Abstract

Immune responses to Chlamydia trachomatis underlay both immunity and immunopathology. Immunopathology in turn has been attributed to chronic persistent infection with persistence being defined as the presence of organisms in the absence of replication. We hypothesized that dendritic cells (DCs) play a central role in Chlamydia immunity and immunopathology by favoring the long-term survival of C. muridarum. This hypothesis was examined based on (i) direct staining of Chlamydia in infected DCs to evaluate the development of inclusions, (ii) titration of infected DCs on HeLa cells to determine cultivability, and (iii) transfer of Chlamydia-infected DCs to naive mice to evaluate infectivity. The results show that Chlamydia survived within DCs and developed both typical and atypical inclusions that persisted in a subpopulation of DCs for more than 9 days after infection. Since the cultivability of Chlamydia from DCs onto HeLa was lower than that estimated by the number of inclusions in DCs, this suggests that the organisms may be in state of persistence. Intranasal transfer of long-term infected DCs or DCs purified from the lungs of infected mice caused mouse lung infection, suggesting that in addition to persistent forms, infective Chlamydia organisms also developed within chronically infected DCs. Interestingly, after in vitro infection with Chlamydia, most DCs died. However, Chlamydia appeared to survive in a subpopulation of DCs that resisted infection-induced cell death. Surviving DCs efficiently presented Chlamydia antigens to Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells, suggesting that the bacteria are able to both direct their own survival and still allow DC antigen-presenting function. Together, these results raise the possibility that Chlamydia-infected DCs may be central to the maintenance of T-cell memory that underlies both immunity and immunopathology.

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection, with over 90 million new infections occurring annually worldwide (6, 47). The disease is a major public health concern because of its adverse effects on reproduction (6, 47). The developmental cycle of Chlamydia includes two forms: an elementary body (EB) and a reticulate body (RB). EBs are taken up by mucosal epithelial cells and transform into RBs that divide by binary fission, resulting in inclusion formation. Within inclusions, RBs mature and transform into EBs that, after release, infect new cells. The developmental cycle normally takes between 48 and 72 h (18). A third developmental form—the persistent stage—is considered to be a mechanism of survival under conditions of stress (4, 20). Persistent forms develop in response to alterations in cell culture, including amino acid or iron deprivation (10, 41) and the presence of antibiotics (9) or cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (2). Although the various persistent forms appear to be morphologically similar, they may be different functionally. For example, synthesis of various cysteine-rich proteins is affected in penicillin-induced persistent forms, while expression of major outer membrane protein (MOMP) is minimally affected (43). In IFN-γ-induced persistence, on the other hand, expression of MOMP is markedly affected, but not that of heat shock protein 60 (HSP60), a property that may be associated with pathogenesis (4, 31). Persistent Chlamydia displays an atypical “aberrant” morphology and is normally noninfectious and noncultivable, although the bacteria remain metabolically active (3).

Although persistent Chlamydia has not been directly demonstrated in vivo, these forms have been implicated in various disease sequelae related to infertility (38), abortion (37), scarring trachoma (21), and reactive arthritis (33). Survival of persistent Chlamydia has been inferred by the detection of chlamydial nucleic acids or antigens, but bacteria have not been isolated in tissue culture from infected tissue (37). The factors that favor the generation and survival of persistent forms of Chlamydia in vivo are not known. Analysis of tissue from the endometrium of chronically infected animals demonstrated that the bacteria localize in the basal stroma beneath epithelial endometrial cells, in contact with plasma cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes (8, 37). It has been speculated that the bacteria may reside in tissue DCs and/or tissue macrophages (Mφ) (37).

The available evidence is mixed as to whether Mφs provide a sanctuary for long-term survival of Chlamydia. In vitro analysis has shown that Mφ may not support the long-term survival of C. trachomatis. Although bacterial nucleic acids or antigens were detected in human infected Mφs or human monocytes various days after infection, infectious bacteria could not be recovered from these cells (23, 48). Furthermore, in human alveolar Mφs the bacteria were detected for only 48 h after infection (32). Mφs may better support persistence or replication of C. pneumoniae. For instance, C. pneumoniae was recovered in HEp-2 cells from CD14+ cells from patients with coronary artery disease who had been treated with azithromycin (16). On the other hand, C. pneumoniae was eradicated from human alveolar Mφs shortly after in vitro infection (46). Lastly, Mφs allow the survival and modest replication of lymphogranuloma venereum strains of C. trachomatis (26, 48).

We hypothesize that DCs are more central to the immunological significance of long-term survival of Chlamydia. DCs are key components of the immune system. DCs potently prime naive T cells and are the initiators of either immunity, tolerance, or immunopathology (1, 13). Due to their unique role in antigen capture, processing and presentation, DCs could support the survival but not the replication of microbes (7, 25). Atypical C. trachomatis inclusions have been observed in distinct vacuoles of human DCs 48 h after in vitro infection (27). In a murine DC cell line (D2SC/1), C. trachomatis EBs were observed in large vacuoles after infection, but bacteria were not detected beyond 24 h (35). In a more recent study, C. trachomatis inclusions were observed in human DCs 48 h after infection (15). Whether DCs support the long-term survival of Chlamydia and whether the surviving bacteria could be a reservoir for long-term Chlamydia infection is unknown.

Here we examined short (less than 3 days) and long-term (6 to 9 days) survival of C. muridarum in DCs. We show that after DC infection Chlamydia develops both typical and atypical inclusions that persist long after infection was initiated, that the frequency of inclusions that developed in DCs was high although EBs derived from the inclusions infected HeLa cells poorly, and that Chlamydia remained infectious to mice after intranasal (i.n.) adoptive transfer of infected DCs. Importantly, Chlamydia surviving in DCs do not appear to subvert DC antigen presentation function to T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM), fetal calf serum (FCS), collagenase type IA and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) were purchased from Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada. Hybridoma X63 producing interleukin-4 (IL-4) was provided by F. Melchers, Basilea Institute, Basel, Switzerland. Lipopolysaccharide was from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. Concentrations of IFN-γ in culture supernatants was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using (R4-6A2 and XMG2.2) antibody pairs (Pharmingen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Mice.

