Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that the proteolytic cleavage of the microtubule-associated protein tau, the main component of neurofibrillary tangles, might play a role in the molecular mechanisms underlying beta-amyloid (Aβ)-induced neurotoxicity in central neurons. In the present study, we analyzed whether sex hormones could prevent such tau cleavage, and hence, protect hippocampal neurons against Aβ toxicity. Our results indicated that estrogen and testosterone prevented caspase-3- and calpain-mediated tau cleavage, respectively. Thus, estrogen decreased the levels of caspase-3-cleaved 50-kDa truncated tau, while testosterone prevented the generation of a calpain-cleaved 17-kDa tau fragment. In addition, our results showed that the decrease in the levels of these tau proteolytic forms was accompanied by an increased cell survival in Aβ-treated neurons. Furthermore, our findings indicated that testosterone was more effective than estrogen in protecting hippocampal neurons against Aβ-induced cell death. Collectively, our data suggest that preventing the decline of estrogen and testosterone associated with normal aging might reduce the susceptibility of central neurons to Aβ-induced toxicity.

Keywords: tau, beta-amyloid, apoptosis, caspase-3, calpain, neurotoxicity

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by the presence of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in vulnerable brain regions. These lesions are the result of the abnormal deposition of beta amyloid (Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, respectively (Glenner and Wong, 1984; Kosik et al., 1986; Wood et al., 1986; Kondo et al., 1988; Yankner and Mesulam, 1991; Selkoe, 1994; Parihar and Hemnani, 2004; Stern et al., 2004). A growing body of evidence suggests that the deposition of Aβ might trigger a series of cellular events that lead to posttranslational changes in tau followed by neurite degeneration. However, the molecular mechanisms linking Aβ and tau pathology are not completely known. Previously, it has been shown that the deposition of Aβ induced the activation of calpain-1 and caspase-3, proteases known to play a role in the pathogenesis of AD (Saito et al., 1993; Grynspan et al., 1997; Tsuji et al., 1998; Gamblin et al., 2003; Veeranna et al., 2004; Park and Ferreira, 2005). These proteases cleave tau proteins at specific sites generating toxic tau fragments or enhancing the aggregation properties of this microtubule-associated protein. Thus, calpain activation resulted in the generation of a 17-kDa tau fragment in cultured hippocampal neurons. Conversely, inhibitors of this protease completely prevented tau proteolysis leading to the generation of this 17-kDa fragment and significantly reduced Aβ-induced neuronal death (Park and Ferreira, 2005). The deposition of Aβ also induced the activation of caspase-3. Active caspase-3 cleaved tau at residue 421 and generated a 50-kDa truncated tau lacking its C-terminal 20 amino acids. This truncated tau assembled more rapidly into filaments than full-length tau (Gamblin et al., 2003). The activation of these proteases, tau cleavage, and the extent of neurodegeneration were both time- and dose-dependent (Ferreira et al., 1987; Gamblin et al., 2003; Shah et al., 2003; Park et al., 2005, Kelly et al., 2005). Furthermore, similar caspase-3 and calpain activations were described when hippocampal neurons were incubated in the presence of Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 (Gamblin et al., 2003; Kelly et al., 2005). Collectively, these data suggest that the decrease in factors that prevent the activation of calpain and caspase-3, and hence tau cleavage, could have some bearing in the pathophysiology of AD. The decrease in estrogen and testosterone levels, a normal consequence of aging, could play such a role. Age-related hormonal depletion has been associated with the development of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD (Hogervorst et al., 2001; Morley, 2001; Moffat et al., 2004; Rosario et al., 2004). Conversely, many epidemiologic reports have suggested that hormone replacement therapy attenuates the development of AD in postmenopausal women (Tang et al., 1996; Kawas et al., 1997). More recently, it has been shown that testosterone also had beneficial effects on cognitive functions in men with AD (Cherrier et al., 2005). However, the mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of estrogen and/or testosterone have not been fully elucidated.

In the present study, we analyzed whether sex hormones exert their neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced toxicity, at least in part, by preventing tau cleavage. Our results showed that testosterone and dihydrotestosterone blocked the activation of calpain, and hence, decreased the generation of the 17-kDa tau fragment. On the other hand, estrogen partially prevented the activation of caspase-3 and the generation of caspase-3-cleaved 50-kDa truncated tau. The treatment with either sex hormone also decreased neurite degeneration and apoptosis in cultured hippocampal neurons treated with Aβ. Together, these results suggest that preventing the decline in sex hormones associated with aging might decrease the susceptibility of central neurons to some of the toxic effects induced by the accumulation of Aβ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of hippocampal cultures

Embryonic day 18 (E18) rat embryos were used to prepare hippocampal cultures as previously described (Goslin and Banker, 1991). Briefly, hippocampi were dissected and freed of meninges. The cells were dissociated by trypsinization (0.25% for 15 min at 37° C) followed by trituration with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette, and plated on poly-L-lysine-coated coverslips in MEM with 10% horse serum (plating medium). After 4 hours, the coverslips were transferred to dishes containing an astroglial monolayer and maintained in MEM containing N2 supplements plus ovalbumin (0.1%) and sodium pyruvate (0.1 mM) (N2 medium) (Bottenstein et al., 1979). For biochemical experiments, hippocampal neurons were plated at high density directly on poly-L-lysine coated cultured dishes (500,000 cells/60-mm dish) in MEM with 10% horse serum. After 4 hours, the plating medium was replaced with glia-conditioned N2 medium.

Aβ and hormone treatments

Synthetic Aβ(1-40), obtained from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA), was dissolved in N2 medium at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubated for 4 days at 37° C to preaggregate the peptide (Ferreira et al., 1997). Preaggregated Aβ was added to the medium of 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons at a final concentration of 20 μM. Cultured hippocampal neurons were incubated for 24 hours with the preaggregated Aβ.

For some experiments, 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons were treated with sex hormones for 24 hours prior to the incubation with preaggregated Aβ20 μM). Sex hormones (all from Sigma, St Louis, MO) were dissolved in ethanol and added directly to the culture medium at the following final concentrations: 17β estradiol 8 nM (Shah et al., 2003) and testosterone 10 nM (Pike, 2001). Testosterone acts through both estrogen (via aromatase conversion) and androgen (directly or as dihydrotestosterone) pathways. Therefore, we also performed experiments using dihydrotestosterone (10 nM) to differentiate these pathways (Pike, 2001).

Protein determination, electrophoresis, and immunoblotting

To prepare whole-cell extracts, cultures were rinsed twice in warmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), scraped into Laemmli buffer, and homogenized in a boiling water bath for 10 min. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels were run according to Laemmli (Laemmli, 1970). Transfer of protein to Immobilon membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and immunodetection were performed according to Towbin et al. (Towbin et al., 1979) as modified by Ferreira et al. (Ferreira et al., 1989). The following antibodies were used: anti-α-tubulin (clone DM1A, 1:500,000; Sigma), anti-tau (clone tau-5 1:1,000, Biosource, Camarillo, CA) anti-tau truncated at Asp421 (clone tau-C3, 1:1,000; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), anti-caspase-3 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, MA), anti-active caspase-3 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology Inc.), anti-calpain-1 (1:5,000; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), and anti-spectrin (1:1,000; Chemicon International). Secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:1,000; Promega Co., Madison, WI) followed by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) were used for the detection of proteins. Immunoreactive bands were imaged using a ChemiDoc XRS (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Densitometry of the images was performed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). At least 3 independent experiments for each experimental condition were used for the quantitative Western blots. Data were expressed as means ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test.

