Abstract

Background

Left ventricular non‐compaction (LVNC) may manifest an undulating phenotype ranging from dilated to hypertrophic appearance. It is unknown whether tissue Doppler (TD) velocities can predict adverse clinical outcomes including death and need for transplantation in children with LVNC.

Methods and results

56 children (median age 4.5 years, median follow‐up 26 months) with LVNC evaluated at one hospital from January 1999 to May 2004 were compared with 56 age/sex‐matched controls. Children with LVNC had significantly decreased early diastolic TD velocities (Ea) at the lateral mitral (11.0 vs 17.0 cm/s) and septal (8.9 vs 11.0 cm/s) annuli compared with normal controls (p<0.001 for each comparison). Using receiver operator characteristic curves, the lateral mitral Ea velocity proved the most sensitive and specific predictor for meeting the primary end point (PEP) at 1 year after diagnosis (area under the curve = 0.888, SE = 0.048, 95% CI 0.775 to 0.956). A lateral mitral Ea cut‐off velocity of 7.8 cm/s had a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 79% for the PEP. Freedom from death or transplantation was 85% at 1 year and 77% at 2 years.

Conclusions

TD velocities are significantly reduced in patients with LVNC compared with normal controls. Reduced lateral mitral Ea velocity helps predict children with LVNC who are at risk of adverse clinical outcomes including death and need for cardiac transplantation.

Recently, there has been an increase in the number of reports of left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC), a relatively common form of cardiomyopathy, which had gone unrecognised before the mid‐1980s.1,2,3,4 The natural history of LVNC has been extensively detailed in adults,5,6,7,8 and recently specific differences have been highlighted in the paediatric population.9,10 A distinctive feature in children with LVNC is the potential for an “undulating phenotype” with transition between dilated and hypertrophic phenotypes in addition to a subset of patients showing an improvement with subsequent deterioration in left ventricular (LV) systolic function over time.10 For several years, patients were diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) when in fact they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for LVNC.10 Lack of awareness of LVNC has raised concerns that certain forms of HCM, particularly apical HCM, may actually be LVNC in certain cases.11

Conventional echocardiographic Doppler indices evaluating diastolic ventricular function are unreliable in predicting clinical status in patients with cardiomyopathy primarily due to their dependence on loading conditions.12 Recently, tissue Doppler has shown clinical relevance among children with HCM and DCM.13,14 TD velocities are an attractive index of diastolic ventricular function as they reflect intrinsic myocardial properties and may provide insight into the degree of diastolic dysfunction.15 The purpose of this study was to characterise TD velocities in children with LVNC and to determine whether TD velocities can predict children with LVNC who are at risk of death or need transplantation.

Methods

We prospectively studied consecutive paediatric patients with LVNC at Texas Children's Hospital (Houston, Texas, USA) between January 1999 and May 2004. Standard transthoracic echocardiograms including TD analysis were obtaind for each patient. We compared children with LVNC with age‐ and sex‐matched normal controls during the study period (controls included children with a normal echocardiogram referred for echocardiography due to the presence of a cardiac murmur or abnormal screening chest x ray or electrocardiogram). Diagnostic criteria for LVNC included (1) >3 trabeculations, (2) deep recesses and (3) a compacted: non‐compacted ratio >2:1.10 Comparisons were then drawn between patients with LVNC and an age‐ and sex‐matched normal control group, and subsequently between patients with LVNC who met the primary end points (PEPs) and secondary end points (SEPs) of the study. Study approval was obtained from the Internal Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas, USA). Consent was obtained from the patients or their family.

Study end points

The primary end point (PEP) of the study was defined as experiencing cardiac death or undergoing cardiac transplantation. The SEP was defined as developing congestive heart failure (CHF) requiring hospitalisation for medical management.

Patient analysis

Demographic data including age at diagnosis, sex, presence of a positive family history and medical treatment were collected. Twenty‐four hour Holter monitors were reviewed to determine the incidence of a significant arrhythmia, defined as ventricular tachycardia. ECGs were reviewed and abnormalities documented.

Echocardiographic studies

All patients underwent a complete two‐dimensional, spectral Doppler and colour flow Doppler examination. Patients were examined in either a resting or a sedated state (infants and children <15 kg were sedated with 50–100 mg/kg of chloral hydrate). Examinations were performed using commercial ultrasound systems (Acuson Sequoia, Siemens Medical, Mountain View, California, USA) or Sonos 5500, Philips Medical Systems, Andover, Massachusetts). Echocardiograms were recorded either digitally or on a ½‐inch vertical helical scan video tape, and were subsequently analysed by use of either internal echocardiographic system software or directly from the stored digital images.

