Abstract

Despite extensive evidence that integrin conformational changes between bent and extended conformations regulate affinity for ligands, an alternative hypothesis has been proposed in which a “deadbolt” can regulate affinity for ligand in the absence of extension. Here, we tested both the deadbolt and the extension models. According to the deadbolt model, a hairpin loop in the β3 tail domain could act as a deadbolt to restrain the displacement of the β3 I domain β6-α7 loop and maintain integrin in the low affinity state. We found that mutating or deleting the β3 tail domain loop has no effect on ligand binding by either αIIbβ3 or αVβ3 integrins. In contrast, we found that mutations that lock integrins in the bent conformation with disulfide bonds resist inside-out activation induced by cytoplasmic domain mutation. Furthermore, we demonstrated that extension is required for accessibility to fibronectin but not smaller fragments. The data demonstrate that integrin extension is required for ligand binding during integrin inside-out signaling and that the deadbolt does not regulate integrin activation.

Integrins are cell adhesion molecules that transmit bidirectional signals across the plasma membrane and regulate many biological functions, including cell differentiation, cell migration, and wound healing (1, 2). A bent conformation observed by x-ray crystallography (3) and electron microscopy (4, 5) represents the physiological low affinity state. Integrin activation is regulated by binding of intracellular proteins such as talin to the integrin β-subunit cytoplasmic tail (6), leading to separation between the α- and β-subunits at their transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (7–9) and propagation of conformational changes from the transmembrane domains to the ligand binding headpiece, which increases integrin affinity for ligand (10, 11). These long range conformational changes involve integrin extension. Conversely, ligand binding also induces integrin extension, which leads to the separation of the α- and β-subunit legs and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions (11).

Recent co-crystal structures of integrin αIIbβ3 headpiece bound to ligands revealed the molecular basis for the large conformational changes that accompany ligand binding (12). The conformational changes in the ligand binding site that increase affinity for ligand are allosterically linked by a crankshaft-like α7-helix displacement in the β3 I domain to a 60° change in the angle between the β3 I and hybrid domains and to a 70 Å increase in separation between the α- and β-subunits at their knees. Since the hybrid domain and connecting β-leg domains are central in the interface between the integrin headpiece and legs in the bent conformation, integrin extension enables hybrid domain swing-out. The crystal structures are in excellent agreement with studies using electron microscopy (4, 5, 13, 14), NMR (15), small angle x-ray scattering (16), and mutational studies and mapping of the epitopes of allosteric activating and inhibiting antibodies (17–20), which all support the switchblade model for integrin activation, in which integrin extension and leg separation are coupled with swing-out of the hybrid domain and the displacement of the β-I domain α7 helix.

Two effects of extension are important for integrin activation. First, extension places the ligand binding site 150–200 Å further above the cell surface and orients it pointing away from, rather than toward, the surface of the cell on which it expressed. This favors accessibility to ligands on other cells and in the extracellular matrix. Second, extension enables hybrid domain swing-out and conversion of the headpiece from the closed, low affinity to the open high affinity state (11).

There is controversy about the requirement of extension for integrin activation. An electron microscopy (EM)2 study reported that soluble αVβ3 bound to a fibronectin fragment was still in the bent conformation (21). As a supplement or alternative to integrin extension, regulation of integrin affinity by a “deadbolt” has been proposed. This proposal is based on the observation of an interaction at a small 60 Å2 interface between the β-tail domain CD loop (the deadbolt) and the β-I domain β6 strand-α7 helix region in the unliganded αVβ3 crystal structure (22). It was hypothesized that 1) this interaction restricts the displacement of the β-I domain β6-α7 loop and thus keeps the integrin in the low affinity state and 2) that loss of this interaction would induce inside-out activation without extension. Here, we directly tested the deadbolt model by mutating or deleting the β-tail domain CD loop and show that these mutations have no effect on ligand binding by αIIbβ3 or αVβ3 integrins. We further demonstrate that integrins locked in the bent conformation are resistant to inside-out activation and that extension is important to promote accessibility of cell surface integrins for soluble ligands.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmid Construction, Transient Transfection, and Immunoprecipitation

Plasmids coding for full-length human αIIb or αV and β3 were subcloned into pEF/V5-HisA and pcDNA3.1/Myc-His (+), respectively (4). Cysteine substitutions (G307C in αV and R563C in β3) and the N305T mutant of β3 were described previously (4, 23). Other mutants were made using site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Constructs were transfected into 293T cells using FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Transfected cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]cysteine/methionine (PerkinElmer Life Science) and immunoprecipitated with the conformation-independent β3 mAb AP3, which recognizes residues in the plexin-semaphorin-integrin (PSI) and hybrid domains (24–26) as described (7).

