Abstract

Background

Ectopic lymphoid neogenesis (LN) occurs in rheumatoid synovium, where it is thought to drive local antigen‐dependent B cell development and autoantibody production. This process involves the expression of specific homing chemokines and the development of high endothelial venules (HEV).

Objective

To investigate whether these mechanisms occur in psoriatic arthritis (PsA) synovium, where autoantibodies have not been described and the organisation and function of B cells is not clear, and to analyse their clinical correlates.

Methods

Arthroscopic synovial biopsy specimens from patients with PsA before and after tumour necrosis factor α blockade were characterised by immunohistochemical analysis for T/B cell segregation, peripheral lymph node addressin (PNAd)‐positive HEV, and the expression of CXCL13, CCL21 and CXCL12 chemokines in relation to the size of lymphoid aggregates.

Results

Lymphoid aggregates of variable sizes were observed in 25 of 27 PsA synovial tissues. T/B cell segregation was often observed, and was correlated with the size of lymphoid aggregates. A close relationship between the presence of large and highly organised aggregates, the development of PNAd+ HEV, and the expression of CXCL13 and CCL21 was found. Large organised aggregates with all LN features were found in 13 of 27 tissues. LN in PsA synovitis was not related to the duration, pattern or severity of the disease. The synovial LN pattern remained stable over time in persistent synovitis, but a complete response to treatment was associated with a regression of the LN features.

Conclusions

LN occurs frequently in inflamed PsA synovial tissues. Highly organised follicles display the characteristic features of PNAd+ HEV and CXCL13 and CCL21 expression, demonstrating that the microanatomical bases for germinal centre formation are present in PsA. The regression of LN on effective treatment indicates that the pathogenic and clinical relevance of these structures in PsA merits further investigation.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory joint disease associated with skin psoriasis. It is usually included within the spondyloarthritis group of inflammatory joint diseases, with which it shares several phenotypic features.1 However, although the peripheral joint involvement often displays a different distribution, the clinical and pathogenic features of PsA partially overlap those of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and both diseases can lead to significant bone and cartilage destruction.2

Histopathological analyses of RA and PsA synovial tissues point to differential features that can be of potential value in the diagnostic classification of patients with undifferentiated arthritis, although the fundamental features are similar.3,4,5 Neovascularisation, infiltration by mononuclear cells (T and B lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages) and synovial lining hyperplasia are observed in both conditions. B cells and plasma cells are important components of inflammatory infiltrates in both diseases, and follicular aggregates of lymphocytes resembling lymphoid follicles have been well characterised in RA but only occasionally described in PsA.6,7,8,9,10,11

In RA, several studies have confirmed the presence of competent germinal centres (GCs) both at the structural and at the molecular level.6,7,8,9,12 This process of organisation of T and B cells is called ectopic LN, and it is associated with the development of high endothelial venules (HEV) and the ectopic expression of a restricted set of homing chemokines, physiologically involved in the traffic and tissue compartmentalisation of T and B cells in secondary lymphoid organs.6,8 The role of these factors in ectopic LN has been shown in relevant murine transgenic models. In such models, the process can be driven by enforced ectopic expression of lymphotoxin (LT)‐αβ or that of the homing chemokines CXCL13, CCL21 or CXCL12.13,14,15 Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α, and particularly, lymphotoxin (LT)‐αβ play a potential role in the development of the HEV phenotype and the expression of homing chemokines, and in RA they seem to contribute to LN.6,16,17 The expression of TNFα and LTβ has also been demonstrated in PsA, but LN and GC formation has not been studied in PsA synovium.18,19

On the basis of structural and molecular similarities between genuine GC in lymphoid tissues and LN in RA synovitis, it has been suggested that these structures may play a role in local antigen‐driven B cell development and autoantibody responses. They may also contribute to other processes such as antigen presentation and costimulation of T cells, and synthesis of soluble mediators, which could collectively explain the therapeutic efficacy of B cell depletion.20 In PsA, clonal expansion of synovial B and T cells supporting a local antigen‐driven process has also been suggested but, in contrast with RA, the lack of detectable autoantibodies makes the role of B cells uncertain.21,22

We have searched for the presence of ectopic LN in PsA synovial tissues and its relationship to the expression of homing chemokines and the development of PNAd+ HEV. Our data demonstrate that a significant proportion of patients with PsA contain large and well‐organised T/B cell aggregates and that this phenomenon is closely related to the development of PNAd+ HEV and the expression of homing chemokines CXCL13 and CCL21. These features do not seem to indicate a particular clinical subset, but can disappear after full remission of the disease.

