Abstract

Background

Ewing's sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour (pPNET) are now regarded as two morphological ends of a spectrum of neoplasms, characterised by a t(11;22) or other related chromosomal translocation involving the EWS gene on chromosome 22 and referred to as Ewing family of tumours (EFTs). EFTs are extremely rare in the vulva and vagina, a review of the literature revealing only 13 previously reported possible cases, most of which have not had molecular confirmation. In this study, four new cases of EFTs involving the vulva (three cases) or vagina (one case) are reported.

Results

The tumours occurred in women aged 19, 20, 30 and 40 years and ranged in size from 3 to 8 cm. Morphologically, all neoplasms had a lobulated architecture and were composed of solid aggregates of cells. In one case, occasional rosettes were formed. In all the tumours, there was diffuse membranous staining with CD99; nuclear positivity with FLI‐1 was present in two cases. Three cases were focally positive with the broad‐spectrum cytokeratin AE1/3, all were diffusely positive with vimentin and all were desmin negative. In two cases, a t(11;22) (q24;q12) (EWSR1‐FLI‐1) chromosomal translocation was demonstrated by reverse transcriptase‐PCR (one case) and fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) (one case), and in another case a rearrangement of the EWSR1 gene on chromosome 22 was demonstrated by FISH. In the other case, a variety of molecular studies did not reveal a translocation involving the EWS gene but this tumour, on the balance of probability, is still considered to represent a neoplasm in the EFTs. Follow‐up in two cases revealed that one patient developed pulmonary metastasis and died and another is alive without disease at 12 months.

Conclusions

This report expands the published literature regarding EFTs involving the vulva and vagina and stresses the importance of molecular techniques in firmly establishing the diagnosis, especially when these neoplasms arise at unusual sites.

Although traditionally classified as separate entities, Ewing's sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour (pPNET) are now regarded as belonging to a spectrum of neoplasms exhibiting neuroectodermal differentiation and collectively referred to as Ewing family of tumours (EFTs).1,2,3,4 This is because >90% of these neoplasms harbour the same t(11;22) (q24;q12) chromosomal translocation, which results in the EWSR1‐FLI‐1 fusion protein. Most of the remaining cases have variant translocations involving the EWSR1 gene on chromosome region 22q12, such as t(21;22) (q22;q12), t(7;22) (p22;q12) or t(2;22) (q33;q12) resulting in different fusion proteins, EWSR1‐ERG, EWSR1‐ETV1 or EWSR1‐FEV, respectively.1,2 Although the term Ewing's sarcoma is still used by many for those tumours that lack evidence of neuroectodermal differentiation by light microscopy, immunohistochemical analysis or electron microscopy and the term pPNET for those neoplasms that exhibit neuroectodermal differentiation, in this study we will use the term EFTs to encompass the spectrum of neoplasms.

EFTs most commonly arise in young patients (the peak incidence is in the 20s) with a slight male predilection and occur at a variety of bone and soft tissue sites.1,2,3,4 Most extraosseous neoplasms involve the soft tissues of the chest wall, pelvis, paravertebral region and lower extremities. The majority of these neoplasms are composed of solid sheets of primitive undifferentiated “small round blue cells”, corresponding histologically to Ewing's sarcoma, although rosettes are seen in more differentiated tumours, which histologically correspond to pPNETs. Previously, most of the undifferentiated neoplasms were essentially diagnosed after the exclusion of other “small round cell tumours”, which also most commonly occur at a young age. However, in recent years CD99 and FLI‐1 antibodies have been demonstrated to be extremely useful in diagnosis and are positive in a large majority of cases.5,6

EFTs have rarely been described in the vulva and vagina and some of the reported cases have not had molecular or even immunohistochemical—that is, CD99 or FLI‐1—confirmation.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 In this report, we describe four new cases of EFTs involving the vulva or vagina, all with appropriate immunohistochemical staining patterns and three with molecular confirmation. In doing so, we undertake a review of the previously reported cases of EFTs involving these sites and discuss the differential diagnosis of these neoplasms, which rarely involve the lower part of the female genital tract. We stress the importance of molecular techniques in definitively diagnosing a neoplasm in the EFTs, especially when arising at unusual sites.

Materials and methods

The four cases were derived from the pathology archives of the institutions to which the authors are affiliated.

H&E‐stained sections were reviewed and immunohistochemical analysis for CD99 (Dako, Ely, UK), FLI‐1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA), vimentin (Dako), AE1/3 (Dako) and desmin (Dako) was performed in all cases using standard methods. An automated staining machine (Ventana Nexes, Strasbourg, France) was used to carry out the staining using a peroxidase visualisation method. Diaminobenzidine was used as the chromogen and sections were counterstained using haematoxylin (Ventana). Positive and negative controls were used. The positive controls comprised a neoplasm in the EFTs for CD99 and FLI‐1, a uterine leiomyoma for vimentin and desmin and a colonic adenocarcinoma for AE1/3. For negative controls, the primary antibody was omitted and replaced with immunoglobulin (IgG1; Dako) at an equivalent concentration. In all cases, as part of the original investigation, other immunohistochemical stains were also performed and in one case (discussed in Immunohistochemical findings section) a particularly extensive panel of markers was performed.