Soluble Ligand Binding

The fragments of human fibronectin (Fn) type III domains 7–10 (Fn7–10) and 9–10 (Fn9–10) were prepared as described previously (27). The purified fragments were labeled by Alexa Fluor 488 using Alexa Fluor 488 protein labeling kit A10235 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Binding of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled human fibrinogen (Fg) (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN), FITC-labeled human Fn (Sigma), and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Fn7–10 and Fn9–10 and PAC-1 IgM, which recognizes activated αIIbβ3 at its ligand binding site (28, 29) (BD Biosciences), was determined as described (23). Briefly, transfected cells suspended in 20 mM HEPES-buffered saline (pH 7.4) supplemented with 5.5 mM glucose and 1% bovine serum albumin were incubated with 50 μg/ml fluorescently labeled ligands or 10 μg/ml PAC-1 in the presence of 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+, 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mn2+, 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mn2+, plus either 10 μg/ml activating mAb PT25-2 to the αIIbβ-propeller domain (29, 30) or 10 μg/ml activating mAb LIBS1 to the β3 leg domain (31) at room temperature for 30 min and then stained with Cy3-labeled anti-β3 mAb AP3 on ice for 30 min. For PAC-1 binding, cells were washed and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgM and Cy3-labeled AP3 on ice for another 30 min before being subjected to flow cytometry. Binding activity is presented as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgM or ligands, after subtraction of background MFI in EDTA, expressed as a percentage of the MFI of the Cy3-AP3.

LIBS Epitope Expression

Anti-LIBS mAb LIBS1 and D3 to the β3 leg domain (31) were kindly provided by Drs. M. H. Ginsberg (University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA) (32) and L. K. Jennings (University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN) (33). LIBS epitope expression was determined as described previously (23). In brief, transfected cells suspended in HEPES-buffered saline supplemented with 5.5 mM glucose and 1% bovine serum albumin were incubated with or without 25 μM cyclo-(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Val) (cyclo-RGDfV) (Bachem Bioscience, Inc., King of Prussia, PA) peptide or 1 mg/ml Fn7–10 in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+ or 0.2 mM Ca2+/0.2 mM Mn2+ at room temperature for 30 min and then with anti-LIBS mAb on ice for 30 min followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and flow cytometry. LIBS antibody binding is presented as the MFI of anti-LIBS antibody staining as a percentage of the MFI of conformation-independent mAb AP3 staining.

Establishment of CHO Stable Cells

The QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) was used to introduce a 15-nucleotide deletion into human integrin β3 cDNA to generate cDNA encoding ΔAsp-672–Lys-676. CHO cells were transfected with human integrin αIIb (in pcDNA3.1 Zeo; Invitrogen) and one of two forms of human integrin β3 (wild type or ΔAsp-672–Lys-676 in pcDNA3.1 Neo; Invitrogen) using a calcium phosphate transfection kit (Invitrogen). 48 h after transfection, the growth medium (F12K; Mediatech, Inc, Herndon, VA) was supplemented with 0.6 mg/ml G418 and 0.35 mg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen).

Evaluation of αIIbβ3 Activation State on CHO Cells

CHO cells that had been stably transfected with cDNAs encoding human αIIb and either human β3 or human β3_Δ672–676 were incubated with 5 μg/ml anti-integrin β3 monoclonal antibody, AP3, conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen) and either 120 μg/ml FITC-fibrinogen or 2.5 μg/ml PAC-1 (BD Biosciences) in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+ or 1 mM Mn2+. Purified fibrinogen was kindly provided by Dr. Michael Mosesson (Blood Research Institute, BloodCenter of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI) and was labeled with FITC according to previously described methods (34).

