Abstract

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry were used to analyze the structural proteins of the occlusion-derived virus (ODV) of Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (HearNPV), a group II NPV. Twenty-three structural proteins of HearNPV ODV were identified, 21 of which have been reported previously as structural proteins or ODV-associated proteins in other baculoviruses. These include polyhedrin, P78/83, P49, ODV-E18, ODV-EC27, ODV-E56, P74, LEF-3, HA66 (AC66), DNA polymerase, GP41, VP39, P33, ODV-E25, helicase, P6.9, ODV/BV-C42, VP80, ODV-EC43, ODV-E66, and PIF-1. Two proteins encoded by HearNPV ORF44 (ha44) and ORF100 (ha100) were discovered as ODV-associated proteins for the first time. ha44 encodes a protein of 378 aa with a predicted mass of 42.8 kDa. ha100 encodes a protein of 510 aa with a predicted mass of 58.1 kDa and is a homologue of the gene for poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (parg). Western blot analysis and immunoelectron microscopy confirmed that HA44 is associated with the nucleocapsid and HA100 is associated with both the nucleocapsid and the envelope of HearNPV ODV. HA44 is conserved in group II NPVs and granuloviruses but does not exist in group I NPVs, while HA100 is conserved only in group II NPVs.

The Baculoviridae, a diverse family of more than 600 viruses, encompasses two genera, the nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs) and the granuloviruses (GVs) (5). Baculoviruses are generally host specific, infecting mainly insects of the orders Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera, and Diptera. Two progeny phenotypes are produced in the replication cycle, the budded virus (BV) and the occlusion-derived virus (ODV). In larvae, ODVs initiate primary infections in midgut epithelial cells of susceptible hosts and BVs spread the virus from cell to cell in the larvae (5, 30, 62). The two phenotypes are genotypically identical, but each has characteristic structural components to accommodate their respective functions (7, 50). Based on phylogeny, lepidopteran NPVs are divided into group I and group II (23, 24, 70). It is known now that the BVs of group I and group II NPVs use different fusion proteins to enter host cells. GP64 is the membrane fusion protein of group I NPVs (4, 40), while the F protein is that of group II NPVs (27, 36, 44).

Identification of ODV structural proteins and comparisons in different NPVs are fundamental to the functional investigation of virulence and host specificity. So far, 30 genome sequences of baculoviruses have been reported, including 8 group I NPVs, 12 group II NPVs, 7 GVs, 1 dipteran NPV, and 2 hymenopteran NPVs. The availability of the genome sequences has facilitated proteomic analysis of baculoviruses. In 2003, proteomic investigations revealed 44 proteins to be ODV components of Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV), a group I NPV (11). Recent investigations of a dipteran NPV, Culex nigripalpus NPV (CuniNPV), identified 44 ODV-associated proteins (46). By comparison, little is known about the structural proteins of ODVs from group II NPVs.

The Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid NPV (HearNPV, also called HaSNPV) was first isolated in 1975 in the Hubei Province of the People's Republic of China and has been used extensively over 25 years in China to control H. armigera in cotton (71). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that HearNPV belongs to the group II NPVs (12, 29). Its DNA genome is 131 kb and contains 135 open reading frames (ORFs) that potentially encode proteins of 50 amino acids (aa) or larger (13). Several HearNPV genes, such as the polyhedrin gene (polh) (14), the ecdysteroid UDP-glucosyltransferase gene (egt) (15), the late expression factor 2 gene (lef-2) (12), the basic DNA-binding protein gene (p6.9) (61), ha122 (37), Ha94 (19), chitinase (60), fp25K (67), p10 (18), and the F-protein gene (ha133) (36), have been characterized.

In this report, we describe using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and mass spectrometry-based protein analysis techniques to study structural proteins of the ODV of HearNPV. HearNPV was chosen to serve as a representative of the group II NPVs. ODV proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by peptide mass fingerprinting techniques by using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The resulting mass spectra were searched against the NCBI database and the theoretical ORF database of HearNPV. A total of 23 proteins were identified as ODV-associated proteins. Of these 23 proteins, 21 were previously reported as ODV-associated proteins in other baculoviruses but 2 were hitherto unknown as ODV-associated proteins. These two newly identified proteins, encoded by ha44 and ha100, respectively, were further shown to be structural components of the ODV by Western blot analysis and immunoelectron microscopy (IEM).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insects, cells, and virus.

A culture of H. armigera insects was maintained as described by Sun et al. (55). An in vivo-cloned strain of HearNPV (HearNPV-G4) (13, 55) was used as the wild-type virus and propagated in H. armigera. Cells of the Heliothis zea HzAM1 line (39) were used for producing BV of HearNPV.

Purification of HearNPV BV and ODV.

BV was purified from the cell culture supernatant of infected HzAM1 cells (72 h postinfection) as described by Braunagel and Summers (7). Larvae were homogenized in 0.1% SDS, followed by a few rounds of differential and rate zonal centrifugation in sucrose gradients. All solutions were supplemented with 0.1% SDS (56). Protease inactivation of the purified occlusion bodies was performed by HgCl2 and hot water treatment (54). ODVs were released by alkaline treatment (pH 10.9) (7) and purified on continuous sucrose gradients. Purified BV and ODV were further fractionated into envelope and nucleocapsid components (28).

Protein separation, reduction, alkylation, and digestion.

Proteins from purified HearNPV ODV were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with a colloidal blue staining kit (Invitrogen). Protein bands were excised from the one-dimensional polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel and destained by washing with a mixture of 200 mM NH4HCO3-acetonitrile (1:1). Proteins were reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested in gel with trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI) as previously described (53). The peptide mixtures obtained were further desalted by ZipTipC18 (Millipore) and eluted in 50% acetonitrile-0.1% trifluoroacetic acid buffer before MS analysis.

MALDI-TOF MS.

A saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and 50% acetonitrile was used as the matrix. The sample and the matrix (1:1, vol/vol) were spotted onto a target plate. MALDI-TOF spectra of the peptides were obtained with a Voyager DE STR MALDI-TOF work station mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems Inc.). The analysis was performed in positive-ion reflector mode with an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a delayed extraction of 150 ns. Typically, 200 scans were averaged. Data mining was performed with MS-Fit software (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/ucsfhtml4.0/msfit.htm) and Mascot software (http://www.matrixscience.com/search_form_select.html) against the NCBI database and the theoretical ORF database of HearNPV.

