Abstract

Xylella fastidiosa is a plant pathogen that colonizes the xylem vessels, causing vascular occlusion due to bacterial biofilm growth. However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms driving biofilm formation in Xylella-plant interactions. Here we show that BigR (for “biofilm growth-associated repressor”) is a novel helix-turn-helix repressor that controls the transcription of an operon implicated in biofilm growth. This operon, which encodes BigR, membrane proteins, and an unusual beta-lactamase-like hydrolase (BLH), is restricted to a few plant-associated bacteria, and thus, we sought to understand its regulation and function in X. fastidiosa and Agrobacterium tumefaciens. BigR binds to a palindromic AT-rich element (the BigR box) in the Xylella and Agrobacterium blh promoters and strongly represses the transcription of the operon in these cells. The BigR box overlaps with two alternative −10 regions identified in the blh promoters, and mutations in this box significantly affected transcription, indicating that BigR competes with the RNA polymerase for the same promoter site. Although BigR is similar to members of the ArsR/SmtB family of regulators, our data suggest that, in contrast to the initial prediction, it does not act as a metal sensor. Increased activity of the BigR operon was observed in both Xylella and Agrobacterium biofilms. In addition, an A. tumefaciens bigR mutant showed constitutive expression of operon genes and increased biofilm formation on glass surfaces and tobacco roots, indicating that the operon may play a role in cell adherence or biofilm development.

Xylella fastidiosa is a plant pathogen that displays a broad host range and causes diseases in various economically important plants including citrus variegated chlorosis, Pierce's disease of grapevines, and leaf scorch of coffee (4, 9, 11). The bacterium is transmitted from plant to plant by specific insect vectors and colonizes the xylem vessels, leading to water and nutrient stress (2). The molecular mechanisms involved in the development of citrus variegated chlorosis symptoms are not well understood, but it is currently assumed that symptoms are caused by vascular occlusion of the xylem vessels due to bacterial biofilm formation (12, 20).

A molecular approach to better understanding of the complex biological behavior of X. fastidiosa and its interaction with citrus plants began with the sequencing of its genome (26). However, despite the availability of several X. fastidiosa genomes, the understanding of X. fastidiosa pathogenicity is still limited, in part by the fact that half of the Xylella genes encode hypothetical proteins (26). In addition, X. fastidiosa requires special growth conditions, and most strains that are pathogenic to citrus are not amenable to genetic manipulations. Thus, the structural and functional characterization of Xylella proteins with no assignable functions has gained increased attention in recent years.

The genome analysis of the citrus 9a5c strain identified a number of transcriptional factors with functions possibly associated with adaptation and pathogenicity (26). One of these factors is the XF0767 gene product, annotated as a “transcriptional regulator of the ArsR family” (26). Members of this family are metal sensors with a helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding domain that control metal resistance in bacteria (3). Interestingly, the XF0767 gene is located in an operon comprising four other open reading frames (ORFs) (26), none of which, nevertheless, appears to encode proteins related to metal reductases, thionins, or metal efflux pumps, normally found in bacterial metal detoxification operons (3). Instead, the Xylella operon encodes putative membrane proteins (XF0766 to XF0764) and a hydrolase (XF0768) belonging to the metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily, here designated beta-lactamase-like hydrolase (BLH).

We were interested in studying the operon comprising XF0768 to XF0764 because this gene cluster is found conserved in only four plant-associated bacteria, including Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and it appears to share features of both metal and antibiotic resistance operons; however, its biological function is unknown. The XF0767 protein shows identity to metal sensors and MarA (23), a transcriptional regulator for multiple antibiotic resistance (17, 25), whereas BLH, although similar to beta-lactamases, is an unusual protein in the sense that it carries a domain of unknown function (DUF442) fused to a beta-lactamase domain. This DUF442-beta-lactamase domain architecture is restricted to BLHs and is exclusively found in the operons of Xylella and related Rhizobiaceae, which suggests that BLH may have a novel hydrolytic activity that would be connected to a plant-associated lifestyle (27).

As a first approach to characterizing this gene cluster, we describe its regulation by the XF0767 protein. In this study we show that the product of the XF0767 gene, which we named BigR (for “biofilm growth-associated repressor”), encodes a novel HTH repressor that binds to a palindromic AT-rich sequence spanning the −10 region of the blh promoter and blocks transcription of the operon in both X. fastidiosa and A. tumefaciens. Although the biological role of the BigR operon is currently unknown, we present evidence indicating that BigR affects bacterial biofilm growth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions.

Escherichia coli cells were grown in LB (24) at 37°C with the appropriate antibiotics. X. fastidiosa strains 9a5c and J1a12 were grown in PW medium (10) at 28°C, whereas A. tumefaciens (C58) was grown in YEP or M9 medium (24) at 28°C in the presence of the required antibiotics.

Cloning of BigR in bacterial expression vectors.

The XF0767 gene (NP_298057) was amplified from Xylella genomic DNA with primers 5′-CCATGGTGAACGAAATGCGAG-3′ and 5′-CTCGAGTCACGCCTGTTTCTC-3′. PCR products were subcloned into pET28a (Novagen) for native BigR expression. The reverse oligonucleotide 5′-CTCGAGCGCCTGTTTCTCCTGTGC-3′ was used to create the pET28-BigR6his construct. To obtain the 12-amino-acid N-terminal deletion (ΔBigR), pET28-BigR and pET28-BigR6his were cut with NdeI/XhoI and inserted into pET29a (Novagen), generating ΔBigR and ΔBigR6his.

PCR amplification of promoter regions and reporter gene construction.

A 400-bp fragment upstream of the first ATG codon of Xylella blh was cloned into pGemT, linearized with ApaI, and religated, generating the 115-bp blh promoter (pxf115). A shorter fragment, amplified from pGem-pxf115 with primer SP6 and 5′-GATTTTTGCTGCAAGGATG-3′, was also cloned (pGem-pxf90). To obtain the reporter genes for E. coli assays, an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene was inserted into pGem-pxf115 with NcoI/NotI, generating pGem-pxf115GFP. Similarly, a 145-bp fragment upstream of A. tumefaciens blh was amplified from C58 genomic DNA with primers 5′-GGGCCCGCCTCTAGAATCTC-3′ and 5′-CTTACGGCCTCCATGGCTTC-3′ and was cloned upstream of EGFP (pGem-pat145GFP).