Molecular studies

In two cases, reverse transcriptase‐PCR (RT‐PCR) for EWSR1‐FLI‐1 was carried out on formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐wax‐embedded tissue, as previously described.19 In one of these cases, fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) analysis for EWS‐FLI‐1 and RT‐PCR for EWSR1‐ERG was also undertaken following a negative RT‐PCR result for EWSR1‐FLI‐1. FISH for EWS‐FLI‐1 was carried out on one of the other cases and FISH using a commercial probe EWSR1, which identifies all translocations involving the EWSR1 gene on chromosome region 22q12, was performed on the other case. The molecular analyses were performed at several different laboratories using standard techniques.

Results

Clinical details

Table 1 presents the clinical details of the cases described herein together with the previously reported cases of EFTs involving the vulva and vagina. The patients in the current series were aged 19, 20, 30 and 40 years. Three tumours involved the vulva and one the vagina. One of the patients died from pulmonary metastasis and one is alive without disease at 12 months follow‐up. One case is recent and we have no significant follow‐up. In the other case, we have not been able to obtain follow‐up information.

Table 1 Clinical details of reported cases of Ewing family of tumours involving vulva and vagina.

| Authors | Age (years) | Site | Size (cm) | Adjuvant therapy | Confirmatory immunohistochemistry | Molecular | Follow‐up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCluggage et al (current study) | 30 | Anterior vaginal wall | 8 | NA | CD99 and FLI‐1 | RT‐PCR | NA |

| McCluggage et al (current study) | 40 | Right labium minor | 3 | CT | CD99 and FLI‐1 | FISH | AW, 12 months |

| McCluggage et al (current study) | 20 | Right labium | 6.5 | CD99 and FLI‐1 | FISH | Died from pulmonary metastasis | |

| McCluggage et al (current study) | 19 | Vulva, NOS | 4 | CT | CD99+ve; FLI‐1−ve | RT‐PCR and FISH−ve | NA |

| Vang et al9 | 35 | Vagina | 3 | CT & RT | CD99+ve | RT‐PCR | AW, 19 months |

| Vang et al9 | 28 | Right labium minor | 0.9 | CT | CD99+ve | RT‐PCR | AW, 18 months |

| Takeshima et al7 | 45 | Right labium major | 3 | None | CD99+ve | None | AD, 36 months |

| Gaono‐Luviano et al13 | 34 | Distal one‐third vagina | 4 | CT & RT | CD99+ve | None | AW, 20 months |

| Moodley et al16 | 26 | Right labium major | 5 | CT & RT | None | None | NA |

| Liao et al12 | 30 | Distal one‐third vagina | 5 | CT & RT | CD99 and FLI‐1+ve | None | AW, 36 months |

| Nirenberg et al14 | 20 | Right labium major | 12 | CT & RT | CD99−ve | None | DOD, 10 months |

| Farley et al15 | 35 | Vagina, NOS | 4 | CT & RT | CD99+ve | None | AW, 48 months |

| Lazure et al8 | 15 | Vulva, NOS | 20 | CT | CD99+ve | RT‐PCR | AW, 7 months |

| Paredes et al10 | 29 | Left vulva | 5 | CT & RT | None | None | AW, 8 months |

| Scherr et al11 | 10 | Left labium major | 6.5 | NA | CD99+ve | None | NA |

| Petkovic et al17 | 45 | Rectovaginal Septum | 9 | CT & RT | CD99+ve | None | AD, 18 months |

| Habib et al18 | 23 | Vulva, NOS | Not stated | NA | None | None | NA |

AD, alive with disease; AW, alive and well; CT, chemotherapy; DOD, died of disease; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridisation; NA, not available; NOS, not otherwise specified; RT, radiotherapy; RT‐PCR, reverse transcriptase‐PCR.

Pathological findings

The tumours measured 3, 4, 6.5 and 8 cm in maximum dimension. Two neoplasms were described as having a nodular or lobulated cut surface. One tumour was tan in colour, one cream, one red‐brown and one greyish‐brown.

