Abstract

Mutations at a single locus, PKHD1, are responsible for causing human autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). Recent studies suggest that the cystic disease might result from defects in planar cell polarity but how the 4074 amino acid ciliary protein encoded by the longest open reading frame of this transcriptionally complex gene may regulate this process is unknown. Using novel in vitro expression systems, we show that the PKHD1 gene product polyductin/fibrocystin undergoes a complicated pattern of Notch-like proteolytic processing. Cleavage at a probable proprotein convertase site produces a large extracellular domain that is tethered to the C-terminal stalk by disulfide bridges. This fragment is then shed from the primary cilium by activation of a member of the ADAM metalloproteinase disintegrins family, resulting in concomitant release of an intracellular C-terminal fragment via a γ-secretase-dependent process. The ectodomain of endogenous PD1 is similarly shed from the primary cilium upon activation of sheddases. This is the first known example of this process involving a protein of the primary cilium and suggests a novel mechanism whereby proteins that localize to this structure may function as bi-directional signaling molecules. Regulated release from the primary cilium into the lumen may be a mechanism to distribute signal to down-stream targets using flow.

Keywords: ARPKD, primary Cilia, Notch, Polyductin (PD1), PKHD1

INTRODUCTION

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease is a significant cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality with an estimated incidence of 1 in 20,000 live births (1) (2). The clinical spectrum is widely variable: approximately 30% of affected neonates die shortly after birth, whereas others survive into adulthood(3). In affected neonates, the kidneys are symmetrically enlarged and cysts appear as fusiform dilations of collecting ducts extending radially from the renal pelvis to the cortex(4). Congenital hepatic fibrosis, characterized by increased numbers of interlobular bile ducts and varying degrees of portal fibrosis, is an invariant finding.

Mutations of a single gene on chromosome 6, PKHD1, cause all typical forms of the disease in humans(5) (6) (7) (8). The gene is ~470kb in length and undergoes a complicated pattern of splicing to produce a complex set of transcripts(9) (6). A >12kb mRNA that is comprised of 67 exons encodes the longest open reading frame. The gene is most abundantly expressed in the kidney, though it is expressed in numerous other tissues at a low level. Almost 300 unique mutations have been described, and they have been identified in most of the 67 exons. Genotype-phenotype analyses suggest that the nature of the germline mutations plays an important role in determining clinical outcome. Missense substitutions are more commonly associated with non-lethal presentations whereas chain-terminating mutations are more commonly associated with neonatal death (10) (11) (12). Individuals with two truncating changes universally do not survive beyond the neonatal period.

The expected gene product is a novel 4074 aa single-membrane spanning protein (fibrocystin/polyductin, referred to as PD1 in this paper) that has a lengthy extracellular N-terminal domain made up of multiple TIG/IPT and PbH1 repeats and a short cytoplasmic C-terminus (6) (13). It shares some features with members of the SEMA family of proteins but lacks several key domains of the latter. It is predicted to function either as a receptor, a ligand or possibly both, though there is no direct evidence for either. The gene’s complex splicing profile, in fact, could lead to the generation of products with different domain combinations, which might be associated with distinct affinities or specificities for target ligands/receptors.

Several lines of evidence link PD1 to the function of the primary cilia. A comparative genomic approach identified a distantly-related PKHD1-like gene product as a likely component of the flagella-basal body proteome (FABB) of the single-cell organism, chlamydomonas (14). Masyuk et al reported that the primary cilia of biliary epithelia of pck rats were stunted and have gross morphologic abnormalities (15). Finally, multiple groups have localized PD1 to the primary cilia/basal body (16) (15) (17) (13). The protein may also be present at other domains within the apical membrane and within the cytoplasm.

Despite its clear link to disease, little is known about the function of PD1. It is presumed to have essential developmental functions given the pre-natal and peri-natal disease manifestations that result when it is mutated. Studies of the Pck rat suggest that the protein may play a role in helping to establish planar orientation of developing renal tubules (18). In normal fetal tubules, the mitotic spindle of dividing cells is oriented along the long axis of elongating renal tubules. In the fetal tubules of pre-cystic kidneys of Pck rats, however, mitotic orientations are significantly distorted. How PD1 might help to regulate this process was not determined.

PKHD1 also is expressed in adult tissues, suggesting probable post-developmental functions. In the only published study of the gene’s function, Mai et al used short hairpin RNA inhibition (shRNA) to reduce expression of the murine Pkhd1 orthologue in IMCD cells and found that Pkhd1-silenced cells developed abnormalities in cell-cell contact, actin cytoskeleton organization, cell-ECM interactions, cell proliferation, and apoptosis (19). Their data suggested that these effects might be mediated by dysregulation of extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling. The mechanisms underlying these effects were not defined, however.

In this report, we describe a new PKHD1 in vitro expression system whose features include regulated expression of constructs with N-terminal and C-terminal epitope tags in HEK 293 and MDCK cell lines and show that PD1 undergoes a series of complicated post-translational modifications similar to those described for Notch. We demonstrate that the ectodomain of recombinant PD1 undergoes regulated shedding from the primary cilia and that endogenous PD1 shares similar properties. We propose a novel model by which the shed PD1 ectodomain might help to regulate planar orientation.

RESULTS

Full-length PD1 is a >500kDa protein that undergoes a complicated pattern of proteolytic processing

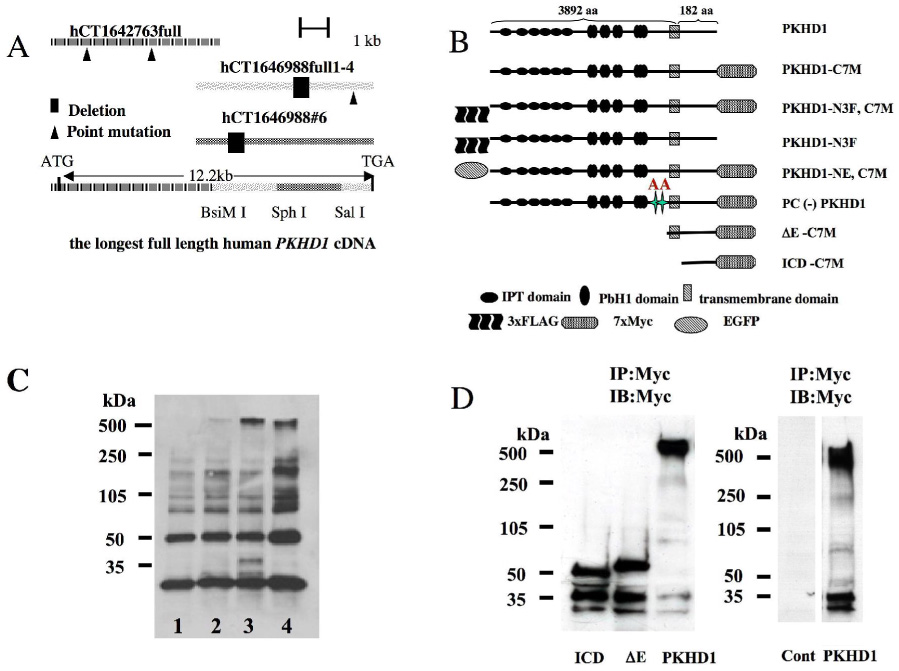

We used high fidelity polymerases to amplify three overlapping fragments that span the 67 exons that encode the longest ORF for human PKHD1 from a human kidney cDNA library. While many of the clones contained a variable assortment of exons, a set was found to include the full coding sequence as previously reported (6). Several point mutations were identified by double strand sequencing and corrected by site-directed mutagenesis. The fragments were then assembled into a single full-length cDNA using unique restriction enzyme sites common to the overlapping segments (Fig.1A). The final product was again sequenced to confirm that all errors had been corrected and cloned into a mammalian expression vector (pCI). FLAG or EGFP tags were added to the amino terminus and 7XMyc tag was added to the C-terminus to allow better detection (Fig. 1B). The expression level of this construct was too low to use practically so we added an additional beta-globin intronic sequence between the promoter and PKHD1 cDNA sequence to enhance protein expression. We verified expression of the full-length PD1 by transient expression in HEK 293 cells and determined that it was >500kDa (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Expression system for recombinant human PD1.

A. Three overlapping fragments (hCT1642763full, hCT1646988full 1–4 and hCT1646988#6) were synthesized by RT-PCR using human kidney RNA as template. Bidirectional sequencing had identified several single base pair differences and small deletions compared to the published sequence (6) (7) that were corrected by site-directed mutagenesis and selective use of sub-fragments. The fragments were assembled to produce a full-length cDNA for the longest predicted PKHD1 ORF using the restriction sites indicated.

B. Schematic representation of the full length (PKHD1-) and truncated (ΔE-, ICD-) PD1 proteins with epitope tags at either their amino (3x FLAG [-N3F], EGFP [-NE]) or carboxyl (7xMyc [-C7M]) termini that are described in this report. All N-terminal tags were placed after the signal peptide sequence. The sizes of the cytoplasmic C-terminal and the extracellular/transmembrane fragments are expressed as the number of amino acid residues (aa).

C. Full length recombinant PD1 is >500kDa in size. Whole cell lysates were prepared from cells transiently transfected with either empty vector (pCI) (lane 1), PKHD1-C7TM with a single intron (lane 2), PKHD1-C7TM with a double intron (lane 3) or Myc-PKD1 (lane 4), and then incubated with anti-Myc antibodies coupled to agarose beads. The affinity-purified products were separated by 4–15% PAGE, immunoblotted and probed with anti-Myc antibodies. A faint band >500kDa that is approximately equal in size to polycystin-1 (lane 4) is seen in lane 2 and in much greater abundance in lane 3 but is not present in the negative control (lane 1). Two smaller novel bands of approximately 37kDa and 30kDa also are seen in lane 3.

