Abstract

The genomic DNA sequences were determined for two filamentous integrative bacteriophages, φRSS1 and φRSM1, of the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. The 6,662-base sequence of φRSS1 contained 11 open reading frames (ORFs). In the databases, this sequence showed high homology (95% identity) to the circular double-stranded DNA plasmid pJTPS1 (6,633 bp) isolated from a spontaneously occurring avirulent mutant of R. solanacearum. Two major differences between the two sequences were observed within φRSS1 ORF7, corresponding to pIII, a minor coat protein required for host adsorption, and at the φRSS1 intergenic (IG) region. The 9,004-base sequence of φRSM1 showed 12 ORFs located on the same strand (plus strand) and 2 ORFs on the opposite strand. Compared with Ff-type phages, two insertions are obvious in the φRSM1 replication module. Genomic DNA fragments containing the φRSM integration junctions were cloned and sequenced from φRSM lysogenic strain R. solanacearum MAFF211270. The att core sequence was identified as 5′-TGGCGGAGAGGGT-3′, corresponding to the 3′ end of the serine tRNA (UCG) gene. Interestingly, ORF14, located next to the attP site on the φRSM1 genome, showed high amino acid sequence homology with bacterial DNA recombinases and resolvases, different from XerCD recombinases. attP of φRSS1 is within a sequence element of the IG region.

Ralstonia solanacearum is a soil-borne gram-negative bacterium known to be the causative agent of bacterial wilt in many important crops (14, 38). This bacterium has an unusually wide host range, with more than 200 species belonging to more than 50 botanical families (14). R. solanacearum strains represent a heterogeneous group subdivided into five races on the basis of their host range or six biovars on the basis of their physiological and biochemical characteristics (14). Recently, the complete genome sequence of R. solanacearum GMI1000 was reported (31). The 5.8-Mbp genome is organized into two replicons, a 3.7-Mbp chromosome and a 2.1-Mbp megaplasmid. The genome encodes a total of 5,129 predicted proteins, many of which are potentially associated with a role in pathogenicity. To accelerate comprehensive functional analyses of the pathogenicity of this pathogen, efficient molecular biological tools for R. solanacearum are required.

Very recently, Yamada et al. (39) detected and isolated various kinds of bacteriophage that specifically infect races of R. solanacearum. These phages may be useful as a tool for molecular biological studies of R. solanacearum pathogenicity. They could also be used for specific and efficient detection of harmful pathogens in cropping ecosystems, as well as growing crops. Two of them, φRSM1 and φRSS1, were characterized as Ff-like phages (inoviruses) on the basis of their particle morphology, genomic single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), and infection cycle. Despite their similar filamentous morphology, their genome sizes (9.0 kb for φRSM1 and 6.6 kb for φRSS1) and genome sequences were different. Strains of R. solanacearum that were sensitive to φRSM1 were resistant to φRSS1 and vice versa. Interestingly, all 15 strains of R. solanacearum tested contained φRSS1-related sequences in their genomes and the φRSS1 hybridization patterns coincided well with the taxonomical grouping of these strains. φRSS1 infection was shown to enhance the virulence of strain C319 (race 1). Similarly, 6 of the 15 strains tested showed strong hybridization signals for φRSM1-related sequences in their genomes. There were two types of φRSM1-related sequences, A and B, distinguished by restriction fragmentation pattern, and only strains of type B could serve as hosts for φRSS1 infection. Of these, at least one strain, MAFF211270 (type A), contained a lysogenic φRSM1-like phage and occasionally produced phage particles (39). These results clearly demonstrate the temperate phage nature of φRSM1. Other filamentous Ff-like phages known to have a lysogenic cycle include Xanthomonas campestris phages Cf1c (22), Cf1t (20, 21), Cf16v1 (7), and φLf (24); Xylella fastidiosa phage Xfφf1 (35); Yersinia pestis phage CUSφ-2 (11); and Vibrio cholerae phages VGJφ (5) and CTXφ (18). These host bacteria are pathogenic for plants and animals, and the phages are frequently involved in pathogenesis.

In general, the genomes of Ff phage are organized in a module structure in which functionally related genes are grouped (15, 30). Three functional modules are always present. The replication module contains the genes encoding rolling-circle DNA replication and ssDNA binding proteins, gII, gV, and gX (27). The structural module contains genes for the major (gVIII) and minor (gIII, gVI, gVII, and gIX) coat proteins, and gene gIII encodes the host recognition or adsorption protein pIII (2). The assembly-and-secretion module contains the genes (gI and gIV) for morphogenesis and extrusion of the phage particles (26). Gene gIV encodes protein pIV, an aqueous channel (secretin) in the outer membrane through which phage particles exit from the host cells. Some phages encode their own secretins, but others use host products (8). In addition, some phages encode transcriptional repressors, like RstR of CTXφ and vpf122 of Vf22, which regulate the expression of other phage genes (6, 19). In the lysogenic filamentous phages such as CTXφ, two chromosome-encoded site-specific recombinases (XerC and XerD) are known; they catalyze recombination between the phage attachment site (attP) and the chromosome attachment site (attB) inside the site-specific recombination site dif of the host chromosome (18). Other lysogenic filamentous phages, including those described above, seem to use XerCD recombinases in a similar way.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and phages.

Strains of R. solanacearum were obtained from the following culture collections. Strains M4S, MAFF106611, and MAFF211270 were from the Leaf Tobacco Research Center, Japan Tobacco Inc., and the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Japan, respectively. Strain C319 (10) was kindly donated by N. Furuya, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan. The bacterial cells were cultured in CPG medium (17) at 28°C with shaking at 200 to 300 rpm. Phages were propagated and purified from single-plaque isolates. Routinely, phages φRSS1 and φRSM1 were propagated with strains C319 and M4S as the host, respectively. An overnight culture of bacterial cells grown in CPG medium was diluted 100-fold with 100 ml fresh CPG medium in a 500-ml flask. To collect sufficient amounts of phage particles, a total of 2 liters of bacterial culture was grown. When the cultures reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.1, the phage was added at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01 to 0.05. After further growth for 16 to 18 h, the cells were removed by centrifugation with an R12A2 rotor in a Hitachi himac CR21E centrifuge at 8,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter, followed by precipitation of the phage particles in the presence of 0.5 M NaCl and 5% polyethylene glycol 6000. Phage preparations were stored at 4°C until use. Escherichia coli XL10 Gold and pBluescript II SK(+) were obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA).

DNA manipulations and sequencing.