Immunocytochemistry and TUNEL assay

Hippocampal neurons were fixed for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS containing 0.12 M sucrose. They were then permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min and rinsed twice in PBS. The cells were preincubated in 10% bovine serum albumin for 1 hour at room temperature and exposed to the primary antibodies overnight at 4° C. The neurons were then rinsed in PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 hour at 37° C. The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-Class III β-tubulin (clone TuJ1; 1:500, Cambridge Bioscience, Cambridge, UK), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology Inc), and Alexa Fluor 568 (goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG, both at 1:200, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR).

Apoptotic cell death was assessed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, cells were fixed for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS containing 0.12 M sucrose, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate for 2 min, and the fluorescein labeled nucleotide was incorporated at 3’-OH DNA ends using the enzyme Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT). Apoptotic cells (TUNEL (+) cells) were counted using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon) and expressed as a percentage of total neurons. At least 200 cells from 3 independent experiments for each experimental condition were used to assess apoptosis. Data were expressed as means ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test.

Determination of protease activity

Calpain activity was determined by assessing spectrin cleavage as previously described (Czogalla and Sikorski, 2005). Briefly, whole cell extracts were prepared from hippocampal neurons cultured in the presence or absence of hormones and/or preaggregated Aβ and used for quantitative Western blot analysis with a spectrin antibody as described above. Since calpain cleavage produces characteristic spectrin fragments of 145- and 150-kDa (Siman et al., 1984), we determined the 150/240 kDa ratio under the different experimental conditions and compared it to the one obtained from Aβ-treated neurons. Values obtained from these Aβ-treated neurons were considered 100%. Calpain activity was also assessed by quantitative analysis of the 58-kDa active calpain fragment. Densitometry of immunoreactive bands corresponding to this 58-kDa fragment was performed as described above. Caspase-3 activity was determined by means of quantitative Western blot analysis using a specific anti-active caspase-3 antibody as described above. At least 3 independent experiments for each experimental condition were used for the quantitative Western blots. Data were expressed as means ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher’s LSD post-hoc test.

RESULTS

Estrogen and testosterone protected hippocampal neurons against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity

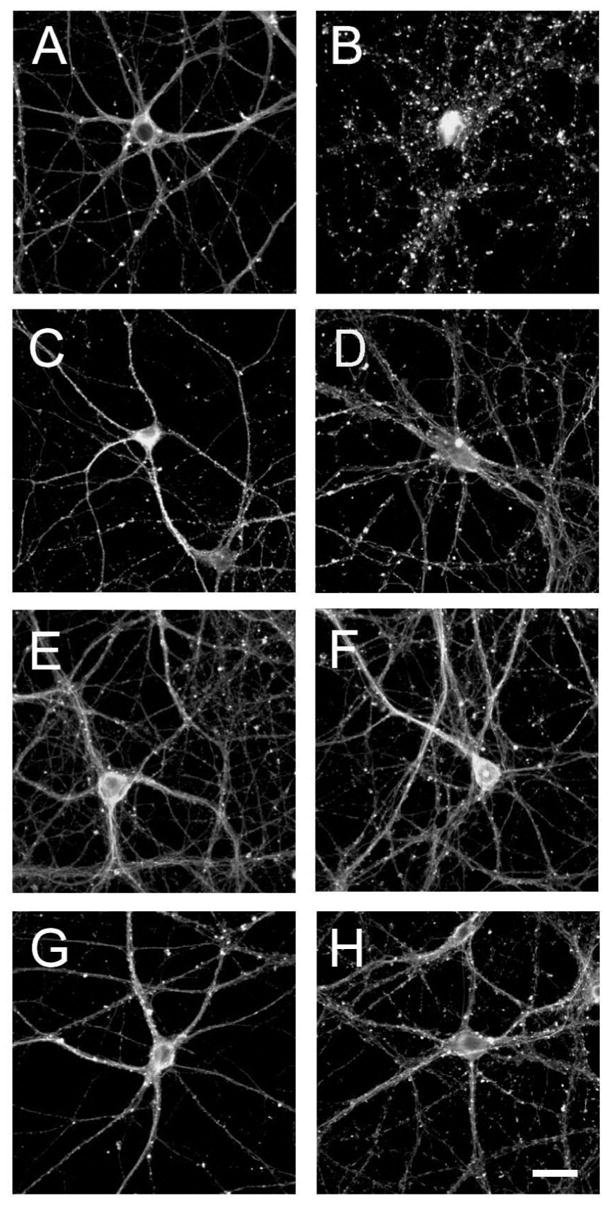

A growing body of evidence suggests that estrogen and testosterone partially prevent neurite degeneration induced by the deposition of preaggregated Aβ in young cultured hippocampal neurons (Goodman et al., 1996; Green et al., 1997; Gridley et al., 1997 & 1998; Green and Simpkins, 2000; Hammond, et al., 2001; Kim et al., 2001; Pike, 2001; Zhang et al., 2001). Estrogen also prevented neurite degeneration triggered by this peptide in mature hippocampal neurons (Shah et al., 2003). On the other hand, no comparable information is available on the neuroprotective effects of testosterone in mature hippocampal neurons. To gain insights into these effects, we performed a series of experiments using hippocampal neurons cultured for 3 weeks and preincubated with testosterone (10 nM), or dihydrotestosterone (10 nM) for 24 hours prior to their treatment with preaggregated Aβ (20 μM). We also treated mature hippocampal neurons with 17β-estradiol (8 nM) prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ (20 μM) to compare the protective effects of androgens with the ones exerted by estrogen. Twenty-four hours after the addition of preaggregated Aβ, cultured hippocampal neurons were fixed and immunostained using an antibody against Class III β-tubulin. The analysis of neuronal morphology showed no signs of degeneration (i.e. presence of neurites with tortuous course, the formation of varicosities, and neurite retraction) in untreated hippocampal neurons (Fig. 1A) or in neurons treated with either one of the hormones alone (Fig. 1C, E & G). In contrast, these signs of neurodegeneration were readily detectable in the majority (80 ± 4 %) of the hippocampal neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ (Fig. 1B). As previously described, estrogen partially prevented the formation of abnormal neuritic processes when added 24 hours prior to the addition of Aβ (Fig. 1 C). Quantitative analysis indicated that only 42 ± 6 % of the estrogen-treated neurons showed these signs of degeneration when exposed to preaggregated Aβ (Differs from neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ alone, P< 0.001)(see also Shah et al., 2003). Testosterone and its derived dihydrotestosterone also had potent neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced neurodegeneration in mature hippocampal neurons. Thus, very few signs of degeneration were detected in mature hippocampal neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ 24 hours after the addition of testosterone (24 ± 2 %*) or dihydrotestosterone (20 ± 2 %*. *Differs from neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ alone, P< 0.001)(Fig. 1F&H).

Figure 1.

Sex hormones attenuated Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Hippocampal neurons cultured for 21 days were incubated for 24 hours in the absence (A & B) or in the presence of 17β-estradiol (C & D), testosterone (E & F) or dihydrotestosterone (G & H). Neurons were then cultured in the absence (A, C, E & G) or in the presence (B, D, F & H) of preaggregated Aβ for additional 24 hours. The cells were then fixed and stained using a tubulin antibody. Most of the processes extended by neurons treated with Aβ showed signs of degeneration (B). Hormonal pretreatment significantly reduced the appearance of dystrophic neurites induced by Aβ (D, F & H). Scale bar: 20 μm.