From the apical four‐chamber view, a pulsed Doppler sample volume was placed at the mitral valve annulus and subsequently at the leaflet tips, with five cardiac cycles recorded at each site during normal respiration. The cursor was placed between the LV outflow and the mitral inflow to record the isovolumic relaxation time (IVRT). Pulmonary venous inflow was measured from the right upper pulmonary vein using colour Doppler guidance. TD acquisition was set to pulsed‐wave mode (−30 to 30 cm/s), with gain adjusted to minimise the background noise. From the four‐chamber view, a 5 mm sample volume was placed at the lateral mitral annulus, septal annulus and lateral tricuspid annulus and 5–10 cycles were recorded.

Echocardiographic analysis

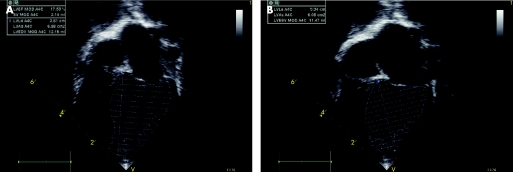

A single observer blinded to the clinical outcome of patients performed the echocardiographic analysis (CJM). Two‐dimensional measurements including left ventricular end‐diastolic diameter, left ventricular end‐systolic diameter, left ventricular posterior wall and interventricular septal thickness were obtained using M‐mode and their respective z scores calculated.16 The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was determined using the Simpson's biplane method, including the ventricular volume between the LV trabeculations (fig 1).17 Mitral inflow Doppler signals were obtained at the mitral leaflet tips and analysed for the following: peak velocity of early (E) and late (A) filling, early deceleration time and the E/A ratio.18 IVRT was measured as described previously.18 The Tei index, defined as the sum of the isovolumetric contraction time and IVRT divided by LV ejection time, was calculated as reported previously.19 Pulmonary vein inflow was analysed for peak velocity and velocity time integral of systolic (S), diastolic (D) and atrial reversal waves (Ar).15 Systolic filling fraction (systolic velocity‐time integral/total forward flow velocity‐time integral) and the pulmonary Ar‐mitral A wave duration were calculated.20 From the TD tracings, the following measurements were made: early (Ea) and late (Aa) diastolic annular velocities, and systolic velocity (Sa).21 The lateral E/Ea and septal E/Ea were also calculated.

Figure 1 Simpson's biplane method for determining left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction in patients with LV non‐compaction cardiomyopathy. (A) LV end diastolic volume. (B) LV end systolic volume.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software V.8.2. Data were expressed as mean (SD) or median (25th–75th centile) based on whether they have a normal distribution or not. Continuous variables were estimated as mean (SD) and compared with use of Student's unpaired t test (χ2 test was used for categorical variables).

Event‐free survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were assessed by means of the log rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were created using echocardiographic variables to determine predictors of the PEPs and SEPs. In the regression model for predictors, a forward stepwise programme was used to select covariates.22 The results were reported in terms of hazard ratios with 95% CI's. Multivariate logistic regression analysis and receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were used to analyse and display variables that might differentiate one group from another.23 A p value <0.05 was required for retention within the multivariate Cox regression model.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 1999 and May 2004, 56 consecutive patients with a median age of 4.8 years (range 0.3–18 years) were compared with 56 age‐ and gender‐matched controls over the same time period. For the LVNC group, the median age at diagnosis was 16 months (range 1 day–16.8 years) and median duration of patient follow‐up was 27 months (range 1–132 months). The pattern of LVNC predominantly involved the apex in 12 patients, the apex and left LV free wall in 36 patients, apex and LV posterior wall in four patients, and the apex, LV free wall and ventricular septum in four patients. The age at presentation, phenotype, symptoms and clinical outcomes did not correlate with the distribution pattern of trabeculations within the left ventricle. Nine patients had a family history of cardiomyopathy ranging from one affected family member to one family with three affected members. Of note, two patients had a family history of sudden infant death syndrome, with younger siblings affected in both cases.

