Abstract

Amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition is a major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease. Gleevec, a known tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been shown to lower Aβ secretion, and it is considered a potential basis for novel therapies for Alzheimer's disease. Here, we show that Gleevec decreases Aβ levels without the inhibition of Notch cleavage by a mechanism distinct from γ-secretase inhibition. Gleevec does not influence γ-secretase activity in vitro; however, treatment of cell lines leads to a dose-dependent increase in the amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD), whereas secreted Aβ is decreased. This effect is observed even in presence of a potent γ-secretase inhibitor, suggesting that Gleevec does not activate AICD generation but instead may slow down AICD turnover. Concomitant with the increase in AICD, Gleevec leads to elevated mRNA and protein levels of the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin, a potential target gene of AICD-regulated transcription. Thus, the Gleevec mediated-increase in neprilysin expression may involve enhanced AICD signaling. The finding that Gleevec elevates neprilysin levels suggests that its Aβ-lowering effect may be caused by increased Aβ-degradation.

INTRODUCTION

The main neuropathological features of Alzheimer's disease (AD) are the extracellular deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides and the formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, accompanied by neuron loss and dementia (Selkoe, 2001). Aβ is generated by sequential proteolytic cleavages of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase (BACE) and γ-secretase. The γ-secretase cleavage occurs within the membrane, releasing the APP intracellular domain (AICD) into the cytosol. AICD, together with its binding partners Fe65 and Tip60, is considered to be involved in transcriptional regulation (Cao and Sudhof, 2001). Putative target genes of AICD signaling have been suggested (Baek et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003; von Rotz et al., 2004; Pardossi-Piquard et al., 2005; Ryan and Pimplikar, 2005; Muller et al., 2007), although results for some of these genes are controversial (Hass and Yankner, 2005; Hebert et al., 2006; Chen and Selkoe, 2007; Pardossi-Piquard et al., 2007). One potential AICD target gene is the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin (Pardossi-Piquard et al., 2005, 2006), a metalloprotease that is one of the main Aβ-degrading enzymes in the brain (Carson and Turner, 2002).

γ-Secretase is a multiprotein complex, processing several type I integral membrane proteins, including APP and the Notch receptor (Kopan and Ilagan, 2004). Therapeutic strategies aimed at lowering Aβ include the development of selective γ-secretase inhibitors (Evin et al., 2006). However, long-term treatment with γ-secretase inhibitors has shown severe side effects in preclinical animal studies due to inhibition of Notch processing and signaling (Searfoss et al., 2003; Wong et al., 2004).

Recently, Gleevec (signal transduction inhibitor 571, STI571, imantinib mesylate), a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has been described to lower Aβ in a cell-free system, in N2A cells expressing human APP, in rat primary neurons, and in guinea pig brain without inhibiting Notch cleavage (Netzer et al., 2003). Gleevec is an approved drug for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, and it inhibits primarily c-Abl, the platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs), and c-Kit (Druker et al., 1996; Buchdunger et al., 2000; Mauro et al., 2002). The Aβ-lowering effect of Gleevec has been shown not to be dependent on Abl kinase (Netzer et al., 2003). It has been proposed that Gleevec may act as an APP-selective γ-secretase inhibitor (Netzer et al., 2003), whereas others found no direct inhibition of γ-secretase activity in vitro (Fraering et al., 2005). The exact mechanism by which Gleevec leads to the reduction in Aβ is unknown.

Here, we confirm that Gleevec lowers Aβ levels without inhibiting Notch cleavage. In addition, we propose a mechanism distinct from γ-secretase inhibition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Antibodies

Gleevec was synthesized by Axxima Pharmaceuticals AG (Munich, Germany), and a 10 mM stock solution was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). NH4Cl (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) was dissolved to 5 M in H2O. The γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 dissolved in DMSO, and synthetic C50 peptide, representing the C-terminal 50 amino-acid-long AICD sequence of APP (APP721–770), were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The following antibodies were used: 6E10, and biotinylated 4G8 anti-APP monoclonal antibodies (Signet Laboratories, Dedham, MA), A8717 anti-APP C-terminal polyclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), T9026 monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), 9E10 anti-c-myc monoclonal antibody (mAb) (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), 56C6 anti-neprilysin mAb (Novocastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom), and anti-Fe65 antibody E-20 and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell Lines and Treatment

H4 human neuroglioma cells stably transfected with human APP751 (H4-APPwt), H4 cells stably overexpressing the Swedish FAD mutation (K670N/M671L) in human APP695 (H4-APPswe), and U373 astrocytoma cells stably transfected with human APP751 (U373-APPwt) were kindly provided by Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany). H4-Fe65i cells express human Fe65-Myc under the control of the tet off system (Gossen and Bujard, 1992). Expression is turned off by cultivation of cells with 100 ng/ml doxycyline and induced by washing out doxycyline from the culture medium and subsequent cell culture for 3 d. All cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. For experiments, cells were supplemented with fresh medium containing compounds at concentrations and for durations indicated. DMSO concentrations between samples were kept consistent, and DMSO-treated cells served as a control.

Aβ-Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Levels of total Aβ in conditioned cell medium of H4-APPwt cells were measured using a sandwich ELISA based on the mAb 6E10 and the biotinylated mAb 4G8. Capturing antibody 6E10, recognizing an epitope within amino acids 1–17 of human Aβ, was used to coat plastic dishes, whereas 4G8, which is reactive to amino acids 17–24 of Aβ, was used as detection antibody. Each data point was measured in triplicate. Percentage of remaining Aβ from Gleevec-treated cells was calculated in relation to conditioned cell medium from DMSO-treated cells as positive control (=100%) and tissue culture medium as negative control (=0%).

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymeth-oxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, Inner Salt (MTS)-Assay

Cell viability was measured using CellTiter 96 Aqueous NonRadioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The tetrazolium compound MTS is bioreduced by cells into a formazan product, which is directly proportional to the number of living cells in the culture. Percentage of viable cells after Gleevec treatment was calculated in relation to DMSO-treated control cells.

Immunoprecipitations and Western Blotting

Aβ was immunoprecipitated from equal volumes of conditioned cell culture medium of H4-APPwt cells by incubation with 6E10 antibody at 4°C overnight and subsequently with GammaBind Plus Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) at 4°C for 1 h. Beads were washed, and proteins were denatured in sample buffer. Equal volumes of conditioned cell medium were directly analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to detect Aβ from H4-APPswe cells or soluble α-secretase cleaved APP (APPs-α) from cell media. For detection of proteins from cell lysates, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1× Complete inhibitor mix [Roche Diagnostics], 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM 1,10-phenanthroline [Sigma-Aldrich], 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na-pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM Na-orthovanadate). APP, APPs-α, neprilysin, and Notch cleavage products were analyzed by 10% or 8% Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE. For detection of AICD and other APP C-terminal fragments, lysates were separated on 16.5%T 6% C Tricine SDS gels containing 6 M urea (Schagger and von Jagow, 1987). Aβ40 and Aβ42 were analyzed by 10% T 5% C Bicine/Tris, 8 M urea, SDS-PAGE (Wiltfang et al., 1997). For Western Blot detection, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride or nitrocellulose membranes. After antibody incubation, SuperSignal West Pico reagents (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) were used for detection. Representative blots from at least three independent experiments are shown.

