Abstract

The immune and nervous systems display considerable overlap in their molecular repertoire. Molecules originally shown to be critical for immune responses also serve neuronal functions that include normal brain development, neuronal differentiation, synaptic plasticity, and behavior. We show here that FcγRIIB, a low-affinity immunoglobulin G Fc receptor, and CD3 are involved in cerebellar functions. Although membranous CD3 and FcγRIIB are crucial regulators on different cells in the immune system, both CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB are expressed on Purkinje cells in the cerebellum. Both CD3ɛ-deficient mice and FcγRIIB-deficient mice showed an impaired development of Purkinje neurons. In the adult, rotarod performance of these mutant mice was impaired at high speed. In the two knockout mice, enhanced paired-pulse facilitation of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses was shared. These results indicate that diverse immune molecules play critical roles in the functional establishment in the cerebellum.

Some molecules originally shown to be critical for immune responses, such as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules, CD3ζ, and semaphorin 7A (3, 8, 15, 23), also serve neuronal functions. Based on studies of mutant mice, CD3ζ proved critical for the development of lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) and long-term synaptic plasticity in the adult hippocampus (3, 8).

In the immune system, CD3 subunits are expressed on T cells. The T-cell receptor (TCR)-CD3 complex recognizing specific antigens bound to MHC present on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) is composed of a TCR heterodimer and CD3 polypeptides organized as dimers. The cell-cell interaction between APCs and T cells is known as an immunological synapse (5) in the mature immune system. In αβ T cells, when the TCR interacts with the antigen/MHC complex, it transmits information to a signal-transducing complex consisting of two CD3 subunit dimers, CD3ɛ-CD3γ and CD3ɛ-CD3δ, and the CD3ζ-CD3ζ homodimer (10). Among CD3 subunits, CD3ζ is a crucial subunit having three immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), whereas the remaining subunits have one ITAM (25). Tyrosine residues within these motifs are phosphorylated by src family tyrosine kinases, and then Src homology 2-containing proteins, including the tyrosine kinase ZAP70, participate in signaling (13). The signaling in γδ TCRs is different from that in αβ TCRs. Most γδ TCRs lack CD3δ, and signal transduction by γδ TCR is superior to that by αβ TCR, as measured by its ability to induce calcium mobilization, extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation, and cellular proliferation (6).

FcγRIIB is a low-affinity membrane receptor for immune complexes broadly distributed on hematopoietic cells, such as B cells, mast cells, basophils, macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and Langerhans cells. FcγRIIB negatively regulates B-cell receptor-induced signaling in B cells via the inhibitory immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif in its cytoplasmic domain (24, 30). Coengagement of the B-cell receptor and FcγRIIB results in the tyrosine phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif and the recruitment of SHIP. SHIP, by hydrolyzing PIP3, causes the dissociation of Brutons tyrosine kinase from the membrane and the inhibition of calcium influx into the cell (29). Although the functional significance of FcγRIIB has been elucidated in hematopoietic cells, the physiological roles of FcγRIIB have not been explored in the nervous system.

The cerebellum is a key region operating motor learning and motor coordination. Cerebellar functions are regulated by coordinated neural networks. There are two major types of inputs to the cerebellum: climbing fibers (CFs) and mossy fibers. CFs are the axons of neurons located in the inferior olive. They enter the cerebellum and establish two branches, one to the deep nuclei and one to the Purkinje cells (PCs) of the cerebellar cortex. Mossy fibers synapse with the claw-like dendrites of the granule cells (GCs) in the cerebellar cortex. The GCs in turn communicate with the PC dendrites via their long parallel fiber (PF) axons. PC axons are the sole efferents from the cerebellar cortex.

Here, we found an unexpected common functional significance of CD3 and FcγRIIB in the cerebellum. Both CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB are located on Purkinje cells. CD3ɛ-deficient mice and FcγRIIB-deficient mice shared impaired development of Purkinje neurons, enhanced paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses, and poor rotarod performance at high speed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

CD3ɛ knockout mice (16) with a C57BL/6 background were obtained from The European Mouse Mutant Archive. FcγRIIB knockout mice (30) with a C57BL/6 background were obtained from T. Takai (Tohoku Univ.). All animals were maintained according to the guidelines of Juntendo University.

