Abstract

Objective

To investigate the fluctuations in intraocular pressure during the day and to see if these are associated with changes in corneal shape and in the patterns of ocular aberrations.

Methods

Intraocular pressure, corneal curvature, refractive error, spherical equivalent and aberrations (defocus (sphere); cylinder (astigmatism); coma, trefoil and third order spherical aberration) were measured in 17 healthy subjects three times during the day. The first measurement was made between 9:00 and 9:30, the second at midday (12:30–13:00) and the third in the afternoon (17:00–17:30). Aberrations, corneal shape, refractive error and pupil size (for which correction was made) were measured with an Irx3 Dynamic Wavefront Aberrometer. Intraocular pressures were measured using a non‐contact tonometer (Cambridge Instruments Inc.) and calibrated with the Goldmann applanation tonometer.

Results

Variations in intraocular pressures were unrelated to age or refractive error. Statistically significant differences in intraocular pressure between morning and midday as well as between midday and afternoon were found. Intraocular pressure variations between midday and afternoon were associated with changes in spherical equivalent, corneal radius of curvature and aberrations (defocus, cylinder, coma, trefoil and spherical aberration) over the same time period. Aberration patterns varied between individuals, and no association was found between two eyes of the same subject.

Conclusions

Changes in intraocular pressure have no noticeable effect on image quality. This could be because the eye has a compensating mechanism to correct for any effect of ocular dynamics on corneal shape and refractive status. Such a mechanism may also affect the pattern of aberrations or it may be that aberrations alter in a way that offsets any potentially detrimental effects of intraocular pressure change on the retinal image. Variations in patterns of aberrations and how they may be related to ocular dynamics need to be investigated further before attempts at correction are made.

Any image produced by an optical system, including that of the eye, will suffer from the effect of aberrations. In terms of correcting the optics of the eye, refractive errors are considered to be the most important optical defects: for every change of 0.1 mm in anterior corneal radius there is a difference of 0.6 dioptres (D) in the refractive power of the eye.1 Higher order aberrations become of interest only once refractive errors are corrected. In the eye, the most important aberrations arise from the geometry of the optical surfaces of the cornea and crystalline lens.

Calculation of aberrations is complicated and can be arduous. Until recently, aberrations were considered primarily important in lens design rather than for improving the image quality of the eye. In the past few years there has been much progress in the area of ocular aberrations and in improving methods for their numerical calculation. Instruments for measurement of wavefront aberrations in the living eye have become available for clinical applications, and correction of errors has been advanced with the use of wavefront technology.2 However, these relatively new methods for measuring aberrations leave many important questions for the clinician. The relative levels of aberrations in the general population as well as how these are affected by factors such as age, refractive error, pupil size, accommodation and refractive surgery are not known. The full extent to which aberrations affect spatial visual performance in the living eye is also a source of uncertainty.

Individual eyes have varying types and levels of aberrations. It is uncertain whether or not the full extent of these can be corrected and whether this would lead to a significant enhancement of vision beyond what nature has designed (so‐called “super‐vision”).3 More importantly, parameters that affect the type and level of aberrations (shapes of optical surface, distances between elements) can change throughout the day with physiological variations in intraocular pressure (IOP) and with accommodation.

It has been shown that IOP exhibits diurnal variations.4,5,6 It was reported in some studies to be highest in the early morning and lowest in the evening, with a fluctuation of 4–6 mm Hg.4,5 However, Henkind et al6 found, in his study of 11 normal subjects, that the lowest IOP generally occurred in the early morning hours (2:00 to 4:00) and that variations in IOP over a 24 h period were significant. They recorded short‐term fluctuations of 5–9 mm Hg in 1 h and of 3–4 mm Hg over 20 min sampling periods. Variations in IOP observed in humans can lead to slight alterations in corneal curvature, causing a change in its dioptric power and in axial length of the eye to an extent that could affect visual quality.7 It is feasible that this could also have an effect on ocular aberrations.

