Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide (18, 60, 63). Though these E. coli pathotypes are genetically related, many features of their epidemiology, their pathogenesis, and the niches they occupy within the human host are unique. EPEC causes profuse watery diarrhea, primarily in children under the age of 2 years, and mostly affects individuals residing in developing countries. In contrast, adults and children infected by EHEC bacteria can suffer from either bloody or nonbloody diarrhea, and in a small percentage of cases a life-threatening complication known as hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) occurs. Many patients with HUS experience long-term renal damage, and they often require dialysis or kidney transplantation. EHEC produces Shiga toxins (Stx), which can cause damage to renal endothelial cells, resulting in HUS, while EPEC bacteria do not possess stx (72). EHEC disease appears in primarily industrialized nations yet causes fewer disease outbreaks in developing countries. This observation has been anecdotally attributed to immunological cross-protection from the related EPEC bacteria prevalent in the less developed regions of the world.

There are two additional important differences that distinguish these two E. coli pathotypes. Approximately 108 to 1010 EPEC bacteria are necessary to cause infection in adult human volunteers (6, 27), while the infectious dose for EHEC is far less, estimated to be less than 100 CFU (49). Intriguingly, EPEC infects the small intestine; EHEC infects the large bowel, inflicting bloody diarrhea resulting from damage to the colon. Variants of the outer membrane protein intimin, expressed by both pathotypes, have been implicated as contributors to tissue tropism (103), but whether intimin is the initial adhesin and, secondly, whether other factors contribute to the ability of EPEC to recognize the small bowel and of EHEC to colonize the large bowel are not clearly understood.

AE.

EPEC and EHEC share genetic and phenotypic similarities, most notably the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (PAI), encoding a type III secretion system (TTSS), and the ability to form attaching and effacing (AE) intestinal lesions, intimate attachment to the host cell, and formation of “pedestals” cupping individual bacteria (86); for recent reviews, see references 12, 60, and 95. The LEE PAI is essential for disease for both EPEC and EHEC bacteria (27, 31, 105). The EPEC LEE expressed from a multicopy plasmid transformed into a K-12 laboratory strain of E. coli was necessary and sufficient to form the AE phenotype on human epithelial cells in culture (80). In contrast, the EHEC LEE alone was not sufficient to confer the AE phenotype when expressed in a laboratory strain of E. coli (33), suggesting that factors and/or regulatory proteins necessary for this phenotype exist outside the EHEC LEE. Indeed, TccP (Tir-cytoskeleton-coupling protein [also called EspFu], a protein with 24% amino acid identity to EspF) is encoded within the CP-933U cryptic prophage in EHEC, is translocated through the TTSS, and is necessary for actin accumulation and thus AE lesion formation by EHEC on human epithelial cells in culture (10, 40). It is now known that at least 39 proteins are translocated through the LEE-encoded EPEC and EHEC TTSSs into the host cell cytosol (39, 133). Many of the non-LEE-encoded TTSS-dependent effector proteins are found within cryptic prophages (133).

Flagellar motility.

The role of flagellar motility in EPEC and EHEC pathogenesis is not clearly defined, though it has been observed that the flagellum itself can contribute to EPEC adherence to epithelial cells in culture (43), and flagella contribute to colonization in a chick model of EHEC infection (69). Quorum sensing controls flagellum expression (15, 17), and this observation is discussed below.

LA phenotype.

Clinical identification of EPEC strains has classically included their ability to attach to cultured epithelial cells in what has been termed localized adherence (LA) (110). This phenotype requires the type IV, bundle-forming pilus (BFP) (26, 42, 116, 117, 126) and is indicated by the formation of microcolonies, in general between 5 and 200 individual bacteria in three-dimensional clusters on the surface of the epithelial cells. The genes encoding the BFP are located on the 70- to 90-kb E. coli attachment factor (EAF) virulence plasmid. EPEC strains deleted for bfpA, the gene encoding the major subunit of the BFP, are attenuated for virulence in human volunteers (6). Some studies indicate that BFP is the initial attachment factor conferring adherence to the human intestinal epithelia and tissue specificity (42), but other studies have indicated that EPEC can adhere to intestinal epithelial cells and form AE lesions in the absence of BFP (53).

EHEC plasmid pO157.

Though the EHEC pathotype does not possess the BFP, these strains do contain a virulence plasmid, pO157. Plasmid pO157 gene-encoded proteins implicated in EHEC pathogenesis include HlyA, a hemolysin; EspP, an autotransported serine protease involved in the cleavage of human coagulation factor V (7); ToxB, a 362-kDa protein sharing amino acid sequence similarity with the large Clostridium toxin family, which is involved in adherence to epithelial cells in culture (128); a catalase; and StcE, a zinc metalloprotease. StcE is secreted by the etp type II secretion system, cleaves the C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) of the complement pathway, has mucinase activity, and is thought to be involved in colonization and tissue damage (50, 70).

Over the past decade we have gained considerable knowledge concerning the regulation of EPEC and EHEC virulence genes and their associated phenotypes. Because of the essential link between diarrheal disease and expression of the TTSS, i.e., assembly of the secretion apparatus and translocation of effector proteins into the host cell cytoplasm leading to altered cell signaling events and ultimately diarrhea, much focus has been devoted to understanding regulation of genes located within the LEE PAI. Certainly these studies help us to better our understanding of the microbe-host interaction, how EPEC and EHEC perceive and respond to host-associated environmental cues, and understand the important similarities and differences between these two E. coli pathotypes. This review summarizes the current knowledge of virulence gene regulation of EPEC and EHEC, draws together a global regulatory network, and finally discusses how our understanding of virulence gene regulation of these two important pathogens is being utilized to develop novel therapies against E. coli diarrhea.

REGULATION

Control of AE lesion formation and protein secretion.

Pathogenic bacteria must respond properly to their surrounding environment to coordinate virulence gene expression and to survive within a specific niche. Elucidation of the kinetics of AE lesion formation demonstrated that this complex phenotype is tightly regulated in response to temperature and growth phase. Activation of EPEC at 37°C in tissue culture medium enhanced the formation of AE lesions on human epithelial cells in culture (108). AE lesions do not form if the bacteria are incubated at 28°C prior to infecting host cells at 37°C, and they are formed more readily by cultures in the early exponential phase of growth. Consistent with the temperature control of AE lesion formation, protein secretion via the EPEC TTSS occurs maximally at host body temperature in tissue culture medium such as Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), at pH 7, and at physiological osmolarity (64, 65). Secretion of EspA, EspB, EspC, and Tir proteins is also stimulated in the presence of iron and sodium bicarbonate, whereas it was inhibited by ammonium chloride or by omission of calcium from the growth medium (57).

Genetic organization of the LEE.

Studies to elucidate transcriptional control of the TTSS, and thus the AE phenotype, were assisted by characterization of the genetic organization of the EPEC LEE (33, 82, 109). The LEE1, LEE2, and LEE3 operons encode the type III apparatus components that span the inner and outer membranes, including EscC, the outer membrane porin, and EscN, the ATPase of the system. The LEE4 operon encodes the EspA protein, the monomer that polymerizes to form the filament over the EscF needle structure necessary for injection of effector molecules into the host cell cytoplasm (68); EspB and EspD, which form a pore in the host cell membrane (56); and EspF, which is injected into the host cell and targeted to the mitochondria, where it plays a role in the cell death pathway (94). EspF has also been demonstrated to disrupt transepithelial cell resistance, leading to disruption of tight junctions (81). The LEE5 operon encodes the Tir and intimin proteins, which are necessary for intimate attachment to the host epithelium, and CesT, a chaperone for Tir (33, 74).

Silencing by H-NS.

As with many virulence systems of gram-negative pathogens, H-NS plays an important role in the silencing of genes of the LEE and is responsive to multiple environmental signals and regulatory proteins (Fig. 1A). In EPEC, the LEE1 operon is repressed by H-NS at 27°C and activated at 37°C (135). H-NS binds to EPEC LEE1, LEE2, and LEE3 regulatory DNA and thus directly controls LEE transcription. Genetic and biochemical analyses have indicated that H-NS silences by binding over extended regions and is capable of bridging or looping DNA (21, 22, 28).