Estrogen and testosterone prevented Aβ-induced apoptosis in mature hippocampal neurons

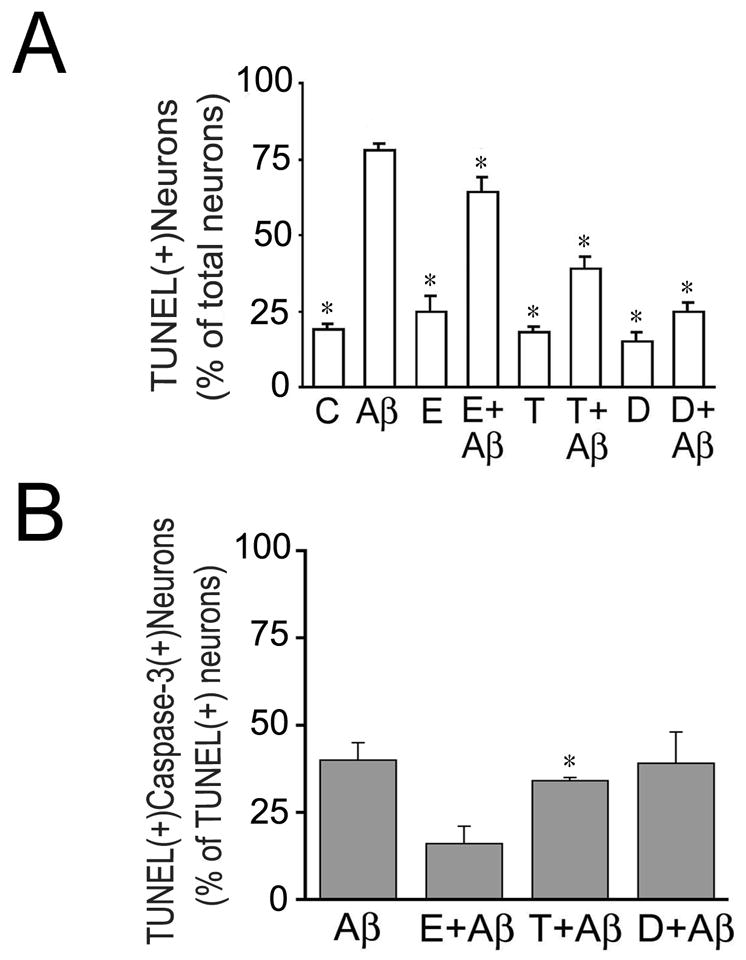

We determined next whether these hormones also protect mature hippocampal neurons against apoptosis induced by preaggregated Aβ. For these experiments, 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons were treated with estrogen, testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and/or preaggregated Aβ as described above. Twenty-four hours after the addition of preaggregated Aβ, the neurons were fixed and DNA fragmentation was examined using the In Situ Cell Death determination kit (TUNEL assay). Quantitative analysis showed that a few hippocampal neurons were TUNEL (+) in untreated controls (19 ± 2 %), 17β-estradiol- (25 ± 5%), testosterone- (18 ± 2%) or dihydrotestosterone- (15 ± 3%) treated neurons (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, more than two-third of the neurons (78 ± 2%) were TUNEL (+) in Aβ-treated cultures (Fig. 2A). The number of TUNEL (+) neurons in cultures pretreated with 17β-estradiol, testosterone, or dihydrotestosterone before the addition of preaggregated Aβ was significantly decreased when compared to neurons treated with Aβ alone (64 ± 5 % vs. 39 ± 4 % vs. 25 ± 3% vs. 78 ± 2 %, respectively, P< 0.01). These results suggested that both testosterone and dihydrotestosterone were more effective than estrogen in preventing apoptosis in cultured hippocampal neurons treated with Aβ.

Figure 2. Estrogen, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone reduced Aβ-induced apoptosis in cultured hippocampal neurons.

Three weeks in culture hippocampal neurons were incubated in the presence or absence of sex hormones and preaggregated Aβ as described in the Figure 1 legend. (A–C) Apoptosis was assessed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit and the neurons were counterstained using an antibody against active caspase-3 (B). Results were expressed as a percentage of TUNEL (+) neurons. Each number represents the mean ± S.E.M. from three different experiments. *Differs from Aβ-treated cultures, P<0.01

C: untreated controls, Aβ preaggregated Aβ 17β-estradiol, T: testosterone, D: dihydrotestosterone.

Next we performed a series of experiments to test whether Aβ-induced programmed cell death was accompanied by the activation of caspase-3. This protease has been implicated in apoptosis associated with several neurodegenerative diseases including AD (Grynspan et al., 1997; Tsuji et al., 1998; Veeranna et al., 2004). For these experiments, we took advantage of a specific caspase-3 antibody that recognizes only active forms of this protease. Aβ-treated neurons were fixed and processed for TUNEL assay and counterstained using an active caspase 3 antibody. Quantitative analysis showed the presence of two subsets of apoptotic neurons in Aβ-treated hippocampal neurons. Approximately half of the TUNEL (+) neurons were also active caspase-3 (+) while the other half was active caspase-3 (+) (Fig. 2). We next analyzed whether the pretreatment of cultured hippocampal neurons with estrogen, testosterone or dihydrotestosterone differentially prevented caspase-3 mediated apoptosis in the presence of preaggregated Aβ. Quantitative analysis showed that estrogen selectively decreased the number of TUNEL (+) hippocampal neurons that were also caspase-3 (+) when compared to neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ alone (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, testosterone and dihydrotestosterone did not decrease the number of TUNEL (+) and active caspase 3 (+) apoptotic hippocampal neurons when compared to cultures treated with Aβ alone (Fig. 2B). Together, these results suggested that testosterone and dihydrotestosterone reduced Aβ-induced apoptosis by decreasing the number of TUNEL (+) and active caspase 3 (−) hippocampal neurons.