D. The C-terminus of PD1 undergoes a complicated pattern of proteolytic processing. Left panel: ICD-C7M (ICD), ΔE-C7M (ΔE) and PKHD1-C7M (PKHD1) were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, affinity purified using anti-Myc beads and then immunoprobed using anti-Myc. Two smaller fragments of ~37kDa and 30kDa were present in each of the three samples in addition to predicted full length products (~50kDa, 65kDa and >500kDa, respectively). The Myc epitope tag is noted to increase the apparent molecular weight of ICD-C7M and ΔE-C7M by ~25kDa. Right panel: Control experiments demonstrating specificity of Myc antibodies. Lysates were prepared from HEK 293 cells transfected with either empty vector (Cont) or PKHD1, subject to affinity enrichment and then immunoprobed using anti-Myc beads and antibodies, respectively. PKHD1-expressing cells yielded the expected pattern while no bands were detected in the control sample.

In immunoprecipitating the full-length product with anti-Myc beads and immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibodies, we identified a set of additional, smaller products present in cells expressing recombinant PD1 but not in control cells (Fig. 1D). These smaller products were thought likely to be proteolytic, C-terminal products derived from the full-length construct. We confirmed this to be the case using two additional PKHD1 constructs, ΔE PD1 and PICD, which lack either just the extracellular domain or everything but the intra-cytoplasmic domain (Fig.1B). These constructs yielded both their expected full-length sizes as well as a similar pattern of shorter fragments <50kDa (Fig. 1D).

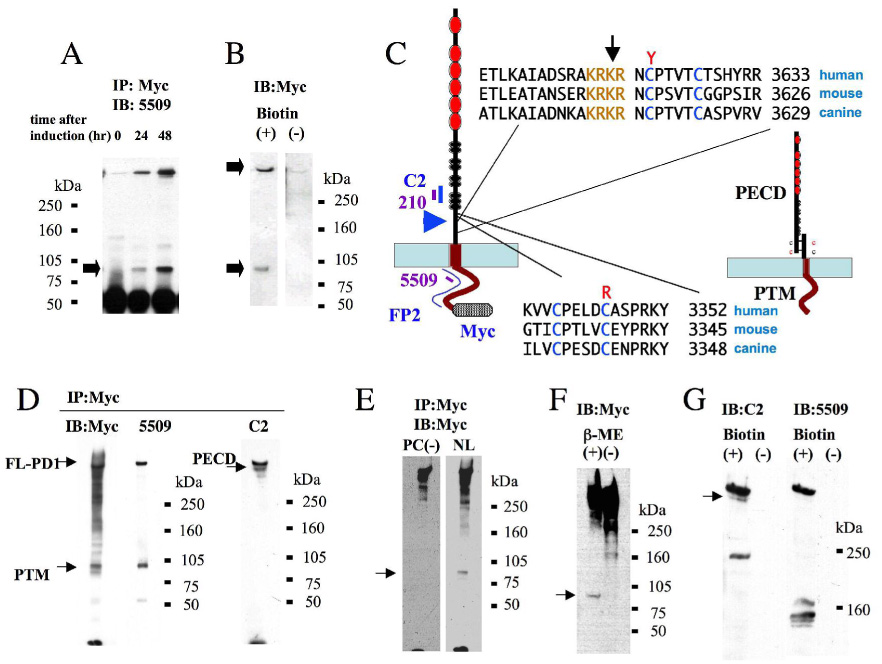

PD1 is cleaved to produce a PD1 extracellular domain (PECD) and a PD1 transmembrane fragment (PTM) which are tethered together by disulfide bonds

To better determine the properties of PD1, we established a set of HEK293 (Human Embryonic Kidney) and MDCK II (Madin Darby Canine Kidney) cell lines with stable, inducible expression of epitope-tagged recombinant full-length PKHD1. In characterizing the cell lines, we identified another PD1-derived, C-terminal product of ~85kDa that appeared ~48h after induction of PKHD1 expression (Fig.2A). Using biotinylation cell-surface labeling studies, we determined that it was located on the cell surface, as was the full-length molecule. These data prompted us to examine the extracellular PD1 amino acid sequence for potential proteolytic sites. Using the Prop1.0 server (www.cbs.dtu.uk/services/ProP), we identified several potential proprotein convertase (PC) cleavage sites that met the consensus sequence ([R/K]-Xn-[R/K] n=0,2,4 or 6) (20) in the human PD1 extracellular domain. However, the site at position 3617–3620 was the most highly conserved in multiple species (human AAM93492, mouse AAN05018 and dog XP_532169) with the highest prediction score in each (0.803 human, 0.705 mouse, 0.872 canine) (Fig.2B).

Figure 2. The PD1 extracellular domain is cleaved at a probable proprotein convertase site and is tethered to the C-terminal stalk.

A. Total cell lysates prepared from HEK293 cells with stable, inducible expression of PKHD1-N3F,C7M at 0, 24 and 48h post induction were incubated with anti-Myc agarose beads and immunoprobed with 5509. Both the full-length product and a shorter, 85kDa product (arrow) were detected 24h post-induction.

B. Cell surface biotinylation assay of PKHD1-expressing cells. Total cell lysates of the same cell line used in A were prepared from cells either incubated with (+) or without (−) biotin prior to cell harvesting, subject to affinity purification using streptavidin-conjugated agarose beads, immunoblotted and then probed with anti-Myc antibodies. Both the full length and 85kDa products were detected in the biotinylated sample (arrows), with minimal background in the non-biotinylated negative control.

C. PD1 has a probable proprotein convertase cleavage (PC) site in its extracellular domain. On the left is a schematic representation of PD1 and the relative position of epitopes recognized by antibodies used in this study (in blue, purple). Immediately adjacent to it is the sequence of a putative proprotein convertase sequence that is highly conserved in vertebrates (light brown). The arrow identifies the position of the predicted cleavage site in the sequence while the blue arrowhead identifies the relative location of the site with respect to the protein’s overall structure. The sequences on the bottom are of the domain likely responsible for tethering the N-terminal cleavage fragment to the C-terminal stalk post-cleavage. The cysteines thought likely to mediate this interaction are colored in blue, while disease-associated missense changes affecting these residues (Y, R) are shown in red. On the far right is a cartoon illustrating the predicted final product that results from PC cleavage, with the extracellular N-terminus (PECD) tethered to the C-terminal stalk (PTM).

D. Immunoprecipitation of PD1 from MDCK cell lines with stable, inducible expression of PD1 using Myc-coupled agarose beads and immunoprobed with the antibodies indicated. Antibodies that recognize epitopes in PTM (Myc, 5509) detect both the full length and 85kDa products while one that recognizes an epitope in the PECD detects both the full length and tethered PECD products. The same blot was used for immunoprobing with Myc and C2.

E. The putative PC cleavage sequence is responsible for the observed cleavage. We generated a set of MDCK cell lines with stable, inducible expression of a mutant form of PD1 in which the PC sequence was mutagenized from KRKR to AAKR [PC(−)]. Total cell lysates were prepared 48h post induction from PC(−) cells expressing mutant PD1 and MDCK cells expressing wild type PD1 (NL), incubated with anti-Myc beads, and then immunoblotted with anti-Myc antibodies. PTM is not present in lysates prepared from the PC(−)-expressing cells (arrow). Because expression levels of mutant PD1 are considerably lower in the PC(−) cell lines than are levels of normal PD1 in NL cell lines, we adjusted exposure times to yield images of approximately equal intensity for this figure.

F. PECD is tethered to PTM by disulfide bonds. Total cell lysate was prepared from MDCK cells induced to express PKHD1-N3F,C7M and then either treated (+) or not treated (−) b-mercaptoethanol prior to PAGE and immunoblotting. The 85kDa PTM fragment is detected by anti-Myc antibodies only under reducing conditions (arrow).

G. PECD is present on the cell surface. Same experimental design as in A except the streptavidin-affinity purified products were probed with C2. The blot was then stripped and re-probed with 5509.

The proprotein convertase family in mammals includes at least eight members, with furin being its most thoroughly investigated member. It is not likely, however, to be the PC responsible for cleavage of PD1 given its substrate specificity preferences. Furin preferentially recognizes sites that contain the sequence motif RX[R/K]R (21) and does not accept lysine (K) residues at the subsequent two positions (22). The PD1 amino acid sequence does not satisfy these requirements. We also experimentally excluded furin as the responsible PC by showing that known furin inhibitors, α1-antitrypsin Portland and decanoyl-RVKR-chloromethylketone (dec-RVKR-cmk), could not inhibit PD1 cleavage (data not shown).