Patients and methods

Patients and biopsies

Synovial biopsy specimens were obtained by needle arthroscopy from 27 patients with PsA1 selected by the presence of active synovitis (pain and inflammatory synovial fluid) of the knee. In eight patients, a second biopsy specimen of the same knee was obtained after 12 weeks of treatment with a TNFα antagonist (six etanercept and two infliximab). In three additional patients, a second contralateral knee biopsy specimen was obtained after a variable time while still taking the same treatment. These second biopsy specimens are independently described and analysed. Disease activity was measured by Disease Activity Score (DAS) 28. The type and extent of psoriasis were recorded before arthroscopy.23,24 All patients gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Arthroscopy was performed with an arthroscope of diameter 2.7 mm (Storz, Tullingen, Germany) without lavage. For technical reasons, only 150–250 ml of saline was injected, without intra‐articular steroids. In all, 8–12 samples were obtained from each patient from the suprapatellar pouch and the medial gutter. Biopsy specimens were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin wax.

Immunohistochemistry

Sequential sections of PsA synovial tissues were analysed for the presence of lymphoid aggregates and the expression of the following markers by peroxidase immunohistochemical analysis. T cells were labelled with rabbit anti‐human CD3 polyclonal (A0452, DAKO, Cambridge, UK), B cells with mouse anti‐human CD20 (clone L26, DAKO), HEV with rat anti‐human PNAd (clone MECA‐79, PharMingen, Oxford, UK), CXCL13 with goat anti‐human CXCL13 polyclonal (AF801, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), CCL21 with goat anti‐human CCL21 polyclonal (AF366, R&D Systems) and CXCL12 with mouse anti‐human CXCL12 K15C monoclonal antibody.25 Positive controls included similarly processed human tonsil sections, and negative controls included non‐immune matched mouse, rat or goat immunoglobulins instead of the primary antibodies. Antigen retrieval was required for most antibodies, and it was performed by microwave heating in 1 mM EDTA for 15 min. Primary antibodies were developed with appropriate secondary biotinylated antibodies, following a biotin peroxidase‐based method (ABC, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California, USA), and using diaminobenzidine as chromogen. Sections were finally counterstained in Gill's haematoxylin.

Analysis of lymphoid aggregates

The highest grade of lymphoid aggregation within each synovial tissue sample was determined according to a previously described scoring method,8 based on the number of radial cell counts such that grade 1 corresponded to 2–5 radial cell counts, grade 2 corresponded to 6–10 radial cell counts and grade 3 corresponded to >10 radial cell counts. The presence of T/B cell segregation, PNAd+ HEV, and CXCL13, CCL21 or CXCL12 within lymphoid aggregates was analysed. Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate associations of the presence or absence of all qualitative variables in the different groups. Quantitative variables were analysed using the non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

Clinical and histopathological features

A total of 27 patients with PsA with a clinically inflamed knee joint were included, 66% of whom were men, and they had a disease duration (mean (SD)) of 82.6 (107) months. Seven (26%) patients had a disease duration of <1 year (3.1 (2.2) months). Also, 17 (63%) patients had oligoarthritis and 10 (37%) had polyarthritis; 12 (48%) patients had erosive disease; 16 (59%) patients had type I and 11 (41%) type II psoriasis. The extent of psoriasis as measured by Physician's Global Assessment (n = 24) was severe in one, moderate in eight, mild in seven, minimal in eight and clear in three patients. In all, 9 (33%) patients were taking disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug treatment (eight taking methotrexate and one taking chloroquine) at the time of arthroscopy. DAS28 was 4.1+1.2, and none of the patients was rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) positive. Table 1 summarises the clinical and demographic features.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical data of patients with psoriatic arthritis.

| All patients (n = 27) | LN features + (n = 13) | LN features − (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 18 (67) | 7 (54) | 11 (79) |

