Abstract

In wild chimpanzees in the Taï National Park, Côte d'Ivoire, sudden deaths which were preceded by respiratory problems had been observed since 1999. Two new clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae were identified in deceased apes on the basis of multilocus sequence typing analysis and ply, lytA, and pbp2x sequences. The findings suggest that virulent S. pneumoniae occurs in populations of wild chimpanzees with the potential to cause infections similar to those observed in humans.

Bacterial human pathogens are important not only for therapeutic and socioeconomic reasons but also in respect to the evolution of infectious diseases. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major human pathogen causing a variety of diseases, including meningitis, sepsis, sinusitis, otitis media, and pneumonia. Pneumococci can colonize the nasopharynx and cause respiratory disease in several animal species, including rodents, racing horses (25), equine species (1), rhesus monkeys (5, 6), and chimpanzees (22). However, these cases occurred in animals that were held in human captivity, and it had been suggested that the animals had acquired the organisms from human contacts rather than being their natural hosts.

Wild chimpanzees in the Taï National Park, Côte d'Ivoire, have been closely monitored since the early 1980s (2). The three ape communities investigated here (North, South, and East) inhabit specific territories that overlap slightly with neighboring territories. The human observers permanently follow their behavior and health, but direct contact with the apes is not allowed and strict hygienic measures were progressively implemented when it became evident that diseases were a mortality factor (4). Such measures included, e.g., maintaining a distance of at least 7 m during daily follows and recently the wearing of a chirurgical mask when the animals are in sight (18) (F. Leendertz et al., submitted).

Since 1999, clusters of sudden deaths have been observed in three ape communities (North, East, and South communities), affecting animals that had been in good health. Necropsies were performed on 14 chimpanzees that died between 1999 and 2006. Samples were taken from lung tissue and all other organs and preserved in liquid nitrogen. In order to identify the organisms responsible for the animal infection, PCR analyses were performed on lung tissue samples from deceased individuals of these ape communities. In addition to virus diagnostics, PCR-based screens for bacteria were performed. In several cases, a new Bacillus anthracis-like species was detected and identified as the likely cause of the sudden deaths (14, 16). In the samples taken from the eight chimpanzees that showed symptoms and pathology of respiratory disease, subsequent experiments revealed rRNA genes from S. pneumoniae, and in none was B. anthracis detected.

In order to verify the presence of S. pneumoniae in the samples (Table 1), primers specific for pneumococcal virulence genes were tested in PCRs. Three S. pneumoniae-specific genes were investigated by DNA sequence comparison of PCR products covering internal gene fragments: ply, encoding the cytolysin pneumolysin (8); lytA, encoding the autolysin highly conserved in this species (12); and the pbp2x gene, encoding the penicillin target protein PBP2x, involved in beta-lactam resistance (7).

TABLE 1.

Demographic data on chimpanzee samples

| Chimpanzee name | Date of finding dead chimpanzee | Age (yr/mo) | Community | STb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loukoum | 05/10/1999 | 27a | North | 2308 |

| Lefkas | 05/14/1999 | 7/7 | North | 2308 |

| Candy | 02/16/2006 | Adulta | East | 2308 |

| Vasco | 02/09/2006 | Adulta | East | 2308 |

| Orest | 03/10/2004 | 5/10 | South | 2309 |

| Virunga | 03/19/2004 | 39a | South | 2309 |

| Ophelia | 03/10/2004 | 1/4 | South | 2309 |

| Ishas Baby | 02/09/2006 | 0/2 | South | 2309 |

Age estimated or unknown.

S. pneumoniae ST.

DNA was isolated from ape lung tissue using the DNeasy tissue kit or a viral RNA kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). From human pharyngeal swabs, DNA was isolated using the QIAmp DNA blood minikit. 16S rRNA sequences were amplified using bacterium-specific primers. The following oligonucleotides were used for PCR analysis of S. pneumoniae genes (3′→5′): ply, GAGGGTAATCAGCTACCC and GACCAAAGGACGCTCTGC; lytA, GCACATTGTTGGGAACGG and CCAGCCTGTCTTCATGGC; and pbp2x, GAAAGAAATTGCCAATTCACACG and GGATAAAGGCCGGAATTCC. PCR was performed under standard conditions with 30 cycles of 96°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min (for pbp2x, 2 min), followed by a 10-min period at 72°C.