Results

Deleting or Mutating Residues of the β-Tail Domain CD Loop Has No Effect on Ligand Binding

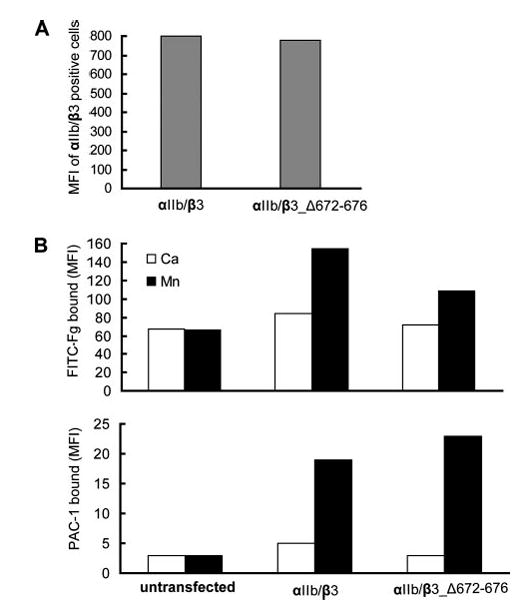

According to the deadbolt model, a hairpin loop (between β-strands C and D) of the β3 tail domain (the CD loop) contacts the β3 I domain and restrains integrin activation (Fig. 1). Two groups of investigators independently tested the deadbolt model and have combined their data in this paper. One group produced and assayed ligand binding to CHO cell lines stably expressing either wild-type or mutant αIIbβ3 with five residues (Asp-672–Lys-676) deleted from the β-tail CD loop. The activation state of these integrins was evaluated by measuring the ability of CHO cell transfectants to bind macromolecular ligands. Wild-type and mutant αIIbβ3 were expressed similarly in CHO cells (Fig. 2A). Basal binding of fibrinogen and the ligand-mimetic, activation-dependent antibody PAC-1 (28, 29) in the presence of Ca2+ was low for both wild-type αIIbβ3 and the αIIbβ3_Δ672–676 mutant (Fig. 2B), i.e. it was similar to that in mock transfectants. In contrast, Mn2+ induced similar binding of fibrinogen and PAC-1 mAb to the wild-type and αIIbβ3_Δ672–676 CHO cell transfectants (Fig. 2B). These data show that deletion of the deadbolt does not constitutively activate αIIbβ3 integrin.

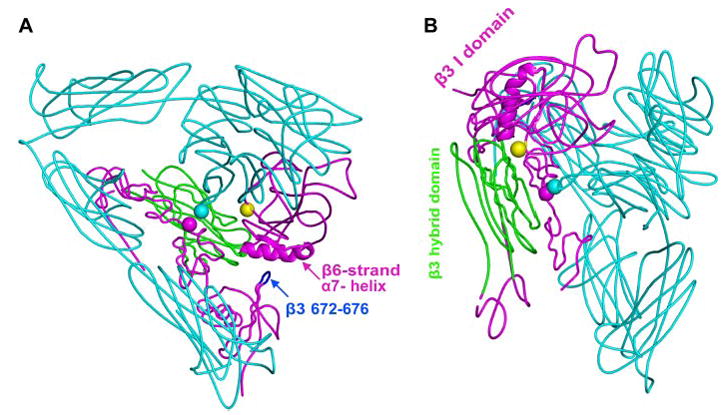

FIGURE 1. Locations of the mutations in the αVβ 3 crystal structure (3).

The αV subunit is in cyan. The β3 hybrid domain is in green, and other β3 domains are in magenta. The β3 tail domain CD loop (residues Asp-672–Lys-676) is in blue. Residues mutated to cysteine are shown with spheres at the positions of αV G307 Cα (cyan) and β3 R563 Cα (magenta). The position of the N-glycan wedge introduced by the β3 NIN305T mutation is shown with a yellow sphere at Asn-303 Cα. A, this view emphasizes the β-I domain β6-strand and α7-helix, the only elements shown as a ribbon, and their proximity to the β-tail domain CD loop. B, this view is rotated relative to A and emphasizes the glycan wedge introduced into a crevice between the hybrid and β-I domain that widens in the open headpiece conformation.

FIGURE 2. Effect of β-tail domain CD loop mutation on ligand binding by αIIbβ3 expressed on CHO cells.

A, expression of wild-type and mutant αIIb/β3 integrins in CHO cells is shown as MFI of αIIb/β3-positive cells stained with AP3-conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647. B, mock transfectants or αIIb/β3-positive cells gated for equivalent β3 expression using AP3 mAb were quantitated for binding of FITC-Fg or the fibrinogen mimetic antibody, PAC-1, in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+ or 1 mM Mn2+.