Generation and Analysis of Aβ and AICD In Vitro

Aβ and AICD were generated in vitro from cell membrane preparations according to previously described procedures (Pinnix et al., 2001) with some changes. In brief, H4-APPswe cells were incubated with 100 nM γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 for 24 h to accumulate C-terminal fragments of APP. Cell pellets were resuspended (850 μl/15-cm dish) in hypotonic buffer (15 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.4, 5 mM EDTA, and 1× Complete protease inhibitor mix). Cells were homogenized and a postnuclear supernatant (PNS) was prepared as described previously (Steiner et al., 1998). Membranes were pelleted from PNS by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and then they were resuspended (1 ml/15-cm plate) in assay buffer (50 mM citrate, pH 6.4, 5 mM EDTA, 1× Complete inhibitor mix, and 2 mM 1,10-phenanthroline). To allow Aβ and AICD generation, 80 μl/assay was incubated at 37°C for 15 h. Control samples were kept on ice. After incubation, membranes were pelleted at 16,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Supernatant (1 μl) was analyzed for AICD by Western blot analysis with antibody A8717. For Aβ detection, membranes were resuspended in sample buffer and analyzed by 10% T 5% C Bicine/Tris, 8 M urea, SDS-PAGE (Wiltfang et al., 1997) and detection with 6E10 antibody.

Western Blot Quantification

Densitometric values of band intensities were analyzed using the public domain software ImageJ, version 1.34 (www.rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Statistical analysis was performed by the unpaired Student's t test by using the StatView 5.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and p values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Analysis of Notch Cleavage

Cells were transfected using FuGENE6 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Diagnostics). The plasmid used for NotchΔE-expression, pSC2ΔEMV-6MT (Schroeter et al., 1998), was a kind gift of Raphael Kopan (Washington University, St. Louis, MO). After transfection and treatment with the indicated compounds for 24 h, cells were lysed, and NotchΔE and Notch intracellular domain (NICD) levels were detected by Western blot with 9E10 antibody. Blots were quantified, and the ratio of NICD/NotchΔE was calculated.

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Cells were grown with DMSO or Gleevec treatment for 15 h. Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), and first-strand cDNA from 1 μg of RNA was synthesized with the Omniscript RT kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For real-time PCR reactions, 5 μl of 1:50 diluted cDNA per sample was mixed with 2xQuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (QIAGEN), 2.5 μl of QuantiTect Primer Assay (QIAGEN) MME for neprilysin detection, or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a housekeeping gene, in a total volume of 25 μl. PCR reactions were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol on a ABI PRISM 7000 machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each data point was measured in triplicate. Relative mRNA expression was calculated of the mean value with the comparative Ct method, and neprilysin expression of each sample was normalized to GAPDH expression. The -fold induction of neprilysin expression in Gleevec-treated cells compared with controls was calculated. The Pair Wise Fixed Reallocation Randomisation Test (Pfaffl et al., 2002) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

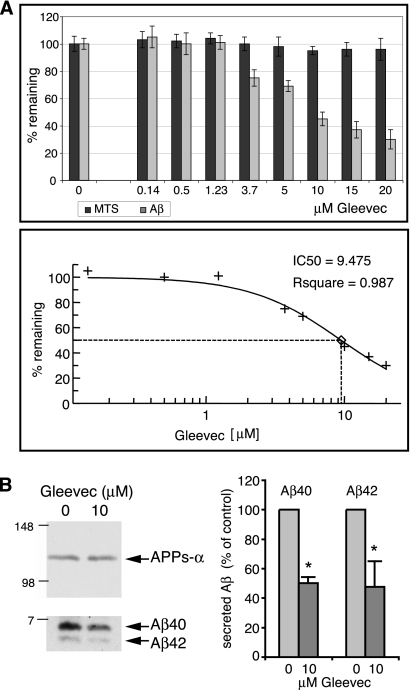

Gleevec Treatment Decreases Cell-secreted Aβ but Not APPs-α

H4 neuroglioma cells stably overexpressing APP751 (H4-APPwt) were incubated with increasing Gleevec concentrations for 20 h, and total Aβ secreted into cell media was measured by sandwich-ELISA (Figure 1A). We observed a dose-dependent decrease in total secreted Aβ with increasing Gleevec concentrations. The IC50 for inhibition of Aβ secretion was determined to be 9.5 μM. Cell viability was not impaired by Gleevec concentrations up to 20 μM, ruling out a reduction of Aβ due to cytotoxicity (Figure 1A, dark gray bars). Immunoprecipitation of secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 from conditioned cell medium followed by Western blot analysis revealed that treatment of cells with 10 μM Gleevec led to a decrease in both Aβ40 and Aβ42 by ∼50% (Figure 1B). Thus, Gleevec reduced total secreted Aβ without altering the Aβ40/42 ratio. In comparison the amount of secreted APPs-α remained unchanged by Gleevec treatment (Figure 1B), indicating that Gleevec did not affect α-secretase cleavage of APP.

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent decrease in secreted Aβ but not in secreted APPs-α after Gleevec treatment. (A) Conditioned medium from H4-APPwt cells treated with increasing Gleevec concentrations for 20 h was analyzed for total secreted Aβ by sandwich-ELISA. In parallel, the viability of treated cells was monitored by MTS assay. With increasing Gleevec concentrations, secreted Aβ decreased (top, light gray bars), whereas the viability of cells was unaffected by Gleevec (top, dark gray bars). The IC50 value for inhibition of Aβ secretion was calculated by nonlinear curve fitting of percentage of remaining Aβ values. (B) Analysis of Aβ40 and Aβ42 from conditioned medium of H4-APPwt cells treated with DMSO or 10 μM Gleevec for 24 h. Aβ was immunoprecipitated and analyzed by Western blot by using 6E10 antibody. Band intensities of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were quantified by densitometric analysis, and relative values are shown as percentage of control (n = 4, error bars represent SD; *p < 0.01, unpaired t test). Gleevec reduced secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 by ∼50%. Levels of secreted APPs-α, as analyzed by Western blot with 6E10 antibody, remained unchanged by Gleevec treatment.

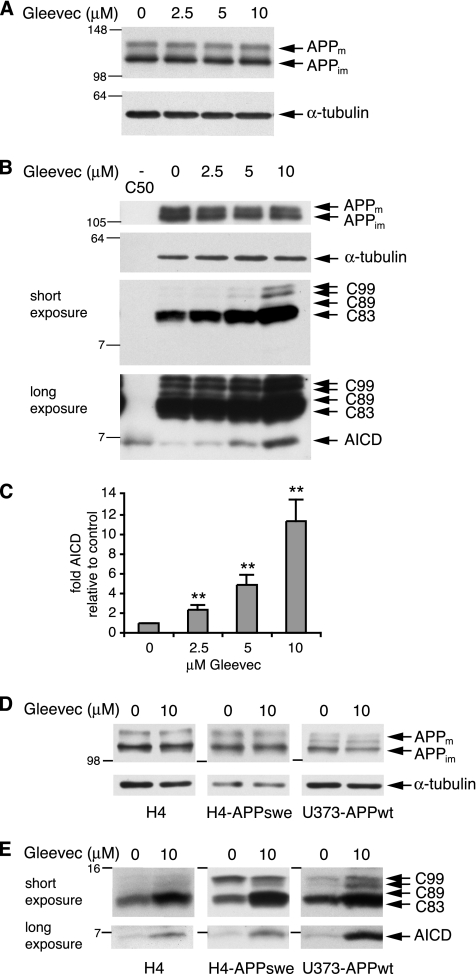

Dose-dependent Increase in AICD and APP C-Terminal Fragments after Gleevec Treatment