RT-PCR.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was done using total RNA derived from the cerebellum and EL4 T-cell line and the following primers: CD3ɛ forward, 5′-AAGTCGAGGACAGTGGCTACTAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-CATCAGCAAGCCCAGAGTGATACA-3′; CD3γ forward, 5′-ATGGAGCAGAGGAAGGGTCTGGCT-3′, and reverse, 5′-CATTCTGTAATACACTTGCAGGGG-3′; CD3δ forward, 5′-GGAACAAATGTTGCTTGTCTGG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCTTGGCAAACAGCAGTCGTA-3′; CD3ζ forward, 5′-AAGATGGCAGAAGCCTACAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-TTAATGACACAATGACCTTGC-3′; CD3ζ forward 5′-ACCCCAACCAGCTCTACAATGAG-3′, and reverse, 5′-AAGACGCTGGCACAGGATTGGCTA-3′. Primers for β-actin were purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA).

Immunofluorescence staining.

Immunofluorescence staining of the mouse cerebellum at postnatal day 21 (P21) was done essentially as described previously (20). The primary antibodies included anti-FcγRIIB (22), anti-CD3ɛ (145-2C11), anti-carbonic anhydrase 8 (Car8), anti-GLAST (26), anti-VGLUT1 (18), Alexa Fluor 488-labeled anticalbindin (Swant, Bellinzona, Switzerland), and Alexa Fluor 647-labeled anti-NeuN (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) antibodies. Anti-Car8 antibody was produced in the rabbit and guinea pig against 33 to 61 amino acid residues of the mouse Car8 (BC010773), and the specificity will be published elsewhere. Labeled sections were visualized with a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM510). Quantitation of the pixel intensity of vGluT1 signals was carried out using Adobe PhotoShop and NIH Image.

Behavior.

The performance on the rotarod (Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy) was measured with a maximal observation time of 5 min. Animals were tested at a constant 5, 8, 10, or 30 rpm or an accelerating speed for two consecutive days, receiving four trials per day. The acceleration was started (2 rpm and the rod was rotating at ∼30 rpm after 300 s), and the latency to fall was recorded.

Ambulation counts were made in an open field for 3 min essentially as described elsewhere (9). The behavioral tests were performed in a blind fashion.

Electrophysiology.

Parasagittal cerebellar slices (200 μm) of the vermis were prepared from wild-type, FcγRIIB-deficient, and CD3ɛ-deficient mice (7). Slices were incubated at room temperature (25°C) for at least 1 h before recording. Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were made of Purkinje cells visually identified at room temperature. The preparation was continuously superfused with an extracellular solution containing 124 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3 and 20 mM glucose, which was bubbled continuously with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Patch pipettes had a resistance of 3 to 4 MΩ in the intracellular solution containing 135 mM Cs-d-gluconate, 15 mM CsCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EGTA (pH 7.3). Picrotoxin (50 μM) was always present in the saline to block spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents. To evoke PF or CF excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) from voltage-clamped Purkinje cells (−80 mV or 10 mV, respectively), square pulses (10 μs; 20 to 100 μA) were delivered every 10 s through a glass pipette with a tip 5 to 10 μm in diameter filled with 140 mM NaCl and 10 mM HEPES. To monitor the access resistance, a hyperpolarizing pulse (−10 mV; 50 ms) was applied 400 ms before the extracellular stimulation. Signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 4 kHz (Digidata 1320).

Statistics.

Statistical significance was assessed using Student's t test unless otherwise noted. Analysis of variance was used for further analysis, and if there were significant differences, the Bonferroni test was used for post hoc analysis.

RESULTS

Expression of CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB in the developing cerebellum.

