally, the sera were examined for the presence of antibodies to E. canis and A. phagocytophilum.

FIG. 1.

Map of the study area, including the Khutse Game Reserve and the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. For detailed information about the sampling events, refer to Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Detailed description of the sampled individuals and the locations of sampling eventsa

| Lion no. | Pride | Sex | Age | Sampling coordinates (degrees)

|

Date of sampling (day.mo.yr) | Antibody titer

|

Antibodies to p24b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South | East | FHV | FCV | CDV | ||||||

| 1 | PAc | Male | Adult | 23.22176 | 25.35267 | 15.02.03 | 160 | 320 | ||

| 2 | PAc | Female | Adult | 23.22176 | 25.35267 | 15.02.03 | 80 | |||

| 3 | PAc | Female | Adult | 23.37972 | 24.55348 | 07.03.03 | 160 | + | ||

| 4 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.31447 | 24.43520 | 29.05.03 | 160 | + | ||

| 5 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.47410 | 24.15041 | 29.05.03 | 320 | + | ||

| 6 | KGRd | Male | Adult | 23.50281 | 24.45052 | 08.11.03 | 80 | |||

| 7 | KGRd | Male | Adult | 23.50281 | 24.45052 | 08.11.03 | 320 | + | ||

| 8 | KGRd | Male | Adult | 23.38000 | 24.18476 | 28.03.04 | 80 | + | ||

| 9 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.38000 | 24.18476 | 15.05.04 | 160 | + | ||

| 10 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.38000 | 24.18476 | 15.05.04 | 80 | + | ||

| 11 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.38000 | 24.18476 | 15.05.04 | 160 | + | ||

| 12 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.38948 | 24.22524 | 04.09.04 | 1,280 | 40 | ||

| 13 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.28441 | 24.39003 | 28.10.04 | 640 | + | ||

| 14 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.28441 | 24.39003 | 28.10.04 | 640 | |||

| 15 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.18403 | 24.24282 | 19.11.04 | 640 | 40 | + | |

| 16 | KGRd | Female | Adult | 23.18403 | 24.24282 | 19.11.04 | 640 | |||

| 17 | KGRd | Female | Subadult | 23.18403 | 24.24282 | 19.11.04 | 640 | + | ||

| 18 | KGRd | Male | Adult | 23.38000 | 24.22524 | 18.04.05 | 320 | + | ||

| 19 | CKGRe | Male | Adult | 21.78052 | 23.20902 | 21.04.05 | 640 | + | ||

| 20 | CKGRe | Male | Adult | 21.28395 | 23.44058 | 22.04.05 | 320 | + | ||

| 21 | CKGRe | Male | Adult | 21.28395 | 23.44058 | 22.04.05 | 320 | + | ||

Prevalence rates were as follows: for FHV, 100%; for FCV, 9.5%; for CDV, 4.8%; and for FIV, 71.4%. No antibodies to FPV, FCov, E. canis, A. phagocytophilum, or FeLV were detected; thus, the prevalence rate for each of these organisms was 0%. For FeLV, we tested for antibodies to p45.

+, antibodies present. The presence of antibodies to p24 was taken as an indicator of FIV infection (for prevalence rate, see footnote a).

Problem animal (PA) captured and relocated into the Central Kalahari Game Reserve by the Department of Wildlife and National Parks.

Resident animal in the Khutse Game Reserve (KGR).

Male darted in the north of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR).

Feline infectious diseases reported as epidemic in other regions have occurred at very low prevalence rates or were absent from the free-ranging lion population in Botswana. None of the 21 samples tested positive for the presence of antibodies to FCoV or FPV, although both viruses have been previously reported to occur throughout Southern Africa (13, 14) and have been described as epidemic in East Africa (12).

Antibodies to CDV were detected in only one sample collected from a stock-raiding individual, with a titer of 320. The close contact with domestic dogs can facilitate disease transmission (3). Although CDV is prevalent in Southern Africa, it has rarely been described in free-ranging lions (9). Similar to outbreaks of FCoV and FPV, CDV outbreaks seem to require large numbers of susceptibilities and occur during times of high-population densities, while FCV outbreaks seemed to be density independent (2, 12). Generally, lion densities in East Africa are much higher than in Southern Africa (5, 6; S. Ramsauer and B. König, submitted for publication), causing minimum threshold densities for epidemic outbreaks to be rarely met in low-density populations, thereby making these lion populations less vulnerable to epidemic outbreaks.

FCV was found to be prevalent in only two resident individuals (9.5%) and was prevalent in low titers of 40. Although FCV has been reported in Namibian cheetahs (9), it has not been previously found in Southern African free-ranging lions (14 and G. Bay et al., submitted for publication).

FHV occurred in 100% of the samples tested, with titers of 80 to 1,280, which is in accordance with previous studies showing that FHV is highly prevalent in all free-ranging lion populations tested so far (7, 14). So far, FHV seems to be innoxious to the survival or to the lifetime reproductive success of infected individuals, but its high prevalence throughout different populations makes it difficult to compare infected and uninfected hosts (12).

In our study, 15 of 21 (71.4%) animals tested positive for FIV antibodies (p24). These results reveal a higher infection rate than that found by another study conducted in Botswana (11) and rather similar to those found in South Africa (10).

