Abstract

The sequencing of the VP1 hypervariable region of the human enterovirus (HEV) genome has become the reference test for typing field isolates. This study describes a new strategy for typing HEV at the serotype level that uses a reverse transcription-PCR assay targeting the central part of the VP2 capsid protein. Two pairs of primers were used to amplify a fragment of 584 bp (with reference to the PV-1 sequence) or a part of it (368 bp) for typing. For a few strains not amplified by the first PCR, seminested primers enhanced the sensitivity (which was found to be approximately 10−1 and 10−4 50% tissue culture infective dose per reaction tube for the first and seminested assay, respectively). The typing method was then applied to 116 clinical and environmental strains of HEV. Sixty-one typeable isolates were correctly identified at the serotype level by comparison to seroneutralization. Forty-eight of 55 “untypeable” strains (87.3%) exhibited the same serotype using VP1 and VP2 sequencing methods. For six strains (four identified as EV-71, one as E-9, and one as E-30 by the VP2 method), no amplification was obtained by the VP1 method. The last strain, typed as CV-B4 by VP1 and CV-B3 by VP2 and monovalent antiserum, could exhibit recombination within the capsid region. Although the VP2 method was tested on only 36 of the 68 HEV serotypes, it appears to be a promising strategy for typing HEV strains isolated on a routine basis. The good sensitivity of the seminested technique could avoid cell culture and allow HEV typing directly from PCR products.

Human enteroviruses (HEV) are among the most common of human viruses. Most infections are mild or asymptomatic, but some can lead to severe clinical presentations, especially in neonates and immunocompromised patients (32).

The genus Enterovirus of the family Picornaviridae includes nonenveloped viruses comprising a 7,500-nucleotide single-stranded positive RNA genome protected by an icosahedral capsid. The genome encodes seven nonstructural proteins implicated in viral replication and maturation and four structural proteins, VP1 to VP4. VP1, VP2, and VP3 are located at the surface of the viral capsid and are exposed to immune pressure, whereas VP4 is located inside the capsid.

The HEV serotypes were originally classified on the basis of antigenic properties and according to their natural and experimental pathogenesis: poliovirus (PV) infection in monkeys, coxsackievirus A (CV-A) and CV-B infection in suckling mice, and echovirus (E) infection in cell culture but not in mice (32). The molecular analysis of coding and noncoding regions (9) led to the classification of the 68 serotypes of HEV into five species (36): (i) HEV-A includes CV-A2, -3, -5 to -8, -10, -12, -14, and -16 and enterovirus 71 (EV-71) and -76; (ii) HEV-B includes CV-B1 to -6, CV-A9, and all Es, as well as EV-69, -73, -74, -75, -77, and -78; (iii) HEV-C includes CV-A1, -11, -13, -17, -20 to -22, and -24; (iv) EV-68 and -70 form the HEV-D group; and (v) the three serotypes of PV are still grouped into a separate Poliovirus species despite their low molecular diversity compared to HEV-C (6).

The typing of HEV strains consists of isolation of the virus in cell culture, followed by identification of the serotype. The conventional method for typing HEV is based on neutralization with mixed hyperimmune equine serum pools and specific monovalent polyclonal antisera for confirmation. This method was long the “gold standard” but is labor-intensive and time-consuming; in addition, many strains are found to be “untypeable” because of aggregation of virus particles, mixture of viruses, or emergence of variants that are antigenically different from the prototype strains used for the production of the antisera in the 1960s (19).

To circumvent these disadvantages, molecular methods based on reverse transcription-PCR and sequencing techniques were proposed for HEV identification. In order to identify all the serotypes of HEV, current studies target the region encoding the VP1 (3, 7, 20, 24, 25, 38) or the VP4 (10) capsid protein, with results concordant with those of the seroneutralization method. However, a unique set of primers is hardly sufficient to amplify all HEV serotypes, leading some authors to propose specific panels of primers fitting a subgroup of HEV (3, 11, 28, 38). Moreover, comparison of different typing methods has shown that some of them have failed to identify a few strains of HEV at the serotype level (5, 13, 14).

The present study describes a new strategy for typing HEV at the serotype level that uses a reverse transcription-PCR assay targeting the central part of the VP2 capsid protein. This region was chosen because of its high genetic variability, in accordance with the presence of neutralization epitopes (17), together with the ability to design relatively common primers flanking the sequence of interest. The results presented here show that the region can be used to classify correctly all the prototype strains of HEV. The method was applied to the typing of 61 HEV field strains typeable by seroneutralization and 55 “untypeable” HEV field strains in comparison to serological and/or VP1 typing methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Prototype strains.

The prototype strains of the 68 serotypes of HEV are listed in Table 1. Their VP2 coding sequences, retrieved from the GenBank database, were used for designing primers able to match all the serotypes of HEV. In addition, 12 prototype strains, namely, CV-A6, CV-A13, CV-A14, CV-B2, CV-B4, CV-B5, CV-B6, E-2, and E-6 and the 3 Sabin vaccinal strains of PV, were typed by the VP2 method.

TABLE 1.

Prototype strains of HEV used in this study

| Serotype | Molecular classificationa | Prototype strain | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| PV-1 | PV | Mahoney | V01149 |

