Abstract

Background

Bulleyaconitine A (BLA) is an active ingredient of Aconitum bulleyanum plants. BLA has been approved for the treatment of chronic pain and rheumatoid arthritis in China, but its underlying mechanism remains unclear.

Methods

The authors examined (a) the effects of BLA on neuronal voltage-gated Na+ channels in vitro under the whole-cell patch-clamp configuration and (b) the sensory and motor functions of rat sciatic nerve after single BLA injections in vivo.

Results

BLA at 10 μM did not affect neuronal Na+ currents in clonal GH3 cells when stimulated infrequently to +50 mV. When stimulated at 2 Hz for 1,000 pulses (+50 mV for 4 ms), BLA reduced the peak Na+ currents by >90%. This use-dependent reduction of Na+ currents by BLA reversed little after washing. Single injections of BLA (0.2 ml at 0.375 mM) into the rat sciatic notch not only blocked sensory and motor functions of the sciatic nerve but also induced hyperexcitability, followed by sedation, arrhythmia, and respiratory distress. When BLA at 0.375 mM was co-injected with 2% lidocaine (~80 mM) or epinephrine (1:100,000) to reduce drug absorption by the blood-stream, the sensory and motor functions of the sciatic nerve remained fully blocked for ~4 hrs and regressed completely after ~7 hrs with minimal systemic effects.

Conclusions

BLA reduces neuronal Na+ currents strongly at +50 mV in a use-dependent manner. When co-injected with lidocaine or epinephrine, BLA elicits prolonged block of both motor and sensory functions in rats with minimal adverse effects.

Introduction

For centuries, roots harvested from a variety of Aconitum plants (monkshood) have been used in Chinese and Japanese medicine for analgesic, antirheumatic, and neurological indications1. The tuber of Aconitum ferox was also used by Himalayan hunters to poison arrows. There are numerous alkaloids (~170) isolated from Aconitum plants, including various “aconitine-like” and “lappaconitine-like” diterpenoid compounds2;3. Both types of diterpenoid alkaloids exhibit strong analgesic properties in vivo. Furthermore, lappaconitine appears to block Na+ currents irreversibly4, whereas aconitine not only reduces Na+ currents but also shifts the voltage dependence of Na+ channel activation toward the hyperpolarizing direction and is classified as an “activator” of Na+ channels5. As a result of this voltage shift in activation, aconitine not only causes cardiac arrhythmia but also induces repetitive discharges in nerve cells.

Diterpenoid alkaloids such as bulleyaconitine A (BLA; Fig. 1), 3-acetylaconitine, and lappaconitine have been subjected to clinical trials. To date, BLA in solution (0.2 mg/2ml; i.m.) or in tablet (0.4mg) has been introduced into the clinic for the treatment of chronic pain and rheumatoid arthritis in China. The central catecholaminergic and serotoninergic systems are thought to be involved in analgesia induced by diterpernoid alkaloids, although the details of their involvement are unknown1;2. While the effects of aconitine on Na+ channels are well known, a literature search of BLA using PubMed yields no information regarding this subject. BLA reportedly induced sciatic nerve block in mice with an inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.0029%2. However, it was unclear how long the sciatic nerve block lasted. The goals of this study are (1) to examine the actions of BLA on neuronal Na+ channels in vitro and (2) to determine the duration of rat sciatic nerve block by BLA in vivo. During the course of this investigation, we found that BLA induced acute systemic side effects in rats, including hyperexcitability, arrhythmia, sedation, and, respiratory distress, as detailed in the Results section. Attempts were made to reduce such systemic toxicity by co-administration of lidocaine or epinephrine. Our results suggest that the systemic toxicity of BLA can be minimized by the reduction of blood flow at the injected site and that BLA displays long-acting local anesthetic properties under appropriate conditions. Implications of our in vitro and in vivo studies regarding the mechanism of BLA and other Aconitum alkaloids as analgesic agents will be discussed.

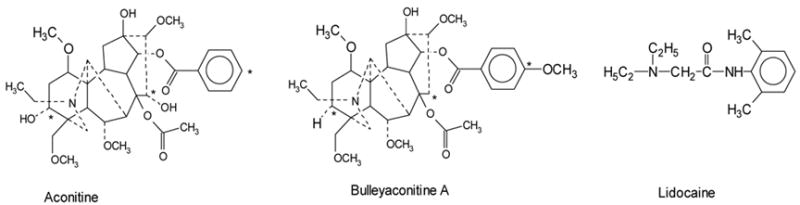

Figure 1. Chemical structures.

Aconitine (MW: 645.7) is shown on the left side, bulleyaconitine A (643.8) on the middle, and lidocaine (234.3) on the right. The differences between aconitine and bulleyaconitine A are labelled with * at three postitions. All compounds contain a tertiary amine and a phenyl moiety. Lidocaine, however, is less than half the size of aconitine or bulleyaconitine A.

Materials and Methods

Drugs

BLA and aconitine were purchased from Axxora LLC, San Diego, CA., and K & K Laboratories, Inc. Plainview, N.Y., respectively. Aconitine was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at a 10-mM stock solution and stored at 4°C until use. BLA was first added with H2O and dissolved by titrating with 1N HCl; the dissolved solution contained 100 mM BLA in ~0.2N HCl. The acidic solution was then neutralized by 1M Tris-base. The final BLA stock solution (50 mM in ~0.1M Tris-HCl) was stored at 4°C until use. Lidocaine-HCl 2% (in 0.6% NaCl) and epinephrine (1:1,000 or 1mg/ml) vials were purchased from Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL. Epinephrine was diluted to 1:100,000 or 10 μg/ml in 0.9 % NaCl saline.