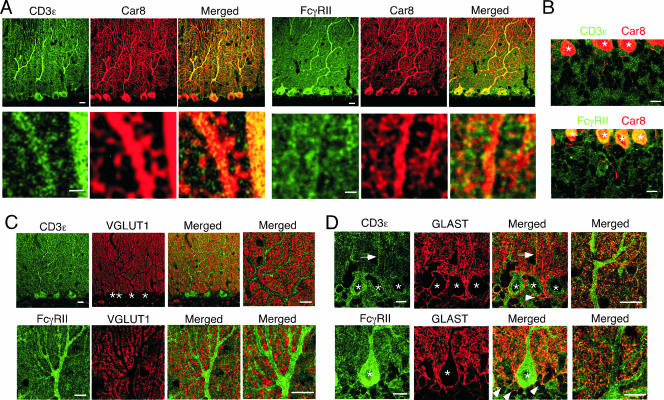

We examined the distributions of CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB proteins in the mouse cerebellum at P21 by double immunofluorescence using cellular and subcellular markers. CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB proteins were distributed widely in the cerebellar cortex (Fig. 1). The most intense staining of CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB was found in perikarya and dendritic shafts of PCs, because each immunostaining showed considerable overlap with Car8 (Fig. 1A and B), a molecule known to be exclusive in PCs and responsible for ataxic mutant Waddles mice (11, 12). At a higher magnification, CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB were also detected in Car8-labeled dendritic spines of PCs (Fig. 1A, lower panels). Outside Car8-labeled PC elements, CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB were also distributed at low to moderate levels. To address these cellular elements, we used VGLUT1 and GLAST as a marker for parallel fiber terminals and Bergmann glia, respectively. Little, if any, CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB were detected in VGLUT1-labeled parallel fiber terminals (Fig. 1C), whereas they were found in GLAST-positive cell bodies and processes of Bergmann glia (Fig. 1D). A slight difference was also found in that CD3ɛ was detected in both Bergmann fibers (i.e., rod-like staining) (Fig. 1D) and lamellate processes (reticular staining in the neuropil), while FcγRIIB was preferentially seen in lamellate processes. Therefore, CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB are coexpressed in PCs and Bergmann glia in the cerebellar cortex.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB in the cerebellum. Double immunofluorescence images are shown for CD3ɛ (green) or FcγRIIB (green) with Car8 (red) (A and B) in the molecular layer (A) and internal granular layer (B), with VGLUT1 (red) (C), or with GLAST (red) (D) in the cerebellum at P21. Arrows and arrowheads indicate rod-like staining of the Bergmann glia and the GLAST-positive cell bodies, respectively. Asterisks, Purkinje cell somata. Bars, 1 μm (A, lower panels) or 10 μm (A, upper panels, and B, C, and D).

Impaired cerebellar architecture in both CD3ɛ-deficient and FcγRIIB-deficient mice during development.

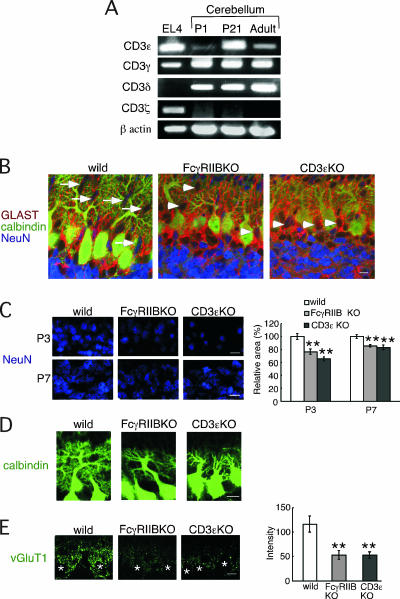

In T cells, all CD3 subunits are assembled in the TCR-CD3 complex. The current model of TCR-CD3 signaling in T cells assumes coordinated regulation by all CD3 subunits. Phosphorylation of the ITAMs in CD3ζ is a critical step for actin polymerization, whereas the remaining CD3 subunits also participate in the signaling (5, 13). Therefore, we examined if the CD3 signaling machinery is established in the cerebellum. CD3γ and CD3δ transcripts were also found in the cerebellum at developmental stages. In contrast, CD3ζ mRNA was not detected at any stages of development using two sets of CD3ζ-specific primers (Fig. 2A), indicating that CD3 signaling components, such as CD3ɛ, CD3γ, and CD3δ, exist in the cerebellum, whereas the CD3 signaling seems to differ in the cerebellum from that in the immune system. Furthermore, CD3ɛ was preferentially expressed in the developmental stages. The CD3ɛ mRNA level was highest at P21. Therefore, we asked whether CD3ɛ and FcγRIIB contribute to the formation of neuronal architecture during development. We used two mutant mice, FcγRIIB-deficient mice and CD3ɛ-deficient mice, in which CD3δ is also not detected and the CD3γ protein level is reduced (16).

FIG. 2.

Impaired neuronal architecture in FcγRIIB-deficient and CD3ɛ-deficient mice during cerebellar development. (A) RT-PCR analysis of each CD3 subunit in the EL4 T-cell line and the cerebellum from C57BL/6 mice at P1, P21, and the adult stage. β-Actin was used as the internal control. (B) Triple immunofluorescence for GLAST (red), calbindin (green), and NeuN (blue) at P7. Arrows and arrowheads indicate migrating GCs with an ellipsoidal shape and those with a round shape, respectively. (C) Immunofluorescence for NeuN at P3 and P7. The relative area occupied by granule cells was quantitatively compared. (D) Immunofluorescence for calbindin at P7. (E) The pixel intensity of VGLUT1 immunofluorescence was quantitatively compared. The left panel shows representative examples of immunofluorescence staining with anti-vGluT1 antibody at P7. The images were taken at the same exposure. Asterisks, Purkinje cell somata. Bars, 10 μm.