Sequence analysis of ha44 and ha100.

The sequence data were compiled and analyzed with DNASTAR software. Homologues in the GenBank and EMBL databanks were explored with the PSI-BLAST search tool (1). Amino acid sequence alignment was performed with Clustal X and T coffee software (42, 58). GeneDoc software (version 1.1.1004) was used for similarity shading and scoring of alignment. MEGA3.1 (33) was used for generating the phylogenetic trees by the neighbor-joining method, with bootstrap replications. A phylogenetic tree was visualized with the Treeview program.

Preparation of antibodies against HA44 and HA100.

The entire ha44 coding region and a truncated fragment of the ha100 gene were amplified with synthesized primers Ha44a/Ha44b (Ha44a, 5′-GAATTCATGAGCAATCCCAGCAAACAATC-3′; Ha44b, 5′-GAATTCTCAATAGCGCAAACGAGTTTCG-3′) and Ha100f/Ha100r (Ha100f, 5′ GCCGGATCCATGACTTTGTCGCGTTTAGATTGCG-3′; Ha100r, 5′-GGCTCTAGATTAATAAACCATATTGTAATCGGCAAC-3′), respectively (the sequences in italics are restriction enzyme digestion sites. The PCR product of ha44 was first cloned into pGEM-T-Easy (Promega) and then into the expression vector pET28a (Novagen) in which ha44 was fused in frame with a six-His tag at the C terminus. The PCR product of ha100 was first cloned into pGEM-T-Easy (Promega) and then into the expression vector pGEX-KG (22) in which ha100 was fused in frame with the gene for glutathione S-transferase at the C terminus. HA44 expressed in Escherichia coli was purified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (QIAGEN), and HA100 was purified by glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma). The purified proteins were used to generate specific antibodies against HA44 and HA100.

Purified HA44 and HA100 (200 μg) were used to immunize rabbits. Preimmune sera were withdrawn prior to inoculation. After 3 weeks, the rabbits received a booster with the same amount of the antigens. Two weeks later, the antisera were collected and stored at −80°C until use. The specificities of the antisera were tested by Western blot analysis.

Western blot analysis.

Purified BVs and ODVs, as well as their nucleocapsid and envelope fractions, were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Hybond-N membranes (Amersham) by semidry electrophoresis transfer (2). HA44- and HA100-specific antisera and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated immunoglobulin G (SABC, China) were used as the primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. The signal was detected with a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (BCIP)-nitroblue tetrazolium kit (SABC, China). Polyclonal anti-VP80, anti-ODV-E56, and anti-HaF1 antibodies were used as controls for nucleocapsid-, ODV envelope-, and BV envelope-specific proteins, respectively.

IEM.

Purified ODVs were added to carbon-coated nickel grids (150 mesh) and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin. The primary antibodies were 1:100 dilutions of anti-HA44 and anti-HA100 antisera. Preimmune sera were used as the negative controls. Twelve-nanometer Colloidal Gold-AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used as the secondary antibody for hybridization. The grids were then negatively stained with 2% sodium phosphotungstate and examined with a transmission electron microscope (H-7000 FA; Hitachi).

RESULTS

MS identification of HearNPV ODV proteins.

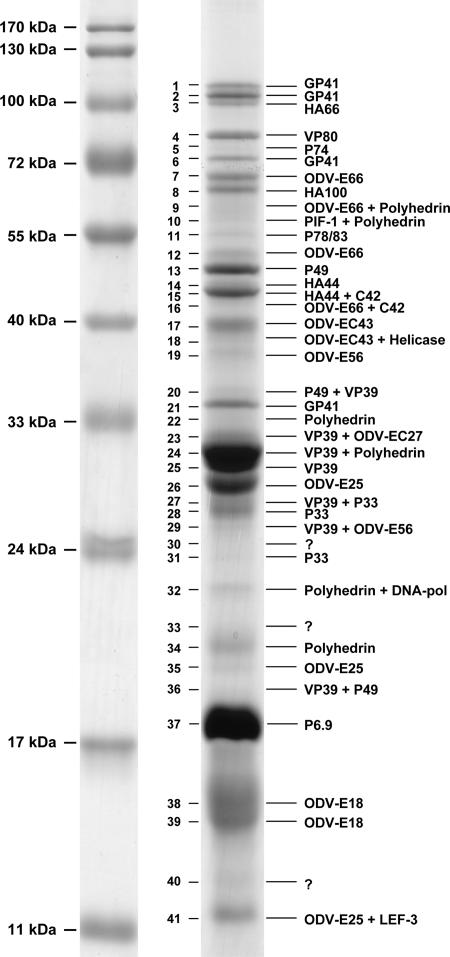

HearNPV ODVs were purified, and the proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. More than 40 bands ranging from 11 to 110 kDa were made visible by colloidal blue staining (Fig. 1). Forty-one bands were excised from the gel, reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin, and the peptides were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS. Peak lists of tryptic peptide masses were generated and subjected to an NCBI database and HearNPV ORF database search with MS-Fit and the Mascot search engine. The SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF MS analyses were performed twice. Reliable gene DNA matches from the theoretical HearNPV ORFs were obtained and are summarized in Table 1. Twenty-three ORFs were identified, including ha1 (polh), ha2 (p78/83), ha9 (p49), ha10 (odv-e18), ha11 (odv-ec27), ha15 (odv-e56), ha20 (p74), ha44, ha65 (lef-3), ha66 (Ac66), ha67 (dna-pol), ha73 (gp41), ha78 (vp39), ha80 (p33), ha82 (odv-e25), ha84 (helicase), ha88 (p6.9), ha89 (odv/bv-C42), ha92 (vp80), ha94 (odv-EC43), ha96 (odv-e66), ha100, and ha111 (pif-1).

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE profile and MS results of purified HearNPV ODV. ODV proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with colloidal blue. The ODV bands (numbered in the middle) were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS, and their identities are listed on the right.

TABLE 1.