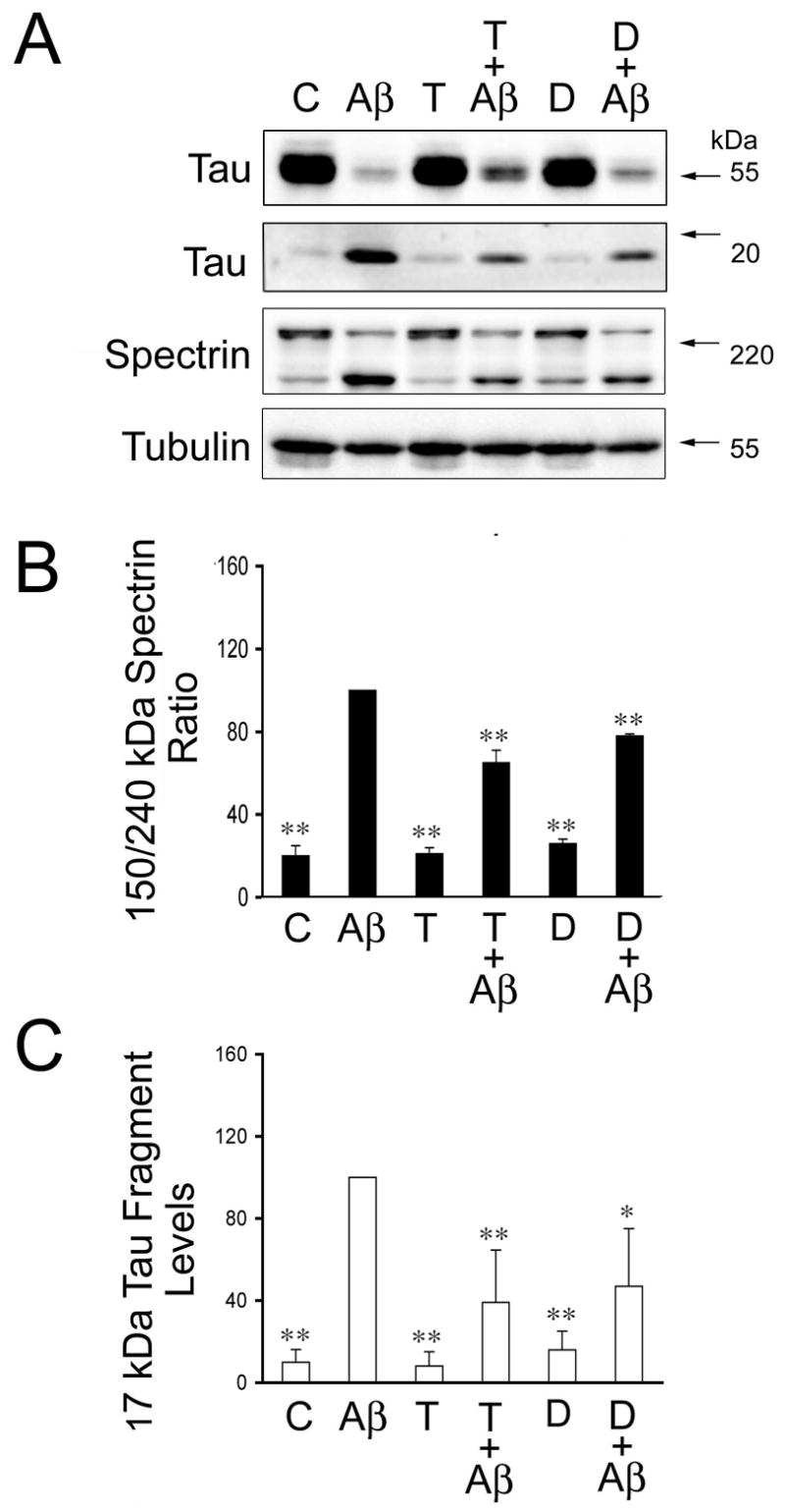

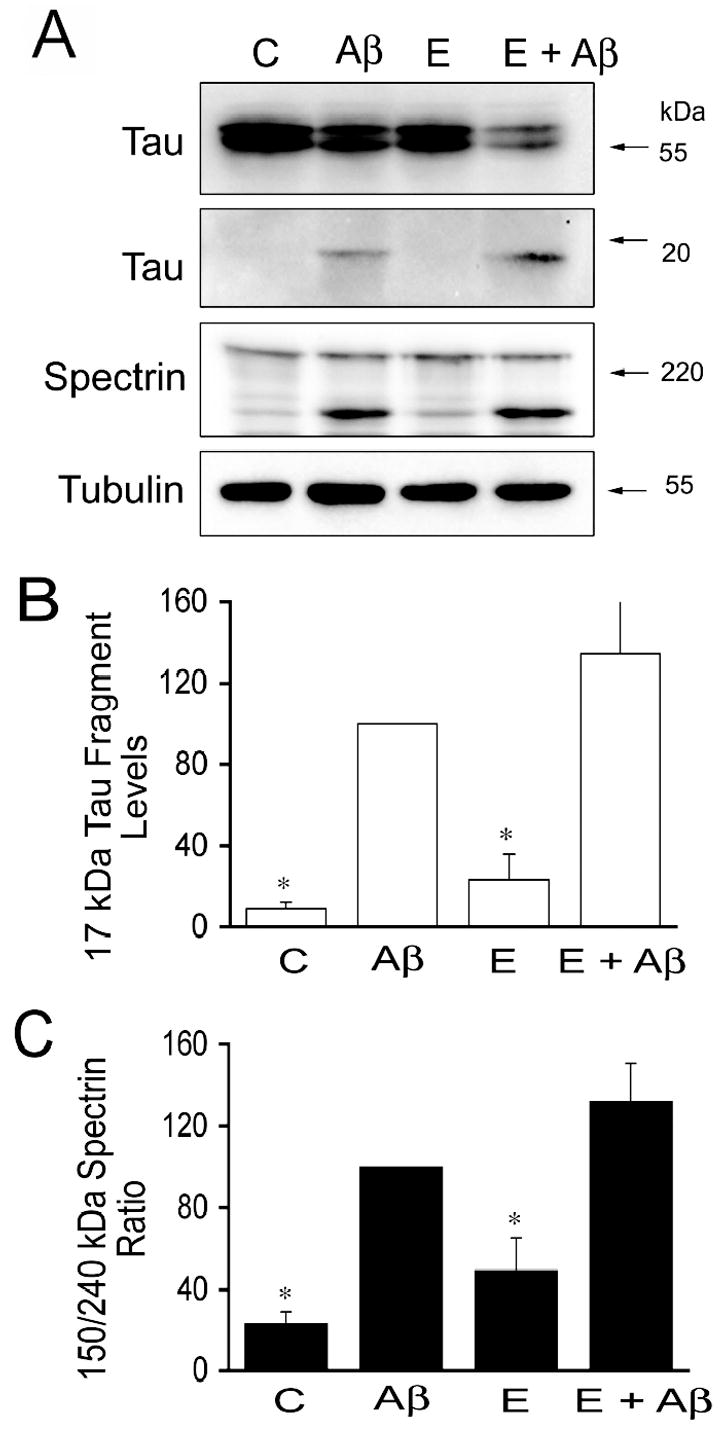

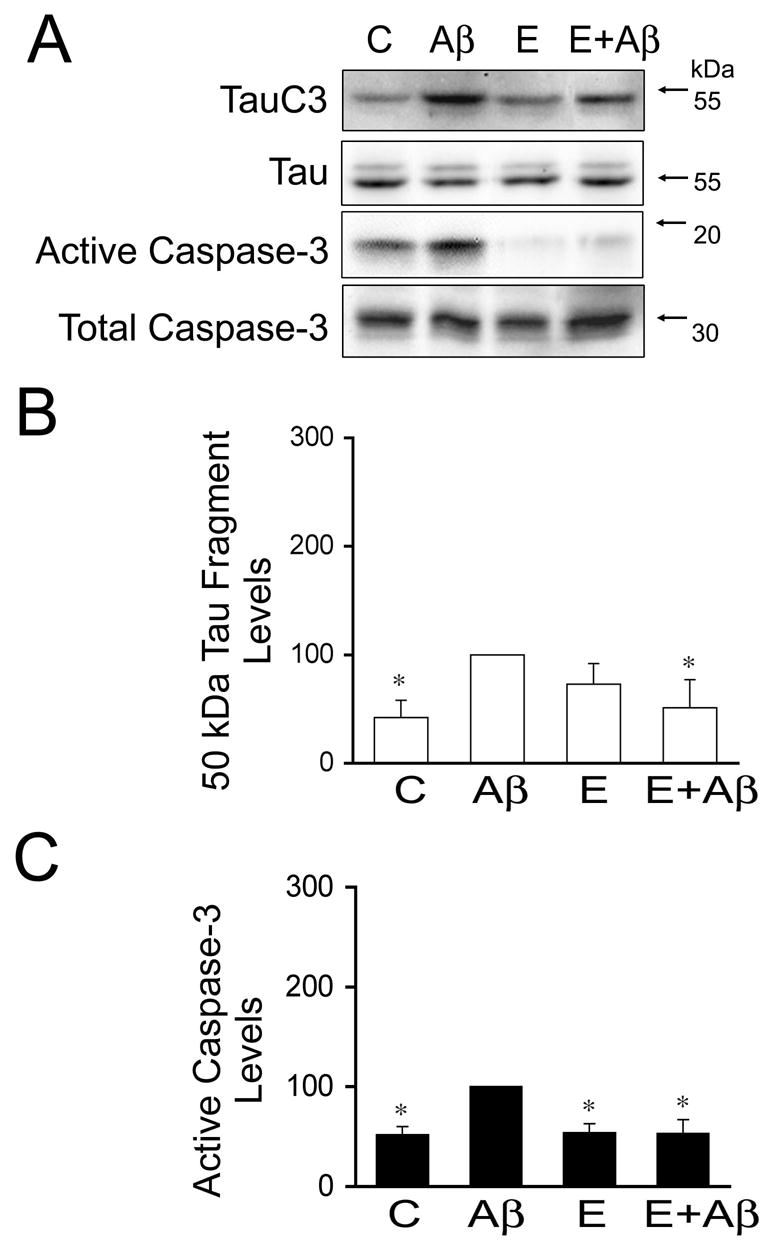

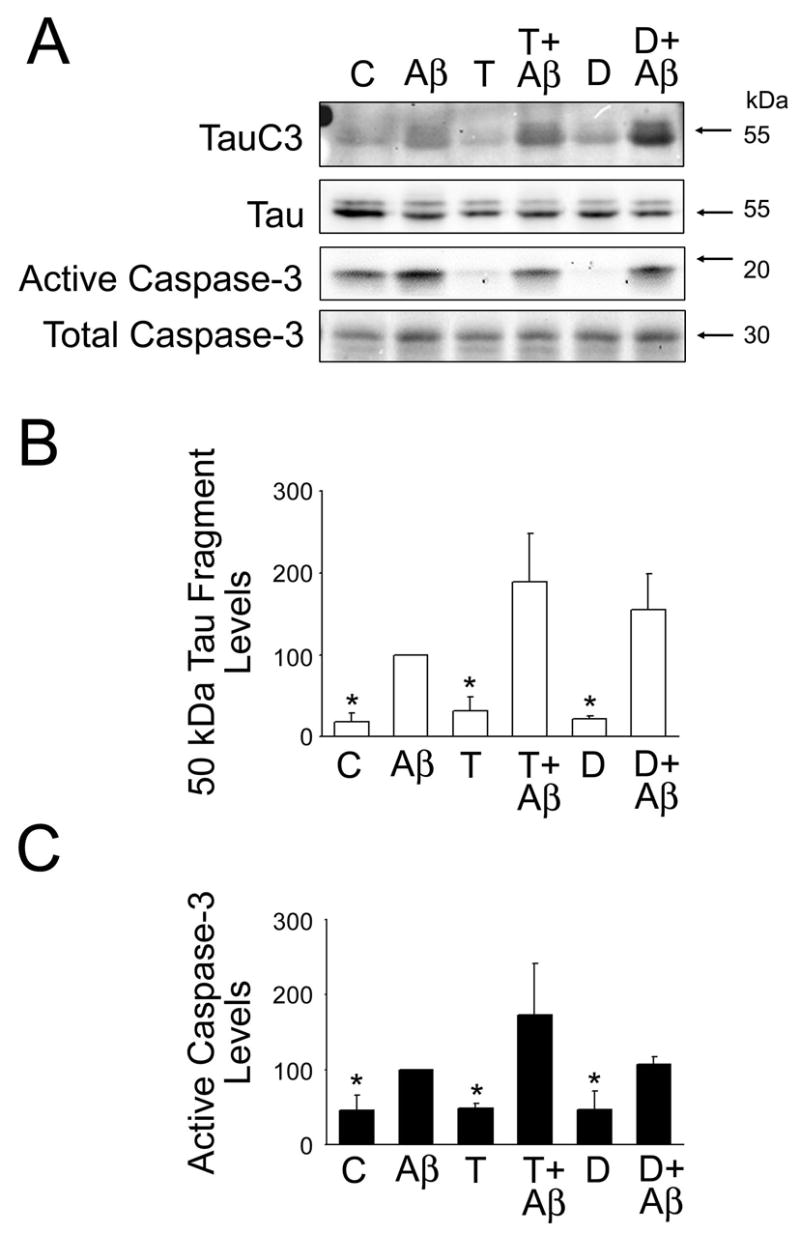

Testosterone and estrogen differentially prevented the calpain-mediated- and caspase-3 mediated-tau proteolysis induced by preaggregated Aβ in cultured hippocampal neurons

Finally, we assessed whether sex hormones prevented protease activation leading to tau cleavage in Aβ-treated neurons. For these experiments, hippocampal neurons cultured for 21 days were treated with testosterone, dihydrotestosterone, and estrogen for 24 hours and then incubated in the presence of preaggregated Aβ for an additional 24 hours. We assessed calpain activation in hippocampal neurons cultured under the experimental conditions described above by determining spectrin cleavage. Spectrin degradation is highly sensitive to calpain activation and considered an excellent marker for this protease activity (Czogalla and Sikorski, 2005). Western blot analysis of whole cells extracts reacted with a specific spectrin antibody showed a significant decrease in full-length spectrin (240-kDa) and a concomitant increase in the 150-kDa degradation fragment in cultured hippocampal neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ (Fig. 3A). Quantitative analysis of immunoreactive bands showed a significant increase in the 150/240-kDa spectrin ratio in hippocampal neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ when compared to untreated controls (Fig. 3B). This increase in the 150/240-kDa spectrin ratio was significantly reduced in hippocampal neurons cultured in the presence of testosterone or dihydrotestosterone prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ (Fig. 3B). However, this ratio was still higher than the one observed in untreated controls (P<0.05) (Fig. 3B). These changes in calpain activation closely correlated with changes in the generation of the 17-kDa tau fragment. Thus, a significant decrease in full-length tau and increase in the 17-kDa tau fragment levels were detected in whole cell extracts