Abstract

Generation of infectious arenavirus-like particles requires the virus RING finger Z protein and surface glycoprotein precursor (GPC) and the correct processing of GPC into GP1, GP2, and a stable signal peptide (SSP). Z is the driving force of arenavirus budding, whereas the GP complex (GPc), consisting of hetero-oligomers of SSP, GP1, and GP2, forms the viral envelope spikes that mediate receptor recognition and cell entry. Based on the roles played by Z and GP in the arenavirus life cycle, we hypothesized that Z and the GPc should interact in a manner required for virion formation. Here, using confocal microscopy and coimmunoprecipitation assays, we provide evidence for subcellular colocalization and biochemical interaction, respectively, of Z and the GPc. Our results from mutation-function analysis reveal that Z myristoylation, but not the Z late (L) or RING domain, is required for Z-GPc interaction. Moreover, Z interacted directly with SSP in the absence of other components of the GPc. We obtained similar results with Z and GPC from the prototypical arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and the hemorrhagic fever arenavirus Lassa fever virus.

Arenaviruses merit significant attention, both as tractable model systems with which to study acute and persistent viral infections (36, 51) and as clinically important human pathogens including Lassa fever virus (LFV) and several New World arenaviruses which cause severe hemorrhagic fever (HF) (17, 28, 40).

The prototypical Arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is a formidable workhorse for the study of virus-host interactions associated with both acute infection and viral persistence (14, 36). In addition, evidence indicates that LCMV might be a neglected human pathogen of clinical significance, especially in cases of congenital infection (3, 20, 30). No licensed anti-arenavirus vaccines are available, and current anti-arenavirus therapies are limited to the use of ribavirin, which is only partially effective and often associated with negative side effects such as anemia and birth defects (29). Therefore, it is important to develop novel, effective antiviral strategies to combat arenaviruses. This task will be facilitated by a better understanding of the interactions among viral polypeptides required for assembly of infectious virions.

Arenaviruses are enveloped viruses with a bisegmented, single-stranded, negative sense (NS) RNA genome (8). Each of the two segments uses an ambisense coding strategy to direct the synthesis of two polypeptides. The large segment (L segment, 7.2 kb) encodes the small RING finger Z protein and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase L protein, while the small segment (S segment, 3.4 kb) encodes the nucleoprotein (NP) and the glycoprotein precursor (GPC). Posttranslational cleavage of GPC generates the three components that form the GP complex (GPc): the stable signal peptide (SSP; 58 amino acids), GP1 (40 to 46 kDa), and GP2 (35 kDa) (9, 15, 50). GP2 contains a transmembrane domain and a short cytoplasmic domain (CTD), while GP1 has no known association with the plasma membrane and binds GP2 via electrostatic interactions (10, 34). The arenavirus SSP is unique in that it remains stably associated with the GP complex following cleavage by signal peptidase and plays crucial roles in the trafficking of GP through the secretory pathway (1, 50). Virus replication is confined to the cytoplasm of infected cells, and budding of progeny virus occurs at the plasma membrane (8, 13, 31, 33).

For most enveloped NS RNA viruses, the release of virus particles from host cells requires that assembled ribonucleoproteins (RNP) associate with cellular membranes that are enriched in viral glycoproteins. This association and subsequent virus release is most frequently mediated by a matrix (M) protein that acts as a bridge between the mature RNP and the GP. Recently, we (38) and others (44) showed that Z protein is the driving force for arenavirus budding. Consistent with its features as a bona fide budding protein, Z contains canonical late (L) domain motifs (38). L domains, originally identified in the Gag protein of retroviruses and since found in M proteins of a variety of viruses, play a critical role in the final steps of virus release, a process involving the interaction of viral budding proteins with host cell proteins (16, 49). LCMV Z contains the PPPY L domain motif, which is a recognition sequence for Nedd4-like ubiquitin ligases (43), whereas LFV Z contains, in addition to PPPY, a PTAP L domain motif that is known to interact with Tsg101, a member of the vacuolar protein-sorting pathway (16, 47). Consistent with these findings, the Z proteins from both LCMV and LFV have been documented to interact with Tsg101 (38, 46), suggesting that similarly to other viral budding proteins (32), Z-mediated budding requires the participation of components of the cell vacuolar protein-sorting pathway. In addition, Z-mediated budding requires its myristoyl modification (39), which likely facilitates Z association with membranes at budding sites.

Based on the evidence that Z is the arenavirus counterpart of the M protein found in many enveloped NS RNA viruses, we hypothesized that a Z-GPc interaction would be required for the generation of infectious viral particles. Here we provide the first experimental evidence of Z association with the GPc and begin to probe the requirements for this interaction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression constructs and cell transfection.

Plasmids expressing LCMV Z-HA, LCMV Z-AAPA, LFV Z-HA, LFV Z-LTAL-AAPA, LCMV Z-G2A, LCMV Z-A36, and LFV Z-G2A have been described previously (11, 38). The LCMV GP mutant LCMVGPD1 that abrogates processing of its GPC (23) contains a deletion of amino acids 462 to 498. Plasmid pC-LCMV-Z-HA F32G35 was made by patch-PCR using pC-Z-HA (38) as the template and primers designed to generate the desired mutations (OZHAPAT2, 5′-CGT CAT ATG GAT ATC CTC CCT CTT CGT AGG GAG GTG GAG AGC TTG GG-3′) and to allow cloning into the EcoRI and BglII sites (EcoRI and BamHI sites are underlined, with BamHI generating a BglII-compatible end) of pC (OZ1FEco, 5′-CCT GAA TTC ATG GGT CAA GGC AAG TCC-3′; and OHARBam2, 5′-CCG GGA TCC CTA AGC GTA ATC TGG AAC GTC ATA TGG ATA TCC TCC-3′). The backbone of the pC-based expression plasmids corresponds to pCAGGS (35). pC-LCMV-Z-Flag was also generated using a patch-PCR approach with the following primers: OZ1FEco (see above), OLCMVZFlagPATCH (5′-GTC TTT GTA GTC TCC TCC CTC TTC GTA GGG AGG TGG AGA GC-3′), and OFlagRBamHI (5′-TGC GGA TCC TCA TTT GTC GTC GTC GTC TTT GTA GTC TCC TCC-3′), which allowed for cloning of the final PCR product into the EcoRI and BglII sites of pC. pCMV-T7-SSP-HA was generated by ligating a DNA fragment containing the SSP of LCMV Armstrong strain (LCMV-ARM) into the pCMV-HA expression vector (Clontech). The SSP DNA fragment was generated by PCR amplification of the first 172 bp of the LCMV-ARM GPC open reading frame using proofStart (QIAGEN) high-fidelity DNA polymerase according to manufacturer's instructions. The primers used for amplification contained the appropriate restriction sites (5′ SfiI, 3′ BglII). The resulting PCR product was gel purified, digested with SfiI and BglII, and ligated to pCMV-HA digested with the same enzymes. Recovered plasmids were subsequently screened by restriction digest and confirmed by complete sequencing of the insert. The C-terminally Flag-tagged LCMV and LFV GP corresponded to full-length LCMV (ARM or its variant clone-13 [41]) GP and to LFV (Josiah strain) GP, in which the normal stop codon was replaced by a spacer sequence (GGGS), followed by the Flag tag (DYKDDDDK). For construction of C-terminally Flag-tagged LCMV and LFV GPs, a C-terminal fragment of LCMV GP and LFV GP was amplified by PCR using primer pairs LCMf/LCMVflag and LFVf/LFVflag, respectively. The resulting fragments were cut with KpnI and XhoI and used to replace the KpnI/XhoI fragments in pC-LCMVGP and pC-LFVGP that, respectively, encode the C termini of the GPs. The pC-LCMVGP contained full-length GPs derived from LCMV ARM or clone-13, whereas pC-LFVGP contained the full-length cDNA of LFV Josiah GP (23). The insert sequences were verified by double-strand DNA sequencing. A C-terminal Flag tag was added to the LCMV GP-D1 mutant in pC- LCMVGP-D1 using patch-PCR. Primers LCMf (5′-AAC CAC TGC ACA TAT GCA GGT-3′), LCMflag (5′-TAA CTC GAG TCA TTT ATC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC AGA TCC GCC ACC GCG TCT TTT CCA GAC GGT-3′), LFVf (5′-ACA TCA TGG GAA TTC CAT ACT-3′), LFVflag (5′-TAA CTC GAG TCA TTT ATC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC AGA TCC GCC ACC TCT CTT CCA TTT CAC AGG-3′), D1FlagPATCH (5′-GTC TTT GTA GTC TCC TCC GGA TCC TCC TCC GTG TGT TGG TAT TTT GAC-3′), and FlagRXho (5′-TGC CTC GAG TCA TTT GTC GTC GTC GTC TTT GTA GTC TCC TCC-3′) were used. All DNA samples were prepared for transfection using QIAGEN (Valencia, CA) reagents. HEK-293T (293T) cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged proteins.

