Abstract

Objective

To examine the source of observed lower risk-adjusted mortality for blacks than whites within the Veterans Affairs (VA) system by accounting for hospital site where treated, potential under-reporting of black deaths, discretion on hospital admission, quality improvement efforts, and interactions by age group.

Data Sources

Data are from the VA Patient Treatment File on 406,550 hospitalizations of veterans admitted with a principal diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, hip fracture, gastrointestinal bleeding, congestive heart failure, or pneumonia between 1996 and 2002. Information on deaths was obtained from the VA Beneficiary Identification Record Locator System and the National Death Index.

Study Design

This was a retrospective observational study of hospitalizations throughout the VA system nationally. The primary outcome studied was all-location mortality within 30 days of hospital admission. The key study variable was whether a patient was black or white.

Principal Findings

For each of the six study conditions, unadjusted 30-day mortality rates were significantly lower for blacks than for whites (p < 0.01). These results did not vary after adjusting for hospital site where treated, more complete ascertainment of deaths, and in comparing results for conditions for which hospital admission is discretionary versus nondiscretionary. There were also no significant changes in the degree of difference by race in mortality by race following quality improvement efforts within VA. Risk-adjusted mortality was consistently lower for blacks than for whites only within the population of veterans over age 65.

Conclusions

Black veterans have significantly lower 30-day mortality than white veterans for six common, high severity conditions, but this is generally limited to veterans over age 65. This differential by age suggests that it is unlikely that lower 30-day mortality rates among blacks within VA are driven by treatment differences by race.

Keywords: Hospital mortality, racial disparities, hospitals, veterans

In contrast to an extensive literature documenting worse health outcomes among blacks than whites throughout the health care system (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2002), a number of studies of veterans hospitalized in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system have found either that blacks have better outcomes than whites (Jha et al. 2001; Deswal et al. 2004) or that there are no race/ethnicity based disparities in patient outcomes (Horner et al. 2002; Petersen et al. 2002; Freeman et al. 2003; Goldstein et al. 2003; Selim et al. 2004).

There are several potential reasons why clinical care and outcomes may be relatively more favorable toward blacks within VA than in the rest of the U.S. health care system. White and black veterans who use VA are much more homogeneous in terms of socioeconomic status than whites and blacks outside the VA system. As socioeconomic status has been shown to have a large impact on health (Lynch and Kaplan 2001; Adler and Newman 2002; Marmot 2002) and to account for some (but not all) racial disparities in health (Geronimus et al. 1996; Carlisle, Leake, and Shapiro 1997; Shen, Wan, and Perlin 2001; Goldman and Smith 2002), this homogeneity could explain why racial disparities might be smaller within the VA. In addition, because blacks in the United States on average have lower incomes and are less likely to have health insurance than whites (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2002), the public funding of care in the VA should act to reduce racial disparities. Finally, the military has played an important role within American society in bringing about desegregation (Moskos and Butler 1997), and the better integration of minorities within the military may be reflected in more equal treatment of racial minorities within the VA.

However, while some studies have found equal outcomes between blacks and whites within VA, the observation of better outcomes among blacks remains unexplained (Hermos et al. 2001; Mark 2001). There are at least five potential explanations for better outcomes among blacks that require further examination.

First, recent work has found that differential sorting into quality hospitals may explain racial differences in treatment and outcome (Barnato et al. 2005). It is possible that such sorting could account for the better outcomes among blacks if blacks are more likely to be admitted to VA hospitals with better outcomes. Hospital effects were not considered in previous studies of racial differences in the VA.

Second, previous studies (Jha et al. 2001) have used the VA Beneficiary Identification Record Locator System Death File (BIRLS) and in-hospital data to measure deaths. Death rate ascertainment with BIRLS has been considered to have an accuracy rate of about 95 percent (Fisher, Weber, and Goldberg 1995; Cowper et al. 2002), but it is unclear whether inaccuracy in the BIRLS data varies by race. Thus, confirming that previous findings were not due to incomplete ascertainment of death among blacks would be important.

Third, if blacks have more limited access to outpatient care because of either geographic location or fewer resources to use outside facilities (Pappas et al. 1997; Basu and Clancy 2001), they may be more likely than whites to be hospitalized for conditions that could have been treated in outpatient settings. Therefore, among conditions for which hospital admission is discretionary, higher admission rates among blacks could result in lower observed mortality rates because the average hospitalized black patient would be less severely ill. Examination of conditions for which hospital admission is not discretionary would likely address this potential bias (Miller et al. 1994). Fourth, the studies that found better outcomes for black veterans were based on hospital discharges that occurred before the significant reforms undertaken within the VA health care system in the mid-1990s (Jha et al. 2003). As quality improvement may target the worst performing groups within a system (Sequist et al. 2006), it is plausible that such reforms may have led to a reduction in the mortality difference between blacks and whites. As a consequence of the changes in the VA health care system, the racial differences in mortality observed in the mid-1990s may no longer exist. Finally, differential selection into the VA by race may be a mechanism for lower VA mortality among blacks. Given that selection into VA may be based on financial barriers to non-VA care and that Medicare reduces these financial barriers for those over 65, if selection matters we would expect racial differences in mortality within VA to be different in the over age 65 and under age 65 populations.

