Abstract

Candida parapsilosis is an important cause of candidiasis, yet few molecular tools are available. We adapted a recyclable nourseothricin resistance marker gene (SAT1) originally developed for use with C. albicans in order to generate gene knockouts from C. parapsilosis. We first replaced the promoters driving expression of the FLP recombinase and the SAT1 genes with the equivalent sequences from C. parapsilosis. We then used the cassette to generate a homozygous knockout of C. parapsilosis URA3. The ura3 knockouts have altered colony morphologies. We also knocked out both alleles of an ortholog of BCR1, a gene encoding a transcription factor known to be required for biofilm development in C. albicans. We show that C. parapsilosis BCR1 is necessary for biofilm development in C. parapsilosis and for expression of the cell wall protein encoded by RBT1. Our results suggest that there are significant similarities in the regulation of biofilms between the two species, despite the fact that C. parapsilosis does not generate true hyphae and that BCR1 regulates the expression of many hypha-specific adhesins in C. albicans.

Candida species are among the most common causes of nosocomial infection. Whereas C. albicans is generally the most common causative agent, several large-scale studies have shown that other Candida species are isolated with increasing frequency. C. parapsilosis is one species of concern, and in some cases, the incidence of bloodstream infection is similar to or exceeds that of C. albicans (3, 17, 34).

Infection with C. parapsilosis is most common in neonates, in transplant patients, and in patients receiving parenteral nutrition (1, 17, 29, 30, 40, 53). C. parapsilosis is frequently found on the hands of healthy individuals, including hospital workers (6, 20, 21). This is associated with periodic outbreaks of C. parapsilosis infections, including those in pediatric units in Spain, Italy, and Finland (4, 41, 46, 47) and in community hospitals in the United States (10, 13, 25).

The abilities of C. parapsilosis to adhere to indwelling medical devices and to form biofilms are strongly correlated with infection (7, 24, 48). Over the past few years, there has been a dramatic increase in our understanding of the molecular basis of biofilm formation by C. albicans (reviewed in reference 36). Development of biofilms is associated with the transition to hyphal growth, and mutants that are locked in the yeast form generally produce minimal biofilms (31, 42). Regulation of adhesins and cell wall proteins is also important (reviewed in reference 52). In contrast, very little is known about the signals regulating biofilm formation in C. parapsilosis. Unlike C. albicans, C. parapsilosis does not form true hyphae. Biofilms appear to consist of elongated yeast cells, and development is influenced by phenotype (26).

Genetic analysis of C. parapsilosis is hampered by the lack of suitable tools. The genome is diploid (14, 18, 27), and there is no apparent sexual cycle (33). Protocols for high-efficiency genetic transformation have been developed (19, 57), and cloning vectors have been constructed (39). However, to date, no methods for generating gene knockouts have been described. We describe here a method using the recyclable, dominant nourseothricin resistance marker (SAT1), based on protocols developed for gene disruption in C. albicans (43, 56). We used two rounds of integration to generate a homozygous ura3 mutant. We also disrupted an ortholog of the BCR1 gene, which has been shown to regulate biofilm development in C. albicans (35, 37). Disrupting C. parapsilosis BCR1 (CpBCR1) also inhibits the formation of biofilms, suggesting that similar pathways are required in the two species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Candida parapsilosis strains (Table 1) were grown routinely in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) at 30°C. For colony selection, 2% agar was added. For selection of transformants, nourseothricin (Werner Bioagents, Jena, Germany) was added to YPD at a final concentration of 200 μg ml−1. To recycle the SAT1-FLP cassette, transformants were grown in YPM medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% maltose) overnight, and approximately 100 cells were plated onto YPD plates supplemented with nourseothricin at 20 μg ml−1 and incubated at 30°C. Two sizes of colonies were readily seen after 48 h of growth at 30°C. The smaller colonies were picked and restreaked onto fresh YPD plates. URA3 mutants were examined by growth on synthetic complete (SC)-ura plates (0.67% yeast nitrogen base, 2% dextrose, 0.075% mixture of all amino acids except uridine, 2% agar). After electroporation, cells were allowed recover by growing on YPG media (1% yeast extract, 1% Bacto peptone, 2% dextrose) with 1 M sorbitol (19). The formation of biofilms by C. parapsilosis was tested with several media, and synthetic defined (SD) medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base) containing 50 mM dextrose was determined to yield the best results. C. albicans biofilms were grown in Spider medium (32). RNA was isolated using a Ribopure kit (Ambion) from mid-exponential cells grown in SD medium supplemented with 50 mM dextrose and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| C. parapsilosis CLIB214 | Wild type | Type strain |

| C. parapsilosis CD9 | URA3/ura3Δ::SAT1-FLP | This study, derived from CLIB214 |

| C. parapsilosis CD98 | URA3/ura3Δ::FRT | This study, derived from CD9 |

| C. parapsilosis CD982 | URA3::SAT1-FLP/ura3Δ::FRT | This study, derived from CD98 |

| C. parapsilosis CDU1 | ura3Δ::FRT/ura3Δ::FRT | This study, derived from CD982 |

| C. parapsilosis CDb25 | BCR1/bcr1Δ::SAT1-FLP | This study, derived from CLIB214 |

| C. parapsilosis CDb27 | BCR1/bcr1Δ::FRT | This study, derived from CDb25 |

| C. parapsilosis CDb38 | bcr1Δ::SAT1-FLP/bcr1Δ::FRT | This study, derived from CDb27 |

| C. parapsilosis CDb71 | bcr1Δ::FRT/bcr1Δ::FRT | This study, derived from CDb38 |

| C. parapsilosis CDb72 | bcr1Δ::FRT/bcr1Δ::SAT1-FLP-BCR1 | This study, derived from CDb71 |

| C. parapsilosis CDb89 | bcr1Δ::FRT/bcr1Δ::BCR1 | This study, derived from CDb72 |

| C. albicans CJN702 | ura3::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG::pHIS1 bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 | 35 |

| C. albicans CJN698 | ura3::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG::pHIS1-BCR1 bcr1::ARG4/bcr1::URA3 | 35 |

All sequences were obtained from the C. parapsilosis genome-sequencing project (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/sequencing/Candida/parapsilosis/).

Plasmid construction.

Plasmid pSFS2 was kindly provided as a gift by Joachim Morschhauser, Universitat Wurzburg, Germany. It contains the Candida albicans SAT1 nourseothricin resistance gene (CaSAT1) under the control of a Candida albicans ACT1 promoter and a recombinase FLP gene whose expression is driven from the CaMAL2 promoter gene (43). In this study, 443 bp of CpURA3 upstream sequences and 489 bp of CpURA3 downstream sequences were amplified by PCR from C. parapsilosis CLIB214 genomic DNA with primers But223 and But224 (containing restriction sites for ApaI and XhoI) and But221 and But222 (containing restriction sites for SacII and SacI). The PCR products were digested with the relevant enzymes and inserted into the flanking sites of pSFS2, generating plasmid pCD4. The entire fragment was excised from pCD4 and introduced into C. parapsilosis CLIB214, but no nourseothricin-resistant transformants were obtained.