To immunoprecipitate Flag-tagged proteins, cells were harvested on ice in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche, Indianapolis, IN], and 1% beta-octylglucopyranoside [βOG]) and incubated for an additional 30 min at 4°C with end-over-end rotation. Following incubation, the insoluble fraction was removed after centrifugation at 4°C, and the βOG-soluble fraction was incubated with anti-Flag (M2) affinity resin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) overnight at 4°C with end-over-end rotation. The bound anti-Flag resin was washed three times with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and boiled in 50 μl of 2× sample buffer containing 4% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 10% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol. The eluate was removed and used in Western blotting analysis. An aliquot of the βOG soluble fraction was boiled 1:1 (vol/vol) in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer and used for Western blotting analysis of total proteins.

Western blotting analysis.

Aliquots of cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were loaded on either 12% or 16% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) and then run under constant voltage in Tris-glycine buffer (42). Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or nitrocellulose at room temperature by electroelution and blocked overnight at 4°C in 1% blocking buffer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) or in 5% milk (for nitrocellulose membranes) in TBS. Membranes were then sequentially incubated in primary antibody (Ab) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) or overnight at 4°C in 0.5% blocking buffer or 5% milk, washed extensively in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T), then secondary Ab conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 40 min at RT or overnight at 4°C in 0.5% blocking buffer. Membranes were washed extensively in TBS-T and then treated for enhanced chemiluminescence and exposed to X-ray film. Anti-hemagglutinin (HA) polyclonal Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution, anti-Flag polyclonal Ab (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used at a 1:500 dilution, and 83.6 anti-GP2 monoclonal antibody was used at a 1:100 dilution. Anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG)-HRP-conjugated antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used at a 1:10,000 dilution. In Western blotting analysis of GP, using 83.6 antibody, mouse TrueBlot peroxidase conjugate antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution.

Indirect immunofluorescence analysis.

All incubations and washes were done in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Transiently transfected cells seeded on poly-lysine-coated coverslips were washed with cold PBS and fixed in 2% (vol/vol) formaldehyde/0.05% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde (electron microscopy grade) for 5 min at RT and then washed. Cells were then permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100 for 2 min at RT, washed, and blocked using 10% normal goat serum for 15 min at RT. Cells were incubated with primary Ab (1:500 dilution) for 1 h at RT in a moist chamber, washed extensively, incubated with secondary Ab (1:500) for 1 h at RT in a moist chamber, and washed extensively. Counterstaining for nuclei was done by treating cells with RNase A (27) for 30 min at RT and then incubating them with Toto-3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a dilution of 1:500 for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed extensively and then mounted on ca. 5 μl of Mowiol (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), and coverslips were sealed. Cells were analyzed using a Bio-Rad 1024 model confocal laser microscope. Images were analyzed using LSM Image Examiner (Zeiss) and Image J (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) software and then assembled using Adobe Photoshop. Anti-HA monoclonal Ab was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-Flag polyclonal Ab was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alex Fluor 488 or 584 were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

LCMV minigenome assay.

The LCMV minigenome (MG) rescue system has been described previously (38). Briefly, 293T cells (1.5 × 106) growing in 35-mm-diameter wells were transfected with the indicated plasmid combinations encoding NP (0.8 μg), L (1 μg), GP (0.4 μg), Z (0.1 μg), T7RP (1 μg), and MG 7Δ2G (0.5 μg). An empty pC plasmid was used to keep the total amount of DNA transfected constant in each well. At 72 h posttransfection, cell lysates were prepared for CAT assay as described previously (38). Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity levels were normalized by assigning 100% to the activity determined in lysates from cells transfected with L + NP + T7RP + MG. Background levels of CAT activity were detected in lysates of transfected cells that did not receive the plasmid encoding the L polymerase.

Generation of pseudotyped retroviral vectors.

The method used to pseudotype MLV virions with arenavirus GP has been described previously (23). Cells were cotransfected using either calcium phosphate or Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with plasmids containing the MLV gag and pol genes and a plasmid containing the firefly luciferase reporter gene within a packageable MLV genome. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cell supernatants were harvested, and titer over Vero cells was determined. Infectivity was scored as luciferase activity, using SteadyGlo or BrightGlo assay reagents (Promega, Madison, WI), in A549 cells.

Flow cytometry analysis.

Cells were transfected with plasmids containing untagged or Flag-tagged LCMV GP or LFV GP and analyzed by flow cytometry as described previously (23). Briefly, cells were detached using an enzyme-free cell dissociation solution (Sigma) and resuspended in PBS containing 1% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum and 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium azide (fluorescence-activated cell sorter [FACS] buffer). Cells were probed for extracellular GP by using the monoclonal Ab 83.6, followed by several washes in FACS buffer, incubation with phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, and three additional washes in FACS buffer. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (wt/vol in PBS), washed, and analyzed using a FACScalibur (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and either Cell Quest or FlowJo software.

RESULTS

Subcellular colocalization and biochemical interaction between Z and GP.

