Abstract

mRNA cap 1 2′-O-ribose methylation is a widespread modification that is implicated in processing, trafficking, and translational control in eukaryotic systems. The eukaryotic enzyme has yet to be identified. In kinetoplastid flagellates trans-splicing of spliced leader (SL) to polycistronic precursors conveys a hypermethylated cap 4, including a cap 0 m7G and seven additional methylations on the first 4 nucleotides, to all nuclear mRNAs. We report the first eukaryotic cap 1 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase, TbMTr1, a member of a conserved family of viral and eukaryotic enzymes. Recombinant TbMTr1 methylates the ribose of the first nucleotide of an m7G-capped substrate. Knockdowns and null mutants of TbMTr1 in Trypanosoma brucei grow normally, with loss of 2′-O-ribose methylation at cap 1 on substrate SL RNA and U1 small nuclear RNA. TbMTr1-null cells have an accumulation of cap 0 substrate without further methylation, while spliced mRNA is modified efficiently at position 4 in the absence of 2′-O-ribose methylation at position 1; downstream cap 4 methylations are independent of cap 1. Based on TbMTr1-green fluorescent protein localization, 2′-O-ribose methylation at position 1 occurs in the nucleus. Accumulation of 3′-extended SL RNA substrate indicates a delay in processing and suggests a synergistic role for cap 1 in maturation.

The m7G cap on eukaryotic mRNA plays essential roles in translation and stability, and the enzymatic activities responsible for its formation are well characterized (48, 50). Additional modifications of adjacent nucleotides on mRNA and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) are well documented; however, the identity of the eukaryotic cap ribose-methylating enzyme(s) and the function of cap modification beyond the m7G attached to the first-transcribed nucleotide (cap 0) remain unclear (6, 18). 2′-O-Ribose methylation is a common modification of RNA (29) that can occur via two mechanisms: box C/D snoRNA-guided methylation by fibrillarin (12) and nucleotide-specific enzymes (31, 43, 54). The conservation of modified nucleotides in functionally important regions indicates a major benefit to the cell (13). Individual methylations of tRNA are not essential for viability; however, their cumulative loss is detrimental (1). Potential functions for mRNA 2′-O-ribose methylation include roles in processing and trafficking of transcripts, as well as translational control (4, 45).

Protein-encoding genes of kinetoplastid protozoa, including the human-pathogenic Leishmania major, Trypanosoma brucei, and Trypanosoma cruzi, are transcribed polycistronically (23, 36). The discrete spliced leader (SL) RNA serves as donor of its first 39 nucleotides (nt) and unique cap structure to all coding regions via trans-splicing. In addition to m7G, the hypermethylated cap 4 structure includes 2′-O-ribose methylations of the first 4 nt (AACU) with additional base methylations on the first (m26A) and fourth (m3U) positions (5, 16, 41). The 5′ processing of SL is accompanied by association of the transcript with an Sm complex between two stem-loop structures in the intron (35, 51, 65) and 3′ trimming of residual nucleotides from attenuated transcription termination in the downstream T tract (51, 66). Other eukaryotic mRNA caps vary from those containing only cap 0 to those modified by 2′-O-ribose methylation(s) at the first or the first and second nucleotides, known as cap 1 and cap 2, respectively (17). Among higher eukaryotes cap ribose modifications are conserved, and the majority of mRNAs are ribose methylated in mammals (4).

The unique kinetoplastid cap 4 structure is implicated both in trans-splicing and in translation. Substrate SLs with incomplete cap 4 are trans spliced (52); however, these mRNAs do not associate with polysomes (68), suggesting a role for cap 4, the primary SL sequence, or both in translation. Two cap 2′-O-ribose methyltransferases (MTases), TbMT417 and TbMT511, that modify the second and third positions of cap 4, are dispensable for survival of T. brucei (2, 3, 64). These relatives of the vaccinia virus cap 1 MTase will henceforth be referred to as TbMTr2 and TMTr3, respectively, to reflect their functional roles. With no requirement for TbMTr2 and TbMTr3 activities for viability, the focus for a critical component of cap 4 turned to position 1.

The kinetoplastid U1 snRNA contains the same first 4 nt as SL RNA but identical hypermethylation of only the first two positions in the monogenetic kinetoplastid Crithidia fasciculata (47). In contrast to SL RNA, an RNA polymerase (pol) II transcript, the U1 snRNA, is transcribed by RNA pol III and ultimately acquires a trimethylated m2,2,7G (TMG) cap (14). The U1 snRNA contains an Sm binding sequence that likely results in formation of the core Sm-protein complex (39, 40, 58). Knockdown of TbMTr2 had no effect on U1 snRNA cap structure in T. brucei (64).

Here we identify the cap 1 2′-O-ribose MTase of SL RNA in T. brucei, TbMTr1, representing the first functionally characterized member of a group of widely conserved eukaryotic MTases. S-Adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)-dependent, cap 1 2′-O-ribose MTase activity is shown in vitro. No growth defect was detected in knockdown or TbMTr1-null lines beyond a loss of cap 1 methylation on both substrate SL RNA and U1 snRNA and a corresponding accumulation of substrate SL 3′-extended forms. TbMTr1 is a portal for identification of other eukaryotic cap 1 MTases and for understanding the functional significance of these modifications in eukaryotic mRNA and snRNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence analyses.

Sequence database searches were carried out with PSI-BLAST, starting with the putative ribose MTases from trypanosomes, predicted in earlier analyses (15). Phylogenetic analyses were carried out with MEGA 3.1 (26).

DNA cloning and RNAi constructions.