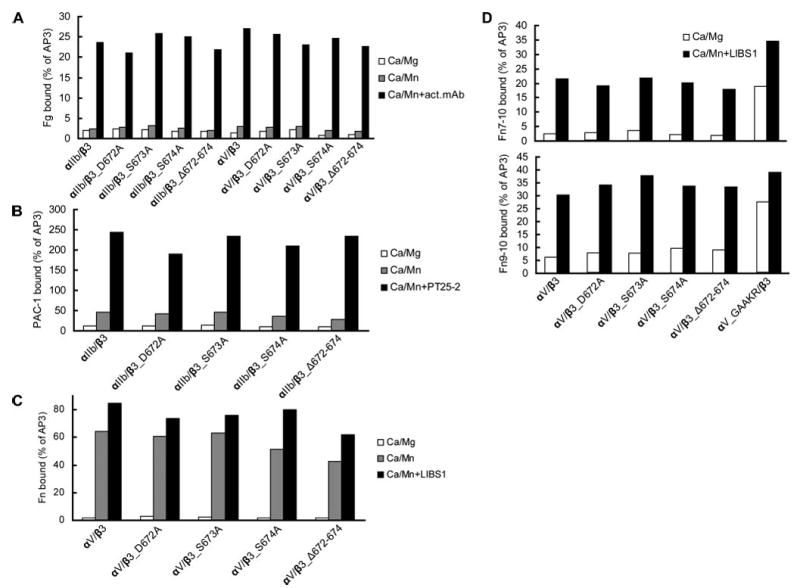

The other group deleted three residues (Aps-672–Ser-674) of the CD loop or mutated them to Ala individually. These mutations had no effect on the expression of αIIbβ3 or αVβ3 on the cell surface (data not shown). The activation state of these mutant integrins was evaluated by measuring soluble ligand binding to 293T cells transiently transfected with the mutant or wild type receptors (Fig. 3). None of the CD loop mutants showed constitutively high affinity for human fibrinogen, fibronectin, or the ligand mimetic antibody PAC-1 under physiological conditions (Fig. 3, A–C). Furthermore, CD loop mutants all were activated by Mn2+ and activating mAbs to the same level as wild-type integrins. In addition, CD loop mutations had no effect on the binding of fibronectin fragments Fn7–10 or Fn9–10 (Fig. 3D). As a positive control, the cytoplasmic GFFKR to GAAKR mutation (αV_GAAKR), which mimics inside out activation (7), constitutively activated binding of the fibronectin fragments (Fig. 3D). These data demonstrate that the β-tail domain CD loop does not restrain activation of either integrin αIIbβ3 or αVβ3.

FIGURE 3. Effect of β-tail domain CD loop mutation on ligand binding by αIIbβ3 and αVβ3 expressed in 293T cells.

A, human Fg binding to αIIbβ3 and αVβ3. B, ligand-mimetic PAC-1 antibody binding to αIIbβ3. C, human Fn binding to αVβ3. D, binding of fibronectin fragments Fn9–10 and Fn7–10 to αVβ3. 293T cell transfectants were treated with the indicated conditions and incubated with 50 μg/ml fluorescently labeled ligands or 10 μg/ml PAC-1 IgM as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Binding is expressed as MFI of ligand staining as a percentage of MFI of Cy3-AP3 antibody staining.

