Abstract

Mating in Candida albicans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae is regulated by the secretion of peptide pheromones that initiate the mating process. An important regulator of pheromone activity in S. cerevisiae is barrier activity, involving an extracellular aspartyl protease encoded by the BAR1 gene that degrades the alpha pheromone. We have characterized an equivalent barrier activity in C. albicans and demonstrate that the loss of C. albicans BAR1 activity results in opaque a cells exhibiting hypersensitivity to alpha pheromone. Hypersensitivity to pheromone is clearly seen in halo assays; in response to alpha pheromone, a lawn of C. albicans Δbar1 mutant cells produces a marked zone in which cell growth is inhibited, whereas wild-type strains fail to show halo formation. C. albicans mutants lacking BAR1 also exhibit a striking mating defect in a cells, but not in α cells, due to overstimulation of the response to alpha pheromone. The block to mating occurs prior to cell fusion, as very few mating zygotes were observed in mixes of Δbar1 a and α cells. Finally, in a barrier assay using a highly pheromone-sensitive strain, we were able to demonstrate that barrier activity in C. albicans is dependent on Bar1p. These studies reveal that a barrier activity to alpha pheromone exists in C. albicans and that the activity is analogous to that caused by Bar1p in S. cerevisiae.

Candida albicans a and α cells secrete peptide mating pheromones (a-factor and α-factor, respectively) that act on cells of the opposite mating type and induce physiological changes that precede cell fusion (4, 9, 29, 36, 41). These changes include arrest of the cell in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and the formation of mating projections that seek out a partner of the opposite mating type for cell fusion (3, 52). The pathway controlling the response to mating pheromones in C. albicans shows many similarities with that of the related yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Both fungi use a conserved mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade to transduce the mating signal from a pheromone receptor-coupled G protein to a transcriptional response in the nucleus (6, 31). The final step in the signaling cascade leads to the activation of the transcription factor Ste12p (Cph1p in C. albicans) and the resulting expression of many pheromone-responsive genes (for reviews of mating in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae, see references 2, 14, 27, 33, and 46).

Despite many similarities between the regulation of mating in C. albicans and S. cerevisiae, there are also a number of important differences. Prominent among these is the requirement in C. albicans for cells to undergo a heritable but reversible transition from the white phase to the opaque phase for efficient mating (36). The white-opaque transition is a form of phenotypic switching, and only in the opaque phase do C. albicans cells respond strongly to pheromone and undergo mating (3, 4, 28, 29, 36, 41). White-opaque switching is regulated by the a1-α2 heterodimer, so only mating-competent cells, i.e., a or α cells, are able to switch to the opaque phase (36). The white-opaque switch involves differential regulation of a large number of genes, including several that are implicated in mating (26).

White-opaque switching may have evolved to enable efficient mating in the in vivo niche of C. albicans, i.e., a mammalian host (17, 23). Unlike S. cerevisiae, which is commonly found growing in the soil or on the surfaces of fruit, C. albicans is a natural commensal of humans and an opportunistic pathogen, with the potential to cause both mucosal and systemic infections (13). Mating of C. albicans cells has been shown to occur in vivo, using animal models of systemic infection and skin infection and, more recently, a gastrointestinal tract model of commensal growth (12, 21, 24). White-opaque switching and the mating response have also been implicated in increasing the efficiency of formation of C. albicans biofilms (8). The in vivo role of white-opaque switching and mating in C. albicans is still under investigation, however, particularly given the apparent absence of a meiotic pathway to complete a true sexual mating cycle (2, 23, 33, 46).

The response of C. albicans cells to mating pheromone is dependent not only on the white or opaque phase of the cell but also on nutritional conditions (3). Under optimal medium conditions, the pheromone response of opaque cells of C. albicans involves the differential regulation of more than 200 genes, and relatively few of these genes overlap with those regulated by pheromone in S. cerevisiae (3). Even under optimal conditions, however, wild-type C. albicans cells fail to undergo complete cell cycle arrest in the presence of pheromone (3, 10, 41). In contrast, S. cerevisiae cells responding to pheromone efficiently arrest their growth in the G1 phase of the cell cycle, and this is often visualized by the formation of halos of growth inhibition in a lawn of responding cells (35). C. albicans strains do not exhibit clear areas of growth inhibition in the halo assay, although mutant strains that are hypersensitive to pheromone can produce halos, demonstrating more efficient cell cycle arrest. An example of a hypersensitive C. albicans strain is one lacking the SST2 gene, which encodes a regulator of G protein signaling (10). Disruption of SST2 resulted in heightened signaling via the MAP kinase cascade, and opaque a cells exhibited increased sensitivity to alpha pheromone and enhanced growth inhibition in the halo assay.

In S. cerevisiae, MATa mating cells also have an extracellular barrier activity that antagonizes alpha pheromone. Barrier activity involves the secretion of an aspartyl protease in a cells that acts specifically to degrade alpha pheromone and is encoded by the BAR1 (SST1) gene (30). The loss of barrier activity results in S. cerevisiae a cells that are hypersensitive to pheromone: cells produce significantly larger areas of growth inhibition in the halo assay but have a reduced mating efficiency (5, 19, 35, 47). In this paper, we address whether an ortholog of ScBAR1 exists in C. albicans and if deletion of the gene leads to a hypersensitive phenotype in opaque a cells. We provide evidence that orf19.2082 in C. albicans encodes a protein with barrier activity (C. albicans Bar1p) against alpha pheromone. In addition, we examine the regulation of other aspartyl proteases, including those encoded by the SAP (secreted aspartyl protease) family of genes, by mating pheromone in C. albicans. These studies reveal that degradation of pheromone is highly specific to Bar1p in C. albicans and that members of the SAP family of proteases do not act on alpha pheromone. A second aspartyl protease in C. albicans, encoded by the YPS7 gene, also shows a limited ability to degrade α-factor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and reagents.

Standard laboratory media were prepared as described previously (18). Spider medium contained 1.35% agar, 1% nutrient broth, 0.4% potassium phosphate, and 2% mannitol (pH 7.2). Alpha pheromone peptide (GFRLTNFGYFEPG) was synthesized by Genemed Synthesis.

Strains.

The C. albicans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Newly constructed strains were derived from SNY152 (40) and 3294 (32). First, a and α derivatives of SNY152 were generated by growth on sorbose medium, as previously described (4, 22), to create RBY1132 (a/a) and RBY1133 (α/α). PCR products for targeting the BAR1 open reading frame (ORF) were generated using oligonucleotides 1 and 2 to amplify the 5′ flank of BAR1 and oligonucleotides 3 and 4 to amplify the 3′ flank of BAR1. PCR products for targeting the YPS7 ORF were similarly generated from oligonucleotides 5/6 and 7/8. Oligonucleotides 9/10 and 11/12 were used to target the SAP7 ORF, and oligonucleotides 13/14 and 15/16 were used to target the SAP9 ORF. Oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table 2. Selectable marker sequences (Candida dubliniensis HIS1, Candida maltosa LEU2, and C. dubliniensis ARG4) were also amplified by PCR from plasmids pSN52, pSN40, and pSN69, respectively, as described previously (40). Fusion PCR products were generated by using oligonucleotides 1 and 4 to amplify BAR1, oligonucleotides 5 and 8 to amplify YPS7, oligonucleotides 9 and 12 to amplify SAP7, and oligonucleotides 13 and 16 to amplify SAP9. These PCR primers amplify the flanking sequences for each gene together with a marker PCR product (40). The first allele of each of these genes was replaced using the LEU2 marker in strain RBY1132. Second alleles were replaced using the HIS1 marker to generate a homozygous knockout of each of these genes. Correct integration of the PCR products was verified by PCR across the 5′ and 3′ disruption junctions, and loss of the ORF was confirmed using PCR primers internal to each ORF. The resulting (white-phase) strains were switched to the opaque phase by being passaged on SCD medium (18).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain(s) | Genotypea | Mating type | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBY1117 | leu2/leu2 his1/his1* | a/a | This study |