If the putative PC site were active, we would then expect an N-terminal fragment (PECD, Polyductin Extra-Cellular Domain) to remain tethered to the remainder of the molecule (PTM, Polyductin TransMembrane fragment) (Fig.2B). Consistent with this model, we found two cysteines immediately C-terminal to the putative PC sequence and a matching pair equally spaced apart in the N-terminal sequence (Fig.2B). Like the PC site itself, the cysteine pairs also are present in other species. Notably, one of the cysteines was found mutated to arginine and another was mutated to tyrosine in patients with ARPKD (Fig.2B) (23). To confirm our prediction, we immunopurified PD1 using anti-Myc beads and immunoblotted using either anti-Myc antibodies or antibody 5509 raised against a peptide derived from the human PD1 C-terminus. Both antisera recognized identical full length and 85kDa PTM fragments (Fig.2C). Probing the same blot with C2, an antibody raised against a polypeptide derived from the N-terminal domain of PD1, we saw both the full-length and PECD molecules, as predicted (Fig.2C). In contrast, the 85kDa PTM fragment was not detected when the PC site of PD1 was mutagenized by replacing K3167 and R3618 with two alanines (Fig. 1B, Fig. 2D). These data suggest that the PC site is responsible for the observed cleavage.

Our model also predicts that PECD should be tethered to PTM by disulfide bonds. We found this to be the case, as shown in Figure 2E. We detected PTM in cell lysates of cells expressing polyductin that had been treated with β-mercaptoethanol but not in lysates not treated with this reducing agent.

We note that the apparent size of the PTM is larger than predicted based on its primary sequence. This is due, in part, to the 7-Myc tag that was added to the C-terminus. The remainder is due to probable conformation effects that the 7-Myc tag exerts on the protein’s migration in SDS-PAGE gels. This is clearly illustrated by the apparent sizes of the similarly tagged shorter PKHD1 variants ICD-C7M and ΔE-C7M (Fig 1D) that appear ~25kDa larger than their primary sequences would predict. These data, together with the results of the PC site mutagenesis study, strongly suggest that the 85kDa band is the expected PECD product.

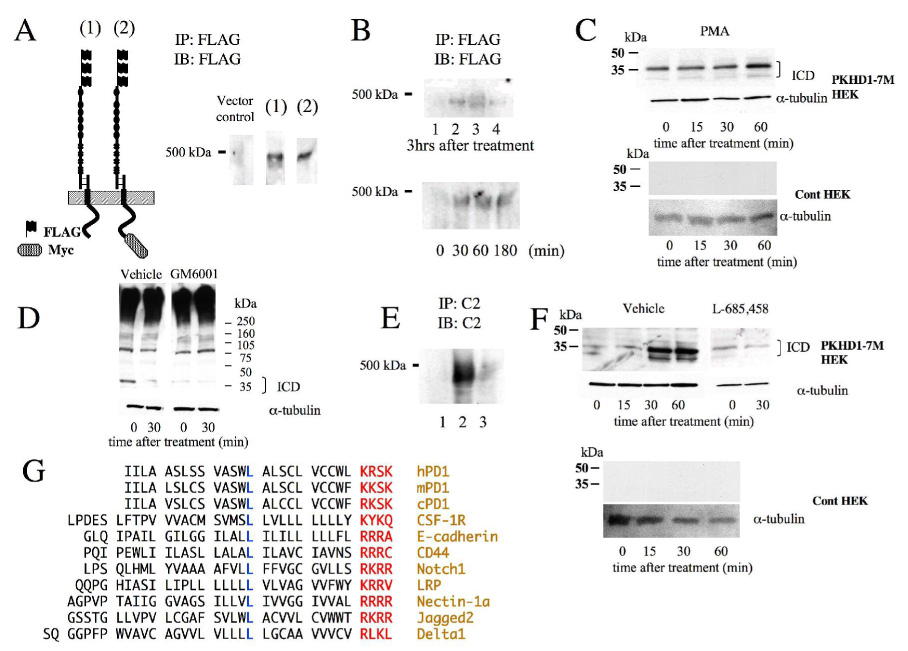

The ectodomain of PD1 undergoes regulated and constitutive shedding

Given that many other molecules that undergo PC processing also undergo regulated ectodomain shedding, we tested for this property for PD1. We transiently expressed two different epitope-tagged PKHD1 constructs in HEK cells, used FLAG-beads to affinity purify secreted product shed into the media, and then immunoprobed the western blot using anti-FLAG antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3A, a similar large product slightly smaller than full-length PD1 was detected in the media in cells expressing each construct. We next examined whether this process is regulated by activation of ADAM metalloproteinase disintegrins as has been reported for other molecules that undergo ectodomain shedding (24). We treated the cells with known activators of ADAM sheddases including pervanadate, the calcium ionophore A23187, 20%FBS and PMA and found that all induced PD1 ectodomain shedding (Fig.3B).

Figure 3. PD1 undergoes both constitutive and regulated ectodomain.

A. Constitutive ectodomain shedding of PD1. N-terminally FLAG-tagged PKHD1 either with (2, PKHD1-N3F,C7M) or without (1, PKHD1-N3F) a C-terminal Myc epitope was transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells. After 48h of induction, tissue culture media was collected and the PD1 ectodomain was immunopurified from the media using FLAG beads. A band slightly lower than 500kDa was detected in the media of cells expressing either construct.

B. Stimulated ectodomain shedding of PD1. TOP: HEK 293 cells with stable, inducible expression of PKHD1 were induced to express PD1 and then placed in fresh tissue culture medium containing various known activators of metalloproteases. The media were collected at the end of three hours and then tested for the presence of PECD. Lane 1: negative control; lane 2: pervanadate (100 µM); lane 3: 20% FBS; lane 4: calcium ionophore (1µM). Bottom: Time course of regulated release of PECD. The same PKHD1+ cell was treated with PMA (100ng/ml), another known activator of metalloproteases, for the times indicated and then the medium collected at each timepoint was tested for PECD.

C. PD1 undergoes stimulated intracellular domain (ICD) cleavage concomitant with its ectodomain shedding. Top: Same cell line used in B was treated with PMA (100ng/ml) for the times indicated and then cell lysates were immunoblotted and probed with anti-Myc. A constitutive 37kDa product increases in abundance upon PMA stimulation. The same blot was probed for α-tubulin to show that approximately equal quantities of lysate were loaded in each lane. Bottom: A vector-transfected control HEK 293 cell line treated in an identical manner as the PKHKD1+ cell line and probed with anti-Myc (top) and anti-tubulin (bottom).

D. Inhibitors of metalloproteases block release of ICD. On the left, lysates of same PKHD1+ cell line used in panels B and C that had been treated for the indicated times with a calcium ionophore and diluent (DMSO, “vehicle”), immunobloted and probed with anti-Myc. On the right, the identical experimental design except the broad metalloprotease inhibitor GM6001 was added to the diluent and calcium ionophore at a final concentration of 50µm for the indicated times. The blots were then re-probed for α-tubulin to confirm equal loading.

E. Inhibitors of metalloproteases block release of PECD. An MDCK cell line with inducible expression of PKHD1-C7M was treated with a calcium ionophore for 30 minutes either with (lane 3) or without (lane 2) GM6001 (150µm final) and then the medium was tested for PECD by immunoprecipitating and immunoblotting with C2. Lane 1 is media from the same cell line without treatment with a calcium ionophore.

F. Top: Same experimental design used in Panel D except the gamma secretase inhibitor L-685,458 was substituted for GM6001 at a final concentration of 5µM. Bottom: Lysates of a HEK 293 vector control cell line treated in an identical manner with a calcium ionophore and vehicle, immunoprobed with anti-Myc and anti-tubulin antibodies.

G. Alignment of transmembrane domains of various known gamma secretase substrates. The stop transfer signal is highlighted in blue and a highly conserved leucine that is positioned 11 residues away is in red. The names of the proteins are listed to the far right in light brown.

PD1 undergoes Regulated Intra-membrane Proteolysis (RIP) with release of intracytoplasmic products (PICD)

A number of proteins that undergo regulated ectodomain shedding have a concomitant cleavage and release of intracellular, cytoplasmic fragments. We tested PD1 for this property in cells treated with two of the compounds found to activate PD1 ectodomain shedding. Using the calcium ionophore A23187 and PMA, we saw a time-dependent increase in cytoplasmic products in response to these treatments (Fig.3C). We also found that a broad metalloprotease inhibitor, GM6001, inhibited this process and reduced release of ICD and shedding of PECD (Fig.3D,E). In many other proteins, the regulated cleavage of the intracellular domain is mediated by γ-secretase. While there is no specific consensus sequence indicating the likely location of a γ-secretase-sensitive site, an alignment of the transmembrane domain sequence of molecules with known γ-secretase substrates reveals a well-conserved leucine 11 residues from the stop-transfer signal that also is present in PD1 (25) (Fig.3G). We therefore tested whether γ-secretase played any role in the proteolysis of PD1 using the inhibitor L-685, 458. While we found that it could not inhibit the constitutive cleavage of intracellular domain of PD1 (data not shown), it did inhibit the release of C-terminal products that are produced in response to treatment with an inducer of ectodomain shedding (calcium ionophore, Fig.3F). These data indicate that the C-terminus of PD1 undergoes both constitutive and regulated cleavage, the latter mediated by γ-secretase.