| PV-2 | PV | Lansing | M12197 |

| PV-3 | PV | Leon | K01392 |

| CV-A1 | HEV-C | Tompkins | AF499635 |

| CV-A2 | HEV-A | Fleetwood | AY421760 |

| CV-A3 | HEV-A | Olson | AY421761 |

| CV-A4 | HEV-A | High Point | AY421762 |

| CV-A5 | HEV-A | Swartz | AY421763 |

| CV-A6 | HEV-A | Gdula | AY421764 |

| CV-A7 | HEV-A | Parker | AY421765 |

| CV-A8 | HEV-A | Donovan | AY421766 |

| CV-A9 | HEV-B | Griggs | D00627 |

| CV-A10 | HEV-A | Kowalik | AY421767 |

| CV-A11 | HEV-C | Belgium-1 | AF499636 |

| CV-A12 | HEV-A | Texas-12 | AY421768 |

| CV-A13 | HEV-C | Flores | AF499637 |

| CV-A14 | HEV-A | G-14 | AY421769 |

| CV-A16 | HEV-A | G-10 | U05876 |

| CV-A17 | HEV-C | G-12 | AF499639 |

| CV-A19 | HEV-C | 8663 | AF499641 |

| CV-A20 | HEV-C | IH-35 | AF499642 |

| CV-A21 | HEV-C | Coe | D00538 |

| CV-A22 | HEV-C | Chulman | AF499643 |

| CV-A24 | HEV-C | EH24/70 | D90457 |

| CV-B1 | HEV-B | Conn-5 | M16560 |

| CV-B2 | HEV-B | Ohio | AF081485 |

| CV-B3 | HEV-B | Nancy | M88483 |

| CV-B4 | HEV-B | JVB | X05690 |

| CV-B5 | HEV-B | Faulkner | AF114383 |

| CV-B6 | HEV-B | Schmitt | AF039205 |

| E-1 | HEV-B | Farouk | AF029859 |

| E-2 | HEV-B | Cornelis | AY302545 |

| E-3 | HEV-B | Morrisey | AY302553 |

| E-4 | HEV-B | Pesacek | AY302557 |

| E-5 | HEV-B | Noyce | AF083069 |

| E-6 | HEV-B | D'Amori | AY302558 |

| E-7 | HEV-B | Wallace | AY036579 |

| E-9 | HEV-B | Hill | X84981 |

| E-11 | HEV-B | Gregory | X80059 |

| E-12 | HEV-B | Travis | X79047 |

| E-13 | HEV-B | Del Carmen | AY302539 |

| E-14 | HEV-B | Tow | AY302540 |

| E-15 | HEV-B | CH 96-51 | AY302541 |

| E-16 | HEV-B | Harrington | AY302542 |

| E-17 | HEV-B | CHHHE-29 | AY302543 |

| E-18 | HEV-B | Metcalf | AF317694 |

| E-19 | HEV-B | Burke | AY302544 |

| E-20 | HEV-B | JV-1 | AY302546 |

| E-21 | HEV-B | Farina | AY302547 |

| E-24 | HEV-B | DeCamp | AY302548 |

| E-25 | HEV-B | JV-4 | AY302549 |

| E-26 | HEV-B | Coronel | AY302550 |

| E-27 | HEV-B | Bacon | AY302551 |

| E-29 | HEV-B | JV-10 | AY302552 |

| E-30 | HEV-B | Bastianni | AF162711 |

| E-31 | HEV-B | Caldwell | AY302554 |

| E-32 | HEV-B | PR-10 | AY302555 |

| E-33 | HEV-B | Toluca-3 | AY302556 |

| EV-68 | HEV-D | Fermon | AY426531 |

| EV-69 | HEV-B | Toluca-1 | AY302560 |

| EV-70 | HEV-D | J670/71 | D00820 |

| EV-71 | HEV-A | BrCr | U22521 |

| EV-73 | HEV-B | CA55-1988 | AF241359 |

| EV-74 | HEV-B | USA/CA75-10213 | AY556057 |

| EV-75 | HEV-B | USA/OK85-10362 | AY556070 |

| EV-76 | HEV-A | AY697458 | |

| EV-77 | HEV-B | CF496-99 | AJ493062 |

| EV-78 | HEV-B | AY208120 |

According to Stanway et al. (36).

The specificity of the VP2 method was tested by using a clinical isolate of rhinovirus (strain 1789).

Virus isolation of field isolates and typing by neutralization.

The typing method was applied to 104 strains of HEV isolated from clinical samples sent to the Virology Unit of the University Hospital of Saint-Etienne (France) from 1977 to 2006 and to 12 strains of HEV recovered from environmental samples at the Faculty of Pharmacy of Monastir (Tunisia) from 1995 to 1997. The isolation technique was performed in both laboratories according to standard protocols as previously described (4, 40). Once the enteroviral cytopathic effect involved more than 50% of the cell monolayer, the cells were scraped and an indirect immunofluorescence assay using the panenterovirus monoclonal antibody 5-D8/1 (DakoCytomation, Trappes, France) was performed to confirm the identification at the genus level (40). The titer of each cell culture supernatant was first determined, and then the neutralization assay was performed in 96-well tissue culture plates by using A to H and, in case of failure, J to P Lim-Benyesh Melnick intersecting pools of hyperimmune horse sera (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) against 100 50% tissue culture infective doses of each isolate as previously described (18). A further identification was performed using a monovalent horse antiserum corresponding to the serotype identified by the intersecting pools (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark). HEV isolates that failed to be identified by this standard seroneutralization procedure were qualified as “untypeable” strains.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription.

Viral RNA was extracted from 140 μl of cell culture supernatant using a QIAamp viral RNA mini kit (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Ten microliters of extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA at 42°C for 45 min using 200 units of SuperScriptIII reverse transcriptase and 2.5 ng/μl of random primers (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France) in the presence of 10 units of RnaseOUT recombinant RNase inhibitor (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France).

Amplification experiments. (i) General precautions and conditions.

To prevent the occurrence of amplicon contamination, the different steps of the PCR assays (extraction, mixture preparation, amplification, purification, and revealing of PCR products) were performed in separate rooms, gloves and masks were worn during the critical steps, and negative controls consisting of water samples were included in all experiments, according to the standard guidelines for molecular biology.

All the amplification experiments were performed in a Mastercycler gradient thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The PCR products were revealed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

(ii) 5′ UTR.

The presence of enteroviral RNA in the field isolates was systematically confirmed by a PCR test in the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR). The cDNA was amplified by using 10 pmol of the primers (Table 2) described by Zoll et al. (41) and 1.25 U of recombinant Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France) in 50 μl of reaction mixture. A band of the expected size of 152 bp (in reference to the PV-1 sequence, GenBank accession no. V01149) was observed.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Region | Primer | Orientation | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Positionb | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ UTR | NC1 | Sense | CTCCGGCCCCTGAATGCG | 445-462 | 41 |

| E2 | Antisense | ATTGTCACCATAAGCAGCCA | 596-577 | 41 | |

| VP1 | 292 | Sense | MIGCIGYIGARACNGG | 2613-2628 | 31 |

| 222 | Antisense | CICCIGGIGGIAYRWACAT | 2969-2951 | 31 | |

| VP2 | AM11 | Sense | GARGCITGYGGITAYAGYGA | 962-981 | This study |

| AM12 | Sense | GARGARTGYGGITAYAGYGA | 962-981 | This study | |

| AM21 | Sense | GGITGGTGGTGGAARYTICC | 1178-1197 | This study | |

| AM22 | Sense | GGITGGTAYTGGAARTTICC | 1178-1197 | This study | |

| AM31 | Antisense | TTDATDATYTGRTGIGG | 1545-1529 | This study | |

| AM32 | Antisense | TTDATCCAYTGRTGIGG | 1545-1529 | This study |

The following standard ambiguity codes were used: D = G, A, or T; R = A or G; Y = T or C; N = A, T, C, or G; M = A or C; and I = deoxyinosine.

With reference to the sequence of PV-1.

(iii) VP1 region.

Five microliters of cDNA was amplified using 50 pmol of the 292 and 222 primers (Table 2) and 1.25 units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France) in 50 μl of reaction mixture, according to the protocol described by Oberste et al. (31). A band of the expected size of 357 bp (with reference to PV-1) was observed after agarose gel electrophoresis.

(iv) VP2 region.

A mixture of two pairs of sense (AM11 and AM12) and antisense (AM31 and AM32) primers (Table 2) was used for the first run of PCR. Five microliters of cDNA was amplified using 80 pmol of each primer and 1.25 units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase in 50 μl of reaction mixture (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France). Amplification included an initial cycle of 95°C for 5 min; 40 further cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 48°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s; and a final extension cycle at 72°C for 5 min. A band of the expected size of 584 bp (with reference to PV-1) was observed after electrophoresis in an agarose gel. For PV, the annealing temperature was lowered to 42°C.

In case of failure of this first PCR, a seminested amplification was performed using 2 μl of the first PCR mixture, a mixture of two pairs of sense (AM21 and AM22) and antisense (AM31 and AM32) primers (40 pmol each) (Table 2), and 1.25 units of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase in 50 μl of reaction mixture (Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France). Amplification included an initial cycle of 95°C for 5 min; 30 further cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 56°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s; and a final extension cycle at 72°C for 5 min. A band of the expected size of 368 bp (with reference to PV-1) was observed after electrophoresis in an agarose gel.

