Abstract

Objectives

To describe nurse migration patterns in the Philippines and their benefits and costs.

Principal Findings

The Philippines is a job-scarce environment and, even for those with jobs in the health care sector, poor working conditions often motivate nurses to seek employment overseas. The country has also become dependent on labor migration to ease the tight domestic labor market. National opinion has generally focused on the improved quality of life for individual migrants and their families, and on the benefits of remittances to the nation. However, a shortage of highly skilled nurses and the massive retraining of physicians to become nurses elsewhere has created severe problems for the Filipino health system, including the closure of many hospitals. As a result, policy makers are debating the need for new policies to manage migration such that benefits are also returned to the educational institutions and hospitals that are producing the emigrant nurses.

Conclusions and Recommendations

There is new interest in the Philippines in identifying ways to mitigate the costs to the health system of nurse emigration. Many of the policy options being debated involve collaboration with those countries recruiting Filipino nurses. Bilateral agreements are essential for managing migration in such a way that both sending and receiving countries derive benefit from the exchange.

Keywords: Nursing migration, Philippines, health human resources development

This case study provides information on Philippine nurse migration patterns and presents a sending-country perspective on the benefits and costs of this phenomenon. Our aim is to identify strategies that will ensure that international nurse migration is beneficial for both sending and receiving countries.

The Philippines is the largest exporter of nurses worldwide. For many decades, the country has consistently supplied nurses to the United States and Saudi Arabia. In recent years, other markets have emerged and opened for nurses including the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Ireland. This case study synthesizes existing information and reports on new findings to establish the magnitude and patterns of nurse migration and explore debates within the country regarding the impact of this phenomenon.

Data from a health worker migration case study commissioned by the International Labor Organization (ILO) was reanalyzed to focus specifically on nurses (Lorenzo et al. 2005). Literature review, records review, and focus groups comprised of health workers from five geographic districts were also conducted. Previous studies on Filipino worker migration were reviewed and integrated with available data from government and other field records to validate study results and make the study more robust. In addition, key informant interviews were conducted with selected stakeholders including professional leaders and policy makers to determine their perceptions of nurse migration, describe current migration management programs, and explore future policy directions for nursing and health human resource development in the Philippines.

Precise figures on nurse migration are difficult to obtain because many of those who seek work overseas are recruited privately and not officially documented by Philippines Overseas Employment Agency (POEA). Moreover, Department of Foreign Affairs data are also incomplete as many people leave as tourists and subsequently become overseas workers. We therefore suspect that the data we present on both migration of all occupations and nurse migration specifically are generally underreported.

CONTEXT OF NURSE MIGRATION

The Philippines has too few jobs for its population. The unemployment rate has steadily increased from 8.4 percent in 1990 to 12.7 percent in 2003 (BLES 2003). Even for those with jobs, conditions are difficult. One out of every five employed workers is underemployed, underpaid, or employed below his/her full potential. As a result, the number of Filipinos working abroad has steadily risen and from 1995 to 2000; overseas deployment of workers increased by 5.32 percent annually. Employment abroad provides work to job-seeking Filipinos and is a major generator of foreign exchange. Remittances from overseas Filipino workers of all occupations have grown from U.S.$290.85 million in 1978 to U.S.$10.7 billion in 2005 (Tarriela 2006). A large portion of this comes from international service providers, with nurses constituting the largest group of professional workers abroad.

Filipino labor migration was originally intended to serve as a temporary measure to ease unemployment. Perceived benefits included stabilizing the country's balance-of-payments position and providing alternative employment for Filipinos. However, dependence on labor migration and international service provision has grown to the point where there are few efforts to address domestic labor problems (Villalba 2002).

Movement of health workers from the Philippines as temporary or permanent migrant workers can be traced back to the 1950s. At that time, the objective of working overseas was generally to obtain more advanced training and return home to improve the quality of Filipino health services. Beginning in the late 1960s, countries in the Middle East and North America began to actively recruit health workers. Many of those who went to North America as students stayed on as migrant workers and were ultimately granted residency status (Corcega et al. 2000). By the late 1990s, in the face of widespread global nursing shortages, recruitment conditions changed and destination countries like the United States made recruitment offers both more attractive and more permanent, creating strong “pull factors.”

