Abstract

Objective

Various demyelinating disorders have been reported in association with anti‐tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) agents. The objective of this study was to review the occurrence, clinical features and outcome of optic neuritis (ON) during treatment with anti‐TNFα agents.

Methods

A PubMed search was conducted to identify literature addressing the potential association between anti‐TNFα agents and ON, following our experience with a patient having rheumatoid arthritis in whom ON developed while being treated with infliximab.

Results

15 patients including the case presented here with ON in whom the symptoms developed following TNFα antagonist therapy were evaluated. Eight of these patients had received infliximab, five had received etanercept and two patients had received adalimumab. Among them, nine patients experienced complete resolution, and two patients had partial resolution, while four patients continued to have symptoms.

Discussion

Patients being treated with a TNFα antagonist should be closely monitored for the development of ophthalmological or neurological signs and symptoms. Furthermore, consideration should be given to avoiding such therapies in patients with a history of demyelinating disease. If clinical evaluation leads to the diagnosis of ON, discontinuation of the medication and institution of steroid treatment should be a priority.

Anti‐tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) agents have come into widespread use, and an increasing number of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and Crohn's disease are being successfully treated with this new generation of biological agents. Although rare, several reports of new onset or exacerbation of demyelinating disorders have been noted following treatment with TNFα antagonists, and continued observation is warranted in patients on these agents for the development of such diseases.1 The demyelinating disorders that have been reported to be associated with TNFα antagonist therapy are variable, and include multiple sclerosis (MS), optic neuritis (ON), transverse myelitis and Guillain–Barré syndrome.2,3,4

The medical rubric “optic neuritis” is possibly more a clinical syndrome than an isolated disease and can be caused by a variety of infectious, inflammatory, demyelinating, metabolic, toxic, nutritional, vascular and hereditary aetiologies. In particular, acute demyelinating ON is one of the most frequently encountered optic neuropathies in clinical practice, and is best known for its association with MS. However, acute demyelinating ON can also occur as an isolated episode without any progression.5

A review of the Adverse Events Reporting System database of the Food and Drug Administration in 2001 identified 20 cases of demyelinating disorders following treatment with anti‐TNFα agents for arthritis. ON was reported to be the second most common presentation (8 of 20), and it was the sole presenting symptom among two of them.2

We describe a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who developed retrobulbar ON while she was concurrently being treated with infliximab and isoniazid. We also reviewed the cases of TNFα antagonist‐associated ON reported to date in the medical literature.

Patients and methods

We conducted a medical literature search in PubMed and identified 14 cases of ON occurring in patients receiving TNFα antagonist therapy.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13

Index patient

The patient was a 31‐year‐old woman with a 4‐year history of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis in whom the disease had failed to respond to methotrexate, sulphasalazine, leflunomide and oral prednisolone alone and in combination at full doses. Due to her active, treatment‐resistant rheumatoid arthritis, treatment with etanercept was considered. In order to rule out latent tuberculosis infection, a chest x‐ray and tuberculin skin test were performed according to the standard guidelines. The tuberculin skin test was found to be positive, while no abnormalities were detected on chest x‐ray. Accordingly, she was given isoniazid 300 mg once daily 3 weeks prior to the institution of etanercept treatment. In June 2005, treatment with etanercept was initiated as 25 mg twice weekly by subcutaneous injection, and all other medications except isoniazid were discontinued. However, after the fourth dose of etanercept, her regimen was switched to infliximab owing to the development of a severe injection site reaction with etanercept. Infliximab was administered intravenously in doses of 3 mg/kg body weight at weeks 0, 2 and 6, and then at 8‐weekly intervals. After three doses of infliximab, dramatic improvement in her clinical condition occurred.

In December 2005, 4 weeks following the fourth dose of infliximab, the patient noticed defects in her visual field, reduced perception of brightness and pain with ocular movement, affecting the left eye, which gradually worsened over the ensuing week.

