The detoxification enzyme glyoxalase I from L. major has been crystallized. Preliminary molecular-replacement calculations indicate the presence of three glyoxalase I dimers in the asymmetric unit.

Keywords: glyoxalase I, leishmaniasis

Abstract

Glyoxalase I (GLO1) is a putative drug target for trypanosomatids, which are pathogenic protozoa that include the causative agents of leishmaniasis. Significant sequence and functional differences between Leishmania major and human GLO1 suggest that it may make a suitable template for rational inhibitor design. L. major GLO1 was crystallized in two forms: the first is extremely disordered and does not diffract, while the second, an orthorhombic form, produces diffraction to 2.0 Å. Molecular-replacement calculations indicate that there are three GLO1 dimers in the asymmetric unit, which take up a helical arrangement with their molecular dyads arranged approximately perpendicular to the c axis. Further analysis of these data are under way.

1. Introduction

Methylglyoxal is a product of either spontaneous degradation of triose phosphates or a side reaction of triphosphate isomerase and must be detoxified owing to its ability to react with DNA, RNA and proteins (Thornalley, 1998 ▶). The glyoxalase system performs this detoxification: glyoxalase I (lactoglutathione lyase; EC 4.4.1.5; GLO1) isomerizes the hemithioacetal adduct spontaneously formed between methylglyoxal and glutathione (GSH) to S-d-lactoyl-glutathione. Glyoxalase II then hydrolyses this thioester, releasing GSH and d-lactate (Thornalley, 1996 ▶).

GLO1 genes have been reported in animal, plant, yeast and bacterial species. Eukaryotic GLO1 enzymes are typically Zn2+-dependent homodimers consisting of two subunits each composed of two βαβββ motifs. In contrast, prokaryotic GLO1 enzymes are typically Ni2+-dependent dimers (Sukdeo et al., 2004 ▶) and the enzymes of the yeasts and plasmodia (malaria parasites) are gene-duplicated monomers that have the same relative size and structure as GLO1 dimeric enzymes (Iozef et al., 2003 ▶; Thornalley, 2003 ▶). Crystal structures are available for human (Cameron et al., 1997 ▶, 1999 ▶) and Escherichia coli GLO1 (He et al., 2000 ▶).

Trypanosomatids are pathogenic protozoa of the order Kinetoplastida (Fairlamb et al., 1985 ▶) that cause serious tropical diseases such as sleeping sickness and Chagas’ disease (Trypanosoma spp.) and visceral, cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (Leishmania spp.) (Irsch & Krauth-Siegel, 2004 ▶). Currently available treatments for these diseases produce severe side effects and the parasites are increasingly resistant, thus creating an urgent requirement for new and more effective treatments (Fairlamb, 2003 ▶).

In these organisms, GSH is replaced by trypanothione [N 1,N 8-bis(glutathionyl)spermidine or T(SH)2] in detoxification and redox control, and trypanosomatid GLO1 is T(SH)2-dependent rather than GSH-dependent (Vickers et al., 2004 ▶). Additionally, L. major GLO1 has been shown to be similar to the prokaryotic enzymes in that it is dimeric and Ni2+-dependent and more similar in sequence to E. coli GLO1 than the Zn2+-dependent human GLO1 (Vickers et al., 2004 ▶). These observations suggest that L. major GLO1 is sufficiently different from its human orthologue to be a target for structure-aided inhibitor design. Here, we report the crystallization, X-ray analysis and molecular replacement of L. major GLO1 and highlight some interesting features of the molecular packing within the crystal.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Crystallization and X-ray data collection