Cell Culture

Rat pituitary GH3 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). GH3 cells express various neuronal Na+ channels, including Nav1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.6 isoforms6. Cultured GH3 cells were plated on 30-mm culture dishes and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in DMEM (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Whole-Cell Voltage-Clamp Experiments

Whole-cell configuration was used to record Na+ currents of GH3 cells in culture dishes7. Borosilicate micropipettes (Drummond Scientific Company, Broomall, PA) were pulled (P-87, Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA) and heat-polished. Pipette electrodes contained 100 mM NaF, 30 mM NaCl, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. The advantages of using this high intracellular Na+ concentration are that (1) outward Na+ currents are visible at +50 mV and (2) the voltage error caused by the access resistance is less serious with outward than with inward currents8. The pipette electrodes had a tip resistance of 0.5 to 1.0 MΩ. Access resistance was generally 1 to 3 MΩ. We minimized the series resistance (>85%) and corrected the leak and capacitance using the Axopatch 200B device. Holding potential was set at −140 mV.

Experiments were performed at room temperature (21–24°C) under a Na+-containing bath solution with 65 mM NaCl, 85 mM choline Cl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES adjusted to pH 7.4 with tetramethylammonium hydroxide. Cultured dishes containing GH3 cells were rinsed with the bath solution and used directly as a recording chamber for current measurements. The liquid junction potential was not corrected. Drugs were diluted with the external bath solution and applied to the cell surface from a series of small-bore glass capillary tubes.

Drug Injection and Neurobehavioral Examination

The protocol for animal experimentation was reviewed and approved by the Harvard Medical Area Standing Committee on Animals, Boston, MA. Male Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA) and kept in the animal housing facilities at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, with controlled humidity (20%–30% relative humidity), room temperature (24ºC), and a 12-hour (6:00 AM–6:00 PM) light-dark cycle. Before the experiments, the animals were handled to familiarize them with the behavioral investigator, experimental environment, and specific experimental procedures for reduction of stress during experiments. At the time of injection, rats weighed approximately 250–300g. All rats were anesthetized by inhalation of a small amount of sevoflurane (Sevofrane, Abbott Laboratory, North Chicago, IL). After induction of inhalation anesthesia, BLA in a volume of 200 μl was injected at the sciatic notch of the left hind limb with a 27-G needle connected to a tuberculin syringe. BLA at a 50 mM stock solution was diluted in 0.9% NaCl saline, in 2% lidocaine, or in (1:100,000) epinephrine solution. The final BLA concentrations were 0.375 mM and 0.75 mM. All drug solutions were freshly prepared before injections, and the pH ranged from 5.0 to 6.5 (the pH was not adjusted because it was buffered quickly by the pH of 7.4 of the tissue fluid).

Neurobehavioral examination by a blinded investigator included assessment of motor function and nocifensive response immediately before injection and at various intervals after injection. The right hind limb was used as a control. Nocifensive reaction was evaluated as described9 by the withdrawal reflex or vocalization to pinch of a skin fold over the lateral metatarsus (cutaneous pain) and of the distal phalanx of the fifth toe (deep pain). We graded the combination of withdrawal reflex, escape behavior, and vocalization on a scale of 0–3: 0 (baseline or normal, brisk withdrawal reflex, normal escape behavior, and strong vocalization), 1 (mildly impaired), 2 (moderately impaired), and 3 (totally impaired nocifensive reaction).

Motor function was evaluated by holding the rat upright with the hind limb extended so that the distal metatarsus and toes supported the animal’s weight and thereby measuring the extensor postural thrust of the hind limbs as the gram force applied to a digital platform balance (Ohaus Lopro; Fisher Scientific, Florham Park, NJ)9. The reduction in this force, representing reduced extensor muscle contraction due to motor blockade, was calculated as a percentage of the control force. The motor function score was graded with respect to the preinjection control value (range, 120–170 g) as follows: 0 (no block or normal), 1 (mild block; force between 100% and 50% of preinjection control value), 2 (moderate block; force between 50% of the preinjection control value and 20 g), and 3 (complete block, force less than 20 g, which is referred to as the weight of the flaccid limb).

Statistical Analysis

An unpaired Student’s t test was used to evaluate block of Na+ currents. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the significance of differences in onset to full sensory block, in recovery from sensory block, and in the area under the curve (AUC) between groups (2% lidocaine, 0.375 mM BLA, 0.375 mM BLA+2% lidocaine, 0.375 mM BLA+epinephrine). Given a significant F test (P < 0.05), a Bonferroni adjustment was performed to obtain post-hoc pairwise tests for contrasts of interest. Because of the ordinal categorical nature of the block scores, an overall test for drug effect was also obtained via generalized estimating equations (GEE)10. A cumulative logistic ordinal model was fit with a linear and quadratic trend in time and time by group interaction. The overall P-value was calculated via PROC GENMOD (SAS 9.1, Carey, NC). Both statistic methods yielded the same conclusions.

Results

BLA at 10 μM did not interact with resting or inactivated states of neuronal Na+ channels

