Abstract

H8 is derived from a collection of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis bacteriophage. Its morphology and genomic structure closely resemble those of bacteriophage T5 in the family Siphoviridae. H8 infected S. enterica serotypes Enteritidis and Typhimurium and Escherichia coli by initial adsorption to the outer membrane protein FepA. Ferric enterobactin inhibited H8 binding to E. coli FepA (50% inhibition concentration, 98 nM), and other ferric catecholate receptors (Fiu, Cir, and IroN) did not participate in phage adsorption. H8 infection was TonB dependent, but exbB mutations in Salmonella or E. coli did not prevent infection; only exbB tolQ or exbB tolR double mutants were resistant to H8. Experiments with deletion and substitution mutants showed that the receptor-phage interaction first involves residues distributed over the protein's outer surface and then narrows to the same charged (R316) or aromatic (Y260) residues that participate in the binding and transport of ferric enterobactin and colicins B and D. These data rationalize the multifunctionality of FepA: toxic ligands like bacteriocins and phage penetrate the outer membrane by parasitizing residues in FepA that are adapted to the transport of the natural ligand, ferric enterobactin. DNA sequence determinations revealed the complete H8 genome of 104.4 kb. A total of 120 of its 143 predicted open reading frames (ORFS) were homologous to ORFS in T5, at a level of 84% identity and 89% similarity. As in T5, the H8 structural genes clustered on the chromosome according to their function in the phage life cycle. The T5 genome contains a large section of DNA that can be deleted and that is absent in H8: compared to T5, H8 contains a 9,000-bp deletion in the early region of its chromosome, and nine potentially unique gene products. Sequence analyses of the tail proteins of phages in the same family showed that relative to pb5 (Oad) of T5 and Hrs of BF23, the FepA-binding protein (Rbp) of H8 contains unique acidic and aromatic residues. These side chains may promote binding to basic and aromatic residues in FepA that normally function in the adsorption of ferric enterobactin. Furthermore, a predicted H8 tail protein showed extensive identity and similarity to pb2 of T5, suggesting that it also functions in pore formation through the cell envelope. The variable region of this protein contains a potential TonB box, intimating that it participates in the TonB-dependent stage of the phage infection process.

Bacteriophage adsorb to components of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane (OM) during the initial stages of their infectious processes (17, 20, 36, 37, 64, 87, 88, 98). For example, phages Mu (84) and φX174 (41) initially bind to lipopolysaccharide, whereas λ (95), T6 (86), and TLS (30) adsorb to the OM proteins LamB, Tsx, and TolC, respectively. T2 (53) and T4 (92, 102) utilize both lipopolysaccharide and surface proteins in their adsorption reactions. The surface receptor proteins are porins that nonspecifically (70, 71) or specifically (55, 56, 69) transport solutes through the OM. Ligand-gated porins (LGP), which often function in the uptake of metals, show broad multifunctionality by also acting as receptors for bacteriophage, toxins, and antibiotics. One such LGP, FhuA, recognizes the hydroxamate siderophore ferrichrome; phages T1, T5, φ80, and UC-1; colicin M; and the antibiotics albomycin and microcin 25 (11, 13, 43, 51, 82, 93, 101). Subsequent to binding, transport through the OM often requires another cell envelope protein, TonB (34, 97, 101), but different ligand molecules have different requirements for TonB. Among FhuA's ligands, only penetration of T5 is TonB independent (42) for unknown reasons.

Like FhuA, the ferric enterobactin (FeEnt) receptor FepA is multifunctional: it is the cell surface receptor for colicins B and D (15, 44, 101). FhuA (27, 54), FepA (14), and other (structurally solved) TonB-dependent OM receptor proteins (FecA [26], BtuB [18], and FptA [21]) contain a C-terminal trans-OM β-barrel and an N-terminal globular domain lodged within the barrel. Until now viruses were not known to use FepA for entry into the cell, but in this report we describe a new phage, designated H8, that infects Escherichia coli through interactions with FepA. As expected, the binding of H8 to FepA was competitively inhibited by FeEnt. Unlike T5, H8 infection of E. coli was TonB dependent. Analysis of H8 infection of FepA mutants showed that ferric siderophores, bacteriocins, and the bacteriophage may utilize different regions of the receptor protein during binding, but they interact with the same sites and residues of FepA during transport through the OM bilayer. The full nucleotide sequence of the H8 genome (104.4 kb) revealed extensive homology (∼80% identity) to the Siphoviridae bacteriophage T5. These genomic homologies identified the H8 receptor-binding tail protein (Rbp), and its comparison to the T5 and BF23 receptor binding proteins revealed regions that likely interact with the OM proteins FepA, FhuA, and BtuB, respectively. These data support and refine prior predictions of the T5 receptor binding domain in the oad structural gene (63). The analogous portion of the H8 Rbp, from residues 138 to 213, has a net charge of −8, consistent with the experimental evidence that H8 interacts with FepA in a similar way as the acidic siderophore FeEnt.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

E. coli strains were grown in LB (61) medium with or without appropriate antibiotics. RWB18-60 (5) and KDF541 (81) are recA entA fepA derivatives of AB1515 that were isolated by spontaneous resistance to colicin B. GUC12 (32-34), KDF571 (81), and KDO23 are spontaneous tonB isolates that were isolated by resistance to colicins. We also utilized a precise, in-frame chromosomal deletion of the entire fepA (OKN3) and tonB (OKN1) structural genes (58) in E. coli strain BN1071 (46). For the pUC18 derivatives pITS449 (5) and pITS944 (68), ampicillin was added to a concentration of 100 μg/ml. For the pHSG575 (38) derivatives pITS11 and pITS23 (89), chloramphenicol was added to a concentration of 20 μg/ml. In experiments that measured FepA expression, cells were grown in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) minimal medium (66) to mid-log or late log phase.

Isolation of bacteriophage H8.

The phage H8 was isolated from Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in Poland and adapted to the S. enterica serovar Enteritidis propagation strain 64/M for phage typing. The first report of the phage typing system was documented during a phage typing colloquium in Wernigerode, Germany, in 1975 (50), and the scheme was published in 1977 (49). In 1985 the Polish S. enterica serovar Enteritidis phages were analyzed by the Hungarian phage typing scheme (52). We used this latter scheme for serovar Enteritidis during routine phage typing. To establish the type of H8 we screened isogenic S. enterica serovar Enteritidis strains lacking the catecholate receptors FepA, IroN, and Cir. We saw the loss of H8 phage lysis in Salmonella strains carrying fepA::Tn10dTc (WR1425) and in FepA-deficient E. coli strains (H1875 and H1876).

Phage infection assays.

Bacteria were grown in 5 ml of LB broth at 37°C overnight. A phage stock suspension (∼1010 PFU per ml) was serially diluted in LB broth, and 10-μl aliquots were mixed with 50 μl of bacterial culture and incubated for 2 min at room temperature. The infected cell suspension was mixed with molten top agar and plated on LB plates. After incubation at 37°C for 16 h, the phage plaques were counted. For analysis of mutant FepA proteins, susceptibility to H8 was expressed as a percentage of infectivity relative to an isogenic host strain that expressed wild-type FepA. Expression levels for all the mutant FepA proteins, as well as their proper folding and assembly into the OM, were previously determined by quantitative immunoblotting and flow cytometry, respectively, with anti-FepA monoclonal antibodies (4, 16, 68, 89, 90). We verified their expression levels in the phage susceptibility assays, using wild-type FepA expressed from the same plasmid as a positive control (data not shown).

Phage infection competition experiments.

KDF541/pITS449 was grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium plus 100 μg/ml ampicillin. FeEnt was added to 2 × 108 cells in 0.1 ml of LB broth to a concentration of 40 uM, and the suspension was incubated for 2 min at room temperature. A total of 10 μl of phage suspension (106 PFU/ml) was added, the mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 37° and diluted with 1 ml of LB broth, and the cells were pelleted in a microcentrifuge at 14,000 rpm for 1 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of LB broth mixed with 2.5 ml of molten top agar and plated on LB agar. Phage plaques were counted after 16 h at 37°C.

Phage binding competition experiments.

A total of 105 PFU of H8 phage in 0.5 ml of LB medium plus 10 uM CaCl2, either without FeEnt or containing twofold serial dilutions of FeEnt (0.04 to 20 μM), was mixed with 108 cells of OKN3/pITS23 in 0.5 ml of LB medium plus 10 μM CaCl2. The samples were incubated in a 37°C water bath for 40 min and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Aliquots of the supernatant were diluted and plated on a lawn of OKN3/pITS23 to determine the number of unbound PFU.

Western immunoblotting.

Bacteria were grown in LB broth overnight, subcultured (1%) in MOPS medium, and shaken at 37°C for 5.5 h, to mid-log phase. A total of 5 × 107 cells were suspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer and boiled for 5 min, and the proteins in the lysate were resolved on polyacrylamide slab gels (3). The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and incubated for 1 h with anti-FepA monoclonal antibody 45 (65), diluted 0.1% in 5% skim milk. The nitrocellulose was washed five times with tap water and incubated with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-alkaline phosphatase (0.1%; Sigma-Aldrich) in 5% skim milk for 1 h. The membranes were washed five times with tap water and developed with nitroblue tetrazolium and bromochloroindolyl phosphate (65).

Preparation of bacteriophage H8 DNA.

One plaque of phage H8 grown on strain KDF541/pITS449 was picked with a sterile toothpick and resuspended in 500 μl of LB both. One hundred microliters of the phage suspension was diluted to 1 ml with 0.01 M MgCl2-0.01 M CaCl2 and used to inoculate 2 × 108 cells of KDF541/pITS449 in 50 μl of LB broth. After 15 min at 37°C, the suspension was diluted to 50 ml with LB broth and shaken overnight at 37°. The resulting lysate was clarified by centrifugation in sterile 30-ml Corex tubes for 20 min at 3,000 rpm. The supernatant was centrifuged for 1 h at 45,000 rpm in a 70 Ti rotor. The phage pellet was resuspended in 180 μl of 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and chilled on ice. After two phenol extractions and a chloroform extraction, the DNA was precipitated with two volumes of ice-cold ethanol and resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-Cl-1 mM EDTA, pH 8.

Genomic sequencing.

The detailed procedures for random shotgun cloning, fluorescent-based DNA sequencing, and subsequent analysis were previously described (6, 19, 77, 78). Fifty-microgram portions of purified phage DNA were randomly sheared and made blunt ended (6, 77, 83). After kinase treatment and gel purification, fragments in the 1- to 3-kb range were ligated into SmaI-cut bacterial alkaline phosphatase-treated pUC18 (Pharmacia), and the ligation mixture was transformed by electroporation into E. coli strain XL1 Blue MRF′ (Stratagene). A random library of approximately 1,200 colonies was picked from each transformation and grown in Terrific broth (83) supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin for 14 h at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. The cells were harvested, and their plasmids were isolated by a cleared lysate-based protocol (6).