There are an estimated 1,600 hospitals in the country, about 60 percent of which are private. The government is the biggest employer of nurses with an estimated 16,000 jobs at the national and government facilities. There is no reliable estimate for the number of nursing positions at small local or private institutions (DBM 2005). Both the conditions and the quality of care provided by the small and private hospitals vary greatly and poor working conditions and low pay at many of these institutions also impact nurse migration by creating “push factors.” As a result, the Philippines has begun to experience massive migration of nurses and other health workers to the point that domestic demand for these workers is not being met.

PATTERNS OF NURSE MIGRATION

Nurse Supply and Employment

Nurses now make up the largest group of direct health care providers in the Philippines. While physicians have traditionally dominated the health care system, in recent years nurses have emerged as a strong force, often co-managing health care facilities. Both the domestic and foreign demand for nurses has generated a rapidly growing nursing education sector now made up of about 460 nursing colleges that offer the Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) program and graduate approximately 20,000 nurses annually (CHED 2006). Based on production and domestic demand patterns, the Philippines has a net surplus of registered nurses. However, the country loses its trained and skilled nursing workforce much faster than it can replace them, thereby jeopardizing the integrity and quality of Philippine health services.

The total supply of nurses who were registered at some time, adjusted for deaths and retirement, was 332,206 as of 2003, according to data provided by the Professional Regulations Commission, (Lorenzo et al. 2005). Of these, it is estimated that only 58 percent were employed as nurses either in the Philippines or internationally. There are no data on why the remainder left the profession. As shown in Table 1, the majority (84.75 percent) of employed nurses were working abroad. Among the 15.25 percent employed in the Philippines, most were employed by government agencies and the rest worked in the private sector or in nursing education institutions (Corcega et al. 2000).

Table 1.

Estimated Number of Employed Filipino Nurses by Work Setting, 2003

| Work Setting | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| I. Local/national | 29,467 | 15.25 |

| A. Service | ||

| 1. Government agencies | 19,052 | 9.86 |

| 2. Private agencies | 8,173 | 4.23 |

| B. Education | 2,241 | 1.16 |

| II. International | 163,756 | 84.75 |

| Total | 193,223 | 100 |

Source: Corcega, Lorenzo, and Yabes (2000).

These figures were calculated based on known positions in the domestic market and recorded deployment abroad.

Additionally, as in many countries, there is geographic mal-distribution of employed nurses, with a strong correlation between place of education and place of employment. The national capital region (NCR), including Metro Manila, consistently contributed the highest number of licensed nurses with 33.4 percent of total licensure examination passers between 2001 and 2003 (PRC 2005). Similarly, doctors tend to practice in large urban areas such as the NCR (21.78 percent) and region IV (11.59 percent), while many rural areas and towns are left unattended. These urban areas have also a disproportionately higher share of health facilities in the country. More remote geographic regions report chronic shortages of nurses, doctors, and other health care workers (NSO 2005).

Doctors who have retrained as nurses (known as “nurse medics”) in order to seek overseas employment are a new and growing phenomenon. While exact numbers are not available, a study on this trend showed that in 2001, approximately 2,000 doctors became nurse medics and by 2003, that number increased to about 3,000 (Pascual, Marcaida, and Salvador 2003). In 2005, approximately 4,000 doctors were enrolled in nursing schools across the country (Galvez-Tan 2005) and in 2004, the Philippines Hospital Association estimated that 80 percent of all public sector physicians were currently or had already retrained as nurses (PHA 2005).