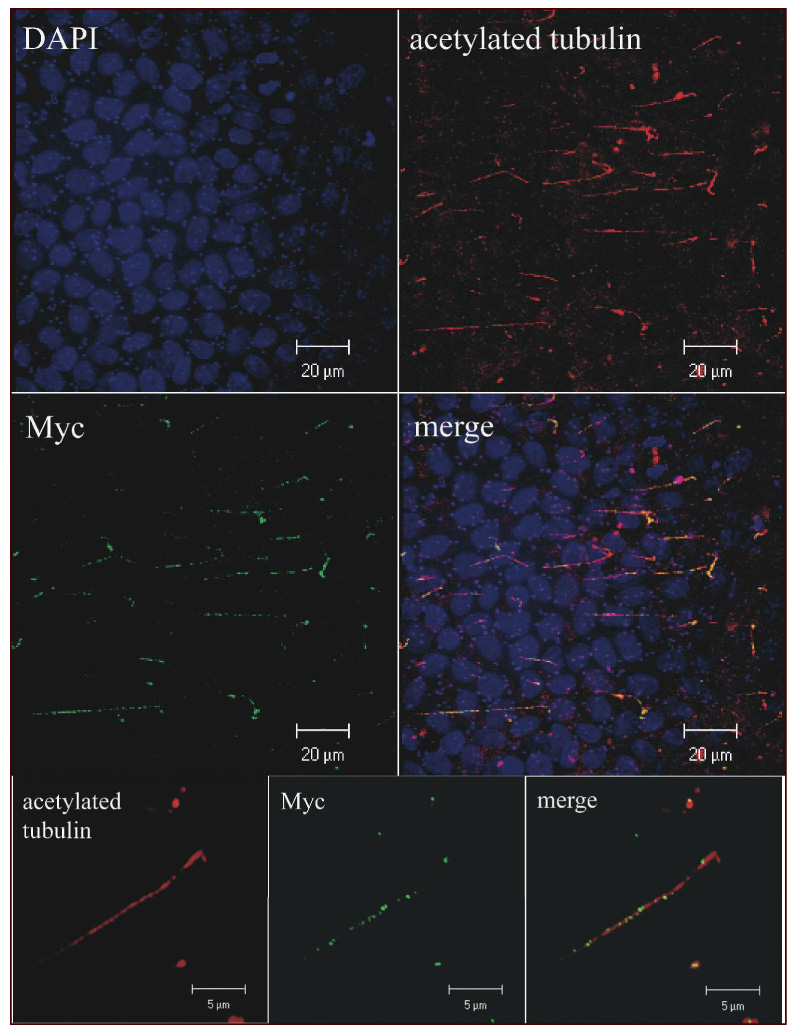

PECD is shed from primary cilia

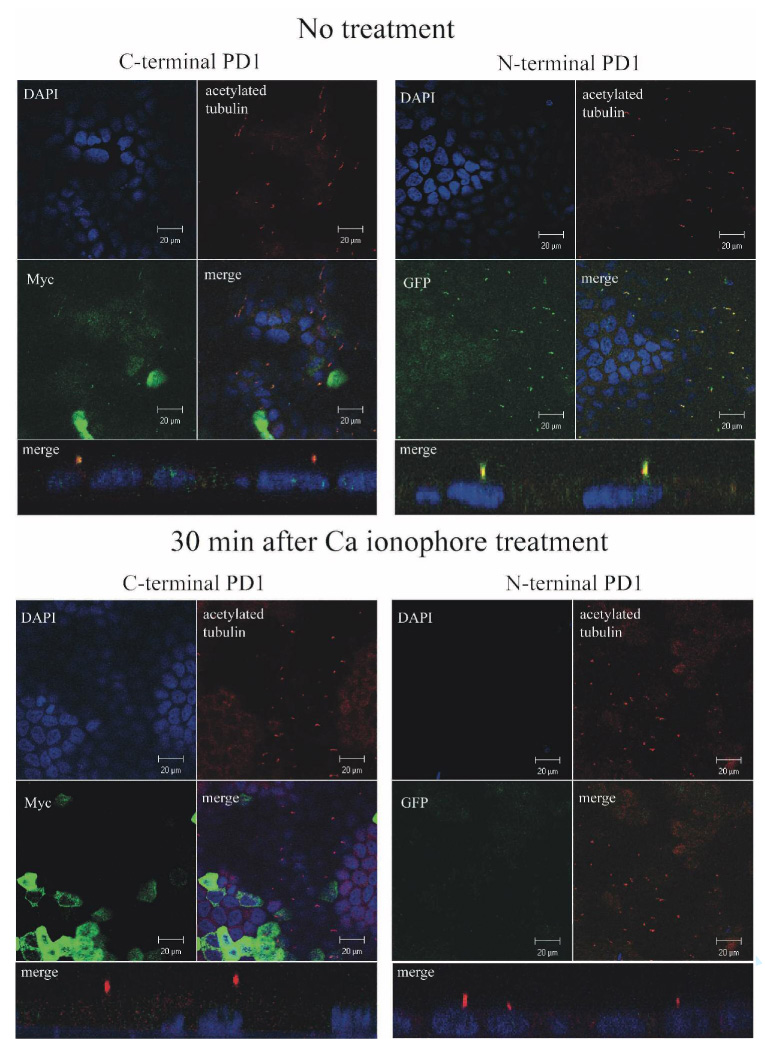

Endogenous PD1 has been previously localized to the primary cilium. We therefore determined whether recombinant PD1 trafficked to the same location in MDCK II cells grown up to 14 days post-confluence on Transwell filters. We added epitope tags to either the C-terminus (7xMyc, PKHD1-C7M) or both the N- and C-termini (EGFP and 7xMyc, PKHD1-NE,C7M) so that we could distinguish between signal from recombinant and endogenous proteins and used these constructs to generate stable cell lines with inducible expression (Fig 1B). Flp-In-MDCKII cells transfected with empty vector and cultured in an identical manner to the PKHD1+ cells were used as a negative control. While we had sought to track expression using EGFP-fluorescence, signal intensity was too low to be used practically. Therefore, co-localization studies were performed using antibodies that recognize EGFP or Myc with antibodies to acetylated tubulin, a marker for primary cilium. As shown in Figure 4, acetylated tubulin colocalized with PD1 in the PKHD1+ cell lines, though PD1 had a speckled distribution pattern as has been previously described for other ciliary proteins that undergo intra-flagellar trafficking (26) (27) (Supplement Movie#1). We next tested how activators of ectodomain shedding affected the sub-cellular distribution pattern of PD1. Cells were cultured to post-confluence on Transwells, treated with a calcium ionophore, and then stained with anti-EGFP and anti-Myc antibodies at various times post-treatment (Fig. 5). Within 30 minutes of activation, the majority of cilia lacked staining for both EGFP and C-terminal Myc tag but remained positive for acetylated tubulin. Cilia also retained staining for Vangl2, another ciliary protein, excluding nonspecific effects of our interventions on intra-flagellar transport as a trivial explanation for our findings (Supplement Fig. 1) (28).

Figure 4. Recombinant PD1 localizes to the primary cilium.

3D reconstruction of confocal images projected in the X-Y plane of MDCK cells expressing PKHD1-C7M cultured for 14 days post-confluence on Transwell filters, fixed, permeabilized and then immunostained for acetylated tubulin and Myc. The top four panels were imaged at 100X while the bottom three insets were viewed at 400X (Supplementary Movie#1).

Figure 5. Recombinant PD1 is shed from the primary cilium.

Confocal images of MDCK cells with stable, inducible expression of PKHD1-NE,C7M that were cultured for 7 days post-confluence on Transwell filters and either left untreated (top) or treated with a calcium ionophore to induce ectodomain shedding for 30 minutes prior to preparation for imaging. “C-terminal PD1” identifies panels where specimens were co-stained with DAPI (blue), anti-Myc (green) and anti-acetylated tubulin (red). “N-terminal PD1” identifies panels where specimens were similarly co-stained except anti-EGFP (green) was used in place of anti-Myc to detect PD1. The reduced DAPI signal apparent in the bottom right set of panels is because the focal plane is above that of the nuclei in this image. All images were captured at 100X. The four panel images are X-Y sections while the single merge image below each four panel set is a representative Z-section.

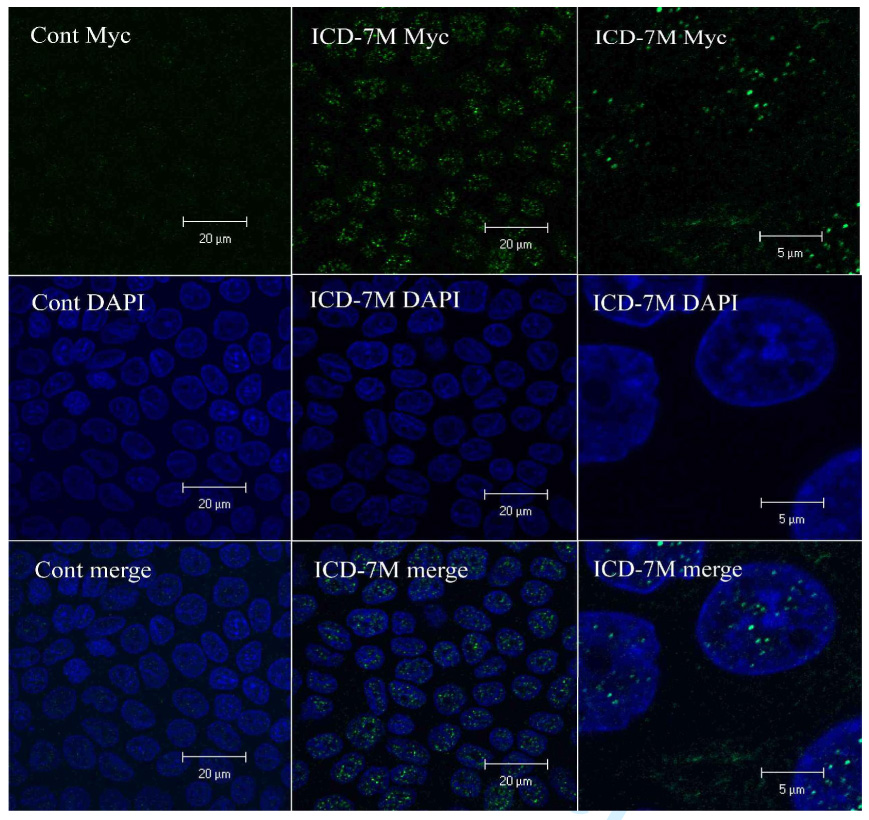

The PD1 C-terminus localizes to the nucleus

By analogy to Notch, we predicted that the C-terminal fragment of PD1 would translocate to the nucleus once released from the rest of the molecule by γ-secretase. However, only a low amount of nuclear staining was detected using antisera for the C-terminal tag of PD1 in cells expressing the full length protein at baseline and its intensity did not appreciably increase in response to activation (Fig. 5). Similar problems had been encountered with Notch and had been attributed to the relatively low abundance and short half-life of the cleavage products (29) (30). We therefore generated MDCK cell lines with inducible expression of an epitope-tagged cytoplasmic C-terminus of PD1 (ICD-C7M, Fig. 1) and determined where it localized within the cell. Nuclear staining was readily apparent upon induction of expression (Fig. 6), indicating that the C-terminus is capable of translocating to the nucleus under suitable conditions.

