Abstract

The alternative transcription factor σB of Staphylococcus aureus affects the transcription of the cap gene cluster, required for the synthesis of capsular polysaccharide (CP), although this operon is lacking an apparent σB-dependent promoter. Regulation of cap expression and CP production in S. aureus strain Newman was shown here to be influenced by σB, the two-component signal transduction regulatory system ArlRS, and the yabJ-spoVG locus to different extents. Inactivation of arlR or deletion of the sigB operon strongly suppressed capA (CP synthesis enzyme A) transcription. Deletion of spoVG had a polar effect on yabJ-spoVG transcription and resulted in a two- to threefold decrease in capA transcription. Interestingly, immunofluorescence showed that CP production was strongly impaired in all three mutants, signaling that the yabJ-spoVG inactivation, despite its only partial effect on capA transcription, abolished capsule formation. trans-Complementation of the ΔspoVG mutant with yabJ-spoVG under the control of its native promoter restored CP-5 production and capA expression to levels seen in the wild type. Northern analyses revealed a strong impact of σB on arlRS and yabJ-spoVG transcription. We hypothesize that ArlR and products of the yabJ-spoVG locus may serve as effectors that modulate σB control over σB-dependent genes lacking an apparent σB promoter.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major nosocomial pathogen with the ability to cause a variety of diseases, including life-threatening infections. Like most microorganisms that are able to cause invasive diseases, S. aureus produces extracellular capsular polysaccharides (CPs), which are thought to be of importance in pathogenesis (reviewed in reference 35). Although 11 serologically distinct CPs were identified in S. aureus, the majority of clinical isolates produce CPs of serotype 5 (CP-5) or serotype 8 (CP-8). CPs protect S. aureus against opsonophagocytic killing by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (16, 17, 25, 53, 56) and enhance virulence in a number of animal models of staphylococcal infection (34, 40, 53, 54, 57). Expression of CPs is known to be influenced by various environmental signals in vitro and in vivo (reviewed in references 35 and 56), and transcription of the cap operon was shown to be modulated by regulatory elements, such as arlRS, agr, ccpA, mgr, sae, and sarA (7, 8, 23, 24, 26, 27, 39, 48, 52, 55). Recent microarray analyses added the alternative σ factor σB to the regulatory network controlling cap operon expression (3, 38) and indicated σB to control capA transcription in a growth phase-dependent manner (3). However, the lack of an apparent σB consensus sequence in the promoter of capA suggested that σB regulates cap transcription indirectly. Candidates for such downstream-acting regulators might be ArlRS and SarA, which are positively controlled by σB in S. aureus (2, 3), although SarA was previously shown to have only a minor effect on cap expression and CP production in S. aureus (24). RNAIII of the agr locus, known to positively affect capA expression (7, 24, 55), could be excluded as a positive mediator of σB activity on capA transcription, since RNAIII is known to be repressed by σB activity (2, 3, 15). Further candidates for regulators mediating the effect of σB might be the putative regulator homologs YabJ and SpoVG (SaCOL0540/1), whose expression is also predominantly controlled by σB in S. aureus (3). spoVG was the first developmentally regulated gene cloned from spore-forming Bacillus subtilis (47). Mutations in spoVG were shown to impair spore formation of B. subtilis stationary-phase cells at stage V (44) and to enhance the stage II defect of a spoIIB mutation (29), leading to the assumption that SpoVG is involved in the formation of the spore cortex. More recent findings indicated the primary function of SpoVG to be in the regulation of asymmetric septation in stationary-phase cells (31). Based on the finding that close homologues of SpoVG of B. subtilis are present in the genomes of several nonsporulating bacteria as well, we recently suggested that the SpoVG homologues might fulfill different, more general regulatory functions in the latter group of bacteria (3). YabJ is a member of the highly conserved YigF protein family, which is represented in animals, fungi, and bacteria. Many biological processes were shown to be influenced by YigF proteins, but its exact biochemical function remains unknown, although the crystal structure of YabJ of Bacillus subtilis has been published (51).

Here, we show that σB and the σB-modulated arlRS and yabJ-spoVG loci reduced capA transcription and strongly impaired capsule formation in the CP-5-producing strain Newman.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this investigation are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) with aeration (200 rpm) at 37°C. Where indicated, mutant strains were grown on antibiotic-supplemented media containing either 100 μg of ampicillin, 20 μg of chloramphenicol, 10 μg of erythromycin, or 10 μg of tetracycline per ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype and phenotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | NCTC8325-4 r− m+rsbU | 21 |

| COL | mec; high-Mcr clinical isolate; Mcr Tcr | 20 |

| Newman | Clinical isolate (ATCC 25904); CP-5 producer | 9 |

| BF21 | RN6390 arlR::cat; phenotypic arlRS mutant; Cmr | 10 |

| GP268 | NCTC8325 derivative; (rsbU-V-W-sigB)+-tet(L); Tcr | 12 |

| IK181 | NCTC8325 derivative; ΔrsbUVW-sigB::erm(B); Ermr | 22 |

| IK183 | COL ΔrsbUVW-sigB::erm(B); Ermr | 22 |

| IK184 | Newman ΔrsbUVW-sigB::erm(B); Ermr | 22 |

| SM1 | RN4220 ΔspoVG::erm(B); phenotypic yabJ-spoVG mutant, Ermr | This study |

| SM2 | Newman ΔspoVG::erm(B); phenotypic yabJ-spoVG mutant, Ermr | This study |

| SM99 | Newman arlR::cat; Cmr | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′ proAB laclqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tcr)] | Stratagene |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAC7 | Expression plasmid containing the PBAD promoter and the araC gene; Cmr | 42 |

| pAC7-sigB | pAC7 with a 0.75-kb PCR fragment of the sigB ORF from strain COL; Cmr | 14 |

| pBT | 1.6-kb PCR fragment of the tet(L) gene of pHY300PLK into Alw26I-digested pBC SK(+) (Stratagene); Tcr | 12 |

| pBus1 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle plasmid with multicloning site from pBluescript II SK (Stratagene) and the rrnT14 terminator sequence from pLL2443; Tcr | 45 |

| pEC1 | pUC derivative containing the 1.45-kb ClaI erm(B) fragment of Tn551; Apr Emr | 4 |

| pGC2 | E. coli-S. aureus shuttle plasmid; Cmr | Constructed and obtained by P. Matthews |

| pSA0455p | pSB40N with a 360-bp PCR fragment covering the σB-dependent promoter region preceding yabJ-spoVG fused to the reporter gene lacZα; Apr | 3 |

| pSB40N | Promoter probe plasmid; Apr | 19 |

| pSP-luc+ | Firefly luciferase cassette vector; Apr | Promega |

| pSTM01 | pEC1 with 0.5- and 1.1-kb PCR fragments covering the spoVG flanking regions; Emr Apr | This study |

| pSTM02 | pBT with a 3.1-kb KpnI/HindIII fragment of pSTM01 harboring the spoVG flanking regions and the erm(B) cassette fully replacing the spoVG coding region; Emr Tcr | This study |

| pSTM03 | pSP-luc+ with a 0.4-kb PCR fragment covering the capA promoter region fused to the reporter gene luc+; Apr Emr | This study |

| pSTM04 | pBus1 with a 2.1-kb KpnI/EcoRI fragment of pSTM03 harboring the capA promoter-luc+ fusion; Tcr | This study |

| pSTM05 | pGC2 with a 1-kb PCR fragment covering the σB-dependent yabJ promoter, yabJ, and spOVG; Cmr | This study |

| pSTM06 | pSB40N with a 0.8-kb PCR fragment covering the arlRS promoter fused to the reporter gene lacZα; Apr | This study |

| pSTM07 | pSB40N with a 0.4-kb PCR fragment covering the capA promoter region fused to the reporter gene lacZα; Apr | This study |

| pSTM11 | pBus1 with a 0.6-kb PCR fragment covering yabJ and the preceding σB-dependent promoter PyabJ; Tcr | This study |

| pSTM13 | pBus1 with a 0.5-kb PCR hybrid including the σB-dependent promoter PyabJ fused to the spoVG ORF; Tcr | This study |

Abbreviations are as follows: Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Emr, erythromycin resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant.

