Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine why students switch their career choices during the preclinical years of medical school.

DESIGN

Two questionnaires were administered: the first at the beginning of medical school and the second about 3 years later just before students entered clinical clerkship.

SETTING

University of British Columbia, University of Alberta, University of Toronto, University of Ottawa, Queen’s University, University of Western Ontario, University of Calgary, and McMaster University.

PARTICIPANTS

Entering cohorts from 10 medical school classes at 8 Canadian medical schools.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Proportion of students who switched career choices and factors that influenced students to switch.

RESULTS

Among the 845 eligible respondents to the second survey, 19.6% (166 students) had switched between categories of family medicine and specialties, with a net increase of 1.2% (10 students) to family medicine. Most students who switched career choices had already considered their new careers as options when they entered medical school. Seven factors influenced switching career choices; 6 of these (medical lifestyle, encouragement, positive clinical exposure, economics or politics, competence or skills, and ease of residency entry) had significantly different effects on students who switched to family medicine than on students who switched out of family medicine. The seventh factor was discouragement by a physician.

CONCLUSION

Seven factors appear to affect students who switch careers. Two of these factors, economics or politics and ease of residency entry, have not been previously described in the literature. This study provides specific information on why students change their minds about careers before they get to the clinical years of medical training.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Déterminer pourquoi les étudiants en médecine modifient leur choix de carrière durant les années précliniques.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Deux questionnaires ont été distribués, le premier au début du cours de médecine et le second environ 3 ans plus tard, juste avant le début des stages cliniques.

CONTEXTE

Les universités de Calgary, d’Ottawa, de Toronto, de Colombie-Britannique, d’Alberta, de Western Ontario et les universités Queen’s et McMaster.

PARTICIPANTS

Les cohortes entrantes de 10 classes de 8 facultés de médecine canadiennes.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES ÉTUDIÉS

Proportion des étudiants ayant modifié leur choix de carrière et facteurs ayant influencé ce changement.

RÉSULTATS

Parmi les 845 participants admissibles qui ont répondu ausecond questionnaire, 165 (19,6%) avaient modifié leur choix entre la médecine familiale et les spécialités, avec une nette augmentation de 10 étudiants (1,2%) vers la médecine familiale. Pour la plupart des étudiants qui ont changé d’option, ce nouveau choix avait déjà été envisagé comme option à leur entrée en médecine. Sept facteurs ont influencé les changements; 6 d’entre eux (type de vie médicale, encouragements, exposition clinique favorable, facteurs économiques ou politiques, habiletés ou compétences particulières et facilité d’obtention d’un poste de résidence) agissaient de façon significativement différente chez ceux qui avaient changé pour la médecine familiale vs une spécialité. Le 7efacteur était l’avis dissuasif d’un médecin.

CONCLUSION

Sept facteurs semblent influencer les étudiants qui modifient leur choix de carrière. Deux d’entre eux (facteurs économiques ou politiques et facilité d’obtention d’un poste de résidence) n’ont pas été décrits dans la littérature existante. Cette étude apporte des informations spécifiques sur les raisons pour lesquelles les étudiants changent d’idée sur leur carrière future avant d’entreprendre les années de formation clinique.

In North America, the number of medical students choosing family medicine as a career is steadily declining. The proportion of students choosing residency in family medicine has fallen in Canada from a high in the early 1990s of 44% to only 25% in the Canadian Residency Match in 2003, the lowest percentage ever.1 In the United States, the proportion of students matching to careers in family medicine has fallen from a high of 72.6% in 1996 to 40.7% in 2005, the lowest percentage ever.2

Several factors have been identified as being associated with students’ choosing generalist careers. Premedical factors include stated career preference on entry to medical school and several demographic factors.3–10 Some specific medical school factors also mediate or alter early career preferences; these factors range from the amount of time devoted to family medicine in the curriculum to the effects of role models.9,11–23

Many of these studies on premedical and medical school factors associated with career choice have been criticized for being biased and having design weaknesses and inconsistencies in both dependent and independent variables.14 Many were carried out in the 1990s before the recent decline in interest in family medicine. As well, the groups studied were in the United States where the definition of primary care is different from the definition in many other nations.22

The literature indicates that students enter medical school with a preference for primary care careers, but this preference changes over time.24–26 Much work has been done on the role of clinical experiences in career choice, but little attention has been paid to the influence of the preclinical years on career choice.

This study aimed to determine the demographic and student-identified reasons for switching career preferences during the preclinical years of medical school.