obtained from hippocampal neurons treated with preaggregated Aβ alone when compared to untreated controls or with cultures incubated in the presence of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone alone or in combination with preaggregated Aβ (Fig. 3A & B). Immunoblots reacted with calpain-1 antibody also showed the decrease of the calpain active forms (58-kDa) in whole cell extracts obtained from hippocampal neurons treated with testosterone or dihydrotestosterone prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ-treated hippocampal neurons treated only with the peptide (data not shown).On the other hand, no changes in calpain activation, as assessed by spectrin degradation, or in the appearance of the 17-kDa tau fragment were detected when cultured neurons were treated with estrogen prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ and compared to neurons incubated with preaggregated Aβ alone (Fig. 4). In contrast, Western blot analysis performed using an anti-active caspase-3 antibody showed that estrogen prevented the activation of caspase-3 induced by preaggregated Aβ (Fig. 5A & C). Quantitative analysis of immunoreactive bands showed a significant decrease in the levels of active caspase-3 in whole cell extracts prepared from hippocampal neurons cultured in the presence of estrogen plus Aβ when compared to the ones obtained from cells cultured in the presence of the peptide alone (Fig. 5A & C). These changes in active caspase-3 levels correlated with changes in caspase-3-cleaved tau levels as detected by a specific tau antibody (tau-C3) (Gamblin et al., 2003). Thus, a significant decrease in the caspase-3 truncated tau (~50 kDa) levels was detected in estrogen plus preaggregated Aβ-treated hippocampal neurons when compared to the ones incubated with the peptide alone (Fig. 5A & B). On the other hand, testosterone or dihydrotestosterone pretreatment did not block the activation of caspase-3 induced by Aβ or the generation of 50 kDa truncated tau as assessed by quantitative Western blot analysis using specific antibodies (Fig. 6).