In the control mice, migrating NeuN-positive GCs with an ellipsoidal shape were observed at P7, whereas in the two mutant mice, these cells were round (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, when we quantified the area filled by GCs in IGL, a reduction was observed in the two knockout mice at both P3 and P7 (Fig. 2C). We then examined the development of PC dendrites. At P7, the size of the dendritic arbor and degree of branching of PCs were reduced in the two knockout mice compared to the control mice, as verified by calbindin staining (Fig. 2D). GCs extend PFs, and as the PFs extend, they make synaptic contact with the forming PC dendritic arbors. Synaptic terminals of PFs can be detected with anti-VGLUT1 antibody. In both mutant mice, the intensity of VGLUT1 signal was reduced at P7 (Fig. 2E).

CD3 and FcγRIIB have a common role in PF-PC synaptic function.

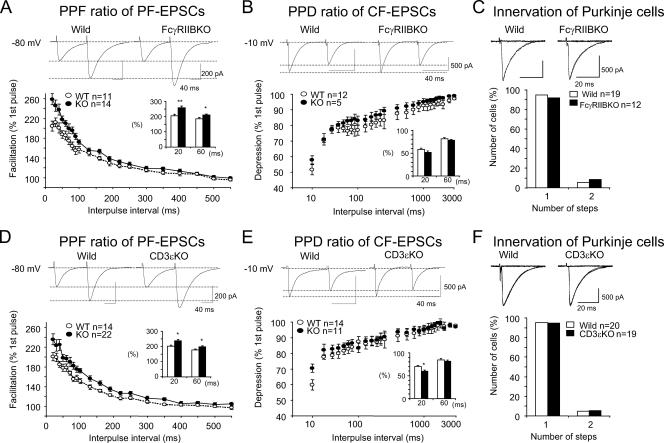

Given the impaired development of PCs in the two mutant mice, we investigated whether these two molecules have common roles in synaptic functions in the adult by using electrophysiological approaches. We examined EPSCs in response to the stimulation of PFs or CFs in 8- to 10-week slice preparations by whole-cell patch clamping. There was no statistically significant difference in passive membrane properties between wild-type and FcγRIIB-deficient PCs (data not shown). Basal transmission at PF-PC and CF-PC synapses was not significantly altered; there was no significant difference in either the rise or decay time constants of EPSCs between wild-type and FcγRIIB-deficient mice (Table 1). To investigate short-term synaptic plasticity, PPF at PF-PC synapses and paired-pulse depression (PPD) at CF-PC synapses were investigated by administering pairs of PF or CF stimuli at different interstimulus intervals. The PPF ratio was significantly increased in FcγRIIB-null slices when the interpulse interval was 20 to 220 ms: the PPF ratio at an interpulse interval of 20 ms was 205 ± 10% (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) in wild-type mice and 259 ± 11% in FcγRIIB-deficient mice (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the PPD ratio was not significantly changed in FcγRIIB-deficient mice at interpulse intervals ranging from 20 to 3,000 ms (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 1.

Basic properties of CF and PF EPSCsa

| Synapse type | 10-90% rise timeb (ms)

|

Decay time constantc (ms)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | FcγRIIB KO | CD3ɛ KO | Wild type | FcγRIIB KO | CD3ɛ KO | |

| CF EPSC | 0.5 ± 0.1 (12) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (15) | 0.5 ± 0.1 (11) | 14.1 ± 3.2 (12) | 13.5 ± 3.6 (15) | 12.7 ± 3.9 (11) |

| PF EPSC | 2.7 ± 0.6 (15) | 2.8 ± 0.7 (15) | 2.7 ± 0.7 (15) | 22.1 ± 5.5 (15) | 22.5 ± 6.2 (15) | 23.4 ± 5.7 (15) |

Data represent means ± standard deviations; n is reported in parentheses. KO, knockout.

The time required for the synaptic current to increase from 10% to 90%.

Current decay was fitted to single exponential curves.

FIG. 3.

