Abstract

Aberrant expression of the human homeobox-containing proto-oncogene TLX1/HOX11 inhibits hematopoietic differentiation programs in a number of murine model systems. Here, we report the establishment of a murine erythroid progenitor cell line, iEBHX1S-4, developmentally arrested by regulatable TLX1 expression. Extinction of TLX1 expression released the iEBHX1S-4 differentiation block, allowing erythropoietin-dependent acquisition of erythroid markers and hemoglobin synthesis. Coordinated activation of erythroid transcriptional networks integrated by the acetyltransferase co-activator CREB-binding protein (CBP) was suggested by bioinformatic analysis of the upstream regulatory regions of several conditionally induced iEBHX1S-4 gene sets. In accord with this notion, CBP-associated acetylation of GATA-1, an essential regulator of erythroid differentiation, increased concomitantly with TLX1 downregulation. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments and glutathione-S-transferase pull-down assays revealed that TLX1 directly binds to CBP, and confocal laser microscopy demonstrated that the two proteins partially colocalize at intranuclear sites in iEBHX1S-4 cells. Notably, the distribution of CBP in conditionally blocked iEBHX1S-4 cells partially overlapped with chromatin marked by a repressive histone methylation pattern, and downregulation of TLX1 coincided with exit of CBP from these heterochromatic regions. Thus, we propose that TLX1-mediated differentiation arrest may be achieved in part through a mechanism that involves redirection of CBP and/or its sequestration in repressive chromatin domains.

Keywords: TLX1/HOX11 oncogene, erythropoiesis, conditional differentiation block, CBP, GATA-1, repressive chromatin domains

Introduction

The murine ortholog of human TLX1 (previously known as HOX11 and TCL3), which is a member of the dispersed NK homeobox gene family, is essential for splenogenesis and the proper development of certain sensory neurons. Although TLX1 is not expressed in the hematopoietic system, its inappropriate activation - frequently owing to translocations involving T-cell receptor (TCR) gene loci - is a recurrent event in human T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) (Owens and Hawley, 2002). We previously reported that enforced expression of TLX1 immortalizes various myeloerythroid progenitors in murine bone marrow, yolk sac and embryonic stem cell (ESC)-derived embryoid bodies (Hawley et al., 1994, 1997; Keller et al., 1998; Owens et al., 2003). Based on these results, we postulated that TLX1 exerts its T-cell oncogenic effects in part by impeding hematopoietic differentiation programs. In support of this hypothesis, we recently demonstrated that retroviral expression of TLX1 disrupted T-cell-directed differentiation of primary murine fetal liver precursors and human cord blood CD34+ stem/progenitor cells in fetal thymic organ cultures (Owens et al., 2006).

The mechanism of the TLX1-mediated differentiation block and, by extension, the manner in which deregulated TLX1 expression induces neoplastic conversion remain to be elucidated (Hawley et al., 1997). Several lines of evidence indicate that TLX1 functions as a transcriptional regulator that can either activate or repress gene expression via direct or indirect modes of action (Dear et al., 1993; Greene et al., 1998; Owens et al., 2003; Riz and Hawley, 2005). A plausible assumption has been that some TLX1 transcriptional activity is mediated by selective recognition of DNA sequences (Dear et al., 1993; Allen et al., 2000). Of note, however, although several genes downstream of TLX1 transcriptional cascades have been identified to date, in no instance has direct binding of TLX1 to the promoter sequences of primary target genes been demonstrated. On the contrary, TLX1 has been shown in many instances to indirectly regulate gene expression in vivo through cooperative protein-protein interactions with other molecules (Kawabe et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1999; Riz and Hawley, 2005).

Recent investigations have identified new recurrent TCR chromosomal translocations in human T-ALL that deregulate the HOXA cluster of the HOX homeobox gene family (Soulier et al., 2005). Genome-wide expression analysis showed that the HOXA-translocated cases shared multiple transcriptional networks with TLX1+ T-ALL samples (Soulier et al., 2005), suggesting a common mechanism underlying these malignancies. Many HOX proteins have been reported to interact with the ubiquitously expressed acetyltransferase co-activator CREB-binding protein (CBP) and its paralog p300 (Shen et al., 2001). In particular, all 14 HOX proteins tested in one study, representing 11 of the 13 paralogous groups, were shown to associate with CBP in a DNA-binding-independent manner and inhibit CBP acetyltransferase activity (Shen et al., 2001). CBP regulates gene expression in most if not all cell types, functioning as a molecular integrator linking a large number of transcription factors to the basal transcriptional machinery. CBP can acetylate a broad range of these transcription factors, which, in most cases, potentiates transcription. Additionally, acetylation of histones by CBP facilitates gene transcription by providing an open chromatin structure (Blobel, 2000). Importantly, mice with CBP haploinsufficiency develop multilineage defects in hematopoietic differentiation and increased hematologic malignancies with age (Kung et al., 2000), whereas conditional inactivation of CBP in murine T-cell precursors results in a high incidence of T-cell tumors (Kang-Decker et al., 2004).

As ectopic expression of HOXA homeobox genes implicated in the pathogenesis of T-ALL also perturbs myeloerythroid differentiation in several model systems (Owens and Hawley, 2002), we reasoned that TLX1 and HOXA oncogenes may act in part by targeting global regulatory circuits that impact cell proliferation and differentiation outcomes. In this regard, a number of oncogenic transcription factors have been observed to inhibit CBP activity in the context of cell differentiation arrest (Blobel, 2000). Among the best characterized examples are those that interfere with CBP-mediated acetylation of the transcription factor GATA-1, a key regulator of erythropoiesis (Blobel et al., 1998; Hung et al., 1999; Hong et al., 2002). In the present work, we established a murine erythroid progenitor cell line, iEBHX1S-4, from ESC-derived embryoid bodies by conditional TLX1 expression and we used this cell line to investigate the mechanism by which TLX1 achieves differentiation arrest. The results suggest a mechanism by which sequestration of CBP by TLX1 within particular subnuclear compartments might limit its access to critical acetylation substrates, such as GATA-1 in the case of erythroid differentiation.

