Abstract

Objective

To determine the efficacy of pharmacological treatment in the prevention of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

Design

Clinical outcome was assessed retrospectively in 293 patients with HCM, including 173 who were taking cardioactive medications.

Setting

Department of Cardiology, University of Padua, Padua, Italy; a tertiary HCM Centre.

Interventions

Medical treatment with β blockers, verapamil, sotalol and amiodarone.

Main outcome measure

HCM‐related sudden cardiac death.

Results

17 of 173 (10%) patients died suddenly or had aborted cardiac arrest, while being treated continuously with drugs having antiarrhythmic properties, over a period of 62 (56) months. Sudden death occurred in 20% of patients administered amiodarone (6/30), 9% each of patients taking verapamil (4/46) or β blockers (7/76), and 0% of those taking sotalol (0/21). Patients taking cardioactive drugs (n = 173) and those without pharmaceutical therapy (n = 120) did not differ with respect to sudden death mortality.

Conclusion

Medical treatment is not absolutely protective against the risk of sudden death in HCM. The present data inferentially support the use of the implantable defibrillator as the primary treatment choice for prevention of sudden death in high‐risk patients with HCM.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic heart disease with diverse natural history.1,2 The highly visible consequence of sudden cardiac death, often in asymptomatic or only mildly symptomatic individuals, is recognised as its most devastating and unpredictable complication.1,2,3,4 Prevention of sudden death remains an important challenge, and over the past 5 years the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) has been promoted for both primary and secondary prevention in selected patients.5,6 However, there are some patients in whom decisions for life‐long device therapy raise certain clinical reservations and considerations for alternative pharmacological treatment. Therefore, this is an opportune time to study a large population with HCM followed for a substantial period of time, to assess the level of protection afforded by the drugs traditionally used in this disease.

Selection of patients

Over a 21‐year period between 1980 and 2001, 293 patients with HCM were consecutively evaluated at the University of Padua, Padua, Italy, for a period of time preceding the large‐scale introduction of ICDs for high‐risk patients with HCM at our institution. At initial evaluation, the 293 patients were aged 1–79 years (mean (SD) 44 (18) years); 191 (65%) were male. Maximum (SD) left ventricular wall thickness was 22 (6) mm; and 65 (22%) patients had left ventricular outflow tract gradients ⩾30 mm Hg at rest.

Results

Of the 293 patients, 173 were treated with drugs previously advanced for prophylactic use in HCM (alone or in combination), for symptom relief and/or prevention of sudden death: amiodarone, sotalol, β blockers or verapamil. Mean (SD) standard daily doses of drugs (based on body surface area for the 39 children aged <18 years) were for amiodarone, sotalol and verapamil: 197 (16), 207 (66) and 248 (95) mg, respectively; and for propranolol, atenolol, metoprolol and acebutolol: 155 (95), 82 (25), 110 (60) and 400 (200) mg, respectively.

During the follow‐up period of 7 (6) years, 17 of 173 (10%) patients treated only with drugs unexpectedly died (n = 14) or had an aborted cardiac arrest (n = 3; table 1). Of these 17 patients, 16 had experienced either no or only mild symptoms of heart failure prior to their event. Notably, these 17 patients with sudden death events had been continuously treated medically throughout the follow‐up period from diagnosis to the time of death with the following drugs in standard doses over 62 (56) months: amiodarone alone or in combination with either β blockers or verapamil (n = 6); β blockers alone (n = 7); verapamil alone (n = 4; table 1).

Table 1 Clinical and morphological data in 17 patients with sudden death (or cardiac arrest) while being treated with cardioactive medications.

| Patient | Sex | Age at initial evaluation (years) | Age at death (years) | Family SCD | Syncope | Max LV thickness (mm) | LV outflow gradient (rest) | Last NYHA class | AF | NSVT (Holter) | Drugs (dose in mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 12 | 23 | + | 0 | 36 | 46 | I | 0 | + | Amiodarone (200) and propranolol (240) |

| 2 | M | 16 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0 | I | 0 | 0 | Verapamil (160) |

| 3 | F | 17 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | II | 0 | + | Acebutolol (400) |

| 4 | M | 24 | 25 | + | + | 28 | 82 | I | 0 | 0 | Amiodarone (200) and propranolol (160) |

| 5 | F | 27 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 24 | I | 0 | 0 | Acebutolol (400 |

| 6 | M | 30 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | II | + | 0 | Propranolol (240) |

| 7 | F | 39 | 41 | + | 0 | 25 | 120 | II | 0 | – | Verapamil (400) |

| 8 | F | 43 | 51 | 0 | + | 25 | 88 | I | + | 0 | Amiodarone (200) and verapamil (240) |

| 9 | M | 43 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 36 | I | 0 | + | Propranolol (120) |

