Abstract

Dengue is one of the most important diseases in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, with an estimated 2.5 billion people being at risk. Detection of dengue virus infections has great importance for the clinical management of patients, surveillance, and clinical trial assessments. Traditionally, blood samples are collected in serum separator tubes, processed for serum, and then taken to the laboratory for analysis. The use of whole blood has the potential advantages of requiring less blood, providing quicker results, and perhaps providing better sensitivity during the acute phase of the disease. We compared the results obtained by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) with blood drawn into tubes containing EDTA and those obtained by RT-PCR with blood samples in serum separator tubes from 108 individuals clinically suspected of being infected with dengue virus. We determined that the extraction of RNA from whole blood followed by RT-PCR resulted in a higher detection rate than the use of serum or plasma. Using a selection of these samples, we also found that our ability to detect virus by direct C6/36 cell culture and mosquito inoculation was enhanced by using whole blood but not to the same extent as that seen by the use of RT-PCR.

Dengue viruses (DENVs) are mosquito-borne human pathogens that cause both asymptomatic and severe infections (5). Most commonly found in the tropics and subtropics, DENV infections have been increasing in prevalence and severity (9). Estimates suggest that dengue affects 100 million people per year, causing more than 20,000 deaths (6). Although there are no vaccines or specific treatments available to date, several vaccines are in various stages of research and/or clinical trials (1, 3, 4, 14, 17). Rapid and reliable case detection is important for clinical management of the disease as well as determination of vaccine efficacy during clinical trials. Current methods of disease detection rely on sensitive reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR detection of DENV in serum, with the “gold standard” being determination of DENV-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM)/IgG ratios by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) (10). For simple diagnostic purposes, samples suspected of being infected with DENV are tested serologically and the DENV isolates are serotyped by RT-PCR and/or virus isolation techniques. The window for viral RNA detection is limited to 5 to 7 days after the initial infection, and patients often arrive at the hospital too late for viral RNA detection (13). In addition, serological diagnostics require the patient to return 7 to 10 days later for collection of a convalescent-phase blood sample. Often, retrieval of this second sample is difficult because the symptoms of disease have passed and patients are unwilling to provide another blood sample. These constraints may lead to the underdiagnosis of the disease.

The methods currently used to detect acute DENV infections are IgM/IgG ELISA, RT-PCR, and virus isolation. Each has advantages and disadvantages. The IgM/IgG ELISA has proven extremely reliable and can be used to distinguish between primary and secondary infections; however, this assay requires a convalescent-phase sample collected 7 to 10 days after defervescence and therefore is difficult to use as a diagnostic test (10). RT-PCR is the most rapid of the three techniques but must be used during the relatively short viremic phase, and the assay is prone to false-positive results (12, 19). Virus isolation on cell culture substrate is likely the most specific method, but it may be the least sensitive and is certainly the slowest, often taking 7 to 21 days and several passages to obtain detectable viruses (16, 22, 24). Isolation of DENV is often achieved by direct plating on susceptible cells, such as C6/36 cells. The rate of direct isolation by this method is low, but it improves if blood is taken during the first days of illness and while the patient is febrile (16). The most sensitive virus isolation technique is direct intrathoracic inoculation of potentially infected sera into mosquitoes (7). However, this technique is labor-intensive, requires an insectory, and can take up to 30 days for the results to be obtained.

In this study we had two objectives: (i) to determine if we could increase the rate of detection of DENV from clinical samples by our RT-PCR with whole blood as a source for viral RNA and (ii) to determine if we could increase our rate of virus isolation by using whole blood as the intact virus reservoir.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical samples.

As part of a routine diagnostic service for RT-PCR and serological DENV diagnostics, we identified and obtained 108 blood specimens from pediatric patients with suspected DENV infection presenting to the Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health (The Children's Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand) from years 2003 and 2005. An aliquot of whole blood/plasma or whole blood/serum was prepared from the acute-phase specimens (56 and 52 specimens, respectively). These specimens were kept as 100-μl aliquots and were stored at −70°C before they were tested for DENV infection by the RT-PCR procedure described below. The DENV serology of acute- and convalescent-phase samples was used to define primary or secondary infections. Those samples for which a convalescent-phase sample was lacking were labeled as “not serologically diagnosed.” Negative control whole blood, plasma, and serum were obtained from a source negative for DENV by virus isolation and serology. For virus isolation, we randomly selected 30 whole-blood and serum pairs from the original 108 samples.