Ophthalmological examination was highly suggestive of ON (tables 1 and 2). Visual evoked potentials (VEPs) were found to be reduced in the left eye with prolonged latency, compatible with ON. Contrast‐enhanced MRI of the brain and orbits as well as the electroretinogram were normal, as was intravenous fluorescein angiography. Treatment with infliximab and isoniazid was terminated considering the potential visual adverse reactions associated with both drugs. She was given three pulses of 1000 mg of intravenous methylprednisolone daily for three consecutive days, followed by 60 mg/day of oral prednisolone, which was then tapered to termination within 3 weeks. One month after the cessation of the offending drugs and initiation of prednisolone therapy, computerised perimetry showed complete resolution of visual field defects in the affected eye. At that time, VEP testing disclosed improved responses, but latency in the affected eye was still longer than in the other eye. No further deterioration or relapse was noted during the follow‐up, and, VEP abd visual field investigations at 12 months were entirely normal.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics and outcome of the patients who developed optic neuritis during anti‐tumour necrosis factorα therapy.

| Case | Reference | Age and sex | Indication | Anti‐TNF agent | Duration of therapy | Ocular involvement | MRI findings | Therapy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Strong7 | 45 F | Crohn's | Infliximab | 10 months | UR | Normal | Pulse MP* | Complete recovery at 3 months |

| 2 | Foroozan8 | 55 F | RA | Infliximab | 13 months | UR | Mild enhancement of orbital portion of the optic nerve | Pulse MP* | Complete recovery at 3 weeks |

| 3 | ten Tusscher9 | 54 M | RA | Infliximab | 3 months | BA | NR | Pulse MP | Continued symptoms without recovery |

| 4 | ten Tusscher9 | 62 F | RA | Infliximab | 3 months | BA | NR | Pulse MP | Continued symptoms without recovery |

| 5 | ten Tusscher9 | 54 M | RA | Infliximab | 2 months | BA | NR | Pulse MP | Continued symptoms without recovery |

| 6 | Mejico10 | 50 F | Crohn's | Infliximab | NR | UR | Enhancement of retro‐orbital portion of the optic nerve | No treatment | Complete recovery at 6 weeks |

| 7 | Tran11 | 45 F | RA | Infliximab | 11 months | UR | Normal | Pulse MP* | Complete recovery at 3 months |

| 8 | Index case | 31 F | RA | Infliximab | 4 months | UR | Normal | Pulse MP* | Complete recovery at 1 month, no recurrence at 12 months |

| 9 | Tauber12 | 12 F | JIA | Etanercept | 2.5 months | UA | NR | Pulse MP | Complete recovery at 3 months, no recurrence at 18 months |

| 10 | Tauber12 | 17 F | JIA | Etanercept | 8 months | UA | NR | Pulse MP* | Complete recovery at 2 months, no recurrence at 20 months |

| 11 | Tauber12 | 21 F | JIA | Etanercept | 18 months | BR | NR | Pulse MP | Continued symptoms while continuing etanercept at 6 months |

| 12 | Tauber12 | 18 M | JSpA | Etanercept | 11 months | UR | NR | Pulse MP | Complete recovery at 1 week, no recurrence at 14 months |

| 13 | Noguera‐Pons6 | 55 M | RA | Etanercept | 3 months | BA | Demyelinating lesions at periventricular and perisilvian region | Pulse MP* | Partial recovery as improved VA of OD at 6 months |

| 14 | Chung13 | 55 M | PsA | Adalimumab | 4 months | UR | Enhancement of intracanalicular portion of the optic nerve | Pulse MP* | Complete recovery at 1 week, no recurrence at 12 months |

| 15 | Chung13 | 40 M | RA | Adalimumab | 12 months | UR | Mild enhancement of orbital portion of the optic nerve, demyelinating plaques at periventricular and C‐spine localisation | No treatment | Partial recovery while continuing adalimumab at 4 months |

BA, bilateral anterior; BR, bilateral retrobulbar; F, female; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis; JSpA, juvenile spondyloarthritis; M, male; MP, methylprednisolone; *followed by tapering dose of oral prednisone; NR, not reported; OD = right eye; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; UA, unilateral anterior; UR, unilateral retrobulbar; VA, visual acuity.