Sequencing reactions (19, 77) were performed using the Amersham ET terminator sequencing reaction mixes. The reactions were incubated for 60 cycles in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA Thermocycler 9600 under the cycle conditions recommended by the manufacturer. Any unincorporated dye terminators were removed by ethanol precipitation at room temperature, and after the fluorescent-labeled nested fragment sets in double-distilled water were dissolved, they were resolved by electrophoresis on an ABI 3700 Capillary DNA Sequencer. After base calling with the ABI analysis software, the analyzed data were transferred to a Sun workstation cluster and assembled using Phred and Phrap (24, 25). Overlapping sequences and contigs were analyzed using Consed (31). Gap closure and proofreading were performed using either custom primer walking or using PCR amplification of the region corresponding to the gap in the sequence, followed by sequencing directly using the amplification or nested primers or by subcloning into pUC18 and cycle sequencing with the universal pUC primers (6, 19, 77, 78). In some instances, additional synthetic custom primers were necessary to obtain at least threefold coverage for each base. The mean factor of coverage over the genome was 15. The resulting phage sequence was analyzed on Sun workstations using Artemis (79).

We discovered putative novel genes by first using Artemis to call open reading frames (ORFs) greater than 100 bp in the ordered and oriented single H8 contig. We then removed ORFs that overlapped annotated genes that were previously identified by BLASTp (2) analysis against T5 and those that overlapped gaps in the assembly. We next used the BLAST algorithm to compare the remaining sequences against the GenBank database (E value of 10−6), seeking relationships to known genes. Genes without homology were classified as putative novel genes. We then ran the entire assembly through the ab initio FgenesV and GenemarkS programs, and both of these programs identified nine genes. Analysis of these putative novel genes by PSORT and TMHMM resulted in their predicted cellular localization.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of phage H8 was deposited into GenBank database under accession number AC171169.

RESULTS

Morphology of bacteriophage H8.

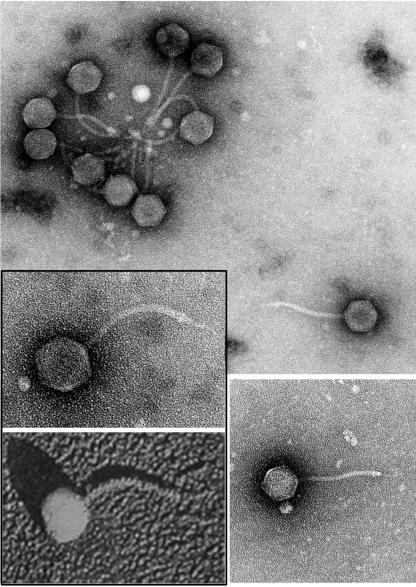

H8 was isolated from a collection of serovar Enteritidis bacteriophages that originated in Poland in 1975. The virus was selected for its ability to infect fepA+ but not fepA strains of serovar Enteritidis and E. coli (Tables 1 and 2). Electron microscopic depictions showed an icosahedral head and long tail with fibers that closely resembled the morphology of bacteriophage T5 (Fig. 1). Both H8 and T5 tail assemblies contain an elongated, pointed spike, presumably comprised by their pore-forming tail proteins.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibility of Salmonella and E. coli strains to infection by H8

| Strain | Characteristic(s) | Lysis at indicated titera

|

Reference or source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1010 | 105 | |||

| S. enterica Typhimurium WR 1244 strains | fepA+iroN cir | CL | CL | 75 |

| WR 1334 | fepA iroN+cir | − | − | 75 |

| WR 1332 | fepA iroN cir+ | − | − | 75 |

| WR 1330 | fepA iroN cir | − | − | 75 |

| LT2 Enb7 | ent | CL | CL | 57 |

| LT2 TA2700 | ent fhuC | CL | CL | 74 |

| WR1893 | ent DE(exbB)::Km | CL | CL | This study |

| A SR1001 | ent tonB | − | − | 74 |

| S. enterica serovar Enteritidis 147 strains | Nalr | CL | CL | 60 |

| WR1425 | 147 fepA::Tn10dTc | − | − | 75 |

| WR1529 | 147 tonB::MudJ | − | − | 75 |

| WR1530 | 147 cir::MudJ | CL | CL | 75 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhi Ty2 strains | CL | CL | 103 | |

| WR1873 | Ty2 DE(fepA)::Km | − | − | This study |

| WR1856 | Ty2 DE(iroN)::Cm | CL | CL | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||||

| BN1071 | fiu+fepA+cir+ | CL | CL | 46 |

| RWB18 | fiu+fepA cir+ | − | − | 100 |

| OKN3 | fiu+ ΔfepA cir+ | − | − | 58 |

| H1728 | fiu fepA+cir | CL | CL | 35 |

| H1875 | fiu+fepA cir | − | − | 35 |

| H1876 | fiu fepA cir | − | − | 35 |

| HE1 | exbB::Tn10 | CL | CL | 10 |

| TPS13 | tolQ | CL | CL | 94 |

| HE2 | TPS13 exbB::Tn10 | − | − | 10 |

| HE10 | tolR::Cm exbB::Tn10 | − | − | 12 |

The bacteria were grown in LB broth and plated on LB agar, and a drop of phage suspension at a titer of 1010 or 105 PFU/ml was deposited on the surface of the agar. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and scored for lysis. CL, confluent lysis; −, no lysis.

TABLE 2.

Host range of bacteriophage H8

| Host range |

|---|

| H8-positive organisms |

| S. enterica serotype Typhi |

| S. enterica serotype Paratyphi B |

| S. enterica serotype Abortusequi |

| S. enterica serotype Abortusovis |

| S. enterica serotype Sendai |

| S. enterica serotype Enteritidis LT2 |

| S. enterica serotype Enteritidis |

| S. enterica serotype Reading |

| S. enterica serotype Miami |

| S. enterica serotype Gallinarum LB5010 (S. enterica serotype Typhimurium galE) |

| Shigella sonnei (10 strains) |

| Citrobacter freundii |

| Citrobacter diversus |

| Serratia marcescens |

| Serratia liquefaciens |

| E. coli K12 |

| Escherichia blattae |

| H8-negative organisms |

| Proteus rettgeri |

| Proteus mirabilis |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Klebsiella terrigena |

| Klebsiella ozeanae |

| Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis |

| Enterobacter cloacae |

| Enterobacter agglomerans |

| Enterobacter taylorae |

| Morganella morganii |

| Shigella boydii |

| Yersinia enterocolitica |

| Serratia fonticula |

| Serratia rubidae |

| Serratia odifera |

| Escherichia hermanii |

| Escherichia vulneris |

| E. coli Nissle 1917 (probiotic strain) |

FIG. 1.

Bacteriophage H8 morphology. H8 particles were observed by transmission electron microscopy at a magnification of 100,000. The inset at the bottom left shows T5, observed by metal-shadowed transmission electron microscopy at magnification 93,150. (Reprinted from reference 1 with permission of the publisher).

FepA specificity and TonB dependence of bacteriophage H8.

H8 infected only E. coli strains carrying a functional fepA allele (Table 1). Strains with a defective fepA structural gene, like the S. enterica strains W1334 and WR1425, the spontaneous colicin B-resistant E. coli strain RWB18, and the genetically engineered E. coli strain OKN3 (containing a precise, in-frame deletion of fepA) were completely resistant to infection by H8 and did not produce plaques when exposed to the phage. The host range of bacteriophage H8 included several gram-negative bacterial species (Table 2). Besides Escherichia and Salmonella, the virus infected Shigella, Citrobacter, and Serratia in liquid or solid LB medium (Tables 1 and 2). On the other hand, with the exception of the Salmonella, we also identified strains of these same genera that were H8 resistant. Furthermore, H8 failed to propagate on all the strains of Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Morganella, Proteus, and Yersinia that we tested.

Experiments with plasmids also demonstrated the FepA specificity of H8. In the E. coli fepA strains KDF541, RWB18-60, or OKN3, plasmid-encoded expression of FepA restored H8 plaque-forming ability to equivalent or higher levels than those conferred by strain BN1071, which expresses wild-type FepA from its chromosome (Table 1). E. coli also produces other ferric catecholate receptors, including Fiu, IroN, and Cir. No bacteriophages are known to utilize these OM proteins, nor do they play a role in H8 penetration (Table 1). Because of its close relationship to bacteriophage T5 (see following), we evaluated the possibility that H8 infection might take place through FhuA. But the presence or absence of FhuA had no impact on the susceptibility of cells to H8 infection. The genetically engineered strain OKN73, which contains precise deletions of both fhuA and fepA, did not acquire sensitivity to H8 when transformed with a plasmid that expressed wild-type FhuA (pITS11 [89]). It did, however, become sensitive to H8 when it harbored the fepA+ plasmid pITS23 (data not shown).

H8 infection was TonB dependent. E. coli strains GUC12, KDO23, and OKN1 are fepA+ tonB derivatives of C600 and BN1071; all three were unable to propagate the phage (Table 3). Likewise, we saw the TonB dependency of H8 in S. enterica (SR1001) and serovar Enteritidis (WR1529). As is the case for TonB, although their exact physiological functions are unknown, the products of the exbB and exbD loci are needed for normal function of TonB-dependent OM transport systems (9, 29). In addition, the ExbB and ExbD proteins bear structural similarity to, and are functionally interchangeable with, TolQ and TolR (10). Our experiments reiterated this interchangeability with regard to infection by H8: the exbB mutation alone in S. enterica WR1893 and E. coli HE1 did not cause phage resistance. But as seen before for other ligands (10), exbB and tolQR were ostensibly interchangeable with respect to H8 infection. That is, only the exbB tolQ and exbB tolR double mutants (E. coli strains HE2 and HE10) were resistant to H8.

TABLE 3.

Effect of deletions in FepA on infection by H8a

| Strainb or allelec,d | Susceptibility to H8 (%)e | Activity with FeEntf

|

Susceptibility to ColB killing (%)g | Reference or source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | Km (μM) | Halo diam (mm) | ||||

| KDF541 (fepA) | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 81 |

| GUC12 (tonB) | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 33 |

| KDO23 (tonB) | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 90 |

| OKN1 (tonB) | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 58 |

| fepA+b,c | 100 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 18 | 100 | 5 |

| fepA+b,d | 100 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 19 | 100 | 89 |

| fepA+b,d,h (+FeEnt) | 9 (2) | NA | NA | NA | ND | This study |

| Class I strains (resistant) | ||||||

| fhuAb,dfhuAΔ1-160 | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 89 |

| fepAb,dfepAΔ1-150 | R | 0.6 | 1.5 | 20 | 0.4 | 89 |

| fepAb,dfepN fhuβ | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 89 |

| fepAb,dfhuN fepβ | R | 0.2 | 1.7 | 25 | 0.01 | 89 |

| fepAb,c ΔL2 (199-206) | R | 1453 | 8912 | 11 | 0.3 | 62 |

| fepAb,c ΔL4 (315-326) | R | 651 | 1092 | 28 | 100 | 62 |

| fepAb,c ΔL7 (467-497) | R | NB | NT | 0 | R | 62 |

| fepAb,c ΔL9 (592-603) | R | 6 | 354 | 25 | 3 | 62 |

| fepAb,c ΔL11 (681-708) | R | 236 | 3360 | 22 | 10 | 62 |

| Class II strains (<15% susceptibility) | ||||||

| fepAb,c ΔL5 (383-401) | 7 (1) | 251 | 964 | 25 | 0.6 | 62 |

| fepAb,c ΔL8 (546-560) | 7 (5) | NB | NS | 12 | R | 62 |

| fepAb,c ΔL10 (630-654) | 4 (7) | 945 | 446 | 23 | 0.5 | 62 |

| Class III strains (16 to 50% susceptibility) | ||||||

| fepAb,d ΔNL1 (60-67) | 28 (8) | 7 | 119 | 25 | 10 | 4 |

| fepAb,d ΔNL2 (98-105) | 24 (11) | 12 | 163 | 25 | 10 | 4 |

| fepAb,c ΔL3 (269-280) | 38 (23) | 22 | 930 | 26 | 100 | 68 |

fepA or tonB strains of E. coli, harboring plasmids that carry fepA alleles, were tested for susceptibility to H8 infection on LB agar. Class designations are based on the percentage of wild-type susceptibility to H8 infection (see Materials and Methods).