HearNPV ODV proteins identified by MALDI-TOF MSa

| Band | Size (kDa) from SDS-PAGE | HearNPV ORF | AcMNPV ORF | Protein | Predicted size (kDa) | Sequence coverage (%) | Function | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110 | ha73 | ac80 | GP41 | 36.6 | 43 | Tegument main protein | 63, 64 |

| 2 | 103 | ha73 | ac80 | GP41 | 36.6 | 28 | Tegument main protein | 63, 64 |

| 3 | 100 | ha66 | ac66 | HA66 | 88.9 | 37 | ODV-associated protein | 11 |

| 4 | 83 | ha92 | ac104 | VP80 | 69.7 | 37 | Nucleocapsid | 38, 41 |

| 5 | 78 | ha20 | ac138 | P74 | 78.4 | 25 | Oral infectivity | 21, 34, 68 |

| 6 | 73 | ha73 | ac80 | GP41 | 36.6 | 58 | Tegument main protein | 63, 64 |

| 7 | 65 | ha96 | ac46 | ODV-E66 | 76.1 | 35 | ODV envelope | 26 |

| 8 | 60 | ha100 | HA100 | 58.1 | 26 | Nucleocapsid- and ODV envelope-associated protein | This study | |

| 9 | 58 | ha1 | ac8 | Polyhedrin | 28.8 | 40 | Polyhedron main protein | 49 |

| ha96 | ac46 | ODV-E66 | 76.1 | 12 | ODV envelope | 26 | ||

| 10 | 56 | ha111 | ac119 | PIF-1 | 60.3 | 19 | Oral infectivity | 31 |

| ha1 | ac8 | Polyhedrin | 28.8 | 40 | Polyhedron main protein | 49 | ||

| 11 | 54 | ha2 | ac9 | P78/83 | 45.9 | 49 | Nucleocapsid | 47, 52 |

| 12 | 50 | ha96 | ac46 | ODV-E66 | 76.1 | 25 | ODV envelope | 26 |

| 13 | 48 | ha9 | ac142 | P49 | 55.3 | 36 | ODV-associated protein | 11 |

| 14 | 45 | ha44 | Ha44 | 42.8 | 29 | Nucleocapsid-associated protein | This study | |

| 15 | 44 | ha44 | Ha44 | 42.8 | 32 | Nucleocapsid-associated protein | This study | |

| ha89 | ac101 | C42 | 42.6 | 20 | Nucleocapsid | 10 | ||

| 16 | 42 | ha96 | ac46 | ODV-E66 | 76.1 | 15 | ODV envelope | 26 |

| ha89 | ac101 | C42 | 42.6 | 18 | Nucleocapsid | 10 | ||

| 17 | 39 | ha94 | ac109 | ODV-EC43 | 41.5 | 45 | ODV envelope and nucleocapsid | 19 |

| 18 | 38 | ha94 | ac109 | ODV-EC43 | 41.5 | 51 | ODV envelope and nucleocapsid | 19 |

| ha84 | ac95 | Helicase | 146 | 10 | DNA replication essential | 11, 32 | ||

| 19 | 36 | ha15 | ac148 | ODV-E56 | 38.9 | 24 | ODV envelope | 8 |

| 20 | 35 | ha9 | ac142 | p49 | 55.3 | 29 | ODV-associated protein | 11 |

| ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 35 | Nucleocapsid | 45 | ||

| 21 | 34 | ha73 | ac80 | GP41 | 36.6 | 58 | Tegument main protein | 63, 64 |

| 22 | 33 | ha1 | ac8 | Polyhedrin | 28.8 | 38 | Polyhedron main protein | 49 |

| 23 | 32 | ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 50 | Nucleocapsid | 45 |

| ha11 | ac144 | ODV-EC27 | 33.3 | 32 | ODV envelope and nucleocapsid | 3, 9 | ||

| 24 | 30 | ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 42 | Nucleocapsid | 45 |

| ha1 | ac8 | Polyhedrin | 28.8 | 34 | Polyhedron main protein | 49 | ||

| 25 | 29 | ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 57 | Nucleocapsid | 45 |

| 26 | 28 | ha82 | ac94 | ODV-E25 | 25.9 | 41 | ODV envelope | 51 |

| 27 | 27 | ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 56 | Nucleocapsid | 45 |

| ha80 | ac92 | P33 | 30.8 | 34 | Stimulation of P53-induced apoptosis | 48 | ||

| 28 | 26 | ha80 | ac92 | P33 | 30.8 | 44 | Stimulation of P53-induced apoptosis | 48 |

| 29 | 25 | ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 45 | Nucleocapsid | 45 |

| ha15 | ac148 | ODV-E56 | 38.9 | 24 | ODV envelope | 8 | ||

| 31 | 23.5 | ha80 | ac92 | P33 | 30.8 | 32 | Stimulation of P53-induced apoptosis | 48 |

| 32 | 22 | ha1 | ac8 | Polyhedrin | 28.8 | 28 | Polyhedron main protein | 49 |

| ha67 | ac65 | DNA polymerase | 119.3 | 11 | DNA replication essential | 11, 32 | ||

| 34 | 20 | ha1 | ac8 | Polyhedrin | 28.8 | 28 | Polyhedron main protein | 49 |

| 35 | 19 | ha82 | ac94 | ODV-E25 | 25.9 | 45 | ODV envelope | 51 |

| 36 | 18.5 | ha78 | ac89 | VP39 | 33.4 | 40 | Nucleocapsid | 45 |

| ha9 | ac142 | P49 | 55.3 | 18 | ODV-associated protein | 11 | ||

| 37 | 18 | ha88 | ac100 | P6.9 | 11.5 | 35 | DNA binding protein | 65, 66 |

| 38 | 15 | ha10 | ac143 | ODV-E18 | 8.8 | 45 | ODV envelope | 9 |

| 39 | 14 | ha10 | ac143 | ODV-E18 | 8.8 | 45 | ODV envelope | 9 |

| 41 | 12 | ha82 | ac94 | ODV-E25 | 25.9 | 40 | ODV envelope | 51 |

| ha65 | ac67 | LEF-3 | 44 | 20 | DNA replication essential | 11, 32 |

The order of the bands was the same as that in Fig. 1. MALDI-TOF MS was repeated once.