Clinical presentation

Reasons for clinical presentation included cardiac murmur (n = 17), congestive heart failure (CHF; n = 14), arrhythmia (n = 7), syncope (n = 3), chest pain (n = 3), cardiomegaly on chest radiograph (n = 2), ventricular hypertrophy on ECG (n = 3), dysmorphic features (n = 2), positive family history of cardiomyopathy (n = 4) and postoperative echocardiogram (n = 1). Congenital heart defects had been corrected in seven patients (ventricular septal defect in four patients, coarctation, mitral stenosis and moderate‐sized patent ductus arteriosus, requiring transcatheter closure in one each). Arrhythmias occurred in 13 patients, including ventricular tachycardia (n = 6), supraventricular tachycardia (n = 2), atrial ectopic tachycardia (n = 3), atrial fibrillation and congenital complete atrioventricular block (n = 1 each). Two patients had inducible ventricular tachycardia and had artificial cardiac defibrillators implanted.

Echocardiography

Phenotypic heterogeneity was found among patients with LVNC with a dilated phenotype in 29 patients, hypertrophic phenotype in 10 patients, combined hypertrophic and dilated phenotype in 2 patients, “undulating phenotype” in 5 patients and 10 patients with normal LV dimensions despite classic apical trabeculation (>3 trabeculations), deep recesses and a compacted:non‐compacted ratio >2.10 The median compacted:non‐compacted ratio was 2.1 (range 1.8–2.9). The progression of phenotype among the five patients with an “undulating phenotype” included two from dilated to hypertrophic, one from normal to dilated, one from hypertrophic to dilated and one dilated phenotype which initially normalised and then reverted to a dilated phenotype.

Medical management

Outpatient medical management included the following: 40 patients treated with β‐blockade, 38 patients with angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, 30 with cardiac glycosides, 14 with diuretics and two with calcium channel blockers. In all, 26 patients were treated with a combination of a β‐blocker and an ACE inhibitor. β‐blocker treatment included long‐acting metoprolol in 30, propranolol in 7, carvedilol in 2 and sotalol in 1 patient. One patient was treated with mexilitine for long QT syndrome. Two patients did not tolerate β‐blockers and were treated with oral verapamil. Serial echocardiograms were performed in all patients while on medical treatment.

Clinical endpoints

Twelve patients met the PEP: eight patients had cardiac death and four patients underwent cardiac transplantation. Two patients required support with a ventricular assistance device before transplantation or death. Causes of cardiac death included arrhythmia in three patients and CHF in three patients, and two patients died from a combination of CHF and arrhythmia. The median age at transplantation was 8.8 years (range 1.3–15.2 years) and the median duration to transplantation from the time of diagnosis was 16 months (range 5–24 months).

In all, 25 patients met the secondary clinical end point—hospitalisation for management of CHF. Management of CHF in these patients included one or more of the following inotropic agents: low‐dose dopamine (3–5 μg/kg/min), dobutamine (5–10 μg/kg/min), milrinone (0.25–0.375 μg/kg/min) and vasopressin (0.01 U/kg/h).

Characteristics of LVNC compared with normal controls

Among patients with LVNC, tissue Doppler velocities were significantly reduced at the lateral mitral (fig 2), septal and lateral tricuspid annuli compared with those in normal controls (table 1). The LVEF was significantly reduced and the LV Tei index was increased significantly in the LVNC group compared with the normal control group.

Figure 2 Pulsed wave Doppler and tissue Doppler pattern in a patient who died of left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy (LVNC) (top panel) compared with that in a normal control (lower panel). Note the decreased lateral mitral Ea velocity (Ea = 4 cm/s) in a child who died of LVNC (top frame) compared with that in a normal control (Ea = 20 cm/s; bottom frame).

Table 1 Echocardiographic and tissue Doppler characteristics of children with left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy compared with normal controls.

| Variable | Normal | LVNC | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitral Ea | 17.0 (3.2) | 11.0 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Mitral Aa | 6.8 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Mitral Sa | 8.8 (2.5) | 7.3 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Septal Ea | 13.0 (2.9) | 8.9 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Septal Aa | 6.3 (1.0) | 5.5 (1.2) | 0.003 |

| Septal Sa | 7.7 (1.1) | 6.5 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| E/Ea lateral | 6.0 (1.6) | 8.8 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| E/Ea septal | 6.8 (1.3) | 10.6 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| LV Tei | 0.28 (0.06) | 0.49 (0.13) | <0.001 |

| LVEF | 62 (11) | 36 (11) | <0.001 |

Aa, late diastolic tissue Doppler velocity; Ea, early diastolic tissue Doppler velocity; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Sa, systolic tissue Doppler velocity.

Data are expressed as median (SD).