Host strain KDF541 (F− pro leu trp thi entA fepA fhuA cir) (81).

Plasmid pITS449 (5), a pUC18 derivative carrying fepA+ or its mutant derivatives under Fur-mediated regulation.

Plasmid pHSG575 (38), a pSC01 derivative carrying fepA+ or its mutant derivatives under Fur-mediated regulation.

Susceptibility to H8 infection was determined by counting the plaques formed on bacteria carrying fepA+ or mutant fepA alleles on plasmids. The results are shown as a percentage of wild-type activity. Parenthetic values show the standard deviation of three separate trials. R, resistant.

The interaction of FepA with FeEnt was evaluated by the affinity of the binding (Kd) or transport (Km) reactions and by the diameter (mm) of growth halos observed in siderophore nutrition tests (100). NA, not applicable; NB, no binding; NT, no transport; NS, nonsaturable transport.

Susceptibility to killing by colicin B was determined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of a preparation of the toxin that gave visible clearing of the agar on an LB plate spread with the test bacteria (68). The results are shown as a percentage of wild-type activity. R, resistant; ND, no data.

The bacteria were incubated with 10 μM FeEnt, exposed to the diluted phage or colicin lysate, incubated for 20 min at room temperature, pelleted by centrifugation, and plated on LB agar.

Effect of FepA expression levels and the presence of FeEnt.

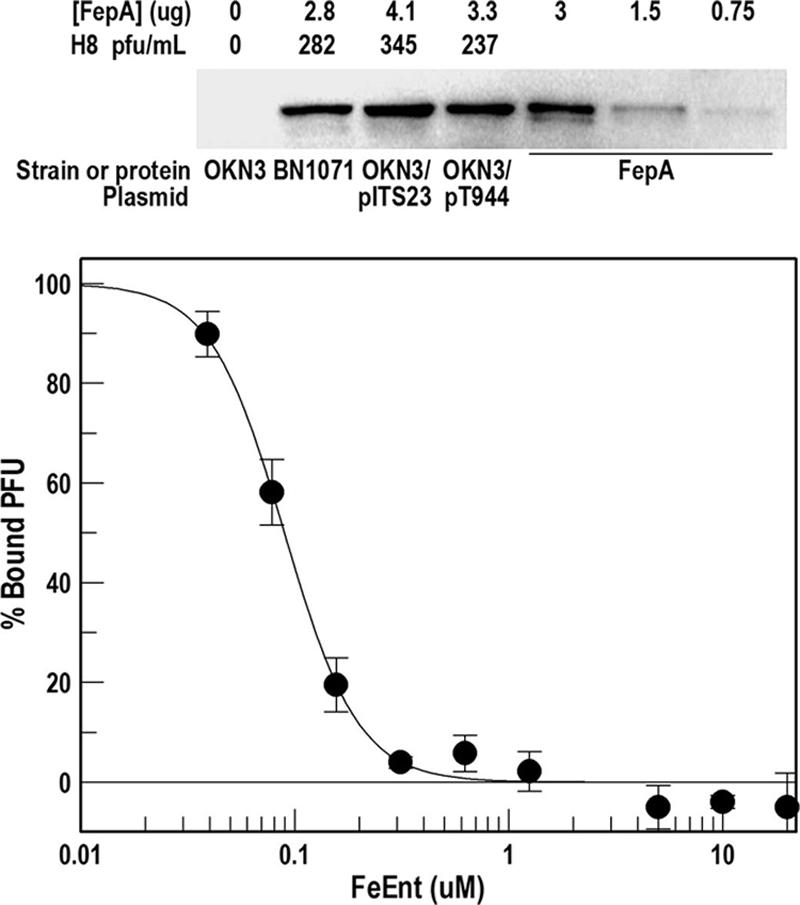

The titer of H8 lysates varied with the concentration of FepA in the E. coli OM (Fig. 2). The number of PFU on each host strain fluctuated with the FepA expression level. The same phage lysate gave the most PFU when FepA was expressed from the low-copy-number vector pITS23 (derived from pHSG575; 3 to 5 copies per cell) (38, 96); fewer plaques resulted when FepA originated from a single chromosomal copy (BN1071) (46). Relative to BN1071, FepA expression increased 1.5-fold in OKN3/pITS23, and the number of H8 PFU was 1.2-fold higher on the latter strain. We also tested H8 plating efficiency on bacteria expressing FepA from the high-copy-number vectors pITS449 and pT944 (pUC18 derivatives) (68). Because these constructs contain a truncated promoter region (5), they produce less FepA than OKN3/pITS23, which has a native, full promoter (89). H8 plating efficiency was lowest on these strains, probably as a result of physiological differences caused by the higher plasmid load (see Discussion).

FIG. 2.

(Top) H8 susceptibility and FepA expression level. BN1071 expresses FepA from its wild-type chromosomal structural gene. The fepA strain OKN3 was transformed with pITS23 or pT944, both of which carry fepA+ alleles and produce different amounts of wild-type FepA in the OM. The bacteria were grown in MOPS medium to late log phase, and lysates from 5 ×107 cells were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western immunoblotting with ant-FepA monoclonal antibody 45 (65) and 125I-labeled protein A. The intensities of the FepA bands in the four strains were determined by image analysis on a Storm Scanner (Molecular Dynamics) and related to those produced by a set of standards with purified FepA. The same bacteria were plated on LB agar, and the number of PFU was determined. The experiment was repeated three times; the mean standard deviation of the PFU determinations was 10.6%. (Bottom) Inhibition of H8 binding by FeEnt. E. coli strain OKN3/pITS23 was grown in LB broth and exposed to H8 (105 PFU) in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of FeEnt. After 45 min at 37°C, the mixtures were centrifuged, and the number of phage in the supernatant (PFUFREE) was determined by serial dilution and plaque assays. PFUBOUND was calculated as PFUTOTAL − PFUFREE, and percent bound in the presence of FeEnt was calculated as PFUBOUND (+FeEnt)/ PFUBOUND (−FeEnt) × 100. Data were analyzed by the IC50 algorithm of Grafit 5.013 (Erithacus Ltd., Surrey, United Kingdom), which yielded an IC50 value of 0.098 μM for FeEnt.

We compared the susceptibility of E. coli to H8 in the absence and presence the presumably competitive ligand FeEnt. Preincubation of E. coli OKN3/pITS23 with FeEnt (10 uM) reduced the plating efficiency of phage H8 to 9% of its value in the absence of the ferric siderophore (Table 3), suggesting that the phage shares common binding sites with FeEnt on FepA. Bacteriophage adsorption assays in the presence of FeEnt verified this supposition: increasing concentrations of the ferric siderophore strongly inhibited the binding of H8, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 98 nM and complete inhibition above 300 nM (Fig. 2).

H8 susceptibility of bacteria expressing FepA-FhuA chimeras and FepA loop deletion mutants.

Both the N and C domains of FepA are necessary for H8 infection. H8 was unable to infect strains expressing FepA mutant proteins without the N-terminal globular domain (a deletion of residues 1 to 150 [Δ1-150]) (89) even at a high multiplicity of infection (Table 3). Nor did the production of hybrid receptor proteins that exchanged the N domain of FepA into the C domain of FhuA, or vice versa (89), confer phage sensitivity.

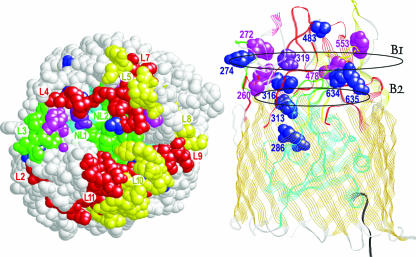

FepA contains 11 external loops linking the 22 strands of its β-barrel, and two loops that originate from the N domain. H8 infectivity was strongly impaired by deletions (68) that eliminated or affected these loops (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Susceptibility conferred by the deletion alleles fell into three categories: I, no infectivity and complete resistance to H8 infection (deletions of loops L2, L4, L7, L9, and L11, yielding ΔL2, ΔL4, ΔL9 and ΔL11 mutants); II, less than 15% of wild-type susceptibility (ΔL5, ΔL8, and ΔL10); III, 16 to 50% of wild-type susceptibility (ΔNL1, ΔNL2, and ΔL3). Among the ferric siderophore, bacteriocins, and bacteriophage, the FepA loop deletions most significantly impaired interactions with the phage. All 11 loop deletions affected the interaction of FepA with H8, and five of them rendered the bacteria fully resistant to infection. Loop deletion mutations may cause unexpected, potentially global changes in OM protein structure, and as a result we cautiously interpret their negative phenotypes with regard to H8. However, it is relevant in this sense that the loop deletion mutants are generally functional, albeit at reduced levels, in the transport of FeEnt and susceptibility to colicins B and D. Furthermore, with regard to H8, the loop deletions fell into different categories than those previously observed for FeEnt or the colicins (68). For instance, several of the mutants that were completely resistant to phage infection (ΔL2, ΔL4, ΔL9, and ΔL11) transported FeEnt and were susceptible to killing by both colicins. Only the ΔL7 mutant rendered FepA nonfunctional for all four of the ligands. Elimination of either N domain loop (ΔNL1 or ΔNL2 mutant) had a lesser effect on H8 infection than surface loop deletions, suggesting a secondary role in H8 adsorption.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of FepA mutants. (Left) The space-filling model shows a view looking down onto the surface of the protein from the exterior. The N-terminal domain is colored cyan, and the TonB box region is black. Other colored regions or residues indicate sites that affected H8 infection. Residues removed by class I loop deletions (ΔL4, ΔL7, ΔL9, and ΔL11), class II (ΔL5, ΔL8, and Δ10), and class III (ΔNL1, ΔNL2, and ΔL3) are colored red, yellow, and green, respectively. Site-directed Ala substitution mutations for individual basic, aromatic, and acidic residues are colored blue, magenta, and purple, respectively. (Right) In the ribbon model the protein was rotated −90° along its x axis to show the location of individual substitution mutations within the loops. The figure also depicts the B1 and B2 regions of the FepA surface vestibule, which participate in the initial and secondary stages of ligand binding (16). The bacteriophage utilizes sites that are broadly distributed across the outer, B1, region of the receptor protein, but single substitutions in the inner, B2, region also impair H8 infection, as well as FeEnt transport and colicin B/D killing.

