Abstract

Background and aims

PAP/HIP was first reported as an additional pancreatic secretory protein expressed during the acute phase of pancreatitis. It was shown in vitro to be anti‐apoptotic and anti‐inflammatory. This study aims to look at whether PAP/HIP plays the same role in vivo.

Methods

A model of caerulein‐induced pancreatitis was used to compare the outcome of pancreatitis in PAP/HIP−/− and wild‐type mice.

Results

PAP/HIP−/− mice showed the normal phenotype at birth and normal postnatal development. Caerulein‐induced pancreatic necrosis was, however, less severe in PAP/HIP−/− mice than in wild‐type mice, as judged by lower amylasemia and lipasemia levels and smaller areas of necrosis. On the contrary, pancreas from PAP/HIP−/− mice was more sensitive to apoptosis, in agreement with the anti‐apoptotic effect of PAP/HIP in vitro. Surprisingly, pancreatic inflammation was more extensive in PAP/HIP−/− mice, as judged from histological parameters, increased myeloperoxidase activity and increased pro‐inflammatory cytokine expression. This result, in apparent contradiction with the limited necrosis observed in these mice, is, however, in agreement with the anti‐inflammatory function previously reported in vitro for PAP/HIP. This is supported by the observation that activation of the STAT3/SOCS3 pathway was strongly decreased in the pancreas of PAP/HIP−/− mice and by the reversion of the apoptotic and inflammatory phenotypes upon administration of recombinant PAP/HIP to PAP/HIP−/− mice.

Conclusion

The anti‐apoptotic and anti‐inflammatory functions described in vitro for PAP/HIP have physiological relevance in the pancreas in vivo during caerulein‐induced pancreatitis.

The pancreatitis‐associated protein (PAP) was first reported by Keim and co‐workers1 in 1984 as an additional pancreatic secretory protein expressed during acute pancreatitis. It accounts for approximately 5% of the protein secreted during the acute phase and returns to almost undetectable levels when the pancreas has totally recovered.2 Although PAP was originally characterized in the pancreas, its expression was also observed in a variety of tissues, including epithelial cells of the small intestine,3 pituitary gland,4 uterus5 and motoneurons.6 PAP expression is upregulated in diseases such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis,7 colorectal cancer,8 hepatocellular cancer and cholangiocarcinoma.9,10 The primary structure of PAP was determined after cloning the corresponding messenger RNA from rat,11 mouse, in which it was called RegIIIβ12 and human pancreas.13 Concomitantly, Lasserre and colleagues10 found the same transcript overexpressed in several hepatocellular carcinomas and named the encoded protein HIP. Therefore, hereafter we will call this gene PAP/HIP.

PAP/HIP expression is induced in pancreatic acinar cells in response to several cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), interferon γ, interleukin (IL) 6 in combination with dexamethasone,14 oxidative stress inducers such as hydrogen peroxide or menadione15 and lipopolysaccharide.16 In addition to the pro‐inflammatory factors described above, IL10 17 and the IL10‐related cytokine IL2218 mediate in vitro and in vivo robust induction of PAP/HIP mRNA in pancreatic acinar cells. Finally, PAP/HIP is able to induce its own expression through a STAT3‐mediated pathway creating a positive feedback.17

The physiological role of PAP/HIP remains unclear, although several functions have been suggested. Data support its involvement in tissue regeneration and cell proliferation,6,19,20 whereas overexpression of PAP/HIP also increases resistance to apoptosis induced by oxidative stress15 or TNFα21 in pancreatic acinar cells, motoneurons22 and hepatocytes.20,23 Interestingly, several works also suggest that PAP/HIP could be an anti‐inflammatory factor.7,24,25,26 An anti‐inflammatory activity of PAP/HIP would be in agreement with its strong induction observed during the course of inflammatory diseases such as pancreatitis, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. In fact, recent data have shown that PAP/HIP is able to activate Jak kinase, which in turn phosphorylates STAT3, resulting in its nuclear translocation.17 Activated STAT3 triggers the expression of the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) gene. Once synthesized, SOCS3 binds the regulatory tyrosine located to the activation loop of Jak, blocking the access to the active site and preventing further phosphorylation. Therefore, the negative feedback mediated by SOCS3, which inhibits activation of the Jak/STAT3 cascade, seems to be a key regulatory element of the PAP/HIP anti‐inflammatory pathway.