Strain construction.

For the construction of an S. aureus Newman ΔspoVG mutant, DNA fragments covering 0.5 kb of the region upstream of spoVG (up fragment) and 1.1-kb of the region downstream of spoVG (down fragment) were amplified by PCR, using primer pairs oSTM01/02 and oSTM03/04, respectively, and S. aureus Newman DNA as the template (Table 2). The resulting PCR products were KpnI/BamHI and PstI/HindIII digested, respectively, and cloned into plasmid pEC1 (4), with the up fragment preceding the erm(B) cassette and the down fragment following the resistance marker. The resulting plasmid, pSTM01, was digested with KpnI and HindIII and the insert cloned into the suicide vector pBT (12), yielding plasmid pSTM02, which was electroporated into RN4220 (Fig. 1). Mutants with the allelic replacement were selected for erythromycin resistance and screened for loss of tetracycline resistance, yielding strain SM1 [RN4220 spoVG::erm(B)], which was subsequently used as a donor for transducing the spoVG deletion into the CP-5-producing S. aureus strain Newman, yielding strain SM2. The spoVG deletion in SM2 was confirmed by PCR and Southern analyses.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Locationb or reference |

|---|---|---|

| arlRprobe+ | CAATGTGGACACAGAGTATG | 1465970-1465989 |

| arlRprobe− | CAGTTCGTGGCGTTGGG | 1465422-1465438 |

| arlSprobe+ | CAGCAGTATTAGAAGAATCG | 1464595-1464614 |

| arlSprobe− | GAGTCCATTACCGCCTTGAC | 1464154-1464173 |

| Asp23probe+ | ATGACTGTAGATAACAATAAAGC | 11 |

| Asp23probe− | TTGTAAACCTTGTCTTTCTTGG | 11 |

| capAp-F | cgcaagcttCAAACATCATATGATTATAAGC | 153034-153055 |

| capAp-R | gcgccatggTTTACCTCCCTTAAAAATT | 153384-153402 |

| oSTM01 | taggtaccTCAAAAGAAGTTAAACAAAG | 548665-548684 |

| oSTM02 | cggatccATATTAATCGAAAATTATAATTCC | 549175-549198 |

| oSTM03 | cgcctgcagATTATGATGATATGAAAATTATTG | 549706-549729 |

| oSTM04 | gcgaagcttGACCAATAACAACATCTTCGCC | 550760-550781 |

| oSTM20 | GAAAATCATTAACACAACAAG | 548806-548826 |

| oSTM21 | CTTAATTTTACTTACTAATTC | 549155-549175 |

| oSTM28 | cgatggatccGTGTTATGAATTTAATGAATGAG | 548603-548625 |

| oSTM29 | gcgtcgacTTATTGCAAATGTATTACATCGC | 549574-549596 |

| oSTM30 | CTAAATAAAACAGAGAGATATATACTATAGG | 549213-549243 |

| oSTM31 | gcgggtaccGTGTTATGAATTTAATGAATGAG | 548603-548625 |

| oSTM32 | gcgggatccGAAGCTTGATTAAACATATTAATCG | 549189-549213 |

| oSTM33 | gcgggatccTTATTGCAAATGTATTACATCGC | 549574-549596 |

| oSTM34 | ggattttcatatgACTAAAACTCCTTTTATGAAAAC | 548778-548800 |

| oSTM61 | cgcggatccCAAACATCATATGATTATAAGC | 153034-153055 |

| oSTM62 | gcgctcgagTTTACCTCCCTTAAAAATT | 153384-153402 |

| oSTM63 | cgcggatccGCAGTAAACCTAAAGTGTCG | 1466817-1466836 |

| oSTM64 | gcgctcgagTTGTACACCTCATATTACGAC | 1466067-1466087 |

| oSTM71 | gtgcatatgAAAGTGACAGATGTAAGACTTAG | 549259-549281 |

Lowercase letters represent nucleotide additions.

Based on the sequence of strain COL (RefSeq accession no. NC_002951).

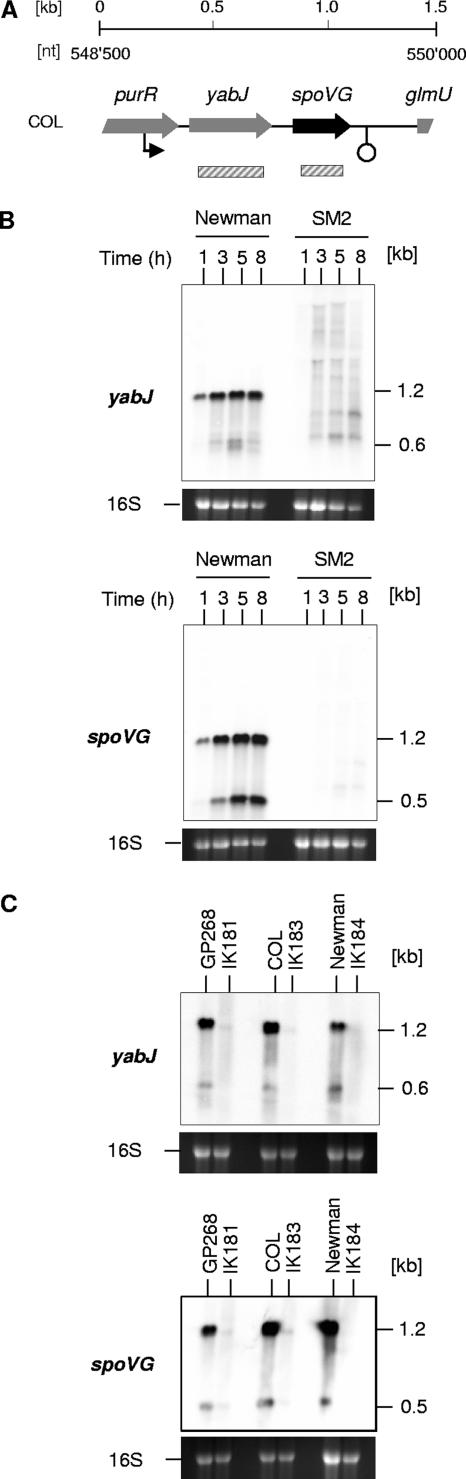

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the S. aureus yabJ-spoVG locus. Schematic representations of the yabJ-spoVG region of S. aureus and of the strategy used to obtain SM2 are shown. ORFs, promoters, terminators, and regions allowing recombination are indicated. ORF notations and nucleotide (nt) numbers correspond to those of the respective genomic regions of strain COL (RefSeq accession no. NC_002951).