Female, 8- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River (St. Constant, Canada) and kept under pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Facility of the Jack Bell Research Centre. All animal procedures used in the study were approved by the animal care committee of the University of British Columbia.

Chlamydia.

C. muridarum strain Nigg was used in the present study. C. muridarum was grown in HeLa 229 cells in Eagle essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS. EBs were purified from HeLa cells on discontinuous density gradients of Renografin-76 (Squib Canada, Quebec, Canada) as described previously (24). Purified EBs were divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C in a sucrose-phosphate-glutamic acid buffer (SPG). The infectivity of purified EBs was assessed by immunostaining as follows. HeLa cell monolayers were infected with serial dilutions of EBs. Infected HeLa cells were then incubated for 24 to 36 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed in methanol and stained with polyclonal antibodies raised against Chlamydia MOMP (ViroStat, Portland, ME). Determination of inclusion-forming units (IFU) within HeLa cells was carried out by using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody as described previously (24).

Growth of DCs and generation of BM-DCs.

The myeloid DC cell line DC2.4 was grown in RPMI containing 10% FBS as described previously (44). Myeloid bone marrow-derived DCs (BM-DCs) were generated from bone marrow progenitors in vitro by using GM-CSF and IL-4 (22). Briefly, bone marrow cells flushed from the femurs of 8- to 12-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were cultured at 7 × 105 cells/ml in 10-cm bacteriological petri dishes (Falcon). The DC growth media consisted of IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS, 15 ng of GM-CSF/ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10−7 M 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (10 μg/ml), and 5% IL-4 culture supernatant of Hybridoma X63 (see above). Fresh GM-CSF was added to cell cultures at day 4. On day 7, nonadherent cells were harvested and purified with anti-CD11c magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Ltd.). Purities of >98% CD11c+ cells were routinely achieved as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (data not shown).

Isolation of DCs from lungs of Chlamydia-infected mice.

Isolation of lung DCs was carried out as previously described (40). Mice were inoculated i.n with C. muridarum (2,000 IFU). Mice were monitored daily for body weight loss and sacrificed 6 days after infection. The thoracic cavity was opened, and blood was removed by perfusion via administering phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) through the pulmonary artery. Lungs were removed and cut into small pieces, mixed in 0.25% collagenase, and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Digested tissue was passed though a 16-gauge needle and then through a 40-μm-pore-size nylon cell strainer. The single cell suspension was washed three times by brief centrifugation in PBS containing 2% FCS and 2 mM EDTA. Washed cells were then incubated with anti-CD11c magnetic beads and CD11c+ cells were purified by positive selection using a MACS DC isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Ltd.). Purified DCs were washed and resuspended in PBS or SPG buffer for further analysis (see below).

Determination of infection levels and Chlamydia cultivability in DCs and Mφs.

Purified BM-DCs or DC2.4 cells were infected at multiplicities of infection (MOI) of 1 or 3. Infected DCs were incubated at 37°C for various time points. After incubation, infected DCs were either directly immunostained for Chlamydia (as for HeLa cells, see above) or were assessed for cultivability on HeLa cells as follows. After harvesting, DCs were resuspended at 106 cells/ml in SPG buffer and sonicated for 5 s in an Ultrasonic Dismembranator (model 100; Fisher Scientific). The DC homogenates were titrated on HeLa cells, incubated for 36 h, and immunostained with anti-Chlamydia antibodies as described above.

Resident peritoneal Mφs were isolated as described previously (45). Briefly, C57BL/6 female mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The abdomen skin was removed, and mice were inoculated with 5 ml of PBS in the peritoneal cavity. After a gentle massage, cells were aspirated with a 22-gauge needle. The obtained cells were washed in PBS containing 2% FCS, resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS, and then plated on six-well plates at 4 × 106 white blood cells per well. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, nonadherent cells were removed, and adherent cells, predominantly Mφs, were further incubated at 37°C. After 24 h maturation, 106 Mφs were infected with chlamydial EBs (MOIs 1 or 3) and incubated at 37°C. Infected Mφs were stained for the direct detection of chlamydial inclusions or assessed for Chlamydia cultivability as described for BM-DCs (see above).

Intranasal adoptive transfer of DCs after incubation with Chlamydia.

At various time points after in vitro infection with C. muridarum, DCs were harvested and washed in PBS. Cells were resuspended in 40 μl of PBS and transferred i.n. to anesthetized groups of mice. Control mice received either untreated DCs or were inoculated with C. muridarum (2,000 IFU). Mice were monitored daily for body weight loss. The bacterial load in the lungs of infected mice was determined 6 days after infection as follows. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the lungs were aseptically removed. Lung tissue was homogenized in 5 ml of SPG buffer and clarified by brief centrifugation at 300 × g. The cell suspension was then sonicated for 5 s (see above), and the resulting cell lysate was titrated on HeLa cells as described for titration of EBs in HeLa cells (see above).

Confocal microscopy of infected DCs.

DCs were plated onto 12-mm coverslips at 105 cells/coverslip. DCs were infected with C. muridarum (MOI of 3) in IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS. Infected DCs were incubated at 37°C for 48 h and then fixed in IC fixation buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for 30 min. Cells were then washed in permeabilization buffer (eBioscience), blocked for 30 min in 3% rabbit serum, and then incubated with a rabbit antichlamydial MOMP polyclonal antibody (ViroStat). Cells were then stained with a Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA), washed in PBS, and then stained with an anti-mouse CD11c-fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated MAb for 30 min. Inclusions were visualized by confocal microscopy using a 63× objective lens.

Presentation of Chlamydia antigens by infected DCs.