Of these 23 proteins, VP39 (57), P78/83 (59), VP80 (38, 41), and ODV/BV-C42 (10) have been reported previously as nucleocapsid proteins of both BV and ODV. P6.9 is the main basic DNA-binding protein located in the nucleocapsid (65, 66). GP41 is defined as the tegument protein of ODVs (63, 64). ODV-E18 (9), ODV-E25 (51), ODV-E56 (8), and ODV-E66 (26), as well as oral infectivity-related proteins P74 (21, 34, 68) and PIF-1 (31), were reported to be the ODV envelope proteins. ODV-EC27 (5, 9) and ODV-EC43 (19) were reported as structural proteins of the ODV nucleocapsid and envelope. P33 (48), P49, AC66, helicase, LEF-3, DNA polymerase, and polyhedrin were reported as ODV-associated proteins (11). Two proteins, HA44 and HA100, have not been reported before and therefore are being described in more detail here.

Peptide mass fingerprinting data interpretation by the MS-Fit program revealed that 11 experimentally derived tryptic peptide masses were found to match the predicted peptide masses of the HA44 protein (error, <100 ppm), covering 29% of its amino acid sequence. For HA100, 10 experimentally derived peptide masses were found to match the predicted peptide masses of the HA100 protein (error, <100 ppm), covering 26% of its amino acid sequence. By using Mascot software for database searches (25), high Mascot score were revealed when matched with HA44 and HA100, respectively (>67).

Sequence and phylogeny analysis of ha44 and ha100.

Sequence analysis indicated that ha44 contains 1,134 nucleotides (nt) and potentially encodes a protein of 378 aa with a predicted molecular mass of 42.8 kDa. A baculovirus late transcription motif, TAAG, was found 76 nt upstream of the initial ATG of ha44, suggesting that it is a late gene. No polyadenylation signal was found within 500 nt downstream of the stop codon.

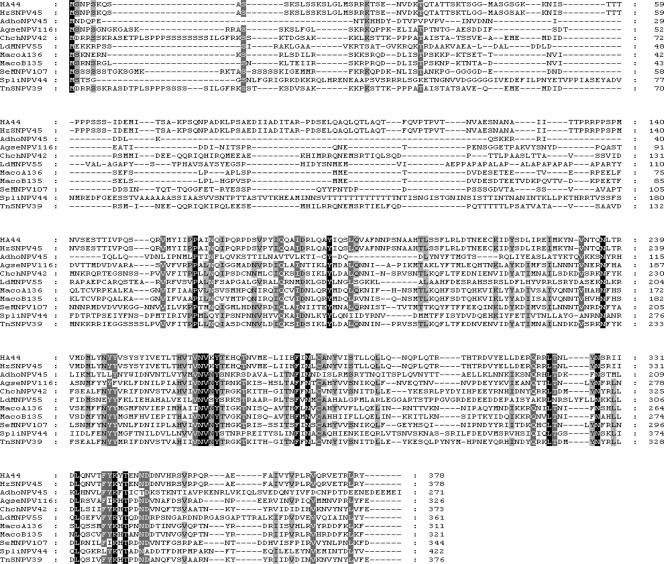

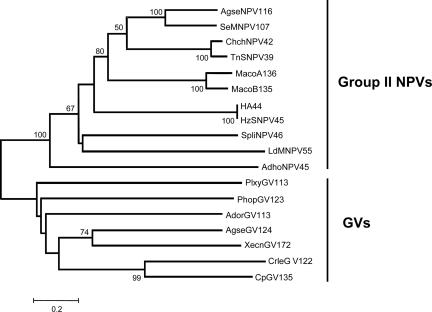

Searches of databases with all of the available genomes of baculoviruses showed that homologues of HA44 were found in all group II NPVs and GVs but not in group I NPVs or in the dipteran and hymenopteran NPVs. The size of the HA44 homologue varies, ranging from the 255 aa of ORF45 of Adoxophyes honmai NPV (AdhoNPV45) to the 422 aa of ORF46 of Spodoptera litura NPV (SpliNPV46), although most of the homologues have a size of 311 to 378 aa. Pairwise comparisons revealed that three proteins were very similar to their counterparts. The amino acid identities were 98%, 83%, and 75% for HA44/HzSNPV45, ChchNPV42/TnSNPV39, and MacoA136/MacoB135, respectively (for definitions of abbreviations, see the legend to Fig. 2). In contrast, the amino acid identity for the rest of the pairwise results was lower than 50%. The alignment of HA44 homologues from group II NPVs is presented in Fig. 2. The protein is mostly conserved at the C terminus (Fig. 2). The N-terminal sequence of HA44 is rich in basic residues (K/R) and serine, and this is a common feature of most of the HA44 homologues. The isoelectric point (pI) of the N-terminal 64 aa of HA44 is 10.79. Only 12 aa were absolutely conserved in the alignment, which included N236, N264, V265, Y267, F281, N283, L322, N327, L333, K340, T342, and V369 (Fig. 2). These amino acids might be important in the function of HA44. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the HA44 homologues have a common ancestor and then diverged into the cluster of group II NPVs and that of GVs (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of HA44 and its homologues among the group II NPVs. Three shading levels were set, black for 100% identity, dark gray for 80% identity, and light gray for 60% identity. The NCBI accession numbers are NP_818692 for AdhoNPV45, YP_529786 for ORF116 of Agrotis segetum NPV (AgseNPV116), YP_249646 for ORF42 of Chrysodeixis chalcites NPV (ChchNPV42), NP_075113 for HA44, NP_542668 for ORF45 of HzSNPV45, NP_047691 for ORF55 of Lymantria dispar NPV (LdMNPV55), NP_613219 for ORF136 of Mamestra configurata NPV A (MacoA136), NP_689309 for ORF135 of Mamestra configurata NPV B (MacoB135), NP_037867 for ORF107 of Spodoptera exigua NPV (SeMNPV107), NP_258314 for ORF44 of Spodoptera litura NPV (SpliNPV44), and YP_308929 for ORF39 of Trichoplusia ni NPV (TnSNPV39).

FIG. 3.

Neighbor-joining tree derived from HA44 and its homologues among NPVs and GVs. Bootstrap values (1,000 replicates, nodes supported with more than 50%) are on the branch lines. The accession numbers for NPVs are as described in the legend to Fig. 3. The additional ones are NP_872567 for ORF113 of Adoxophyes orana GV (AdorGV113), YP_006220 for ORF124 of Agrotis segetum GV (AgseGV124), NP_891969 for ORF122 of Cryptophlebia leucotreta GV (CrleGV122), NP_148919 for ORF135 of Cydia pomonella GV (CpGV135), NP_663288 for ORF123 of Phthorimaea operculella GV (PhopGV123), NP_068332 for ORF113 of Plutella xylostella GV (PlxyGV113), and NP_059320 for ORF172 of Xestia c-nigrum GV (XecnGV172).

