Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To present a primary care approach to evaluating and managing abnormal uterine bleeding.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Literature searches were conducted on MEDLINE from 1996 to November 2004, EMBASE from 1996 to January 2005, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from the 4th quarter of 2004 to the 3rd quarter of 2005, guideline advisory committee databases, the Canadian Medical Association Infobase, and Clinical Evidence. The quality of evidence ranged from level I to III.

MAIN MESSAGE

Premenopausal abnormal uterine bleeding can be ovulatory, anovulatory, or anatomic. A variety of hormonal and nonhormonal treatments are available. Patients’ preferences, side effects, and physicians’ comfort should be considered when making treatment decisions. One in 4 cases of endometrial carcinoma occur in premenopausal women, so it is important to investigate women with risk factors. While postmenopausal bleeding is most commonly caused by atrophic vaginitis, bleeding should be investigated to rule out endometrial and cervical carcinoma.

CONCLUSION

A primary care approach to medical management of abnormal uterine bleeding can help family physicians treat most women in the office as well as help physicians know when to refer women for specialist care.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Proposer une méthode adaptée aux soins primaires pour évaluer et traiter les saignements utérins anormaux.

SOURCES DE L’INFORMATION

On a consulté MEDLINE entre 1996 et novembre 2004, EMBASE entre 1996 et janvier 2005, la Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews entre le 4e trimestre de 2004 et le 3e trimestre de 2005, des bases de données de comités consultatifs pour les directives de pratique, l’Infobasede l’Association médicale canadienne et Clinical Evidence. Les niveaux de preuves variaient entre I et III.

MESSAGE PRINCIPAL

Les saignements utérins anormaux peuvent être ovulatoires, anovulatoires ou anatomiques. Plusieurs traitements hormonaux ou non hormonaux sont disponibles. Le choix du traitement doit tenir compte des préférences de la patiente, des effets indésirables et des habitudes du médecin. Un quart des carcinomes endométriaux survient chez des femmes préménopausiques et il est donc important d’examiner celles qui présentent des facteurs de risque. Même si la plupart des saignements postménopausiques sont causés par la vaginite atrophique, ils méritent quand même d’être examinés pour éliminer un carcinome endométrial ou cervical.

CONCLUSION

Une méthode de traitement des saignements utérins anormaux adaptée aux soins primaires devrait aider le médecin de famille à traiter la plupart des femmes au bureau et lui permettre de savoir quand adresser la patiente en spécialité.

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is the main reason women are referred to gynecologists and accounts for two thirds of all hysterectomies.1 In premenopausal women, AUB is diagnosed when there is a substantial change in frequency, duration, or amount of bleeding during or between periods.2 In postmenopausal women, any vaginal bleeding 1 year after cessation of menses is considered abnormal and requires evaluation.3

Patients usually present first to their family physicians, who can do most of the diagnostic workup and management. Specialist care is sought when first-line medical treatments have failed or specialized testing is required. An approach to diagnosis and management of AUB in women of all ages is, therefore, important for family physicians. This article reviews and integrates the most recent evidence, Canadian and international practice guidelines, expert opinion, and clinical experience for the common causes of AUB and current medical and surgical treatment for it.

Case 1

Ms G. is a 26-year-old new patient in your practice who presents with a long-standing history of regular, heavy periods. She feels otherwise well, but the extent of her bleeding is worrying her. Review of systems is unremarkable, and results of physical examination, including pelvic examination, are normal.

Case 2

Mrs H., a 43-year-old woman with 3 children, comes to see you regarding her heavy periods. Over the years they have become heavier. She states that she “floods” the first few days and often has to stay home from work. She is chronically tired. On examination, she is pale, and her uterus is about the size it would be at 14 weeks’ gestation.

Case 3

Mrs S., a 61-year-old woman, has come to see you regarding several episodes of spotting. She has been postmenopausal for the past 12 years and has never taken hormone replacement therapy. She feels otherwise well. Her medications include 81 mg of acetylsalicylic acid, 5 mg of amlodipine, 10 mg of atorvastatin, and 37.5 mg of venlafaxine twice daily. Her physical examination is unremarkable.