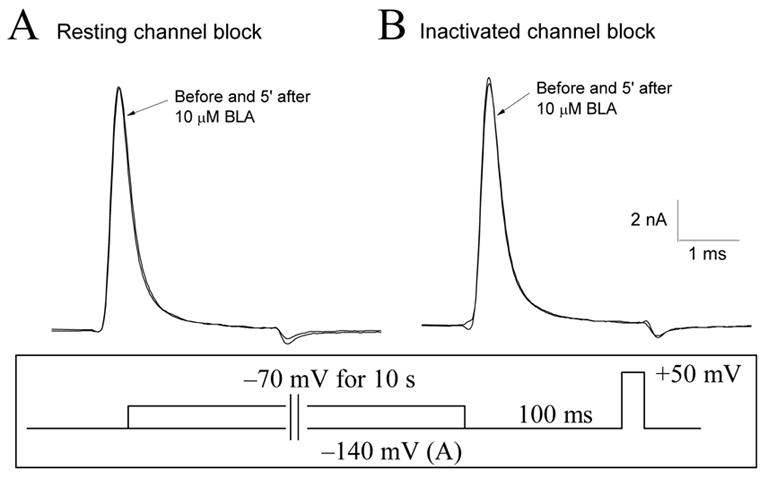

Figure 2A shows representative traces of outward Na+ currents recorded from GH3 cells at +50 mV before and after external application of 10 μM BLA for 5 min. These cells were held at −140 mV holding potential. The Na+ currents were outward because the pipette solution (intracellular) contained 130 mM Na+ ions. There were no apparent BLA effects on either the peak amplitude or the current kinetics when the cell was stimulated infrequently (once every 30 s). The ratio of peak currents before and after 10 μM BLA was 96.5 ± 1.6 % (n = 7), demonstrating that BLA does not block the resting Na+ channels at −140 mV significantly. Since local anesthetics are known to bind preferentially with inactivated Na+ channels11, we tested whether BLA also displayed such a preference for inactivated Na+ channels. To address this question, we applied a conditioning pulse of −70 mV for 10 s to allow fast-inactivated Na+ channels to interact with 10 μM BLA (Fig. 2B). Drug-free inactivated Na+ channels should be recovered rapidly within 100 ms, whereas drug-bound inactivated Na+ channels should remain blocked, as shown for local anesthetics with this pulse protocol12;13. Under this condition, we found again that BLA did not produce any apparent effects on Na+ currents. The ratio of peak currents before and after 10 μM BLA was 99.9 ± 1.9% (n = 4). We therefore conclude that, unlike local anesthetics, BLA does not interact with inactivated Na+ channels significantly. Preliminary results showed that an increase of the BLA concentration to 100 μM again did not produce much block (< 10%) of inactivated Na+ channels. This small block could be due to the block of the open Na+ channels during the test pulse as described next.

Figure 2. Minimal or no block of resting and inactivated Na+ channels by 10 μM BLA.

(A) Superimposed traces of Na+ currents were recorded before and 5 minutes after application of 10 μM BLA. For the resting block by BLA, the cell was held at −140 mV and stimulated once every 30 s by a brief test pulse (+50 mV for 3 ms; inset). (B) For the inactivated block by BLA, the cell was depolarized to −70 mV for 10 s (inset), which provided sufficient time for inactivated Na+ channels to interact with BLA. Superimposed traces of Na+ currents before and after application of 10 μM BLA were recorded by a brief test pulse. An interpulse (−140 mV for 100 ms; inset), which allowed drug-free inactivated Na+ channels to recover, was applied before the brief test pulse. Again, the inactivated block by BLA was minimal.

BLA at 10 μM blocked only the open state of neuronal Na+ channels in a use-dependent manner

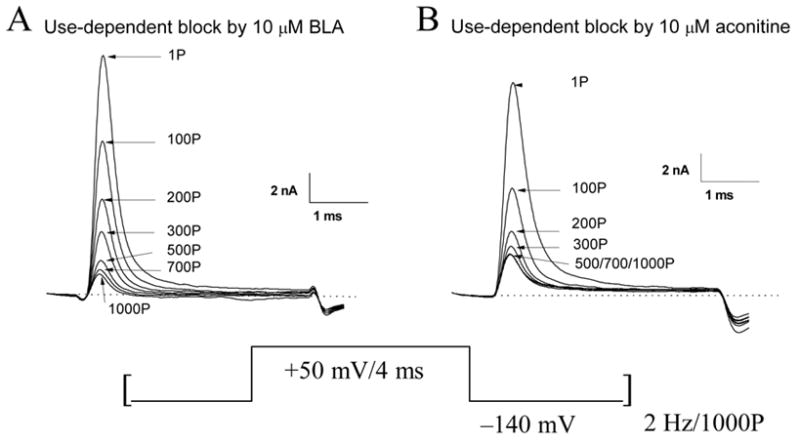

When the cell was stimulated at 2 Hz, however, Na+ currents were progressively reduced by 10 μM BLA. Figure 3A shows representative traces of Na+ currents at +50 mV with 1,000 repetitive pulses (ranging from 1P to 1000P). Peak Na+ currents decreased continuously until they reached a steady-state level. The amount of reduction by 10 μM BLA was 91.2 ± 1.2% (n = 6). Under identical conditions, aconitine at 10 μM inhibited Na+ currents by 84.0 ± 0.9% (n = 6) (Fig. 3B). The average block for 10 μM BLA was therefore larger than that for 10 μM aconitine; this degree of difference is statistically significant (P < 0.05). Like the results of BLA at 10 μM shown in Fig. 2A and B, aconitine at 10 μM also did not interact with the resting or inactivated Na+ channels when the cells were stimulated infrequently. These results demonstrated that BLA and aconitine interact only with open states of Na+ channels in a use-dependent manner. Such a use-dependent binding phenotype is commonly found among Na+ channel activators5;14.

Figure 3. Use-dependent block of Na+ currents by BLA and by aconitine.

(A) Superimposed traces of Na+ currents were recorded in the presence of 10 μM BLA with 1,000 repetitive pulses (+50 mV for 4 ms) applied at 2 Hz. The cell was perfused with 10 μM BLA ~5 min before repetitive pulses. Current traces are labeled with the number of corresponding pulses, ranging from 1P to 1000P. (B) Superimposed traces of Na+ currents were recorded in the presence of 10 μM aconitine with 1,000 repetitive pusles. The conditions were the same as described in (A).