Yet, in spite of variations in IOP during the day and the potential effect on the corneal shape, there is no noted change in visual acuity. It has been suggested,8 and supported by models, that slight variations in corneal shape may be corrected by a stabilising action of the limbus.9,10 This mechanism would also have an effect on the pattern of aberrations. This study sought to measure how IOP varies during the day and whether this was correlated to any changes in corneal curvature and to daily changes in type and level of aberrations.

Methods

Seventeen healthy adults (11 males and 6 females) with no ocular pathology agreed to participate in this study. Spherical refractive errors in the subject group were less than ±3.5 D and, in all but one case, astigmatic errors were <1.5 D. (One subject had an astigmatic error of just under 2 D.) The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Filter Committee of the University of Ulster, and informed consent was obtained in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. For each subject, measurement of IOP, refractive status (refractive error, spherical equivalent), corneal radii of curvature and monochromatic aberrations (defocus (sphere); cylinder (astigmatism); coma, trefoil and third order spherical aberration) were made at three specific times throughout the day. The first set of measurements was conducted in the morning (9:30–10:00), the second at midday (12:30–13:00) and the third in the late afternoon (17:00–17:30).

Refractive error, spherical equivalent, corneal radii of curvature for the principal meridians and the monochromatic aberrations were measured for both eyes of each subject using an Irx3 Dynamic Wavefront Aberrometer (Imagine Eyes, Orsay, France). This instrument has a Shack–Hartmann type sensor, with a maximum available area of analysis and spatial resolution at the pupil plane of 7.2×7.2 mm2 and 230 μm, respectively. The wavelength used is 780 nm. All measurements were performed without any dilating drugs. The maximum natural pupil diameter (between 3.3 and 6.7 mm) was measured using the aberrometer, which makes an adjustment for the size of the pupil so that any variations do not affect the measurement of aberrations.

From the values at the two principal meridians, the instrument calculates the average radius of curvature of the cornea. The aberrometer also determines the spherical error that best matches the measured wavefront error (the spherical equivalent). Although the cornea has a degree of toricity, preliminary analysis, which considered each principal meridian separately (ie, how the respective radii vary during the day and how they relate to IOP), did not produce any differences from the results obtained using the average radii of curvature. For each eye, the refraction and ocular aberrations were obtained in the unaccommodated (distant focus) state. Following wavefront and corneal shape assessment, IOP was measured using a non‐contact tonometer (Cambridge Instruments Inc.)and was checked and calibrated with the Goldmann applanation tonometer. Measurements obtained from the two instruments varied within ±1 mm Hg. Measurements were repeated 2 months later in six of the subjects to check repeatability. The statistical analysis of results (two‐tailed t test, significance level of p⩽0.05) was conducted using Statistica Software (5.1 StatSoft, 1998).

Results

IOP variations were observed during the day in all subjects. There were several different trends in these variations, and no symmetry was found between left and right eyes of the same subject (table 1). The differences in IOP between morning and midday were statistically significant (p<0.03) and varied up to a maximum of 6.5 mm Hg. The differences in IOP between midday and afternoon were also statistically significant (p<0.01) with a maximum difference of 8.3 mm Hg. Values of IOP between morning and afternoon measurements and associations in IOP with age, refractive error or corneal radius were not found to be statistically significant.