Sources of information

MEDLINE was searched from 1996 to November 2004, EMBASE from 1996 to January 2005, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) from the 4th quarter of 2004 to the 3rd quarter of 2005. The Guideline Advisory Committee (GAC) database, the Canadian Medical Association Infobase for guidelines, and Clinical Evidence were also searched. Search terms used were the MeSH words uterine hemorrhage and menorrhagia for MEDLINE; the EMTREE subject headings uterus bleeding, menorrhagia, hypermenorrhea, and metrorrhagia for EMBASE; and menorrhagia as well as uterus or uterine or menstrual combined with bleeding or hemorrhage and abnormal or dysfunctional for the CDSR. Searches were limited to review articles involving human, female subjects. The quality of evidence ranged from level I to III.

Evaluation of AUB in premenopausal and perimenopausal women

The cause of AUB in premenopausal women is found in 50% to 60% of cases.1 The remaining cases, where no organic cause is found, are classified as dysfunctional uterine bleeding.2

History focuses on identifying the type of AUB—ovulatory, anovulatory, or anatomic—in order to guide treatment (Table 1). Ovulatory bleeding is more common, usually cyclic, and can be associated with midcycle pain, premenstrual symptoms, and dysmenorrhea.4 Anovulatory bleeding occurs more frequently at the extremes of reproductive age and in obese women. It is usually irregular and often heavy.5 Anovulatory bleeding poses a higher risk of endometrial hyperplasia.2 Polycystic ovarian syndrome is a common cause of anovulatory bleeding and is not discussed here. Fibroids or polyps are the most common cause of anatomic AUB2; 20% to 40% of women have fibroids.6 These women might present with abnormal bleeding, anemia, pain, and occasionally infertility. Some medications can also cause AUB (Table 27).

Table 1.

Classification of menorrhagia

| UNDERLYING CAUSE | CHARACTERISTICS | TREATMENTS |

|---|---|---|

| Ovulatory | Cyclical, might be associated with premenstrual symptoms or dysmenorrhea | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Antifibrinolytics COCPs Endometrial ablation Hysterectomy |

| Anovulatory | Irregular bleeding, often heavy

More common in adolescents and perimenopausal women Higher risk of endometrial hyperplasia |

COCPs

LNG-IUS Cyclic progestins Androgens Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists Endometrial ablation Hysterectomy |

| Anatomic | Caused by fibroids, polyps, or adenomyosis

Often heavy bleeding, pain Uterus might be enlarged |

COCPs

Antifibrinolytics LNG-IUS Androgens Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists Uterine fibroid embolization Myomectomy Hysterectomy |

COCPs—combined oral contraceptive pills, LNG-IUS—levonorgestrel intra-uterine system.

Table 2.

Medications that can cause abnormal uterine bleeding

| Anticoagulants |

| Acetylsalicylic acid |

| Antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants) |

| Hormone replacement therapy |

| Tamoxifen |

| Phenothiazines |

| Corticosteroids |

| Thyroxine |

| Contraceptives |

| Herbs: ginseng, ginkgo, soy products |

Adapted from Albers et al.7

Physical examination includes looking for evidence of systemic disease. Pelvic and bimanual examinations are done to detect disease in the genital tract. Cervical cytology analysis should be current and normal, and cervical and vaginal swabs should be assessed to rule out infection.

Investigations

Investigations can include pregnancy testing if indicated and a complete blood count with ferritin. Other investigations might be done on the basis of clinical suspicion (Table 3). Coagulopathy should be ruled out when menorrhagia occurs at the start of menarche and there is no obvious pelvic disease. Von Willebrand disease is the most common coagulation disorder causing menorrhagia.8

Table 3.

Further investigations based on clinical suspicion

| SYSTEMIC CAUSES | INITIAL INVESTIGATIONS |

|---|---|

| Thyroid disease (hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism) | Sensitive thryroid-stimulating hormone test |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | Free testosterone, DHEAS, luteinizing hormone: follicle-stimulating hormone>3:1 |

| Coagulopathies, leukemia, thrombocytopenia | Complete blood count, INR, partial thromboplastin time, bleeding time |

| Pituitary adenoma or hyperprolactinemia | Fasting prolactin |

| Hypothalamic suppression due to stress, weight loss, excessive exercise, eating disorder | Measure weight |

| Hepatic disease | Liver function tests, INR |

| Renal disease | Creatinine |

| Adrenal hyperplasia | DHEAS, free testosterone |

| Cushing disease | 24-hour urine free cortisol, overnight dexamethasone suppression test |

DHEAS—dehydroepiandrosterone, INR—international normalized ratio.