Template purification and sequencing.

The amplicons were purified using Montage PCR centrifugal filter devices (Millipore) or a Qiaquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN, Courtaboeuf, France), depending on the presence of single or multiple bands, respectively. The purified products were sequenced using 0.5 pmol/μl of primer and the GenomeLab Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Quick Start kit (Beckman Coulter, Villepinte, France) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequencing primers were those used in the seminested PCR assay described for the VP2 region and 292/222 for the VP1 region (Table 2). The electrophoresis and analysis of DNA sequence reactions were performed with the automated DNA sequencer CEQ8000 (Beckman Coulter, Villepinte, France).

Sequence analysis and phylogeny.

To determine the enterovirus type, the obtained consensus sequences of 357 bp for VP1 and 368 bp for VP2 were compared to all the corresponding HEV sequences available in GenBank for each region by using BLAST software (1). As proposed by Oberste et al. (22), nucleotide sequence homology of at least 75% was required for assignment to the same serotype. The prototype with the highest identity score calculated with FASTA software (33) was concluded to be the strongest candidate for identification.

Sequence alignments were performed by using the Clustal W program (version 1.81) (39). Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA 3.1 (15). Genetic distances were calculated using the Tamura-Nei method (37), and phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method (35) with 1,000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates (12).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences described in the present report are available in the GenBank database under accession numbers DQ869680 to DQ869857.

RESULTS

Phylogenic analysis of the VP2 coding region, design of primers, and PCR strategy.

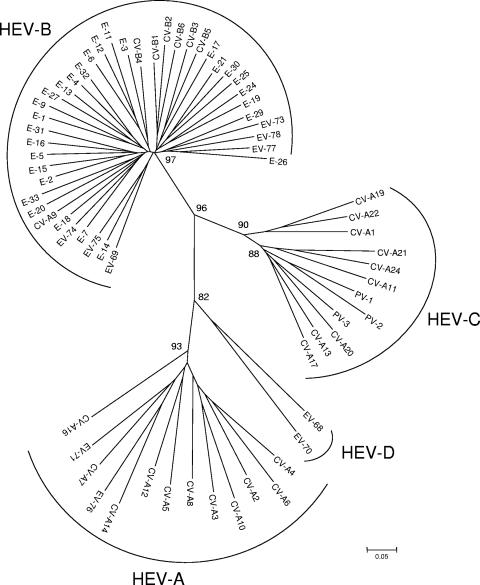

The VP2 coding regions of the 68 prototypes strains (Table 1) were aligned using Clustal W software. The region between nucleotides 1178 and 1545 (with reference to PV-1) was chosen for its high variability between strains. As shown in Fig. 1, all 68 prototype strains of HEV were clustered into the four species HEV-A, -B, -C, and -D; the three PV serotypes were found to be close to HEV-C, as previously described after VP1 analysis.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree depicting the relationships among the 68 prototype strains of HEV serotypes listed in Table 1 and based on the alignment by Clustal W of the central part (nucleotides 1178 to 1545, with reference to PV-1) of the VP2 coding region. The tree was constructed using MEGA 3.1 software according to the neighbor-joining method. Only bootstrap values over 70 are shown.

Two pairs of sense (AM11/AM12) and antisense (AM31/AM32) primers were designed to allow the amplification of the N-terminal and central parts of the VP2 coding regions (584 bp with reference to PV-1) of all the serotypes of HEV (Table 2). For most strains, the optimal annealing temperature of the PCR was 48°C; however, for PV strains, it was lowered to 42°C. A few strains needed a second round of amplification by a seminested PCR assay (368 bp with reference to PV-1) with antisense primers (AM31/AM32) and an internal pair of primers (AM21/AM22) (Table 2). The sensitivities of the test, as evaluated on three clinical isolates belonging to different serotypes (CV-B4, E-6, and E-11), were shown to be approximately 10−1 and 10−4 50% tissue culture infective dose per reaction tube for the first and seminested PCR assays, respectively.

For all the sequence and phylogenetic analyses, only the central part of VP2, corresponding to a 368-bp fragment of PV-1, was taken into consideration because of its high variability among HEV strains (Fig. 1).

Typing of well-characterized strains of HEV by VP2 sequencing.

A total of 61 field isolates, most of them belonging to the HEV-B species, were selected because of their previous identification at the serotype level by a seroneutralization test. The VP2 regions of all the strains were successfully amplified by using the two pairs of primers AM11/AM12 and AM31/AM32. As shown in Table 3, total concordance was observed between seroneutralization and VP2 sequencing for the determination of HEV serotypes. Thirteen of these isolates were also typed by the VP1 sequencing assay with identical results. With the exception of four strains (two typed E-11, one E-14, and another CV-A21), all the strains in Table 3 exhibited a highest identity score of more than 75% and a second-highest score of less than 75% with regard to the respective prototype strains. For the amino acid sequence, the homology was at least 84% with the closest prototype for all the tested strains (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparative results between neutralization and VP2 sequencing for typing field isolates of HEV

| Isolate | Yr of isolation | Sample materiala | Neutralization by intersecting pools of hyperimmune antisera | First highest-score prototype in VP2

|

Second highest-score prototype in VP2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | % Nucleotide identity | % Amino acid identity | Type | % Nucleotide identity | Type | % Amino acid identity | ||||

| SE-81-3363 | 1981 | ? | CV-A9 | CV-A9 | 82.7 | 93.1 | E-24 | 73.9 | E-30 | 76.2 |

| MO-98-86 | 1998 | Sewage | CV-A9 | CV-A9 | 82.1 | 90.3 | E-24 | 72.9 | E-30 | 73.0 |

| MO-98-141 | 1998 | Sewage | CV-A9 | CV-A9 | 83.0 | 93.2 | E-24 | 73.9 | E-30 | 75.9 |

| SE-01-58710 | 2001 | Saliva | CV-A9 | CV-A9 | 82.8 | 93.2 | E-24 | 73.9 | E-30 | 75.9 |

| SE-05-20257b | 2005 | Stool | CV-A9 | CV-A9 | 78.1 | 91.4 | E-13 | 71.2 | E-30 | 76.1 |

| SE-89-5145 | 1989 | ? | CV-B1 | CV-B1 | 79.8 | 93.2 | CV-B4 | 72.4 | CBV-3 | 79.8 |

| SE-02-71582 | 2002 | CSF | CV-B1 | CV-B1 | 80.8 | 94.3 | CV-B4 | 74.5 | CBV-3 | 80.3 |

| SE-02-70595 | 2002 | Stool | CV-B1 | CV-B1 | 80.8 | 93.4 | CV-B3 | 73.0 | CBV-3 | 79.4 |

| SE-02-71028 | 2002 | CSF | CV-B1 | CV-B1 | 81.1 | 94.3 | CV-B4 | 74.2 | CBV-3 | 80.3 |

| SE-04-12537 | 2004 | Stool | CV-B2 | CV-B2 | 81.4 | 92.1 | CV-B1 | 70.2 | CBV-4 | 74.5 |

| SE-01-59691 | 2001 | Stool | CV-B2 | CV-B2 | 84.9 | 94.2 | CV-B1 | 71.2 | CBV-4 | 75.0 |

| SE-98-82668 | 1998 | Stool | CV-B2 | CV-B2 | 84.5 | 96.2 | CV-B1 | 72.4 | CBV-4 | 77.5 |