Residual BLA-induced Na+ currents appeared at voltages near the activation threshold

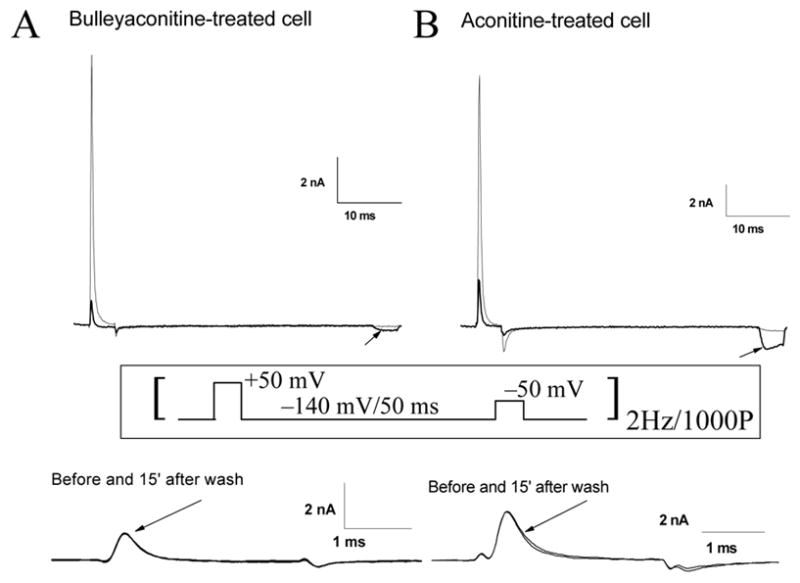

In addition to the large reduction of Na+ currents, we assessed whether BLA shifted the voltage dependence of Na+ channel activation as reported for aconitine. To detect such a voltage shift, we used a two-pulse protocol (Fig. 4, inset) implemented by Rao and Sikdar15. A conditioning pulse (+50 mV for 4 ms) was applied 50 ms ahead of a second test pulse (−50 mV for 4 ms). The conditioning pulse at +50 mV was used to elicit the use-dependent block of Na+ currents by 10 μM BLA, whereas the test pulse at −50 mV was meant to measure the BLA-induced threshold Na+ currents. The two-pulse protocol was applied at 2 Hz for 1,000 pulses. Without BLA, few or no Na+ currents were detected at this activation threshold voltage of −50 mV. We defined this voltage as the activation threshold since Na+ currents in GH3 cells were activated near −50 to −40mV8. When BLA was applied externally at 10 μM, we saw no increase in Na+ currents at −50 mV initially (Fig. 4A, top; thin trace). However, residual BLA-modified Na+ currents gradually appeared during repetitive pulses, while the peak currents at the conditioning pulse reduced progressively, reaching a steady-state level during 1,000 repetitive pulses (Fig. 4A, top; thick trace). Once developed, this use-dependent block by 10 μM BLA reversed little after washing with the drug-free solution for 15 min (Fig. 4A, bottom). This was also true for BLA-induced threshold Na+ currents at −50 mV. The inward peak current at the second pulse of 1,000P was measured, inverted in sign, normalized with the peak current at the first conditioning pulse (1P) and yielded a value of 3.6 ± 0.5% (n = 5). Interestingly, residual aconitine-modified Na+ currents appeared significantly larger (9.4 ± 1.0%, n = 6; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B, top; thick trace) than those induced by 10 μM BLA under identical conditions. These results demonstrated that BLA elicits only residual BLA-modified Na+ currents near the activation threshold and appears less effective than aconitine in inducing the threshold Na+ currents at −50 mV. Again, the use-dependent block at +50 mV by 10 μM aconitine (Fig. 4B, bottom) and its induced threshold Na+ currents at −50 mV reversed little upon washing for 15 min.

Figure 4. BLA- and aconitine-induced threshold Na+ currents at −50 mV.

(A; top) Superimposed traces of residual BLA-induced Na+ currents at −50 mV were recorded before (thin trace) and after (thick trace) 1,000 repetitive pulses (2 Hz). BLA at 10 μM was applied ~5 min before repetitive pulses. The cell was held at −140 mV. The conditioning voltage at +50 mV for 4 ms was applied 50 ms before the test voltage at −50 mV for 4 ms. Residual BLA-induced Na+ currents at −50 mV were only evident after 1,000 repetitive pulses (thick trace; arrow). Once developed, the reduction of peak Na+ currents at the conditioning voltage reversed little, as demonstrated by superimposed traces of Na+ currents before and after washing with drug-free bath solution for 15 min (A; bottom). (B) Superimposed traces of aconitine-induced threshold Na+ currents at −50 mV were recorded before (thin trace) and after (thick trace) 1,000 repetitive pulses (2 Hz). Aconitine at 10 μM was applied ~5 min before repetitive pulses. The conditions and the pulse protocol were the same as in (A; inset). The reduction of peak Na+ currents at the conditioning voltage again reversed little after washing (B, bottom).