The cassette from pSFS2 was altered for use with C. parapsilosis by replacing the CaMAL2 and CaACT1 promoters with equivalent sequences from C. parapsilosis. The CaSAT1 gene was amplified from plasmid pSFS2 using primers But231 and But232, containing recognition sites for XhoI and SacII, and cloned into the vector pRS403 (49). A 501-bp fragment of the CpACT1 upstream sequence, including the first 15 codons and the entire first intron, was amplified from C. parapsilosis CLIB214 using primers But233 and But234, containing recognition sites for XmaI and XhoI, and cloned upstream of the CaSAT1 gene. A fragment of CaFLP was then amplified using primers But230 and But235, containing recognition sites for EcoRI and XmaI, was cloned upstream of the CpACT1 promoter to produce plasmid pCD3. Plasmid pCD6 was generated by exchanging the EcoRI-SacII fragment of pCD3 (from the center of CaFLP1 to beyond the second FRT site) with that of pSFS2. A 548-bp fragment containing the C. parapsilosis MAL2 promoter sequence was amplified from CLIB214 using primers But227 and But228 containing recognition sites for BamHI and SalI and used to replace the CaMAL2 promoter in pCD6, generating the plasmid pCD8 (Fig. 1A).

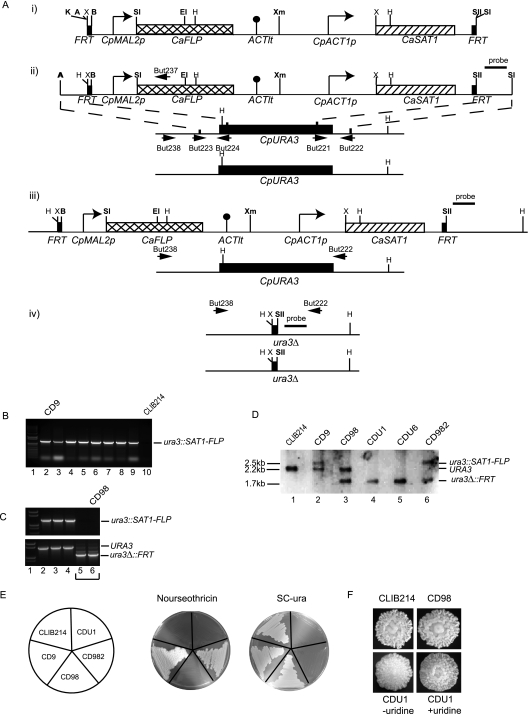

FIG. 1.

Construction of a Cpura3Δ strain. (A) (i) A disruption cassette was adapted from the SAT1 flipper system described by Reuss et al. (43) by replacing the MAL2 and ACT1 promoters with equivalent sequences from C. parapsilosis. (ii) Upstream and downstream sequences from CpURA3 were amplified using primer pairs But223/But224 and But221/But222 and inserted at the ApaI/XhoI and SacII/SacI sites surrounding the flipper cassette. (iii) The entire cassette and flanking regions were excised by digestion with ApaI and SacI and targeted to the CpURA3 alleles by homologous recombination. The figure shows the structure of the cassette integrated at one allele. (iv) The cassette was recycled from the first allele by induction of the FLP recombinase, inserted at the second allele and recycled once more. Restriction sites shown in bold are unique. A, ApaI; B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; SI, SacI; SII, SacII; Sl, SalI; X, XhoI; Xm, XmaI. (B) Insertion of the SAT1 cassette at the first CpURA3 allele was verified by PCR using primers But237 (from within the FLP gene) and But238 (from upstream of CpURA3, outside the range of the deletion). Lanes 2 to 9 show the presence of a 1.3-kb fragment in eight independent disruptants that is not present in the wild-type strain CLIB214 (lane 10). One (lane 2, strain CD9) was chosen to recycle the cassette. Lane 1 contains a molecular size marker (1 kb plus; Invitrogen). (C) Recycling of the SAT1-FLP cassette. PCR amplification using primers But237 and But238 shows that the strains in lanes 2, 3, and 4 have not lost the cassette, whereas those in lanes 5 and 6 have (top panel). This is confirmed in the bottom panel, which shows PCR amplification using the primer pair But238 and But222 surrounding CpURA3. The strains in lanes 2, 3, and 4 contain the wild-type CpURA3 allele (1.5 kb), whereas those in lanes 5 and 6 have the deleted allele (1.0 kb). One isolate (CD98) was chosen for disruption of the second allele. (D) The structure of the disruption was also confirmed by Southern hybridization using the probe indicated, derived from the downstream region of CpURA3. Genomic DNA was digested with HindIII. The probe hybridizes to one fragment of 2.2 kb (URA3) in the starting strain CLIB214 (lane 1), representing the wild-type allele. Introducing the cassette at one allele produces one larger band of 2.5 kb (ura3::SAT1-FLP) and one wild-type band (CD9, lane 2). Recycling the cassette results in a small fragment of 1.7 kb (ura3Δ::FRT), corresponding to the deleted allele, and a wild-type fragment (CD98, lane 3). The cassette was introduced at the second allele, generating both large (ura3::SAT1-FLP) and small (ura3Δ::FRT) fragments (CD982, lane 6). Recycling the cassette resulted in only one fragment, corresponding to the deleted CpURA3 allele (ura3Δ::FRT; CDU1 and CDU6, lanes 4 and 5). (E) The strains containing SAT1-FLP integrated at the first allele of CpURA3 (CD9) or the second allele (CD982) are resistant to nourseothricin (at 200 μg ml−1). All other strains are sensitive. The strains in which both alleles of CpURA3 were deleted (CDU1 and CDU6) failed to grow in the absence of uracil. (F) The phenotypes of the wild-type (CLIB214) and the heterozygote knockout strains (CD98) are the same when grown on YPD medium and resemble the crater phenotype described previously (26). The double-deletion strain (CDU1) has a different appearance, which reverts to the wild-type phenotype when excess uridine (50 μg ml−1) is added.

To knock out CpURA3, the entire adapted cassette from plasmid pCD8 was digested with BamHI and SacII, and the fragment was used to replace the equivalent region in pCD4, generating pCD10. The cassette and CpURA3-flanking sequences were excised by digestion with ApaI and SacI and transformed into C. parapsilosis CLIB214. The same construction was used to delete the second allele.