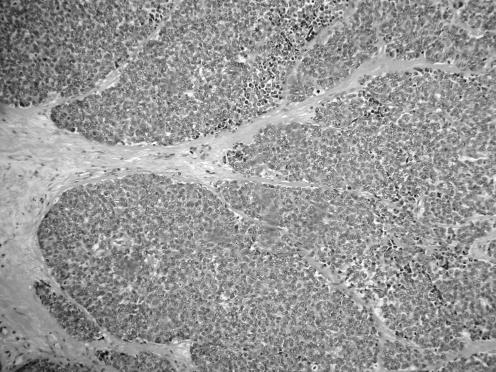

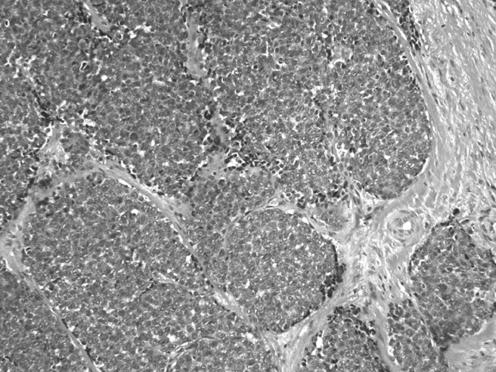

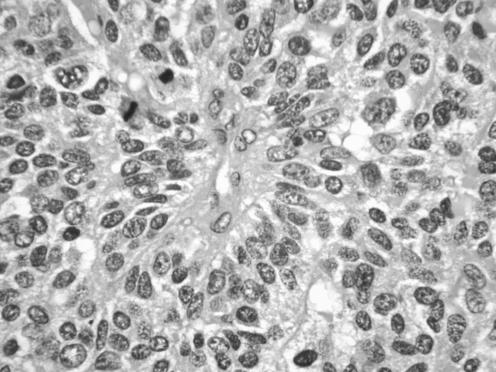

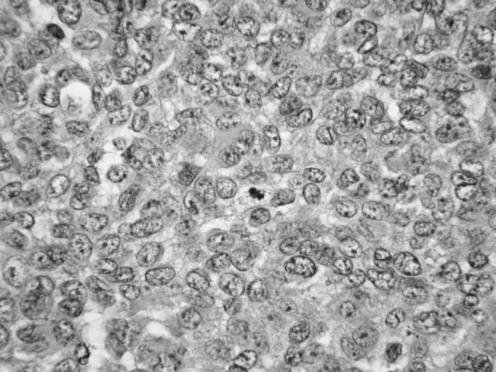

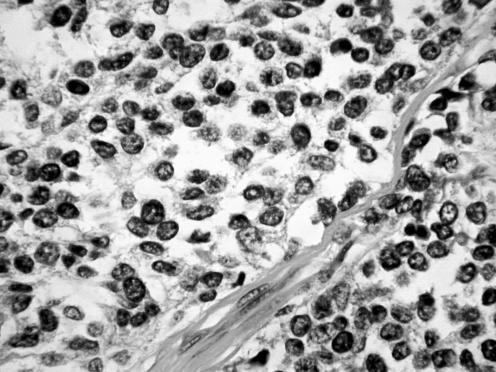

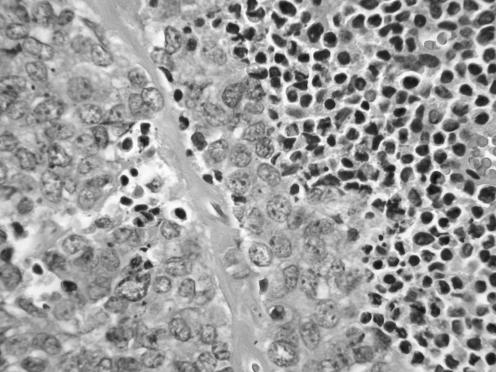

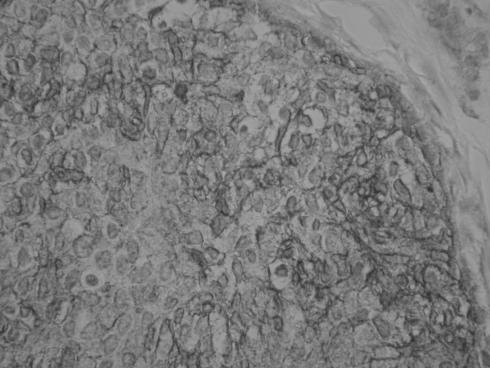

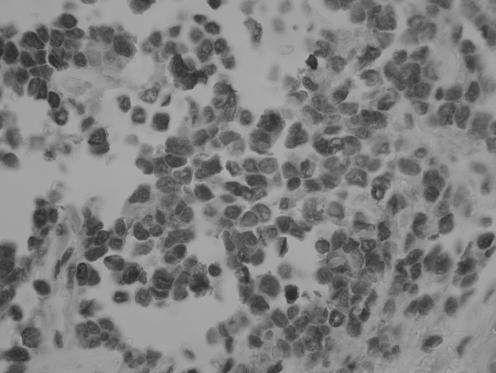

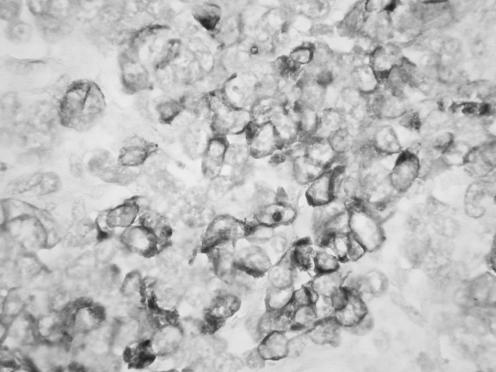

All neoplasms exhibited a similar histological appearance and were located just beneath the squamous epithelium of the vagina or vulva, which was ulcerated but not dysplastic. The tumours had a low‐power lobulated architecture and were composed of large solid cellular aggregates separated by fibrous septae (fig 1). Within the cellular aggregates, the growth pattern was diffuse (fig 2) with no evidence of keratinisation or glandular differentiation. In one case, an occasional rosette was formed (fig 3). Tumour cells had central regular hyperchromatic nuclei with coarse chromatin and small nucleoli (fig 4). The amount of cytoplasm varied between neoplasms and within individual neoplasms from scant to relatively abundant and was usually eosinophilic, although in some cases there was cytoplasmic clearing (fig 5). In three cases, there was, at least focally, relatively abundant cytoplasm. In all cases, there was a high mitotic rate, on average 5–6 mitoses per single high‐power field. Areas of necrosis (fig 6) were present in all cases and there was focal cytoplasmic accumulation of glycogen (periodic acid‐Schiff‐positive material removed by diastase predigestion) in the two cases where this was looked for. Lymphovascular permeation was identified in one case.

Figure 1 Low‐power view showing lobulated architecture with large aggregates of cells separated by fibrous septae.

Figure 2 The tumours were composed of solid aggregates of cells, largely without rosette formation.

Figure 3 Case where occasional rosettes were formed.

Figure 4 High‐power view showing regular nuclei with coarse chromatin and small nucleoli.

Figure 5 Cases with tumour cells having abundant clear cytoplasm.

Figure 6 Areas of necrosis were present in all tumours.

Immunohistochemical findings

All cases exhibited diffuse‐positive membrane staining with CD99 (fig 7); in two cases there was diffuse nuclear positivity with FLI‐1 (fig 8), and the other two cases were FLI‐I negative. In all cases, there was diffuse cytoplasmic vimentin positivity. Three cases exhibited focal cytoplasmic positivity with AE1/3 (fig 9), involving about 10% of the tumour cells in two cases and approximately 40% in the other. Desmin was negative in all cases.

Figure 7 Case exhibiting diffuse‐positive membranous staining with CD99.

Figure 8 Case exhibiting diffuse‐positive nuclear staining with FLI‐1.