Predictors of the PEP

Using univariate log rank test, LVEF, lateral mitral Ea velocity, septal Ea velocity and lateral mitral E/Ea predicted patients meeting the PEP (table 2). However, after applying multivariate Cox analysis, only the lateral mitral Ea predicted patients meeting the PEP (table 3). Using a lateral mitral Ea cut‐off point of 7.8 cm/s provided 87% sensitivity and 79% specificity for meeting the PEP. Freedom from death or cardiac transplantation was 85% at 1 year and 77% at 2 years. Age at presentation did not correlate with the PEP (odds ratio (OR) 1.039, 95% CI 0.940 to 1.149, p value = 0.45).

Table 2 Predictors of patients with left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy reaching primary and secondary endpoints using univariate log rank test.

| Group | SD | χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEP | |||

| Univariate analysis | |||

| LVEF | 42.19 | 11.44 | 0.001 |

| Lateral mitral Ea | 13.71 | 14.17 | 0.001 |

| Septal Ea | 9.91 | 9.03 | 0.003 |

| Lateral mital E/Ea | 11.39 | 9.42 | 0.002 |

| SEP | |||

| Univariate Analysis | |||

| LVEF | 58.15 | 7.68 | 0.0067 |

| Lateral mitral Ea | 19.73 | 12.52 | 0.044 |

| Lateral mitral Sa | 12.58 | 4.42 | 0.036 |

| Mitral septal Ea | 14.90 | 5.85 | 0.016 |

| Lateral mitral E/Ea | 15.51 | 9.09 | 0.003 |

E, early mitral velocity; Ea, early diastolic tissue Doppler velocity; Sa, systolic tissue Doppler velocity; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 3 Predictors of patients with left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy reaching primary and secondary endpoints using multivariate Cox regression.

| Group | p Value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEP | |||

| Lateral mitral Ea | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.53 to 0.85 |

| SEP | |||

| Lateral mitral Ea | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.72 to 0.91 |

Predictors of the SEP

Using univariate log rank test, LVEF, lateral mitral Ea velocity, lateral mitral Sa velocity, septal Ea velocity and lateral mitral E/Ea were predictive of patients reaching the SEP (table 2). However, using multivariate Cox analysis, only the lateral mitral Ea velocity predicted patients meeting the SEP (table 3). Freedom from hospitalisation for CHF was 64% at 1 year and 57% at 2 years.

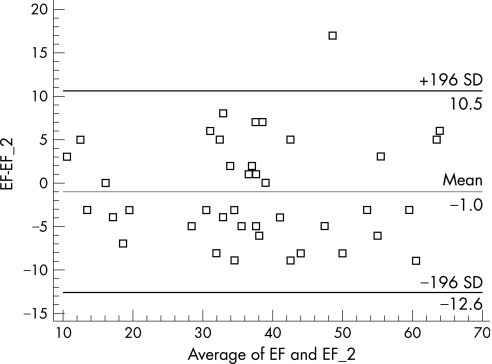

Using ROC curves (fig 3), the mitral Ea proved the most sensitive and specific predictor for meeting the PEP at 1 year (area under the curve = 0.888, SE = 0.048, 95% CI 0.775 to 0.956) and 2 years (area under the curve = 0.822, SE = 0.06, 95% CI 0.697 to 0.911) after the diagnosis (table 4).

Figure 3 Receiver operator characteristic curves comparing variables (mitral Ea, LVEF, LV Tei and E/Ea) in predicting patients who meet the primary end point at 1 year after diagnosis.

Table 4 Receiver operator characteristic curves for patients meeting the primary end point at 1 years and 2 years after the time of diagnosis.

| Variable | AUC | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year after diagnosis | |||

| LVEF | 0.816 | 0.067 | 0.690 to 0.907 |

| Lateral mitral Ea* | 0.888 | 0.048 | 0.775 to 0.956 |

| LV Tei | 0.716 | 0.108 | 0.580 to 0.829 |

| Lateral mitral E/Ea | 0.789 | 0.100 | 0.659 to 0.887 |

| 2 years after diagnosis | |||

| LVEF | 0.813 | 0.062 | 0.686 to 0.905 |

| Lateral mitral Ea* | 0.822 | 0.060 | 0.697 to 0.911 |

| LV Tei | 0.694 | 0.096 | 0.556 to 0.810 |

| Lateral mitral E/Ea | 0.721 | 0.094 | 0.585 to 0.833 |

E, early mitral velocity; Ea, early diastolic tissue Doppler velocity; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Discussion

With the recent recognition of LVNC as a unique form of cardiomyopathy, it becomes important to determine non‐invasive prognostic factors for adverse clinical outcomes in this disease. This is further emphasised by the frequency of this disorder, recently reported to be as high as 9–10% among all patients with cardiomyopathy.24,25 Our study has shown that the lateral mitral Ea velocity helps predict children with LVNC at risk of death or need for transplantation at 1 and 2 years after diagnosis. The lateral mitral Ea velocity also best predicted those children who were hospitalised for management of CHF.