Enhancement of PPF at PF-PC synapses in FcγRIIB-deficient and CD3ɛ-deficient mice. Short-term synaptic plasticity at PF- and CF-PC synapses was examined by applying pairs of stimuli separated by 20 to 550 ms or 20 to 3,000 ms. The second response (expressed as a percentage of the response to the first pulse; mean ± SEM) is plotted as a function of the interpulse interval. (A and D) PPF ratios of PF-EPSCs in FcγRIIB-deficient (A) and CD3ɛ-deficient (D) PCs were calculated. PF-EPSCs were obtained by holding membrane potentials at −80 mV. (B and E) PPD ratios of CF-EPSCs in FcγRIIB-deficient (B) and CD3ɛ-deficient (E) mice. (C and F) Single innervation of PCs by CFs in 8- to 10-week-old FcγRIIB-deficient (C) and CD3ɛ-deficient (F) mice. With gradually increasing stimulus intensities applied to the CFs, more than 90% of EPSCs of the wild-type and mutant mice were obtained in an all-or-none fashion. CF-EPSCs were elicited at −10 mV to inactivate voltage-dependent channels. Numbers of tested PCs (n) are indicated in each graph. *, P < 0.05.

Immature PCs are innervated by multiple CFs that originate from the inferior olive of the medulla (4). As animals grow, redundant CFs are gradually eliminated. FcγRIIB-deficient mice had almost the same percentage (more than 90%) of PCs innervated with a single CF as the wild-type mice (Fig. 3C), thus indicating that the developmental elimination of surplus CF synapses on PCs was not impaired in the mutant mice.

Similar to FcγRIIB-deficient mice, the PPF ratio was significantly increased in CD3ɛ-deficient mice, while the PPD ratio was unchanged except at an interpulse interval of 20 ms (Fig. 3D and E). The developmental elimination of surplus CF synapses on PCs was not affected (Fig. 3F).

Poor rotarod performance in FcγRIIB-deficient and CD3ɛ-deficient mice.

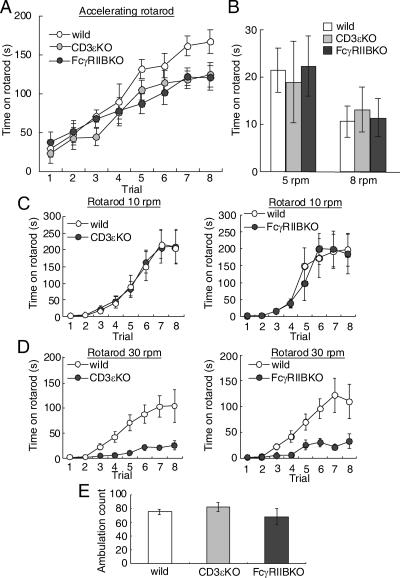

Finally, we assessed motor learning and motor coordination using the rotarod test in the two knockout mice. We first evaluated animals under standard conditions using an accelerating rotarod test (Fig. 4A). Rotarod speed increased from 2 rpm to 30 rpm within 5 min. On the first trial, the latencies at which the two mutant mice fell did not differ from those in the control mice. In all three strains, the latencies increased gradually as they gained experience (analysis of variance, F7, 191 = 53.2; P < 0.0001). As a whole, a strain effect did not reach a significant level (F2, 191 = 2.3; P = 0.12). However, the efficiency of improvements in the two mutant mice was lower in the latter four trials. During the first four trials, there was not a significant strain effect (F2, 95 = 0.61; P = 0.55). However, during the later four trials, a strain effect became evident (F2, 95 = 7.0; P = 0.005). Therefore, we hypothesized that the motor coordination evaluated in the first trial might not be changed, whereas the rising curve of the latency might be changed in the two mutant mice.

FIG. 4.

Poor rotarod performance in FcγRIIB-deficient and CD3ɛ-deficient mice at high speed. (A) Amount of time mice remained on an accelerating rotarod over eight trials (n = 8 in each). (B) Amount of time mice remained on the rotarod at a constant 5 rpm or 8 rpm on the first trial (n = 8 in each). (C and D) Amount of time mice remained on the rotarod at a constant 10 rpm (n = 8 in each) (C) or 30 rpm (n = 7 in each) (D) over eight trials. (E) Ambulation count in the open field during 3 min (n = 6 to 7). Error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

To confirm the hypothesis, we measured the latency in the first trial with constant rotarod speed. There were not significant differences at either 5 rpm or 8 rpm (F2, 23 = 0.08 [P = 0.93] and F2, 23 = 0.12 [P = 0.89], respectively) (Fig. 4B).