Specimen preparation.

Five milliliters of whole blood was drawn from each patient by venipuncture and collected in a Vacutainer blood collection tube containing a 15% EDTA solution. A total of 200 μl of whole blood was directly used for viral RNA extraction and RT-PCR. The remaining blood was used for plasma preparation. The plasma samples were isolated from the whole blood by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. A 100-μl aliquot of plasma was transferred to a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube for viral RNA extraction and RT-PCR. The blood specimens used for the preparation of serum were collected in a serum separator tube with clot activator and gel. A small aliquot of whole blood for PCR analysis was removed from the tube within 30 min of collection and frozen at −70°C. If the blood clot was fully formed and could not be drawn through a pipette, the sample was excluded from this study. The remaining blood specimens were left at room temperature (25 to 30°C) for 30 min for complete coagulation. Subsequently, they were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Aliquots (100 μl) of serum were transferred to 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes for viral RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

RNA extraction and RT-PCR.

Viral RNA was extracted from 200 μl of each specimen by using the TRIzol (GIBCO BRL) reagent, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RT-PCR was performed according to the protocol of Lanciotti et al. (12), with the following modifications: avian myeloblastosis virus RT (Promega, Madison, WI) was used in the first round of RT-PCR. The concentrations of primers used in the RT-PCR and nested reactions were reduced from 50 pmol to 12.5 pmol per reaction, and the number of nested PCR amplification cycles was increased to 25 (12).

Virus strains.

The DENV-positive control strains used in the RT-PCR were DENV serotype 1 (DENV-1) strain Hawaii, DENV-2 strain NGC, DENV-3 strain H87 (Philippines), and DENV-4 strain 814669 (Dominica). Because of the high prevalence of DENV-1 during the study, one banked DENV-1 primary isolate from Thailand was selected for use in the sensitivity test. The virus was amplified in C6/36 cell culture for three passages, and the titer was determined by the standard plaque titration method.

Sensitivity assay.

Whole blood was analyzed by extracting RNA from 100 μl of each spiked whole-blood sample with DENV-1 at 102 to 10−4 PFU/ml, and the remaining blood was used for plasma or serum preparation. RNA was extracted from 100 μl of plasma or serum (derived from DENV-1-spiked whole blood) and was then analyzed by RT-PCR. To test the blood components for RT-PCR sensitivity, DENV-negative whole blood, plasma, and serum were spiked with serial dilutions of DENV-1. The stock virus of 3.5 × 103 PFU/ml was serially diluted 10-fold with each of the three different diluents. RNA was extracted from the 100 μl of dilutions from 102 to 10−5 PFU/ml of all three diluents and analyzed by RT-PCR.

Serological confirmation test.

The anti-DENV IgM/IgG ELISA method used was previously described by Innis et al. (10). An acute DENV infection was defined as the presence of 40 units or more of DENV-specific IgM in a single specimen (with the DENV-specific IgM titer being greater than the Japanese encephalitis virus-specific IgM titer) or a rise in the DENV-specific IgM titer from less than 15 units in the acute-phase specimen to more than 30 units in the convalescent-phase specimen. On the basis of previous work (D. W. Vaughn and B. L. Innis, unpublished data). In the absence of a DENV-specific IgM titer of ≥40 units, AFRIMS uses the convention of a twofold increase in the DENV-specific IgG titer between the acute- and convalescent-phase sample, with an absolute value of ≥100 units used to define secondary DENV infection. This was validated by use of the WHO criteria for hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers for primary and secondary infections (10, 19, 23; unpublished data). In addition, DENV primary and secondary infections were also determined when the ratios of anti-DENV IgM to anti-DENV IgG were >1.8 and <1.8, respectively. Specimens were considered negative for serological evidence of a recent DENV infection if paired specimens collected at least 7 days apart were absent of DENV-specific antibody, as defined above.

Viral isolation by cell culture and mosquito inoculation.

One milliliter of whole blood collected from each patient was transferred into a blood collection tube (BD) with EDTA and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to give a final DMSO concentration of 7.5 to 10%, and the tube was kept in ice. Serum was collected in a serum separator tube and processed as described above. Specimens were transported to the laboratory within 3 h.