The reporter plasmids used in Xylella and Agrobacterium cells were prepared as follows. The pxf115GFP fragment cut with ApaI/SalI was inserted into the pSP3 vector (8), generating pSP-pxf115GFP, whereas pat145GFP cut with XbaI/SacI was inserted into pBI121 (Clontech), generating pBI-pat145GFP. To produce reporter plasmids carrying mutations in the blh promoters, complementary oligonucleotides carrying mutations within the BigR box (see Fig. 6A) were annealed and cloned in fusion with EGFP. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

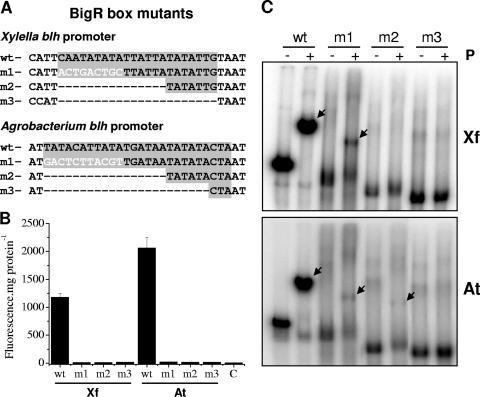

FIG. 6.

Mutations in the BigR box affected repressor binding and transcription from blh promoters. (A) Mutations within the BigR boxes of the Xylella and Agrobacterium blh promoters represented by m1, m2, and m3 (negative controls) relative to the wild-type (wt) sequences. In the m1 mutant, the first half of the palindrome was replaced by an unrelated sequence (white letters), but one of the −10 elements and the spacing between the −10 and −35 regions were maintained, whereas in the m2 and m3 mutants, deletions were made in the BigR box. (B) EGFP fluorescence of cell extracts of E. coli transformed with the X. fastidiosa (Xf) or A. tumefaciens (At) reporter plasmid carrying a wt or mutated promoter, relative to the background fluorescence of untransformed cells (control [C]). Results are means from four independent samples. (C) EMSA using the wt probe or a mutant probe from the X. fastidiosa or A. tumefaciens promoter in the presence (+) or absence (−) of BigR protein (P), showing loss of DNA binding activity with the mutated sequences. Arrows point to shifted bands.

Protein expression and purification.

E. coli BL21(DE3) cells transformed with pET constructs were grown at 37°C under agitation, and proteins were expressed by the addition of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (0.4 mM) and purified by standard nickel affinity chromatography. For the expression of native BigR and ΔBigR, cell extracts were loaded in a Q-Sepharose FF column (Amersham Biosciences) preequilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 1 M NaCl in the same buffer. Ammonium sulfate at a final concentration of 1 M was added, and the mixture was loaded into a phenyl-Sepharose HP column (Amersham Biosciences) preequilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM DTT, and 1 M (NH4)2SO4. The proteins were eluted in a linear gradient of 1 to 0 M (NH4)2SO4 in the same buffer. ΔBigR was further purified on a Superdex G75-16/60 column (Amersham Biosciences). The eluted proteins were concentrated and dialyzed against appropriate buffers, and their purity was estimated to be >97% by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

EMSA.

Five DNA probes, named 115, 90, 80, 60, and TATA, were prepared for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). The promoter fragments of 115 bp and 90 bp were excised from the plasmids and labeled by a 3′-end-filling reaction (24). The 80-bp probe was amplified by PCR and labeled with the Klenow fragment, whereas the 60-bp probe and the wild-type and mutated TATA probes were prepared by annealing and subsequent labeling of the complementary oligonucleotides (24).

Purified proteins (40 pmol) were incubated on ice for 15 min in the binding buffer [5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.025 U poly(dI-dC), 2.5% glycerol]. Each probe (30 fmol) was added, and the final mixture was incubated for a further 15 min on ice and resolved on a 6% acrylamide gel (24).

DNase I footprint analysis.

The 115-bp promoter fragment of pGem-pxf115 was amplified using the blh reverse primer (5′-GATGTCTACTATTCCCATGG-3′) and a T7 primer labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. The purified fragment was incubated with different amounts of BigR6his under the same conditions described for EMSA. The DNase I footprint reaction was performed according to standard procedures (24). A sequencing reaction of pGem-pxf115 was carried out using the T7 sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences), and the samples were separated in a denaturing sequencing gel (24).

CD spectroscopy.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements of purified BigR and the TATA probe were carried out on a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter at 22°C. The spectra were recorded in a 1-mm optical path cell with a wavelength range from 190 to 320 nm, a bandwidth with a step size of 0.5 nm, and a 50-nm·min−1 scan speed. Purified BigR (2 nmol) and the TATA probe (1 nmol) were dissolved separately in 0.2 mM HEPES (pH 8.0)-5 mM NaCl or were combined at the same ratio. For each measurement, the mean values for four spectra were taken to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, and each spectrum was corrected against the blank and analyzed by using the software provided by JASCO.

Transcription start site mapping.

The transcription start sites of the Xylella and Agrobacterium blh promoters were determined by rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (5′ RACE) (13). Total RNA extracted with RNeasy (QIAGEN) was treated with DNase I and reverse transcribed with specific blh internal primers. After PCR amplifications, several independent RACE products were cloned and sequenced.

Fluorimetric assays and fluorescence microscopy.

Bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation and lysed in 0.5 ml of B-Per reagent (Pierce) containing lysozyme (100 μg) and DNase I (5 U). The suspension was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged to remove insoluble materials. The protein concentration in the supernatant was measured with the bicinchoninic acid reagent (Pierce). The supernatant was analyzed in an AMINCO Bowman fluorimeter with the excitation and emission wavelengths set at 465 nm and 510 nm, respectively. Alternatively, bacterial cells were washed in sterile water and visualized with a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescent microscope using the B-2E/C fluorescein isothiocyanate filter.

Bacterial biofilms were grown on the surfaces of glass coverslips placed vertically inside test tubes. Cells were inoculated at an initial optical density (OD) of 0.05 into YEP medium and then incubated at 100 rpm and 30°C for 24 or 36 h. Coverslips were removed, stained by incubation in a 0.1% crystal violet solution for 1 min, and rinsed twice in fresh water. Stained biofilms were solubilized with dimethyl sulfoxide, and absorbance at 600 nm (A600) was measured. The amount of biofilm was estimated by the ratio of the absorbance of the stained biofilm to the turbidity (OD at 600 nm [OD600]) of the planktonic culture (A600/OD600) (22).

Plant inoculations.

Sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) leaves were infiltrated with suspensions (1.5 OD600 units) of Xylella J1a12 carrying pSP-pxf115GFP, whereas tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves were infiltrated with suspensions (0.8 OD600 unit) of Agrobacterium C58 carrying pBI-pat145GFP. Bacterial cells were recovered from the infiltrated leaf sectors at different times after bacterial infiltration and were visualized by fluorescent microscopy. For virulence assays, a crown gall-inducing A. tumefaciens strain transformed with pBI-pat145GFP was applied to the base of detached Kalanchoe linearifolia leaves kept at 25°C under fluorescent light and high relative humidity. After 20 days, tissues with induced crown galls were sliced and analyzed by fluorescent microscopy.