Figure 3. Androgens blocked β-induced calpain activation and the generation of the 17-kDa tau fragment in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(A) Western blot analysis of the 17-kDa tau fragment and spectrin content in whole cell extracts prepared from 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons incubated with testosterone or dihydrotestosterone for 24 hours prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ. Tubulin immunoblots were used as loading controls (B & C). Quantitative analysis of changes in spectrin cleavage products (B) and 17-kDa tau fragment (C) in whole cell extracts obtained from neurons kept in culture under the experimental conditions described above. Densitometry values were normalized using full-length spectrin and full-length tau, respectively. Values are expressed as a percentage of the values obtained from Aβ-treated neurons, which were considered 100 %. Each number represents the mean ± S.E.M. from three different experiments. Differs from Aβ-treated neurons, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Figure 4. Estrogen failed to prevent Aβ-induced calpain activation and the generation of the 17-kDa tau fragment in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(A) Western blot analysis of the 17-kDa tau fragment and spectrin content in whole cell extracts prepared from 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons incubated with estrogen for 24 hours prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ. Tubulin immunoblots were used as loading controls (B & C). Quantitative analysis of changes in 17-kDa tau fragment (B) and spectrin cleavage products (C) in whole cell extracts obtained from neurons kept in culture under the experimental conditions described above. Densitometry values were normalized using full-length tau and full-length spectrin, respectively. Values are expressed as a percentage of the values obtained from Aβ-treated neurons, which were considered 100 %. Each number represents the mean ± S.E.M. from three different experiments. *Differs from Aβ-treated neurons, p<0.05.

Figure 5. Estrogen inhibited Aβ-induced caspase-3 activation and tau truncation in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(A) Western blot analysis of the 50-kDa truncated tau (tau C3) and active caspase-3 content in whole cell extracts prepared from 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons incubated with estrogen for 24 hours prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ. Tubulin immunoblots were used as loading controls (B & C). Quantitative analysis of changes in 50-kDa truncated tau (B) and active caspase-3 (C) in whole cell extracts obtained from neurons kept in culture under the experimental conditions described above. Densitometry values were normalized using full-length tau and total caspase-3, respectively. Values are expressed as a percentage of the values obtained from Aβ-treated neurons, which were considered 100 %. Each number represents the mean ± S.E.M. from three different experiments. *Differs from Aβ-treated neurons, p<0.05.

Figure 6. Androgens did not prevent the activation of caspase-3 and tau truncation induced by preaggregated Aβ in cultured hippocampal neurons.

(A) Western blot analysis of the 50-kDa truncated tau (tau C3) and active caspase-3 content in whole cell extracts prepared from 21 days in culture hippocampal neurons incubated with testosterone or dihydrotestosterone for 24 hours prior to the addition of preaggregated Aβ. Tubulin immunoblots were used as loading controls (B & C). Quantitative analysis of changes in 50-kDa truncated tau (B) and active caspase-3 (C) in whole cell extracts obtained from neurons kept in culture under the experimental conditions described above. Densitometry values were normalized using full-length tau and total caspase-3, respectively. Values are expressed as a percentage of the values obtained from Aβ-treated neurons, which were considered 100 %. Each number represents the mean ± SEM from three different experiments. *Differs from Aβ-treated neurons, p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

The results presented herein indicate that estrogen and testosterone differentially block Aβ-induced caspase-3 and calpain activation in hippocampal neurons. Furthermore, they suggest that these sex hormones prevent tau cleavage leading to the generation of toxic fragments. Collectively, our findings identify an alternative molecular mechanism by which estrogen and testosterone could attenuate neurite degeneration and cell death associated with the deposition of Aβ in central neurons.

Epidemiological studies have previously shown that estrogen and/or hormone replacement therapy could reduce the risk of AD, delay the onset of this disease, and improve cognitive functions, including verbal fluency and verbal memory, in postmenopausal women (Paganini-Hill and Henderson, 1996; Tang et al., 1996; Baldereschi et al., 1998; Brinton, 2001; Polo-Kantola and Erkkola, 2001). Much less is known about the role of testosterone in AD. However, data obtained recently suggest that testosterone replacement therapy also improved spatial memory in men with AD or mild cognitive impairment (Cherrier et al., 2005). Our results extended previous observations describing estrogen neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced toxicity in mature hippocampal neurons (Shah et al., 2003). They also provided evidence for a role of testosterone as a neuroprotective hormone against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in these neurons. In addition, our data indicated that testosterone rendered stronger neuroprotection against this peptide than estrogen. Testosterone could exert its effects acting through estrogen by aromatase conversion, or dihydrotestosterone by 5a-reductase conversion (Green and Simpkins, 2000). The potent testosterone neuroprotective effects against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity observed in our model system could then be the result of the simultaneous activation of both the estrogen and androgen pathways. In the case of the regulation of protease activity, the dual activation of these pathways seems unlikely in view of our results showing that testosterone and dihydrotestosterone inhibited calpain activation and the generation of the 17-kDa tau fragment, and not caspase-3 activation and tau truncation at amino acid 421 as estrogen did. Together, these data indicated that mainly an estrogen-independent pathway mediated the neuroprotective effects of testosterone involving the activation of calpain.

The complement of molecular mechanisms by which estrogen and/or testosterone exert their neuroprotective effects in hippocampal neurons is multifaceted and most likely include genomic and non-genomic pathways. Some of these mechanisms have already been identified. Based on numerous studies, it has been postulated that estrogen protects against Aβ-induced neurodegeneration by its antioxidant effects, regulating the metabolism of the amyloid precursor protein, favoring the uptake of Aβ by microglia, and/or altering the composition of the cytoskeleton (Goodman et al., 1996; Gridley et al., 1997; Li et al., 1997; Keller, 1997; Xu et al., 1998; Green and Simpkins, 2000; Honda et al., 2001; for a review see Brinton, 2001; Goodenough et al., 2003; Shah et al., 2003). In addition, estrogen protects against a variety of apoptosis-inducing agents such as staurosporine, Aβ, and hydrogen peroxide (Weaver et al., 1997; Honda et al., 2001; Negishi et al., 2003; Sur et al., 2003). Two mechanisms by which estrogen could prevent programmed cell death have been identified. Estrogen could prevent apoptosis increasing the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL in cultured hippocampal neurons (Pike, 1999). Alternatively, estrogen could reduce Aβ-induced apoptosis by interfering with a caspase-3-mediated pathway (this study, see also Jover et al., 2002; Celsi et al., 2004). Much less is known about the mechanisms by which testosterone protects central neurons against Aβ-induced neurite degeneration and/or apoptosis. One potential mechanism has already been described. This mechanism involved the reduction of Aβ secretion in cell culture (Gouras et al., 2000). However, this mechanism seems unlikely in our model system because Aβ was added to the culture medium at a higher concentration than the one that could be achieved through secretion by cultured neurons and also was added in a preaggregated more toxic state. On the other hand, testosterone inhibition of Aβ-induced calpain activation, as well as the effect of estrogen on the regulation of caspase-3 activation, strongly suggest that nongenomic pathways might mediate the regulatory effects of these hormones on the activation of proteases leading to tau cleavage. These effects may occur very rapidly via ion movement and/or initiation of signal transduction cascades, well-known mechanisms associated with steroid hormones (Betao, 1989; Falkenstein et al., 2000). The fact that estrogen and testosterone protected hippocampal neurons against Aβ-induced neurotoxicity not only when added to the culture medium 24 hours before the incubation with preaggregated Aβ but also when added only 2 hours prior to the addition of the peptide provided further support for the involvement of nongenomic pathways in these effects (Ferreira, unpublished observations).