| 10 | M | 44 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 50 | I | 0 | 0 | Propranolol (240) |

| 11 | M | 46 | 49* | + | + | 21 | 0 | II | 0 | + | Carvedilol (37.5) |

| 12 | M | 55 | 58 | + | 0 | 24 | 18 | I | + | – | Verapamil (240) |

| 13 | F | 59 | 60* | 0 | + | 22 | 56 | I | 0 | 0 | Atenolol (100) |

| 14 | F | 63 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 55 | I | + | 0 | Verapamil (240) |

| 15 | F | 69 | 71 | + | + | 27 | 16 | I | + | 0 | Amiodarone (200) |

| 16 | M | 42 | 63 | + | 0 | 21 | 0 | I | + | + | Amiodarone (200) and propranolol (240) |

| 17 | F | 6 | 37* | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | III | 0 | + | Amiodarone (200) and carvedilol (12.5) |

AF, atrial fibrillation; F, female; LV, left ventricular; M, male; max, maximum; NSVT, non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SCD, sudden cardiac death; +, present; 0, absent; –, data not available.

*Aborted SCD.

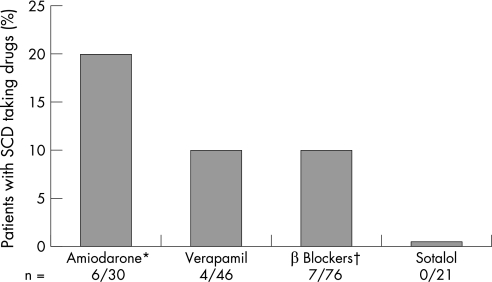

Drugs had been administered to the 17 patients with sudden death events for high‐risk status based on the presence of one or more risk markers (13),1,2,4,7 or primarily to control symptoms of heart failure or recurrent atrial fibrillation (4). Of the 173 medically treated patients, the following proportions died suddenly: amiodarone (6 of 30; 20%), verapamil (4 of 46; 9%), β blockers (7 of 76; 9%) and sotalol (0 of 21; 0%; fig 1).

Figure 1 Probability of sudden death among patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy despite their medical treatment with amiodarone, verapamil, β blockers or sotalol, continuously during the follow‐up period from initial diagnosis to the end of follow‐up. *Amiodarone, including patients also taking β blockers (n = 9), verapamil (n = 6) and sotalol (n = 1). †β Blockers, but also including three patients taking verapamil. SCD, sudden cardiac death.

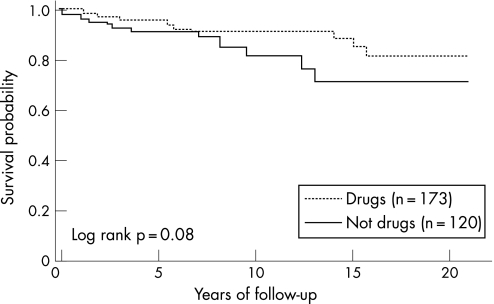

Overall, patients taking cardioactive drugs (n = 173) and patients without pharmacological treatment (n = 120) did not differ significantly with respect to sudden death mortality (fig 2). Also, patients taking amiodarone, β blockers, verapamil and sotalol did not differ with respect to age, sex, left ventricular wall thickness and outflow obstruction, although the risk factor burden (ie, level of risk) in patients taking amiodarone and sotalol was significantly higher than in patients taking β blockers and verapamil (table 2).

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier curves depicting freedom from sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy taking cardioactive medications (amiodarone, β blockers, verapamil or sotalol), compared with those without pharmacological treatment.

Table 2 Demographics and risk factor burden with respect to drug therapy in 173 patients with patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

| Drug | Number of patients | Mean (SD) age (years) | Male sex, n (%) | Max (SD) LV thickness (mm) | LV outflow gradient ⩾30 mm Hg at rest, n (%) | Risk factor burden (avg risk factors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | 30 | 54 (19) | 18 (60) | 24 (6) | 7 (27) | 1.33 (1.0)* |

| β Blocker | 76 | 55 (18) | 52 (68) | 23 (6) | 30 (39) | 0.75 (0.9) |

| Verapamil | 46 | 55 (18) | 26 (56) | 23 (6) | 14 (30) | 0.65 (0.8) |

| Sotalol | 21 | 52 (15) | 12 (57) | 23 (7) | 5 (24) | 1.33 (0.9)† |

Avg, average; LV, left ventricular.

*Amiodarone versus verapamil (p = 0.002) and amiodarone versus β blocker (p = 0.005).

†Sotalol versus β blocker (p = 0.01) and sotalol versus verapamil (p = 0.003).