We undertook an analysis to determine if racial disparities in 30-day mortality exist for veterans hospitalized within VA from FY1996 to FY2002 for three conditions for which hospital admission is nondiscretionary (acute myocardial infarction [AMI], hip fracture, and stroke), and for three conditions for which hospital admission is discretionary (congestive heart failure [CHF], gastrointestinal bleeding [GI bleed], and pneumonia). We estimated racial differences in mortality for each of these six conditions and extended previous work by examining whether (1) between-site variation or (2) more complete ascertainment of death accounted for the observed differences in race-specific mortality; (3) racial differences in outcomes were similar for conditions for which admission is or is not discretionary; (4) racial differences persisted over time; and (5) effects were similar in the subgroups under and over 65 years of age.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Philadelphia VA Medical Center and the University of Pennsylvania.

Data

Our primary data source was hospital discharge data from the VA Patient Treatment File (PTF) for FY1996–FY2002. The PTF contains information about primary and secondary diagnoses, age, gender, discharge disposition, transfer status, length of stay, patient's zip codes, and race and means test eligibility for every hospital discharge within the Veterans Health Administration. The initial analysis included all deaths identified in the PTF and BIRLS within 30 days of hospital admission. Date of death was verified with the National Death Index (NDI) for all veterans with evidence of death in either the PTF or BIRLS and all veterans with unknown vital status 30 days after each admission (i.e., no active follow-up within the VA system). The 2000 Census was the source for socioeconomic characteristics, which were linked to the PTF records using the patient's zip code of residence (Geronimus, Bound, and Neidert 1996; Geronimus and Bound 1998; Fiscella and Franks 2001).

Patient Population

We used the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research's (AHRQ's) Quality Indicator report to identify six conditions for which mortality was considered an important indicator of quality: AMI, hip fracture, stroke, CHF, GI bleed, and pneumonia (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2002). The first three of these are conditions for which hospital admissions are largely nondiscretionary while the last three are generally considered more discretionary.

There were 521,497 hospitalizations in 138 VA hospitals between FY1996 and FY2002 for veterans with the six study conditions. These 138 hospitals were combined into 120 sites by grouping together hospitals that merged over the time period of the study. We limited our analysis to whites and blacks due to the relatively small numbers of nonblack minorities and less reliable coding of other races (Kressin et al. 2003). We excluded hospitalizations for patients who were < 18 years old (N = 1), nonveterans (N-2,024), treated at facilities or resident outside of the 50 states (N = 11,451), admitted to nonacute facilities (N = 24,239), readmitted within 30 days with the same condition (N = 30,781), admitted after hospital transfer (N = 14,204), female (N = 10,188), of Hispanic (either white or black) or “other” race (N = 30,719), or missing a code for race (N = 18,270). Hospitalizations could be excluded for more than one of these reasons. Our study sample of index admissions for the six conditions consisted of N = 406,550 hospitalizations involving 284,974 veterans at 120 sites. The same patient could be hospitalized multiple times for either the same or a different condition. All analyses were condition-specific, and repeated hospitalizations for the same patient for the same condition were considered to be conditionally independent. The unit of analysis is the hospitalization, with patients being “at risk” for mortality within 30 days of admission each time they are admitted.

Outcomes and Predictor Variables

The primary outcome was mortality within 30 days of hospital admission. For the six study conditions considered, mortality has been shown to vary substantially across institutions and high mortality may be associated with deficiencies in the quality of care (Meehan et al. 1995; Perez et al. 1995; Rockall et al. 1995; Romano, Luft, and Remy 1996). Mortality at 30 days has been used as a hospital quality indicator for these conditions by many state health organizations, hospital consortiums, and hospital associations (Geronimus, Bound, and Neidert 1996). Our key independent variable was an indicator variable denoting black race as recorded in the PTF.

We considered five types of adjustment variables: age, comorbidity, year of discharge, characteristics related to the patient's socioeconomic status, and the hospital where admitted. We adjusted for comorbidity using the 30 comorbidities defined by Elixhauser et al. (1998); this approach has shown better discrimination than other approaches to risk adjustment using administrative data (Stukenborg, Wagner, and Connors 2001; Southern, Quan, and Ghali 2004). The socioeconomic status variables included VA-defined means test eligibility and Census-based zip code level indicators. The VA uses the low-income geographic-based income limits set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center 2003). Veterans are eligible if income does not exceed 80 percent of the median family income for the geographic area (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2003) or if they have a service-connected disability >10 percent. We also included adjustments for percentage of population with college degrees, percent urban, and mean household income within each patient's zip code of residence.