Results

Upregulation of erythroid transcriptional networks in iEBHX1S-4 cells following release of the TLX1-mediated differentiation block

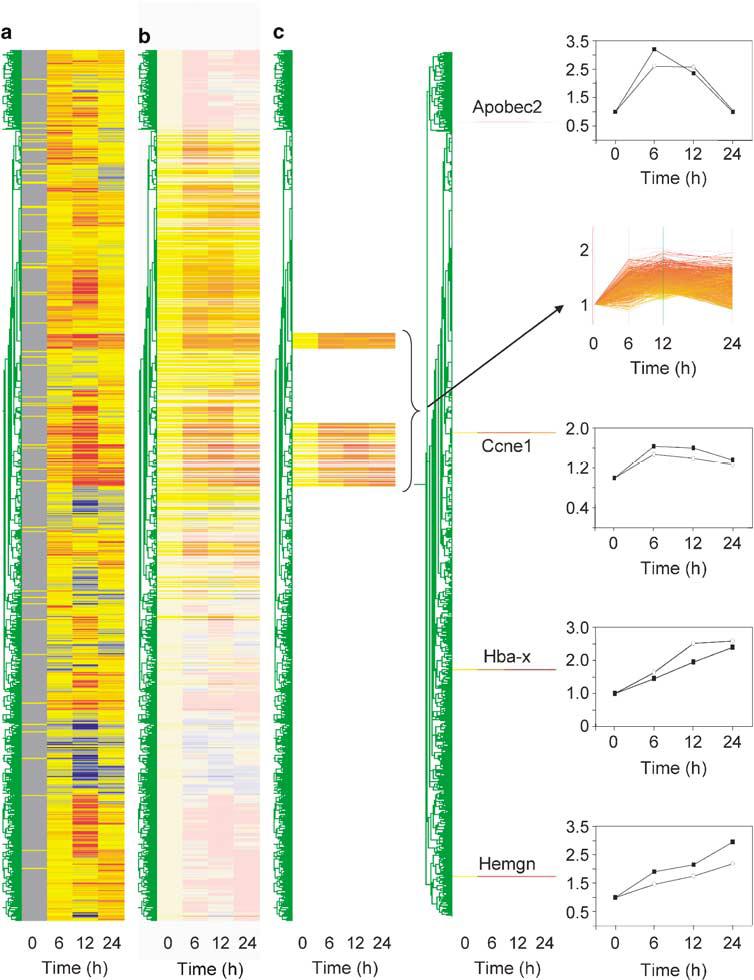

As described in the accompanying Supplementary Information, iEBHX1S-4 cells exhibit a proerythroblast-like phenotype and require interleukin-3 plus stem cell factor for survival and proliferation (Supplementary Figure 1). Downregulation of TLX1 expression releases the iEBHX1S-4 differentiation block, allowing erythropoietin-dependent acquisition of erythroid markers and hemoglobin synthesis (Supplementary Figure 2). Global gene expression profiles were determined by microarray profiling for iEBHXIS-4 cells at 0, 6, 12 and 24 h following doxycycline withdrawal. TLX1 protein levels progressively decreased with a half-life of ∼6h, approaching basal levels that were below detection by Western blot analysis by 24 h (Supplementary Figure 2g; see Figure 2a). Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the expression data created a condition tree that showed corresponding progressive changes in the iEBHX1S-4 transcriptome during the 24 h time course experiment (Figure 1a and b). Gene tree clustering revealed two major subtrees of genes whose transcript levels increased from 0 to 24 h (Figure 1c), which displayed nonrandom overlap (P = 0.011) with a subset of genes induced upon restoration of GATA-1 activity during differentiation of ESC-derived GATA-1-null G1E erythroid cells (NCBI GEO Accession Number GDS568). We employed quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to validate the expression pattern of a representative example from this set, Ccne1 (cyclin E1), and selected examples of other induced genes that demonstrated different kinetics of upregulation, that is Hba-x (ζ-globin), Hemgn (hemogen) (Yang et al., 2001) and Apobec2 (Kostic and Shaw, 2000). The corresponding expression profiles for these genes are illustrated in Figure 1c.

Figure 2.