Effect of Ala substitution mutations on phage infectivity.

FepA is adapted to the chemical determinants of FeEnt, resulting in subnanomolar affinity of the ligand-binding equilibrium The anionic, catecholate iron complex associates with basic and aromatic amino acids in the receptor protein that were previously categorized with regard to their position in its vestibule and temporal priority in the binding process (4, 16, 67).

We surveyed a collection of 50 Ala single, double, and triple substitution mutations in these regions of FepA to determine their impact on H8 infectivity. Some were originally generated and analyzed on pUC plasmids carrying the fepA structural gene (pITS449 and pT944; both plasmids express wild-type FepA, but the latter is genetically engineered to introduce convenient restriction sites) (16, 67). More recent constructions were made on the low-copy-number plasmid pHSG575 (4, 89, 90). Because we did not desire to reclone all the mutants into the low-copy-number vector, we instead related H8 susceptibility to appropriate negative (RWB18-60 or KDF541) and positive (e.g., RWB18-60 or KDF541/pITS449 for pUC clones; RWB18-60 or KDF541/pITS23 for pHSG575 clones) controls and report H8 susceptibility of the mutants as a percentage of wild-type activity.

Like the effects of loop deletions, the effects of Ala substitutions on H8 susceptibility roughly fell into similar categories. However, the effects of substitution mutations on OM protein function were less severe than those of deletions, necessitating the addition of another category, IV, with <51 to 80% of wild-type susceptibility. Among 16 substitution mutations for aromatic amino acids in the loop extremities, only three produced significant reductions in phage infection efficiency (F329A, Y478A, and Y553A) (Table 4). Similarly, among 15 substitutions of Ala for Lys in the loop extremities, only two (K328A and K483A) reduced the efficiency of H8 infection, in both cases to a level that was about 10% of wild-type FepA. On the other hand, deeper within the receptor's vestibule, residues that participate in binding and/or transport of the ferric siderophore and colicins were also essential to productive interactions with the phage. Two arginines (R286 and R316) participate in the binding and transport of FeEnt (67), and these same residues were also critical to phage infection (Table 4). Likewise, an Ala substitution for Y260, deep within the B2 region, reinforced the finding that the ferric siderophore, colicins, and phage utilize common determinants in this region of the receptor protein: Y260A reduced FeEnt transport affinity 100-fold; colicin B killing, 10-fold; and H8 infectivity, 50-fold. To summarize these data, the elimination of aromatic or basic amino acids in the outermost (B1) regions of FepA, which function in the initial adsorption of FeEnt, was generally less detrimental to phage infection than the alteration of residues deep within the vestibule (B2 region), which are thought to participate in the attainment of binding equilibrium, prior to ligand uptake (Fig. 3).

TABLE 4.

Effect of Ala substitutions in FepA on infection by H8a

| Host strain and/or fepA allele and substitutions | Susceptibility to H8 (%)f | Activity with FeEntg

|

Susceptibility to ColB killingh | Referencei | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (μM) | Km (μM) | Halo diam (mm) | ||||

| RWB18-60 or KDF541 | 0 | NB | NT | 0 | R | 81 |

| fepA+b,d | 100 (7) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 18 | 100 | 67 |

| fepA+c,d | 100 (14) | 0.2 | 0.5 | 19 | 100 | 68 |

| fepA+c,e | 100 (10) | 0.3 | 0.4 | 18 | 100 | 4 |

| Class I strains (resistant; Ala substitutions) | ||||||

| fepA+(R313A R316A)c,e | R | ND | ND | 21 | 20 | 64 |

| fepA+(Y260A F329A)c,e | R | 126 | 367 | 25 | 50 | 64 |

| fepA+(Y260A Y272A)c,e | R | 33 | 128 | 25 | 50 | 64 |

| Class II (<15%; Ala substitutions) | ||||||

| fepA(R286A)b,d | 7 (9) | ND | ND | 22 | 100 | 67 |

| fepA(R286A R316A)b,d | 1 (1) | ND | ND | 17 | 2 | 67 |

| fepA(R316A R274A)b,d | 12 (12) | ND | ND | 20 | 20 | 67 |

| fepA(Y260A)c,d | 2 (1) | 10 | 33 | 23 | 10 | 16 |

| fepA(F329A)c,d | 5 (7) | 0.2 | 5.5 | 19 | 50 | 16 |

| fepA(E319A)c,d | 11 (3) | 0.3 | 9.2 | 22 | 100 | 16 |

| fepA(Y260A Y309A)c,d | 14 (13) | ND | ND | 19 | 1 | 16 |

| fepA(K483A)c,e | 10 (2) | 1.3 | ND | 19 | 10 | 90 |

| fepA(K328A)c,e | 9 (4) | ND | ND | 19 | 100 | 90 |

| Class III (16-50%) | ||||||

| fepA(R316A)b,d | 24 (13) | 0.4 | 16 | 21 | 20 | 16 |

| fepA(R274A)b,d | 48 (53) | ND | ND | 20 | 100 | 16 |

| fepA(R286A R313A)b,d | 17 (9) | ND | ND | 21 | 100 | 64 |

| fepA(R283A R316A)b,d | 38 (19) | ND | ND | 21 | 10 | 64 |

| fepA(R283A R286A)b,d | 37 (24) | ND | ND | 21 | 100 | 64 |

| fepA(Y260A R316A)b,d | 29 (7) | 17 | 133 | 23 | 2.5 | 64 |

| fepA(Y260A Y309A)c,d | 14 (13) | ND | ND | 19 | 1 | 16 |

| fepA(R316A F329A)c,d | 20 (5) | 83 | 486 | 24 | 2.5 | 16 |

| fepA(Y478A)c,e | 39 (14) | 0.8 | 167 | 21 | 10 | 90 |

| Class IV (51-80%) | ||||||

| fepA(R286A R274A)c,e | 63 (32) | ND | ND | 20 | 100 | 64 |

| fepA(K332A)c,e | 69 (3) | ND | ND | 20 | 100 | 90 |

| fepA(K634A)c,e | 68 (14) | ND | ND | 20 | 100 | 90 |

| fepA(K635A)c,e | 65 (36) | ND | ND | 20 | 100 | 90 |

| fepA(Y553A)c,e | 56 (16) | 0.4 | 2 | 21 | 2.5 | 90 |

Interactions with H8, FeEnt, and colicin B were measured as described in the notes to Table 3. Class designations reflect susceptibility to H8 infection as a percentage of fepA+ susceptibility.

Host strain RWB18-60 (F− recA pro leu trp thi entA fepA) (5).

Host strain KDF541.

Plasmid pITS449.

Plasmid pHSG575.

Bacteriophage plating efficiency was determined as described in the footnotes to Table 3. Parenthetic values show the standard deviation of three separate trials. R, resistant.

FeEnt binding (Kd) and transport (Km) were determined as described in the footnotes to Table 3. NB, no binding; NT, no transport; ND, no data.

Susceptibility to colicin B was determined and reported as described in the footnotes to Table 3. R, resistant.

In addition to the tabulated fepA alleles, we tested other Ala substitutions that did not reduce H8 infection: R274, R283, R313, R283/R274, R283/R313, and R274/R313 (67); K375, K406, K467, K481, K503, K535, K560, and K639 (90); Y272, Y285, Y289, W297, and Y309 (16); and Y217, Y472, Y488, Y495, Y540, and Y638 (4).

The H8 genome.

The morphological relationship of the H8 genome to T5 and dependence on FepA and TonB led us to determine the genomic sequence of bacteriophage H8 (NCBI accession number AC171169). The chromosome displayed a close structural and sequence relationship to that of T5, a double-stranded DNA virus in the order Caudovirales and the family Siphoviridae. T5 infection of E. coli through FhuA is TonB independent, whereas two other phage in this group, φ80 and T1, utilize FhuA in a TonB-dependent manner. Two more TonB-independent members of the family, BF23 and λ, penetrate through the OM proteins BtuB and LamB, respectively. All these phages possess long noncontractile tails and isometric or prolate capsids. Electron micrographs of H8 (Fig. 1) were consistent with this morphology. The H8 chromosome contained 104.4 kb, within which we identified 143 ORFs (Table 5), including six loci that encode tRNA (for M, I, T, G, S, and R) in the region between 20 and 25 kb. The majority of the translated proteins from the potential genes were conspicuously homologous to known or predicted proteins of other bacteriophages: predominantly T5, but also BF23 and RB16, in the family Siphoviridae and Felix 01 in Caudovirales. A total of 120 predicted H8 proteins were most closely related to homologs in T5, and overall these were 84.2% identical and 88.7% similar to proteins encoded by the T5 genome (Table 5 and Fig. 4 and 5). We also found nine potentially unique gene products in H8 that originated from ORFs at 1264, 2916, 2913, 32459, 43128, 70336, 96735, 97635, and 103573 bp on the phage chromosome, encoding proteins from 34 to 241 amino acids. The unique genes were analyzed by PSORT, which predicted five cytoplasmic and four inner membrane proteins that ranged from 4 to 27 kDa (Table 6).

TABLE 5.

Summary of ORFs in the H8 chromosomea

| ORF | Start | End | bp | DNA | Ortholog | Phage | Score | P value | % ID/Sim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 630 | 1109 | 478 | − | gi 51512107 gb AAU05306.1 HNH endonuclease | T5 | 55.5 | 7 × 10−7 | 30/46 |

| 2 | 1264 | 1422 | 157 | + | No hits found | ||||

| 3 | 2191 | 2916 | 724 | − | No hits found | ||||

| 4 | 2913 | 3401 | 487 | − | No hits found | ||||

| 5 | 3401 | 4015 | 613 | − | gi 51511972, gb AAU05171.1; T5p018 | T5 | 365 | 10−100 | 87/93 |

| 6 | 4015 | 4200 | 184 | − | gi 51511973, gb AAU05172.1; T5p019 | T5 | 59.7 | 4 × 10−08 | 96/100 |

| 7 | 4200 | 4433 | 232 | − | gi 45774936, gb AAS77068.1; T5.021 | T5 | 140 | 2 × 10−32 | 94/98 |

| 8 | 4705 | 5253 | 547 | − | gi 59897164, gb AAX11959.1; ORF022 | T5 | 335 | 7 × 10−91 | 98/98 |

| 9 | 5153 | 5356 | 202 | − | gi 51511977, gb AAU05176.1; T5p023 | T5 | 136 | 3 × 10−31 | 94/98 |

| 10 | 5412 | 5783 | 370 | − | gi 45774940, gb AAS77072.1; T5.025 | T5 | 233 | 1 × 10−60 | 96/98 |

| 11 | 5731 | 6192 | 460 | − | gi 51511979, gb AAU05178.1; T5p025 (p024) | T5 | 323 | 2 × 10−87 | 99/99 |

| 12 | 6189 | 6389 | 199 | − | gi 45774942, gb AAS77074.1; T5.027 | T5 | 127 | 1 × 10−28 | 93/96 |