Nurse Outflows and Destination Countries

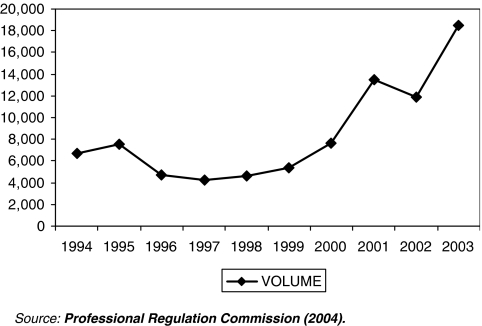

While the numbers of most health professionals who go abroad has remained relatively constant over the years, nurse migration has fluctuated a fair amount as shown in Figure 1. We have used data from the Professional Regulation Commission, which we consider the most accurate source, although they acknowledge that because of the multiple entry routes to the United States, data on migration to that country are severely underreported. As noted in the introduction, data on migration, including that from the POEA, are often severely underreported because they cover only certain types of emigrants and because many nurses leave the country using other types of visas, such as student or tourist visas (Adversario 2003). POEA also does not include nurses that have returned to the Philippines or those who renew their contracts with the same employer (POEA 2005a). In one example, the U.S. Embassy in Manila reported that about 7,994 nurses were deployed under the temporary H1B and permanent EB3 visas in 2004 (Philippine Embassy 2005). For the same year, however, POEA reported only 373 newly hired nurses deployed to the United States (POEA 2005b).

Figure 1.

Trends of Deployment Filipino Nurses, 1994–2003

From 1992 to 2003, the major destinations of Filipino emigrant nurses have been Saudi Arabia, the United States, and the United Kingdom. These countries have employed 56.8, 13.14, and 12.25 percent, respectively, of the cumulative total of Filipino nurses sent abroad since 1992 (POEA 2004). These remain the preferred destinations because of perceived advantages in compensation, working conditions, and career opportunities. Other common destinations for deployed Filipino nurses were Libya, United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Singapore, Kuwait, Qatar, and Brunei (POEA 2004). The majority of nurse medics also go to the United States, United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia (POEA 2004).

Profile of Filipino Nurse Migrants

Data for this section were derived from 48 focus groups held in five localities, both urban and rural, with Filipino health workers, some of whom also plan to leave the country. They reported that nurses leaving the country to work abroad are predominantly female, young (in their early twenties), single, and come from middle income backgrounds. While a few of the migrant nurses have acquired their master's degree, the majority have only basic university education. Many, however, have specialization in ICU, ER, and OR, and they have rendered between 1 and 10 years of service before they migrated (Lorenzo et al. 2005).

According to Pascual, the migrant nurse medics have a slightly different profile. They are also predominantly female, but are older, more likely to be married, and have higher incomes. About 24 percent are single, while 76 percent are married with an average of one to three children and they are 37 years old and older. The nurse medics' income bracket in the Philippines ranges from below U.S.$2,400 to U.S.$9,600 annually. They have specializations in the following areas: internal/general medicine (30 percent), pediatrics (14 percent), family medicine (13 percent), surgery (8 percent), and pathology (6 percent). The remaining 29 percent have other specializations including orthopedics, obstetrics, anesthesiology, and public health. The majority (63 percent) of them had practiced as doctors for more than 10 years. Thirty-four percent have pending applications abroad, while 26 percent have been offered jobs abroad already. More than half (66 percent) plan to leave the country in 6 months to 2 years time. The United States is their top destination country (Pascual 2003).

Reasons for Leaving: Push and Pull Factors

A variety of reasons for migrating have been reported. The focus groups revealed the following perceived push and pull factors for migrating.

Push Factors

Economic: low salary at home, no overtime or hazard pay, poor health insurance coverage.

Job related: work overload or stressful working environment, slow promotion.

Socio-political and economic environment: limited opportunities for employment, decreased health budget, socio-political and economic instability in the Philippines.

Pull Factors

Economic: higher income, better benefits, and compensation package.

Job related: lower nurse to patient ratio, more options in working hours, chance to upgrade nursing skills.

Personal/family related: opportunity for family to migrate, opportunity to travel and learn other cultures, influence from peers and relatives.

Socio-political and economic environment: advanced technology, better socio-political and economic stability.