We next analyzed levels of APP and APP C-terminal fragments after treatment of H4-APPwt cells with increasing Gleevec concentrations. As shown in Figure 2, A and B, levels of full-length APP were not affected by treatment with Gleevec, whereas the APP cleavage products C83, C89, and C99 showed a dose-dependent increase (Figure 2B). We also found a prominent dose-dependent increase in the γ-secretase cleavage product AICD after treatment of cells with Gleevec (Figure 2B). Western Blot quantification revealed an approximate 10-fold increase in AICD with 10 μM Gleevec (Figure 2C), a concentration where Aβ decrease was around twofold (50% remaining; Figure 1, A and B). This result was unexpected, because it was proposed that Gleevec might inhibit γ-secretase (Netzer et al., 2003). However, inhibition of γ-secretase activity should result in a decrease in AICD rather than an increase, indicating that Gleevec might work via different mechanisms to decrease Aβ than was initially thought. We also analyzed untransfected H4 cells, which express low levels of endogenous APP, H4-APPswe cells overexpressing APP695 carrying the Swedish FAD mutation as well as U373-APPwt cells, which overexpress APP751. In all three cell lines Gleevec mediated an increase in AICD, C83, C89, and C99, while leaving levels of full-length APP unaffected (Figure 2, D and E). Thus, the observed effects seem independent of APP overexpression and occurred in different cell lines.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent increase in AICD and APP C-terminal fragments after Gleevec treatment. H4-APPwt cells were treated with increasing Gleevec concentrations as indicated for 24 h. (A) Full-length APP from cell lysates was analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE and Western blot by using 6E10 antibody. Mature (m) and immature (im) forms of APP are indicated. α-tubulin was detected as loading control. (B) AICD and APP C-terminal fragments were separated by 16.5% Tricine SDS-PAGE and detected with antibody A8717. Full-length APP levels remained unchanged, whereas APP C-terminal fragments C83, C89, and C99 (short exposure), as well as AICD (long exposure) showed a Gleevec-dependent increase. Synthetic C50 peptide was loaded as a size control for AICD (see first lane). (C) Densitometric analysis of AICD band intensities. The -fold increase in AICD relative to control is shown (n = 5, error bars represent SD; **p < 0.001, unpaired t test). (D and E) H4, H4-APPswe or U373-APPwt cells were treated with DMSO or 10 μM Gleevec for 24 h. (D) Cell lysates were analyzed for full-length APP as described in A. (E) Analysis of AICD and APP C-terminal fragments as in B. All three cell lines showed a Gleevec dose-dependent increase in AICD and APP C-terminal fragments, whereas APP expression remained unchanged.

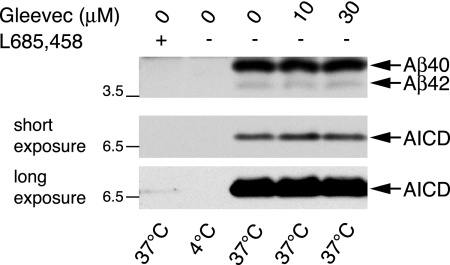

Gleevec Does Not Influence γ-Secretase Activity In Vitro

We next asked whether the effects of Gleevec that we observed in cells might be caused by a direct effect of Gleevec on the γ-secretase complex. We therefore tested the effect of Gleevec on γ-secretase activity in vitro, by using membrane preparations from H4-APPswe cells containing intact γ-secretase and a high amount of C99 fragments serving as the γ-secretase substrate. Incubation of membrane fractions at 37°C resulted in the generation of Aβ40 and a lesser amount of Aβ42, and in the generation of AICD, none of which were produced at 4°C (Figure 3). Aβ and AICD generation were strongly inhibited with the potent γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 (Shearman et al., 2000). In contrast, incubation of membrane fractions with Gleevec did not inhibit the in vitro generation of Aβ nor did it influence the in vitro generation of AICD. We did not observe an effect of Gleevec at 10 μM, which was effective in cells, and even a higher concentration of 30 μM showed no effect on γ-secretase cleavage in vitro (Figure 3). Our results do not indicate a direct action of Gleevec on the γ-secretase complex to enhance AICD or inhibit Aβ generation.

Figure 3.

Gleevec does not directly influence γ-secretase activity in vitro. Generation of AICD and Aβ was analyzed in vitro by using membrane preparations of H4-APPswe cells containing the γ-secretase complex and its substrate C99. Incubation of membrane fractions at 37°C led to the generation of Aβ and AICD by γ-secretase, whereas one reaction was kept at 4°C as a negative control with no enzymatic activity. To test a potential effect on γ-secretase activity in vitro, 10 or 30 μM Gleevec or 1 μM γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 was included in the reactions where indicated. After termination of the reactions, Aβ levels were analyzed by Western blot using 6E10 antibody (top) and levels of AICD were detected with antibody A8717 (middle and bottom). Middle, a short exposure to compare Gleevec-treated samples. Bottom, a longer exposure detecting minor amounts of AICD in L-685,458–treated samples but not in the 4°C negative control.

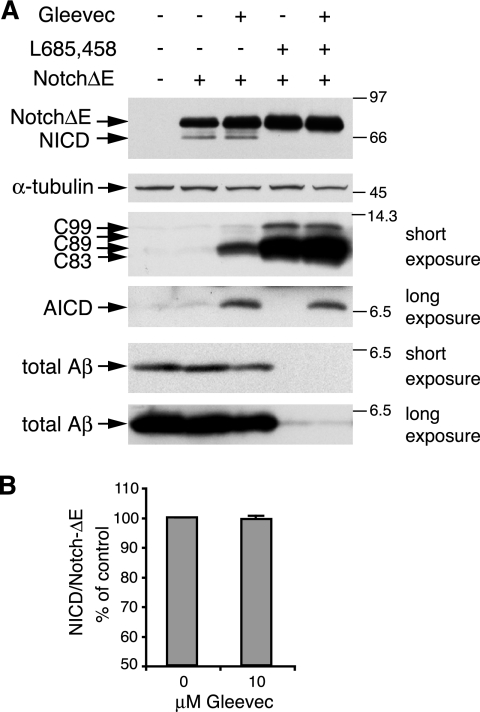

Gleevec Does Not Affect Generation of the NICD, but Increases AICD Even in the Presence of a γ-Secretase Inhibitor

To analyze the effect of Gleevec on cleavage of the Notch receptor, H4-APPswe cells were transfected with a NotchΔE construct that is constitutively processed by γ-secretase. NotchΔE and the generated NICD were detected from cell lysates by Western blot analysis. Incubation of cells with Gleevec had no effect on NICD generation (Figure 4, A and B), whereas AICD, C83, C89, and C99 increased and Aβ decreased (Figure 4A), as described above. As expected, treatment of cells with the γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 effectively inhibited the generation of all three γ-secretase cleavage products, NICD, AICD, and Aβ, and it led to a strong accumulation of C83, C89, and C99 fragments (Figure 4A). A striking observation was that in cells treated with both Gleevec and L-685,458, we still found a prominent AICD increase, even in the presence of the γ-secretase inhibitor. Gleevec did not prevent γ-secretase inhibition by L-685,458, because NICD and Aβ generation were still reduced, and C99 and C83 still accumulated as seen with L-685,458 treatment alone (Figure 4A, compare last two lanes). These findings indicate that the Gleevec-mediated AICD increase is not caused by enhanced γ-secretase cleavage. In higher exposures we observed that small amounts of Aβ were still detected even when cells were treated with γ-secretase inhibitor (Figure 4, bottom-most panel, last two lanes), suggesting that low γ-secretase activity still produced small amounts of Aβ and AICD. Similarly, a residual production of AICD was seen after γ-secretase inhibition in the above-mentioned in vitro experiments (Figure 3). These results suggest that Gleevec treatment of cells might slow down the turnover of AICD, such that low amounts of AICD are rendered more stable and accumulate over time. Similarly, the increase in C83 and C99 fragments after Gleevec treatment might be caused by a slowed turnover of these fragments by mechanisms not involving γ-secretase cleavage.

Figure 4.

Influence of Gleevec and γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458 on Notch cleavage, APP C-terminal fragments, and Aβ. (A) NICD generation was analyzed by transient transfection of H4-APPswe cells with a myc-tagged NotchΔE construct, which is constitutively cleaved by γ-secretase to generate NICD. Cells were transfected and immediately treated with DMSO, 10 μM Gleevec, 1 μM γ-secretase inhibitor L-685,458, or with both 10 μM Gleevec and 1 μM L685,458 in combination for 24 h. Subsequently, NotchΔE expression and NICD generation were analyzed in cell lysates by using myc-tag–specific antibody 9E10 (top). The amount of APP C-terminal fragments in lysates was assessed by Western blot with antibody A8717 (middle). A shorter exposure to detect C99, C89, and C83 and a longer exposure detecting AICD from the same blot is shown. Total Aβ from conditioned cell media was analyzed with 6E10 antibody (bottom). Two different exposures from the same blot are shown. (B) Band intensities of NICD and NotchΔE were quantified by densitometric analysis from three independent experiments and NICD/NotchΔE ratios were calculated. Gleevec treatment did not influence NICD generation.