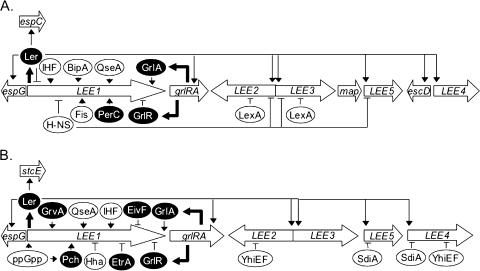

FIG. 1.

Regulation of the LEE PAI in EPEC (A) and EHEC (B). Thin arrows represent positive regulatory signals, and thin blunt arrows represent negative signals. Solid arrows indicate expression of regulatory proteins. Horizontally acquired regulatory proteins appear in ovals with a black background, and regulatory proteins endogenous to E. coli are within ovals with a white background. See Tables 1 and 2 for listings of specific regulators.

The Ler regulatory cascade.

The LEE1-located Ler (LEE-encoded regulator) has emerged as a key regulator of the EPEC AE phenotype, exerting its effect at the level of transcription (82) (Fig. 1A). Ler exerts tight control over the genes of the LEE, as a ler mutant of the prototypical EPEC strain E2348/69 is severely diminished in its ability to form AE lesions on epithelial cells in culture (34, 37). The predicted 15.1-kDa Ler protein exhibits amino acid sequence similarity with the H-NS family of DNA-binding proteins and shows greater similarity to the C terminus of H-NS, which is predicted to be a DNA-binding domain (120). Ler is clearly distinct from H-NS because all other members of this protein family identified to this date silence transcription, either directly or indirectly. In a cascade fashion, upon reaching host body temperature the LEE1-encoded Ler protein increases transcription of the LEE2, LEE3, LEE4, and LEE5 operons as well as espG, escD, and map of the LEE (9, 34, 51, 73, 82, 109, 120, 135). Ler also increases expression of espC (34, 73). The EspC protein is an enterotoxin encoded within a second EPEC PAI; it causes disruption of the cytoskeleton and is translocated into the host cell cytosol by a TTSS-independent mechanism involving pinocytosis (84, 90, 125, 137), and translocation is enhanced by contact with the host cell (Fig. 1A). Since espC is not located within the LEE PAI, Ler is considered a global regulator of EPEC virulence.

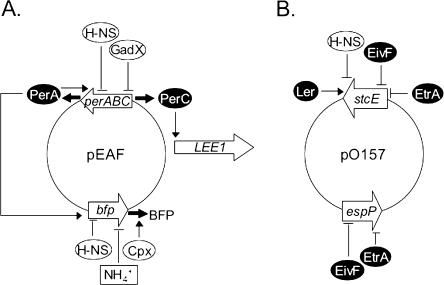

As with EPEC, Ler is a key regulator of EHEC virulence genes (Fig. 1B). Elliott et al. (34) demonstrated that EHEC strain 86-24 deleted for the gene encoding this protein did not form AE lesions on cultured human intestinal epithelial cells by fluorescent actin-staining assay and that EHEC ler can functionally substitute for EPEC ler. Additionally, in a rabbit model of infection (rabbit diarrheagenic E. coli), deletion of ler attenuated virulence (149). Ler regulates expression of the EHEC EspA, EspB, EspD, Tir, intimin, and EspG proteins targeted for secretion, and by lacZ fusions Ler regulates transcriptional activity of the EHEC LEE2, LEE3, and LEE5 operons (25, 34). The pO157 virulence plasmid-located stcE gene of EHEC is regulated by Ler (34, 70, 73), and thus, as in EPEC, this protein is a global regulator of EHEC virulence genes (Fig. 1B and 2B).

FIG. 2.

Virulence gene regulation in the EAF plasmid of EPEC (A) and the EHEC pO157 plasmid (B). Thin arrows represent positive regulatory signals, and thin blunt arrows represent negative signals. Solid arrows indicate expression of regulatory proteins. Horizontally acquired regulatory proteins appear in ovals with a black background. Regulation of bfp in response to NH4+ concentrations in EPEC is noted by box. The EtrA and EivF proteins of EHEC are encoded in a second cryptic TTSS, termed ETT2, of the Sakai 813 strain.

During infection of HEp-2 cells in culture, Ler expression is necessary only during the early stages of the EPEC infection process (71). By real-time PCR it was demonstrated that transcription of the EPEC LEE3, LEE4, and LEE5 operons increased over 3 h postinfection, while the expression of LEE1, carrying ler, decreased during the same period (71). The EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir proteins necessary for AE lesion formation were visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy at 5 h postinfection, indicating that Ler was not necessary for maintenance of these proteins once they were expressed.

Under certain conditions, Ler has been shown to repress transcription of the EPEC LEE1 operon (5). That study may indicate that the local concentration of Ler is important in proper regulation of LEE virulence genes. However, Ler autoregulation remains controversial. To further this point, a DNA microarray experiment to elucidate the Ler and H-NS regulons in EHEC showed that Ler altered the expression of ∼1,300 genes, but none of these genes were repressed by Ler (J. Smart and J. B. Kaper, personal communication).

Mechanism of Ler action.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that the mechanism of Ler action is to disrupt H-NS-dependent nucleoprotein complexes requiring both upstream and downstream H-NS-binding regions (9, 51, 109, 120, 135). In EPEC, Ler binds to the same regions upstream of the LEE2 and LEE5 promoters as does H-NS, and thus both of these regulatory proteins act directly on the LEE (9, 51, 120). This observation, combined with the dissociation constants (Kd) of H-NS and Ler being approximately 1 μM and 100 nM, respectively (135; A. M. Carmona and J. L. Mellies, unpublished data), suggests that Ler acts to relieve silencing by disrupting H-NS binding. Ler is not a general antagonist of H-NS, because Ler does not increase expression of the H-NS-regulated proU operon (34). Currently there is no evidence to suggest that Ler increases LEE transcription by direct interaction with RNA polymerase.

Regulation through Ler.

Several regulatory proteins indirectly influence EPEC and EHEC AE lesion formation via Ler. Fis and integration host factor (IHF) positively regulate the EPEC LEE1, Ler-encoding operon (37, 44) (Fig. 1A and B), and the observation that purified IHF protein did not bind to LEE2 regulatory DNA (37) supported earlier conclusions concerning the Ler regulatory cascade whereby Ler increases transcriptional activities of all major operons of the LEE except LEE1. BipA increases LEE transcription, most likely indirectly through activating expression of Ler (47) (Fig. 1A). BipA shares amino acid sequence similarity with eukaryotic ribosome-binding elongation factor G and possesses both GTPase and ATPase activities (36).

The EAF virulence plasmid-encoded regulators PerABC regulate AE lesion formation through Ler, as well as the LA phenotype (see below) (9, 82, 100). PerC directly activates transcription of LEE1 and then via Ler increases transcription of the LEE5 operon, encoding intimin. Intimin, encoded by the eae gene, is down-regulated upon contact with host epithelial cells (67), a process that involves the EAF plasmid and presumably PerC (Fig. 2A).

Through comprehensive mutagenesis of the LEE PAI of the mouse pathogen Citrobacter rodentium, the positive regulator GrlA, controlling expression of EspB and Tir, was identified (25). This regulatory protein was functionally equivalent in the three AE pathogens C. rodentium, EHEC, and EPEC (Fig. 1A and B). GrlA is predicted to act at the level of transcription upstream of Ler, and a subsequent study with C. rodentium indicated that Ler acts directly to control GrlA expression, part of a complex positive regulatory loop whereby optimal Ler expression depends on GrlA, thus controlling spatiotemporal transcription of the genes of the LEE (3). GrlA shares 37% and 23% identity to Sgh protein of Salmonella and CaiF of Enterobacteriaceae, respectively. Another LEE-encoded regulatory protein, GrlR, expressed from the same operon as GrlA, represses LEE1, LEE2, and LEE5 transcription (25, 74). This repressor was postulated to act upstream of Ler as well (Fig. 1A and B).