| Age (years) | 44.2 (13.5) | 44.3 (14.5) | 44.2 (13) |

| Disease duration (months) | 82.6 (107) | 69.9 (111.3) | 94.3 (105.8) |

| Early disease (<6 months) | 7 (26) | 4 (31) | 3 (21) |

| Erosive disease | 12 (44) | 4 (31) | 8 (57) |

| Clinical pattern | |||

| Oligoarthritis | 17 (63) | 9 (69) | 8 (57) |

| Polyarthritis | 10 (37) | 4 (31) | 6 (43) |

| Cutaneous psoriasis | |||

| Type I | 16 (59) | 7 (53) | 9 (64) |

| Type II | 11 (41) | 6 (47) | 5 (36) |

| Psoriasis extent | |||

| Severe | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (7.1) |

| Moderate | 8 (30) | 4 (31) | 4 (28.6) |

| Mild | 7 (24) | 3 (23) | 4 (28.6) |

| Minimal | 8 (30) | 4 (31) | 4 (28.6) |

| Clear | 3 (12) | 2 (15) | 1 (7.1) |

| DMARD use before biopsy | 9 (33.3) | 5 (38) | (28.6) |

| Anti‐TNF treatment along follow‐up | 12 (44) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (35.7) |

| DAS28 | 4.1 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.3) | 4.2 (1) |

DAS, Disease Activity Score; DMARD, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; LN, lymphoid neogenesis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Values are given as mean (SD) or (%). Patients with LN features include those with grade 3 infiltrates, T/B cell segregation, peripheral lymph node addressin‐positive high endothelial venule, and CXCL13 and CCL21 expression. There were no significant differences between LN+ and LN− groups.

All tissue samples contained synovial lining and inflammatory infiltration of the sublining. In 25 of 27 synovial tissues, aggregation of mononuclear cell infiltrates (lymphoid aggregation) was detected.

Grading of aggregates and T/B cell segregation

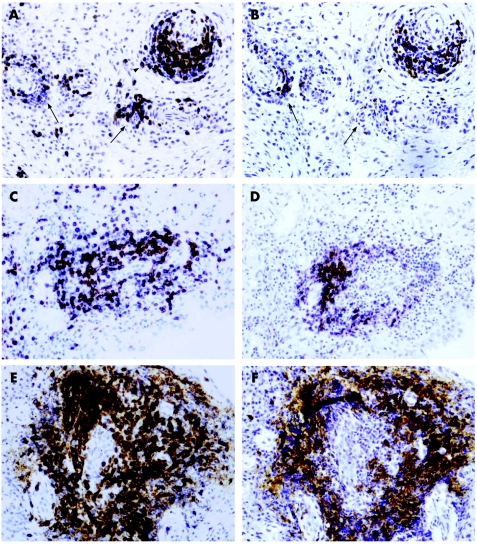

The 27 PsA synovial tissues were classified according to the highest grade of lymphoid aggregation present (table 2, fig 1): 2 tissues contained no aggregates, 10 had only grade 1 or 2 aggregates and 15 had large grade 3 aggregates (range 1–27 aggregates, mean (SD) 5.6 (7.8) per tissue section). The number, proportion and grade of aggregates present in each section is presented in an online supplementary table (available at http://ard.bmj.com/supplemental).

Table 2 Histomorphological grading and lymphoid neogenesis markers in psoriatic arthritis synovial tissues.

| Number of tissues* | T/B segregation | PNAd+ HEV | CXCL13 | CCL21 | CXCL12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 5 (20%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 5 (100%) |

| Grade 2 | 5 (20%) | 3 (60%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | 5 (100%) |

| Grade 3 | 15 (60%) | 14 (93%)† | 14 (93%)‡ | 14 (93%)§ | 14 (93%)¶ | 15 (100%) |

HEV, high endothelial venule; PNAd, peripheral lymph node addressin.

*Grades correspond to the highest grade of lymphoid aggregation present in a synovial tissue, and percentages in this column are taken from the total number of patients (n = 25). Tissues from two patients did not contain detectable lymphoid aggregates and were not included here. All other data are presented as the number and percentage of tissues positive for each particular feature within the subgroup of tissues with the indicated grade.

†p<0.008.

‡p<0.001.

§p<0.003.

¶p<0.03 grade 3 vs grade 1 and 2 groups (Fisher's exact test).

Figure 1 Histological grading of lymphoid aggregates. Grade 1 (arrows) and 2 (arrowhead) (A, B), grade 2 (C, D) and grade 3 (E, F) aggregates showing the distribution of T cells (A, C, E), and B cells (B, D, F), in serial consecutive sections representative of 25 patients with psoriatic arthritis are shown. Grade 2 and 3 aggregates shown in C, D and E, F were classified as T/B cell segregated, whereas grade 1 and 2 shown in A, B were not. Original magnification ×400.