Table 2 Findings at ophtalmological examination of the reported cases.

| Case | Reference | Pain with EOM | Visual acuity | RAPD | Colour vision | Visual field | Fundoscopy | VEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Strong7 | Yes | OS: 20/70 | Positive | NR | OS: cecocentral scotoma | OS: trace oedema of the optic nerve | NR |

| 2 | Foroozan8 | Yes | OS: 20/50 | Positive | Abnormal | OS: superior altitudinal defect | Normal | NR |

| 3 | ten Tusscher9 | No | OD: 20/30; OS: 20/30 | NR | NR | OD: inferior altitudinal defect; OS: inferior altitudinal defect | OD: swollen optic disc; OS: swollen optic dics | NR |

| 4 | ten Tusscher9 | No | OD: 20/40; OS: 20/80 | NR | NR | OD: cecocentral scotoma; OS: central scotoma | OD: swollen optic disc; OS: swollen optic disc with haemorrhage | NR |

| 5 | ten Tusscher9 | No | OD: 20/400; OS: 20/100 | NR | NR | OD: cecocentral scotoma; OS: central scotoma | OD: swollen optic disc; OS: swollen optic dics | NR |

| 6 | Mejico10 | Yes | NR | NR | NR | OS: superior altitudinal defect; OD: superior depression | Normal | NR |

| 7 | Tran11 | Yes | OS: 0.3 | Positive | Abnormal | OS: paracentral scotoma | Normal | Prolonged latency |

| 8 | Index case | Yes | OS: 20/20 | Positive | Abnormal | OS: superior altitudinal defect | Normal | Reduced with prolonged latency |

| 9 | Tauber | No | OD:6/60 | NR* | Abnormal | NR* | OD:inflammatory cells in the vitreous with a swollen optic disc† | Reduced with prolonged latency |

| 10 | Tauber12 | No | OD: phthitic; OS: 6/18 | NR‡ | NR* | NR* | OD: swollen optic disc | NR |

| 11 | Tauber12 | No | OD: 6/24; OS: 6/24 | Negative | Abnormal | NR§ | Normal | Prolonged latency |

| 12 | Tauber12 | Yes | OD: finger counting at 20 cm | NR* | NR* | NR* | OD: inflammatory cells in the vitreous with a swollen optic disc† | Reduced with prolonged latency |

| 13 | Noguera‐Pons6 | No | OD: 0.7; OS: 0.7 | NR | NR | NR | OD: swollen optic disc; OS: blurred borders of optic dics | Reduced with prolonged latency |

| 14 | Chung13 | No | OD: 20/30 | Positive | Abnormal | OD: inferotemporal pericentral scotoma | Normal | NR |

| 15 | Chung13 | Yes | OD: 1/200 | Positive | Abnormal | OD: central scotoma | OD: mild nasal opic disc swelling | NR |

EOM, extra‐ocular movement; NR, not reported; OD, right eye; OS, left eye; RAPD, relative afferent pupillary defect; VEP, visually evoked potential testing.

*Cataract and synechia prevented accurate RAPD, visual field testing and fundoscopy.

†Findings at ocular ultrasonography.

‡RAPD could not be measured due to the phtysis of the fellow eye.

§Visual field testing was not reliable because of poor compliance.

Results

To date, 15 cases of isolated ON including the case presented here, without additional neurological findings, possibly associated with TNFα antagonists have been reported in the literature.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Eight of these patients had received infliximab, five had received etanercept, and two patients had received adalimumab. Clinical summaries of these patients are provided in table 1. The median interval from the first administration of TNFα antagonist treatment to the onset of ON was 7.5 months (range 2 months to 1.5 years).