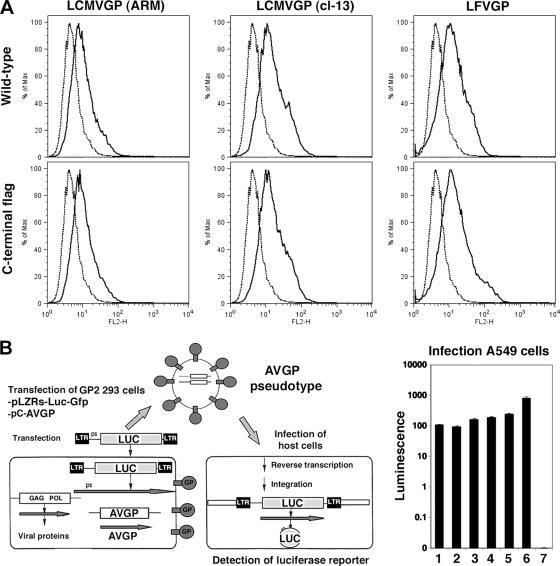

We examined the association of Z and GP by using 293T cells transfected with constructs expressing epitope-tagged versions of these proteins from either LCMV or LFV. We have previously shown that HA-tagged Z proteins are fully functional (38). To confirm that Flag-tagged versions of LCMV and LFV GPs were also functional, we examined their ability to traffic to the cell surface (Fig. 1A) and to mediate pseudotype infectivity (Fig. 1B). All GP-Flag versions were expressed on the surface of transfected cells at levels similar to that of untagged GP. Correspondingly, retrovirus pseudotypes containing untagged and Flag-tagged versions of GP from both LCMV and LFV showed comparable luciferase reporter activity upon infection of A549 cells. Since the Flag tag did not appear to affect GP function, we used Flag-tagged versions for LCMV (ARM) and LFV (Josiah) GPs in subsequent experiments.

FIG. 1.

Functional characterization of GP-Flag. (A) Surface localization of GP is unaltered by the presence of the C-terminal Flag tag in GP. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids containing LCMV (ARM) GP, LCMV (clone 13) GP, LFV (Josiah) GP, or their Flag-tagged counterparts, and surface GP was determined using FACS analysis. Fluorescence intensity is shown on the x axis, and relative cell counts on the y axis. (B) Murine leukemia virus (MLV) virions pseudotyped with arenavirus GP-Flag show infection efficiencies similar to those with untagged GP pseudotypes. The arenavirus GP constructs from panel A were used to prepare MLV pseudotypes (AVGP) and infect A549 cells following the schematic. Luciferase activity of the various pseudotypes is shown in the bar graph. Lanes: 1, LCMV ARM GP-Flag; 2, LCMV GP cl-13-Flag; 3, LFV GP-Flag; 4, LCMV ARM GP; 5, LFV GP; 6, VSV GP; 7, no GP.

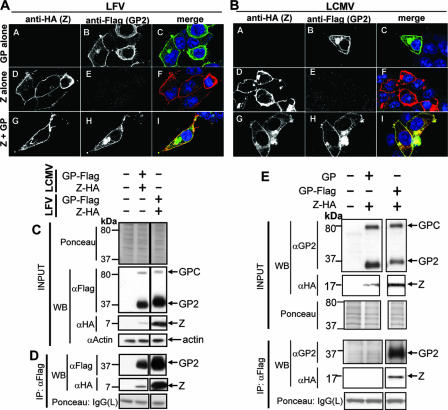

We then analyzed the subcellular distribution of Z and GP when they were expressed together. For this study, 293T cells were transfected with pC-GP-Flag or pC-Z-HA alone or together, and 36 h later, cells were processed for confocal microscopy. Cells transfected with either pC-GP-Flag or pC-Z-HA alone were incubated with anti-HA Ab and anti-Flag-Ab, respectively, to assess possible antibody cross-reactivity. We observed only negligible levels of cross-reactivity between the HA and Flag antibodies (Fig. 2A, panels C and D), indicating that the signal observed for cotransfected cells was specific. Both GP-Flag and Z-HA localized to the cell periphery when expressed independently (Fig. 2A, panels B and D, and Fig. 2B, panels B and D). We readily observed an overlap of the signals for GP-Flag and Z-HA in cells cotransfected with both GP-Flag and Z-HA from LCMV or LFV (Fig. 2A, panel I, Fig. 2B, panel I). Moreover, we observed that the patterns of GP and Z localization were not significantly different when expressed independently or together.

FIG. 2.

Subcellular localization and biochemical association of Z and GP. (A) LFV Z and GP colocalize in transfected cells. 293T cells were transiently transfected with LFV Z-HA, GP-Flag, or both and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence. Panels A A, A B, and A C correspond to cells transfected with LFV GP-Flag only; while panels D, E, and F correspond to cells transfected with LFV Z-HA only. Z-HA or GP-Flag was detected using anti-HA (mouse) and anti-Flag (rabbit) antibodies simultaneously to assess cross-reactivity and background. Panels A G to A I and B G to I correspond to cells expressing both Z-HA and GP-Flag, which show colocalization of both proteins. (B) LCMV Z and GP colocalize in transfected cells. Panel B is arranged as in panel A. Results are representative of several independent experiments. (C) Expression of GP and Z proteins. 293T cells were transiently transfected to express Z-HA and GP-Flag, as indicated above the lanes, and total cell lysates were subjected to Western analysis. As a negative control, cells were transfected with empty vector. A section of the membrane stained with Ponceau-S is shown to reflect equal loading. It was noted that expression of LCMV Z-HA was less than that of LFV Z-HA despite the use of the same plasmid to express these proteins. (D) Z and GP biochemically associate. Cell lysates shown in panel C were immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag antibody, and precipitated proteins were subjected to Western analysis. We could readily detect Z-HA from both LCMV and LFV in Flag immunoprecipitates containing the homologous GPs. (E) Z association with GP is specific. As a control to assess nonspecific interactions, cells were transfected with Z-HA and untagged GP and then subjected to anti-Flag immunoprecipitation. Lanes unrelated to this experiment were cropped. Z-HA was undetectable in immunoprecipitates from cells coexpressing untagged GP, while it was enriched in immunoprecipitates after coexpression with GP-Flag.

We sought to determine whether arenavirus Z and GP subcellular colocalization, as revealed by confocal microscopy, reflected a biochemical association. For this, we transfected 293T cells with pC-Z-HA and pC-GP-Flag, and 48 h later, cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using an anti-Flag Ab to pull down GP-Flag and associated proteins. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies to Flag and HA. GP and Z from both LCMV and LFV coimmunoprecipitated as determined by the Western blot detection of Z in protein complexes brought down by the anti-Flag Ab (Fig. 2D). It should be noted that expression levels of LCMV Z were consistently lower than that of LFV Z, despite the fact that both were expressed using the same expression plasmid (38). A control, where Flag immunoprecipitation was done with cells coexpressing Z and untagged GP, showed no Z in the immunoprecipitates, indicating that the coimmunoprecipitation of Z in the presence of GP-Flag was specific (Fig. 2E).

Genetic and biochemical interaction of Z and the GP cytoplasmic domain.