Agrobacterium C58 cells were attached to roots by using tobacco seedlings germinated in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (Sigma). Roots from 3-week-old seedlings were excised and incubated in M9 medium containing Agrobacterium C58 reporter cells at a final OD600 of 0.05 for 24 h at 28°C. The roots were washed in sterile water prior to visualization by fluorescence microscopy. To estimate the number of cells that remained attached to the root surfaces, washed roots were sonicated in water for 5 min and plated on YEP medium in serial dilutions.

Generation of A. tumefaciens insertion mutants and quantitative PCR (qPCR).

BigR (NCBI no. AAK89928) and BLH (AAK89929) genes from A. tumefaciens (C58) and the neomycin phosphotransferase gene from pBI121 were cloned into pGem-T and sequenced. The neomycin phosphotransferase gene was inserted into the internal NcoI/SalI sites of bigR and the SphI site of blh. The constructs were subcloned into the pOK1 suicide plasmid (15) and moved into C58 cells. Bacterial cells were grown on kanamycin (50 mg/liter) and subsequently on 5% sucrose to select double recombination mutants, which were verified by PCR and Southern blotting (24).

DNase I-treated RNA from wild-type and bigR mutant cells were reverse transcribed with primers specific to the gene for membrane protein 1. The expression levels of blh were measured by qPCR using an A. tumefaciens gapdh gene as an internal control. Reactions were performed in triplicate using the SYBR green mix, and the results were analyzed with 7500 System software (Applied Biosystems) using the relative quantification mode.

RESULTS

BigR is a novel HTH protein that binds to the DNA region upstream of the Xylella XF0768-XF0764 operon.

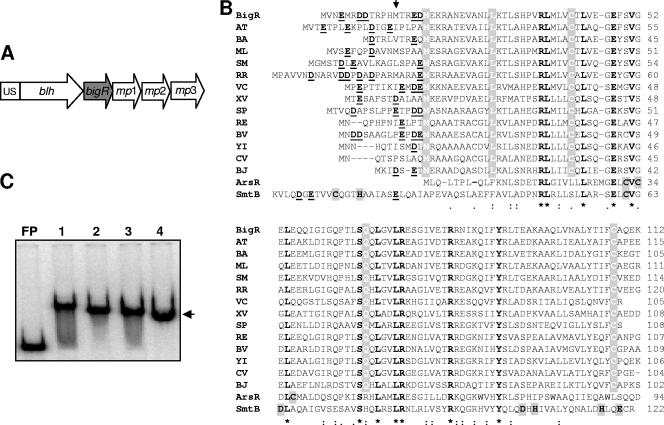

Protein sequence alignment shows that the predicted product of the XF0767 gene (BigR), identified from a conserved operon in X. fastidiosa (26) (Fig. 1A), is homologous to prokaryotic HTH transcriptional regulators of the ArsR/SmtB family (Fig. 1B). BigR is 26% identical to ArsR and SmtB, and the greatest similarity to ArsR/SmtB is found within the HTH core, which includes several invariable residues (Fig. 1B). On the other hand, BigR shows stronger identity to a large group of uncharacterized proteins found in plant pathogens and symbionts, human pathogens, and other bacteria. In particular, BigR is 64% identical to its A. tumefaciens homolog (Fig. 1B). Although most of these proteins have been annotated as transcriptional factors of the ArsR family, it is likely that they represent a new HTH subfamily of ArsR regulators. This assumption is based on the fact that BigR and the uncharacterized ArsR/SmtB-like proteins whose sequences are shown in Fig. 1B have an acidic N terminus and a number of conserved residues (M18, L29, C42, Q67, and C108 of BigR) not found in ArsR or SmtB.

FIG. 1.

BigR is homologous to prokaryotic HTH transcriptional factors and binds to upstream sequences (US) of its own operon. (A) Schematic view of the Xylella XF0768-XF0764 operon, including genes encoding BigR, putative membrane proteins 1 through 3, and a hydrolase (blh). (B) Sequence alignment between BigR and putative members of the ArsR/SmtB family, generated by ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalW). BA, Brucella abortus (NCBI no. AAX76167); ML, Mesorhizobium loti (NP_103569); SM, Sinorhizobium meliloti (NP_435817); AT, Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 (AAK89928); RR, Rhodospirillum rubrum (ZP_00268696); VC, Vibrio cholerae (NP_233031); XV, Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (YP_364177); RE, Ralstonia eutropha (ZP_00171423); BV, Burkholderia vietnamiensis (ZP_00422748); YI, Yersinia intermedia (ZP_00831742); CV, Chromobacterium violaceum (NP_899754); BJ, Bradyrhizobium japonicum (NP_772413); SP, Silicibacter pomeroyi (YP_165254). ArsR is from Escherichia coli (P15905), and SmtB is from Synechococcus elongatus (P30340). Invariable residues are boldfaced; asterisked residues are restricted to the HTH domain. Amino acids that are conserved only in the uncharacterized members of the ArsR/SmtB family (all except ArsR and SmtB) are shaded with white letters. Acidic residues in the N termini are boldfaced and underlined, and the residues responsible for metal coordination in ArsR and SmtB are shaded with boldface letters. The arrow points to the initial methionine of ΔBigR. (C) EMSA showing that BigR (lanes 1 and 2) and ΔBigR (lanes 3 and 4), with (lanes 1 and 3) or without (lanes 2 and 4) the His6 tag, recognize the US of the blh gene. Arrow indicates shifted bands. FP, free probe.

Recombinant BigR proteins were purified for functional studies. To analyze the requirement of the acidic N terminus for protein activity, a shorter version of BigR lacking the first 12 nonconserved residues, designated ΔBigR (Fig. 1B), was made. Since the predicted function of BigR was to repress transcription, we anticipated that it might bind to regulatory elements located upstream of the blh gene (Fig. 1A). Gel shift assays showed that both variants of recombinant BigR bound to the DNA fragment corresponding to the blh promoter, indicating that the N-terminal deletion in ΔBigR or the His6 tag in the C terminus was not required for DNA interaction (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with the idea that the region responsible for DNA binding lies within the HTH domain.

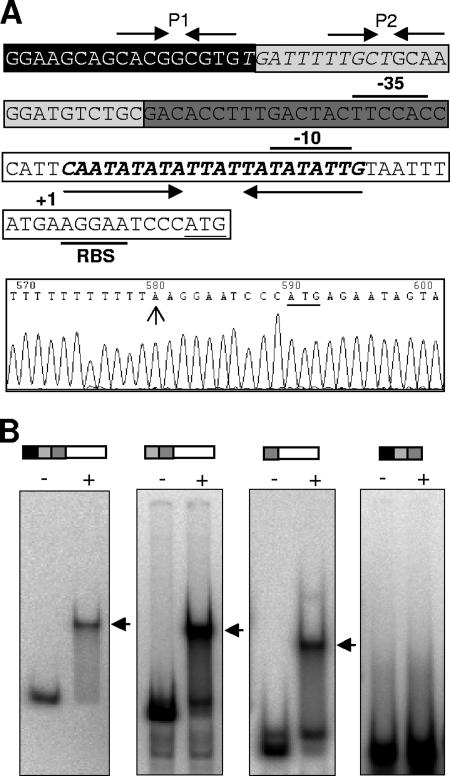

BigR binds to an AT-rich palindrome, and this binding alters its secondary structure.