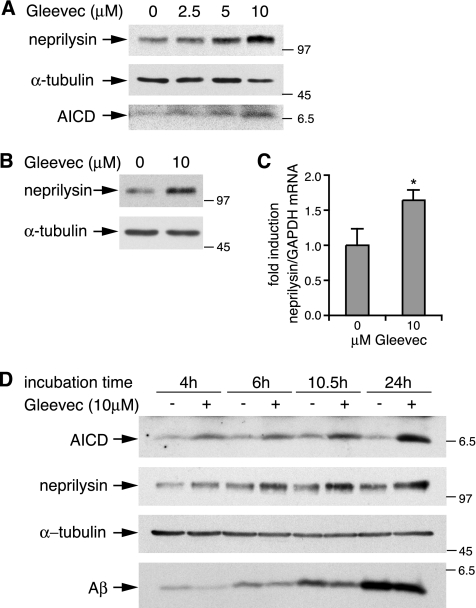

Increased Expression of the Aβ-degrading Enzyme Neprilysin after Gleevec Treatment

The results so far showed that Gleevec led to a strong increase in AICD and a decrease in Aβ, which seemed independent of γ-secretase inhibition. Enhanced APP-cleavage by α-secretase could also not account for the Aβ-lowering effect of Gleevec, because levels of APPs-α remained unchanged (Figure 1B). Thus, we sought an alternative mechanism by which Gleevec might mediate the decrease in Aβ. It is known that not only Aβ production but also Aβ degradation plays an important role in the regulation of Aβ levels (Turner et al., 2004). Several proteases have been found to degrade Aβ, one of which is the metalloprotease neprilysin (Carson and Turner, 2002). Moreover, AICD has been implicated in activation of gene expression (Cao and Sudhof, 2001) and recently the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin has been described as a potential target gene of AICD signaling (Pardossi-Piquard et al., 2005, 2006). Because Gleevec led to greatly enhanced AICD levels in our cells, we next tested whether neprilysin expression was changed by Gleevec. As shown in Figure 5A, neprilysin protein levels in H4-APPswe cells increased with increasing Gleevec, and concurrently increasing AICD concentrations. A similar rise in neprilysin levels was found in H4-APPwt cells (Figure 5B), and in untransfected H4 cells (data not shown). Concomitant with elevated neprilysin protein levels, neprilysin mRNA levels were also significantly elevated after Gleevec treatment, as measured by real-time PCR analyses (Figure 5C). Increases in AICD and neprilysin were both already detectable after 4 h of Gleevec treatment and levels of AICD and neprilysin further accumulated over time (Figure 5D, top and middle). Together, these results show that the AICD and neprilysin increase were correlated in dose and time, suggesting that increased AICD levels might lead to enhanced neprilysin gene expression. Analysis of secreted Aβ from conditioned cell media showed that the Gleevec-mediated decrease in Aβ was already detected after 4 h and followed a similar time course as neprilysin and AICD up-regulation (Figure 5D, bottom).

Figure 5.

Gleevec treatment leads to up-regulation of neprilysin protein and mRNA levels. (A) Analysis of neprilysin and AICD levels in Gleevec-treated H4-APPswe cells. After treatment of cells with increasing Gleevec concentrations for 20 h, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot with the neprilysin-specific antibody 56C6, and subsequently with an α-tubulin specific antibody, serving as a loading control. AICD from cell lysates was analyzed with antibody A8717. Parallel to an increase in AICD up-regulated expression of neprilysin was observed. (B) Analysis of neprilysin protein levels in H4-APPwt cells. Cells were treated with 10 μM Gleevec or DMSO for 15 h and neprilysin and α-tubulin protein levels were analyzed by Western blot as described in A. (C) Analysis of neprilysin mRNA levels from H4-APPwt cells treated as described in B. Neprilysin expression was measured by real-time PCR and normalized to expression of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. The -fold change of neprilysin mRNA in Gleevec-treated cells was 1.64-fold up-regulated (n = 7, error bars represent SD; *p < 0,05, Pair Wise Fixed Reallocation Randomisation Test). (D) Time course of AICD and neprilysin increase and Aβ decrease. H4-APPswe cells, treated with 10 μM Gleevec or DMSO for the times indicated, were lysed and AICD, neprilysin, and α-tubulin were analyzed as described in A. Aβ from conditioned cell media was analyzed by Western blot with 6E10 antibody. As expected, total Aβ in the cell medium increased over time from 4 to 24 h. Comparison of Aβ from Gleevec-treated cells to controls per time point showed a Gleevec mediated reduction in total Aβ.

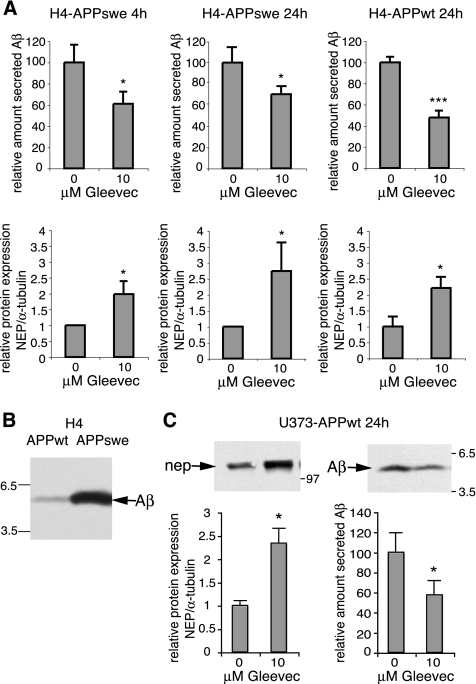

Gleevec-mediated Neprilysin Up-Regulation and Aβ Decrease Occur in Different Cell Lines

Neprilysin up-regulation after Gleevec treatment may lead to a decrease in Aβ by enhancing Aβ-degradation. To further investigate this correlation, we quantified neprilysin and Aβ levels from H4-APPswe cells after 4 and 24 h of Gleevec treatment, as used in the time course experiments described above, and in H4-APPwt cells after 24 h of Gleevec treatment. The results show a significant reduction in Aβ secreted from H4-APPswe cells 4 and 24 h after treatment, which was in the range of 61 and 70% compared with control cells (Figure 6A). In H4-APPwt cells, a higher reduction in Aβ to ∼48% of control was observed (Figure 6A), in line with the ELISA results described above (Figure 1). Neprilysin was up-regulated in both cell lines to a similar extend or slightly higher in H4-APPswe cells 24 h after treatment (Figure 6A). Less reduction in Aβ in H4-APPswe cells could be explained by the fact that these cells secrete six to eightfold higher levels of Aβ than H4-APPwt cells (Figure 6B), due to the Swedish mutation (Citron et al., 1992; Cai et al., 1993). A reduction in secreted Aβ from these cells can be expected to be less efficient by comparable amounts of neprilysin, because higher amounts of Aβ have to be degraded. In U373-APPwt cells, a similar neprilysin increase and Aβ-decrease as in H4-APPwt cells was observed (Figure 6C). Together, these results suggest that Gleevec might lower Aβ by increasing levels of neprilysin and thereby enhancing Aβ-degradation.

Figure 6.