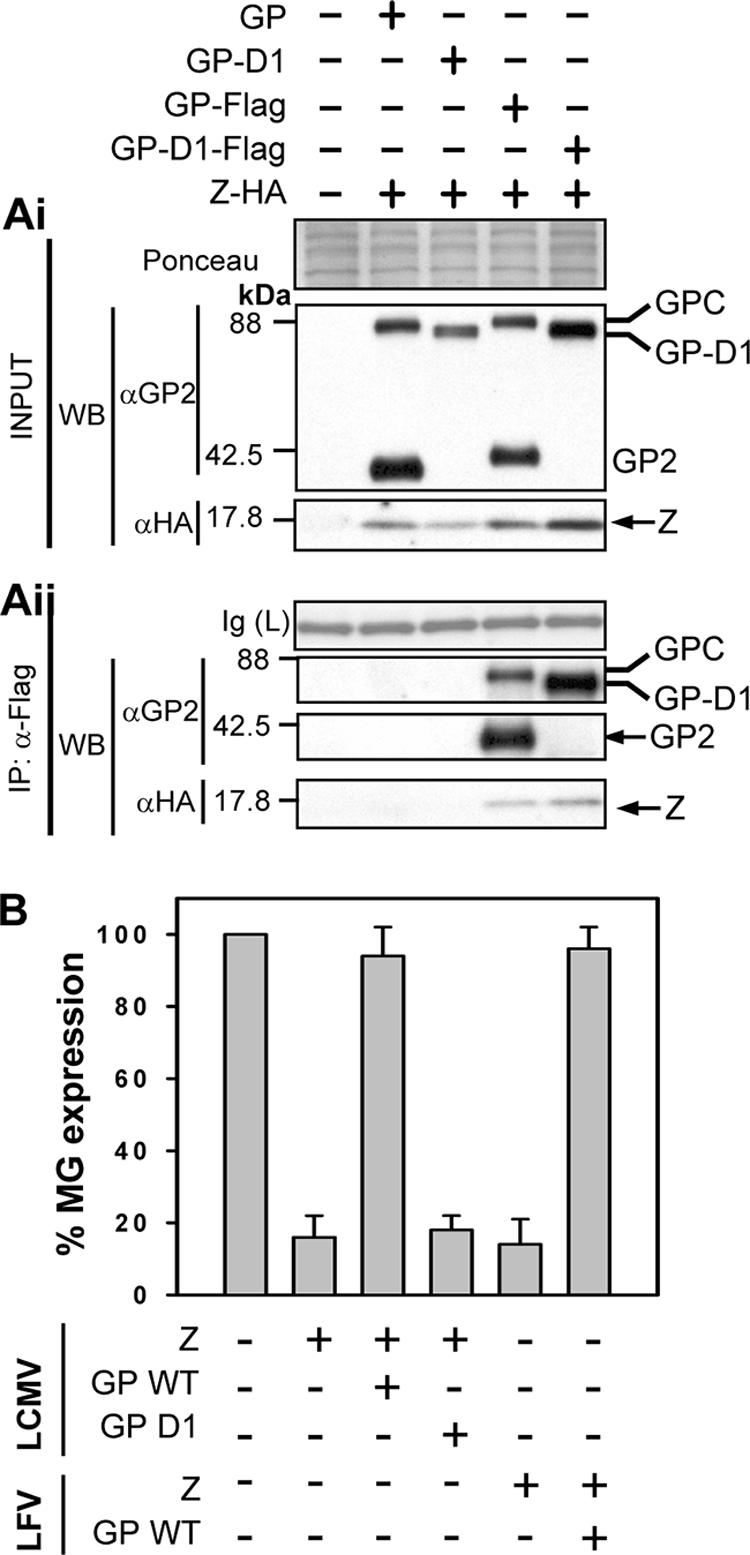

We have documented that Z exhibits a dose-dependent inhibitory activity on RNA synthesis by the LCMV polymerase (12). Notably, coexpression of GP significantly diminished Z-mediated inhibition of viral RNA synthesis as determined by levels of minigenome-directed CAT reporter gene expression (Fig. 3B). This effect appeared to be specific because the Z inhibitory effect was not alleviated by the GP of Borna disease virus (not shown). We obtained similar results with Z and GP from LCMV or LFV or with combinations of Z and GP from these two viruses (not shown), a finding consistent with our previous results showing that GP and Z gene products of LCMV and LFV can be exchanged with each other without affecting the efficiency of virus-like particles (VLP) formation (38). These findings provided genetic evidence of a Z-GP interaction that is consistent with the known requirement of both Z and GP for the generation of infectious arenavirus VLPs (24) and with our findings of subcellular colocalization and biochemical association of Z and GP (Fig. 2).

FIG. 3.

Biochemical and genetic interactions of Z and GP. (Ai) Expression of the LCMV Z-HA, the GP WT, the GP-D1 mutant, and Flag-tagged GPs in total cell lysates. The various GPs were detected using an anti-GP2 antibody, and Z was detected using an anti-HA antibody. A section of the membrane stained with Ponceau-S is shown to reflect equal loading. (Aii) The GP-D1 mutant associates biochemically with Z. Cell lysates shown in panel Ai were immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag antibody, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody to GP2. Z was visualized by Western blotting with anti-HA as shown in the panel, and bands of interest are indicated with arrows. As controls, cells were transfected with empty vector and with the WT GP or the GP-D1 mutant in the presence of Z-HA and then subjected to anti-Flag IP, which allows detection of nonspecific IP with the anti-Flag resin. To show equal loading, the IgG(L) fragment that stains clearly with Ponceau-S on the membrane is shown. (B) Z-mediated inhibition of the LCMV MG is prevented by the WT GP but not by the GP-D1 mutant. Cells (293T) were transfected with the indicated combination of plasmids, and 72-h cell lysates were prepared for CAT assays. CAT activities were normalized by assigning 100% to the activity determined in lysates from cells transfected with L + NP + T7RP + MG and after subtracting background levels of CAT activity detected in lysates of transfected cells that did not receive the plasmid encoding the L polymerase.

We reasoned that similar to the findings documented for M-GP interactions of many NS RNA viruses, the biochemical association of GP and Z would also require the cytoplasmic domain of LCMV GP2. To examine this, we coexpressed Z-HA with Flag-tagged versions of LCMV wild-type (WT) GP or a previously documented mutant GP (GP-D1) lacking the cytoplasmic domain (23). Z-HA coimmunoprecipitated with both the GP WT and the GP-D1 mutant (Fig. 3Aii). Nonspecific IP between the anti-Flag resin and untagged GP or Z-HA was not observed. Despite its ability to associate with Z, the GP-D1 mutant failed to alleviate the Z-mediated inhibitory effect on MG expression (Fig. 3B). In previous studies, GP-D1 exhibited WT levels of trafficking and cell surface expression but was impaired in its processing to GP1 and GP2 and in its ability to mediate pseudotype virion formation (23). These findings indicated that either the processing of GPC into GP1 and GP2 or the CTD directly is implicated in this process.

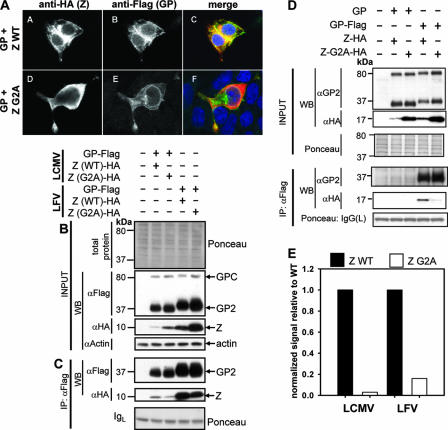

Role of myristoylation in the Z-GP association.