To generate deletions of CpBCR1, a 550-bp fragment was amplified from the upstream region using primers But257 and But258 (containing recognition sites for KpnI and ApaI), and a 502-bp fragment was amplified from the downstream region using primers But259 and But260 (containing recognition sites for SacII and SacI). These were introduced into the relevant sites of pCD8, generating plasmid pCD13. The entire cassette and CpBCR1 flanking sequences were excised by digesting with KpnI and SacI and transformed into C. parapsilosis CLIB214. The same construct was used to delete the second allele.

Plasmid pCD20 was constructed to reintroduce CpBCR1 at its original chromosomal location. The entire open reading frame of CpBCR1 together with 82 bp of upstream and 405 bp of downstream sequences was amplified using primers But273_SacII and But260, containing SacII and SacI restriction sites. The PCR fragment was cloned into plasmid pCD12, which contains a 550-bp fragment from the upstream region of CpBCR1, between the KpnI and ApaI sites of pCD8. The plasmid was linearized by digestion with SacI before electroporation.

Candida parapsilosis transformation.

C. parapsilosis strains were transformed by electroporation as described previously (57), with some modifications. Overnight cell culture was diluted to an A600 of 0.2 in 50 ml of fresh YPD and incubated at 30°C until the A600 reached approximately 2.0. Cells were then pelleted at 5,000 × g for 10 min, resuspended in 10 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM dithiothreitol, and incubated at 30°C for 1 h. Water (40 ml) was added, and cells were washed twice, first with 50 ml of ice-cold water and finally with 10 ml of ice-cold 1 M sorbitol. Finally, cells were resuspended in 125 μl of 1 M sorbitol. Approximately 1 μg of purified ApaI-SacI fragment from pCD10 or purified KpnI-SacI fragment from pCD13 was mixed with 50 μl of competent cells and transferred into a 1-mm electroporation cuvette. The reaction was carried out at 1.25 kV, using an Eppendorf 2510 electroporator. After electroporation, 950 μl of YPG medium containing 1 M sorbitol was added immediately, and the mixture was incubated at 30°C for 4 h. One hundred microliters was plated onto YPD plates supplemented with nourseothricin at a concentration of 200 μg ml−1. Transformants were obtained following 24 h of incubation at 30°C.

Candida parapsilosis genomic DNA extraction, PCR verification, and Southern blotting.

Genomic DNA was isolated as described previously (http://www.fhcrc.org/science/labs/breeden/Methods/genomic_DNAprep.html), except that cells were disrupted by using a bead beater. For PCR, 1 μg of genomic DNA was used. Genomic DNA (15 μg) treated with RNase at 10 μg μl−1 was used for Southern hybridization.

Screening of transformants carrying the SAT1-FLP cassette at CpURA3 was carried out using primers But237 and But238 (Table 2). Primer But237 binds within the FLP recombinase gene, and But238 binds upstream of the flanking region of the CpURA3 gene (Fig. 1A). Integration at CpURA3 yields a 1,280-bp PCR product that is not present in the wild-type or the recycled strain (Fig. 1B). Primers But222 and But238 were used to verify recycling of the SAT1-FLP cassette and deletion of the CpURA3 gene. The wild-type CpURA3 allele generates a 1.5-kb product, and recycled strains produce a smaller sized product of approximately 1 kb (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| But221 | GGGGCCGCGGTGGCTGGAATGCATACTTGA |

| But222 | GGGGGAGCTCTGCAGCGATTAGAGAGGTACAA |

| But223 | GGGGGGGCCCTGAACAAGGAATTGGGTTCG |

| But224 | CGATAGCTCGAGTAGGGGAAGAATAGTTTC |

| But227 | GGGGGGATCCGAATGGATGCGGGGGAGCGCG |

| But228 | GGGGGTCGACAATAGTTGTAGTAGTATTGG |

| But230 | GGGGCCCGGGATTTTATGATGGAATGAATG |

| But231 | GGGGCTCGAGATGAAAATTTCGGTGATGGGTG |

| But232 | GGGGGGGCCCGAGCTCCACCGCGGTGGCGGCC |

| But233 | GGGGCCCGGGGAAGACCGTCCAACTCTTGACG |

| But234 | GGGGCTCGAGACCGTTATCGATAACTAAAGCAG |

| But235 | GGGGGGATCCGAGGAATTCTGAACCAGTCC |

| But237 | GCTGTTCCGTTATGTGTAATCATCC |

| But238 | GTATTGCAAACAAACGGGTTCTTGT |

| But257 | GGGGGGTACCCAACCCACCTACCGTACACT |

| But258 | GGGGGGGCCCGATGAGACGAGTAGTGGTGG |

| But259 | GGGGCCGCGGTACTGCGAGCACTTCCATGA |

| But260 | GGGGGAGCTCTCCCGTTGGTTCTGTTTTGT |

| But261 | ACAGCACACAACACACAACGCTGTG |

| But262 | GTGGTGCTCTTAGCGAAGGTAAAGG |

| But273 | AAAACACACCGGTGAACGAC |

| But274 | TTCCACCACCATTGACAAGA |

| But273_SacII | GGGGCCGCGGCCTCCTACACCAGCCAACAT |

| BUT297 | TTCATCTGATACTGATTTCCTGTCA |

| BUT298 | TGGTAGTTGGTGATGTAATAGCAGA |

| BUT299 | ACGATCTACAAAATCTGCTATCGAC |

| BUT300 | CGTTTCCAGTTTCAATGTTACTTCT |

| BUT301 | TTCATCTTTATGGAAAAAGTGCTTC |

| BUT302 | GATCAAAAGATTTAACAAAGCTCCA |

Transformants carrying the SAT1-FLP cassette at CpBCR1 were identified using primers But237 and But261, which amplify a 1.5-kb fragment from within the FLP recombinase gene to upstream of CpBCR1 (Fig. 2). The presence of an intact CpBCR1 allele was confirmed by using primers But261 and But262, which amplify an 0.8-kb internal fragment. Primers But257 and But260 were used to verify recycling of the SAT1-FLP cassette and deletion of the CpURA3 gene. The wild-type CpBCR1 allele generates a 3.0-kb product, and recycled strains produce a smaller sized product of approximately 1 kb.

FIG. 2.