Gleevec-mediated neprilysin up-regulation and concomitant decrease in secreted Aβ in different cell lines. (A) H4-APPswe and H4-APPwt cells treated with 10 μM Gleevec or DMSO for the indicated times were analyzed for secreted Aβ and neprilysin expression by Western blot and quantified by densitometric analysis. Neprilysin expression was normalized to α-tubulin. The relative amount compared with controls is shown. H4-APPswe cells treated with Gleevec for 4 h showed a twofold increase in neprilysin and a decrease in secreted Aβ to 61% of control (n = 8 and n = 3, respectively). In H4-APPswe cells 24 h after Gleevec treatment a 2.7-fold increase in neprilysin and a decrease in secreted Aβ to 70% of control was measured (n = 4 and n = 3, respectively). Neprilysin upregulation in H4-APPwt cells was 2.2-fold, and Aβ secretion was decreased to 48% of control (n = 4). Error bars represent SD; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.0001, unpaired t test. (B) H4-APPswe cells secrete six- to eightfold higher levels of Aβ than H4-APPwt cells due to the Swedish mutation. Aβ levels from conditioned medium of both cell lines is compared by Western blot analysis. (C) Analysis of neprilysin expression and Aβ secretion in U373-APPwt cells after 24 h of Gleevec treatment. Neprilysin expression normalized to α-tubulin was 2.3-fold, and Aβ secretion was reduced to 57% of controls (n = 3, error bars represent SD; *p < 0.05, unpaired t test).

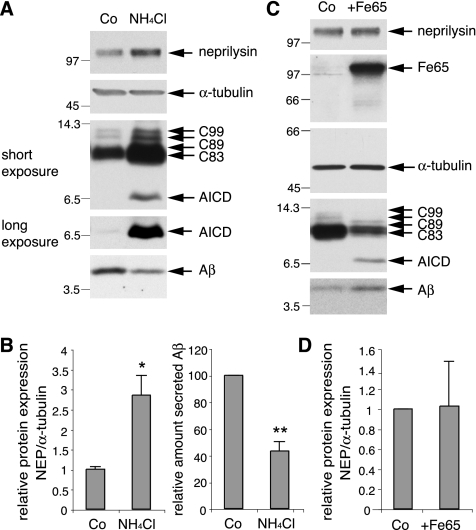

Increase in AICD by Treatment with the Alkalizing Agent NH4Cl but Not by Fe65 Overexpression Is Accompanied by Neprilysin Upregulation and Aβ Decrease

AICD may cause neprilysin up-regulation and thereby mediate Aβ decrease or both effects could be independent of each other. There is evidence in the literature favoring AICD-mediated neprilysin transcription (Pardossi-Piquard et al., 2005, 2006, 2007) and contradicting reports (Hebert et al., 2006; Chen and Selkoe, 2007). The mechanism of AICD signaling has not been fully elucidated. Recently, a study was published demonstrating that alkalizing drugs, that impair endosomal/lysosomal degradation, lead to an increase in AICD and APP C-terminal fragments and a decrease in Aβ (Vingtdeux et al., 2007), similar to the results we obtained with Gleevec. To further investigate the correlation between an AICD increase and neprilysin up-regulation, H4-APPwt cells were treated with the alkalizing agent NH4Cl. Subsequently, AICD, APP–carboxyl-terminal fragment (CTFs), neprilysin, and secreted Aβ levels were analyzed by Western blot. The results confirm the findings of Vingtdeux et al. (2007), and they show a pronounced increase in AICD and APP C-terminal fragments. Concomitant with the AICD increase, neprilysin levels were up-regulated and secreted Aβ was decreased (Figure 7, A and B). Possibly impaired AICD degradation via the endosomal/lysosomal system after NH4Cl treatment may lead to enhanced AICD-mediated transcription of neprilysin and thus to an Aβ-decrease via similar mechanisms as Gleevec.

Figure 7.

Increase in AICD by alkalizing agent NH4Cl and by Fe65 overexpression have different effects on neprilysin and Aβ. (A) Treatment of H4-APPwt cells with 5 mM NH4Cl led to a strong increase in APP C-terminal fragments, including AICD. Concomitantly, neprilysin protein levels were increased and Aβ levels were decreased. Densitometric analysis of relative neprilysin expression and relative amount of secreted Aβ is shown in B. Neprilysin was 2.8-fold up-regulated, and Aβ secretion was decreased to 43% of control (n = 3, error bars represent SD; *p < 0.01, **p < 0.001, unpaired t test). (C) H4-Fe65i cells, expressing Fe65 under control of the tet-off system, were maintained with doxycycline for 3 d (Co), or Fe65 overexpression was induced by cultivating cells without doxycycline for 3 d (+Fe65). Fe65-expression, neprilysin, APP C-terminal fragments, and Aβ from these cells are shown. Although Fe65 overexpression led to an increase in AICD, larger APP C-terminal fragments were decreased. Concomitantly, Aβ levels increased. Neprilysin expression was not significantly affected by Fe65-mediated AICD induction. Densitometric quantification is shown in D.

The adaptor protein Fe65 has been implicated in AICD-mediated transcriptional regulation (Cao and Sudhof, 2001) and Fe65 binding may stabilize AICD (Kimberly et al., 2001, 2005); however, this effect was not observed in all reports (Cupers et al., 2001; Nakaya and Suzuki, 2006). To further investigate whether Fe65 could be a player in enhanced AICD stability, neprilysin expression, and concomitant Aβ decrease, we analyzed the effect of Fe65 on AICD stability and neprilysin expression. We used H4-Fe65i cells overexpressing Fe65 under the control of the “tet-off system” (Gossen and Bujard, 1992). Induction of Fe65 overexpression in these cells led to higher AICD levels; however, APP-CTFs were found to be decreased (Figure 7C). This finding could point to a higher turnover of APP-CTFs by γ-secretase, thus leading to higher AICD generation. In line with that, Aβ levels were increased after Fe65 overexpression (Figure 7C). Although levels of AICD were increased, neprilysin was not significantly up-regulated in these cells (Figure 7, C and D). Thus, the effect of Fe65 overexpression on APP metabolism in H4 cells clearly differs from that of Gleevec treatment.

DISCUSSION

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor Gleevec has acquired interest as a potential basis for novel Aβ-lowering drugs in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. In the present study, we investigated the mechanism by which Gleevec influences Aβ levels. Gleevec treatment led to a dose-dependent decrease in cell-secreted Aβ, and it did not inhibit Notch cleavage, in line with previously published results (Netzer et al., 2003). However, simultaneously, a dose-dependent increase in the γ-secretase cleavage product AICD was observed. This novel result cannot be explained by either direct or indirect inhibition of γ-secretase by Gleevec, because this should result in a decrease in both AICD and Aβ. In addition, Gleevec did not directly influence γ-secretase activity in vitro, an observation that has also been reported by others (Fraering et al., 2005). Differential effects on γ- and ε-cleavage have been described for some presenilin (PS) mutants linked to familial AD cases (Chen et al., 2002; Moehlmann et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2005; Bentahir et al., 2006). Possibly, Gleevec might indirectly influence γ-secretase activity and cause a shift in cleavage by activating ε-cleavage, resulting in more AICD, and inhibiting γ-cleavage, resulting in lower Aβ. However, Gleevec treatment of cells increased C99 and C83, which would be expected to decrease if Gleevec led to enhanced ε-cleavage. In addition, modulation of γ-secretase activity by PS mutations, in the reports cited above, always involved changes in the Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio, which we and others (Netzer et al., 2003) did not observe with Gleevec. Together, these data strongly suggest that Gleevec lowers Aβ levels and increases AICD by a mechanism distinct from γ-secretase inhibition or modulation.

