Abstract

TraP is a triply phosphorylated staphylococcal protein that has been hypothesized to be the mediator of a second Staphylococcus aureus quorum-sensing system, “SQS1,” that controls expression of the agr system and therefore is essential for the organism's virulence. This hypothesis was based on the loss of agr expression and virulence by a traP mutant of strain 8325-4 and was supported by full complementation of both phenotypic defects by the cloned traP gene in strain NB8 (Y. Gov, I. Borovok, M. Korem, V. K. Singh, R. K. Jayaswal, B. J. Wilkinson, S. M. Rich, and N. Balaban, J. Biol. Chem. 279:14665-14672, 2004), in which the wild-type traP gene was expressed in trans in the 8325-4 traP mutant. We initiated a study of the mechanism by which TraP activates agr and found that the traP mutant strain used for this and other recently published studies has a second mutation, an adventitious stop codon in the middle of agrA, the agr response regulator. The traP mutation, once separated from the agrA defect by outcrossing, had no effect on agr expression or virulence, indicating that the agrA defect accounts fully for the lack of agr expression and for the loss of virulence attributed to the traP mutation. In addition, DNA sequencing showed that the agrA gene in strain NB8 (Gov et al., J. Biol. Chem., 2004), in contrast to that in the agr-defective 8325-4 traP mutant strain, had the wild-type sequence; further, the traP mutation in that strain, when outcrossed, also had no effect on agr expression.

Staphylococcal virulence is largely the province of a large set of extracellular proteins that enable the organism to resist host defenses, attach to the tissue matrix, degrade macromolecules, and lyse cellular elements. This constellation of functions is known as the virulon. The production of staphylococcal virulence factors is coordinately controlled by an intricate regulatory network involving several two-component signaling modules and a family of homologous winged-helix transcription factors (1, 3). Central to this regulatory network is the quorum-sensing agr two-component signaling module, which triggers expression of the virulon in response to population density (12). We have recently encountered attenuated clinical strains that possess the wild-type agr sequence but do not express it (19), suggesting that there may be genes extrinsic to the agr locus that stringently control its expression. As identification and characterization of such genes would be basic to our understanding of virulence regulation in staphylococci, we noted with great interest reports that the staphylococcal gene traP (not to be confused with the Escherichia coli conjugation gene, traP) is absolutely required for agr expression (2, 5). Accordingly, we have initiated studies to determine the role of this gene in agr activation. TraP is a phosphoprotein with three conserved histidine residues, which must all be phosphorylated for the protein to activate agr (5). TraP phosphorylation is induced by RAP, a secreted form of ribosomal protein L2, and is inhibited by RIP, a synthetic heptapeptide, YSPWTNF (2). Rap-Trap is thus considered to represent a second agr activation pathway, designated “SQS1” (8), which is superficially similar to the second activating pathway in the competence-regulating system of Bacillus subtilis, which uses the CSF peptide (10).

We were surprised to find, however, that TraP does not, in fact, have any role in agr activation and is not involved in virulence. Therefore, no second agr activation pathway has yet been identified. We find that the derivative of strain 8325-4 containing the traP mutation used in recent studies (5) has an adventitious stop codon in agrA that eliminates agr activation. This mutation is responsible for the failure of the traP mutant to express agr, for its avirulence in the murine abscess model (5), and for the identity of the traP transcriptome with that of agr (7). These findings are entirely consistent with two other reports (15, 20) demonstrating that traP mutations have no effect on agr expression or virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains are listed in Table 1. Several different versions of the common laboratory strains COL and 8325-4 have been used; since both of these strains are known to vary in their agr expression, we considered it necessary to identify their sources, which are indicated in parentheses. Thus, 8325-4(NB) was kindly provided by Naomi Balaban and 8325-4(BW) by Brian Wilkinson. 8325-4(RN) is our lab version of the same strain, and COL(BW) is Brian Wilkinson's version of COL. “-s” after the parentheses indicates that a single colony was isolated from the original plate. Balaban and Wilkinson also have sent us four different isolates, each containing a kanamycin resistance (Kmr) cassette (kan) inserted in the traP coding region, inactivating the gene. Although the traP::kan loci of these four strains are apparently identical, we have numbered them sequentially, as they were analyzed separately. 8325-4traP-1(BW) and COLtraP-2(BW) were provided by Wilkinson, while 8325-4traP-3(NB) and NB8, which is 8325-4traP-4 harboring pYG14, were provided by Balaban. We have transduced traP::kan from all four strains to different recipients. Transductants were named by adding an indication of the donor traP::kan insertion (t1, t2, t3, or t4, referring to the above four traP isolates, respectively) to the recipient strain designation. Thus, 8325-4(RN)t3 is the traP::kan derivative of 8325-4(RN) in which the traP mutation was transduced from 8325-4traP-3(NB), a strain provided by Balaban. These notations are used throughout the text, tables, and figures.

TABLE 1.