Table 1 The level of the intraocular pressure and average corneal radii of curvature in left and right eyes measured at three specified times during the day.

| Age | eye | Morning 9:30 | Noon 12:30 | Afternoon 17:30 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOP mm Hg | R0 mm | IOP mm Hg | R1 mm | IOP mm Hg | R2 mm | |||

| 1 | 29 | OS | 18.0 | 7.97 | 16.0 | 7.94 | 16.0 | 7.74 |

| OD | 14.0 | 7.68 | 14.0 | 7.84 | 13.0 | 7.84 | ||

| 2 | 44 | OS | 21.5 | 8.09 | 22.0 | 7.84 | 13.7 | 7.89 |

| OD | 19.0 | 8.17 | 20.3 | 7.91 | 16.4 | 8.14 | ||

| 3 | 59 | OS | 18.5 | 8.63 | 24.0 | 8.62 | 21.3 | 8.63 |

| OD | 18.0 | 8.37 | 24.5 | 8.63 | 19.7 | 8.43 | ||

| 4 | 42 | OS | 23.5 | 8.25 | 21.5 | 8.29 | 17.3 | 7.93 |

| OD | 20.0 | 8.16 | 18.0 | 7.98 | 23.5 | 8.24 | ||

| 5 | 25 | OS | 14.5 | 8.54 | 18.0 | 8.41 | 18.0 | 8.28 |

| OD | 15.0 | 8.46 | 17.0 | 8.63 | 19.0 | 8.44 | ||

| 6 | 42 | OS | 14.0 | 8.43 | 12.0 | 8.34 | 14.0 | 8.34 |

| OD | 15.0 | 8.38 | 12.0 | 8.42 | 13.0 | 8.36 | ||

| 7 | 62 | OS | 14.7 | 7.72 | 16.0 | 7.63 | 13.0 | 7.74 |

| OD | 13.0 | 7.61 | 14.0 | 7.48 | 9.5 | 7.64 | ||

| 8 | 37 | OS | 13.0 | 8.28 | 12.5 | 8.59 | 14.0 | 8.52 |

| OD | 16.0 | 8.72 | 17.0 | 8.80 | 17.0 | 8.68 | ||

| 9 | 47 | OS | 12.0 | 8.12 | 17.0 | 7.94 | 17.0 | 8.04 |

| OD | 12.0 | 8.47 | 15.0 | 8.02 | 17.0 | 8.02 | ||

| 10 | 25 | OS | 15.0 | 7.96 | 15.0 | 8.20 | 14.0 | 7.98 |

| OD | 15.0 | 8.11 | 13.0 | 8.37 | 13.0 | 7.96 | ||

| 11 | 42 | OS | 16.0 | 8.39 | 17.0 | 8.27 | 17.0 | 8.21 |

| OD | 17.0 | 8.41 | 20.0 | 8.94 | 18.0 | 8.71 | ||

| 12 | 24 | OS | 14.0 | 8.50 | 16.0 | 8.36 | 14.0 | 8.41 |

| OD | 14.0 | 8.33 | 16.0 | 8.42 | 13.0 | 8.30 | ||

| 13 | 57 | OS | 22.0 | 7.78 | 26.0 | 7.77 | 26.0 | 7.80 |

| OD | 24.0 | 7.88 | 21.3 | 7.50 | 20.0 | 7.78 | ||

| 14 | 35 | OS | 14.0 | 8.03 | 14.0 | 8.17 | 12.0 | 8.00 |

| OD | 14.0 | 8.25 | 11.0 | 8.12 | 10.0 | 8.21 | ||

| 15 | 23 | OS | 17.0 | 7.78 | 18.0 | 7.94 | 16.0 | 7.84 |

| OD | 19.0 | 7.96 | 20.0 | 7.80 | 17.0 | 7.68 | ||

| 16 | 30 | OS | 11.0 | 9.05 | 13.0 | 8.98 | 12.0 | 8.90 |

| OD | 10.0 | 9.07 | 13.0 | 9.12 | 11.0 | 9.12 | ||

| 17 | 35 | OS | 17.0 | 8.34 | 18.0 | 8.17 | 18.0 | 8.40 |

| OD | 18.0 | 8.29 | 19.0 | 8.48 | 16.0 | 8.32 | ||

IOP, intraocular pressure; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; R0, average radius of curvature in the morning; R1, average radius of curvature at noon; R2, average radius of curvature in the afternoon.