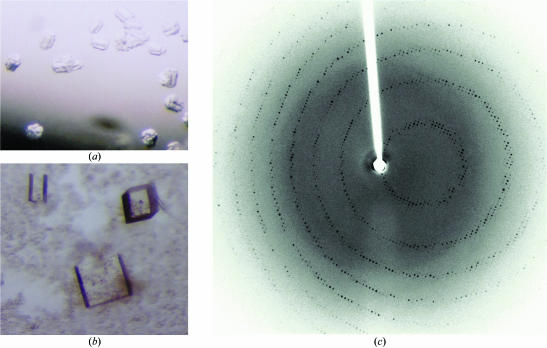

L. major GLO1 was expressed and purified using established protocols (Vickers et al., 2004 ▶), concentrated to 7.5 mg ml−1 and stored in 25 mM Bis-Tris–HCl pH 7.0 buffer with 50 mM NaCl. Initial crystallization screening was performed using commercially available crystal screens using the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method with 0.5 µl protein solution plus 0.5 µl reservoir solution in 96-well format Greiner plates equilibrated against 80 µl reservoir solution. Small crystals were obtained in condition B1 of the PEG/LiCl Screen and condition D6 of the MPD (2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol) Screen from Hampton Research (Laguna Niguel, CA, USA). Optimization of crystals from the first condition (rod-shaped clusters; Fig. 1 ▶ a) increased their size, but their morphology could not be improved and no diffraction was obtained. However, optimized crystals from the second condition (orthorhombic blocks; Fig. 1 ▶ b) diffracted to 2.8 Å on an in-house X-ray source (Fig. 1 ▶ c). Cuboidal crystals of maximum dimension 0.3 mm grew over two weeks at 291 K in hanging drops containing 3 µl protein solution plus 2 µl reservoir solution (62% MPD and 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0) suspended over 500 µl reservoir.

Figure 1.

(a) L. major GLO1 crystals with dimensions of approximately 0.15 × 0.10 × 0.10 mm. These crystals did not diffract. (b) Crystals with dimensions of approximately 0.30 × 0.30 × 0.20 mm. (c) The X-ray diffraction pattern obtained with a Rigaku Micromax-007 X-ray generator using 30 min exposure and 0.5° oscillation range.

Preliminary X-ray diffraction experiments were carried out using a Rigaku Micromax-007 X-ray generator (Cu Kα, λ = 1.54180 Å) equipped with an R-AXIS IV++ area detector and an X-Stream cryohead (Rigaku MSC). Crystals were flash-frozen directly from the drop, aided by the high concentration of the cryoprotectant MPD in the drops. Higher resolution X-ray data to 2.0 Å were collected at the ID14 EH2 station (λ = 0.93300 Å) at the European Synchrotron Research Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France).

2.2. Data processing and structure solution

Statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. In-house data were processed and scaled in space group P222 using DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). Subsequent analysis was carried out using the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶). The systematic absences indicated the correct space group to be P21212, with unit-cell parameters a = 129.85, b = 148.59, c = 50.58 Å. Synchrotron data were processed using MOSFLM (Leslie, 1992 ▶) and SCALA to produce a data set complete to 2.0 Å. The Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1974 ▶) (Table 2 ▶) indicates the most likely asymmetric unit content to be between four and eight molecules. The self-rotation function was calculated with POLARRFN using data between 10 and 4.25 Å resolution and an integration radius of 42 Å and revealed a number of peaks on the κ = 120° and κ = 180° sections. However, these features did not help in estimating the contents of the asymmetric unit.

Table 1. Data statistics.

| In-house data | Synchrotron data | |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21212 | P21212 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = 129.85, b = 148.59, c = 50.5 | a = 130.19, b = 148.96, c = 50.70 |

| Protein molecules per AU | 6 | 6 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40–2.8 (2.87–2.80) | 40–2.0 (2.08–2.00) |

| Measured reflections | 82150 | 283596 |

| Unique reflections | 24779 (2336) | 67613 (9728) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.2 (96.3) | 99.8 (99.5) |

| Redundancy | 3.2 (2.5) | 4.2 (4.0) |

| Rsym (%) | 0.056 (0.186) | 0.051 (0.298) |

| 〈I〉/〈σ(I)〉 | 17.26 (4.19) | 17.7 (4.9) |

Table 2. Matthews coefficient for orthorhombic L. major GLO1 crystals.