Integrins Locked in the Bent Conformation Are Resistant to Inside-out Activation

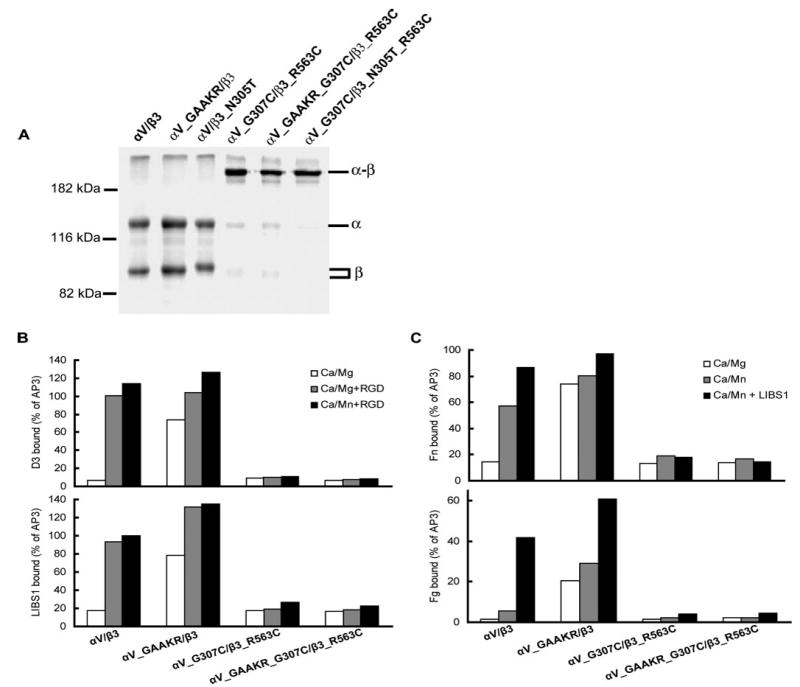

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer and mutagenesis studies revealed that integrin inside-out activation requires unclasping or separation of the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains (7, 8, 35, 36). However, it has been questioned whether integrin extension is required for inside-out activation (37). Previously, we showed that introducing a disulfide bond between residues 307 of the αV β-propeller domain and 563 of the β3 I-EGF domain 4, with the αV G307C and β3 R563C mutations, locked the αVβ3 integrin in the low affinity, bent conformation (4). Residues αV-307 and β3-563 are in close proximity in the bent αVβ3 conformation (3) (Fig. 1). To test the requirement for integrin extension during inside-out activation, we combined the disulfide bond-forming αV G307C and β3 R563C mutations with the αV_GFFKR/GAAKR cytoplasmic domain mutation, which induces inside-out activation. The disulfide bond was formed in high efficiency in this αV_GAAKR_G307C/β3_R563 mutant (Fig. 4A). Consistent with previous results (7), the GAAKR mutant (αV_GAAKR/β3) bound anti-LIBS antibodies D3 and LIBS1 to the β3 leg (31) constitutively, indicating that the integrin was extended (Fig. 4B). However, binding of LIBS antibodies by αV_GAAKR/β3 was reversed when the intersubunit disulfide bond was introduced in the αV_GAAKR_G307C/β3_R563C mutant (Fig. 4B). The high affinity (IC50 = 2.5 nM) (38) cyclo-RGDfV peptide induced LIBS binding by wild-type αVβ3 and further enhanced LIBS binding by αV_GAAKR/β3 (Fig. 4B). By contrast, the mutants αV_GAAKR_G307C/β3_R563C and αV_G307C/β3_R563C did not bind LIBS antibodies even in the presence of cyclo-RGDfV (Fig. 4B), showing that these mutants were locked in the bent conformation. Ligand binding assays showed that mutant integrin αV_GAAKR/β3 bound fibrinogen and fibronectin constitutively in Ca2+/Mg2+ (Fig. 4C). By contrast, the mutants αV_GAAKR_G307C/β3_R563C and αV_G307C/β3_R563C did not bind fibrinogen and fibronectin even in the presence of Mn2+ and activating mAb (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that integrins locked in the bent conformation are resistant to inside-out activation, i.e. integrin extension is required for inside-out activation as measured by both LIBS epitope exposure and soluble ligand binding.

FIGURE 4. Intersubunit disulfide bond formation and effect on LIBS exposure and ligand binding.

A, disulfide bond formation by cysteine mutants. Lysates from 35S-labeled 293T cells that had been transiently transfected with wild-type or mutant integrins as indicated were immunoprecipitated with mAb AP3 (anti-β3) and subjected to non-reducing SDS-7.5% PAGE. Bands of αV (α), β3 (β), and αVβ3 heterodimer (α-β) are indicated. Positions of protein molecular size markers are shown on the left. B, LIBS exposure. 293T cell transfectants were stained with anti-LIBS mAb D3 or LIBS1 in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+ or 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mn2+, with or without 25 μM cyclo-RGDfV (RGD). LIBS epitope expression is expressed as MFI of the D3 or LIBS1 staining as a percentage of MFI of AP3 mAb staining. C, soluble Fn or Fg binding to 293T cell transfectants in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+ or 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mn2+ or 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mn2+ plus 10 μg/ml activating mAb, LIBS1. Binding is expressed as MFI of ligand staining as a percentage of MFI of staining with Cy3-AP3 antibody.

