Abstract

Objective

In a recent report, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) defines a health service disparity between population groups to be the difference in treatment or access not justified by the differences in health status or preferences of the groups. This paper proposes an implementation of this definition, and applies it to disparities in outpatient mental health care.

Data Sources

Health Care for Communities (HCC) reinterviewed 9,585 respondents from the Community Tracking Study in 1997–1998, oversampling individuals with psychological distress, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, or mental health treatment. The HCC is designed to make national estimates of service use.

Study Design

Expenditures are modeled using generalized linear models with a log link for quantity and a probit model for any utilization. We adjust for group differences in health status by transforming the entire distribution of health status for minority populations to approximate the white distribution. We compare disparities according to the IOM definition to other methods commonly used to assess health services disparities.

Principal Findings

Our method finds significant service disparities between whites and both blacks and Latinos. Estimated disparities from this method exceed those for competing approaches, because of the inclusion of effects of mediating factors (such as income) in the IOM approach.

Conclusions

A rigorous definition of disparities is needed to monitor progress against disparities and to compare their magnitude across studies. With such a definition, disparities can be estimated by adjusting for group differences in models for expenditures and access to mental health services.

Keywords: Disparities, mental health, statistical adjustment for health status

In health care, the term “disparities” refers to the unequal treatment of patients on the basis of race or ethnicity, and sometimes on the basis of gender or other patient characteristics. A consensus has emerged that eliminating disparities should be a major goal of health policy, but the empirical and policy literature fails to agree on what a “disparity” is, and how it should be measured. Empirical research often estimates coefficients of race/ethnicity variables without relating these coefficients to an explicit definition of disparity.

The recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (IOM 2002), defines a disparity as a difference in treatment provided to members of different racial (or ethnic) groups that is not justified by the underlying health conditions or treatment preferences of patients.1 This definition recognizes the role of socioeconomic differences associated with race/ethnicity as mediators of disparities. To implement the IOM definition, we developed a new method for adjusting for health status that can be used with any model, including nonlinear models that quantify use of health care. We compare the magnitude of disparities estimated by this method to a residual race/ethnicity effect that is often interpreted as meaning a disparity.2

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: DIFFERENCES, DISPARITIES, AND DISCRIMINATION

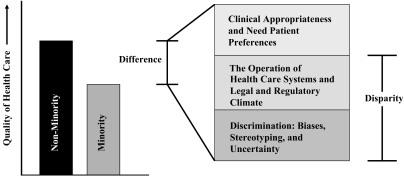

Unequal Treatment distinguishes differences, disparities, and discrimination (Figure 1). A difference in health care use is the simple unadjusted difference in means or rates between racial/ethnic groups such as non-Hispanic whites and Latinos, and might be explained by several sets of factors. Health status differences between the groups may explain some of the difference in health care use. Latino patients may have fewer health problems, perhaps because they are younger, and require fewer visits. Differences in use because of health status are not considered part of a disparity, nor are those because of different preferences for health care treatment.3

Figure 1. Differences, Disparities, and Discrimination: Populations with Equal Access to Health Care.

The remainder of the identified difference is a disparity. “Operation of the Health Care System” subsumes a variety of systematic sources of disparities, including provider practice patterns, uninsurance or membership in more restrictive health plans, and health care factors differentially affecting racial/ethnic groups. Minorities have lower incomes on average, and if this inhibits health care use, the resulting differences contribute to disparities. Discrimination, when a provider supplies less to a member of a racial/ethnic minority than to an otherwise similar white patient, is also part of a disparity.4

The distinctive feature of the IOM definition of disparities is that it includes all racial/ethnic differences in use mediated through factors other than health status and preferences. For example, if whites have higher income on average than minorities, the resulting differences in care are components of disparities. The IOM framework does not assume that race/ethnicity is the cause of lower income among minorities. Its application only depends on the descriptive observation that minorities are more likely to have low incomes (and low income leads to lower health care use). An accounting of disparities mediated through other variables is straightforward in a simple linear model using estimated coefficients and group means for regressors. This example illustrates the importance of the interpretation of socioeconomic status (SES) in health care disparities research. Poverty disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minorities, reducing use of services controlling for medical need.5 Hence, controlling for insurance or SES may diminish or eliminate the estimated independent effect of race/ethnicity.

BACKGROUND: DISPARITIES IN MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES USE

We choose mental health care to illustrate the application of the IOM framework for three main reasons. First, mental illnesses are highly prevalent, and can be reliably detected in large community-based surveys using lay interviewer assessments (Canino et al. 1999; Kessler et al. 2000; Aalto-Setala et al. 2002). Second, social factors play a large role in both illness and the way mental illnesses are treated, making mental health care a good setting to explore their role as mediators of service disparities in the IOM definition. Third, there is strong evidence of disparities in mental health services. As documented in “Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General” (DHHS 1999) and its supplement, “Mental Health, Culture, Race and Ethnicity” (DHHS 2001), racial and ethnic minorities have less access to mental health services than do whites, are less likely to receive needed care, and are more likely to receive poor quality care when treated. Using data from a national survey (the same analyzed in this paper), Wells, Klap, and Sherbourne (2001) found that among adults with diagnosis-based need for mental health or substance abuse care, 37.6 percent of whites, but only 22.4 percent of Latinos and 25.0 percent of African Americans, were receiving treatment. Minorities in the United States are more likely than whites to delay or fail to seek mental health treatment (Sussman, Robins, and Earls 1987; Kessler et al. 1996; Zhang, Snowden, and Sue 1998). After entering care, minority patients are less likely than whites to receive the best available treatments for depression and anxiety (Wang, Berglund, and Kessler 2000; Young et al. 2001). African Americans are more likely than whites to terminate treatment prematurely (Sue, Zane, and Young 1994).6

DATA

The Health Care for Communities Survey (HCC), was designed to collect information about alcohol, drug abuse and mental health (ADM) care, insurance, access, utilization, cost and quality of ADM care, other personal characteristics, and health outcomes including functioning and satisfaction. The project is an extension of the Community Tracking Study (CTS), a longitudinal health care survey of households, insurers, physicians, and employers. In 1997–1998, the HCC reinterviewed 9,585 respondents from the CTS (response rate of 64 percent), oversampling individuals with a history of psychological distress, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, or mental health treatment (Sturm et al. 1999). The HCC sample was designed to make national as well as some site-specific estimates of need and service use.

Defining the Quantity Index

The HCC data show services used, not dollar expenditures. We created a “quantity index” by weighting each of the outpatient mental health services reported by the HCC respondent in the 12-month period by the national average price paid for this service, obtained from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS).7 Our objective in creating this summary of utilization is to compare the total value of services used by different individuals, not to estimate actual costs to patients or other payers.