The Ha100 ORF is 1,530 nt and encodes a protein of 510 aa with a predicted molecular mass of 58 kDa. No consensus early transcription initiation motifs were found upstream of the initial ATG, but a TAAG motif was found at −34 nt, suggesting that ha100 may also be a late gene. A polyadenylation signal (AATAAA) was found at 22 to 27 nt downstream of the stop codon.

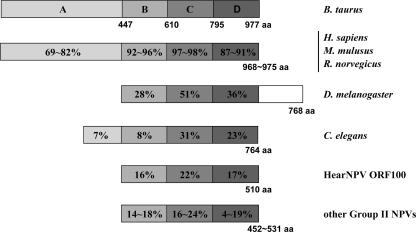

HA100 has homology to poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (PARG), a ubiquitously expressed exo- and endoglycohydrolase in eukaryotic cells. PARG mediates oxidative and excitotoxic neuronal death and is involved in the breakdown and recruitment of polyribose for nuclear functions such as DNA replication and repair (17, 69). The vertebrate PARGs contain four domains, A, B, C, and D (43). Domain A is a putative regulatory domain, while B, C, and D form catalytic fragments. Homologues of HA100 are conserved in all of the group II NPVs sequenced so far. A comparison of PARGs from a range of organisms and from group II NPVs is shown in Fig. 4. Similar to the PARG of Drosophila melanogaster, the PARG-like proteins of group II NPVs contain a catalytic fragment but lack the putative regulatory A domain (Fig. 4). Alignment of HA100 homologues from baculoviruses and PARGs from selected eukaryotes reveals that although the sequence similarity is not high, there were 7 aa absolutely conserved, including F662, K676, Y683, G745, E756, P764, and E765, with respect to the bovine PARG sequence (data not shown). All of the conserved amino acids are located in the conserved catalytic domain, which spans residues 610 to 795 in bovine PARG (43).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of PARGs from a wide range of organisms and from group II NPVs. A, putative regulatory domain; B, C, and D, catalytic fragments; C, PARG catalytic domain. Percent conservation is indicated in each block with respect to the bovine PARG. The amino acid positions of bovine PARG domains and the lengths of PARGs are indicated. The accession numbers of PARGs are NP_776563 for Bos taurus, AAH52966 for Homo sapiens, NP_036090 for Mus musculus, NP_112629 for Rattus norvegicus, NP_477321 for Drosophila melanogaster, NP_501508 for Caenorhabditis elegans, NP_075169 for HA100, NP_818756 for AdhoNPV, YP_529728 for AgseNPV, YP_249712 for ChchNPV, NP_542726 for HzSNPV, NP_047778 for LdMNPV, NP_613153 for MacoNPV A, NP_689244 for MacoNPV B, NP_037812 for SeMNPV, NP_258370 for SpliNPV, and YP_308992 for TnSNPV.

Localization of HA44 and HA100 in viral structures.

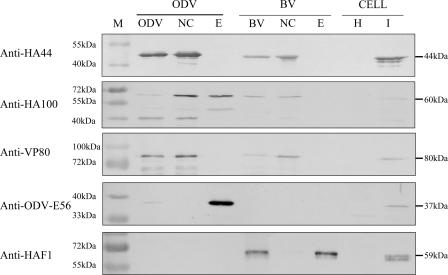

Anti-HA44 and anti-HA100 antisera were generated as described in Materials and Methods and were used in Western blot analysis and IEM. Western blot analyses were performed to identify the localization of HA44 and HA100 in BV and ODV (Fig. 5). The results showed that HA44 is located in the nucleocapsid but not in the envelope of ODV and BV. HA100 was detected in the nucleocapsid and envelope of ODV, as well as in the nucleocapsid of BV (Fig. 5). The sizes of HA44 and HA100 were 44 kDa and 60 kDa, respectively, which are in agreement with the predicted sizes deduced from their nucleotide sequences.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of the HearNPV ODV/BV nucleocapsid (NC) and envelope (E) fractions with anti-HA44 and anti-HA100 antibodies. Healthy HzAM1 cells (H) and virus-infected cells (I) were loaded as negative and positive controls. VP80, ODV-E56, and the F protein were detected by their specific antibodies for illustrating the NC-specific protein, ODV E-specific protein, and BV E-specific protein, respectively. M, molecular size markers.

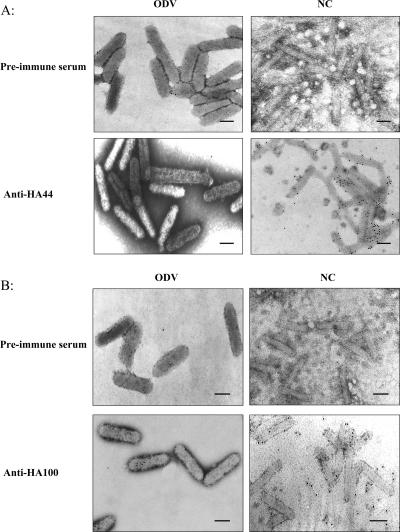

The IEM results showed that HA44 was located in the nucleocapsid of ODV but not detected in the envelopes of the intact ODV (Fig. 6A). HA100 was detected in intact ODVs, as well as in the nucleocapsids of ODV (Fig. 6B). The IEM results confirmed that HA44 is a nucleocapsid protein of HearNPV ODV, while HA100 is a structural protein of both the nucleocapsid and the envelope of the ODV.

FIG. 6.

IEM of HA44 and HA100 and localization in HearNPV ODVs and nucleocapsids (NC) of ODVs. A 1:100 dilution of anti-HA44 or anti-HA100 antiserum was used as the primary antibody. Preimmune serum was used as a negative control. A, IEM of HA44; B, IEM of HA100. Bars, 100 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified 23 HearNPV genes that encode ODV structural proteins by SDS-PAGE and MS methods. This is the first such report for a group II NPV.