Ligand Accessibility Is Important for Integrin Ligand Binding

A negative stain EM study suggested that the soluble integrin αVβ3 in the bent conformation could bind a fragment of its ligand, fibronectin (21). These data lead to the suggestion that integrin extension may not be required for ligand binding. We designed experiments to investigate whether bent integrins are accessible to ligands on the cell surface. Introduction of a glycan wedge into the hybrid domain at its interface with the β-I domain by introducing an NIT305 sequon with the β3_N305T mutation has been shown to stabilize integrins in the high affinity state by favoring swing-out of the hybrid domain (Fig. 1) (23). We combined the αV_G307C/β3_R563C mutations that form the intersubunit disulfide bond with the glycan wedge mutation. The disulfide bond was formed with high efficiency in this αV_G307C/β3_N305T_R563C mutant (Fig. 4A). For wild-type αVβ3 integrin, LIBS epitope exposure was partially induced by Mn2+ treatment and fully induced by cyclo-RGDfV peptide or Fn7–10 in the presence of Mn2+ (Fig. 5A). The wedge mutant (αV/β3_N305T) bound LIBS antibodies constitutively, irrespective of the conditions used. By contrast, the αV_G307C/β3_N305T_R563C and αV_G307C/β3_R563C mutants did not bind LIBS antibodies even in the presence of cyclo-RGDfV peptides or Fn7–10 (Fig. 5A), showing that these mutant integrins were locked in the bent conformation. In contrast to wild-type αVβ3, the disulfide-bonded wedge mutant αV_G307C/β3_N305T_R563C did not bind full-length human fibronectin, even when activated (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5. LIBS exposure and ligand binding of disulfide-bonded and glycan wedge mutants.

A, LIBS exposure. 293T cell transfectants were stained with anti-LIBS antibodies, D3 or LIBS1, in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+ or 0.2 mM Ca2+/0.2 mM Mn2+, with or without 25 μM cyclo-RGDfV or 1 mg/ml Fn7–10. LIBS epitope expression is expressed as MFI of the D3 or LIBS1 staining as a percentage of MFI of AP3 mAb staining. B, Fn binding. C, fibronectin fragment Fn7–10 binding. D, fibronectin fragment Fn9–10 binding. In B–D, 293T cell transfectants were stained with 50 μg/ml fluorescently labeled ligands in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mg2+ or 1 mM Ca2+/1 mM Mn2+ plus 10 μg/ml activating mAb, LIBS1, and subjected to flow cytometry. Binding is expressed as MFI of ligand staining as a percentage of MFI of Cy3-AP3 antibody staining.

Distinctive results were obtained with small fibronectin fragments. The disulfide-bonded wedge mutant αV_G307C/β3_N305T_R563C bound the Fn7–10 and Fn9–10 fragments constitutively (Fig. 5, C and D). However, the amount of binding was lesser than that for the other mutants and wild-type αVβ3 (Fig. 5, C and D). Consistent with previous results, the disulfide-bonded mutant αV_G307C/β3_R563C did not bind fibronectin, Fn7–10, and Fn9–10, even in activating conditions. As controls, the wedge mutant (αV/β3_N305T) or the wedge mutation combined with single cysteine mutations (αV_G307C/β3_N305T and αV/β3_N305T_R563C) bound fibronectin and the Fn7–10 or Fn9–10 fragments constitutively (Fig. 5, B–D). These data demonstrate that even when activated, integrins in the bent conformation are not accessible to large soluble ligands, although they are accessible to small soluble ligand fragments.

Fn Fragments Induce Extension of Cell Surface αVβ3

As mentioned above, a negative stain EM study reported that soluble αVβ3 remained in the bent conformation when exposed to 1 mg/ml Fn fragment in 0.2 mM Ca2+/0.2 mM Mn2+ (21). Notably, under the same conditions, we found that Fn 7–10 efficiently induced extension of cell surface αVβ3, as reported both by the LIBS1 and D3 antibodies (Fig. 5 A).

Discussion

In the αVβ3 structure (3), residue Ser-674 at the tip of the CD loop of the β-tail domain contacts the β-I domain. The buried surface area is quite small at 60 Å2. According to the deadbolt model, the residues at the tip of the CD loop, by contacting the β6-strand near the β6-α7 loop of the β-I domain, restrain the integrin in the resting, low affinity state (22, 37). Activating mutations in the β6-α7 loop of the β2 I domain (39) have been interpreted as supporting the deadbolt model (37). However, rearrangement of this region is directly coupled to rearrangement of the ligand binding site and thus to the affinity change (12). Introduction of disulfide bonds (40) or other mutations (41, 42) into the β6-α7 loop and α7-helix induced high affinity by causing the rearrangement of the ligand binding site of the β-I domain, and there is no evidence that these mutations disrupt interaction with the β-tail domain CD loop. Therefore, mutation of the β-tail domain CD loop is required to test the deadbolt model. This model was independently tested using different mutations and cell lines in two different laboratories, with similar results. We found that mutations to Ala of three residues in this loop, or deletions of residues 672–674 or 672–676, did not activate ligand binding by integrins αVβ3 or αIIbβ3 and had no effect on the ability of these integrins to be activated by Mn2+ or antibodies. If local rearrangement of the β3 tail domain were sufficient for integrin affinity regulation, as proposed in the deadbolt model, we should at least detect the binding of small fibronectin fragments to CD loop mutants. However, we found that the CD loop mutations had no effect on the binding of the Fn7–10 and Fn9–10 fragments. Therefore, we conclude that the β-tail domain CD loop does not regulate ligand binding and does not act as a deadbolt. Recently, it was reported that exchanging D658GMD in the β-tail domain CD loop of the β2 subunit with D672SSG of the β3 subunit or with N658GTD, which introduces a glycan wedge sequence, activated the αMβ2 integrin (43). A crystal structure of αMβ2 is not available. Whether the β-tail domain CD loop of αMβ2 contacts the β-I domain is unknown, and the overall orientation of the β-tail domain relative to the β-I domain in β2 integrins is unknown, making the structural consequences of mutations in the CD loop difficult to predict. However, it is known that multiple substitutions in the β2 subunit, including those in I-EGF domain 3, are activating, consistent with disruption of interactions in the bent conformation (15, 44). Integrin activation is observed after many types of mutations. We believe that our finding of a lack of effect of deletion or mutation of the β-tail domain CD loop, in the context of the structurally characterized αVβ3 integrin, which served as the basis for the deadbolt proposal, is the more telling test of this model.