Presentation of Chlamydia antigens by DCs was determined as described previously (34). Briefly, Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells were generated by immunizing 8- to 12-week-old female C57BL/6 mice intraperitoneally with 106 IFU of C. muridarum, and boosting 2 weeks later. Mice were subsequently challenged i.n. with a lethal dose of C. muridarum to ensure mice were protected. Spleens were removed from immune mice and CD4+ T cells purified by using the MACS CD4+ T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotech). As a control, CD4+ T cells from nonimmunized animals were purified in parallel. Chlamydia-specific or control CD4+ T cells (4 × 105 in 100 μl of medium) were cultured with Chlamydia-infected DCs prepared as follows. Freshly purified BM-DCs were incubated with Chlamydia EBs at MOI of 2 for either 2, 6, or 9 days. DCs were then plated in a 96-well dish at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well in 100 μl of IMDM containing 10% FCS. CD4+ T cells and Chlamydia-infected BM-DCs were cocultured at a ratio of 2:1 for 48 h at 37°C. IFN-γ production in cell supernatants was determined by ELISA and used as a measure of Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T-cell recognition.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out by using the Student t test.

RESULTS

Development of inclusions in Chlamydia-infected DCs.

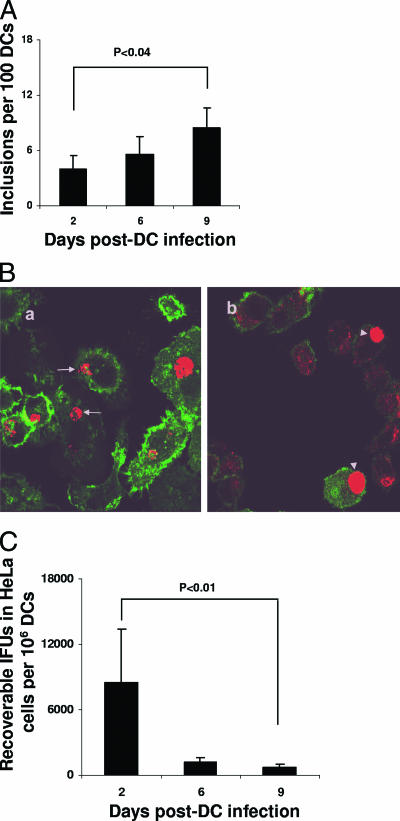

To examine the possibility that Chlamydia survive in DCs, purified BM-DCs or the DC cell line DC2.4 were infected with C. muridarum. After infection, cells were examined for inclusion formation by either immunoperoxidase staining or by confocal microscopy using anti-Chlamydia MOMP antibodies. A minority of Chlamydia-infected BM-DCs developed visible inclusions 2 days after infection, with inclusions persisting for up to 9 days. The (mean ± the standard deviation [SD]) of DCs with inclusions was 3.9% ± 1%, 5.5% ± 1.9%, and 8.5% ± 5.1%, respectively, at days 2, 6, and 9 after infection (Fig. 1A). The modest increase in inclusion numbers observed 9 days after infection compared to 2-day-infected DCs was statistically significant (P < 0.04; Fig. 1A). Confocal microscopy analysis of infected BM-DCs showed that the inclusions appeared atypical and polymorphic and exhibited a fragmented appearance (Fig. 1Ba, arrows). In contrast to the inclusions observed in BM-DCs, inclusions formed in DC2.4 cells were typical, homogeneous, and dense and were similar to those routinely observed in infected HeLa cells (Fig. 1Bb, arrowheads). Of note, analysis of inclusion formation in DC2.4 cells was not possible beyond 2 days since DC2.4 cells undergo apoptosis and die within 72 h after infection (not shown). For further analysis we therefore concentrated on BM-DCs. These results show that Chlamydia developed both typical and atypical inclusions in DCs that persisted long after DC infection was initiated and suggest that the bacteria may survive in both normal and aberrant stages.

FIG. 1.

Survival of Chlamydia in DCs in vitro. (A) BM-DCs (106) were infected with C. muridarum (MOI of 1) and incubated for 2, 6, or 9 days. The level of infection was calculated by averaging the number of inclusions in 10 microscopic fields using a ×20 objective lens and then calculating the inclusion numbers per 100 DCs. BM-DCs or DC cell line DC2.4 were infected (MOI of 1) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. (B) Cells were stained with both fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse CD11c or a combination of anti-Chlamydia MOMP antibody and Cy5 secondary antibodies. Cells were then analyzed with confocal microscopy using ×62 objective lens. a, BM-DCs. Arrows show abnormal inclusions. b, DC2.4 cells. Arrowheads show normal inclusions. (C) Infected (MOI of 1) BM-DCs (106) were sonicated, and cell homogenates were titrated on HeLa cells to determine IFU numbers. Experiments were performed on three (A and C) or two (B) separate occasions with similar results. The results represent mean ± the SD (A and C) of a single experiment.

Low cultivability of Chlamydia isolated from BM-DCs.

To assess growth in vitro, Chlamydia-infected BM-DCs were lysed, and the cell homogenates were titrated on HeLa cells to determine IFU. Isolates from 2-, 6-, or 9-day-infected BM-DCs developed inclusions in HeLa cells (Fig. 1C). Cultivability, however, was remarkably low since IFU derived from 106 BM-DCs, determined 2, 6, or 9 days postinfection, were, respectively, 8,500 ± 4,924, 1,166 ± 472, and 666 ± 305 (mean ± the SD) (Fig. 1C). Growth was lower with an increasing duration of DC infection. A reduction of ∼25-fold in recoverable IFU was observed when we compared 2- versus 9-day-infected DCs (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1C). These results demonstrate that inclusions formed in infected DCs contain poorly cultivable bacteria, suggesting that Chlamydia surviving in DCs may be persistent.

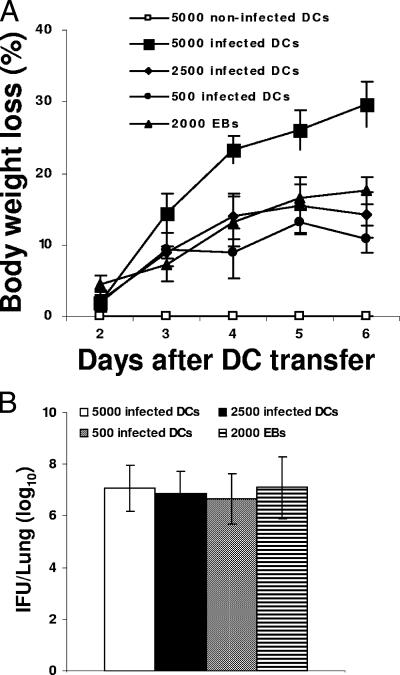

Chlamydia surviving within DCs can infect naive mice.