As an alternative mechanism leading to elevated AICD levels in cells, we propose that in Gleevec-treated cells, the stability of AICD may be highly increased. Supporting this, Gleevec still led to higher AICD levels, even when coincubated with a potent γ-secretase inhibitor. We interpret this finding in the way that small amounts of AICD still produced under these conditions have a slower rate of turnover and accumulate in Gleevec-treated cells. The mechanism by which AICD may be stabilized by Gleevec is not known. Possibly, it might involve changes in phosphorylation of AICD and the interaction with its binding partners. The C-terminus of APP contains a consensus motif (682YENPTY687) that interacts with the phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domains of several cytoplasmic adaptor proteins, including Fe65, X11, JIP1-B, JIP2, mDab1, Numb and ShcA (Borg et al., 1996; Howell et al., 1999; Roncarati et al., 2002; Russo et al., 2002; Scheinfeld et al., 2002; Tarr et al., 2002b). Phosphorylation of AICD at T668 influences AICD stability and leads to destabilization of AICD during differentiation of primary neurons in culture (Kimberly et al., 2005). Among the several kinases that have been described to phosphorylate APP at T668 (Suzuki et al., 1994; Aplin et al., 1996; Iijima et al., 2000; Taru and Suzuki, 2004; Kimberly et al., 2005), the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) seems to play an important role in vivo (Kimberly et al., 2005). JNK is a serine/threonine kinase, but it may be activated by pathways involving receptor tyrosine kinases, e.g., the PDGFR (Yu et al., 2003) and c-Kit (Hong et al., 2004), which can be inhibited by Gleevec. Binding of the adaptor protein Fe65 may be regulated by phosphorylation of APP at T668 (Ando et al., 2001; Kimberly et al., 2005), and it has been implicated in AICD stabilization (Kimberly et al., 2001, 2005). In other reports, Fe65 did not show a stabilizing effect on AICD (Cupers et al., 2001; Nakaya and Suzuki, 2006). We found that overexpression of Fe65 in H4 cells increased the level of AICD. However this effect seemed to be caused by enhanced γ-cleavage of APP and not by AICD stabilization, because APP C-terminal fragments were decreased, and the amount of secreted Aβ increased. This finding is in line with previously published results, that overexpression of Fe65L1 in H4 cells enhances γ-secretase processing of APP (Chang et al., 2003). Concluding from these results, the stabilizing effect of Gleevec on AICD is probably not mediated by enhanced binding of Fe65. Apart from Fe65 also ShcA binds to APP in a phosphorylation-dependent manner, possibly involving the receptor tyrosine kinase TrkA, and it has been reported to decrease levels of AICD (Tarr et al., 2002a). Binding of other partners to the APP-C terminus occurs independently of APP phosphorylation. Alternatively to changing the binding of AICD binding proteins, Gleevec might interfere with enzymes involved in AICD degradation. Insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) has been shown to mediate degradation of AICD (Edbauer et al., 2002; Farris et al., 2003) and also of Aβ. Inhibition of its activity should lead to an increase in both AICD and Aβ, as is observed in IDE knockout mice (Farris et al., 2003). Recently, it has been described that alkalizing drugs induce the accumulation of AICD, likely mediated by the endosome/lysosome pathway (Vingtdeux et al., 2007). We found that treatment of cells with the alkalizing agent NH4Cl led to a strong increase in AICD and APP C-terminal fragments very similarly to the effect observed with Gleevec treatment. Thus, it seems possible that Gleevec interferes with endosomal/lysosomal degradation of AICD. Also, the degradation of APP C-terminal fragments that accumulate after Gleevec treatment has been attributed to lysosomes (Golde et al., 1992; Haass et al., 1992). A possible target might be the vacuolar H+-ATPase, because Gleevec can bind to and block ATP binding sites (Mauro et al., 2002).

Apart from the inhibition of γ-secretase activity, Aβ-reduction can also result from activation of the nonamyloidogenic pathway of APP processing, which may occur via protein kinase C and lead to enhanced α-cleavage of APP (Buxbaum et al., 1993). Although Gleevec led to accumulation of the α-secretase cleavage product C83, we and others (Netzer et al., 2003) did not observe changes in secreted APPs-α from Gleevec-treated cells. These results indicate that Gleevec does not lower Aβ via enhancing the nonamyloidogenic pathway of APP processing. As discussed above, the observed increase in C83 is presumed to occur via impaired degradation of APP C-terminal fragments.

The Gleevec-mediated decrease in Aβ seems to involve other mechanisms than inhibition of γ-secretase or activation of α-secretase. Because AICD has been implicated in transcriptional regulation (Cao and Sudhof, 2001), increased AICD levels after Gleevec treatment may lead to changes in AICD-regulated gene expression causing the observed Aβ-lowering effect. Supporting this, we found a Gleevec dose-dependent increase in the Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin, a putative target gene of AICD signaling (Pardossi-Piquard et al., 2005, 2006), which correlated in dose and time with higher AICD levels. In line with transcriptional activation, increased neprilysin mRNA levels were also observed after Gleevec treatment. Further support for a correlation of increased AICD levels and neprilysin up-regulation comes from the observation that alkalizing drug treatment, leading to increased AICD levels similar to Gleevec treatment, also up-regulated neprilysin levels and decreased secreted Aβ. In contrast, overexpression of Fe65, which is thought to be involved in transcriptional activation via AICD (Cao and Sudhof, 2001), led to an increase in AICD and Aβ levels, probably via enhanced γ-secretase processing. Although AICD levels were increased, neprilysin levels remained unchanged. The effect of Fe65 overexpression clearly differs from the effect of Gleevec treatment, so that Gleevec-mediated changes in the binding of Fe65 to APP or AICD seem unlikely to be the cause of AICD stabilization and neprilysin up-regulation. Concluding from these results, mere elevation of AICD levels may not be sufficient to up-regulate neprilysin expression in H4 cells. Other factors, such as changes in phosphorylation or cellular localization of AICD or its binding partners, might be involved that could be caused by Gleevec and NH4Cl treatment but not by Fe65 overexpression. Results presented here point to a role of AICD in neprilysin up-regulation; however, it cannot be completely ruled out that Gleevec treatment may lead to neprilysin up-regulation independent of AICD.

The balance between anabolism and catabolism of Aβ determines actual Aβ levels, such that a reduction in amyloid levels may be achieved by enhanced Aβ-degradation. The proteases neprilysin (Hama et al., 2001; Iwata et al., 2001; Leissring et al., 2003; Marr et al., 2004), IDE (Farris et al., 2003), and endothelin-converting enzyme (Eckman et al., 2003) have been implicated in the degradation of Aβ peptides. Because we found a dose-dependent increase in levels of neprilysin after Gleevec treatment, our results suggest that the concomitant dose-dependent decrease in Aβ may be caused by enhanced Aβ-degradation by neprilysin. In line with that, neprilysin-up-regulation also correlated with Aβ-decrease in time course experiments. Gleevec-mediated reduction in secreted Aβ from H4-APPswe cells was less efficient than in H4-APPwt cells, probably because H4-APPswe cells secrete six- to eightfold higher Aβ levels, such that higher amounts of Aβ have to be degraded by comparable neprilysin levels.

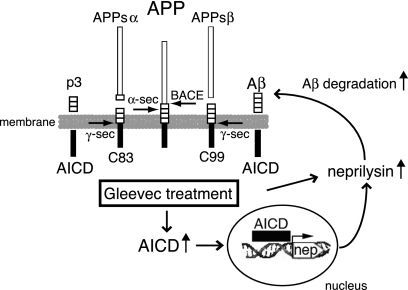

Together, we propose the following working model (Figure 8). Gleevec treatment increases levels of AICD by slowing down its rate of turnover. Neprilysin expression is increased, due to enhanced AICD signaling or an alternative mechanism, leading to increased Aβ degradation.

Figure 8.

Working Model of Gleevec Mechanism. Gleevec treatment increases AICD levels via a slowed turnover of AICD. Neprilysin expression is increased by Gleevec, mediated by transcriptional activation, which probably involves AICD signaling. Increased neprilysin expression may lower Aβ levels by enhanced degradation. α-sec, α-secretase; γ-sec, γ-secretase; nep, neprilysin gene.