Braunagel et al. (11) were able to identify 44 ODV-associated proteins of AcMNPV by using multiple techniques, including MALDI-TOF, multidimensional protein identification technology-tandem MS, library exploring, and Western blotting. Perera et al. (46) identified 44 polypeptides in CuniNPV ODV by MALDI-TOF and gel electrophoresis-liquid chromatography-tandem MS. Comparison of the ODV-associated proteins of AcMNPV, CuniNPV, and HearNPV shows that nine proteins are shared by these viruses and are also conserved in the baculoviruses sequenced so far. AcMNPV and CuniNPV ODVs shared another five conserved baculovirus proteins, i.e., PIF2, F protein, VP1054, VLF-1, and VP91, which were not detected in HearNPV by MS. However, PIF2 was identified as a HearNPV ODV structural protein by Western blot analysis (20). Therefore, at least 10 conserved baculovirus proteins are shared by ODVs of AcMNPV, CuniNPV, and HearNPV, including P49, ODV-EC27, ODV-E56, P74, GP41, VP39, P33, P6.9, ODV-EC43, and PIF-2. Another protein conserved in baculoviruses, PIF1, was identified as an ODV component in HearNPV in our study and was also reported as an ODV-associated protein in CuniNPV (46) but was not identified by multiple approaches in AcMNPV (13). DNA polymerase and helicase are conserved baculovirus proteins shared by the ODVs of both AcMNPV and HearNPV, but they were not detected in the CuniNPV ODV (46). The identification of common structural proteins is essential to elucidate the core structure of baculoviruses. Of the 10 conserved proteins, ODV-EC27, ODV-E56, GP41, VP39, P6.9, and ODV-EC43 are known to be structural proteins. It is interesting that P74 and PIF-2, which are essential for oral infection, are also associated with the ODV. With more data derived from different viruses becoming available, the importance and functions of these proteins can be further revealed.

In this study, approximately 41 ODV protein bands separated by SDS-PAGE were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS analysis; 38 bands had matches to viral ORFs, while 3 bands did not produce significant matches and were not identified by this technique (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The finding of unmatched bands suggested that additional host proteins may be present. In vaccinia virus, MS techniques revealed 23 virion-associated host proteins in addition to the 75 viral proteins (16). Our HearNPV ODV data have not matched any host proteins; this may be due to the lack of genetic information about or a database for H. armigera. Some proteins of HearNPV ODV were not identified, possibly because of their low molar content in ODVs and/or resistance to staining or because some proteins may not be amenable to MALDI-TOF MS. For example, HA122 and PIF-2 have already been identified and located in the HearNPV ODV (37, 20) but we were not able to detect them in this study.

The degradation or losses of proteins during virus purification could also affect protein detection. Although HgCl2 treatment, heat inactivation of proteases, and a protease inhibitor cocktail were used during the purification of virions, multiple bands of a single protein were still present in the gel, including those of polyhedrin, VP39, GP41, P49, P33, ODV-E66, ODV-E56, and ODV-E25 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Similar results were observed for a single protein during an investigation of the CuniNPV ODV (46). Various factors can be responsible for the fragility of some proteins, including the refractory profile of alkaline proteases and the different methods used in virus purification (11, 54); however, we cannot exclude the possibility of some protein degradation during the experimental procedures. On the other hand, there may be polymorphisms, oligomerization, and posttranslational modification of the gene products in the matrix of ODVs.

During data mining by MS-Fit, some peptide footprints were matched to HearNPV ORFs but with a low MOWSE score, such as ha26, ie1, me53, bro-b, bro-c, alk-exo, pk1, ha133 (F-protein gene), etc. Therefore, they were not included as ODV structural proteins in our results. Some of them, such as IE1, Alk-exo, and the F protein, were found to be located in the ODVs of AcMNPV (11), while the F protein and Bro were identified in the ODVs of CuniNPV (46). The importance of using multiple techniques to identify ODV structural proteins has been elucidated by Braunagel et al. (11). We are using antibodies against HearNPV ORFs to verify the protein localization in the ODV by Western blot analysis and IEM. Location of the above proteins in the ODV awaits confirmation pending the preparation of specific antibodies.

Two structural proteins of HearNPV ODV, HA44 and HA100, were newly identified here. ORF ha44 contains a TAAG late gene promoter motif, which is in agreement with its function as a structural protein. Western blot analysis has confirmed that HA44 was a nucleocapsid component in both BV and ODV with a molecular mass of 44 kDa. Homologues of HA44 were found in all of the group II NPVs and GVs whose complete sequences have been determined but not in group I NPVs or dipteran or hymenopteran baculoviruses. It is generally believed that GVs separated from the ancestor of NPVs and GVs before the radiation of group I and group II NPVs (35). It is therefore likely that the ancestor of HA44 existed in both NPV and GV but was lost during the emergence of group I NPVs.

Western blot analysis and IEM revealed that HA100 is a component of the nucleocapsid and the envelope of ODV. HA100 is conserved in all group II NPVs, and it is a homologue of PARG. PARG is critical for the maintenance of steady-state poly(ADP-ribose) levels and plays important roles in modulating chromatin structure, transcription, DNA repair, and apoptosis (6). It is interesting that the members of NPV group II encode a PARG-like protein as a structural protein. It remains to be determined whether the PARG-like proteins in group II NPVs are enzymatically functional.

With the knowledge of baculovirus ODV composition, it is possible to study the functions of the relevant proteins and their potential role during virus primary infection (11). In this study, we identified two new ODV structural proteins, HA44 and HA100. Currently we are investigating the biological functions of these two proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a 973 project (2003CB114202), an NSFC key project from China (30630002), and a joint PSA project from China and The Netherlands (2004CB720404).

We acknowledge the State Key Laboratory of Virology Proteomics/MS Center (Wuhan University) and Shanghai GeneCore BioTechnologies Co. Ltd. for technical support. We thank Jian-Lan Yu and Fang-Ke Huang for assistance with the experiments.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Meyers, and D. J. Lipman. 1992. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene and Wiley InterScience, New York, NY.