S. aureus strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| COL | Genome-sequenced methicillin-resistant strain | 4 |

| COL(BW) | COL | B. Wilkinson |

| COLtraP-2(BW) | COL with kanamycin resistance cassette in traP (traP-2) | B. Wilkinson |

| 8325-4 | NCTC8325 cured of three prophages | 11 |

| 8325-4(RN) | 8325-4 | R. Novick |

| 8325-4(BW) | 8325-4 | B. Wilkinson |

| 8325-4(NB) | 8325-4 | N. Balaban |

| 8325-4traP-1(BW) | 8325-4 with kanamycin resistance cassette in traP [traP-1(BW)] | B. Wilkinson |

| 8325-4traP-3(NB) | 8325-4 with kanamycin resistance cassette in traP (traP-3) | N. Balaban (5) |

| NB8 | 8325-4 with kanamycin resistance cassette in traP (traP-4) and plasmid pYG14 | N. Balaban (5) |

| 8325-4(NB)-s-t3 | 8325-4(NB)-s with traP-3 [80α transductant from 8325-4traP-3(NB)] | This work |

| 8325-4(NB)-s-t4 | 8325-4(NB)-s with traP-4 (80α transductant from NB8) | This work |

| 8325-4(RN)t2 | 8325-4(RN) with traP-2 [80α transductant from COLtraP-2(BW)] | This work |

| 8325-4(RN)t1 | 8325-4(RN) with traP-1 [80α transductant from 8325-4traP-1(BW)] | This work |

| 8325-4(RN)t3 | 8325-4(RN) with traP-3 [80α transductant from 8325-4traP-3(NB)] | This work |

| 8325-4(RN)t4 | 8325-4(RN) with traP-4 (80α transductant from NB8) | This work |

| RN6734 | 8325-4 (φ13 Tn554-ermA1) | R. Novick (14) |

| RN6734t2 | RN6734 with traP-2 [80α transductant from COLtraP-2(BW)] | This work |

| RN6734t1 | RN6734 with traP-1 [80α transductant from 8325-4traP-1(BW)] | This work |

| RN6734t3 | RN6734 with traP-3 [80α transductant from 8325-4traP-3(NB)] | This work |

| RN6734t4 | RN6734 with traP-4 (80α transductant from NB8) | This work |

| RN7206 | RN6734 Δagr::tetM | R. Novick (14) |

| RN7206t3 | RN7206 with traP-3 [80α transductant from 8325-4traP-3(NB)] | This work |

| RN6911 | RN6390 Δagr::tetM | 14 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRN6662 | pSK267 with cloned agrA | 12 |

| pYG14 | pAUL-A::traP | 5 |

Bacterial cultures were stored at −80°C and were grown on GL agar (13) supplemented with antibiotics as required for plasmid selection (erythromycin, chloramphenicol, or tetracycline, all at 10 μg/ml), on commercial sheep blood agar (SBA) (from BBL), or in CY broth (13). Culture density was monitored with a Molecular Devices microtiter plate reader at 650 nm. Blood agar plates were photographed with an α-Innotech imager after 18 h of growth at 37°C. Phage lysates were prepared and used for transduction as previously described (13).

Determination of hemolytic activities and protease production.

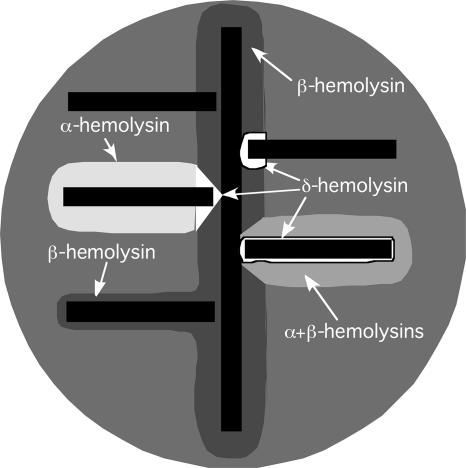

Qualitative evaluation of α-, β-, and δ-hemolysin production was evaluated on SBA as shown in Fig. 1. Protease production was evaluated on casein agar as described by Karlsson et al. (6).

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of hemolytic activities on SBA. Bacteria to be tested (horizontal black bars) are streaked at a right angle to RN4220 (vertical black bar) and the plate incubated overnight. β-Hemolysin forms a turbid zone of hemolysis surrounding the vertical streak of RN4220. δ-Hemolysin and β-hemolysin are synergistic, producing a zone of clear hemolysis where they intersect. Three such zones are shown. At the upper right is a strain producing only δ-hemolysin. Below that is a strain producing all three hemolysins. The α-hemolysin zone is more turbid than seen with α-hemolysin alone because of inhibition by β-hemolysin. In this case, δ-hemolysin produces a narrow clear zone surrounding the streak owing to its interaction with β-hemolysin. At the upper left is a nonhemolytic strain; next is a strain producing α-hemolysin and δ-hemolysin. The V-shaped zone is characteristic of the intersection of α-hemolysin and β-hemolysin zones, as α-hemolysin and β-hemolysin are mutually inhibitory. Within the region of intersection, β-hemolysin and δ-hemolysin interact to give a region of greater clearing than that seen with α-hemolysin alone. At the lower left is a strain producing only β-hemolysin.