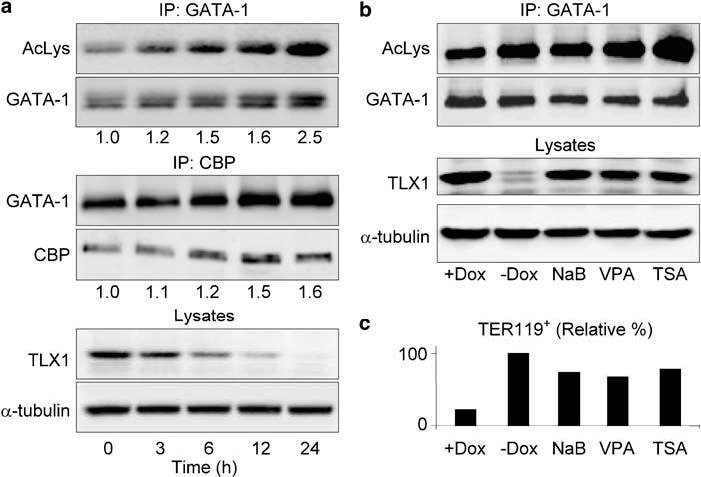

CBP interaction with GATA-1 in differentiating iEBHX1S-4 cells. (a) Change in GATA-1 acetylation and protein levels upon TLX1 downregulation. The two top panels show Western blotting of anti-GATA-1 immunoprecipitates with anti-acetylated lysine or anti-GATA-1 antibodies. The ratios of acetylated GATA-1 to total GATA-1 are indicated. The two middle panels show Western blotting of anti-CBP immunoprecipitates with anti-GATA-1 or anti-CBP antibodies. The relative increase in CBP-associated GATA-1 levels is indicated. The two bottom panels show the corresponding decrease in total TLX1 protein levels and an α-tubulin loading control. (b) Changes in GATA-1 acetylation following Dox withdrawal or treatment with HDAC inhibitors. The two top panels show Western blotting of anti-GATA-1 immunoprecipitates with anti-acetylated lysine or anti-GATA-1 antibodies. The two bottom panels show the corresponding TLX1 protein levels and an α-tubulin loading control. +Dox indicates untreated iEBHX1S-4 cells cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml doxycycline; -Dox indicates cells grown without doxycycline for 24 h. Cells were treated with the indicated HDAC inhibitors for 24 h. Abbreviations: NaB, 1 mM sodium butyrate; VPA, 0.5 mM valproic acid; TSA, 50 nM trichostatin A. (c) The graph depicts levels of glycophorin A/TER119 surface antigen expression following doxycycline withdrawal or treatment with HDAC inhibitors. + Dox indicates untreated iEBHX1S-4 cells cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml doxycycline; -Dox indicates cells grown without doxycycline for 3 days. Cells were treated with the indicated HDAC inhibitors for 3 days. HDAC inhibitor abbreviations and concentrations as above. Glycophorin A/TER119 levels 3 days after doxycycline withdrawal were denoted as 100%.

Figure 1.

Overall analysis of the entire set of data showing expression changes in iEBHX1S-4 cells upon TLX1 downregulation. Each microarray data set was normalized to the 50th percentile and then relative to corresponding signal intensities obtained for t = 0h. (a) Condition and gene trees colored for significance. Blue corresponds to -3σ and red to 3σ. (b) Condition and gene trees colored for trust and expression levels. Blue corresponds to 0 and red to 2. Levels of trust increase with brightness. Graphs were generated using GeneSpring. (c) Selected subtrees for genes showing gradual increase during the observation period. Arrow indicates the corresponding expression profiles. Comparison of qRT-PCR (○) and microarray data (■) for selected induced transcripts (Ccne1/cyclin E1, Hba-x/ζ-globin, Hemgn and Apobec2).

To identify putative regulatory hierarchies downstream of TLX1, sets of conditionally regulated genes classified according to the Gene Ontology (GO) term ‘Transcription’ were subjected to bioinformatic promoter analysis. These included 85 gradually induced genes from the combined subtrees shown in Figure 1c (Supplementary Table 1), 46 representatives of the Ccne1-like profile (κ>0.995) (Supplementary Table 2), 42 representatives of the Hba-x-like profile (κ>0.985) (Supplementary Table 3), 31 representatives of the Hemgn-like profile (κ>0.985) (Supplementary Table 4) and 27 representatives of the Apobec2-like profile (κ>0.975) (Supplementary Table 5). For comparison, we included representatives from two subclusters of genes obtained by K-means clustering of the entire data set, whose transcripts were downregulated by 6 (44 representatives; Supplementary Table 6) or 12 h (45 representatives; Supplementary Table 7) following doxycycline withdrawal. A common feature of all of the transcription factors implicated through this analysis-GATA-1, KLF1, NF-Y, C/EBP and SCL-is that their transcriptional activity is regulated by CBP (see Supplementary Information). Given these observations, we hypothesized that TLX1 might impede iEBHX1S-4 differentiation by interfering with CBP.

Impaired acetylation of GATA-1 in TLX1-expressing iEBHX1S-4 erythroid cells

We first determined whether the acetylation levels of GATA-1, an essential target for CBP-facilitated erythroid differentiation (Blobel et al., 1998; Hong et al., 2002), changed in iEBHX1S-4 cells upon release of the TLX1-mediated differentiation block. Indeed, following doxycycline withdrawal, the levels of acetylated GATA-1 increased (∼2.5-fold), whereas the levels of CBP-associated GATA-1 increased (∼1.6-fold) inversely proportional to the decreasing TLX1 protein levels during the 24 h time course experiment (r = -0.90 and -0.93, respectively) (Figure 2a). Transcription factor acetylation levels are the result of a dynamic equilibrium between acetyltransferases and deacetylases (Yang, 2004). In particular, GATA-1 has been demonstrated to associate with class I and class II histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes (Watamoto et al., 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2005). Because it was shown that treatment with the class I/II HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin A, markedly augmented acetylation of GATA-1 in transfected Cos 7 cells (Hernandez-Hernandez et al., 2006), we next investigated whether class I/II HDAC inhibitor treatment would result in increased levels of acetylated GATA-1 in iEBHX1S-4 cells. We found that 24 h treatment of doxycycline-supplemented iEBHX1S-4 cell cultures with three specific class I/II HDAC inhibitors, sodium butyrate, valproic acid and trichostatin A, induced acetylation of GATA-1 comparable to the levels observed upon TLX1 downregulation (Figure 2b). Based on these observations, we were interested in determining whether HDAC inhibitor treatment was sufficient to bypass the TLX1-mediated iEBHX1S-4 differentiation block (Yoshida et al., 1987). Indeed, treatment of iEBHX1S-4 cells cultured in doxycycline-supplemented medium for 3 days with HDAC inhibitors resulted in considerable differentiation as reflected by upregulation of glycophorin A/TER119 expression, a target gene of the SCL-LMO2-GATA-1 complex (Lahlil et al., 2004), with levels approaching that observed during the same period following doxycycline withdrawal (Figure 2c). These findings are consistent with the notion that insufficient GATA-1 acetylation levels are an important aspect of the TLX1-mediated differentiation arrest in iEBHX1S-4 cells.