Figure 6. The PD1 C-terminus localizes to the nucleus.

Confocal images of MDCK cells with either stable, inducible expression of empty vector (left, Cont Myc) or ICD-C7M (middle), that were cultured for 7 days post-confluence on Transwell filters and stained with an anti-Myc antibody (top, green) and DAPI (middle, blue). The images at the bottom are the merged images of the upper and middle panels. The images on far left were captured at 100x while those on the right were taken at 400x.

Endogenous PD1 protein is shed from the primary cilia

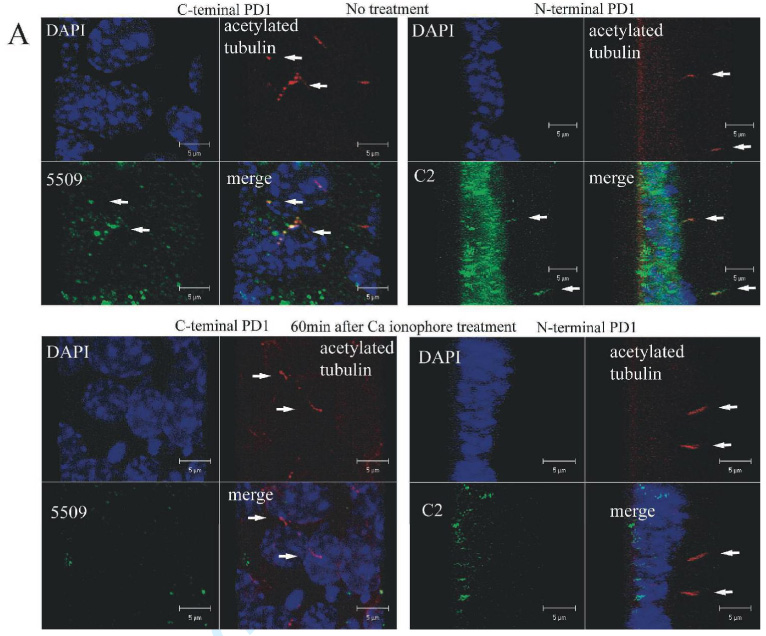

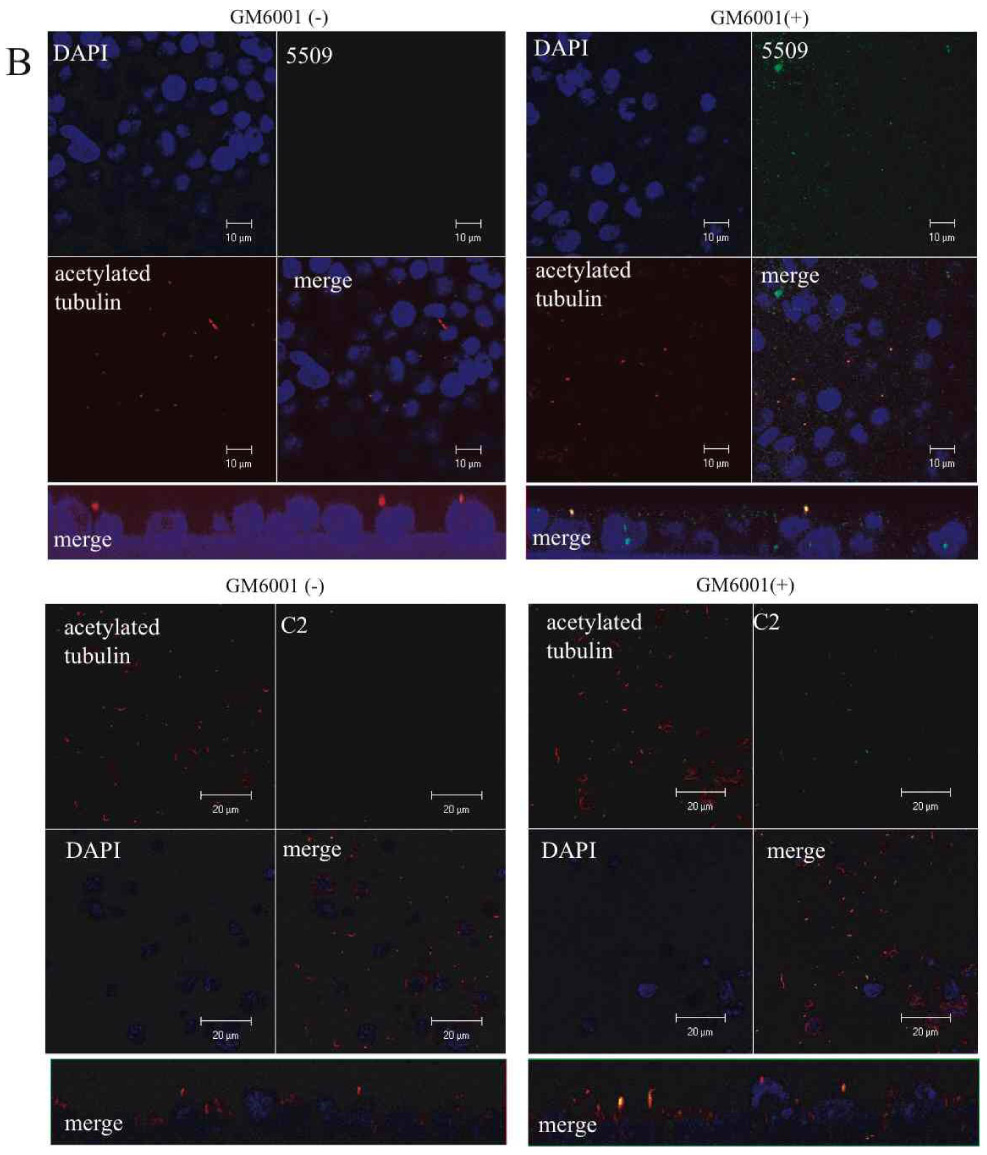

In a final set of experiments, we sought to determine if endogenous PD1 was subject to the same processing as the recombinant molecule. We selected IMCD cells, an SV-40 immortalized cell line derived from mouse inner medullary collecting duct epithelium (31) for these studies since they have previously been reported to express PD1 (16) (19). We first confirmed expression of PD1 in IMCD cells by reciprocal immunoprecipitation/immunoblot studies using FP-2, C2, 5509 and 210 antibodies. All of the antibodies recognized an dentically-sized, high molecular weight protein similar in size to the full-length recombinant protein; however, we were unable to identify PTM unambiguously by this technique since its predicted size is similar to that of IgG (data not shown). We attempted to circumvent this problem by examining the pattern of PD1 expression in whole cell lysates but were unsuccessful because of its very low level of expression. We therefore investigated the effects of sheddases on PD1 expression on a cellular level using confocal microscopy. Using antibodies that recognize epitopes in both the extracellular and intracellular portions of PD1, we found that PD1 localized to the primary cilia of IMCD cells cultured to post-confluence on transwells but disappeared from this structure upon stimulation with a calcium ionophore (Fig 7A, Supplement Movie #2). Moreover, we found that prior treatment with the broad metalloprotease inhibitor GM6001 prevented shedding of PD1 while treatment with vehicle alone did not (Fig 7B). These data strongly suggest that endogenous PD1 has the same key properties exhibited by the recombinant molecule.

Figure 7. Endogenous PD1 undergoes regulated ectodomain shedding.

A. Endogenous PD1 is shed from the primary cilium. 3D re-construction of confocal images of IMCD cells cultured for 7 days post-confluence on Transwell filters and either left untreated (top) or treated with a calcium ionophore to induce ectodomain shedding for 60 minutes prior to preparation for imaging. “C-terminal PD1” refers to a set of specimens stained for acetylated tubulin to identify the primary cilia and for the C-terminus of PD1 using antiserum 5509. The projected X-Y plane is presented. “N-terminal PD1” refers to a similar set of specimens stained with antibodies for acetylated tubulin and the N-terminus of PD1 using antiserum C2 and presented as a projection of the Z-axis. Arrows identify representative primary cilia. The data clearly show that PD1 is shed from the primary cilium under these experimental conditions. All images were captured at 400X (Supplementary Movie #2).