Sensory and motor block by single injections of BLA into the rat sciatic notch

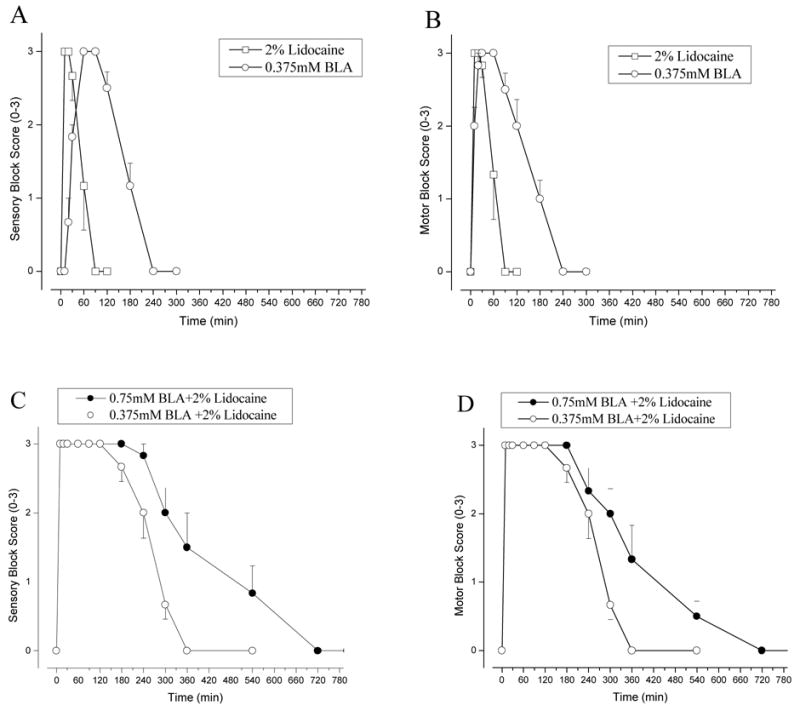

To determine the degree and the duration of sciatic nerve block by BLA, we injected BLA at 0.375 mM into the rat sciatic notch in a volume of 200 μL and examined the motor and sensory functions of the hind limb. Figure 5 A and B show the sensory and motor block of rat sciatic nerve, respectively, induced by 0.375 mM BLA (0.0241% BLA or a total of 48.2 μg BLA per injection; open circle). Our results indicated that both sensory and motor block elicited by BLA at 0.375 mM reached its complete block ~30–60 min after injection and started to recover 1.5–2 hrs after injection. Sciatic nerve functions recovered fully 4 hrs after injection. For comparison, we also measured the duration of block by ~80 mM lidocaine (2 % or 4 mg per injection; open square) in a volume of 200 μL. Block elicited by BLA at 0.375 mM had a slower onset but a longer duration of sensory and motor block than that by 2% lidocaine (open circle vs. open square in Fig. 5). Table 1 lists the times for the onset and recovery from the sensory block of 2% lidocaine and 0.375 mM BLA. The slower onset for BLA was likely due to the relatively low concentration applied (0.375 mM vs. 80 mM, or a factor of ~200), whereas the longer duration of sciatic nerve block was due to strong use-dependent block of Na+ currents (Fig. 3) and slow BLA reversibility by washing (Fig. 4). Table 2 lists the area under the curve (AUC) of sensory and motor block by 2% lidocaine and 0.375 mM BLA. The AUC of 0.375 mM BLA for sensory and motor block is significantly larger than that of 2% lidocaine, respectively. We did not observe a differential block between the sensory and motor block by 0.375 mM BLA or by 2 % lidocaine (Table 2).

Figure 5. Rat sciatic nerve block by BLA, lidocaine, and by both combined.

(A) Nociceptive sciatic nerve blockade by BLA at 0.375mM (open circle) and by 2% lidocaine (open square) (n = 6 per group; mean ± SEM) were measured at various times as described in Methods. (B) Time courses of motor blockade were measured concurrently under the same conditions as in (A). (C) The time courses of rat sciatic nerve block were measured when rats were injected with 2% lidocaine with BLA at 0.375mM and 0.75 mM (n = 6 per group; mean ± SEM). (D) The time courses of motor blockade were measured concurrently under the same conditions as in (C).

Table 1. Analgesic parameters.

Onset and recovery times from sensory block are compared among various groups. Data were derived from the sensory block measurement in rat sciatic nerve (mean ± SEM) as shown in Fig. 5A, 6A, and 7A. Epinephrine was diluted to 1:100,000 (or 10 μg/ml). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for overall mean differences in onset to full sensory block and complete recovery from sensory block values in 2% lidocaine, 0.375 mM BLA, 0.375 mM BLA+2% lidocaine, and 0.375 mM BLA+epinephrine groups. Given a significant F test (P < 0.05), pairwise post-hoc Bonferroni tests were performed for multiple pairwise comparisons.

| Group | N | Onset to full sensory block (in minutes) | Recovery from sensory block (in minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2% lidocaine | 6 | 3.33 ± 0.21 | 66.67 ± 9.19 |

| 0.375mM BLA | 6 | 41.67 ± 1.67 ** | 230.00 ± 6.32 ** |

| 0.375mM BLA+2% lidocaine | 6 | 3.50 ± 0.22 | 330.00 ± 10.95 **,‡‡ |

| 0.375mM BLA+epinephrine | 6 | 35.83 ± 4.90 ** | 440.00 ± 12.65 **,‡‡ |

P < 0.001, compared with the 2% lidocaine group.

P < 0.001, compared with the 0.375 mM BLA group. The GEE statistic analyses likewise agreed with these conclusions.

Table 2. Relative areas under the curves (AUC) for sensory and motor block of the sciatic nerve.

The AUCs of individual rats (e.g., Fig. 5–7 for averaged data) were integrated and the values (in score x time) for sensory and motor block are listed. Epinephrine was diluted to 1:100,000. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for overall mean differences of AUCs in 2% lidocaine, 0.375 mM BLA, 0.375 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine, and 0.375 mM BLA plus epinephrine groups. Given a significant F test (P < 0.05), pairwise post-hoc Bonferroni tests were performed for multiple pairwise comparisons.

| Drug injected | N | AUC for sensory block | AUC for motor block |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2% lidocaine

0.375mM BLA 0.375mM BLA + 2% lidocaine 0.375mM BLA + Epinephrine |

6

6 6 6 |

148.33 ± 21.51

405.83 ± 26.25* 755.00 ± 45.61**,‡‡ 1048.33 ± 62.22**,‡‡ |

156.67 ± 20.11

423.33 ± 34.22* 755.00 ± 45.61**,‡‡ 725.00 ± 51.58**,‡‡ |

| 0.75mM BLA + 2% lidocaine

0.75mM BLA + Epinephrine |

6

6 |

1235.00 ±150.73†

1011.67 ± 98.14 |

1125.00 ±135.72†

875.00 ± 56.21 |

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001 (with F[3,20]=87.52 for sensory and 50.35 for motor), compared to 2% lidocaine group.