| Molecules per AU | VM (Å3 Da−1) | Solvent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.7 | 91.6 |

| 2 | 7.3 | 83.1 |

| 3 | 4.9 | 74.7 |

| 4 | 3.7 | 66.3 |

| 5 | 2.9 | 57.8 |

| 6 | 2.4 | 49.4 |

| 7 | 2.1 | 41.0 |

| 8 | 1.8 | 32.5 |

| 9 | 1.6 | 24.1 |

| 10 | 1.5 | 15.6 |

Molecular-replacement calculations were carried out on the in-house data with MOLREP using dimers of the apo and Ni2+ forms of E. coli GLO1 (PDB code http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/cgi/explore.cgi?pdbId=1fa8 and http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/cgi/explore.cgi?pdbId=1f9z, respectively; He et al., 2000 ▶) as search models. The searches were conducted for two, three and four dimers using the program’s default parameters with a maximum resolution of 4.0 Å and a search radius of 24.0 Å. The highest correlation coefficient was obtained by placing three dimers of http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/cgi/explore.cgi?pdbId=1fa8 in which residues 85–107 were mutated to alanine and residues 128–135 were deleted (because of the low sequence similarity in these sections to the L. major amino-acid sequence). The electron-density map resulting from rigid-body refinement with REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▶) contained protein-density features not present in the search model. RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2002 ▶) was used to perform prime-and-switch density modification including sixfold non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging. This further improved the map and allowed the proper assignment of side chains and missing residues. The residues of the molecular-replacement model were mutated to the correct sequence for L. major GLO1 using COOT (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶). At this point, the synchrotron data became available. The best model from the in-house data was refined as a rigid body against this new data and refinement, functional analysis and comparison with the human enzyme are under way.

LSQMAN (Kleywegt & Jones, 1994 ▶) was used to calculate rotation matrices and translation vectors that rotate molecules in the asymmetric unit onto each other. Vectors describing the rotation axes between molecules were calculated using DYNDOM (Hayward & Berendsen, 1998 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