Further investigations include ultrasonography to look for ovarian or uterine disease and endometrial biopsy. Transvaginal ultrasound is 80% sensitive and 69% specific for fibroids and polyps and is superior to transabdominal ultrasound.2 If possible, transvaginal ultrasound should be performed on days 4 to 6 of the menstrual cycle.9 In premenopausal women, there is no known correlation between endometrial thickness seen on ultrasound scan and endometrial disease.2

Endometrial biopsy is a simple office procedure that can be done by family physicians. The annual incidence of endometrial cancer is 19.5 per 100 000 women.10 Table 42 lists risk factors for endometrial cancer.2 One in 4 cases of endometrial carcinoma occurs before menopause, so biopsy should be considered for high-risk premenopausal patients10 (level II evidence, grade B recommendation), even in the presence of fibroids. Endometrial biopsy produces an adequate sample more than 85% of the time and detects 87% to 96% of endometrial carcinoma.2

Table 4.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer

| Age >40 |

| Weight ≥90 kg (200 lbs) |

| Anovulatory cycles |

| Nulliparity |

| Infertility |

| Tamoxifen use |

| Family history of endometrial or colon cancer |

Adapted from Vilos et al.2

Specialist diagnostic procedures

Specialist diagnostic procedures for anatomic changes and for endometrial carcinoma include diagnostic hysteroscopy, sonohysterogram, and dilation and curettage (D&C). A D&C does not sample the entire endometrium and can miss up to 10% of disease.11 Due to its associated operative risks, D&C is falling out of favour.12 Hysteroscopy allows direct visualization of the endometrial cavity and is usually combined with endometrial biopsy. Saline sonohysterogram involves introducing 5 to 15 mL of saline solution into the uterine cavity followed by a transvaginal ultrasound scan that might help diagnose an intrauterine mass.2

In premenopausal women with no obvious cause of AUB, the need for further investigations is controversial. If women have only normal variations in their menstrual cycles, reassurance is all that is required. For instance, following times of stress, abnormal menstrual cycles often revert to normal after a few months. Our clinical experience also shows that cycles can change normally with age, use of contraceptives, and after pregnancy. If physicians are concerned about fibroids or polyps, endometrial hyperplasia, or carcinoma, further workup and treatment are important.

Evaluation of AUB in perimenopausal women is challenging. As a result of the decline in ovarian function, changes in menstrual cycles are common in these women.13 As with postmenopausal bleeding, abnormal perimenopausal bleeding is associated with endometrial carcinoma in approximately 10% of cases,10 so evaluation of women’s risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma is recommended (Table 42). According to guidelines,2,11 all perimenopausal women with irregular bleeding warrant further investigation. It is important to note, however, that the highest risk of endometrial carcinoma is among women who weigh ≥90 kg and who are 45 years or older.10

Treatment for premenopausal and perimenopausal women

A patient’s degree of menorrhagia, associated pain, desire for pregnancy, concurrent medical conditions, and treatment side effects, and her physician’s comfort level should be taken into account when deciding on management2 (Table 514,15). Menorrhagia associated with ovulatory cycles can be treated with or without hormones. The anti-inflammatory medications mefenamic acid and naproxen have been studied most extensively and are equally effective at reducing menorrhagia.16 If started on day 1 of the menstrual cycle and continued for 5 days or until menses stop, these drugs can reduce bleeding by 22% to 46%12 (level I evidence). Antifibrinolytics are effective and underused. In the past, concern about increased risk of thrombosis limited use of these medications, but a recent Cochrane review showed no higher rate of thrombosis when compared with placebo or other therapies.17 For example, tranexamic acid has been shown to reduce menstrual blood loss by 34% to 59% over 2 to 3 cycles.18

Table 5.