Of the 13 patients who received ICDs for primary or secondary prevention, only 1 patient, who had previously survived a cardiac arrest, experienced an appropriate discharge (patient 17 in table 1). Thirteen other study patients died, including nine from progressive heart failure (two with systolic dysfunction) or stroke related to HCM and four from non‐cardiac causes.

Discussion

HCM is the most common cause of sudden death in the young and the prevention of unexpected cardiac arrest has been a treatment aspiration for decades.1,2,5,8,9,10 Drugs such as amiodarone, β blockers and calcium antagonists, as well as type I‐A agents (eg, quinidine and procainamide) had been the mainstay of this strategy for many years.2,8,9,10 However, in 2000, the ICD was introduced for prevention of sudden death in HCM, and subsequently proved to be a highly effective treatment intervention.5,11 It is our perception that some clinicians have been slow to adopt the ICD as a primary prevention treatment for young high‐risk patients with HCM, emphasising instead the acknowledged potential complications of device therapy such as inappropriate discharges, infection and lead problems, which could occur over the many decades that young patients with an ICD would be exposed. Such considerations have led some investigators to continue advocating the use of alternative pharmacological measures with antiarrhythmic agents (such as low‐dose amiodarone) for the primary prevention of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death in patients with HCM.9,12,13

However, in this study, we have shown that prevention of sudden death in HCM afforded by antiarrhythmic drugs such as amiodarone, as well as β blockers and verapamil, is incomplete. Indeed, such primary pharmacological strategies did not provide absolute protection against sudden death, which is a fundamental aspiration for young patients with HCM,1,2,5,7,11 nor have such drugs compared favourably with the proven efficacy of the ICD in preventing sudden cardiac death.5,6 Indeed, 10% of patients taking drugs, and specifically 20% of patients taking amiodarone, experienced sudden death. Notably, the high rate of sudden death associated with amiodarone may be due, in part, to the greater risk burden identified in these patients.

Although our data do not support the chronic administration of an antiarrhythmic agent such as amiodarone as a primary strategy for prevention of sudden death, this drug is nevertheless frequently used in HCM for suppression of recurrent atrial fibrillation and in association with defibrillator therapy to minimise inappropriate shocks.2,14

None of our 21 patients treated with sotalol died suddenly, suggesting a possible benefit for prevention of sudden death attributable to the drug.14 This observation is noteworthy because the risk level of the patients taking sotalol was significantly higher than in those taking β blockers or verapamil. Nevertheless, owing to the uncontrolled and retrospective nature of the present study design, a large measure of restraint is appropriate before conclusions can be drawn regarding the role of sotalol in the prevention of sudden death in HCM.

In conclusion, pharmacological treatment is not absolutely protective against sudden death in HCM. These data serve to support the ICD as the treatment of choice for primary or secondary prevention in high‐risk patients with HCM.

Abbreviations

HCM - hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

ICD - cardioverter defibrillator

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Italian Ministry for Scientific and Technologic Research (MURST‐COFIN 2002 prot 2002065749 002).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Maron B J. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAMA 20022871308–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maron B J, McKenna W J, Danielson G K.et al American College of Cardiology/European Society of Cardiology clinical expert consensus document on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003421687–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maron B J, Olivotto I, Spirito P.et al Epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy‐related death. Revisited in a large non‐referral‐based patient population. Circulation 2000102858–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott P M, Poloniecki J, Dickie S.et al Sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: identification of high risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000362212–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maron B J, Shen W ‐ K, Link M S.et al Efficacy of implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators for the prevention of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000342365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayatilleke I, Doolan A, Ingles J.et al Long‐term follow‐up of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2004931192–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maron B J, Estes NAM I I I, Maron M S.et al Primary prevention of sudden death as a novel treatment strategy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 20031072872–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Montereggi A.et al Prognostic value of non‐sustained ventricular tachycardia and the potential role of amiodarone treatment in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy assessment in an unselected non‐referral based patient population. Heart 199879331–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKenna W J, Oakley C M, Krikler D M.et al Improved survival with amiodarone in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and ventricular tachycardia. Br Heart J 198553412–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Östman‐Smith I, Wettrell G, Riesenfeld T. A cohort study of childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: improved survival following high‐dose β‐adrenoceptor antagonist treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999341813–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maron B J, Spirito P, Haas T S, for the ICD in HCM Investigators Efficacy of the implantable defibrillator for prevention of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: data form the international registry of 506 high risk patients [abstract]. Circulation 2005112(Suppl II)531 [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKenna W J, Behr E R. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: management, risk stratification, and prevention in sudden death. Heart 200287169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott P, McKenna W J. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet 20043631881–1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pacifico A, Hohnlose S H, Williams J H.et al Prevention of implantable‐defibrillator shocks by treatment with sotalol. N Engl J Med . 1999;3401855–1862. [DOI] [PubMed]