T/B cell segregation was observed in all groups, but the proportion of T/B cell segregated lymphoid infiltrates was increased in parallel to the grade of lymphoid aggregation: half of the grade 1 and 2 infiltrates displayed T/B cell segregation, whereas all but one grade 3 infiltrates displayed these features (table 2, fig 1 and online supplementary table; supplementary table available at http://ard.bmj.com/supplemental).

Presence of HEV and chemokine expression

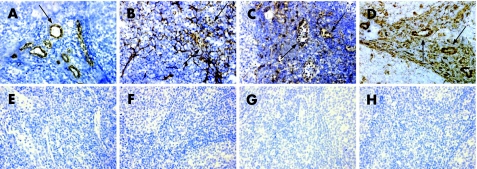

We first studied control tonsil sections to confirm the specificity of antibodies. We observed a specific pattern of PNAd, CXCL13, CCL21 and CXCL12 expression similar to that described previously.8,26,27 PNAd‐associated MECA‐79 epitope was specifically detected on HEV (fig 2A). CXCL13 was predominantly detected in stromal follicular dendritic cell‐like networks of the dark zone of GCs (fig 2B). Weak CXCL13 immunostaining was present in some HEV. CCL21 expression was predominantly present in stromal cells and HEV of the perifollicular areas (fig 2C). CXCL12 was detected in stromal cells, and a strong immunostaining was also observed on the endothelium of HEV in the dark zone of GC and perifollicular areas (fig 2D). CXCL12 and CCL21 were also detected in the crypt epithelium (data not shown). Matched non‐immune immunoglobulin controls did not produce a detectable immunostaining (figs 2E–F).

Figure 2 Specificity of peripheral lymph node addressin (PNAd) and homing chemokine immunostaining in human tonsil sections. Human tonsil sections were immunostained for PNAd (MECA‐79; A), CXCL13 (B), CCL21 (C) and CXCL12 (D). Note the variable staining of high endothelial venule (arrows) for the different chemokines. Lower panels (E–H) show non‐immune immunoglobulin controls matched to the corresponding upper panel. Original magnification ×400.

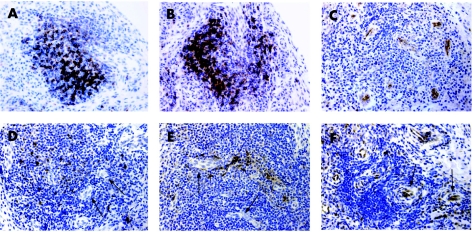

Vessels with HEV morphological features and the presence of the HEV‐associated PNAd (MECA‐79) epitope were exclusively observed within lymphoid aggregates of tissues containing grade 3 aggregates with T/B cell segregation (table 2, fig 3C). In these tissues, PNAd+ HEV were predominantly located within or in the periphery of large grade 3 aggregates.

Figure 3 Lymphoid neogenesis features in grade 3 lymphoid aggregates in psoriatic arthritis synovial tissues. All sections correspond to grade 3 aggregates from the same individual immunostained for CD3 (T cells; A), CD20 (B cells; B), peripheral lymph node addressin (MECA‐79) (C), CXCL13 (D), CCL21 (E) and CXCL12 (F). (A) and (B) are parallel sections of the same tissue and show the same lymphoid aggregate. Note the variable staining of high endothelial venule (arrows) for the different chemokines. Original magnification ×400.

CXCL13 immunostaining was restricted to scattered cells of stromal or large mononuclear shape within lymphoid aggregates (fig 3D). CXCL13+ cells were not organised as follicular dendritic cell‐like networks as observed in tonsils. Similar to what was observed in tonsils, CXCL13 immunostaining was detectable on some HEV, although it was very weak compared with CXCL13‐positive stromal or mononuclear cells. CXCL13 was not detected in other synovial areas such as synovial lining cells. With the exception of one single case, all tissues classified as grade 3 displayed CXCL13 immunostaining (table 2). CXCL13 was detected in only 3 of 10 tissues containing grade 1 or 2 aggregates, which in all 3 cases showed T/B cell segregation.

CCL21 immunostaining was detected in 14 of 15 grade 3 tissues, in cells of stromal shape located within lymphoid aggregates in a HEV perivascular location with only occasional and weak staining of HEV (table 2, fig 3E). In 4 of 10 grade 1 or 2 tissues, CCL21 immunostaining was also detectable in some lymphoid aggregates that also displayed T/B cell segregation. In some tissues, synovial lining CCL21 immunostaining was also observed, but it was weaker than that observed within lymphoid aggregates and did not correlate with either the grade of lymphoid aggregation or with the presence of CCL21 within lymphoid aggregates (data not shown).