Construction of a Cpbcr1Δ strain. (A) Upstream and downstream sequences from CpBCR1 were amplified using primer pairs But257/But258 and But259/But260 and inserted at the KpnI/ApaI and SacII/SacI sites surrounding the SAT flipper cassette. The entire cassette and flanking regions were excised by digestion with KpnI and SacI and targeted to the CpBCR1 alleles by homologous recombination. The cassette was recycled from the first allele by induction of the FLP recombinase, inserted at the second allele, and recycled once more. Restriction sites shown in bold are unique. A, ApaI; B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; SI, SacI; SII, SacII; Sl, SalI; X, XhoI; Xm, XmaI. The CpBCR1 gene was reintroduced at one deletion allele by inserting a 550-bp fragment from the CpBCR1 promoter (plus 45 codons) upstream of the SAT1-FLP cassette and the entire open reading frame (including 82 bp of the promoter) downstream of the cassette. The cassette was removed by recombination between the FRT sites, as described before. (B) Construction of the deletion was confirmed by PCR using three different primer combinations. The order of the strains for each reaction is as follows: lane 1, CLIB214; lane 2, CDb25 (first integration); lane 3, CDb27 (first recycle); lane 3, CDb38 (second integration); lane 5, CDb71 (second recycle). Amplification with primers But261/But237 generates a 1.5-kb fragment from within the FLP gene to upstream of BCR1. Primers But261/But262 amplify a 0.8-kb fragment from the 5′ region of the BCR1 gene. Primers But257/But260 amplify a 3.0-kb fragment from the wild-type BCR1 allele and a 1-kb fragment from the bcr1Δ allele. (C) The structure of the disruption was also confirmed by Southern hybridization using a probe derived from the downstream region of CpBCR1. Genomic DNA was digested with HindIII. The probe hybridizes to one 4.5-kb fragment (BCR1) in the starting strain, CLIB214 (lane 1), representing the wild-type allele. Introducing the cassette at one allele produces one smaller band of 2.0 kb (bcr1::SAT1-FLP) and one wild-type band (CDb25, lane 2). Recycling the cassette results in a fragment of 2.6 kb (bcr1Δ::FRT), corresponding to the deleted allele, and a wild-type fragment (CDb27, lane 3). The cassette was introduced at the second allele, generating both 2.0-kb (bcr1::SAT1-FLP) and 2.6-kb (bcr1Δ::FRT) fragments (CDb38, lane 4). Recycling the cassette results in only one fragment, corresponding to the deleted BCR1 allele (bcr1Δ::FRT; CDb71, lane 5). (D) Reintegration of the CpBCR1 gene at one deletion allele was confirmed by PCR. Amplification with primers But261/But237 generates a 1.5-kb fragment from within the FLP gene to upstream of BCR1 in CDb72 (containing the SAT1-FLP cassette and the entire CpBCR1 gene), with no amplification from the double-deletion (CDb71) or from the reconstituted strain following recycling of the SAT1 cassette. Primers But261/But237 amplify a 0.8-kb fragment from within the CpBCR1 gene before and after recycling the cassette (CDb72 and CDb89) but not in the deletion strain (CDb71).

Transformants carrying the intact CpBCR1 gene and the SAT1-FLP cassette integrated in a double-deletion strain were identified using primers But237 and But261, as described previously. Recycling of the cassette was verified using primers But273 and But274, which amplify a 0.8-kb fragment from within CpBCR1.

Southern hybridizations were also used to verify the structure of the deletions in selected transformants, using approximately 20 μg of RNase-treated genomic DNA digested with HindIII. For CpURA3, a probe was amplified from CLIB214 by using primers But221 and But222, which binds to a region of CpURA3 downstream from the integration site (Fig. 1A). For CpBCR1, a probe was amplified using primers But259 and But260 (Fig. 2A).

Biofilm growth conditions and dry weight measurements.

Biofilms were grown on silicone squares as described in the reports by Richard et al. (44) and Nobile and Mitchell (37). Silicone squares (1.5 cm by 1.5 cm) were cut from sheets (Cardiovascular Instruments) and autoclaved. The squares were then placed in a 12-well plate and pretreated by the addition of 2 ml of FCS and incubated with shaking at 37°C overnight. The silicone was then washed with 2 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer to remove the residual FCS and moved to a new 12-well plate.

Overnight cultures of C. parapsilosis grown in YPD were washed twice with equivalent volumes of PBS buffer and then diluted to an A600 of 1 in SD medium with 50 mM glucose. C. albicans cultures were grown in Spider medium and treated similarly. Cultures (3 ml) were added to the 12-well plate containing the pretreated silicone. The plate was incubated on a rotor at 37°C for 2 h (initial adhesion phase) with gentle shaking. The medium was removed, and the silicone was gently washed with 2 ml of PBS buffer. Fresh SD or Spider medium (3 ml) was added into the 12-well plates, and they were incubated with gentle agitation on a rotary shaker at 37°C for 48 h. The resulting biofilms were photographed.

The dry weight of the saturated biofilms was measured as follows. After 48 h, the SD and Spider media were carefully removed from the 12-well-plates, and the silicone squares were placed in a 50-ml centrifuge tube. PBS buffer (10 ml) was added to each tube, and the mixture was vortexed for 30 s. The solutions containing the biofilm cells were then filtered through predried cellulose membrane filter paper (47-mm diameter, 0.45-μm pore size). The silicone squares were washed twice with PBS. The filter papers were dried at 37°C for 24 h, and the dry weight was then calculated. The dry weight was measured for six independent replicates of all isolates tested.

Confocal scanning laser microscopy.

Biofilms were visualized using confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM), essentially as described by Nobile et al. (35). Biofilms on silicone squares were stained with 25 μg ml−1 concanavalin A (conA)-Alexa Fluor 594 conjugate (C-11253; Bio-science) for 45 min at 37°C. The liquid was then removed from each well, and the silicone squares were flipped and placed on a 35-mm-diameter glass-bottomed petri dish (MatTek Corp., Ashland, MA). The biofilms were observed with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal scanning microscope equipped with Plan-Neofluar ×20-magnification/0.5-numerical aperture (for measuring depth) and ×40-magnification/1.3-numerical aperture (for image acquisition) oil objectives. A HeNe1 laser was used to excite at a 543-nm wavelength. All images were captured using a Zeiss LSM Image Browser.

RT-PCR.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed as described previously (22). Optimum cycle numbers were determined for each primer pair. Expression of CpBCR1 generates a product of 800 bp with primers But273 and But274; the ALS1 product is 224 bp with primers But297 and But298, the ALS3 product is 209 bp with primers But299 and But300, and the product from RBT1 is 237 bp with primers But301 and But 302. ACT1 was amplified using primers But33 and But34 (45).

RESULTS

Generating a cassette-based gene knockout system for C. parapsilosis.

The gene knockout system described here is based on a recyclable cassette containing a dominant selectable marker (SAT1), first developed and adapted for use with C. albicans (56, 43). The entire cassette is flanked with direct repeats (FRT) containing the recognition site for the FLP recombinase, allowing easy recycling.

We first attempted to apply the C. albicans SAT1 cassettes directly to C. parapsilosis. Fragments from upstream and downstream of CpURA3 were amplified by PCR inserted at either end of the cassette in plasmid pSFS2. However, we failed to obtain any nourseothricin-resistant transformants when we attempted to introduce the cassette into C. parapsilosis.