TLX1 interaction with CBP in iEBHX1S-4 and 293T cells and targeting to heterochromatin

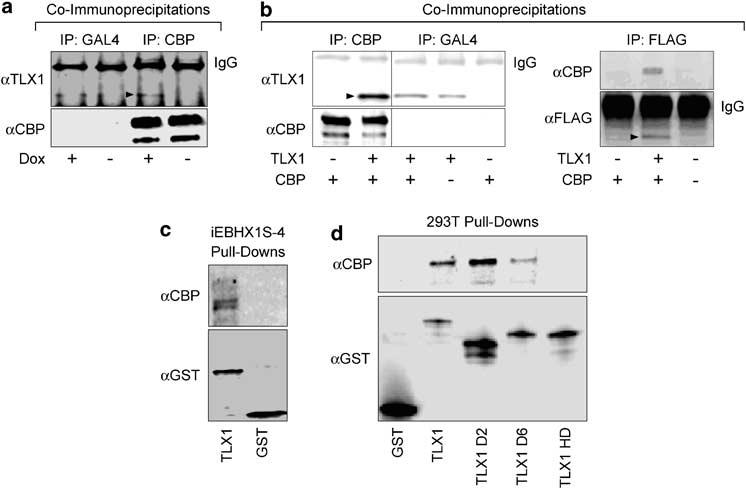

To obtain evidence in support of the possibility that TLX1 might interfere with CBP function in iEBHX1S-4 cells, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments to determine whether TLX1 was capable of physically associating with CBP in vivo. As shown in Figure 3a, TLX1 coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous CBP from iEBHX1S-4 lysates. Coimmunoprecipitation of exogenous TLX1 with exogenous mouse CBP from lysates of human 293T embryonic kidney cells cotransfected with expression vectors encoding TLX1 (Owens et al., 2003; Riz and Hawley, 2005) and mouse CBP (Chrivia et al., 1993; Kwok et al., 1994) was also demonstrated (Figure 3b, left panels). In addition, a monoclonal antibody directed against ectopically expressed FLAG epitope-tagged TLX1 (Owens et al., 2003) was shown to coimmunoprecipitate exogenous human CBP from lysates of 293T cells cotransfected with corresponding expression vectors in separate experiments (Figure 3b, right panels). We extended these studies by performing in vitro pull-down experiments with glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-TLX1 fusion proteins. Both endogenous CBP from iEBHX1S-4lysates (Figure 3c) as well as ectopically expressed mouse CBP from 293T lysates (Figure 3d) bound to immobilized full-length GST-TLX1 fusion protein but not to control GST beads. Moreover, a GST-TLX1 fusion protein missing the homeodomain (TLX1 HD mutant) was incapable of coprecipitating exogenous mouse CBP from 293T lysates, whereas reduced binding was observed with a GST-TLX1 fusion protein containing a 70-amino-acid carboxy-terminal deletion (TLX1 D6 mutant), which truncated the TLX1 protein immediately after the homeodomain (Figure 3d). By comparison, coprecipitation of exogenous mouse CBP from 293T lysates with a GST-TLX1 fusion protein containing a 97-amino-acid amino-terminal deletion (TLX1 D2 mutant) was comparable to that achieved with the fulllength GST-TLX1 fusion protein (Figure 3d). The combined results indicated that: (1) TLX1 is capable of interacting with endogenous and exogenous CBP under in vivo conditions; (2) in vivo TLX1-CBP complex formation did not depend on an erythroid lineage- or stage-specific nuclear structure or on erythroid-specific cofactors; (3) TLX1 directly interacts with CBP in vitro and (4) the homeodomain of TLX1 was required for in vitro interaction with CBP, as was previously demonstrated for a number of clustered HOX proteins (Shen et al., 2001).

Figure 3.

TLX1 interacts with CBP in vivo and in vitro. (a) Nuclear lysates of iEBHX1S-4 cells cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml doxycycline ( + Dox) or grown without doxycycline for 3 days ( -Dox) were immunoprecipitated with anti-CBP or anti-GAL4 (irrelevant control) antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with anti-TLX1 or anti-CBP antibodies. The TLX1 band is indicated by the arrowhead. (b) Left Whole-cell lysates of 293T cells transiently transfected with TLX1 or CBP expression vectors were immunoprecipitated with anti-CBP or anti-GAL4 (irrelevant control) antibodies followed by Western blot analysis with anti-TLX1 or anti-CBP antibodies. Under the conditions used, some nonspecific (background) immunoprecipitation of TLX1 was observed with the anti-GAL4 antibody. Right Whole-cell lysates of 293T cells transiently transfected with TLX1 (FLAG-tagged) or CBP expression vectors were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody followed by Western blot analysis with anti-CBP or anti-FLAG antibodies. TLX1 bands are indicated by the arrowheads. (c) iEBHX1S-4 nuclear lysates were incubated with immobilized GST-TLX1 fusion protein or with control GST beads and the bound proteins eluted and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-CBP and anti-GST antibodies. The amount of eluate loaded to detect the GST-TLX1 fusion protein represents 0.5% of the amount loaded to detect CBP. (d) Nuclear lysates of 293T cells transiently transfected with a CBP expression vector were incubated with immobilized GST-TLX1 fusion proteins or with control GST beads and the bound proteins eluted and subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-CBP and anti-GST antibodies. The amount of each eluate loaded to detect GST-TLX1 fusion proteins represents 5% of the amount loaded to detect CBP. Abbreviations: TLX1, GST-FLAG-TLX1; TLX1 D2, GST-FLAG-TLX1 D2 (consisting of amino acids 98-330), GST-FLAG-TLX1 D6 (consisting of amino acids 2-260) and GST-FLAG-TLX1 HD (containing an internal deletion from amino acid 201 to amino acid 260).