| RBY1118 | leu2/leu2 his1/his1* | a/a | This study |

| RBY1119 | leu2/leu2 his1/his1* | α/α | This study |

| RBY1120 | leu2/leu2 his1/his1* | α/α | This study |

| RBY1177 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/HIS1* | a/a | 3 |

| RBY1178 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/HIS1* | α/α | 3 |

| RBY1179 | arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG his1::hisG/HIS1* | a/a | 3 |

| RBY1180 | arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG his1::hisG/HIS1* | α/α | 3 |

| RBY1167 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG* arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG gpa2::HIS1/gpa2::LEU2 | a/a | 3 |

| RBY1197/8, RBY1218, RBY1220 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bar1::LEU2/bar1::HIS1* | a/a | This study |

| RBY1199, RBY1223, RBY1224 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG yps7::LEU2/yps7::HIS1* | a/a | This study |

| RBY1201, RBY1202 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG sap7::LEU2/sap7::HIS1* | a/a | This study |

| RBY1203, RBY1204 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG sap9::LEU2/sap9::HIS1* | a/a | This study |

| DSY18, DSY19 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bar1::LEU2/bar1::HIS1 gpa2/gpa2::SAT1* | a/a | This study |

| DSY20, DSY21 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bar1::LEU2/bar1::HIS1/BAR1 (BAR1 complemented)* | a/a | This study |

| DSY26, DSY27 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG yps7::LEU2/yps7::HIS1/YPS7 (YPS7 complemented)* | a/a | This study |

| DSY71, DSY72, DSY75 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG bar1::LEU2/bar1::HIS1* | α/α | This study |

| DSY73, DSY74 | leu2::hisG/leu2::hisG his1::hisG/his1::hisG arg4::hisG/arg4::hisG yps7::LEU2/yps7::HIS1* | α/α | This study |

| DSY121 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap4::hisG/sap4::hisG-URA3-hisG (derived from DSY436) | a/a | 45 |

| DSY124 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap3::hisG/sap3::hisG-URA3::hisG (derived from M22) | a/a | 20 |

| DSY130 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap5::hisG/sap5::hisG-URA3-hisG (derived from DSY452) | a/a | 45 |

| DSY131 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap6::hisG/sap6::hisG-URA3-hisG (derived from DSY346) | a/a | 45 |

| DSY142 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap1::hisG/sap1::hisG-URA3-hisG (derived from M6) | a/a | 20 |

| DSY144 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap2::hisG/sap2::hisG-URA3-hisG (derived from M13) | a/a | 20 |

| DSY145 | ura3::imm434/ura3::imm434 sap8::hisG/sap8::hisG-URA3-hisG | a/a | This study |

| 3294 | his1/his1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 | a/a | 32 |

| Ca29 | his1/sst2Δ::HIS1 his1/sst2Δ::HIS1 ura3/ura3 arg5,6/arg5,6 (derived from 3294) | a/a | 10 |

| PCa034 | his1/his ura3/rps1::Act-FAR1-URA3 arg5,6/arg5,6 (derived from 3294) | a/a | P. Côte et al., unpublished data |

| PCa202 | his1/his1 ura3/bar1Δ::URA3 sat/bar1Δ::SAT arg5,6/arg5,6 (derived from 3294) | a/a | This study |

Strains marked with an asterisk also contain the genotype URA3/Δura3::imm434 IRO1/Δiro1::imm434.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| 1 | TAACCAACATGTGTAGCAGC |

| 2 | cacggcgcgcctagcagcggCAGCTAAACTTGGCACAAGT |

| 3 | gtcagcggccgcatccctgcGTGTAACCTCTAACCCACAG |

| 4 | TGGCTGCAGTGAGCTCTCTC |

| 5 | AGTTTGAACCGTGCTTAGTC |

| 6 | cacggcgcgcctagcagcggGTGATTAATCTTATTGTTTTGGGG |

| 7 | gtcagcggccgcatccctgcGAAGTTGGAACAATGAAATTTCC |

| 8 | CGATATTATGAAAATGAAGATCATA |

| 9 | GTTCAGAAATAGTCCTAATGTC |

| 10 | cacggcgcgcctagcagcggACAGCAAGAGCTGTAGATGA |

| 11 | gtcagcggccgcatccctgcCATTTCTATTGCTCAAGCTGC |

| 12 | AGCATCAGAGAGAGACGGAG |

| 13 | CGGCAGTGATTCCCATACAA |

| 14 | cacggcgcgcctagcagcggCGCAACAGAATTGAGTCTCA |

| 15 | gtcagcggccgcatccctgcTCCTGTGTATGGGTTGTTGC |

| 16 | TACATATTGTGTCTCTTGGC |

| 17 | GCGGCCATGGGCCCGGTTAGATGTTCAACTCTTG |

| 18 | CAGGCGCGCTCGAGGGTATTGAACTCAACGGGCAT |

| 19 | GCGGCCATGGGCCCCCCATATAACAGATTTACCCG |

| 20 | CAGGCGCGCTCGAGCTAATAAGACGTATGTTGGGTG |

| 21 | CAGGATGACAACGGCAATAT |

| 22 | GGCAATAAACCTTCATAGGC |

| 23 | GTTGTACCTAGTTCAGTGAC |

| 24 | TGTTGATCAGGGTTTGCCAC |

Lowercase letters indicate exogenous sequences used for fusion PCR reactions, as described previously (40). Underlined sequences are ApaI and XhoI restriction sites.

Wild-type copies of the BAR1 and YPS7 genes were reintroduced into Δbar1/Δbar1 and Δyps7/Δyps7 strains, respectively. First, the wild-type genes were amplified by PCR, together with approximately 1 kb of upstream sequence. The BAR1 ORF was amplified using oligonucleotides 17 and 18, and the YPS7 ORF was amplified using oligonucleotides 19 and 20. Using the ApaI and XhoI restriction sites (underlined in Table 2), the PCR products were introduced into pSFS2A (42), which contains a dominant nourseothricin resistance marker. The resulting constructs were linearized with HpaI (BAR1 gene) and AflII (YPS7 gene) and integrated into the 5′-flanking regions of their respective genes. Correct integration of the BAR1 and YPS7 genes was confirmed by PCR across the boundaries of the inserted DNAs.

Several of the strains, including the SAP1-6 and SAP8 mutants, were derived from previously published a/α strains by selection for a or α derivatives on sorbose medium. SAP1-6 mutants were previously described (20, 45), while the mutant lacking SAP8 is unpublished and was a gift of Bernhard Hube (Robert Koch Institute, Germany).

Halo assays.

A lawn of C. albicans cells was formed by plating approximately 105 opaque cells (from an overnight culture grown in SCD medium) onto solid Spider medium. Alpha pheromone (10 mg/ml in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) or a 10% DMSO control was spotted (2 μl) onto the lawn of cells. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 3 days and then photographed.

Pheromone experiment.

Overnight cultures in SCD medium were inoculated with an opaque colony of a wild-type or Δbar1 mutant strain. The following morning, cells from each culture were washed with water and resuspended in Spider medium to a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml. Alpha pheromone was added at different concentrations (0.01, 0.1, and 1 μg/ml) to each culture, and the cultures were incubated at 25°C for 5 h. Cells were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan).