Standard molecular biological techniques for DNA isolation, digestion with restriction enzymes and other nucleases, and construction of recombinant DNAs were used according to Sambrook and Russell (32). Phage DNA was isolated from the purified phage particles by phenol extraction. In some cases, extrachromosomal DNA was isolated from phage-infected R. solanacearum cells by the minipreparation method (3). Replicative-form (RF) DNA for sequencing was isolated from host bacterial cells infected with φRSS1 or φRSM1 and partially digested with Sau3AI. DNA fragments of 1.0 to 4.0 kbp were recovered from the agarose gels after electrophoretic separation and ligated to the BamHI site of pBluescript II SK(+). After transformation into E. coli XL10 Gold cells, random clones were isolated for nucleotide sequencing. The DNA sequences of both strands were determined throughout, with a total coverage of 5.0×. Computer-aided assembly of the nucleotide sequence data was performed with a DNASIS (version 3.6) program (Hitachi Software Engineering Co., Ltd.). Potential ORFs larger than 80 bp were identified with the online program Orfinder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html) and the DNASIS program. Sequence alignment was performed with the ClustalW program. To search for signal peptide cleavage sites and transmembrane domains, the online programs SignalP (http://genome.cbs.dtu.dk) and SOSUI (http://sosui.proteome.bio.tuat.ac.jp) were used. For prediction of RNA and DNA secondary structures, the Pairfold software was used (http://www.rnasoft.ca/). To assign possible functions to the ORFs, searches of the databases were done with the FASTA, FASTX, BLASTN, and BLASTX programs (1).

An autonomously replicating plasmid was constructed from φRSS1 DNA as follows. Approximately 2,160 bases of φRSS1 DNA lacking the modules for structural proteins and morphogenesis (ORF4 to ORF11) was amplified by PCR with a forward primer, 5′-CGG AAT TCT ATC CGG AGT AAC GA AAA G, corresponding to the 3′ end of orf11 and a reverse primer, 5′-ATG GAA TTC TCC TTG AGA TGG AGG TTG AG, corresponding to the 5′ end of orf4. Twenty-five rounds of PCR were performed with RF DNA (1 ng) of φRSS1 as a template under the standard conditions in a MY Cycler (Bio-Rad). After digestion with EcoRI at the primer sites, the amplified fragment was connected to a Kmr cassette cut out with EcoRI from plasmid pUC4-KIXX (Amersham Biosciences). It was then introduced into cells of R. solanacearum MAFF106611 by electroporation by using a Gene Pulser Xcell (Bio-Rad) with a 2-mm cell at 2.5 kV according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transformants were selected on CPG plates containing 15 μg/ml kanamycin (Meiji Seika, Tokyo, Japan).

In a similar way, an autonomously replicating plasmid (pRSM11) was constructed from φRSM1 DNA as follows. An approximately 2.4-kb portion of φRSM1 DNA containing ORF1 to ORF8 was amplified by PCR with a 21-base forward primer (P1), 5′-CTG CTG CAG CAG GAA TTC AAG, corresponding to the 3′ end of orf14 (with an EcoRI site added) and a 21-base reverse primer (P2), 5′-GTA CCA CCG GTC GTG GTC TGA, corresponding to the 3′ end of orf8 (Fig. 1C). Another fragment of φRSM1 DNA approximately 3.2 kb in size, containing orf11 and orf12, was amplified by PCR. The primers were a 20-base forward primer (P3), 5′-CAG TCC GCG TTC AAC TCG TT, corresponding to the 3′ end of orf10 and a 21-base reverse primer (P4), 5′-CGC GAT CCG AAT TCA AAT GAG, corresponding to the 5′ end of orf13 (with an EcoRI site added). Both 2.4-kb and 3.2-kb PCR products were blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase and phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase. After digestion with EcoRI at the primer sites, the DNA fragments were mixed with a Kmr cassette (with EcoRI sites at both ends) and treated with T4 DNA ligase. The reaction mixture was introduced into the cells of R. solanacearum M4S by electroporation as described above.

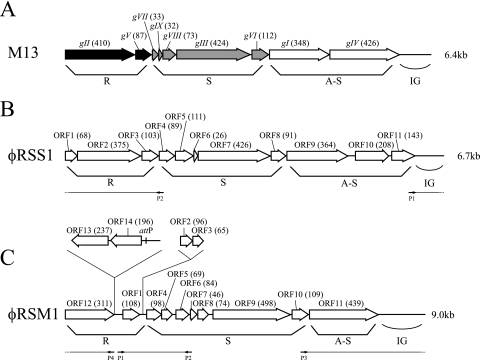

FIG. 1.

Genomic organization of bacteriophages φRSS1 and φRSM1. Linear ORF maps of E. coli phages M13 (A), φRSS1 (B), and φRSM1 (C) are compared. ORFs or genes are represented by arrows oriented in the direction of transcription. The functional modules for replication (R), structure (S), and assembly-secretion (A-S) are indicated according to the M13 model (26). ORF sizes (in amino acids) are in parentheses. The region containing the attP sequence is also indicated. Most of the gene function assignments for φRSS1 and φRSM1 are still putative. Arrows P1 and P2 in panel B and P1 to P4 in panel C indicate primers used in PCR.

To identify the attP and attB sequences of φRSM1, genomic DNA of R. solanacearum strain MAFF211270 which contains a φRSM1-like prophage (39) was digested with HincII and hybridized with a φRSM1 DNA probe as described below. Two hybridizing bands of 4.3 kb and 3.5 kb, thought to contain each of the integration junctions, were cut from the gel, ligated to the EcoRV site of pBluescript II SK+, and cloned into E. coli XL10 Gold. Nucleotide sequences determined for the clones were compared with the φRSM1 genomic sequence.

Southern blot hybridization.

Genomic DNA of R. solanacearum cells was prepared by a standard method according to Ausubel et al. (3). After digestion with various restriction enzymes, DNA fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and blotted onto a nylon membrane (Biodyne; Pall Gelman Laboratory, Closter, NJ). They were then hybridized with a probe (φRSS1 or φRSM1 genomic DNA), labeled with fluorescein (Gene Images Random Prime labeling kit; Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden), and detected with a Gene Images CDP-Star detection module (Amersham Biosciences). Hybridization was performed in buffer containing 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 5% dextran sulfate for 16 h at 65°C. The filter was washed at 60°C in 1× SSC-0.1% SDS for 15 min and then in 0.5% SSC-0.1% SDS for 15 min with agitation according to the manufacturer's protocol. The hybridization signals were detected by exposing the filter to X-ray film (RX-U; Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and peptide sequencing.

Purified phage particles were subjected to SDS-PAGE according to Laemmli (23). For the separation of small proteins, Tricine-SDS-PAGE was performed according to the method of Schagger and von Jagow (33). The separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride nylon membranes (Immobilon; Nihon Millipore K.K., Tokyo, Japan) with a semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Each protein band was subjected to N-terminal peptide sequence analysis on a protein sequencer (model 492; Applied Biosystems) as described by Songsri et al. (36). The UniProt and GenBank databases were searched for sequences homologous to the amino acid sequences obtained.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence data for φRSS1 and φRSM1 have been deposited in the DDBJ database under accession no. AB259124 and AB259123, respectively.