Determination of exoprotein profiles.

Cultures were grown for 6 h in CY broth without glucose; 1.5-ml aliquots were centrifuged to remove bacteria and then analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis according to the method of Laemmli (9), stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and photographed.

Plasmid screening.

Whole-cell lysates for plasmid screening were prepared and analyzed as previously described (13).

PCRs and sequencing of agrA and traP.

PCRs used the primer pairs listed in Table 2. Amplification was carried out using the following parameters: 30 s of denaturation at 94°C; 40 cycles of amplification at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 56°C, and 2 min of extension at 72°C; and a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. For traP, the same set of primer pairs were used for both PCR and sequencing. For agrA, primers agrA F and a14 R were used to sequence the PCR product amplified by primers agrA F and agrA R. Sequencing was done by dye terminator DNA sequencing chemistry (Skirball DNA Sequencing Core Facility). DNA sequences were analyzed with the DNAStar sequence analysis suite.

TABLE 2.

Primers

| Primer type and name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| Northern blot probes | |

| 16S F | GGTGAGTAACACGTGGATAA |

| 16S R | ATGTCAAGATTTGGTAAGGTT |

| RNAIII F | CTGAGTCCTAGGAAACTAACTC |

| RNAIII R | ATGATCACAGAGATGTGA |

| PCR and sequencing primers | |

| agrA F | ATTAACAACTAGCCATAAGG |

| agrA R | TGATCCTAATGTAAGATTGC |

| a14 R | GTTCGAATTCACGCGTCATATTTAA |

| traP F | CAATAACCCGACCCATCAAC |

| traP R | GTCTTCGTATGCATGTCG |

RNA preparation and Northern blot hybridization (New York).

Cell pellets were treated with RNA Protect reagent (QIAGEN) and mechanically disrupted by agitation with glass beads using the Bio101 FastPrep apparatus. RNA was purified using the QIAGEN RNeasy kit and its integrity checked by agarose gel electrophoresis. RNA samples corresponding to equal numbers of cells were separated by gel electrophoresis through 1% denaturing agarose (MOPS [morpholinepropanesulfonic acid]-formaldehyde), vacuum blotted to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham), and UV cross-linked. Blots were hybridized overnight to [α-32P]dATP-labeled, PCR-generated probes. Washed blots were exposed to phosphorimager screens and were read with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager. Primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) used for synthesizing probes are listed in Table 2. Slightly different methods were used in Stockholm, as described by Tegmark et al. (17).

Analysis of virulence.

Ten-week-old mice of the hairless strain (HRS/J-hr ES10b/+ES10b) (Charles River Laboratories) were injected subcutaneously in the flank area with 109 CFU of the test strain in 100 μl phosphate-buffered normal saline plus Cytodex beads and observed daily for 5 days, at which time they were photographed and euthanatized.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Some of the results described here were obtained in New York and others were obtained independently in Stockholm, as noted in the figure legends.

Scoring of S. aureus phenotypes.

We routinely score hemolytic activities of S. aureus strains on commercially available SBA plates (16) (18), using δ-hemolysin and/or α-hemolysin activity as a surrogate for agr function. It will be recalled that S. aureus produces at least four hemolytic toxins, α, β, δ, and γ, of which the first three can be scored directly on SBA and the fourth cannot, as it is inhibited by agar. β-Hemolysin, which produces a wide turbid zone, is only weakly regulated by agr, whereas α- and δ-hemolysins are strongly up-regulated. Additionally, δ-hemolysin has very weak activity on SBA but is strongly synergistic with β-hemolysin. Accordingly, we cross-streak strains to be tested against RN4220, which produces only β-hemolysin (17). Since β-hemolysin partially inhibits α-hemolysin, production of the latter is more easily detected in φ13 lysogens in which the β-hemolysin gene is insertionally inactivated. RN6734 is a φ13 lysogen, whereas 8325-4 is not. These features of hemolysin scoring are illustrated diagrammatically in Fig. 1. We routinely score protease activity on casein agar plates (6). Protease-positive strains produce a white precipitate against a turbid background.