CXCL12 immunostaining was detected in all tissues studied for PsA. The pattern was similar to that described previously in RA, and included the synovial lining layer, sublining scattered fibroblasts and blood vessels.28 Within grade 3 lymphoid aggregates containing HEV, a strong immunostaining was observed on HEV endothelium and perivascular stromal cells (fig 3F), in contrast with the weak or undetectable HEV immunostaining for CXCL13 and CCL21. However, the presence of CXCL12 in stromal cells was similar in all groups of tissues and among differently graded or T/B cell‐segregated aggregates.

Correlation with clinical features

Patients were stratified by the presence or absence of LN features (PNAd+ HEV, CXCL13+, CCL21+ and large grade 3 organised aggregates) in biopsies. There were no statistically significant differences between the LN+ (n = 13) or LN− (n = 14) groups regarding gender, age, disease duration, erosive disease, articular pattern (oligoarticular versus polyarticular), psoriasis type and extent, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs taken before arthroscopy, disease activity score or initiation of anti‐TNFα therapy during follow‐up (mean (SD) time to initiation 2.8 (1.6) years; table 1).

Response to treatment

Eleven patients underwent two biopsies over time during treatment. In three patients who were not treated with TNFα blockade and were therefore considered as a negative control group, a second biopsy specimen of the contralateral knee was obtained after a mean (SD) of 25 (18) months in the presence of persistent active synovitis. Two patients had no LN features at the first biopsy (lack of follicles with T/B cell segregation and no expression of MECA, CXCL13 or CCL21), and these features remained unchanged in the second biopsy (except for CCL21 positivity in one of them). One of them had moderate improvement in the DAS28, whereas the other did not have any change in disease activity. The third patient exhibited LN features in both biopsies without changes in DAS 28 (table 3).

Table 3 Clinical and synovial immunohistological data of 11 rebiopsied patients*.

| Patient number | Biopsy | Treatment | Knee synovitis | DAS28 | Grade 3 follicles (%) | PNAd+ HEV | CXCL13 | CCL21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Right | MTX | Yes | 6.0 | 38 | + | + | + |

| Left | MTX | Yes | 5.9 | 40 | + | + | + | |

| 2 | Right | NSAID | Yes | 3.3 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Left | NSAID | Yes | 3.4 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| 3 | Right | NSAID | Yes | 4.4 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Left | NSAID | Yes | 3.4 | 0 | – | – | + | |

| 4 | First | MTX | Yes | 6.5 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Second | MTX+ETN | No | 3.1 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| 5 | First | MTX | Yes | 4.2 | 40 | + | + | + |

| Second | MTX+ETN | Yes | 3.1 | 62 | + | + | + | |

| 6 | First | MTX | Yes | 5.7 | 23 | + | + | + |

| Second | MTX+ETN | Yes | 4.4 | 63 | + | + | + | |

| 7 | First | MTX | Yes | 4.5 | 13 | + | + | + |

| Second | MTX+ETN | Yes | 4.3 | 49 | + | + | + | |

| 8 | First | NSAID | Yes | 3.5 | 25 | + | + | + |

| Second | IFX | Yes | 3.3 | 40 | + | + | + | |

| 9 | First | MTX | Yes | 6.0 | 38 | + | + | + |

| Second | MTX+ETN | No | 1.6 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| 10 | First | MTX | Yes | 4.7 | 57 | + | + | + |

| Second | MTX+ETN | No | 1.5 | 0 | – | – | – | |

| 11 | First | NSAID | Yes | 4.7 | 34 | + | + | + |

| Second | IFX | No | 0.7 | 0 | – | – | – |

DAS, Disease Activity Score; ETN, etanercept; HEV, high endothelial venules; IFX, infliximab; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; PNAd, peripheral lymph node addressin.

*Patients 1–3 were rebiopsied at the contralateral knee with active synovitis after a mean (SD) of 25 (18) months from the first contralateral biopsy; they were receiving stable treatment. Patients 4–11 were rebiopsied at the same knee after 3 months of anti‐TNFα treatment.

One patient treated with anti‐TNFα with good improvement (DAS28 at first biopsy 6.49 and after treatment 3.07) lacked LN features in both biopsies (table 4).

Four patients with LN features in the first biopsy were treated with anti‐TNFα: two had moderate improvement and the other two had no improvement as evaluated by DAS28 response criteria. All of them had, at least, active synovitis in the knee at week 12 when the second biopsy was performed; in these four patients, LN features were unchanged in the post‐treatment biopsy.