RESULTS

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the φRSS1 genomic DNA.

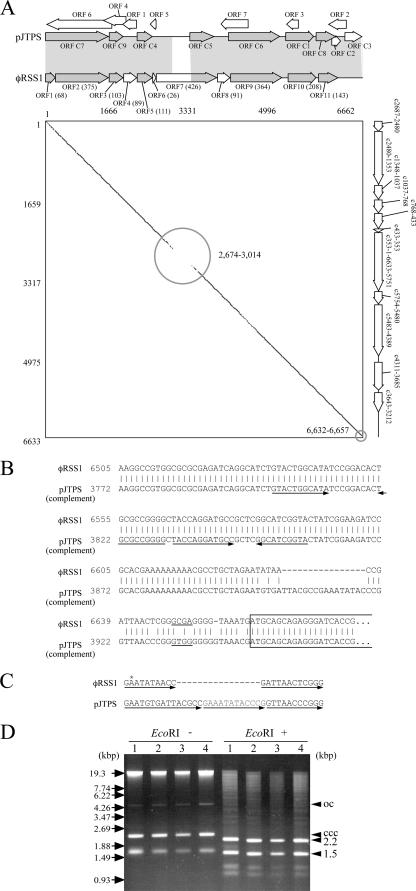

The genome of φRSS1 was 6,662 nucleotides (nt) long (DDBJ accession no. AB259124) with a GC content of 62.6%, which is comparable to that of R. solanacearum GMI1000 (66.97%) (31). There were 11 ORFs located on the same strand (Fig. 1B). Frequently, the termination codon of the preceding gene overlapped the initiation codon of the following gene. The coding sequence occupied by these ORFs accounted for 91.6% of the total φRSS1 sequence. The 11 ORFs showed similarity to known gene sequences, as shown in Table 1. The circular double-stranded DNA plasmid pJTPS1 found in one strain of R. solanacearum (DDBJ accession no. AB015669) showed significant nucleotide sequence similarity to the φRSS1 DNA. The size of pJTPS1 is 6,633 bp, 29 bp smaller than that of φRSS1. The nucleotide sequence identity of the two DNAs was 95%. Figure 2A shows the alignment of ORFs and a matrix comparison of the φRSS1 and pJTPS1 sequences, indicating two major differences located around φRSS1 nucleotide positions 2674 to 3014 and 6632 to 6657. The former region was included in the large ORF7 coding region (pIII), and the latter corresponded to the intergenic (IG) region.

TABLE 1.

Predicted ORFs found in the φRSS1 genome

| Coding sequence | Position (5′ to 3′) | GC content (%) | Length of protein (aa) | Molecular mass (kDa) | Amino acid sequence identity/similarity to best homologs (no. of amino acids identical; % identity) | FASTA score (E value) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | 1-207 | 65.7 | 68 | 7.8 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C7 (68; 97) | 432 (4.8e-26) | trO82959 |

| ORF2 | 207-1334 | 63.8 | 375 | 41.7 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C7 (375; 100) | 2,521 (4.1e-158) | trO82959 |

| Xanthomonas oryzae phage replication protein RstA (pII) (321; 30.7) | 389 (2e-17) | prf3108482DPY | |||||

| ORF3 | 1339-1650 | 61.1 | 103 | 11.2 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C9 (103; 100) | 655 (1.4e-42) | trO82957 |

| Nitrosomonas europaea hypothetical protein (101; 63.7) | 170 (3.1e-05) | trQ82W10 | |||||

| ORF4 | 1650-1919 | 61.5 | 89 | 9.1 | Nitrosomonas europaea hypothetical protein (64; 41.9) | 139 (0.015) | trQ82W09 |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria phage-related protein (78; 38.8) | 86 (1.6) | trQ3BSS6 | |||||

| ORF5 | 1919-2254 | 65.5 | 111 | 11.5 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C4 (111; 100) | 740 (3.6e-44) | trO82955 |

| ORF6 | 2254-2334 | 58.0 | 26 | 3.0 | No significant homology | ||

| ORF7 | 2334-3614 | 61.9 | 426 | 43.2 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C5 (pIII) (180; 99.4) | 1,237 (3.1e-64) | trO82968 |

| Acidovorax sp. hypothetical protein (362; 56.1) | 284 (3.6e-08) | trQ0Z3U7 | |||||

| ORF8 | 3611-3886 | 65.7 | 91 | 9.0 | Nitrosomonas europaea putative phage gene (90; 40.5) | 200 (3.1e-05) | trQ82W07 |

| Bacteriophage Pf3 Orf93 (pVI) (75; 70.7) | 146 (0.12) | prf1203325F | |||||

| ORF9 | 3883-4977 | 65.0 | 364 | 39.3 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C6 (364; 99.2) | 2,430 (3.9e-140) | trO82966 |

| Xanthomonas phage Cf1c gene (pI) (380; 36.2) | 430 (4e-18) | trQ38198 | |||||

| ORF10 | 5055-5681 | 59.6 | 208 | 22.4 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C1 (208; 100) | 1,271 (3.2e-71) | trO82964 |

| Ralstonia phage p12J ORF9 (107; 75.5) | 428 (6.3e-19) | trQ6UAZ0 | |||||

| ORF11 | 5723-6154 | 63.3 | 143 | 16.5 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C8 (143; 100) | 973 (4.5e-59) | trO82963 |

| Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica plasmid-related protein (138; 64.5) | 602 (1.4e-33) | prf3020410AAK |

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the φRSS1 genomic DNA and plasmid pJTPS1 DNA. (A) ORF alignment and matrix comparison between φRSS1 genomic DNA (6,662 bases) and plasmid pJTPS1 DNA (6,633 bp; from position 3947 in the complementary sequence with DDBJ accession no. AB015669) sequences. Gray shading indicates the significant amino acid or nucleotide sequence similarity between the two DNAs. In a matrix comparison between φRSS1 (across) and modified pJTPS1 (down), 15 matches between 15 nucleotide sequences are marked by dots (DNASIS). The nucleotide sequence identity between the two DNAs was 95%. Two regions containing extended changes are shown by circles (φRSS1 positions 2674 to 3014 and 6632 to 6657). ORFs are indicated along the φRSS1 sequence. (B) Nucleotide sequence alignment of the φRSS1 (positions 6505 to 20) and pJTPS1 (positions 3772 to 3966 in the complementary sequence) DNA IG regions. The coding region of ORF1 is boxed. Underlined are the Shine-Dalgarno sequences. Arrows indicate the regions having potential to form hairpin structures. (C) A model to show repetition of sequence elements (arrow) in the IG region changed between the φRSS1 and pJTPS1 DNAs. The asterisk on the φRSS1 sequence shows the position of integration on the C319 genomic DNA. (D) Formation of an autonomously replicating plasmid from φRSS1 DNA. All Kmr transformants (lanes 1 to 4) harbored plasmid pRSS11, from which a 1.5-kbp Kmr cassette was cut out by EcoRI digestion. ssDNA molecules that were sensitive to S1 nuclease digestion were also observed. ccc, covalently closed circular; oc, open circular.