Predictors of PEP

Although several variables including LVEF, lateral mitral Ea, lateral mitral E/Ea ratio and LV Tei index were significantly different in patients who met the PEP, the lateral mitral Ea velocity was most predictive after comparing these variables using ROC curves. Previously we have shown that in children with HCM, the septal E/Ea ratio predicted children at risk of death, cardiac transplantation or ventricular tachycardia.13 These findings are interesting in that the disease process in HCM predominantly involves the septum, whereas in the current study patients with LVNC predominantly manifested trabeculations at the apex and LV free wall. Considering the results of this study and the previous HCM study,13 tissue Doppler velocities seem to have clinical utility in helping predict adverse clinical outcomes in patients irrespective of type of cardiomyopathy. Whereas elevated E/Ea ratios may reflect increased left heart filling pressures or more advanced myocardial disease in patients with HCM, among patients with LVNC decreased mitral Ea velocities may reflect greater involvement of the lateral left ventricular myocardium by the disease process. This was true in this study population, as evidenced by the predominant involvement of the apex and LV free wall by trabeculations.

A previous report of 54 children with DCM showed by multivariate analysis that the tricuspid Ea velocity and LVEF predicted patients who met the PEP in that study.14 Given that the majority of patients with LVNC in this study had a dilated phenotype, one might have expected the tricuspid Ea velocities or LVEF to have predicted the PEP. Interestingly, using ROC curves at 2 years after diagnosis, the LVEF was shown to be close to lateral mitral Ea velocity in predicting the PEP. However, LVNC and DCM represent two different disease entities, and their natural history and haemodynamic characteristics may be different. The former point has been highlighted by several studies, pointing out that a subset of patients with LVNC may present with an “undulating” phenotype, with an improvement in LVEF followed by deterioration at a later date.10 Irrespective of this, LVEF is an important index of systolic function in predicting adverse outcomes in children with LVNC and DCM.

Nagueh et al15 and Garcia et al26 demonstrated among adult patients with and without HCM that the lateral E velocity/Ea or E velocity/flow propagation velocity correlates well with left heart filling pressures. Elevated left heart filling pressures may have accounted for those patients with LVNC who had adverse clinical outcomes in this study, although this was not verified by cardiac catheterisation.

Predictors of the SEP

Although patients who met the SEP had significant differences in LVEF, lateral mitral Ea velocity, lateral mitral Sa velocity and lateral mitral E/Ea, only the lateral mitral Ea velocity proved significant by multivariate Cox regression. Measurement of LVEF is difficult in patients who have a dilated phenotype, and this is further hampered in LVNC by the presence of multiple trabeculations, which requires tracing into the recesses between these projections. However, the reproducibility of LVEF with two readers was good in this study (fig 4). Although four patients had clinical improvement after initially presenting with depressed LVEF, when taking the entire patient cohort into account, LVEF was less sensitive than lateral mitral Ea in predicting the need for hospitalisation for CHF.

Figure 4 Bland–Altman plot showing scatter of ejection fraction calculation between two observers.

Limitations

Use of Simpson's rule to measure LVEF in patients with LVNC may prove difficult, and this test additionally assumes that the left ventricle has a geometrical shape. Satisfactory pulmonary vein recordings were available only in 32 (57%) patients to measure Ar duration. Ideally, simultaneous cardiac catheterisation with determination of left ventricular filling pressures would have allowed correlation with lateral E/Ea velocities, but this is neither practical nor practised in the majority of young children. Other Doppler variables including E/flow propagation velocity, previously shown to correlate with left heart filling pressures in both adults and children, may have proven clinically useful but were not obtained in this study.15,27 Prior studies have shown E/Ea ratio to be more accurate than flow propagation in predicting filling pressures than flow propagation.15

Conclusions

Patients with LVNC have significantly different tissue Doppler profiles than normal controls. Tissue Doppler velocities, specifically the lateral mitral Ea velocity, may help discriminate patients with LVNC at potential risk of death, need of cardiac transplantation and hospitalisation for the management of congestive heart failure. It is important to highlight that such variables be taken into account in concert with older more established measures of left ventricular systolic function such as ejection fraction. Equally important is the search for other measures of ventricular systolic and diastolic function such as strain and strain rate imaging in children with cardiomyopathy.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