| SE-02-72206b | 2002 | Throat | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 81.6 | 96.2 | CV-B1 | 68.6 | CBV-1 | 76.6 |

| SE-03-78384b | 2003 | Stool | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 81.5 | 96.2 | E-29 | 69.8 | CBV-1 | 76.4 |

| SE-03-78350b | 2003 | Stool | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 82.1 | 96.0 | E-29 | 70.1 | CBV-1 | 75.2 |

| SE-05-23233b | 2005 | Stool | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 80.2 | 96.2 | CV-B4 | 70.0 | CBV-1 | 76.4 |

| SE-05-23218b | 2005 | Nose | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 80.3 | 96.2 | CV-B1 | 69.2 | CBV-1 | 76.8 |

| SE-05-23212b | 2005 | Throat | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 80.6 | 96.0 | CV-B4 | 70.2 | CBV-1 | 76.4 |

| SE-94-51301 | 1994 | Stool | CV-B3 | CV-B3 | 81.5 | 95.0 | CV-B1 | 70.0 | CBV-1 | 78.4 |

| SE-03-78346b | 2003 | Stool | CV-B4 | CV-B4 | 83.1 | 99.0 | CV-B1 | 72.4 | CBV-2 | 77.7 |

| SE-04-84828 | 2004 | Stool | CV-B4 | CV-B4 | 80.7 | 98.0 | CV-B1 | 72.4 | CBV-2 | 77.7 |

| SE-04-85460 | 2004 | Stool | CV-B4 | CV-B4 | 80.1 | 96.2 | E-12 | 71.5 | CBV-2 | 76.1 |

| MO-98-74 | 1998 | Sewage | CV-B5 | CV-B5 | 77.2 | 93.2 | E-11 | 71.3 | CV-B4 | 75.7 |

| SE-03-78505b | 2003 | Stool | CV-B5 | CV-B5 | 81.2 | 93.8 | E-25 | 70.5 | CBV-4 | 76.5 |

| SE-03-78619b | 2003 | Stool | CV-B5 | CV-B5 | 80.8 | 94.2 | E-25 | 70.7 | CBV-4 | 78.8 |

| SE-03-79895 | 2003 | Stool | CV-B5 | CV-B5 | 80.7 | 93.2 | CV-B4 | 72.5 | CBV-4 | 78.6 |

| SE-88-11044 | 1988 | ? | E-3 | E-3 | 83.2 | 99.0 | E-7 | 73.2 | E-12 | 80.5 |

| MO-95-130 | 1995 | Sewage | E-3 | E-3 | 82.4 | 99.0 | E-7 | 72.7 | E-12 | 80.7 |

| SE-86-8934 | 1986 | ? | E-4 | E-4 | 82.4 | 93.2 | E-32 | 73.3 | E-1 | 76.9 |

| SE-84-4559 | 1984 | ? | E-6 | E-6 | 99.6 | 99.0 | E-11 | 72.0 | E-29 | 80.0 |

| SE-02-70337 | 2002 | Stool | E-6 | E-6 | 80.0 | 95.9 | E-31 | 73.7 | E-29 | 79.5 |

| SE-85-4680 | 1985 | ? | E-7 | E-7 | 78.2 | 94.2 | E-32 | 72.9 | E-32 | 85.7 |

| SE-83-3808 | 1983 | ? | E-9 | E-9 | 80.3 | 94.2 | E-7 | 71.1 | E-11 | 76.1 |

| SE-03-81103 | 2003 | Stool | E-9 | E-9 | 80.5 | 93.3 | E-13 | 71.3 | E-11 | 76.1 |

| SE-04-22413 | 2004 | Stool | E-9 | E-9 | 80.3 | 93.2 | E-13 | 71.3 | E-11 | 75.7 |

| SE-87-3289 | 1987 | ? | E-11 | E-11 | 75.1 | 89.2 | E-19 | 74.0 | E-19 | 84.3 |

| MO-95-38 | 1995 | Sewage | E-11 | E-11 | 76.2 | 87.3 | E-19 | 73.3 | E-19 | 80.5 |

| MO-96-75 | 1996 | Sewage | E-11 | E-11 | 74.6 | 86.4 | E-19 | 73.0 | E-19 | 79.6 |

| MO-97-135 | 1997 | Sewage | E-11 | E-11 | 75.5 | 87.7 | E-19 | 71.7 | E-19 | 79.2 |

| SE-02-70530 | 2002 | Stool | E-11 | E-11 | 74.5 | 84.3 | E-19 | 74.3 | E-12 | 78.4 |

| SE-00-52798 | 2000 | Stool | E-13 | E-13 | 78.8 | 96.0 | E-27 | 71.7 | EV-69 | 77.4 |

| SE-00-53170 | 2000 | Stool | E-13 | E-13 | 77.0 | 94.2 | E-32 | 71.8 | EV-69 | 78.8 |

| SE-02-71406 | 2002 | Stool | E-14 | E-14 | 79.3 | 96.1 | E-2 | 75.2 | E-2 | 80.9 |

| SE-89-9796 | 1989 | ? | E-17 | E-17 | 79.4 | 94.0 | E-13 | 73.2 | E-7 | 72.5 |

| SE-85-6268 | 1985 | ? | E-18 | E-18 | 81.3 | 94.1 | E-2 | 72.2 | E-32 | 75.2 |

| SE-88-8012 | 1988 | ? | E-20 | E-20 | 83.7 | 97.1 | E-24 | 68.1 | E-24 | 72.1 |

| SE-94-50463b | 1994 | Stool | E-20 | E-20 | 79.3 | 97.1 | EV-73 | 71.3 | E-24 | 73.3 |

| SE-03-78301b | 2003 | Throat | E-20 | E-20 | 80.1 | 92.3 | CV-B6 | 70.3 | E-6 | 72.1 |

| SE-03-78928b | 2003 | Throat | E-20 | E-20 | 78.7 | 90.2 | CV-B6 | 69.2 | E-6 | 70.5 |

| SE-03-79470 | 2003 | Stool | E-20 | E-20 | 80.1 | 92.3 | CV-B6 | 70.3 | E-6 | 72.1 |

| SE-84-4617 | 1984 | ? | E-21 | E-21 | 80.1 | 98.0 | E-30 | 72.8 | E-30 | 78.4 |

| SE-86-7617 | 1986 | ? | E-24 | E-24 | 80.8 | 93.1 | E-19 | 71.4 | E-20 | 73.5 |

| SE-03-78187 | 2003 | Throat | E-25 | E-25 | 78.0 | 95.2 | E-19 | 71.2 | E-29 | 79.0 |

| SE-83-3259 | 1983 | ? | E-29 | E-29 | 81.1 | 94.2 | E-25 | 70.5 | E-6 | 78.0 |

| SE-87-7460 | 1987 | ? | E-30 | E-30 | 85.5 | 96.1 | E-21 | 72.1 | E-21 | 77.6 |

| MO-97-128 | 1997 | Sewage | E-30 | E-30 | 86.6 | 98.0 | E-21 | 72.0 | E-21 | 78.0 |

| SE-99-93442 | 1999 | Throat | E-30 | E-30 | 84.3 | 96.1 | E-25 | 71.3 | E-21 | 78.8 |

| SE-05-15103 | 2005 | Stool | E-30 | E-30 | 87.2 | 98.1 | E-29 | 72.0 | E-21 | 78.5 |

| SE-82-3851 | 1982 | ? | E-33 | E-33 | 79.0 | 88.7 | E-13 | 69.5 | E-12 | 78.5 |

| SE-87-13658 | 1987 | ? | CV-A16 | CV-A16 | 88.7 | 94.0 | CV-A7 | 70.0 | EV-71 | 85.0 |

| SE-88-11568 | 1988 | ? | CV-A21 | CV-A21 | 89.6 | 98.3 | CV-A24 | 75.6 | CV-A24 | 88.5 |

?, sample origin not available.