Quantitative mating assays.

Quantitative mating assays were performed by modification of a previous protocol (36). Auxotrophic mating strains were grown in the opaque phase at 23°C overnight in liquid SCD medium, and approximately 2 × 107 cells of each strain were mixed together. The mixed strains were deposited onto 0.8-μm filters by using a Millipore vacuum sampling manifold and then placed on the surfaces of Spider medium plates for 48 h at 23 to 25°C. Cells were collected and various dilutions plated onto dropout medium to select for mating conjugants and to monitor the parent-plus-conjugant population, as previously described (36). Cells were also taken from the mating mixes, and cell morphology and zygote formation were examined by microscopy using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu ORCA camera.

QPCR assays.

Cell cultures were prepared as previously described (3). Total RNA was prepared using a hot phenol procedure. To eliminate DNA contamination, RNAs were reextracted twice with hot phenol (pH 4.3; Fisher Scientific), followed by chloroform extraction and precipitation with ethanol. RNAs were reverse transcribed with Superscript (Stratagene), and cDNAs were amplified by quantitative PCR (QPCR) in an Applied Biosystems 7300 real-time PCR system. Signals from each experimental sample were normalized to signals from expression of the PAT1 gene, whose expression was not regulated by pheromone (3). Expression values were averaged for four independent experiments. Oligonucleotides for the SAP genes were selected from previously published work (7, 39, 51). Oligonucleotides 21 and 22 were used to amplify BAR1, and oligonucleotides 23 and 24 were used to amplify YPS7 (Table 2).

Barrier assays.

A thin lawn of a highly pheromone-responsive C. albicans strain, PCa034 (Table 1), was spread on a SCD plate. Streaks of the specific strains to be tested were made on this lawn adjacent to a point source of α-factor to establish whether the strain could provide a barrier to the diffusion of the pheromone (19). Opaque strains used for the barrier assays were verified for their opaque form microscopically. Plates were incubated at 24°C for 36 to 48 h, and pictures of the plates were scanned at 300 dpi, using an Epson Perfection 3710 photo scanner.

DNA microarray assays.

DNA microarray experiments were performed as previously described (3, 4, 10).

RESULTS

Identification of a putative mating pheromone barrier gene in C. albicans.

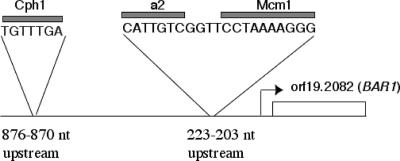

S. cerevisiae MATa cells down-regulate their response to alpha pheromone in part by the induced production of a secreted aspartyl protease, termed Bar1p, that degrades the pheromone (5). The inefficient cell cycle arrest generated in C. albicans by the analogous pheromone could therefore be due to a related proteolytic function. We identified ORFs in the C. albicans genome that encode an aspartyl protease-like domain similar to that encoded by the S. cerevisiae BAR1 gene. Eighteen known or putative ORFs with sequence similarity P values of 5.4e−4 and lower were found (Table 3). Among them, the secreted aspartyl (SAP) family genes were closely related to ScBAR1, with SAP9 having the greatest similarity. However, based on the S. cerevisiae model, we also predicted that the ScBAR1 ortholog would be a pheromone-induced MTLa-specific gene. In C. albicans, a-specific genes are regulated by the a2 transcription factor, which acts together with a cofactor protein, Mcm1 (49). Only one of the genes found to contain binding sites for a2/Mcm1 encodes an aspartyl-related protease; orf19.2082 thus represents a candidate BAR1 gene of C. albicans (also called SAP30, orf19.9629, or orf6.7473). We now present evidence that orf19.2082 is the C. albicans ortholog of ScBAR1, and we refer to this gene as BAR1 throughout this report. The promoter region of C. albicans BAR1 is shown in Fig. 1, which illustrates the position of the putative a2/Mcm1 binding site 203 to 223 nucleotides upstream of the ORF. The BAR1 gene was found to be expressed only in a cells by transcriptional profiling of pheromone-treated a and α cells of C. albicans (49). In the latter experiments, C. albicans BAR1 was one of only seven genes that were induced by pheromone treatment of a cells but not by pheromone treatment of α cells and was the only aspartyl protease in this group. We also confirmed that BAR1 is induced in pheromone-treated a cells by quantitative PCR (discussed below). A potential binding site for the C. albicans homolog of Ste12p (Cph1p) can also be found in the promoter region of BAR1 (Fig. 1). Ste12p mediates the transcriptional activation of pheromone-induced genes in S. cerevisiae, and Cph1p is similarly implicated in the pheromone response in C. albicans (6, 31). A potential consensus site for Ste12/Cph1p binding, TGTTTC/GA, has been identified (3, 11, 15), and a binding site is present in the promoter region of BAR1 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Homology between C. albicans aspartyl protease genes and S. cerevisiae BAR1a

| Gene | Unique name | Protein name or function | BLASTP E value compared to S. cerevisiae BAR1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAP9 | orf19.6928 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP9p | 4.5e−45 |

| SAP10 | orf19.3839 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP10p | 3.8e−36 |

| SAP6 | orf19.5542 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP6p | 8.8e−34 |

| SAP3 | orf19.6001 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP3p | 1.9e−33 |

| SAP2 | orf19.3708 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP2p | 1.9e−33 |

| SAP4 | orf19.5716 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP4p | 7.1e−33 |

| SAP1 | orf19.5714 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP1p | 1.6e−31 |

| SAP5 | orf19.5585 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP5p | 2e−30 |

| SAP8 | orf19.242 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP8p | 1.5e−23 |

| SAP7 | orf19.756 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase SAP7p | 6.4e−22 |

| SAP98 | orf19.852 | Predicted aspartic proteinase | 7.1e−19 |

| BAR1 | orf19.2082 | Secretory aspartyl proteinase | 3.7e−14 |

| APR1 | orf19.1891 | Vacuolar aspartic proteinase precursor | 7.1e−14 |

| IFF6 | orf19.4072 | Putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein of unknown function | 7e−5 |

| orf19.4906 | Hypothetical protein | 7.6e−5 | |

| YPS7 | orf19.6481 | Hypothetical protein | 1.1e−4 |

| orf19.3380 | Putative glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein | 5.2e−4 | |

| SAP99 | orf19.853 | Putative secreted aspartyl protease | 5.4e−4 |

Genes with sequence similarity P values of 5.4e−4 and lower are shown.

FIG. 1.

Schematic showing the promoter region of C. albicans orf19.2082 (C. albicans BAR1). The C. albicans BAR1 gene is expressed preferentially in a-type cells due to the presence of binding sites for a2 and Mcm1 proteins (49). In addition, there is a potential binding site for Cph1p (3), the C. albicans homolog of S. cerevisiae Ste12p, and this site may mediate induction of the C. albicans BAR1 gene in response to alpha pheromone.

In the following sections, we present several lines of evidence supporting the identification of orf19.2082 as the C. albicans ortholog of S. cerevisiae BAR1. In addition, we also tested the potential role of several other C. albicans aspartyl proteases as potential barriers to mating pheromone. In particular, we include an analysis of the role of the SAP family of genes in the response of C. albicans a cells to alpha pheromone. The results indicate that C. albicans BAR1 is a highly specific protease that acts to degrade the alpha mating pheromone during the mating of a cells.

Pheromone induction of BAR1 in C. albicans.