Aa - late diastolic annular velocity

ACE - angiotensin‐converting enzyme

CHF - congestive heart failure

DCM - dilated cardiomyopathy

Ea - early diastolic annular velocity

HCM - hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

IVRT - isovolumic relaxation time

LV - left ventricular

LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction

LVNC - left ventricular non‐compaction cardiomyopathy

PEP - primary end point

ROC - receiver operator characteristic

Sa - systolic tissue Doppler velocity

SEP - secondary end point

TD - tissue Doppler

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Towbin J A, Bowles N E. The failing human heart. Nature 2002415227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin T K, Perloff J K, Williams R G.et al Isolated left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation 199082507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson P, McKenna W, Bristow M.et al Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the definition and classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation 199693841–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenni R, Goebel N, Tartini R.et al Persisting myocardial sinusoids of both ventricles as an isolated anomaly; echocardiographic, angiographic and pathologic anatomical findings. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 19869127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oechslin E N, Attenhofer Jost C H, Rojas J R.et al Long‐term follow‐up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: a distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 200036493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichida F, Hamamichi Y, Miyawaki T.et al Clinical features of isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium: long‐term clinical course, hemodynamic properties, and genetic background. J Am Coll Cardiol 199934233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stollberger C, Finsterer J. Left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 20041791–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stollberger C, Finserer J, Blazek G. Left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction and association with additional abnormalities and neuromuscular disorders. Am J Cardiol 200290899–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neudorf U E, Hussein A, Trowitzsch E.et al Clinical features of isolated noncompaction of the myocardium in children. Cardiol Young 200111439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pignatelli R H, McMahon C J, Dreyer W J.et al Clinical characterization of left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy in children: a relatively common form of cardiomyopathy. Circulation 20031082672–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson M J, Sonnenberg B, Woo A.et al Long‐term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 200239638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumura Y, Elliott P M, Virdee M S.et al Left ventricular diastolic function assessed using Doppler tissue imaging in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: relation to symptoms and exercise capacity. Heart 200287247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon C J, Nagueh S F, Pignatelli R H.et al Characterization of left ventricular diastolic function by tissue Doppler imaging and clinical status in children with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 20041091756–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon C J, Nagueh S F, Eapen R.et al Predictors of adverse clinical events in children with dilated cardiomyopathy: a prospective clinical study. Heart 200490908–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagueh S F, Lakkis N M, Middleton K J.et al Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressures in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 199999254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Silverman NH, ed. Quantitative methods to enhance morphological information using ultrasound [chapter 2]. Pediatric echocardiography. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 199335–108.

- 17.Silverman N H, Ports T A, Snider A R.et al Determination of left ventricular volume in children: echocardiographic and angiographic comparisons. Circulation 198062548–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulvagh S, Quinones M A, Kleiman N S.et al Estimation of left ventricular end‐diastolic pressure from Doppler transmitral flow velocity in cardiac patients independent of systolic performance. J Am Coll Cardiol 199220112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harada K, Tamura M, Toyono M.et al Comparison of right ventricular Tei index by tissue Doppler imaging to that obtained by pulse Doppler in children without heart disease. Am J Cardiol 200290566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuecherer H F, Muhiudeen I A, Kusumoto F M.et al Estimation of mean left atrial pressure from transesophageal pulsed Doppler echocardiography of pulmonary venous flow. Circulation 1990821127–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagueh S F, Middleton K J, Kopelen H A.et al Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997301527–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox D R, Oakes D.Analysis of survival data. London: Chapman and Hall, 1984

- 23.Pepe M S.The statistical evaluation of medical tests for classification and prediction. UK: Oxford University Press, 200367–92.

- 24.Nugent A W, Daubeney P E, Chondros P.et al National Australian Childhood Cardiomyopathy Study. The epidemiology of childhood cardiomyopathy in Australia. N Engl J Med 20033481639–1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipshultz S E, Sleeper L A, Towbin J A.et al The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N Engl J Med 20033481647–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia M J, Ares M A, Asher C.et al An index of early left ventricular filling that combined with peak E velocity may estimate capillary wedge pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol 199729448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Border W L, Michelfelder E C, Glascock B J.et al Color M‐mode and Doppler tissue evaluation of diastolic function in children: simultaneous correlation with invasive indices. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 200316988–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.