| 13 | 6489 | 6815 | 325 | − | gi 51511981, gb AAU05180.1; T5p027 (p025) | T5 | 201 | 1 × 10−50 | 92/95 |

| 14 | 6805 | 7050 | 244 | − | gi 51511982, gb AAU05181.1; T5p028 (p026) | T5 | 119 | 4 × 10−26 | 75/76 |

| 15 | 7047 | 7328 | 280 | − | gi 51511983, gb AAU05182.1; T5p029 (p027) | T5 | 131 | 9 × 10−30 | 97/100 |

| 16 | 7325 | 7861 | 535 | − | gi 51512058, gb AAU05257.1; T5p118 | T5 | 184 | 2 × 10−45 | 56/64 |

| 17 | 7858 | 8151 | 292 | − | gi 42540978, gb AAS19379.1; protein 2C | T5 | 154 | 8 × 10−37 | 85/87 |

| 18 | 8212 | 8643 | 430 | − | gi 51511986, gb AAU05185.1; T5p032 (p029) | T5 | 295 | 3 × 10−79 | 98/99 |

| 19 | 8811 | 9332 | 520 | − | gi 51511987, gb AAU05186.1; phosphoesterase (p030) | T5 | 348 | 5 × 10−95 | 96/97 |

| 20 | 9333 | 10196 | 862 | − | gi 51511988, gb AAU05187.1; Ser/Thr protein phosphatase (p031) | T5 | 579 | 10−164 | 94/96 |

| 21 | 10199 | 10444 | 244 | − | gi 51511989, gb AAU05188.1; T5p035 (p032) | T5 | 142 | 4 × 10−33 | 86/95 |

| 22 | 10542 | 10832 | 289 | − | gi 51511990, gb AAU05189.1; thioredoxin (p033) | T5 | 198 | 5 × 10−50 | 98/100 |

| 23 | 10825 | 11355 | 529 | − | gi 51512004, gb AAU05203.1; T5p050 | T5 | 191 | 1 × 10−47 | 59/72 |

| 24 | 11352 | 11780 | 427 | − | gi 51511991, gb AAU05190.1; T5p037 (p034) | T5 | 268 | 5 × 10−71 | 97/97 |

| 25 | 12350 | 12763 | 412 | − | gi 51511993, gb AAU05192.1; lysozyme (p036) | T5 | 280 | 1 × 10−74 | 100/100 |

| 26 | 12760 | 13443 | 682 | − | gi 42540987, gb AAS19388.1; holin (p037) | T5 | 427 | 10−118 | 94/97 |

| 27 | 13573 | 14172 | 598 | − | gi 51511995, gb AAU05194.1; Clp protease (p038) | T5 | 405 | 10−112 | 97/98 |

| 28 | 14185 | 14937 | 751 | − | gi 45774958, gb AAS77090.1; deoxynucleoside-5-monophosphate kinase (p039) | T5 | 467 | 10−130 | 97/97 |

| 29 | 14934 | 15284 | 349 | − | gi 51512004, gb AAU05203.1; T5p050 | T5 | 137 | 1 × 10−31 | 63/74 |

| 30 | 15472 | 15825 | 352 | − | gi 51511997, gb AAU05196.1; T5p043 (p040) | T5 | 240 | 1 × 10−62 | 96/97 |

| 31 | 15813 | 16511 | 697 | − | gi 51512090, gb AAU05289.1; T5p150 | T5 | 137 | 3 × 10−31 | 37/56 |

| 32 | 16492 | 16917 | 424 | − | gi 51511998, gb AAU05197.1; T5p044 (p041) | T5 | 229 | 3 × 10−59 | 87/89 |

| 33 | 16917 | 17414 | 496 | − | gi 51511999, gb AAU05198.1; HNH endonuCLease | T5 | 343 | 2 × 10−93 | 98/100 |

| 34 | 17411 | 17638 | 226 | − | gi 51512000, gb AAU05199.1; T5p046 (p043) | T5 | 154 | 1 × 10−36 | 98/100 |

| 35 | 17625 | 17822 | 196 | − | gi 51512000, gb AAU05199.1; T5p046 (p043) | T5 | 127 | 1 × 10−28 | 100/100 |

| 36 | 17848 | 18111 | 262 | − | gi 51512000, gb AAU05199.1; T5p046 (p043) | T5 | 163 | 2 × 10−39 | 97/98 |

| 37 | 18266 | 18610 | 343 | − | gi 51512001, gb AAU05200.1; T5p047 (p044) | T5 | 233 | 2 × 10−60 | 99/100 |

| 38 | 18721 | 19005 | 283 | − | gi 51512002, gb AAU05201.1; T5p048 (p045) | T5 | 100 | 2 × 10−20 | 53/67 |

| 39 | 19002 | 19331 | 328 | − | gi 59897189, gb AAX11984.1; ORF047 | T5 | 217 | 1 × 10−55 | 96/98 |

| 40 | 19312 | 19821 | 508 | − | gi 51512004, gb AAU05203.1; T5p050 (p048) | T5 | 224 | 1 × 10−57 | 66/77 |

| 41 | 19818 | 20150 | 331 | − | gi 51512005, gb AAU05204.1; T5p051 (p049) | T5 | 178 | 7 × 10−44 | 84/95 |

| 42 | 20107 | 20388 | 280 | − | gi 51512006, gb AAU05205.1; T5p052 (p050) | T5 | 177 | 9 × 10−44 | 88/90 |

| 43 | 20465 | 20812 | 346 | − | gi 51512007, gb AAU05206.1; T5p053 (p051) | T5 | 233 | 1 × 10−60 | 87/97 |

| 44 | 20934 | 21110 | 175 | − | gi 38043883, emb CAE53182.1 (p052) | BF23 | 80.1 | 2 × 10−14 | 68/72 |

| 45 | 21330 | 21767 | 436 | − | gi 51512009, gb AAU05208.1 pyruvate formate lyase-related protein | T5 | 238 | 5 × 10−62 | 96/99 |

| 21712 | 21787 | 74 | − | tRNA-Met | |||||

| 21884 | 21960 | 75 | − | tRNA-Ile | |||||

| 46 | 21976 | 22266 | 289 | − | gi 51512010, gb AAU05209.1; T5p056 (p054) | T5 | 191 | 1 × 10−47 | 94/97 |

| 22341 | 22415 | 73 | − | tRNA-Thr | |||||

| 47 | 22426 | 22590 | 163 | − | gi 51512011, gb AAU05210.1; T5p057 | T5 | 103 | 2 × 10−21 | 96/98 |

| 48 | 22583 | 22804 | 220 | − | gi 38043889, emb CAE53188.1 | BF23 | 122 | 6 × 10−27 | 83/83 |

| 22819 | 22893 | 73 | − | tRNA-Gly | |||||

| 22985 | 23073 | 87 | − | tRNA-Ser | |||||

| 49 | 23094 | 23663 | 568 | − | gi 38043904, emb CAE53203.1 | BF23 | 325 | 6 × 10−88 | 90/91 |

| 50 | 23898 | 24845 | 946 | − | gi 38043908, emb CAE53207.1 | BF23 | 512 | 10−144 | 85/85 |

| 24880 | 24954 | 73 | − | tRNA-Arg | |||||

| 51 | 25609 | 26091 | 481 | − | gi 33340367, gb AAQ14718.1; unknown | Felix | 64.7 | 1 × 10−09 | 31/44 |

| 52 | 26135 | 26578 | 442 | − | gi 45774995, gb AAS77127.1; T5.081 (p076) | T5 | 124 | 1 × 10−27 | 47/64 |

| 53 | 26578 | 26748 | 169 | − | gi 51512020, gb AAU05219.1; T5p080 | T5 | 110 | 2 × 10−23 | 100/100 |

| 54 | 26817 | 27266 | 448 | − | gi 51512021, gb AAU05220.1; cell wall hydrolase homolog | T5 | 242 | 3 × 10−63 | 81/83 |

| 55 | 27279 | 28100 | 820 | − | gi 51512022, gb AAU05221.1; T5p082 | T5 | 94.7 | 4 × 10−18 | 50/65 |

| 56 | 28543 | 29181 | 637 | − | gi 45774999, gb AAS77131.1; T5.085 (p080) | T5 | 395 | 10−109 | 99/99 |

| 57 | 29234 | 29416 | 181 | − | gi 51512024, gb AAU05223.1; T5p084 | T5 | 117 | 2 × 10−25 | 98/98 |

| 58 | 29487 | 30188 | 700 | − | gi 51512025, gb AAU05224.1; peptidase (p082) | T5 | 466 | 10−130 | 96/97 |

| 59 | 30217 | 30453 | 235 | − | gi 51512026, gb AAU05225.1; T5p086 (p083) | T5 | 162 | 5 × 10−39 | 96/97 |

| 60 | 30495 | 31010 | 514 | − | gi 51512027, gb AAU05226.1; T5p087 (p084) | T5 | 276 | 3 × 10−73 | 97/97 |

| 61 | 31093 | 31371 | 277 | − | gi 51512028, gb AAU05227.1; T5p088 (p085) | T5 | 185 | 4 × 10−46 | 98/98 |

| 62 | 31448 | 31924 | 475 | − | gi 51512029, gb AAU05228.1; RNase H | T5 | 334 | 6 × 10−91 | 98/99 |

| 63 | 31921 | 32466 | 544 | − | gi 51512004, gb AAU05203.1; T5p050 | T5 | 188 | 8 × 10−47 | 60/69 |

| 64 | 32459 | 32842 | 382 | − | No hits found | ||||

| 65 | 32944 | 33783 | 838 | − | gi 51512030, gb AAU05229.1; thymidylate synthase | T5 | 585 | 10−166 | 98/99 |

| 66 | 33783 | 34316 | 532 | − | gi 51512031, gb AAU05230.1; dihydrofolate reductase | T5 | 353 | 1 × 10−96 | 99/99 |

| 67 | 34313 | 35176 | 862 | − | gi 51512032, gb AAU05231.1; ribonucleotide reductase β subunit | T5 | 576 | 10−163 | 99/99 |

| 68 | 35595 | 36110 | 514 | − | gi 33340367, gb AAQ14718.1; unknown | Felix | 75.5 | 8 × 10−13 | 37/49 |

| 69 | 36083 | 38515 | 2431 | − | gi 45775010, gb AAS77142.1; aerobic ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase, large subunit | T5 | 1514 | 0 | 94/95 |

| 70 | 38555 | 38752 | 196 | − | gi 51512035, gb AAU05234.1; T5p095 | T5 | 127 | 1 × 10−28 | 95/98 |

| 71 | 38754 | 39506 | 751 | − | gi 51512036, gb AAU05235.1; phosphate starvation-inducible protein | T5 | 501 | 10−140 | 100/100 |

| 72 | 39867 | 40670 | 802 | + | gi 51512090, gb AAU05289.1; T5p150 | T5 | 135 | 2 × 10−30 | 33/54 |

| 73 | 40657 | 42483 | 1825 | + | gi 51512037, gb AAU05236.1; anaerobic ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase | T5 | 729 | 0 | 58/74 |