We then replaced the promoters driving the expression of the FLP and SAT1 genes with equivalent sequences from C. parapsilosis (Fig. 1). A 548-bp fragment from upstream of the C. parapsilosis MAL2 ortholog is used to drive expression of FLP, and a 501-bp fragment from the C. parapsilosis ACT1 promoter controls expression of CaSAT1 (Fig. 1A). The entire fragment, including the cassette and the flanking regions from CpURA3, was isolated by digestion with ApaI and SacI and was transformed into C. parapsilosis CLIB214 by electroporation. Nourseothricin-resistant colonies were obtained after 48 h of growth on YPD agar plates containing 200 μg ml−1 nourseothricin.

Eight transformants were screened for the correct integration by PCR, using primer But237, derived from within the CaFLP gene, and primer But238, from upstream of the CpURA3 gene (outside the range of a deletion). Amplification of a 1.3-kb fragment indicated that the cassette had integrated at the correct chromosomal location in all (Fig. 1B). One transformant (CD9) was inoculated into YPM medium without nourseothricin to allow excision of the SAT1 cassette. As suggested by Reuss et al. (43), we plated the mixture on YPD agar plates containing a low level of nourseothricin (20 μg ml−1). Sensitive colonies grow slowly on this medium within 48 h. Several small colonies were screened by PCR to identify isolates in which the cassette has been lost (Fig. 1C). Primers But237 and But238 were used to confirm the loss of the cassette in two isolates (Fig. 1C, lanes 5 and 6, upper panel), and But238 and But222 from upstream and downstream of CpURA3 confirmed that the deleted URA3 allele is smaller in the same isolates (Fig. 1C, lanes 5 and 6, lower panel). We expected But238 and But222 to also amplify the second intact CpURA3 allele in these strains, but the smaller fragment was preferentially amplified. One isolate (CD98) was chosen to repeat the process to delete the second allele. We also confirmed the structure of the deletions by using Southern hybridization. A downstream region of CpURA3 used as a probe detects a single fragment from both alleles in the wild-type strain CLIB214, one wild-type allele and one increased in size when the cassette is integrated at the second allele in strain CD9, and one wild-type allele and one small fragment following loss of the cassette in CD98. Integration of the cassette at the second CpURA3 allele is shown in Fig. 1D, lane 6 (isolate CD982) and the loss of the cassette, leaving two deleted CpURA3 alleles, in Fig. 1D, lanes 4 and 5 (isolates CDU1 and CDU6).

The isolates deleted for both alleles of CpURA3 failed to grow in the absence of uracil, as expected (Fig. 1E). We also noticed that the homozygous ura3 knockout strains differed in phenotype from that of the heterozygote knockout and the wild-type strain (Fig. 1F). Colonies from ura3 strains have a different appearance in the center. This occurred as soon as the cassette was introduced into the second allele and was observed for several independent constructs (not shown). The phenotype was rescued by the addition of uridine at 50 μg ml−1 (Fig. 1F).

Construction of a bcr1Δ in C. parapsilosis.

The BCR1 gene in C. albicans was identified from a screen of transcription factor mutants and shown to be required for biofilm development (37). We identified an ortholog of CaBCR1 in the genome of C. parapsilosis (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We therefore deleted both alleles of CpBCR1 using the SAT1 flipper cassette described above (Fig. 2). The wild-type CpBCR1 gene was also reintroduced into the double-deletion strain, again using the SAT1 flipper cassette.

The effect of the Cpbcr1Δ on biofilm formation was tested as described by Nobile and Mitchell (37). Silicone squares treated with FCS were placed in a sterile 12-well plate and inoculated with strains grown in SD medium. As shown in Fig. 3A, the wild-type C. parapsilosis strain generates biofilms on the silicone. The Cpbcr1Δ/Cpbcr1Δ strain, however, does not adhere to the silicone, and most of the growth is confined to the surrounding liquid medium, resembling that of the Cabcr1Δ strain. The heterozygote C. parapsilosis knockout, where only one BCR1 allele has been deleted, and the reconstituted strain (where BCR1 has been reintroduced into the genome) both generate biofilms comparable to that of the wild type (Fig. 3). We compared the biofilms to those generated by C. albicans strains in which BCR1 has been deleted and reconstituted (35). The reductions of biofilm are similar for strains carrying the bcr1 deletions in both species (Fig. 3) (35, 37).

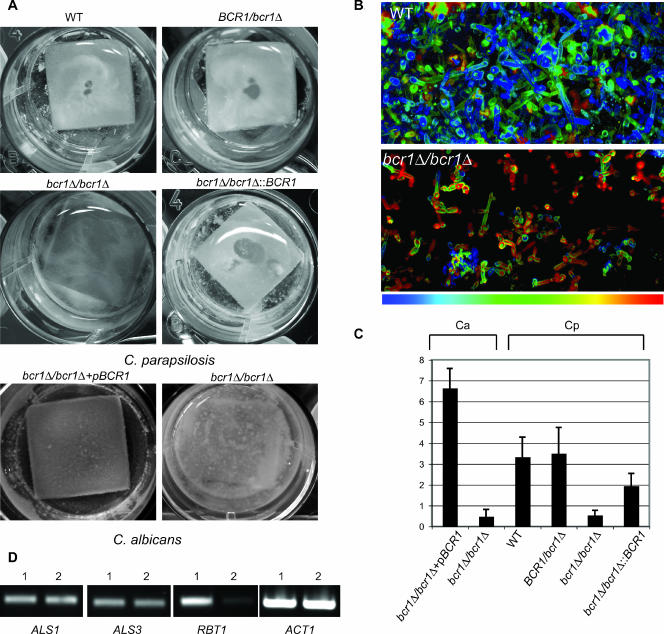

FIG. 3.

Disrupting bcr1 impairs biofilm development. (A) C. parapsilosis wild-type (CLIB214), BCR1/bcr1Δ heterozygote (CDb27), bcr1Δ/bcr1Δ homozygote (CDb71), and reconstituted BCR1 (CDb89) strains were grown for 48 h in SD medium on silicone squares placed at the bottom of 12-well plates. Adherence to the silicone was monitored by photography and compared to that of the biofilms generated by C. albicans BCR1 reconstituted (CJN698) and bcr1/bcr1 disruption (CJN702) strains grown in Spider medium. Disrupting bcr1 greatly reduces biofilm formation in both species. (B) CLSM depth views. Biofilms were stained with conA and visualized by using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal scanning microscope, and false-color depths were constructed. Blue cells are closest to the silicone, and red cells are farthest away. The wild-type (C. parapsilosis CLIB214) biofilms are approximately 100 μm deep, and the bcr1Δ (C. parapsilosis CDb71) biofilms are approximately 20 μm deep. (C) The biomass of the biofilms generated was determined by measuring the dry weight. Averages of six biological replicates are shown. Ca, C. albicans; Cp, C. parapsilosis. Phenotypes are represented by strains as follows: bcr1Δ/bcr1Δ+pBCR1, C. albicans CJN698; bcr1Δ/bcr1Δ, C. albicans CJN702; wild type (WT), C. parapsilosis CLIB214; BCR1/bcr1Δ, C. parapsilosis CDb27; bcr1Δ/bcr1Δ, C. parapsilosis CDb71; bcr1Δ/bcr1Δ::BCR1, C. parapsilosis CDb89. The differences between the biofilms from wild-type and bcr1 knockouts (P < 0.0001) and reconstituted and bcr1 knockouts (P = 0.003) in C. parapsilosis are statistically significant (t test, two-tailed P value). (D) Expression levels of ALS1, ALS3, and RBT1 were compared in the C. parapsilosis wild-type (1, CLIB214) and C. parapsilosis bcr1Δ (2, CDb71) strains using RT-PCR. Actin levels (ACT1) were measured as a control.