Figure 9 Case exhibiting focal cytoplasmic positivity with AE1/3.

In one case that was FLI‐1 negative (it was also AE1/3 negative), an extensive panel of immunohistochemical stains was performed to help exclude other neoplasms in the differential diagnosis. The tumour was negative with calponin, h‐caldesmon, α smooth muscle actin, myogenin, S100, chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD56, neurone‐specific enolase, TTF1, epithelial membrane antigen, CK20, CD31, CD34, bcl2, CD117, placental alkaline phosphatase, CD45 and NB84.

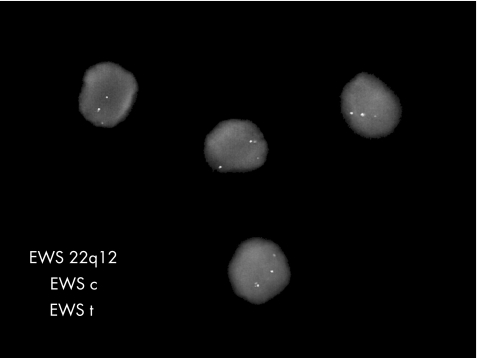

Molecular findings

One case was positive for EWSR1‐FLI‐1 by RT‐PCR. In one case, FISH analysis revealed a positive EWS‐FLI‐1 translocation. In another case, with FISH there was an EWSR1 gene rearrangement (fig 10). One case was negative by RT‐PCR for EWSR1‐FLI‐1 and EWS‐ERG, and also with FISH for EWS‐FLI‐1. This was one of the cases that was FLI‐1 negative by immunohistochemical analysis and the case in which the extensive panel of immunohistochemical analysis was undertaken.

Figure 10 FISH analysis showing a signal pattern indicative of an EWSR1 gene rearrangement with separation of the red‐orange and green signals from the normal fusion signal (yellow).

Discussion

Judging by the published literature, EFTs involving the vulva or vagina are extremely rare with only 13 previously reported possible cases,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 8 in the vulva and 5 in the vagina. These have all been individual case reports, except for one series of two tumours reported by Vang and coworkers.9 Table 1 summarises the previously described cases together with the cases we report. One of the previously reported cases was thought to be consistent with Ewing's sarcoma, although CD99 was negative,14 casting doubt on the diagnosis. In several other cases CD99 and/or FLI‐1 immunostaining was not undertaken.10,16,18 The rarity of EFTs at these sites can be seen from a recent series of 66 cases from a single institution, in which only tumours with molecular confirmation were included.2 In that series, none of the neoplasms involved the vulva or vagina, underscoring the rarity of this tumour at these sites. In addition, the cases reported herein were the only vulval or vaginal examples identified in the departments to which the authors are affiliated. Some of these are major referral centres dealing with large numbers of consultation cases of both soft tissue and gynaecological neoplasms. All of the cases we report were composed of solid sheets of undifferentiated cells with only occasional rosettes in one case and histologically would correspond to Ewing's sarcoma rather than pPNET. However, for the reasons outlined previously, we use the term EFTs.