P < 0.001 (with F[2,15]=46.74 for sensory and 17.08 for motor), compared to 0.375mM BLA group. The GEE statistic analyses likewise supported these conclusions. An unpaired Student’s t test was used to evaluate mean differences of AUCs between 0.75 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine and 0.375 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine,

P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No statistical significance in AUC was found between 0.375 mM with epinephrine and 0.75 mM BLA with epinephrine.

Besides sensory and motor block of sciatic nerve functions, we also found clear evidence of adverse effects induced by single injections of 0.375 mM BLA. After injection, the initial symptom was tetanic extension observed at the injected hindlimb, which also displayed hypersensitivity to toe pinch. Three out of six rats developed diarrhea during this period. When complete sensory block occurred ~30 min after injection, additional systemic adverse effects took place in succession, such as sedation, sleepiness, and shallow breathing. It took ~6 hrs for all rats to recover fully from these symptoms to baseline conditions.

When BLA at 0.75 mM was injected into the rat sciatic notch, it caused severe adverse effects. Soon after the administration of 0.75 mM BLA, tetanic extension at the injected hindlimb developed just as mentioned before at 0.375 mM BLA. The initial side effects also included hyperalgesia to toe pinch, and some rats displayed vocal responses even to light touch. Thirty minutes later, rats began to show respiratory distress with air hunger, stridor, and intermittent deep breathing. Arrhythmogenic actions of BLA with tachycardia and then bradycardia to arrest were also noted. The contralateral legs displayed motor and sensory block to a certain extent, but a full blockade was never reached at the contralateral side after BLA injection. All rats eventually died of respiratory failure and asystole. It is noteworthy that the full duration of the sciatic nerve block induced by 0.75 mM BLA could not be measured since rats died within 1–2 hrs.

Co-administration of BLA with 2% lidocaine into the rat sciatic notch

In order to minimize the systemic side effects, we sought to co-administer BLA with 2% lidocaine. Since lidocaine is known to reduce blood flow in sciatic nerve16, we reasoned that a longer duration of nerve block by BLA would occur after co-injection. Figure 5C and D show the sensory and motor block of sciatic nerve functions, respectively, by 0.375 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine (open circle) and 0.75 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine (closed circle). The time to reach the full block by 0.375 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine was 3.5 min (Table 1), because of the rapid on-rate of 2% lidocaine. The duration of sensory and motor block by co-injection of drugs was concentration dependent for most of the time points during recovery and the area under curve was significantly larger than that by a single drug alone (Fig. 5 A–B vs. Fig. 5 C–D; Table 2 and 3).

Table 3. GEE comparisons of sensory and motor block of the sciatic nerve functions.

Results from the GEE analysis for BLA and adjuvants vs. 2% lidocaine are listed. A cumulative logistic ordinal model was fit with a linear and quadratic trend in time and time by group interaction (all significance tests use 2 df for group and group by time interaction).

| Drug injected | N | Sensory block | Motor block |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.375mM BLA | 6 | Chi-square=11.03, p=0.0040 | Chi-square= 9.89, p=0.0071 |

| 0.375mM BLA + 2% lidocaine | 6 | Chi-square=11.23, p=0.0036 | Chi-square=11.23, p=0.0036 |

| 0.375mM BLA + epinephrine | 6 | Chi-square=11.43, p=0.0033 | Chi-square=10.54, p=0.0051 |

| 0.750mM BLA + 2% lidocaine | 6 | Chi-square=11.47, p=0.0032 | Chi-square=11.44, p=0.0033 |

| 0.750mM BLA + epinephrine | 6 | Chi-square=10.03, p=0.0066 | Chi-square=10.57, p=0.0051 |

Assuming that lidocaine reduces blood flow in rat sciatic nerve, we should also observe less systemic side effects after co-adminstration of BLA with 2% lidocaine. Indeed, rats displayed much less adverse effects after co-injection with 2% lidocaine than rats injected with BLA alone. After co-injection of 0.75 mM BLA with 2% lidocaine, the drug mixture likewise induced sedation and respiratory distress, but to a much lesser extent. As a result, all rats survived after co-injection of 0.75 mM BLA with 2% lidocaine, unlike all of those died after injection with 0.75 mM BLA alone. As for rats with co-administration of 0.375 mM BLA plus 2% lidocaine, we observed only minor sedation and minimal respiratory distress.