- 3.Belyavskyi, M., S. C. Braunagel, and M. D. Summers. 1998. The structural protein ODV-EC27 of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus is a multifunctional viral cyclin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:11205-11210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blissard, G., and J. R. Wenz. 1992. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66:6829-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blissard, G., B. Black, N. Crook, B. A. Keddie, R. Possee, G. Rohrmann, D. Theilmann, and L. E. Volkman. 2000. Baculoviridae: taxonomic structure and properties of the family, p. 195-202. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel, C. M. Fauquet, D. H. L. Bishop, E. B. Carstens, M. K. Estes, S. M. Lemon, J. Maniloff, M. A. Mayo, D. J. McGeoch, C. R. Pringle, and E. B. Wickner (ed.), Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 6.Bonicalzi, M. E., J. F. Haince, A. Droit, and G. G. Poirier. 2005. Regulation of poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase: where and when? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:739-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braunagel, S. C., and M. D. Summers. 1994. Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus, PDV, and ECV viral envelopes and nucleocapsids: structural proteins, antigens, lipid and fatty acid profiles. Virology 202:315-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braunagel, S. C., D. M. Elton, H. Ma, and M. D. Summers. 1996. Identification and analysis of an Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus structural protein of the occlusion-derived virus envelope: ODV-E56. Virology 217:97-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunagel, S. C., H. He, P. Ramamurthy, and M. D. Summers. 1996. Transcription, translation, and cellular localization of three Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus structural proteins: ODV-E18, ODV-E35, and ODV-EC27. Virology 222:100-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunagel, S. C., P. A. Guidry, G. Rosas-Acosta, L. Engelking, and M. D. Summers. 2001. Identification of BV/ODV-C42, an Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus orf101-encoded structural protein detected in infected-cell complexes with ODV-EC27 and p78/83. J. Virol. 75:12331-12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braunagel, S. C., W. K. Russell, G. Rosas-Acosta, D. H. Russell, and M. D. Summers. 2003. Determination of the protein composition of the occlusion-derived virus of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:9797-9802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, X. W., W. F. J. IJkel, C. Dominy, P. M. de Andrade Zanotto, Y. Hashimoto, O. Faktor, T. Hayakawa, H. Wang, A. Premkumar, S. Mathavan, P. J. Krell, Z. Hu, and J. M. Vlak. 1999. Identification, sequence analysis and phylogeny of the lef-2 gene of Helicoverpa armigera single-nucleocapsid baculovirus. Virus Res. 65:21-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, X. W., W. F. J. IJkel, R. Tarchini, X. L. Sun, H. Sandbrink, H. L. Wang, S. Peters, D. Zuidema, R. K. Lankhorst, J. M. Vlak, and Z. H. Hu. 2001. The sequence of the Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 82:241-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, X. W., Z. H. Hu, and J. M. Vlak. 1997. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the polyhedrin gene of Heliothis armigera single nucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virol. Sin. 12:346-353. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, X. W., Z. H. Hu, J. A. Jehle, and J. M. Vlak. 1997. Characterization of the ecdysteroid UDP-glucosyltransferase gene of Heliothis armigera single-nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virus Genes 15:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung, C. S., C. H. Chen, M. Y. Ho, C. Y. Huang, C. L. Liao, and W. Chang. 2006. Vaccinia virus proteome: identification of proteins in vaccinia virus intracellular mature virion particles. J. Virol. 80:2127-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Amours, D., S. Desnoyers, I. D'Silva, and G. G. Poirier. 1999. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem. J. 342:249-268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong, C., D. Li, G. Long, F. Deng, H. Wang, and Z. Hu. 2005. Identification of functional domains of HearNPV P10 for filament formation. Virology 338:112-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang, M. G., H. Wang, L. Yuan, X. W. Chen, J. M. Vlak, and Z. H. Hu. 2003. Open reading frame 94 of Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus encodes a novel occlusion-derived virion protein, ODV-EC43. J. Gen. Virol. 84:3021-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fang, M. G., Y. Nie, Q. Wang, F. Deng, R. Wang, H. Wang, H. Wang, J. M. Vlak, X. Chen, and Z. Hu. 2006. Open reading frame 132 of Heliocoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus encodes a functional per os infectivity factor (PIF-2). J. Gen. Virol. 87:2563-2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faulkner, P., J. Kuzio, G. V. Williams, and J. A. Wilson. 1997. Analysis of p74, a PDV envelope protein of Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus required for occlusion body infectivity in vivo. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3091-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan, K. L., and J. E. Dixon. 1991. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal. Biochem. 192:262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herniou, E. A., J. A. Olszewski, D. R. O'Reilly, and J. S. Cory. 2004. Ancient coevolution of baculoviruses and their insect hosts. J. Virol. 78:3244-3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herniou, E. A., J. A. Olszewski, J. S. Cory, and D. R. O'Reilly. 2003. The genome sequence and evolution of baculoviruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 48:211-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirosawa, M., M. Hoshida, M. Ishikawa, and T. Toya. 1993. MASCOT: multiple alignment system for protein sequences based on three-way dynamic programming. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 9:161-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong, T., S. C. Braunagel, and M. D. Summers. 1994. Transcription, translation, and cellular localization of PDV-E66: a structural protein of the PDV envelope of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology 204:210-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.IJkel, W. F., M. Westenberg, R. W. Goldbach, G. W. Blissard, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2000. A novel baculovirus envelope fusion protein with a proprotein convertase cleavage site. Virology 275:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.IJkel, W. F., R. J. Lebbink, M. L. Op den Brouw, R. W. Goldbach, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2001. Identification of a novel occlusion derived virus-specific protein in Spodoptera exigua multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 284:170-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jehle, J. A., M. Lange, H. Wang, Z. Hu, Y. Wang, and R. Hauschild. 2006. Molecular identification and phylogenetic analysis of baculoviruses from Lepidoptera. Virology 346:180-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keddie, B. A., G. W. Aponte, and L. E. Volkman. 1989. The pathway of infection of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus in an insect host. Science 243:1728-1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kikhno, I., S. Gutierrez, L. Croizier, G. Croizier, and M. L. Ferber. 2002. Characterization of pif, a gene required for the per os infectivity of Spodoptera littoralis nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 83:3013-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kool, M., C. H. Ahrens, R. W. Goldbach, G. F. Rohrmann, and J. M. Vlak. 1994. Identification of genes involved in DNA replication of the Autographa californica baculovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:11212-11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar, S., K. Tamura., and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzio, J., R. Jaques, and P. Faulkner. 1989. Identification of p74, a gene essential for virulence of baculovirus occlusion bodies. Virology 173:759-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lange, M., H. Wang, Z. Hu, and J. A. Jehle. 