Two milliliters of a 1:20 dilution of each whole-blood or serum specimen in maintenance medium (MM; RPMI 1640, 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin; GIBCO) was added to a 90% confluent monolayer of 3-day-old C6/36 cells in a 25-cm3 flask, and the flask was incubated for 45 to 60 min at room temperature (9). Four milliliters of MM was then added to each flask, and the flask was incubated at 28°C overnight. When the cells detached, they were collected and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the pellet was resuspended in 2 ml fresh MM and reinoculated into new confluent C6/36 cell monolayers. The virus-infected cells were blindly passed to a new flask with C6/36 cells on every 7th day for three passages and were incubated at 35°C. The virus-infected tissue culture supernatant was harvested and stored at −70°C until use.

Undiluted serum or whole blood (0.3 μl/mosquito) was intrathoracically inoculated into each of 20 Toxorhynchites splendens mosquitoes. The mosquitoes were fed by use of a cotton cushion soaked with 10% sugar and were incubated at 30 to 32°C for 10 days. The surviving mosquitoes were killed and stored at −70°C. The mosquitoes' heads were cut and squashed on slides and fixed for 10 min with cold acetone, and the slides were stored at −70°C until use. The slides were stained with a 1:160 dilution (20 μl/well) of antiflavivirus antibodies in hyperimmune mouse ascitic fluid and incubated for 30 min at 35°C. The slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline for 10 min. A 1:40 dilution of sheep anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule) fluorescein isothiocyanate (20 μl/well; Sigma) was added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 35°C, followed by a 10-min wash with phosphate-buffered saline. The slides were mounted with 90% glycerol in phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and viewed by immunofluorescence microscopy; and the results were compared with those for DENV-1-, DENV-2-, DENV-3-, and DENV-4-positive and -negative controls (7, 11, 15).

Statistical analysis.

The association between the sensitivity of DENV detection by RT-PCR with whole-blood or plasma/serum samples was analyzed by the McNemar test for paired samples, with a 5% level used to establish a statistically significant difference. The chi-square or Fisher exact test was used for categorical comparisons. Statistical comparisons were made by using SPSS (version 10.1) and Epi Info (version 3.3.2) software.

RESULTS

Prior to testing of the clinical samples, we determined the sensitivity of the DENV RT-PCR with different blood components by spiking DENV- and antibody-negative whole blood with and without EDTA with 10-fold serial dilutions of DENV-1 starting at 102 PFU and ending at 10−4 PFU. After the samples were spiked, the blood tubes were processed for either serum or plasma, after which RNA was immediately isolated from 100 μl of whole blood, serum, and plasma. In the absence of EDTA, the threshold of viral RNA detection from whole blood was 1 log lower (for the detection of virus at 0.1 PFU/ml) than that from serum. The same trend was true in the presence of EDTA, in which the threshold of viral RNA detection in whole blood was 1 log lower (for the detection of virus at 0.01 PFU/ml) than that from plasma (results not shown). The increase in titer recovered from tubes containing EDTA was likely an effect of its anticoagulation factors, which allow the virus to become homogeneously mixed with all of the blood components. It is difficult to assess whether equivalent amounts of virus were actually spiked into the whole-blood components due to the immediate clotting effect in the tubes lacking EDTA, and further investigations are being considered.

To better assess the sensitivity of the DENV RT-PCR with whole blood, we separately spiked each component (whole blood, plasma, and serum) with 10-fold serial dilutions of DENV-1 starting at 102 PFU and ending at 10−5 PFU. RNA was extracted from each sample, and the standard RT-PCR and nested PCR were used to determine the limit of positivity. We were able to consistently detect viral RNA from whole blood at levels 2 log units lower than the level detected from plasma or serum (0.001, 0.1, and 1 PFU/ml, respectively) (data not shown).

One hundred eight samples (52 pairs of whole-blood and serum samples and 56 pairs of whole-blood and plasma samples) from patients with suspected DENV infection were obtained (Table 1). All patients (60 males and 48 females) had a fever or a history of a fever during the previous 3 days. At the time of the blood draw, the average temperature was 37.7°C and the average duration of disease was 4.4 days, based on an oral history of when the symptoms began. Of the 108 cases, 81 paired acute- and convalescent-phase samples resulted in a serological diagnosis of 5 primary and 76 secondary DENV infections. Three samples were determined to not be infected with DENV, and a convalescent-phase sample was not available for 24 patients and therefore a serological diagnosis could not be made.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of patients from whom samples were obtained

| Characteristic | Result for the following sample:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Whole blood/plasma | Whole blood/serum | |

| No. of patients | 56 | 52 |

| Primary DENV infection | 2 | 3 |

| Secondary DENV infection | 46 | 30 |

| Dengue negative (serology) | 1 | 2 |

| Not serologically diagnoseda | 7 | 17 |

| No. of patients with final diagnosis of: | ||

| DF | 25 | 18 |

| DHF | 29 | 22 |

| No. of: | ||

| Males | 31 | 29 |

| Females | 25 | 23 |

| Mean day of diseaseb | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| Mean temp (°C) | 37.7 | 37.6 |

| Mean age (yr) | 9.5 | 8.43 |

A convalescent-phase sample was not available.