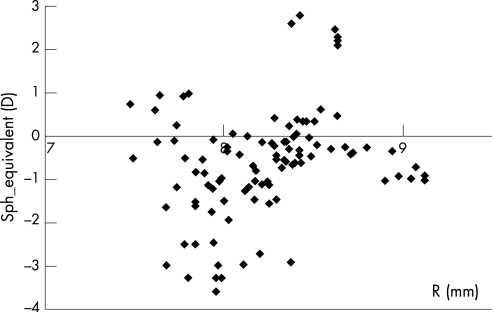

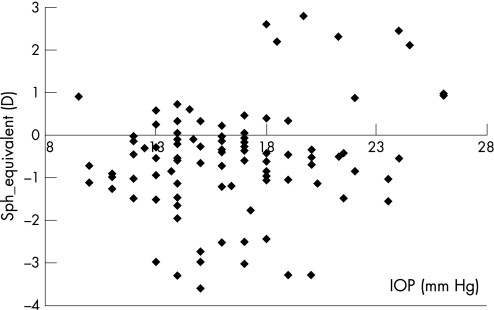

Changes in corneal radius of curvature between morning and midday varied from 0.01 to 0.53 mm. Between midday and afternoon, the range of variations was 0.01–0.41 mm. The measured changes in spherical equivalent were found to vary from 0 to 0.86 D between morning and midday and from 0 to 0.71 D between midday and afternoon. No trends were found between the spherical equivalent and the corneal radius (fig 1) nor between the spherical equivalent and IOP (fig 2). There were no statistically significant associations between the spherical equivalent and any of the following: cylinder, coma, trefoil and third order spherical aberration.

Figure 1 The spherical equivalent (D) plotted against the radius of curvature of the cornea, R (mm).

Figure 2 The spherical equivalent (D) plotted against the intraocular pressure, IOP (mm Hg).

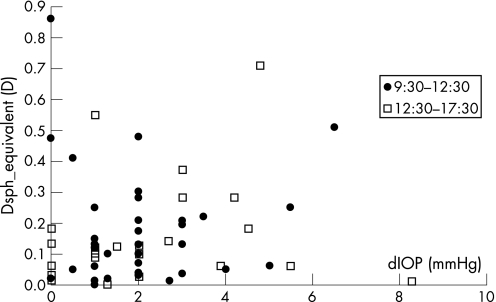

Changes in spherical equivalent between the midday measurements and those taken in the late afternoon showed a statistically significant association, with respective changes in IOP (p = 0.013) (fig 3). Changes in IOP and spherical equivalent measurements taken in the morning and at midday were not statistically significant (fig 3).

Figure 3 The absolute change in spherical equivalent (D) plotted against the absolute change in intraocular pressure (mm Hg) for measurements taken between morning and midday (filled circles) and midday and afternoon (open squares).

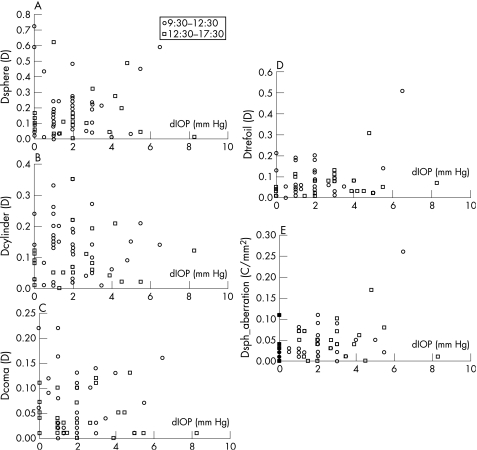

Whilst levels of the various primary aberrations did not show any overall trend with IOP, there was a statistically significant relationship between changes in the primary aberrations and changes in IOP between midday and afternoon measurements (table 2). No such association was found between morning and midday measurements. Similarly, changes in corneal radius of curvature and changes in IOP were statistically significant (p<0.02) for the afternoon time period (measurements between midday and afternoon) but not between morning and midday.