Myristoylation of Z is required for its budding activity (39, 45). We therefore asked whether myristoylation of Z was also required for its interaction with the GPc. For this we used LCMV and LFV Z mutants that contained a glycine→alanine substitution at position 2 (G2A), which receives the myristoyl group. This mutation is known to abolish Z myristoylation and Z-mediated budding (39). We transfected 293T cells with pC-Z-G2A-HA and pC-GP-Flag from the respective virus (LCMV or LFV) and either determined Z-G2A and GP2 localization by indirect immunofluorescence or immunoprecipitated GP-containing complexes in lysates of transfected cells. We observed a diffuse cytoplasmic expression pattern for the Z-G2A mutant, while GP showed localization to the plasma membrane and sometimes to a perinuclear location (Fig. 4A). In cells expressing both Z-G2A and GP, we detected colocalization only around the nucleus, as determined by an overlapping of the individual signals. Levels of Z-G2A from both LCMV and LFV in cells were higher than their WT counterparts in whole-cell lysates, as determined by Western analysis (Fig. 4B). However, GP immunoprecipitates contained significantly lower amounts of Z-G2A than the Z WT did (Fig. 4C). When we assayed cells expressing Z-G2A and untagged GP, we could not detect any Z-G2A in Flag-tagged immunoprecipitates, indicating that the low levels of Z-G2A expression we observed (Fig. 4C) resulted from the specific IP of Z-G2A with GP-Flag (Fig. 4D). To compare the amounts of Z-G2A and Z WT in immunoprecipitates with GP, we used densitometry analysis to normalize signals for Z-G2A in whole-cell lysates to those for Z WT and then compared the amounts of Z-G2A and Z-HA present in GP immunoprecipitates. This analysis revealed that the amounts of LFV Z-G2A and LCMV-G2A in immunoprecipitates with their respective GPs were decreased to 16% and 3%, respectively, of the corresponding Z WT proteins (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

Myristoylation greatly impacts the level of Z-GP association. (A) The Z-G2A mutant shows altered subcellular localization. LCMV Z-G2A HA and GP-Flag localization was assessed in transfected cells by using indirect immunofluorescence. As a positive control, indirect immunofluorescence of cells transfected with Z-HA WT and GP-Flag is shown. Panels A A and A D correspond to signals for Z only, panels A B and A E correspond to signals for GP only, while panels A C and A F show a merged image of the Z, GP, and nuclear signals. (B) Expression of GP-Flag and Z-G2A HA proteins. Cells were transfected with empty vector as a negative control and with GP-Flag and Z WT as a positive control, and total cell lysates were subjected to Western analysis. The lanes are labeled above panel B according to the Z-+-GP combination expressed in the transfectants. Staining of the membrane with Ponceau-S and probing for beta-actin were done to assess loading. It was noted that more Z-G2A was detectable than Z WT in cells. (C) The Z-G2A myristoylation mutant is decreased in biochemical association to GP. Cell lysates shown in panel B were subjected to anti-Flag immunoprecipitation. As controls to assess nonspecific associations, cells were cotransfected with the Z WT or Z-G2A and untagged GP. The amount of Z-G2A detectable in immunoprecipitates containing GP-Flag was similar to that which was detectable in the presence of untagged GP. (D) Densitometry analysis of the coimmunoprecipitated Z-G2A shown in panel B. The amount of Z-G2A was normalized to both the amount of the WT Z and the amount of actin in total cell protein. Results are representative of at least two independent experiments.

The roles of late and RING domains in Z-GP association.

To examine the contribution of the Z L domains to Z-GP association, we cotransfected 293T cells with pC-GP-Flag together with plasmids expressing L domain mutants of LCMV and LFV Z. We used indirect immunofluorescence and coimmunoprecipitation assays to determine the colocalization and association, respectively, of Z L domain mutants and GP and compared them with the corresponding findings obtained with cells cotransfected with pC-GP-Flag and pC-Z WT. For LCMV Z, we expressed a version with the mutation PPPY→AAPA, whereas for LFV Z we expressed a version with mutations in its two L domains (PTAP→LTAL and PPPY→AAPA).

Likewise, we used a mutated version of LCMV Z containing substitutions in the first two cysteine residues within the RING finger domain (referred to as F32G35), which are known to disrupt the folding and function of the RING finger motif (18, 19). We also incorporated into these studies a point mutation in LCMV Z at tryptophan 36 (W36A, referred to as A36 in reference 11), as this residue is conserved in RING finger cellular proteins with E3-type ubiquitin ligase activity (21) and in all known arenavirus Z proteins.

Both the LCMV Z-AAPA and the Z-W36A mutants showed expression levels at the plasma membrane similar to that of Z WT (Fig. 5A) and colocalized with GP. Interestingly, both mutants showed increased IP with GP compared to that of Z WT (Fig. 5C), which was quantified using densitometry analysis of the Western blots to normalize the expression of these mutants in whole-cell lysates and to compare the amounts of the Z mutants to that of Z WT in immunoprecipitates (Fig. 5D). We observed a similar increase in coimmunoprecipitated LFV Z-LTAL-AAPA with LFV GP compared to that of LFV Z WT (Fig. 5C and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Late and RING domains are not required for Z-GP association. (A) Subcellular localization of Z containing mutations in the late and RING domains. Cells were cotransfected with GP-Flag and various Z mutants, each containing a C-terminal HA tag, and subjected to indirect immunofluorescence of GP and Z. Images of a cell cotransfected to express Z WT and GP are shown as a control. We observed no change in the localization of the Z L domain mutant (Z-AAPA) or the Z-A36 mutant and their colocalization with GP; however, we observed a vesicular pattern in cells expressing the Z F32G35 mutant. (B) Expression of Z mutants in total cell protein. Transiently transfected 293T cells with the GP-Z combinations described in the legend to panel A were lysed, and proteins were detected by Western analysis using anti-Flag and anti-HA antibodies. To assess loading, the membrane was stained with Ponceau-S before probing for GP and Z and also probed for actin specifically. The amounts of GP expression appeared equal among the transfectants, while LCMV Z-AAPA and LCMV Z-A36 showed slightly more expression than LCMV Z WT. There were no differences in expression between LFV Z WT and LFV Z-AAPA-LTAL, but we consistently observed less Z-F32G35 in the βOG-soluble fraction of cells coexpressing GP. Densitometry analysis was used to normalize the expression of Z mutants to that of WT. (C) Late and RING domains are not required to mediate interaction of Z with GP. The cell lysates shown in panel B were subjected to Flag immunoprecipitation and Western blotting to detect Z WT strains and Z mutants. No differences were observed between LFV Z WT and LFV Z-AAPA-LTAL in Z-GP association, and the amounts of LCMV Z WT, LCMV Z-AAPA, and LCMV Z-A36 were consistent with levels in total cell protein. We observed more LCMV Z-F32G35 than LCMV Z WT in immunoprecipitates, however. (D) Densitometry analysis of Z L and RING domain mutants following Flag immunoprecipitation. A separate experiment containing duplicate transfections of the Z L and RING domain mutants was performed to assess the differences in association between the various Z mutants and GP shown in panel C. Following normalization of Z expression in whole-cell lysates, the amount of Z mutants present in Flag immunoprecipitates was compared to that of Z WT. This analysis revealed a modest increase in coimmunoprecipitation of Z-AAPA and Z-A36 with GP and a large increase in Z-F32G35 present in GP immunoprecipitates.