Number of days from the initial onset of disease until the time that blood was drawn.

We were able to detect DENV RNA in 80 (74%) whole-blood samples and 56 (52%) of the corresponding plasma/serum samples (Table 2). RT-PCR of the whole blood compared to RT-PCR of its plasma or serum derivative increased our ability to detect and serotype 7 and 6 additional samples, respectively, from the 24 samples that were not previously confirmed to be infected with DENV by serology (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

DENV detection by RT-PCR in patients' whole blood and their derivative plasma/serum

| Sample | No. of samples positive for the following type:

|

No. of samples positive/total no. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | DENV-2 | DENV-3 | DEN-4 | ||

| Whole blood | 38 | 17 | 3 | 22 | 80/108 (74)a |

| Plasma/serum | 26 | 12 | 1 | 17 | 56/108 (52)a |

P < 0.001.

TABLE 3.

RT-PCR results by serological diagnosis

| ELISA result | No. of samples | No. of samples DENV positive by RT-PCR

|

P value for whole blood vs plasma/serum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole blood | Plasma/serum | |||

| DENV positive | 81 | 73 | 50 | <0.001 |

| DENV negative | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| No serological diagnosis | 24 | 7 | 6 | NSa |

| Total | 108 | 80 | 56 | <0.001 |

NS, not significant.

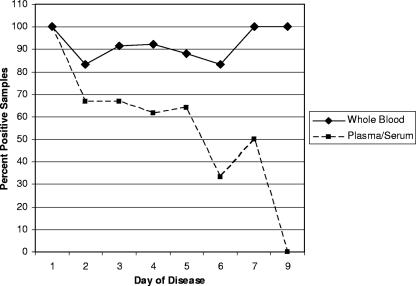

We used the day of disease onset (according to the subjective account by the patients or the parents of the patients of when the first symptoms occurred) to determine if the use of whole blood could increase the viremic window to confirm the diagnosis of DENV infection by RT-PCR. The use of whole blood enabled the detection of viral RNA through the 9th day of disease, whereas the use of plasma/serum enabled the detection of viral RNA through the 7th day. In addition, DENV RNA was detected more often in whole-blood samples than in the corresponding plasma samples on every day of disease except day 1 (Table 4 and Fig. 1).

TABLE 4.

Efficiency of RT-PCR for detection of DENV in whole blood and plasma/serum samples on each day of disease

| Day of disease | No. of RT-PCR-positive samples/total no. of ELISA-positive samples (%)

|

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole blood | Plasma/serum | ||

| 1 | 3/3 (100) | 3/3 (100) | NSa |

| 2 | 5/6 (83) | 4/6 (67) | NS |

| 3 | 11/12 (92) | 8/12 (67) | NS |

| 4 | 24/26 (92) | 16/26 (62) | 0.008 |

| 5 | 22/25 (88) | 16/25 (64) | 0.05 |

| 6 | 5/6 (83) | 2/6 (33) | NS |

| 7 | 2/2 (100) | 1/2 (50) | NS |

| 8 | 0/0 | 0/0 | |

| 9 | 1/1 (100) | 0/1 | NS |

| Total | 73/81 (90) | 50/81 (62) | <0.001 |

NS, not significant.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of positive whole-blood and serum/plasma clinical samples detected by RT-PCR by day of illness. The day of illness was calculated on the basis of the patient's recall of the first day of fever.

Among the 108 samples, a clinical diagnosis of dengue fever (DF) could be made for 43 samples (25 whole blood/plasma samples and 18 whole-blood/serum samples) on the basis of the WHO criteria and a clinical diagnosis of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF; types I to III) could be made for 51 samples (29 whole-blood/plasma samples and 22 whole-blood/serum samples) (23). In every case, whether whole blood, plasma, or serum was used, the percentage of PCR-positive samples was greater for patients with DHF than for patients with DF. However, it reached statistical significance only for RT-PCR of whole-blood and serum samples (P = 0.02 and P = 0.005, respectively).