We used confocal microscopy to further investigate the differences in biofilm production between the wild-type and knockout strains (Fig. 3B). Wild-type C. parapsilosis cells labeled with concanavalin A adhere to the silicone, generating a dense matrix consisting of yeast and pseudohyphal cells. There are no hyphal cells present. The Cpbcr1 deletion strain, in contrast, generates biofilms with very few cells. Pseudohyphal cells, however, are clearly present, indicating that the knockout does not affect the transition to pseudohyphae. We estimate that the wild-type biofilms have a depth of >100 μm and that the biofilms generated by the Cpbcr1 knockout are approximately 20 μm deep.

The biofilm mass was determined by using dry weight measurements (Fig. 3C). The biofilms generated by C. parapsilosis CLIB214 do contain as much mass as those generated by C. albicans CJN698, even though the medium used was selected to maximize growth of both species. Deleting BCR1 reduces the biofilm mass in both. Reintroducing CpBCR1 at its original locus does restore biofilm development but not to the same extent as that in the wild-type strain or the heterozygote. The reconstituted strain contains an FRT site in the promoter of the CpBCR1 gene and a small duplication of the first 45 codons (Fig. 2). The presence of the FRT site is unavoidable with the reconstitution strategy used, chosen because we found it was impossible to clone the intact gene in Escherichia coli. We confirmed by RT-PCR that the reconstituted strain expresses CpBCR1 but at a lower level than the wild-type or the heterozygote knockout strain (not shown).

In C. albicans, BCR1 regulates the expression of at least 11 cell surface proteins or cell wall modification enzymes, including the hyphal wall protein encoded by HWP1 and the ALS3 adhesin gene (37). We could not identify an ortholog of HWP1 in C. albicans, but we did identify a close relative that is a member of the same family (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This is most likely an ortholog of RBT1 from C. albicans (8). There are four potential members of the ALS adhesin gene family in C. parapsilosis, and we tentatively identified two as ALS1 and ALS3 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Deleting Cpbcr1 greatly reduces the expression of RBT1, but it has no noticeable effect on the expression of ALS1 or ALS3 (Fig. 3D).

DISCUSSION

Developing tools for generating gene disruptions greatly facilitated our understanding of the biology and pathogenesis of C. albicans. One of the first systems developed was the Ura-blaster method, consisting of a URA3 cassette flanked by direct repeats of a 1.1-kb fragment from the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium hisG sequence (16). Recycling of the cassette was enabled by growth on 5′-fluoroorotic acid, which is toxic to Ura+ cells. The major disadvantage of this system relates to the use of the URA3 marker gene. Homozygous recycled disruptants are Ura−, which affects phenotypes such as virulence and adhesion (2, 23). Restoring the URA3 gene at a different chromosomal location often does not complement the defect, leading to confusion about the interpretation of the role of the target gene (28, 50). This has led to a reevaluation of the virulence phenotypes of several disruptions, including NOT3, BUR1, KEL1, and HWP1 (9, 51). The Ura-blaster method was adapted to allow amplification of the cassette by PCR by replacing the hisG sequences with smaller 200-bp direct repeats (54).

One of the difficulties is the necessity of carrying out two rounds of allele disruption, as the genome is diploid. Wilson et al. (55) first used two nonrecyclable markers (URA3 and HIS1) to disrupt both alleles of two genes in the RIM101 pathway. Simultaneous disruption was facilitated by the construction of the UAU1 (ura3-ARG4-ura3) cassette, which contains a copy of the ARG4 gene that, when removed by recombination, leaves an intact copy of URA3 (15). Homozygous disruptions are selected by growth on Arg− Ura− medium, which requires the presence of an intact cassette at one allele and a recombined cassette at the other (or the generation of triplication derivatives). The cassette was subsequently adapted for use in large-scale mutagenesis by incorporation into a Tn7 transposon (11). The potential difficulties of using URA3 as a marker were addressed by Noble and Johnson (38), who constructed a set of His−, Leu−, and Arg− auxotrophic strains and associated HIS1, LEU2, and ARG4 cassettes from species other than C. albicans. Homozygous disruptants are generated through simultaneous selection for two markers. A Cre-lox-based system using ARG4 and HIS1 has also been reported (12).

One drawback of all these methods is that they require well-characterized auxotrophic strains, which may also affect certain phenotypes. This can be circumvented by using dominant selectable markers, such as MPAr and SAT1. We therefore decided to adapt the cassettes developed by Reuss et al. (43), as we had no success applying the C. albicans constructs directly to C. parapsilosis. By driving expression of the FLP recombinase from the CpMAL2 promoter and the SAT1 marker from CpACT1, we successfully generated disruptions of URA3 and BCR1 in the C. parapsilosis type strain CLIB214. The frequency of homologous integration is high: 100% of the nourseothricin-resistant colonies tested contained the cassette at the targeted region for the first integration. The system has the advantage that the disruptants are almost genetically identical to the wild-type strain, apart from the excision of the target gene and the presence of a single FRT repeat.

One disadvantage is that the method is slow: the cassette is too large to amplify by PCR, meaning the flanking regions must be inserted by cloning. Each allele must be disrupted sequentially following recycling of the SAT1 marker. One of the goals in generating the CpURA3 disruption was to allow the use of auxotrophic selectable markers. However, disrupting URA3 changed the phenotype of the strain (Fig. 1F), suggesting it may also have additional effects. The phenotypic change is complemented by the addition of extra uridine, suggesting it is a direct result of the disruption. As with C. albicans, it is therefore inadvisable to use URA3 in a disruption cassette in C. parapsilosis, unless URA3 is replaced at its native position. However, construction of the Ura− strain will allow the use of URA3-based replicating plasmids. The same approach can also be applied to generating isogenic knockouts of other markers, such as HIS1, TRP1, and ARG4.

Because infection with C. parapsilosis is associated with biofilm formation (24, 48), we decided to test the effect of knocking out a candidate gene required for biofilms. We chose BCR1 because it was shown to be necessary for biofilm development in C. albicans and yet does not affect hyphal growth under most conditions (37). C. parapsilosis does not generate true hyphae, and it is therefore likely that some mutants affecting the hyphal transition will influence biofilm development in C. albicans and not in C. parapsilosis. We showed that both species require BCR1 for biofilm development.