In two of the cases we report, molecular techniques demonstrated the presence of the t(11;22) (q24; q12) chromosomal translocation, by far the most common translocation found in EFTs, being demonstrable in >90% of cases.1,2 This translocation, which results in EWS‐FLI‐1 chimeric transcripts by fusion of the fifth segment of the EWS gene on chromosome 22 with the third segment of the FLI‐1 gene on chromosome 11, is highly specific for EFTs, although it, and other related translocations which have been detailed previously, has been rarely demonstrated in other neoplasms.20 In another case, FISH using a probe which identifies all translocations involving the EWSR1 gene revealed it to be rearranged. Although this does not definitively prove that this neoplasm contains one of the translocations characteristic of EFTs, given the morphology and the CD99 and FLI‐1 positivity there is no doubt that this represents a neoplasm in the EFTs. The translocations may be demonstrated using classic cytogenetics (which requires fresh tissue) or by RT‐PCR or FISH, the latter two methods being applicable to routinely processed paraffin‐wax‐embedded tissue. Demonstration of one of the translocations may be regarded as the “gold‐standard” for diagnosis of a neoplasm in the EFTs, and this raises the question as to whether these tumours can be diagnosed without molecular techniques which are, of course, mostly only available in specialist molecular pathology laboratories and large referral centres. However, in general, EFTs with classic morphology are diagnosed without molecular confirmation,2 especially given the ready availability of markers such as CD99 and FLI‐1, which are positive in a large majority of cases.2 Molecular techniques may be valuable in the diagnosis of neoplasms with unusual morphological features, such as an adamantimoma‐like growth pattern, large cell or spindle cell variants, cases with abundant clear cytoplasm and cases with abundant hyalinised stroma.2 They may also be of value when these neoplasms arise outside the usual age group or at unusual sites, such as in the cases we describe. Of the previously reported cases of EFTs involving the vulva or vagina, only three have had molecular confirmation.8,9

In one of the cases in our series, both RT‐PCR and FISH failed to demonstrate the EWS‐FLI‐1 fusion transcript and the tumour was also negative for the EWS‐ERG fusion transcript by RT‐PCR. Not surprisingly, given the absence of the EWS‐FLI‐1 translocation, this neoplasm was negative with FLI‐1 by immunohistochemical analysis. It could be questioned as to whether this represents a neoplasm in the EFTs. However, given the morphology, the membranous CD99 positivity and negative staining with a wide range of other markers which helped to exclude other tumours in the differential diagnosis (discussed below), we believe on the balance of probability, that this represents a neoplasm in the EFTs. It is possible that this tumour harbours one of the other translocations, that rarely occur in EFTs, such as EWS‐ETV1 or EWS‐FEV. These translocations were not looked for in this case.

CD99 is a cell surface glycoprotein encoded by the MIC2 gene. It is expressed with a membranous distribution in virtually all neoplasms in the EFTs.2,5,21 In the series of cases with molecular confirmation referred to earlier,2 all tumours were CD99 positive. However, CD99 is not specific for EFTs and may be expressed in a variety of other neoplasms, including some that can enter into the differential diagnosis, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, some lymphomas and leukaemias, Merkel cell carcinoma, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and synovial sarcoma.21,22,23,24,25,26 Ovarian sex cord‐stromal tumours and pancreatic islet cell neoplasms may also be positive.27,28

FLI‐1 is a DNA‐binding transcription factor which is involved in cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis, as well as in endothelial differentiation and blood vessel development.29,30 Besides being positive in normal endothelial cells and vascular neoplasms, FLI‐1 is expressed (nuclear staining) in a large majority of neoplasms in the EFTs.6,31,32 FLI‐1 was positive in 94% of the tumours with molecular confirmation in the study referred to earlier.2 Almost all of the positive neoplasms had EWS‐FLI‐1 translocations but, interestingly, one tumour with an EWS‐ERG translocation was also positive. Other neoplasms that may enter into the differential of EFTs, including Merkel cell carcinoma, neuroblastoma, synovial sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour and malignant melanoma, may occasionally be positive with FLI‐1.31,33,34,35

Besides being positive in most cases with CD99 and FLI‐1, a significant proportion of neoplasms in the EFTs stain with broad‐spectrum cytokeratins,2,36,37 as in the current study. In one large study of genetically confirmed neoplasms, 32% were positive with broad‐spectrum cytokeratins, staining usually being focal in distribution.2 Positivity with broad‐spectrum cytokeratins may result in an erroneous diagnosis of an epithelial neoplasm, especially in age groups and sites such as the vulva or vagina, where carcinomas are by far the most common malignancy. Most carcinomas are CD99 and FLI‐1 negative, although some small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas may be CD99 positive, as discussed earlier. Ultrastructural examination of keratin‐positive neoplasms in the EFTs has revealed evidence of epithelial differentiation in the form of cell junctions.38