The Newman arlR mutant SM99 was constructed by transducing the cat-tagged arlR mutation of BF21 (10) into Newman and selecting for chloramphenicol resistance.

Plasmid construction.

For the construction of the capA promoter-luc+ reporter gene fusion plasmid pSTM04, a 0.4-kb DNA fragment covering the capA promoter region was amplified by PCR using primer pair capAp-F/capAp-R and S. aureus Newman DNA as the template (Table 2). The resulting PCR product was HindIII/NcoI digested and cloned into pSP-luc+ (Promega) as a 5′ fusion to the reporter gene luc+. A plasmid (pSTM03) harboring the promoter fragment was used to excise the promoter-reporter gene fragment by digestion with HindIII/XhoI, which was subsequently cloned into the multiple cloning site of the Escherichia coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pBus1 (45) to obtain plasmid pSTM04. pSTM04 was finally used for electroporation of RN4220, from which it was transduced into strains Newman, SM2, SM99, and IK184 by phage transduction.

For the construction of pSTM05, a 995-bp DNA fragment covering the σB-dependent yabJ promoter, yabJ, and spoVG was amplified by PCR using primer pair oSTM28/oSTM29 and S. aureus Newman DNA as the template. The resulting PCR product was BamHI/SalI digested and cloned into the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pGC2 (P. Matthews). pSTM05 was electroporated into RN4220, from which it was transduced into strains Newman and SM2.

For the construction of pSTM06 and pSTM07, DNA fragments representing 771 bp and 370 bp of the arlR and capA promoter regions of Newman, respectively, were generated by PCR using primer pairs oSTM63/oSTM64 and oSTM61/oSTM62. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and XhoI and cloned into promoter probe plasmid pSB40N (42) upstream of the lacZα reporter gene to obtain pSTM06 (arlRp) and pSTM07 (capAp).

For the construction of pSTM11, a 612-bp DNA fragment covering the σB-dependent yabJ promoter (PyabJ) and yabJ was amplified by PCR using primer pair oSTM31/oSTM32 and S. aureus Newman DNA as the template. The resulting PCR product was BamHI/KpnI digested and cloned into the E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector pBus1. For pSTM13 (PyabJ-spoVG), harboring promoter PyabJ fused to spoVG, primer pairs oSTM31/oSTM34 and oSTM71/oSTM33 were used together with pSTM05 to amplify 199- and 339-bp DNA fragments covering the σB-dependent promoter including the region preceding the yabJ open reading frame (ORF) and spoVG, respectively. The resulting PCR products were KpnI/NdeI and NdeI/BamHI digested and cloned into pBus1. pSTM11 and pSTM13 were electroporated into RN4220 and subsequently transduced into strains Newman and SM2.

Sequence analyses confirmed the identities of all cloned inserts.

Protease activity assay.

The proteolytic activities of Newman, IK184, SM2, and SM99 were determined on casein agar plates as clear zones surrounding colonies.

Northern analyses.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus were diluted 1:100 into fresh prewarmed LB medium and grown at 37°C and 200 rpm. Samples were removed from the culture at the time points indicated and centrifuged at 14,000 × g and 4°C for 1 min, the culture supernatants were discarded, and the cell sediments were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNAs were isolated according to Cheung et al. (6). Blotting, hybridization, and labeling were performed as previously described (12). Primer pairs arlRprobe+/arlRprobe−, arlSprobe+/arlSprobe−, asp23probe+/asp23probe−, oSTM20/oSTM21, and oSTM29/oSTM30 were used to generate digoxigenin-labeled arlR-, arlS-, asp23-, yabJ-, and spoVG-specific probes by PCR labeling.

Luciferase assays.

Luciferase activity was measured as described earlier (2), using the luciferase assay substrate and a Turner Designs TD-20/20 luminometer (Promega).

LightCycler RT-PCR.

The capA and gyrB transcripts were quantified by LightCycler reverse transcription (RT)-PCR as described earlier (48), using RNA samples obtained from cultures grown for 8 and 24 h in LB at 37°C and 200 rpm.

CP-5 determination.

CP-5 production was determined by indirect immunofluorescence from cultures grown for 8 and 24 h in LB medium as described earlier (48), using mouse immunoglobulin M monoclonal antibodies to CP-5 (13). Quantification of CP-5-positive cells was done by determining the numbers of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole)- and CY-3-positive cells using the program CellC 1.11 (Institute of Signal Processing, Tampere University of Technology, Finland).

Two-plasmid analysis.

Testing of the interaction of S. aureus promoters with RNA polymerase containing S. aureus σB was done essentially as described earlier (14). The promoter-containing plasmids pSA0455p (yabJ promoter), pSTM06 (arlR promoter), and pSTM07 (capA promoter) were transformed into E. coli XL1Blue containing a compatible plasmid, either pAC7-sigB or empty pAC7. Clones were selected on LBACX-ARA plates (LB medium containing lactose [5 mg ml−1], ampicillin [100 μg ml−1], chloramphenicol [40 μg ml−1], 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-d-galactopyranoside [20 μg ml−1], and arabinose [2 μg ml−1]) and analyzed for color production (43).

RESULTS

Construction of SM2 and SM99.

Inactivation of spoVG and arlR in S. aureus Newman yielded strains SM2 and SM99, respectively. Southern blots probed with spoVG or the C-terminal part of arlR confirmed the constructs (data not shown).

Transcriptional analysis of the yabJ-spoVG locus in Newman and SM2.

Our recent microarray analyses suggested that yabJ and spoVG form a bicistronic operon that is predominantly controlled by σB activity (3). To test whether and how the deletion of spoVG affected the expression of the yabJ-spoVG locus, we analyzed the transcription of yabJ and spoVG in cells of Newman and SM2 during growth in LB. Our Northern analyses identified yabJ-specific signals with sizes of 1.2 and 0.6 kb and spoVG-specific signals with sizes of 1.2 and 0.5 kb in Newman. The 1.2-kb signal detected with both the yabJ- and the spoVG-specific probes appeared to be the major transcript of the yabJ-spoVG locus. It was present already after 1 h of growth and increased within time, while the minor 0.6-kb, yabJ-specific signal and the 0.5-kb, spoVG-specific signal appeared only after 3 h of growth (Fig. 2). In line with our Southern results, no spoVG-specific transcripts were detected in SM2. Based on our hypothesis that yabJ and spoVG are predominantly transcribed as a bicistronic mRNA and taking into account that the deletion of spoVG did not alter the genetic organization of yabJ and its promoter(s) in SM2, we expected the allelic replacement of spoVG with ermB to affect the sizes of the yabJ transcripts rather than the intensities of yabJ transcription. Surprisingly, we detected only a series of faint signals in our yabJ Northern analysis of SM2, indicating that the deletion of spoVG apparently had a polar effect on the expression of the preceding yabJ. We therefore considered SM2 to represent a phenotypic yabJ-spoVG mutant.

FIG. 2.