In EHEC, several regulatory systems are known to control the expression of Ler, including the RcsC-RcsD-RcsB phosphorelay system and the EHEC-specific GrvA protein (132) (Fig. 1B). Nakanishi et al. reported that induction of the stringent response increased transcriptional activity of the Ler-encoding LEE1 operon, requiring relA and spoT (88). This global regulatory response to starvation and entry into the stationary phase of growth (for a review, see reference 78), in the presence of elevated levels of ppGpp, enhanced expression and secretion of EspB and Tir and adherence to Caco-2 epithelial cells in culture through increased expression of Ler. The nucleoid-binding protein IHF positively regulates EHEC LEE gene expression through Ler (146), whereas Hha, implicated in the regulation of α-hemolysin (93), negatively regulates Ler expression (112) (Fig. 1B). Deletion of the gene hha in EHEC resulted in increased expression of Ler and adherence to HEp-2 epithelial cells in culture. The purified 8.5-kDa Hha protein bound to the LEE1 regulatory DNA, demonstrating that this regulation is direct (111). Research thus indicates that regulation of the LEE PAIs of EPEC and EHEC is exceedingly complex, involving multiple environmental signals and multiple regulatory proteins, whereby Ler serves as the central receiver of regulatory input, ultimately controlling the TTSS and AE phenotype (Fig. 1A and B).

Other regulators of the LEE.

Tatsuno et al. (129) identified two novel regulators of EHEC adherence, YhiF and YhiE, controlling secretion of EspB, EspD, and Tir (Fig. 1B). YhiF and YhiE share amino acid identity (23%) and are members of the LuxR family of transcriptional regulators, which include portions of two-component regulatory systems in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, Pseudomonas putida, and the gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus. These proteins exert transcriptional control on the LEE2 and LEE4 operons but not on ler (Fig. 1B). Insertional inactivation of the yhiE locus caused increased shedding of the O157:H7 Sakai strain in a mouse model of infection, implicating this gene in the regulation of EHEC colonization.

Additional regulators of the LEE of EHEC are found in a second, cryptic TTSS of the Sakai 813 strain (147). Deletion of either of the regulatory genes etrA or eivF from this second, nonfunctional TTSS leads to increased secretion of EspA, EspB, Tir, and the pO157 plasmid-encoded StcE and EspP proteins by immunoblot analysis and adherence to Int-407 cultured epithelial cells (Fig. 1B and 2B). Overexpression of EtrA or EivF repressed secretion in a high-secreting O26:H− strain, emphasizing the role of these proteins in repression of LEE gene expression. Reporter gene fusions of the five major LEE operons suggested that EtrA and EivF exerted their effect at the level of transcription. This study is of special interest because it illustrates the concept that the functionality of regulatory genes may outlast the functionality of a decayed gene cluster in which they are located and that they may regulate distally located genes, a phenomenon dubbed the “Cheshire cat effect” after the disappearing cat in Alice in Wonderland. This may be a particularly apt metaphor, since it is increasingly apparent that proper regulation of attachment factors is essential for colonization of bacterial pathogens, including EHEC, and one sees the Cheshire cat's teeth (i.e., the regulators) when he disappears in this classic children's tale.

Quorum sensing.

Cell-to-cell communication, or quorum-sensing, regulation of EPEC and EHEC LEE PAIs was first reported by Sperandio et al. (121) and mostly occurs through the coordinate regulation of Ler (Fig. 3) (122). Subsequent intense research, beyond this initial discovery, indicates that quorum-sensing regulation of the AE phenotype and flagellar motility is remarkably complex.

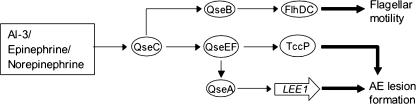

FIG. 3.

Quorum-sensing signaling of flagellar motility and AE lesion formation in EPEC and EHEC. The cryptic phage-encoded TccP protein is necessary for AE lesion formation in EHEC. See the text for details.

Three main quorum-sensing systems have been described for gram-negative bacteria (61, 144). In the LuxIR system, initially described for Vibrio, the autoinducer synthase LuxI produces an acylated homoserine lactone (HSL) molecule that binds to the LuxR regulator, which then modulates gene expression. In the second LuxS/AI-2 system, also found in gram-positive bacteria, the LuxS autoinducer synthase produces a furanone from a precursor derived from the metabolism of S-adenosyl methionine. The most intriguing discovery to date concerning cell-to-cell signaling in EHEC bacteria is a luxS-independent AI-3-signaling molecule (141), which cross talks with the mammalian hormone epinephrine and activates LEE and flagellar genes (118, 123). The AI-2 autoinducer is a furanosyl borate diester that depends on LuxS for biosynthesis (13, 127), but it is now known that AI-2 does not activate expression of EHEC virulence genes (123, 140, 141).

Via the AI-3 signal perceived through the QseEF two-component system (see below), the quorum-sensing regulator QseA, a member of the LysR family of proteins, directly activates transcription of the LEE1 operon (113) (Fig. 3). Flagellar motility is regulated by the QseB/QseC two-component quorum-sensing regulatory proteins, a response regulator and sensor kinase, respectively (16, 17, 124). QseBC controls flagellum production by activating transcription of the flhDC master regulators and motA, and this regulation involves the class 2 flagellar gene fliA, encoding the sigma factor σ28. QseBC is subject to autoregulation, and identically with function at flhDC, QseB activates qseBC transcription by binding to high- and low-affinity sites upstream of a QseBC-responsive promoter (16).

An additional two-component system controlling the EHEC AE phenotype has been recently described. The QseEF proteins are a sensor kinase and response regulator, respectively, and are transcribed from a single operon (102). QseF activates transcription of the EspFu effector protein secreted into the host cell by the TTSS, and a qseF deletion mutant fails to form AE lesions. The QseEF system is activated by epinephrine through the QseC sensor kinase (Fig. 3). The precise mechanism of the sensor kinase/response regulator control of quorum-sensing signaling in EHEC continues to be under intense investigation.

Activation of LEE1 and flhDC transcription can be demonstrated by providing exogenous, partially purified AI-3 or by the addition of epinephrine or norepinephrine (15). The bacterial AI-3 molecule is <1 kDa and is methanol soluble, consistent with its being similar to epinephrine, but the exact identity is yet to be established. Epinephrine is not produced by HeLa epithelial cells in culture but rather is found in the fetal bovine serum added to the culture medium. The AI-3-dependent signaling can be blocked by the addition of α- or β-adrenergic antagonists. The QseC sensor kinase responds directly to the AI-3/epinephrine and norepinephrine signal, as a qseC mutant is blind to both AI-3 and epinephrine, and QseC has been shown to bind to norepinephrine in vitro (15, 124). The AI-3/epinephrine/norepinephrine quorum-sensing regulon is thus an interkingdom communication system controlling the AE phenotype and flagellar motility. This regulon is thought to be of particular importance for EHEC, as the site of infection is the large bowel, which contains dense populations of commensal flora.

Though no HSL signaling molecules exist in E. coli, the LuxR homolog SdiA directly represses the EHEC EspD- and intimin-encoding operons LEE4 and LEE5, respectively (59) (Fig. 1B). It has been hypothesized that the biological function of SdiA, which activates transcription of the ftsQAZ operon, encoding proteins essential for cell division (2, 143), is to detect the presence of other species of bacteria that produce HSL signaling molecules (145).

SOS control of the EPEC LEE.

We have recently demonstrated that genes of the EPEC LEE are regulated by the SOS response (83) (Fig. 1A). In K-12-derived strains, transcriptional activity from LEE2-lacZ and LEE3-lacZ fusions increased in the presence of the DNA-damaging agent mitomycin C, and this activity was both RecA dependent and LexA dependent. In wild-type EPEC, transcriptional activity of the LEE2 and LEE3 operons was also increased in the presence of mitomycin C, and protein secretion was reduced in the presence of the lexA1 allele, encoding an uncleavable LexA protein, particularly in the absence of the Ler regulator. Intriguingly, we also observed increased transcription of the non-LEE, phage-encoded effector nleA in the presence of mytomicin C. LexA protein, identical in the K-12 MG1655 and EPEC E2348/69 strains, bound specifically to a predicted SOS box located within the overlapping LEE2 and LEE3 promoters. Thus, the SOS response, a regulon fundamental to bacterial survival and evolution, controls expression of genes encoding components of the TTSS and a cryptic phage-encoded effector of EPEC.

Regulation of the EPEC LA phenotype.