FeLV antibodies were not found in any of the 21 serum samples tested. This result is in accordance with all other studies of free-ranging lions, in which the presence of antibodies to FeLV was not found (7, 14).

The absence of the rickettsia E. canis bacterium is in accordance with results of other studies (G. Bay et al., submitted for publication).

None of the samples tested positive for A. phagocytophilum, which occurs in Southern Africa and has been found among free-ranging and captive lions in Zimbabwe (G. Bay et al. submitted for publication).

In conclusion, a free-ranging low-density lion population in Botswana was free of FCoV, FPV, FeLV, A. phagocytophilum, and E. canis. While CDV and FCV occurred at very low prevalence rates, the endemic FHV and FIV were highly prevalent, with rates of 100% and 71.4%, respectively. Neither of the highly prevalent pathogens found in the Kalahari lions elicited clinical signs of disease in free-ranging lions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Wildlife and National Parks and the Office of the President of Botswana for permission to conduct this research. Additionally, we thank Beatrice Weibel for excellent laboratory assistance and helpful support. Laboratory work was performed using the logistics of the Center for Clinical Studies at the Vetsuisse Faculty of the University of Zurich. S.R. also especially thanks Monika Schiess-Meier and the Leopard Ecology and Conservation Project for hospitality in their camp and shared use of equipment.

S.R. thanks the following organizations for financial support during the field work with lions: Janggen-Pöhn Stiftung, Forschungskommission der Universität Zürich, Fonds zur Förderung des Akademischen Nachwuchses (FAN), Zoo Basel, the Swiss Academy of Sciences, Switzerland, and the Rufford Small Grants Foundation, England. R.H.L. is the recipient of a professorship by the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP00B 102866).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, R. M., and R. M. May. 1979. Population biology of infectious diseases: part I. Nature 280:361-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, R. M., and R. M. May. 1979b. Population biology of infectious diseases: part II. Nature 280:455-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleaveland, S., M. G. J. Appel, W. S. K. Chalmers, C. Chillingworth, M. Kaare, and C. Dye. 2000. Serological and demographic evidence for domestic dogs as a source of canine distemper virus infection for Serengeti wildlife. Vet. Microbiol. 72:217-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobson, A. P., and P. J. Hudson. 1995. Microparasites: observed patterns in wild animal populations, p. 52-89. In A. P. Dobson and B. T. Grenfell (ed.), Ecology of infectious diseases in natural populations. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 5.Funston, P. J., M. G. L. Mills, P. R. K. Richardson, and A. S. van Jaarsveld. 2003. Reduced dispersal and opportunistic territory acquisition in male lions (Panthera leo). J. Zool. 259:131-142. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanby, J. P., J. D. Bygott, and C. Packer. 1995. Ecology, demography, and behavior of lions in two contrasting habitats: Ngorongoro Crater and the Serengeti plains, p. 315-331. In A. R. E. Sinclair and P. Arcese (ed.), Serengeti II: dynamics, management, and conservation of an ecosystem. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

- 7.Hofmann-Lehmann, R., D. Fehr, M. Grob, M. Elgizoli, C. Packer, J. S. Martenson, S. J. O'Brien, and H. Lutz. 1996. Prevalence of antibodies to feline parvovirus, calicivirus, herpesvirus, coronavirus, and immunodeficiency virus and of feline leukemia virus antigen and the interrelationship of these viral infections in free-ranging lions in east Africa. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 3:554-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffee, B., R. Phillips, A. Muldoon, and M. Mangel. 1992. Density-dependent host pathogen dynamics in soil microcosms. Ecology 73:495-506. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munson, L., L. Marker, E. Dubovi, J. A. Spencer, J. F. Evermann, and S. J. O'Brien. 2004. Serosurvey of viral infections in free-ranging Namibian cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). J. Wildlife Dis. 40:23-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olmsted, R. A., R. Langley, M. E. Roelke, R. M. Goeken, D. Adger-Johnson, J. P. Goff, J. P. Albert, C. Packer, M. K. Laurenson, T. M. Caro, L. Scheepers, D. E. Wildt, M. Bush, J. S. Martenson, and S. J. O'Brien. 1992. Worldwide prevalence of lentivirus infection in wild feline species: epidemiologic and phylogenetic aspects. J. Virol. 66:6008-6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osofsky, S. A., K. J. Hirsch, E. E. Zuckerman, and W. D. Hardy, Jr. 1996. Feline lentivirus and feline oncovirus status of free-ranging lions (Panthera leo), leopards (Panthera pardus), and cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) in Botswana: a regional perspective. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 27:453-467. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Packer, C., S. Altizer, M. J. G. Appel, E. Brown, J. S. Martenson, S. J. O'Brien, M. Roelke-Parker, R. Hofmann-Lehmann, and H. Lutz. 1999. Viruses of the Serengeti: patterns of infection and mortality in African lions. J. Anim. Ecol. 68:1161-1178. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spencer, J. A. 1991. Survey of antibodies to feline viruses in free-ranging lions. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 21:59-61. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer, J. A., and P. Morkel. 1993. Serological survey of sera from lions in Etosha National Park. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 23:60-61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spong, G. 2002. Space use in lions, Panthera leo L., in the Selous Game Reserve: social and ecological factors. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 52:303-307. [Google Scholar]