We next evaluated the rising curve of the latency at constant rotarod speed. When FcγRIIB-deficient and CD3ɛ-deficient mice were tested at a constant 10 rpm, they performed similarly to control mice (F1, 103 = 0.02 [P = 0.90] and F1, 111 = 0.02 [P = 0.89], respectively) (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the latencies were significantly shorter in the FcγRIIB-deficient and CD3ɛ-deficient mice at 30 rpm (F1, 127 = 28.7 [P = 0.0001] and F1, 127 = 20.1 [P = 0.0005], respectively) (Fig. 4D). General motor activities in the two mutant mice, as evaluated by ambulation count in the open field, were not significantly changed (F2, 21 = 0.98, P = 0.39) (Fig. 4E). Thus, the rotarod performance was impaired at high speed.

DISCUSSION

In the present investigation, both CD3ɛ-deficient and FcγRIIB-deficient mice showed an increased PPF ratio in PF-PC synapses. PPF is an event characteristic of synapses with low release probability of a neurotransmitter. As the PF terminals mature, the release probability is increased, resulting in a decrease in the PPF ratio. Thus, an increased PPF in CD3ɛ-deficient and FcγRIIB-deficient mice indicates a lowered release probability of PF terminals. In these mutant mice, rotarod performances were worse only at high speed. The motor learning ability of these two mutant mice did not seem to be affected, because there were no differences at a low rotarod speed. In the FcγRIIB-deficient mice, robust long-term depression was induced following conjunctive stimulation of PFs with PC depolarization in the cerebellum (data not shown), which might reflect the selective impairment in rotarod tasks. In the two mutant mice, the upper limit of learning capacity might be lowered. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the mutant mice have difficulty in gripping the rotarod at high speed. Interestingly, similar impairments, poor rotarod performance and mild enhancement of the PPF ratio in PF-PC synapses, were also seen in mutant mice deprived of Munc13-3, a component of presynaptic active zones (2). Further studies are needed to determine whether poor rotarod performance is associated with modification of PF-PC synaptic functions in these mutant mice.

We found impaired architectures of PCs and GCs during development in the two mutant mice. The two molecules are expressed on the somata, dendrites, and spines of PCs. Lack of either of the two molecules on PCs might intrinsically contribute to the impaired development of PC dendrites. Presynaptic terminals of PFs make synaptic contacts with PC dendrites, and PFs exert instructive roles in the development of distal PC dendrites and in the planar organization of dendritic arbors. We found lesser VGLUT1 signals in the two mutant mice. Therefore, the immature GC might also contribute to the impaired PC dendrites.

The two molecules were also found on the Bergmann glia. An increasing body of evidence suggests the participation of Bergmann glia in the development of cerebellar neurons as a scaffold for the migration and positioning of cerebellar neurons (31). It is also possible that the two molecules on the Bergmann glia influenced the development of cerebellar neurons. However, the size of cultured astrocytes from the two mutant mice was not essentially altered compared to the control mice (data not shown).

We describe a role of immune molecules in the cerebellum in vivo. In the immune system, the two molecules are expressed in different immune cells. CD3ɛ is exclusively expressed on T cells, where the TCR-CD3 complex recognizes specific antigens bound to MHC on APCs and forms immunological synapses. Among CD3 subunits, roles of CD3ζ in the brain have been studied in vivo. CD3ζ is expressed in neurons, such as the LGN and hippocampus (3, 8). In CD3ζ mutant mice, refinement of connections between the retina and central targets during development was incomplete. These results indicate a crucial role for CD3ζ in functional weakening and structural retraction of synaptic connections in the LGN and hippocampus (3, 8). On the other hand, we showed unexpected roles of CD3ɛ, -γ, and/or -δ in the cerebellum because we used CD3ɛ-deficient mice, in which CD3δ is also not detected, and the CD3γ protein level was reduced (16). Our results and those with CD3ζ mutant mice suggest that the ligand for CD3 subunits exists in the brain. It remains elusive whether a common molecule acts as a ligand for both CD3ζ and other CD3 subunits. Recently, paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B (PirB), an MHC class I receptor, was found to be expressed in subsets of neurons throughout the brain, and in mutant mice lacking functional PirB, cortical ocular dominance plasticity is more robust at all ages (27). Although antigen/MHC complex is the ligand of the TCR-CD3 complex in T cells, it seems to be unlikely that MHC antigen is a ligand for CD3ɛ, -γ, and/or -δ in the cerebellum, because mice lacking surface expression of MHC class I and MHC class II knockout mice performed normally in a rotarod test (data not shown), and the TCRα transcript was not detected in the brain (21, 28). Unlike in the LGN and hippocampus, CD3ζ is absent in the cerebellum. The current model of TCR-CD3 signaling in T cells assumes phosphorylation of the ITAMs in CD3ζ and subsequent involvement of several molecules, such as ZAP-70, SLP76, Vav, Nck, and WASP, for actin polymerization (13). Therefore, other molecules might associate with CD3ɛ, -γ, and/or -δ in the cerebellum. FcRγ was a candidate because it has an ITAM and is included in the CD3 complex in T cells in the intestine of CD3ζ knockout mice (14, 17). However, the performances of FcRγ knockout mice in the rotarod test were comparable with those of control mice (data not shown). Rather, ITAM-independent signaling would function in the cerebellum.