Outpatient care expenditures are calculated from the numbers of times the respondent received care in an emergency room for ADM problems, saw a substance abuse specialist for alcohol or drug problems, attended an alcohol or drug program, saw a medical provider during which the provider talked about ADM problems, and saw a mental health provider for ADM problems. The total expenditure variable reflects utilization over the 12 months before the survey interview. Visits to mental health specialists, primary care practitioners for mental health care and emergency room visits for psychiatric conditions are priced at $77, $69, and $473, respectively, using averages calculated from the MEPS. Pharmaceutical drug expenditures for an individual are the product of the “total number of psychotropic drugs taken at least several times a week for a month or more in the past 12 months” and average drug expenditure per drug per year of $45, also calculated from MEPS.

Health and Mental Health Status

Respondents reported their medical conditions at the time of the interview, including asthma, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, physical disability, trouble breathing, cancer, neurological impairment, stroke, angina, back problems, ulcer, liver diagnosis, migraine, bladder infection, gynecological problems, and chronic pain. Zero–one indicators were entered for each of these conditions. We considered using the number of chronic conditions rather than the individual conditions, but rejected this specification because in preliminary analysis, different conditions had different effects on expenditures. Mental health problems were assessed based on responses to questions from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Individuals were identified as likely to have a mental or substance abuse disorder based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Version III-R. Conditions assessed were generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), major depressive disorder (MDD), dysthymia, mania, psychosis, panic disorder, problems with alcohol, and problems with drugs.8 Also included were three summary physical and mental health scales, the PCS-12, MCS-12, and the MHI-5.

Preferences

There are few measures of preferences in the HCC data, and none specific to preferences about the receipt of mental health treatment. Some sociodemographic factors are likely to be associated with treatment preferences. With our data, however, it is impossible to distinguish between SES effects operating through preferences and the more direct effects of economic resources on ability to obtain care. Furthermore, even if we had measures of treatment preferences, ethnic differences in such measures might still reflect the effects of expectations based in prior individual or group encounters with poor quality or discrimination in health care (Cooper-Patrick et al. 1997). The theoretical construct most relevant to identifying unfair differences in access or use of treatments by ethnic status is the hypothetical of a fully informed preference for treatment (IOM 2002), which minimizes the problem of underlying differences in experience or knowledge. There is no gold standard measure for such preferences. We do not interpret any variables in our empirical model as measuring preferences, but acknowledge that the lack of such measures limits our implementation of the IOM definition.

Race and Ethnicity

Census categories were used for questions about race and ethnicity. Individuals of any race claiming to be of Hispanic origin (including Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or other Spanish background) are identified as Hispanic in our study. Other respondents were classified as black, white, or “other” by responses to the question about race. The HCC identifies Asian Americans, but this group was too small to study separately and they are grouped with “others” in this study. We use data from all racial/ethnic categories to fit the best empirical model, but only report disparities for blacks and Hispanics relative to whites. We do not estimate disparities for the heterogeneous and therefore uninterpretable “other” group.

Other Covariates

Demographic and SES covariates were total annual income, age, gender, marital status, education level, metropolitan/rural area, nativity, and language of interview (English or Spanish). Health insurance coverage was measured in three dimensions. First, we distinguish insurance status as uninsured, employer-sponsored insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and other public programs. Second, a managed care indicator was based on whether the respondent had to sign up with a specific provider group for routine care, needed a referral for specialist care, had to choose from a list of eligible doctors, or whether the plan was an HMO. Third, coverage for mental health care was measured separately, and if present, a separate indicator measured whether or not an approval or referral was required before seeing a specialist for mental health care.

Geography Indicators

We defined indicator variables for each of the 60 “high-intensity” and “low-intensity” sites in the HCC sample, and split the unclustered, nationally representative supplemental sample by ten additional variables indicating in which of the 10 HHS regions of the country the respondent was located. Interpretation of geographic effects in access and expenditure models is problematic for interpretation of disparities, and we consider alternative treatments of these variables in our Results section.

METHODS

Questions about differences (typically between a target group that we refer to as “minorities” and a reference group that we refer to as “whites”) concern observed quantities. Comparing sample means for utilization tells the difference in use between whites and minorities. Questions about disparities, on the other hand, concern counterfactuals. To apply the IOM definition of disparity, we pose the counterfactual in the following way: “how much more (or less) treatment would minorities receive than whites if they had the same health status as whites?”

The implementation of this counterfactual is nontrivial because it concerns quantities that we cannot observe directly, and does not correspond directly to the “race/ethnicity” coefficients in the model. To compare utilization for whites and minorities of the same health status, we would have to take into account not only the race/ethnicity coefficient and any interactions of race/ethnicity with other variables, but also coefficients of other nonhealth-status variables that have different distributions for whites and minorities (such as income). If the model is linear then the desired mean predictions can be obtained simply by substituting mean values for each group into the prediction equations. Conversely, with nonlinear models, which often better describe expenditures and utilization, calculation of the magnitude of the disparity generally requires simulation of predictions even with the simplest of specifications of the race/ethnicity effect (a single additive effect). Joint distributions of the predictors, as well as marginal means, are required. However, we can use models to generate the counterfactual predictions we need. Thus, our general plan involves the following steps: (1) fit a model that adequately describes relationships between utilization and health status, SES, race, and other characteristics, (2) transform the distributions of health status for the minority groups to be the same as that of whites, while leaving other variables unchanged, (3) calculate predictions under the models for minority groups with transformed health status, and (4) aggregate predictions by group to estimate disparities.9

Statistical Methods

We use a generalized linear model (GLM) with quasi-likelihoods (McCullagh and Nelder 1989), a form of nonlinear least squares modeling. In these models, expected expenditures E(y∣x) are modeled directly as μ(x′β) where μ is the link between the observed raw scale of expenditure, y, and the linear predictor x′β, where y represents expenditures and x are the predictors. The conditional variance of y is a power function of expected expenditures. Thus

| (1) |

Our predictors consist of a vector of SES variables such as income and education, a vector of health status variables (HS), and indicators of race/ethnic group. μ is a transformation such as antilogarithm or square and λ is typically 0, 1, 2 or some intermediate value. Zero values of expenditures are not problematic for this modeling approach, as the transformation is applied to the expected value, not the observed values. Advantages of the alternative approaches are discussed by Manning and Mullahy (2001) and Buntin and Zaslavsky (2004). An important advantage of the GLM is that the predicted mean is obtained directly, without retransformation of residuals. Thus, the predictions are more robust and the coefficients more interpretable compared with the log-transformed OLS models, whose predictions are sensitive to heteroscedasticity and nonnormality of the residuals.

To determine the link and variance functions for our GLM model, we use diagnostics suggested by Buntin and Zaslavsky (2004), including examining the distribution of the data to be modeled, choosing a transformation of the positive part of the expenditure data that most closely approximates a normal distribution, and conducting a Park test to estimate the relationship between the mean and the variance (Park 1966).

In addition to the GLM, we also use a probit model to determine the probability of having any mental health care expenditure. This models the presence of nonzero expenditures as

| (2) |

where Φ is the normal cumulative distribution function and x′ is the same set of predictors as in (1). The GLM and the probit are commonly used complex nonlinear models that can be used to illustrate our methods to study disparities.