Strain also typed by VP1 sequencing (with a concordant result in all cases).

In addition, a few prototype strains, including the Sabin vaccine strains of the three PV serotypes, three CV-A strains propagated in suckling mice (CV-A6, CV-13, and CV-A14), and six HEV-B strains (CV-B2, CV-B4, CV-B5, CV-B6, E-2, and E-6) were correctly typed by using the VP2 assay. However, as stated above, the temperature of hybridization of primers in the PCR was lowered to 42°C for the three Sabin PV strains in order to obtain a successful amplification. No amplification was obtained for a field isolate of rhinovirus (data not shown).

Typing by VP1 and VP2 sequencing of “untypeable” strains of HEV.

A total of 55 field isolates were selected because they could not be identified by the intersecting pools of hyperimmune horse antisera: 12 strains exhibited titers too low to be tested by the seroneutralization test, 26 strains could be neutralized retrospectively by using the monovalent antiserum corresponding to the type identified by sequencing assays, and 17 strains failed to be neutralized even by the antiserum-matching molecular typing.

These 55 strains were typed by sequencing both the VP1 and VP2 regions. As shown in Table 4, concordant results were observed for 48 of them (87.3%). For six strains (four identified as EV-71, one as E-9, and one as E-30 by the VP2 method), no amplification was obtained by the VP1 method. The last discordant strain was typed as CV-B4 by the VP1 method and CV-B3 by the VP2 method and monovalent antisera; preliminary results suggest that this strain is a CV-B3/CV-B4 recombinant strain in the capsid region (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Comparative results between VP1 and VP2 sequencing for typing field isolates of HEV not typeable by intersecting pools of hyperimmune horse sera

| Isolate | Yr of isolation | Site or sample materiala | VP2 typing (highest-score prototype)

|

VP1 typingb (highest-score prototype)

|

Neutralization by monovalent antiserumc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | % Nucleotide identity | % Amino acid identity | Type | % Nucleotide identity | % Amino acid identity | ||||

| SE-96-70841 | 1996 | Stool | CV-A9 | 81.3 | 91.4 | CV-A9 | 80.2 | 96.3 | CV-A9 |

| MO-96-63 | 1996 | Sewage | CV-A9 | 81.1 | 91.1 | CV-A9 | 78.9 | 95.3 | CV-A9 |

| SE-00-53763 | 2000 | Stool | CV-A9 | 81.3 | 92.0 | CV-A9 | 80.5 | 95.3 | NA |

| SE-00-53146 | 2000 | Stool | CV-A9 | 82.0 | 93.3 | CV-A9 | 79.2 | 95.7 | NA |

| SE-03-77049 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A9 | 80.6 | 93.2 | CV-A9 | 80.0 | 96.2 | NA |

| SE-99-94869 | 1999 | Stool | CV-B1 | 80.1 | 94.3 | CV-B1 | 76.9 | 92.3 | CV-B1 |

| SE-02-70625 | 2002 | Stool | CV-B1 | 80.0 | 88.6 | CV-B1 | 80.0 | 93.3 | CV-B1 |

| SE-02-70250 | 2002 | Stool | CV-B1 | 79.8 | 93.2 | CV-B1 | 80.0 | 94.1 | CV-B1 |

| SE-96-72087 | 1996 | NPA | CV-B2 | 85.5 | 97.2 | CV-B2 | 80.2 | 99.0 | CV-B2 |

| SE-05-90025 | 2005 | Stool | CV-B2 | 83.2 | 95.3 | CV-B2 | 81.5 | 99.1 | CV-B2 |

| SE-05-90249 | 2005 | Throat | CV-B2 | 82.4 | 92.3 | CV-B2 | 80.4 | 98.1 | CV-B2 |

| SE-03-78616 | 2003 | Stool | CV-B3 | 81.7 | 96.3 | CV-B4 | 82.2 | 99.0 | CV-B3 |

| SE-04-85429 | 2004 | Stool | CV-B4 | 82.2 | 96.1 | CV-B4 | 81.3 | 98.1 | CV-B4 |