In contrast to the localization of the Z-AAPA and the Z-A36 mutants, the Z F32G35 RING domain mutant showed a distinct vesicular expression pattern that differed from that of Z WT (Fig. 5A). GP localization was not altered in most of the cells coexpressing the GP and Z F32G35 proteins. Interestingly, some cotransfected cells exhibited a GP signal in a pattern similar to that of the Z F32G35 mutant (Fig. 5A). In addition to its altered subcellular distribution, the Z F32G35 mutant was present at lower levels in beta-octylglucoside-soluble cell lysates (Fig. 5B). However, we clearly observed the coimmunoprecipitation of Z F32G35 with GP-Flag (Fig. 5B and C). Quantitation of the coimmunoprecipitation results by densitometry analysis indicated that the F32G35 RING mutant in LCMV Z exhibited a 40- to 70-fold increase in its GP association compared to that of Z WT (Fig. 5D).

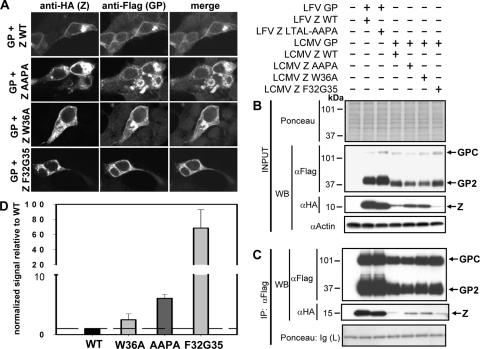

Association of Z with the stable signal peptide of GPC.

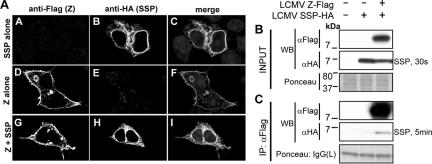

The SSP has recently been shown to be required for proper trafficking of Junin virus GPc through the secretory pathway, and the SSP remains stably associated with the GPc at the plasma membrane (1). This finding raised the possibility that SSP participates in Z-GPc interactions. We first examined whether Z and SSP exhibited any subcellular colocalization suggestive of association. For this, we transfected 293T cells with Z-Flag or SSP-HA alone or together and examined their subcellular distribution by using confocal microscopy. As predicted, Z-Flag localized mainly at the cell periphery, but it could also be found in vesicles within the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A, panels D and G). In contrast, SSP-HA localization appeared to be concentrated around the nucleus and in vesicles proximal to it (Fig. 6A, panels B and H). In cells cotransfected with Z-Flag and SSP-HA, the subcellular distributions of both Z and SSP were consistent with those observed for individual transfectants; however, we observed a modest but consistent overlap of Z-Flag and SSP-HA signals (Fig. 6A, panel I). When expression signals were calculated and weighted for signal intensity, we observed 25% of the signal from Z-Flag colocalized with SSP-HA and 23% for the converse.

FIG. 6.

Subcellular localization and biochemical association between LCMV Z and SSP. (A) LCMV Z and SSP minimally colocalize. 293T cells expressing LCMV Z-Flag and SSP-HA in the indicated combinations were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence and confocal laser scanning microscopy. As described in the legend to Fig. 2, cells expressing Z-Flag or SSP-HA alone were probed simultaneously with anti-Flag or anti-HA antibodies to assess cross-reactivity and background. We observed modest levels of colocalization of Z and SSP in cotransfected cells, which were 25% and 23% of Z with SSP and the reverse, respectively, as determined with the LSM Image Examiner program to calculate the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient for the respective signals of Z and SSP. (B) Expression of LCMV Z-Flag and SSP-HA in total cell protein. 293T cells were transiently transfected with LCMV Z-Flag and LCMV SSP-HA, and both proteins were detected in cells by Western analysis of whole-cell lysates. To observe loading, the membrane was stained with Ponceau-S before probing with antibodies, and the length of exposure time following enhanced chemiluminescence to detect SSP-HA is noted. (C) LCMV Z and SSP biochemically associate. Western analysis of anti-Flag immunoprecipitates was done for SSP-HA following coexpression with LCMV Z-Flag. As a control for specificity, anti-Flag immunoprecipitation was done following expression of SSP-HA alone in cells. Densitometry analysis of these exposures indicated that the specific co-IP signal from SSP-HA with LCMV Z-Flag was 9.7-fold higher than the condition where SSP-HA was expressed alone.

To determine whether the Z-SSP colocalization we observed by confocal microscopy correlated with a biochemical association, we cotransfected 293T cells with LCMV pC-Z-Flag and LCMV pCMV-SSP-HA and subjected cell lysates to Flag immunoprecipitation. As a control to address nonspecific binding of SSP-HA to the anti-Flag resin, SSP-HA was expressed alone. Both Z-Flag and SSP-HA were readily detected by Western blotting from whole-cell lysates (Fig. 6B). SSP-HA was readily detected in anti-Flag immunoprecipitates, but it required a longer exposure than in total cell lysates (Fig. 6C), suggesting that the coprecipitated SSP-HA corresponded to a minor fraction of the total SSP-HA. However, Flag immunoprecipitates from cells expressing only SSP-HA showed 9.7-fold lower levels of SSP-HA (Fig. 6C), indicating that the low levels of Z-SSP coimmunoprecipitation observed with lysates of cells transfected with Z-Flag and SSP-HA were specific.

DISCUSSION

The known roles played by Z and GP during the arenavirus life cycle would predict the requirement of Z-GP association for formation of virus progeny. In this work, we have provided for the first time experimental evidence that arenavirus Z and GP associate as determined by their subcellular colocalization and specific co-IP. We obtained similar results using Z and GP from either LCMV or LFV.

The presence or absence of colocalization among various mutants in Z and the GPc was consistent with the level of biochemical association between these proteins. Mutations in the L domains or the conserved W residue at position 36 did not affect the subcellular distribution of Z (Fig. 5) or the ability of Z to colocalize or co-IP with the GPc. The level of Z-GP association, however, was greatly reduced in the absence of Z myristoylation, both at the level of intracellular localization and the level of co-IP (Fig. 4). One could envisage that the Z-GP interaction might be facilitated by association at the inner leaflet of membranes, where Z would localize due to its myristoyl modification and have access to the CTD of GP2 (34). Consistent with this notion, alleviation of the Z-mediated inhibition of RNA synthesis was not observed with the GP-D1 mutant lacking the CTD within GP2 (Fig. 3B). Since GP-D1 showed efficient biochemical association with Z, it is plausible that GPC alleviation of the Z-mediated inhibitory effect on RNA synthesis involves a host factor that facilitates Z-GPC interaction via the CTD of GP2. The GP-D1 mutant is also defective for GP processing, and thereby we cannot distinguish between the requirement for the CTD or GP processing or both in alleviating the inhibitory effect of Z on RNA synthesis. By contrast, biochemical association was still observed between the GP-D1 mutant and Z. This result suggests that neither the CTD nor GP processing is required for biochemical association of Z and GP. Interestingly, the predicted transmembrane domain for GP encompasses amino acids 434 to 456, while the GP-D1 mutant lacks amino acids 462 to 498, raising the possibility that the remaining six amino acids of the CTD might be involved in GP biochemical association with Z.