To finely map the region of the blh promoter that interacted with BigR, a series of promoter fragments for the EMSA experiments was generated. In addition, the transcription start site of the Xylella blh promoter was determined, allowing the location of the −10 and −35 regions (Fig. 2A). EMSA performed with the different promoter fragments showed that BigR interacted with DNA probes containing the AT-rich sequence spanning the −10 region (Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, this sequence shows the dyad symmetry of a long, imperfect palindrome (CAATATATATTATTATATATTG) that incorporates two adjacent TATATATT elements, one of which overlaps with the −10 region (Fig. 2A). A footprint assay further revealed that BigR binds exactly to the palindromic AT-rich element, termed the “BigR box” (Fig. 3A). In addition, a double-stranded DNA corresponding to the BigR box sequence (TATA probe) was shifted by BigR, and this binding was abolished when the unlabeled probe was used in a competition EMSA, thus confirming that BigR binds to the BigR box (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 2.

BigR binds to an AT-rich element spanning the −10 region of the Xylella blh promoter. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the promoter showing the −35 and −10 elements, the putative ribosome-binding site (RBS), and the initial ATG codon (underlined). The transcription start site determined by RACE is indicated by the arrow in the DNA sequencing electropherogram. The −10 region overlaps with the dyad symmetry sequence (bold italics) of an imperfect palindrome (opposing arrows), the BigR box. Two additional palindromes, P1 and P2, are indicated by opposing arrows. P2 overlaps with a sequence (italics) that is similar to regulatory elements bound by MarA and ArsR (23, 29). (B) EMSA experiments with BigR6his (+) and the different DNA probes, represented by bars corresponding to the promoter elements shown in panel A (black, P1; light gray, P2; dark gray, −35 element; white, −10 element plus RBS), showing that the protein binds to the promoter fragments harboring the AT-rich sequence. Shifted bands (arrows) and the free probe (−) are indicated.

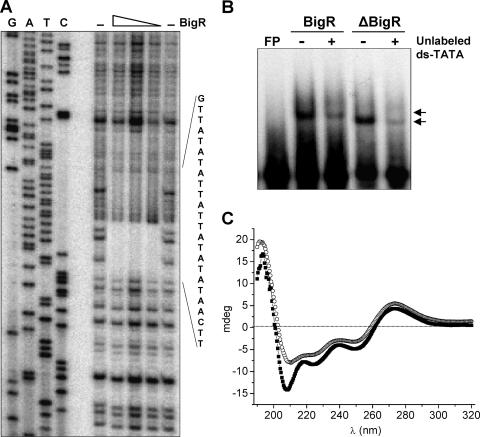

FIG. 3.

BigR binds to the palindromic AT-rich sequence, and this alters its secondary structure. (A) Footprint analysis of the Xylella blh promoter in the presence of decreasing amounts of BigR relative to that with a no-protein control (−). The footprinted area is read from the sequencing reaction on the left. (B) Gel shift using the double-stranded (ds) TATA probe (the BigR box sequence). A 10-fold excess (+) of the unlabeled ds-TATA probe was able to displace the labeled probe shifted by both BigR and ΔBigR (arrows). FP, free probe. (C) CD analysis of BigR in the presence of the ds-TATA probe. The resulting spectrum of the mixed protein and DNA (filled squares) differs from the theoretical sum (open circles) of the spectra measured separately, indicating changes in the secondary structure of the protein upon interaction with the DNA. The two minimum points at 208 and 222 nm also indicate that BigR has a high content of α-helices.

The interaction of BigR with the TATA probe was further evidenced by CD. The CD spectrum of BigR shows two minimum points at 208 and 222 nm, indicating high contents of α-helices, consistent with an HTH domain in the protein. When BigR was mixed with the TATA probe, the resulting spectrum differed significantly from the theoretical sum of the protein and DNA spectra measured separately, showing that BigR changes its secondary structure upon interaction with DNA (Fig. 3C). In fact, the signal increases at 208 and 222 nm in the presence of DNA clearly show that BigR gained secondary structure when in a complex with DNA (Fig. 3C).

The BigR box is conserved in promoters of homologous operons from plant-associated bacteria.

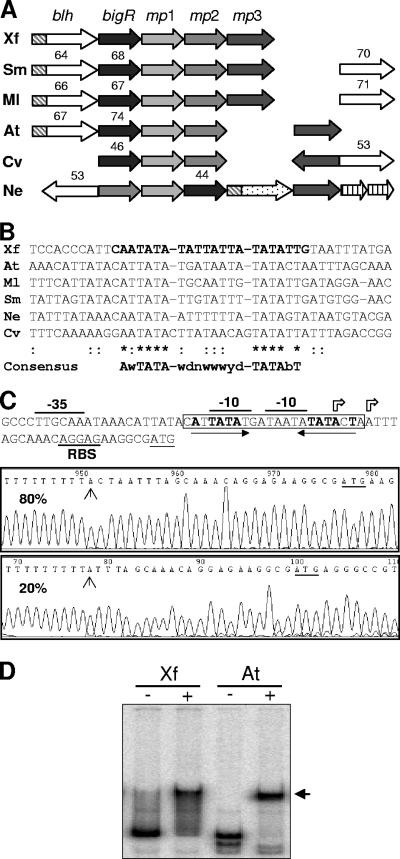

The BigR operon is conserved in X. fastidiosa, A. tumefaciens, Mesorhizobium loti, and Sinorhizobium meliloti; however, related operons with different gene compositions and synteny are also found in other bacterial species (Fig. 4A). The upstream sequences of blh genes from related operons were aligned, and a consensus sequence for the BigR box was derived (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the consensus shows two invariable TATA elements spaced by 8 to 10 nucleotides (Fig. 4B), and one of them matches the −10 region of the Xylella blh promoter (Fig. 2A), suggesting that these conserved elements are important for operon regulation. In agreement with this idea, two −10 regions were mapped within the BigR box in the A. tumefaciens blh promoter, and both closely coincide with the two invariable TATA elements of the consensus (Fig. 4C). Although a single transcription start site was identified in the Xylella promoter, an additional site similar to the Agrobacterium promoter is predicted, since a putative −35 region (TTGACT) is separated by 20 nucleotides from the upstream TATA element that does not overlap with the mapped −10 region (Fig. 2A). Taken together, the results indicate that at least in X. fastidiosa and A. tumefaciens, the operon is similarly regulated. Accordingly, the Xylella BigR protein binds to the Agrobacterium blh promoter under the same conditions under which it binds to the Xylella promoter (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 4.