| 74 | 42583 | 42960 | 376 | + | gi 51512038, gb AAU05237.1; T5p098 (p094) | T5 | 162 | 5 × 10−39 | 63/77 |

| 75 | 42902 | 43159 | 256 | + | gi 51512039, gb AAU05238.1; T5p099 (p095) | T5 | 121 | 1 × 10−26 | 92/98 |

| 76 | 43128 | 43349 | 220 | + | No hits found | ||||

| 77 | 43342 | 44166 | 823 | + | gi 51512040, gb AAU05239.1; NAD-dependent protein deacetylases SIR2 family (p096) | T5 | 541 | 10−153 | 95/98 |

| 78 | 44157 | 44339 | 181 | + | gi 51512042, gb AAU05241.1; T5p102 | T5 | 134 | 1 × 10−30 | 98/98 |

| 79 | 44326 | 44832 | 505 | + | gi 51512043, gb AAU05242.1; T5p103 (p097) | T5 | 308 | 5 × 10−83 | 91/92 |

| 80 | 44835 | 45263 | 427 | + | gi 51512044, gb AAU05243.1; T5p104 (p098) | T5 | 289 | 3 × 10−77 | 95/97 |

| 81 | 45273 | 45665 | 391 | + | gi 51512045, gb AAU05244.1; T5p105 (p099) | T5 | 265 | 4 × 10−70 | 94/98 |

| 82 | 45769 | 46257 | 487 | + | gi 66276921, gb AAY44386.1; RB16 HNH(AP2) 1 | RB16 | 63.5 | 3 × 10−09 | 34/47 |

| 83 | 46926 | 49580 | 2653 | + | gi 45775022, gb AAS77154.1; replication origin binding protein | T5 | 1746 | 0 | 98/99 |

| 84 | 49564 | 49815 | 250 | + | gi 51512048, gb AAU05247.1; T5p108 | T5 | 125 | 4 × 10−28 | 77/85 |

| 85 | 49793 | 50251 | 457 | + | gi 33340367, gb AAQ14718.1; unknown | Felix | 91.3 | 1 × 10−17 | 42/59 |

| 86 | 50320 | 51024 | 703 | + | gi 51512049, gb AAU05248.1; T5p109 (p104) | T5 | 471 | 10−131 | 100/100 |

| 87 | 51372 | 51782 | 409 | + | gi 51512051, gb AAU05250.1; T5p111 | T5 | 193 | 2 × 10−48 | 75/75 |

| 88 | 51819 | 51974 | 154 | + | gi 51512052, gb AAU05251.1; T5p112 (p105) | T5 | 106 | 3 × 10−22 | 98/100 |

| 89 | 52167 | 52475 | 307 | + | gi 51512053, gb AAU05252.1; transcriptional (p106) coactivator p15 | T5 | 210 | 1 × 10−53 | 100/100 |

| 90 | 52563 | 53534 | 970 | + | gi 51512054, gb AAU05253.1; NAD-dependent DNA ligase, subunit A | (p107) | T5 | 654 | 099/100 |

| 91 | 53737 | 54516 | 778 | + | gi 51512055, gb AAU05254.1; NAD-dependent DNA ligase subunit B (p108) | T5 | 497 | 10−139 | 96/97 |

| 92 | 54509 | 55276 | 766 | + | gi 51512056, gb AAU05255.1; transcription factor (p109) | T5 | 432 | 10−120 | 95/95 |

| 93 | 55308 | 56831 | 1522 | + | gi 51512057, gb AAU05256.1; replicative DNA helicase (p110) | T5 | 926 | 0 | 94/94 |

| 94 | 56828 | 57361 | 532 | + | gi 51512058, gb AAU05257.1; T5p118 (p111) | T5 | 318 | 8 × 10−86 | 89/90 |

| 95 | 57358 | 58248 | 889 | + | gi 45775035, gb AAS77167.1; DNA replication primase (p112) | T5 | 585 | 10−166 | 97/98 |

| 96 | 58401 | 60878 | 2476 | + | gi 45775036, gb AAS77168.1; DNA polymerase (p113) | T5 | 1607 | 0 | 95/97 |

| 97 | 61081 | 61368 | 286 | + | gi 51512061, gb AAU05260.1; T5p121 (p114) | T5 | 193 | 2 × 10−48 | 97/100 |

| 98 | 61365 | 62711 | 1345 | + | gi 45775038, gb AAS77170.1; ATP_dependent helicase (p115) | T5 | 880 | 0 | 97/98 |

| 99 | 62713 | 63246 | 532 | + | gi 51512058, gb AAU05257.1; T5p118 | T5 | 141 | 1 × 10−32 | 46/58 |

| 100 | 63412 | 63774 | 361 | + | gi 51512063, gb AAU05262.1; T5p123 (p116) | T5 | 177 | 9 × 10−44 | 92/95 |

| 101 | 63767 | 64540 | 772 | + | gi 51512064, gb AAU05263.1; T5p124 (p117) | T5 | 438 | 10−122 | 84/89 |

| 102 | 64580 | 65110 | 529 | + | gi 33340391, gb AAQ14742.1; unknown | Felix | 96.3 | 5 × 10−19 | 33/53 |

| 103 | 65107 | 66084 | 976 | + | gi 51512065, gb AAU05264.1; probable exonuclease subunit 1 (p118) | T5 | 610 | 10−173 | 89/93 |

| 104 | 66065 | 67903 | 1837 | + | gi 51512066, gb AAU05265.1; probable exonuclease subunit 2 (p119) | T5 | 1111 | 0 | 94/95 |

| 105 | 67907 | 68389 | 481 | + | gi 51512067, gb AAU05266.1; T5p127 (p120) | T5 | 337 | 1 × 10−91 | 100/100 |

| 106 | 68389 | 69264 | 874 | + | gi 51512068, gb AAU05267.1; 5′_3′ exonuclease (p121) | T5 | 572 | 10−162 | 96/99 |

| 107 | 69261 | 69707 | 445 | + | gi 51512069, gb AAU05268.1; deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate nucleotidohydrolase (p122) | T5 | 282 | 3 × 10−75 | 93/97 |

| 108 | 70336 | 70713 | 376 | − | No hits found | ||||

| 109 | 70821 | 73088 | 2266 | − | gi 62362246, ref YP_224171.1; gp33(p123) | ES18 | 75.9 | 7 × 10−12 | 27/43 |

| 110 | 73088 | 73510 | 421 | − | gi 51512072, gb AAU05271.1; 15kDa minor tail protein | T5 | 207 | 1 × 10−52 | 71/85 |

| 111 | 73517 | 75574 | 2056 | − | gi 51512073, gb AAU05272.1; tail protein pb4 (p126) | T5 | 1081 | 0 | 75/84 |

| 112 | 75574 | 78423 | 2848 | − | gi 51512074, gb AAU05273.1; tail protein pb3 (p127) | T5 | 1632 | 0 | 82/91 |

| 113 | 78420 | 79034 | 613 | − | gi 51512075, gb AAU05274.1; tail protein pb9 (p128) | T5 | 360 | 3.00E-98 | 82/92 |

| 114 | 79144 | 82824 | 3679 | − | gi 51512076, gb AAU05275.1; pore-forming tail-tip protein pb2 (p129) | T5 | 1395 | 0 | 62/72 |

| 115 | 82908 | 83276 | 367 | − | gi 51512078, gb AAU05277.1; T5p138 (p131) | T5 | 223 | 2 × 10−57 | 89/90 |

| 116 | 83338 | 83742 | 403 | − | gi 51512079, gb AAU05278.1; T5p139 (p132) | T5 | 261 | 5 × 10−69 | 96/99 |

| 117 | 83735 | 84637 | 901 | − | gi 520580, dbj BAA02256.1; minor tail protein gp24 | BF23 | 456 | 10−127 | 71/86 |

| 118 | 84642 | 86048 | 1405 | − | gi 520579, dbj BAA02255.1; major tail protein gp25 | BF23 | 772 | 0 | 82/89 |

| 119 | 86075 | 86560 | 484 | − | gi 51512082, gb AAU05281.1; T5p142 | T5 | 320 | 9 × 10−87 | 97/99 |

| 120 | 86564 | 87331 | 766 | − | gi 51512083, gb AAU05282.1; T5p143 | T5 | 468 | 10−130 | 93/97 |

| 121 | 87331 | 87843 | 511 | − | gi 45775055, gb AAS77187.1; T5.148 | T5 | 338 | 5 × 10−92 | 97/99 |

| 122 | 87903 | 89279 | 1375 | − | gi 51512085, gb AAU05284.1; major head protein pb8 | T5 | 783 | 0 | 90/91 |

| 123 | 89297 | 89929 | 631 | − | gi 51512086, gb AAU05285.1; probable pro-head protease | T5 | 422 | 10−117 | 100/100 |

| 124 | 89933 | 90415 | 481 | − | gi 51512087, gb AAU05286.1; head protein pb10 | T5 | 258 | 7 × 10−68 | 83/85 |

| 125 | 90418 | 91629 | 1210 | − | gi 51512088, gb AAU05287.1; portal protein | T5 | 799 | 0 | 99/99 |

| 126 | 91629 | 92066 | 436 | − | gi 51512089, gb AAU05288.1; T5p149 | T5 | 266 | 2 × 10−70 | 90/90 |

| 127 | 92056 | 92889 | 832 | − | gi 51512090, gb AAU05289.1; T5p150 | T5 | 577 | 10−163 | 100/100 |

| 128 | 92901 | 94217 | 1315 | − | gi 45775062, gb AAS77194.1; terminase, large subunit | T5 | 857 | 0 | 96/97 |

| 129 | 94217 | 94699 | 481 | − | gi 51512092, gb AAU05291.1; probable SciB protein | T5 | 240 | 1 × 10−62 | 77/80 |

| 130 | 94699 | 96612 | 1912 | − | gi 69148225, gb AAZ03642.1; receptor-binding protein (p146) | BF23 | 172 | 3.00E-41 | 27/42 |

| 131 | 96735 | 97061 | 325 | + | No hits found | ||||

| 132 | 97172 | 97519 | 346 | + | gi 51512004, gb AAU05203.1; T5p050 | T5 | 94.4 | 1 × 10−18 | 56/71 |

| 133 | 97635 | 97739 | 103 | + | No hits found | ||||

| 134 | 98148 | 98882 | 733 | − | gi 51511955, gb AAU05154.1; deoxynucleoside-5′-monophosphatase (p152) | T5 | 476 | 10−133 | 9496 |

| 135 | 98963 | 99355 | 391 | − | gi 51512100, gb AAU05299.1; T5p160 | T5 | 233 | 2 × 10−60 | 89/95 |

| 136 | 99377 | 99886 | 508 | − | gi 51512107, gb AAU05306.1; HNH endonuclease | T5 | 181 | 1 × 10−44 | 55/68 |

| 137 | 99957 | 101639 | 1681 | − | gi 51512102, gb AAU05301.1; A1 protein (p155) | T5 | 1012 | 0 | 89/93 |

| 138 | 101722 | 101919 | 196 | − | gi 51512103, gb AAU05302.1; T5p163 (p156) | T5 | 123 | 2 × 10−27 | 92/98 |

| 139 | 102009 | 102425 | 415 | − | gi 1351400, sp P19348 VA23_BPBF2; A2-A3 protein A2-A3 gene product (p157) | T5 | 215 | 4 × 10−55 | 79/88 |

| 140 | 102712 | 102963 | 250 | − | gi 51512105, gb AAU05304.1; T5p165 | T5 | 140 | 2 × 10−32 | 79/92 |

| 141 | 103128 | 103346 | 217 | − | gi 51512106, gb AAU05305.1; T5p166 | T5 | 90.9 | 1 × 10−17 | 68/83 |

| 142 | 103573 | 103677 | 103 | − | No hits found | ||||

| 143 | 103873 | 104103 | 229 | − | gi 51512107, gb AAU05306.1; HNH endonuclease | T5 | 56.2 | 4 × 10−07 | 55/67 |

The tabulated columnar data list the ORFs discovered by Artemis including their start (Start) and end (End) positions, length in base pairs (bp), DNA strand of origin (DNA), most closely related ortholog in the NCBI database (ortholog), the bacteriophage from which it originates (phage), and the relationship between the H8 protein and its closest ortholog, based on overall comparison score (Score), probability value (P value), and percent identity/similarity (% ID/Sim). ORF numbers in boldface indicate ORFs demonstrating sequence homology to known genes at a level less than the 70% cutoff that was set in ACT4. ORF numbers in boldface with underlining indicate ORFs that had no orthologs in the NCBI sequence database (see Table 6 for further information about these predicted proteins).