Although 15 ORFs were identified on the pJTPS1 DNA, 6 of which are on the same strand and the remaining 9 of which are on the opposite strand (DDBJ accession no. AB015669), the complementary ORFs (C1 to C9) were hit in this work (Table 1). By base changes or frame shifting on the φRSS1 DNA, pJTPS1 ORF2 could not be verified, ORF C7 was split into two ORFs, and three new ORFs were identified. Of these three φRSS1 ORFs (ORF4, ORF6, and ORF8), ORF4 and ORF6 could also be identified on pJTPS1 DNA (100% amino acid identity), whereas ORF8 was missing by a frameshift. Most of the pJTPS1 ORFs on the opposite strand are also the same in the φRSS1 DNA, but we consider them to be artifactual for the reasons described below.

According to the homology shown in Table 1, a putative module organization of φRSS1 can be depicted as shown in Fig. 1B. The φRSS1 genes fit well with the general arrangement of Ff-like phages. A survey of the databases for amino acid sequences of some φRSS1 ORFs revealed significant homology to Ff-like phage proteins such as ORF2 (pII homologue), ORF4 (pVIII homologue), ORF7 (pIII homologue), ORF8 (pVI homologue), and ORF9 (pI homologue). ORF11 might be involved in the virulence-enhancing effects (39) because pJTPS1 with a corresponding ORF disrupted by an insertion transforms bacterial cells to nonpathogenicity (28). Further information is required to exactly assign a biological function to each ORF of φRSS1.

The six ORFs detected on the opposite strand of plasmid pJTPS1 (Fig. 2A) overlap the possible functional phage modules of φRSS1 and do not accord with the codon usage that is well conserved among the φRSS1 plus strand genes. For example, codons AAG (Lys), GAG (Glu), and ACG (Thr) are predominant in the phage genes (accounting for 82.2%, 70.8%, and 60.8% of the corresponding amino acids, respectively), whereas they are relatively rare in the opposite ORFs (42.9%, 30.1%, and 37.9%, respectively). These ORFs did not show any significant sequence homology with known proteins in the databases. These results suggest that pJTPS1 may have been derived from a φRSS1-like phage, followed by changes in the phage DNA.

Relationship between φRSS1 and pJTPS1.

Compared with pJTPS1, two major different regions in the φRSS1 DNA were recognized (Fig. 2B). One region (φRSS1 positions 2674 to 3014) corresponded to ORF7, putatively encoding pIII, which is a minor coat protein at one end of the phage particle required to recognize and adsorb to host cells (26, 27). The other extended change was found at positions 6632 to 6657, corresponding to the IG region highly conserved in other Ff-like phages (27). This region may be involved in the rolling-circle DNA replication mechanism, producing phage genomic ssDNA molecules. Nucleotide changes in the corresponding region between the φRSS1 and pJTPS1 DNAs are not simple; within a 30-base region of the φRSS1 DNA, 17 bases are added and 4 bases are substituted in pJTPS1 (Fig. 2A). This addition can be explained by repetition of a φRSS1 sequence element in pJTPS1, as shown in Fig. 2C. Downstream of this changed region, there is a possible Shine-Dalgarno sequence (GCGA/GTGG), followed by ORF1, suggesting that this region may function as a promoter of ORF1 and affect its expression in pJTPS1.

Formation of an autonomously replicating plasmid from the φRSS1 DNA.

To verify the replication origin possibly present around this IG region, an autonomously replicating plasmid was derived from the φRSS1 DNA. A one-third portion (approximately 2,160 bases) of the φRSS1 DNA that lacks the modules for structural proteins and morphogenesis (ORF4 to ORF11) was amplified by PCR with a 27-base forward primer corresponding to the 3′ end of orf11 and a 29-base reverse primer corresponding to the 5′ end of orf4. After digestion with EcoRI at the primer sites, the amplified fragment was connected to a Kmr cassette of approximately 1.5 kbp cut out from pUC4-KIXX with EcoRI. The resulting plasmid of approximately 3.7 kbp (pRSS11) was introduced into R. solanacearum cells by electroporation. It was stably maintained (100% retained after 100 generations without kanamycin) in a single copy in these cells, indicating that the region between the 3′ end of orf11 and the 5′ end of orf2 may contain the φRSS1 DNA replication origin. Interestingly, nuclease S1-sensitive ssDNA molecules of the plasmid were detected in some of the transformed cells (Fig. 2D).

Integration of φRSS in R. solanacearum strain C319.

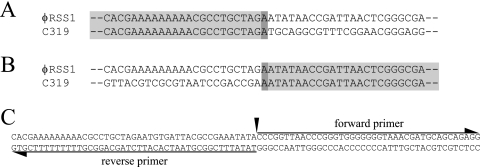

In our previous Southern blot hybridization experiments, we detected φRSS1-related sequences in the genomic DNAs of all 15 strains of R. solanacearum (39). To characterize such sequences, 2.7-kbp and 1.2-kbp HincII bands of strain C319 which showed strong hybridization signals were cloned and sequenced. Their sequences exactly coincided with that of φRSS1 (data not shown), indicating an integration of φRSS1 in strain C319. The φRSS1 integration site was determined by inverse PCR as follows. After cyclization with DNA ligase of EcoRI fragments of C319 genomic DNA (there is no EcoRI site in the φRSS1 DNA), 27-mer oligonucleotides of the φRSS1 sequence were arbitrarily set for forward and reverse primers in PCR. When the forward primer was S-6450F (5′-GCC GAT GCT ACG CTG CTC AGA ACA ACC-3′) and the reverse primer was S-1399R (5′-CAT CCA TGT TGC CAA CCC ACG TCT TGG-3′), a 3.7-kbp PCR product was obtained. The nucleotide sequence determined for this fragment revealed that this 3.7-kbp sequence contained both junctions of φRSS1 integration, as shown in Fig. 3A and B. There is only one overlapping base (A) of the φRSS1 sequence between the two junctions. The φRSS1 sequence at the integration site corresponds to position 6629 in the IG region, 34 nt upstream from ORF1, which is within the region different from pJTPS1 (indicated by an asterisk in Fig. 2C).

FIG. 3.