METHODS

Setting

The University of British Columbia, University of Alberta, University of Toronto, University of Ottawa, Queen’s University, and the University of Western Ontario have 4-year preclinical programs. The University of Calgary and McMaster University have 3-year preclinical programs.

Subjects

Students beginning their studies in 10 medical school classes at the 8 universities participated. International students were excluded from the study.

Procedure

On entry, students were asked to fill out questionnaires (described elsewhere27) ranking their top 3 career choices. At the end of the preclinical years, all eligible students who had responded to the initial questionnaire were presented with a sealed envelope that contained a list of their top 3 career choices as reported on the entry survey. If their career choices had changed, students were asked to provide their current top 3 choices from a list of 8 options: emergency, family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, surgery, and other.

Questionnaire

The second questionnaire was a unique 47-item validated instrument. It asked students to rank their top 3 career choices, to give demographic information, and to answer 32 5-point Likert-type questions examining the influence of medical school experiences on career choices. Two questions were repeated to assess the reliability of the questionnaire. Most of the Likert-type questions were derived from a literature review and discussions with medical students, residents, and educational leaders and were different from the questions on the entry survey. Both surveys were subjected to a validation process described by Lynn28 to assess appropriateness and comprehensiveness (face and content validity) and were pilot-tested on medical students at more than 1 school. For this study we used the top career choices from both the entry and the follow-up surveys to identify changes in career preferences, then assessed the reasons for career changes from the items on the follow-up survey.

Data analysis

Factor analysis was used to determine whether the 30 items influencing change in career choice could be grouped to create a smaller number of influential factors. Twenty-nine of the items clustered into 7 factors: medical lifestyle, encouragement by a physician, discouragement by a physician or negative clinical exposures, economics or politics, competence or skills, positive clinical exposures, and ease of entry into program, with an eigenvalue > 1 and a minimum factor loading of 0.4. The mean value of Likert-type items for each factor was calculated for individual students. Means ranged from 1 (no influence) to 5 (major influence). Independent sample t tests were then carried out to assess differences between students switching to family medicine and students switching to specialties for each of the 7 factors. Results were considered significant if P < .05.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 11.5. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the research ethics boards of the participating universities.

RESULTS

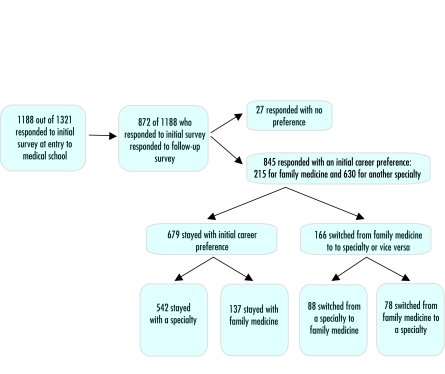

In September 2001, 2002, or 2003, 1188 (89.9%) of 1321 eligible students completed the entry questionnaire and listed their top 3 career choices. About 2 years later, on completion of their preclinical training, 872 of the 1188 students who had responded to the initial survey responded to the follow-up questionnaire for a response rate of 73.4%. Of these 872 respondents, 27 failed to indicate career preferences on one or both surveys, leaving 845 responses for analysis.

About 58.6% of these 845 students were female. Ages ranged from 18 years to 49 years, with a mean age of 23.9 years. Most (71.7%) of the students were single. Nearly all (92.9%) of the 830 students listing their undergraduate training held Bachelor of Science or similar degrees. Most students (76.3%) reported that their most educated parent had a university degree.

There were no statistically significant differences in sex or relationship status between students staying in family medicine and students switching to or from family medicine. Students staying in family medicine were significantly older than students switching to (P = .001) or from (P = .007) family medicine.

About 19.6% (166 students) changed their top career choices to a specialty or to family medicine (Figure 1); 88 switched to family medicine, and 78 switched to a specialty, for a net increase of 10 students to family medicine. Of the remaining 679 students who did not change their career choices, 542 maintained an interest in 1 of several specialty careers, and 137 maintained an interest in family medicine.

Figure 1.

Flow of students

At medical school entry, 215 (25.4%) of the 845 students who answered both entry and follow-up questionnaires listed family medicine as their first career choice. This number rose to 225 (26.6%) at the end of the pre-clinical years. Of the 88 students who named specialties as their preferred careers at entry but changed these preferences to family medicine at follow-up, 68 (77.3%) had named family medicine as either a second or third choice on entry. Of the 78 students who named family medicine as their first choice of career on entry but changed preferences to a specialty at follow-up appointments, 40 (51.3%) had named that specialty as either a second or third choice on entry.