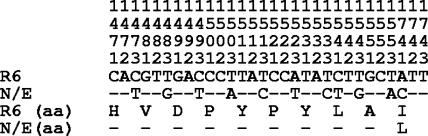

PCR fragments were obtained in all cases, and their DNA sequences were highly related to those of the laboratory strain S. pneumoniae R6, used as a representative of antibiotic-sensitive human isolates (9), confirming the presence of S. pneumoniae in the animal samples. PCR products were sequenced using the corresponding PCR primers and in the case of pbp2x a series of primers designed according to the published sequence (9). The PBP2x genes were identical in all cases but differed from pbp2x of the susceptible S. pneumoniae R6 strain by seven base pair changes that were scattered throughout the gene, resulting in one amino acid change, Leu565Val. No mosaic block common to pbp2x from penicillin-resistant strains was found, indicating that the sequences obtained from the chimpanzee samples are derived from penicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae strains (7, 15). The ply sequences were identical in all samples except for 1 nucleotide change in the North group and differed from the R6 sequences by 6 bp (South) or 7 bp (North group). The four lytA sequences obtained from the North and East samples were also identical but were distinct from those obtained from the South community samples: lytA contained an unusual highly altered region between codons 147 and 155, with 10 base pair changes that did not result in amino acid changes (Fig. 1), while bearing all typical pneumococcal signatures (20, 24). This mosaic block has not been observed in S. pneumoniae lytA previously. In addition, a single base pair change resulted in an amino acid mutation, Ile174 to Leu. The lytA sequence obtained from the South group was identical to that of the R6 gene. The amino acid mutation found in LytA of the South clone was located between the catalytic domain and the choline binding repeat domain of LytA at a position that presumably does not affect the function of the protein (3).

FIG. 1.

Sequence of the lytA gene obtained from the chimpanzee S. pneumoniae North/East clone. The S. pneumoniae R6 lytA sequence is used for comparison; N/E refers to the S. pneumoniae North/East clone. The vertical numbers indicate the codon, with the fourth digit representing the position within the codon. The amino acid sequence is indicated below (aa). Only nucleotides and amino acids that differ from those of the R6 sequence are shown.

The autolysin LytA is required for release of the pneumolysin Ply, a cytolysin which results in severe damage of the host cells (12). Thus, the presence of ply and lytA, both of which represent pathogenicity factors, in all samples strongly suggests that the chimpanzees contained S. pneumoniae strains with the potential to be virulent.

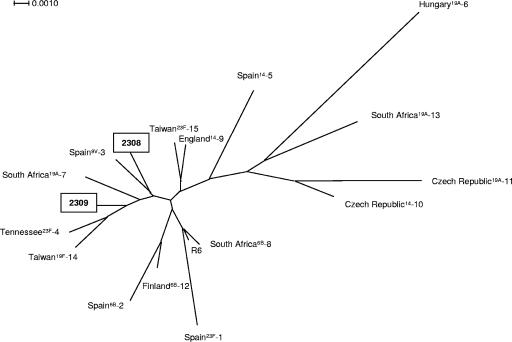

In order to determine the clonal relatedness of the ape pneumococci, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analyses were performed and PCR fragments of all seven housekeeping genes were obtained from eight samples. Standard primers (http://spneumoniae.mlst.net/misc/info.asp) were used, except for gdh (CCCTCCGTGACATGGTCC and GTCATGAAGTGGGGCACC), gki (CTTGGATTGGCAGCAGCG and GATGTGCGTACTTGTGGG), and spi (ACGCTTAGAAAGGTAAGTTATG and GGTTTCTTAAAATGTTCCGATAC). Again, the sequences from samples of the North and East communities were identical (Table 2). A new spi allele was identified, and a new sequence type (ST), 2308, was assigned to this virtual S. pneumoniae clone. The MLST data obtained from the ape samples of the South community were distinct, including a new gdh allele, resulting in the new ST 2309. Phylogenetic analysis was performed with the concatenated sequences of the MLST genes used for S. pneumoniae (www.mlst.net) with the SplitsTree4 program (10). A neighbor-joining tree was constructed using uncorrected parameters, and the tree was tested by bootstrap analysis using 1,000 replicates. A dendrogram of the genetic relationships between the concatenated gene sequences of the MLST genes from the chimpanzee samples and a selection of major clones of human S. pneumoniae isolates representing major recognized clones worldwide (21) is shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 2.