We also observed a low but significant degree of subcellular colocalization between LCMV SSP and Z (Fig. 6A) that correlated with a low but specific biochemical association (Fig. 6C). The presence of SSP at a perinuclear location (Fig. 6A) is consistent with endoplasmic reticular localization, and it was recently reported that a weak endoplasmic reticular retention signal may exist in Junin virus SSP (1).

For a number of viruses including measles and Ebola viruses (4, 26, 37), their release from infected cells has been shown to depend on interactions with lipid rafts, also referred to as detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs). However, our results argue that it is unlikely that DRMs are required to maintain the Z-GPc association because cell lysates used to co-IP Z with GPc were prepared in the presence of βOG, which disrupts lipid rafts (2). However, we cannot rule out that DRMs might be involved in the proper assembly of the complex or in other processes necessary for the virus life cycle. Future studies will take advantage of the LCMV reverse genetics system to determine the full array of implications of Z-GP association in the virus life cycle.

Loss of myristoylation in Z showed a strong phenotype with regard to Z-GP subcellular colocalization and biochemical association. The localization of myristoylation-defective LCMV Z G2A was similar to that observed for a G2A mutant in the spleen necrosis virus matrix protein (48) but was inconsistent with recently published work with the LFV Z G2A mutant (45), which showed a punctate appearance and accumulation in an intracellular compartment. Despite this difference in phenotype, the downstream effects of the G2A mutation on LFV Z correlated well with our previous work with the LFV Z G2A mutant (39). As Z myristoylation is required for membrane association (39, 44, 45), this raises the possibility that the accumulation of Z at certain membranes within the cell is the limiting factor for its association with GP. Whether Z localization is really the limiting factor for interaction with GP and what the nature of myristoylation-independent Z-GP association is (Fig. 4D) will require further studies.

In addition to myristoyl modification, the Z protein contains the RING domain, thought to be a scaffolding domain that mediates a number of protein-protein interactions (6). Z also contains one or more late domains, which have been coopted by many enveloped RNA viruses to access the multivesicular body pathway during budding of progeny virus (32), which has also been implicated in the life cycle of arenaviruses (38, 46). We therefore reasoned that the Z RING domain, and possibly the late domain, could contribute to Z-GP association. However, mutations within the Z RING and late domains did not diminish the levels of Z and GP association (Fig. 5C). Additionally, we observed a modest increase in the biochemical association between Z late domain mutants and GP (Fig. 5D). It was intriguing that not only did the Z-GPc association tolerate the altered localization of Z F32G35 (Fig. 5A), but the amount of Z that coimmunoprecipitated with GP was markedly increased for the Z F32G35 mutant compared to those of either the late domain mutants or another strain carrying a point mutation (W36A) within the RING domain (Fig. 5D). The altered localization may be involved in the increase in co-IP between the Z F32G35 mutant and GP, and further experiments will be needed to dissect the exact relationship between the two phenotypes of this mutant.

One attractive model based on these findings would posit that regions in Z, other than L and RING finger domains, are engaged in contacts with GP with Z remaining available for interaction with host cell factors via the late and RING domains. Notably, perturbing the L and RING domains actually increased the biochemical association between Z and GP, suggesting that Z-GP association is enhanced when the L and RING domains cannot engage host cell factors. We are currently testing whether a specific GP-binding domain exists in Z, but it is equally possible that a host cell protein mediates Z-GP association, a situation that has been documented with the human immunodeficiency virus matrix protein (25).

Our results expand on the model in which Z is the matrix counterpart for arenaviruses and accomplishes this in part through its interaction with GP. This fits well with recent data regarding the ultrastructure of arenavirus virions as determined by cryoelectron microscopy (34), where Z protein was assigned to a region of electron density just below that of the lipid envelope of the virus particle, an arrangement consistent with the location of other RNA virus matrix proteins within the virion (7, 22).

Elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the Z-GP complex association and its consequences will contribute to further describing the complete array of roles played by Z in the arenavirus life cycle. Likewise, dissecting the chronology and subcellular locations of the different steps of Z-GP association in infected cells will increase our knowledge of arenavirus biology. This knowledge could then fuel the design of anti-arenavirus compounds that target Z-GP interactions, which would be predicted to interfere with arenavirus assembly or budding. Moreover, determining the requirements for Z-GP association in virion formation could improve the design of recombinant viruses that express foreign GPs, which have recently shown promise as live attenuated vaccines (5).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants AI47140 (to J.C.T.), AI-065359 Pacific Southwest Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases (to J.C.T. and M.J.B.), and AI-050840 Vaccination for Lassa Fever (to M.J.B.). E.B. was supported by grant T32 AI-07354. A.A.C. was supported by grant T32 NS041219-06.