Factor analysis demonstrated that all but 1 of the 30 questionnaire items influencing change in career preferences could be grouped into 7 factors (Table 1). Students switching to family medicine rated the importance of 6 of these 7 factors differently from those switching to specialties (Table 2). The influence of both medical lifestyle and ease of residency entry were rated higher by students who switched to family medicine than by those who switched to specialties (P < .0005). The influence of economics or politics (P < .0005), competence or skills (P < .0005), positive clinical exposure (P = .001), and encouragement (P = .031) was rated higher by students who switched to specialties than by those who switched to family medicine. The relative importance of a factor to a student choosing to switch careers can be inferred from the mean Likert score reported.

Table 1.

Factors influencing changes in career preferences

Medical lifestyle

|

Encouragement by physician

|

Discouragement by physician or negative clinical exposure

|

Economics or politics

|

Competence or skill

|

Positive clinical exposure

|

Ease of residency entry

|

Table 2.

Reasons for change in career preference: 78 students switched from family medicine to specialties, and 88 students switched from specialties to family medicine. Means for each factor are calculated from students’ responses to Likert-scale items: 1—no influence, 3—moderate influence, 5—major influence.

| FACTOR | SWITCHING TO OR FROM FAMILY MEDICINE (FM) | MEAN (STANDARD DEVIATION) | T | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical lifestyle | From FM | 2.21 (.88) | −8.34 | <.0005 |

| To FM | 3.35 (.89) | |||

| Encouragement by physician | From FM | 2.69 (1.10) | 2.17 | .031 |

| To FM | 2.32 (1.09) | |||

| Discouragement by a physician or negative clinical exposure | From FM | 1.77 (.72) | 0.92 | .363 |

| To FM | 1.67 (.68) | |||

| Economics or politics | From FM | 1.94 (.82) | 6 | <.0005 |

| To FM | 1.32 (.43) | |||

| Competence or skills | From FM | 2.34 (.87) | 5.05 | <.0005 |

| To FM | 1.74 (.63) | |||

| Positive clinical exposure | From FM | 3.50 (1.11) | 3.55 | .001 |

| To FM | 2.88 (1.16) | |||

| Ease of residency entry | From FM | 1.26 (.53) | −5.47 | <.0005 |

| To FM | 1.82 (.80) |

DISCUSSION

Students come to medical school with careers in mind or have personal characteristics that predict their career choices.3 The stability of these choices, however, is unclear. Some investigators have found that only 20% of students enter the exact specialty they planned at entry to medical school.29 Others have found that career preferences at entry can substantially affect eventual career choice,30 particularly for those whose initial career interests are in primary care specialties (family medicine, pediatrics, and internal medicine).22,30–32

Results of this study were consistent with these findings of broad career stability. Only 19.6% of students changed their top career choices (broadly defined as a specialty career or a family medicine career) at the end of their preclinical years. While many studies show a trend toward waning interest in primary care among medical students,4,25,26,33 our study showed little change in interest in family medicine during the preclinical years (1% increase).

This study found that students who switch careers during their preclinical years identify 7 factors that influence them to change their careers: medical lifestyle, encouragement, positive clinical exposure, discouragement or negative clinical exposure, economics or politics, competence or skills, and ease of residency entry. All except encouragement and discouragement or negative clinical exposure showed a difference of >.5 points on a 5-point Likert scale between those switching to family medicine and those switching from it (Table 2). Medical educators should focus on these factors when helping students make career choices during the pre-clinical years.

Various factors were identified as being the most important influences on change in career preference. Medical lifestyle was the most important factor for those switching to family medicine and positive clinical exposure was the most important factor for those switching to specialties. It is heartening that “lifestyle” is not associated with negative perceptions of a career in family medicine; items in the factor “lifestyle” ranged from happy residents and more flexibility to a shorter residency and changing family and location needs. It should be encouraging to medical educators that students did not identify discouragement by teachers and negative clinical exposure as important influences on career changes.

It appears that even during the preclinical years students are greatly influenced by clinical experiences. This might have implications for how schools structure clinical experiences during the preclinical years. Those interested in promoting family medicine as a career or those concerned with how students make career choices need to recognize that different factors appear to affect students switching to and from family medicine.