To begin a study of upstream genes required for agr activation, we sought to investigate the mechanism by which traP activates agr, as revealed by hemolytic activity on SBA and protease activity on casein agar. Gov et al. (5) analyzed a traP mutation in which the gene was inactivated by the insertion of a Kmr cassette (5). During the course of these studies, we obtained three pairs of strains, each consisting of a parental traP+ strain and a traP::kan derivative with the Kmr cassette inserted in the unique EcoRI site of the traP gene (5). Brian Wilkinson provided us with two pairs of strains: 8325-4(BW) and its traP::kan derivative, 8325-4traP-1(BW), and COL(BW) and its traP::kan derivative, COLtraP-2(BW). Naomi Balaban provided us with parental traP+ strain 8325-4(NB) and its traP::kan derivative, 8325-4traP-3(NB). All three strain pairs were scored on SBA for α- and δ-hemolysins. None of the traP::kan strains made α- or δ-hemolysin, suggesting that agr was inactive, as reported previously (5). The 8325-4traP-3(NB) parent [8325-4(NB)] appeared normally hemolytic, but the 8325-4traP-1(BW) parent [8325-4(BW)] was only weakly hemolytic, and the COLtraP-2(BW) parent [COL(BW)] was totally nonhemolytic (which was not surprising, since most available COL derivatives are nonhemolytic [unpublished observations]). The 8325-4traP-3(NB) strain and its parent were also scored on casein agar for protease activity. The mutant was protease negative and the parent was protease positive, consistent with published reports. These observations are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Phenotypes of donor and transductant strains

| Strain | Activity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemolysin

|

Protease | |||

| α | δ | β | ||

| COL(BW)a | − | − | + | |

| COLtraP-2(BW) | − | − | + | |

| 8325-4(BW)a | ± | ± | + | |

| 8325-4traP-1(BW) | − | − | + | |

| 8325-4(NB)a | ± | ± | + | + |

| 8325-4traP-3(NB) | − | − | + | − |

| 8325-4(NB)-s | + | + | + | |

| 8325-4(NB)-s-t3b | + | + | + | |

| 8325-4(RN)a | + | + | + | + |

| 8325-4(RN)t1b | + | + | + | |

| 8325-4(RN)t2b | + | + | + | |

| 8325-4(RN)t3b | + | + | + | + |

| 8325-4(RN)t4b | + | + | + | |

| RN6734(RN)a | + | + | − | |

| RN6734(RN)t1b | + | + | − | |

| RN6734(RN)t2b | + | + | − | |

| RN6734(RN)t3b | + | + | − | |

Parental strain.

All of 10 Kmr transductants.

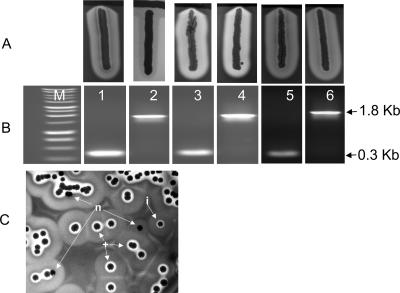

To confirm the role of traP in these strains, we transferred the traP-inactivating Kmr cassette from each of the traP::kan derivatives to RN6734, our standard agr+ strain, and were surprised to find that in each case all of 10 transductants had the same fully hemolytic phenotype as the recipient strain (Table 3). Typical results with traP-3 are shown in Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4.

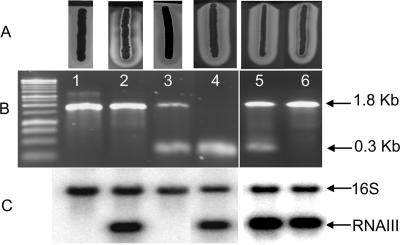

FIG. 2.

Effects of traP-3 on hemolytic activity of S. aureus (experiments performed in New York). (A) Hemolytic patterns on SBA with RN4220 (black streak at top). (B) PCR products obtained with primers that would amplify either traP (0.3-kb band) or traP with the Kmr insert (1.8-kb band). Lanes: 1, 8325-4(NB) from N. Balaban; 2, 8325-4traP-3(NB), also from N. Balaban (note the faint turbid β-hemolysin zone surrounding this streak); 3, RN6734 (standard agr+ traP+, φ13 lysogen); 4, RN6734t3 (Kmr traP-3 transductant of RN6734); 5, 8325-4(RN); 6, 8325-4(RN)t3 [Kmr traP-3 transductant of 8325-4(RN)]. (C) Single-colony hemolytic patterns on SBA of the 8325-4(NB) culture provided by N. Balaban, containing at least 3 types of colonies: +, showing zones for β-hemolysin and δ-hemolysin [one of these was isolated and used in further studies and was designated 8325-4(NB)-s (α-hemolysin is produced but is difficult to identify in such single colonies)]; n, producing only β-hemolysin; i, possible intermediate type.

Confirmation of genotypes and phenotypes.

At this point, it was clearly necessary to confirm the genotypes of these various strains and to test their phenotypes by more definitive means than simply scoring for hemolysis on SBA or proteolysis on casein agar. A PCR performed on each of the traP::kan mutants, the RN6734 transductants, and the corresponding traP+ parental strains, with the primers as listed in Table 2, all gave the expected products: a 0.3-kb product corresponding to traP for the traP+ strains and a 1.8-kb product corresponding to the inserted Kmr cassette for the traP::kan strains. Typical results are shown in Fig. 2B. The traP locus for representative examples of these various parental and transductant strains was sequenced, confirming either the native traP sequence or the inserted Kmr cassette as expected (not shown).