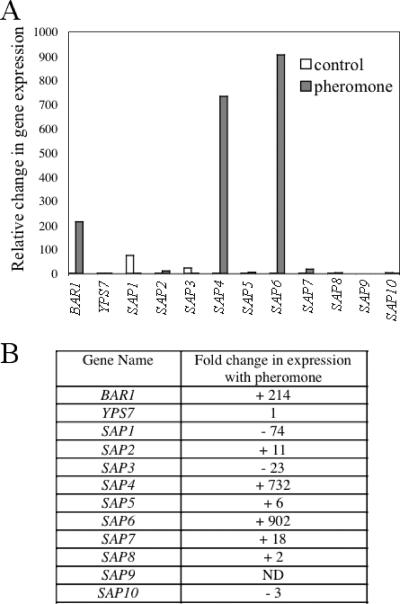

Transcriptional profiling studies of the response of C. albicans a cells to alpha pheromone revealed that under nutrient-limiting conditions, 144 genes were up-regulated by pheromone and 66 genes were down-regulated (expression change of >3-fold) (3). These experiments were performed in nutrient-deficient Spider medium, as opaque cells responded robustly to pheromone under these conditions (as measured by the number of genes induced, their induction ratios, and the fraction of cells exhibiting morphological responses) (3). Included among the set of pheromone-regulated genes were a number of protease genes, including several that were highly up-regulated by pheromone, e.g., SAP4, SAP5, and SAP6, and several that were repressed by pheromone, e.g., SAP1 and SAP3 (3). In the same studies, the BAR1 gene was one of the most induced genes, with expression increased >100-fold 4 h after exposure to pheromone. To analyze more accurately the response of C. albicans BAR1 and the SAP family of genes to pheromone, we carried out QPCR to determine the changes in expression of these genes in cells responding to pheromone. These experiments were important to confirm the pattern of expression of the protease genes, since many of these genes are highly homologous and it is possible that the microarray experiments did not distinguish between closely related genes. For the PCR experiments, oligonucleotides were chosen to specifically amplify each target gene, as previously described (7, 39, 51).

QPCR was performed on opaque a cells grown in Spider medium and treated with alpha pheromone (or a DMSO control) for 4 h. Again, Spider medium was used because this medium produced an efficient response of opaque cells to pheromone, both morphologically and in transcriptional profiling experiments (3). Cells were harvested and cDNAs prepared from the cells as a template for QPCR (see Materials and Methods). Figure 2 shows the relative expression levels of several C. albicans protease genes in response to alpha pheromone. For this study, we compared expression levels of BAR1, the SAP genes (SAP1-10), and YPS7 (orf19.6481). The last gene is a gene of unknown function but is also predicted to encode an aspartyl protease whose S. cerevisiae homolog is encoded by YPS7 (Table 3; see also www.candidagenome.org). Several protease genes were highly regulated by alpha pheromone, as predicted from the microarray analyses. In particular, the BAR1, SAP4, and SAP6 genes were highly induced in opaque a cells responding to alpha pheromone, with each gene induced >200-fold. Several other aspartyl protease genes were induced more modestly by alpha pheromone, with SAP2, SAP5, and SAP7 induced 11-, 6-, and 18-fold, respectively. In contrast, SAP1 and SAP3 were negatively regulated by alpha pheromone (repressed 74- and 23-fold, respectively), confirming the down-regulation of these genes observed previously in microarray and Northern analyses (3, 29).

FIG. 2.

Pheromone responses of BAR1, YPS7, and the SAP family of genes. The relative expression levels of aspartyl protease genes in C. albicans opaque a cells exposed to alpha pheromone were analyzed by QPCR. Cells were treated with alpha pheromone (or a DMSO control) for 4 h, and cDNAs were prepared from the harvested cells (see Materials and Methods). QPCR was performed on 12 genes, including C. albicans BAR1, YPS7, and SAP1 to SAP10. The results shown are averages for four independent experiments. Expression of SAP9 was not detected (ND).

Deletion of the BAR1 gene enhances alpha pheromone sensitivity.

In S. cerevisiae, deletion of the BAR1 gene results in an increased sensitivity of a-type cells to the alpha mating pheromone. This can be demonstrated by spotting alpha pheromone onto a nascent lawn of MATa cells: once the lawn has grown to maturity, a halo is observed around the spot of the pheromone due to efficient cell cycle arrest of neighboring cells. The halo assay provides a simple semiquantitative measure of pheromone activity, as the size of the halo is proportional to both the amount of pheromone present and the strength of the pheromone response in the responding mating partner (35). Thus, in S. cerevisiae, deletion of the BAR1 gene results in increased halo formation due to the increase in effective pheromone concentration, as no pheromone is degraded by the protease.

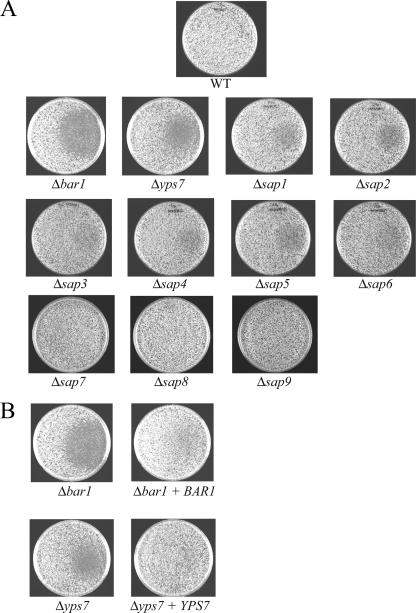

To test if C. albicans aspartyl protease genes modulate the sensitivity to alpha pheromone, BAR1, YPS7, and SAP1-9 homozygous deletion mutants were constructed in MTLa cells. A lawn of opaque cells of each mutant strain was plated on Spider medium plates, pheromone (or a control) was spotted onto the lawn, and the cells were allowed to grow to maturity. Again, Spider medium was used for this assay to ensure a robust response of opaque a cells to alpha pheromone (3). Figure 3 shows the results of halo assays carried out with strains in which BAR1, YPS7, or a SAP gene (SAP1-9) was deleted compared to the result with a wild-type strain. The wild-type a strain showed no clear halo formation in response to alpha pheromone, confirming that C. albicans cells do not naturally undergo extended growth arrest in response to mating pheromone (3, 10, 41). In contrast, a mutant lacking the BAR1 gene produced a large halo around the spot of the pheromone, indicating that neighboring a cells had responded to pheromone by arresting their growth (Fig. 3A). The SAP1-9 mutants, like the wild type, failed to produce a significant halo around the pheromone spot. The Δyps7 strain, however, did produce a detectable halo, although the halo was smaller than that observed for Δbar1 strains. The phenotype of multiple Δyps7 mutants was variable, as two of four independent Δyps7 mutants showed the halo phenotype displayed in Fig. 3, while two mutants showed no halo formation (i.e., appeared indistinguishable from the wild type). We confirmed that the halo phenotypes of both BAR1 and YPS7 mutants were due to the loss of the targeted gene by reintroduction of one copy of the wild-type gene to the mutant locus (Fig. 3B). These experiments are consistent with C. albicans BAR1 encoding a protein with alpha pheromone-degrading activity and also indicate that YPS7, although not a pheromone-responsive gene, can also act to degrade alpha pheromone.

FIG. 3.