Medical therapy for abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal and perimenopausal women

| MEDICATION | ACTION |

|---|---|

NSAIDs

|

Inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, might also alleviate menstrual pain

No evidence of difference in clinical efficacy of individual NSAIDs |

| Antifibrinolytics:

Tranexamic acid (500 mg-1000 mg every 6–8 h as required |

Counteract increased fibrinolytic activity, significantly reduce mean blood loss compared with placebo, NSAIDs (mefenamic acid), and oral luteal phase progestins (level I evidence) |

| Combined oral contraceptives | Useful for anovulatory bleeding, might have benefit for ovulatory bleeding (although lack of good-quality data) |

Progestins

|

Stabilizes endometrium

T-shaped intrauterine device releases a steady amount of levonorgestrel (20 μg/24 h), low level of circulating hormone minimizes systemic side effects, training in insertion is advised |

| Androgens:

Danazol (200 mg once daily) |

Inhibits steroidogenesis in ovaries

Side effects: androgenic (weight gain, acne, irritability, headaches, hirsutism, clitoromegaly, decreased breast size), lipid changes, liver disease, muscle cramps, breakthrough bleeding, gastrointestinal distress |

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

|

Induce a reversible hypoestrogenic state

Side effects: androgenic (see above), menopausal symptoms in 80%–90% of women (hot flashes, vaginal dryness, etc), irregular bleeding. Add-back therapy (cyclic estrogen and progestin similar to hormone replacement therapy) can minimize side effects |

Anovulatory menorrhagia might require endometrial protection with a combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP), the levonorgestrel intra-uterine system (LNG-IUS), or cyclic oral progestins. The LNG-IUS is a relatively new treatment that remains effective for 5 years. It has been found to reduce menstrual blood loss by 74% to 97%,18 and many women will be amenorrheic by 12 months.15 It is licensed in Canada for contraception only; using it for menorrhagia is an “off label” indication.

Asymptomatic fibroids do not require treatment.6 Menorrhagia caused by fibroids can be treated with tranexamic acid, low-dose COCPs, androgens, or GnRH agonists.6 There is no evidence for using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hormone replacement therapy, or oral progestins.6 Women who have acute heavy bleeding and are hemodynamically stable can be treated with low-dose progestin-dominant oral contraceptives at a dose of 2 to 4 pills a day for 7 days and then 1 pill a day for 2 weeks.15

Most family physicians refer patients for specialist care for AUB when treatment with androgens or gonadotropin-reducing hormone (GnRH) agonists is sought, but it is important to be aware of these options to discuss with patients. Androgens can reduce menstrual blood loss by up to 80%,12 but should be limited to 6 months due to androgenic side effects. The GnRH agonists also decrease menstrual blood loss, but the decrease in bone mineral density limits their use to 6 months.

Evaluation and treatment of AUB in postmenopausal women

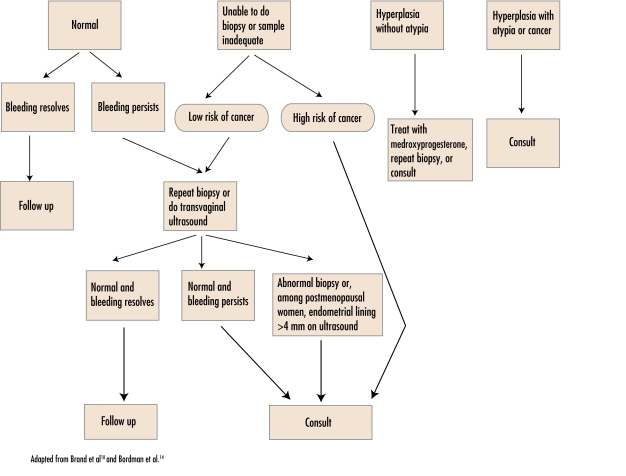

Postmenopausal women presenting with vaginal bleeding must be evaluated. The most common cause of postmenopausal bleeding is vaginal atrophy (59%).9 It is important, however, to rule out endometrial carcinoma (10%) and cervical carcinoma (2%)10 (Table 619). Initial investigation of the endometrium is controversial. Endometrial biopsy, transvaginal ultrasound, or both can be done. What is done could depend on patient preference, physician comfort, and the availability of ultrasound scanning. The exact thickness of a normal endometrial lining in postmenopausal women as measured by ultrasound is also controversial. Several large studies have used 4 mm as the cutoff for further investigations (sensitivity 96% to 98%, specificity 36% to 68%).10 Figure 110,14 outlines management based on the results of endometrial biopsy.