We next determined whether chlamydiae surviving within DCs were able to infect mice. In preliminary experiments we observed that 2- or 6-day-infected DCs caused lung infection in mice upon i.n. inoculation (data not shown). Since 9-day-infected DCs had extremely low Chlamydia titers of infectivity in HeLa cells (666 ± 305 IFU per 106 BM-DCs [Fig. 1C]), we then tested whether DCs infected for 9 days were infectious to mice. BM-DCs infected in vitro with C. muridarum for 9 days were harvested and administered i.n. to naive mice in doses ranging from 500 to 105 DCs per animal. One group of mice received 105 untreated BM-DCs, and a separate group was inoculated with 2,000 IFU of C. muridarum as a negative or a positive control of infection, respectively. Mice were monitored daily for body weight loss and 6 days later were sacrificed, and the lungs were analyzed to determine bacterial load. All mice groups inoculated with 9-day-infected DCs lost weight in a DC dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, also in a DC dose-dependent manner, cultivable chlamydiae were isolated from their lungs. Thus, 7 × 106 ± 0.9 × 106, 6.8 × 106 ± 0.8 × 106, or 6.6 × 106 ± 1 × 106 IFU per lung were formed on HeLa cells, from mice inoculated, respectively, with 5,000, 2,500, or 500, 9-day-infected BM-DCs (Fig. 2B). Of note, mice inoculated with Chlamydia EBs (2,000 IFU) lost body weight and accumulated 7.1 × 106 ± 1.2 × 106 IFU per lung, whereas mice inoculated with uninfected DCs did not develop disease (Fig. 2). Furthermore, culture media from infected DCs did not infect mice or HeLa cells (results not shown), demonstrating that Chlamydia does not survive extracellularly. Thus, these data show that Chlamydia surviving in DCs is infectious and can cause mouse lung infection. Together, these results suggest that both persistent and infectious forms of Chlamydia organisms are present within chronically infected DCs.

FIG. 2.

Chlamydia surviving in DCs infect naive mice. BM-DCs were infected in vitro with C. muridatrum (MOI of 2) and incubated for 9 days at 37°C. Cells were harvested, and various numbers were transferred i.n. to naive mice. Animals were monitored daily for body weight loss (A), and 6 days after DC transfer the mice were sacrificed and the lung homogenate was titrated on HeLa cells to determine level of bacterial load (B). Experiments were performed on three separate occasions with similar results. The results represent the mean ± the SD from one representative experiment.

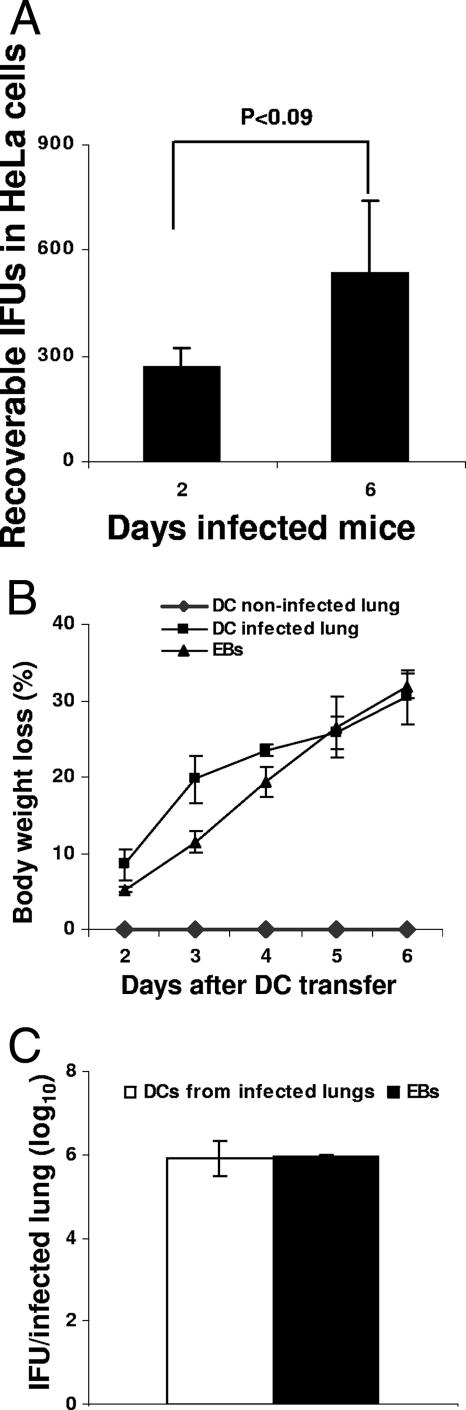

DCs purified from the lungs of Chlamydia-infected mice contain infectious Chlamydia.

We next tested whether DCs isolated from the lungs of infected mice contained cultivable and/or infectious Chlamydia. Mice were infected i.n. with 2,000 IFU of C. muridarum and sacrificed 2 or 6 days later. Lungs were removed, and CD11c+ DCs were purified as indicated in Materials and Methods. Purified DCs were analyzed for the presence of Chlamydia by titration on HeLa cells. DCs purified from the lungs of Chlamydia-infected mice contained viable organisms that grew on HeLa cells. The recoverable IFU in HeLa cells from the total lung population of DCs (106 per time point) purified from 2- and 6-day-infected lungs were, respectively, 266 ± 57 and 533 ± 208 (mean ± the SD) (Fig. 3A). Although the infection level appeared low, it increased with the infection time (P < 0.09), demonstrating a positive in vivo correlation between duration of infection and extent of DC infection (Fig. 3A). To determine whether lung DCs harbor infectious Chlamydia, 105 DCs purified from the lungs of 6-day-infected mice were transferred i.n. to naive mice. Two control groups received, respectively, DCs from noninfected animals or 2-000 C. muridarum IFU. Mice were monitored for body weight loss- and the bacterial load in the lungs was analyzed 6 days after infection. DCs purified from lungs of 6-day-infected mice contained infectious Chlamydia since i.n. transfer of the DCs caused mouse lung infection. Mice lost weight, and Chlamydia was isolated from the infected lungs (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast, mice receiving control DCs were not infected, whereas mice inoculated with C. muridarum IFU developed infection (Fig. 3B and C). These results show that after in vivo lung infection resident and/or migrating DCs take up Chlamydia. Within a population of these DCs, the bacteria remain both cultivable and infectious.