The presented results show that Gleevec reduces the amount of secreted Aβ without influencing γ-secretase cleavage of APP or Notch signaling and thus meets important safety criteria required from a potential therapeutic drug. Because Gleevec itself does not cross the blood-brain barrier, it cannot be used as a drug to reduce Aβ in the brain of patients; however, it represents a very useful tool to investigate new mechanisms involved in the regulation of Aβ levels. An attractive therapeutic strategy for the treatment of AD may be the up-regulation of neprilysin expression in the brain (Hama et al., 2001; Leissring et al., 2003; Marr et al., 2003). The presented results provide the basis for future analyses of the underlying signaling mechanisms leading to AICD stabilization and neprilysin upregulation, and it may lead to new strategies of increasing neprilysin expression in the brain and the discovery of new targets for Aβ-lowering drugs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Sommer and C. Dorner-Ciossek (Biberach, Germany) for sharing H4-APPwt, H4-APPswe, and U373-APPwt cell lines; R. Kopan (St. Louis, MO) for the pSC2ΔEMV-6MT construct; and H. Steiner (Munich, Germany) and M. Calhoun and J. Coomaraswamy (Tuebingen, Germany) for critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the University of Tuebingen, Fortuene grant F1314009 (to E.K.).

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0035) on July 11, 2007.