Focus groups were also conducted among nurse medics who still serve as government doctors in two urban areas in the South. They were employed in provincial and local government unit (LGU) hospitals, were municipal health officers, or were private practitioners. They reported that their career shifts were attributed to the very low compensation and salaries in the Philippines, feeling of hopelessness about the current situation of political instability, graft and corruption in the Philippines, poor working conditions, and the threat of malpractice lawsuits (Galvez-Tan, Fernando, and Virginia 2004). Nurse medics were also drawn to attractive compensation and benefits packages, more job opportunities, career growth, and more socio-political and economic security abroad.

Return Migration

While most health workers who seek employment abroad do not return to the Philippines, particularly those who bring their families, others return en route to another job abroad, and some return permanently. For nurses who return, the reasons identified through the focus groups were personal/family, professional, financial, and contract related. The predominant personal reasons included to get married and/or raise children in the homeland, have vacation, return due to homesickness and depression, and to retrieve family members to join them abroad. Professional reasons included wanting to share expertise and seeking professional stability. Financial/social reasons reported were that they had saved enough money to set up a business and or buy a house and a car. Job-related reasons included expired contracts and plans to retire.

IMPACT OF NURSE MIGRATION

Not surprisingly, results from the focus groups revealed that individual migrants and their families were seen as primary winners of the exodus. Respondents pointed out that if the health workers returned to the country, migration would provide benefits to the country in terms of learning technologies used abroad. The migrant was, however, also seen as contributing to the local economy through remittances and reduction of unemployment. Respondents viewed the Filipino health care system and society in general as the losers in the migration equation.

Migration was perceived to impact nursing in the Philippines negatively by depleting the pool of skilled and experienced health workers thus compromising the quality of care in the health care system. One concern among health services managers is that the loss of more senior nurses requires a continual investment in the training of staff replacements and negatively affects the quality of care. Human resources also become more expensive. One health worker expressed this plainly when he said, “We are the one in need of better service yet we are the losers; those countries with better facilities enjoy better care from health professionals” (translation from Filipino statement) (Lorenzo et al. 2005).

Hard evidence regarding the impact of massive nurse migration is only now beginning to be assembled. The Philippine Hospital Association (PHA) recently reported that 200 hospitals have closed within the past 2 years due to shortages of doctors and nurses, and that 800 hospitals have partially closed for the same reason, ending services in one or two wards (PHA November 2005). Shortages have led to failure to meet accreditation standards, which in turn hinders reimbursement and eventually brings financial crisis. Nurse to patient ratios in provincial and district hospitals are now one nurse to between 40 and 60 patients, which is a striking deterioration from the ratios of one nurse to between 15 and 20 patients that prevailed in the 1990s (Galvez-Tan 2005). While previous ratios were not ideal, the current ratios have become dangerous even for the nurses, adding to the loss of morale and desire to migrate for those still employed in the Philippines.

Further evidence of problems can be observed in coverage data reported by the National Statistics Office. The proportion of Filipinos dying without medical attention has reverted to 1975 levels with 70 percent of deaths unattended during the height of nurse and nurse medics migration in 2002–2003 (NSO 2005). This represents a 10 percent increase in the last decade, and many observers attribute the growth of this problem to the nurse medic phenomenon and the resulting shortage of physicians. Perhaps the most troubling indicator of declining access to health services is the drop in immunization rates among children, which have gone from a high of 69.4 percent in 1993 to 59.9 percent in 2003 (Galvez Tan 2005). While there are undoubtedly multiple factors that impact this decline in immunization rates, the association between the lack of health human resources and immunization coverage is indisputable.

POLICY DEBATE

As a result of the impact of nurse and nurse medic migration, a flurry of policy debate has developed as both proponents and opponents of nurse migration realize that health workforce planning is urgently needed. Three major spheres of policy relate to this topic: the labor and employment sector, the trade sector, the health sector, and within that the nursing community.