| SE-06-70414 | 2006 | NPA | CV-B5 | 79.6 | 92.4 | CV-B5 | 76.1 | 97.2 | CV-B5 |

| SE-99-97363 | 1999 | Stool | E-1 | 75.3 | 91.1 | E-1 | 76.2 | 91.8 | E-1 |

| SE-98-87643 | 1998 | Stool | E-7 | 75.8 | 87.3 | E-7 | 80.7 | 96.3 | No |

| SE-98-85865d | 1998 | Stool | E-7 | 74.2 | 82.8 | E-7 | 76.9 | 92.2 | No |

| SE-04-86919d | 2004 | Throat | E-9 | 80.3 | 93.2 | - | - | - | NA |

| MO-95-29 | 1995 | Sewage | E-11 | 74.3 | 85.5 | E-11 | 76.9 | 88.9 | No |

| MO-96-54 | 1996 | Sewage | E-11 | 75.0 | 87.1 | E-11 | 74.7 | 86.4 | No |

| MO-96-5 | 1996 | Sewage | E-11 | 75.3 | 88.3 | E-11 | 75.0 | 86.7 | No |

| SE-00-53010 | 2000 | NPA | E-13 | 78.9 | 96.1 | E-13 | 79.0 | 94.0 | NA |

| SE-00-60604 | 2006 | NPA | E-13 | 77.8 | 95.1 | E-13 | 79.3 | 93.4 | E-13 |

| SE-98-87927 | 1998 | Stool | E-14 | 80.5 | 95.0 | E-14 | 79.6 | 91.5 | NA |

| SE-99-96858 | 1999 | Stool | E-14 | 79.8 | 96.0 | E-14 | 76.6 | 95.1 | E-14 |

| SE-00-56151 | 2000 | Stool | E-14 | 78.6 | 96.0 | E-14 | 81.6 | 95.3 | No |

| SE-03-79230 | 2003 | Throat | E-16 | 78.9 | 93.3 | E-16 | 82.4 | 99.0 | NA |

| SE-03-79287 | 2003 | Stool | E-16 | 79.0 | 92.3 | E-16 | 81.3 | 97.4 | NA |

| SE-03-79229 | 2003 | Stool | E-16 | 79.1 | 93.3 | E-16 | 81.7 | 98.1 | NA |

| SE-04-83200 | 2004 | Stool | E-16 | 79.8 | 93.5 | E-16 | 83.5 | 99.0 | E-16 |

| SE-99-94960 | 1999 | Throat | E-17 | 80.8 | 97.0 | E-17 | 79.6 | 89.1 | No |

| SE-96-69912 | 1996 | Throat | E-18 | 81.7 | 94.2 | E-18 | 82.4 | 96.0 | NA |

| SE-00-55193 | 2000 | Stool | E-18 | 81.6 | 95.1 | E-18 | 82.2 | 95.3 | No |

| SE-05-10030 | 2005 | Throat | E-18 | 81.1 | 93.2 | E-18 | 82.7 | 95.4 | NA |

| SE-77-193 | 1977 | ? | E-20 | 78.2 | 91.3 | E-20 | 79.2 | 92.5 | E-20 |

| SE-03-78761 | 2003 | Stool | E-20 | 80.3 | 92.2 | E-20 | 78.6 | 91.8 | E-20 |

| SE-97-80688 | 1997 | Stool | E-25 | 82.5 | 97.1 | E-25 | 82.1 | 95.2 | E-25 |

| SE-98-89071 | 1998 | Stool | E-25 | 81.5 | 97.1 | E-25 | 80.5 | 95.2 | E-25 |

| SE-99-90791 | 1999 | Stool | E-25 | 79.5 | 98.0 | E-25 | 79.0 | 87.9 | E-25 |

| SE-03-80646 | 2003 | Stool | E-25 | 80.0 | 96.4 | E-25 | 80.3 | 92.6 | E-25 |

| SE-98-87543 | 1998 | CSF | E-30 | 85.8 | 98.0 | - | - | - | E-30 |

| SE-98-96811 | 1998 | Stool | E-30 | 85.9 | 98.0 | E-30 | 80.8 | 90.7 | E-30 |

| SE-05-50152 | 2005 | Stool | E-30 | 88.2 | 97.8 | E-30 | 81.6 | 91.7 | E-30 |

| SE-98-86832 | 1998 | Stool | CV-A13 | 79.5 | 95.8 | CV-A13 | 76.6 | 92.2 | CV-A13 |

| SE-03-75245 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A13 | 77.7 | 93.3 | CV-A13 | 75.5 | 90.9 | CV-A13 |

| SE-03-78463 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A14 | 84.1 | 97.9 | CV-A14 | 84.9 | 97.9 | No |

| SE-03-78693 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A14 | 84.2 | 95.8 | CV-A14 | 84.3 | 98.0 | No |

| SE-03-77906 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A14 | 85.3 | 98.9 | CV-A14 | 83.9 | 95.0 | No |

| SE-03-78331 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A14 | 83.9 | 95.9 | CV-A14 | 82.8 | 93.2 | No |

| SE-03-77098 | 2003 | Stool | CV-A14 | 84.1 | 97.1 | CV-A14 | 83.6 | 94.0 | No |

| SE-02-69079 | 2002 | Stool | CV-A16 | 73.0 | 94.8 | CV-A16 | 76.8 | 92.1 | NA |

| SE-04-85672 | 2004 | Stool | EV-71 | 80.8 | 100 | - | - | - | No |

| SE-05-18404 | 2005 | NPA | EV-71 | 80.6 | 100 | - | - | - | No |

| SE-00-99676 | 2000 | Stool | EV-71 | 81.9 | 100 | - | - | - | No |

| SE-06-40439 | 2006 | Stool | EV-71 | 82.9 | 100 | - | - | - | No |

NPA, nasopharyngeal aspirate; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

-, no amplification despite at least three different attempts.

Serotype, neutralization with the corresponding antiserum; No, no neutralization with the corresponding monovalent antiserum; NA, not applicable because of the viral titer was too low.

Strain needing a further seminested round to be typed.

As shown in Table 4, both typing methods exhibited highest nucleotide and amino acid identity scores of more than 75% and 85%, respectively, for all but four of the tested strains (one typed E-7, one E-11, and another CV-A16 by the VP2 method and one typed E-11 by the VP1 method); of note, three of these strains were not neutralized by the corresponding monovalent antiserum.

Only two strains (SE-98-85865/E-7 and SE-04-86919/E-9 in Table 4) needed to be amplified by seminested PCR before being sequenced.

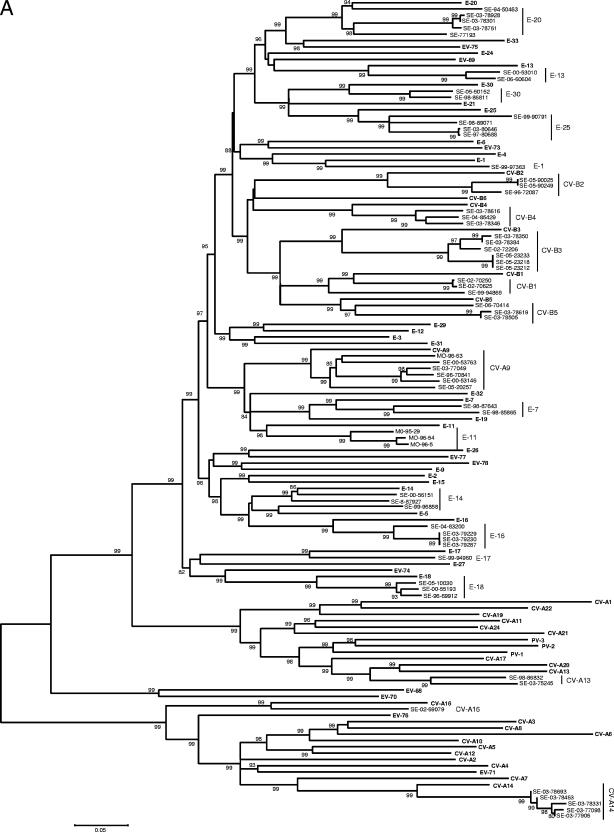

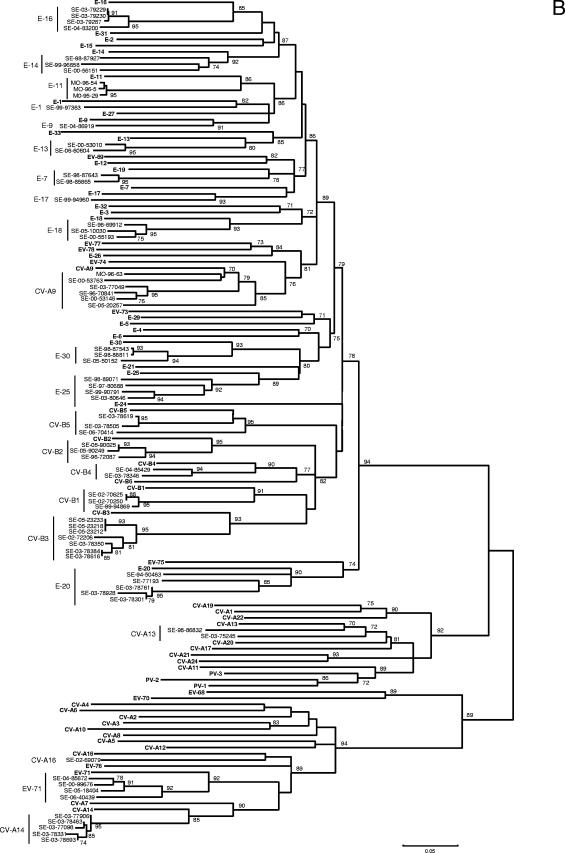

Using Clustal W, the sequences of prototype and tested field strains were combined to construct a phylogenetic tree for each of the VP1 and VP2 regions. As shown in Fig. 2, despite higher bootstrap values for VP1, the two phylogenies gave very close results. All the field strains were clustered with their corresponding prototype, with the exception of one strain of E-14 grouped with the E-5 prototype in the VP1 tree and two strains of E-7 grouped with the E-19 prototype in the VP2 tree.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic trees depicting the relationships among HEV serotypes based on alignment by Clustal W of (A) VP1 and (B) VP2 coding regions of the 68 prototype strains of HEV listed in Table 1 (boldface) and of the field strains of this study typed in both regions. The trees were constructed according to the neighbor-joining method using MEGA 3.1 software. Only bootstrap values over 70 are shown.