Observations are weighted to be nationally representative. Weights (http://www.hsrcenter.ucla.edu/research/hcc/technical.pdf) consist of a sample selection weight, a nonresponse weight, an HCC frame weight that adjusts for differential selection of CTS respondents into the HCC, and a weight for the exclusion of nontelephone households. Variances were estimated using Stata software, accounting for stratification, clustering, and unequal sampling probabilities.10

Computing the Disparity

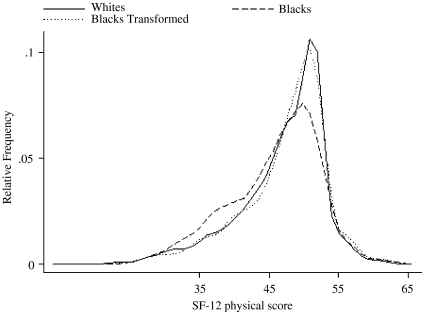

To implement the IOM definition of disparity, we adjust for health status in an innovative fashion, by transforming the minority distribution of continuous health status variables to match the white distribution, while preserving the rank order within the minority group. Our approach generalizes the mean-replacement method that is used with linear models. With nonlinearity, the whole distribution of health status matters, and we transform the whole distribution, not just the mean.11 For each health status variable, we sorted the data for each race (white, black, Latino) by health status variable to be transformed. Next, we replaced the value for each minority individual with that for the equivalently ranked white individual. As there are approximately seven times as many whites as blacks, the value for the #1 ranked black were replaced by that for #4 ranked white, for the #2 ranked black by the #11 ranked white, etc. This method minimizes the magnitudes of adjustments of minority observations.12 We transform dichotomous health status variables by equating proportions of positive responses across the groups. Responses among the minority group are changed at random to make the final proportion of positive responses in the minority distribution equivalent to the white distribution.

Figure 2 illustrates the transformation for a continuous measure of health status. Blacks (dashed line) have a slightly lower mean PCS-12 score than do whites (solid line), and a more dispersed distribution. Transformation of the black distribution using our rank-and-replace method (dotted line) moves it to the right, closely approximating the white distribution.

Figure 2.

Physical Component Score of the SF-12 Comparing Whites, Blacks, and Transformed Blacks.

The transformed data are used for prediction. The models (estimated from the original, untransformed data) are applied to the transformed values of health status for minority groups to predict the mean health expenditure for each of the groups. Predicted mean expenditures and rates are compared with those for whites to answer the counterfactual question posed above: “how much more (or less) treatment would minorities receive than whites if they had the same health status as whites?”

Interpreting Effects of Covariates for Computation of Disparities

The IOM definition of disparities requires adjusting for health status (and preferences, if good measures exist) but not other factors explaining differences in service use or expenditures. The following sets of variables were regarded as measuring health status: age, gender, marital status, physical health conditions, health and mental health rating scales, activity limitations and mental and substance abuse disorders.13 We considered alternative treatments of the forms of insurance coverage listed in Table 1. Insurance reflects a combination of SES (ability to pay for insurance and/or to obtain either employment that provides insurance or publicly funded insurance), health care needs, and preferences (affecting the decision to seek insurance given needs and resources). Our empirical findings warned us against naively treating health insurance coverage simply as a measure of ability to pay for care. Compared with employer-provided coverage (which we anticipated to be the most generous form of insurance), other types of insurance had positive estimated coefficients in the models of expenditures and use. This suggested that the type of insurance might mediate differences in the health care needs of people enrolled in the various plans more than the effects of coverage differences across plans. Individuals who use neutral health care might be more aware of the terms of their coverage, and this could bias the estimated effect in unknown ways. With more comprehensive measures of health status, it might be possible to isolate the incentive effect from the selection effect of insurance, and treat each appropriately for computing disparities. Lacking these, we alternatively compute disparities putting type of insurance coverage in the health status category (for which we adjust) and in the SES category (for which we do not adjust) when comparing across groups. For all comparisons, direct measures of mental health insurance coverage are treated like an SES variable, and therefore a potential mediator of disparities. All other SES variables were regarded as potential mediators for disparities.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Race for the Health Care for Communities (HCC) Sample, 1997–1998 (N = 9,585)†

| Characteristic | White | Black | Other | Hispanic | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 7,299) | (n = 1,103) | (n = 566) | (n = 617) | (n = 9,585) | |

| Outpatient expenditure | |||||

| % >0 expenditure | 21.84 | 16.57** | 14.06** | 17.05** | 20.28 |

| All respondents | $ 91.90 | $ 70.48 | $ 50.71** | $ 100.10 | $ 87.63 |

| Respondents >$0 | $ 420.74 | $ 425.21 | $ 360.74 | $ 586.99 | $ 432.18 |

| Demographic | |||||

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Female | 52.9 | 53.2 | 49.6 | 50.5 | 47.5 |

| Male | 47.1 | 46.8 | 50.4 | 49.5 | 52.5 |

| Nativity (%) | |||||

| Foreign-born | 3.6 | 2.2* | 27.8** | 52.4** | 9.6 |

| U.S.-born | 96.4 | 97.8 | 72.2 | 47.7 | 90.4 |

| Age (%) | |||||

| 18–24 | 8.0 | 10.4** | 7.4* | 14.7** | 8.9 |

| 25–34 | 17.2 | 22.4 | 18.0 | 22.5 | 18.4 |

| 35–44 | 22.1 | 24.4 | 16.4 | 31.0 | 22.9 |

| 45–54 | 17.3 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 15.3 | 17.3 |

| 55–64 | 12.7 | 11.2 | 14.6 | 7.2 | 12.1 |

| 65–74 | 14.2 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 5.2 | 12.5 |

| 75+ | 8.5 | 4.4 | 13.8 | 4.0 | 7.9 |

| Mean age | 48.2 | 43.6** | 50.4 | 40.4** | 47.1 |

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Married | 68.2 | 44.3** | 58.2** | 63.1 | 64.2 |

| Single | 31.8 | 55.7 | 41.8 | 36.9 | 35.8 |

| Language of interview (%) | |||||

| English | 99.9 | 99.7** | 99.3** | 66.8** | 96.7 |

| Spanish | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 33.2 | 3.3 |

| Socioeconomic | |||||

| Income mean | $ 49,442.85 | $ 34,936.12** | $ 42,076.42** | $ 35,120.74** | $ 45,873.33 |

| Education (%) | |||||

| < HS | 10.8 | 22.4** | 15.7 | 34.6** | 14.8 |

| HS grad | 34.1 | 35.7 | 32.5 | 30.0 | 33.8 |

| Some college | 29.5 | 26.1 | 24.0 | 24.2 | 28.3 |

| College graduate | 25.6 | 15.8 | 27.8 | 11.2 | 23.2 |

| Geography | |||||

| Population size (%) | |||||

| Population >200K | 68.5 | 72.0** | 75.6* | 90.3** | 71.5 |

| Population < 200K | 7.5 | 9.7 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 7.1 |