Table 2 The variations in magnitude of aberrations between morning–midday and midday–afternoon and the p values (t test) between changes in intraocular pressure and in each respective aberration (fig 4).

| Aberration type | Morning–midday | Midday–afternoon | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variation | p Value | Variation | p Value | |

| Defocus (sphere) (fig 4A) | −0.7÷0.6 D | >0.05 | −0.5÷0.6 D | 0.0134 |

| Cylinder (astigmatism) (fig 4B) | −0.25÷0.35 D | >0.05 | −0.2÷0.2 D | 0.0131 |

| Coma (fig 4C) | −0.2÷0.2 D mm–1 | >0.05 | −0.1÷0.1 D mm–1 | 0.0125 |

| Trefoil (fig 4D) | −0.50÷0.2 D mm–1 | >0.05 | −0.1÷0.35 D mm–1 | 0.031 |

| Spherical aberration (fig 4E) | −0.25÷0.1 D mm–2 | >0.05 | −0.1÷0.2 D mm–2 | 0.0124 |

Figure 4 The absolute change in primary aberrations: (A) defocus (sphere; D, (B) cylinder (astigmatism; D), (C) coma (D mm–1), (D) trefoil (D mm) and (E) spherical aberration (D/mm–2) plotted against the absolute change in intraocular pressure (mm Hg) for measurements taken between morning and midday (circles) and midday and afternoon (squares).

There was no trend or statistically significant relationship between level of change in aberrations and that in IOP measured between morning and afternoon periods. No association was found between the aberration patterns of the left and right eyes of the same subject. Repeatability of IOP measurements was within ±2 mm Hg, and the same trends in daily variations, found in the initial measurements, were reproduced for all subjects retested. Changes in corneal radii of curvature and spherical equivalent varied between 0.02 and 0.4 mm and between 0.01 and 0.85 D, respectively, between initial and repeat readings. The magnitude of aberrations between initial and repeat measurements varied as follows: defocus (sphere), 0.1–0.69 D; cylinder (astigmatism), 0–0.49 D; coma, 0.01–0.36 D mm–1; trefoil, 0.02–0.15 D mm–1; and third order spherical aberration, 0–0.32 D mm–2.

Discussion

It has been shown that IOP exhibits variations during the day.4,5,6,11,12,13 As this study was concerned with measuring the effect of IOP change on factors that may influence image quality, it was limited to the waking hours, when vision is operative. Hence, it was not possible to determine the full range of variations that may occur over 24 h, nor to detect changes of the magnitude that may occur at the transition between a light and dark period.12,13 This notwithstanding, the results of this study confirm previous findings and show several trends in daily fluctuations of IOP. Variations in IOP between morning and midday, and midday and afternoon were found to be statistically significant, whereas no significant difference was found between morning and afternoon values. Statistically significant associations between the changes in IOP and variations in corneal radius as well as between the changes in IOP and variations in spherical equivalent were found between midday and afternoon measurements only. This could be because the longer time period and greater variation in readings between the midday and afternoon measurements, compared with the period between morning and midday measurements, made it possible to measure a statistically significant change. It could also signify that the afternoon period is one of greater change in ocular dynamics.

It has been reported that lid pressure can influence the shape of the cornea.14 If tension from the eyelids did indeed exert some moulding effect on the cornea, this should be most notable after a period of lid closure and hence have the greatest impact on measurements made in the morning. This was not found in this study. Previous investigations that have considered the effect of lid tension on corneal shape have not concurred in their conclusions.14,15

Changes in primary aberrations were found throughout the day. The pattern varied with individuals, and no notable trends or associations with refractive status, corneal radius of curvature or age were observed. The magnitude of aberrations could not be correlated with values of IOP, but variations in all measured aberrations changed significantly with IOP between midday and afternoon. This could indicate that changes in aberrations are an additional form of compensating for changes in IOP in order to stabilise vision.