Model Specification

For each of the six conditions we modeled mortality as a function of race and the other adjustment variables using logistic regression. To assess the effect of age, comorbidity, calendar time, socioeconomic status, and site on the association between race and mortality, we added each type of adjustment variable to the fixed effects part of the model in sequence. The assumed linearity of age was verified using linear splines as well as polynomial terms. As part of a sensitivity analysis, we added deaths within 30 days identified from the NDI, and accounted for hospital site using a random effects logistic regression model. The fixed effects models were fit using Stata SE 9.1 and the random effects models were fit using second-order penalized quasilikelihood (PQL2) implemented in MLwiN 2.02. PQL2 is the most accurate quasilikelihood approach for binary data (Goldstein 2003). To assess a possibly differential time trend, we added an interaction term between time and race to the final model for each of the six conditions. This analysis was repeated on two patient subgroups of a priori interest, veterans under and over age 65; linear age terms were retained to allow for increasing mortality with age even within these age-defined subgroups.

RESULTS

For our study sample of 406,550 hospitalizations, 87,929 (21.6 percent) involved black patients (Table 1). Blacks comprised 28.5 percent of the patients under age 65 and 18.7 percent of patients over age 65. The mean age of blacks and whites was 65.9 and 69.7 years, respectively. In this study population, the most prevalent conditions were pneumonia and CHF and the least prevalent was hip fracture. The relative proportion of blacks varied by condition from 12.4 percent for hip fracture, 14.0 percent for AMI, and 19.5 percent for pneumonia to 24.4 percent for GI bleed, 25.3 percent for CHF, and 26.3 percent for stroke. Similar proportions of white and black veterans were admitted in each year.

Table 1.

Race-Specific Distributions of Baseline Characteristics at Each Hospitalization, Overall and for Veterans under and over Age 65

| Overall | Under Age 65 | Over Age 65 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (n = 87,929) | White (n = 318,621) | Black (n = 34,953) | White (n = 87,685) | Black (n = 52,976) | White (n = 230,936) | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 65.9 (13.0) | 69.7 (11.2) | 52.3 (7.4) | 54.9 (6.8) | 74.8 (6.6) | 75.3 (6.5) |

| Conditions (n) | ||||||

| AMI | 7,194 | 44,028 | 3,118 | 16,414 | 4,076 | 27,614 |

| Hip fracture | 1,791 | 12,654 | 378 | 2,041 | 1,413 | 10,613 |

| Stroke | 12,119 | 33,923 | 4,577 | 9,685 | 7,542 | 24,238 |

| CHF | 28,224 | 83,332 | 10,132 | 18,529 | 18,092 | 64,803 |

| GI bleed | 14,297 | 44,234 | 5,931 | 14,721 | 8,366 | 29,513 |

| Pneumonia | 24,304 | 100,450 | 10,817 | 26,295 | 13,487 | 74,155 |

| Year of discharge (%) | ||||||

| 1996 | 15.2 | 15.3 | 15.0 | 15.8 | 15.4 | 15.1 |

| 1997 | 14.9 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 15.1 | 14.4 |

| 1998 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 14.2 | 14.5 |

| 1999 | 14.5 | 14.4 | 14.4 | 14.3 | 14.6 | 14.4 |

| 2000 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 13.9 | 13.8 | 14.2 | 14.2 |

| 2001 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 13.7 | 13.9 |

| 2002 | 13.3 | 13.6 | 14.0 | 13.7 | 12.9 | 13.5 |

| Means test eligibility (%) | ||||||

| Eligible (low income) | 66.7 | 56.7 | 61.0 | 60.3 | 70.5 | 55.3 |

| Eligible (service-connected disability) | 29.1 | 37.5 | 33.9 | 32.8 | 25.9 | 39.3 |

| Ineligible | 4.2 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 6.9 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| College degree (%) | 21.0 | 23.9 | 21.4 | 23.4 | 20.7 | 24.1 |

| Urban (%) | 88.5 | 69.9 | 90.1 | 70.7 | 87.5 | 69.6 |

| Median household income ($) | 32,010.0 | 38,810.7 | 32,566.1 | 38,539.4 | 31,643.3 | 38,913.6 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CHF, congestive heart failure; GI bleed, gastrointestinal bleeding.

In our study population, 25.4 percent of whites and 26.9 percent of blacks had more than one hospitalization for the study conditions in 1996–2002. Among veterans who had more than one hospitalization, the mean number of hospitalizations during this period was 2.6 for whites and 2.7 for blacks (data not shown).

Relatively more black (66.7 percent) than white (56.7 percent) veterans were means test eligible due to low income, and relatively more whites (37.5 percent) than blacks (29.1 percent) were means test eligible due to service-connected disability; these differences were observed primarily among veterans over age 65. The zip code level socioeconomic characteristics indicated somewhat lower rates of college degree attainment and lower household income in zip codes in which blacks reside. Blacks were more likely than whites to live in urban settings.