The 1,110-bp open reading frame (ORF) for TbMTr1 (GeneDB no. Tb10.6k15.2610) was amplified using MT370 Xba-F (5′-GGTCT AGAAT GCCTG CCGTT GCAGA C) and MT370 xh/xb R (5′-GGCTC GAGTC TAGAT GACTT GACCT CCTCC ATTGC) and cloned into pTOPO-TA (Invitrogen). The insert was released with XbaI and subcloned into the pR hairpin-loop RNA interference (RNAi) vector. The pGR vector was made from pLEW100 for creation of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins and hairpin-loop, double-stranded RNAi formation and is available upon request. The pRTbMT370 vector was made by digestion of pGMT370 with AscI and XhoI. The XhoI site was filled with Klenow fragment, gel purified, and inserted into pGMT370 digested with HpaI and MluI. For inducible RNAi in a vector with opposing promoters, part of TbMTr1 was amplified using MT370Fw (5′-CTCGA GGCGC CACGA CCCAG CTTCC) and MT370Rv (5′-GGATC CCACG ACTTC GGTGG GAACG) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). The insert was released with XhoI and BamHI and cloned into p2T7-177 vector (60). Inserts in all vectors were verified by sequencing. Elimination of TbMTr1 alleles to create the TbMTr1-null cell lines used pKO vectors (28) where drug selection cassettes were replaced with phleomycin and puromycin resistance markers. The 426-nt, 5′ untranslated region (UTR) directly upstream of the start codon was cloned using TbMT370-5′UTR-F-HindIII (5′-AAAGC TTAAA GTCTA TACAA CTGC) and TbMT370-5′UTR-R-EcoRI (5′-TGAAT TCGGC ATCAG AGAAA TA). The 598-nt 3′ UTR was cloned using TbMT370-3′UTR-F-Xba (5′-ATCTA GACAA GTCAT AGGTA GTCC) and TbMT370-3′UTR-R-NotI (5′-TGCGG CCGCT GAATA TTTCT CCAC). Both were inserted into pKOpuro and pKOphleo vectors and transfected into YTAT cells, selected with either puromycin (30 μg/ml) or zeocin (20 μg/ml; Invitrogen).

In vitro activity assay.

Recombinant TbMTr1 with a T. bracie N-terminal six-histidine (His6) tag was overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells and purified to homogeneity by Ni column and phosphocellulose chromatography procedures. Synthetic RNA substrate identical to T. brucei SL RNA, except for guanosine at position 2 for transcriptional efficiency, was synthesized using PCR-amplified DNA template that allows for transcription of the T. brucei SL RNA gene from the T7Φ 2.5 promoter (11). The 142-nt RNA was capped using [α-32P]GTP and vaccinia virus RNA guanylyltransferase (Ambion) as described by the manufacturer in the presence of 1 mM AdoMet. Radiolabeled RNA was purified by extraction with phenol-chloroform, followed by spin column chromatography. Cap 1 MTase activity was assayed by incubating radiolabeled RNA with recombinant TbMTr1 for 1 h at 28°C followed by RNA extraction with phenol-chloroform, ethanol precipitation, and digestion with 5 μg nuclease P1 in 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.3, for 1 h at 37°C. RNA samples were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on polyethyleneimine cellulose plates developed in 0.45 M ammonium sulfate (62). TLC results were visualized with a PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences).

RNAi strains and cell culture.

Procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 (61) containing T7 RNA pol and tetracycline (Tet) repressor genes was grown at 27°C in SM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in the presence of hygromycin (50 μg/ml; PGC Scientific) and G418 (15 μg/ml; ICN). The pRTbMT370 and p2T7-177-370 constructions were each transfected into 29-13 cells by electroporation (59). Drug-resistant T. brucei strains were cloned by limiting dilution in supplemented SM medium in the presence of G418, hygromycin, and zeocin. RNAi was induced by addition of 100 ng/ml Tet to clonal pRTbMT370 and p2T7-177-370 cells at 1 × 106 cells/ml, and growth was assayed using a Coulter Counter (Beckman-Coulter).

RNA analyses.

Total cell RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as described previously (66). High-resolution acrylamide RNA blotting, RNA primer extension using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT), and DNA sequencing reactions were performed as described previously (51, 52, 66) using the γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotides TbWTexon (5′-CAATA TAGTA CAGAA ACTG) or intron-specific TbSL-40 (5′-CTACT GGGAG CTTCT CATAC). U1 snRNA extensions were performed with TbU1-40 (5′-CCCAC TCAAA GTTTA CTG). Low-resolution formaldehyde agarose RNA blots were generated as described previously (52), hybridized with [α-32P]CTP-incorporated random hexamer-primed probes (Amersham Biosciences), and visualized with a PhosphorImager. Poly(A)+ mRNA was isolated using the MicroPoly(A) Purist kit (Ambion). RNA blot hybridizations were performed with TbStloop1 (5′-CTACT GGGAG CTTCT CATCA), TbU1-20 (5′-CAAGC ACGGC GCTTT CGTGA), and 5S rRNA (5′-TAACT TCACA AATCG GACGG GAT).

RNase T2 cap analysis.

mRNA from each cell line was purified using the MicroPoly(A) Purist mRNA purification kit (Ambion), starting with 10 μg of total RNA. To label the cap structure, 300 ng of mRNA was decapped with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (5 U; Roche) for 1 h at 37°C in the provided reaction buffer. The phosphate was removed using HK phosphatase (2 U; Epicenter) for 1 h at 30°C. The RNA was extracted twice with phenol, ethanol precipitated, and end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. The radiolabeled RNA was digested in 50 mM ammonium acetate (pH 4.5) and 2 mM EDTA with 40 U/ml RNase T2 at 37°C for 12 h. Digestion products were resolved on 25% acrylamide-8 M urea gels and visualized with a PhosphorImager.

Subcellular localization of TbMTr1.

The coding region from nt 1001 to 2110 was amplified with pC-PTP-NEO370F (5′-AGGGC CCATG CCTGC CGTTG) and MT370 xh/xb R (5′-GGCTC GAGTC TAGAT GACTT GACCT CCTCC ATTGC), digested with ApaI and XhoI for insertion into the pMOT4G vector for in situ GFP tagging (38). The same 3′ UTR used for pKO vectors amplified with BamHI370-3′UTR-F (5′-AGGAT CCCAA GTCAT AGGTA GTCC) was inserted using BamH and NotI sites. Plasmid (10 μg) was digested with ApaI and NotI, and the released fragment was gel purified and electroporated into KH4A YTAT T. brucei. Stable transfectants were selected with 50 μg/ml hygromycin, and clonal cell lines were made by limiting dilution. Clonal lines were rinsed and washed once in phosphate-buffered saline containing 100 ng/ml of 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) for 5 min at room temperature. Live cells were mounted on microscope slides and visualized with a Zeiss Axiocam compound fluorescence microscope fitted with a Zeiss 63× objective and a digital camera. Images were captured with Zeiss Axiovision software and compiled for publication with Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe).

RESULTS

TbMT370 and conserved viral and eukaryotic 2′-O-ribose MTases.