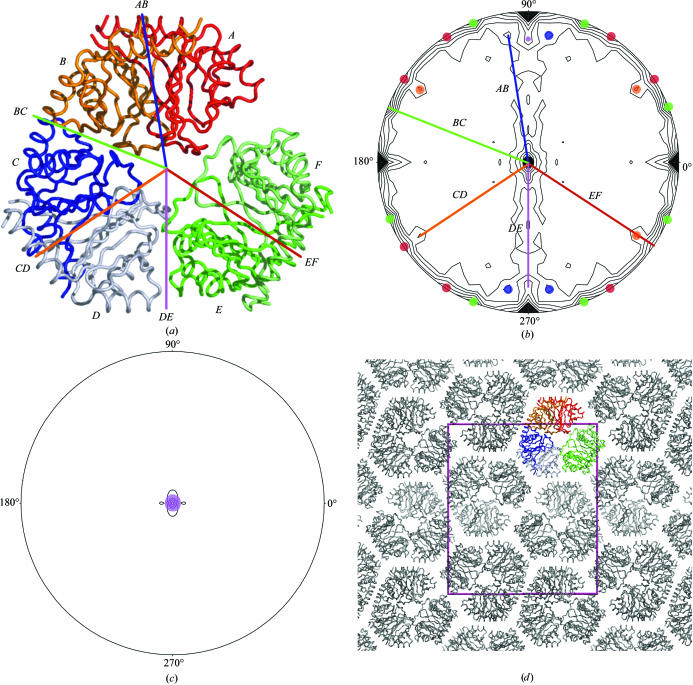

The packing of three dimers in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 2 ▶) results in a number of non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) twofold rotation axes which can be identified in the κ = 180° section of a self-rotation function (Figs. 2 ▶ a and 2 ▶ b). Twofold axes relate the monomers within each of the three dimers (A onto B, C onto D and E onto F). The arrangement of the dimers in the asymmetric unit creates two additional twofold axes relating neighbouring dimers to each other (AB onto DC and CD onto FE). The existence of peaks at (ω, ϕ) = (90, 22°), (90, 33°), (83, 34°), (81, 81°) and (79, 90°) agrees with the position of the twofold NCS axes found in the asymmetric unit. Two of these axes (BC and EF) run perpendicular to crystallographic twofold axes, resulting in additional NCS twofold axes running perpendicular to both the NCS and crystallographic axes. Interestingly, a peak at (0, 0°) on the κ = 120° section points towards the presence of a threefold NCS axis. Although there is no rotational threefold symmetry in this structure, close inspection shows that the angles which relate each dimer onto the neighbouring dimer are close to 120° (e.g. κ = 126°, the result of rotating axis AB onto CD, κ = 114°, BC onto DE, or κ = 113°, CD onto EF). These pseudo-threefold NCS axes result in peaks large enough to span several κ sections and therefore show up on the κ = 120° section (Fig. 2 ▶ d).

Figure 2.

(a) Cα trace of the asymmetric unit. GLO1 molecules are indicated by single letters, while NCS vectors are indicated by two letters. (b) κ = 180° section of the self-rotation function showing NCS vectors. All the vectors represent twofold NCS axes and only one line per NCS vector has been drawn to show how they relate to the molecular packing. All the symmetry-related peaks of each vector are represented by dots of the same colour. (c) κ = 120° section of the self-rotation function, showing a pseudo-threefold NCS vector. (d) Molecular packing of GLO1, showing the unit cell projected along the c axis.

The repetitive symmetric arrangement of dimers (where the AB–CD interaction is repeated in CD–EF) in our structure begs the question whether it could in principle form larger oligomers. In the specific arrangement we observe that this is not possible, as modelling additional dimers (‘GH’) results in a steric clash with dimer AB. There is no experimental evidence that L. major GLO1 forms assemblies any larger than a dimer in solution at typical concentrations. However, it is possible that at high concentrations, such as those achieved in supersaturated crystallization conditions, filamentous structures are formed. This might explain why our initial crystals, which look like clusters of rods, could not be optimized to produce diffraction. The preliminary results described here represent an excellent starting point for structure-based inhibitor design. It is hoped that comparisons with human GLO1 will lead to new opportunities in the chemotherapy of important third-world diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wellcome Trust (AHF, TV and NG) and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (AA and CSB) for funding.

References

- Cameron, A. D., Olin, B., Ridderstrom, M., Mannervik, B. & Jones, T. A. (1997). EMBO J.16, 3386–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. D., Ridderstrom, M., Olin, B., Kavarana, M. J., Creighton, D. J. & Mannervik, B. (1999). Biochemistry, 38, 13480–13490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763. [Google Scholar]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlamb, A. H. (2003). Trends Parasitol.19, 488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairlamb, A. H., Blackburn, P., Ulrich, P., Chait, B. T. & Cerami, A. (1985). Science, 227, 1485–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, S. & Berendsen, H. J. (1998). Proteins, 30, 144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, M. M., Clugston, S. L., Honek, J. F. & Matthews, B. W. (2000). Biochemistry, 39, 8719–8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozef, R., Rahlfs, S., Chang, T., Schirmer, H. & Becker, K. (2003). FEBS Lett.554, 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irsch, T. & Krauth-Siegel, R. L. (2004). J. Biol. Chem.279, 22209–22217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt, G. J. & Jones, T. A. (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, A. (1992). Jnt CCP4/ESF–EACBM Newsl. Protein Crystallogr.26

- Matthews, B. W. (1974). J. Mol. Biol.82, 513–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sukdeo, N., Clugston, S. L., Daub, E. & Honek, J. F. (2004). Biochem. J.384, 111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger, T. C. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 2082–2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornalley, P. J. (1996). Gen. Pharmacol.27, 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornalley, P. J. (1998). Chem. Biol. Interact.111–112, 137–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornalley, P. J. (2003). Biochem. Soc. Trans.31, 1343–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, T. J., Greig, N. & Fairlamb, A. H. (2004). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 101, 13186–13191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]