The labor ministry provides for the promotion, regulation, and protection of migrant workers. The Philippine government first adopted an international labor migration policy in 1974 as a temporary, stop-gap measure to ease domestic unemployment, poverty, and a struggling financial system. The system has gradually been transformed into the institutionalized management of overseas emigration, culminating in 1995 in the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act, or RA 8042, which put in place policies for overseas employment and established a higher standard of protection and promotion of the welfare of migrant workers, their families, and overseas Filipinos in distress (M.T. Soriano, in OECD 2004). That act also, however, foresees moving toward a less regulated international recruitment process, in which the government would eventually have a far smaller role.

Reflecting a generally promigration stance, the Department of Labor and Employment and its attached agencies, the POEA, and Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA) actively explore better employment opportunities and modes of engagement in overseas labor markets and promote the reintegration of migrants upon their return. Instruments developed to this end include predeparture orientation seminars on the laws, customs, and practices of destination countries; model employment contracts that ensure that the prevailing market conditions are respected and the welfare of overseas workers is protected; a system of accreditation of foreign employers; the establishment of overseas labor offices (POLOs) that provide legal, medical, and psycho-social assistance to Filipino overseas workers; a network of resource centers for the protection and promotion of workers' welfare and interests; and reintegration programs that provide skills training and assist returning migrants to invest their remittances and develop entrepreneurship.

Within this sector, the current migration debates center on two issues. The first issue relates to the impact of deregulation and liberalization of the migration services of recruitment entities. Strong differences of opinion exist as to whether this would be positive for the nation and/or for individual migrants. A second issue revolves around whether or not the government should shift its policy from “managing” the flow of overseas migration, which is reactive, to “promoting” labor migration, which is proactive. Right now, migration policy is implicit and reactive to overseas demand. Promoting labor migration would mean actively seeking out international markets and marketing Filipino human resources in selected markets.

The trade and investment sector of the country has shown interest in developing the Philippines' health sector as a magnet for new revenues in their hospital tourism and medical zones initiatives. There has been debate as to whether this would hurt or benefit the Philippines health system. While this might provide significant incentives for retention of the most qualified health workers, jobs developed in this sector may also draw the remaining nurses and physicians away from the already-depleted public and less-profitable private sector facilities that primarily serve the poor.

The issue of nurse migration is, of course, of great concern to the health policy makers. In the area of health workforce policies, the most serious proposal currently being considered is the Department of Health HRH Masterplan for 2005–2030. The HRH Development Network was established in 2006 in order to implement the Masterplan. The Network is composed of representatives of the executive branch, the legislative branch, the private sector, and civil society groups. Congress is currently considering converting this group into a Commission that would be charged with the following:

Review of the past, current, and future scenarios of the nursing and medical human resources.

Create a database of Filipino health human resources.

Develop a 25-year National Health Human Resources Policy and Development Plan.

Develop a unified HHR policy and a National HHR Policy Research Agenda.

Major objectives being considered include the following:

Rational utilization to make more efficient use of available personnel through geographic redistribution, the use of multiskilled personnel, and closer matching of skills to function.

Rational production to ensure that the number and types of health personnel produced are consistent with the needs of the country.

Public sector personnel compensation and management strategies to improve the productivity and motivation of public sector health care personnel.

The nursing sector has also brought to the table a series of proposals that are being considered as part of the Philippine Nursing Development Plan. These strategies include:

The institution of a national network on Human Resource for Health Development, which would be a multisectoral body involved in health human resources development through policy review and program development.

Exploration of bilateral negotiations with destination countries for recruitment conditions that will benefit both sending and receiving countries. Through bilateral negotiations the Philippines may devise investment mechanisms that could be used to improve domestic postgraduate nursing training, upgrade nursing education, increase nurses' compensation, and establish nursing scholarships. Alternatively, multilateral negotiations may be forged with the guidance of international agencies such as the ILO and WHO.

Forging of North–South hospital-to-hospital partnerships so that local hospitals benefit from compensatory mechanisms for every nurse recruited from them. One proposal is that for each nurse recruited, the cost of postgraduate hospital training (estimated at U.S.$1,000 for 2 years at 2002 prices) would be remitted to the hospital from which the nurse has been recruited, allowing the hospital to then train another nurse to join their staff.