Junctions of integrated φRSS1 DNA in the lysogenic strain R. solanacearum C319 genome. (A) Partial sequence of the 3.7-kbp PCR product containing the right junction of φRSS1 integration on the strain C319 genomic DNA. The sequence is compared with the φRSS1 sequence. (B) Partial sequence of the 3.7-kbp PCR product containing the left junction of φRSS1 integration on the strain C319 genomic DNA. The sequence is compared with the φRSS1 sequence. (C) PCR primers for the production of pJTPS1 DNA from M4S chromosomal DNA and ligation for self-cyclization. According to the sequence of the φRSS1 host integration site, a 41-base forward primer and a 45-base reverse primer were set. After PCR, a band with the expected size was isolated, phosphorylated with polynucleotide kinase, ligated with DNA ligase, and introduced into the cells of strain M4S by electroporation.

pJTPS1 corresponds to the RF of a φRSS-type phage.

On the basis of the nucleotide sequence similarity between φRSS1 and pJTPS1 as described above, we tested the phage nature of pJTPS1 in strain M4S, where pJTPS1 was initially identified as a circular double-stranded DNA plasmid (28). We could not detect the plasmid molecules in cells of strain M4S, but Southern hybridization of the genomic DNA of strain M4S with φRSS1 DNA as a probe showed positive bands; at least 3.4-kbp and 1.2-kbp HincII bands showed specific hybridization (39). The nucleotide sequence determined for these bands exactly coincided with that of pJTPS1 (data not shown), indicating that pJTPS1 is integrated in the M4S genomic DNA. The integration may have occurred in a similar way as in the case of φRSS1 strain C319. If so, the pJTPS1 region corresponding to the φRSS1 integration sequence can be used as PCR primers to amplify pJTPS1 DNA from strain M4S. As indicated in Fig. 3C, a pair of primers (a 41-base forward primer and a 45-base reverse primer) was set according to the pJTPS1 sequence (Fig. 2B and C). After PCR with primeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), an approximately 6.6-kb band was produced, as expected. The band was isolated, phosphorylated with polynucleotide kinase, ligated with DNA ligase, and introduced into cells of strain M4S by electroporation. After standing for 2 h at 28°C, the cells were overlaid on CPG plates with soft agar medium. Plaques were visible after 16 to 24 h of incubation; the plaque size was relatively small, and the frequency was relatively low, indicating that pJTPS1 is the RF of an RSS1-related phage and is integrated in strain M4S. There is no immunity in the phage infection. Interestingly, the pJTPS1 phage infected the φRSM1-sensitive strains, including M4S, and did not infect φRSS1-sensitive strains, including strain C319.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the φRSM1 genomic DNA.

The genome of φRSM1 was 9,004 nt long (DDBJ accession no. AB259123) with a GC content of 59.9%, which is lower than that of R. solanacearum GMI1000 (66.97%) (31). There were 12 putative ORFs located on the same strand and two on the opposite strand (Fig. 1C). In contrast to φRSS1, overlapping between the termination codon of the preceding gene and the initiation codon of the following gene was rare. The coding sequences occupied by these ORFs accounted for 83.0% of the total φRSM1 sequence. Assignment of gene functions to these ORFs by FASTA, FASTX, BLASTN, and BLASTX searches revealed that 10 ORFs showed homology to known gene sequences (Table 2). Since φRSM1 ORF1 corresponded to p12J ORF1, which was described as a possible ssDNA-binding protein, we designated this ORF the first ORF in the possible gene organization according to the Ff phage model (27). On the basis of homology, three ORFs were included in a putative replication module and seven ORFs (ORF4 to ORF10) were included in the structure module, as shown in Fig. 1C. There was homology between φRSM1 ORF12 and Rep proteins of various bacteria and plasmids. It was found that the plus-strand ssDNA was generated from plasmid pHT926 by a rolling-circle mechanism like phages (9). Because no ORF with obvious homology with pII was found on the φRSM1 genome, a protein encoded by ORF12 may have an equivalent function. There is a wide gap (IG region) between ORF11 and ORF12. Two remaining ORFs (ORF13 and ORF14) are on the opposite strand and show amino acid sequence similarity to a proline-rich transmembrane protein and a DNA recombinase, respectively (Table 2). Compared with the conserved gene arrangement of Ff-like phages, the φRSM1 genes can be drawn as shown in Fig. 1C. Here, ORF13 and ORF14 are inserted between ORF11, corresponding to pII as a replication protein, and ORF1, corresponding to an ssDNA-binding protein like pV in the putative replication module. There are two additional ORFs (ORF2 and ORF3) between the replication and structural modules. No functions are known for these ORF-encoded proteins.

TABLE 2.

Predicted ORFs found in the φRSM1 genome

| Coding sequence | Position (5′ to 3′) | GC content (%) | Length of protein (aa) | Molecular mass (kDa) | Amino acid sequence identity/similarity to best homologs (% amino acid identity) | FASTA score (E value) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF1 | 1-327 | 60.5 | 108 | 11.5 | Burkholderia pseudomallei hypothetical protein (104; 41.3) | 248 (3.4e-10) | prf3023444FVA |

| Ralstonia pickettii phage p12J ORF1 possible ssDNA-binding protein (pII) (90; 34.4) | 141 (0.021) | trQ6UAZ8 | |||||

| ORF2 | 393-683 | 61.0 | 96 | 10.8 | No significant homology | ||

| ORF3 | 708-905 | 61.6 | 65 | 7.4 | Ralstonia solanacearum plasmid pJTPS1 ORF C7 (51; 39.2) | 122 (0.091) | trO82959 |

| ORF4 | 905-1201 | 62.0 | 98 | 10.7 | Ralstonia pickettii phage p12J ORF2 possible minor coat protein (55; 63.6) | 241 (1.1e-09) | trQ6UAZ8 |

| ORF5 | 1201-1410 | 59.5 | 69 | 7.6 | No significant homology | ||

| ORF6 | 1462-1716 | 57.6 | 84 | 9.9 | No significant homology | ||

| ORF7 | 1730-1870 | 55.3 | 46 | 5.0 | No significant homology | ||

| ORF8 | 1873-2097 | 66.7 | 74 | 7.5 | Xanthomonas campestris phage phiLf major coat protein (pVIII) (41; 41.5) | 102 (0.38) | spP68673 |

| ORF9 | 2173-3669 | 60.8 | 498 | 49.9 | Burkholderia pseudomallei putative membrane protein (pIII) (399; 25.3) | 238 (0.0017) | prf3023444CKJ |

| ORF10 | 3682-4011 | 56.4 | 109 | 11.7 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia phage φSMA9pVI (101; 31.7) | 198 (4.5e-06) | trQ4LAU3 |