Our data further demonstrate that transition from the bent to extended conformation (i.e. integrin extension) is not only required for integrin affinity regulation but also required for accessibility to biological ligands. Integrin αVβ3 with the αV_GFFKR/GAAKR cytoplasmic mutation, which induces inside-out activation, bound ligands with high affinity in non-activating conditions and was in the extended conformation, as shown by constitutive LIBS epitope exposure. However, this constitutive LIBS exposure and ligand binding activity was reversed when a disulfide bond was introduced between the αVβ-propeller domain and the β3 I-EGF 4 domain, which locked the integrin in the bent conformation. It has been demonstrated that activating mutations in the transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions of αIIbβ3 induce constitutive LIBS epitope exposure (7, 35), showing that integrin extension can occur in the absence of ligand binding. These results are consistent with a wide body of evidence that suggests that integrin affinity regulation is concomitant with extension during inside-out activation (11). Integrin αVβ3 with a disulfide bond between the αVβ-propeller domain and the β3 I-EGF 4 domain and activated with a hybrid domain glycan wedge appeared to remain in the bent conformation as intended because the LIBS1 and D3 epitopes were not exposed. Although the glycan wedge mutant activated binding to soluble fibronectin, this binding was completely reversed by the introduced disulfide bond. However, the double mutant with the glycan wedge and the disulfide to restrain the bent conformation bound Fn7–10 and Fn9–10 fragments, although binding was lower than in the absence of the disulfide. These results demonstrate that the introduced disulfide did not prevent activation and that integrin extension is required for access to the large macromolecular ligands to which integrins bind physiologically.

In addition, we demonstrate that Mn2+ and binding of Fn7–10 induce LIBS epitope exposure in integrin αVβ3, suggesting that these agents induced αVβ3 integrin extension on the cell surface. Notably, we used the same Mn2+ concentration (0.2 mM) and fibronectin fragment concentration (1 mg/ml) as used in a recent EM study that suggested that after binding of these agents, αVβ3 remained in a bent conformation (21). However, aggregation was present in the EM preparations, which may have resulted in the absence of sampling of extended integrins (11, 21). Our results on cell surface αVβ3 are consistent with other EM studies on soluble αVβ3 bound to cyclo-RGDfV peptide (4), soluble αIIbβ3 bound to RGD peptide (13), and α5β1 headpiece fragments bound to Fn7–10 (14), which showed that integrins were extended and/or had the open headpiece conformation with the hybrid domain swung out after ligand binding. In conclusion, our results fail to show any role for a deadbolt in the integrin in which this model was proposed, αVβ3, or in integrin αIIbβ3, suggest that integrins extend on the cell surface under conditions in which extension was not found in one EM study, and show that integrin extension is important for both affinity regulation and ligand accessibility.

The abbreviations used are

- EM

electron microscopy

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- I-EGF

integrin-epidermal growth factor-like

- LIBS

ligand-induced binding site

- Fn

fibronectin

- Fg

fibrinogen

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- CHO

Chinese hamaster ovary

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL48675 (to T. A. S.) and HL44612 (to P. J. N.).