No statistically significant association between changes in aberrations and changes in spherical equivalent with changes in corneal radius was found. Correlations between corneal radius and refractive error have been reported in some studies16,17,18,19 but not in others.20,21,22

The results of this study show that generalising the pattern of aberrations may not be possible given the range of individual variations. This supports the findings of previous studies that showed that the aberrations of the eye differ greatly from subject to subject.23,24,25 Even for a given individual there is no consistency in the pattern of aberrations between the two eyes: some studies have reported correlations between right and left eyes,24,25,26,27,28,29 but findings from other studies have not supported this.23,30

Small changes in aberrations can occur over short time periods (seconds) because of fluctuations in accommodation,31,32 changes in pupil diameter33,34 or variations in thickness of the corneal tear film between blinks.35,36,37 The nature and extent of influence of these factors on aberrations and on their changes remain unclear. It should be noted that the results of this study are pertinent to monochromatic aberrations at 780 nm, the source wavelength. Whether the findings could be extended to apply to other wavelengths is not known. Studies that have investigated the effect of aberrations on image quality have not concurred in their findings.38,39,40 Ultimately the quality of the optics of the eye is diffraction limited; the size of the pupil, particularly when constricted, should always be taken into account when assessing image quality.

Conclusions

The changes in IOP during the day follow variations that could not be correlated with age or refractive error. Statistically significant variations in IOP were found to occur between morning and midday, and midday and afternoon, but only the latter had significant associations with changes in corneal radius of curvature, spherical equivalent and aberrations. This may indicate that there is some effect of ocular dynamics on the shape of the eye and on the pattern of aberrations. These dynamic changes in IOP have no noticeable effect on vision. The dynamics of the eyeball and the subsequent effect on ocular aberrations need to be better understood before attempts at correction are made.

Abbreviations

IOP - intraocular pressure

Footnotes

Competing interests. None declared.

References

- 1.Bennett A G, Rabbetts R B. Proposals for new reduced and schematic eyes. Ophthal Physiol Opt 19899228–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roorda A. A review of basic wavefront optics. In: Krueger R, Applegate R, MacRae S, eds. Wavefront customized visual correction. the quest for super vision II Thorofare: SLACK Inc, 20049–19.

- 3.Thibos L N. The prospects for perfect vision. J Refract Surg 200016540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davson H. The aqueous humour and the intraocular pressure. In: Davson H, ed. Physiology of the eye. London: Macmillan Academic and Professional Ltd, 19903–65.

- 5.Fatt I, Weissman B A. The intaocular pressure. In: Fatt I, Weissman BA, eds. Physiology of the eye. An introduction to the vegetative functions Stoneham: Butterworth‐Heinemann, 199231–76.

- 6.Henkind P, Leitman M, Weitzman E. The diurnal curve in man: new observation. Invest Opthalmol 197312705–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asejczyk M.Examination of influence of the eye globe's elastic properties on the eye's refractive properties [PhD thesis]. Poland: Wroclaw University of Technology, Institute of Physics, 2004

- 8.Maurice D M. Mechanics of the cornea. In: Cavanagh HD, ed. The cornea. New York: Raven Press, 1988187–193.