| Nonmetro | 24.0 | 18.3 | 19.5 | 7.6 | 21.5 |

| Health insurance | |||||

| Insurance coverage (%) | |||||

| Employer-based | 58.0 | 51.1** | 51.9 | 44.4** | 55.5 |

| Uninsured | 9.1 | 16.9 | 12.0 | 31.0 | 12.3 |

| Medicare | 21.6 | 14.4 | 23.8 | 8.5 | 19.6 |

| Medicaid | 1.8 | 9.7 | 2.8 | 7.1 | 3.3 |

| Other insurance | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.6 |

| Self-insured | 6.2 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| Military/other public | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Managed care (%) | |||||

| Yes | 63.5 | 64.9 | 61.8 | 57.5* | 37.0 |

| No | 36.5 | 35.1 | 38.3 | 42.5 | 63.0 |

| Mental health coverage (%) | |||||

| Yes | 87.3 | 77.3** | 85.4 | 80.6* | 14.6 |

| No | 12.7 | 22.7 | 14.6 | 19.4 | 85.4 |

| Needs referral or approval to see mental health specialist (%) | |||||

| Yes | 31.5 | 28.6 | 38.0 | 19.3* | 30.7 |

| No | 68.5 | 71.4 | 62.0 | 80.7 | 69.4 |

| Health status | |||||

| Physical health condition (%) | |||||

| Asthma | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 5.6 | 7.2 |

| Diabetes | 6.1 | 13.0** | 8.3 | 6.6 | 7.1 |

| Hypertension | 18.7 | 31.1** | 19.8 | 15.7 | 20.0 |

| Arthritis | 27.4 | 24.6 | 32.2 | 19.9** | 26.6 |

| Physical disability | 6.4 | 4.7 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 6.3 |

| Trouble breathing | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 3.0* | 5.1 |

| Cancer | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 2.2 |

| Neurological disorder | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

| Stroke | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Angina | 5.0 | 3.2* | 1.0** | 3.6 | 5.0 |

| Back problem | 18.1 | 15.3 | 17.5 | 17.2 | 17.7 |

| Ulcer | 7.4 | 5.4* | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.4 |

| Liver diagnosis | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Migraine | 11.1 | 13.0 | 14.5 | 14.3* | 11.8 |

| Bladder infection | 5.1 | 5.3 | 3.8 | 5.7 | 5.1 |

| Gynecological problem | 4.1 | 7.1** | 2.8 | 7.0** | 4.7 |

| Chronic pain | 8.9 | 6.0* | 6.3 | 8.5 | 8.4 |

| Health scales (0–100) | |||||

| PCS12 | 46.9 | 45.7** | 46.2 | 46.1* | 46.7 |

| MCS12 | 45.7 | 45.1* | 45.7 | 45.4 | 45.6 |

| MHI5 | 81.0 | 77.5** | 81.2 | 79.5 | 80.4 |

| Activity limitation (%) | |||||

| 0 days | 74.3 | 72.0 | 74.2 | 79.7 | 74.6 |

| 1–2 days | 10.9 | 9.9 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 10.7 |

| 3–14 days | 11.4 | 13.3 | 11.6 | 9.0 | 11.4 |

| 15–28 days | 3.4 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 3.4 |

| Mental health status (%) | |||||

| GAD | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 3.7 |

| MDD | 9.1 | 11.9* | 6.1* | 7.8 | 9.1 |

| Dysthymia | 3.7 | 7.3** | 3.1 | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| Manic | 1.3 | 3.9** | 3.0** | 5.4** | 2.1 |

| Psychosis | 0.9 | 2.9** | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Panic disorder | 3.4 | 4.8* | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.5 |

| Problem alcohol | 6.4 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 8.1 | 6.4 |

| Problem drug | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

Significantly different from whites at p <.05 level.

Significantly different from whites at p <.01 level.

Means, proportions, and standard errors are nationally representative and take into account HCC sample selection weights.

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Geography is an interesting case conceptually and empirically in estimation of disparities (Chandra and Skinner 2003). Arguments can be made both for and against adjusting for geography. If a group is concentrated in areas that are persistently medically underserved then it might be appropriate to regard the effect of this geographical concentration as part of the disparity, especially as geographical differences might be consequences of slavery and of historical (and perhaps current) patterns of housing and employment discrimination. From this standpoint, we would estimate geographical effects and include racial/ethnic differences mediated through geography as part of disparities. On the other hand, the hypothetical that all areas are made equal (or that members of each group are moved about to have the same geographic distribution) might be less relevant if we are focusing on actions that might be taken to improve the distribution of health care within each area. In that case, geographic location is a nonmodifiable factor that might be better treated like a preference. Given these conflicting arguments, and to better understand the role of geographic factors in disparities, we have chosen to implement both treatments of geographic effects—treating it like a preference and adjusting for it before we compare minorities and whites, and alternatively treating it like SES and not adjusting.

Comparison with Differences and Other Disparity Measures

We compare the “IOM disparity” measure to other contrasts between racial/ethnic groups through a sequence of intergroup comparisons, successively adjusting for additional sets of variables. We begin with the simple difference between the groups adjusting for no factor.14 We then calculate several disparity measures using the IOM framework: (1) adjusted only for age, sex and health status variables, (2) adjusted additionally for type of health insurance (3) adjusted additionally for geography by setting each area indicator to its mean (the fraction of the population in that site) to remove differences because of the disproportionate distribution of race/ethnicity across areas.

Finally, we compute a disparity based on the estimated effect of the race/ethnicity variable only, thus effectively adjusting for all variables other than race/ethnicity (including SES variables). We recomputed predictions for the white observations, setting the race/ethnicity variable equal to black and Hispanic values, thereby incorporating the main effect of race/ethnicity as well as the interactions. We then computed means for the white sample with altered race values and figured disparities. We call this estimate the “residual direct effect” (RDE) of race/ethnicity because it represents the unmediated effect of race/ethnicity and its interactions after adjusting for all other measured covariates.15

RESULTS

Table 1 describes outpatient expenditures, demographic characteristics, SES, geography, health insurance, and health status by ethnicity/race. Population groups differ both in health status and in potential mediators of disparities. Compared with whites, blacks have significantly lower likelihood of any health care expenditure. Blacks are younger, less likely to be married, and have lower income and less education than whites. Blacks are less likely to have mental health coverage in health insurance. In general, blacks are less healthy than whites, with more chronic conditions and lower scores on all health status scales (PCS-12, MHI-5, and MCS-12). Finally, blacks were more likely than whites to have MDD, dysthymia, mania, psychosis, and panic disorder.

Hispanics are also less likely than whites to have any health care expenditure. They are younger, more likely to be foreign-born, and have lower income and education than whites. They are more likely to be uninsured or covered by Medicaid. Hispanics have less mental health coverage and lower rates of being covered by managed care. Health status differences between Hispanics and whites are relatively small.