Collectively, our results suggest an alternative mechanism by which estrogen and testosterone could protect mature neurons against Aβ-induced apoptosis and neurite degeneration. This mechanism involves the differential inhibition of the activation of calpain and caspase-3 leading to the generation of two tau-cleaved products with toxic functions. Direct evidence of a role of tau in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in central neurons has recently been obtained (Rapoport et al., 2002). This study showed that neurons expressing either mouse or human tau degenerated in the presence of preaggregated Aβ, while no signs of degeneration were detected in Aβ-treated tau-depleted neurons (Rapoport et al., 2002). The mechanisms by which this microtubule-associated protein mediates Aβ neurotoxicity remain poorly understood. However, posttranslational modifications of tau have been recognized as important players in the pathophysiology of AD (Kosik et al., 1986; Wood et al., 1986; Kondo et al., 1988; Parihar and Hemnani, 2004). As such, they have been extensively studied using cultured central neurons (Takashima et al., 1993; Ferreira et al., 1997; Alvarez et al., 1999; Ekinci et al., 1999; Rapoport and Ferreira, 2000). The majority of these studies have addressed the role of tau hyperphosphorylation in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. More recently, several studies have highlighted the importance of tau cleavage in this pathological process. Caspase-3-mediated tau cleavage, as well as that mediated by calpain, seemed to be early events in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and to precede tau hyperphosphorylation (Gamblin et al., 2003; Park and Ferreira, 2005). Caspase-3-truncated tau has been detected before the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and cell death (Ugolini et al., 1997; Rissman et al., 2004). In addition, it has been associated with apoptosis in several cell types (Fasulo et al., 2000; Chung et al., 2001; Gamblin et al., 2003). Aβ-induced calpain-mediated tau cleavage leading to the generation of the 17-kDa fragment was also detected before enhanced tau phosphorylation or neurite degeneration in cultured hippocampal neurons (Park and Ferreira, 2005). Moreover, it has been shown that the overexpression of this fragment induced neurite degeneration characterized by the formation of varicosity-bearing tortuous processes and retraction of these processes in hippocampal neurons cultured in the absence of Aβ (Park and Ferreira, 2005). How cleaved tau causes neuronal death and/or neuronal degeneration is not clear. One potential mechanism involves the generation of truncated tau forms that could assemble into filaments easily. The formation of tau filaments could then interfere with different cellular processes. This seems to be the case with caspase-3-mediated tau truncation (Gamblin et al., 2003). An alternative mechanism by which tau fragments could induce cell death has recently been reported (Amadoro et al., 2006). This study showed that N-terminal tau fragments could mediate neuronal death through the activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Amadoro et al., 2006). However, the mechanisms linking the expression of these tau fragments, NMDA receptors, and neuronal death have yet to be determined.