Since the transductions described above were to RN6734, we sought to rule out the possibility that strain variation could be responsible for the observed results, by backcrossing the traP-3 mutation to its 8325-4 parent [8325-4(NB)]. For this backcross, 8325-4traP-3(NB) and the parental strain 8325-4(NB) were restreaked on SBA from the confluent growth areas of the original agar plates kindly provided by Naomi Balaban. As reported previously (5), the 8325-4traP-3(NB) strain did not produce α- and δ-hemolysins or protease, and 8325-4(NB) produced both. However, as shown in Fig. 2C, the 8325-4(NB) culture was mixed, generating mostly strongly hemolytic colonies, some producing β-hemolysin only, (∼20%), and probably an intermediate type with reduced hemolytic activity (∼5%). Such mixtures are typical of 8325-4 stock cultures, owing to the well-known propensity of agr+ strains to throw agr-defective mutants; indeed, our own 8325-4 stock culture has recently been found to contain such a mixture (18). Nevertheless, we considered it necessary to guard against the possibility that these variants represented contaminants introduced by ourselves. Therefore, to begin work with this strain, three different members of the laboratory independently prepared similar SBA subcultures from the original plate. One of these is illustrated in Fig. 2C; the others were all similar (not shown). We note also that single-colony isolates of all 8325-4 substrains tested, including a strongly hemolytic single-colony isolate from the original 8325-4(NB) culture (Fig. 2C), designated 8325-4(NB)-s, breed true during daily handling but that agr mutants accumulate during storage (unpublished data). Accordingly, we used 8325-4(NB)-s, which produces all three hemolysins, for further study, routinely testing it on SBA before any experiment, and we have not worked further with the other variants seen in Fig. 2C.

Transfer of the traP-3 mutation.

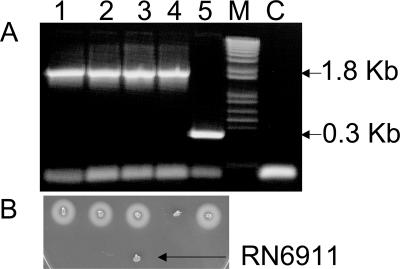

Transduction of traP-3 to this single-colony hemolytic isolate was performed as described above, with selection for Kmr. All of the Kmr transductants were fully hemolytic and fully proteolytic, indistinguishable from the recipient strain [8325-4(NB)-s] on SBA or on casein agar, ruling out the possibility that the effects of traP are strain specific. We note that in-frame traP deletions have recently been constructed in several clinical strains as well as in 8325-4(RN) by Tsang et al. (20) and that none of these had any effect on agr activity. Typical results are shown in Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 6, and in Fig. 3B. These results suggested strongly that traP does not, in fact, control agr-regulated hemolysins or proteases, and they led to a series of experiments to test this possibility further. To be absolutely certain that our traP-3 strains had the correct chromosomal configuration, we performed PCRs, as described above for traP-1 and -2, using primers specific for the traP-chromosomal junctions (Table 2). These results, also shown in Fig. 2B and 3A, fully confirmed the expected genotypes. The traP+ strain had the predicted 0.3-kb product derived from within the traP gene (Fig. 2B, lane 1, and 3A, lane 5), and all of three traP-3 transductants tested had the predicted 1.8-kb product generated by the insertion of the Kmr cassette into traP (Fig. 2B, lane 6, and 3A, lanes 1 to 3). These findings were also confirmed by sequencing (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Effect of traP-3 on protease production by S. aureus (experiments performed in Stockholm). (A) PCR analysis of traP with (lanes 1 to 4) and without (lane 5) the kan insertion. In lane 4 is 8325-4traP-3(NB) (N. Balaban's traP mutant), and lanes 1 to 3 represent Kmr transductants of 8325-4(RN) with 8325-4traP-3(NB) as the donor. Lane M, size marker; lane C, negative control without bacterial DNA. (B) Protease indicator plate (casein agar) with stabs of the strains shown in panel A. RN6911 is an agr-null strain; note that strain 8325-4traP-3(NB) (N. Balaban's traP-3 mutant) (lane 4), like RN6911, shows no protease activity, whereas the transductants (lanes 1 to 3) are fully active, as is the 8325-4(RN) recipient (lane 5).

Gene expression analysis.