Figure 1.

Management of patients based on results of endometrial biopsy

Medical therapy for atrophic vaginitis

Atrophic vaginitis can be treated with topical estrogen cream (Premarin®), the newer tablets (Vagifem®), or a vaginal ring (Estring®); lubricants (Astroglide®, Lubrin®, or K-Y®); or moisturizers (Replens®) (level I evidence, grade B recommendation).20

Surgical options for menorrhagia

Dilation and curettage is no longer considered a treatment for menorrhagia because there is no long-term benefit (level II evidence). In fact, menstrual blood losses return to previous or higher levels by the second menstrual period following the procedure.15 Endometrial ablation is achieved by a variety of mechanisms, such as laser, electrical, thermal, or radiofrequency energy. It is done as an outpatient procedure under general anesthetic. About 85% of women have fewer symptoms, 10% require repeat ablation, and about 10% proceed to hysterectomy.1,11 Women older than 40 have been found to have better outcomes than those younger than 40.18 The procedure is not recommended for women wanting to preserve fertility. Hysterectomy is a permanent cure for menorrhagia, but the risks of major surgery must be weighed against risks of alternative management. In properly selected patients, hysterectomy might be the best choice.4 Hysterectomy is the recommended treatment for endometrial carcinoma. Uterine artery embolization and myomectomy are additional options for treating fibroids. Uterine artery embolization is a relatively new procedure. It resolves menorrhagia and pressure symptoms in 80% to 90% of cases,21 but there are risks associated with the procedure, and as of yet, no long-term data on its effectiveness.21 Myomectomy removes fibroids and conserves the uterus, but is appropriate only for certain types of fibroids. Although 80% of women see their symptoms improve,15 myomectomy might affect their ability to have vaginal deliveries.6 Postoperative recovery time is similar to that of hysterectomy.

Case 1 resolution

Ms G.’s situation represents either normal menstruation or ovulatory menorrhagia. Complete blood count and ferritin could be done, and transvaginal ultrasound to assess for fibroids could be considered. She could try nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during menstruation, or if she wants birth control, COCPs.

Case 2 resolution

An ultrasound scan of Mrs H. revealed 2 large fibroids. Due to her age, she underwent an endometrial biopsy9; results were negative. Her hemoglobin was 106 g/L and ferritin 7 mmol/L. She was started on iron replacement, as well as tranexamic acid. If these did not work, or the side effects were intolerable, she could be offered LNG-IUS, androgens, GnRH agonists, or surgery.

Case 3 resolution

Mrs S. had an endometrial biopsy; results were negative. She did not want estrogen cream and opted for a trial of lubricant applied daily. She continued to have spotting a few months later, and a transvaginal ultrasound was ordered. Results of this, as well as of a repeat endometrial biopsy were normal so she was referred to a gynecologist for further evaluation. If results of further investigations are negative, a review of her medications and a trial of discontinuation might be warranted.

Conclusion

Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common reason for women to present to their family physicians. Family physicians can often manage AUB in the office and refer patients to gynecologists only if the first steps of management are ineffective or if more specialized investigations are needed. Endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma can be diagnosed by family physicians with endometrial biopsy. A stepwise evidence-based approach to managing AUB is recommended.

LEVELS OF EVIDENCE

Level I: Evidence from at least one properly conducted randomized controlled trial

Level II-1: Evidence from well designed controlled trials without randomization

Level II-2: Evidence from well designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than 1 centre or research group

Level II-3: Evidence from comparisons between times or places with or without the intervention

Level III: Opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees

GRADES FOR RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SPECIFIC CLINICAL ACTIONS

Grade A: Good evidence to recommend the clinical action

Grade B: Fair evidence to recommend the clinical action

Grade C: Existing evidence conflicts and does not allow making a recommendation for or against taking the clinical action; however, other factors might influence decision making

Grade D: Fair evidence to recommend against the clinical action

Grade E: Good evidence to recommend against the clinical action

Grade I: Insufficient evidence to make a recommendation; however, other factors might influence decision making

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Abnormal uterine bleeding is fairly common among women presenting to their family doctors and is the most common reason for referral to gynecologists. Most cases, however, can be managed by family doctors.