More studies will be needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms by which sex hormones prevent tau cleavage leading to neuronal death and/or degeneration induced by Aβ. Regardless, these observations lend further support the beneficial effects of estrogen and testosterone in the prevention of Aβ-induced toxicity in central neurons.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NIH/NS39080, Alzheimer’s Association IIRG, Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Northwestern University NIH AG13854 to A.F.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alvarez A, Toro R, Caceres A, Maccioni RB. Inhibition of tau phosphorylating protein kinase cdk5 prevents beta-amyloid-induced neuronal death. FEBS Lett. 1999;459:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadoro G, Ciotti MT, Costanzi M, Cestari V, Calissano P, Canu N. NMDA receptor mediates tau-induced neurotoxicity by calapin and ERK/MAPK activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2892–2897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511065103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldereschi M, Di Carlo A, Lepore V, Bracco L, Maggi S, Grigoletto F, Scarlato G, Amaducci L. Estrogen-replacement therapy and Alzheimer's disease in the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neurology. 1998;50:996–1002. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beato M. Gene regulation by steroid hormones. Cell. 1989;56:335–344. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottenstein J, Hayashi I, Hutchings S, Masui H, Mather J, McClure DB, Ohasa S, Rizzino A, Sato G, Serrero G, Wolfe R, Wu R. The growth of cells in serum-free hormone-supplemented media. Methods Enzymol. 1979;58:94–109. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(79)58127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinton RD. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of estrogen regulation of memory function and neuroprotection against Alzheimer's disease: recent insights and remaining challenges. Learn Mem. 2001;8:121–133. doi: 10.1101/lm.39601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celsi F, Ferri A, Casciati A, D'Ambrosi N, Rotilio G, Costa A, Volonte C, Carri MT. Overexpression of superoxide dismutase 1 protects against beta-amyloid peptide toxicity: effect of estrogen and copper chelators. Neurochem Int. 2004;44:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrier MM, Matsumoto AM, Amory JK, Asthana S, Bremner W, Peskind ER, Raskind MA, Craft S. Testosterone improves spatial memory in men with Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2005;64:2063–2068. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165995.98986.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CW, Song YH, Yoon WJ, et al. Proapoptotic effects of tau cleavage product generated by caspase-3. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:162–172. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czogalla A, Sikorski AF. Spectrin and calpain: a 'target' and a 'sniper' in the pathology of neuronal cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1913–1924. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci FJ, Malik KU, Shea TB. Activation of the L voltage-sensitive calcium channel by mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase following exposure of neuronal cells to beta-amyloid. MAP kinase mediates beta-amyloid-induced neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30322–30327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M. Multiple actions of steroid hormones: a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:513–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasulo L, Ugolini G, Visintin M, Bradbury A, Brancolini C, Versillo V, Novak M, Cattaneo A. the neuronal microtubule-associated tau is a substrate for caspase-3 and an effector of apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2000;75:624–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Busciglio J, Caceres A. Microtubule formation and neurite growth in cerebellar macroneurons which develop in vitro: evidence for the involvement of the microtubule-associated proteins, MAP-1a, HMW-MAP2 and Tau. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1989;49:215–228. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Lu Q, Orecchio L, Kosik KS. Selective phosphorylation of adult tau isoforms in mature hippocampal neurons exposed to fibrillar A beta. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1997;9:220–234. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1997.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamblin TC, Chen F, Zambrano A, Abraha A, Lagalwar S, Guillozet AL, Lu M, Fu Y, Garcia-Sierra F, LaPointe N, Miller R, Berry RW, Binder LI, Cryns VL. Caspase cleavage of tau: linking amyloid and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10032–10037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1630428100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough S, Schafer M, Behl C. Estrogen-induced cell signalling in a cellular model of Alzheimer's disease. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84:301–305. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman Y, Bruce AJ, Cheng B, Mattson MP. Estrogens attenuate and corticosterone exacerbates excitotoxicity, oxidative injury, and amyloid beta-peptide toxicity in hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1836–1844. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66051836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslin K, Banker GA. Rat hippocampal neurons in low-density culture. In: Banker G, Goslin K, editors. Culturing Nerve Cells. MIT; Cambridge, MA: 1991. pp. 251–283. [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Xu H, Gross RS, Greenfield JP, Hai B, Wang R, Greengard P. Testosterone reduces neuronal secretion of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1202–1205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Simpkins JW. Neuroprotective effects of estrogens: potential mechanisms of action. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PS, Bishop J, Simpkins JW. 17 alpha-estradiol exerts neuroprotective effects on SK-N-SH cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:511–515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00511.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley KE, Green PS, Simpkins JW. Low concentrations of estradiol reduce beta-amyloid (25–35)-induced toxicity, lipid peroxidation and glucose utilization in human SK-N-SH neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 1997;778:158–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley KE, Green PS, Simpkins JW. A novel, synergistic interaction between 17 beta-estradiol and glutathione in the protection of neurons against beta-amyloid 25-35-induced toxicity in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:874–880. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynspan F, Griffin WR, Cataldo A, Katayama S, Nixon RA. Active site-directed antibodies identify calpain II as an early-appearing and pervasive component of neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 1997;763:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J, le Q, Goodyer C, Gelfand M, Trifiro M, leBlanc A. Testosterone-mediated neuroprotection through the androgen receptor in human primary neurons. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1319–1326. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst E, Williams J, Budge M, Barnetson L, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Serum total testosterone is lower in men with Alzheimer's disease. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2001;22:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda K, Shimohama S, Sawada H, Kihara T, Nakamizo T, Shibasaki H, Akaike A. Nongenomic antiapoptotic signal transduction by estrogen in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2001;64:466–475. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jover T, Tanaka H, Calderone A, Oguro K, Bennett MV, Etgen AM, Zukin RS. Estrogen protects against global ischemia-induced neuronal death and prevents activation of apoptotic signaling cascades in the hippocampal CA1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2115–2124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02115.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawas C, Resnick S, Morrison A, Brookmeyer R, Corrada M, Zonderman A, Bacal C, Lingle DD, Metter E. A prospective study of estrogen replacement therapy and the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurology. 1997;48:1517–1521. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JN, Germeyer A, Begley JG, Mattson MP. 17Beta-estradiol attenuates oxidative impairment of synaptic Na+/K+-ATPase activity, glucose transport, and glutamate transport induced by amyloid beta-peptide and iron. J Neurosci Res. 1997;50:522–530. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19971115)50:4<522::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B, Vassar R, Ferreira A. Beta-amyloid-induced dynamin I depletion in hippocampal neurons: A potential mechanisms for early cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31746–31753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503259200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Bang OY, Jung MW, Ha SD, Hong HS, Huh K, Kim SU, Mook-Jung I. Neuroprotective effects of estrogen against beta-amyloid toxicity are mediated by estrogen receptors in cultured neuronal cells. Neurosci Lett. 2001;302:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo J, Honda T, Mori H, Hamada Y, Miura R, Ogawara M, Ihara Y. The carboxyl third of tau is tightly bound to paired helical filaments. Neuron. 1988;1:827–834. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik KS, Joachim CL, Selkoe DJ. Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4044–4048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Schwartz PE, Rissman EF. Distribution of estrogen receptor-beta-like immunoreactivity in rat forebrain. Neuroendocrinology. 1997;66:63–67. doi: 10.1159/000127221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, Kawas C, Blackman MR, Harman SM, Resnick SM. Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men. Neurology. 2004;62:188–193. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE. Androgens and aging. Maturitas. 2001;38:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00192-4. discussion 71–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi T, Ishii Y, Kyuwa S, Kuroda Y, Yoshikawa Y. Inhibition of staurosporine-induced neuronal cell death by bisphenol A and nonylphenol in primary cultured rat hippocampal and cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2003;353:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini-Hill A, Henderson VW. Estrogen replacement therapy and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2213–2217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parihar MS, Hemnani T. Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis and therapeutic interventions. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:456–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Ferreira A. The generation of a 17 kDa neurotoxic fragment: an alternative mechanism by which tau mediates beta-amyloid-induced neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5365–5375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1125-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ. Estrogen modulates neuronal Bcl-xL expression and beta-amyloid-induced apoptosis: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1552–1563. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike CJ. Testosterone attenuates β-amyloid toxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2001;919:160–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R. Alzheimer's disease and estrogen replacement therapy--where are we now? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80:679–682. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2001.080008679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport M, Ferreira A. PD98059 prevents neurite degeneration induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid in mature hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 2000;74:125–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport M, Dawson HN, Binder LI, Vitek MP, Ferreira A. Tau is essential to beta -amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092136199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman RA, Poon WW, Blurton-Jones M, Oddo S, Torp R, Vitek MP, LaFerla FM, Rohn TT, Cotman CW. Caspase-cleavage of tau is an early event in Alzheimer's disease tangle pathology. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:121–130. doi: 10.1172/JCI20640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario ER, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Pike CJ. Age-related testosterone depletion and the development of Alzheimer disease. Jama. 2004;292:1431–1432. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.12.1431-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Elce JS, Hamos JE, Nixon RA. Widespread activation of calcium-activated neutral proteinase (calpain) in the brain in Alzheimer disease: a potential molecular basis for neuronal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2628–2632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Cell biology of the amyloid beta-protein precursor and the mechanism of Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1994;10:373–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.10.110194.002105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah RD, Anderson KL, Rapoport M, Ferreira A. Estrogen-induced changes in the microtubular system correlate with a decreased susceptibility of aging neurons to beta amyloid neurotoxicity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siman R, Baudry M, Lynch G. Brain fodrin: substrate for calpain I, an endogenous calcium-activated protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:3572–3576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern EA, Bacskai BJ, Hickey GA, Attenello FJ, Lombardo JA, Hyman BT. Cortical synaptic integration in vivo is disrupted by amyloid-beta plaques. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4535–4540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0462-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur P, Sribnick EA, Wingrave JM, Nowak MW, Ray SK, Banik NL. Estrogen attenuates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in C6 glial cells. Brain Res. 2003;971:178–188. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, Noguchi K, Sato K, Hoshino T, Imahori K. Tau protein kinase I is essential for amyloid beta-protein-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7789–7793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Jacobs D, Stern Y, Marder K, Schofield P, Gurland B, Andrews H, Mayeux R. Effect of oestrogen during menopause on risk and age at onset of Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1996;348:429–432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T, Shimohama S, Kimura J, Shimizu K. m-Calpain (calcium-activated neutral proteinase) in Alzheimer's disease brains. Neurosci Lett. 1998;248:109–112. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini G, Cattaneo A, Novak M. Co-localization of truncated tau and DNA fragmentation in Alzheimer's Disease neurones. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3709–3712. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199712010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeranna, Kaji T, Boland B, Odrljin T, Mohan P, Basavarajappa BS, Peterhoff C, Cataldo A, Rudnicki A, Amin N, Li BS, Pant HC, Hungund BL, Arancio O, Nixon RA. Calpain mediates calcium-induced activation of the erk1,2 MAPK pathway and cytoskeletal phosphorylation in neurons: relevance to Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:795–805. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CE, Jr, Park-Chung M, Gibbs TT, Farb DH. 17beta-Estradiol protects against NMDA-induced excitotoxicity by direct inhibition of NMDA receptors. Brain Res. 1997;761:338–341. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JG, Mirra SS, Pollock NJ, Binder LI. Neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer disease share antigenic determinants with the axonal microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4040–4043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Gouras GK, Greenfield JP, Vincent B, Naslund J, Mazzarelli L, Fried G, Jovanovic JN, Seeger M, Relkin NR, Liao F, Checler F, Buxbaum JD, Chait BT, Thinakaran G, Sisodia SS, Wang R, Greengard P, Gandy S. Estrogen reduces neuronal generation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptides. Nat Med. 1998;4:447–451. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankner BA, Mesulam MM. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. beta-Amyloid and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1849–1857. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112263252605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Rubinow DR, Xaing G, Li BS, Chang YH, Maric D, Barker JL, Ma W. Estrogen protects against beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurons by activation of Akt. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1919–1923. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107030-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]