Allelic profile of seven housekeeping genes and ST of new S. pneumoniae clones from chimpanzees and closest human isolates

| S. pneumoniae isolate | Allele no. for genea:

|

ST | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aroE | gdh | gki | recP | spi | xpt | ddl | ||

| “North/East clone” | 8 | 134 | 4 | 4 | 132* | 142 | 74 | 2308 |

| Closest human isolatesb | ||||||||

| 2061 (19A/Spain) | 8 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 2109 |

| 6A-12 (6A/United States) | 8 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 14 | 2154 |

| 3852 (4/Poland) | 8 | 70 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 116 | 6 | 2190 |

| “South clone” | 8 | 138* | 74 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 161 | 2309 |

| Closest human isolates | ||||||||

| M16 (23A/United Kingdom) | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 190 |

| 263/99 (23F/Norway) | 2 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 65 | 322 |

| 2828-02 (13/Kenya) | 1 | 11 | 74 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 18 | 701 |

*, New allele.

Closest human isolates identified by comparison of the allelic profiles listed at http://spneumoniae.mlst.net/. The strain number is indicated in addition to the serotype and the country of isolation.

FIG. 2.

Genetic relatedness of the chimpanzee S. pneumoniae clones to major clones of S. pneumoniae as described recently (21). Clones are identified by the country of isolation, followed by the serotype and the clone identification number. A SplitsTree representation is shown based on concatenated sequences of the seven housekeeping genes used for MLST analysis (10). The STs 2308 and 2309 were assigned to the chimpanzee S. pneumoniae clones.

In order to investigate whether the putative S. pneumoniae clones also occur in humans working in proximity to the chimpanzees, a total of 39 samples from 28 African and European workers of the Taï chimpanzee project taken at different time points between 2004 and 2006 were screened for S. pneumoniae. All samples were preserved in liquid nitrogen. Samples from 21 workers were positive, but none contained the new gdh or spi allele identified in the chimpanzees. A search in the MLST database (http://spneumoniae.mlst.net) showed that the most closely related human isolates, all of which were isolated in Europe, differed by three alleles from the North/East clone and by at least five alleles from the South clone (Table 2). These data strongly suggest that the pneumococci identified in the chimpanzees were not transferred from humans to the animals. Although we cannot rule out that transfer occurred prior to the time when the humans were tested, it seems unlikely given the fact that close contact between humans and the wild animals is carefully being avoided.

The areas inhabited by the ape communities are adjacent to each other. Many contacts between the chimpanzees of neighboring groups have been observed, but not between the North and East groups, since they have no adjacent frontiers. In other words, the S. pneumoniae clone identified in the South community was distinct from that identified in the East community although contact between these groups occurred, whereas the same S. pneumoniae clone was associated with the North and East groups, where contacts have not been observed. This suggests that S. pneumoniae might also be associated with other animals in these areas. Potential candidates for this scenario are monkeys that are part of the ape diet, or perhaps small rodents, and further investigations are required to understand the occurrence of S. pneumoniae in animals from wild habitats.

The cause of death of the animals is likely to be multifactorial, although S. pneumoniae infections could play a role in the severity of the disease. The pathological and histopathologic changes were consistent with the picture of a severe purulent multifocal bronchopneumonia, lung edema, and upper respiratory tract infection. In most samples, DNA from other pathogens could also be amplified, including rRNA from Pasteurella spp., human metapneumovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus; details will be described elsewhere (Leendertz et al., submitted). Recent findings at a primate rehabilitation unit demonstrated that viral upper respiratory tract infections can predispose chimpanzees to invasive infections caused by S. pneumoniae (13). It would be important to isolate the infectious S. pneumoniae from the wild chimpanzees in order to elucidate further properties of these strains, such as the capsular type, and preferably genomic data should be generated.

In this study we have shown for the first time that the human pathogen S. pneumoniae is also associated with disease in wild apes. The focus of most previous studies on captive or wild-living nonhuman primates was on the transmission of retroviruses, such as simian immunodeficiency virus, simian T-cell leukemia virus, and foamy virus or highly acute diseases such as Ebola (11, 17, 19, 23, 26, 27), documenting that pathogens found in primates can easily spread to humans with fatal consequences. Our data show that other microbial agents pathogenic for humans can be found in great apes, emphasizing the importance of monitoring of mortality rates of wild primates combined with broad pathogen-screening programs. Understanding the routes of transfer between the chimpanzees and the existence of other potential natural hosts for this human pathogen are major challenges for future research.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ivorian authorities for long-term support, especially the Ministry of the Environment and Forests, as well as the Ministry of Research, the directorship of the Taï National Park, and the Swiss Research Center in Abidjan. We also thank the assistants of the Taï Chimpanzee Project for their help during observation of the chimpanzees. We thank Pierre Formenty for performing the necropsy of two chimpanzees of the North group considered in this paper. The skillful technical support of N. Eckhardt for necropsies and of Sonja Schröck of the Nano+Bio Center at Kaiserslautern and Ute Buwitt and Julia Tesch at the Robert Koch Institute for DNA sequencing is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by the BMBF (PTJ-BIO/0313134), the EU (LSHM-CT-2003-503413), the Stiftung Rheinland Pfalz für Innovation (0580), and the Max Planck Society.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 22 June 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benson, C. E., and C. R. Sweeney. 1984. Isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 3 from equine species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:1028-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boesch, C., and H. Boesch-Achermann. 2000. The chimpanzees of the Tai Forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 3.Fernandez-Tornero, C., R. Lopez, E. Garcia, G. Gimenez-Gallego, and A. Romero. 2001. A novel solenoid fold in the cell wall anchoring domain of the pneumococcal virulence factor LytA. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:1020-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Formenty, P., C. Boesch, M. Wyers, C. Steiner, F. Donati, F. Dind, F. Walker, and B. Le Guenno. 1999. Ebola virus outbreak among wild chimpanzees living in a rain forest of Cote d'Ivoire. J. Infect. Dis. 179:S120-S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox, J. G., and O. A. Soave. 1971. Pneumococcic meningoencephalitis in a rhesus monkey. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 159:1595-1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox, J. G., and S. E. Wikse. 1971. Bacterial meningoencephalitis in rhesus monkeys: clinical and pathological features. Lab. Anim. Sci. 21:558-563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakenbeck, R., K. Kaminski, A. König, M. van der Linden, J. Paik, P. Reichmann, and D. Zähner. 1999. Penicillin-binding proteins in β-lactam-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 5:91-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirst, R. A., A. Kadioglu, C. O'Callaghan, and P. W. Andrew. 2004. The role of pneumolysin in pneumococcal pneumonia and meningitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 138:195-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, Jr., J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D.-J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. J. Khoja, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. Q. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, J. O'Gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P.-M. Sun, J. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, S. R. Jaskunas, P. R. J. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huson, D. H. 1998. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 14:68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain, A. I., V. Shanmugam, V. B. Bhullar, D. Vallet, A. Gautier-Hion, N. D. Wolfe, W. B. Karesh, A. M. Kilbourn, Z. Tooze, W. Heneine, and W. M. Switzer. 2003. Screening for simian foamy virus infection by using a combined antigen Western blot assay: evidence for a wide distribution among Old World primates and identification of four new divergent viruses. Virology 309:248-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jedrzejas, M. J. 2001. Pneumococcal virulence factors: structure and function. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:187-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones, E. E., P. I. Alford, A. L. Reigold, H. Russel, M. E. Keeling, and C. V. Broome. 