B. The metalloprotease inhibitor GM6001 inhibits shedding of endogenous PD1 from the primary cilia. Similar experimental design as the one used for Panel A except the metalloprotease inhibitor GM6001 was added to the medium for 60 min prior to treatment with a calcium ionophore to induce shedding. Cells were treated with a calcium ionophore and either GM6001 or vehicle (DMSO) for 60 minutes prior to preparation for imaging. Specimens were stained for acetylated tubulin to identify the primary cilia and for either the C-terminus of PD1 using antiserum 5509 (top) or the N-terminus of PD1 using antiserum C2 (bottom). The projected X-Y plane is presented on top and a projection of the Z-axis is shown below. All images were captured at 100X.

DISCUSSION

The ARPKD gene, PKHD1, is predicted to encode a novel protein of 4074 amino acids with a single TM and multiple IPT and PbH1 domains in its extracellular portion but whose function is largely unknown. PKHD1 undergoes a complicated pattern of splicing and therefore may encode a variety of additional gene products. These facts make investigation of its gene product, PD1, particularly difficult. Given the many challenges that this gene’s complexity posed, we developed a set of novel in vitro expression systems to study its function. By using a recombinant system with epitope tags, we could unambiguously track PD1 and then use this information to guide our study of the endogenous protein. The fact that we could show that the endogenous protein shares many of the properties defined for the recombinant molecule validates our system.

Using these tools, we discovered that PD1 is a plasma membrane-associated protein that undergoes a complicated pattern of proteolytic processing, producing multiple smaller products. We determined that some of the proteolytic reactions were regulated while others appeared constitutive under the conditions used. We found a likely proprotein convertase site in the extracellular domain of PD1 that appears responsible for producing a large, tethered N-terminal fragment present on the cell surface. Our studies suggest that a member of the ADAM metalloproteinase disintegrins family mediates shedding of this fragment. We also found that cleavage at this extracellular site is required for the concomitant regulated release of an intracellular C-terminal fragment, the latter step apparently a γ-secretase-dependent process. We used confocal analysis to show that PD1 that is localized to the primary cilium undergoes regulated shedding and intramembrane proteolysis (RIP). Finally, we confirmed that endogenous mouse PD1 has many of the same properties.

Since submission of our manuscript, Hiesberger et al have described complementary studies that support our findings (32). They expressed an epitope-tagged form of the human full length PKHD1 cDNA in IMCD and HEK cells and similarly detected a series of proteolytic products, including a C-terminal product that localized to the nucleus. They also found that release of the intracellular product was both constitutive and regulated by calcium and speculated that the process occurred in conjunction with ectodomain shedding. A putative nuclear localization sequence was identified in the C-terminus by deletion mapping. One difference between our findings and theirs is with respect to the nuclear localization pattern of our respective products. Hiesberger et al described a nucleolar pattern while we found a more punctate pattern consistent with localization to nuclear bodies or splicing speckles. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the epitope tags, cell lines or other unidentified factors. Further study will be required to resolve this issue.

The post-translational pattern of proteolytic processing of PD1 is very similar to what has been previously described for the key developmental protein, Notch (33) (34). Notch is synthesized as a single TM-spanning protein whose large extracellular domain is first cleaved by furin and then is tethered to the remainder of the protein. The mature receptor is expressed on the cell surface and its ectodomain is shed in response to binding of its ligand (Jagged and others). Ligand binding also results in regulated intra-membranous proteolysis (RIP) and release of a cytoplasmic C-terminus that enters the nucleus and switches a DNA-bound co-repressor complex into one that is activating. There also is evidence that the shed Notch/ligand complex may have additional functional activity, suggesting that Notch has bi-directional signaling. We hypothesize that PD1 may have similar properties. The shed ectodomain may function as a ligand for other cellular receptors while its RIP product may have direct signaling functions.

We also note that Notch and PD1 have a number of dissimilar features that likely reflect differences in their underlying function. In the case of Notch, the receptor-ligand interaction occurs between adjacent cells and functions to determine cell fate. In the case of PD1, we cannot unambiguously localize the protein to the site of cell-cell interactions in the cell types examined. Instead, we have shown that it traffics to the primary cilium from where it undergoes regulated shedding. This result has a number of important implications. Firstly, it may mean that ectodomain shedding and RIP for PD1 are not ligand-mediated but instead regulated by other processes that locally activate ADAM sheddases. Such a mechanism has been described for transactivation of the EGF receptor by G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). Ligand binding to GPCR activates an ADAM sheddase, which then results in release of EGF ligand (35). In the case of PD1, activation of other ciliary receptors or flow-mediated changes in calcium flux may mediate this process. Alternatively, PD1 may function like Notch as a receptor but its ligand is either a secreted molecule present in the lumen or a factor also present on the surface of the primary cilium. This observation, coupled to the fact that the ectodomain is shed into the lumen and thus potentially projected beyond adjacent cell boundaries, suggests important functional differences between Notch and PD1.

We presently are unable to determine whether the PD1 intracellular cleavage products have a fate similar to that of Notch. Under standard conditions, we detect C-terminal signal in the nucleus by confocal analysis, but we have not yet been able to unequivocally demonstrate an increase in nuclear signal after induction of ectodomain shedding and RIP. This is not necessarily surprising since the products may be short-lived and of low abundance. Similar problems had been encountered with Notch (29) (30). In the absence of a known set of transcriptional targets or nuclear co-factors, it may be difficult to demonstrate a nuclear function for PD1’s terminal cleavage products. Further study will be required to resolve this issue.

As noted above, there was an additional set of C-terminal products and a high molecular weight N-terminal product that were constitutively present in the cell cytoplasm and tissue culture medium, respectively. We presently are unable to determine whether these are the result of low-level activation of regulated cleavage or the result of different processes. We also do not know where in the cell the precursor form of PD1 is localized at the time of cleavage or whether endogenous PD1 has this same property. Addressing the last question will be a considerable challenge given the relatively low level of expression of PD1 in IMCD cells.

The observation that the extracellular domain is shed from the primary cilium prompts speculation as to what it may do. It is possible that the domain primarily serves as a receptor and that the shed fragment has no function post-release from the cell surface. A number of receptors are down-regulated by this mechanism. However, many ectodomains that are released from other integral membrane proteins have biologically significant properties, and we predict the same for PD1. One possibility is that the ectodomain functions in a paracrine fashion. In ductal and tubular epithelial cells that line lumens with flow, its release from primary cilia into the lumen may be a mechanism to distribute signal to down-stream or adjacent targets beyond the immediate point of cell-cell contact. One intriguing possibility is that flow-based delivery of the shed product may be a way of maintaining planar orientation with respect to the longitudinal axis (Fig. 8). In other cell types, cilia-based release may be a way to project signal beyond the immediate vicinity. This may serve as a means of coordinating the activity of a group of cells rather than that of just a single neighbor. This potentially could be an important way to coordinate the activity of cells to form tubular structures of defined diameter.

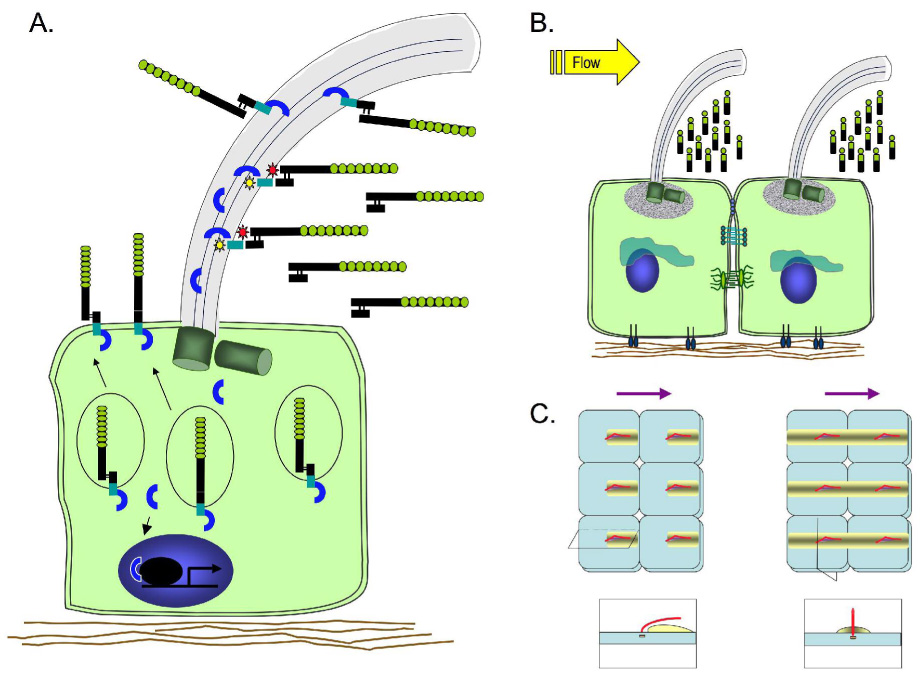

Figure 8. Model of PD1 processing and function.

A. A subset of PD1 molecules is subject to post-translational processing by a proprotein convertase, resulting in an N-terminus that is tethered to the C-terminal product. A second set of PD1 molecules traffics to the plasma membrane without processing and undergoes constitutive release of intracellular cytoplasmic products. Upon metalloprotease activation, PD1 sheds its ectodomain into the lumen and the cytoplasmic C-terminus leaves the plasma membrane.