Expression of yabJ-spoVG in S. aureus. (A) Schematic representation of the yabJ-spoVG region of S. aureus COL. ORFs, promoters, terminators, and the probes used are indicated. nt, nucleotide. (B) Northern blot analyses of the yabJ and spoVG transcriptions in Newman and SM2 (ΔspoVG) during growth in LB. (C) Effect of σB on yabJ and spoVG expression. Northern blot analyses of the yabJ and spoVG transcriptions in strains GP268, COL, and Newman and their isogenic ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutants after 8 h of growth. Relevant transcript sizes are indicated. Ethidium bromide-stained 16S rRNA patterns are shown as an indication of RNA loading.

Phenotypic characterization of SM2 and SM99.

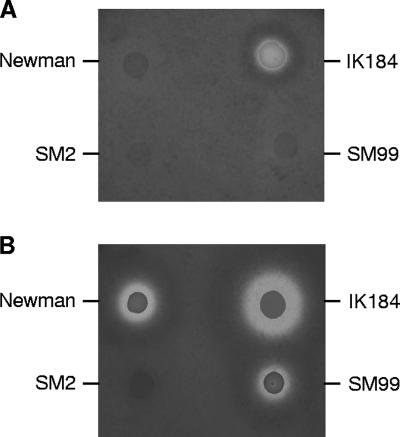

The successful allelic replacement of spoVG and its impact on yabJ indicated that these genes, like sigB and arlR, were not essential for growth in vitro. Deletions of sigB and arlR were previously shown to affect the growth rates of the mutants (12, 23). While inactivation of arlR reduces growth during the early stages (23), inactivation of sigB affects only the later stages of growth (12). Monitoring growth of strains Newman, SM2, and SM99 in LB over a period of 8 h confirmed the negative impact of the arlR mutation on the growth rate of SM99, while the growth curves of Newman and SM2 were virtually identical, indicating that deletion of spoVG was not associated with the growth defect observed for sigB mutants (data not shown). Inactivation of sigB is further known to prevent formation of staphyloxanthin (12, 22, 33), the orange end product of S. aureus carotenoid biosynthesis (30). Neither inactivation of arlR nor deletion of spoVG reduced pigment formation, indicating that ArlR and YabJ/SpoVG were not involved in the regulation of pigment production of S. aureus (data not shown). Mutations in sigB and arlRS are also known to affect the proteolytic activities of the mutants (10, 18, 23). We therefore tested the proteolytic activities of Newman and its derivatives IK184 (ΔrsbUVW-sigB), SM2 (ΔspoVG), and SM99 (arlR) on casein agar plates. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C, only IK184 produced a clear zone surrounding the colony, while neither Newman, SM2, nor SM99 exhibited such a clear zone (Fig. 3A). However, after storage of the incubated plates for 72 h at room temperature, clear zones surrounding colonies were also observed for Newman and SM99 but not for SM2 (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the inactivation of the yabJ-spoVG locus caused a suppression of extracellular protease production or activation in S. aureus.

FIG. 3.

Protease production of Newman, IK184 (ΔrsbUVW-sigB), SM2 (ΔspoVG), and SM99 (arlR) grown on casein agar plates for 24 h at 37°C (A) and then incubated for 72 h at room temperature (B).

Effect of σB on arlRS and yabJ-spoVG expression.

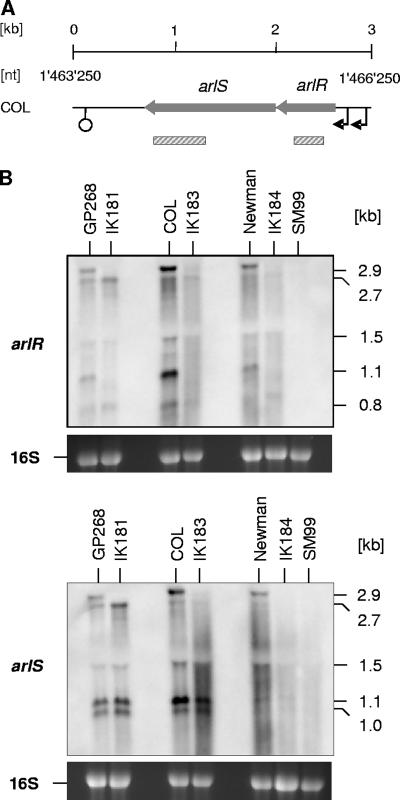

We recently observed that arlRS transcription, like yabJ-spoVG transcription, is positively controlled by σB activity during later growth stages (3). While the positive effect of σB on yabJ-spoVG transcription was found in different S. aureus genetic lineages, including COL, GP268 (rsbU-positive NCTC8325 derivative), and Newman (3, 38), the positive impact of σB on arlRS expression seemed to be strain dependent and was seen only in S. aureus Newman so far (3). We therefore determined the arlRS and yabJ-spoVG expression patterns in cells of COL, GP268, Newman, and their isogenic ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutants grown in LB for 8 h. While clear yabJ- and spoVG-specific signals were visible in COL, GP268, and Newman at this growth stage, these transcripts were missing in all of the ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutants (Fig. 2C), confirming the importance of σB activity for the expression of the yabJ-spoVG locus. Interestingly, our Northern analyses of arlRS transcription revealed a clear σB dependence in all genetic lineages analyzed (Fig. 4) and identified several new signals in a strain-dependent manner in addition to the 2.7- and 1.5-kb transcripts that have been reported for arlRS before (10). Hybridizing the total RNA samples with a probe specific for arlR produced signals with sizes of 2.9, 2.7, 1.5, 1.1, and 0.9 kb in all parental strains, while the 2.9- and 1.1-kb signals were missing in all ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutants. All signals were missing in the arlR mutant SM99, confirming that the signals were arlR specific. Hybridizing the same RNAs with a probe specific for arlS resulted in signals with sizes of 2.9, 2.7, and 1.5 kb in all parental strains, while clear 1.1- and 1.0-kb signals were present only in COL and GP268. As for the arlR pattern, the 2.9-kb signal was detectable only in the wild-type strains and missing in the ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutants. However, the 1.1- and 1.0-kb signals were present in the COL and GP268 ΔrsbUVW-sigB derivatives as well, indicating that these transcripts are produced independently from σB activity and suggesting that the 1.1-kb signals observed with arlR and arlS were not identical. Only weak signals were identified with arlS in the Newman rsbUVW-sigB mutant IK184, and none of the signals were detected in SM99. The impact of σB on arlRS expression appeared to be strongest in Newman but was also visible in the COL and GP268 backgrounds.

FIG. 4.

Effect of σB on arlRS expression. (A) Schematic representation of the arlRS region of S. aureus COL. ORFs, promoters, terminators, and the regions used as probes are indicated. ORF notations and nucleotide (nt) numbers correspond to those of the respective genomic regions of strain COL (RefSeq accession no. NC_002951). (B) Northern blot analyses of the arlR and arlS transcriptions in strains GP268, COL, and Newman and their isogenic ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutants after 8 h of growth in LB at 37°C. Relevant transcript sizes and the probes used are indicated. Ethidium bromide-stained 16S rRNA patterns are shown as an indication of RNA loading.