This is publication 18553-MIND of the Molecular Integrative Neuroscience Department.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agnihothram, S. S., J. York, and J. H. Nunberg. 2006. Role of the stable signal peptide and cytoplasmic domain of G2 in regulating intracellular transport of the Junin virus envelope glycoprotein complex. J. Virol. 80:5189-5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aizaki, H., K. J. Lee, V. M. Sung, H. Ishiko, and M. M. Lai. 2004. Characterization of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex associated with lipid rafts. Virology 324:450-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton, L. L., M. B. Mets, and C. L. Beauchamp. 2002. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: emerging fetal teratogen. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 187:1715-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bavari, S., C. M. Bosio, E. Wiegand, G. Ruthel, A. B. Will, T. W. Geisbert, M. Hevey, C. Schmaljohn, A. Schmaljohn, and M. J. Aman. 2002. Lipid raft microdomains: a gateway for compartmentalized trafficking of Ebola and Marburg viruses. J. Exp. Med. 195:593-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergthaler, A., N. U. Gerber, D. Merkler, E. Horvath, J. C. de la Torre, and D. D. Pinschewer. 2006. Envelope exchange for the generation of live-attenuated arenavirus vaccines. PLoS Pathog. 2:e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borden, K. L. 2000. RING domains: master builders of molecular scaffolds? J. Mol. Biol. 295:1103-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs, J. A., M. C. Johnson, M. N. Simon, S. D. Fuller, and V. M. Vogt. 2006. Cryo-electron microscopy reveals conserved and divergent features of gag packing in immature particles of Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus. J. Mol. Biol. 355:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchmeier, M. J., J.-C. de la Torre, and C. Peters. 2007. Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 1792-1827. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 5th ed., vol. 2. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchmeier, M. J., and M. B. Oldstone. 1979. Protein structure of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: evidence for a cell-associated precursor of the virion glycopeptides. Virology 99:111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns, J. W., and M. J. Buchmeier. 1991. Protein-protein interactions in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology 183:620-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornu, T. I., and J. C. de la Torre. 2002. Characterization of the arenavirus RING finger Z protein regions required for Z-mediated inhibition of viral RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 76:6678-6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornu, T. I., and J. C. de la Torre. 2001. RING finger Z protein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) inhibits transcription and RNA replication of an LCMV S-segment minigenome. J. Virol. 75:9415-9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalton, A. J., W. P. Rowe, G. H. Smith, R. E. Wilsnack, and W. E. Pugh. 1968. Morphological and cytochemical studies on lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. J. Virol. 2:1465-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Torre, J. C., and M. B. A. Oldstone. 1996. The anatomy of viral persistence: mechanisms of persistence and associated disease. Adv. Virus Res. 46:311-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichler, R., T. Strecker, L. Kolesnikova, J. ter Meulen, W. Weissenhorn, S. Becker, H. D. Klenk, W. Garten, and O. Lenz. 2004. Characterization of the Lassa virus matrix protein Z: electron microscopic study of virus-like particles and interaction with the nucleoprotein (NP). Virus Res. 100:249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrus, J. E., U. K. von Schwedler, O. W. Pornillos, S. G. Morham, K. H. Zavitz, H. E. Wang, D. A. Wettstein, K. M. Stray, M. Cote, R. L. Rich, D. G. Myszka, and W. I. Sundquist. 2001. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107:55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geisbert, T. W., and P. B. Jahrling. 2004. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nat Med. 10:S110-S121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda, R., and H. Yasuda. 2000. Activity of MDM2, a ubiquitin ligase, toward p53 or itself is dependent on the RING finger domain of the ligase. Oncogene 19:1473-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu, G., and E. R. Fearon. 1999. Siah-1 N-terminal RING domain is required for proteolysis function, and C-terminal sequences regulate oligomerization and binding to target proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:724-732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahrling, P. B., and C. J. Peters. 1992. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. A neglected pathogen of man. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 116:486-488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joazeiro, C. A., S. S. Wing, H. Huang, J. D. Leverson, T. Hunter, and Y. C. Liu. 1999. The tyrosine kinase negative regulator c-Cbl as a RING-type, E2-dependent ubiquitin-protein ligase. Science 286:309-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingston, R. L., N. H. Olson, and V. M. Vogt. 2001. The organization of mature Rous sarcoma virus as studied by cryoelectron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 136:67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunz, S., K. H. Edelmann, J.-C. de la Torre, R. Gorney, and M. B. A. Oldstone. 2003. Mechanisms for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein cleavage, transport, and incorporation into virions. Virology 314:168-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, K. J., I. S. Novella, M. N. Teng, M. B. Oldstone, and J. C. de La Torre. 2000. NP and L proteins of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) are sufficient for efficient transcription and replication of LCMV genomic RNA analogs. J. Virol. 74:3470-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Verges, S., G. Camus, G. Blot, R. Beauvoir, R. Benarous, and C. Berlioz-Torrent. 2006. Tail-interacting protein TIP47 is a connector between Gag and Env and is required for Env incorporation into HIV-1 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:14947-14952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manié, S. N., S. Debreyne, S. Vincent, and D. Gerlier. 2000. Measles virus structural components are enriched into lipid raft microdomains: a potential cellular location for virus assembly. J. Virol. 74:305-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin, R. M., H. Leonhardt, and M. C. Cardoso. 2005. DNA labeling in living cells. Cytometry A 67:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormick, J. B., and S. P. Fisher-Hoch. 2002. Lassa fever, p. 75-110. In M. B. Oldstone (ed.), Arenaviruses I, vol. 262. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKee, K. T., Jr., J. W. Huggins, C. J. Trahan, and B. G. Mahlandt. 1988. Ribavirin prophylaxis and therapy for experimental Argentine hemorrhagic fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 32:1304-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mets, M. B., L. L. Barton, A. S. Khan, and T. G. Ksiazek. 2000. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: an underdiagnosed cause of congenital chorioretinitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 130:209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer, B. J., J. C. de La Torre, and P. J. Southern. 2002. Arenaviruses: genomic RNAs, transcription, and replication, p. 139-149. In M. B. Oldstone (ed.), Arenaviruses I, vol. 262. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morita, E., and W. I. Sundquist. 2004. Retrovirus budding. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20:395-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy, F. A., P. A. Webb, K. M. Johnson, S. G. Whitfield, and W. A. Chappell. 1970. Arenaviruses in Vero cells: ultrastructural studies. J. Virol. 6:507-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuman, B. W., B. D. Adair, J. W. Burns, R. A. Milligan, M. J. Buchmeier, and M. Yeager. 2005. Complementarity in the supramolecular design of arenaviruses and retroviruses revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image analysis. J. Virol. 79:3822-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niwa, H., K. Yamamura, and J. Miyazaki. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oldstone, M. B. 2002. Biology and pathogenesis of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection, p. 83-118. In M. B. Oldstone (ed.), Arenaviruses I, vol. 263. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panchal, R. G., G. Ruthel, T. A. Kenny, G. H. Kallstrom, D. Lane, S. S. Badie, L. Li, S. Bavari, and M. J. Aman. 2003. In vivo oligomerization and raft localization of Ebola virus protein VP40 during vesicular budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:15936-15941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez, M., R. C. Craven, and J. C. de la Torre. 2003. The small RING finger protein Z drives arenavirus budding: implications for antiviral strategies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12978-12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez, M., D. L. Greenwald, and J. C. de la Torre. 2004. Myristoylation of the RING finger Z protein is essential for arenavirus budding. J. Virol. 78:11443-11448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters, C. J. 2002. Human infection with arenaviruses in the Americas, p. 65-74. In M. B. Oldstone (ed.), Arenaviruses I, vol. 262. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salvato, M., P. Borrow, E. Shimomaye, and M. B. Oldstone. 1991. Molecular basis of viral persistence: a single amino acid change in the glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is associated with suppression of the antiviral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response and establishment of persistence. J. Virol. 65:1863-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 43.Staub, O., S. Dho, P. Henry, J. Correa, T. Ishikawa, J. McGlade, and D. Rotin. 1996. WW domains of Nedd4 bind to the proline-rich PY motifs in the epithelial Na+ channel deleted in Liddle's syndrome. EMBO J. 15:2371-2380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strecker, T., R. Eichler, J. Meulen, W. Weissenhorn, H. Dieter Klenk, W. Garten, and O. Lenz. 2003. Lassa virus Z protein is a matrix protein sufficient for the release of virus-like particles. J. Virol. 77:10700-10705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strecker, T., A. Maisa, S. Daffis, R. Eichler, O. Lenz, and W. Garten. 2006. The role of myristoylation in the membrane association of the Lassa virus matrix protein Z. Virol. J. 3:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urata, S., T. Noda, Y. Kawaoka, H. Yokosawa, and J. Yasuda. 2006. Cellular factors required for Lassa virus budding. J. Virol. 80:4191-4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.VerPlank, L., F. Bouamr, T. J. LaGrassa, B. Agresta, A. Kikonyogo, J. Leis, and C. A. Carter. 2001. Tsg101, a homologue of ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes, binds the L domain in HIV type 1 Pr55(Gag). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7724-7729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weaver, T. A., and A. T. Panganiban. 1990. N myristoylation of the spleen necrosis virus matrix protein is required for correct association of the Gag polyprotein with intracellular membranes and for particle formation. J. Virol. 64:3995-4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wills, J. W., and R. C. Craven. 1991. Form, function, and use of retroviral gag proteins. AIDS 5:639-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.York, J., V. Romanowski, M. Lu, and J. H. Nunberg. 2004. The signal peptide of the Junin arenavirus envelope glycoprotein is myristoylated and forms an essential subunit of the mature G1-G2 complex. J. Virol. 78:10783-10792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zinkernagel, R. M. 2002. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and immunology. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 263:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]