The BigR box is conserved in promoters of related operons found in plant-associated bacteria. (A) Schematic view of BigR operons from X. fastidiosa (Xf), A. tumefaciens (At), S. meliloti (Sm), M. loti (Ml), Chromobacterium violaceum (Cv), and Nitrosomonas europaea (Ne). Joined arrows represent ORFs clustered into operons, and arrows with the same shading indicate orthologous ORFs. Open arrows fused to hatched rectangles (DUF442) represent conserved blh genes, whereas blh without DUF442 is shown by open arrows only. Striped arrows, ORFs unique to the N. europaea operon, which also harbors a DUF442 hydrolase (stippled arrow). Numbers above ORFs are the percentages of identity between the Xylella BLH/BigR proteins and their orthologs. (B) Nucleotide sequence alignment of upstream sequences of the blh genes showing the BigR box consensus. (C) Nucleotide sequence of the A. tumefaciens blh promoter showing two transcription start sites (arrows) and other promoter elements, including the BigR box (boxed) and its AT-rich palindrome (opposing arrows). The frequencies of the two transcription start sites are given in the sequencing run diagrams.(D) EMSA performed with BigR (+) and the X. fastidiosa or A. tumefaciens blh promoter probe, showing the BigR shifted bands (arrow).

BigR functions as a transcriptional repressor.

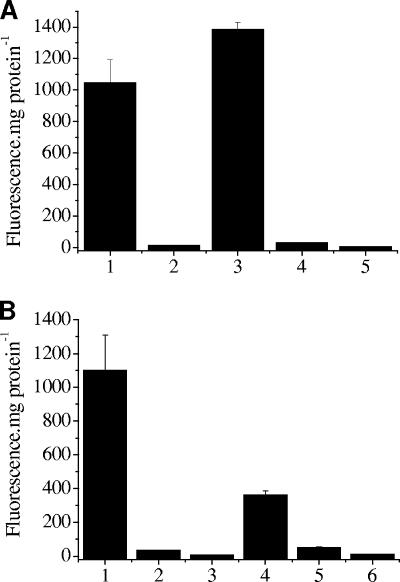

To investigate the in vivo role of BigR as a transcriptional repressor, E. coli cells were transformed with reporter plasmids carrying an EGFP gene under the control of the Xylella or the Agrobacterium blh promoter. These cells exhibited high levels of EGFP expression, indicating strong activity of both native promoters in the absence of BigR. However, fluorescence was remarkably reduced when BigR was expressed in the cells, indicating that the protein acts as a repressor in vivo (Fig. 5A). The fact that BigR down-regulated EGFP expression driven by the Agrobacterium blh promoter is consistent with its ability to bind this promoter in vitro (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 5.

BigR functions as a transcriptional repressor. (A) EGFP fluorescence in cell extracts of E. coli carrying the Xylella pGem-pxf115GFP (bars 1 and 2) or the Agrobacterium pGem-pat145GFP (bars 3 and 4) reporter plasmid. Cells carrying the reporters and the pET28-BigR plasmid (bars 2 and 4) showed a reduction in EGFP fluorescence relative to that for nontransformed cells (bar 5). (B) EGFP fluorescence in E. coli cells carrying the Xylella pSP-pxf115GFP (bar 1) or the Agrobacterium pBI-pat145GFP (bar 4) reporter plasmid relative to fluorescence levels driven by the same reporters in Xylella (bar 2) and Agrobacterium (bar 5) cells, respectively. The background fluorescence of nontransformed Xylella (bar 3) and Agrobacterium (bar 6) cells is shown. Results are means from three independent samples.

When X. fastidiosa and A. tumefaciens cells were transformed with the reporter plasmids, low levels of EGFP fluorescence were detected relative to the levels observed in E. coli carrying the reporters but lacking the repressor (Fig. 5B). The low transcriptional activities of the blh promoters detected in X. fastidiosa and A. tumefaciens are consistent with the presence of the repressor in these cells.

Mutations in the BigR box affected repressor binding and transcription from blh promoters.

Since the BigR box overlapped with the −10 regions in both the Xylella and the Agrobacterium blh promoter, we tested its requirement for promoter activity in vivo. Indeed, nucleotide substitutions or deletions in the conserved TATA elements of both promoters (Fig. 6A) significantly affected transcription of the reporter genes in E. coli. The promoter mutants that retained one of the −10 elements still showed residual transcriptional activity similar to that of promoters lacking the full BigR box, suggesting that both invariable TATA elements are required for promoter activity (Fig. 6B). As expected, the mutations also affected repressor binding (Fig. 6C), supporting the idea that the BigR box is required for BigR and RNA polymerase binding.

The BigR operon is transcribed in bacterial biofilms.

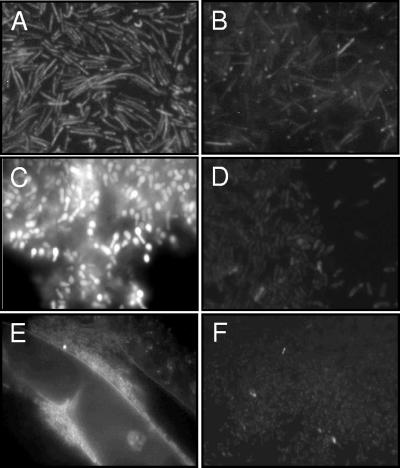

Due to similarities found between BLH and bacterial beta-lactamases, glyoxalases II (GloB), and lactonases, the Xylella and Agrobacterium reporter cells were grown in the presence of several beta-lactams, S-lactoylglutathione, or acyl-homoserine lactone (AHL), without, however, any significant changes in cell fluorescence (data not shown). In addition, the fluorescence levels of the reporter cells were not affected by treatments with different metal ions (data not shown), indicating that the operon is not involved in metal resistance. We noticed, nevertheless, that both Xylella and Agrobacterium reporter cells grown as biofilms showed increased fluorescence relative to that of cells that remained in suspension (Fig. 7). To determine whether bacterial cells attached to a plant surface would show a similar response, the Agrobacterium reporter cells were allowed to adhere to tobacco roots. Cells adherent to the root surfaces also showed increased fluorescence relative to that of cells remaining in suspension (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

EGFP fluorescence of bacterial reporter cells grown as biofilms compared to that of cells in suspension. X. fastidiosa (A and B) and A. tumefaciens (C and D) reporter cells were grown on the surfaces of glass slides (A and C) and washed in sterile water before visualization under the fluorescence microscope at ×1,000 magnification. Planktonic cells (B and D) were pelleted and resuspended in a small volume of water prior to visualization to obtain a density of bacterial cells comparable to that of the biofilms. A. tumefaciens reporter cells attached to tobacco roots (E) showed increased EGFP fluorescence relative to that of nonattached cells (F) at ×100 magnification.