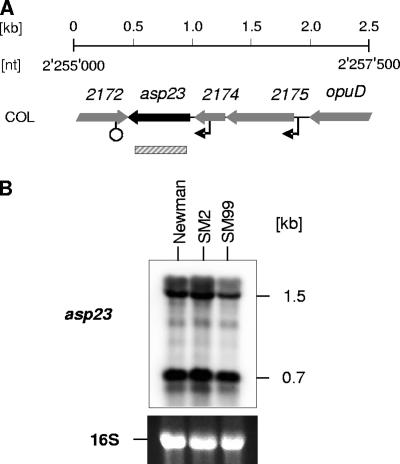

Effect of ArlRS and YabJ/SpoVG on σB activity.

To assess whether ArlRS and YabJ/SpoVG might have an impact on σB activity, we analyzed the transcription of asp23, a marker gene for σB activity in S. aureus (11, 12, 22), during a later growth stage in Newman, SM2, and SM99 (Fig. 5). No difference in asp23 expression was found between the wild type and its ΔspoVG derivative, while the arlR mutant showed a slight but reproducible reduction in the expression of the 1.5-kb transcript but not of the 0.7-kb transcript. Interestingly, variations in the expression levels of these two directly σB-controlled transcripts were recently observed in a Newman hemB mutant, indicating the presence of factors modulating σB activity in the recognition of its promoter consensus sequences under certain circumstances (49).

FIG. 5.

Effect of arlRS and yabJ-spoVG on σB activity. (A) Schematic representation of the asp23 region. ORFs, promoters, terminators, and the regions used as probes are indicated. ORF notations and nucleotide (nt) numbers correspond to those of the respective genomic regions of strain COL (RefSeq accession no. NC_002951). (B) Northern blot analysis of σB-dependent asp23 transcription in Newman, SM2 (ΔspoVG), and SM99 (arlR) grown for 8 h in LB at 37°C. Relevant transcript sizes are indicated. Ethidium bromide-stained 16S rRNA patterns are shown as an indication of RNA loading.

Effect of the arlRS locus on yabJ-spoVG transcription and vice versa.

The inactivation of arlR did not affect yabJ-spoVG transcription, nor did the deletion of spoVG alter arlRS expression, suggesting that both loci are independent from each other (data not shown).

Effect of σB, ArlRS, and the yabJ-spoVG locus on capA transcription.

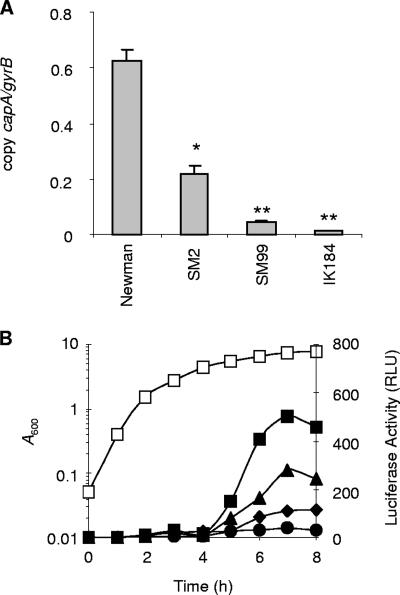

Previous studies showed that transcription of the cap operon is growth phase dependent and affected by various global regulators in S. aureus. Expression of the cap operon is predominantly driven by the major promoter located at the beginning of the operon, although several internal promoters with weak activities have been identified in some cap gene clusters (36, 37, 46). To confirm the previously observed impact of σB and ArlRS on cap expression (3, 27, 28, 38) and to see whether the yabJ-spoVG locus is involved in cap operon regulation, we determined the capA expression levels in strains Newman, IK184, SM2, and SM99 by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 6A). Monitoring capA expression after 8 h of growth showed that all three mutations significantly reduced capA transcription in S. aureus. While inactivation of rsbUVW-sigB and arlR was associated with a strong reduction in capA expression (approximately 47-fold for rsbUVW-sigB and 15-fold for arlR; P < 0.01), deletion of spoVG resulted in a 2- to 3-fold reduction in capA transcription (P < 0.05), compared with the wild-type level. After 24 h of growth, capA transcript levels were drastically reduced and detectable only in Newman, SM2, and SM99, resulting in very low capA-to-gyrB transcript ratios (0.09 ± 0.03 copies of capA per copy of gyrB in Newman, 0.09 ± 0.01 copies in SM2, and 0.004 ± 0.0002 copies in SM99), while the capA transcription levels in IK184 were found to be below the detection limit.

FIG. 6.

Expression of capA in Newman and its derivatives. (A) Quantitative transcript analysis of capA by LightCycler RT-PCR of strains Newman, SM2 (ΔspoVG), SM99 (arlR), and IK184 (ΔrsbUVW-sigB) grown for 8 h at 37°C in LB. Transcripts were quantified in reference to the transcription of gyrase (in numbers of copies per copy of gyrB). Values from two separate RNA isolations and two independent RT-PCRs each were used to calculate the mean expression levels (± standard errors of the mean). *, P < 0.05 for derivative versus Newman; **, P < 0.01 for derivative versus Newman. (B) Growth curve of Newman (open squares) and transcriptional activity of the capA promoter in plasmid pSTM04-carrying strains Newman (squares), SM2 (triangles), SM99 (diamonds), and IK184 (circles). capA promoter activity was determined by measuring the luciferase activity of the capAp-luc+ fusion. Shown are representative results for at least three independent experiments.

The expression of the capA promoter during growth was monitored with the capA promoter-luc+ reporter gene fusion plasmid pSTM04 by measuring luciferase activity (Fig. 6B). In line with previous findings (3, 27), luciferase activity values increased in the parental strain Newman in a growth phase-dependent manner, starting at the transition from late-exponential growth phase to stationary phase (i.e., at 4 h), reaching its maximum after 7 h of growth, and declining thereafter. The course of luciferase activity in the ΔspoVG mutant SM2 followed in principle that in its parental strain, Newman, although the luciferase activity in SM2 was roughly half as strong as that in Newman at most of the time points monitored. In agreement with the real-time RT-PCR results, only a low level of luciferase activity was detectable in the ΔrsbUVW-sigB derivative IK184 at all time points analyzed. A clear reduction in luciferase activity was also found for SM99, albeit not as strong as expected from the real-time RT-PCR results.

CP-5 production in Newman, IK184, SM2, and SM99.