DISCUSSION

While serotyping of HEV has no significant impact on the clinical management of patients, identification at the serotype level is important for several reasons: (i) in the context of worldwide polio eradication, it is essential to develop tools able to delineate polio and nonpolio HEV; (ii) from the epidemiological point of view, it is important to identify which serotype is responsible for clusters of cases, especially when large outbreaks (i.e., EV-70 or CV-A24 and epidemic hemorrhagic conjunctivitis) or severe clinical conditions (i.e., EV-71 and fatal neurological disease) occur; (iii) as with all RNA viruses, HEV serotypes display a high potential for genetic diversity that requires powerful molecular tools to detect variants, recombinants, and newly emerging serotypes (26).

Molecular methods are now recognized as alternative techniques to seroneutralization for modern serotyping of HEV (22). Because VP1 contains most of the neutralizing epitopes, the sequencing of a part of this coding region is not far from being considered the gold standard (7, 20, 24, 25). The study of Casas et al. (8) showed that sequencing of the VP1 coding region was a more discriminant technique for HEV typing than analysis of a part of the VP2 coding region or of the polymerase gene. However, recent studies have shown that VP1-based sequencing methods could fail to amplify some E and CV strains (5, 13, 14). In addition, primers targeting the VP1 region and designed to amplify all the HEV serotypes did not recognize some serotypes not belonging to the HEV-B species (i.e., EV-68, EV-70, and EV-71) because of some mismatch; to circumvent this problem, Oberste et al. (28) recently proposed a first round of amplification using primers located within the 3′ UTR in order to identify the strain at the species level, followed by a second PCR assay using species-specific primers that allow a proper identification at the serotype level.

In this report, we propose a new strategy for typing HEV using a sequencing assay based on primers targeting the VP2 region. This region had previously been recommended for typing purposes (2, 9, 34). In contrast to other studies that amplified different fragments of the N-terminal part of the VP2 coding region (8, 16, 27), which is not highly divergent in HEV serotypes, the technique described here focused on a 368-bp fragment (with reference to PV-1) of the central part of VP2 that was found to be able to segregate correctly all the serotypes of HEV (Fig. 1) in relation to the presence in this region of neutralizing epitopes, particularly the EF loop (17). This structure, constituted of approximately 50 amino acids in the center of VP2, is characterized by high variability among HEV and is probably responsible for a great part of the discriminatory power of this typing method.

All the prototype and field strains that were evaluated could be typed successfully by the VP2 assay with good confidence (the percent nucleotide homology was ≥75% [Tables 3 and 4]), with the exception of one E-7, three E-11, and one CV-A16 strains, which were shown to be slightly more distant from the prototype strain although they were correctly typed, probably because of the high evolution rate of these serotypes compared to others. Actually, the cutoff of 75% for delineating a serotype is not an absolute limit, as previously exemplified by using the VP1 typing assay, which showed nucleotide divergences of up to 27% for E-11 (30) and E-30 (23) strains. Consequently, for strains that do not reach the 75% nucleotide homology with the prototype strain exhibiting the first highest score in the VP2 typing assay, we propose to retain the identification as the more probable and to confirm the result by measuring sequence homology with other strains belonging to the same serotype.

Only 36 of the 68 serotypes of HEV were tested, most of them belonging to the HEV-B species, which corresponds to the isolates most frequently recovered in clinical virology. Serotypes of the HEV-D species (EV-68 and EV-70), as well as newly described serotypes of HEV (EV-74 to -78) (21, 26, 29), were not available, but the primers described here matched perfectly with their published sequences (Fig. 1). Concerning the Sabin PV strains, it must be stressed that the hybridization temperature of primers should be lowered to 42°C to obtain an efficient rate of amplification, despite the risk of enhancing nonspecific reactions. Further controls on wild isolates of PV are needed to control this effect.

Globally, the following strategy could be evaluated in case of unsuccessful amplification with the standard VP2 assay described here: either use seminested amplification in order to increase the sensitivity of the typing method or lower the temperature of the hybridization step to 42°C if the epidemiological context is compatible with a PV isolate.

The VP2 typing assay described here was shown to exhibit at least three interesting features compared to previously described methods spanning other regions of the HEV genome: (i) the use of a pair of primers with a limited number of degenerate positions allowed the correct identification of four untypeable strains of EV-71 that were not recognized by the VP1 primers described by Oberste et al. (31), probably because of a mismatch (T/C) with primer 292 at position 2593 (according to prototype strain EV-71, accession no. U22521); (ii) the ability to perform a seminested PCR assay for a few strains exhibiting low infectious titers enhances the sensitivity of the typing method, as exemplified by strain SE-04-86919, which was nontypeable by neutralization and VP1 assays but was typed as E-9 by VP2 (Table 4 and Fig. 2); (iii) the discrepant typing results obtained for strain SE-03-78616 (CV-B4 by VP1 and CV-B3 by VP2 and monovalent antiserum) (Table 4) illustrate the interest of combining different typing methods to identify interserotypic recombinants in the capsid region. Strain SE-98-87543, which exhibited a correct infectious titer and was typed E-30 by VP2 and neutralized by the E-30 monovalent antiserum but was not typed by VP1, could represent another recombinant strain in the capsid region.

In conclusion, the VP2 assay described in this study is proposed as an additional tool for typing HEV strains on a routine basis. Since most strains were shown to be typed by using a single round of PCR with two pairs of primers, this method could be used as a screening test for the typing of field isolates. Further experiments on a wider spectrum of strains are needed to verify its ability to actually identify most HEV strains. In addition, the seminested version of the test should be evaluated for its capacity to directly type HEV in clinical samples without using the cell culture step, as previously suggested for other regions (8, 11).

Acknowledgments

Dorsaf Nasri is supported by funds from the “Comité Mixte de Coopération Universitaire (CMCU) Franco-Tunisien” (program no. 03S0804) and the Doctoral School of Monastir.