Table 2 displays our fitted regression models. The first pair of columns describes the GLM for expenditures with the log link function and Poisson variance distribution. Indicator variables for ethnicity/race, gender, nativity, and age (the variables appearing in interactions) were centered on the mean so that main effects coefficients are interpretable as the effect for the category with other variables fixed at their average values. For example, the coefficient of −0.80 for black means that the health care expenditure of a hypothetical black individual with average age, gender, and foreign-born status was e−0.80 or 45 percent of the health care expenditure of a white individual with the same age, gender, foreign-born status, and other characteristics. Blacks had significantly less health care expenditures, controlling for demographic, SES, geography, health insurance, and health status factors. Gender interactions in this model were only notable for Hispanics, where there was a significant negative effect on expenditures of being both Hispanic and female. Higher education positively influenced expenditures. Individuals in Medicare and Medicaid programs had significantly more spending than those in employer-provided health insurance. The presence of mental health coverage had a positive estimated effect, but not significantly so. Mental health conditions had positive effects on outpatient mental health expenditures.

Table 2.

Generalized Linear Model (Log Link and Poisson Variance Distribution) Regression Coefficients of Outpatient Expenditures and Probit Analysis Regression Coefficients of Any Outpatient Expenditure (N = 9,328)†,‡ (70 Geographic Site Indicators Were in Model but Are Not Shown)§

| Outpatient Expenditures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLM | Any Outpatient Expenditure | |||

| Characteristic | Coefficient | Standard Error | Probit | Standard Error |

| Race, gender, nativity, and age¶ | ||||

| Race (reference = white) | ||||

| Black | −0.80* | 0.15 | −0.30* | 0.09 |

| Other | −0.67* | 0.22 | −0.14 | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 0.02 | 0.17 | −0.24* | 0.12 |

| Gender (reference = male) | ||||

| Female | 0.40* | 0.10 | 0.27* | 0.04 |

| Nativity (reference = U.S. born) | ||||

| Foreign-born | −0.86* | 0.24 | −0.24* | 0.11 |

| Age (reference = 35–44) | ||||

| 18–25 | −0.33 | 0.20 | −0.03 | 0.07 |

| 25–34 | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 45–54 | −0.06 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 55–64 | −0.74* | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.09 |

| 65–74 | −1.66* | 0.21 | −0.54* | 0.12 |

| 75+ | −2.25* | 0.26 | −0.73* | 0.13 |

| Race × gender interactions | ||||

| Black × female | 0.16 | 0.30 | −0.17 | 0.09 |

| Other × female | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.36* | 0.12 |

| Hispanic × female | −0.87* | 0.36 | −0.30 | 0.24 |

| Race × nativity interactions | ||||

| Black × foreign | −1.70* | 0.64 | −0.29 | 0.34 |

| Other × foreign | −1.95* | 0.50 | −0.66* | 0.19 |

| Hispanic × foreign | 0.25* | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.22 |

| Race × age interactions | ||||

| Black × 35 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black × 18 | −0.35 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| Black × 25 | −0.62 | 0.41 | −0.16 | 0.14 |

| Black × 45 | −0.83* | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| Black × 55 | −1.55* | 0.50 | −0.02 | 0.21 |

| Black × 65 | −1.26* | 0.57 | −0.30 | 0.43 |

| Black × 75 | 0.38 | 0.81 | 0.13 | 0.56 |

| Other × 35 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Other × 18 | −2.16* | 0.65 | 0.01 | 0.39 |

| Other × 25 | −0.40* | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.30 |

| Other × 45 | −0.98 | 0.65 | −0.17 | 0.28 |

| Other × 55 | −0.83 | 0.59 | −0.17 | 0.30 |

| Other × 65 | −1.76* | 0.66 | −0.44 | 0.22 |

| Other × 75 | −2.57* | 0.77 | −0.89* | 0.36 |

| Hispanic × 35 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hispanic × 18 | −1.52* | 0.55 | −0.13 | 0.32 |

| Hispanic × 25 | 0.53 | 0.54 | −0.12 | 0.25 |

| Hispanic × 45 | −0.57 | 0.47 | −0.05 | 0.24 |

| Hispanic × 55 | −0.70 | 0.61 | −0.36 | 0.25 |

| Hispanic × 65 | −0.09 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.26 |

| Hispanic × 75 | −1.24* | 0.57 | −0.14 | 0.39 |

| Other demographic | ||||

| Marital status (reference = single) | ||||

| Married, living with partner | −0.38* | −0.10 | ||

| Socioeconomic | ||||

| Income (in $10,000) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Education (reference = HS grad) | ||||

| < HS | −0.17 | 0.16 | −0.12* | 0.04 |

| Some college | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| College grad | 0.54* | 0.12 | 0.26* | 0.07 |

| Language of interview (reference = English) | ||||

| Spanish | −0.33 | 0.48 | −0.27 | 0.19 |

| Geography | ||||

| Population size (reference = urban>200K) | ||||

| Urban < 200K | −0.78* | 0.36 | −0.14* | 0.02 |

| Rural | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Insurance status (reference = employer-based) | ||||

| Uninsured | 0.16 | 0.27 | −0.28* | 0.11 |

| Medicare | 0.71* | 0.21 | 0.33* | 0.14 |

| Medicaid | 0.73* | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Other insurance | 0.93 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

| Self-insured | 0.30 | 0.21 | −0.18* | 0.07 |

| Military/other public | 1.90* | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.21 |

| Managed care | −0.03 | 0.16 | −0.06 | 0.05 |

| Mental health coverage | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Needs referral or approval to see mental health specialist | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.19* | 0.04 |

| Health status | ||||

| Physical health conditions | ||||

| Asthma | −0.22 | 0.15 | −0.09 | 0.05 |

| Diabetes | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

| Hypertension | 0.36* | 0.13 | 0.17* | 0.06 |

| Arthritis | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Physical disability | −0.41 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Trouble breathing | −0.16 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Cancer | −0.37 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.14 |

| Neurological disorder | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.55* | 0.15 |

| Stroke | 0.32 | 0.31 | −0.19 | 0.21 |

| Angina | −0.07 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| Back problem | 0.33* | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Ulcer | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.07 |

| Liver diagnosis | −0.02 | 0.41 | −0.11 | 0.28 |

| Migraine | −0.14 | 0.12 | 0.12* | 0.05 |

| Bladder infection | −0.37* | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| Gynecological problem | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.15* | 0.07 |

| Chronic pain | −0.15 | 0.13 | 0.19* | 0.09 |

| Health scales (0–100) | ||||

| PCS12 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.003 |

| MCS12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| MHI5 | −0.02* | 0.00 | −0.01* | 0.001 |

| Activity limitation (reference = 0 days) | ||||

| 1–2 days | 0.41* | 0.13 | 0.17* | 0.05 |

| 3–14 days | 0.37* | 0.13 | 0.30* | 0.07 |

| 15–28 days | −0.14 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Mental health status | ||||

| GAD | 0.65* | 0.14 | 0.23* | 0.11 |

| MDD | 1.00* | 0.14 | 0.53* | 0.08 |

| Dysthymia | 0.07 | 0.17 | −0.004 | 0.10 |

| Manic | 0.42* | 0.16 | 0.32* | 0.08 |

| Psychosis | 0.55* | 0.20 | 0.62* | 0.12 |

| Panic disorder | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.38* | 0.09 |

| Problem alcohol | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.23* | 0.08 |

| Problem drug | 0.58* | 0.23 | 0.28* | 0.08 |

Significantly different from 0 at p <.05.