B. Flow-based delivery of the shed PD1 ectodomain may help maintain cellular planar orientation by helping to deliver an asymmetric gradient of signal.

C. Two models of how flow-based distribution of shed product could theoretically establish signal gradients and thus orientation information for tubular cells. The panels on top represent the view looking down on the cell surface of a cluster of six cells each with a central primary cilium (red) leaning in the direction of flow (purple arrows on top). The yellow shaded rectangle represents the signal gradient resulting from shed PD1 ectodomain. The panels on the bottom represent sections taken either along the longitudinal axis of the tubule through the primary cilium (left) or orthogonal to the direction of luminal flow through the center of the cell (right). The two models differ in that the gradient is parallel to the direction of flow in one (left) and perpendicular to it in the other (right).

In conclusion, we have shown that PD1 undergoes Notch-like processing and regulated release of its ectodomain from primary cilia. This is the first known example of this process involving a protein of the primary cilium and suggests a novel mechanism whereby proteins that localize to this structure may function as bi-directional signaling molecules.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Reagents

The following vendors were sources for the reagents used in this study: Roche Applied Science (Mannheim, Germany): monoclonal anti Myc antibody, protease inhibitor cocktail; Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany): mouse monoclonal anti-acetylated tubulin, polyclonal anti FLAG antibody and M2 anti FLAG beads, polyclonal anti Myc beads, p3xFLAG-CMV10, A23187, phorbol12-myristate13-acetate (PMA), sodium orthovanadate and hydrogen peroxide; Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA): rabbit anti Myc antibody; Clontech (Palo Alto, CA): monoclonal anti Myc beads, rabbit anti GFP antibody; Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA): Goat fluoresein conjugated anti rabbit IgG antibody, Goat Texas Red conjugated anti mouse IgG antibody; Molecular Probe (Eugene, OR): Alexa-488 conjugated anti fluoresein antibody; Pierce (Rockford, IL): NHS-SS-biotin, streptavidin-agarose beads; Gibco/Invitrogen (Gaithersburg, MD) DMEM, DMEM/F12 and heat inactivated fetal bovine serum; Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany): GM6001 and L-685, 458; Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA.): Flp-In T-Rex 293 cell line, pcDNA5/FRT/TO, pOG44, pFRT/lacZeo and pcDNA6/TR, pcDNA3.1, LipofectAMINE 2000; Promega (Madison, WI): pCI vector; ATCC (Manassas, VA): MDCK-II cells; InvivoGen (San Diego, CA): blasticidin, hygromycin B; Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA): goat polyclonal anti-Vangl2 antibody; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA): Cy3-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antibody.

Expression Constructs

We assembled a full length cDNA by amplifying three overlapping cDNA fragments from a kidney cDNA library (6) using the following sets of primers and conditions: F1: 5’-GAAAGGATCATTTCTCCCTTGAGTC-3’, R1: 5’-CAGGAACTTGACTCCATAGGGAAAG-3’; F2: 5’-GCCCAATCAGCCAATTACCG-3’, R2: 5’-TCTTCTTAGTTGTCCCAGCAGGAC-3’ using Platinum Taq DNA polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen): 94°C for 2 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 64°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 6 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Each product was sequenced and several point mutations were corrected by using site-directed mutagenesis. They were assembled into the largest full length cDNA using restriction enzyme sites Kpn I, Sph I and BseM I. The junctional cloning sites of the final assembled cDNA were verified by DNA sequencing. The full-length PKHD1 cDNA was then inserted into the expression vector PCI using the restriction enzyme sites, Xho I and Not I. An expression vector with a 7x-Myc tag inserted at the C-terminus was generated by ligation using Sal I and Not I. The 6xMyc tag DNA sequence from CS2-MT (R.Kopan, Washington University School of Medicine) was used to help construct the tag. An expression vector with a 3x-FLAG tag or an EGFP tag inserted after the signal sequence and the adjacent 2 amino acids was generated by ligation using EcoN1 and Sca1 sites. An expression vector with a 3x-FLAG tag or an EGFP tag at its N-terminus and 7xMyc tag at its C-terminus was made by repeated ligation as described above and the sequence of each junction was verified. The various PKHD1 constructs were also cloned into the Not I and EcoRV sites of pcDNA5/FRT/TO for stable transfection.

Expression of recombinant PKHD1 in HEK 293 and MDCK cells

For transient expression studies, pCI-PKHD1 was transfected into HEK293 using LipofectAMINE 2000 and analyzed for PD1 expression 24–48h later. For studies requiring stable, inducible expression of PKHD1, we used the Flp-In T-Rex 293 cell line and a newly developed Flp-In T-Rex MDCK cell line (manuscript in prep). These cell lines contain the tetracycline repressor as well as an FRT site for targeted integration. Stable cell lines were established by co-transfecting the pcDNA5/FRT/TO constructs together with the Flp recombinase expression plasmid pOG44 using LipofectAMINE 2000. Cells with proper integration of our constructs into the single FRT site of the Flp-In T-Rex 293 cells were selected in medium containing 100 µg/ml hygromycin B. After selection, cell lines were maintained in DMEM containing 2mM L-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 15 µg/ml blasticidin and 100 µg/ml hygromycin B. The Flp-In T-Rex MDCK cell lines were selected under similar conditions except hygromycin B was at a concentration of 150 µg/ml. Stable transfectants were maintained in DMEM 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 5µg/ml blasticidin and 150 µg/ml hygromycin B. A set of control MDCK cell lines were similarly established by transfection of empty vector (pcDNA5/FRT/TO)

Western Blots and Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Na phosphate (pH 7.2), 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail. Pervanadate was prepared just prior to use by adding sodium orthovanadate to hydrogen peroxide. The sample was subjected to electrophoresis on 3–8% gradient SDS-PAGE gels after boiling. Fractionated proteins were electrotransfered to Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and detected with monoclonal anti-Myc antibody (1: 1000), polyclonal anti-FLAG antibody (1:500), 5509 anti peptide antibody (1:1000), C2 anti N-terminal PD1 (1:1000) antibody, 210 anti peptide antibody (1: 1000) using ECL enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Life Science, Piscataway, NJ) (16). Immunoprecipitation from cellular lysates was carried out as described previously with slight modifications (36). Cells were lysed in the buffer described above, and then one ml of total cell lysate was pre-incubated with monoclonal anti-Myc beads, polyclonal Myc beads or M2, anti-FLAG beads at 4 °C for over night, then centrifuged at 3000rpm. The precipitated beads were washed extensively with cell lysis buffer and finally eluted with SDS sample buffer. The eluted supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

To test for constitutive secretion of N-terminal products, PKHD1 constructs were transfected into Flp-In T-Rex 293 cells and cultured for 24h in the presence of serum and tetracycline, at which time the medium was replaced with serum-free medium containing 1µg/ml tetracycline. The medium was collected 48h later, centrifuged to remove cellular debris, and then incubated with M2-beads overnight at 4°C to immunopurify the N-terminus using methods outlined above. Regulated ectodomain shedding was assayed by culturing uninduced cells of the PKHD1+ Flp-In T-Rex 293 stable cell line overnight in serum-free medium containing 1µg/ml tetracycline followed by the addition of various known activators of cleavage at concentrations indicated in the text. Medium was collected at the times indicated and treated as indicated above.

Cell surface biotinylation assay

The assay was performed using published methods (37). Stable PKHD1+ Flp-In T-Rex 293 cells were treated with tetracycline 1µg/ml over night and then serum-starved for 5hr. The surface plasma membrane proteins were biotinylated by gently shaking the cells for 40 min with 3.0mg of NHS-SS-biotin at 4°C. After biotinylation, the unreacted biotin was scavenged by incubating the cells with DMEM medium containing 10% FCS for 10 minutes. Cell lysates were subsequently prepared, centrifuged at 12000g for 10 minutes, and then the supernatant was incubated with streptavidin-agarose beads overnight at 4°C. The mix was subsequently centrifuged at 1000g for 5 minutes, with the beads washed three times prior to elution of the sample with SDS sample buffer and analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

PD1 antibodies

Anti-FP2 recognizes the C-terminus of human PD1 and has been previously described (16). Anti-C2 was raised against a recombinant polypeptide derived from the extra-cellular sequence of human PD1 (aa 3214–3394). We generated two new rabbit polyclonal antibodies using synthetic polypeptides CPHQLMNGVSRRKVSR (5509, human PD1 aa 3942–3957) and WPQEPWHKVRSHHSV (210, mouse PD1 aa 3248–3262). The immunized rabbit serum was affinity purified using the AminoLink Plus Immobilization Kit, (Pierce).

Evaluation of regulated cleavage

PD1 expression was induced in the Flp-C-terminal 7xMyc PKHD1 HEK293 cell line by culturing the cells overnight in serum-free medium containing tetracycline 1µg/ml. The Flp-C-terminal 7xMyc PKHD1 HEK293 cell line was cultured overnight in serum-free medium containing a protease inhibitor (either GM6001, L-685, or 458) and tetracycline 1µg/ml to induce PD1 expression. The next morning, cells were treated with either calcium ionophore A23187 or PMA to stimulate cleavage, incubated for the indicated times, and then harvested. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting by using anti-Myc antibody.