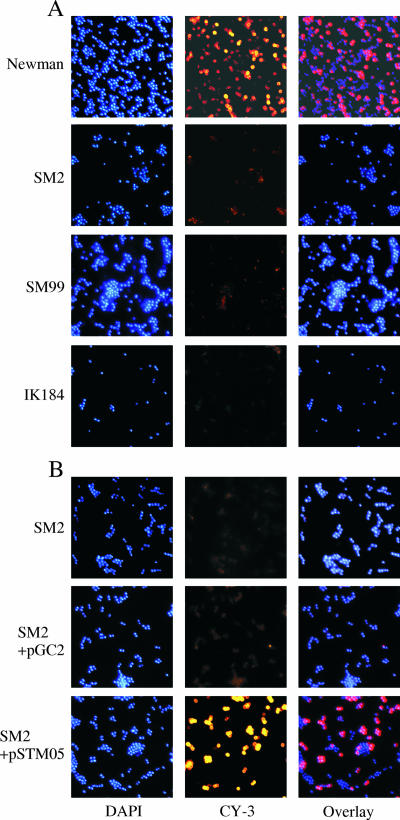

To see whether and how the alterations in capA expression observed in IK184, SM2, and SM99 had an impact on capsule production, we investigated the capsule formations of Newman and its derivatives after growth in LB for 8 and 24 h by indirect immunofluorescence (Fig. 7, only 8-h data shown). While more than half of the Newman cells (57%) incubated with the CP-5 antibodies produced clear fluorescence signals at both time points analyzed, indicating the presence of CPs in these wild-type cells after 8 and 24 h of growth, this was not the case with either SM2, SM99, or IK184. Only 1% of the ΔspoVG cells, 2% of the arlR-defective cells, and 1% of the ΔrsbUVW-sigB cells emitted detectable amounts of fluorescence under these conditions, suggesting that all three mutants were strongly impaired in their abilities to produce CPs.

FIG. 7.

Capsule production in Newman and its derivatives grown for 8 h in LB at 37°C. (A) CP-5 expression determined by indirect immunofluorescence of strain Newman and its derivatives SM2 (ΔspoVG), SM99 (arlR), and IK184 (ΔrsbUVW-sigB). (B) trans-Complementation of ΔspoVG mutant SM2. CP-5 expression was determined by indirect immunofluorescence of SM2, and SM2 transformed with either pSTM05 (PyabJ-yabJ-spoVG) or the empty control plasmid pGC2. Bacteria were stained with DAPI, marked with CP-5-specific monoclonal antibodies, and stained with Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (CY-3).

trans-Complementation of SM2.

In order to evaluate whether the decrease in capA transcription in SM2 and its impact on CP-5 formation were due to the inactivation of yabJ-spoVG, we constructed plasmid pSTM05, carrying the yabJ-spoVG operon, and assessed its impact on capA transcription and CP-5 production in the trans-complemented mutant. Introduction of pSTM05 into SM2 restored the ability of the trans-complemented mutant to produce a capsule (Fig. 7B). While 52% of the SM2 cells harboring plasmid pSTM05 were CY-3 positive after 8 h of growth, only 3% of the SM2 cells transformed with the empty control plasmid pGC2 produced detectable amounts of fluorescence. Similarly, introduction of pSTM05 yielded values for capA promoter-driven luciferase activity after 8 h of growth that were comparable to those for the wild type (475 ± 31 relative light units [RLU] for Newman and 510 ± 42 RLU for SM2 harboring pSTM05), while introduction of pGC2 into SM2 had no effect on capAp-dependent luciferase activity (246 ± 30 RLU for SM2 and 208 ± 25 RLU for SM2 harboring pGC2). trans-Complementation assays performed with SM2 transformed with plasmids harboring either yabJ under the control of its σB-dependent promoter (pSTM11) or a PyabJ-spoVG fusion (pSTM13), on the other hand, failed to revert the effect of the spoVG deletion on capsule formation, signaling that both yabJ and spoVG are required to complement SM2 (data not shown).

Two-plasmid testing.

The lack of apparent σB-specific consensus sequences in the arlRS and capA promoters suggests the transcription of these operons to be indirectly controlled by σB activity. To support this hypothesis, we cloned the promoters of arlRS and capA into reporter plasmid pSB40N and tested the resulting plasmids pSTM06 (arlRSp) and pSTM07 (capAp), respectively, in a heterologous two-plasmid system that was recently shown to be suitable for the identification of σB-dependent S. aureus promoters (14). Plasmid pSA0455p, harboring the σB-dependent promoter upstream of yabJ-spoVG (3), which was used as a positive control, and plasmids pSTM06 and pSTM07, harboring the arlRS or capA promoter, were each transformed into E. coli XL1Blue cells containing either pAC7 or pAC7-sigB (14), respectively, and the clones obtained were selected on LBACX-ARA plates (43). Transformants containing pAC7 produced uncolored colonies, indicating that none of the introduced promoters were recognized by any form of E. coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Transformants containing pAC7-sigB and pSA0455p were blue on selective LBACX-ARA plates, demonstrating that the activity of the yabJ-spoVG promoter was dependent upon arabinose-induced heterologous expression of the S. aureus sigB gene in E. coli and indicating that the S. aureus σB-E. coli RNA polymerase holoenzyme hybrid was capable of recognizing the heterologous S. aureus yabJ-spoVG promoter. In contrast, transformants containing either pAC7-sigB and pSTM06 (arlRSp) or pAC7-sigB and pSTM07 (capAp) remained uncolored on selective LBACX-ARA plates, demonstrating that neither the arlRS nor the capA promoter region was directly recognized by the σB-containing RNA polymerase holoenzyme.

Attempts to clone spoVG under the control of an inducible promoter.

To support our hypothesis that SpoVG might act as regulator downstream of σB, we tried to construct a plasmid harboring spoVG under the control of an inducible promoter but were not successful with either E. coli or S. aureus. All our attempts to clone spoVG downstream of a σB-independent promoter resulted in mutations in the promoter, in the ribosomal binding site, or in the ORF of spoVG, signaling that spoVG expression needs to be tightly controlled by σB or a factor that is dependent on σB (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

A recent transcriptional profiling of the σB regulon in S. aureus indicated the alternative transcription factor to affect the expression levels of 251 genes or operons (3). While most of the genes/operons identified as upregulated by σB in that study were also preceded by nucleotide sequences resembling the S. aureus σB promoter consensus sequence (14), still a significant number of genes/operons found to be upregulated by σB lacked such a nucleotide sequence in their promoter regions, including arlRS and the cap operon (3). Although it is still possible that the latter group of genes/operons might be transcribed by the direct action of a σB-containing RNA polymerase holoenzyme, it is more conceivable that σB controls the expression of a regulator(s), which would subsequently promote the expressions of these genes/operons. Our Northern analysis performed here confirmed the positive impact of σB on arlRS and capA expression. However, unlike what was suggested by the microarray analyses, the Northern analyses performed here demonstrated arlRS expression to be affected by σB activity not only in S. aureus Newman but in strains COL and GP268 as well. While arlRS transcription was found to be highly dependent on σB activity in Newman during the later growth stage (8 h of growth), its effect appeared to be less pronounced in COL and the NCTC8325 derivative GP268. Interestingly, our Northern analysis of the arlRS locus identified several further transcripts in addition to the 2.7- and 1.5-kb transcripts that were observed in the NCTC8325 derivative RN6390 (10), suggesting that the arlRS locus underlies a complex and strain-dependent regulatory circuit. Regulation of arlRS by σB is likely to be indirect, since the nucleotide sequence preceding arlR was not recognized by a two-plasmid system for the identification of promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing S. aureus σB (14), leaving open the question of how σB affects arlRS expression.