CLSM images of C. albicans biofilms show that the basal layer consists of mostly yeast cells topped by a layer of pseudohyphal and hyphal cells (42, 44). Long hyphae project even further from the surface. In contrast, C. parapsilosis biofilms have been described as clumped blastospores (24). We have previously shown by light microscopy that C. parapsilosis cells form pseudohyphae when adhered to plastic surfaces (26). Here, we confirm using CSLM that biofilms formed by the type strain of C. parapsilosis are a mixture of pseudohyphae and yeast cells. Unlike C. albicans (not shown), the C. parapsilosis cells exhibit some autofluorescence, affecting the quality of the image. However, it is clear that there are pseudohyphae present both in the basal layer and projecting away from the surface. Deleting Cpbcr1 reduces the number of adhered cells but does not affect the formation of pseudohyphae. It is therefore likely that BCR1 is required at an early stage of biofilm formation in both C. albicans and C. parapsilosis (5).

In C. albicans, BCR1 regulates the expression of a number of cell wall and adhesin genes, including members of the ALS family, HWP1, and the chitinase gene (CHT2) (35, 37). As these are predominantly expressed in hyphal cells, it has been suggested that BCR1 regulates the adhesive properties of hyphal cells (37). The C. parapsilosis genome encodes orthologs of many of the C. albicans targets, including some of the ALS family and relatives of HWP1 (from http://www.sanger.ac.uk/sequencing/Candida/parapsilosis/). The closest match to CaHWP1 in C. parapsilosis is most likely to be an ortholog of RBT1 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We showed that CpBCR1 is required for the expression of RBT1, but it has no noticeable effect on the expression of two ALS genes. However, there are several members of the Als family of GPI-linked proteins in C. albicans, and only some are regulated by BCR1 (37). It is difficult to absolutely assign orthology to the Als family members in C. parapsilosis at present, and it is possible that the expression of some is indeed regulated by BCR1. We are presently actively developing whole-genome microarrays for C. parapsilosis, and we look forward to identifying all targets in C. parapsilosis and to comparing the activities and functions of the BCR1 orthologs in both species. It is possible that BCR1 controls adhesion through the regulation of gene expression in yeast cells in both species. It is also likely that both BCR1 function and biofilm development in the two species have some shared and some different aspects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Aaron Mitchell for providing the C. albicans bcr1 disruption strains, Joachim Morschhauser for the SAT1-FLP cassette, and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for access to the C. parapsilosis genome sequence. We also gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ann Cullen for generating the confocal images.