In the other three patients, LN features present at first biopsy disappeared in the second biopsy, after all of them achieved full remission of the disease (DAS after treatment ⩽1.6; table 4). These three patients are still in remission after 18, 24 and 68 months of follow‐up.

Discussion

The formation of ectopic LN is a well‐recognised feature of several chronic inflammatory diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome, autoimmune thyroid disease, and RA and chronic infections.9,29,30 In lymphoid tissues, these anatomical microstructures permit the functional interaction of antigen‐presenting cells, T cells and B cells. GC are critical in the development of B cell immune responses because they provide an infrastructure to capture and store antigen, which drives B cell development and differentiation into affinity‐selected memory B cells and plasma cells. The structural and molecular similarities between genuine GC and ectopic lymphoid follicles may suggest the immunological competence of these structures as GC.9,31,32 The contribution of these structures to autoantibody responses against local autoantigens has been suggested, but they may also play a role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory conditions by driving T cell responses and producing proinflammatory cytokines.13,33

The expression of CXCL13 and CCL21 homing chemokines and the development of HEV have been identified as necessary components for cell recruitment and compartmentalisation into functional zones during the development of lymphoid organs and ectopic LN.8,14,15,34 We show for the first time evidence that in PsA these chemokines are locally expressed and significantly correlate with cell cluster enlargement and organisation in a secondary lymphoid organ‐like fashion. The close relationship between expression of CXCL13 and CCL21 chemokines, HEV development and ectopic LN development is consistent with previous observations in RA, reinforcing the concept of some common physiopathological processes in both conditions.6,8 The proportion of patients showing LN features in our PsA series is similar to that described previously in RA. However, the relative extension of this process in PsA cannot be compared with the previous RA series that includes larger surgically obtained synovial tissue samples.6,8

The presence of T/B cell segregation and homing chemokine expression in some small aggregates in the absence of HEV suggest a sequential process, the last step of which is HEV development and may specifically contribute to the enlargement of lymphoid aggregates, consistently with their well‐known role in L‐selectin‐initiated B and T cell recruitment from the bloodstream.35 By contrast, CXCL12 expression did not correlate with the grade of cell aggregation, T/B cell segregation or the presence of PNAd+ HEV. Interestingly, CXCL12 has been associated to ectopic B cell recruitment and compartmentalisation,14,27 and our present data show that it is the most abundant chemokine in the HEVs of tonsils or PsA tissues. Therefore, we cannot discard a specific role for CXCL12 in PsA LN, although its expression by stromal cells does not seem sufficient to drive this process. We have previously shown that in RA, CXCL12 mRNA is only expressed by stromal cells, whereas the protein is displayed on surface heparan sulphate proteoglycans of endothelial cells.28,29 The development of the HEV phenotype might specifically be associated to enhanced endothelial docking of CXCL12, as suggested by its abundant presence in RA and PsA HEV.29

The clinical implications of ectopic LN, as well as the potential effects of treatment on this process, have not been elucidated in RA. Our data on PsA suggest that synovial LN is not related to disease duration or severity, and rather seems to be an individual feature, as hypothesised in RA.9 A non‐significant trend towards longer disease duration and more erosive disease in LN− patients also argues against LN as a factor of severity, but should be taken with caution due to the small sample size.

In PsA, our previously published data showed a decrease in the vascularity but not in lymphoid infiltration after anti‐TNFα treatment.36 Our present data obtained from 11 patients who underwent two biopsies point to the stability of the LN pattern in persistent synovitis, but regression of lymphoid neogenesis features in association with complete remission induced by anti‐TNFα treatment. The potential role of TNFα and particularly LTαβ in driving HEV development and homing chemokine expression has been shown in animal and human cellular models.13,17 Further studies with larger samples are needed to search for the clinical correlates of this process and to extend our observation of the regression of these lymphoid structures and HEV in association to favourable therapeutic outcomes.

The demonstration of LN is particularly intriguing in PsA because the contribution of B cells to its pathogenesis and, particularly, the development of local B cell autoantibody responses have not been explored. In cutaneous psoriasis, LN has not been described and B cells are not an abundant component, suggesting tissue‐specific differences. Specific autoantibodies in PsA have not been described, and RF or anti‐CCP antibodies have been detected only in a small proportion of patients.37 In the present series, all patients were RF and anti‐CCP negative, excluding an association between these autoantibodies and LN. This contrasts with one study in RA, where the presence of RF has been associated to higher aggregation of infiltrates.16 B cells could also drive antibody‐independent synovial inflammation through the development of T cell responses or by enhancing cytokine production.33 Further studies of the molecular phenotype of synovial B cells and the effects of specific B cell depletion therapy in PsA may be of help to address the potential pathogenetic role of B cells in this disease.