GLM and probit coefficients and standard errors take into account sampling weights and stratification used to make HCC sample representative of U.S. population.

There were 257 observations dropped because of missing data.

Likelihood ratio (χ2) test comparing regressions with and without sites χ2(69) = 107.5, p <.003.

Race, gender, and age coefficients are centered around the means so that regression coefficients on a given characteristic and their significance can be directly interpreted as the difference by race from the overall mean of the characteristic.

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; GLM, generalized linear model.

The second pair of columns of coefficients describes a probit model identifying the impact of the same set of covariates on any health care expenditure. Being black or Hispanic negatively affected the probability of any health care expenditure, but there was little evidence for gender or age interactions. The effects of SES and health condition variables are similar to those in the expenditure model.

The first panel of Table 3 compares expenditures for whites and racial/ethnic minorities. Simple means (repeated from Table 1) show differences between groups in outpatient expenditures. Hispanics on average spend slightly more than whites, while blacks spend less. The second row, “IOM Disparity,” summarizes predictions after transformation to adjust for age, sex and health status variables. After blacks are given the white distribution of health status, the estimated disparity is $47.63, more than half of the white spending, and much bigger than the difference in simple averages. The disparity is bigger than the difference because blacks are on average less healthy than whites, and when we assign them the white distribution of health status, their predicted use falls, widening the gap with the white average.

Table 3.

Racial/Ethnic Differences and Disparities in Means and Predicted Outpatient Expenditures—Five Comparisons (N = 9,328)*

| White | Black | Hispanic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE† | Est | SE | Difference/ Disparity | SE | Est | SE | Difference/ Disparity | SE | |

| Predicted outpatient expenditure | ||||||||||

| Simple means (difference) | $91.90 | 5.5 | $70.48 | 15.4 | $21.43 | 16.4 | $100.10 | 17.9 | −$8.20 | 18.7 |

| GLM IOM—age, sex, and health status adjustment (disparity)‡ | $91.07 | 4.7 | $43.44 | 12.7 | $47.63 | 13.5 | $66.91 | 63.7 | $24.16 | 64.2 |

| GLM IOM—age, sex, HS, and health insurance adjustment (disparity)§ | $91.07 | 4.7 | 41.83 | 15.4 | $49.24 | 16.1 | 66.35 | 62.0 | $24.72 | 63.3 |

| GLM IOM—age, sex, HS, HI, and geography adjustment (disparity)¶ | $84.22 | 4.7 | $45.63 | 21.3 | $38.59 | 21.3 | $$79.23 | 51.1 | $5.00 | 51.7 |

| GLM residual direct EFFECT predictions (disparity)∥ | $91.07 | 4.7 | $48.08 | 5.9 | $43.00 | 7.0 | $112.67 | 26.3 | −$21.60 | 26.0 |

| Predicted probability of any outpatient expenditure | ||||||||||

| Simple means (difference) | 21.8% | 0.8 | 16.6% | 1.5 | 5.3% | 1.7 | 17.1% | 0.9 | 4.8% | 1.2 |

| Probit IOM—age, sex, and health status adjustment (disparity)‡ | 21.7% | 0.8 | 14.2% | 2.2 | 7.5% | 2.2 | 9.6% | 2.2 | 12.1% | 2.3 |

| Probit IOM—age, sex, HS, and health insurance adjustment (disparity)§ | 21.7% | 0.8 | 14.6% | 2.2 | 7.1% | 2.3 | 10.5% | 2.9 | 11.2% | 2.7 |

| Probit IOM—age, sex, HS, HI, and geography adjustment (disparity)¶ | 21.3% | 0.3 | 14.9% | 2.3 | 6.4% | 2.5 | 9.4% | 3.1 | 11.9% | 3.2 |

| Probit residual direct effect predicted probabilities (disparity)∥ | 21.7% | 0.8 | 14.7% | 0.6 | 7.0% | 0.2 | 15.5% | 0.6 | 6.2% | 0.2 |

Means, predictions, and standard errors take into account sample selection weights and stratification used to transform HCC sample to be representative of U.S. population.

Standard errors were calculated based on variance estimation using predictions from a fractional jackknife resampling design (Fay 1993). Within each stratum, the weight for one PSU was halved and the remaining weight was redistributed proportionally to the other PSU(s).

Predicted values using coefficients from regression model (either GLM or probit). The IOM disparity adjusts all minority health status values to the white distribution.

Predicted values using coefficients from regression model (either GLM or probit). The IOM disparity adjusts all minority health status values to the white distribution. Health insurance is treated as an indicator of health status.

Predicted values using coefficients from regression model (either GLM or probit), but with minority health status values (including health insurance) adjusted to equal whites and all geographical site variables held constant at the value that corresponds to their weighted proportion of the sample size.

Predicted values of whites with race variable and race interaction variables artificially set to black and Hispanic values.

GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; MDD, major depressive disorder; GLM, generalized linear model; IOM, Institute of Medicine.

The corresponding transformation of Hispanic health status leads to an estimate of a disparity of $24.16 (27 percent of the white spending average) for Hispanics, even though this group had greater actual spending than whites. There are very few Hispanics in the three older age groups, which have significantly lower rates of spending on mental health than the younger groups. Adjusting the health status distribution (of which age is a component) of Hispanics to that of whites makes them older, reducing the predicted use for Hispanics, and contributing to a disparity between Hispanics and whites.

Adjusting for differences in type of health insurance coverage (treating insurance as a health status measure), reported in the third row of the table, makes little difference to the estimated disparities. Although whites tend to be in more generous health insurance plans, our data do not allow us to pick up disparities mediated through this effect because people in less favorable plans, like Medicaid, are sicker, and have higher rates of use, even after adjusting for other factors in the model.

Geographical adjustments substantially affect the calculation of disparities. If we adjust for geography (thereby excluding the component of disparities mediated by geography), measured disparities fall for blacks and fall markedly for Hispanics, because Hispanics are concentrated in low-use areas. Finally, the residual race effect underestimates the disparity for blacks, and finds no disparities for Hispanics.