This work was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland and the Health Research Board.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 June 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://ec.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almirante, B., D. Rodriguez, M. Cuenca-Estrella, M. Almela, F. Sanchez, J. Ayats, C. Alonso-Tarres, J. L. Rodriguez-Tudela, and A. Pahissa. 2006. Epidemiology, risk factors, and prognosis of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections: case-control population-based surveillance study of patients in Barcelona, Spain, from 2002 to 2003. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:1681-1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bain, J. M., C. Stubberfield, and N. A. Gow. 2001. Ura-status-dependent adhesion of Candida albicans mutants. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 204:323-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakir, M., N. Cerikcioglu, R. Barton, and A. Yagci. 2006. Epidemiology of candidemia in a Turkish tertiary care hospital. APMIS 114:601-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barchiesi, F., G. Caggiano, L. Falconi Di Francesco, M. T. Montagna, S. Barbuti, and G. Scalise. 2004. Outbreak of fungemia due to Candida parapsilosis in a pediatric oncology unit. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 49:269-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankenship, J. R., and A. P. Mitchell. 2006. How to build a biofilm: a fungal perspective. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:588-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonassoli, L. A., M. Bertoli, and T. I. Svidzinski. 2005. High frequency of Candida parapsilosis on the hands of healthy hosts. J. Hosp. Infect. 59:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branchini, M. L., M. A. Pfaller, J. Rhine-Chalberg, T. Frempong, and H. D. Isenberg. 1994. Genotypic variation and slime production among blood and catheter isolates of Candida parapsilosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:452-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, B. R., W. S. Head, M. X. Wang, and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Identification and characterization of TUP1-regulated genes in Candida albicans. Genetics 156:31-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng, S., M. H. Nguyen, Z. Zhang, H. Jia, M. Handfield, and C. J. Clancy. 2003. Evaluation of the roles of four Candida albicans genes in virulence by using gene disruption strains that express URA3 from the native locus. Infect. Immun. 71:6101-6103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark, T. A., S. A. Slavinski, J. Morgan, T. Lott, B. A. Arthington-Skaggs, M. E. Brandt, R. M. Webb, M. Currier, R. H. Flowers, S. K. Fridkin, and R. A. Hajjeh. 2004. Epidemiologic and molecular characterization of an outbreak of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections in a community hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4468-4472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis, D. A., V. M. Bruno, L. Loza, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2002. Candida albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 162:1573-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dennison, P. M., M. Ramsdale, C. L. Manson, and A. J. Brown. 2005. Gene disruption in Candida albicans using a synthetic, codon-optimised Cre-loxP system. Fungal Genet. Biol. 42:737-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diekema, D. J., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. P. Wenzel, and M. A. Pfaller. 1997. An outbreak of Candida parapsilosis prosthetic valve endocarditis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:147-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doi, M., M. Homma, A. Chindamporn, and K. Tanaka. 1992. Estimation of chromosome number and size by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in medically important Candida species. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:2243-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enloe, B., A. Diamond, and A. P. Mitchell. 2000. A single-transformation gene function test in diploid Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 182:5730-5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridkin, S. K., D. Kaufman, J. R. Edwards, S. Shetty, and T. Horan. 2006. Changing incidence of Candida bloodstream infections among NICU patients in the United States: 1995-2004. Pediatrics 117:1680-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fundyga, R. E., R. J. Kuykendall, W. Lee-Yang, and T. J. Lott. 2004. Evidence for aneuploidy and recombination in the human commensal yeast Candida parapsilosis. Infect. Genet. Evol. 4:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gacser, A., S. Salomon, and W. Schafer. 2005. Direct transformation of a clinical isolate of Candida parapsilosis using a dominant selection marker. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245:117-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hedderwick, S. A., M. J. Lyons, M. Liu, J. A. Vazquez, and C. A. Kauffman. 2000. Epidemiology of yeast colonization in the intensive care unit. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:663-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, Y. C., T. Y. Lin, H. S. Leu, J. L. Wu, and J. H. Wu. 1998. Yeast carriage on hands of hospital personnel working in intensive care units. J. Hosp. Infect. 39:47-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly, M. T., D. M. MacCallum, S. D. Clancy, F. C. Odds, A. J. Brown, and G. Butler. 2004. The Candida albicans CaACE2 gene affects morphogenesis, adherence and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 53:969-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirsch, D. R., and R. R. Whitney. 1991. Pathogenicity of Candida albicans auxotrophic mutants in experimental infections. Infect. Immun. 59:3297-3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhn, D. M., J. Chandra, P. K. Mukherjee, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2002. Comparison of biofilms formed by Candida albicans and Candida parapsilosis on bioprosthetic surfaces. Infect. Immun. 70:878-888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhn, D. M., P. K. Mukherjee, T. A. Clark, C. Pujol, J. Chandra, R. A. Hajjeh, D. W. Warnock, D. R. Soll, and M. A. Ghannoum. 2004. Candida parapsilosis characterization in an outbreak setting. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1074-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laffey, S. F., and G. Butler. 2005. Phenotype switching affects biofilm formation by Candida parapsilosis. Microbiology 151:1073-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lasker, B. A., G. Butler, and T. J. Lott. 2006. Molecular genotyping of Candida parapsilosis group I clinical isolates by analysis of polymorphic microsatellite markers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:750-759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lay, J., L. K. Henry, J. Clifford, Y. Koltin, C. E. Bulawa, and J. M. Becker. 1998. Altered expression of selectable marker URA3 in gene-disrupted Candida albicans strains complicates interpretation of virulence studies. Infect. Immun. 66:5301-5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin, A. S., S. F. Costa, N. S. Mussi, M. Basso, S. I. Sinto, C. Machado, D. C. Geiger, M. C. Villares, A. Z. Schreiber, A. A. Barone, and M. L. Branchini. 1998. Candida parapsilosis fungemia associated with implantable and semi-implantable central venous catheters and the hands of healthcare workers. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy, I., L. G. Rubin, S. Vasishtha, V. Tucci, and S. K. Sood. 1998. Emergence of Candida parapsilosis as the predominant species causing candidemia in children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1086-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis, R. E., H. J. Lo, Raad, I. I., and D. P. Kontoyiannis. 2002. Lack of catheter infection by the efg1/efg1 cph1/cph1 double-null mutant, a Candida albicans strain that is defective in filamentous growth. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1153-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, H., J. Kohler, and G. R. Fink. 1994. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science 266:1723-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Logue, M. E., S. Wong, K. H. Wolfe, and G. Butler. 2005. A genome sequence survey shows that the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis has a defective MTLa1 allele at its mating type locus. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1009-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamura, T., and H. Takahashi. 2006. Epidemiological study of Candida infections in blood: susceptibilities of Candida spp. to antifungal agents, and clinical features associated with the candidemia. J. Infect. Chemother. 12:132-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nobile, C. J., D. R. Andes, J. E. Nett, F. J. Smith, F. Yue, Q. T. Phan, J. E. Edwards, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2006. Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesins in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2:e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nobile, C. J., and A. P. Mitchell. 2006. Genetics and genomics of Candida albicans biofilm formation. Cell. Microbiol. 8:1382-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nobile, C. J., and A. P. Mitchell. 2005. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr. Biol. 15:1150-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noble, S. M., and A. D. Johnson. 2005. Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 4:298-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nosek, J., L. Adamikova, J. Zemanova, L. Tomaska, R. Zufferey, and C. B. Mamoun. 2002. Genetic manipulation of the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis. Curr. Genet. 42:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasqualotto, A. C., W. L. Nedel, T. S. Machado, and L. C. Severo. 2005. A 9-year study comparing risk factors and the outcome of paediatric and adults with nosocomial candidaemia. Mycopathologia 160:111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Posteraro, B., S. Bruno, S. Boccia, A. Ruggiero, M. Sanguinetti, V. Romano Spica, G. Ricciardi, and G. Fadda. 2004. Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infection in pediatric oncology patients: results of an epidemiologic investigation. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 25:641-645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramage, G., K. VandeWalle, J. Lopez-Ribot, and B. Wickes. 2002. The filamentation pathway controlled by the Efg1 regulator protein is required for normal biofilm formation and development in Candida albicans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 214:95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reuss, O., A. Vik, R. Kolter, and J. Morschhauser. 2004. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richard, M. L., C. J. Nobile, V. M. Bruno, and A. P. Mitchell. 2005. Candida albicans biofilm-defective mutants. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1493-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossignol, T., M. E. Logue, K. Reynolds, M. Grenon, N. F. Lowndes, and G. Butler. 2007. Analysis of the transcriptional response of Candida parapsilosis following exposure to farnesol. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2304-2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.San Miguel, L. G., J. Cobo, E. Otheo, A. Sanchez-Sousa, V. Abraira, and S. Moreno. 2005. Secular trends of candidemia in a large tertiary-care hospital from 1988 to 2000: emergence of Candida parapsilosis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 26:548-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saxen, H., M. Virtanen, P. Carlson, K. Hoppu, M. Pohjavuori, M. Vaara, J. Vuopio-Varkila, and H. Peltola. 1995. Neonatal Candida parapsilosis outbreak with a high case fatality rate. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 14:776-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shin, J. H., S. J. Kee, M. G. Shin, S. H. Kim, D. H. Shin, S. K. Lee, S. P. Suh, and D. W. Ryang. 2002. Biofilm production by isolates of Candida species recovered from nonneutropenic patients: comparison of bloodstream isolates with isolates from other sources. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1244-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Heiter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Staab, J. F., and P. Sundstrom. 2003. URA3 as a selectable marker for disruption and virulence assessment of Candida albicans genes. Trends Microbiol. 11:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundstrom, P., J. E. Cutler, and J. F. Staab. 2002. Reevaluation of the role of HWP1 in systemic candidiasis by use of Candida albicans strains with selectable marker URA3 targeted to the ENO1 locus. Infect. Immun. 70:3281-3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verstrepen, K. J., and F. M. Klis. 2006. Flocculation, adhesion and biofilm formation in yeasts. Mol. Microbiol. 60:5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weems, J. J., Jr. 1992. Candida parapsilosis: epidemiology, pathogenicity, clinical manifestations, and antimicrobial susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:756-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson, R. B., D. Davis, B. M. Enloe, and A. P. Mitchell. 2000. A recyclable Candida albicans URA3 cassette for PCR product-directed gene disruptions. Yeast 16:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson, R. B., D. Davis, and A. P. Mitchell. 1999. Rapid hypothesis testing with Candida albicans through gene disruption with short homology regions. J. Bacteriol. 181:1868-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wirsching, S., S. Michel, and J. Morschhauser. 2000. Targeted gene disruption in Candida albicans wild-type strains: the role of the MDR1 gene in fluconazole resistance of clinical Candida albicans isolates. Mol. Microbiol. 36:856-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zemanova, J., J. Nosek, and L. Tomaska. 2004. High-efficiency transformation of the pathogenic yeast Candida parapsilosis. Curr. Genet. 45:183-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.