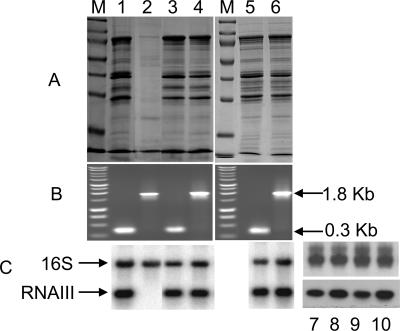

If TraP controls agr activation, since it does not control the production of agr-regulated hemolysins, perhaps it might affect the synthesis of other agr-regulated proteins. If so, one would expect clear differences in exoprotein profiles and in gene expression between traP+ and traP::kan strains. Accordingly, we determined exoprotein profiles for several of the strains described above and performed Northern blotting for RNAIII, the regulatory RNA that is the effector of the agr response (14). In Fig. 4A are shown the exoprotein profiles and in Fig. 4C the RNAIII blots, with PCR confirmation in Fig. 4B, as described above. Again, with one exception, both the exoprotein profiles and the RNAIII blots are consistent with full agr expression in the absence as well as in the presence of an intact traP gene. Further confirmation was obtained in an experiment in which culture samples taken at the 4- and 6-h time points were also Northern blotted with an RNAIII probe (Fig. 4C, lanes 7 to 10). The exception was the nonhemolytic traP strain [8325-4traP-3(NB)] provided by Naomi Balaban (lane 2), which had an exoprotein profile typical of agr-null strains (14) and did not produce detectable RNAIII. The apparent lack of any effect of traP-3 in the other strains tested raises the question of the basis of the profound deficiency in hemolytic activity and exoprotein production seen with this strain.

FIG. 4.

Effect of traP-3 on exoprotein profiles and agr-RNAIII production. (A) Six-hour culture supernatants were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis according to the method of Laemmli (9), stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, and photographed. (B) PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA as in Fig. 3. Lanes: 1, 8325-4(NB); 2, 8325-4traP-3(NB); 3, 8325-4(RN); 4, 8325-4(RN)t3 [Kmr transductant of 8325-4(RN)]; 5, RN6734; 6, RN6734t3 (Kmr transductant of RN6734). (C) Northern blot hybridization analysis of RNAIII. Lanes 7 and 8, 4-h culture samples; lanes 9 and 10, 6-h samples. The samples in lanes 7 and 9 are from an 8325-4(RN) culture; those in lanes 8 and 10 are from an 8325-4(RN)t3 culture. Results shown in lanes 1 to 6 are from experiments performed in New York; those in lanes 7 to 10 are from experiments performed in Stockholm.

The simplest explanation would be that there is an adventitious agr mutation in the traP-3 derivative of 8325-4. Since such mutations are common and often affect agrA, we introduced pRN6662, an agrA-expressing plasmid that we have previously used to complement agrA mutations (14), by transduction to the nonhemolytic traP-3 derivative of 8325-4, 8325-4traP-3(NB), selecting for the chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) marker of the plasmid. All of the transductants contained the agrA-expressing plasmid and were fully hemolytic, despite the continued presence of the traP-3 mutation, suggesting that a mutation in agrA was responsible for the agr-defective phenotype of this strain, rather than the traP-3 mutation. Hemolytic patterns and confirmation of these genotypes by PCR and Northern blotting are shown in Fig. 5. To confirm the presence of an agrA mutation, we sequenced agrA from chromosomal DNA prepared directly from the nonhemolytic 8325-4traP-3(NB) bacteria on the agar plate provided by Naomi Balaban and found a stop codon at amino acid position 124 (Fig. 6). This has been confirmed with several other strains derived from this one. These results provide unequivocal evidence that traP has no detectable role in agr regulation and that, with one exception, the recently reported results for traP (5, 7) can all be accounted for by an adventitious mutation in agrA. The exception is the hemolytic strain NB8, kindly provided by Naomi Balaban, described as a traP derivative of 8325-4(NB) containing pYG14, a traP-expressing plasmid. This plasmid was reported to complement the nonhemolytic and avirulent phenotype of the 8325-4traP-3(NB) strain (5).

FIG. 5.

Complementation of 8325-4traP-3(NB) by cloned agrA but not by cloned traP. (A and B) Hemolytic patterns (A) and PCR analysis (B) as in Fig. 2. (C) Northern blot hybridization patterns using 16S RNA and agr-RNAIII probes as indicated. The same 6-h culture samples used for PCR were also used for whole-cell RNA extraction. RNA samples were separated on agarose and Northern blotted with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides specific for 16S RNA and agr-RNAIII, respectively. Blots were developed with a phosphorimager. Lanes: 1, 8325-4traP-3(NB); 2, 8325-4traP-3(NB) containing cloned agrA; 3, 8325-4traP-3(NB) containing cloned traP; 4, 8325-4(RN); 5, NB8; 6, 8325-4(RN)t4 [Kmr transductant of 8325-4(RN) with NB8 as the donor].

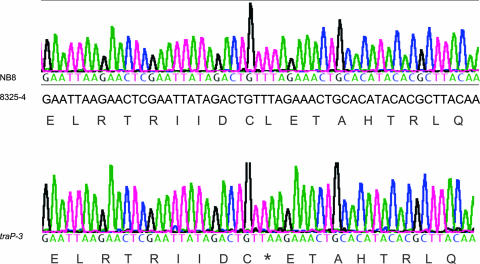

FIG. 6.

Sequencing of agrA. The electropherogram of the sequencing reaction for agrA in strain 8325-4traP-3(NB) is shown at the bottom, with the deduced nucleotide and amino acid sequences below. At the top is the agrA sequence for strain NB8 in comparison to the 8325-4(RN) agrA sequence from GenBank.