Findings at ophthalmological examination are summarised in table 2. Brain MRIs were reported for eight of 15 patients. Among them, two disclosed a pattern compatible with demyelination in different areas of the central nervous system (CNS).

All patients but one received treatment for ON, which included pulse steroids followed by oral steroids. Nine patients experienced complete resolution, and two patients had partial resolution of ON. Four patients continued to have symptoms.

It is of interest to note that three patients (cases 3, 4 and 5) in whom the symptoms continued without recovery had bilateral anterior ON which is not very representative of acute demyelinating ON.9 Those three patients had capillary dilation and vascular leakage as well as swelling in both optic nerve heads, which are more suggestive of an ischaemic or toxic form of ON.9 Treatment with anti‐TNF agents was not discontinued in two patients. One of these patients experienced a partial resolution, while the other continued to have symptoms during the follow‐up of 4 and 6 months, respectively.

Discussion

TNFα has been thought to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS. It has been demonstrated in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis that inhibiting the biological activity of TNFα prevents the development of demyelinating lesions in the CNS. However, surprisingly, anti‐TNF agents were found to be ineffective in the treatment of MS in humans. This paradoxical failure of anti‐TNF agents in MS and in the precipitation of demyelinating events may be explained by several mechanisms including heterogeneity of the role and mechanism of action of TNFα in diverse autoimmune diseases, inability of these agents to pass through the blood–brain barrier to neutralise and prevent local TNFα‐mediated tissue injury, as well as their as yet unidentified role in promoting particular immune responses that contribute to demyelination.14

The index patient presented here displayed many of the typical features of acute demyelinating ON. Judging by the temporal proximity of the onset of the visual symptoms and the initiation of infliximab therapy, as well as the improvement of visual field defects without any recurrence after discontinuation of the drug, we assume a causal link.

Our patient had also been taking isoniazid, a drug known to cause ON as a rare side effect,15 for 8 months when the visual symptoms emerged.

Recently, Noguera‐Pons et al6 reported a patient having bilateral ON with poor visual outcome presumably resulting from concomitant use of etanercept and isoniazid. Although the contribution of isoniazid to the development of ON in our patient remains a possibility, more cases of ON associated with the concomitant use of anti‐TNFα agents and isoniazid are required to conclude whether such a combination has an increased potential for the development of ON.

Certainly, given the small number of cases, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that all those reported cases may represent the background incidence of ON in a population receiving more vigilant follow‐up. However, in the light of the abundance of data suggesting a pathogenetic relationship between demyelinating disease and the TNFα pathway, it is theoretically conceivable that its blockade could induce or simply unmask an underlying subclinical demyelinating process.

In clinical practice, the significance of ON as a separate clinical entity stems from the fact that acute demyelinating ON is the initial presenting manifestation in up to 20% of patients and may occur at any point in the course of disease in up to 50% of MS patients.5 A question that remains unanswered awaiting further surveillance and follow‐up is whether ON developed during treatment with anti‐TNF agents follows a similar course and prognosis to that of idiopathic ON, or whether it represents a transient demyelinating attack without further progression to MS.