The most prevalent comorbidities among both blacks and whites were hypertension, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes (Appendix A), with hypertension being relatively more prevalent among blacks and chronic pulmonary disease relatively more prevalent among whites. The proportion of blacks and whites within each age group who had none, one, or more than one comorbidity was very similar as was the mean number of comorbidities overall and among black and whites over and under age 65.

Mortality rates at 30 days from admission using VA data sources only were highest for pneumonia (12.4 percent for blacks and 13.8 percent for whites), AMI (9.7 percent for blacks and 11.4 percent for whites), and stroke (9.3 percent for blacks and 10.9 percent for whites), and lowest for hip fracture (6.3 percent for blacks and 9.2 percent for whites), CHF (5.2 percent for blacks and 8.2 percent for whites), and GI bleed (5.7 percent for blacks and 6.6 percent for whites). The corresponding race-specific mortality rates using data from both VA data sources and the NDI show similar patterns and are only slightly higher than the rates based on VA data sources alone (Table 2). For each of these six conditions, unadjusted 30-day mortality rates were significantly lower for blacks than for whites (p < 0.01 for each, Table 3; Model 1). The unadjusted odds of 30-day mortality for blacks relative to whites ranged from 0.62 for CHF to 0.88 for pneumonia.

Table 2.

Race- and Condition-Specific Unadjusted 30-Day Mortality (%), Overall and for Veterans under and over Age 65 by Source of Death Information

| Overall | Under Age 65 | Over Age 65 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black (n = 87,929) | White (n = 318,621) | Black (n = 34,953) | White (n = 87,685) | Black (n = 52,976) | White (n = 230,936) | |

| VA sources only | ||||||

| AMI | 9.7 | 11.4 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 13.0 | 15.3 |

| Hip | 6.3 | 9.2 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 7.4 | 10.4 |

| Stroke | 9.3 | 10.9 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 10.9 | 12.7 |

| CHF | 5.2 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 6.3 | 9.1 |

| GI bleed | 5.7 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 7.3 |

| Pneumonia | 12.4 | 13.8 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 16.9 | 16.0 |

| VA and NDI sources | ||||||

| AMI | 9.9 | 11.7 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 13.2 | 15.6 |

| Hip | 6.7 | 9.4 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 7.9 | 10.5 |

| Stroke | 9.4 | 11.0 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 11.0 | 12.9 |

| CHF | 5.5 | 8.5 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 6.6 | 9.5 |

| GI bleed | 5.9 | 6.8 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 6.9 | 7.5 |

| Pneumonia | 12.6 | 14.1 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 17.2 | 16.4 |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CHF, congestive heart failure; GI bleed, gastrointestinal bleeding; NDI, National Death Index.

Table 3.

Condition-Specific Estimated Odds of 30-Day Mortality for Black Veterans Relative to White Veterans

| OR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

| AMI | 0.84** | 0.90* | 0.86** | 0.85** | 0.84** |

| (N = 51,222) | (0.77,0.91) | (0.82,0.98) | (0.78,0.94) | (0.78,0.94) | (0.76,0.92) |

| Hip | 0.66** | 0.68** | 0.70** | 0.75* | 0.73** |

| (N = 14,445) | (0.54,0.80) | (0.56,0.83) | (0.57,0.87) | (0.61,0.92) | (0.59,0.90) |

| Stroke | 0.84** | 0.92* | 0.87** | 0.86** | 0.89** |

| (N = 46,042) | (0.78,0.90) | (0.86,0.99) | (0.80,0.94) | (0.80,0.93) | (0.82,0.97) |

| CHF | 0.62** | 0.69** | 0.72** | 0.72** | 0.71** |

| (N = 111,556) | (0.58,0.66) | (0.65,0.74) | (0.68,0.77) | (0.68,0.77) | (0.66,0.76) |

| GI bleed | 0.85** | 0.90** | 0.89* | 0.89* | 0.88* |

| (N = 58,531) | (0.78,0.92) | (0.83,0.97) | (0.81,0.98) | (0.81,0.97) | (0.81,0.97) |

| Pneumonia | 0.88** | 1.07** | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.93** |

| (N = 124,754) | (0.85,0.92) | (1.03,1.12) | (0.93,1.02) | (0.93,1.02) | (0.88,0.98) |

| Control variables | None | ||||

| Age | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Discharge year, comorbidities, SES | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Hospital site | Fixed effect | Random effect | |||

| NDI deaths added | Yes | ||||

p-value≤.05.

p-value≤.01.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CHF, congestive heart failure; GI bleed, gastrointestinal bleeding; NDI, National Death Index; SES, socioeconomic status; OR, odds ratio.

After an adjustment for age (Table 3; Model 2) all condition-specific odds except for pneumonia increased slightly but remained significantly lower than 1. For these five conditions, similar results were obtained when the analysis was further adjusted for time, comorbidities, SES, and means test eligibility (Table 3; Model 3). For pneumonia, the odds ratio (OR) for 30-day mortality for blacks was < 1.0 when comorbidities, SES, and means test eligibility were added as control variables and significantly < 1.0 in Model 5.