FIG. 3.

DCs from infected mice harbor infectious Chlamydia. Mice were inoculated i.n. with 2,000 Chlamydia IFU. After 2 or 6 days of infection, mice were sacrificed and total lung DCs were purified as indicated in Materials and Methods. (A) Homogenates of 106 purified DCs were titrated on HeLa cells to determine the IFU. (B) DCs (105) isolated from the lungs of 6-day-infected mice were transferred to naive mice. Animals were monitored for body weight loss. (C) Six days after transfer, the lungs were isolated, and the sonicated lung tissue was titrated on HeLa cells to determine the bacterial load. Experiments were performed on two separate occasions with similar results. The results represent the mean ± the SD from one representative experiment.

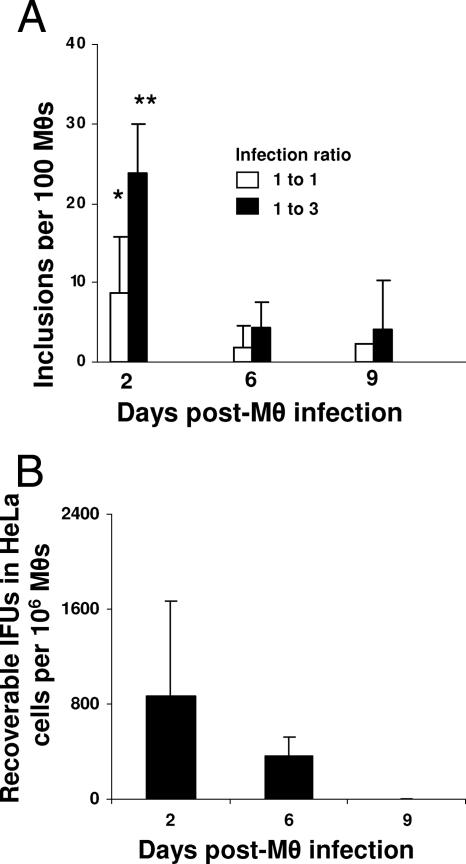

Survival of Chlamydia in Mφs.

Previous studies have demonstrated that C. trachomatis can survive in Mφs since the bacteria can be detected various days after Mφ infection (23, 48). However, once phagocytosed, the bacteria appear to be cleared rapidly and may not persist as readily as Chlamydia does in DCs. To test whether C. muridarum survive within Mφs, resident peritoneal Mφs were isolated and infected with Chlamydia EBs. Two, six, and nine days later, infected Mφs were analyzed both directly to detect chlamydial inclusions and indirectly on HeLa cells to determine cultivability. Direct staining showed that soon after infection, Mφ developed chlamydial inclusions, and the number of inclusions increased with the initial infecting dose to peak at 2 days postinfection (Fig. 4A). Inclusion formation, however, was significantly reduced (P < 0.09 and 0.001, respectively, following 1:1 and 1:3 MOI infection ratios), as comparing 2 and 9 days postinfection (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the bacteria isolated from Mφs showed remarkably low levels of cultivability. The recoverable IFU from 106 infected Mφs, after 2 or 6 days of incubation were, respectively, 866 ± 802 and 367 ± 152 (mean ± the SD). Furthermore, no IFU were recovered from 106 Mφs harvested 9 days after infection (Fig. 4B). These observations are in agreement with previous findings demonstrating that Chlamydia cannot be cultured from long-term-infected Mφs (23).

FIG. 4.

Survival of Chlamydia in Mφ. Resident peritoneal Mφs (106) were infected with C. muridarum (MOI of 1 or 3). (A) After 2, 6, or 9 days of incubation, cells were directly labeled with anti-Chlamydia MOMP antibody and developed by color with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Inclusion numbers were determined by averaging the number of inclusions in 10 microscopic fields using a ×20 objective lens, and inclusions were calculated in 100 Mφs. (B) In parallel, 106 infected Mφs (MOI of 1) were sonicated, and cell homogenates were titrated on HeLa cells to determine the number of inclusions. Note that no inclusions from 9-day-infected Mφ were grown on HeLa cells. All experiments were performed on three separate occasions with similar results. The results in panels A and B represent the mean ± the SD from one representative experiment. *, P < 0.09; **, P < 0.001 (as analyzed 2 versus 9 days after Mφ infection).

Chlamydia-infected BM-DCs present chlamydial antigen to T cells.

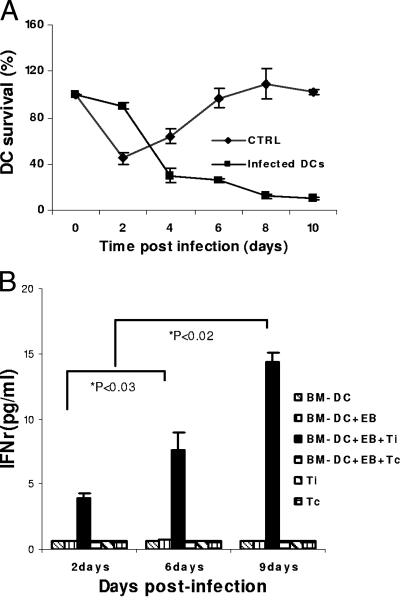

After activation, DCs undergo phenotypic and functional maturation. Mature DCs migrate to local lymph nodes, where they die after antigen presentation (1). Since the survival of DCs would be critical for the survival of Chlamydia, we then tested survival and immune physiology of DCs after long-term Chlamydia infection. BM-DCs were infected with C. muridarum and incubated for various time points. DCs were then analyzed for viability by trypan blue exclusion. As expected, infected DCs readily died, and this process markedly differed from uninfected (and presumably immature) DCs (Fig. 5A). A proportion of cells, however, survived, and by day 9 that fraction accounted for ∼20%. We then tested whether the surviving DCs were immunologically competent able to present Chlamydia antigens. DCs were infected with C. muridarum (MOI = 1) and incubated for 1, 6, or 9 days. Cells were then cocultured with Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleens of Chlamydia-immunized mice (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 5B, infected DCs were readily recognized by Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells as these cells specifically produced IFN-γ in the culture supernatant (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, IFN-γ production increased with the duration of DC infection (P < 0.02 and 0.03, comparing, respectively, days 2 and 6 with day 9) (Fig. 5B). These results showed that Chlamydia survive within a subset of DCs that appear to resist infection-induced cell death and whose antigen-presenting function does not seem to be altered by infection.