The second panel of Table 3 contains the results for the probit model for any use of mental health services. All differences and disparities in probabilities of use are positive, meaning whites use more frequently than members of racial/ethnic minorities both in unadjusted comparison and after any form of adjustment. As in the case of the expenditure model, IOM definitions of disparity yield the larger disparities for blacks and Hispanics, making more of a difference for Hispanics than for blacks. Geographical adjustment makes much less of a difference in the probit analysis.

DISCUSSION

To understand disparities and monitor progress against them, we need agreement on a rigorous definition of “disparity.” The IOM has proposed a definition of disparities that can be used to standardize methods and permit comparisons across groups, over time, and across service systems. This paper is the first to implement the IOM definition with survey data. The IOM definition rules out health status and preferences as mediators, but recognizes the mediating role of variables characterizing the individual's SES, the health care system, and other factors. As minorities and whites differ markedly in income and other mediators, these SES-related variables contribute to racial/ethnic disparities. In our analyses, the IOM definition found larger disparities between whites and minorities than the residual race effect excluding SES-mediated differences.

The framework in this paper implies a way to answer a question that clouds research on health care disparities: if the discrepancies in service use between whites and minorities are “explained” by SES or insurance, does that mean there are no racial/ethnic disparities? This question is behind the recent controversy regarding a congressionally mandated report on health service disparities prepared by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). According to Bloche (2004), the internal rewrite minimizing findings of racial/ethnic disparities was based on the argument that the research literature “failed to show that race mattered by itself, apart from social class and insurance status.” Bloche's critique, consistent with the IOM approach, points out that racial/ethnic disparities are still unfair, and worthy of policy attention, even if they arise through differences in income, wealth, or insurance.

This paper introduces an innovative method for adjusting for health status, addressing an important statistical issue for research on racial/ethnic disparities and other health services research. Models for health care access or expenditures are typically nonlinear. With these models, adjusting for health status by substituting group means can be misleading. We show how to adjust for health status by transforming the distribution of health status of the minority group to the distribution of the white group.

Adequate measurement of health status is obviously a critical step in an empirical assessment of disparities, and continued work on this task is needed. We chose data from the HCC partly because they included measures of elements of health status relevant to use of outpatient mental health services. Yet our findings expose limitations in the measurement of health status even in such a well-designed survey. We could not fully specify the IOM's recommended approach to estimating disparities in treatment without measures of preferences, an important limitation of our study. If some SES measures, such as education, are related to preferences, then some of the differences mediated through these variables might not be considered unfair. Because the idealized concept of preference purged of any effect of past experience is so remote from what we are likely able to measure, this limitation is likely to handicap most empirical research on disparities.

The IOM definition distinguishes between health status and preferences, which should be adjusted for to identify disparities, and other factors, which should not. Competing arguments could be made to treat some variables either as measures of health status/preferences or as potential mediators of disparities. Geography is one such variable, but there are others, such as education, nativity, and marital status. One approach to deal with ambiguity in classification of variables is to conduct a more extensive sensitivity analysis than we did in this paper. Such an analysis could be the basis of a decomposition of the sources of disparities in terms of the various mediators identified in the empirical analysis. Disparities mediated through education or income might be very difficult to address in the short term, but disparities mediated through insurance coverage might be more amenable to changes in health policy.

Finally, the main purpose of our paper was to propose a way to implement the conceptually appealing definition of a racial/ethnic disparity in health services use proposed in the Unequal Treatment report. We hope we have encouraged application of the IOM framework to other data for assessing disparities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant P01 MH59876 from the National Institute of Mental Health. We are grateful to Richard Frank, Haiden Huskamp, Ellen Meara, Rachel Mosher, and Patrick Shrout for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

NOTES

Page 32 of the IOM report states: “The study committee defines disparities in health care as racial or ethnic differences in the quality of health care that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention.” The report then refers to a figure, reproduced here as Figure 1. The definition we state in this paper is a simplification of this definition in the sense that we regard “appropriateness of intervention” as part of “clinical need,” and we leave out the qualifier, “not due to access-related factors.” This qualifier seems to us to be inconsistent with the figure, which includes health care system factors (including insurance among others) among the sources of disparities. The IOM report addressed disparities arising from within the clinical encounter but recognized that disparities can also be due to such factors operating prior to that encounter. The IOM report contains an extended footnote to the term “preferences” in the definition, reflecting the difficulties of this concept. We discuss the role of preferences in our empirical work later in the paper.

See, for comparison, Moy, Dayton, and Clancy (2005) who describe the methodology for defining a disparity in the National Healthcare Disparity Report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). They acknowledge the merits of the IOM approach but choose, instead, to define a disparity in two alterative ways: as a simple unadjusted difference in rates between two populations, or as the race/ethnicity coefficient in a multivariante model with many covariates including income, insurance and others (our residual race/ethnicity effect). They argue that health status variables are not available in the datasets they use in order to implement an IOM approach. We discuss these approaches in relation to ours in the next section.

Disparities in health (as distinct from health care) are also a matter for social concern. Quantifying health disparities involves different methodologies than those presented here.

The motives behind discrimination could include prejudice, stereotypes, or, “rational” decisions by the provider to take the race/ethnicity of a patient into account in treatment decisions because of a different underlying disease prevalence or communication problems with minorities (IOM 2002; Balsa and McGuire 2003). For an application to mental health care, see Balsa, McGuire, and Meredith (2005). Whatever the motive, even if a benign one, the resulting discrimination can still contribute to disparities.

See Kawachi, Daniels, and Robinson (2005) for illustrations of the empirical relation between class and race and a discussion of their conceptual connections.

Not all racial and ethnic disparities in mental health entail minorities receiving less than whites. Clinicians in psychiatric emergency services prescribe both more and higher doses of oral and injectable antipsychotic medications to African Americans than to whites (Segal, Bola, and Watson 1996), even when research recommends lower dosages to African Americans due to their slower metabolizing of some antidepressants and antipsychotic medications (Livingston et al. 1983; Bradford, Gaedigk, and Leeder 1998). There is substantial evidence that African American and Latino patients are over-diagnosed with schizophrenia (Mukherjee et al. 1983; Neighbors et al. 1989). African Americans are more likely than whites to be hospitalized in specialized psychiatric units and hospitals (Snowden and Cheung 1990; Breux and Ryujin 1999).

MEPS is a nationally representative survey of health care use and spending of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. We used data from the following MEPS files to obtain national average expenditures: 1996 Prescribed Medicines File, 1996 Hospital Inpatient Stays File, 1996 Emergency Room Visits File, 1996 Outpatient Visits File, and the 1996 Office Based Provider Visits.

For other papers using alcohol, drug, and mental conditions from the HCC, see Sturm and Gresenz (2002); Wells et al. (2002); and Sturm et al. (1999).

Some alternative counterfactual analyses are also in accord with the IOM approach. We could ask, “how much more (or less) treatment would minorities receive than they do now if they were the same as whites in all ways except for health status?” This formulation holds health status constant while counterfactually shifting the distribution of all other variables including race. It also requires a similar set of steps to those laid out here.