For some studies it is necessary to isolate virus directly from source material rather than to rely on molecular techniques in order to fully detect and characterize the virus. Isolation of DENV is often achieved by direct plating on susceptible cells. The rate of direct isolation by this method is rare but improves if blood is taken during the first few days of illness and while the patient is febrile (16). The most sensitive technique for the isolation of DENV is intrathoracic inoculation of human sera into mosquitoes (7).

We randomly selected 30 whole-blood and serum sample pairs from among the original samples to determine if the results obtained by PCR were valid for virus isolation. By using our standard testing algorithm, seven samples were ineligible for virus isolation because they were RT-PCR negative, and in our experience viruses are rarely recovered from such samples on cell substrates or by inoculation of mosquitoes.

We were able to isolate virus by direct C6/36 cell inoculation from more whole-blood samples than from their corresponding serum samples (18/23 samples [12 patients with DHF and 6 patients with DF] and 10/23 samples [8 patients with DHF and 2 patients with DF], respectively; P = 0.008). According to our testing algorithm, samples that were negative for direct viral isolation (whole blood or serum samples) on C6/36 cells but that were RT-PCR positive (n = 5 and 13, respectively) were injected intrathoracically into Toxorhynchites splendens mosquitoes to determine a final isolation rate. Of the samples negative by C6/36 cell inoculation, 3/5 whole-blood samples (all from patients with DF) and 8/13 serum samples (2 from patients with DHF and 6 from patients with DF) were positive by mosquito inoculation. Overall, 21/23 (91%) of the whole-blood samples were positive for virus isolation, whereas 18/23 (78%) of the corresponding serum samples were positive for virus isolation.

DISCUSSION

In this study we wished to determine if we would increase our confirmed DENV detection capabilities in a clinical setting. The use of whole blood has a number of advantages, including the ability to detect nucleic acid directly and/or the ability to isolate virus by placement of the sample on cells. To obtain serum, at the very least, blood must be centrifuged to remove cells, which requires additional equipment and time. Serum is often the clinical sample of choice, as it can be used in a variety of assays and is presumed to be free of PCR inhibitors, such as anticoagulation agents and the large amount of hemoglobin present in red blood cells.

The diagnosis of dengue disease often relies on serology, which requires acute- and convalescent-phase samples and which cannot determine the infecting DENV serotype. RT-PCR or virus isolation is used during the acute phase of disease and identifies the infecting serotype, but DENV nucleic acid can be detected only during the early part of the infection (8). Extending the diagnostic window or the sensitivity of either assay could reduce the number of tests that must be run for an accurate diagnosis, thereby decreasing the cost and the time required to give an accurate laboratory-confirmed diagnosis to the physician.

In this study, which used clinical samples obtained from patients with suspected dengue, the DENV RT-PCR was positive significantly more often when whole blood was used as the substrate (74%) than when plasma or serum from the same patient was used (52%). Of the 81 samples with serologically confirmed DENV infection, DENV infection was positively identified in 73 (90%) whole-blood samples but only 50 (62%) plasma or serum samples.

In this study our ability to diagnose DENV infection by both RT-PCR and virus isolation was greater when we used whole blood than when we used plasma or serum. It should be noted that we used samples collected by well-trained technicians in a hospital where a cold chain has been established and is used. Moreover, these samples were collected from a hospital setting and likely represent samples from a population with more severe cases of illness. Yet, this study suggests that the use of whole blood is a practical and better option.

Our data are in contrast to those of several studies, including that of Waterman et al. (21), who concluded that the isolation of virus from peripheral blood by the mosquito isolation technique is less sensitive than the isolation of virus from serum or plasma and who saw moderate increases in the rate of isolation of virus from patients with primary infections and if the samples were collected during the first 3 days of disease. De Paula and Lopes da Fonseca (2) found that the detection of DENV from serum samples by RT-PCR was more sensitive than the detection of DENV from buffy coat or blood samples. These differences may reflect differences in the times of sample collection between the studies, which averaged 10 days in the study of Waterman et al. (21) and after day 5 for 93% of the samples in the study of De Paula and Lopes da Fonseca (2); our average time of sample collection was 4 days after the onset of symptoms. In fact, our study contained no samples obtained past day 9 from the start of symptoms, although even for samples collected later in the course of infection, whole blood appeared to be superior. The use of the day of disease is one significant limitation in our efforts to determine if the use of whole blood increases the ability to increase the amount of time (number of days) after the onset of symptoms that samples can be obtained and used for the definitive confirmation of DENV infection by PCR. Because these samples were collected from outpatients with suspected dengue and tested as part of the clinical service provided in the local hospital, an objective fever history is nearly impossible to obtain unless the patient is admitted to the hospital until defeverscence. Despite this limitation, using the patient's or the patient's parents' recall of the time of illness onset, we were able to determine, albeit subjectively, an estimate of the day of disease onset to establish that the use of whole blood does modestly increase the day from which dengue disease can be confirmed by PCR in the laboratory.