In conclusion, LN occurs in the synovium of a significant proportion of patients with PsA. Analysis of clinical data and changes in rebiopsied patients suggest that LN is a stable and individual feature that is reverted only by full remission after treatment. Since specific autoantibodies have not been described in PsA, these findings encourage further studies to determine the role of synovial B cells in PsA.

Supplementary table is available online at http://ard.bmj.com/supplemental

Copyright © 2007 BMJ Publishing Group and European League Against Rheumatism

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

JDC was supported by research grants from Fondo de investigación sanitaria (FIS 04/1023 and 1027, and FIS 05/0913), by a research award from the IDIBAPS and by a grant from Wyeth. JLP was supported by FIS 05/0060 and by a grant from Schering Plough, SA, TC and DB were supported by the European Community's FP6 funding. This publication reflects only the author's views. The European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information herein. We thank Dr Arenzana‐Seisdedos for kindly providing K15C the anti‐CXCL12 mAb.

Abbreviations

CCP - cyclic citrullinated peptide

CRP - C reactive protein

DAS - Disease Activity Score

ESR - erythrocyte sedimentation rate

GC - germinal centres

HEV - high endothelial venule

LN - lymphoid neogenesis

LT - lymphotoxin

PNAd - peripheral lymph node addressin

PsA - psoriatic arthritis

RA - rheumatoid arthritis

RF - rheumatoid factor

TNF - tumour necrosis factor

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Supplementary table is available online at http://ard.bmj.com/supplemental

References

- 1.Helliwell P S, Taylor W J. Classification and diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 200564(Suppl 2)ii3–ii8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gladman D D, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg D O, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 200564(Suppl 2)ii14–ii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veale D, Yanni G, Rogers S, Barnes L, Bresnihan B, Fitzgerald O. Reduced synovial membrane macrophage numbers, ELAM‐1 expression, and lining layer hyperplasia in psoriatic arthritis as compared with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 199336893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvador G, Sanmarti R, Garcia‐Peiro A, Rodriguez‐Cros J, Muñoz‐Gomez J, Cañete J D. p53 expression in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis synovial tissue and association with joint damage. Ann Rheum Dis 200564183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veale D J, Barnes L, Rogers S, FitzGerald O. Immunohistochemical markers for arthritis in psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis 199453450–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takemura S, Braun A, Crowson C, Kurtin P J, Cofield R H, O'Fallon W M.et al Lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatoid synovitis. J Immunol 20011671072–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang Y M, Zhang X, Wagner U G, Yang H, Beckenbaugh R D, Kurtin P J.et al CD8 T cells are required for the formation of ectopic germinal centers in rheumatoid synovitis. J Exp Med 20021951325–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzo A, Paoletti S, Carulli M, Blades M C, Barone F, Yanni G.et al Systematic microanatomical analysis of CXCL13 and CCL21 in situ production and progressive lymphoid organization in rheumatoid synovitis. Eur J Immunol 2005351347–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weyand C M, Goronzy J J. Ectopic germinal center formation in rheumatoid synovitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003987140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kruithof E, Baeten D, De Rycke L, Vandooren B, Foell D, Roth J.et al Synovial histopathology of psoriatic arthritis, both oligo‐ and polyarticular, resembles spondyloarthropathy more than it does rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 20057R569–R580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baeten D, Kruithof E, De Rycke L, Vandooren B, Wyns B, Boullart L.et al Diagnostic classification of spondyloarthropathy and rheumatoid arthritis by synovial histopathology: a prospective study in 154 consecutive patients. Arthritis Rheum 2004502931–2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroder A E, Greiner A, Seyfert C, Berek C. Differentiation of B cells in the nonlymphoid tissue of the synovial membrane of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 199693221–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kratz A, Campos‐Neto A, Hanson M S, Ruddle N H. Chronic inflammation caused by lymphotoxin is lymphoid neogenesis. J Exp Med 19961831461–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luther S A, Bidgol A, Hargreaves D C, Schmidt A, Xu Y, Paniyadi J M.et al Differing activities of homeostatic chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL12 in lymphocyte and dendritic cell recruitment and lymphoid neogenesis. J Immunol 2002169424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luther S A, Lopez T, Bai W, Hanahan D, Cyster J G. BLC expression in pancreatic islets causes B cell recruitment and lymphotoxin‐dependent lymphoid neogenesis. Immunity 200012471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klimiuk P A, Goronzy J J, Bjornsson J, Beckenbaugh R D, Weyand C M. Tissue cytokine patterns distinguish variants of rheumatoid synovitis. Am J Pathol 19971511311–1319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pablos J L, Santiago B, Tsay D, Singer M S, Palao G, Galindo M.et al A HEV‐restricted sulfotransferase is expressed in rheumatoid arthritis synovium and is induced by lymphotoxin‐alpha/beta and TNF‐alpha in cultured endothelial cells. BMC Immunol 200566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partsch G, Steiner G, Leeb B F, Dunky A, Broll H, Smolen J S. Highly increased levels of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha and other proinflammatory cytokines in psoriatic arthritis synovial fluid. J Rheumatol 199724518–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riccieri V, Spadaro A, Taccari E, Zoppini A, Koo E, Ortutay J.et al Adhesion molecule expression in the synovial membrane of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 200261569–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards J C, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz‐Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close D R.et al Efficacy of B‐cell‐targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 20043502572–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costello P J, Winchester R J, Curran S A, Peterson K S, Kane D J, Bresnihan B.et al Psoriatic arthritis joint fluids are characterized by CD8 and CD4 T cell clonal expansions appear antigen driven. J Immunol 20011662878–2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerhard N, Krenn V, Magalhaes R, Morawietz L, Brandlein S, Konig A. IgVH‐genes analysis from psoriatic arthritis shows involvement of antigen‐activated synovial B‐lymphocytes. Z Rheumatol 200261718–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henseler T, Christophers E. Psoriasis of early and late onset: characterization of two type of psoriasis vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 198513450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon K B, Papp K A, Hamilton T K, Walicke P A, Dummer W, Li N.et al Efalizumab for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 20032903073–3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pablos J L, Amara A, Bouloc A, Santiago B, Caruz A, Galindo M.et al Stromal‐cell derived factor is expressed by dendritic cells and endothelium in human skin. Am J Pathol 19991551577–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen C D, Ansel K M, Low C, Lesley R, Tamamura H, Fujii N.et al Germinal center dark and light zone organization is mediated by CXCR4 and CXCR5. Nat Immunol 20045943–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casamayor‐Palleja M, Mondiere P, Amara A, Bella C, Dieu‐Nosjean M C, Caux C.et al Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein‐3alpha, stromal cell‐derived factor‐1, and B‐cell‐attracting chemokine‐1 identifies the tonsil crypt as an attractive site for B cells. Blood 2001973992–3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pablos J L, Santiago B, Galindo M, Torres C, Brehmer M T, Blanco F J.et al Synoviocyte‐derived CXCL12 is displayed on endothelium and induces angiogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Immunol 20031702147–2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santiago B, Baleux F, Palao G, Gutierrez‐Canas I, Ramirez J C, Arenzana‐Seisdedos F.et al CXCL12 is displayed by rheumatoid endothelial cells through its basic amino‐terminal motif on heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Arthritis Res Ther 20068R43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aloisi F, Pujol‐Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 20066205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weyand C M, Kurtin P J, Goronzy J J. Ectopic lymphoid organogenesis: a fast track for autoimmunity. Am J Pathol 2001159787–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gommerman J L, Browning J L. Lymphotoxin/light, lymphoid microenvironments and autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol 20033642–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takemura S, Klimiuk P A, Braun A, Goronzy J J, Weyand C M. T cell activation in rheumatoid synovium is B cell dependent. J Immunol 20011674710–4718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mebius R E. Organogenesis of lymphoid tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 20033292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauguet J M, Rosen S D, Marth J D, von Andrian U H. Core 2 branching beta1,6‐N‐acetylglucosaminyltransferase and high endothelial cell N‐acetylglucosamine‐6‐sulfotransferase exert differential control over B‐ and T‐lymphocyte homing to peripheral lymph nodes. Blood 20041044104–4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cañete J D, Pablos J L, Sanmarti R, Mallofre C, Marsal S, Maymo J.et al Antiangiogenic effects of anti‐tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy with infliximab in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004501636–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vander Cruyssen B, Hoffman I E, Zmierczak H, Van den Berghe M, Kruithof E, De Rycke L.et al Anti‐citrullinated peptide antibodies may occur in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005641145–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.