FIG. 5.

Chlamydia-infected BM-DCs present Chlamydia antigen to CD4+ T cells. (A) BM-DCs were infected with C. muridarum (MOI of 2). Infected and noninfected cells were analyzed for DC viability by trypan blue exclusion. Survival was calculated by dividing the number of cells that excluded trypan blue by the total DC numbers at time zero × 100. (B) For antigen presentation, BM-DCs were infected with C. muridarum (MOI of 2) and incubated for 2, 6, and 9 days. Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells purified from immune mice were cocultured with the infected DCs for 48 h. IFN-γ secreted in the culture supernatant was measured by ELISA. Experiments were performed on 5 (A) or 2 (B) separate occasions with similar results. The results in panels A and B represent the mean ± the SD from one representative experiment. Ti, immune CD4+ T cells; Tc, control (nonimmune) CD4+ T cells.

DISCUSSION

The striking and fascinating feature of Chlamydia immunobiology is the two-faceted phenomenon of immunity and immunopathology. Current in vitro evidence suggests that Chlamydia organisms can survive as metabolically active persistent forms displaying aberrant morphology, minimal cultivability, and low infectivity. Various lines of epidemiological and histopathological evidence also suggest that the bacteria are able to persist in chronic infections, including pelvic inflammatory disease, tubal scarring, and scarring trachoma, or in reactive arthritis (20) and may contribute to disease pathogenesis. The conditions that promote Chlamydia persistence in vivo have yet to be defined. DCs and Mφ are specialized antigen-presenting cells or scavenger cells, respectively, constantly searching for antigens and could potentially shelter Chlamydia in vivo. Although persistent Chlamydia organisms have been detected in Mφ (23), it is not clear whether these forms survive in DCs.

We have hypothesized that DCs are key to understanding the Janus-face phenomenon of Chlamydia immunobiology, and we have examined the survival of C. muridarum in DCs in the present study. Direct staining showed that Chlamydia develops inclusions in infected DCs. Inclusions were both typical, homogeneous, and compact in an immortalized DC cell line (Fig. 1Bb) and atypical, noncompact, aberrant, and polymorphic in BM-DCs (Fig. 1Ba). Aberrant inclusions that developed in BM-DCs appear to be similar to those that develop in Chlamydophila psittaci-infected HEp-2 cells in response to changes in culture conditions (17), and this suggests that inclusions developing in BM-DCs contain persistent bacteria. Interestingly, a modest increase in the percentage of DCs with inclusions was observed over 9 days of infection (Fig. 1A). Although we could not detect free Chlamydia in the culture supernatant of infected DCs, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that some EBs released from lysed DCs may have infected new DCs. However, it is more likely that inclusion-bearing DCs may have selectively survived over non-inclusion-bearing DCs (see Fig. 5A) and that these cells account for the increased percentage. Although Chlamydia from DCs was able to grow in HeLa cells, recovery was extremely low and was reduced with DC infection time (Fig. 1B). Given that persistent Chlamydia is normally aberrant and noncultivable (4), these combined observations suggest that at least a subpopulation of Chlamydia developing within infected DCs are of a persistent phenotype.

Our data also indicate that, in addition to persistent forms, infectious Chlamydia also develops within DCs after infection. This conclusion is supported by the observation that i.n. transfer of long-term-infected BM-DCs causes mouse lung infection. As few as 500 infected DCs from infected cell cultures that were harvested 9 days after infection were sufficient to cause disease (Fig. 2). Recently, we have observed that the transfer of 15-day-Chlamydia-infected BM-DCs to naive mice also caused lung infection (results not shown). DCs purified from the lungs of Chlamydia-infected mice also caused lung infection after i.n. transfer into naive mice, suggesting that infectious EBs develop and/or are harbored by DCs in vivo (Fig. 3B and C). Together, these results suggest that after DC infection, Chlamydia develops both persistent and infectious forms of bacteria. It also suggests that the generation of infectious organisms in DCs may be low level but continuous, which suggests that DCs may act as a reservoir for both persistent and infectious forms of Chlamydia.

Previous research has detected Chlamydia organisms in Mφs, as determined by the presence of Chlamydia RNA or Chlamydia antigens or by direct observation of Chlamydia by transmission electron microscopy (23). Our results show that C. muridarum can infect Mφs and develop chlamydial inclusions. Furthermore, similar to DCs, Chlamydia from infected Mφs can be grown on HeLa cells. However, the survival of the bacteria in Mφs appeared to be less than in DCs, as determined by direct staining of Chlamydia inclusions (Fig. 1A and 4A). Furthermore, in contrast to BM-DCs, no cultivable Chlamydia was isolated from Mφs infected for more than 48 h (Fig. 1B and 4B). It should be noted, however, that the methods by which we obtained BM-DCs and resident peritoneal Mφs differ greatly, and we may not have the ideal system to compare DCs and Mφs regarding Chlamydia persistence. Nonetheless, our results suggest that DCs better support Chlamydia survival than do Mφs. This is likely related to the distinct biological properties of Mφs and DCs. In contrast to Mφs, DCs have lower levels of lysosomal proteases, display lower levels for lysosomal degradation (12), and express high levels of various protease inhibitors, all of which contribute to slower processing of antigens by DCs. Slow processing of antigen appears to be a critical feature that allows DCs to ensure sustained antigen presentation (39).