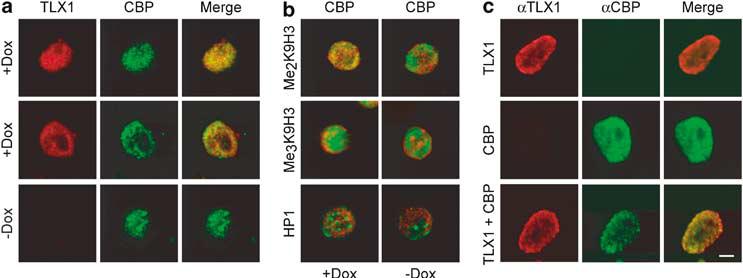

We next investigated the intracellular distribution of TLX1 and CBP. iEBHX1S-4 cells grown in the presence or absence of doxycycline were fixed, immunolabeled with anti-TLX1 and/or anti-CBP antibodies, and examined by immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser scanning microscopy. As expected from previous findings (Chrivia et al., 1993; Dear et al., 1993; Owens et al., 2003), TLX1 and CBP localized selectively within the nucleus. In the presence of doxycycline, significant colocalization of the two proteins was observed (Figure 4a, + Dox Merge). Because a recent publication reported that a proportion of TLX1 in human T-ALL cells unexpectedly localizes to heterochromatin domains (Heidari et al., 2006), we were interested in examining whether TLX1 inhibition of CBP might result from the ‘intranuclear marshaling’ of CBP to heterochromatic regions (Schaufele et al., 2001). Therefore, we next determined the intranuclear distribution of CBP in conditionally arrested iEBHX1S-4 cells with respect to heterochromatin markers. Lysine 9 methylation of histone H3 (K9H3) is an epigenetic modification that has been correlated with both local and global repression of transcription, and a number of studies have suggested that the di- (Me2K9H3) and trimethylation (Me3K9H3) states of K9H3 largely reside in separate subnuclear compartments, possibly distinguishing facultative and constitutive heterochromatin, respectively (Guenatri et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005). In addition, the α isoform of the non-histone adapter heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1α) is frequently concentrated at Me3K9H3-enriched heterochromatin (Guenatri et al., 2004). In this regard, it was notable that costaining of iEBHX1S-4 cells grown in the presence of doxycycline with anti-CBP and anti-Me2K9H3 antibodies revealed partially overlapping regions of fluorescence (Figure 4b, +Dox). In contrast, no overlap of CBP and Me2K9H3 fluorescence was observed 18 h following doxycycline withdrawal (Figure 4b, -Dox), indicating exit of CBP from this subnuclear compartment concomitant with TLX1 downregulation. By comparison, no overlap of the CBP distribution pattern with Me3K9H3 or with HP1α was revealed by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of iEBHX1S-4 cells similarly cultured in the presence or absence of doxycycline (Figure 4b). These results suggested that TLX1 might inhibit CBP function in iEBHX1S-4 cells by sequestering a sub-population of the protein in particular subnuclear compartments, including those associated with heterochromatin domains enriched in Me2K9H3.

Figure 4.

Partial colocalization of TLX1 and CBP in iEBHX1S-4 and 293T cells. (a) iEBHX1S-4 cells cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml doxycycline ( + Dox) or grown without doxycycline for 18 h ( -Dox) were labeled with anti-TLX1 (TLX1; Alexa Fluor 568, red) and anti-CBP (CBP; Alexa Fluor 488, green) antibodies and immunofluorescence staining was analysed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. The right panels show the merged green and red images at the same focal plane with overlapping regions of protein distribution appearing yellow. (b) iEBHX1S-4 cells cultured in the presence of 1 μg/ml doxycycline (+Dox) or grown without doxycycline for 18 h ( -Dox) were labeled with anti-CBP (CBP; Alexa Fluor 488, green) and either anti-dimethyl-histone H3 (Lys9) (Me2K9H3; Alexa Fluor 568, red) or anti-trimethyl-histone H3 (Lys9) (Me3K9H3; Alexa Fluor 568, red) antibodies, or with anti-CBP (CBP; Alexa Fluor 568, red) and anti-HP1α (HP1; Alexa Fluor 488, green) antibodies and immunofluorescence staining was analysed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. The panels shown are the merged green and red images at the same focal plane. Overlapping distributions of CBP and dimethyl-histone H3 (Lys9) staining in + Dox cultures of iEBHX1S-4 cells appear yellow. (c) 293T cells transiently transfected with TLX1 and/or CBP expression vectors (indicated to the left of the panels) were labeled with anti-TLX1 (αTLX1; Alexa Fluor 568, red) and anti-CBP (αCBP; Alexa Fluor 488, green) antibodies, and immunofluorescence staining was analysed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. The right panels show the merged green and red images at the same focal plane with overlapping regions of protein distribution appearing yellow. Note that coexpression of TLX1 caused redistribution of a substantial fraction of CBP to the nuclear periphery (see Supplementary Figure 3 for details). Size bar, 10 μm.

In light of these observations, we were interested in directly studying the effect of TLX1 expression on the intranuclear distribution of CBP. Therefore, we transiently transfected 293T cells with the FLAG-tagged TLX1 and/or mouse CBP expression vectors and examined their intranuclear locations by immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser scanning microscopy (Figure 4c; Supplementary Figure 3). Under these experimental conditions, TLX1 was preferentially located at the nuclear periphery, whereas in the absence of TLX1, CBP was distributed throughout the nucleus. Quantitative image analysis (Supplementary Figure 3) revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between the distribution of TLX1 in the peripheral versus the central region of the nucleus (P = 0.024) but not in the case of CBP (P = 0.328, peripheral versus central localization). However, when TLX1 was coexpressed with CBP, a substantial fraction of CBP exhibited a striking redistribution to the nuclear periphery (P = 0.001, peripheral versus central localization), colocalizing with TLX1 (Pearson correlation coefficient, r = 0.672). These results provided direct evidence for the recruitment of CBP to subnuclear compartments occupied by coexpressed TLX1.