Although Models 1–3 compared blacks with whites across and within sites, Model 4 compared blacks with whites within the same site. The fact that Models 3 and 4 gave nearly identical results for all conditions suggests that the lower observed risk-adjusted mortality among blacks is not a function of blacks differentially being treated at hospitals with better outcomes. Within sites, blacks appear to have had better 30-day mortality than otherwise comparable whites.

In Model 5 the dependent variable was changed from 30-day mortality based on VA data sources to 30-day mortality including all additional deaths identified in the NDI. Also, site was treated as a random effect in Model 5. The race estimates were very similar for Models 4 and 5; the OR of 0.93 in Model 5 for blacks with pneumonia was statistically significant. The full set of parameter estimates for Model 5 is shown in Appendix B for all six conditions. The ORs of unity for the zip code level socioeconomic variables is likely due to the adjustment for site and lack of variation in these variables within site.

We observed no clear pattern of differences in the race-specific odds of 30-day mortality between those conditions for which admission tends to be nondiscretionary (AMI, hip fracture, stroke) versus those that are discretionary (CHF, GI bleed, pneumonia). For example, hip fracture and CHF had the lowest odds and stroke and pneumonia had the highest odds. Worse outcomes for blacks were not found among the discretionary conditions when compared with nondiscretionary conditions.

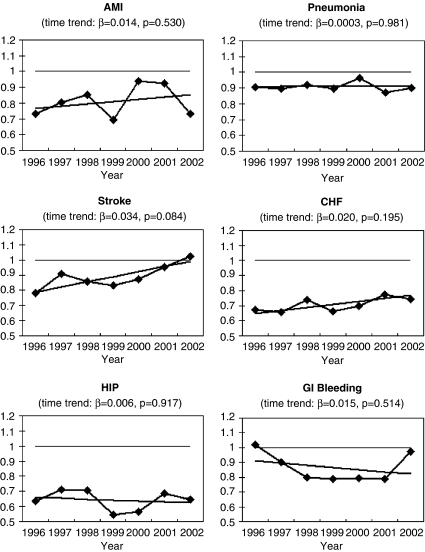

We found no consistent overall time trend in the log odds of mortality for blacks relative to whites for any of these conditions (Figure 1). We observed nonsignificant increases in the ORs with time for AMI, stroke, CHF, and pneumonia, and nonsignificant decreases with time for hip fracture and GI bleed.

Figure 1.

Time Trends of Differences in Odds of Mortality between Blacks and Whites

In Table 4 we show the unadjusted and the fully adjusted ORs for black race estimated separately for veterans who were over or under age 65. These are analogous to those for Models 1 and 5 in Table 3. Overall, veterans over age 65 comprised 69.8 percent of hospitalizations for the six study conditions. Among veterans over age 65, blacks consistently had significantly lower odds of risk-adjusted mortality than whites, with adjusted ORs ranging from a low of 0.70 for CHF (95 percent CI: 0.65–0.76) to a high of 0.90 for pneumonia (95 percent CI: 0.85–0.95). However, among veterans under the age of 65, blacks had significantly reduced risk-adjusted mortality only for CHF (OR 0.71; 95 percent CI: 0.62, 0.82). This finding does not support the hypothesis that reverse disparities are driven by differential access to the private health care system as a result of differential insurance coverage.

Table 4.

Condition-Specific Estimated Odds of 30-Day Mortality for Black Veterans Relative to White Veterans over and under Age 65

| OR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under Age 65 | Over Age 65 | |||

| Condition | Model 1 | Model 5 | Model 1 | Model 5 |

| AMI | 1.15 | 1.19 | 0.82** | 0.75** |

| (N = 31,690) | (0.97,1.36) | (0.99,1.43) | (0.75,0.90) | (0.67,0.84) |

| Hip | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.69** | 0.73** |

| (N = 12,026) | (0.30,1.34) | (0.28,1.55) | (0.56,0.85) | (0.58,0.90) |

| Stroke | 1.07 | 1.12 | 0.84** | 0.81** |

| (N = 31,780) | (0.93,1.23) | (0.95,1.32) | (0.77,0.91) | (0.74,0.89) |

| CHF | 0.65** | 0.71** | 0.68** | 0.70** |

| (N = 82,895) | (0.57,0.74) | (0.62,0.82) | (0.63,0.72) | (0.65,0.76) |

| GI bleed | 0.81** | 0.93 | 0.90* | 0.88* |

| (N = 37,879) | (0.70,0.94) | (0.78,1.10) | (0.82,1.00) | (0.79,0.99) |

| Pneumonia | 0.90* | 1.09 | 1.06* | 0.90** |

| (N = 87,642) | (0.82,0.98) | (0.98,1.21) | (1.01,1.12) | (0.85,0.95) |

| Control variables | None | None | ||

| Age | Yes | Yes | ||

| Discharge year, comorbidities, SES | Yes | Yes | ||

| Hospital site | Random effect | Random effect | ||

| NDI deaths added | Yes | Yes | ||

p-value≤.05.

p-value≤.01.