Neoplasms in the EFTs, some with molecular confirmation, have rarely been described at other sites in the female genital tract, including the ovary, broad ligament, uterus and cervix.39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51 In the uterus, cases were reported as PNETs before the advent of CD99 and FLI‐1 immunostaining.40,49 Some of these neoplasms included a component of an endometrial adenocarcinoma and may be viewed as carcinosarcomas, the sarcomatous element belonging to the EFTs.49,50 In the ovary, a single case has been reported with immunohistochemical and molecular confirmation39 and another example has been described coexisting with a component of endometrioid adenocarcinoma.51 Examples of ovarian PNET have also been described as a component of a teratomatous neoplasm.52 Probably, such neoplasms arise from the central nervous system component of a teratoma and are analogous to central PNETs which occur in the brain.53 These are generally CD99 negative and do not harbour the chromosomal translocations that are characteristic of neoplasms in the EFTs,54 including those referred to as pPNETs. A single case of PNET arising in the broad ligament and several cases in the cervix have had appropriate molecular confirmation.43,47,48

It can be seen from table 1 that, when arising in the vulva or vagina, EFTs usually occur in relatively young females, a similar age of predilection for these neoplasms when they involve more usual sites. However, almost half of the patients (8 of 17) were aged ⩾30 years at diagnosis, which is rare for EFTs in general, and raises the possibility that the vulval or vaginal neoplasms may occur in a slightly older age group.

Neoplasms in the EFTs are aggressive with a poor prognosis.55 It is difficult to ascertain whether the behaviour of vulval and vaginal tumours is similar to those neoplasms that arise at more usual sites, as too few cases have been reported and many of them have limited or no follow‐up. However, 8 of 12 patients with follow‐up ranging from 7 to 48 months are alive without recurrence (table 1). Two patients died from disease and two are alive with disease at 18 and 36 months. Adjuvant therapy has usually been in the form of chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy. These admittedly limited data suggest that EFTs in the vulva or vagina could have a better outcome than when these neoplasms involve more usual sites. One of the patients in this report died from pulmonary metastasis and another is alive without disease with 12 months follow‐up. One case is recent with no significant follow‐up, and in the other we have not been able to obtain follow‐up.

The differential of EFTs in the vulva or vagina is essentially similar to that when these neoplasms occur at more usual sites, although a location in the vulva or vagina may also raise other diagnostic considerations. This illustrates the important point, which is true in many aspects of surgical pathology, that when faced with an undifferentiated neoplasm composed of small round cells, the differential is framed not only on the morphology but also, to a large extent, on other factors such as the location of the neoplasm and the age of the patient. For example, when confronted with such a neoplasm in the ovary of a young patient, hypercalcaemic small cell carcinoma would be high in the differential,56,57 but obviously this is not a consideration at other sites. We also make the point that in three of the cases we report the tumour cells had, at least focally, an appreciable amount of cytoplasm, rather than being composed of small round cells per se.

Take‐home messages

Ewing's sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour harbour the same t(11;22) (q24;q12) chromosomal translocation in >90% of cases and are collectively referred to as Ewing family of tumours (EFTs).

CD99 and FLI‐1 immunohistochemical analysis is useful in diagnosis and these markers are positive in a large majority of cases.

EFTs involving the vulva and vagina are extremely rare, with only 13 previously reported possible cases.

Demonstration of one of the characteristic translocations may be regarded as the gold standard for diagnosis of a neoplasm in the EFTs.

As EFTs are most common at a relatively young age, small round cell tumours of childhood, including neuroblastoma, embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, and lymphomas and leukaemias are often the major diagnostic consideration. As discussed, some of these may be CD99 positive21,22,23,24,25,26 but, in general, a carefully chosen panel of markers assists in establishing a correct diagnosis. It should be noted that rare neoplasms in the EFTs are desmin positive,2,58 although all of the cases we report were negative. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (primary or secondary), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, small cell non‐keratinising squamous carcinoma, malignant melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma and synovial sarcoma may also enter into the differential in the vulva or vagina and some of these may be CD99 or FLI‐1 positive.21,22,23,24,25,26 Again judicious use of a panel of markers and appropriate molecular tests, if necessary, assists in establishing a diagnosis. In the lower part of the female genital tract, endometrial stromal sarcoma, metastatic from the uterus or rarely primary in the vulva or vagina, may be considered in the differential. However, endometrial stromal sarcoma is composed of much blander cells with less hyperchromatic nuclei and fewer mitoses than EFTs. Endometrial stromal sarcoma is usually CD10,59 oestrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive and would be expected to be negative with CD99 and FLI‐1.