Jean-Luc Bailly, Christophe Ginevra, Florence Grattard, and Philip Lawrence are acknowledged for helpful discussions of phylogenetic studies. The technical assistance of Nelly Bonnet was appreciated.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arola, A., J. Santti, O. Ruuskanen, P. Halonen, and T. Hyypia. 1996. Identification of enteroviruses in clinical specimens by competitive PCR followed by genetic typing using sequence analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:313-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailly, J. L., A. Beguet, M. Chambon, C. Henquell, and H. Peigue-Lafeuille. 2000. Nosocomial transmission of echovirus 30: molecular evidence by phylogenetic analysis of the VP1 encoding sequence. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2889-2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belguith, K., A. Hassen, and M. Aouni. 2006. Comparative study of four extraction methods for enterovirus recovery from wastewater and sewage sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 97:414-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolanaki, E., C. Kottaridi, P. Markoulatos, L. Margaritis, and T. Katsorchis. 2005. A comparative amplification of five different genomic regions on Coxsackie A and B viruses. Implications in clinical diagnostics. Mol. Cell Probes 19:127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown, B., M. S. Oberste, K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Complete genomic sequencing shows that polioviruses and members of human enterovirus species C are closely related in the noncapsid coding region. J. Virol. 77:8973-8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caro, V., S. Guillot, F. Delpeyroux, and R. Crainic. 2001. Molecular strategy for “serotyping” of human enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 82:79-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casas, I., G. F. Palacios, G. Trallero, D. Cisterna, M. C. Freire, and A. Tenorio. 2001. Molecular characterization of human enteroviruses in clinical samples: comparison between VP2, VP1, and RNA polymerase regions using RT nested PCR assays and direct sequencing of products. J. Med. Virol. 65:138-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyypia, T., T. Hovi, N. J. Knowles, and G. Stanway. 1997. Classification of enteroviruses based on molecular and biological properties. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishiko, H., Y. Shimada, M. Yonaha, O. Hashimoto, A. Hayashi, K. Sakae, and N. Takeda. 2002. Molecular diagnosis of human enteroviruses by phylogeny-based classification by use of the VP4 sequence. J. Infect. Dis. 185:744-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iturriza-Gomara, M., B. Megson, and J. Gray. 2006. Molecular detection and characterization of human enteroviruses directly from clinical samples using RT-PCR and DNA sequencing. J. Med. Virol. 78:243-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura, M. 1980. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 16:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kottaridi, C., E. Bolanaki, and P. Markoulatos. 2004. Amplification of echoviruses genomic regions by different RT-PCR protocols—a comparative study. Mol. Cell Probes 18:263-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kottaridi, C., E. Bolanaki, N. Siafakas, and P. Markoulatos. 2005. Evaluation of seroneutralization and molecular diagnostic methods for echovirus identification. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 53:113-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manzara, S., M. Muscillo, G. La Rosa, C. Marianelli, P. Cattani, and G. Fadda. 2002. Molecular identification and typing of enteroviruses isolated from clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4554-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mateu, M. G. 1995. Antibody recognition of picornaviruses and escape from neutralization: a structural view. Virus Res. 38:1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melnick, J. L., and I. L. Wimberly. 1985. Lyophilized combination pools of enterovirus equine antisera: new LBM pools prepared from reserves of antisera stored frozen for two decades. Bull. W. H. O. 63:543-550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muir, P., U. Kämmerer, K. Korn, M. N. Mulders, T. Pöyry, B. Weissbrich, R. Kandolf, G. M. Cleator, and A. M. van Loon for The European Union Concerted Action on Virus Meningitis and Encephalitis. 1998. Molecular typing of enteroviruses: current status and future requirements. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:202-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norder, H., L. Bjerregaard, and L. O. Magnius. 2001. Homotypic echoviruses share aminoterminal VP1 sequence homology applicable for typing. J. Med. Virol. 63:35-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norder, H., L. Bjerregaard, L. O. Magnius, B. Lina, M. Aymard, and J. J. Chomel. 2003. Sequencing of “untypable” enteroviruses reveals two new types, EV-77 and EV-78, within human enterovirus type B and substitutions in the BC loop of the VP1 protein for known types. J. Gen. Virol. 84:827-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, M. R. Flemister, G. Marchetti, D. R. Kilpatrick, and M. A. Pallansch. 2000. Comparison of classic and molecular approaches for the identification of untypeable enterovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1170-1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, M. L. Kennett, J. J. Campbell, M. S. Carpenter, D. Schnurr, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of echovirus type 30 (E30): genotypes correlate with temporal dynamics of E30 isolation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3928-3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, D. R. Kilpatrick, M. R. Flemister, B. A. Brown, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Typing of human enterovirus by partial sequencing of VP1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1288-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, D. R. Kilpatrick, and M. A. Pallansch. 1999. Molecular evolution of the human enteroviruses: correlation of serotype with VP1 sequence and application to picornavirus classification. J. Virol. 73:1941-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, S. M. Michele, G. Belliot, M. Uddin, and M. A. Pallansch. 2005. Enteroviruses 76, 89, 90 and 91 represent a novel group within the species Human enterovirus A. J. Gen. Virol. 86:445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 1998. Molecular phylogeny of all human enterovirus serotypes based on comparison of sequences at the 5′ end of the region encoding VP2. Virus Res. 58:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oberste, M. S., K. Maher, A. J. Williams, N. Dybdahl-Sissoko, B. A. Brown, M. S. Gookin, S. Penaranda, N. Mishrik, M. Uddin, and M. A. Pallansch. 2006. Species-specific RT-PCR amplification of human enteroviruses: a tool for rapid species identification of uncharacterized enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 87:119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberste, M. S., S. M. Michele, K. Maher, D. Schnurr, D. Cisterna, N. Junttila, M. Uddin, J. J. Chomel, C. S. Lau, W. Ridha, S. al-Busaidy, H. Norder, L. O. Magnius, and M. A. Pallansch. 2004. Molecular identification and characterization of two proposed new enterovirus serotypes, EV74 and EV75. J. Gen. Virol. 85:3205-3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberste, M. S., W. A. Nix, D. R. Kilpatrick, M. R. Flemister, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Molecular epidemiology and type-specific detection of echovirus 11 isolates from the Americas, Europe, Africa, Australia, Southern Asia and the Middle East. Virus Res. 91:241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oberste, M. S., W. A. Nix, K. Maher, and M. A. Pallansch. 2003. Improved molecular identification of enteroviruses by RT-PCR and amplicon sequencing. J. Clin. Virol. 26:375-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pallansch, M. A., and R. Roos. 2007. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxsackie viruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p. 839-893. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 1. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson, W. R., and D. J. Lipman. 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:2444-2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poyry, T., L. Kinnunen, T. Hyypia, B. A. Brown, C. Horsnell, T. Hovi, and G. Stanway. 1996. Genetic and phylogenetic clustering of enteroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 77:1699-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanway, G., F. Brown, and P. Christian. 2005. Picornaviridae, p. 757-778. In C. M. Fauquet, M. A. Mayo, J. Maniloff, U. Desselberger, and L. A. Ball (ed.), Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Eighth report of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 37.Tamura, K., and M. Nei. 1993. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 10:512-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoelen, I., P. Lemey, I. Van der Donck, K. Beuselinck, A. M. Lindberg, and M. Van Ranst. 2003. Molecular typing and epidemiology of enteroviruses identified from an outbreak of aseptic meningitis in Belgium during the summer of 2000. J. Med. Virol. 70:420-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trabelsi, A., F. Grattard, M. Nejmeddine, M. Aouni, T. Bourlet, and B. Pozzetto. 1995. Evaluation of an enterovirus group-specific anti-VP1 monoclonal antibody, 5-D8/1, in comparison with neutralization and PCR for rapid identification of enteroviruses in cell culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2454-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zoll, G. J., W. J. Melchers, H. Kopecka, G. Jambroes, H. J. van der Poel, and J. M. Galama. 1992. General primer-mediated polymerase chain reaction for detection of enteroviruses: application for diagnostic routine and persistent infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:160-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]