Similar to observations on the regulation of AE lesion formation, the LA phenotype is influenced by environmental conditions, carbon source, and phase of growth. EPEC showed increased adherence to HEp-2 human intestinal epithelial cells in culture in DMEM as opposed to rich media (42, 101, 136, 138), adhering as microcolonies effectively in the presence of glucose but not in the presence of galactose (136). Expression of the BFP occurs maximally at 37°C during the exponential phase of growth (101). Transcription of bfpA is subject to ammonium ion regulation; the cation NH4+ represses transcription of this gene (8, 9, 79, 101) (Fig. 2A). Though NH4+ exists within the gut, in higher concentrations in the distal versus the proximal small intestine, the significance of this finding in terms of EPEC pathogenesis remains to be determined. BFP expression is also linked to the Cpx two-component phosphorelay system. The sensor kinase CpxA and response regulator CpxR respond to potentially lethal insults to the cell envelope. The BFP is not assembled unless the Cpx system is activated (92), and this regulation is most likely posttranscriptional.

The PerA protein, encoded within the perABC operon adjacent to bfp on the EAF virulence plasmid, regulates bfp transcription (134) (Fig. 2A). Several studies have indicated that PerA is required for expression of the BFP, and indeed mutation in perA renders EPEC unable to display the LA phenotype (9, 79, 134). (PerA has also been called BfpT [134].) PerA shows amino acid sequence similarity to the AraC family of transcriptional regulators, and it is most closely related to the VirF protein of Shigella flexneri, a primary activator of virulence genes in this pathogen (30). PerA is also similar to the Rns transcriptional activator in ETEC (87). Transcriptional regulation of bfp by PerA is direct, as this protein was shown to bind to DNA regulatory sequences upstream of bfpA in vitro (100, 134) and cis-acting sequences between positions −85 and −46 were required for activation (8). The perA gene is subject to autoregulation, and binding regions upstream of the perA and bfp promoters share significant sequence similarity (55, 85).

The EAF plasmid-located perABC locus is itself subject to higher-order regulation. GadX, an activator of glutamate decarboxylase genes involved in acid tolerance, represses the expression of perABC (114) (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this observation, because PerC regulates expression of Ler, a mutation in gadX resulted in increased translocation of Tir into host epithelial cells. GadX is a member of the XylR/AraC family of transcriptional regulators, and its expression is increased in DMEM culture medium and under acidic conditions (pH 5.5). GadX was deemed a transcriptional regulator based on gel shift assays showing that this protein binds directly to perABC and gadA and gadB regulatory sequences, and it may function to properly regulate acid tolerance and virulence gene expression in response to environmental cues within the gastrointestinal tract.

Per-like molecules in EHEC.

The question of whether Per-like molecules exist in EHEC was addressed by two independent research groups (58, 99). Iyoda and Watanabe (58) screened a genomic library of the EHEC O157:H7 Sakai strain for genes that controlled expression of LEE fusions. They identified a DNA fragment containing a gene with similarity to perC of EPEC. Upon closer inspection of the genomic DNA sequences, they identified five perC-like sequences but no sequences with similarity to either perA or perB. Deletions in either perC1-1 (also termed pchA) or perC1-2 (also termed pchB), or double deletions in perC1-1 and perC1-2 or in perC1-1 and perC1-3 (also termed pchC), reduced the expression of EspA, EspB, and EspD proteins and adherence to HEp-2 cells in culture (Fig. 1B). This group postulated that multiple perC loci were necessary for full expression of the LEE and found that these loci exerted their effect through transcriptional activation of the LEE1 operon encoding Ler (Fig. 1A and 2A).

PerC-like molecules exist not only in the E. coli O157:H7 strain Sakai (PerC1-1, PerC1-2, PerC1-3, PerC2, and PerC3), but also in the O157:H7 strain EDL933 (PerC1, PerC2, PerC3-1, and PerC3-2), in uropathogenic E. coli (PerC2, PerC3, and YfdN), in the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ST64B phage (YfdN), in the S. flexneri SfV phage (YfdN), and in the E. coli laboratory strain MG1655 (YfdN) (99). Many of the genes encoding the PerC-like molecules are found with lambdoid phage. Porter et al. (99) found that the PerC1, but not the PerC2, proteins of EHEC strains could activate expression of LEE1 from both organisms, though in vitro assays could not demonstrate binding of purified PerC protein to LEE1 regulatory fragments. They hypothesized that PerC molecules may bind in the presence of IHF, which is also a positive regulator of LEE1, and perhaps other unidentified proteins to activate transcription. The PerC-responsive promoters of EHEC and EPEC are located similarly in these bacteria, approximately 170 bp upstream of the start codon of ler of LEE1.

Posttranscriptional regulation.

Control of secretion of translocator molecules, e.g., EspB, and effectors, e.g., Tir, is complex, involving posttranscriptional and posttranslational regulation. Heterogeneous secretion of EspD protein in human and bovine O157:H7 isolates led investigators to study the underlying mechanism regulating this observation (107). They found that strains possessing EspA translocons, visualized by immunofluorescence, correlated with high levels of EspD secretion and that the observed variations in secretion were not controlled at the level of transcription, as demonstrated by reporter gene fusions. By Northern analysis, secretion of translocon proteins was inversely related to espADB mRNA transcript levels. Evidence suggested that sepL, espA, espD, and espB are transcribed as a single polycistronic operon but that mRNA processing must occur, separating the transcript into two fragments, an approximately 1.2-kb sepL-containing transcript and a 2.8-kb espADB transcript. These investigators clearly established that posttranscriptional regulation is involved in EspA filament or translocon formation, though the exact mechanism of control remains to be determined. They postulate that the inability to detect the espADB transcripts in the high-secretor strains may be explained by engagement of the molecule in the type III apparatus prior to secretion, a coupling of translation and secretion as proposed for flagellum assembly in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (62).

One issue that has remained controversial in the study of TTSSs is whether contact-dependent secretion occurs (20). Certainly environmental signals can cue secretion; Ebel et al. (32) established that temperature and medium conditions affect secretion of EHEC polypeptides. Calcium-deficient conditions signal secretion of effector Yops of Yersinia spp., and secretion of Ipa effector proteins of S. flexneri can be triggered by the dye Congo red (96), but whether these environmental conditions and/or chemical cues actually relate to contact-dependent secretion remains to be determined. Some studies have indicated that a rapid increase in EHEC LEE gene expression occurs upon contact with host epithelial cells; transcriptional activity from an espADB-lacZ fusion increased upon contact with HeLa cells (4), and tir-egfp and map-egfp fusion activity increased upon contact with bovine intestinal epithelial cells (106). Beltrametti et al. (4) also demonstrated that the addition of Ca2+ or Mn2+, but not Mg2+, increased the expression of the espADB-lacZ fusion.

An elegant study by Deng et al. (24) revealed that SepD and SepL, encoded by the LEE2 and LEE4 operons, respectively, constitute a molecular switch controlling secretion of translocators and effector molecules, and they began to clarify the role of calcium in these processes. Beginning with C. rodentium, but expanding their studies to EHEC and EPEC, they found that low-calcium conditions inhibit the secretion of translocators, such as EspA, EspD, and EspB, but enhance the secretion of effectors, such as Tir and NleA. This phenotype was similar to that observed for sepD and sepL nonpolar deletion mutants. SepD and SepL proteins interact with each other and are localized to the inner membrane. These authors proposed a model whereby a high calcium level, about 2.5 mM in the mammalian extracellular fluid (19), stimulates the secretion of translocator proteins necessary for assembly of the translocon, and then, once connected to the host cell, the low-calcium environment (100 to 300 nM, as most calcium is sequestered in the endoplasmic reticulum) triggers secretion of the effector proteins. Thus, SepD and SepL were termed “gatekeepers,” controlling the switch releasing effector proteins into the host cell cytoplasm (24). The exact mechanism of how the calcium signal is perceived from the host cell cytoplasm and sensed by the bacterium remains to be determined.

Phage control of virulence in EHEC.