Complementation.

How may we account for the hemolytic activity and virulence of strain NB8? Although we could detect no phenotype for the traP knockout, it was possible that the presence of traP on a high-copy plasmid might be responsible. We began by confirming the presence of both the traP mutation and the traP-expressing plasmid, pYG14, in NB8. As shown in Fig. 5B (lane 5), PCR products corresponding to both the intact and insertionally inactivated traP were present, and the expected plasmid was readily detectable in screening gels (not shown). Moreover, a Kmr transductant of 8325-4(RN) with NB8 as the donor showed the traP-specific 1.8-kb PCR product. However, like all other transductants, this transductant [8325-4(RN)t4] was fully hemolytic and produced normal amounts of RNAIII (Fig. 5C, lane 6). We next determined the sequence of agrA in NB8, in comparison to that in the nonhemolytic 8325-4traP-3(NB) strain, and found, again to our surprise, that the NB8 agrA sequence was the same as that previously determined for wild-type agrA (GenBank accession no. SAOUHSC_02265); i.e., it did not contain the above-mentioned stop codon present in the nonhemolytic traP strain 8325-4traP-3(NB) (Fig. 6). Additionally, we transduced the traP-containing plasmid from the hemolytic traP strain, NB8, to the nonhemolytic traP derivative of 8325-4, 8325-4traP-3(NB), selecting for the erythromycin resistance (Emr) marker of the plasmid. All of 10 Emr transductants tested were nonhemolytic and contained the plasmid (not shown). They were phenotypically indistinguishable from the recipient strain, indicating that the cloned traP does not restore hemolysin production to this strain. PCR analysis confirmed that both intact and inactivated traP genes were present in the plasmid-containing strains (Fig. 5B, lane 3). Finally, we also transduced the traP-4 mutation from NB8 to the agr+ 8325-4(NB)-s, and again, all of 10 Kmr transductants were fully hemolytic and indistinguishable from the recipient strain. As noted above, in-frame traP deletion mutations also had no detectable effect on agr expression (20), ruling out the possibility that a polar effect of the inserted kan cassette may have been responsible for the traP mutant phenotype. The reported complementation, therefore, is explainable by the lack of any agr defect in strain NB8.

Virulence.

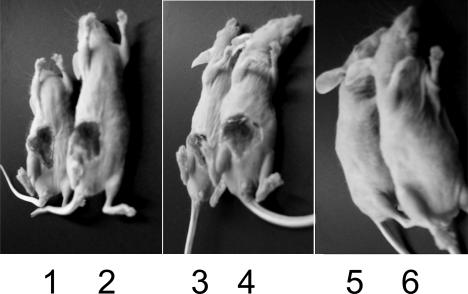

The results described above suggest that all of the in vitro properties of the traP mutations containing the kanamycin resistance cassette are attributable to the agrA mutation, and they predict that this mutation also accounts for the reported avirulence of the 8325-4traP-3(NB) strain. This prediction was tested with 10-week-old hairless immunocompetent mice. We used six strains: RN6734, RN6734t3 (our traP-3 derivative), RN7206 (an agr-null derivative of RN6734), and RN7206t3 (a double traP-3 agr-null derivative of RN6734), plus the hemolytic 8325-4(NB)-s and 8325-4(NB)-s-t3 (our traP-3 transductant of this strain). Mice were injected subcutaneously with 109 CFU plus Cytodex beads in a total vol of 100 μl of normal saline, and the resulting lesions were measured after 5 days.

Several of the mice died in this experiment, because the dose of bacteria that we used, in conformity with the dose used by Gov et al. (5), was considerably higher than the 3 × 108 CFU that we normally use in this model. In this test, both of the agr+ traP-3 strains tested were highly virulent. Although, as listed in Table 4, the lesions may have been slightly smaller than those with the traP+ strain, there was considerable variation and the differences are clearly not significant. Typical lesions are shown in Fig. 7. Neither the agr nor the agr traP-3 double mutant caused any measurable lesion at this dosage.

TABLE 4.

Effect of traP-3 on abscess formation

FIG. 7.

Effects of traP on virulence in the murine subcutaneous abscess model. See text for details. Odd-numbered mice were infected with traP+ bacteria, and even-numbered mice were infected with traP-3. Strains: 1 and 2, 8325-4(NB)-s; 3 and 4, RN6734; 5 and 6, RN7206.

Conclusion.

A possible explanation for the presence of an adventitious agrA mutation in the traP strain 8325-4traP-3(NB) is that a transductant with this mutation was chosen accidentally when traP was initially transferred to 8325-4(NB), which we have observed to contain nonhemolytic variants (Fig. 2C). This same traP, agrA-defective strain was apparently used for the testing of the plasmid-carried phosphorylation-defective traP mutants (5), as well as for the reported transcriptional profiling (7), so that these results would also be due to the agrA mutation.