Halo assay with C. albicans aspartyl protease mutant strains. Halo assays were performed by plating a lawn of opaque a cells on Spider plates and spotting alpha pheromone (2 μg) or a control (DMSO) onto each plate. Pheromone was spotted on the center right of each plate, and the DMSO control was spotted on the center left of the plate. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 3 days for the lawn of cells to grow up and then were photographed. (A) C. albicans opaque cells from wild-type (RBY1117), Δbar1 (RBY1197), Δyps7 (RBY1200), Δsap1 (DSY142), Δsap2 (DSY144), Δsap3 (DSY124), Δsap4 (DSY169), Δsap5 (DSY130), Δsap6 (DSY131), Δsap7 (RBY1201), Δsap8 (DSY145), and Δsap9 (RBY1203) strains were plated on Spider medium and tested for their response to alpha pheromone. (B) Halo activities of opaque cells from mutant and reconstituted strains were compared to confirm BAR1 and YPS7 function. One copy of the C. albicans BAR1 gene was integrated into a Δbar1 strain for complementation (DSY20), and similarly, one copy of the YPS7 gene was integrated into a Δyps7 mutant strain for complementation (DSY26).

Deletion of the BAR1 gene leads to a defect in mating in C. albicans cells.

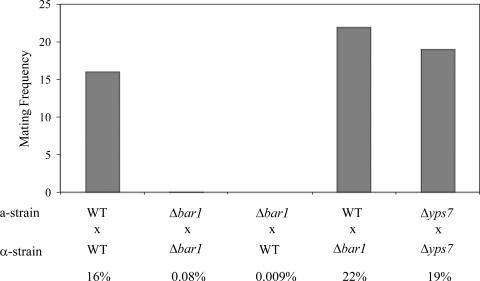

To examine if the loss of C. albicans BAR1 or YPS7 leads to a change in mating efficiency, deletion strains lacking these genes were tested in quantitative mating experiments. Opaque a and α strains harboring different auxotrophic markers were coincubated on Spider medium for 48 h and then plated on tester plates to determine the frequency of formation of prototrophic mating products (see Materials and Methods for details). Mating between wild-type strains occurred with an average mating efficiency of 15% in this assay (Fig. 4). Mating of Δyps7 strains occurred at a frequency similar to that of wild-type strains, with 19% of a and α cells forming mating products. Significantly, mating of Δbar1 a and α strains showed a greatly reduced mating efficiency, with an average mating frequency of <0.1%. To determine if the mating defect was specific to a or α cells, wild-type strains were crossed with Δbar1 mating partners. Mating of Δbar1 a strains with wild-type α strains resulted in extremely low mating efficiencies (0.01%), while Δbar1 α strains mated with wild-type a strains at normal efficiencies (22%) (Fig. 4). These mating experiments revealed that Δbar1 strains exhibit an a-specific defect in mating, with mating reduced >100-fold relative to that of wild-type a strains. Experiments with S. cerevisiae Δbar1 mutants also revealed a mating defect in a strains, although this defect was more modest (4- to 33-fold) than that observed here with C. albicans Δbar1 mutants (5, 16).

FIG. 4.

Quantitative mating of wild-type (WT), Δbar1, and Δyps7 strains of C. albicans. Mating between auxotrophic opaque strains was carried out, and the efficiency of mating was determined by analyzing the frequency of formation of prototrophic mating products. Mating was carried out by mixing of opaque a and α strains and incubation on Spider medium for 48 h prior to plating on selective medium (see Materials and Methods). The wild-type strains used were RBY1117, RBY1118, RBY1119, RBY1120, RBY1177, RBY1178, RBY11179, and RBY1180; the C. albicans Δbar1 strains used were RBY1197, RBY1198, DSY71, DSY72, and DSY75; and the Δyps7 strains used were RBY1199, RBY1200, DSY73, and DSY74. Strain genotypes are listed in Table 1.

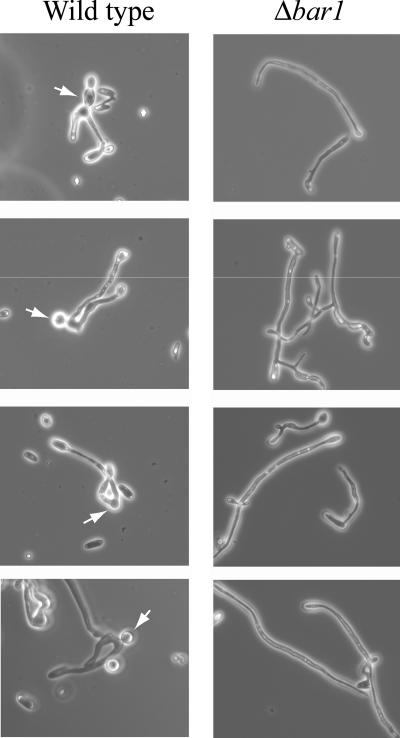

To further characterize the defect in mating, we analyzed cells taken from mixes of mating a and α cells after 48 h of incubation. Wild-type strains contained many mating zygotes, as expected from the relatively efficient mating between a and α strains (Fig. 5). In contrast, very few, if any, zygotes were visible for matings between Δbar1 strains, even though the cells exhibited long mating projections characteristic of cells responding to mating pheromones (Fig. 5). These experiments demonstrate that the block to mating occurs early in Δbar1 mutants, with cells unable to undergo fusion with a mating partner.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of cells from mating mixes of C. albicans wild-type and Δbar1 strains. Opaque a and α cells were mixed and incubated on Spider medium for 48 h, as described in the legend to Fig. 4. Cells were then removed from the mass mating mix and analyzed by microscopy. Mating between wild-type a and α strains led to the formation of many zygotes (products of fusion between opaque a and α cells). Zygotes were observed both with daughter cell buds (panels 1, 2, and 4) and with emerging daughter cell buds (panel 3), as shown by arrows. In contrast, zygotes were rarely observed in mixes of Δbar1 a and α cells, although these cells still exhibited a robust mating response, as evidenced by the presence of long mating projections.

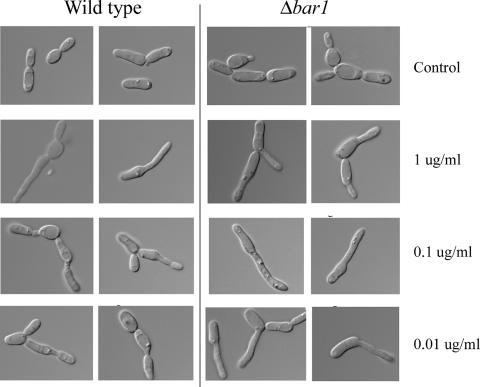

Deletion of BAR1 sensitizes opaque cells to alpha pheromone.

The morphologies of opaque wild-type and Δbar1 strains were compared in the presence of alpha pheromone. Alpha pheromone induces the formation of characteristic mating projections in C. albicans, and these can be many times the length of the original mother cell (4, 28, 29, 41). Wild-type and Δbar1 opaque a cells were treated with various doses of alpha pheromone (1, 0.1, and 0.01 μg/ml), and their cellular morphology was determined after 5 h of incubation. At a high pheromone concentration (1 μg/ml), both wild-type and Δbar1 mutant cells showed a marked response to pheromone, as observed by the formation of long mating projections (Fig. 6). The Δbar1 strain also exhibited long mating projections at low concentrations of pheromone, and even at 0.01 μg/ml pheromone, it elicited mating projections that resembled those seen at 1 μg/ml (Fig. 6). In contrast, wild-type strains did not produce any significant mating projections at low concentrations of pheromone (0.1 and 0.01 μg/ml). Instead, these cells appeared to generate small mating projections that then resumed a normal budding morphology (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Morphological response of C. albicans Δbar1 strains to low concentrations of alpha pheromone. Wild-type and Δbar1 strains were incubated with various concentrations of alpha pheromone in Spider medium for 5 h and then analyzed by microscopy. Wild-type cells (RBY1117) responded strongly to high concentrations of alpha pheromone (1 μg/ml) but failed to exhibit long mating projections at lower concentrations of pheromone. In contrast, Δbar1 cells (RBY1197) showed a strong morphological response to pheromone even at concentrations as low as 0.01 μg/ml.