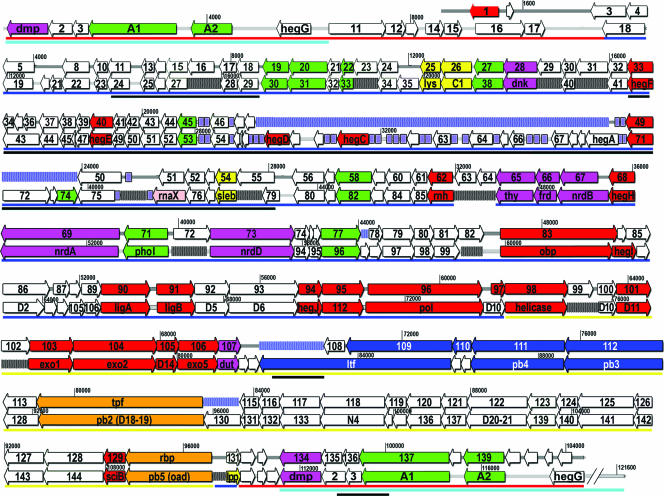

FIG. 4.

Overall comparison of H8 and T5 genomic structure. Alignment of the annotated genomes was made by ACT4 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk). The annotated T5 genomic sequence was obtained from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes), accession number NC005859. Homology between the DNA sequences is displayed as vertical bars of graded color between the genomes of H8 (accession no. AC171169) and T5 from a minimum identity value of 70% (white) to a maximum identity of 100% (red). The figure also depicts the location of genes on the positive (top) or negative (bottom) strands of the bacteriophage chromosomes. For both genomes, ORFs are indicated by colored boxes according to their functional categories as previously described for T5 (99): DNA replication and repair, red; nucleotide metabolism, magenta; host interaction, yellow; other enzymes, green; structural proteins, blue; unknown function, white. The genes encoding the receptor-binding and pore-forming and tail proteins are colored orange.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of ORFs in the H8 and T5 genomes. Alignment of the annotated genomes was performed as described in the legend of Fig. 4. Pre-early, early, and late regions of the T5 genome are marked by red, blue, and yellow underlines, respectively; deletable regions are further underlined with cyan. For both genomes, genes and their transcriptional directions are indicated in colored boxes with arrows indicating the directions of transcription. Genes are colored according to their functional categories using the scheme that was previously described for T5 (99): DNA replication and repair, red; nucleotide metabolism, magenta; host interaction, yellow; other enzymes, green; structural proteins, blue; unknown function, white. ORFs encoding the receptor-binding and pore-forming and tail proteins are colored orange. Gaps in the H8 chromosome relative to that of T5 are shown as blue stippled boxes; gaps in the T5 chromosome relative to that of H8 are shown as black stippled boxes.

TABLE 6.

Unique ORFs in H8a

| ORF | DNA strand | Start position | End position | Length (bp) | No. of aa | PSORT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | + | 1264 | 1422 | 157 | 52 | Cytoplasm |

| 3 | − | 2191 | 2916 | 724 | 241 | IM |

| 4 | − | 2913 | 3401 | 487 | 162 | Cytoplasm |

| 64 | − | 32459 | 32842 | 382 | 127 | Cytoplasm |

| 76 | + | 43128 | 43349 | 220 | 73 | Cytoplasm |

| 108 | − | 70336 | 70713 | 376 | 125 | Cytoplasm |

| 131 | + | 96735 | 97061 | 325 | 108 | IM |

| 133 | + | 97635 | 97739 | 103 | 34 | IM |

| 142 | − | 103573 | 103677 | 103 | 34 | IM |

The noted predicted ORFs do not have orthologs in the NCBI database. Their sequences were analyzed and their localizations were predicted by PSORT. Membrane proteins were further analyzed by TMHMM to confirm the presence of potential membrane-resident domains. aa, amino acids; IM, inner membrane.

Overall, the H8 genome is closely related to that of T5 (Fig. 4 and 5), which is arranged according to its life cycle. We refer the reader to the annotated T5 genome (99), which well agrees with extensive genetic data compiled about the phage over the past 50 years. Two striking features of the T5 chromosome appear again in H8: terminally redundant DNA sequences that facilitate a two-step DNA transfer mechanism and the presence of large tracts of genes that can be deleted (76, 85). We did not characterize the DNA transfer process of H8, but its chromosome contains homologous DNA to the FST genes of T5 that encode proteins and enzymes which facilitate its two-step DNA injection process. Although these appear in the H8 annotation only at the right end of the chromosome, this distribution is probably an artifact of the assembly of the sequencing data. If the H8 chromosome contains identical 6-kb DNA sequences at its extremities, as T5 does, then the shotgun sequencing approach will not differentiate them, and results from these regions will collapse together as one sequence. However, the coverage of shotgun reads from the putative repetitive region was significantly higher than from any other portion of H8 DNA, and the likely explanation is the existence of the same 6-kb sequence at both ends of the H8 chromosome. Thus, our experiments suggest the presence of terminally repetitive DNA at the ends of the H8 chromosome, exactly the same as in the T5 chromosome. Secondly, H8 contains two deletions relative to T5 that span almost 10 kb. These gaps in H8 sequence correspond to deletable portions of the T5 chromosome (23.5 to 42.5 kb) (59, 99) that encode 24 tRNAs and 35 other ORFs, including two HNH-homing endonucleases and another putative endonuclease. The dispensable nature of this region in T5 concurs with its absence in H8. In this sense H8 is analogous to a T5 deletion mutant with a novel host range. Both phages also contain numerous other gaps, relative to each other, that eliminate nonessential genes (Fig. 4 and 5).

In the absence of genetic or physiological data from the newly identified virus and in view of its close relationship to T5, we relied on sequence homologies to bacteriophage proteins as the basis of its genomic annotation (Fig. 5). Among 135 potential proteins encoded in its genome, 49 (36%) were functionally annotated, mainly as enzymes involved in phage DNA replication and repair, nucleotide metabolism, or structural proteins. Despite high overall homology between H8 and T5, their tail proteins, which initiate the infectious process, were noticeably less conserved. The overall level of identity and similarity in the tail protein region of the chromosome was 63% and 74%, respectively, which is less than the level seen in other regions (84% and 89%, respectively). One functionally important tail protein, the H8 homolog of ltf (long tail fiber protein; ORF 109), was 50% truncated relative to that of T5, and the remaining polypeptide was only 24% identical and 29% similar to the corresponding portion of Ltf. Similarly, the putative receptor binding protein of H8 that recognizes and adsorbs to FepA was most like the comparable tail protein of BF23 (27% identical and 42% similar) rather than that of T5. These variations provide a structural explanation for the different host range of bacteriophage H8.

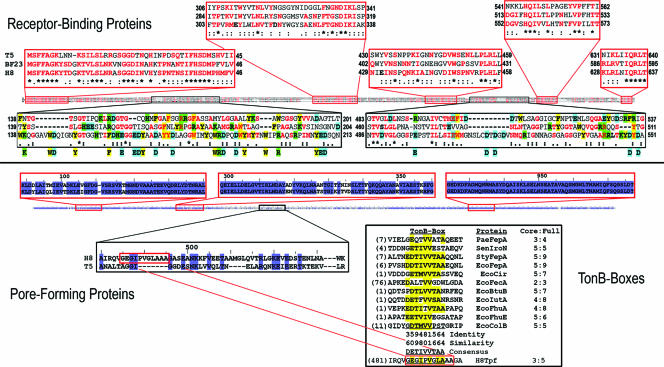

In total, four phage/receptor systems were of most interest to our experiments: H8/FepA, T5, T1/FhuA, and BF23/BtuB. Besides the genome of H8, reported herein, full or partial genomic sequences of other LGP-specific bacteriophage are known, including those of the TonB-dependent phage T1 and the TonB-independent phages T5 and BF23. Sequence data for BF23 is incomplete, but the genes that encode some of its tail proteins are known and sequenced (62, 63). Blast analyses of H8 DNA identified ORFs at 94.7 kb and 82.8 kb that encode homologous proteins to the experimentally demonstrated receptor binding proteins of BF23 (Hrs) (48) and T5 (pb5, encoded by oad) (39, 63) and the pore-forming tail proteins of T5 (pb2) (7, 28), respectively. The receptor binding protein (encoded by rbp) of H8 was one of the least conserved in the genome, relative to its T5 homolog (26% identity; 41% similarity). Sequence comparisons between Rbp, Hrs, and pb5 revealed five regions of local identity and similarity distributed along their length. The most conserved region was at their N termini, where the first 45 residues of the three proteins were 49% identical and 91% similar (Fig. 6); the other four regions had identity and similarity scores of 17% and 81%, 21% and 89%, 33% and 71%, and 50% and 90%, respectively. Besides these conserved regions, we observed two variable regions (Fig. 6) that may function in specific adsorption of the three viruses. In the case of H8, these regions contain a preponderance of acidic residues, and one of them (residues 138 to 213) likely participates in adsorption of the phage tail to basic residues in the receptor protein (see Discussion) (67, 90).

FIG. 6.