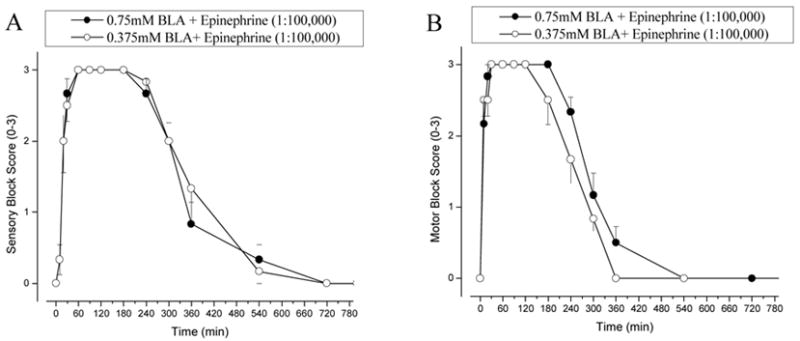

Co-administration of BLA with epinephrine (1:100,000) into the rat sciatic notch

The prolonged block by co-administration of BLA with 2% lidocaine suggests that lidocaine limits the absorption of BLA by blood-stream. To confirm this interpretation, we co-administered BLA with epinephrine (1:100,000). Figure 6 A and B show the sensory and motor block of sciatic nerve functions, respectively, by 0.375 mM BLA plus epinephrine (1:100,000) (open circle) and 0.75 mM BLA plus epinephrine (1:100,000) (closed circle). Epinephrine significantly prolonged the duration of nerve block by BLA (Fig. 6 vs. Fig. 5A,B; Table 2). There were, however, quantitative differences in sensory and motor block between 2% lidocaine and epinephrine (1;100,000) after co-administration with BLA. First, the on-set of block was faster for co-injection with 2% lidocaine (Table 1) because lidocaine itself has a very fast onset for nerve block (Fig. 5A,B). Second, the duration of block by BLA was not clearly concentration dependent when co-injected with epinephrine (1:100,000) (Fig. 6; closed circle vs. open circle; Table 2, P > 0.05). The reason for this second phenomenon is unclear but could be due to the wear-off of epinephrine in vessel constriction. The general physical conditions for rats injected with BLA plus epinephrine (1:100,000) were even better than those with BLA plus 2% lidocaine, both at 0.375 mM and 0.75 mM BLA concentrations. Except for a transient hyperexcitability in one of six rats injected with 0.75 mM BLA plus epinephrine, we observed few respiratory or cardiac problems.

Figure 6. Time courses of rat sciatic nerve block by co-injection of BLA and epinephrine.

A) The time courses of rat nociceptive sciatic nerve block when co-injected with epinephrine (1:100,000) and BLA at 0.375mM or at 0.75 mM (n = 6 per group; mean ± SEM). (B) The time courses of motor blockade were measured under identical conditions as in (A).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that (a) BLA strongly reduces neuronal Na+ currents at +50 mV in a use-dependent manner, and (b) BLA elicits long-lasting sensory and motor block of rat sciatic nerve functions after single injections. In addition, we have provided the means to lessen systemic side effects of BLA by co-administration with lidocaine or with epinephrine. The implications of these BLA actions in vitro and in vivo are discussed as follows.

BLA reduces neuronal Na+ currents in a use-dependent manner

BLA at 10 μM greatly reduced neuronal Na+ currents during repetitive pulses to +50 mV. Up to 90% of peak Na+ currents were abolished after 1,000 repetitive pulses. Concurrently, residual BLA-induced threshold Na+ currents appeared at −50 mV. We also found that BLA did not interact with the resting and inactivated Na+ channels significantly. These BLA actions are qualitatively similar to those of other Na+ channel activators such as batrachotoxin, veratridine, and aconitine14. All of these activators interact with open Na+ channels preferentially, reduce single-channel conductance, shift the voltage dependence of Na+ channel activation, and induce repetitive firings in excitable membranes.

Quantitatively, however, BLA reduces more Na+ currents at +50 mV during repetitive pulses and induces fewer residual threshold Na+ currents than aconitine. Once developed, the use-dependent block of Na+ currents by BLA reversed little after washing for 15 min. The different actions of BLA and aconitine on Na+ channels (Figs. 3 and 4) can be readily explained by the hypothesis that BLA reduces the single-channel conductance much more than aconitine does. This in turn will result in a greater reduction of Na+ currents at +50 mV and a smaller amount of threshold Na+ currents carried by BLA-modified Na+ channels at −50 mV. Single-channel analyses of BLA actions on Na+ channels will be needed in the future to confirm this hypothesis.

BLA displays long-acting local anesthetic properties in rats

Our in vivo studies in rats clearly show that BLA can elicit prolonged block of motor and sensory functions. When co-injected with lidocaine, the complete recovery from the sciatic nerve sensory block by 0.375 mM BLA is in fact taken longer (230 ± 6 min) than that induced by 0.5% bupivacaine (~15.4 mM) (151 ± 9 min, n = 6; P < 0.001), a bona fide long-acting local anesthetic9. The area under the curve of BLA (405.85 ± 26.25) is also significant larger than that of 0.5% bupivacaine (313.13 ± 23.45; p = 0.022, unpaired Student’s t test). We chose lidocaine for co-injection because it has a fast on rate for local anesthesia and because it reduces the blood flow in rat sciatic nerve16. The long action of BLA on sciatic nerve functions is consistent with the finding that the reduction of Na+ currents by BLA in vitro reverses little after washing for 15 min. In contrast, block by traditional local anesthetics can be rapidly reversed by wash. However, we caution that the therapeutic application of BLA as a local anesthetic along with lidocaine or epinephrine remains uncertain. First, we do not know whether BLA causes any damages in nerve tissues. Many Na+ channel blockers have been found to be toxic to the sciatic nerve, including drugs such as amitriptyline and its derivatives when injected at rat sciatic notch17. Second, BLA could be absorbed rapidly by the blood-stream and cause a variety of systemic side effects. Although co-administration of BLA with 2% lidocaine or with epinephrine (1:100,000) limits or even eliminates systemic side effects in rats, the potential of these unwanted events in the clinic setting must be considered.

Could BLA or other aconitine-like diterpenoid alkaloids be used as a template for drug design?