FcγRIIB shows a different pattern of expression than CD3 in the immune system. FcγRIIB is broadly distributed on hematopoietic cells (29) but not on mature T cells. In immune cells, it inhibits various cellular functions, such as B-cell activation, antigen presentation, cell proliferation, and antibody production (29). FcγRIIB might also reduce the development of autoimmune disease. The lack of FcγRIIB enhanced susceptibility to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-induced autoimmune experimental allergic encephalitis and increased the extent of demyelination (1). Thus, the functions of FcγRIIB are different from those of CD3 in the immune system. In contrast, we demonstrated a common physiological role of the two molecules in the development of the cerebellum. FcRγ, another immunoglobulin G Fc receptor subunit, is pivotal to the differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells into myelinating oligodendrocytes (19). Therefore, the roles of immunoglobulin G Fc receptors in the development of the brain are diverse. Further studies will elucidate the neuron-specific signaling of FcγRIIB and CD3.

Acknowledgments

FcγRIIB knockout mice were kindly provided by T. Takai (Tohoku University).

We declare that none of the authors has financial interests.

This work was supported in part by research grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Technology, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdul-Majid, K. B., A. Stefferl, C. Bourquin, H. Lassmann, C. Linington, T. Olsson, S. Kleinau, and R. A. Harris. 2002. Fc receptors are critical for autoimmune inflammatory damage to the central nervous system in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Scand. J. Immunol. 55:70-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustin, I., S. Korte, M. Rickmann, H. A. Kretzschmar, T. C. Sudhof, J. W. Herms, and N. Brose. 2001. The cerebellum-specific Munc13 isoform Munc13-3 regulates cerebellar synaptic transmission and motor learning in mice. J. Neurosci. 21:10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corriveau, R. A., G. S. Huh, and C. J. Shatz. 1998. Regulation of class I MHC gene expression in the developing and mature CNS by neural activity. Neuron 21:505-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crepel, F., J. Mariani, and N. Delhaye-Bouchaud. 1976. Evidence for a multiple innervation of Purkinje cells by climbing fibers in the immature rat cerebellum. J. Neurobiol. 7:567-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dustin, M. L., and J. A. Cooper. 2000. The immunological synapse and the actin cytoskeleton: molecular hardware for T cell signaling. Nat. Immunol. 1:23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes, S. M., and P. E. Love. 2002. Distinct structure and signaling potential of the gamma delta TCR complex. Immunity 16:827-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirai, H., T. Launey, S. Mikawa, T. Torashima, D. Yanagihara, T. Kasaura, A. Miyamoto, and M. Yuzaki. 2003. New role of δ2-glutamate receptors in AMPA receptor trafficking and cerebellar function. Nat. Neurosci. 6:869-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huh, G. S., L. M. Boulanger, H. Du, P. A. Riquelme, T. M. Brotz, and C. J. Shatz. 2000. Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. Science 290:2155-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichihara, K., T. Nabeshima, and T. Kameyama. 1993. Dopaminergic agonists impair latent learning in mice: possible modulation by noradrenergic function. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 264:122-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs, H. 1997. Pre-TCR/CD3 and TCR/CD3 complexes: decamers with differential signalling properties? Immunol. Today 18:565-569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiao, Y., J. Yan, Y. Zhao, L. R. Donahue, W. G. Beamer, X. Li, B. A. Roe, M. S. Ledoux, and W. Gu. 2005. Carbonic anhydrase-related protein VIII deficiency is associated with a distinctive lifelong gait disorder in waddles mice. Genetics 171:1239-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato, K. 1990. Sequence of a novel carbonic anhydrase-related polypeptide and its exclusive presence in Purkinje cells. FEBS Lett. 271:137-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, J., and A. Weiss. 