These results are consistent with the predicted function of the BAR1 gene—expression of the Bar1p protease leads to a breakdown of alpha pheromone, and thus, higher concentrations of pheromone are necessary to overcome proteolytic processing of the pheromone. In the absence of the Bar1p protease, alpha pheromone is not degraded, and thus, smaller amounts of pheromone can efficiently induce a mating response.

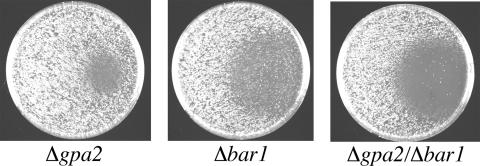

Additive effect of mutations in BAR1 and GPA2 on pheromone response in C. albicans.

In C. albicans, Gpr1 is a G protein-coupled receptor that acts together with Gpa2, encoding a Gα subunit, in signaling environmental cues to the cell (34, 37, 44). Previously, we showed that nutritional signals play an important part in the efficiency of the response of C. albicans to pheromone and identified Gpa2 as a component of the nutrient-sensing pathway (3). C. albicans a cells lacking Gpa2 showed an enhanced response to alpha pheromone and resulted in Δgpa2 mutants forming a distinct zone of arrested growth in the halo assay (Fig. 7). The halo formed by Δgpa2 mutants was smaller than that formed by Δbar1 mutants (Fig. 7). To see if mutations in GPA2 and BAR1 are additive, we generated double mutants in which both genes were deleted from a-type mating cells and tested their response to alpha pheromone in the halo assay. While both Δgpa2 and Δbar1 strains produced halos, the double mutant strain produced a larger halo than either single mutant alone (Fig. 7). In addition, the halo formed by the Δgpa2 Δbar1 strain appeared less cloudy than that in either the Δgpa2 or Δbar1 single mutant, indicating more efficient cell cycle arrest. This result is consistent with Bar1p and Gpa2p being involved in different steps in the pheromone response; Bar1p is involved in degradation of the pheromone, while Gpa2p is involved in a nutrient signaling pathway that modulates the response to mating pheromone. The data also show that modulation of both pathways is necessary for efficient growth arrest in response to pheromone in C. albicans.

FIG. 7.

Halo formation in C. albicans Δgpa2, Δbar1, and Δgpa2 Δbar1 strains. Both Δgpa2 (3) and Δbar1 (this work) strains exhibit areas of growth arrest in response to alpha pheromone in halo assays. To see if this phenotype is additive, a double mutant strain lacking both GPA2 and BAR1 was constructed and tested in the halo assay. Pheromone was spotted on the center right of each plate, and a DMSO control was spotted on the center left of the plate. The Δgpa2 strain (RBY1166) and the Δbar1 strain (RBY1197) produced cloudy halos, but the double mutant Δgpa2 Δbar1 strain (DSY18) produced a large halo that was relatively clear of background cell growth. Small colonies observed within the halo are due to the presence of a few (unresponsive) white cells within the largely opaque population.

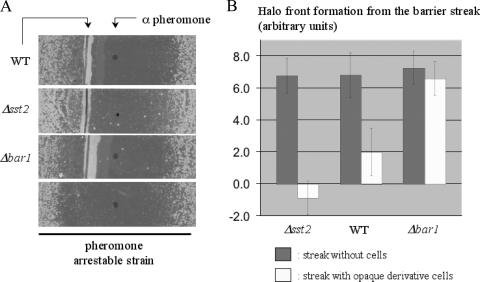

Demonstration of barrier activity by Bar1p.

We used a strategy similar to the S. cerevisiae barrier assay to confirm the existence of barrier activity in C. albicans (19). C. albicans opaque cells in which Far1p was overexpressed were used for these experiments, as these cells efficiently arrest their growth in response to α-factor (P. Côte et al., unpublished data). Briefly, a lawn of Far1-overexpressing opaque cells was used to detect whether a test strain could block the diffusion of α-factor. If the tested strain can secrete, either constitutively or in response to pheromone, a protein with pheromone-degrading activity, then it will generate a barrier to the diffusion of a source of alpha pheromone placed next to it, and the lawn of sensitive cells on the other side of this barrier will be able to grow. We tested barrier activity in a wild-type strain (3294) and in the super-pheromone-sensitive Δsst2 strain (Ca29) (10). As shown in Fig. 8, we observed a block in halo front formation beyond the streak of opaque wild-type cells. For the Δsst2 strain and its enhanced pheromone response, we observed growth of the lawn even on the pheromone spot side of the barrier, consistent with a zone of pheromone inactivation extending on both sides of the test streak (Fig. 8). Significantly, the deletion of BAR1 in strain PCa202 completely abolished the barrier activity observed in the parental wild-type strain (Fig. 8). White-phase cells of each of the tested strains did not produce observable barrier activity (data not shown). This experiment demonstrates that C. albicans cells secrete a protein with barrier activity to alpha pheromone and that this protein is encoded by BAR1.

FIG. 8.

Demonstration of barrier activity encoded by C. albicans BAR1. A barrier assay was set up to test if BAR1 encodes a protein with barrier activity in opaque cells of C. albicans. (A) A barrier assay was made by using a lawn of hypersensitive cells (Far1p-overexpressing cells; PCa034) to assay the mating pheromone migration front, with a streak of tester strain in front of the pheromone spot to verify the barrier activity. The opaque form of wild-type strain 3294 significantly reduced the distance of the front of the halo when placed adjacent to the pheromone spot. In contrast, a streak of opaque Δbar1 cells (PCa202 strain) did not affect the halo front, which extended the same distance as that in the no-cell control (PCa034 only). (B) Distance from halo front to cell streak (in arbitrary units, with barrier streak set at 0). With wild-type cells as a barrier, the halo front came adjacent to the streak, whereas with Δsst2 pheromone-sensitive cells (Ca29), colony growth occurred on the pheromone spot side of the barrier, consistent with a diffusion zone of α-factor destruction on both sides of the test streak. As presented in panel A, a streak of Δbar1 cells (PCa202) had no effect on the location of the halo front, indicative of an absence of barrier activity in these cells.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a gene encoding a protein with barrier activity to mating pheromone in C. albicans (orf19.2082) and now designate this gene BAR1, the ortholog of S. cerevisiae BAR1. Characterization of the C. albicans BAR1 gene demonstrated that it has several properties similar to those of S. cerevisiae BAR1, including the following. (i) BAR1 is expressed only in a-type mating cells of C. albicans (49). (ii) The BAR1 gene is induced by alpha pheromone (3, 49; this study). (iii) Strains lacking the BAR1 gene are hypersensitive to pheromone and generate distinct areas of arrested cell growth in halo assays. (iv) MTLa Δbar1 strains exhibit a significant defect in mating with wild-type α strains. (v) Bar1p is responsible for the barrier activity that limits alpha pheromone diffusion. S. cerevisiae Δbar1 strains have been extremely useful to the community, and together with S. cerevisiae alpha pheromone, they have been used extensively for efficient synchronization of the cell cycle. It is envisaged that Δbar1 strains will prove similarly beneficial for cell cycle studies with C. albicans.