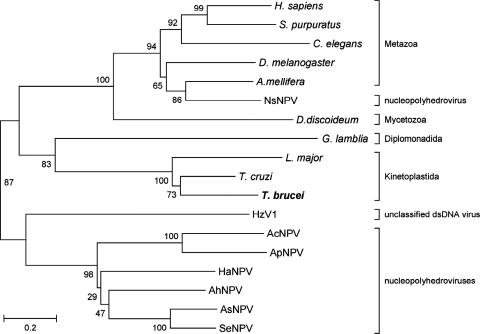

Phylogenetic analysis of the RrmJ superfamily of ribose 2′-O-ribose MTases revealed a conserved group of uncharacterized eukaryotic MTases (15) that includes a putative T. brucei MTase encoded in a 370-amino-acid ORF that we named TbMT370 (GeneDB no. Tb10.6k15.2610). TbMT370 is conserved among the kinetoplastids with homologs in T. cruzi (GeneDB no. Tc00.1047053506247.320) and L. major (GeneDB no. LmjF36.6660). In contrast to the TbMTr2 and TbMTr3 vaccinia virus-like MTases that were unique to kinetoplastids, database searches for TbMT370 homologs revealed a family of proteins with members from metazoa, protists, and double-stranded DNA viruses that share at least 10 conserved motifs spread throughout the ORF (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), including only one functionally characterized cap 1 MTase, orf69 from the alfalfa looper moth Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (62). All members contained the characteristic K-D-K-E tetrad common to 2′-O-ribose MTases (9, 15). Phylogenetic analysis of the family showed two branches containing viral and cellular proteins (Fig. 1). Interestingly, orf5 from European pine sawfly Neodiprion sertifer nucleopolyhedrovirus branched with cellular proteins from insects, suggesting a horizontal transfer from its host. The family also includes a human ortholog of TbMT370. The gene encoding the human cap 1 2′-O-ribose MTase has yet to be identified functionally, though its activity was partially purified and characterized (30).

FIG. 1.

Phylogeny of a 2′-O-ribose MTase family. Shown is a phylogenetic tree of sequences calculated with the neighbor joining method and the JTT matrix (24). Values at the nodes indicate the percent bootstrap support. The main taxa are indicated.

To determine whether a eukaryotic family member possesses cap 1 MTase activity, we assayed TbMT370 for activity both in vitro and in vivo, specifically as a candidate for SL cap 1 2′-O-ribose methylation.

TbMT370 has AdoMet-dependent, 2′-O-ribose MTase cap 1 activity in vitro.

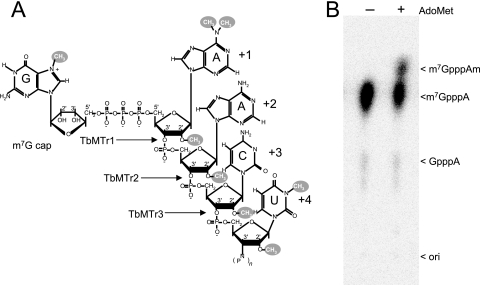

Two of the enzymes performing cap 4 2′-O-ribose methylations have been identified (Fig. 2A). A biochemical approach was initiated for the in vitro evaluation of TbMT370 for 2′-O-ribose MTase activity. Recombinant TbMT370 was expressed with a His6 tag for bacterial purification.

FIG. 2.

TbMTr1 has in vitro 2′-O-ribose MTase cap 1 activity. (A) The cap 4 structure and identified enzymes. (B) α-32P-labeled m7G-capped transcript was incubated with recombinant TbMT370 in the presence (+) and absence (−) of AdoMet. Following digestion with nuclease P1, resistant cap dinucleotides were resolved by TLC. Dinucleotide identities are listed at the right. ori, origin of spotting.

Recombinant TbMT370 was purified to homogeneity from E. coli. In vitro-transcribed 142-nt RNA was capped with the vaccinia virus m7G capping enzyme using radiolabeled [α-32P]GTP. This cap 0 transcript was incubated with purified recombinant TbMT370 in the presence and absence of methyl donor AdoMet. To liberate the 5′-5′-linked dinucleotides for analysis, the RNA was extracted and digested with nuclease P1, a nonspecific RNA endonuclease that is unable to cleave the 5′-5′ triphosphate bond of the labeled m7G. TLC resolved the radiolabeled dinucleotides, through which methylated species migrate farther than the m7GpppA unmodified marker. In the presence of AdoMet, an m7GpppAm species was generated that migrated faster than the m7GpppA marker due to ribose methylation on the first nucleotide (Fig. 2B). To confirm the location of the methylation, modified substrate was subjected to RNase T2 digestion, which is inhibited by ribose 2′-O-ribose methylation. RNase T2 treatment yielded a product consistent with in vitro cap 1 formation (data not shown). The in-depth biochemical characterization of this protein will be presented elsewhere.

The cap 1 2′-O-ribose MTase activity of TbMT370 is the first of its kind ascribed to a eukaryotic cellular protein. The enzyme was renamed TbMTr1 to reflect its function. To query TbMTr1 for a role in SL cap 4, we next determined its in vivo substrates.

5′ and 3′ SL RNA phenotypes in TbMTr1 RNAi knockdown cells.

Ribose modifications at positions 2, 3, and 4 are not essential, leaving position 1 ribose and base methylations as potentially pivotal players in cap 4. To challenge the role of TbMTr1 in cap 1 methylation of SL, we performed RNAi-mediated knockdown of the transcript using Tet-inducible hairpin-loop and opposing-T7-promoter RNAi constructions. If induced cells are not viable, RNAi lines allow the cap 1 status of the target transcripts to be assessed at various times between induction and cell death.