REFERENCES

- Ando K., Iijima K. I., Elliott J. I., Kirino Y., Suzuki T. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of the interaction of amyloid precursor protein with Fe65 affects the production of beta-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40353–40361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin A. E., Gibb G. M., Jacobsen J. S., Gallo J. M., Anderton B. H. In vitro phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic domain of the amyloid precursor protein by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J. Neurochem. 1996;67:699–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek S. H., Ohgi K. A., Rose D. W., Koo E. H., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. Exchange of N-CoR corepressor and Tip60 coactivator complexes links gene expression by NF-kappaB and beta-amyloid precursor protein. Cell. 2002;110:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00809-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentahir M., Nyabi O., Verhamme J., Tolia A., Horre K., Wiltfang J., Esselmann H., De Strooper B. Presenilin clinical mutations can affect gamma-secretase activity by different mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:732–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg J. P., Ooi J., Levy E., Margolis B. The phosphotyrosine interaction domains of X11 and FE65 bind to distinct sites on the YENPTY motif of amyloid precursor protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6229–6241. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchdunger E., Cioffi C. L., Law N., Stover D., Ohno-Jones S., Druker B. J., Lydon N. B. Abl protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 inhibits in vitro signal transduction mediated by c-kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;295:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum J. D., Koo E. H., Greengard P. Protein phosphorylation inhibits production of Alzheimer amyloid beta/A4 peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:9195–9198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. D., Golde T. E., Younkin S. G. Release of excess amyloid beta protein from a mutant amyloid beta protein precursor. Science. 1993;259:514–516. doi: 10.1126/science.8424174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Sudhof T. C. A transcriptionally [correction of transcriptively] active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science. 2001;293:115–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1058783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson J. A., Turner A. J. beta-Amyloid catabolism: roles for neprilysin (NEP) and other metallopeptidases? J. Neurochem. 2002;81:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Tesco G., Jeong W. J., Lindsley L., Eckman E. A., Eckman C. B., Tanzi R. E., Guenette S. Y. Generation of the beta-amyloid peptide and the amyloid precursor protein C-terminal fragment gamma are potentiated by FE65L1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51100–51107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A. C., Selkoe D. J. Response to: Pardossi-Piquard et al., “Presenilin-dependent transcriptional control of the Abeta-degrading enzyme neprilysin by intracellular domains of betaAPP and APLP”. Neuron. 2007;46:541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.008. Neuron 53, 479–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Gu Y., Hasegawa H., Ruan X., Arawaka S., Fraser P., Westaway D., Mount H., St George-Hyslop P. Presenilin 1 mutations activate gamma 42-secretase but reciprocally inhibit epsilon-secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and S3-cleavage of notch. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:36521–36526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron M., Oltersdorf T., Haass C., McConlogue L., Hung A. Y., Seubert P., Vigo-Pelfrey C., Lieberburg I., Selkoe D. J. Mutation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein in familial Alzheimer's disease increases beta-protein production. Nature. 1992;360:672–674. doi: 10.1038/360672a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupers P., Orlans I., Craessaerts K., Annaert W., De Strooper B. The amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cytoplasmic fragment generated by gamma-secretase is rapidly degraded but distributes partially in a nuclear fraction of neurones in culture. J. Neurochem. 2001;78:1168–1178. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druker B. J., Tamura S., Buchdunger E., Ohno S., Segal G. M., Fanning S., Zimmermann J., Lydon N. B. Effects of a selective inhibitor of the Abl tyrosine kinase on the growth of Bcr-Abl positive cells. Nat. Med. 1996;2:561–566. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckman E. A., Watson M., Marlow L., Sambamurti K., Eckman C. B. Alzheimer's disease beta-amyloid peptide is increased in mice deficient in endothelin-converting enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2081–2084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200642200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbauer D., Willem M., Lammich S., Steiner H., Haass C. Insulin-degrading enzyme rapidly removes the β-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13389–13393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111571200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evin G., Sernee M. F., Masters C. L. Inhibition of gamma-secretase as a therapeutic intervention for Alzheimer's disease: prospects, limitations and strategies. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:351–372. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farris W., Mansourian S., Chang Y., Lindsley L., Eckman E. A., Frosch M. P., Eckman C. B., Tanzi R. E., Selkoe D. J., Guenette S. Insulin-degrading enzyme regulates the levels of insulin, amyloid beta-protein, and the beta-amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:4162–4167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230450100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraering P. C., Ye W., LaVoie M. J., Ostaszewski B. L., Selkoe D. J., Wolfe M. S. gamma-Secretase substrate selectivity can be modulated directly via interaction with a nucleotide-binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:41987–41996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501368200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golde T. E., Estus S., Younkin L. H., Selkoe D. J., Younkin S. G. Processing of the amyloid protein precursor to potentially amyloidogenic derivatives. Science. 1992;255:728–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1738847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M., Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C., Koo E. H., Mellon A., Hung A. Y., Selkoe D. J. Targeting of cell-surface beta-amyloid precursor protein to lysosomes: alternative processing into amyloid-bearing fragments. Nature. 1992;357:500–503. doi: 10.1038/357500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hama E., Shirotani K., Masumoto H., Sekine-Aizawa Y., Aizawa H., Saido T. C. Clearance of extracellular and cell-associated amyloid beta peptide through viral expression of neprilysin in primary neurons. J. Biochem. 2001;130:721–726. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass M. R., Yankner B. A. A [gamma]-secretase-independent mechanism of signal transduction by the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:36895–36904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502861200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert S. S., Serneels L., Tolia A., Craessaerts K., Derks C., Filippov M. A., Muller U., De Strooper B. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis of amyloid precursor protein and regulation of expression of putative target genes. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:739–745. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L., Munugalavadla V., Kapur R. c-Kit-mediated overlapping and unique functional and biochemical outcomes via diverse signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1401–1410. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1401-1410.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell B. W., Lanier L. M., Frank R., Gertler F. B., Cooper J. A. The disabled 1 phosphotyrosine-binding domain binds to the internalization signals of transmembrane glycoproteins and to phospholipids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5179–5188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima K., Ando K., Takeda S., Satoh Y., Seki T., Itohara S., Greengard P., Kirino Y., Nairn A. C., Suzuki T. Neuron-specific phosphorylation of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein by cyclin-dependent kinase 5. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:1085–1091. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata N., Tsubuki S., Takaki Y., Shirotani K., Lu B., Gerard N. P., Gerard C., Hama E., Lee H. J., Saido T. C. Metabolic regulation of brain Abeta by neprilysin. Science. 2001;292:1550–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1059946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. S., et al. C-terminal fragments of amyloid precursor protein exert neurotoxicity by inducing glycogen synthase kinase-3beta expression. FASEB J. 2003;17:1951–1953. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0106fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly W. T., Zheng J. B., Guenette S. Y., Selkoe D. J. The intracellular domain of the beta-amyloid precursor protein is stabilized by Fe65 and translocates to the nucleus in a notch-like manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:40288–40292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberly W. T., Zheng J. B., Town T., Flavell R. A., Selkoe D. J. Physiological regulation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein signaling domain by c-Jun N-terminal kinase JNK3 during neuronal differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5533–5543. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4883-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R., Ilagan M. X. Gamma-secretase: proteasome of the membrane? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:499–504. doi: 10.1038/nrm1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leissring M. A., Farris W., Chang A. Y., Walsh D. M., Wu X., Sun X., Frosch M. P., Selkoe D. J. Enhanced proteolysis of beta-amyloid in APP transgenic mice prevents plaque formation, secondary pathology, and premature death. Neuron. 2003;40:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr R. A., Guan H., Rockenstein E., Kindy M., Gage F. H., Verma I., Masliah E., Hersh L. B. Neprilysin regulates amyloid beta peptide levels. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004;22:5–11. doi: 10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr R. A., Rockenstein E., Mukherjee A., Kindy M. S., Hersh L. B., Gage F. H., Verma I. M., Masliah E. Neprilysin gene transfer reduces human amyloid pathology in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:1992–1996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-01992.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauro M. J., O'Dwyer M., Heinrich M. C., Druker B. J. STI 571, a paradigm of new agents for cancer therapeutics. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:325–334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehlmann T., et al. Presenilin-1 mutations of leucine 166 equally affect the generation of the Notch and APP intracellular domains independent of their effect on Abeta 42 production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:8025–8030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112686799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller T., Concannon C. G., Ward M. W., Walsh C. M., Tirniceriu A. L., Tribl F., Kogel D., Prehn J. H., Egensperger R. Modulation of gene expression and cytoskeletal dynamics by the amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD) Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:201–210. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya T., Suzuki T. Role of APP phosphorylation in FE65-dependent gene transactivation mediated by AICD. Genes Cells. 2006;11:633–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzer W. J., Dou F., Cai D., Veach D., Jean S., Li Y., Bornmann W. G., Clarkson B., Xu H., Greengard P. Gleevec inhibits beta-amyloid production but not Notch cleavage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12444–12449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534745100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardossi-Piquard R., Dunys J., Kawarai T., Sunyach C., Alves da Costa C., Vincent B., Sevalle J., Pimplikar S., St George-Hyslop P., Checler F. Response to Correspondence: Pardossi-Piquard et al., “Presenilin-dependent transcriptional control of the Abeta-degrading enzyme neprilysin by intracellular domains of betaAPP and APLP”. Neuron. 2007;46:541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.024. Neuron 53, 483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardossi-Piquard R., Dunys J., Yu G., St George-Hyslop P., Alves da Costa C., Checler F. Neprilysin activity and expression are controlled by nicastrin. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:1052–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardossi-Piquard R., et al. Presenilin-dependent transcriptional control of the Abeta-degrading enzyme neprilysin by intracellular domains of betaAPP and APLP. Neuron. 2005;46:541–554. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W., Horgan G. W., Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e36. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnix I., Musunuru U., Tun H., Sridharan A., Golde T., Eckman C., Ziani-Cherif C., Onstead L., Sambamurti K. A novel gamma-secretase assay based on detection of the putative C-terminal fragment-gamma of amyloid beta protein precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:481–487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarati R., Sestan N., Scheinfeld M. H., Berechid B. E., Lopez P. A., Meucci O., McGlade J. C., Rakic P., D'Adamio L. The gamma-secretase-generated intracellular domain of beta-amyloid precursor protein binds Numb and inhibits Notch signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:7102–7107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102192599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo C., Dolcini V., Salis S., Venezia V., Violani E., Carlo P., Zambrano N., Russo T., Schettini G. Signal transduction through tyrosine-phosphorylated carboxy-terminal fragments of APP via an enhanced interaction with Shc/Grb2 adaptor proteins in reactive astrocytes of Alzheimer's disease brain. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2002;973:323–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K. A., Pimplikar S. W. Activation of GSK-3 and phosphorylation of CRMP2 in transgenic mice expressing APP intracellular domain. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:327–335. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schagger H., von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheinfeld M. H., Roncarati R., Vito P., Lopez P. A., Abdallah M., D'Adamio L. Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) interacting protein 1 (JIP1) binds the cytoplasmic domain of the Alzheimer's beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:3767–3775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108357200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter E. H., Kisslinger J. A., Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searfoss G. H., Jordan W. H., Calligaro D. O., Galbreath E. J., Schirtzinger L. M., Berridge B. R., Gao H., Higgins M. A., May P. C., Ryan T. P. Adipsin, a biomarker of gastrointestinal toxicity mediated by a functional gamma-secretase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:46107–46116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. Alzheimer's disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearman M. S., Beher D., Clarke E. E., Lewis H. D., Harrison T., Hunt P., Nadin A., Smith A. L., Stevenson G., Castro J. L. L-685,458, an aspartyl protease transition state mimic, is a potent inhibitor of amyloid beta-protein precursor gamma-secretase activity. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8698–8704. doi: 10.1021/bi0005456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H., Capell A., Pesold B., Citron M., Kloetzel P. M., Selkoe D. J., Romig H., Mendla K., Haass C. Expression of Alzheimer's disease-associated presenilin-1 is controlled by proteolytic degradation and complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32322–32331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Oishi M., Marshak D. R., Czernik A. J., Nairn A. C., Greengard P. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the phosphorylation and metabolism of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:1114–1122. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr P. E., Contursi C., Roncarati R., Noviello C., Ghersi E., Scheinfeld M. H., Zambrano N., Russo T., D'Adamio L. Evidence for a role of the nerve growth factor receptor TrkA in tyrosine phosphorylation and processing of beta-APP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002a;295:324–329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr P. E., Roncarati R., Pelicci G., Pelicci P. G., D'Adamio L. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the beta-amyloid precursor protein cytoplasmic tail promotes interaction with Shc. J. Biol. Chem. 2002b;277:16798–16804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taru H., Suzuki T. Facilitation of stress-induced phosphorylation of beta-amyloid precursor protein family members by X11-like/Mint2 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21628–21636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A. J., Fisk L., Nalivaeva N. N. Targeting amyloid-degrading enzymes as therapeutic strategies in neurodegeneration. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2004;1035:1–20. doi: 10.1196/annals.1332.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingtdeux V., Hamdane M., Begard S., Loyens A., Delacourte A., Beauvillain J. C., Buee L., Marambaud P., Sergeant N. Intracellular pH regulates amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain accumulation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;25:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Rotz R. C., Kohli B. M., Bosset J., Meier M., Suzuki T., Nitsch R. M., Konietzko U. The APP intracellular domain forms nuclear multiprotein complexes and regulates the transcription of its own precursor. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:4435–4448. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E. S., Martinez M., Brunkan A. L., Goate A. Presenilin 2 familial Alzheimer's disease mutations result in partial loss of function and dramatic changes in Abeta 42/40 ratios. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltfang J., Smirnov A., Schnierstein B., Kelemen G., Matthies U., Klafki H. W., Staufenbiel M., Huther G., Ruther E., Kornhuber J. Improved electrophoretic separation and immunoblotting of beta-amyloid (A beta) peptides 1-40, 1-42, and 1-43. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:527–532. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. T., et al. Chronic treatment with the gamma-secretase inhibitor LY-411,575 inhibits beta-amyloid peptide production and alters lymphopoiesis and intestinal cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12876–12882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Liu X. W., Kim H. R. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor-alpha-activated c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-1 is critical for PDGF-induced p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter activity independent of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:49582–49588. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]