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris phage minor coat protein pVI (98; 33.7) | 190 (1.5e-05) | trQ8P904 | |||||

| Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria phage φLfpVI (98; 32.7) | 189 (1.8e-05) | trQ3BSR8 | |||||

| ORF11 | 4016-5335 | 61.7 | 439 | 48.2 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia phage φSMA9 Zot (430; 30.5) | 467 (1.9e-21) | trQ4LAU4 |

| ORF12 | 6222-7157 | 58.2 | 311 | 35.0 | Ralstonia metallidurans phage-related protein (271; 41.7) | 677 (1.7e-37) | trQ3RU47 |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei phage-related protein (229; 41.9) | 528 (1.9e-27) | trQ63PM8 | |||||

| Ralstonia pickettii phage p12J ORF10 (277; 33.6) | 341 (7.5e-15) | trQ6UAY9 | |||||

| ORF13 | 7878-7165 | 56.9 | 237 | 27.0 | Ralstonia solanacearum probable proline-rich transmembrane protein (128; 28.1) | 153 (0.64) | trQ8Y2E4 |

| ORF14 | 8495-7905 | 58.7 | 196 | 22.0 | Pelodictyon phaeoclathratiforme resolvase, N terminal (182; 52.7) | 582 (2.2e-31) | trQ3VJH7 |

| Marinobacter aquaeolei invertase/recombinase protein (197; 45.2) | 556 (1.3e-29) | trQ36TJ9 |

Formation of an autonomously replicating plasmid from φRSM1 DNA.

To verify the possible replication genes and the function of the IG region, an autonomously replicating plasmid was derived from φRSM1 DNA. An approximately 2.4-kb portion containing ORF1 to ORF8 and another fragment of approximately 3.2 kb containing ORF11 and ORF12 of φRSM1 DNA were amplified by PCR with appropriate primers as indicated in Fig. 1C. Both 2.4-kb and 3.2-kb PCR products were connected to each other with blunt ends and with a Kmr cassette (with EcoRI sites at both ends) with EcoRI sites. The ligated mixture was introduced into R. solanacearum M4S cells by electroporation. The resulting plasmid of approximately 7.1 kbp (pRSM11), which lacks ORF8 to ORF10 and ORF13 to ORF14, was maintained in a single copy in R. solanacearum M4S transformants, indicating that ORF13 and ORF14 are not essential for replication. If orf12 was removed from pRSM11, the plasmid could not be maintained in the cells (data not shown), which is consistent with the presumed replicational function of ORF12 as described above.

Integration of φRSM in R. solanacearum strain MAFF211270.

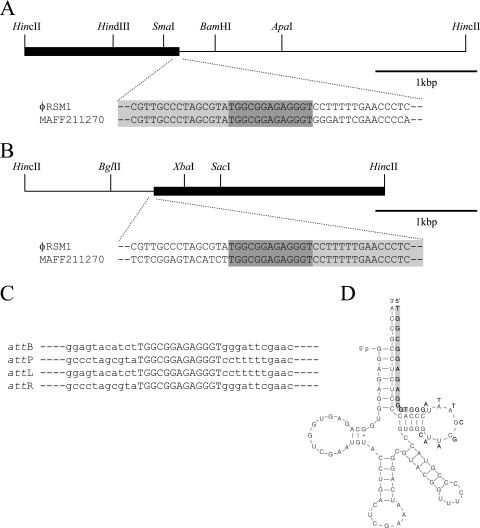

In our previous experiments, 6 of the 15 strains of R. solanacearum tested showed φRSM1-related sequences on the genomic DNA in Southern blot analysis (39), suggesting the temperate phage nature of φRSM1. In fact, φRSM1 phage plaques appeared spontaneously from strain MAFF211270, one of the hybridizing strains. Southern blot analysis of HincII fragments of strain MAFF211270 genomic DNA revealed five φRSM1-hybridizing bands, two of which (a 4.3-kbp band and a 3.5-kbp band) were expected to contain junctions of integrated φRSM1-like DNA, judging by the relative intensities of the hybridization signals and their large sizes. These bands were cut from the gel, ligated to pBluescript II SK+, and cloned into E. coli, and their entire nucleotide sequences were determined. By comparing their nucleotide sequences with that of φRSM1 DNA, it was found that one junction was located on the 4.3-kbp fragment (approximately 1.5 kbp from one end, Fig. 4A) and the other was located at a position approximately 1.4 kbp from one end of the 3.5-kbp fragment (Fig. 4B). The two junction sequences of the φRSM1-like phage overlapped by the 13-bp sequence 5′-TGGCGGAGAGGGT-3′ (Fig. 4C). This sequence (attP) corresponds to positions 8544 to 8556 of the φRSM1 DNA, located between ORF14 and ORF1. Its nucleotide sequence showed no similarity to att sequences known for various Ff-like phages, including CTXφ, VGJφ, VSK, Vf33, f237, φLF, and Cf1c (5), but is identical to the 3′ end of the host R. solanacearum gene for serine tRNA (UCG) in the reverse orientation (Fig. 4D), suggesting that this tRNA gene serves as attB on the host genome. This φRSM-R. solanacearum integration system is obviously different from that mediated by host XerCD recombinases (18) suggested for other lysogenic filamentous phages (5).

FIG. 4.

Junctions of integrated φRSM1 DNA in the lysogenic strain R. solanacearum MAFF211270 genome. (A) Partial sequence of the 4.3-kbp HincII fragment containing attL of the strain MAFF211270 genomic DNA. The sequence is compared with the φRSM1 sequence. (B) Partial sequence of the 3.5-kbp HincII fragment containing attR of the strain MAFF211270 genomic DNA. The sequence is compared with the φRSM1 sequence. (C) Comparison of the attB, attP, attL, and attR sequences. The core sequences are shown by capital letters. (D) For sequence comparison, the serine tRNA (UCG) structure is also shown, along which a part of the attB sequence is aligned (indicated by shaded letters).

Characterization of the coat proteins and identification of their genes on the φRSS1 and φRSM1 genomes.

Purified φRSS1 phage particles were solubilized with SDS and subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 17.5% polyacrylamide gel. A major protein band of ∼10 kDa and four minor bands corresponding to 95 kDa (faint), 70 kDa, 31 kDa, and 21 kDa were separated (data not shown). The major protein band (∼10 kDa) was separated by Tricine (16%)-SDS-PAGE into three bands, 9.0 kDa, 7.7 kDa, and 6.0 kDa. From its abundance, the 6.0-kDa protein is thought to be the major coat protein building the helical capsid. The N-terminal six amino acid residues determined for this protein were AVPTDV and corresponded to positions of 26 to 31 of φRSS1 ORF4 (Table 1). Mature molecules of the major coat protein of 6.0 kDa consisted of 41 amino acids (aa), and a possible leader sequence of 25 aa was cleaved from the precursor protein, which coincided with the prediction of the SignalP program (data not shown). Identification of φRSS1 ORF4 as encoding the major capsid protein is consistent with the homology search result shown in Table 1 and supports the gene arrangement predicted for the φRSS1 genome in Fig. 1A.