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shattil SJ, Newman PJ. Blood. 2004;104:1606–1615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Diefenbach B, Zhang R, Dunker R, Scott DL, Joachimiak A, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Science. 2001;294:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.1064535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Cell. 2002;110:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishida N, Xie C, Shimaoka M, Cheng Y, Walz T, Springer TA. Immunity. 2006;25:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tadokoro S, Shattil SJ, Eto K, Tai V, Liddington RC, de Pereda JM, Ginsberg MH, Calderwood DA. Science. 2003;302:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.1086652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luo BH, Springer TA, Takagi J. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:776–786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim M, Carman CV, Springer TA. Science. 2003;301:1720–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1084174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vinogradova O, Velyvis A, Velyviene A, Hu B, Haas TA, Plow EF, Qin J. Cell. 2002;110:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takagi J, Springer TA. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:141–163. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo BH, Springer TA. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao T, Takagi J, Wang Jh, Coller BS, Springer TA. Nature. 2004;432:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki K, Mitsuoka K, Fujiyoshi Y, Fujisawa Y, Kikuchi M, Sekiguchi K, Yamada T. J Struct Biol. 2005;150:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takagi J, Strokovich K, Springer TA, Walz T. EMBO J. 2003;22:4607–4615. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beglova N, Blacklow SC, Takagi J, Springer TA. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:282–287. doi: 10.1038/nsb779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mould AP, Symonds EJ, Buckley PA, Grossmann JG, McEwan PA, Barton SJ, Askari JA, Craig SE, Bella J, Humphries MJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39993–39999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang RH, Tng E, Law SK, Tan SM. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29208–29216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503239200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mould AP, Travis MA, Barton SJ, Hamilton JA, Askari JA, Craig SE, Macdonald PR, Kammerer RA, Buckley PA, Humphries MJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4238–4246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412240200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tng E, Tan SM, Ranganathan S, Cheng M, Law SK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54334–54339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407818200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo BH, Strokovich K, Walz T, Springer TA, Takagi J. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27466–27471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adair BD, Xiong JP, Maddock C, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA, Yeager M. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:1109–1118. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Blood. 2003;102:1155–1159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo BH, Springer TA, Takagi J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2403–2408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438060100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newman PJ, Allen RW, Kahn RA, Kunicki TJ. Blood. 1985;65:227–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson JA, Nyree CE, Newman PJ, Aster RH. Blood. 2003;101:937–942. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kouns WC, Newman PJ, Puckett KJ, Miller AA, Wall CD, Fox CF, Seyer JM, Jennings LK. Blood. 1991;78:3215–3223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takagi J, Erickson HP, Springer TA. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:412–416. doi: 10.1038/87569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shattil SJ, Hoxie JA, Cunningham M, Brass LF. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11107–11114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamata T, Tieu KK, Springer TA, Takada Y. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44275–44283. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tokuhira M, Handa M, Kamata T, Oda A, Katayama M, Tomiyama Y, Murata M, Kawai Y, Watanabe K, Ikeda Y. Thromb Haemostasis. 1996;76:1038–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Honda S, Tomiyama Y, Pelletier AJ, Annis D, Honda Y, Orchekowski R, Ruggeri Z, Kunicki TJ. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11947–11954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frelinger AL, Cohen I, Plow EF, Smith MA, Roberts J, Lam SCT, Ginsberg MH. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:6346–6352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kouns WC, Wall CD, White MM, Fox CF, Jennings LK. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20594–20601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faraday N, Goldschmidt-Clermont P, Dise K, Bray PF. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;123:728–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo BH, Carman CV, Takagi J, Springer TA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:3679–3684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409440102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Partridge AW, Liu S, Kim S, Bowie JU, Ginsberg MH. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7294–7300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnaout MA, Mahalingam B, Xiong JP. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:381–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dechantsreiter MA, Planker E, Matha B, Lohof E, Holzemann G, Jonczyk A, Goodman SL, Kessler H. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3033–3040. doi: 10.1021/jm970832g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehirchiou D, Xiong YM, Li Y, Brew S, Zhang L. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8324–8331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo BH, Takagi J, Springer TA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10215–10221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hato T, Yamanouchi J, Yakushijin Y, Sakai I, Yasukawa M. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2006;4:2278–2280. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barton SJ, Travis MA, Askari JA, Buckley PA, Craig SE, Humphries MJ, Mould AP. Biochem J. 2004;380:401–407. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta V, Gylling A, Alonso JL, Sugimori T, Ianakiev P, Xiong JP, Arnaout MA. Blood. 2006 doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-056689. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zang Q, Lu C, Huang C, Takagi J, Springer TA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22202–22212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]