Comparisons between mating in S. cerevisiae and that in C. albicans have been stimulating, as these organisms share many features in the mating pathway, but at the same time, studies have revealed important differences in the regulation of their mating behavior. For example, whereas both fungi use a conserved MAP kinase cascade to transduce the pheromone signal into a transcriptional cascade in the nucleus (6, 31), mating in C. albicans is also regulated by nutritional signals, whereas mating in S. cerevisiae occurs efficiently without specific nutrient requirements (3, 27). Furthermore, while both organisms undergo mating between a and α cell types, the transcriptional regulation of mating type is achieved by different mechanisms in these two fungi (49). Other differences between the mating processes in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans may be quantitative rather than qualitative. For example, the transcriptional response to pheromone in C. albicans appears to increase gradually over several hours, while that in S. cerevisiae reaches maximal levels within several minutes of pheromone exposure (1, 25, 43).

The BAR1 gene may play a role in some of the observed differences in pheromone responses between fungal species. S. cerevisiae BAR1+ strains undergo efficient cell cycle arrest in response to pheromone, whereas C. albicans BAR1+ strains do not (3, 10, 41). These differences may be due in part to quantitative differences in the levels of BAR1 activity between these two organisms. However, other mechanisms also influence the response of a cells to pheromone, as even for C. albicans Δbar1 mutants the halos appeared cloudy, whereas for S. cerevisiae strains, halos appear clear due to efficient cell cycle arrest (35). Similar results were seen with hypersensitive SST2 mutants of C. albicans; in this case, Δsst2 strains formed halos, but they were cloudy due to some cells failing to respond efficiently to pheromone (10). Clearer halos are formed by strains overexpressing the C. albicans ortholog of the S. cerevisiae cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Far1p (Côte et al., unpublished data) or in C. albicans strains lacking both Bar1p and the Gα protein Gpa2p (3). Gpa2p functions in a nutrient-sensing pathway to regulate the response to pheromone in C. albicans, and Δgpa2 mutants respond more strongly to pheromone both transcriptionally and morphologically. Since the nutrient-sensing pathway does not regulate the pheromone response in S. cerevisiae, this may be one reason why it is easier to obtain pheromone-induced growth arrest in S. cerevisiae than in C. albicans.

Deletion of the BAR1 gene led to a large, >100-fold decrease in the mating efficiency of C. albicans a cells. In S. cerevisiae, Δbar1 mutants also exhibit a decrease in mating efficiency, although the decrease is more modest (varying from 4-fold to 33-fold) (5, 16). The decrease in mating efficiency is thought to be a direct result of overstimulation of the mating pathway. Thus, shutting off the response to pheromone not only is required for cells that have failed to find a mating partner but is also a necessary step in the normal mating process. Similar defects in mating were observed in Δsst2 mutants of C. albicans, as these also lead to overstimulation of cells responding to pheromone (10).

In addition to the identification of BAR1 in C. albicans, we noted that mutations in a second gene, YPS7, resulted in increased sensitivity of a cells to pheromone. The YPS7 gene is predicted to encode an aspartyl protease, although the phenotypes of different Δyps7 strains varied. For some Δyps7 mutants, no halo was formed, while others produced a distinct halo, albeit smaller than the halo formed by Δbar1 strains. For Δyps7 mutants that displayed a halo phenotype, the phenotype was suppressed by reintroduction of one copy of the YPS7 gene, confirming that the phenotype was due to the loss of YPS7 function. Deletion of the YPS7 gene did not affect mating frequencies in C. albicans. At present, the reason for the variable phenotype of Δyps7 strains is not known. One possibility is that the expression of other pheromone-degrading proteases is up-regulated in some mutants and thus can occasionally compensate for the loss of YPS7. The epigenetic regulation of proteases in C. albicans has not been demonstrated, but it is not surprising to find that this fungal pathogen has mechanisms by which the expression of some aspartyl proteases can compensate for that of another.

Despite the identification of alpha pheromone processing activities in C. albicans BAR1 and YPS7, the majority of aspartyl protease genes tested (SAP1-9) did not influence the response of a cells to pheromone. These results confirm that the degradation of alpha pheromone requires targeting of the pheromone by an aspartyl protease with appropriate specificity. It also raises the question of the function of the other SAP genes in mating in C. albicans. Five members of the SAP family of genes are induced by pheromone (SAP2, SAP4, SAP5, SAP6, and SAP7), while two SAP genes are repressed by pheromone (SAP1 and SAP3). In addition, four of the SAP genes are also regulated by white-opaque switching: SAP1, SAP2, SAP3, and SAP4 are upregulated in the opaque (mating-competent) state (26, 38, 48, 50). There appear to be two main possibilities for the role of the SAP genes in mating, as follows: (i) they play an intrinsic role in mating, although the function of these genes in mating is not yet understood; or (ii) their function is related to where mating occurs in vivo, and they act to promote mating in this in vivo niche. Future experiments will be directed toward determining the role of the SAP genes in mating and testing if epigenetic regulation of these genes occurs in C. albicans.

In summary, we have shown that C. albicans MTLa cells possess a barrier activity in response to alpha mating pheromone. We have identified the ortholog of S. cerevisiae BAR1 in C. albicans and characterized the activity of the barrier protease. The identification of C. albicans BAR1 provides a further similarity between the mating processes of S. cerevisiae and C. albicans and should assist in studies requiring synchronization of the cell cycle. The regulation of SAP genes by white-opaque switching and alpha pheromone suggests that other aspartyl proteases also play a significant, but as yet undetermined, role in C. albicans mating.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Annie Tsong, Brian Tuch, and Alexander Johnson for the original observation that orf19.2082 (C. albicans BAR1) is a potential ScBAR1 homolog due to its expression in a-type mating cells of C. albicans. We are also grateful to Bernhard Hube and Dominique Sanglard for the gift of SAP mutant strains.

This work was supported in part by grants to R.J.B. from the Rhode Island Foundation and by a Richard B. Salomon Faculty Research Award. Work in the Whiteway laboratory was supported by CIHR grant MOP-42516.