However, given the results presented above, we are unable to envision any explanation either for the wild-type agrA sequence in strain NB8 or for the retention of hemolytic activity and virulence by the same host strain with a traP plasmid containing a mutation in a nonphosphorylatable histidine (5) (Fig. 6 and 7).

The results reported here unfortunately call into question the initial report (2) in which the properties of traP were described. In that report, a traP-inactivating mutation was constructed and tested in the α- and δ-hemolysin-negative strain RN4220, in which we have recently demonstrated a partially inactivating mutation in agrA (18). The reported effects of traP on RNAIII synthesis may also have resulted from an additional and adventitious agr-defective mutation, which would not have been noticed since RN4220 produces neither α- nor δ-hemolysin, owing to its agrA defect. Although it was reported that the primary traP mutation was outcrossed to 8325-4 and its properties were conserved (2), no data were presented. Unfortunately, neither OU20, the traP mutant derivative of RN4220 used in that study, nor the traP 8325-4 transductant are presently available.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH research grant R01-AI30138 to R.P.N.

We thank Brian Wilkinson and Naomi Balaban for providing many of the strains used in the study.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 July 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arvidson, S., and K. Tegmark. 2001. Regulation of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:159-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balaban, N., T. Goldkorn, Y. Gov, M. Hirshberg, N. Koyfman, H. R. Matthews, R. T. Nhan, B. Singh, and O. Uziel. 2001. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis via target of RNAIII-activating protein (TRAP). J. Biol. Chem. 276:2658-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung, A. L., and G. Zhang. 2002. Global regulation of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus by the SarA protein family. Front. Biosci. 7:1825-1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill, S. R., D. E. Fouts, G. L. Archer, E. F. Mongodin, R. T. Deboy, J. Ravel, I. T. Paulsen, J. F. Kolonay, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, R. J. Dodson, S. C. Daugherty, R. Madupu, S. V. Angiuoli, A. S. Durkin, D. H. Haft, J. Vamathevan, H. Khouri, T. Utterback, C. Lee, G. Dimitrov, L. Jiang, H. Qin, J. Weidman, K. Tran, K. Kang, I. R. Hance, K. E. Nelson, and C. M. Fraser. 2005. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J. Bacteriol. 187:2426-2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gov, Y., I. Borovok, M. Korem, V. K. Singh, R. K. Jayaswal, B. J. Wilkinson, S. M. Rich, and N. Balaban. 2004. Quorum sensing in staphylococci is regulated via phosphorylation of three conserved histidine residues. J. Biol. Chem. 279:14665-14672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlsson, A., P. Saravia-Otten, K. Tegmark, E. Morfeldt, and S. Arvidson. 2001. Decreased amounts of cell wall-associated protein A and fibronectin-binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus sarA mutants due to up-regulation of extracellular proteases. Infect. Immun. 69:4742-4748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korem, M., Y. Gov, M. D. Kiran, and N. Balaban. 2005. Transcriptional profiling of target of RNAIII-activating protein, a master regulator of staphylococcal virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:6220-6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korem, M., A. S. Sheoran, Y. Gov, S. Tzipori, I. Borovok, and N. Balaban. 2003. Characterization of RAP, a quorum sensing activator of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 223:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriaphage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazazzera, B. A., J. M. Solomon, and A. D. Grossman. 1997. An exported peptide functions intracellularly to contribute to cell density signaling in B. subtilis. Cell 89:917-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novick, R. P. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick, R. P., S. J. Projan, J. Kornblum, H. F. Ross, G. Ji, B. Kreiswirth, F. Vandenesch, and S. Moghazeh. 1995. The agr P2 operon: an autocatalytic sensory transduction system in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248:446-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novick, R. P. 1991. Genetic systems in staphylococci. Methods Enzymol. 204:587-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novick, R. P., H. F. Ross, S. J. Projan, J. Kornblum, B. Kreiswirth, and S. Moghazeh. 1993. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 12:3967-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw, L. N., I. -M. Jonsson, V. K. Singh, A. Tarkowski, and G. C. Stewart. 2007. Inactivation of traP has no effect on the Agr quorum-sensing system or virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 75:4519-4527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subedi, A., C. Ubeda, J. R. Penades, and R. P. Novick. Sequence analysis reveals genetic rearrangements and intraspecific spread of SaPI2, a pathogenicity island involved in menstrual toxic shock. Microbiology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Tegmark, K., A. Karlsson, and S. Arvidson. 2000. Identification and characterization of SarH1, a new global regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 37:398-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traber, K., and R. Novick. 2006. A slipped-mispairing mutation in AgrA of laboratory strains and clinical isolates results in delayed activation of agr and failure to translate delta- and alpha-haemolysins. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1519-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traber, K. T., and R. P. Novick. agr functionality in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Microbiology, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Tsang, L. H., S. T. Daily, E. C. Weiss, and M. S. Smeltzer. 2007. Mutation of traP in Staphylococcus aureus has no impact on expression of agr or biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 75:4528-4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]