In summary, we describe four cases of neoplasms in the EFTs occurring in the vulva or vagina, the largest series reported to date. All cases were characterised by membranous CD99 staining and two exhibited nuclear FLI‐1 positivity. Two cases were demonstrated by RT‐PCR or FISH to possess the t(11;22) (q24;q12) (EWS‐FLI‐1) chromosomal translocation, which is characteristic of this group of neoplasms, and another was shown to have a rearrangement of the EWSR1 gene.

Abbreviations

EFTs - Ewing family of tumours

FISH - fluorescence in situ hybridisation

PNET - primitive neuroectodermal tumour

pPNET - peripheral PNET

RT‐PCR - reverse transcriptase‐PCR

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.de Alava E, Pardo J. Ewing tumor: tumor biology and clinical applications. Int J Surg Pathol 200197–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folpe A L, Goldblum J R, Rubin B P.et al Morphologic and immunophenotypic diversity in Ewing family tumors: a study of 66 genetically confirmed cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2005291025–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dehner L P. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor and Ewing's sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1993171–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt D, Herrmann C, Jurgens H.et al Malignant peripheral neuroectodermal tumor and its necessary distinction from Ewing's sarcoma. A report from the Kiel Pediatric Tumor Registry. Cancer 1991682251–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson A, Chatten J, Bertoni F.et al CD99/p30/32/MIC2/neuroectodermal/Ewing's sarcoma antigen as an immunohistochemical marker: review of more than 600 tumors and the literature experience. Appl Immunohistochem 19942231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Folpe A L, Hill C E, Parham D M.et al Immunohistochemical detection of FLI‐1 protein expression: a study of 132 round cell tumors with emphasis on CD99‐positive mimics of Ewing's sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2000241657–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshima N, Tabata T, Nishida H.et al Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the vulva: report of a case with imprint cytology. Acta Cytol 2001451049–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazure T, Alsamad I A, Meuric S.et al Primary uterine and vulvar Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral neuroectodermal tumors in children: two unusual locations. Ann Pathol 200121263–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vang R, Taubenberger J K, Mannion C M.et al Primary vulvar and vaginal extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral neuroectodermal tumor: diagnostic confirmation with CD99 immunostaining and reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction. Int J Gynecol Pathol 200019103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paredes E, Duarte A, Couceiro A.et al A peripheral neuroectodermal tumor of the vulva. Acta Med Port 19958161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scherr G R, d'Ablaing G, 3rd, Ouzounian J G. Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the vulva. Gynecol Oncol 199454254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao X, Xin X, Lu X. Primary Ewing's sarcoma‐primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the vagina. Gynecol Oncol 200492684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaona‐Luviano P, Unda‐Franco E, Gonzalez‐Jara L.et al Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the vagina. Gynecol Oncol 200391456–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nirenberg A, Ostor A G, Slavin J.et al Primary vulvar sarcomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 19941455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farley J, O'Boyle J D, Heaton J.et al Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol 200096832–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moodley M, Jordaan A. Ewing's sarcoma of the vulva–a case report. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005151177–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petkovic M, Zamolo G, Muhvic D.et al The first report of extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma in the rectovaginal septum. Tumori 200288345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Habib K, Finet J F, Plantier F.et al A rare lesion of the vulva. Arch Anat Cytol Path 199240158–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mangham D C, Williams A, McMullan D J.et al Ewing's sarcoma of bone: the detection of specific transcripts in a large consecutive series of formalin‐fixed, decalcified, paraffin‐embedded tissue samples using the reverse transcriptase‐polymerase chain reaction. Histopathology 200648363–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thorner P, Squire J, Chilton‐MacNeil S.et al Is the EWS/FLI‐1 fusion transcript specific for Ewing sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor? A report of four cases showing this transcript in a wider range of tumor types. Am J Pathol 19961481125–1138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perlman E J, Dickman P S, Askin F B.et al Ewing's sarcoma–routine diagnostic utilization of MIC2 analysis: a Pediatric Oncology Group/Children's Cancer Group Intergroup Study. Hum Pathol 199425304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riopel M, Dickman P S, Link M P.et al MIC2 analysis in pediatric lymphomas and leukemias. Hum Pathol 199425396–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidner N, Tjoe J. Immunohistochemical profile of monoclonal antibody O13: antibody that recognizes glycoprotein p30/32MIC2 and is useful in diagnosing Ewing's sarcoma and peripheral neuroepithelioma. Am J Surg Pathol 199418486–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumadue J A, Askin F B, Perlman E J. MIC2 analysis of small cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1994102692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perlman E J, Lumadue J A, Hawkins A L.et al Primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumors. Diagnostic use of cytogenetic and MIC2 analysis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 19958230–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher C. Synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol 19982401–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loo K T, Leung A K, Chan J K. Immunohistochemical staining of ovarian granulosa cell tumours with MIC2 antibody. Histopathology 199527388–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goto A, Niki T, Terado Y.et al Prevalence of CD99 protein expression in pancreatic endocrine tumours (PETs). Histopathology 200445384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharrocks A D, Brown A L, Ling Y.et al The ETS‐domain transcription factor family. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 1997291371–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mager A M, Grapin‐Botton A, Ladjali K.et al The avian fli gene is specifically expressed during embryogenesis in a subset of neural crest cells giving rise to mesenchyme. Int J Dev Biol 199844561–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Llombart‐Bosch A, Navarro S. Immunohistochemical detection of EWS and FLI‐1 proteins in Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors: comparative analysis with CD99 (MIC‐2) expression. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 20019255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson G, Wang M, Wejde J.et al Detection of EWS/FLI 1 by immunostaining: an adjunctive tool in diagnosis of Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor on cytological samples and paraffin‐embedded archival material. Sarcoma 1999325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi S, Orvieto E, Furlanetto A.et al Utility of the immunohistochemical detection of FLI‐1 expression in round cell and vascular neoplasm using a monoclonal antibody. Mod Pathol 200417547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llombart B, Monteagudo C, Lopez‐Guerrero J A.et al Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 20 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma in search of prognostic markers. Histopathology 200546622–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen S H, Thomas D G, Lucas D R. Cluster analysis of immunohistochemical profiles in synovial sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol 200619659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collini P, Sampietro G, Bertulli R.et al Cytokeratin immunoreactivity in 41 cases of ES/pNET confirmed by molecular diagnostic studies. Am J Surg Pathol 200125273–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu M, Antonescu C R, Guiter G.et al Cytokeratin immunoreactivity in Ewing's sarcoma: prevalence in 50 cases confirmed by molecular diagnostic studies. Am J Surg Pathol 200024410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srivastava A, Rosenberg A E, Selig M.et al Keratin‐positive Ewing's sarcoma: an ultrastructural study of 12 cases. Int J Surg Pathol 20051343–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawauchi S, Fukuda T, Miyamoto S.et al Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the ovary confirmed by CD99 immunostaining, karyotypic analysis, and RT‐PCR for EWS/FLI‐1 chimeric mRNA. Am J Surg Pathol 1998221417–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hendrickson M R, Scheithauer B W. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the endometrium: report of two cases, one with electron microscopic observations. Int J Gynecol Pathol 19865249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato S, Yajima A, Kimura N.et al Peripheral neuroepithelioma (peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor) of the uterine cervix. Tohoku J Exp Med 199 180187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horn L C, Fischer U, Bilek K. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the cervix uteri: a case report. Gen Diagn Pathol 1996142227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cenacchi G, Pasquinelli G, Montanaro L.et al Primary endocervical extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma/pNET. Int J Gynecol Pathol 19981783–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snijders‐Keilholz A, Ewing P, Seynaeve C.et al Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the cervix uteri: a case report–changing concepts in therapy. Gynecol Oncol 200598516–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malpica A, Moran C. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the cervix: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of two cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 20026281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward W S, Hitchock C L, Keyhani S. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the uterus. A case report. Acta Cytol 200044667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee K M, Wah H R. Primary Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors arising from the broad ligament. Int J Gynecol Pathol 200524377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pauwels P, Ambros R, Huttinger C.et al Peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the cervix. Virchows Arch 200043668–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daya D, Lukka H, Clement P B. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the uterus: a report of four cases. Hum Pathol 1992231120–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinkre P, Albores‐Saavedra J, Miller D S.et al Endometrial endometrioid carcinomas associated with Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Int J Gynecol Pathol 20009127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fischer G, Odunsi K, Lele S.et al Ovarian primary primitive neuroectodermal tumor coexisting with endometrioid adenocarcinoma: a case report. Int J Gynecol Pathol 200625151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleinman G M, Young R H, Scully R E. Primary neuroectodermal tumors of the ovary. A report of 25 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 199317764–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dehner L P. Peripheral and central primitive neuroectodermal tumors. A nosologic concept seeking a consensus. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1986110997–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishii N, Hiraga H, Sawamura Y.et al Alternative EWS‐FLI1 fusion gene and MIC2 expression in peripheral and central primitive neuroectodermal tumors. Neuropathology 20012140–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shankar A G, Ashley S, Craft A W.et al Outcome after relapse in an unselected cohort of children and adolescents with Ewing sarcoma. Med Pediatr Oncol 200340141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCluggage W G. Ovarian neoplasms composed of small round cells: a review. Adv Anat Pathol 200411288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCluggage W G, Oliva E, Connolly L E.et al An immunohistochemical analysis of ovarian small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type. Int J Gynecol Pathol 200423330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parham D M, Dias P, Kelly D R.et al Desmin positivity in primitive neuroectodermal tumors of childhood. Am J Surg Pathol 199216483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCluggage W G, Sumathi V P, Maxwell P. CD10 is a sensitive and diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker of normal endometrial stroma and of endometrial stromal neoplasms. Histopathology 200139273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]