2004. Towards a molecular identification and classification system of lepidopteran-specific baculoviruses. Virology 325:36-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Long, G., M. Westenberg, H. L. Wang, J. M. Vlak, and Z. H. Hu. 2006. Function, oligomerization and N-linked glycosylation of the Helicoverpa armigera SNPV envelope fusion protein. J. Gen. Virol. 87:839-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long, G., X. W. Chen, D. Peters, J. M. Vlak, and Z. H. Hu. 2003. Open reading frame 122 of Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus encodes a novel structural protein of occlusion-derived virions. J. Gen. Virol. 84:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu, A., and E. B. Carstens. 1992. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the p80 gene of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus: a homologue of the Orgyia pseudotsugata nuclear polyhedrosis virus capsid-associated gene. Virology 190:201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McIntosh, A. H., and C. M. Ignoffo. 1983. Characterization of 5 cell lines established from species of Heliothis. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 18:262-269. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monsma, S. A., A. G. Oomens, and G. W. Blissard. 1996. The GP64 envelope fusion protein is an essential baculovirus protein required for cell-to-cell transmission of infection. J. Virol. 70:4607-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muller, R., M. N. Pearson, R. L. Russell, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1990. A capsid-associated protein of the multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus of Orgyia pseudotsugata: genetic location, sequence, transcriptional mapping, and immunocytochemical characterization. Virology 176:133-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Notredame, C., D. Higgins, and J. Heringa. 2000. T-Coffee: a novel method for multiple sequence alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 302:205-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel, C. N., D. W. Koh, M. K. Jacobson, and M. A. Oliveira. 2005. Identification of three critical acidic residues of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase involved in catalysis: determining the PARG catalytic domain. Biochem. J. 388:493-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson, M. N., C. Groten, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2000. Identification of the Lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus envelope fusion protein provides evidence for a phylogenetic division of the Baculoviridae. J. Virol. 74:6126-6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pearson, M. N., R. L. Russell, G. F. Rohrmann, and G. S. Beaudreau. 1988. p39, a major baculovirus structural protein: immunocytochemical characterization and genetic location. Virology 167:407-413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perera, O., T. B. Green, S. M. Stevens, Jr., S. White, and J. J. Becnel. 2007. Proteins associated with Culex nigripalpus nucleopolyhedrovirus occluded virions. J. Virol. 81:4585-4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pham, D. Q., R. H. Hice, N. Sivasubramanian, and B. A. Federici. 1993. The 1629-bp open reading frame of the Autographa californica multinucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus encodes a virion structural protein. Gene 137:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Prikhod'ko, G. G., Y. Wang, E. Freulich, C. Prives, and L. K. Miller. 1999. Baculovirus p33 binds human p53 and enhances p53-mediated apoptosis. J. Virol. 73:1227-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohrmann, G. F. 1986. Polyhedrin structure. J. Gen. Virol. 67:1499-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohrmann, G. F. 1992. Baculovirus structural proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 73:749-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russell, R. L., and G. F. Rohrmann. 1993. A 25-kDa protein is associated with the envelopes of occluded baculovirus virions. Virology 195:532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russell, R. L., C. J. Funk, and G. F. Rohrmann. 1997. Association of a baculovirus-encoded protein with the capsid basal region. Virology 227:142-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shevchenko, A., M. Wilm, O. Vorm, and M. Mann. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Summers, M. D., and G. E. Smith. 1975. Trichoplusia ni granulosis virus granulin: a phenol-soluble, phosphorylated protein. J. Virol. 16:1108-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun, X. L., G. Y. Zhang, Z. X. Zhang, Z. H. Hu, J. M. Vlak, and B. M. Arif. 1998. In vivo cloning of Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus genotypes. Virol. Sin. 13:83-88. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun, X. L., and G. Y. Zhang. 1994. A comparison of four wild isolates of Heliothis nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virol. Sin. 9:309-318. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thiem, S. M., and L. K. Miller. 1989. Identification, sequence, and transcriptional mapping of the major capsid protein gene of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 63:2008-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The ClustalX Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vialard, J. E., and C. D. Richardson. 1993. The 1,629-nucleotide open reading frame located downstream of the Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus polyhedrin gene encodes a nucleocapsid-associated phosphoprotein. J. Virol. 67:5859-5866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, H., D. Wu, F. Deng, H. Peng, X. Chen, H. Lauzon, B. M. Arif, J. A. Jehle, and Z. Hu. 2004. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the chitinase gene from the Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virus Res. 100:179-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, H., X. W. Chen, B. M. Arif, J. M. Vlak, and Z. H. Hu. 2001. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of a putative basic DNA-binding protein of Helicoverpa armigera nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virus Genes 22:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Washburn, J. O., B. A. Kirkpatrick, and L. E. Volkman. 1995. Comparative pathogenesis of Autographa californica M nuclear polyhedrosis virus in larvae of Trichoplusia ni and Heliothis virescens. Virology 209:561-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whitford, M., and P. Faulkner. 1992. A structural polypeptide of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus contains O-linked N-acetylglucosamine. J. Virol. 66:3324-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitford, M., and P. Faulkner. 1992. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of a gene encoding gp41, a structural glycoprotein of the baculovirus Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J. Virol. 66:4763-4768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilson, M. E., and K. H. Price. 1988. Association of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus (AcMNPV) with the nuclear matrix. Virology 167:233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson, M. E., T. H. Mainprize, P. D. Friesen, and L. K. Miller. 1987. Location, transcription, and sequence of a baculovirus gene encoding a small arginine-rich polypeptide. J. Virol. 61:661-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu, D., F. Deng, X. Sun, H. Wang, L. Yuan, J. M. Vlak, and Z. Hu. 2005. Functional analysis of FP25K of Helicoverpa armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2439-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yao, L., W. Zhou, H. Xu, Y. Zheng, and Y. Qi. 2004. The Heliothis armigera single nucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus envelope protein P74 is required for infection of the host midgut. Virus Res. 104:111-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ying, W., M. B. Sevigny, Y. Chen, and R. A. Swanson. 2001. Poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase mediates oxidative and excitotoxic neuronal death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:12227-12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zanotto, P. M., B. D. Kessing, and J. E. Maruniak. 1993. Phylogenetic interrelationships among baculoviruses: evolutionary rates and host associations. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 62:147-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang, G. 1994. Research, development and application of Heliothis viral pesticide in China. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Valley 3:1-6. [Google Scholar]