Several studies have demonstrated that production of EHEC Stx can be modulated by antibiotics (48, 66, 142, 148) and that Stx production is linked to the Stx phage growth cycle (91, 139). The Shiga toxins exist in two subgroups, Stx1 and Stx2, and are encoded within prophages (97), though to date only the prophage BP-933W encoding Stx2 has been shown to produce infectious phage particles. Stx1 expression is subject to regulation by the iron-responsive Fur repressor (1). Expression of Stx2 is under transcriptional control of the Q-dependent late phage promoter, which is subject to quorum-sensing signaling (123, 139).

Herold et al. (52) used a DNA microarray approach to monitor changes in transcriptional activity in the presence of low levels of the DNA gyrase inhibitor norfloxacin, which induces DNA damage and the SOS response. Phage titer and Stx2 production dramatically increased approximately 2 h after the addition of the antibiotic. Of the 118 spots showing increased expression in the presence of the antibiotic, 85 were phage borne; 52 were from the Stx phages BP-933W and CP-933V. The most strongly induced genes were found within the BP-933W phage; stxA2 was induced 158-fold. Regulation of the stx2 and recA genes, indicating induction of the SOS response, was confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR. Other induced genes included those for putative phage integrases not found in prophages; some stress-induced proteins, including the heat shock protein IbpB; and DNA damage-inducible proteins associated with the SOS response, including DinB.

There is an intimate connection between DNA damage and phage induction, and hence in the case of EHEC the release of the Shiga toxin, which is important in causing serious disease. To add insult to injury, Gamage et al. (38) demonstrated that Stx phage conversion of intestinal commensal E. coli led to increased production of the Stx2 toxin in a mouse model and that ciprofloxacin, also a DNA gyrase inhibitor and a commonly prescribed antibiotic in the United States, led to lysis of phage-infected host E. coli and release of the toxin. There was indeed a 40-fold increase in Stx2 production when the susceptible commensal E. coli was infected with the 933W phage, indicating that the Shiga toxin phages regulate amplification of the toxin upon phage induction, which is known to occur in the presence of DNA-damaging agents. In addition to simply up-regulating virulence genes, the error-prone replication machinery activated by the SOS response may provide the genetic variability necessary for generation and selection of spontaneously resistant bacterial strains. It seems likely that the treatment of E. coli infections by antibiotics may have unintended negative consequences; the prevailing thought that for the treatment of EHEC infections antibiotics are contraindicated is certainly consistent with this idea.

COMMON THEMES

Through elucidation of specific signaling events, perception of environmental cues, and identification of regulatory proteins controlling expression of virulence genes in EPEC and EHEC bacteria, a picture of the global regulation of virulence genes in response to the pathogen-host interaction emerges. H-NS plays an important role in the regulation of horizontally transferred, virulence factor-encoding DNA, an idea that has reappeared in the literature (28). Because foreign DNA in gram-negative bacteria tends to have a low G+C content (i.e., a high A+T content) in comparison with the recipient's genome and since H-NS preferentially binds to AT-rich sequences, many researchers have hypothesized that H-NS may endogenously silence horizontally transferred DNA elements, which when expressed inappropriately might be deleterious to the bacterium. In Salmonella, selective silencing of horizontally acquired, low-G+C-content DNA by the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS, enables the bacterium to avoid inappropriate expression of foreign DNA (76, 89). Specifically, in EPEC H-NS silences expression of the TTSS, BFP, and PerABC, and in EHEC it silences expression of StcE, all of which are encoded on horizontally transferred genetic elements. Thus, H-NS plays a critical role in disease-causing E. coli and Salmonella spp., as well as in the evolution of molecular pathogenesis in these organisms.

Subsequently, EPEC and EHEC bacteria must activate expression of H-NS-silenced virulence genes, such as the LEE. Regulatory proteins that counteract H-NS silencing of the LEE may be acquired along with the horizontally transferred DNA (Table 1) or may exist endogenously in the recipient, located on either the chromosome or a plasmid (Table 2). Several mobile DNA elements encode proteins that either interact with or inactivate the function of H-NS (23, 33, 75). For example, the protein encoded by gene 5.5 of phage T7 disrupts H-NS function, resulting in expression of both host and viral genes (23, 33, 75). Consistent with this idea, the horizontally acquired TTSSs of EPEC and EHEC bacteria are regulated by the LEE-encoded global regulator Ler, disrupting the silencing activity of endogenous H-NS (predicted also to occur in EHEC) in response to host-associated environmental cues. Virulence genes that are repressed by a non-H-NS protein(s) and derepressed by Ler may also exist, but a mechanism describing this type of regulation has not been reported.

TABLE 1.

Horizontally acquired regulators of the LEE

| Regulator | Pathotype | Location | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EivF | EHEC | ETT2a | 147 |

| EtrA | EHEC | ETT2 | 147 |

| GrlRA | EPEC/EHEC | LEE | 3, 25 |

| GrvA | EHEC | EHEC prophage | 132 |

| Ler | EPEC/EHEC | LEE | 34, 82 |

| PerC | EPEC | EAF plasmid | 9, 45, 55, 82, 100 |

| PchABC | EHEC | EHEC prophage | 58, 99 |

ETTS is a second cryptic TTSS of the O157:H7 strain Sakai 813.

TABLE 2.

Endogenous regulators of the LEE

Investigation of virulence gene regulation in EPEC, EHEC, and other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family has furthered our understanding of the mechanism of H-NS-mediated gene silencing. It has been known for some time that H-NS can bind in regions that flank promoters and that H-NS can facilitate DNA looping (for recent reviews on H-NS, see references 28, 29, 104, and 131). For example, H-NS binds over extended positions both upstream and downstream of the proU and bgl promoters of E. coli K-12 and the virF promoter of enteroinvasive E. coli (11, 35, 77). Similarly, H-NS-dependent repressing DNA sequences exist both upstream and downstream of the Ler-induced EPEC LEE2 and LEE5 promoters, and Ler binds to the same region upstream of the LEE2 and LEE5 promoters to which H-NS binds (9, 51, 120; K. R. Haack and J. L. Mellies, unpublished data). DNA looping by H-NS has been demonstrated for the ure operon of the urinary tract pathogen Proteus mirabilis, which is positively regulated by UreR, an AraC-like molecule (98). A unifying mechanism emerges from these data, suggesting that the unrelated AraC-like regulators and H-NS-like protein Ler increase transcription by disruption of H-NS-dependent nucleoprotein complexes requiring H-NS binding that flanks promoter sequences. This mechanism is most likely conserved in H-NS control of virulence gene expression in the Enterobacteriaceae.

In addition to silencing and antisilencing by the global regulators H-NS and Ler, respectively, three global regulatory systems, the stringent response (ppGpp), quorum sensing, and the SOS response, regulate expression of the TTSS. Why are there so many global inputs, environmental signals, and regulatory proteins controlling expression of the TTSSs of these pathogens? The answer may simply be that multiple regulatory inputs ensure a robust response to the host environment and that evolution occurs randomly, adding intricate layers of regulation, feedback loops, and seemingly contradictory inputs of regulation of the TTSS to establish and maintain this robustness.

A resurgence in studying the role of bacteriophages in the pathogenesis of EPEC and EHEC bacteria has occurred. In EHEC, DNA damage causes Stx2-encoding 933W λ-like phage induction, which is essential for biosynthesis and release of the Stx2 toxin. Indeed, Stx2 production is enhanced by the presence of DNA-damaging antibiotics (130, 148). In EPEC the SOS response regulates transcription of two operons within the LEE and a cryptic prophage gene encoding the NleA effector. Thus, along with controlling the response to DNA damage, repair of stalled replication forks, and the expression of error-prone polymerases leading to increased frequency of mutation, the SOS response regulates expression of important virulence determinants from both of these E. coli pathotypes. The observation that EPEC and EHEC virulence is, at least in part, regulated by the SOS response indicates that these pathogens experience stress associated with DNA damage in the environment of the host. A number of effector proteins, translocated into host cells by the TTSS of EPEC and EHEC, are encoded within cryptic prophages (39, 133), and whether these molecules are under control of the SOS response, Ler, GrlRA (25), or perhaps other regulators remains unknown.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The study of virulence gene regulation is greatly assisting our understanding of EPEC and EHEC pathogenesis. The shared global regulator Ler receives environmental signals and regulatory input from multiple proteins acting on the LEE1 operon and then proceeds to increase transcriptional activity of the genes necessary for forming AE lesions. Thus, Ler lies at the heart of the global regulatory network controlling the AE phenotype for both pathotypes. Quorum-sensing signaling contributes to EHEC colonization of the large intestine, perceiving the high density of bacteria in the human intestinal tract versus the relatively low bacterial density in the proximal small intestine, the site of EPEC infection. Studies elucidating the EHEC quorum-sensing network illustrate important regulatory differences between EPEC and EHEC. Concerning type III secretion, we are beginning to see a distinction in the expression of the apparatus components and the actual secretion or translocation of effector molecules as separable, differentially regulated events. However, many outstanding questions remain. Beyond quorum sensing, do regulatory phenomena play a further role in the site of EPEC and EHEC infection, or tissue tropism? Does regulation contribute to their vastly different infectious doses? How are the cryptic prophage-encoded effector molecules and other effector proteins encoded outside the LEE PAI regulated in order to facilitate coordinated delivery into host cells by the TTSS?