When purified φRSM1 particles were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, six bands (80 kDa, 66 kDa, 40 kDa, 27 kDa, 25 kDa, and ∼10 kDa) were separated (data not shown). The major band (∼10 kDa) was separated into two bands by Tricine (16%)-SDS-PAGE. The major capsid band corresponding to 6.0 kDa was subjected to N-terminal peptide sequence analysis. The first seven amino acid residues could be determined as QTTTGGT, which coincided with the amino acid sequence of φRSM1 ORF8 (positions 22 to 27). This result confirmed the gene arrangement inferred from the homology search data (Fig. 1C). Mature molecules of the major coat protein of 6.0 kDa consisted of 51 aa, and a possible leader sequence of 20 aa was cleaved from the precursor protein, which coincided with the prediction of the SignalP program (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Integration of phage genomes into the host genome.

Compared with the φRSS1 genome, the φRSM1 genome (9,004 bases) is approximately 33% larger. This is mainly a result of an extended IG region between ORF11 (pI) and ORF12 and the presence of two additional ORFs (ORF13 and ORF14) located in reversed orientation in the putative regulatory module (Fig. 1C). No information is available about the biological significance of the IG region, which has an 80-bp region containing 80% GC (positions 5951 to 6030). The φRSM1 attP sequence determined as 5′-TGGCGGAGAGGGT-3′, identical to the 3′ end of the host serine tRNA (UCG) gene in the reversed orientation, was shown to be located next to ORF14. To our knowledge, the integration process of lysogenic filamentous phages generally involves site-specific recombination between the attP site of the phage and the attB sequence inside the dif site of the host chromosome. Phages exploit the XerC and XerD recombinase/resolvase of their host to integrate themselves into the bacterial genome (18). Most lysogenic filamentous phages, such as CTXφ and VGJφ of V. cholerae; Cf1c, Cf1t, and φLf of X. campestris; Xfφf1 of X. fastidiosa; and CVSφ-2 of Y. pestis, seem to use XerCD recombinases of their hosts and share attP sites with similar sequences (5). However, the φRSM1 attP core sequence is quite different from that of these phages, for example, 5′-TTTCGCATAATGTATA-3′ for φLf (accession no. X70328). This may suggest a different mechanism involved in the φRSM1-R. solanacearum integration system. It is well established that various kinds of temperate phages and plasmids use tRNA genes as their integration sites on host bacterial chromosomes (4, 12, 34). In such cases, a phage- or plasmid-encoded site-specific recombinase or integrase mediates integrative recombination. As seen in many P2-like phages, including P4, 186, R73, and φCTX, the 3′ ends of tRNA genes serve as attP genes and are closely associated with the integrase (int) gene (13, 25, 29, 37). For φRSM1, we suggest a possible involvement of phage-encoded functions for recombination such as ORF14 located next to the attP site. This ORF showed significant amino acid sequence homology to the resolvase of Pelodictyon phaeoclathratiforme (accession no. Q3VJH7, FASTA score of 582, E value of 4.4e-32) and the DNA invertase/recombinase of Marinobacter aquaeolei (accession no. Q36TJ9, FASTA score of 556, E-value of 2.8e-30). This is the first case of possible integration of a filamentous phage into a host tRNA gene (attB) by a phage-encoded integrase.

In addition to φRSM1, we also demonstrated the integration of φRSS1-like phages. The φRSS1 sequence at the integration site determined in strain C319 corresponds to position 6629 in the IG region, 34 nt upstream from ORF1. This phage site for integration appears to be specific because pJTPS1 is also integrated at the same approximate position in strain M4S. The nucleotide sequence around this position in φRSS1, 5′-CGC CTG CTA GAA TAT AAC CGA TTA, is not repeated at the junctions in the host genome and does not show any significant homology with the core sequence of att sites involved in the XerCD recombinase/resolvase integration (18). The detailed mechanism for host integration of φRSS-type phages is largely unknown.

Host selection by φRSS1 and φRSM1.

Bacteriophages φRSS1 and φRSM1 recognize different strains of R. solanacearum as hosts. Selective recognition of hosts with different types of pili was also reported for filamentous phages Pf1 and Pf3 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (16). Phage Pf1 was shown to bind to the type IV PAK pilus, whereas the RP4 pilus is the target of Pf3. The amino acid sequences of the pIII proteins, which are responsible for pilus recognition, are quite different between the two phages. However, the D1-D2-D3 domain structure conserved in Ff phages is also retained in both Pf1 and Pf3, indicating the conserved mechanisms of phage-host pilus interaction among a wide range of filamentous phages. Putative ORFs for pIII of φRSS1 (ORF7) and φRSM1 (ORF9) were identified in the structural module of their genomes (Fig. 1). Characteristic D1 and D3 domains were predicted in both ORFs, but the amino acid sequences were different from each other. These pIII proteins may interact with different (exclusive) receptors, pili on the host cells, resulting in the unique host specificity. In this context, it is interesting that the pJTPS1 phage, as demonstrated in this work, infects R. solanacearum strains that are also sensitive to φRSM1 but does not infect host strains of φRSS1. The overall nucleotide sequence of phage pJTPS1 is very similar to that of φRSS1 DNA, with variations in the pIII region and the IG region. In the pJTPS1 pIII coding region, approximately 360 nt in the middle portion are changed. This results in a pIII (ORF C5) with 15 fewer aa and more than 100 aa substitutions in the D2 domain of the protein. The N-terminal and C-terminal regions are unchanged. The changed domain of pIII might be responsible for discriminating the pilus type. Our previous Southern blot hybridization experiments revealed the frequent occurrence of φRSS1-related sequences in the genome of R. solanacearum strains irrespective of phage φRSS1 sensitivity. The hybridizing band patterns coincided well with phylogenetic groups of the bacterial strains. From these results, we speculate that φRSS-type phages with different host specificities (or a different pIII genes) frequently infect and are integrated into a variety of strains of R. solanacearum. The φRSS1-R. solanacearum system may provide a good opportunity to understand the molecular mechanism of pIII-pilus interaction and dynamic changes in their structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Naruto Furuya and the Leaf Tobacco Research Center, Japan Tobacco Inc., for providing R. solanacearum strains C319 and M4S, respectively.