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CHF, congestive heart failure; GI bleed, gastrointestinal bleeding; NDI, National Death Index; SES, socioeconomic status; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Our study confirms that for a range of conditions treated in inpatient settings, black patients admitted to Veterans hospitals had lower 30-day mortality than whites. This finding persists after considering several possible reasons including controlling for hospital site, better ascertainment of death, evaluating conditions for which hospital admission is nondiscretionary, and changes in mortality rates over time. Finally, we find consistently better outcomes among blacks in the over-65 population, which does not support the hypothesis that these differences are driven by differential selection by race into the VA. Therefore, the finding that blacks have lower 30-day mortality post-VA hospital admission is highly robust, but still lacks a well-supported explanation.

We studied conditions for which 30-day mortality has been proposed as a Quality Indicator by AHRQ because of the face validity, precision, minimal bias, and construct validity of these measures (Geronimus, Bound, and Neidert 1996). The adjusted ORs we estimated are quite similar to those estimated in the original Jha et al. (2001) study, which found an overall odds of mortality for blacks relative to whites of 0.75. The Jha study used only data from 1995 to 1996 and examined a set of conditions (such as angina and diabetes) for which there is considerable discretion as to hospital admission. Findings on differences in mortality for blacks and whites in single-condition studies have been mixed, with some finding better mortality for blacks (Deswal et al. 2004; Kamalesh et al. 2005), some finding better mortality for whites (Mickelson, Blum, and Geraci 1997; Dominitz et al. 1998), and some finding no significant differences (Petersen et al. 2002; Ibrahim et al. 2005). The consistency of the results found in our evaluation across types of conditions and various statistical adjustments suggests that black veterans likely have better outcomes than white veterans across a number of conditions after being hospitalized in the VA health care system.

One important difference between our findings and those of others is that we found better outcomes almost exclusively among older adults. These findings on mortality among veterans older than 65 are similar to those of Barnato and colleagues, who examined outcomes for elderly Medicare patients admitted for an AMI in the mid-1990s. They too found lower mortality among blacks, which became more pronounced after adjusting for the site of hospital care (Barnato et al. 2005). While a couple of other studies using non-VA data have found lower mortality among blacks than whites (Gordon, Harper, and Rosenthal 1996; Rathore et al. 2003), most studies have found either no differences or higher mortality among blacks (Vaccarino et al. 2005; Mehta et al. 2006). While others have found that differences between sites in quality of treatment (O'Conner et al. 1999; Jencks et al. 2000) or geographic variations in treatment (Fang and Alderman 2003; Skinner et al. 2003) provide some explanation for lower levels of treatment and worse health outcomes among blacks, adjustments for VA hospital site of treatment only reinforced our findings of better outcomes for blacks, suggesting that the observed effects of our study cannot be explained by the differential location of residence or treatment of patients by race. Although there are concerns that rural veterans may have lower health-related quality of life scores than their urban counterparts (Weeks et al. 2004; Wallace et al. 2006), adjusting for hospital site also accounts for any systematic differences of this kind by focusing the comparison on within-site differences in outcomes for blacks and whites.

The reasons behind lack of a consistent relationship between race and mortality among those under age 65 are not clear. Differences in socioeconomic status are unlikely to explain our findings given that these differences were similar among the elderly as they were among veterans under age 65 within our sample. The fact that the better outcomes for blacks were not consistent in all age groups suggests that observed differences are probably not a treatment effect but more likely are driven by unmeasured factors among elderly VA users that are not present between black and white VA users under age 65. One possibility is that more sick blacks or less sick whites opt for treatment in non-VA settings once eligible for Medicare. Alternatively, given that blacks are more likely to die before 65 years of age, blacks who survive to 65 may be different than whites who survive to 65, an effect often referred to as a survivor bias (Hulley et al. 2001). It is also possible that the degree to which unmeasured characteristics correlate with treatment outcomes may differ among elderly versus younger whites and blacks who use VA services compared with their counterparts who do not use VA services. These potential explanations require further examination.

The primary limitation of our study is that we used administrative data to study mortality. However, we used a well-validated approach to risk adjustment with a high degree of ability to discriminate between patients who die and patients who live (Elixhauser et al. 1998) and build on previous studies of racial disparities in outcomes (Jha et al. 2001) that have been widely cited but which did not adjust for changes over time or the hospital site where treated. We were unable to compare outcomes among whites and blacks with other racial or ethnic groups because of insufficient power to detect 30-day mortality differences involving nonblack minorities and less reliable data on race for other races.