Confocal microscopy

Flp-C-terminal 7xMyc PKHD1 MDCK cells or Flp-N-terminal EGFP, C-terminal 7xMyc MDCK cells were cultured on 12-mm Transwell filters (Corning, Acton, MA) in DMEM 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 5µg/ml blasticidin and 150 µg/ml hygromycin B. The cells were grown at least seven days post-confluence, changing the medium every other day. The expression of PD1 was induced by addition of 1µg/ml tetracycline 2 days before the staining. The staining was performed according to a previously described method with slight modifications (37). Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, placed in 75mM NH4Cl and 20mM glycine in PBS at room temperature to quench the fixative, and then permeabilized with −20 °C methanol for 3min. After blocking with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-myc antibody 1:100, mouse anti-acetylated tubulin antibody 1:400, rabbit anti-GFP antibody 1:100) overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies (goat fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody 1:100, goat Texas red-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody 1:100) for 1h at room temperature. After washing, the cells were incubated with an Alexa-488 conjugated anti-fluorescein antibody (1:100) for 1h at room temperature. IMCD cells were processed similarly and incubated with rabbit 5509 or C2 antibody as primary antibodies. Cells were washed in PBS before mounting in mounting medium with DAPI (Vector). The stained cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope with 510-Meta confocal module (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using a Plan-Apochromat 100x/1.4 NA DIC lens with Immersol 518F oil at RT. 0.2 µm z sectionswere captured and 3D images were reconstructed using AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the NIH (NIDDK DK51259), the National Kidney Foundation and the PKD Foundation. The authors wish to thank members of the Germino, Qian and Watnick laboratories for their helpful advice. GGG is the Irving Blum Scholar of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS

- ARPKD

autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease

- PKHD1

Polycystic Kidney and Hepatic Disease-1

- PD1

polyductin

- IPT

Immunoglobin-like fold shared by Plexins and Transcription factors

- PbH1

Parallel Beta-Helix 1 repeat

- FABB

flagella-basal body proteome

- NECD

N-terminal ExtraCellular Domain

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST The authors have nothing relevant to this study to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zerres K, Mucher G, Becker J, Steinkamm C, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Heikkila P, Rapola J, Salonen R, Germino GG, Onuchic L, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD): molecular genetics, clinical experience, and fetal morphology. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;76:137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guay-Woodford LM, Desmond RA. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: the clinical experience in North America. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1072–1080. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fonck C, Chauveau D, Gagnadoux MF, Pirson Y, Grunfeld JP. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease in adulthood. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001;16:1648–1652. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.8.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guay-Woodford L. Autosomal recessive disease:clinical and genetic profiles. In: Watson ML, Torres VE, editors. Polycystic Kidney Disease. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zerres K, Mucher G, Bachner L, Deschennes G, Eggermann T, Kaariainen H, Knapp M, Lennert T, Misselwitz J, von Muhlendahl KE, et al. Mapping of the gene for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) to chromosome 6p21-cen. Nat. Genet. 1994;7:429–432. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onuchic LF, Furu L, Nagasawa Y, Hou X, Eggermann T, Ren Z, Bergmann C, Senderek J, Esquivel E, Zeltner R, et al. PKHD1, the polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 gene, encodes a novel large protein containing multiple immunoglobulin-like plexin-transcription-factor domains and parallel beta-helix 1 repeats. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1305–1317. doi: 10.1086/340448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward CJ, Hogan MC, Rossetti S, Walker D, Sneddon T, Wang X, Kubly V, Cunningham JM, Bacallao R, Ishibashi M, et al. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:259–269. doi: 10.1038/ng833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong H, Chen Y, Yi Y, Tsuchiya K, Moeckel G, Cheung J, Liang D, Tham K, Xu X, Chen XZ, et al. A novel gene encoding a TIG multiple domain protein is a positional candidate for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Genomics. 2002;80:96–104. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagasawa Y, Matthiesen S, Onuchic LF, Hou X, Bergmann C, Esquivel E, Senderek J, Ren Z, Zeltner R, Furu L, et al. Identification and characterization of Pkhd1, the mouse orthologue of the human ARPKD gene. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:2246–2258. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000030392.19694.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann C, Senderek J, Windelen E, Kupper F, Middeldorf I, Schneider F, Dornia C, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Konrad M, Schmitt CP, et al. Clinical consequences of PKHD1 mutations in 164 patients with autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) Kidney Int. 2005;67:829–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharp AM, Messiaen LM, Page G, Antignac C, Gubler MC, Onuchic LF, Somlo S, Germino GG, Guay-Woodford LM. Comprehensive genomic analysis of PKHD1 mutations in ARPKD cohorts. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:336–349. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.024489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furu L, Onuchic LF, Gharavi A, Hou X, Esquivel EL, Nagasawa Y, Bergmann C, Senderek J, Avner E, Zerres K, et al. Milder presentation of recessive polycystic kidney disease requires presence of amino acid substitution mutations. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:2004–2014. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000078805.87038.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward CJ, Yuan D, Masyuk TV, Wang X, Punyashthiti R, Whelan S, Bacallao R, Torra R, LaRusso NF, Torres VE, et al. Cellular and subcellular localization of the ARPKD protein; fibrocystin is expressed on primary cilia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2703–2710. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, Fan Y, Teslovich TM, May-Simera H, Li H, Blacque OE, Li L, Leitch CC, et al. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Ward CJ, Masyuk AI, Yuan D, Splinter PL, Punyashthiti R, Ritman EL, Torres VE, Harris PC, et al. Defects in cholangiocyte fibrocystin expression and ciliary structure in the PCK rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menezes LF, Cai Y, Nagasawa Y, Silva AM, Watkins ML, Da Silva AM, Somlo S, Guay-Woodford LM, Germino GG, Onuchic LF. Polyductin, the PKHD1 gene product, comprises isoforms expressed in plasma membrane, primary cilium, and cytoplasm. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1345–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang S, Luo Y, Wilson PD, Witman GB, Zhou J. The autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease protein is localized to primary cilia, with concentration in the basal body area. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004;15:592–602. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000113793.12558.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer E, Legue E, Doyen A, Nato F, Nicolas JF, Torres V, Yaniv M, Pontoglio M. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mai W, Chen D, Ding T, Kim I, Park S, Cho SY, Chu JS, Liang D, Wang N, Wu D, et al. Inhibition of Pkhd1 impairs tubulomorphogenesis of cultured IMCD cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4398–4409. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duckert P, Brunak S, Blom N. Prediction of proprotein convertase cleavage sites. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2004;17:107–112. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama K. Furin: a mammalian subtilisin/Kex2p-like endoprotease involved in processing of a wide variety of precursor proteins. Biochem. J. 1997;327(Pt 3):625–635. doi: 10.1042/bj3270625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henrich S, Cameron A, Bourenkov GP, Kiefersauer R, Huber R, Lindberg I, Bode W, Than ME. The crystal structure of the proprotein processing proteinase furin explains its stringent specificity. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:520–526. doi: 10.1038/nsb941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergmann C, Senderek J, Kupper F, Schneider F, Dornia C, Windelen E, Eggermann T, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Kirfel J, Furu L, et al. PKHD1 mutations in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) Hum. Mutat. 2004;23:453–463. doi: 10.1002/humu.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huovila AP, Turner AJ, Pelto-Huikko M, Karkkainen I, Ortiz RM. Shedding light on ADAM metalloproteinases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilhelmsen K, van der Geer P. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced release of the colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor cytoplasmic domain into the cytosol involves two separate cleavage events. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:454–464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.454-464.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan S, Hurd TW, Liu CJ, Straight SW, Weimbs T, Hurd EA, Domino SE, Margolis B. Polarity proteins control ciliogenesis via kinesin motor interactions. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1451–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng L, Okuhara D, Yu Z, Tian X, Cai Y, Shibazaki S, Somlo S. Polycystin-2 traffics to cilia independently of polycystin-1 by using an N-terminal RVxP motif. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:1383–1395. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross AJ, May-Simera H, Eichers ER, Kai M, Hill J, Jagger DJ, Leitch CC, Chapple JP, Munro PM, Fisher S, et al. Disruption of Bardet-Biedl syndrome ciliary proteins perturbs planar cell polarity in vertebrates. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1135–1140. doi: 10.1038/ng1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, Schroeter EH, Schrijvers V, Wolfe MS, Ray WJ, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent gamma-secretase-like protease mediates release of Notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398:518–522. doi: 10.1038/19083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rauchman MI, Nigam SK, Delpire E, Gullans SR. An osmotically tolerant inner medullary collecting duct cell line from an SV40 transgenic mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:F416–F424. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.265.3.F416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiesberger T, Gourley E, Erickson A, Koulen P, Ward CJ, Masyuk TV, Larusso NF, Harris PC, Igarashi P. Proteolytic cleavage and nuclear translocation of fibrocystin is regulated by intracellular Ca2+ and activation of protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34357–34364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harper JA, Yuan JS, Tan JB, Visan I, Guidos CJ. Notch signaling in development and disease. Clin. Genet. 2003;64:461–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-0004.2003.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweisguth F. Notch signaling activity. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R129–R138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iwamoto R, Mekada E. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor: a juxtacrine growth factor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qian F, Boletta A, Bhunia AK, Xu H, Liu L, Ahrabi AK, Watnick TJ, Zhou F, Germino GG. Cleavage of polycystin-1 requires the receptor for egg jelly domain and is disrupted by human autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease 1-associated mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16981–16986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252484899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akhter S, Cavet ME, Tse CM, Donowitz M. C-terminal domains of Na(+)/H(+) exchanger isoform 3 are involved in the basal and serum-stimulated membrane trafficking of the exchanger. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1990–2000. doi: 10.1021/bi991739s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.