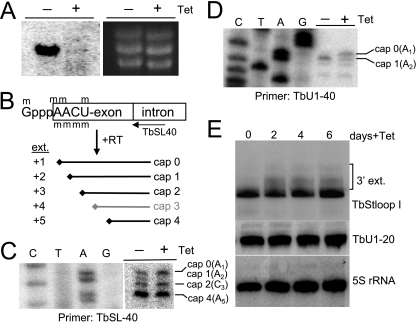

RNAi cell lines made with either vector showed no significant growth defects 9 days postinduction (data not shown). Total RNA samples were collected at day 9 and probed for the coding region of TbMTr1. The induced samples showed efficient knockdown of the target transcript (Fig. 3A); thus, the lack of TbMTr1 was judged to be acceptable to the cells. We then used substrate-specific primer extension to examine the cap structure of prespliced, substrate SL RNA in TbMTr1 knockdowns. To capture cap intermediates during cap 4 formation in this assay, a radiolabeled primer was extended with RT, and extension was inhibited by the presence of a methylation on either a base or a ribose moiety (Fig. 3B); a stop corresponding to cap 3 is rarely seen in wild-type profiles, suggesting that addition of cap 3 is followed rapidly by cap 4 and supporting our hypothesis that TbMTr3 is performing 2′-O-ribose methylation of the adjacent position (64). The profile of the 3′-most methylations was mapped by electrophoresis of the extension products through a 6% polyacrylamide gel in parallel with the corresponding DNA sequence. In wild-type cells nucleotide A1 of the SL is both modified at the 2′-O of the ribose and dimethylated at the N6 position of the adenine ring (5), and either is sufficient to inhibit extension by RT (27, 33). Since TbMTr1 showed in vitro cap 1 ribose methylation activity, we expected to detect a difference in SL intermediate population only if loss of both position 1 modifications occurred in RNAi cell lines. Compared to the noninduced samples, a decrease of the band comigrating with A2 was observed, corresponding to an absence of cap 1 modification (Fig. 3C). As TbMTr1 RNA knockdown resulted in reduction of SL A2-extension termination and the in vitro activity showed 2′-O-ribose MTase cap 1 activity, we concluded that TbMTr1 methylates the ribose of position 1 of the SL and that cap 1 is not required for cell viability. The SL intermediate with only base dimethylation at A1 was not detected and thus is unlikely to precede 2′-O-ribose methylation in cap 4 biogenesis.

FIG. 3.

RNAi of TbMTr1 induces defects in SL RNA and U1 snRNA methylation and SL RNA 3′-end formation. (A) RNA collected after 9 days from pRTbMTr1 cells grown in the presence (+) and absence (−) of Tet was run on a 1.1% formaldehyde agarose gel, blotted, and probed with the TbMTr1 coding region. Ethidium bromide-stained rRNA is a loading control. (B) Schematic of the cap 4 showing possible primer extension products and interpretations of intermediate cap structures. (C) Primer extension analysis of SL RNA using total RNA from clonal pRTbMTr1 RNAi cell lines 9 days after Tet induction. Extension products were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel and run next to the cognate sequence ladder. (D) Primer extension analysis of the U1 snRNA in pRTbMTr1 RNAi samples. (E) Size analysis of SL RNA and U1 snRNA by medium-resolution acrylamide RNA blotting using oligonucleotide probes TbStloopI and TbU1-20, respectively. The number of days post-Tet addition is indicated. 5S rRNA served as a loading control.

Kinetoplastid U1 snRNA shares 6 of the first 7 nt with the SL and identical methylations at position 1 in Crithidia fasciculata. The first 3 nt of Crithidia U1 snRNA were resistant to cleavage by RNases and alkali, indicating ribose methylation at the first two positions (47). We determined the methylation status of U1 snRNA in TbMTr1 RNAi lines by primer extension. The U1 snRNA extension pattern showed a majority species at the A2 band in noninduced cells, corresponding to position 1 modification (Fig. 3D). Additional faint bands that were unaffected by RNAi comigrated at positions 3 and 5. In the induced samples, an increase in the band migrating with A1 was apparent, demonstrating that the RT met with a lower level of impediment by methylation at position 1. The remaining cap 1 could be residual due to incomplete knockdown of TbMTr1, the high relative stability of U1 snRNA compared to the consumed SL RNA, or the presence of the dimethylated adenine base. Thus, TbMTr1 is also involved in the 2′-O-ribose methylation of U1 snRNA. As the U1 snRNA most likely acquires the TMG posttranscriptionally, TbMTr1 modification may precede TMG acquisition or recognize both substrate caps for methylation.

The SL RNA gene is transcribed as a 3′-extended form that is processed by exonucleases, including TbSNIP trimming at the end of its maturation (65). The accumulation of 3′-extended forms has been detected during inhibition of exportin 1 activity, in Sm protein studies, and for assorted SL mutants (35, 51, 65, 67). Hybridization analysis of RNA from Tet-induced RNAi cells 2 days postinduction and beyond revealed the accumulation of substrate SL with slower migration (Fig. 3E), characteristic of 3′-extended molecules. No 3′-trimming defects were observed for U1 snRNA or 5S rRNA.

Loss of modification at position 1 for both SL RNA and U1 snRNA in TbMTr1 RNAi lines is consistent with the in vitro enzymatic activity. Position 1 ribose modification does not appear to play an essential role in trans-splicing or translation since no detectable effect on growth was measured in induced cultures.

Additional cap 4 defects in the absence of cap 1 methylation.

Given the potential importance of cap 1 modifications, we confirmed the absence of a growth phenotype by making a TbMTr1-null mutant line. To knock out both alleles of TbMTr1, we introduced constructions for homologous recombination using the flanking UTRs.

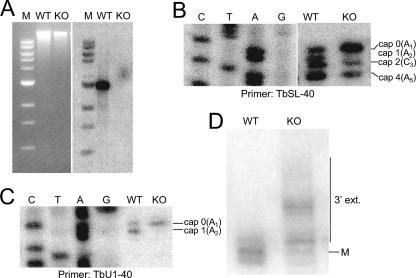

A Southern blot of wild-type and TbMTr1-null T. brucei lines was probed with the coding region of TbMTr1, confirming loss of both alleles (Fig. 4A). Primer extension was performed on total RNA. The loss of the band comigrating with A2 in TbMTr1-null cells was confirmed, as well as the rescue of the null phenotype by reintroduction of the recombinant TbMTr1-hemagglutinin gene (data not shown). The substrate SL phenotype was more pronounced in the null lines than in the induced RNAi lines, with a significant increase in the band comigrating with A1 indicating that the cap 0 form was the majority species. A decrease in the levels of C3 and A5 reflected lowered levels of the intermediate methylations at positions 2 and 4. The cap 0 extension product had a 48.1% presence in TbMTr1-null cells, compared to 19% in the wild type, implying that the kinetics of cap 4 formation as a whole was altered by the absence of cap 1.

FIG. 4.

Absence of TbMTr1 affects 5′ cap 1 and 3′ maturation. (A) Absence of TbMTr1 alleles. Shown is a Southern blot of wild-type (WT) and null (KO) clonal cell lines digested with XhoI. The products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel, visualized by ethidium bromide staining, transferred, and probed for the coding region of TbMTr1. Lane M is the 1-kb ladder (Invitrogen). (B) Altered substrate SL methylation in TbMTr1-null line. Primer extension analysis using total RNA collected from wild-type and clone 1 TbMTr1-null cell lines, as described for Fig. 3. (C) Altered cap methylation of the U1 snRNA measured by primer extension. (D) Cap 1-deficient SL RNA correlates with accumulation of 3′-extended forms. Total RNAs from samples collected from wild-type and TbMTr1-null cells were resolved through a 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea gel and probed with a γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide, TbSL-40, against the SL RNA intron. Mature SL RNA is denoted by “M”.