Discussion

We inferred from previous work in various murine model systems that TLX1 functions in human leukemia etiology at least in part by disrupting hematopoietic differentiation programs (Hawley et al., 1994, 1997; Keller et al., 1998; Owens et al., 2003, 2006). The collective observations thus raised the possibility that TLX1 might interfere with hematopoietic differentiation pathways by interacting with shared signaling components or transcriptional coregulators. To gain a better understanding of the underlying mechanism of the TLX1-mediated differentiation block, we generated the factor-dependent iEBHX1S-4 progenitor cell line by conditional immortalization with doxycycline-inducible TLX1 expression. We then performed genome-wide expression profiling of iEBHX1S-4 cells released from the differentiation block at early time points following doxycycline withdrawal. A key feature of our experimental design was the bioinformatic analysis of functionally related sets of genes exhibiting similar expression profiles following TLX1 extinction. This analysis revealed coordinated upregulation of erythroid transcriptional networks integrated by the acetyltransferase co-activator CBP. Among erythroid-lineage transcription factor targets of CBP, previous work had highlighted CBP acetylation of GATA-1 as being essential for erythroid differentiation (Blobel et al., 1998; Hung et al., 1999; Hong et al., 2002). Accordingly, we found immediate increases in the levels of CBP-associated GATA-1 as well as the acetylated form of GATA-1 upon TLX1 downregulation, whereas class I/II HDAC inhibitor treatment of conditionally arrested iEBHX1S-4 cells stimulated GATA-1 acetylation and differentiation (Yoshida et al., 1987; Watamoto et al., 2003). We subsequently demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation experiments and GST pull-down assays that TLX1 binds to CBP in vivo and in vitro, and we provided evidence that the homeodomain of TLX1 is required for its direct interaction with CBP in vitro. We also showed by confocal laser microscopy that CBP partially colocalizes with TLX1 and Me2K9H3-marked heterochromatin in iEBHX1S-4 cells, relocating from these heterochromatic regions concomitant with TLX1 downregulation. Further, we documented that coexpression of TLX1 with CBP in a heterologous cell line (293T cells) resulted in the redistribution of its intranuclear location. The combined results presented here can therefore be interpreted to suggest a mechanism by which TLX1 modulates CBP function by binding and recruiting it to particular subnuclear compartments, including those organized into repressive chromatin domains (Schaufele et al., 2001; Heidari et al., 2006).

Transforming viral proteins such as adenovirus E1A, which force cells into S phase, target CBP as well as the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein (Blobel, 2000; Helt and Galloway, 2003). We previously showed that TLX1 regulated multiple G1/S transcriptional networks in TLX1+ human T-ALL cell lines by inhibiting Rb function (Riz and Hawley, 2005). Whereas it is clear that the adenovirus E1A oncoprotein represses Rb activity, opposing effects of E1A on CBP activity have been reported (Ait-Si-Ali et al., 2000). Notably, although E1A interferes with CBP-mediated acetylation of GATA-1 (Blobel et al., 1998; Hung et al., 1999), E1A modulates expression of certain cell cycle-related genes such as the proliferating cell nuclear antigen in part by disrupting CBP interaction with other transcriptional regulators (Karuppayil et al., 1998). Thus, the current findings leave open the possibility that TLX1 may also redirect as well as inhibit CBP-facilitated differentiation signals, converting them into proliferative responses.

CBP and the closely related p300 protein function as global coregulators of transcription, purportedly interacting physically or functionally with over 300 proteins (Kasper et al., 2006). It is not surprising therefore that many developmental pathways culminate in interactions that involve CBP. In particular, a full complement of CBP is required for normal differentiation along multiple hematopoietic lineages (Kung et al., 2000; Kasper et al., 2006). The current studies using the novel iEBHX1S-4 erythroid progenitor cell model suggest that the mechanism by which TLX1 contributes to erythroid differentiation arrest occurs in a manner analogous to that for several other oncoproteins (Blobel et al., 1998; Hung et al., 1999; Hong et al., 2002). In this regard, it is worth noting that subversion of erythroid transcriptional networks is observed in human T-ALL cases in connection with the SCL and LMO2 transcription factors, which normally form a DNA-binding complex containing GATA-1 in erythroid cells (Wadman et al., 1997). Similar to TLX1 (Owens et al., 2006), enforced expression of SCL or LMO2 in thymocyte precursors causes deregulation of the transition check-point from the CD4- CD8- double-negative to CD4+ CD8+ double-positive stages of T-cell development (Larson et al., 1995; Herblot et al., 2000), a consequence mimicked by attenuating CBP activity during thymocyte development (Kasper et al., 2006). In the case of SCL, both activator and repressor functions have been ascribed to multiprotein complexes, exerted through SCL association with CBP and other protein partners (Huang et al., 1999; Schuh et al., 2005). Of further interest is the recent observation that SCL associates with heterochromatin domains and mediates regional transcriptional repression by a chromatin remodeling mechanism that is sensitive to the class I/II HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (Wen et al., 2005).

Modulation of CBP function in the context of differentiation arrest is also a recurring theme in human acute myeloid leukemia, with chromosomal translocations frequently targeting CBP directly or the resulting fusion proteins - for example, MOZ-TIF2, AML1-ETO - shown to interact with CBP (Deguchi et al., 2003; Iyer et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2006). It is noteworthy, for example, that interaction with CBP is necessary for immortalization of murine myeloid progenitors by the MOZ-TIF2 oncoprotein (Deguchi et al., 2003). Interaction with CBP has also been proposed to play a role in the immortalization of murine myeloid progenitors by the E2A-PBX1 fusion oncoprotein of human pre-B-cell ALL (Kamps and Wright, 1994; Bayly et al., 2004). Of particular relevance to the current study is the demonstration that the differentiation of certain murine myeloid progenitor cell lines conditionally immortalized by E2A-PBX1 could be arrested by ectopic expression of a variety of oncogenes, including AML1-ETO, HOXA7 and HOXA9 as well as other HOX genes (Sykes and Kamps, 2001). The accumulated data, considered together with previous observations that many HOX proteins were found to interact with CBP, commonly via the homeodomain (Shen et al., 2001), suggest a shared indirect mechanism of hematopoietic cell differentiation arrest mediated by these homeodomain-containing transcription factors. In view of the recent appreciationof deregulated HOXA homeobox gene expression in human T-ALL and the finding that HOXA-translocated samples could be grouped together with TLX1+ cases based on genome-wide expression analysis (Soulier et al., 2005), it is tempting to speculate that modulation of CBP function may contribute to T-ALL evoked by the TLX1 and HOXA homeodomain proteins (Kang-Decker et al., 2004).

