According to the criteria proposed by Ryan and McCarty,1 the diagnosis of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) deposition disease has been based on radiological evidence of the characteristic calcifications and on verification of the synovial liquid of CPPD crystals.

Joint ultrasonography is an innocuous diagnostic technique that is well tolerated by patients, and is the elected method for observing calcified deposits in soft tissues.2

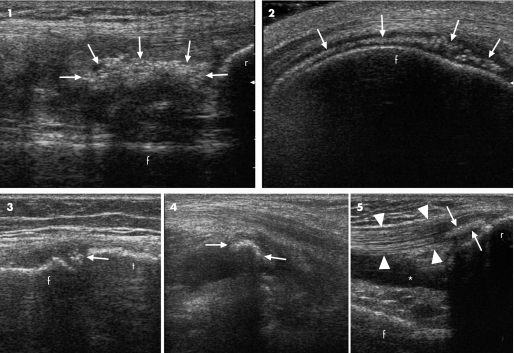

We carried out a longitudinal study, enrolling patients affected with ultrasonographic chondrocalcinosis according to previously proposed criteria3 from a sample of consecutive patients that came to our joint ultrasonography department for gonalgia (fig. 1). A total of 47 patients were identified, of which 14 had joint effusion.

Figure 1 Hyperechoic deposits. Deposits (arrows) are shown that are compatible with calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) calcifications in the context of the synovial membrane (1), hyaline cartilage of the femur (2), meniscus (3), in the sinovial fluid of a Baker's cyst (4) and in the insertional tract of quadricipital tendon (5); arrowheads: quadricipital tendon (purposely appearing hypoechoic at insertion—anisotropic artefact—to better highlight the CPPD deposits). Patterns 1, 4 and 5 are rare and generally occur when a large number of CPPD crystals are present in synovial fluid. In all cases, the deposits do not create an evident posterior shadow unless they reach moderate thickness. In such cases, a partial posterior shadow may be observed (photos 1 and 4). f, femur; r, rotula; t, tibia; *, joint effusion.

The control group was made up of 29 patients who did not present CPPD calcifications in joint tissues affected by osteoarthritis, but who presented joint effusion. All subjects underwent synovial fluid aspiration. The two groups were similar in age.

Ultrasonography examination was performed by an experienced sonographer, blind to previous diagnosis, on an Esaote Technos MP with a 7.5–13 Mhz dedicated linear transducer by the method described elsewhere.2,3 Synovial fluid analysis was performed on wet preparations, within 1 hour after aspiration, by an expert biologist blind to ultrasonographic findings. Each slide was observed under transmitted light microscopy and by compensated polarised microscopy. Crystals with a parallelelipedic or rhomboid shape and weak birefringence with positive elongation were considered to be CPPD crystals.4 We used synovial fluid analysis as the “gold standard” for diagnosis.

Of the 14 patients classified by ultrasonography as affected with chondrocalcinosis, 13 presented with CPPD crystals in synovial liquid, whereas 2 of the 29 patients of the control group were positive for CPPD crystals at microscopic analysis (table 1). Therefore, ultrasonography demonstrated a high specificity (equal to 96.4%) and good sensitivity (equal to 86.7%), with a positive predictive value of 92% and a negative predictive value of 93%.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients and results of the study.

| n | Average age, years (range) | CPPD crystals in synovial fluid | Sensitivity | Specificity | Localisation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meniscus | Cartilage | Other* | ||||||

| Patients classified as affected with CC | 14 | 68 (40–92) | 13 | 86.7% | 96.4% | 14 | 4 | 3 |

| Controls | 29 | 69 (55–84) | 2 | – | – | – | ||

*Mobile deposits in synovial liquid, intratendinous or intrasynovial.

Considering that CPPD crystals could be found in synovial fluid even when characteristic calcifications are not found in joint tissues by traditional radiology,5,6 a sensitivity of 86.7% must be an excellent result. The important data of this study is, however, the high specificity of ultrasonography (96%) in identifying CPPD calcifications.

Other studies have been carried out on the utility of ultrasonography in knee chondrocalcinosis,7,8 but this is the only study that has used the presence of CPPD crystals in synovial liquid as a gold standard. The objective of this study was to evaluate the capacity of ultrasonography to offer a diagnosis, by identifying CPPD calcifications. For this purpose, microscopic synovial fluid analysis, the most widely used examination for the diagnosis of CPPD crystal deposition disease, was used as the gold standard.

Therefore, ultrasonography, as opposed to traditional radiology (ionizing radiation) and to magnetic resonance imaging (still conflicting data),9,10 is the only innocuous examination currently available to the physician that is able to identify CPPD crystal deposits. Considering that CPPD crystal deposition disease frequently has a subclinical course and the patient does not always reach the surgery in an acute stage, it is important for the physician to have a tool at his disposal that permits a diagnosis even in the absence of joint effusion. Moreover, the possibility that ultrasonography can be carried out rapidly during a rheumatology examination places it as a prime tool of diagnostic practice when there is suspected CPPD arthropathy.

Abbreviations

CPPD - calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ryan L M, McCarty D J. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease, pseudogout and articular chondrocalcinosis. In: McCarty DJ, Koopman WJ, eds. Arthritis and Allied Conditions. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 19972103–2125.

- 2.Backhaus M, Burmester G ‐ R, Gerber T, Grassi W, Machold K P, Swen W A.et al Guidelines for musculoskeletal ultrasound in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis 200160641–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frediani B, Filippou G, Falsetti P, Lorenzini S, Baldi F, Acciai C.et al Diagnosis of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal deposition disease: ultrasonographic criteria proposed. Ann Rheum Dis 200564638–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher H, Reginato A. Crystal identification. In: Atlas of synovial fluid analysis and crystal identification. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 199189–102.

- 5.Doherty M, Dieppe P, Watt I. Pyrophosphate arthropathy: a prospective study. Br J Rheumatol 199332189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doherty M, Dieppe P A. Acute pseudogout: “crystal shedding” or acute crystallization? Arthritis Rheum 198124954–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sofka C M, Adler R S, Cordasco F A. Ultrasound diagnosis of chondrocalcinosis in the knee. Skeletal Radiol 20023143–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foldes K. Knee chondrocalcinosis. An ultrasonographic study of the hyaline cartilage. J Clin Imag 200226194–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abreu M, Johnson K, Chung C B, De Lima J E, Jr, Trudell D, Terkeltaub R.et al Calcification in calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystalline deposits in the knee: anatomic, radiographic, MR imaging, and histologic study in cadavers. Skeletal Radiol 200433392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suan J C, Chhem R K, Gati J S, Norley C J, Holdsworth D W. 4 T MRI of chondrocalcinosis in combination with three‐dimensional CT, radiography, and arthroscopy: a report of three cases. Skeletal Radiol 200534714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]