Aconitine is a well known neurotoxin that induces afterpotentials, hyperexcitability, and arrhythmia5. These detrimental effects are primarily caused by aconitine-induced threshold Na+ currents near the resting membrane potential (Fig. 4B, top). After considering the high toxicity of aconitine-like alkaloids, Ameri1 stated in a review article that therapeutic use of these compounds should be excluded. Despite of this warning, however, aconitine-like BLA has been used clinically in China. Our findings described in this report indicate that different aconitine-like alkaloids may have different effects on neuronal Na+ channels. First, BLA appears to reduce more neuronal Na+ currents than aconitine does at the same concentration (Fig. 3). Second, BLA induces fewer threshold Na+ currents at −50 mV than aconitine does (Fig. 4). Both of these BLA attributes would favor stronger sensory and motor block of sciatic nerve functions. The other important features of BLA are (a) its ready diffusion through the nerve sheath due to its lipophilic nature and (b) its high-affinity binding toward the open state of Na+ channels with relatively slow reversibility compared with traditional local anesthetics. On the basis of these considerations, BLA could conceivably be used as a template for drug design of long-acting local anesthetics. Such an approach may be fruitful as exemplified by cocaine, a naturally occurring prototype for the design of local anesthetics discovered more than 100 years ago. Assuming that we can develop a BLA-like alkaloid that blocks the single-channel conductance fully as clinic local anesthetics, instead of partially, and induces no threshold Na+ currents, we may find a long-acting local anesthetic applicable for clinic use. Using available Aconitum alkaloids, we are now exploring this possibility.

Could Na+ channel isoforms also be the BLA targets for its analgesic effects in vivo?

The use of Aconitum roots and the purified BLA in solution or in tablet, as an analgesic agent for the treatment of chronic pain and rheumatoid arthritis remains common in China. BLA is classified as a non-narcotic analgesic and no physical dependence has been observed in monkeys2. Analgesia mediated by BLA was eliminated by intraperitoneal injection of reserpine 3 hr before BLA and was enhanced by elevation of brain 5-HT or norepinephrine level. These BLA studies suggest that the analgesic effects induced by BLA are modulated by the catecholaminergic and serotoninergic systems in the CNS but the details of BLA actions in analgesia remain unknown2. Our observations on the systemic side effects induced by BLA indicate that BLA has multiple targets at various tissues, including heart, skeletal muscle, PNS and CNS. Since BLA reduces Na+ currents strongly in a use-dependent manner (Fig. 3), it is feasible that various Na+ channel isoforms in CNS and PNS are also potential targets of BLA for its analgesic effects. This notion is consistent with the fact that the analgesic and anesthetic effects of Aconitum alkaloids are strongly correlated3; the stronger the local anesthetic potency of an Aconitum alkaloid, the stronger its analgesic effect in vivo. It is well recognized that ectopic high-frequency discharges from injured nerves likely cause neuropathic pain18. Indeed, i.v. injection of the local anesthetic lidocaine is an option for the treatment of neuropathic pain19. Because BLA reduces neuronal Na+ currents greatly even at low concentrations, it may silence ectopic discharges of injured nerve and provide the analgesic relief in patients with neuropathic pain. Such a possibility deserves further investigations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nathanael Hevelone, MPH, Biostatistician, Center for Surgery and Public Health, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, for his help in statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Financial support was provided by a grant (GM48090 to GKW and S-YW) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Reference List

- 1.Ameri A. The effects of Aconitum alkaloids on the central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;56:211–35. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu D-Y, Bai D-L, Tang X-C. Recent studies on traditional Chinese medicinal plants. Drug Development Research. 1986;39:147–57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bello-Ramirez AM, Nava-Ocampo AA. The local anesthetic activity of Aconitum alkaloids can be explained by their structural properties: a QSAR analysis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2004;18:157–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright SN. Irreversible block of human heart (hH1) sodium channels by the plant alkaloid lappaconitine. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:183–92. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates Inc; 2001. Modification of gating in voltage-sensitive channels; pp. 635–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vega AV, Espinaosa JL, Lopez-Dominguez AM, Lopez-Santiago LF, Navarrete A, Cota G. L-type calcium channel activation up-regulates the mRNAs for two different sodium channel alpha subunits (Nav1.2 and Nav1.3) in rat pituitary GH3 cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;116:115–25. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamill OP, Marty E, Neher ME, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cota G, Armstrong CM. Sodium channel gating in clonal pituitary cells: the inactivation step is not voltage dependent. J Gen Physiol. 1989;94:213–32. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kau YC, Hung YC, Zizza AM, Zurakowski D, Greco WR, Wang GK, Gerner P. Efficacy of lidocaine or bupivacaine combined with ephedrine in rat sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:14–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipsitz SR, Kim K, Zhao L. Analysis of Repeated Categorical Data Using Generalized Estimating Equations. Statistics in Medicine. 1994;13:1149–63. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hille B. Local anesthetics: hydrophilic and hydrophobic pathways for the drug receptor reaction. J Gen Physiol. 1977;69:497–515. doi: 10.1085/jgp.69.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nau C, Wang S-Y, Strichartz GR, Wang GK. Block of human heart hH1 sodium channels by the enantiomers of bupivacaine. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1022–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nau C, Wang GK. Interactions of local anesthetics with voltage-gated Na+ channels. J Membr Biol. 2004;201:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0702-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang S-Y, Wang GK. Voltage-gated sodium channels as primary targets of diverse lipid-soluble neurotoxins. Cell Signal. 2003;15:151–9. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(02)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao S, Sikdar SK. Modification of alpha subunit of RIIA sodium channels by aconitine. Pflugers Arch. 2000;439:349–55. doi: 10.1007/s004249900121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Partridge BL. The effects of local anesthetics and epinephrine on rat sciatic nerve blood flow. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:243–50. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199108000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerner P. Tricyclic antidepressants and their local anesthetic properties: from bench to bedside and back again. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:286–9. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devor M, Seltzer Z. Pathphysiology of damaged nerves in relation to chronic pain. In: Wall PD, Melzack R, editors. Textbook of Pain. 4. New York: Churchill Livingstong; 1999. pp. 129–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boas RA, Covino BG, Shahnarian A. Analgesic responses to I.V. lignocaine. Br J Anaesth. 1982;54:501–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/54.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]