This study was supported by the Industrial Technology Research Grant Program in 04A09505 from the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong, J., R. N. Perharm, and J. E. Walker. 1981. Domain structure of bacteriophage fd adsorption protein. FEBS Lett. 135:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F., R. Brent, R. E. Kjngston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1995. Short protocols in molecular biology, 3rd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

- 4.Campbell, A. M. 1992. Chromosomal insertion sites for phages and plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 174:7495-7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campos, J., E. Martinez, E. Suzarte, B. L. Rodriguez, K. Marrero, Y. Silva, T. Ledon, R. del Sol, and R. Fando. 2003. VGJf, a novel filamentous phage of Vibrio cholerae, integrates into the same chromosomal site as CTXf. J. Bacteriol. 185:5685-5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, B., H. Taniguchi, H. Miyamoto, and S. Yoshida. 1998. Filamentous bacteriophage of Vibrio parahaemolyticus as a possible clue to genetic transmission. J. Bacteriol. 180:5094-5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai, H., T. Y. Chow, H. J. Liao, Z. Y. Chen, and K. S. Chiang. 1988. Nucleotide sequence involved in the neolysogenic insertion of filamentous phage Cf16-v1 into the Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri chromosome. Virology 167:613-620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, B. M., E. H. Lawson, M. Sandkvist, A. Ali, S. Sozhamannan, and M. K. Waldor. 2000. Convergence of the secretory pathways for chlora toxin and the filamentous phage, CTXφ. Science 288:333-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebisu, S., Y. Murahashi, H. Takagi, K. Kadowaki, K. Yamaguchi, H. Yamagata, and S. Udaka. 1995. Nucleotide sequence and replication properties of the Bacillus borstelensis cryptic plasmid pHT926. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3154-3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furuya, N., S. Yamasaki, M. Nishioka, I. Shiraishi, K. Iiyama, and N. Matsuyama. 1997. Antimicrobial activities of pseudomonads against plant pathogenic organisms and efficacy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 7700 against bacterial wilt of tomato. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 65:417-424. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez, M. D., C. A. Lichtensteiger, R. Caughlan, and E. R. Vimr. 2002. Conserved filamentous prophage in Escherichia coli O18:K1:H7 and Yersinia pestis biovar orientalis. J. Bacteriol. 184:6050-6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hacker, J., G. Blum-Oehler, I. Muldorfer, and H. Tschape. 1997. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol. Microbiol. 23:1089-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser, M. A., and J. J. Scocca. 1990. Location of the host attachment site for phage HP1 within a cluster of Haemophilus influenzae tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayward, A. C. 2000. Ralstonia solanacearum, p. 32-42. In J. Lederberg (ed.) Encyclopedia of microbiology, vol. 4. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill, D. F., J. Short, N. R. Perharm, and G. B. Petersen. 1991. DNA sequence of the filamentous bacteriophage Pf1. J. Mol. Biol. 218:349-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland, S. J., C. Sanz, and R. N. Perham. 2006. Identification and specificity of pilus adsorption proteins of filamentous bacteriophages infecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Virology 345:540-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horita, M., and K. Tsuchiya. 2002. MAFF microorganism genetic resources manual no. 12, p. 5-8. National Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Tsukuba, Japan.

- 18.Huber, K. E., and M. K. Waldor. 2002. Filamentous phage integration requires the host recombinases XerC and XerD. Nature 417:656-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimsey, H. H., and M. K. Waldor. 1988. CTXφ immunity application in the development of cholera vaccines. Proc. Natl. acad. Sci. USA 95:7035-7039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo, T. T., Y. S. Chao, Y. H. Lin, B. Y. Lin, L. F. Liu, and T. Y. Feng. 1987. Integration of the DNA of filamentous bacteriophage Cf1t into the chromosomal DNA of its host. J. Virol. 61:60-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuo, T. T., Y. H. Lin, C. M. Huang, S. F. Chang, H. Dai, and T. Y. Feng. 1987. The lysogenic cycle of the filamentous phage Cf1t from Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri. Virology 156:305-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuo, T. T., M. S. Tan, M. T. Su, and M. K. Yang. 1991. Complete nucleotide sequence of filamentous phage Cf1c from Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin, N. T., R. Y. Chang, S. J. Lee, and Y. H. Tseng. 2001. Plasmids carrying cloned fragments of RF DNA from the filamentous phage phiLF can be integrated into the host chromosome via site-specific integration and homologous recombination. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindqvist, B. H., G. Deho, and R. Calendar. 1993. Mechanisms of genome propagation and helper exploitation by satellite phage P4. Microbiol. Rev. 57:683-702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marvin, D. A. 1998. Filamentous phage structure, infection and assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8:150-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Model, P., and M. Russel. 1988. Filamentous bacteriophages, p. 375-456. In R. Calendar (ed.), The bacteriophages, vol. 2. Plenum Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Negishi, H., T. Yamada, T. Shiraishi, H. Oku, and H. Tanaka. 1993. Pseudomonas solanacearum: plasmid pJTPS1 mediates a shift from the pathogenic to nonpathogenic phenotype. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 6:203-209. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierson, L. S., III, and K. L. Kahn. 1987. Integration of satellite bacteriophage P4 in Escherichia coli. DNA sequences of the phage and host regions involved in site-specific recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 196:487-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasched, I., and E. Oberer. 1986. Ff coliphages: structural and functional relationships. Microbiol. Rev. 50:401-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salanoubat, M., S. Genin, F. Artiguenave, J. Gouzy, S. Mangenot, M. Ariat, A. Billault, P. Brottier, J. C. Camus, L. Cattolico, M. Chandler, N. Choisene, S. Claudel-Renard, N. Cunnac, C. Gaspin, M. Lavie, A. Molsan, C. Robert, W. Saurin, T. Schlex, P. Siguier, P. Thebault, M. Whalen, P. Wincker, M. Levy, J. Weissenbach, and C. A. Boucher. 2002. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Nature 415:497-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 33.Schagger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Semsey, S., B. Blaha, K. Koles, L. Orosz, and P. Papp. 2002. Site-specific integrative elements of rhizobiophage 16-3 can integrate into proline tRNA (CGG) genes in different bacterial genera. J. Bacteriol. 184:177-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpson, A. J., et al. 2000. The genome sequence of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Nature 406:151-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Songsri, P., S. Hiramatsu, M. Fujie, and T. Yamada. 1997. Proteolytic processing of Chlorella virus CVK2 capsid proteins. Virology 227:252-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun, J., M. Inouye, and S. Inouye. 1991. Association of a retroelement with a P4-like cryptic prophage (retrophage φR73) integrated into the selenocystyl tRNA gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 173:4171-4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yabuuchi, E., V. Kosako, I. Yano, H. Hotta, and Y. Nishiuchi. 1995. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. nov.: proposal of Ralstonia picketii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff 1973) comb. nov., Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith 1896) comb. nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis 1969) comb. nov. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:897-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada, T., T. Kawasaki, S. Nagata, A. Fujiwara, S. Usami, and M. Fujie. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages that infect the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Microbiology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.