Materials and methods

iEBHX1S-4 erythroid progenitor cell line derivation

The ploxTLX1 targeting plasmid was electroporated into the doxycycline-inducible ESC line Ainv15 and selected for G418 resistance as described (Kyba et al., 2002). Embryoid body formation, and iEBHX1S-4 progenitor cell line derivation and characterization were essentially as described (Keller et al., 1998; Kyba et al., 2002). See Supplementary Information for details.

Microarray profiling

Microarray profiling was performed in The George Washington University Medical Center Genomics Core Facility essentially as described previously (Krasnoselskaya-Riz et al., 2002; Riz and Hawley, 2005). The expression profiles of selected genes obtained by microarray analysis were validated by real-time qRT-PCR using TaqMan probe sets (Applied Biosciences, Branchburg, NJ, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Details of bioinformatic analysis are provided in Supplementary Information.

Immunoprecipitations, GST pull-downs and Western blotting

Immunoprecipitations, GST pull-downs and Western blotting were performed essentially as described previously (Berger and Hawley, 1997; Owens et al., 2003; Akimov et al., 2005; Riz and Hawley, 2005).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy and image analysis

Confocal images were acquired using the × 60 oil immersion objective of a Bio-Rad MRC-1024 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with an argon-krypton ion laser and LaserSharp 2000 software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA) and were analysed using Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA) as described previously (Popratiloff et al., 2003) as detailed in Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).