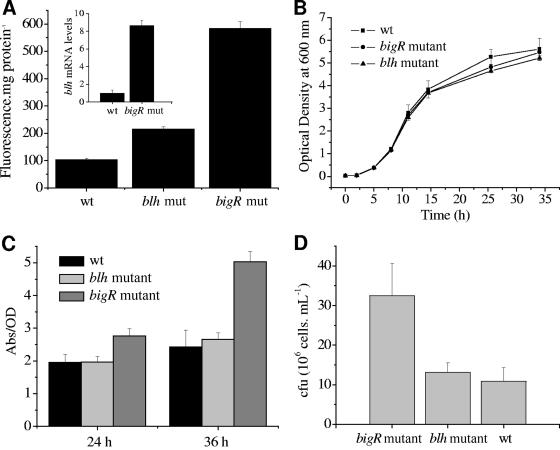

Disruption of the A. tumefaciens bigR gene altered biofilm growth.

To further analyze the biological function of the operon, bigR and blh were mutated by homologous replacement with a copy of the genes interrupted by a kanamycin resistance gene. Due to difficulties in obtaining insertion mutants in Xylella, only Agrobacterium mutants were isolated. Independent mutants were shown to have identical single-kanamycin-cassette insertions within the bigR or blh gene by PCR and Southern blotting (data not shown). The effects of these insertions were further evidenced with the reporter gene. The bigR insertion mutant exhibited sixfold-higher EGFP expression than controls (Fig. 8A), a finding that indicates a lack of repressor activity and thus confirms that BigR functions as a repressor. Accordingly, the expression level of blh, measured by qPCR, was much higher for the bigR insertion mutant (Fig. 8A). The blh mutant also showed a small (twofold) but significant increase in operon activity, indicating that disruption of the first ORF of the operon influenced the synthesis of the repressor (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Effects of bigR and blh gene disruption on operon activity and bacterial growth. (A) EGFP fluorescence levels measured in A. tumefaciens wild-type (wt), blh mutant (mut), and bigR mutant cells carrying the reporter plasmid. (Inset) Expression of blh in wt and bigR mutant cells, measured by qPCR. (B) Bacterial growth curves of wt, blh mutant, and bigR mutant cells grown in suspension, monitored by measuring the OD600. (C) Comparison of biofilm formation by the blh or bigR mutant with that by wt cells, measured by the ratio of the A600 of the stained biofilm to the turbidity (OD600) of the planktonic culture (Abs/OD). Results are means from five independent samples. (D) Average number of A. tumefaciens cells (expressed in CFU) recovered from tobacco roots after bacterial coincubation. Results are means from three independent replicates.

To know whether these mutations would affect bacterial growth in suspension or in biofilms, growth curves in liquid medium and biofilm formation on glass coverslips and tobacco roots were compared for the mutants and wild-type cells. While the bigR and blh mutants displayed normal growth in suspension (Fig. 8B), the bigR mutant showed altered biofilm formation on glass surfaces and tobacco roots (Fig. 8C and D). On glass surfaces, the bigR mutant exhibited a significantly greater biofilm mass than the blh mutant or wild-type bacteria at 24 and 36 h of growth (Fig. 8C). Similarly, bigR mutants formed more biofilm mass on the surfaces of tobacco roots than wild-type or blh mutant cells (Fig. 8D). This finding is consistent with the increased operon activity in A. tumefaciens cells attached to the root surface (Fig. 7).

DISCUSSION

Nearly half of the X. fastidiosa genes encode proteins of unknown function (26). Here we describe the first molecular and functional characterization of a novel HTH factor from X. fastidiosa that controls the transcription of an operon also found in A. tumefaciens and other plant-associated bacteria. We demonstrate that BigR, initially assigned as a transcriptional regulator of the ArsR family (26), indeed functions as a transcriptional repressor but displays properties significantly different from those of ArsR proteins. We present evidence showing that the BigR binding site carries two conserved TATA elements that coincide with two alternative −10 regions in the Xylella and Agrobacterium blh promoters. Mutations in the BigR box significantly affected transcription and the DNA-binding activity of the repressor, suggesting that BigR represses transcription by competing with the sigma 70 factor for the same promoter site, a mechanism of action common to many bacterial repressors (18).

Although the biological function of BigR is to repress transcription, it is not clear at this point whether a ligand is required to displace the repressor from DNA to allow transcription or whether the acidic N-terminal region of BigR would play a role in the binding of such a ligand, since this region is common to many BigR homologs and is not necessary for DNA binding. The hypothesis that BigR could function as a metal sensor similarly to ArsR/SmtB was investigated; however, several lines of evidence indicate that it probably does not function as such. For instance, BigR shares relatively low sequence identity with ArsR/SmtB, and the operon it regulates does not encode proteins related to metal resistance. In addition, the DNA-binding activities of BigR detected by EMSA, the in vivo activities of the operons, and the growth of the bigR and blh mutants were not influenced by metal ions (data not shown). Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that BigR is a metal ligand protein, and the roles of M18, C42, and C108, which are conserved in this group of repressors (Fig. 1B), deserve further study. These features and the existence of BigR homologs in several bacterial species suggest that BigR and related proteins form a new HTH subfamily of ArsR regulators, in which BigR could become the founding protein, since it is the first member to be characterized.

The BigR operon is restricted to a few plant-associated bacteria, and curiously, it is missing in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, an important citrus pathogen most closely related to X. fastidiosa (7). Considering that almost 74% of the Xylella genes have homologs in X. axonopodis pv. citri (19), it is reasonable to suppose that the BigR operon might confer some kind of adaptation on Xylella that would be related to its lifestyle or mechanism of pathogenicity. It is particularly interesting that a related BigR operon is found in Brucella suis, an animal pathogen with a genome remarkably similar to those of A. tumefaciens and M. loti (21). B. suis is predicted to have the capacity to utilize plant-derived compounds and to survive in the soil for long periods (21). Thus, whether or not the BigR operon in B. suis is important for bacterial survival in the soil or in contact with plant material remains to be investigated.

Another interesting feature of the BigR operon is that some of its ORFs are unique to this gene cluster (Fig. 4A). For instance, the occurrence of DUF442 fused to the beta-lactamase/glyoxalase II domain is restricted to X. fastidiosa, A. tumefaciens, S. meliloti, M. loti, Rhizobium etli, and Rhizobium leguminosarum. Thus, the unique combination of these protein domains might confer on BLH a new hydrolytic activity that would be particular to these bacteria (27). BLH also contains a zinc-binding motif (HxHxDH) that is conserved in members of the metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily (6), including GloB and lactonases. GloB participates in the detoxification of methylglyoxal, whereas lactonases are required for AHL hydrolysis and have been implicated in the quorum-quenching phenomenon (5, 28). We tested whether the substrates of these enzymes would activate the operon or displace BigR from DNA but obtained no positive results. In addition, both the bigR and the blh mutant exhibited growth similar to that of controls in the presence of AHL or at high cell densities (data not shown), an indication that BLH is not involved in a quorum-quenching phenomenon.