- 9.Asejczyk‐Widlicka M, Srodka W, Kasprzak H.et al Influence of IOP on geometrical properties of a linear model of the eyeball. Effect of optical self‐adjustment. Optics 2004115517–524. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asejczyk‐Widlicka M, Srodka W, Kasprzak H.et al Modelling the elastic properties of the anterior eye and their contribution to maintenance of image quality: the role of the limbus. Eye. Published Online First: 23 June 2006, doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702464 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.David R, Zangwill L, Briscoe D.et al Diurnal intraocular pressure variations: an analysis of 690 diurnal curves. Br J Ophthalmol 199276280–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J H K, Kripke D F, Hoffman R E.et al Nocturnal elevation of intraocular pressure in young adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1998392707–2712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J H K, Kripke D F, Twa M D.et al Twenty‐four‐hour pattern on intraocular pressure in the aging population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999402912–2917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman D M, Grierson J W. The lids influence on corneal shape. Cornea 200019336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vihlen F S, Wilson G. The relation between eyelid tension, corneal toricity and age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1983241367–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carney L G, Mainstone J C, Henderson B A. Corneal topography and myopia: a cross‐section study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 199738311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goss D A, Van Veen H G, Rainey B B.et al Ocular components measured by keratometry, phakometry, and ultrasonography in emmetropic and myopic optometry students. Optom Vis Sci 199774489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strang N C, Schmid K L, Carney L G. Hyperopia is predominantly axial in nature. Curr Eye Res 199817380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budak K, Khater T T, Friedman N J.et al Evaluation of relationship among refractive and topographic parameters. J Cataract Refract Surg 199925814–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorsby A, Leary G A. A longitudinal study of refraction and its components during growth. Spec Rep Ser Med Res Counc 19693091–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mainstone J C, Carney L G, Anderson C R.et al Corneal shape in hyperopia. Clin Exper Optom 199881131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horner D G, Soni P S, Vyas N.et al Longitudinal changes in corneal asphericity in myopia. Optom Vis Sci 200077198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howland H C, Howland B. A subjective method for the measurements of monochromatic aberrations of the eye. J Opt Soc Am 1977671508–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Charman W N. Wavefront aberrations of the eye: a review. Optom Vision Sci 199168574–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter J, Guirao A, Cox I G.et al Monochromatic aberrations of the human eye in a large population. J Opt Soc Am (A) Opt Image Sci Vis 2001181793–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang J, Grimm B, Goelz S.et al Objective measurement of wave aberrations of the human eye with the use of a Hartmann–Shack wave‐front sensor. J Opt Soc Am (A) Opt Image Sci Vis 1994111949–1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang J, Williams D R. Aberrations and retinal image quality of the normal human eye. J Opt Soc Am (A) Opt Image Sci Vis 1997142873–2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thibos L N, Hong X, Bradley A.et al Statistical variation of the aberration structure and image quality in a normal population of healthy eyes. J Opt Soc Am (A) Opt Image Sci Vis 2002192329–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng X, Bradley A, Hong X.et al Relationship between refractive error and monochromatic aberrations of the eye. Optom Vis Sci 20038043–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcos S, Burns S A. On the symmetry between eyes of wavefront aberration and cone directionality. Vision Res 2000402437–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charman W N, Heron G. Fluctuations in accommodation: a review. Ophthal Physiol Opt 19888153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofer H J, Artal P, Aragon J L.et al Temporal characteristics of the eye's aberrations. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 199940(Suppl)S365 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charman W N, Chateau N. The prospects for super‐acuity: limits to visual performance after correction of monochromatic aberration: a review. Ophthal Physiol Opt 200323479–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ginis H S, Plainis S, Pallikaris A. Variability of wavefront aberration measurements in small pupil size using a clinical Shack–Hartmann aberrometer. BMC Ophthalmology 200441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albarran C, Pons A M, Lorente A.et al Influence of the tear film on the optical quality of the eye. Contact Lens Ant Eye 199720129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thibos L N, Hong X. Clinical applications of the Shack–Hartmann aberrometer. Optom Vis Sci 199976817–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tutt R, Bradley A, Begley C.et al Optical and visual impact of tear break‐up in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2000414117–4123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Charman W N, Jennings J A M. The optical quality of the monochromatic retinal image as a function of focus. Br J Physiol Opt 197631119–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcos S, Moreno E, Navarro R. The depth of field of the human eye from objective and subjective measurements. Vision Res 1999392039–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcos S, Burns S, Moreno‐Barriusop E.et al A new approach to the study of ocular chromatic aberrations. Vision Res 1999394309–4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]