In addition to elucidating host-microbe interactions, studies dissecting regulatory circuitry offer opportunities to devise new effective therapies and protective measures against EPEC, EHEC, and related pathogens. For example, Gauthier et al. (41) identified a class of compounds for potential therapeutic use that inhibited transcriptional activity of EPEC LEE operons, which they hypothesized to be occurring through repression of ler. Hung et al. (54) identified a compound, virstatin, that inhibited transcription of ToxT, a key regulator of cholera toxin and the toxin-coregulated pilus in Vibrio cholerae. Administration of virstatin prevented intestinal colonization of V. cholerae in the infant mouse model. Finally, Cirz et al. (14) proposed targeting of the SOS regulon of E. coli for chemical therapies to minimize the evolution of antibiotic resistance, because they found that the development of resistance to the antibiotics ciprofloxacin and rifampin required a functional SOS response. With the growing problem of pan-resistant bacteria, researchers must devise novel means to thwart infectious disease, to extend our therapeutic arsenal beyond traditional antibiotics. The study and targeting of bacterial regulatory circuitry will play an increasingly important role in this endeavor.

Acknowledgments

Research in the laboratory of J.L.M. is supported by an NIH AREA grant (R15 AI047802-02) and by HHMI and Merck/AAAS grants awarded to the Biology and Chemistry Departments of Reed College.