U1 snRNA had a complete loss of the band corresponding to cap 1 in TbMTr1-null cells (Fig. 4C). The U2 and U4 snRNAs, which also carry cap 1 methylations (47), showed no differences in the TbMTr1-null line by primer extension (data not shown). As our cap analysis is not complicated by downstream methylation in U1 snRNA, loss of the band at position 1 revealed that both base and ribose methylations were absent; this cannot be stated definitively for substrate SL.

The TbMTr1-null line was examined for substrate SL RNA length on a high-resolution RNA blot. In wild-type cells SL RNA was present in three main forms: a 141-nt species, the mature 142-nt molecule (20), and the 143-nt TbSNIP substrate, representing a 71:29 ratio of mature to underprocessed SL RNA. TbMTr1-null lines showed a decrease in mature 142-nt and accumulation of 144- to 150-nt forms, representing a 21:79 ratio of mature to underprocessed SL RNA (Fig. 4D). An increase in the 143-nt form indicated that the nuclear TbSNIP had not acted on the majority of SL RNA in TbMTr1-null cells.

Lack of methylation at position 1 of the SL cap correlates with reduced methylation of additional cap 4 nucleotides and removal of the 3′-extended poly(U) tail. The 3′-end processing delay supports a role of cap 1 methylation in the biogenesis of the SL RNA. Methylations downstream of ribose-deficient cap 1 nucleotide indicate that TbMTr2 and TbMTr3 activities are independent of modification(s) at the first position.

Absence of 2′-O-methylation at position 1 in TbMTr1-null mRNA.

TbMTr2 and TbMTr3 studies demonstrate that undermethylated SL is trans spliced. We examined the cap structure of mRNA from TbMTr1-null cells to assess the methylation pattern on these trans-spliced and translation-competent transcripts.

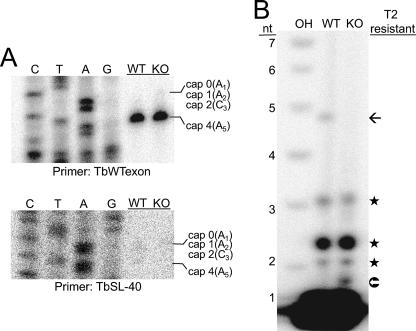

An oligonucleotide complementary to SL exon, TbWTexon, was used in primer extension reactions on poly(A)+ RNA (Fig. 5A). The extension on wild-type mRNA reflects SL where the majority has position 4 modifications, in contrast to cap 4 intermediates captured in substrate extensions. No difference was observed between the wild-type and TbMTr1-null lines, with identical profiles showing position 4-modified SL as the majority species (> 95%). As a control for free SL RNA contamination, the poly(A)+ RNA was assayed with TbSL40 intron probe, yielding no product. Next mRNA samples were subjected to RNase T2 digestion to confirm cap 1 undermethylation. RNase T2 is a nonspecific endonuclease that cannot cleave RNA when 2′-O-ribose methylated. An RNase T2-resistant fragment that migrated slightly faster than the corresponding 5-nt OH-degradation marker was obtained from wild-type mRNA (Fig. 5B, black arrow) representing the fully modified cap 4 (55). The cap 4, T2-resistant band was not observed in mRNA derived from TbMTr1-null cells, but rather a T2-resistant band migrating between the 1-nt and 2-nt markers was revealed (Fig. 5B, white arrow). The novel band may represent nucleotide A1 with N6 monomethylation or dimethylation; however, this assignment must be confirmed by additional analysis.

FIG. 5.

Spliced SL has position 4 methylation despite 2′-O-ribose methylation absence at position 1. (A) Spliced SL is methylated at position 4 in TbMTr1-null lines. The poly(A)+-selected mRNA isolated from wild-type (WT) and TbMTr1-null (KO) cells was extended using primer TbWTexon, complementary to the exon sequence, as described for Fig. 3. In the bottom panel poly(A)+-selected mRNA was extended with TbSL-40 as a negative control. (B) Absence of 2′-O-ribose methylation in spliced SL. Poly(A)+-selected RNA was treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase and HK phosphatase to remove the 5′-m7G cap and phosphates, γ-32P labeled by polynucleotide kinase, and digested with RNase T2. A ladder of alkali-treated RNA (OH) for the corresponding sequence serves as a size marker. Black stars indicate common bands due to the labeling procedure; the black arrow indicates the T2-resistant cap 4 band; the white arrow indicates the T2-resistant band unique to TbMTr1-null cells.

The mRNA in TbMTr1-null cells lacks a complete cap 4, consistent with the absence of ribose methylation at position 1. Subsequent activities in the cap 4 maturation pathway occur efficiently in the absence of TbMTr1 activity; however, kinetic delays are apparent in the substrate profile.

TbMTr1 localizes to the nucleus in T. brucei.

Cap 1 methylation is Sm complex independent for SL RNA (35, 51, 65). To investigate spatial and temporal aspects of cap 1 synthesis, we determined the subcellular localization of TbMTr1 and of the substrate SL in a TbMTr1-null line.

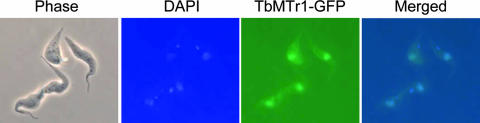

A TbMTr1-GFP fusion was created and introduced into the cognate genomic locus. Localization of the fusion protein coincided with the nuclear DAPI stain (Fig. 6), indicating that the majority of the protein was nucleoplasmic. Although GFP fusions can lead to mislocalization, especially when overexpressed, nuclear concentration is not the typical default. RNA-fluorescent in situ hybridization of TbMTr1-null cells for SL RNA revealed no cytosolic overaccumulation (data not shown), as had been seen in Sm protein knockdown experiments.

FIG. 6.

TbMTr1-GFP localizes to the nucleoplasm. Clonal YTAT cell lines were used to generate a line containing a GFP gene fused in frame with the TbMTr1 gene in its endogenous locus. The expressed TbMTr1-GFP fusion protein is visualized by light microscopy under UV light illumination. The positions of the nuclear and kinetoplast DNAs are revealed by staining with DAPI. The whole cells are shown by phase contrast.