In summary, we found that lower mortality rates for black veterans within VA have persisted within the over age 65 population and are insensitive to a variety of different approaches to adjustment for both patient- and hospital-level predictors of mortality. For the most part, these differences are not seen in the under age 65 population for reasons that cannot be determined in our data. Future research should focus on understanding why older blacks have better outcomes after hospitalization within VA settings, the degree to which individual hospital factors explain these disparities, and the degree to which what is observed within the VA differs from measured disparities in the over and under 65 age populations in non-VA settings.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Volpp is a VA HSR&D Career Development Award recipient. We thank VA HSR&D IIR 03.070.1 for funding support. The funding agency had no role in reviewing or approving this manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The following supplementary material for this article is available:

Prevalence of Comorbidities (%) across Hospitalizations for All Six Conditions, Overall and for Veterans under and over Age 65.

Estimated Odds Ratios (ORs), 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs), and Associated Variance Parameters for Model 5 (Random-Effects Model Including NDI Data), by Condition.

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00688.x (this link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Blackwell Publishing is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health: Pathways and Policies. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2002;21(2):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Quality Indicators—Guide to Inpatient Quality Indicators: Quality of Care in Hospitals—Volume, Mortality, and Utilization. AHRQ Pub. No. 02-R 0204. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-Level Racial Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment and Outcomes. Medical Care. 2005;43(4):308–19. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu J, Clancy C. Racial Disparity, Primary Care, and Specialty Referral. Health Services Research. 2001;36(6):64–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle DM, Leake BD, Shapiro MF. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Cardiovascular Procedures: Associations with Type of Health Insurance. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(2):263–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, Hynes DM. A Primer and Review of Major U.S. Mortality Databases. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12(7):462–8. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Souchek J, Ashton CM, Wray NP. Impact of Race on Health Care Utilization and Outcomes in Veterans with Congestive Heart Failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004;43(5):778–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominitz JA, Samsa GP, Landsman P, Provenzale D. Race, Treatment, and Survival among Colorectal Carcinoma Patients in an Equal-Access Medical System. Cancer. 1998;82(12):2312–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980615)82:12<2312::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data. Medical Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Alderman MH. Is Geography Destiny for Patients in New York with Myocardial Infarction? American Journal of Medicine. 2003;115(6):448–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00446-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P. Impact of Patient Socioeconomic Status on Physician Profiles: A Comparison of Census-Derived and Individual Measures. Medical Care. 2001;39(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SG, Weber LL, Goldberg J. Mortality Ascertainment in the Veteran Population: Alternatives to the National Death Index. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;141(3):242–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman VL, Durazo-Arvizu R, Arozullah AM, Keys LC. Determinants of Mortality following a Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer in the Veterans Affairs and Private Sector Health Care Systems. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(10):1706–12. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Bound J. Use of Census-Based Aggregate Variables to Proxy for Socioeconomic Group: Evidence from National Samples. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148(5):475–86. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, Neidert L. On the Validity of Using Census Geocode Characteristics to Proxy Individual Socioeconomic Characteristics. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91(434):529–37. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Hillemeier MM, Burns PB. Excess Mortality among African Americans and Whites in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(21):1552–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman DP, Smith JP. Can Patient Self-Management Help Explain the SES Health Gradient? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(16):10929–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162086599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H. Multilevel Statistical Models. New York/London: Wiley/Edward Arnold; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein LB, Matchar DB, Hoff-Lidquist J, Sams GP, Horner RP. Veterans Administration Acute Stroke (VASt) Study: Lack of Race/Ethnic-Based Differences in Utilization of Stroke-Related Procedures or Services. Stroke. 2003;34(4):999–1004. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000063364.88309.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon HS, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE. Racial Variation in Predicted and Observed In-Hospital Death: A Regional Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(20):1639–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermos JA, Page WF, Jha AK, Shlipak MG, Browner WS. Health Outcomes for Black and White Patients in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(14):1837–8. [Google Scholar]