Although it is a relatively small influence on career switching, students switching to specialties viewed the factor “economics or politics” as significantly more important than those switching to family medicine did. This should concern family medicine educators. This study highlights the perceived negative effects of health care reform, perceived potential future income, and a possible inability to change residencies as important factors in changing career choices from family medicine to a specialty in the preclinical years. The fact that students who participated in this study were from Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta, where health care reform is currently under way, might indicate that some of the intended positive aspects of primary health care reform are not interpreted as such by students. The effect of economics or politics on career switching to a specialty has not been described elsewhere.

Although it also has a relatively low influence on career switching, the factor “ease of residency entry” was viewed as significantly more important by students switching to family medicine and should, therefore, be of concern to family medicine educators. This study suggests that the availability of family medicine residency positions might entice students who think they will have difficulty being accepted into other residencies to pursue careers in family medicine. The influence of ease of residency entry on career switching to family medicine has not been described elsewhere.

Given that most medical students who switch their career choices from family medicine to specialties have considered their new careers at medical school entry, we would recommend that governments, the profession, and undergraduate medical educators provide balanced, unbiased information to students in an effort to allow them to make more informed career decisions during both preclinical and clinical training.

Strengths of the study

This study used a prospective cohort, allowing us to identify influences and preference changes that occurred during a specific period. This design avoids potential bias in student recall and provides insight into the genesis and importance of relevant variables. The questionnaire used in this study was validated and pilot-tested. The study had a high response rate and involved more than 1 medical school, which should improve its generalizability to other settings. Although not mentioned in this paper, qualitative data from focus groups on why students switch careers are available and can provide further context for our findings. We plan to monitor these students to the end of medical school to assess the effect of both the preclinical and clinical years on students’ ultimate career choices.

Limitations

Greater inferences could have been drawn if the sample size had been larger. These would include the effect of various school curriculums on the factors leading to career change and the ability to examine factors associated with specific specialties.

Conclusion

Most students stay with the career choice (specialty or family medicine) they made at medical school entry through to the end of the preclinical years. Students who switch careers are very likely to have considered the new career at entry, indicating that they enter with a range of possible careers in mind before they start their medical education. We identified factors that influence students to change their career choices during the preclinical years: medical lifestyle, encouragement, positive clinical exposure, negative clinical exposure, economics or politics, competence or skills, and ease of residency entry.

Acknowledgment

We thank the students who gave their time and insight to this study and our colleagues at the participating medical schools for their hard work distributing and collecting surveys. We also thank Gina Ogilvie and Leah Douglas for their skilled assistance with editing and Marika Dauberman and Jill Carney for their assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

This study examined why medical students changed their career plans (to family medicine or to a specialty) during their preclinical years.

More than 80% maintained their initial career preferences. Of those who switched, slightly more students changed from a specialty to family medicine than the reverse.

Medical lifestyle was the most important factor for those switching to family medicine. Positive clinical exposure was the most important factor for those switching to a specialty.

This study will continue until the end of clinical training. It will be interesting to see how clinical training affects students’ final career choices.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Cette étude avait pour but de connaître les raisons qui font que des étudiants en médecine modifient leur choix de carrière (vers la médecine familiale ou vers une spécialité) durant leurs années précliniques.

Plus de 80% ont maintenu leur choix de carrière initial. Parmi les étudiants qui ont changé, ceux qui sont passés d’une spécialité vers la médecine familiale étaient un peu plus nombreux que ceux qui ont fait le choix inverse.

Pour ceux qui ont changé en faveur de la médecine familiale, le facteur le plus important était le type de vie médicale alors que pour ceux qui ont changé en faveur d’une spécialité, c’était une exposition clinique favorable.

Cette étude doit se poursuivre jusqu’à la fin de la formation clinique. Il sera intéressant de voir de quelle façon les stages cliniques influenceront le choix de carrière final des étudiants.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors

Drs Scott, Wright, and Branneis, and Ms Gowans conceived and designed the study, gathered and analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Canadian Resident Matching Service. Statistics and reports, 2003–2005. Match reports. Ottawa, Ont: Canadian Resident Matching Service; 2006. [Accessed 2006 May 24]. Available at: http://www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Family Physicians. 2005 National Resident Matching Program. Leawood, Kan: American Academy of Family Physicians; 2006. [Accessed 2006 May 24]. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/match/table01.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinowitz HK. The role of the medical school admission process in the production of generalist physicians. Acad Med. 1999;74(1 Suppl):S39–44. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199901001-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bland CJ, Meurer LN, Maldonado G. Determinants of primary care specialty choice: a non-statistical meta-analysis of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70:620–41. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellsbury KE, Burack JH, Irby DM, Stritter FT, Ambrozy DM, Carline JD, et al. The shift to primary care: emerging influences on specialty choice. Acad Med. 1996;71(Suppl 10):S16–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199610000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fincher RM, Lewis LA, Rogers LQ. Classification model that predicts medical students’ choices of primary care or non-primary care specialties. Acad Med. 1992;67:324–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199205000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassebaum DG, Szenas PL, Schuchert MK. Determinants of the generalist career intentions of 1995 graduating medical students. Acad Med. 1996;71:198–209. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199602000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassler W, Wartman S, Silliman R. Why medical students choose primary care careers. Acad Med. 1991;66:41–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mutha S, Takayama JI, O’Neil EH. Insights into medical students’ career choices based on third and fourth year students’ focus group discussions. Acad Med. 1997;72:635–40. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199707000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenthal MP, Diamond JJ, Rabinowitz HK, Bauer LC, Jones RL, Kearl GW, et al. Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students’ decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA. 1994;271(12):914–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen SS, Sherman MB, Bland CJ, Fiola JA. Effect of early exposure to family medicine on students’ attitudes toward the specialty. J Med Educ. 1987;62:911–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campos-Outcalt D, Senf J. Characteristics of medical schools related to the choice of family medicine as a specialty. Acad Med. 1989;64:610–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duerson M, Crandall L, Dwyer J. Impact of a required family medicine clerkship on medical students’ attitudes about primary care. Acad Med. 1989;64:546–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meurer L. Influence of medical school curriculum on primary care specialty choice: analysis and synthesis of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70:388–97. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199505000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basco W, Jr, Bell Buchbinder S, Duggan A, Wilson M. Associations between primary care-oriented practices in medical school admission and the practice intentions of matriculants. Acad Med. 1998;73:1207–10. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz L, Sarnacki R, Schimpfhauser F. The role of negative factors in changes in career selection by medical students. J Med Educ. 1984;59:285–90. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paiva R, Vu N, Verhulst S. The effect of clinical experiences in medical school on specialty choice decisions. J Med Educ. 1982;57:666–74. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiner E, Stoken J. Overcoming barriers to generalism in medicine: the residents’ perspective. Acad Med. 1995;70(Suppl 1):89–94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199501000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connelly M, Sullivan A, Peters A, Clark-Chiarelli N, Zotov N, Martin N, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. A national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(3):159–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.01208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geertsma R, Romano J. Relationship between expected indebtedness and career choice of medical students. J Med Educ. 1986;61:555–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tardiff K, Cella D, Seiferth C, Perry S. Selection and change of specialties by medical school graduates. J Med Educ. 1986;61:790–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senf J, Campos-Outcalt D, Watkins A, Bastacky S, Killian C. A systematic analysis of how medical school characteristics relate to graduates’ choices of primary care specialties. Acad Med. 1997;72:524–33. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whitcomb M, Cullen T, Hart L, Lishner D, Rosenblatt R. Comparing the characteristics of schools that produce high percentages and low percentages of primary care physicians. Acad Med. 1992;67:587–91. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199209000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland C, Meurer L, Maldonado G. Determinants of primary care specialty choice: a non-statistical meta-analysis of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70:620–41. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babbott D, Baldwin D, Jolly P, Williams D. The stability of early specialty preferences among US medical school graduates in 1983. JAMA. 1988;259(13):1970–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markert R. Why medical students change to and from primary care as a career choice. Fam Med. 1991;23(5):347–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright B, Scott I, Woloschuk W, Brenneis F, Bradley J. Career choice of new medical students at three Canadian universities: family medicine versus specialty medicine. CMAJ. 2004;170(13):1920–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynn M. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35(6):382–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kassebaum DG, Szenas PL. Medical students’ career indecision and specialty rejection: roads not taken. Acad Med. 1995;70:937–43. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeldow PB, Preston RC, Daugherty SR. The decision to enter a medical specialty: timing and stability. Med Educ. 1992;26:327–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1992.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coffin SE, Babbott D. Early and final preferences for pediatrics as a specialty: a study of U.S. medical school graduates in 1983. Acad Med. 1989;64:600–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carline J, Greer T. Comparing physicians' specialty interests upon entering medical school with their eventual practice specialties. Acad Med. 1991;66:44–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babbott D, Baldwin DC, Jr, Killian CD, Weaver SO. Trends in evolution of specialty choice. Comparison of US medical school graduates in 1983 and 1987. JAMA. 1989;261(16):2367–73. Erratum in: JAMA 1990;263:6–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]