Infestation of humans or other vertebrates by dipterous fly larvae is called myiasis. Larvae can infest several parts of the body, most commonly cutaneous tissue. Occasionally, infestation of ocular tissue could occur resulting in internal ocular or external (conjunctival or eyelid) ophthalmomyiasis.1,2,3,4,5 The most common species causing external ophthalmomyiasis in the US is the sheep botfly, Oestrus ovis.6 The human botfly, D hominis, is the primary cause of cutaneous myiasis in Central and South America, but only rarely causes external ophthalmomyiasis.1,2,5

Several case reports of external ophthalmomyiasis owing to D hominis occurring in the US exist in the literature; however, every case reports a history of recent travel to tropical American countries.1 To our knowledge, there have been no previously identified cases of external ophthalmomyiasis secondary to D hominis originating in the US.

Case report

A 5‐year‐old girl presented with a 10‐day history of pain and swelling of her left upper eyelid. Her symptoms began while at the beach in Fort Walton Beach, Florida, USA. She had recently been examined by an external ophthalmologist who reportedly saw a larva protrude from an aperture in the eyelid. Ocular examination revealed an excoriated, erythematous area within 2 mm of the left upper lid margin (fig 1). On closer examination, a tiny aperture producing a clear discharge was noted within the lesion. The patient was taken to the operating room for exploration. A single larva was identified and removed in total.

Figure 1 External ophthalmomyiasis. Note the tiny aperture producing clear discharge superior to the left upper lid margin. Inset: macroscopical view of human botfly larva, Dermatobia hominis. The rostral end of the larva is covered with several rows of thorn‐like spines.

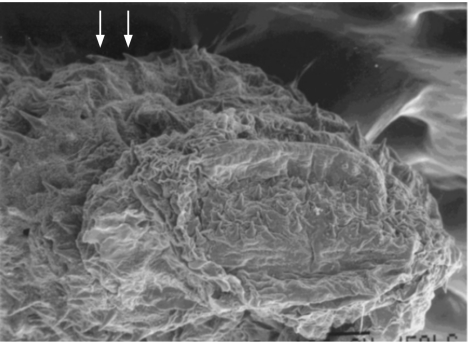

On gross examination, the larva measured 5.5 mm×1 mm (fig 1, inset). Microscopic examination revealed a larva with a broad rostral end exhibiting two rows of backward‐directed, thorn‐shaped spines (fig 2). Based on its size, shape and surface characteristics, the larva was identified as a first‐stage larva of the fly D hominis.

Figure 2 Scanning electron micrograph of Dermatobia hominis showing the numerous backward‐directed spines (arrows).

Comment

D hominis is the most common cause of cutaneous myiasis. However, external ophthalmomyiasis encompasses <5% of all cutaneous sites.1,5 The human botfly is not indigenous to North America. However, there are several dozen reports in the literature of D hominis ophthalmomyiasis occurring in the US among those who have travelled to Central and South America. A recent review by Denion and co‐workers2 describes eight of nine cases of external ophthalmomyiasis owing to D hominis originating in tropical American countries. One case presumably originated in New York3; however, diagnostic inaccuracy was suspected given the lack of defining features required to identify this species.

Reports of myiasis caused by D hominis are appearing more frequently because of increasing international travel.1,2 Currently, a history of travel to or residency in a tropical American country is needed to raise clinical suspicion of dermatobiasis.2 Pathological analysis and identification of the larva and therefore appropriate diagnosis cannot be achieved if the species is not first suspected. We are presently unaware of previous reports of external ophthalmomyiasis caused by D hominis found in the US that do not include a history of foreign travel. Thus, our case, originating in Fort Walton Beach, could imply migration of a species. Furthermore, Fort Walton is located at a latitude of 30.4 N, which is just north of what is considered tropical America (18 S to 25 N).5 Consequently, Fort Walton's subtropical climate (www.britannica.com) could be compatible with life for D hominis, especially in light of changing global temperatures.7 Therefore, it is plausible that if the species were brought into the area by travellers from endemic regions, the botfly could have been able to survive and adapt to this climate. Certainly, there needs to be more cases to support these theories. This case highlights the need to recognise this species as an aetiological agent causing external ophthalmomyiasis in cases originating in North America.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Bangsgaard R, Holst B, Krogh E.et al Palpebral myiasis in a Danish traveler caused by the human bot fly (Dermatobia hominis). Acta Ophthalmol Scand 200078487–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denion E, Dalens P H, Couppie P.et al External ophthalmomyiasis caused by Dermatobia hominis. A retrospective study of nine cases and a review of the literature. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 200482576–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emborsky M E, Faden H. Ophthalmomyiasis in a child. Pediatr Infect Dis J 20022182–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampson C E, MacGuire J, Eriksson E. Botfly myiasis: case report and brief review. Ann Plast Surg 200146150–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilhelmus K R. Myiasis palpebrarum. Am J Ophthalmol 1986101496–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reigold W J, Robin J B, Leipa D.et al Oestrus ovis opthalmomyiasis externa. Am J Ophthalmol 1984977–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hance T, van Baaren J, Vernon P.et al Impact of extreme temperatures on parasitoids in a climate change perspective. Annu Rev Entomol 200752107–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]