- Horner RD, Oddone EZ, Stechuchak KM, Grambow SC, Gray J, Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Daley J. Racial Variations in Postoperative Outcomes of Carotid Endarterectomy: Evidence from the Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Medical Care. 2002;40(1 suppl):I35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner SW, Grady D, Hearst N, Newman TB. Designing Clinical Research: An Epidemiologic Approach. 2. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim SA, Stone RA, Han X, Cohen P, Fine MF, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Kwoh CK. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Surgical Outcomes in Veterans following Knee or Hip Arthroplasty. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52(10):3143–51. doi: 10.1002/art.21304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, Fleming B, Houck PM, Kussmaul AE, Nilasena DS, Ordin DL, Arday DR. Quality of Medical Care Delivered to Medicare Beneficiaries: A Profile at State and National Levels. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(13):1670–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Perlin JB, Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Effect of the Transformation of the Veterans Affairs Health Care System on the Quality of Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(22):2218–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha AK, Shlipak MG, Hosmer W, Frances CD, Browner WS. Racial Differences in Mortality among Men Hospitalized in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(3):297–303. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamalesh M, Subramanian U, Ariana A, Sawada S, Peterson E. Diabetes Status and Racial Difference in Post-Myocardial Infarction Mortality. American Heart Journal. 2005;150(5):912–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR, Chang BH, Hendricks A, Kazis LE. Agreement between Administrative Data and Patients' Self-Reports of Race/Ethnicity. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(10):1734–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J, Kaplan G. Socioeconomic Position. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mark DH. Race and the Limits of Administrative Data. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(3):337–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. The Influence of Income on Health: Views of an Epidemiologist. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2002;21(2):31–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan TP, Hennen J, Randford MJ, Petrillo MK, Elstein P, Ballard DJ. Process and Outcomes of Care for Acute Myocardial Infarction among Medicare Beneficiaries in Connecticut: A Quality Improvement Demonstration Project. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1995;122(12):928–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta RH, Marks D, Califf RM, Sohn S, Peiper KS, Van de Werf F, Peterson ED, Ohman EM, White HD, Topol EJ, Granger CB. Differences in Clinical Features and Outcomes in African Americans and Whites with Myocardial Infarction. American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(1):70.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson JK, Blum CM, Geraci JM. Acute Myocardial Infarction: Clinical Characteristics, Management and Outcome in a Metropolitan Veterans Affairs Medical Center Teaching Hospital. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;29(5):915–25. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MG, Miller LS, Fireman B, Black SB. Variation in Practice for Discretionary Admissions: Impact on Estimates of Quality of Hospital Care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(19):493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskos CC, Butler JS. All That We Can Be: Black Leadership and Racial Integration the Army Way. New York: Perseus Books Groups; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O'Conner GT, Quinton HB, Traven ND, Ramunno LD, Dodds TA, Marciniak TA, Wennberg JE. Geographic Variation in the Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction: The Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(7):627–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G, Hadden WC, Kozak LJ, Fisher GF. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations: Inequalities in Rates between US Socioeconomic Groups. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(5):811–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JV, Warwick DJ, Case CP, Bannister GC. Death after Proximal Femoral Fracture—An Autopsy Study. Injury. 1995;26(4):237–40. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)90008-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen LA, Wright SM, Peterson ED, Daley J. Impact of Race on Cardiac Care and Outcomes in Veterans with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Medical Care. 2002;40(1 suppl):I89–96. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore SS, Foody JM, Wang Y, Smith GL, Herrin J, Masoudi FA, Wolfe P, Havranek EP, Ordin DL, Krumholz HM. Race, Quality of Care, and Outcomes of Elderly Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(19):2517–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Variation in Outcome after Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. The National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Lancet. 1995;346(8971):346–50. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano PS, Luft HS, Remy L. Second Report of the California Hospital Outcomes Project on Acute Myocardial Infarction. Vol. II: Technical Appendix. Sacramento, CA: California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Selim AJ, Fincke G, Berlowitz DR, Cong Z, Miller DR, Ren XS, Qian S, Rogers W, Lee A, Rosen AK, Selim BJ, Kazis LE. No Racial Difference in Mortality Found among Veterans Health Administration Out-Patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57(5):539–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Adams A, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, Ayanian JZ. The Effect of Quality Improvement on Racial Disparities in Diabetes Care. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(6):675–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen JJ, Wan TTH, Perlin JB. An Exploration of the Complex Relationship of Socioecological Factors in the Treatment and Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Disadvantaged Populations. Health Services Research. 2001;36(4):711–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner J, Weinstein JN, Sporer SM, Wennberg JE. Racial, Ethnic, and Geographic Disparities in Rates of Knee Arthroplasty among Medicare Patients. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(14):1350–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern DA, Quan H, Ghali WA. Comparison of the Elixhauser and Charlson/Deyo Methods of Comorbidity Measurement in Administrative Data. Medical Care. 2004;42(4):355–60. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118861.56848.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenborg GJ, Wagner DP, Connors AF. Comparison of the Performance of Two Comorbidity Measures, with and without Information from Prior Hospitalizations. Medical Care. 2001;39(7):727–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200107000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. FY 2003 HUD Income Limits Briefing Material. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vaccarino V, Rathore SS, Wenger NK, Frederick PD, Abramson JL, Barron HV, Manhapra A, Mallik S, Krumholz HM. Sex and Racial Differences in the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction, 1994 through 2002. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(7):671–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa032214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center. VIReC Research User Guide: FY2002 VHA Medical SAS Inpatient Datasets. Hines, IL: Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace AE, Weeks WB, Wang S, Lee AR, Kazis LW. Rural and Urban Disparities in Health-Related Quality of Life among Veterans with Psychiatric Disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(6):851–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks WB, Kazis LE, Shen U, Cong Z, Ren XS, Miller D, Lee A, Perlin JB. Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life in Rural and Urban Veterans. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(10):1762–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Prevalence of Comorbidities (%) across Hospitalizations for All Six Conditions, Overall and for Veterans under and over Age 65.

Estimated Odds Ratios (ORs), 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs), and Associated Variance Parameters for Model 5 (Random-Effects Model Including NDI Data), by Condition.