The idea of BLH functioning as an ordinary beta-lactamase was investigated by testing several beta-lactams for the activation of the operon, and antibiogram assays were performed to evaluate the sensitivities of the bigR and blh mutants to different classes of antibiotics, again with no positive results. Although the involvement of the operon in antimicrobial resistance cannot be ruled out, the available information suggests that BLH is not a typical beta-lactamase.

To test whether the operon would be active in response to a plant signal, the Xylella and Agrobacterium reporter cells were infiltrated into plant leaves; however, cells recovered from the infiltrated tissues exhibited less fluorescence than cultured cells (data not shown). Also, a crown gall-inducing strain of A. tumefaciens carrying the reporter plasmid showed no fluorescence in developed galls induced in Kalanchoe leaves, suggesting that the operon is not activated during infection. These results are consistent with the observation that the corresponding operon in S. meliloti (loci SMa1057 to SMa1050) is tightly repressed during nodulation in the host Medicago truncatula (1).

The fact that the operon is up-regulated in bacterial biofilms and in cells attached to root surfaces indicates that it may be important for cell adherence or biofilm development. This is consistent with the observation that the bigR-null mutant formed more biofilm mass than wild-type cells on both glass and root surfaces. Interestingly, one of the characterized A. tumefaciens mutants whose surface interactions are affected has a mutation in the sinR gene, an HTH transcriptional regulator of the FNR family. sinR is required for normal maturation of biofilms on both inert surfaces and plant surfaces (22). Curiously, sinR is located adjacent to a gene encoding a putative metal-dependent hydrolase containing an HxHxDH motif similar to BLH.

In X. fastidiosa, a number of mutations have recently been identified and shown to affect biofilm formation and cell aggregation (14, 16, 20). The rpfF gene, for instance, is required for the synthesis of a diffusible signal molecule that mediates cell-cell signaling (20). The facts that biofilm formation by rpfF mutants was affected in the insect foregut but not in the xylem (20) and that other factors such as type I pili (16) and adhesins (14) are also required for normal biofilm growth indicate that biofilm formation in Xylella depends on multiple components and is under very complex control mechanisms.