Expression of the cap operon and capsule formation in S. aureus are known to be under multiple levels of control and affected by various environmental stimuli. In line with previous findings indicating σB to take part in the control of cap operon expression (3, 38), our quantitative RT-PCR results presented here confirmed σB to be important for cap operon transcription in S. aureus, since capA expression was drastically reduced in the ΔrsbUVW-sigB mutant IK184. Likewise, the capA promoter-driven luciferase activity in IK184 remained at a constantly low level throughout growth, in contrast to that in the wild type, where the luciferase activity increased with time, yielding a 20- to 30-fold difference between Newman and IK184 after 8 h of growth. As could be expected from the strong impact of σB on cap operon transcription, we could show that σB is also essential for capsule formation, since IK184, unlike its parental strain, was drastically impaired in its ability to produce CP-5 after 8 and 24 h of growth. Since the two-plasmid testing of the capA promoter sequence failed to identify a direct interaction between capAp and the σB-containing RNA polymerase, its effect on cap operon expression is likely to be indirect and mediated via a downstream-acting regulator(s) that is itself controlled by σB activity. One such regulator might be ArlR of the ArlRS system, which we confirmed here to be influenced by σB activity in S. aureus, and which is known to affect cap operon transcription and capsule formation (28). However, since our quantitative RT-PCR results for capA in arlR mutant SM99 yielded a 15-fold reduction in capA transcription in comparison with the wild-type level, and since the capA promoter-driven luciferase activity in SM99 was only 4- to 5-fold reduced after 8 h of growth, an additional regulator(s) that mediates the effect of σB on cap operon expression has to be proposed. To test whether the σB-dependent SpoVG homolog of S. aureus might fulfill such a function, we constructed strain SM2 lacking spoVG. We found that the deletion of spoVG in S. aureus Newman yielded a strong polar effect on yabJ transcription, suggesting the ΔspoVG mutant SM2 to represent a phenotypic yabJ-spoVG double mutant. We found that deletion of spoVG decreased capA transcription two- to threefold. Interestingly, deletion of spoVG strongly repressed the capacity of the mutant to produce CP-5, although SM2 was found to still produce significant amounts of capA transcripts. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between capA transcription and capsule production observed in SM2 might be an additional influence of YabJ/SpoVG on the expression of internal promoters of the cap operon. Alternatively, the yabJ-spoVG locus might affect CP production on transcriptional and posttranslational levels, as has been shown for SarA (24). Interestingly, since inactivation of sarA is known to increase extracellular protease activity (5) and capsule stability (24), it might be that the negative effect of the spoVG deletion on the extracellular protease activity contributed to the CP-negative phenotype in SM2.

Our data clearly suggest the effector molecules of the yabJ-spoVG locus to contribute to the network of regulatory molecules that control cap operon transcription and CP-5 formation in S. aureus Newman, albeit on a lower level than ArlRS and σB. Moreover, the observation that the deletion of spoVG influenced extracellular protease production and capA transcription and suppressed CP-5 formation indicates that YabJ and/or SpoVG might indeed function as a regulatory molecule in S. aureus. This hypothesis is further supported by our findings that deletion of spoVG in methicillin-resistant S. aureus and in glycopeptide intermediate-resistant S. aureus strains significantly reduced the resistance levels against β-lactams and glycopeptides, respectively (S. Meier and M. Bischoff, unpublished results), two phenomena that have also been associated with σB activity (1, 32, 41, 50, 58). Considering the impact of spoVG deletion on capsule production and on resistance formation in methicillin-resistant S. aureus and glycopeptide intermediate-resistant S. aureus, and in the face of our recent findings demonstrating yabJ-spoVG expression to be highly dependent on σB activity (3), we propose the effector molecules of the yabJ-spoVG locus of S. aureus to act as regulatory molecules that mediate, together with ArlRS, the effect of σB on capsule formation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Bonizzi-Theler Foundation, Swiss National Science Foundation grant 3100A0-100234, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Wo 578/5-1), and European Community grant EU-LSH-CT2003-50335 (BBW 03.0098). J.K. is supported by grant 2/6010/26 from the Slovak Academy of Sciences.