The severity of disease is a second plausible explanation between the contrasting results of this study and others. Waterman et al. (21) described the patients from whom their samples were collected as having clinically mild or classic dengue fever; in contrast, in our study 54% of the patients had severe cases (DHF types I to III) of confirmed dengue. Our PCR and viral isolation data suggest that the severity of disease does affect the overall rate of detection, but the use of whole blood for diagnosis or case confirmation is increased, regardless of the severity of disease.

Our results are in agreement with those of Wang et al. (20), albeit with distinctly different clinical samples. Wang et al. studied 104 acute- and convalescent-phase plasma/serum samples and 35 peripheral blood leukocyte samples in attempts to develop an efficient diagnostic algorithm for the detection of dengue disease using traditional techniques (20). That study showed that RT-PCR could detect DENV RNA in only 20% of the acute plasma/serum samples, while 73% of the acute peripheral blood leukocyte samples were positive for the DENV genome by RT-PCR. Similarly, Scott and others reported that they were able to isolate viruses at a significantly higher rate from isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes than from plasma or serum (16). Our results obtained by direct isolation of virus on C6/36 cells and by the mosquito inoculation method with whole blood support these data as well. These increased rates of isolation with clinical samples containing cells are likely the result of the presence of replicating viruses within these cells as well as the presence of free virus in serum or plasma bound by immune complexes, which thereby prevents the infection of new cells.

Our study and others suggest that the presence of cells in whole blood and/or isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes increases the rate of DENV detection, despite the potential for the presence of inhibitors and endogenous nucleases in whole blood. Although this is unlikely, it could be a simple artifact of an increased viral load as a consequence of the collection of samples in a hospital setting or the fact that a strict cold chain policy is used. However, when DENV-1 was spiked into whole blood and then the blood was immediately processed and the RNA was extracted, DENV was detected at a higher dilution in whole blood. This may imply the rapid entry of virus into cells. The presence of virus-infected cells within the whole-blood samples vastly increases the amount of viral genetic material, allowing the detection of samples with low levels of viremia that would otherwise be negative if serum or plasma was used as the clinical sample.

Acknowledgments

We express our extreme gratitude to all of the doctors and nurses at the Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health and special appreciation to the excellent technical and nursing staff in the Department of Virology at AFRIMS, most notably, Sumitda Narupiti, Somsak Imlarp, and Winai Kaneechit.