If hospital nurses are hired by foreign counterparts, it is suggested that they be given a 6-month leave to return and train local hospital nurses. Health care organizations should also establish returnee integration programs in order to maximize the potentials for skills and knowledge transfer.

The institution of the National Health Service Act (NHSA) which would compel graduates from state-funded nursing schools to serve locally for the number of years equivalent to their years of study.

Health-related organizations such as the PHA, Philhealth, the Board of Nursing, and the Philippine Nurses' Association (PNA) should work to prevent work-related exploitation domestically.

The Philippines should actively participate in debates moderated by international agencies such as the World Health Organization, the International Council of Nurses, and the ILO.

Nurse leaders are hopeful that these strategies will be incorporated into a draft executive order that the Commission would present to the President.

While the outcome of this process is unfolding, it is encouraging that the health sector has taken the lead to shift the terms of the debate. Labor and trade sector buy-in is still essential, but most policy makers agree that the goal should be to manage migration such that both sending and receiving countries benefit from the exchange (WHO 2006). If the Philippines were able to produce and retain enough nurses to serve its own population, there would be widespread support for additional quality nurse production and migration. Attending to source country needs will also benefit the global health workforce and ensure improved quality of health care services for all.

REFERENCES

- Adversario P. “Nurse Exodus Plagues Philippines”. [May 2003];2003 Asia Times Online. Available at http://www.nursing-comments.com.

- Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics. 2003. Occupational Wage Salary.

- Commission on Higher Education (CHED) 2006. List of Nursing Schools and Permit Status.

- Corcega T, Lorenzo FM, Yabes J, De la Merced B, Vales K. Nurse Supply and Demand in the Philippines. The UPManila Journal. 2000;5(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Budget and Management. 2005. Interview of Director Edgardo Macaranas and others.

- Galvez Tan J. “The Challenge of Managing Migration, Retention and Return of Health Professionals”. 2005. Powerpoint Presentation at the Academy for Health Conference, New York.

- Galvez Tan J, Sanchez F, Balanon V. The Philippine Phenomenon of Nursing Medics: Why Filipino Doctors Are Becoming Nurses, Powerpoint presentation October 2004.

- Lorenzo FM, Dela FRJ, Paraso GR, Villegas S, Isaac C, Yabes J, Trinidad F, Fernando G, Atienza J. “Migration of Health Workers: Country Case Study”. The Institute of Health Policy and Development Studies, National Institute of Health, September 2005.

- National Statistics Office (NSO) QUICKSTAT. Databank and Information Services Division, February 2005.

- Pascual H, Marcaida R, Salvador V. “Reasons Why Filipino Doctors Take Up Nursing: A Critical Social Science Perspective”. 2003. Paper Presented During the 1st PHSSA National Research Forum, Kimberly Hotel, Manila, September 17, 2003. Philippine Health Social Science Association, unpublished report.

- Philippine Embassy. RP Embassy to Pursue Continued Deployment of Filipino Nurses in the U.S. Philippine Embassy”. News Release, February 2005.

- Philippine Hospital Association Newsletter, November 2005.

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) 2004. Statistics 1990–2004.

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) 2005a. OFW Deployment by Skill, Country and Sex (1992–2003)

- Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) 2005b. Statistics 1992–2003, August 2005.

- Professional Regulations Commission (PRC) Nurse Licensure Examinations Performance by School and Date of Examination, 2005.

- Soriano MT. in OECD, 2004 [incomplete reference]

- Tarriela FG. “OFW Remittances: Insights”. Manila Bulletin, April 11, 2006.

- Villalba MAC. “Philippines: Good Practices for the Protection of Filipino Women Migrant Workers in Vulnerable Jobs”. 2002. Working Paper No. 8. Geneva: International Labour Office, February 2002.

- World Health Organization. “Working Together”. 2006. World Health Report.