The SL and TbMTr1 localizations support a delay in the processing kinetics for cap 1-deficient SL substrates. Nuclear SL retention has been induced by poisoning of the export pathway using leptomycin B, resulting in undermethylated and 3′-extended molecules (67). The phenotypic shift in the TbMTr1-null line indicates that the majority SL population is still undergoing biogenesis, while in wild-type cells approximately 79% of SL has completed the journey. Considering the virtual absence of 3′ mature substrate SL in the TbMTr1-null population shown in the high-resolution RNA analysis, the majority of the SL signal from the nucleoplasm is likely contributed by underprocessed forms, indicating a delay in nuclear egress.

DISCUSSION

We report the identification and characterization of the first eukaryotic cap 1 2′-O-ribose MTase that acts on SL RNA, and hence on mRNA, as well as on U1 snRNA from T. brucei. AdoMet-dependent methylation of an m7G-capped substrate was shown with recombinant TbMTr1 in vitro. Knockout of both TbMTr1 alleles resulted in viable cells with defects in ribose modification of the cap 1 position of SL RNA and U1 snRNA. TbMTr1-null cells displayed a delay in processing of SL RNA in which loss of 2′-O-ribose methylation at position 1 corresponded to a decrease in subsequent cap methylation and accumulation of 3′-extended forms.

The significance of mRNA cap 1 is evident from its maintenance in multiple viral systems, in which cap ribose methylation increases binding to ribosomes (37) and impacts translational control of viral transcripts (8). In influenza virus, priming of mRNA transcription is most efficient with stolen host caps that possess cap 1 (7). No function for snRNA cap 1 is known. The role of TbMTr1 in the processing of SL RNA does not exclude a synergistic role for cap 1 ribose methylation in translation. In viral cap 2′-O-ribose MTases and the cytosolic eIF4E translation initiation factor, recognition of the m7G cap occurs between two coplanar aromatic residues (44). The eIF4E proteins of the trans-splicing organisms Caenorhabditis elegans and Leishmania major can distinguish between different cap structures including base and ribose modifications (22, 63), reflecting a downstream discrimination of the effects of cap 1 enzymes such as TbMTr1.

TbMTr1 has retained the positional specificity of the related baculovirus MTase 1 capping enzyme, in contrast to the changes in positional specificity to cap 2 and cap 3 by TbMTr2 and TbMTr3, the kinetoplastid homologs of the vaccinia virus cap 1 MTase VP39 (21, 49). Horizontal gene transfer between viruses and eukaryotic cells may have given rise to these three genes, followed by altered enzyme specificity from the viral cap 1 modification in the protists. The TbMTr1 and its eukaryotic orthologs are likely to be derived from similar viral origins and have additional domains absent from the viral orthologs that may be important for their activity and specificity. All eukaryotic members of the TbMTr1 family contain N-terminal extensions of 40 to 200 aa that are predicted to be disordered. The homologs from metazoa contain additional C-terminal domains related to guanylyltransferases but lack catalytic residues (15).

Cap 4 formation in T. brucei is linear, with methylations starting from the 5′ end (34). Based on the nuclear localization of TbMTr1-GFP and the SL cap 1 phenotype on Sm complex-deficient transcripts (35, 51, 65), TbMTr1 acts independently of Sm protein binding and facilitates biogenesis of the SL RNA. TbMTr2 in vitro activity does not require prior cap 1 modification (19), consistent with in vivo results for both TbMTr2 and TbMTr3. Subsequent 5′-end processing may be enhanced by cap 1, reflecting a decrease in the ability of TbMTr2 and TbMTr3 to recognize the A1 ribose-methylation-deficient substrate or the inaccessibility of the substrate to these nucleus-localized enzymes, potentially due to inefficient trafficking of substrate SL RNA. The cap 1 base MTase(s) has yet to be identified, but the apparent absence of the dimethylation on U1 snRNA in TbMTr1-null cells suggests a requirement for TbMTr1 activity for additional modifications; the appearance of a novel band from mRNA RNase T2 digestions indicates that SL base modification may proceed without position 1 ribose methylation, but primer extension detection of the base intermediate is blocked by downstream methylations. Developed assays using two-dimensional TLC for cap analysis are dependent on isolation of an RNase T2-resistant fragment that is lost in the TbMTr1-null cells. Complete cap 4 was once thought to be required for trans-splicing of the SL onto mRNAs (32, 53, 56, 57). The knockout of TbMTr1 further underscores the independence of complete cap 4 formation and trans-splicing, as shown in exon mutagenesis studies (52, 68).

TbMTr1 is the first nonviral enzyme in this family to be defined as a cap 1 MTase. In humans the cap 1 mRNA 2′-O-ribose MTase activity has been partially purified and resides in the nucleus; subsequent cap 2 2′-O-ribose methylation occurs in the cytoplasm (30, 42). The appearance of cap ribose methylation on Xenopus laevis maternal transcripts correlates with translation initiation (25). Inhibition of ribose and internal adenosine N6-methylation in mammalian cells leads to decreased cytoplasmic half-life, suggestive of a role in trafficking or processing of mRNA transcripts (10). Interestingly, a TbMTr1 family member in Caenorhabditis elegans caused maternal sterility when targeted by RNAi (46).