This is NRCC publication 47559.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 April 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett, R. J., and A. D. Johnson. 2003. Completion of a parasexual cycle in Candida albicans by induced chromosome loss in tetraploid strains. EMBO J. 22:2505-2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett, R. J., and A. D. Johnson. 2005. Mating in Candida albicans and the search for a sexual cycle. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:233-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett, R. J., and A. D. Johnson. 2006. The role of nutrient regulation and the Gpa2 protein in the mating pheromone response of C. albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 62:100-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, R. J., M. A. Uhl, M. G. Miller, and A. D. Johnson. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Candida albicans mating pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:8189-8201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, R. K., and C. A. Otte. 1982. Isolation and genetic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants supersensitive to G1 arrest by a factor and alpha factor pheromones. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, J., J. Chen, S. Lane, and H. Liu. 2002. A conserved mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for mating in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1335-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Copping, V. M., C. J. Barelle, B. Hube, N. A. Gow, A. J. Brown, and F. C. Odds. 2005. Exposure of Candida albicans to antifungal agents affects expression of SAP2 and SAP9 secreted proteinase genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55:645-654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels, K. J., T. Srikantha, S. R. Lockhart, C. Pujol, and D. R. Soll. 2006. Opaque cells signal white cells to form biofilms in Candida albicans. EMBO J. 25:2240-2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dignard, D., A. L. El-Naggar, M. E. Logue, G. Butler, and M. Whiteway. 2007. Identification and characterization of MFA1, the gene encoding Candida albicans a-factor pheromone. Eukaryot. Cell 6:487-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dignard, D., and M. Whiteway. 2006. SST2, a regulator of G-protein signaling for the Candida albicans mating response pathway. Eukaryot. Cell 5:192-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolan, J. W., C. Kirkman, and S. Fields. 1989. The yeast STE12 protein binds to the DNA sequence mediating pheromone induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:5703-5707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumitru, R., D. H. Navarathna, C. P. Semighini, C. G. Elowsky, R. V. Dumitru, D. Dignard, M. Whiteway, A. L. Atkin, and K. W. Nickerson. 2007. In vivo and in vitro anaerobic mating in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 6:465-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edmond, M. B., S. E. Wallace, D. K. McClish, M. A. Pfaller, R. N. Jones, and R. P. Wenzel. 1999. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in United States hospitals: a three-year analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elion, E. A. 2000. Pheromone response, mating and cell biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Errede, B., and G. Ammerer. 1989. STE12, a protein involved in cell-type-specific transcription and signal transduction in yeast, is part of protein-DNA complexes. Genes Dev. 3:1349-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giot, L., C. DeMattei, and J. B. Konopka. 1999. Combining mutations in the incoming and outgoing pheromone signal pathways causes a synergistic mating defect in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15:765-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gow, N. A. 2002. Candida albicans switches mates. Mol. Cell 10:217-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guthrie, C., and G. R. Fink. 1991. Guide to yeast genetics and molecular biology. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 19.Hicks, J. B., and I. Herskowitz. 1976. Evidence for a new diffusible element of mating pheromones in yeast. Nature 260:246-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hube, B., D. Sanglard, F. C. Odds, D. Hess, M. Monod, W. Schafer, A. J. Brown, and N. A. Gow. 1997. Disruption of each of the secreted aspartyl proteinase genes SAP1, SAP2, and SAP3 of Candida albicans attenuates virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:3529-3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hull, C. M., R. M. Raisner, and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science 289:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janbon, G., F. Sherman, and E. Rustchenko. 1998. Monosomy of a specific chromosome determines l-sorbose utilization: a novel regulatory mechanism in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:5150-5155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, A. 2003. The biology of mating in Candida albicans. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:106-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lachke, S. A., S. R. Lockhart, K. J. Daniels, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Skin facilitates Candida albicans mating. Infect. Immun. 71:4970-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahav, R., A. Gammie, S. Tavazoie, and M. D. Rose. 2007. Role of transcription factor Kar4 in regulating downstream events in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae pheromone response pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:818-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lan, C. Y., G. Newport, L. A. Murillo, T. Jones, S. Scherer, R. W. Davis, and N. Agabian. 2002. Metabolic specialization associated with phenotypic switching in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14907-14912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lengeler, K. B., R. C. Davidson, C. D'Souza, T. Harashima, W. C. Shen, P. Wang, X. Pan, M. Waugh, and J. Heitman. 2000. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:746-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lockhart, S. R., K. J. Daniels, R. Zhao, D. Wessels, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Cell biology of mating in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2:49-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lockhart, S. R., R. Zhao, K. J. Daniels, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Alpha-pheromone-induced “shmooing” and gene regulation require white-opaque switching during Candida albicans mating. Eukaryot. Cell 2:847-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKay, V. L., S. K. Welch, M. Y. Insley, T. R. Manney, J. Holly, G. C. Saari, and M. L. Parker. 1988. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae BAR1 gene encodes an exported protein with homology to pepsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:55-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magee, B. B., M. Legrand, A. M. Alarco, M. Raymond, and P. T. Magee. 2002. Many of the genes required for mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are also required for mating in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1345-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magee, B. B., and P. T. Magee. 2000. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLalpha strains. Science 289:310-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magee, P. T., and B. B. Magee. 2004. Through a glass opaquely: the biological significance of mating in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:661-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maidan, M. M., L. De Rop, J. Serneels, S. Exler, S. Rupp, H. Tournu, J. M. Thevelein, and P. Van Dijck. 2005. The G protein-coupled receptor Gpr1 and the Galpha protein Gpa2 act through the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway to induce morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:1971-1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manney, T. R. 1983. Expression of the BAR1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: induction by the alpha mating pheromone of an activity associated with a secreted protein. J. Bacteriol. 155:291-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller, M. G., and A. D. Johnson. 2002. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell 110:293-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miwa, T., Y. Takagi, M. Shinozaki, C. W. Yun, W. A. Schell, J. R. Perfect, H. Kumagai, and H. Tamaki. 2004. Gpr1, a putative G-protein-coupled receptor, regulates morphogenesis and hypha formation in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:919-931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrow, B., T. Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 1992. Transcription of the gene for a pepsinogen, PEP1, is regulated by white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2997-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naglik, J. R., C. A. Rodgers, P. J. Shirlaw, J. L. Dobbie, L. L. Fernandes-Naglik, D. Greenspan, N. Agabian, and S. J. Challacombe. 2003. Differential expression of Candida albicans secreted aspartyl proteinase and phospholipase B genes in humans correlates with active oral and vaginal infections. J. Infect. Dis. 188:469-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noble, S. M., and A. D. Johnson. 2005. Strains and strategies for large-scale gene deletion studies of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 4:298-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panwar, S. L., M. Legrand, D. Dignard, M. Whiteway, and P. T. Magee. 2003. MFα1, the gene encoding the α mating pheromone of Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1350-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reuss, O., A. Vik, R. Kolter, and J. Morschhauser. 2004. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts, C. J., B. Nelson, M. J. Marton, R. Stoughton, M. R. Meyer, H. A. Bennett, Y. D. He, H. Dai, W. L. Walker, T. R. Hughes, M. Tyers, C. Boone, and S. H. Friend. 2000. Signaling and circuitry of multiple MAPK pathways revealed by a matrix of global gene expression profiles. Science 287:873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez-Martinez, C., and J. Perez-Martin. 2002. Gpa2, a G-protein alpha subunit required for hyphal development in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 1:865-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanglard, D., B. Hube, M. Monod, F. C. Odds, and N. A. Gow. 1997. A triple deletion of the secreted aspartyl proteinase genes SAP4, SAP5, and SAP6 of Candida albicans causes attenuated virulence. Infect. Immun. 65:3539-3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soll, D. R. 2004. Mating-type locus homozygosis, phenotypic switching and mating: a unique sequence of dependencies in Candida albicans. Bioessays 26:10-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sprague, G. F., Jr., and I. Herskowitz. 1981. Control of yeast cell type by the mating type locus. I. Identification and control of expression of the a-specific gene BAR1. J. Mol. Biol. 153:305-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsong, A. E., M. G. Miller, R. M. Raisner, and A. D. Johnson. 2003. Evolution of a combinatorial transcriptional circuit: a case study in yeasts. Cell 115:389-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsong, A. E., B. B. Tuch, H. Li, and A. D. Johnson. 2006. Evolution of alternative transcriptional circuits with identical logic. Nature 443:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White, T. C., S. H. Miyasaki, and N. Agabian. 1993. Three distinct secreted aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 175:6126-6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu, Z., Y. B. Cao, J. D. Zhang, Y. Y. Cao, P. H. Gao, D. J. Wang, X. P. Fu, K. Ying, W. S. Chen, and Y. Y. Jiang. 2005. cDNA array analysis of the differential expression change in virulence-related genes during the development of resistance in Candida albicans. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 37:463-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao, R., K. J. Daniels, S. R. Lockhart, K. M. Yeater, L. L. Hoyer, and D. R. Soll. 2005. Unique aspects of gene expression during Candida albicans mating and possible G1 dependency. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1175-1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]