1984. Predisposition to invasive pneumococcal illness following parainfluenza type 3 virus infection in chimpanzees. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 185:1351-1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klee, S. R., M. Ozel, B. Appel, C. Boesch, H. Ellerbrok, D. Jacob, G. Holland, F. H. Leendertz, G. Pauli, R. Grunow, and H. Nattermann. 2006. Characterization of Bacillus anthracis-like bacteria isolated from wild great apes from Cote d'Ivoire and Cameroon. J. Bacteriol. 188:5333-5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laible, G., B. G. Spratt, and R. Hakenbeck. 1991. Inter-species recombinational events during the evolution of altered PBP 2x genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1993-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leendertz, F. H., H. Ellerbrok, C. Boesch, E. Couacy-Hymann, K. Mätz-Rensing, R. Hakenbeck, C. Bergmann, P. Abaza, S. Junglen, Y. Moebius, L. Vigilant, P. Formenty, and G. Pauli. 2004. Anthrax kills wild chimpanzees in a tropical rainforest. Nature 430:451-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leendertz, F. H., S. Junglen, C. Boesch, P. Formenty, E. Couacy-Hymann, V. Courgnaud, G. Pauli, and H. Ellerbrok. 2004. High variety of different simian T-cell leukemia virus type 1 strains in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) of the Tai National Park, Cote d'Ivoire. J. Virol. 78:4352-4356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leendertz, F. H., F. Lankester, P. Guislain, C. Neel, O. Drori, J. Dupain, S. Speede, P. Reed, N. Wolfe, S. Loul, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, M. Peeters, C. Boesch, G. Pauli, H. Ellerbrok, and E. M. Leroy. 2006. Anthrax in Western and Central African great apes. Am. J. Primatol. 68:928-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leroy, E. M., P. Rouquet, P. Formenty, S. Souquiere, A. Kilbourne, J. M. Froment, M. Bermejo, S. Smitk, W. Karesh, R. Wanepoel, S. R. Zaki, and P. E. Rollin. 2004. Multiple Ebola virus transmission events and rapid decline of central African wildlife. Science 303:387-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Llull, D., R. López, and E. García. 2006. Characteristic signatures of the lytA gene provide a basis for rapid and reliable diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 44:1250-1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGee, L., L. McDougal, J. Zhou, B. G. Spratt, F. C. Tenover, R. George, R. Hakenbeck, W. Hryniewicz, J. C. Lefevre, A. Tomasz, and K. P. Klugman. 2001. Nomenclature of major antimicrobial-resistant clones of Streptococcus pneumoniae defined by the Pneumococcal Molecular Epidemiological Network (PMEN). J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2565-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solleveld, H. A., M. J. van Zwieten, P. J. Heidt, and P. M. van Eerd. 1984. Clinicopathologic study of six cases of meningitis and meningoencephalitis in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Lab. Anim. Sci. 34:86-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Heuverswyn, F., Y. Li, C. Neel, E. Bailes, B. F. Keele, W. Liu, S. Loul, C. Butel, F. Liegeois, Y. Beinvenue, E. M. Ngolle, P. M. Sharp, G. M. Shaw, E. Delaporte, B. H. Hahn, and M. Peeters. 2006. Human immunodeficiency viruses: SIV infection in wild gorillas. Nature 444:164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whatmore, A. M., and C. G. Dowson. 1999. The autolysin-encoding gene (lytA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae displays restricted allelic variation despite localized recombination events with genes of pneumococcal bacteriophage encoding cell wall lytic enzymes. Infect. Immun. 67:4551-4556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whatmore, A. M., S. J. King, N. C. Doherty, D. Sturgeon, N. Chanter, and C. G. Dowson. 1999. Molecular characterization of equine isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae: natural disruption of genes encoding the virulence factors pneumolysin and autolysin. Infect. Immun. 67:2776-2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe, N. D., W. Heneine, J. K. Carr, A. D. Garcia, V. Shanmugam, U. Tamoufe, J. N. Torimiro, A. T. Prosser, M. Lebreton, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, F. E. McCutchan, D. L. Birx, T. M. Folks, D. S. Burke, and W. M. Switzer. 2005. Emergence of unique primate T-lymphotropic viruses among central African bushmeat hunters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:7994-7999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolfe, N. D., W. M. Switzer, J. K. Carr, V. B. Bhullar, V. Shanmugam, U. Tamoufe, A. T. Prosser, J. N. Torimiro, A. Wright, E. Mpoudi-Ngole, F. E. McCutchan, D. L. Birx, T. M. Folks, D. S. Burke, and W. Heneine. 2004. Naturally acquired simian retrovirus infections in central African hunters. Lancet 363:932-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]