We have previously shown that Chlamydia infection of DCs brings about DC activation, resulting in optimal presentation of chlamydial antigens to T cells (42). Our current results demonstrate that, after chlamydial infection, most DCs die, whereas a proportion of remaining cells are capable of surviving for more than 10 days. The surviving DCs appear to support the survival of Chlamydia while maintaining an ability to efficiently present antigen to Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5). Overall, Chlamydia appear to infect a subpopulation of DCs in which the bacteria seem to survive and/or persist.

Interestingly, Chlamydia is known to inhibit host cell apoptosis (14). Recent results suggest that persistent C. trachomatis also inhibits the apoptosis of HeLa cells (11). Together, these observations suggest that after infection, Chlamydia organisms enhance their survival by inducing survival of their host DCs. We have begun to test this hypothesis and have found that short-term- but not long-term-infected DCs resist staurosporine-induced apoptosis (J. Rey-Ladino, unpublished results). Further experiments are under way.

Our results show that Chlamydia does not interfere with the ability of DCs to present antigen. In fact, 6- and 9-day-infected DCs appeared to be better inducers of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells than 2-day-infected DCs (Fig. 5B). Since DCs may support the long-term survival of Chlamydia for the purposes of antigen presentation, it is possible that DCs carrying persistent Chlamydia may actually be involved in antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. Whether continuous presentation of antigen and production of IFN-γ is mediated by Chlamydia-infected DCs and whether infected DCs also present Chlamydia antigen in vivo is unknown. The answer to this question could have implications in immunopathology, since continuous presentation of chlamydial antigens to other T-cell subsets (Th2, Th17, or T regulatory cells) without actual eradication of the pathogen may be detrimental to the host (5, 28, 36).

Chlamydia survival in DCs may have important implications in various ways. First, Chlamydia may be reactivated and contribute to chronic infection. Indeed, human DCs harbor latent cytomegalovirus that can cause disease upon reactivation after proinflammatory cytokine stimulation (19). In addition, due to their migratory properties, DCs may carry and spread chlamydial infection in vivo. For example, it is recognized that DCs can carry human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from the periphery to uninfected T cells in the lymph nodes and facilitate the lysis of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in AIDS (7). Third, long-lived infected DCs may also maintain effector T cells necessary for Chlamydia immunity through the phenomenon of concomitant immunity (5). Finally, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) controls chlamydial growth but also inhibits T-cell-mediated immune responses (29). Since IDO is induced in DC subsets during inflammation (30), it may be that Chlamydia-infected DCs which produce IDO to control Chlamydia growth may promote the development of persistence forms of Chlamydia. Clearly, further research that assesses the role of DCs in Chlamydia pathology and immunity in vivo is likely to shed light on the murky topic of Chlamydia immunobiology.

In summary, we have shown that Chlamydia survives within DCs long after infection. Surviving Chlamydia organisms develop inclusions, are able to infect HeLa cells in vitro and mice in vivo, and do not appear to affect DC antigen-presenting function.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant to R.C.B. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Editor: J. L. Flynn