We thank Jean-Michel Fournier for the monoclonal anticapsular antibody and Benedicte Fournier for strain BF21.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bischoff, M., and B. Berger-Bächi. 2001. Teicoplanin stress-selected mutations increasing σB activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bischoff, M., J. M. Entenza, and P. Giachino. 2001. Influence of a functional sigB operon on the global regulators sar and agr in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:5171-5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff, M., P. Dunman, J. Kormanec, D. Macapagal, E. Murphy, W. Mounts, B. Berger-Bächi, and S. Projan. 2004. Microarray-based analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus σB regulon. J. Bacteriol. 186:4085-4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brückner, R. 1997. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, P. F., and S. J. Foster. 1998. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 180:6232-6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung, A. L., K. J. Eberhardt, and V. A. Fischetti. 1994. A method to isolate RNA from gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. Anal. Biochem. 222:511-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocchiaro, J. L., M. I. Gomez, A. Risley, R. Solinga, D. O. Sordelli, and J. C. Lee. 2006. Molecular characterization of the capsule locus from non-typeable Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 59:948-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dassy, B., T. Hogan, T. J. Foster, and J. M. Fournier. 1993. Involvement of the accessory gene regulator (agr) in expression of type-5 capsular polysaccharide by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:1301-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duthie, E. S., and L. L. Lorenz. 1952. Staphylococcal coagulase: mode of action and antigenicity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 6:95-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier, B., A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 2001. The two-component system ArlS-ArlR is a regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 41:247-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gertz, S., S. Engelmann, R. Schmid, K. Ohlsen, J. Hacker, and M. Hecker. 1999. Regulation of sigmaB-dependent transcription of sigB and asp23 in two different Staphylococcus aureus strains. Mol. Gen. Genet. 261:558-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giachino, P., S. Engelmann, and M. Bischoff. 2001. σB activity depends on RsbU in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 183:1843-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoeger, P. H., W. Lenz, A. Boutonnier, and J. M. Fournier. 1992. Staphylococcal skin colonization in children with atopic dermatitis: prevalence, persistence, and transmission of toxigenic and nontoxigenic strains. J. Infect. Dis. 165:1064-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Homerova, D., M. Bischoff, A. Dumoulin, and J. Kormanec. 2004. Optimization of a two-plasmid system for the identification of promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing Staphylococcus aureus alternative sigma factor Sigma B. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 232:173-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horsburgh, M. J., J. L. Aish, I. L. White, L. Shaw, J. K. Lithgow, and S. J. Foster. 2002. σB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J. Bacteriol. 184:5457-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kampen, A. H., T. Tollersrud, and A. Lund. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharide types 5 and 8 reduce killing by bovine neutrophils in vitro. Infect. Immun. 73:1578-1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karakawa, W. W., A. Sutton, R. Schneerson, A. Karpas, and W. F. Vann. 1988. Capsular antibodies induce type-specific phagocytosis of capsulated Staphylococcus aureus by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 56:1090-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson, A., and S. Arvidson. 2002. Variation in extracellular protease production among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus due to different levels of expression of the protease repressor sarA. Infect. Immun. 70:4239-4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kormanec, J., and B. Sevcikova. 2000. Identification and transcriptional analysis of a cold shock-inducible gene, cspA, in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Mol. Gen. Genet. 264:251-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblum, J., B. J. Hartmann, R. P. Novick, and A. Tomasz. 1986. Conversion of a homogeneously methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus to heterogeneous resistance by Tn551-mediated insertional inactivation. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 5:714-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreiswirth, B. N., S. Löfdahl, M. J. Betley, M. O'Reilly, P. M. Schlievert, M. S. Bergdoll, and R. P. Novick. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kullik, I., P. Giachino, and T. Fuchs. 1998. Deletion of the alternative sigma factor σB in Staphylococcus aureus reveals its function as a global regulator of virulence genes. J. Bacteriol. 180:4814-4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang, X., L. Zheng, C. Landwehr, D. Lunsford, D. Holmes, and Y. Ji. 2005. Global regulation of gene expression by ArlRS, a two-component signal transduction regulatory system of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187:5486-5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luong, T., S. Sau, M. Gomez, J. C. Lee, and C. Y. Lee. 2002. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharide expression by agr and sarA. Infect. Immun. 70:444-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luong, T. T., and C. Y. Lee. 2002. Overproduction of type 8 capsular polysaccharide augments Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:3389-3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luong, T. T., S. W. Newell, and C. Y. Lee. 2003. mgr, a novel global regulator in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 185:3703-3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luong, T. Y., P. M. Dunman, E. Murphy, S. J. Projan, and C. Y. Lee. 2006. Transcriptional profiling of the mgrA regulon in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 188:1899-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luong, T. T., and C. Y. Lee. 2006. The arl locus positively regulates Staphylococcus aureus type 5 capsule via an mgrA-dependent pathway. Microbiology 152:3123-3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolis, P. S., A. Driks, and R. Losick. 1993. Sporulation gene spoIIB from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 175:528-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall, J. H., and G. J. Wilmoth. 1981. Pigments of Staphylococcus aureus, a series of triterpenoid carotenoids. J. Bacteriol. 147:900-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuno, K., and A. L. Sonenshein. 1999. Role of SpoVG in asymmetric septation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:3392-3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morikawa, K., A. Maruyama, Y. Inose, M. Higashide, H. Hayashi, and T. Ohta. 2001. Overexpression of sigma factor, σB, urges Staphylococcus aureus to thicken the cell wall and to resist β-lactams. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 288:385-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholas, R. O., T. Li, D. McDevitt, A. Marra, S. Sucoloski, P. L. Demarsh, and D. R. Gentry. 1999. Isolation and characterization of a sigB deletion mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 67:3667-3669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nilsson, I.-M., J. C. Lee, T. Bremell, C. Ryden, and A. Tarkowski. 1997. The role of staphylococcal polysaccharide microcapsule expression in septicemia and septic arthritis. Infect. Immun. 65:4216-4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Riordan, K., and J. C. Lee. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:218-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ouyang, S., and C. Y. Lee. 1997. Transcriptional analysis of type 1 capsule genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 23:473-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ouyang, S., S. Sau, and C. Y. Lee. 1999. Promoter analysis of the cap8 operon, involved in type 8 capsular polysaccharide production in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 181:2492-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pane-Farre, J., B. Jonas, K. Forstner, S. Engelmann, and M. Hecker. 2006. The σB regulon in Staphylococcus aureus and its regulation. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:237-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pöhlmann-Dietze, P., M. Ulrich, K. B. Kiser, G. Doring, J. C. Lee, J. M. Fournier, K. Botzenhart, and C. Wolz. 2000. Adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to endothelial cells: influence of the capsular polysaccharide, the global regulator agr, and the bacterial growth phase. Infect. Immun. 68:4865-4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Portolés, M., K. B. Kiser, N. Bhasin, K. H. N. Chan, and J. C. Lee. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus Cap5O has UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase activity and is essential for capsule expression. Infect. Immun. 69:917-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price, C. T., V. K. Singh, R. K. Jayaswal, B. J. Wilkinson, and J. E. Gustafson. 2002. Pine oil cleaner-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and oxacillin and involvement of SigB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5417-5421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rezuchova, B., and J. Kormanec. 2001. A two-plasmid system for identification of promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing extracytoplasmic stress response sigma(E) in Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. Methods 45:103-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rezuchova, B., H. Miticka, D. Homerova, M. Roberts, and J. Kormanec. 2003. New members of the Escherichia coli sigmaE regulon identified by a two-plasmid system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 225:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenbluh, A., C. D. B. Banner, R. Losick, and P. C. Fitz-James. 1981. Identification of a new developmental locus in Bacillus subtilis by construction of a deletion mutation in a cloned gene under sporulation control. J. Bacteriol. 148:341-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi, J., M. Bischoff, A. Wada, and B. Berger-Bächi. 2003. MsrR, a putative cell envelope-associated element involved in Staphylococcus aureus sarA attenuation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2558-2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sau, S., J. Sun, and C. Y. Lee. 1997. Molecular characterization and transcriptional analysis of type 8 capsule genes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 179:1614-1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Segall, J., and R. Losick. 1977. Cloned Bacillus subtilis DNA containing a gene that is activated early during sporulation. Cell 11:751-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seidl, K., M. Stucki, M. Ruegg, C. Görke, C. Wolz, L. Harris, B. Berger-Bächi, and M. Bischoff. 2006. Staphylococcus aureus CcpA affects virulence determinant production and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1183-1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senn, M. M., M. Bischoff, C. von Eiff, and B. Berger-Bächi. 2005. SigB activity in a Staphylococus aureus strain Newman hemB mutant. J. Bacteriol. 187:7397-7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh, V. K., J. L. Schmidt, R. K. Jayaswal, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2003. Impact of sigB mutation on Staphylococcus aureus oxacillin and vancomycin resistance varies with parental background and method of assessment. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 21:256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sinha, S., P. Rappu, S. C. Lange, P. Mänmtsälä, H. Zalkin, and J. L. Smith. 1999. Crystal structure of Bacillus subtilis YabJ, a purine regulatory protein and member of the highly conserved YigF family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13074-13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steinhuber, A., C. Goerke, M. G. Bayer, G. Doring, and C. Wolz. 2003. Molecular architecture of the regulatory locus sae of Staphylococcus aureus and its impact on expression of virulence factors. J. Bacteriol. 185:6278-6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thakker, M., J.-S. Park, V. Carey, and J. C. Lee. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus serotype 5 capsular polysaccharide is antiphagocytic and enhances bacterial virulence in a murine bacteremia model. Infect. Immun. 66:5183-5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tzianabos, A. O., J. Y. Wang, and J. C. Lee. 2001. Structural rationale for the modulation of abscess formation by Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:9365-9370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Wamel, W., Y. Q. Xiong, A. S. Bayer, M. R. Yeaman, C. C. Nast, and A. L. Cheung. 2002. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus type 5 capsular polysaccharides by agr and sarA in vitro and in an experimental endocarditis model. Microb. Pathog. 33:73-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Voyich, J. M., K. R. Braughton, D. E. Sturdevant, and A. R. Whitney et al. 2005. Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 175:3907-3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watts, A., D. Ke, Q. Wang, A. Pillay, A. Nicholson-Weller, and J. C. Lee. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus strains that express serotype 5 or serotype 8 capsular polysaccharides differ in virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:3502-3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu, S., H. de Lencastre, and A. Tomasz. 1996. Sigma-B, a putative operon encoding alternate sigma factor of Staphylococcus aureus RNA polymerase: molecular cloning and DNA sequencing. J. Bacteriol. 178:6036-6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]