Surprisingly, biofilm growth was not affected in the blh mutant under the conditions tested. Since other regulatory proteins may influence biofilm formation in A. tumefaciens (22), it is possible that a blh mutant biofilm phenotype could not be clearly observed because of functional redundancy or an interplay of genes controlling biofilm growth and maturation. Further studies on the architecture and development of bigR and blh mutant biofilms may provide new insights into the function of the BigR operon.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marilis V. Marques for providing the pSP3 vector and Zildene G. Correa for DNA sequencing. We also thank Elaine Martins for helping with X. fastidiosa transformation and Jörg Kobarg for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by FAPESP grants (03/08316-5, Smolbnet 00/10266-8, and Cepid 98/14138-2). Rosicler L. Barbosa and Celso E. Benedetti received fellowships from FAPESP and CNPq, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnett, M. J., C. J. Toman, R. F. Fisher, and S. R. Long. 2004. A dual-genome symbiosis chip for coordinate study of signal exchange and development in a prokaryote-host interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:16636-16641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brlansky, R. H., I. W. Timmer, W. J. French, and R. E. McCoy. 1983. Colonization of the sharpshooter vectors, Oncometopia nigricans and Homalodisca coagulata, by xylem-limited bacteria. Phytopathology 73:530-535. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busenlehner, L. S., M. A. Pennella, and D. P. Giedroc. 2003. The SmtB/ArsR family of metalloregulatory transcriptional repressors: structural insights into prokaryotic metal resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, C. J., M. Garnier, L. Zreik, V. Rossetti, and J. M. Bové. 1993. Culture and serological detection of the xylem-limited bacterium causing citrus variegated chlorosis and its identification as a strain of Xylella fastidiosa. Curr. Microbiol. 27:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chevrot, R., R. Rosen, E. Haudecoeur, A. Cirou, B. J. Shelp, E. Ron, and D. Faure. 2006. GABA controls the level of quorum-sensing signal in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103:7460-7464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daiyasu, H., K. Osaka, Y. Ishino, and H. Toh. 2001. Expansion of the zinc metallo-hydrolase family of the β-lactamase fold. FEBS Lett. 503:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Silva, A. C., J. A. Ferro, F. C. Reinach, C. S. Farah, L. R. Furlan, R. B. Quaggio, C. B. Monteiro-Vitorello, M. A. Van Sluys, N. F. Almeida, L. M. Alves, A. M. do Amaral, M. C. Bertolini, L. E. A. Camargo, G. Camarotte, F. Cannavan, J. Cardozo, F. Chambergo, L. P. Ciapina, R. M. B. Cicarelli, L. L. Coutinho, J. R. Cursino-Santos, H. El-Dorry, J. B. Faria, A. J. S. Ferreira, R. C. C. Ferreira, M. I. T. Ferro, E. F. Formighieri, M. C. Franco, C. C. Greggio, A. Gruber, A. M. Katsuyama, L. T. Kishi, R. P. Leite, Jr., E. G. M. Lemos, M. V. F. Lemos, E. C. Locali, M. A. Machado, A. M. B. N. Madeira, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, E. C. Martins, J. Meidanis, C. F. M. Menck, C. Y. Miyaki, D. H. Moon, L. M. Moreira, M. T. M. Novo, V. K. Okura, M. C. Oliveira, V. R. Oliveira, H. A. Pereira, Jr., A. Rossi, J. A. D. Sena, C. Silva, R. F. de Souza, L. A. F. Spinola, M. A. Takita, R. E. Tamura, E. C. Teixeira, R. I. D. Tezza, M. Trindade dos Santos, D. Truffi, S. M. Tsai, F. F. White, J. C. Setubal, and J. P. Kitajima. 2002. Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature 417:459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva Neto, J. F., T. Koide, S. L. Gomes, and M. V. Marques. 2002. Site-directed gene disruption in Xylella fastidiosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 210:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, M. J., A. H. Purcell, and S. V. Thomson. 1978. Pierce's disease of grapevines: isolation of the causal bacterium. Science 199:75-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, M. J., B. C. Raju, R. H. Brlansky, R. F. Lee, L. W. Timmer, R. C. Norris, and R. E. McCoy. 1983. Periwinkle wilt bacterium: axenic culture, pathogenicity, and relationships to other gram-negative, xylem-inhabiting bacteria. Phytopathology 73:1510-1515. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Lima, J. E. O., V. S. Miranda, J. S. Hartung, R. H. Brlansky, A. Coutinho, S. R. Roberto, and E. F. Carlos. 1998. Coffee leaf scorch bacterium: axenic culture, pathogenicity, and comparison with Xylella fastidiosa of citrus. Plant Dis. 82:94-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Souza, A. A., M. A. Takita, H. D. Coletta-Filho, C. Caldana, G. M. Yanai, N. H. Muto, R. C. de Oliveira, L. R. Nunes, and M. A. Machado. 2004. Gene expression profile of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa during biofilm formation in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237:341-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frohman, M. A., M. K. Dush, and G. R. Martin. 1988. Rapid production of full-length cDNAs from rare transcripts: amplification using a single gene-specific oligonucleotide primer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:8998-9002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilhabert, M. R., and B. C. Kirkpatrick. 2005. Identification of Xylella fastidiosa antivirulence genes: hemagglutinin adhesins contribute to X. fastidiosa biofilm maturation and colonization and attenuate virulence. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 18:856-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huguet, E., K. Hahn, K. Wengelnik, and U. Bonas. 1998. hpaA mutants of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria are affected in pathogenicity but retain the ability to induce host-specific hypersensitive reaction. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1379-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, Y., G. Hao, C. D. Galvani, Y. Meng, L. De La Fuente, H. C. Hoch, and T. J. Burr. 2007. Type I and type IV pili of Xylella fastidiosa affect twitching motility, biofilm formation and cell-cell aggregation. Microbiology 153:719-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin, R. G., W. K. Gillette, S. Rhee, and J. L. Rosner. 1999. Structural requirements for marbox function in transcriptional activation of mar/sox/rob regulon promoters in Escherichia coli: sequence, orientation and spatial relationship to the core promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 34:431-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molina-Henares, A. J., T. Krell, M. Eugenia Guazzaroni, A. Segura, and J. L. Ramos. 2006. Members of the IclR family of bacterial transcriptional regulators function as activators and/or repressors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30:157-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreira, L. M., R. F. de Souza, N. F. Almeida, Jr., J. C. Setúbal, J. C. Oliveira, L. R. Furlan, J. A. Ferro, and A. C. R. da Silva. 2004. Comparative genomics analyses of citrus-associated bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 42:163-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman, K. L., R. P. Almeida, A. H. Purcell, and S. E. Lindow. 2004. Cell-cell signaling controls Xylella fastidiosa interactions with both insects and plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:1737-1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulsen, I. T., R. Seshadri, K. E. Nelson, J. A. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, T. D. Read, R. J. Dodson, L. Umayam, L. M. Brinkac, M. J. Beanan, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, A. S. Durkin, J. F. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, B. Ayodeji, M. Kraul, J. Shetty, J. Malek, S. E. Van Aken, S. Riedmuller, H. Tettelin, S. R. Gill, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, D. L. Hoover, L. E. Lindler, S. M. Halling, S. M. Boyle, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. The Brucella suis genome reveals fundamental similarities between animal and plant pathogens and symbionts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13148-13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramey, B. E., A. G. Matthysse, and C. Fuqua. 2004. The FNR-type transcriptional regulator SinR controls maturation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens biofilm. Mol. Microbiol. 52:1495-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhee, S., R. G. Martin, J. L. Rosner, and D. R. Davies. 1998. A novel DNA-binding motif in MarA: the first structure for an AraC family transcriptional activator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10413-10418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Schneiders, T., T. M. Barbosa, L. M. McMurry, and S. B. Levy. 2004. The Escherichia coli transcriptional regulator MarA directly represses transcription of purA and hdeA. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9037-9042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson, A. J. G., F. C. Reinach, P. Arruda, F. A. Abreu, M. Acencio, R. Alvarenga, L. M. C. Alves, J. E. Araya, G. S. Baia, C. S. Baptista, M. H. Barros, E. D. Bonaccorsi, S. Bordin, J. M. Bové, M. R. S. Briones, M. R. P. Bueno, A. A. Camargo, L. E. A. Camargo, D. M. Carraro, H. Carrer, N. B. Colauto, C. Colombo, F. F. Costa, M. C. R. Costa, C. M. Costa-Neto, L. L. Coutinho, M. Cristofani, E. Dias-Neto, C. Docena, H. El-Dorry, A. P. Facincani, A. J. S. Ferreira, V. C. A. Ferreira, J. A. Ferro, J. S. Fraga, S. C. França, M. C. Franco, M. Frohme, L. R. Furlan, M. Garnier, G. H. Goldman, M. H. S. Goldman, S. L. Gomes, A. Gruber, P. L. Ho, J. D. Hoheisel, M. L. Junqueira, E. L. Kemper, J. P. Kitajima, J. E. Krieger, E. E. Kuramae, F. Laigret, M. R. Lambais, L. C. C. Leite, E. G. M. Lemos, M. V. F. Lemos, S. A. Lopes, C. R. Lopes, J. A. Machado, M. A. Machado, A. M. B. N. Madeira, H. M. F. Madeira, C. L. Marino, M. V. Marques, E. A. L. Martins, E. M. F. Martins, A. Y. Matsukuma, C. F. M. Menck, E. C. Miracca, C. Y. Miyaki, C. B. Monteiro-Vitorello, D. H. Moon, M. A. Nagai, A. L. T. O. Nascimento, L. E. S. Netto, A. Nhani, Jr., F. G. Nobrega, L. R. Nunes, M. A. Oliveira, M. C. de Oliveira, R. C. de Oliveira, D. A. Palmieri, A. Paris, B. R. Peixoto, G. A. G. Pereira, H. A. Pereira, Jr., J. B. Pesquero, R. B. Quaggio, P. G. Roberto, V. Rodrigues, A. J. de M. Rosa, V. E. de Rosa, Jr., R. G. de Sá, R. V. Santelli, H. E. Sawasaki, A. C. R. da Silva, A. M. da Silva, F. R. da Silva, W. A. Silva, Jr., J. F. da Silveira, M. L. Z. Silvestri, W. J. Siqueira, A. A. de Souza, A. P. de Souza, M. F. Terenzi, D. Truffi, S. M. Tsai, M. H. Tsuhako, H. Vallada, M. A. Van Sluys, S. Verjovski-Almeida, A. L. Vettore, M. A. Zago, M. Zatz, J. Meidanis, and J. C. Setubal. 2000. The genome sequence of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Nature 406:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studholme, D. J., J. A. Downie, and G. M. Preston. 2005. Protein domains and architectural innovation in plant-associated proteobacteria. BMC Genomics 6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang, L. H., L. X. Weng, Y. H. Dong, and L. H. Zhang. 2004. Specificity and enzyme kinetics of the quorum-quenching N-acyl homoserine lactone lactonase (AHL-lactonase). J. Biol. Chem. 279:13645-13651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu, C., W. Shi, and B. P. Rosen. 1996. The chromosomal arsR gene of Escherichia coli encodes a trans-acting metalloregulatory protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:2427-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]