At this point, the role of cap 4 in kinetoplastid biology remains an open question. As is the case in tRNA and rRNA, the effects of cap methylations may be cumulative and synergistic. Family-wide pathway conservation suggests a key, functionally selected role. Likewise the prevalence and diversity of higher-order cap structures in eukaryotes and viruses allude to a primary function that we have yet to appreciate fully.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jay Bangs for the pKO vectors; Thomas Seebeck for pMOT vectors; Kent Hill for YTAT cells and for use of the Zeiss fluorescence microscope; Murray Schnare for advice on cap analysis; and Miriam Giardini, Robert Hitchcock, Sean Thomas, and Scott Westenberger for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI034056 and in part by grants of the Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic 2B06129 and LC07032. J.R.Z. was supported by NSF Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation Award HRD-0115115:3 and USPHS National Research Service Award GM07104.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 July 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexandrov, A., I. Chernyakov, W. Gu, S. L. Hiley, T. R. Hughes, E. J. Grayhack, and E. M. Phizicky. 2006. Rapid tRNA decay can result from lack of nonessential modifications. Mol. Cell 21:87-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arhin, G. K., H. Li, E. Ullu, and C. Tschudi. 2006. A protein related to the vaccinia virus cap-specific methyltransferase VP39 is involved in cap 4 modification in Trypanosoma brucei. RNA 12:53-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arhin, G. K., E. Ullu, and C. Tschudi. 2006. 2′-O-Methylation of position 2 of the trypanosome spliced leader cap 4 is mediated by a 48kDa protein related to vaccinia virus VP39. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 147:137-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee, A. K. 1980. 5′-terminal cap structure in eucaryotic messenger ribonucleic acids. Microbiol. Rev. 44:175-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangs, J. D., P. F. Crain, T. Hashizume, J. A. McCloskey, and J. C. Boothroyd. 1992. Mass spectrometry of mRNA cap 4 from trypanosomatids reveals two novel nucleosides. J. Biol. Chem. 267:9805-9815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisaillon, M., and G. Lemay. 1997. Viral and cellular enzymes involved in synthesis of mRNA cap structure. Virology 236:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouloy, M., S. J. Plotch, and R. M. Krug. 1980. Both the 7-methyl and the 2′-O-methyl groups in the cap of mRNA strongly influence its ability to act as primer for influenza virus RNA transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:3952-3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brownlee, G. G., E. Fodor, D. C. Pritlove, K. G. Gould, and J. J. Dalluge. 1995. Solid phase synthesis of 5′-diphosphorylated oligoribonucleotides and their conversion to capped m7Gppp-oligoribonucleotides for use as primers for influenza A virus RNA polymerase in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:2641-2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bujnicki, J. M., and L. Rychlewski. 2001. Reassignment of specificities of two cap methyltransferase domains in the reovirus λ2 protein. Genome Biol. 2:0038.1-0038.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camper, S. A., R. J. Albers, J. K. Coward, and F. M. Rottman. 1984. Effect of undermethylation on mRNA cytoplasmic appearance and half-life. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:538-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman, T. M., G. Wang, and F. Huang. 2004. Superior 5′ homogeneity of RNA from ATP-initiated transcription under the T7 phi 2.5 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Decatur, W. A., and M. J. Fournier. 2003. RNA-guided nucleotide modification of ribosomal and other RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 278:695-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decatur, W. A., and M. J. Fournier. 2002. rRNA modifications and ribosome function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27:344-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djikeng, A., L. Ferreira, M. D'Angelo, P. Dolezal, T. Lamb, S. Murta, V. Triggs, S. Ulbert, A. Villarino, S. Renzi, E. Ullu, and C. Tschudi. 2001. Characterization of a candidate Trypanosoma brucei U1 small nuclear RNA gene. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 113:109-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feder, M., J. Pas, L. S. Wyrwicz, and J. M. Bujnicki. 2003. Molecular phylogenetics of the RrmJ/fibrillarin superfamily of ribose 2′-O-methyltransferases. Gene 302:129-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freistadt, M. S., G. A. M. Cross, and H. D. Robertson. 1988. Discontinuously synthesized mRNA from Trypanosoma brucei contains the highly methylated 5′ cap structure, m7GpppA*A*C(2′-O)mU*A. J. Biol. Chem. 263:15071-15075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuichi, Y., and A. J. Shatkin. 2000. Viral and cellular mRNA capping: past and prospects. Adv. Virus Res. 55:135-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillian-Daniel, D. L., N. K. Gray, J. Astrom, A. Barkoff, and M. Wickens. 1998. Modifications of the 5′ cap of mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation: independence from changes in poly(A) length and impact on translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:6152-6163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall, M. P., and C. K. Ho. 2006. Functional characterization of a 48 kDa Trypanosoma brucei cap 2 RNA methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:5594-5602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hitchcock, R. A., G. M. Zeiner, N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2004. The 3′-termini of small RNAs in Trypanosoma brucei. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodel, A. E., P. D. Gershon, X. Shi, S. M. Wang, and F. A. Quiocho. 1997. Specific protein recognition of an mRNA cap through its alkylated base. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:350-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jankowska-Anyszka, M., B. J. Lamphear, E. J. Aamodt, T. Harrington, E. Darzynkiewicz, R. Stolarski, and R. E. Rhoads. 1998. Multiple isoforms of eukaryotic protein synthesis initiation factor 4E in Caenorhabditis elegans can distinguish between mono- and trimethylated cap structures. J. Biol. Chem. 273:10538-10542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, P. J., J. M. Kooter, and P. Borst. 1987. Inactivation of transcription by UV irradiation of T. brucei provides evidence for a multicistronic transcription unit including a VSG gene. Cell 51:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones, D. T., W. R. Taylor, and J. M. Thornton. 1992. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8:275-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuge, H., and J. D. Richter. 1995. Cytoplasmic 3′ poly(A) addition induces 5′ cap ribose methylation: implications for translational control of maternal mRNA. EMBO J. 14:6301-6310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei. 2004. MEGA3: integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief. Bioinform. 5:150-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lafontaine, D. L. J., T. Preiss, and D. Tollervey. 1998. Yeast 18S rRNA dimethylase Dim1p: a quality control mechanism in ribosome synthesis? Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2360-2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb, J. R., V. Fu, E. Wirtz, and J. D. Bangs. 2001. Functional analysis of the trypanosomal AAA protein TbVCP with trans-dominant ATP hydrolysis mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21512-21520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane, B. 1998. Historical perspectives on RNA nucleoside modifications, p. 1-20. In H. Grosjean and R. Benne (ed.), Modification and editing of RNA. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 30.Langberg, S. R., and B. Moss. 1981. Post-transcriptional modifications of mRNA. Purification and characterization of cap I and cap II RNA (nucleoside-2′-)-methyltransferases from HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 256:10054-10060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lapeyre, B., and S. K. Purushothaman. 2004. Spb1p-directed formation of Gm2922 in the ribosome catalytic center occurs at a late processing stage. Mol. Cell 16:663-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, H., and C. Tschudi. 