HCC documentation recommends the use of SUDAAN software to account for finite population correction factors in the multistage design; however, we found the differences in variance estimation between the two programs to be negligible.

A different method was used by Barsky et al. (2002) who sought to adjust for the effect of earnings on wealth across racial groups. They altered the weights for the white observations so that the newly weighted white sample had a distribution of earnings equivalent to the black distribution of earnings, and then used the transformed data to measure the racial disparity in wealth not because of earnings.

Our approach minimizes the aggregate “distance” in movement of each health status variable (Millar 1984) and preserves the nonparametric (Spearman) correlations.

Current health status could be a function of disparities in access to health care in the past. Our method computes disparities attributable to current SES factors and current operation of the health care system.

An alternative is to use the mean of group predicted values as a basis for computation of “differences.” This has the advantage, when compared to disparities, of accounting for any difference introduced as an artifact of model fit. In our case, the GLM and probit models predicted the means for each group accurately and there is almost no difference in the difference computed with means and with predicted means. To simplify the discussion we present only actual group means.

The RDE is a modification of the use of predictive margins with complex survey data developed by Graubard and Korn (1999).

REFERENCES

- Aalto-Setala T, Harasilta L, Marttunen M, Tulio-Henriksson A, Poikolainen K, Aro H, Lonqvist J. Major Depressive Episode among Young Adults: CIDI-SF versus SCAN Consensus Diagnoses. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(7):1309–14. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa A, McGuire T G. Prejudice, Clinical Uncertainty and Stereotyping as Sources of Health Disparities. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;8(22):89–116. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa A, McGuire T G, Meredith L S. Testing for Statistical Discrimination in Health Care. Health Services Research. 2005;40(1):227–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsky R, Bound J, Charles K K, Lupton J P. Accounting for the Black–White Wealth Gap: A Nonparametric Approach. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2002;97:663–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bloche M G. Erasing Racial Data Erased Report's Truth. 2004. Washington Post, February 15.

- Bradford L D, Gaedigk A, Leeder J S. High Frequency of CYP2D6 Poor and ‘Intermediate’ Metabolizers in Black Populations: A Review and Preliminary Data. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1998;34:797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaux C, Ryujin D. Use of Mental Health Services by Ethnically Diverse Groups within the United States. Clinical Psychologist. 1999;52:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Buntin M, Zaslavsky A M. Too Much Ado about Two-Part Models and Transformation? Comparing Methods of Modeling Medicare Expenditures. Journal of Health Economics. 2004;23(3):525–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Febo V, Rubio-Stipec M, Fernandez R L, Hasin D. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): Reliability and Concordance with Clinical Diagnoses in a Hispanic Population. Journal of Studies of Alcohol. 1999;60(6):790–9. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Skinner J. Geography and Racial Health Disparities. NBER Working Paper No. 9513. 2003.

- Cooper-Patrick L, Powe N R, Jenckes M W, Gonzales J J, Levine D M, Ford D E. Identification of Patient Attitudes and Preferences Regarding Treatment of Depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12:431–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: USDHHS, SAMSHA, CMHS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture Race and Ethnicity a Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: USDHHS, SAMSHA, CMHS; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay R. Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods. American Statistical Association; 1993. Valid Inferences from Imputed Survey Data; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Graubard B I, Korn E L. Predictive Margins with Survey Data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Daniels N, Robinson D E. Health Disparities by Race and Class: Why Both Matter. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):343–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R C, Berglund P A, Zhao S, Leaf P, Kouzis A C, Bruce M L, Freidman R L, Grosser R C, Kennedy C, Narrow W E, Kuehnel T G, Laska E M, Manderscheid R W, Rosenheck R A, Santoni T W, Schneier M. The 12-Month Prevalence and Correlates of Serious Mental Illness (SMI) Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R C, Wittchen H U, Abelson J, Zhao S. Methodological Issues in Assessing Psychiatric Disorders with Self-Reports. In: Stone A A, Turkkan J S, Barchrach C A, Jobe J B, Kurtzman H S, Cain V S, editors. The Science of Self-Report: Implications for Research and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 229–55. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston R L, Zucker D K, Isenberg K, Wetzel R D. Tricyclic Antidepressants and Delirium. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1983;44:173–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning W G, Mullahy J. Estimating Log Models: To Transform or Not to Transform? Journal of Health Economics. 2001;20(4):461–95. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder J A. Generalized Linear Models. London: Chapman & Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Millar P W. A General Approach to the Optimality of Minimum Distance Estimators. Transactions of the Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1984;19(2):120–6. [Google Scholar]

- Moy E, Dayton E, Clancy C M. Compiling the National Healthcare Disparities Reports. Health Affairs. 2005;24(2):376–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Shukla S, Woodle J, Rosen AM, Olarte S. Misdiagnosis of Schizophrenia in Bipolar Patients: A Multiethnic Comparison. Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:1571–74. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors H W, Jackson J S, Campbell L, Williams D R. The Influence of Racial Factors on Psychiatric Diagnosis: A Review and Suggestions for Research. Community Mental Health Journal. 1989;24:301–11. doi: 10.1007/BF00755677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park R. Estimation with Heteroscedastic Error Terms. Econometrica. 1966;34:888. [Google Scholar]

- Segal S P, Bola J R, Watson M A. Race, Quality of Care, and Antipsychotic Prescribing Practices in Psychiatric Emergency Services. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47:282–6. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden L R, Cheung F K. Use of Inpatient Mental Health Services by Members of Ethnic Minority Groups. American Psychologist. 1990;45:347–55. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Gresenz C R. Relations of Income Inequality and Family Income to Chronic Medical Conditions and Mental Health Disorders: National Survey. British Medical Journal. 2002;324(7328):20–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7328.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R, Gresenz C E, Sherbourne C D, Minnium K, Klap R, Bhattacharya J, Farley D, Young A, Burnam M, Wells K. The Design of Health Care for Communities: A Study of Health Care Delivery for Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Conditions. Inquiry. 1999;36(2):221–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Young K. Research on Psychotherapy on Culturally Diverse Populations. In: Bergin A, Garfield S, editors. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 783–817. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman L K, Robins L N, Earls F. Treatment-Seeking for Depression by Black and White Americans. Social Science and Medicine. 1987;24:187–96. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P S, Berglund P A, Kessler R C. Recent Care of Common Mental Disorders in the United States. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:284–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic Disparities in Unmet Need for Alcoholism, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Care. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(2):2027–32. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K B, Sherbourne C D, Sturm R, Young A S, Burnam M A. Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Care for Uninsured and Insured Adults. Health Services Research. 2002;37(4):1055–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.65.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young A S, Klap R, Sherbourne C D, Wells K B. The Quality of Care for Depressive and Anxiety Disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A Y, Snowden L R, Sue S. Differences between Asian- and White-Americans' Help-Seeking and Utilization Patterns in the Los Angeles Area. Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26:317–26. [Google Scholar]