2001. T cell receptor signalling. J. Cell Sci. 114:243-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, C. P., R. Ueda, J. She, J. Sancho, B. Wang, G. Weddell, J. Loring, C. Kurahara, E. C. Dudley, A. Hayday, et al. 1993. Abnormal T cell development in CD3-ζ−/− mutant mice and identification of a novel T cell population in the intestine. EMBO J 12:4863-4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loconto, J., F. Papes, E. Chang, L. Stowers, E. P. Jones, T. Takada, A. Kumanovics, K. Fischer Lindahl, and C. Dulac. 2003. Functional expression of murine V2R pheromone receptors involves selective association with the M10 and M1 families of MHC class Ib molecules. Cell 112:607-618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malissen, M., A. Gillet, L. Ardouin, G. Bouvier, J. Trucy, P. Ferrier, E. Vivier, and B. Malissen. 1995. Altered T cell development in mice with a targeted mutation of the CD3-epsilon gene. EMBO J. 14:4641-4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malissen, M., A. Gillet, B. Rocha, J. Trucy, E. Vivier, C. Boyer, F. Kontgen, N. Brun, G. Mazza, E. Spanopoulou, et al. 1993. T cell development in mice lacking the CD3-zeta/eta gene. EMBO J 12:4347-4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazaki, T., M. Fukaya, H. Shimizu, and M. Watanabe. 2003. Subtype switching of vesicular glutamate transporters at parallel fibre-Purkinje cell synapses in developing mouse cerebellum. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17:2563-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakahara, J., K. Tan-Takeuchi, C. Seiwa, M. Gotoh, T. Kaifu, A. Ujike, M. Inui, T. Yagi, M. Ogawa, S. Aiso, T. Takai, and H. Asou. 2003. Signaling via immunoglobulin Fc receptors induces oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation. Dev. Cell 4:841-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura, M., K. Sato, M. Fukaya, K. Araishi, A. Aiba, M. Kano, and M. Watanabe. 2004. Signaling complex formation of phospholipase Cβ4 with metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1α and 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor at the perisynapse and endoplasmic reticulum in the mouse brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20:2929-2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishiyori, A., Y. Hanno, M. Saito, and Y. Yoshihara. 2004. Aberrant transcription of unrearranged T-cell receptor beta gene in mouse brain. J Comp. Neurol. 469:214-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ono, M., H. Okada, S. Bolland, S. Yanagi, T. Kurosaki, and J. V. Ravetch. 1997. Deletion of SHIP or SHP-1 reveals two distinct pathways for inhibitory signaling. Cell 90:293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasterkamp, R. J., J. J. Peschon, M. K. Spriggs, and A. L. Kolodkin. 2003. Semaphorin 7A promotes axon outgrowth through integrins and MAPKs. Nature 424:398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravetch, J. V., A. D. Luster, R. Weinshank, J. Kochan, A. Pavlovec, D. A. Portnoy, J. Hulmes, Y. C. Pan, and J. C. Unkeless. 1986. Structural heterogeneity and functional domains of murine immunoglobulin G Fc receptors. Science 234:718-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reth, M. 1989. Antigen receptor tail clue. Nature 338:383-384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibata, T., K. Yamada, M. Watanabe, K. Ikenaka, K. Wada, K. Tanaka, and Y. Inoue. 1997. Glutamate transporter GLAST is expressed in the radial glia-astrocyte lineage of developing mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 17:9212-9219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syken, J., T. Grandpre, P. O. Kanold, and C. J. Shatz. 2006. PirB restricts ocular-dominance plasticity in visual cortex. Science 313:1795-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syken, J., and C. J. Shatz. 2003. Expression of T cell receptor beta locus in central nervous system neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13048-13053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takai, T. 2002. Roles of Fc receptors in autoimmunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:580-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takai, T., M. Ono, M. Hikida, H. Ohmori, and J. V. Ravetch. 1996. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. Nature 379:346-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada, K., M. Fukaya, T. Shibata, H. Kurihara, K. Tanaka, Y. Inoue, and M. Watanabe. 2000. Dynamic transformation of Bergmann glial fibers proceeds in correlation with dendritic outgrowth and synapse formation of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J. Comp. Neurol. 418:106-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]