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 May 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beatty, W. L., T. A. Belanger, A. A. Desai, R. P. Morrison, and G. I. Byrne. 1994. Tryptophan depletion as a mechanism of gamma interferon-mediated chlamydial persistence. Infect. Immun. 62:3705-3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beatty, W. L., G. I. Byrne, and R. P. Morrison. 1994. Repeated and persistent infection with Chlamydia and the development of chronic inflammation and disease. Trends Microbiol. 2:94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty, W. L., R. P. Morrison, and G. I. Byrne. 1994. Persistent chlamydiae: from cell culture to a paradigm for chlamydial pathogenesis. Microbiol. Rev. 58:686-699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belkaid, Y., and B. T. Rouse. 2005. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat. Immunol. 6:353-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunham, R. C., and J. Rey-Ladino. 2005. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5:149-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron, P. U., P. S. Freudenthal, J. M. Barker, S. Gezelter, K. Inaba, and R. M. Steinman. 1992. Dendritic cells exposed to human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transmit a vigorous cytopathic infection to CD4+ T cells. Science 257:383-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, L. A., D. L. Patton, D. E. Moore, A. L. Cappuccio, B. A. Mueller, and S. P. Wang. 1993. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis deoxyribonucleic acid in women with tubal infertility. Fertil. Steril. 59:45-50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark, R. B., P. F. Schatzki, and H. P. Dalton. 1982. Ultrastructural analysis of the effects of erythromycin on the morphology and developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis HAR-13. Arch. Microbiol. 133:278-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coles, A. M., D. J. Reynolds, A. Harper, A. Devitt, and J. H. Pearce. 1993. Low-nutrient induction of abnormal chlamydial development: a novel component of chlamydial pathogenesis? FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 106:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean, D., and V. C. Powers. 2001. Persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infections resist apoptotic stimuli. Infect. Immun. 69:2442-2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delamarre, L., M. Pack, H. Chang, I. Mellman, and E. S. Trombetta. 2005. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science 307:1630-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhodapkar, M. V., R. M. Steinman, J. Krasovsky, C. Munz, and N. Bhardwaj. 2001. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T-cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 193:233-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan, T., H. Lu, H. Hu, L. Shi, G. A. McClarty, D. M. Nance, A. H. Greenberg, and G. Zhong. 1998. Inhibition of apoptosis in chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J. Exp. Med. 187:487-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gervassi, A. L., K. H. Grabstein, P. Probst, B. Hess, M. R. Alderson, and S. P. Fling. 2004. Human CD8+ T cells recognize the 60-kDa cysteine-rich outer membrane protein from Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Immunol. 173:6905-6913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gieffers, J., H. Fullgraf, J. Jahn, M. Klinger, K. Dalhoff, H. A. Katus, W. Solbach, and M. Maass. 2001. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in circulating human monocytes is refractory to antibiotic treatment. Circulation 103:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goellner, S., E. Schubert, E. Liebler-Tenorio, H. Hotzel, H. P. Saluz, and K. Sachse. 2006. Transcriptional response patterns of Chlamydophila psittaci in different in vitro models of persistent infection. Infect. Immun. 74:4801-4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hackstadt, T., E. R. Fischer, M. A. Scidmore, D. D. Rockey, and R. A. Heinzen. 1997. Origins and functions of the chlamydial inclusion. Trends Microbiol. 5:288-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn, G., R. Jores, and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Cytomegalovirus remains latent in a common precursor of dendritic and myeloid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:3937-3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan, R. J., S. A. Mathews, S. Mukhopadhyay, J. T. Summersgill, and P. Timms. 2004. Chlamydial persistence: beyond the biphasic paradigm. Infect. Immun. 72:1843-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holland, S. M., A. P. Hudson, L. Bobo, J. A. Whittum-Hudson, R. P. Viscidi, T. C. Quinn, and H. R. Taylor. 1992. Demonstration of chlamydial RNA and DNA during a culture-negative state. Infect. Immun. 60:2040-2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inaba, K., M. Inaba, N. Romani, H. Aya, M. Deguchi, S. Ikehara, S. Muramatsu, and R. M. Steinman. 1992. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 176:1693-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koehler, L., E. Nettelnbreker, A. P. Hudson, N. Ott, H. C. Gerard, P. J. Branigan, H. R. Schumacher, W. Drommer, and H. Zeidler. 1997. Ultrastructural and molecular analyses of the persistence of Chlamydia trachomatis (serovar K) in human monocytes. Microb. Pathog. 22:133-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, H., Z. Xing, and R. C. Brunham. 2002. GM-CSF transgene-based adjuvant allows the establishment of protective mucosal immunity following vaccination with inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Immunol. 169:6324-6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macpherson, A. J., and T. Uhr. 2004. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science 303:1662-1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manor, E., and I. Sarov. 1986. Fate of Chlamydia trachomatis in human monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. Infect. Immun. 54:90-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matyszak, M. K., J. L. Young, and J. S. Gaston. 2002. Uptake and processing of Chlamydia trachomatis by human dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 32:742-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenzie, B. S., R. A. Kastelein, and D. J. Cua. 2006. Understanding the IL-23-IL-17 immune pathway. Trends Immunol. 27:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mellor, A. 2005. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and regulation of T-cell immunity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338:20-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellor, A. L., B. Baban, P. Chandler, B. Marshall, K. Jhaver, A. Hansen, P. A. Koni, M. Iwashima, and D. H. Munn. 2003. Cutting edge: induced indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in dendritic cell subsets suppresses T-cell clonal expansion. J. Immunol. 171:1652-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mpiga, P., and M. Ravaoarinoro. 2006. Chlamydia trachomatis persistence: an update. Microbiol. Res. 161:9-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakajo, M. N., P. M. Roblin, M. R. Hammerschlag, P. Smith, and M. Nowakowski. 1990. Chlamydicidal activity of human alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun. 58:3640-3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nanagara, R., F. Li, A. Beutler, A. Hudson, and H. R. Schumacher, Jr. 1995. Alteration of Chlamydia trachomatis biologic behavior in synovial membranes: suppression of surface antigen production in reactive arthritis and Reiter's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 38:1410-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neild, A. L., and C. R. Roy. 2003. Legionella reveal dendritic cell functions that facilitate selection of antigens for MHC class II presentation. Immunity 18:813-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojcius, D. M., Y. Bravo de Alba, J. M. Kanellopoulos, R. A. Hawkins, K. A. Kelly, R. G. Rank, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 1998. Internalization of Chlamydia by dendritic cells and stimulation of Chlamydia-specific T cells. J. Immunol. 160:1297-1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pancholi, P., A. Mirza, N. Bhardwaj, and R. M. Steinman. 1993. Sequestration from immune CD4+ T cells of mycobacteria growing in human macrophages. Science 260:984-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papp, J. R., and P. E. Shewen. 1996. Localization of chronic Chlamydia psittaci infection in the reproductive tract of sheep. J. Infect. Dis. 174:1296-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton, D. L., M. Askienazy-Elbhar, J. Henry-Suchet, L. A. Campbell, A. Cappuccio, W. Tannous, S. P. Wang, and C. C. Kuo. 1994. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in fallopian tube tissue in women with postinfectious tubal infertility. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 171:95-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierre, P., and I. Mellman. 1998. Developmental regulation of invariant chain proteolysis controls MHC class II trafficking in mouse dendritic cells. Cell 93:1135-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollard, A. M., and M. F. Lipscomb. 1990. Characterization of murine lung dendritic cells: similarities to Langerhans cells and thymic dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 172:159-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raulston, J. E. 1997. Response of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar E to iron restriction in vitro and evidence for iron-regulated chlamydial proteins. Infect. Immun. 65:4539-4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rey-Ladino, J., K. M. Koochesfahani, M. L. Zaharik, C. Shen, and R. C. Brunham. 2005. A live and inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis strain induces the maturation of dendritic cells that are phenotypically and immunologically distinct. Infect. Immun. 73:1568-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sardinia, L. M., E. Segal, and D. Ganem. 1988. Developmental regulation of the cysteine-rich outer-membrane proteins of murine Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:997-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shen, Z., G. Reznikoff, G. Dranoff, and K. L. Rock. 1997. Cloned dendritic cells can present exogenous antigens on both MHC class I and class II molecules. J. Immunol. 158:2723-2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suram, S., G. D. Brown, M. Ghosh, S. Gordon, R. Loper, P. R. Taylor, S. Akira, S. Uematsu, D. L. Williams, and C. C. Leslie. 2006. Regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation and cyclooxygenase 2 expression in macrophages by the beta-glucan receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 281:5506-5514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf, K., E. Fischer, and T. Hackstadt. 2005. Degradation of Chlamydia pneumoniae by peripheral blood monocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 73:4560-4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. 2001. Global prevalence and incidence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections: overview and estimates. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/sti/who_hiv_aids_2001.02.

- 48.Yong, E. C., E. Y. Chi, and C. C. Kuo. 1987. Differential antimicrobial activity of human mononuclear phagocytes against the human biovars of Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Immunol. 139:1297-1302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]