The views, opinions, and/or findings contained herein are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official U.S. Department of the Army position, policy, or decision.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chanthavanich, P., C. Luxemburger, C. Sirivichayakul, K. Lapphra, K. Pengsaa, S. Yoksan, A. Sabchareon, and J. Lang. 2006. Short report: immune response and occurrence of dengue infection in Thai children three to eight years after vaccination with live attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75:26-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Paula, S. O., and B. A. Lopes da Fonseca. 2002. Optimizing dengue diagnosis by RT-PCR in IgM-positive samples: comparison of whole blood, buffy-coat and serum as clinical samples. J. Virol. Methods 102:113-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durbin, A. P., S. S. Whitehead, J. McArthur, J. R. Perreault, J. E. Blaney, Jr., B. Thumar, B. R. Murphy, and R. A. Karron. 2005. rDEN4delta30, a live attenuated dengue virus type 4 vaccine candidate, is safe, immunogenic, and highly infectious in healthy adult volunteers. J. Infect. Dis. 191:710-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelman, R., S. S. Wasserman, S. A. Bodison, R. J. Putnak, K. H. Eckels, D. Tang, N. Kanesa-Thasan, D. W. Vaughn, B. L. Innis, and W. Sun. 2003. Phase I trial of 16 formulations of a tetravalent live-attenuated dengue vaccine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 69:48-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endy, T. P., S. Chunsuttiwat, A. Nisalak, D. H. Libraty, S. Green, A. L. Rothman, D. W. Vaughn, and F. A. Ennis. 2002. Epidemiology of inapparent and symptomatic acute dengue virus infection: a prospective study of primary school children in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. Am. J. Epidemiol. 156:40-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gubler, D. J. 1998. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:480-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gubler, D. J., and L. Rosen. 1976. A simple technique for demonstrating transmission of dengue virus by mosquitoes without the use of vertebrate hosts. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 25:146-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubler, D. J., W. Suharyono, R. Tan, M. Abidin, and A. Sie. 1981. Viraemia in patients with naturally acquired dengue infection. Bull. W. H. O. 59:623-630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gubler, D. J., and D. W. Trent. 1993. Emergence of epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health problem in the Americas. Infect. Agents Dis. 2:383-393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Innis, B. L., A. Nisalak, S. Nimmannitya, S. Kusalerdchariya, V. Chongswasdi, S. Suntayakorn, P. Puttisri, and C. H. Hoke, Jr. 1989. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to characterize dengue infections where dengue and Japanese encephalitis co-circulate. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 40:418-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuno, G., D. J. Gubler, M. Velez, and A. Oliver. 1985. Comparative sensitivity of three mosquito cell lines for isolation of dengue viruses. Bull. W. H. O. 63:279-286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanciotti, R. S., C. H. Calisher, D. J. Gubler, G. J. Chang, and A. V. Vorndam. 1992. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples by using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:545-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libraty, D. H., T. P. Endy, H. S. Houng, S. Green, S. Kalayanarooj, S. Suntayakorn, W. Chansiriwongs, D. W. Vaughn, A. Nisalak, F. A. Ennis, and A. L. Rothman. 2002. Differing influences of virus burden and immune activation on disease severity in secondary dengue-3 virus infections. J. Infect. Dis. 185:1213-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raviprakash, K., D. Apt, A. Brinkman, C. Skinner, S. Yang, G. Dawes, D. Ewing, S. J. Wu, S. Bass, J. Punnonen, and K. Porter. 2006. A chimeric tetravalent dengue DNA vaccine elicits neutralizing antibody to all four virus serotypes in rhesus macaques. Virology 353:166-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen, L., and D. Gubler. 1974. The use of mosquitoes to detect and propagate dengue viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 23:1153-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott, R. M., A. Nisalak, U. Cheamudon, S. Seridhoranakul, and S. Nimmannitya. 1980. Isolation of dengue viruses peripheral blood leukocytes of patients with hemorrhagic fever. J. Infect. Dis. 141:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun, W., A. Nisalak, M. Gettayacamin, K. H. Eckels, J. R. Putnak, D. W. Vaughn, B. L. Innis, S. J. Thomas, and T. P. Endy. 2006. Protection of rhesus monkeys against dengue virus challenge after tetravalent live attenuated dengue virus vaccination. J. Infect. Dis. 193:1658-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reference deleted.

- 19.Vaughn, D. W., S. Green, S. Kalayanarooj, B. L. Innis, S. Nimmannitya, S. Suntayakorn, A. L. Rothman, F. A. Ennis, and A. Nisalak. 1997. Dengue in the early febrile phase: viremia and antibody responses. J. Infect. Dis. 176:322-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, H. L., K. H. Lin, Y. Y. Yueh, L. Chow, Y. C. Wu, H. Y. Chen, M. M. Sheu, and W. J. Chen. 2000. Efficient diagnosis of dengue infections using patients' peripheral blood leukocytes and serum/plasma. Intervirology 43:107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waterman, S. H., G. Kuno, D. J. Gubler, and G. E. Sather. 1985. Low rates of antigen detection and virus isolation from the peripheral blood leukocytes of dengue fever patients. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 34:380-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watts, D. M., B. A. Harrison, A. Nisalak, R. M. Scott, and D. S. Burke. 1982. Evaluation of Toxorhynchites splendens (Diptera: Culicidae) as a bioassay host for dengue viruses. J. Med. Entomol. 19:54-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. 1997. Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control, 2nd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 24.Yuill, T. M., P. Sukhavachana, A. Nisalak, and P. K. Russell. 1968. Dengue-virus recovery by direct and delayed plaques in LLC-MK2 cells. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 17:441-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]