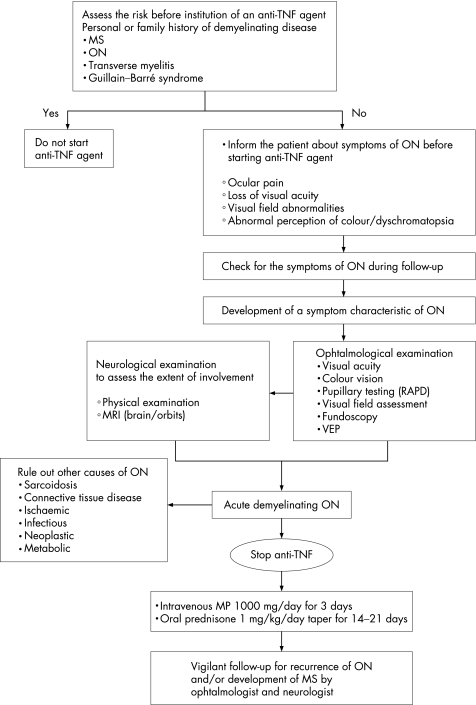

Considering the rarity of this condition along with the relatively short follow‐up of the reported cases, available data are insufficient to extract firm conclusions about the optimal treatment and follow‐up of those patients. However, as outlined in fig 1, we suggest that patients being treated with a TNFα antagonist should be closely monitored for the development of ophthalmological or neurological signs and symptoms. If clinical evaluation leads to the diagnosis of ON, discontinuation of the medication and institution of steroid treatment should be a priority.

Figure 1 Algorithm for the evaluation and follow‐up of a patient receiving anti‐tumour necrosis factor (TNF) agents for the development of optic neuritis (ON). MS, multiple sclerosis; RAPD, relative afferent pupillary defect; VEP, visually evoked potential testing; MP, methylprednisolone. Available data suggesting the use of pulse MP for this clinical entity are limited to the cases presented here and elsewhere. However, treatment with steroids can be considered in these patients based on the data regarding the beneficial role of steroids in patients with acute demyelinating ON.

Abbreviations

CNS - central nervous system

MS - multiple sclerosis

ON - optic neuritis

TNF - tumour necrosis factor

VEP - visually evoked potential

Footnotes

Competing interest: None.

References

- 1.Khanna D, McMahon M, Furst D E. Safety of tumour necrosis factor‐alpha antagonists. Drug Saf 200427307–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohan N, Edwards E T, Cupps T R, Oliverio P J, Sandberg G, Crayton H.et al Demyelination occurring during anti‐tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy for inflammatory arthritides. Arthritis Rheum 2001442862–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas C W, Jr, Weinshenker B G, Sandborn W J. Demyelination during anti‐tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy with infliximab for Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20041028–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin I S, Baer A N, Kwon H J, Papadopoulos E J, Siegel J N. Guillain–Barre and Miller Fisher syndromes occurring with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonist therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2006541429–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatti M T, Schmitt N J, Beatty R L. Acute inflammatory demyelinating optic neuritis: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Optometry 200576526–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noguera‐Pons R, Borras‐Blasco J, Romero‐Crespo I, Anton‐Torres R, Navarro‐Ruiz A, Gonzalez‐Ferrandez J A. Optic neuritis with concurrent etanercept and isoniazid therapy. Ann Pharmacother 2005392131–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strong B Y, Erny B C, Herzenberg H, Razzeca K J. Retrobulbar optic neuritis associated with infliximab in a patient with Crohn disease. Ann Intern Med 2004140W34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foroozan R, Buono L M, Sergott R C, Savino P J. Retrobulbar optic neuritis associated with infliximab. Arch Ophthalmol 2002120985–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ten Tusscher M P, Jacobs P J, Busch M J, de Graaf L, Diemont W L. Bilateral anterior toxic optic neuropathy and the use of infliximab. BMJ 2003326579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mejico L J. Infliximab‐associated retrobulbar optic neuritis. Arch Ophthalmol 2004122793–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tran T H, Milea D, Cassoux N, Bodaghi B, Bourgeois P, LeHoang P. [Optic neuritis associated with infliximab]. J Fr Ophtalmol 200528201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tauber T, Turetz J, Barash J, Avni I, Morad Y. Optic neuritis associated with etanercept therapy for juvenile arthritis. J AAPOS 20061026–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung J H, Van Stavern G P, Frohman L P, Turbin R E. Adalimumab‐associated optic neuritis. J Neurol Sci 2006244133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson W H, Genovese M C, Moreland L W. Demyelinating and neurologic events reported in association with tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonism: by what mechanisms could tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists improve rheumatoid arthritis but exacerbate multiple sclerosis? Arthritis Rheum 2001441977–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman A L, Braman S S. Isoniazid: a review with emphasis on adverse effects. Chest 19726271–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]