2005. Novel and essential subunits in the 300-kilodalton nuclear cap binding complex of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:2216-2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maden, B. E., M. E. Corbett, P. A. Heeney, K. Pugh, and P. M. Ajuh. 1995. Classical and novel approaches to the detection and localization of the numerous modified nucleotides in eukaryotic ribosomal RNA. Biochimie 77:22-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mair, G., E. Ullu, and C. Tschudi. 2000. Cotranscriptional cap 4 formation on the Trypanosoma brucei spliced leader RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 275:28994-28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandelboim, M., S. Barth, M. Biton, X.-H. Liang, and S. Michaeli. 2003. Silencing of Sm proteins in Trypanosoma brucei by RNAi captured a novel cytoplasmic intermediate in SL RNA biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:51469-51478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martínez-Calvillo, S., S. Yan, D. Nguyen, M. Fox, K. Stuart, and P. J. Myler. 2003. Transcription of Leishmania major Friedlin chromosome 1 initiates in both directions within a single region. Mol. Cell 11:1291-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muthukrishnan, S., M. Morgan, A. K. Banerjee, and A. J. Shatkin. 1976. Influence of 5′-terminal m7G and 2′-O-methylated residues on messenger ribonucleic acid binding to ribosomes. Biochemistry 15:5761-5768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oberholzer, M., S. Morand, S. Kunz, and T. Seebeck. 2006. A vector series for rapid PCR-mediated C-terminal in situ tagging of Trypanosoma brucei genes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 145:117-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palfi, Z., W. S. Lane, and A. Bindereif. 2002. Biochemical and functional characterization of the cis-splicesomal U1 small nuclear RNP from Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 121:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palfi, Z., B. Schimanski, A. Günzl, S. Lücke, and A. Bindereif. 2005. U1 small nuclear RNP from Trypanosoma brucei: a minimal U1 snRNA with unusual protein components. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:2493-2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perry, K. L., K. P. Watkins, and N. Agabian. 1987. Trypanosome mRNAs have unusual “cap 4” structures acquired by addition of a spliced leader. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8190-8194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perry, R. P., and D. E. Kelley. 1976. Kinetics of formation of 5′ terminal caps in mRNA. Cell 8:433-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pintard, L., F. Lecointe, J. M. Bujnicki, C. Bonnerot, H. Grosjean, and B. Lapeyre. 2002. Trm7p catalyses the formation of two 2′-O-methyltransferases in yeast tRNA anticodon loop. EMBO J. 21:1811-1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quiocho, F. A., G. Hu, and P. D. Gershon. 2000. Structural basis of mRNA recognition by proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10:78-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddy, R., R. Singh, and S. Shimba. 1992. Methylated cap structures in eukaryotic RNAs: structure, synthesis and functions. Pharmacol. Ther. 54:249-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rual, J. F., J. Ceron, J. Koreth, T. Hao, A. S. Nicot, T. Hirozane-Kishikawa, J. Vandenhaute, S. H. Orkin, D. E. Hill, S. van den Heuvel, and M. Vidal. 2004. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 14:2162-2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnare, M. N., and M. W. Gray. 1999. A candidate U1 small nuclear RNA for trypanosomatid protozoa. J. Biol. Chem. 274:23691-23694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shatkin, A. J., and J. L. Manley. 2000. The ends of the affair: capping and polyadenylation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:838-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi, X., P. Yao, T. Jose, and P. Gershon. 1996. Methyltransferase-specific domains within VP-39, a bifunctional protein that participates in the modification of both mRNA ends. RNA 2:88-101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shuman, S. 2002. What messenger RNA capping tells us about eukaryotic evolution. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:619-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sturm, N. R., and D. A. Campbell. 1999. The role of intron structures in trans-splicing and cap 4 formation for the Leishmania spliced leader RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 274:19361-19367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sturm, N. R., J. Fleischmann, and D. A. Campbell. 1998. Efficient trans-splicing of mutated spliced leader exons in Leishmania tarentolae. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18689-18692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tschudi, C., and E. Ullu. 2002. Unconventional rules of small nuclear RNA transcription and cap modification in trypanosomatids. Gene Expr. 10:3-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tycowski, K. T., Z. H. You, P. J. Graham, and J. A. Steitz. 1998. Modification of U6 spliceosomal RNA is guided by other small RNAs. Mol. Cell 2:629-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ullu, E., and C. Tschudi. 1995. Accurate modification of the trypanosome spliced leader cap structure in a homologous cell-free system. J. Biol. Chem. 270:20365-20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ullu, E., and C. Tschudi. 1991. Trans splicing in trypanosomes requires methylation of the 5′ end of the spliced leader RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:10074-10078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ullu, E., C. Tschudi, and A. Günzl. 1996. Trans-splicing in trypanosomatid protozoa, p. 115-133. In D. F. Smith and M. Parsons (ed.), Molecular biology of parasitic protozoa. IRL Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 58.Wang, P., Z. Palfi, C. Preusser, S. Lücke, W. S. Lane, C. Kambach, and A. Bindereif. 2006. Sm core variation in spliceosomal small nuclear ribonucleoproteins from Trypanosoma brucei. EMBO J. 25:4513-4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, Z., J. C. Morris, M. E. Drew, and P. T. Englund. 2000. Inhibition of Trypanosoma brucei gene expression by RNA interference using an integratable vector with opposing T7 promoters. J. Biol. Chem. 275:40174-40179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wickstead, B., K. Ersfeld, and K. Gull. 2002. Targeting of a tetracycline-inducible expression system to the transcriptionally silent minichromosomes of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 125:211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wirtz, E., S. Leal, C. Ochatt, and G. A. M. Cross. 1999. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knock-outs and dominant negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99:89-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu, X., and L. A. Guarino. 2003. Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus orf69 encodes an RNA cap (nucleoside-2′-O)-methyltransferase. J. Virol. 77:3430-3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoffe, Y., J. Zuberek, A. Lerer, M. Lewdorowicz, J. Stepinski, M. Altmann, E. Darzynkiewicz, and M. Shapira. 2006. Binding specificities and potential roles of isoforms of eukaryotic initiation factor eIF4E in Leishmania. Eukaryot. Cell 5:1969-1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zamudio, J. R., B. Mittra, G. M. Zeiner, M. Feder, J. M. Bujnicki, N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2006. Complete cap 4 formation is not required for viability in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 5:905-915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeiner, G. M., S. Foldynová, N. R. Sturm, J. Lukeš, and D. A. Campbell. 2004. SmD1 is required for spliced leader RNA biogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 3:241-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zeiner, G. M., R. A. Hitchcock, N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2004. 3′-end polishing of the kinetoplastid spliced leader RNA is performed by SNIP, a 3′→5′ exonuclease with a motley assortment of small RNA substrates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:10390-10396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeiner, G. M., N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2003. Exportin 1 mediates nuclear export of the kinetoplastid spliced leader RNA. Eukaryot. Cell 2:222-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeiner, G. M., N. R. Sturm, and D. A. Campbell. 2003. The Leishmania tarentolae spliced leader contains determinants for association with polysomes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38269-38275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.