Analysis of the putative receptor-binding and pore-forming proteins of bacteriophage H8. (Top) CLUSTAL W alignment of the tail receptor-binding proteins of bacteriophages T5 (protein pb5 or Oad) and BF23 (Hrs) with the putative receptor binding protein (Rbp) of H8 illustrates strong homology in five regions (boxed in red), with identical (marked with a star below) and similar (BLOSUM 62 matrix; marked with a colon or dot below) residues in the sequences colored red. In contrast to these conserved regions, the alignment also shows two variable regions (boxed in black). In the case of H8, a preponderance of acidic residues (cyan; basic residues are highlighted in green) and aromatic residues (highlighted in yellow) exist in the upstream variable domain (H8 residues 138 to 213) that may participate in adsorption to basic residues within FepA (16, 68, 90) (see Discussion). Charged and aromatic amino acids that are unique to H8 are listed below the alignment. (Bottom) The alignment of the tail pore-forming protein of T5 with its H8 homolog (ORF 114, encoded by tpf) reveals strong homology between the two sequences (66% identity; 72% similarity), with conspicuous identities (highlighted in blue) and similarities (light blue) along their lengths. The alignment has most homology near the N and C termini; the relatedness weakens in the central region. The enlarged elements of sequence boxed in red illustrate the three regions of most significant homology among the proteins; the region boxed in black illustrates the greater variability of the central portion. The H8 protein contains the sequence GEGIPVGLA, which bears similarity to the consensus TonB box regions near the N termini of siderophore receptor proteins. FepA contains the TonB box sequence DDTIVVTAA. The tabular comparison of TonB boxes illustrates the variability that occurs in such regions, despite the fact that they all presumably physically interact with the single protein, TonB. The top four proteins, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PaePfeA), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (StyIroN and StyFepA), and E. coli (EcoFepA), are orthologs that transport FeEnt. The next six proteins (EcoCir, EcoFecA, EcoBtuB, EcoIutA, EcoFhuA, and EcoFhuE) are E. coli LGP paralogs. These 10 proteins, as well as relevant regions of colicin B (EcoColB) and H8 Tpf, were aligned by the PILEUP algorithm (GCG, Madison, WI). Residues highlighted in yellow are conserved (either identical or similar; tabulated for each position below the below the alignment) in the consensus TonB box sequence. The column at right lists for each individual protein the number of identical or similar residues to the consensus core (ETIVV) or full (DETIVVTAA) TonB box consensus sequence, respectively.

The tail pore-forming protein of bacteriophage T5, pb2, was identified by in vitro demonstrations of its channel activity (28) and its FhuA-dependent penetration of lipid bilayers (7). We observed a homologous H8 protein that was 66% identical and 72% similar to T5 Pb2. On the basis of this high identity or homology, it is virtually certain that the H8 gene also encodes a protein that participates in pore formation and DNA transfer. Hence we named it for tail pore formation (tpf). Except in its central portion, the H8 protein was closely related to its T5 homolog (aside from the central 370 amino acids, showing 79% identity) (Fig. 6). The central region (residues 380 to 750) was 36% identical to pb2, a value that still implies a comparable structural fold. It was noteworthy that in the more variable central region, the TonB-dependent phage H8 Tpf protein contained the sequence GEGIPVGLA, which has identity and similarity to the consensus TonB box region near the N termini of siderophore receptor proteins. The analogous pb2 protein of the TonB-independent phage T5 does not contain a similar sequence; a gap occurs in the alignment of Tpf and pb2 at this site.

DISCUSSION

Besides their function as transporters, OM porins usually serve as surface receptors for noxious agents like bacteriocins and bacteriophages. The first example of this multifunctionality was BtuB, the vitamin B12 receptor protein, that also recognizes E-group colicins (22) and the T5-like bacteriophage BF23 (8). TonA (later renamed FhuA) was another prototype of cell surface competition for reception of ferrichrome, colicin M, and the bacteriophages T1, T5, and φ80 (13, 82, 93, 101). Similarly, FepA (14), the OM receptor for FeEnt, also recognizes colicins B and D (100), but bacteriophage were not known to utilize FepA for penetration of the cell surface. Based on genetic and biochemical experiments, our results show that FepA serves as the surface receptor for bacteriophage H8. This finding is of additional importance because unlike its close relatives T5 and BF23, H8 requires TonB for infectivity.

Among several host strains for plasmids carrying fepA+, we found approximately the same level of susceptibility to H8. On the other hand, H8 plating efficiency varied with the FepA expression level: higher concentrations of FepA in the OM gave more PFU per H8 lysate, as previously noted and explained for bacteriophage λ (87). The best H8 plating efficiency occurred when FepA was expressed from the pHSG575 derivative pITS23, even though its copy number (3 to 5 per cell) is 20- to 70-fold less than that of the pUC18 derivative, pITS449 (100 to 200 per cell). This anomaly partly derived from different expression levels of FepA: the pHSG575 derivative produced approximately half again as much FepA as the pUC clones because the Fur-regulated promoters of both pITS449 and pT944 are truncated (5). These data concur with prior observations on FeEnt binding and uptake: cells harboring pITS23 have higher capacities and Vmax values than cells harboring pITS449 (4). However, it is also likely that strains harboring the pUC vectors are physiologically impaired in some unknown way because H8 also plated more efficiently on BN1071, which expressed FepA from the chromosome at a lower level.

In general, H8 infection was inhibited by mutations that are deleterious to FeEnt and colicin binding and/or uptake. The phage was sensitive to deletions in FepA and did not proliferate on bacteria producing aberrant receptor proteins in which the N-terminal globular domain of FepA was deleted or switched with that of FhuA. Next, deletions of FepA's surface loops either abrogated or decreased sensitivity to H8, and it was noteworthy that numerous deletions which do not prevent FeEnt uptake or ColB/D-killing abrogated H8 susceptibility. These data show that the phage adsorption process is more sensitive to the surface topology of the receptor protein than are the interactions with the metal complex or the toxin. Loop deletions may produce global effects on OM protein structure and function, and it is not possible to interpret the deletion phenotypes with the same clarity as individual substitutions. Yet numerous genetic and biochemical studies of OM proteins, including FepA, FhuA, and LamB, demonstrate their resilience to site-directed deletion of surface loops. In general, such precisely designed deletions do not reduce expression nor impair secretion to the OM nor distort overall tertiary structure (23, 45, 47, 68). Most loop deletion mutants retain their overall functionality, as is evident in Table 3: only one loop deletion, ΔL7, was completely nonfunctional. N domain loop deletions were less severe than those of the β-barrel loops, suggesting that the tail-fiber assemblage primarily requires complementarity with the external-most loops, which are superior to the N domain loops. Disruption of the interactions with surface loops weakens the adsorption equilibrium, such that the phage may dissociate from the cell before irreversible attachment occurs.

Mutations of individual residues in the surface loops were generally less detrimental, but several amino acids were important to H8 susceptibility. The biphasic process of ligand binding to FepA (73) occurs as a result of initial adsorption to the exterior-most residues (designated site B1 [16]) and secondary progression to binding equilibrium by interaction with amino acids in the interior of the receptor's vestibule (designated site B2 [16]). Among substitutions of Ala for aromatic residues in the outer B1 region of the vestibule, F329A reduced phage infection the most (95%); among Ala-for-Arg or Ala-for-Lys substitutions in the outer vestibule, only K483A comparably impaired H8 susceptibility (91%). Thus, among 46 substitution mutations in the loop extremities, only two reduced phage plating efficiency 1 log or more. Loss of other amino acids in the loops (R274, K332, Y478, Y553, K634, or K635) decreased infectivity, but only about twofold. Nevertheless, these data show that among the 46 individual surface loop mutations that we tested, eight more or less randomly distributed residues affected bacteriophage adsorption, showing that the phage tail has broad interactions with multiple outer loop regions. Previous experiments (4) led to the same conclusion for FeEnt and colicins B and D. In the interior, B2 region of the vestibule, other residues display a hierarchy of involvement with FeEnt, colicins (16, 67), and H8. Y260A increased the Kd and Km of FeEnt binding and transport 100-fold, with almost negligible impact on colicin killing (twofold). R316A, on the other hand, equally reduced both FeEnt transport affinity (50-fold) and colicin B and D susceptibility (5-fold). The combination R286A R316A exaggerated these effects. Thus, further inside the vestibule alteration of some residues affects only FeEnt uptake, whereas elimination of others disturbs the transport of both the ferric siderophore and the colicins. For H8, it was telling that Y260A, R286A, R316A, and R286A R316A reduced infection 98%, 93%, 76%, and 99%, respectively. These three amino acids are all important to both FeEnt uptake and phage penetration. F329 and K483 in the B1 region similarly contribute to both FeEnt uptake affinity and H8 infection efficiency. Together, the results indicate that H8 initially interacts with FepA over a larger portion of the receptor's surface area than does FeEnt (Fig. 3), but as adsorption progresses to penetration of the OM bilayer, the injection of phage DNA depends on some of the same core of acidic and basic residues that function in ferric siderophore internalization. The competitive inhibition of phage infection by FeEnt supports this interpretation.

The bacteriophage receptor-binding protein and the pore-forming tail tip protein constitute the flip side of this ligand-receptor dichotomy. For H8, the Rbp is most homologous to Hrs and pb5 (Oad) of BF23 and T5, respectively, and Tpf is related to the pb2 (D18-19) of T5. Despite the fact that the products of oad and hrs may functionally replace each other in the tails of T5 and BF23, respectively (39, 48), Mondigler et al. (62, 63) reported that no homology exists between these genes. The CLUSTAL W alignment of the T5, BF23, and H8 receptor binding proteins (Fig. 6), nevertheless, demonstrates that structural relationships do exist among them. In five regions of significant homology that we identified, the mean identity and similarity were 51% and 68%, respectively, which establishes the common fold of these proteins. Furthermore, the comparison of pb5, Hrs, and Rbp was potentially revealing with regard to the specificity of the three receptor binding proteins, in that the metal complexes that enter through FhuA, BtuB, and FepA are quite different in net charge. Unlike the iron centers of ferrichrome (neutral) and cyanocobalamin (+1; considering a PO4 moiety removed from the chelation site, B12 is neutral), FeEnt is an acidic metal complex with a net charge of −3 at physiological pH. Therefore, if the phages mimic the ferric siderophores during adsorption to their OM receptors, then we expect negative charges on the surface of the H8 receptor-binding protein relative to those of T5 and BF23. To this point, regions within T5 tail protein pb5 were previously roughly mapped with regard to receptor binding from the ability of deletion proteins to inhibit the adsorption of wild-type T5 (63). These results and the fact that the oad mutation (G166W) alters T5 adsorption to include the O antigen and reduce dependency on FhuA (40) suggested that residues 89 to 305 in pb5 contain the determinants of T5 binding to FhuA (63). Our sequence analyses concur with this conclusion and refine it. In addition to the regions of homology revealed by the CLUSTAL W comparison, we found two variable regions dispersed among them that, in the case of H8 only, manifest a significant negative charge (Fig. 6). These regions (residues 138 to 213 and 486 to 551, with net charges of −7 and −5, respectively) are the most obvious deviations between Rbp, pb5, and Hrs; they may therefore pertain to the specificity of receptor binding. However, previous experiments excluded 486 to 551 from receptor binding on the basis of its dispensability to T5 adsorption (63). These results, together with the preponderance of negative charge that appears in Rbp, suggest that H8 receptor binding specificity resides in region 138 to 213. Consistent with the notion that aromaticity constitutes a second determinant of receptor selectivity (4, 16), region 138 to 213 of Rbp also contains eight unique aromatic amino acids, relative to the homologous regions of pb5 and Hrs.