Editor: J. B. Kaper

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aertsen, A., R. Van Houdt, and C. W. Michiels. 2005. Construction and use of an stx1 transcriptional fusion to gfp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldea, M., T. Garrido, J. Pla, and M. Vicente. 1990. Division genes in Escherichia coli are expressed coordinately to cell septum requirements by gearbox promoters. EMBO J. 9:3787-3794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barba, J., V. H. Bustamante, M. A. Flores-Valdez, W. Deng, B. B. Finlay, and J. L. Puente. 2005. A positive regulatory loop controls expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded regulators Ler and GrlA. J. Bacteriol. 187:7918-7930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beltrametti, F., A. U. Kresse, and C. A. Guzmâan. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the esp genes of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3409-3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berdichevsky, T., D. Friedberg, C. Nadler, A. Rokney, A. Oppenheim, and I. Rosenshine. 2005. Ler is a negative autoregulator of the LEE1 operon in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:349-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieber, D., S. W. Ramer, C. Y. Wu, W. J. Murray, T. Tobe, R. Fernandez, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1998. Type IV pili, transient bacterial aggregates, and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 280:2114-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunder, W., H. Schmidt, and H. Karch. 1997. EspP, a novel extracellular serine protease of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 cleaves human coagulation factor V. Mol. Microbiol. 24:767-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustamante, V. H., E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 1998. Analysis of cis-acting elements required for bfpA expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180:3013-3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bustamante, V. H., F. J. Santana, E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 2001. Transcriptional regulation of type III secretion genes in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: Ler antagonizes H-NS-dependent repression. Mol. Microbiol. 39:664-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campellone, K. G., D. Robbins, and J. M. Leong. 2004. EspFU is a translocated EHEC effector that interacts with Tir and N-WASP and promotes Nck-independent actin assembly. Dev. Cell. 7:217-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caramel, A., and K. Schnetz. 1998. Lac and lambda repressors relieve silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter. Activation by alteration of a repressing nucleoprotein complex. J. Mol. Biol. 284:875-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caron, E., V. F. Crepin, N. Simpson, S. Knutton, J. Garmendia, and G. Frankel. 2006. Subversion of actin dynamics by EPEC and EHEC. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:40-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, X., S. Schauder, N. Potier, A. Van Dorsselaer, I. Pelczer, B. L. Bassler, and F. M. Hughson. 2002. Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature 415:545-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cirz, R. T., J. K. Chin, D. R. Andes, V. de Crecy-Lagard, W. A. Craig, and F. E. Romesberg. 2005. Inhibition of mutation and combating the evolution of antibiotic resistance. PLoS Biol. 3:e176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke, M. B., D. T. Hughes, C. Zhu, E. C. Boedeker, and V. Sperandio. 2006. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:10420-10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke, M. B., and V. Sperandio. 2005. Transcriptional autoregulation by quorum sensing Escherichia coli regulators B and C (QseBC) in enterohaemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). Mol. Microbiol. 58:441-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke, M. B., and V. Sperandio. 2005. Transcriptional regulation of flhDC by QseBC and sigma (FliA) in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1734-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarke, S. C., R. D. Haigh, P. P. Freestone, and P. H. Williams. 2003. Virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, a global pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:365-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornelis, G. R. 1998. The Yersinia deadly kiss. J. Bacteriol. 180:5495-5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornelis, G. R. 2002. The Yersinia Ysc-Yop ‘type III’ weaponry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3:742-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dame, R. T., M. S. Luijsterburg, E. Krin, P. N. Bertin, R. Wagner, and G. J. Wuite. 2005. DNA bridging: a property shared among H-NS-like proteins. J. Bacteriol. 187:1845-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dame, R. T., C. Wyman, and N. Goosen. 2000. H-NS mediated compaction of DNA visualised by atomic force microscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:3504-3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deighan, P., C. Beloin, and C. J. Dorman. 2003. Three-way interactions among the Sfh, StpA and H-NS nucleoid-structuring proteins of Shigella flexneri 2a strain 2457T. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1401-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng, W., Y. Li, P. R. Hardwidge, E. A. Frey, R. A. Pfuetzner, S. Lee, S. Gruenheid, N. C. Strynakda, J. L. Puente, and B. B. Finlay. 2005. Regulation of type III secretion hierarchy of translocators and effectors in attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 73:2135-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng, W., J. L. Puente, S. Gruenheid, Y. Li, B. A. Vallance, A. Vázquez, J. Barba, J. A. Ibarra, P. O'Donnell, P. Metalnikov, K. Ashman, S. Lee, D. Goode, T. Pawson, and B. B. Finlay. 2004. Dissecting virulence: systematic and functional analyses of a pathogenicity island. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnenberg, M. S., J. A. Girón, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 1992. A plasmid-encoded type IV fimbrial gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli associated with localized adherence. Mol. Microbiol. 6:3427-3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donnenberg, M. S., C. O. Tacket, S. P. James, G. Losonsky, J. P. Nataro, S. S. Wasserman, J. B. Kaper, and M. M. Levine. 1993. Role of the eaeA gene in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection. J. Clin. Investig. 92:1412-1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorman, C. J. 2004. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:391-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dorman, C. J., and P. Deighan. 2003. Regulation of gene expression by histone-like proteins in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13:179-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorman, C. J., and M. E. Porter. 1998. The Shigella virulence gene regulatory cascade: a paradigm of bacterial gene control mechanisms. Mol. Microbiol. 29:677-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dziva, F., P. M. van Diemen, M. P. Stevens, A. J. Smith, and T. S. Wallis. 2004. Identification of Escherichia coli O157:H7 genes influencing colonization of the bovine gastrointestinal tract using signature-tagged mutagenesis. Microbiology 150:3631-3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebel, F., C. Deibel, A. U. Kresse, C. A. Guzmán, and T. Chakraborty. 1996. Temperature- and medium-dependent secretion of proteins by Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 64:4472-4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott, S. J., S. W. Hutcheson, M. S. Dubois, J. L. Mellies, L. A. Wainwright, M. Batchelor, G. Frankel, S. Knutton, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. Identification of CesT, a chaperone for the type III secretion of Tir in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1176-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elliott, S. J., V. Sperandio, J. A. Girón, S. Shin, J. L. Mellies, L. Wainwright, S. W. Hutcheson, T. K. McDaniel, and J. B. Kaper. 2000. The locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator controls expression of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded virulence factors in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 68:6115-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falconi, M., B. Colonna, G. Prosseda, G. Micheli, and C. O. Gualerzi. 1998. Thermoregulation of Shigella and Escherichia coli EIEC pathogenicity. A temperature-dependent structural transition of DNA modulates accessibility of virF promoter to transcriptional repressor H-NS. EMBO J. 17:7033-7043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farris, M., A. Grant, T. B. Richardson, and C. D. O'Connor. 1998. BipA: a tyrosine-phosphorylated GTPase that mediates interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 28:265-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedberg, D., T. Umanski, Y. Fang, and I. Rosenshine. 1999. Hierarchy in the expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement genes of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 34:941-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamage, S. D., J. E. Strasser, C. L. Chalk, and A. A. Weiss. 2003. Nonpathogenic Escherichia coli can contribute to the production of Shiga toxin. Infect. Immun. 71:3107-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garmendia, J., G. Frankel, and V. F. Crepin. 2005. Enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infections: translocation, translocation, translocation. Infect. Immun. 73:2573-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garmendia, J., A. D. Phillips, M. F. Carlier, Y. Chong, S. Schuller, O. Marches, S. Dahan, E. Oswald, R. K. Shaw, S. Knutton, and G. Frankel. 2004. TccP is an enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 type III effector protein that couples Tir to the actin-cytoskeleton. Cell. Microbiol. 6:1167-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gauthier, A., M. L. Robertson, M. Lowden, J. A. Ibarra, J. L. Puente, and B. B. Finlay. 2005. Transcriptional inhibitor of virulence factors in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4101-4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Girón, J. A., A. S. Ho, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1991. An inducible bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 254:710-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Girón, J. A., A. G. Torres, E. Freer, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. The flagella of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli mediate adherence to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 44:361-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldberg, M. D., M. Johnson, J. C. Hinton, and P. H. Williams. 2001. Role of the nucleoid-associated protein Fis in the regulation of virulence properties of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 41:549-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gómez-Duarte, O. G., and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A plasmid-encoded regulatory region activates chromosomal eaeA expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 63:1767-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gómez-Duarte, O. G., A. Ruiz-Tagle, D. C. Gómez, G. I. Viboud, K. G. Jarvis, J. B. Kaper, and J. A. Girón. 1999. Identification of lngA, the structural gene of longus type IV pilus of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 145:1809-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grant, A. J., M. Farris, P. Alefounder, P. H. Williams, M. J. Woodward, and C. D. O'Connor. 2003. Co-ordination of pathogenicity island expression by the BipA GTPase in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC). Mol. Microbiol. 48:507-521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grif, K., M. P. Dierich, H. Karch, and F. Allerberger. 1998. Strain-specific differences in the amount of Shiga toxin released from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 following exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:761-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffin, M. G., and P. B. Miner, Jr. 1995. Conventional drug therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 24:509-521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grys, T. E., M. B. Siegel, W. W. Lathem, and R. A. Welch. 2005. The StcE protease contributes to intimate adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to host cells. Infect. Immun. 73:1295-1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haack, K. R., C. L. Robinson, K. J. Miller, J. W. Fowlkes, and J. L. Mellies. 2003. Interaction of Ler at the LEE5 (tir) operon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 71:384-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herold, S., J. Siebert, A. Huber, and H. Schmidt. 2005. Global expression of prophage genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 in response to norfloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:931-944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hicks, S., G. Frankel, J. B. Kaper, G. Dougan, and A. D. Phillips. 1998. Role of intimin and bundle-forming pili in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion to pediatric intestinal tissue in vitro. Infect. Immun. 66:1570-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hung, D. T., E. A. Shakhnovich, E. Pierson, and J. J. Mekalanos. 2005. Small-molecule inhibitor of Vibrio cholerae virulence and intestinal colonization. Science 310:670-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ibarra, J. A., M. I. Villalba, and J. L. Puente. 2003. Identification of the DNA binding sites of PerA, the transcriptional activator of the bfp and per operons in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:2835-2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ide, T., S. Laarmann, L. Greune, H. Schillers, H. Oberleithner, and M. A. Schmidt. 2001. Characterization of translocation pores inserted into plasma membranes by type III-secreted Esp proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 3:669-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ide, T., S. Michgehl, S. Knappstein, G. Heusipp, and M. A. Schmidt. 2003. Differential modulation by Ca2+ of type III secretion of diffusely adhering enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 71:1725-1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iyoda, S., and H. Watanabe. 2004. Positive effects of multiple pch genes on expression of the locus of enterocyte effacement genes and adherence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to HEp-2 cells. Microbiology 150:2357-2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanamaru, K., I. Tatsuno, T. Tobe, and C. Sasakawa. 2000. SdiA, an Escherichia coli homologue of quorum-sensing regulators, controls the expression of virulence factors in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 38:805-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaper, J. B., J. P. Nataro, and H. L. Mobley. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaper, J. B., and V. Sperandio. 2005. Bacterial cell-to-cell signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 73:3197-3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karlinsey, J. E., J. Lonner, K. L. Brown, and K. T. Hughes. 2000. Translation/secretion coupling by type III secretion systems. Cell 102:487-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kenny, B. 2002. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC)—a crafty subversive little bug. Microbiology 148:1967-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kenny, B., A. Abe, M. Stein, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli protein secretion is induced in response to conditions similar to those in the gastrointestinal tract. Infect. Immun. 65:2606-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kenny, B., and B. B. Finlay. 1995. Protein secretion by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is essential for transducing signals to epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7991-7995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kimmitt, P. T., C. R. Harwood, and M. R. Barer. 2000. Toxin gene expression by shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: the role of antibiotics and the bacterial SOS response. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:458-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knutton, S., J. Adu-Bobie, C. Bain, A. D. Phillips, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 1997. Down regulation of intimin expression during attaching and effacing enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adhesion. Infect. Immun. 65:1644-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knutton, S., I. Rosenshine, M. J. Pallen, I. Nisan, B. C. Neves, C. Bain, C. Wolff, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 1998. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 17:2166-2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.La Ragione, R. M., A. Best, K. Sprigings, E. Liebana, G. R. Woodward, A. R. Sayers, and M. J. Woodward. 2005. Variable and strain dependent colonisation of chickens by Escherichia coli O157. Vet. Microbiol. 107:103-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lathem, W. W., T. E. Grys, S. E. Witowski, A. G. Torres, J. B. Kaper, P. I. Tarr, and R. A. Welch. 2002. StcE, a metalloprotease secreted by Escherichia coli O157:H7, specifically cleaves C1 esterase inhibitor. Mol. Microbiol. 45:277-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leverton, L. Q., and J. B. Kaper. 2005. Temporal expression of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes in an in vitro model of infection. Infect. Immun. 73:1034-1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levine, M. M. 1987. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J. Infect. Dis. 155:377-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li, M., I. Rosenshine, S. L. Tung, X. H. Wang, D. Friedberg, C. L. Hew, and K. Y. Leung. 2004. Comparative proteomic analysis of extracellular proteins of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains and their ihf and ler mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5274-5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lio, J. C., and W. J. Syu. 2004. Identification of a negative regulator for the pathogenicity island of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Biomed. Sci. 11:855-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Liu, Q., and C. C. Richardson. 1993. Gene 5.5 protein of bacteriophage T7 inhibits the nucleoid protein H-NS of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:1761-1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lucchini, S., G. Rowley, M. D. Goldberg, D. Hurd, M. Harrison, and J. C. Hinton. 2006. H-NS mediates the silencing of laterally acquired genes in bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2:e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lucht, J. M., P. Dersch, B. Kempf, and E. Bremer. 1994. Interactions of the nucleoid-associated DNA-binding protein H-NS with the regulatory region of the osmotically controlled proU operon of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 269:6578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Magnusson, L. U., A. Farewell, and T. Nystrom. 2005. ppGpp: a global regulator in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 13:236-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martínez-Laguna, Y., E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 1999. Autoactivation and environmental regulation of bfpT expression, the gene coding for the transcriptional activator of bfpA in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33:153-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McDaniel, T. K., and J. B. Kaper. 1997. A cloned pathogenicity island from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli confers the attaching and effacing phenotype on E. coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol. 23:399-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McNamara, B. P., A. Koutsouris, C. B. O'Connell, J. P. Nougayrede, M. S. Donnenberg, and G. Hecht. 2001. Translocated EspF protein from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli disrupts host intestinal barrier function. J. Clin. Investig. 107:621-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mellies, J. L., S. J. Elliott, V. Sperandio, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler). Mol. Microbiol. 33:296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mellies, J. L., K. R. Haack, and D. C. Galligan. 2007. SOS regulation of the type III secretion system of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:2863-2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mellies, J. L., F. Navarro-Garcia, I. Okeke, J. Frederickson, J. P. Nataro, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. espC pathogenicity island of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes an enterotoxin. Infect. Immun. 69:315-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mills, M., K. C. Meysick, and A. D. O'Brien. 2000. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor type 1 of uropathogenic Escherichia coli kills cultured human uroepithelial 5637 cells by an apoptotic mechanism. Infect. Immun. 68:5869-5880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moon, H. W., S. C. Whipp, R. A. Argenzio, M. M. Levine, and R. A. Giannella. 1983. Attaching and effacing activities of rabbit and human enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in pig and rabbit intestines. Infect. Immun. 41:1340-1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Munson, G. P., L. G. Holcomb, and J. R. Scott. 2001. Novel group of virulence activators within the AraC family that are not restricted to upstream binding sites. Infect. Immun. 69:186-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nakanishi, N., H. Abe, Y. Ogura, T. Hayashi, K. Tashiro, S. Kuhara, N. Sugimoto, and T. Tobe. 2006. ppGpp with DksA controls gene expression in the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli through activation of two virulence regulatory genes. Mol. Microbiol. 61:194-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Navarre, W. W., S. Porwollik, Y. Wang, M. McClelland, H. Rosen, S. J. Libby, and F. C. Fang. 2006. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313:236-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Navarro-Garcia, F., A. Canizalez-Roman, B. Q. Sui, J. P. Nataro, and Y. Azamar. 2004. The serine protease motif of EspC from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli produces epithelial damage by a mechanism different from that of Pet toxin from enteroaggregative E. coli. Infect. Immun. 72:3609-3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Neely, M. N., and D. I. Friedman. 1998. Functional and genetic analysis of regulatory regions of coliphage H-19B: location of Shiga-like toxin and lysis genes suggest a role for phage functions in toxin release. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1255-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nevesinjac, A. Z., and T. L. Raivio. 2005. The Cpx envelope stress response affects expression of the type IV bundle-forming pili of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187:672-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nieto, J. M., M. Carmona, S. Bolland, Y. Jubete, F. de la Cruz, and A. Juarez. 1991. The hha gene modulates haemolysin expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1285-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nougayrede, J. P., and M. S. Donnenberg. 2004. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli EspF is targeted to mitochondria and is required to initiate the mitochondrial death pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 6:1097-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nougayrede, J. P., P. J. Fernandes, and M. S. Donnenberg. 2003. Adhesion of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to host cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5:359-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Parsot, C., R. Menard, P. Gounon, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1995. Enhanced secretion through the Shigella flexneri Mxi-Spa translocon leads to assembly of extracellular proteins into macromolecular structures. Mol. Microbiol. 16:291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Poore, C. A., and H. L. Mobley. 2003. Differential regulation of the Proteus mirabilis urease gene cluster by UreR and H-NS. Microbiology 149:3383-3394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Porter, M. E., P. Mitchell, A. Free, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2005. The LEE1 promoters from both enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli can be activated by PerC-like proteins from either organism. J. Bacteriol. 187:458-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Porter, M. E., P. Mitchell, A. J. Roe, A. Free, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2004. Direct and indirect transcriptional activation of virulence genes by an AraC-like protein, PerA from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1117-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Puente, J. L., D. Bieber, S. W. Ramer, W. Murray, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1996. The bundle-forming pili of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: transcriptional regulation by environmental signals. Mol. Microbiol. 20:87-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reading, N. C., A. G. Torres, M. M. Kendall, D. T. Hughes, K. Yamamoto, and V. Sperandio. 2007. A novel two-component signaling system that activates transcription of an enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli effector involved in remodeling of host actin. J. Bacteriol. 189:2468-2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reece, S., C. P. Simmons, R. J. Fitzhenry, S. Matthews, A. D. Phillips, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 2001. Site-directed mutagenesis of intimin alpha modulates intimin-mediated tissue tropism and host specificity. Mol. Microbiol. 40:86-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rimsky, S. 2004. Structure of the histone-like protein H-NS and its role in regulation and genome superstructure. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ritchie, J. M., and M. K. Waldor. 2005. The locus of enterocyte effacement-encoded effector proteins all promote enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli pathogenicity in infant rabbits. Infect. Immun. 73:1466-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roe, A. J., S. W. Naylor, K. J. Spears, H. M. Yull, T. A. Dransfield, M. Oxford, I. J. McKendrick, M. Porter, M. J. Woodward, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2004. Co-ordinate single-cell expression of LEE4- and LEE5-encoded proteins of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Mol. Microbiol. 54:337-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roe, A. J., H. Yull, S. W. Naylor, M. J. Woodward, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2003. Heterogeneous surface expression of EspA translocon filaments by Escherichia coli O157:H7 is controlled at the posttranscriptional level. Infect. Immun. 71:5900-5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rosenshine, I., S. Ruschkowski, and B. B. Finlay. 1996. Expression of attaching/effacing activity by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on growth phase, temperature, and protein synthesis upon contact with epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 64:966-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sánchez-SanMartín, C., V. H. Bustamante, E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 2001. Transcriptional regulation of the orf19 gene and the tir-cesT-eae operon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:2823-2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Scaletsky, I. C., M. L. Silva, and L. R. Trabulsi. 1984. Distinctive patterns of adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to HeLa cells. Infect. Immun. 45:534-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sharma, V. K., S. A. Carlson, and T. A. Casey. 2005. Hyperadherence of an hha mutant of Escherichia coli O157:H7 is correlated with enhanced expression of LEE-encoded adherence genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 243:189-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sharma, V. K., and R. L. Zuerner. 2004. Role of hha and ler in transcriptional regulation of the esp operon of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 186:7290-7301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sharp, F. C., and V. Sperandio. 2007. QseA directly activates transcription of LEE1 in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 75:2432-2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shin, S., M. P. Castanie-Cornet, J. W. Foster, J. A. Crawford, C. Brinkley, and J. B. Kaper. 2001. An activator of glutamate decarboxylase genes regulates the expression of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes through control of the plasmid-encoded regulator, Per. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1133-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sircili, M. P., M. Walters, L. R. Trabulsi, and V. Sperandio. 2004. Modulation of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence by quorum sensing. Infect. Immun. 72:2329-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sohel, I., J. L. Puente, W. J. Murray, J. Vuopio-Varkila, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1993. Cloning and characterization of the bundle-forming pilin gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and its distribution in Salmonella serotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 7:563-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sohel, I., J. L. Puente, S. W. Ramer, D. Bieber, C. Y. Wu, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1996. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a gene cluster coding for bundle-forming pilus morphogenesis. J. Bacteriol. 178:2613-2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sperandio, V. 2004. Striking a balance: inter-kingdom cell-to-cell signaling, friendship or war? Trends Immunol. 25:505-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sperandio, V., C. C. Li, and J. B. Kaper. 2002. Quorum-sensing Escherichia coli regulator A: a regulator of the LysR family involved in the regulation of the locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island in enterohemorrhagic E. coli. Infect. Immun. 70:3085-3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sperandio, V., J. L. Mellies, R. M. Delahay, G. Frankel, J. A. Crawford, W. Nguyen, and J. B. Kaper. 2000. Activation of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) LEE2 and LEE3 operons by Ler. Mol. Microbiol. 38:781-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]