References

- Ait-Si-Ali S, Polesskaya A, Filleur S, Ferreira R, Duquet A, Robin P, et al. CBP/p300 histone acetyl-transferase activity is important for the G1/S trasnsition. Oncogene. 2000;19:2430–2437. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimov SS, Ramezani A, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Bypass of senescence, immortalization, and transformation of human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1423–1433. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, Zhu Y-X, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. TALE homeoproteins as HOX11-interacting partners in T-cell leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39:241–256. doi: 10.3109/10428190009065824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly R, Chuen L, Currie RA, Hyndman BD, Casselman R, Blobel GA, et al. E2A-PBX1 interacts directly with the KIX domain of CBP/p300 in the induction of proliferation in primary hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55362–55371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger LC, Hawley RG. Interferon-β interrupts interleukin-6-dependent signaling events in myeloma cells. Blood. 1997;89:261–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel GA. CREB-binding protein and p300: molecular integrators of hematopoietic transcription. Blood. 2000;95:745–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel GA, Nakajima T, Eckner R, Montminy M, Orkin SH. CREB-binding protein cooperates with transcription factor GATA-1 and is required for erythroid differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2061–2066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Elagib KE, Delehanty LL, Goldfarb AN. Erythroid inhibition by the leukemic fusion AML1-ETO is associated with impaired acetylation of the major erythroid transcription factor GATA-1. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2990–2996. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature. 1993;365:855–859. doi: 10.1038/365855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dear TN, Sanchez-Garcia I, Rabbitts TH. The HOX11 gene encodes a DNA-binding nuclear transcription factor belonging to a distinct family of homeobox genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4431–4435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deguchi K, Ayton PM, Carapeti M, Kutok JL, Snyder CS, Williams IR, et al. MOZ-TIF2-induced acute myeloid leukemia requires the MOZ nucleosome binding motif and TIF2-mediated recruitment of CBP. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:259–271. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene WK, Bahn S, Masson N, Rabbitts TH. The T-cell oncogenic protein HOX11 activates Aldh1 expression in NIH 3T3 cells but represses its expression in mouse spleen development. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7030–7037. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenatri M, Bailly D, Maison C, Almouzni G. Mouse centric and pericentric satellite repeats form distinct functional heterochromatin. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:493–505. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley RG, Fong AZC, Lu M, Hawley TS. The HOX11 homeobox-containing gene of human leukemia immortalizes murine hematopoietic precursors. Oncogene. 1994;9:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley RG, Fong AZC, Reis MD, Zhang N, Lu M, Hawley TS. Transforming function of the HOX11/ TCL3 homeobox gene. Cancer Res. 1997;57:337–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari M, Rice KL, Phillips JK, Kees UR, Greene WK. The nuclear oncoprotein TLX1/HOX11 associates with pericentromeric satellite 2 DNA in leukemic T-cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:304–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helt AM, Galloway DA. Mechanisms by which DNA tumor virus oncoproteins target the Rb family of pocket proteins. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:159–169. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herblot S, Steff AM, Hugo P, Aplan PD, Hoang T. SCL and LMO1 alter thymocyte differentiation: inhibition of E2A-HEB function and pre-Tα chain expression. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:138–144. doi: 10.1038/77819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Hernandez A, Ray P, Litos G, Ciro M, Ottolenghi S, Beug H, et al. Acetylation and MAPK phosphorylation cooperate to regulate the degradation of active GATA-1. EMBO J. 2006;25:3264–3274. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong W, Kim AY, Ky S, Rakowski C, Seo SB, Chakravarti D, et al. Inhibition of CBP-mediated protein acetylation by the Ets family oncoprotein PU 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3729–3743. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.11.3729-3743.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Qiu Y, Stein RW, Brandt SJ. p300 functions as a transcriptional coactivator for the TAL1/SCL oncoprotein. Oncogene. 1999;18:4958–4967. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung HL, Lau J, Kim AY, Weiss MJ, Blobel GA. CREB-binding protein acetylates hematopoietic transcription factor GATA-1 at functionally important sites. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3496–3505. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer NG, Ozdag H, Caldas C. p300/CBP and cancer. Oncogene. 2004;23:4225–4231. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamps MP, Wright DD. Oncoprotein E2A-Pbx1 immortalizes a myeloid progenitor in primary marrow cultures without abrogating its factor-dependence. Oncogene. 1994;9:3159–3166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang-Decker N, Tong C, Boussouar F, Baker DJ, Xu W, Leontovich AA, et al. Loss of CBP causes T cell lymphomagenesis in synergy with p27Kip1 insufficiency. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppayil SM, Moran E, Das GM. Differential regulation of p53-dependent and -independent proliferating cell nuclear antigen gene transcription by 12 S E1A oncoprotein requires CBP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17303–17306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper LH, Fukuyama T, Biesen MA, Boussouar F, Tong C, de Pauw A, et al. Conditional knockout mice reveal distinct functions for the global transcriptional coactivators CBP and p300 in T-cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:789–809. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.789-809.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe T, Muslin AJ, Korsmeyer SJ. HOX11 interacts with protein phosphatases PP2A and PP1 and disrupts a G2/M cell-cycle checkpoint. Nature. 1997;385:454–458. doi: 10.1038/385454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G, Wall C, Fong AZC, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Overexpression of HOX11 leads to the immortalization of embryonic precursors with both primitive and definitive hematopoietic potential. Blood. 1998;92:877–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostic C, Shaw PH. Isolation and characterization of sixteen novel p53 response genes. Oncogene. 2000;19:3978–3987. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnoselskaya-Riz I, Spruill A, Chen YW, Schuster D, Teslovich T, Baker C, et al. Nuclear factor 90 mediates activation of the cellular antiviral expression cascade. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:591–604. doi: 10.1089/088922202753747941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung AL, Rebel VI, Bronson RT, Ch’ng LE, Sieff CA, Livingston DM, et al. Gene dose-dependent control of hematopoiesis and hematologic tumor suppression by CBP. Genes Dev. 2000;14:272–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok RP, Lundblad JR, Chrivia JC, Richards JP, Bachinger HP, Brennan RG, et al. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature. 1994;370:223–226. doi: 10.1038/370223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyba M, Perlingeiro RCR, Daley GQ. HoxB4 confers definitive lymphoid-myeloid engraftment potential on embryonic stem cell and yolk sac hematopoietic precursors. Cell. 2002;109:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahlil R, Lecuyer E, Herblot S, Hoang T. SCL assembles a multifactorial complex that determines glycophorin A expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1439–1452. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.4.1439-1452.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RC, Osada H, Larson TA, Lavenir I, Rabbitts TH. The oncogenic LIM protein Rbtn2 causes thymic developmental aberrations that precede malignancy in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1995;11:853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens BM, Hawley RG. HOX and non-HOX homeobox genes in leukemic hematopoiesis. Stem Cells. 2002;20:364–379. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-5-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens BM, Hawley TS, Spain LM, Kerkel KA, Hawley RG. TLX1/HOX11-mediated disruption of primary thymocyte differentiation prior to the CD4+CD8+ double-positive stage. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:216–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens BM, Zhu YX, Suen TC, Wang PX, Greenblatt JF, Goss PE, et al. Specific homeodomain-DNA interactions are required for HOX11-mediated transformation. Blood. 2003;101:4966–4974. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popratiloff A, Giaume C, Peusner KD. Developmental change in expression and subcellular localization of two shaker-related potassium channel proteins (Kv1.1 and Kv1.2) in the chick tangential vestibular nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461:466–482. doi: 10.1002/cne.10702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riz I, Hawley RG. G1/S transcriptional networks modulated by the HOX11/TLX1 oncogene of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogene. 2005;24:5561–5575. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez P, Bonte E, Krijgsveld J, Kolodziej KE, Guyot B, Heck AJ, et al. GATA-1 forms distinct activating and repressive complexes in erythroid cells. EMBO J. 2005;24:2354–2366. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufele F, Enwright JF, III, Wang X, Teoh C, Srihari R, Erickson R, et al. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α assembles essential cooperating factors in common subnuclear domains. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1665–1676. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.10.0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh AH, Tipping AJ, Clark AJ, Hamlett I, Guyot B, Iborra FJ, et al. ETO-2 associates with SCL in erythroid cells and megakaryocytes and provides repressor functions in erythropoiesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10235–10250. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10235-10250.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen WF, Krishnan K, Lawrence HJ, Largman C. The HOX homeodomain proteins block CBP histone acetyltransferase activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7509–7522. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7509-7522.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulier J, Clappier E, Cayuela JM, Regnault A, Garcia-Peydro M, Dombret H, et al. HOXA genes are included in genetic and biologic networks defining human acute T-cell leukemia (T-ALL) Blood. 2005;106:274–286. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes DB, Kamps MP. Estrogen-dependent E2a/Pbx1 myeloid cell lines exhibit conditional differentiation that can be arrested by other leukemic oncoproteins. Blood. 2001;98:2308–2318. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadman IA, Osada H, Grutz GG, Agulnick AD, Westphal H, Forster A, et al. The LIM-only protein Lmo2 is a bridging molecule assembling an erythroid, DNA-binding complex which includes the TAL1, E47, GATA-1 and Ldb1/ NLI proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16:3145–3157. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watamoto K, Towatari M, Ozawa Y, Miyata Y, Okamoto M, Abe A, et al. Altered interaction of HDAC5 with GATA-1 during MEL cell differentiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:9176–9184. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Huang S, Pack SD, Yu X, Brandt SJ, Noguchi CT. Tal1/SCL binding to pericentromeric DNA represses transcription. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12956–12966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R, Terry AV, Singh PB, Gilbert DM. Differential subnuclear localization and replication timing of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation states. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:2872–2881. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LV, Nicholson RH, Kaplan J, Galy A, Li L. Hemogen is a novel nuclear factor specifically expressed in mouse hematopoietic development and its human homologue EDAG maps to chromosome 9q22, a region containing breakpoints of hematological neoplasms. Mech Dev. 2001;104:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ. Lysine acetylation and the bromodomain: a new partnership for signaling. BioEssays. 2004;26:1076–1087. doi: 10.1002/bies.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Nomura S, Beppu T. Effects of tricho-statins on differentiation of murine erythroleukemia cells. Cancer Res. 1987;47:3688–3691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Shen W, Hawley RG, Lu M. HOX11 interacts with CTF1 and mediates hematopoietic precursor cell immortalization. Oncogene. 1999;18:2273–2279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc).