Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to describe the epidemiology of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in rheumatology practice at the beginning of the anti‐TNF (tumour necrosis factor) era, and to evaluate the initiation of anti‐TNF therapy in a clinical setting where prescription is regulated by the authority's imposed reimbursement criteria.

Methods

Between February 2004 and February 2005, all Belgian rheumatologists in academic and non‐academic outpatient settings were invited to register all AS patients who visited their practice. A random sample of these patients was further examined by an in‐depth clinical profile. In a follow‐up investigation, we recorded whether patients initiated anti‐TNF therapy and compared this to their eligibility at baseline evaluation.

Results

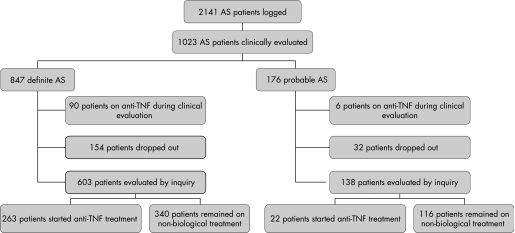

89 rheumatologists participated and registered 2141 patients; 1023 patients were clinically evaluated. These 847 fulfilled the New York modified criteria for definite AS and 176 for probable AS. The profile of AS in rheumatology practice is characterised by longstanding and active disease with a high frequency of extra‐articular manifestations and metrological and functional impairment. At a median of 2 months after the clinical evaluation, anti‐TNF therapy was initiated in 263 of 603 (44%) evaluable patients with definite AS and in 22 of 138 (16%) evaluable patients with probable AS (total 38%). More than 85% of the patients who started anti‐TNF therapy had an increased Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index despite previous NSAID (non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug) use.

Conclusions

Of a representative cohort of 1023 Belgian AS patients seen in daily rheumatology practice, about 40% commenced anti‐TNF therapy. Decision factors to start anti‐TNF therapy may include disease activity and severity.

Keywords: ankylosing spondylitis, epidemiology, anti‐TNF therapy, daily clinical practice

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is the prototype of spondyloarthropathy (SpA) characterised by sacroiliitis and may lead to a completely ankylosed spine in a substantial number of patients. In addition, peripheral arthritis and different extra‐articular manifestations, such as gut inflammation and eye involvement, are common features that add to the burden of the disease.

Until recently, the therapeutic options for AS have been limited to non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alongside education and physiotherapy (which remain the cornerstone of the treatment).1,2 Disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as sulphasalazine and methotrexate (MTX) demonstrated little or no effect on axial disease and are recommended only in patients with peripheral arthritis.2,3,4,5 However, tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors have recently been introduced in AS and have been shown to be effective drugs, improving the signs and symptoms of AS with a good benefit‐risk profile.6,7,8,9 With the aim of treating a population most likely to benefit (thus limiting widespread use of these expensive agents), recommendations on TNF agent use have been formulated by national10 and international experts (for example, ASAS)2,11,12 and served for prescription/reimbursement laws and guidelines in different countries. The aims of the present study were (1) to elucidate a profile of the Belgian AS population followed in daily clinical practice by rheumatologists in secondary and tertiary care centres at the time anti‐TNF therapy was introduced for treating AS, and (2) to evaluate the proportion of AS patients starting anti‐TNF therapy during the first year that these agents became available and determine the clinical characteristics of the patients who received them.

Methods

Rheumatologist selection

All Belgian rheumatology centres were contacted and asked to participate in this study.

In order to assure a representative sample, demographic data of the participants were collected and were compared with demographic data of the total Belgian rheumatologist population provided by the Royal Belgian Society of Rheumatology (KBVR‐SRBR).

Patient selection

Rheumatologists registered, in a confidential logbook, the birth dates and initials of all AS patients visiting their outpatient clinic during the study period. The number of registered patients in the logbook served as a denominator for a random selection of AS patients in whom the disease was documented further. For the in‐depth clinical evaluation, every week's first and fourth registered patient was evaluated using the study's case report form. If a patient was already included or refused to participate, the next consecutive patient of the same week was evaluated. This selection method was preferred over inclusion of consecutive patients as it allowed for time distribution of the amount of study related work, especially in academic centres. The maximum number of patients included per rheumatologist was limited to 20, thereby ensuring the study population was distributed between the participating rheumatologists' sites. All patients were informed about the study before inclusion and gave written informed consent with regard to data privacy.

Study parameters

The following data were collected in all patients who were randomly selected for epidemiological profiling: demographic data, previous and current pain patterns, peripheral disease, previous and current clinical extra‐articular disease (psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, uveitis), surgery, and comorbidities (arthroplasty, osteoporosis, spinal fracture). The following composite indices were evaluated: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functionality Index (BASFI: 0–10 rated on a numerical rating scale),13 Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI: 0–10 rated on a numerical rating scale)14 numerical scale and the components of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI).15 Laboratory testing included available HLA‐B27 status and latest available C reactive protein (CRP) value. Available radiographic data assessed were as follows: grading of the individual sacroiliac joints, presence of syndesmophytes, or presence of an ankylosis on latest available x rays. Patient history was also documented, including first degree family history of inflammatory diseases collected for AS, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), uveitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, as well as current and previous treatment included physiotherapy, NSAIDS (including duration and types of NSAIDs), corticosteroids, sulphasalazine, methotrexate, azathioprine, TNF blockers. For further analyses, patients who fulfilled the New York modified criteria for AS were categorised as having definite AS or probable AS16 (table 1). Also, for each patient, fulfilment of ASAS recommendations to start anti‐TNF therapy was computed. For this study, this implied that AS patients should have tried at least two NSAIDs and have a BASDAI ⩾4 before starting anti‐TNF therapy.2,11,12,17

Table 1 New York modified criteria (1984) for ankylosing spondylitis*.

| (1) Low back pain with inflammatory characteristics |

| (2) Limitation of lumbar spine motion in sagittal and frontal planes |

| (3) Decreased chest expansion |

| (4) Bilateral sacroiliitis grade 2 or higher |

| (5) Unilateral sacroiliitis grade 3 or higher |

| *Definite AS when the fourth or fifth criterion mentioned presents with any clinical criteria |

During an inquiry, approximately one year after the collection of all the above information, rheumatologists were asked to indicate whether anti‐TNF therapy was initiated in their patients. Rheumatologists were not informed beforehand that that this query would take place.

Quality assurance

The protocol and file were developed by collaboration of a board of academic and non‐academic rheumatologists and the study sponsor (Schering Plough). The protocol was designed to allow the maximum amount of data to be captured in a minimum amount of time during daily clinical practice. The CRF was tested in a peripheral centre (JL) on five patients and adapted according to the suggestions before its use in the protocol. The protocol was approved by the Belgian national licence bureau for non‐interventional research (Pharma.be) for good clinical practice and ethical approval.

In order to ensure data quality, two independent data nurses were assigned to the project and checked informed consents of all patients, logbooks, and CRF completeness.

Time frame

In‐depth profiling of patients occurred at one visit between February 2004 and February 2005. Between December 2005 and January 2006, rheumatologists were retrospectively asked whether anti‐TNF therapy was initiated since that in‐depth profile.

Study era and background

At that time infliximab (March 2003) and etanercept (November 2003) were registered but are reimbursed from March 2004 and September 2004, respectively. Between December 2005 and January 2006, rheumatologists were asked whether patients had started anti‐TNF therapy since that clinical evaluation. The reimbursement of anti‐TNF therapy in Belgium is similar for both drugs. To satisfy conditions set by the authorities. patients must fulfil the modified New York criteria for AS, insufficiently respond to conventional therapy, and present with the following: (1) severe axial symptoms reflected by a BASDAI ⩾4; (2) a CRP value higher than the upper limit of normal for the applicable laboratory (without specification about the time point that CRP must be elevated); (3) unless contraindicated, an insufficient response to previous optimal use of at least two NSAIDs at anti‐inflammatory doses for at least three months; and (4) an absence of active or latent tuberculosis. Furthermore, anti‐TNF treatment can only be prescribed by a board certified rheumatologist.

Statistical analyses

Consistent with the epidemiological objective of the study, descriptive statistics were used for the data. Differences between subgroups were compared by means of a Mann‐Whitney test for continuous variables and χ2 statistics for dichotomous data. Logistic regression models were fitted using the significant variables of a univariate analysis and after backward elimination using p values of 0.05 for removal. Different interaction terms were initially added to the models (but none remained in the final models). Analyses were performed by the commercially available statistical package SPSS 12.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Enrolment of rheumatologists

Eighty‐nine of all 204 (44%) board certified Belgian rheumatologists from 57 centres agreed to participate in the study. The majority of those rheumatologists (75%) worked in non‐academic centres; 45 of them worked in the French speaking part and 44 in the Dutch speaking part of Belgium; 40/49 rheumatologists were female/male. When comparing these rheumatologist demographics with the data provided by the Belgian rheumatologists' society, KBVR‐SRBR, there were no significant differences with regard to sex, type of practice, and geographical distribution. The mean study participation of the rheumatologists was 15 weeks (SD 7.4). Each week, the rheumatologists saw a mean of 2.2 AS patients (range 1–7, interquartile range 1.4).

Evaluation of the patients' sampling

In the logbooks, 2141 AS patients were registered. The planned in‐depth profiling was further conducted in 1023 patients. All patients fulfilled modified New York classification criteria,16 647 (83%) patients were classified as definite AS and 176 remained as probable AS (fig 1). The lag time between CRP measurement and the clinical evaluation was median 0 months (interquartile range 0.6 months). The lag time between radiology and the clinical evaluation was median 0.5 year (interquartile range 1.8).

Figure 1 Patient flow chart. AS, ankylosing spondylitis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Comparison of patients with definite and probable AS

Table 2 describes the baseline characteristics of the AS patients. An important difference between patients with definite AS and patients with probable AS is the difference of symptom duration, which is significantly higher in patients with definite AS (p<0.001). Patients with definite AS also had a higher disease activity (higher BASDAI, BASFI, and elevated CRP) and disease severity (higher BASMI, more syndesmophytes, bamboo spine, and hip involvement).

Table 2 Description of patients at baseline.

| Baseline evaluation | Definite AS (n = 847) | Probable AS (n = 176) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 68% | 49% | <0.001 |

| HLA‐B27 (n = 816) | 83% | 77% | 0.074 |

| Ever arthritis | 58% | 56% | 0.576 |

| Ever enthesitis | 50% | 52% | 0.573 |

| Elevated CRP | 37% | 18% | <0.001 |

| Syndesmophytes | 49% | 15% | <0.001 |

| Bamboo spine | 21% | 0% | <0.001 |

| Hip involvement | 27% | 15% | <0.001 |

| BASDAI* | 5.3 (2.1) | 4.7 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| BASDAI ⩾4 | 75% | 66% | 0.014 |

| BASFI* | 5.1 (2.5) | 3.6 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| BASMI* | 3.6 (2.4) | 2.4 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Symptom duration* | 18.0 (12) | 9.3 (9) | <0.001 |

| Disease duration* | 12.0 (66) | 5.8 (40) | <0.001 |

| Disease duration <1 month | 6% | 12% | 0.003 |

| Age* | 45 (11) | 40 (12) | <0.001 |

| Psoriasis | 11% | 11% | 0.846 |

| Uveitis (ever) | 27% | 17% | 0.002 |

| Crohn's disease | 8% | 7% | 0.854 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 3% | 2% | 0.678 |

| Ever MTX | 19% | 18% | 0.616 |

| Ever SSZ | 61% | 53% | 0.056 |

| Ever azathioprine | 4% | 7% | 0.102 |

| At least 2 NSAIDs used | 92% | 82% | 0.001 |

| Current NSAIDs | 72% | 63% | 0.020 |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CRP, C reactive protein; BASDAI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; BASFI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index; BASMI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis metrology index; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs. Symptom duration, disease duration since symptoms in years; disease duration, disease duration since diagnosis in years; disease duration <1 month, diagnosis was established within 1 month before the in‐depth clinical profiling; MTX, methotrexate; SSZ, sulphasalazine.

Definite AS and probable AS are defined according to the New York modified criteria.16

Percentages are given, except for continuous data: *mean (SD).

Anti‐TNF therapy in AS patients

At the time of the clinical evaluation (between February 2004 and February 2005), 90 (11%) patients with definite AS and six (3%) patients with probable AS were already being treated with anti‐TNF therapy. Most of these patients received anti‐TNF therapy in the context of studies or medical need programmes. These patients were further excluded from the analysis.

Of the remaining patients, 603 were evaluable for the inquiry into anti‐TNF treatment (between December 2005 and January 2006); 263 of those patients with definite AS started anti‐TNF therapy. The lag time between the clinical evaluation of the patient and the start of anti‐TNF therapy was estimated as median 2 months (range 0–23 months, interquartile range 5 months). In 121 patients, this lag time was less than 1 month. Table 3 describes the differences in baseline characteristics in function of the initiation of anti‐TNF treatment.

Table 3 Description of patients with AS as a function of the presence of anti‐TNF treatment at inquiry.

| Baseline evaluation | Definite AS | Probable AS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without anti‐TNF at query (n = 340) | With anti‐TNF at query (lag time <1 month) (n = 121) | With anti‐TNF at query (all patients) (n = 263) | p Value | Without anti‐TNF at query (n = 116) | With anti‐TNF at query (n = 22) | p Value | |

| MALE | 60% | 73% | 73% | 0.001 | 46% | 64% | 0.123 |

| HLA‐B27 | 77% | 92% | 88% | 0.001 | 76% | 68% | 0.451 |

| Arthritis | 22% | 27% | 29% | 0.029 | 28% | 46% | 0.114 |

| Enthesitis | 17% | 17% | 21% | 0.206 | 24% | 27% | 0.754 |

| Elevated CRP | 26% | 56% | 48% | <0.001 | 16% | 18% | 0.840 |

| Syndesmophytes | 38% | 57% | 45% | <0.001 | 16% | 15% | 0.920 |

| Bamboo spine | 16% | 25% | 24% | 0.023 | 0% | 0% | NA |

| Hip involvement | 22% | 37% | 36% | <0.001 | 14% | 32% | 0.038 |

| BASDAI* | 4.7 (2.2) | 6.4 (1.6) | 6.1 (1.7) | <0.001 | 4.4 (2.0) | 6.0 (1.6) | 0.001 |

| BASFI* | 4.4 (2.6) | 6.1 (2.0) | 5.9 (2.3) | <0.001 | 3.2 (2.2) | 5.6 (2.0) | 0.000 |

| BASMI* | 3.0 (2.3) | 4.1 (2.2) | 4.0 (2.4) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.8) | 0.179 |

| Age* | 45 (11) | 44 (11) | 44 (11) | 0.094 | 40 (12) | 38 (12) | 0.607 |

| Symptom duration | 18 (12) | 19 (13) | 19 (13) | 0.163 | 10 (8) | 11 (9) | 0.286 |

| Psoriasis | 10% | 12% | 12% | 0.560 | 9% | 23% | 0.051 |

| Uveitis | 25% | 26% | 31% | 0.096 | 12% | 32% | 0.018 |

| IBD | 9% | 9% | 10% | 0.901 | 5% | 14% | 0.116 |

| Any extra‐articular manifestation | 39% | 42% | 44% | 0.342 | 23% | 55% | 0.003 |

| BASDAI ⩾4 | 63% | 95% | 90% | <0.001 | 60% | 91% | 0.006 |

| BASDAI ⩾4 and failing NSAID | 55% | 90% | 85% | <0.001 | 51% | 84% | 0.008 |

| BASDAI ⩾4 and failing NSAID + elevated CRP at the time of evaluation | 17% | 55% | 45% | <0.001 | 22% | 8% | 0.085 |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; CRP, C reactive protein; BASDAI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; BASFI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index; BASMI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis metrology index; NSAID, non‐steroidal anti‐ inflammatory drugs. Symptom duration, disease duration since symptoms in years; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease: ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease; anti‐TNF, anti‐tumour necrosis factor alfa therapy

Definite AS and probable AS are defined according to the New York modified criteria.16

Percentages are given, except for continuous data: * mean (SD).

p Values are calculated for the contrast without anti‐TNF at inquiry vs with anti‐TNF at inquiry for all patients.

Table 4 shows that patients who started anti‐TNF therapy, stratified for whether or not they fulfilled the ASAS recommendations,2 tended to have a higher disease activity, more functional impairment, and a worse metrology.

Table 4 BASDAI, BASMI, and BASFI as a function of the fulfilment of the ASAS criteria and the decision to start anti‐TNF treatment.

| No fulfilment of ASAS criteria2 BASDAI <4 or no NSAID failing | Fulfilment of ASAS criteria2 BASDAI ⩾4 and failing NSAID | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without anti‐TNF at query (ccn = 131) | With anti‐TNF at query (ccn = 34) | p Value | Without anti‐TNF at query (ccn = 160) | With anti‐TNF at query (ccn = 187) | p Value | |

| BASDAI | ||||||

| Mean | 3 | 3.7 | 0.041 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 0.028 |

| SEM | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.09 | ||

| BASFI | ||||||

| Mean | 3.1 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 0.005 |

| SEM | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.14 | ||

| BASMI | ||||||

| Mean | 3 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 0.002 |

| SEM | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 0.26 | ||

ASAS, ankylosing spondylitis study group; SEM, standard error of mean; ccn, number of complete cases; BASDAI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; BASFI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index; BASMI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis metrology index; anti‐TNF, anti‐tumour necrosis factor alfa therapy

Different logistic regression models (table 5) to predict the start of anti‐TNF therapy were fitted after backward elimination of the significant variables of table 3. Model 1 was fitted in a subgroup of 121 patients with definite AS who started anti‐TNF treatment within 1 month after the in‐depth profiling. This model revealed that BASDAI, CRP, and HLA‐B27 significantly contributed to the model, with the highest contribution for BASDAI and the lowest contribution for CRP. Model 2 was fitted in the subgroup of patients with probable AS and highlighted the potential added value of the presence of extra‐articular manifestations in this subgroup of patients. Finally, model 3 was fitted in the total population and highlighted the added value of hip involvement, BASFI, male sex, and a definite diagnosis of AS.

Table 5 Result of a logistic regression model to predict the start of anti‐TNF therapy in AS patients.

| Model 1 | |||

| Inclusion: patients with definite AS and a lag time to start anti‐TNF therapy <1 month | |||

| Beta | p Value | OR (95% CI of OR) | |

| Elevated CRP | 1.089 | 0.005 | 2.972 (1.385 to 6.377) |

| Carriage of HLA‐B27 | 1.473 | 0.022 | 4.361 (1.242 to 15.316) |

| BASDAI >4 | 2.051 | 0.001 | 7.774 (2.266 to 26.668) |

| Intercept | −4.800 | 0.000 | .008 |

| Model 2 | |||

| Inclusion: patients with probable AS | |||

| Beta | p Value | OR (95% CI of OR) | |

| Presence of any extra‐articular manifestation | 0.778 | 0.027 | 2.177 (1.093 to 4.338) |

| BASDAI >4 | 1.806 | 0.019 | 6.084 (1.338 to 27.656) |

| Intercept | −3.388 | 0.000 | .034 |

| Model 3 | |||

| Inclusion: all probable and definite AS patients | |||

| Beta | p Value | OR (95% CI of OR) | |

| NYm_Def | 1.056 | 0.001 | 2.876 (1.533 to 5.394) |

| Elevated CRP | 0.736 | 0.000 | 2.087 (1.383 to 3.150) |

| Hip involvement | 0.635 | 0.005 | 1.887 (1.214 to 2.932) |

| HLAB27 | 0.619 | 0.019 | 1.858 (1.106 to 3.121) |

| Male sex | 0.504 | 0.016 | 1.655 (1.098 to 2.493) |

| BASDAI* | 0.228 | 0.001 | 1.256 (1.102 to 1.431) |

| BASFI* | 0.114 | 0.041 | 1.121 (1.005 to 1.251) |

| Intercept | −3.862 | 0.000 | .021 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; BASDAI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; BASFI, Bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index. *BASDAI and BASFI were considered as continuous variables in model 3.

Discussion

This study describes a representative, nationwide sample of Belgian AS patients, followed at different academic and non‐academic centres. Patients were included based on clinical expert diagnosis for AS: 83% of them fulfilled the New York modified criteria for definite AS and 17% of patients were considered as probable AS.16 This clearly shows that, in daily clinical practice, rheumatologists care for a substantial number of AS patients not fulfilling the definite criteria, and this group should receive the attention they merit.16 Not surprisingly, patients with probable AS showed a lower radiological grading of sacroiliac joints on conventional radiographs (table 2). Also, they had a shorter disease duration and it thus might be hypothesised that at least a subgroup of those patients would fulfil the criteria for definite diagnosis if followed up for a longer time (table 2).18 A longer disease duration may account for the more severe disease (higher BASMI,15 more syndesmophytes, bamboo spine, and hip involvement) in patients with definite AS.19,20,21

The profile of definite AS patients was characterised by longstanding, severe, and active disease with a high frequency of comorbidities and important metrological restriction and functional impairment. Also, most patients followed up in rheumatology practice have active disease, which was reflected by a mean BASDAI of 5.3 (SD 2.1) and a mean BASFI of 5.1 (SD 2.5) (table 2).

The high frequency of comorbidities, functional impairment, and active disease despite optimal use of NSAID therapy explains why anti‐TNF therapy was initiated in a large proportion of AS patients. After one year, anti‐TNF therapy was initiated in 44% of the patients with definite AS and in 16% of patients with probable AS. The need for anti‐TNF therapy was previously estimated as 30%10 to 49% (38%–78%).17 While these studies asked the treating rheumatologist whether they thought the patient would need to be treated by a TNF blocker, the present study evaluated the effective start of anti‐TNF therapy under the regulation of reimbursement criteria.

In accordance with ASAS guidelines and Belgian reimbursement criteria, an elevated BASDAI is the main characteristic of patients with probable and definite AS, who start anti‐TNF therapy. More than 90% of patients who started anti‐TNF therapy had a BASDAI ⩾4.17,22 However, other recommendations given by the Belgian reimbursement criteria appeared to add little value to the BASDAI. Although a significant contributor in two of the logistic regression models (table 4, model 1, model 3), the value of an increased CRP seems to be moderate since less than half of the patients who started anti‐TNF therapy had an elevated CRP at the time of the clinical evaluation. The finding that a number of patients who started on anti‐TNF therapy had a normal CRP may be explained by the fact that the reimbursement criteria do not require an elevated CRP when the decision is made to start anti‐TNF therapy (that is, the criteria can be interpreted as requiring an elevated CRP at any time in disease course).

At least two NSAIDs were used in more than 90% of patients with definite AS involved in this cohort. This suggests that trying different NSAIDs is commonly used in the Belgian daily clinical rheumatologists' practice and thus should be recommended before starting anti‐TNF therapy.

A high BASDAI is not the sole criterion on which the physician decides to start anti‐TNF therapy. In both probable and definite AS patients, functional impairment and hip arthritis (table 5) also seemed to be contributing in the decision to start anti‐TNF therapy. Although the presented logistic models require further validation, it is an interesting finding that HLA‐B27 positivity came up in two models (table 5, model 1 and 3). It can be hypothesised that physicians do not decide on HLA‐B27 itself but rather on associated variables, such as earlier onset, comorbidities, or severity of AS.23,24,25,26

One additional important finding in this study was that anti‐TNF therapy was started in a small proportion of patients who did not have a definite diagnosis of AS. Our data suggest that the decision to start anti‐TNF therapy in this subgroup of patients might be justified by the extra‐articular manifestations in half of these patients with probable AS (table 3). This has also been suggested in the logistic regression model (model 2 in table 5) and may suggest that comorbidities contributing to the burden of disease can be independent reasons to start anti‐TNF therapy.27

A few limitations of the study should also be noted. Firstly, the clinical evaluations were performed at a distance from the initiation of the therapy. This time lag was important to avoid the suggestion that patients were encouraged to overestimate their BASDAI in order to fulfil the reimbursement criteria. Although this time lag was limited (with a median of 2 months) changes in disease activity and treatment during this time lag might explain why some patients not fulfilling the reimbursement criteria started anti‐TNF therapy and, inversely, why some patients with a high BASDAI at the clinical evaluation did not receive anti‐TNF therapy. Secondly, a selection towards a more active and severe disease course may have occurred as patients who visited the rheumatologist more frequently may have had a higher probability of being included in this study. Finally, it is important to stress that some AS patients may be treated by generalists or orthopaedic surgeons who have no access to anti‐TNF therapy. These patients were not sampled in this study.

In conclusion, we described a large cross sectional cohort of Belgian AS patients. These data provide important information on clinical and radiological features of the disease. Some patients started anti‐TNF therapy despite not fulfilling the reimbursement criteria and, inversely, other patients did not start anti‐TNF therapy despite fulfilling the recommendations. Recommendations play a major part when starting TNF inhibitors. However, in daily clinical practice other factors, dealing with the expert's opinion and patients' needs and expectations, also contribute to the decision to start TNF blocking therapy.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Schering‐Plough

We thank Hermine Leroy and Jackeline Mercerau of DRC, Belgium and Jean Paul Brasseur of Schering‐Plough Belgium for their assistance in the data management.

We would like to thank Paul O'Grady from Schering‐Plough for his textual comments; and all participating rheumatologists: Ackerman Christine, Badot Valérie, Bastien Pierre, Berghs Hubert, Bonnet Valérie, Bouchez Bernard, Boutsen Yves, Brasseur Jean‐Pierre, Coigne Etienne, Coppens Marleen, Corluy Luk, Cornet Thiry Françoise, Coutellier Patrick, Daens Stéphane, Dall'Armellina Silvano, Daumerie Florence, De Brabanter Griet, De Decker Valérie, Declerck Kathleen, Dhondt Eric, Di Romana Silvana, Docquier Christian, Duckerts rançoise, Dujardin Laurence, Engelbeen Jean‐Paul, Fernandez‐Lopez, Focan‐Henrard Danielle, Fontaine Marie‐Anne, François Dominique, Geusens Piet, Ghyselen Geert, Goemaere Stefan, Gyselbrecht Lieve, Halleux Robert, Heuse Elisabeth, Heylen Alain, Huynen‐Jeugmans Anne‐Marie, Immesoete Carlos, Janssens Xavier, Jardinet Dimitri, Joos Rik, Kruithof Elli, Langenaken Christine, Leens Catherine, Lefèbvre Daniel, Lefèbvre Sophie, Lenaerts Jan, Luyten Frank, Maenaut Kristin, Maertens Martin, Maeyaert Beatrix, Mielants Herman, Mindlin Alain, Moris Muriel, Nzeusseu Adrien, Pater Christian, Peretz Anne, Praet Johan, Qu Jiangang, Raeman Frank, Reychler Ruth, Ronsmans Isabelle, Sarlet Nathalie, Schatteman Godelieve, Sileghem Anne, Stappaerts Geert, Stasse Pierre, Taelman Veerle, Tant Laure, Toussaint Francis, Van Den Bossche Nancy, Van Mullen Xavier, Van Wanghe Paul, Vanden Berghe Marc, Vanden Berghe Marthe, Vanhoof Johan, Verbruggen Ann, Verbruggen Léon, Verdickt Wilfried, Volders Pascale, Vroninks Philippe, Westhovens René,Williame Luc, Wouters Micheline, Zmierczak Hans Georg.

Abbreviations

AS - ankylosing spondylitis

BASDAI - Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

BASFI - Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functionality Index

BASMI - Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index

CRP - C reactive protein

DMARDs - disease modifying antirheumatic drugs

IBD - inflammatory bowel disease

MTX - methotrexate

NSAID - non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

SpA - spondyloarthropathy

TNF - tumour necrosis factor

Footnotes

Bert Vander Cruyssen was supported by a concerted action grant GOA 2001/12051501 from Ghent University, Belgium.

Competing interests: LD and NV were employees of Schering‐Plough during the study. KDV received consulting fees from Shering‐Plough, Centocor, and Wyeth. BVC, CR, HM, AB, JL, and SS received speaker fees from Shering‐Plough.

References

- 1.Dougados M, Dijkmans B, Khan M, Maksymowych W, van der Linden S, Brandt J. Conventional treatments for ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200261(Suppl 3)iii40–iii50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos‐Vargas R, Collantes E, Davis J C, Jr, Dijkmans B.et al ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200665442–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Liu C. Methotrexate for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(3)CD004524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Chen J, Liu C. Sulfasalazine for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(2)CD004800. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Gonzalez‐Lopez L, Garcia‐Gonzalez A, Vazquez‐Del‐Mercado M, Munoz‐Valle J F, Gamez‐Nava J I. Efficacy of methotrexate in ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2004311568–1574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Den Bosch F, Kruithof E, Baeten D, Herssens A, de Keyser F, Mielants H.et al Randomized double‐blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor alpha (infliximab) versus placebo in active spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum 200246755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, Zink A, Alten R, Golder W.et al Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet 20023591187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff M H, Sieper J, Dijkmans B A, Braun J.et al Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006542136–2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt J, Khariouzov A, Listing J, Haibel H, Sorensen H, Grassnickel L.et al Six‐month results of a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of etanercept treatment in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2003481667–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landewe R, Rump B, van der Heijde D, van der Linden S. Which patients with ankylosing spondylitis should be treated with tumour necrosis factor inhibiting therapy? A survey among Dutch rheumatologists. Ann Rheum Dis 200463530–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun J, Davis J, Dougados M, Sieper J, van der Linden S, van der Heijde D. First update of the international ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti‐TNF agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200665316–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun J, Pham T, Sieper J, Davis J, van der Linden S, Dougados M.et al International ASAS consensus statement for the use of anti‐tumour necrosis factor agents in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 200362817–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, Kennedy L G, O'Hea J, Mallorie P.et al A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol 1994212281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy L G, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 1994212286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkinson T R, Mallorie P A, Whitelock H C, Kennedy L G, Garrett S L, Calin A. Defining spinal mobility in ankylosing spondylitis (AS). The Bath AS Metrology Index. J Rheumatol 1994211694–1698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van der Linden S, Valkenburg H A, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 198427361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pham T, Landewe R B, van der Linden S, Dougados M, Sieper J, Braun J.et al An International Study on Starting TNF‐blocking agents in Ankylosing Spondylitis (ISSAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2006651620–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Khan M A, Braun J, Sieper J. How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis 200463535–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robertson L P, Davis M J. A longitudinal study of disease activity and functional status in a hospital cohort of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004431565–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Maghraoui A, Bensabbah R, Bahiri R, Bezza A, Guedira N, Hajjaj‐Hassouni N. Cervical spine involvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol 20032294–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer D G, Park W M, Dick H M, Papazoglou S N, Buchanan W W. Radiological manifestations in 200 patients with ankylosing spondylitis: correlation with clinical features and HLA B27. J Rheumatol 19796305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barkham N, Kong K O, Tennant A, Fraser A, Hensor E, Keenan A M.et al The unmet need for anti‐tumour necrosis factor (anti‐TNF) therapy in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005441277–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saraux A, de Saint‐Pierre V, Baron D, Valls I, Koreichi D, Youinou P.et al The HLA B27 antigen‐spondylarthropathy association. Impact on clinical expression. Rev Rheum Engl Ed 199562487–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vargas‐Alarcon G, Hernandez‐Pacheco G, Zuniga J, Rodriguez‐Perez J M, Perez‐Hernandez N, Rangel C.et al Distribution of HLA‐B alleles in Mexican Amerindian populations. Immunogenetics 200354756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldtkeller E, Khan M A, van der Heijde D, van der Linden S, Braun J. Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA‐B27 negative vs. positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int 20032361–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brewerton D A. The genetics of acute anterior uveitis. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK 1985104(Pt 3)248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boonen A, van der Linden S M. The burden of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol Suppl 2006784–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]