History should focus on the type of abnormal bleeding: ovulatory, anovulatory, or anatomic. The rest of the investigation should be guided by this classification and can include ultrasound (transvaginal) scans and endometrial biopsy, a simple office procedure.

Treatment for premenopausal and perimenopausal bleeding includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antifibrinolytics, combined oral contraceptives, progestins, androgens, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.

In postmenopausal women, 60% of abnormal bleeding is due to atrophic vaginitis, but 10% is caused by endometrial cancer, which justifies a proper workup with transvaginal ultrasound scans or endometrial biopsy, or both.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Les saignements utérins anormaux sont relativement fréquents chez les femmes qui consultent leur médecin de famille et c’est la raison principale des demandes de consultation en gynécologie. Toutefois, la plupart des cas peuvent être traités par le médecin de famille.

L’histoire devrait chercher à définir le type de saignement anormal: ovulatoire, anovulatoire ou anatomique. Cette classification orientera le reste de l’analyse, lequel pourra inclure une échographie (intravaginale) et une biopsie endométriale, une technique simple à utiliser au bureau.

Le traitement des saignements pré- et périménopausiques inclut les anti-inflammatoires non stéroïdiens, les antifibrinolytiques, les contraceptifs oraux combinés, les progestatifs, les androgènes et les agonistes de la gonadolibérine.

Après la ménopause, 60% des saignements anor-maux sont dus à la vaginite atrophique tandis que 10% proviennent d’un cancer endométrial, ce qui justifie une analyse adéquate par échographie intra-vaginale, biopsie endométriale ou les deux.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.O’Connor VM. Heavy menstrual loss. Part 1: Is it really heavy loss? Med Today. 2003;4(4):51–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vilos GA, Lefebvre G, Graves GR. Guidelines for the management of abnormal uterine bleeding. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2001;23(8):704–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase NG. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 6. Baltimore, Md: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Fentiman G, Lethaby A, Rademaker L. An evidence-based guideline for the management of uterine fibroids. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;41(2):125–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2001.tb01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid RL, Lee JY. Medical management of menorrhagia. Informed. 1995;1(4):6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefebvre G, Vilos G, Allaire C, Jeffrey J. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2003;128:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albers JR, Hull SK, Wesley RM. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(8):1915–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demers C, Derzko C, Michele D, Douglas J. Gynaecological and obstetric management of women with inherited bleeding disorders. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2005;163:707–18. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Clinical management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Educational series on women’s health issues. Crofton, Md: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2002. [Accessed 2006 November 8.]. Available at: http://www.apgo.org/elearn/modules.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brand A, Dubuc-Lissoir J, Ehlen Y, Plante M. Diagnosis of endometrial cancer in women with abnormal vaginal bleeding. SOGC Clin Pract Guidelines. 2000;8:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology. National evidence-based guidelines. The management of menorrhagia in secondary care. London, Engl: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecology; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oehler MK, Rees MC. Menorrhagia: an update. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(5):405–22. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derzko CM. Perimenopausal dysfunctional uterine bleeding: physiology and management. Ottawa, Ont: Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordman R, Telner D, Jackson B, Little D. An approach to the diagnosis and management of benign uterine conditions in primary care. Toronto, Ont: Centre for Effective Practice, Ontario College of Family Physicians; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacGibbon L, Jakubovicz D. Educational module: menorrhagia. Found Med Pract Educ. 2005;13(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lethaby A, Augood C, Duckitt K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000400. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lethaby A, Farquhar C, Cooke I. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;4:CD000249. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wellington K, Wagstaff AJ. Tranexemic acid: a review of its use in the management of menorrhagia. Drugs. 2003;63(13):1417–33. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363130-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson B, Granberg S, Wikland M, Ylostalo P, Torvid K, Marsal K, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound of the endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a Nordic multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(5):1488–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston S, Farrell S, Bouchard C, Farrell SA, Beckerson LA, Comeau M, et al. The detection and management of vaginal atrophy. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2004;26(5):503–15. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre G, Vilos G, Asch M. Uterine fibroid embolization. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2004;150:899–911. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]