Evidence that the stress protein PAP/HIP can be mitogenic, anti‐apoptotic and anti‐inflammatory, three functions involving distinct molecular mechanisms, implies that it could coordinate defence–repair activities upon cell injury. As a first step to test that hypothesis, we used a PAP/HIP‐deficient mouse model to obtain a deeper insight into the role of PAP/HIP in the exocrine pancreas during experimental pancreatitis.

Materials and methods

Induction of experimental pancreatitis

We used PAP/HIP−/− mice generated as previously reported.27 Pancreatitis was induced in 4‐month‐old PAP/HIP−/− and PAP/HIP+/+ mice weighing 20–24 g. Mice were obtained from heterozygous × heterozygous mating. After fasting for 18 hours with free access to water, the secretagogue caerulein (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, Missouri, USA) was administered as seven intraperitoneal injections of 50 μg/kg body weight at hourly intervals, as previously described.25 In other experiments, caerulein‐treated PAP/HIP−/− animals received an intravenous administration of recombinant PAP/HIP (purchased from Dynabio SA, Marseille, France) at time 0 (100 μg/kg body weight). All studies were performed in accordance with the European Union regulations for animal experiments.

Preparation of plasma and tissue samples

Mice were killed at several time intervals from 4 to 21 hours after the first intraperitoneal injection of caerulein. Whole heparinized blood samples were centrifuged at 4°C, and plasma was stored at −80°C for further studies. The pancreas was removed on ice, weighed, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

For myeloperoxidase assay, samples were macerated with 0.5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide in 50 mmol phosphate buffer pH 6.0. Homogenates were then disrupted for 30 s using a Labsonic (B Braun, Melsungen, Germany) sonicator at 20% power and submitted to three cycles of snap freezing in dry ice and thawing before a final 30 s sonication. Samples were incubated at 60°C for 2 hours and then spun down at 4000g for 12 min. Supernatants were collected for myeloperoxidase assay.

Biochemical assays

Amylase and lipase activities were determined with commercially available assays (Roche Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany). Myeloperoxidase was measured using 3,3′,5,5′‐tetramethylbenzidine as substrate as previously described.25 Enzyme activity was recorded at 630 nm. The assay mixture consisted of 20 μl supernatant, 10 μl tetramethylbenzidine (final concentration 1.6 mmol) dissolved in dimethylsulphoxide and 70 μl hydrogen peroxide (final concentration 3.0 mmol) diluted in 80 mmol phosphate buffer pH 5.4.

Quantitation of caerulein‐induced injuries

To evaluate necrosis after caerulein‐induced pancreatitis in the pancreas of PAP/HIP‐expressing and PAP/HIP‐deficient mice, formalin‐fixed samples were embedded in paraffin and 5 μm sections were stained with hematoxilin and eosin. Samples were coded before light microscopy examination and scored by three experienced morphologists. The intensity of necrosis was scored as the product of lesion severity (on a 0–3 scale) to their extension (in percentage of surface involved (1 = 0–25%; 2 = 25–50%; 3 = 50–75%; 4 = 75–100%) leading to a 0–12 scale. In a similar way, the intensity of inflammation was scored as the product of the degree of infiltration (on a 0–3 scale) to the extension of infiltration evaluated as above.

Semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Expressions of SOCS3, RegI, RegII, RegIIIα, PAP/HIP (RegIIIβ), RegIIIγ, TNFα, IL6 and IL1β mRNA were monitored by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR). Briefly, 1 μg total pancreatic RNA, purified as previously described,11 was used and the sequence amplified by the Life Technologies One Step RT–PCR System according to the manufacturer's protocol. For SOCS3, the forward primer was 5′‐CCTTTGACAAGCGGACTCTC‐3′ and the reverse primer 5′‐AGCTCACCAGCCTCATCTGT‐3′, for RegI the forward primer was 5′‐GCCTACAGCTCCTATTGTTAC‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐GGCCATAGGACAGTGAAGC‐3′, for RegII the forward primer was 5′‐CCTGTCATACAGCCAAGGCC‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐CCCAGAGTTCTGCACATCTGTTC, for RegIIIα the forward primer was 5′‐GCAGTCACCTTTGTCCTGAC‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐CTCCATTGGGTTGTTGACC‐3′, for PAP/HIP (RegIIIβ) the forward primer was 5′‐CCTGAAGAATATACCCTCCG‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐CCATGATGCTCTTCAAGACAAATTCG‐3′, for RegIIIγ the forward primer was 5′‐GGATCTGCAAGACAGACAAGATGC TTCCC‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐GGAGGGAAGGGCCAGAGAAGG‐3′, for TNFα the forward primer was 5′‐AGTCCGGGCAGGTCTACTTT‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐AAGCAAAAGAGGAGGCAACA‐3′, for IL6 the forward primer was 5′‐CCGGAGAGGAGACTTCACAG‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐GGAAATTGGGGTAGGAAGGA‐3′, for IL1β the forward primer was 5′‐TCATGGGATGATGATGATAACCTGCT‐3′ and the reverse primer was 5′‐CCCATACTTTAGGAAGACACGGAT‐3′, and for RL3, a housekeeping gene used as control, the forward primer was 5′‐GAAAGAAGTCGTGGAGGCTG‐3′ and the reverse primer 5′‐ATCTCATCCTGCCCAAACAC‐3′. RT–PCR products were resolved by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide.

Western blotting

Antibodies: Rabbit anti‐phosphotyrosine‐STAT3 (Tyr705) antibody was purchased from Cell Signalling Technology (Beverly, Massachusetts, USA). Rabbit antibody against poly(adenosine diphosphate‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) was from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Antibody against STAT3 was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California, USA). Monoclonal antibody against β‐actin was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis).

Whole pancreatic extracts: For Western blots, pancreas of mice were rapidly ground in liquid nitrogen. The resulting powder was reconstituted in ice‐cold solubilization buffer containing 50 mmol/l Tris/HCl (pH 8), 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1% Nonidet‐P40, 1 mmol/l phenyl‐methylsulphonyl fluoride and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (1/200) (Sigma). Samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 10 000g. Supernatants were recovered, and total amounts of protein were determined using the Bradford method.

Nuclear pancreatic extracts: To obtain nuclear extracts, pancreas was lysed using the nuclear extract kit from Active Motif (Carlsbad, California, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Total amounts of protein were determined as described above.

Sodium dodecylsulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting: Fifty micrograms of protein was submitted to 12% sodium dodecylsulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis then blotted following standard methods. Migration was calibrated using Bio‐Rad standard proteins (Hercules, California, USA) with markers covering a 7–240 kDa range. Non‐specific binding to the membrane was blocked by 5% bovine serum albumin in Tris‐buffered saline (TBS) for 1 hour at 4°C. Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti‐STAT3 antibody (1:500), anti‐PARP antibody (1:500), a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to phosphotyrosine‐STAT3 (1:1000) or a monoclonal anti β‐actin (1:1500) diluted in 5% bovine serum albumin. Membranes were this washed with TBS–0.1% Triton and incubated with a secondary goat–anti‐rabbit–horseradish peroxidase or goat–anti‐mouse–horseradish peroxidase antibody (1:3000) obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California, USA) diluted in 5% dry non‐fat milk in TBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Finally, membranes were washed with TBS–0.1% Triton, developed with the ECL‐detection system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), quickly dried and exposed to ECL film.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin‐embedded pancreas samples were deparaffinized and after blocking non‐specific binding sites, sections were incubated with anti‐active caspase 3 antibody (1:500; Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The sections were then incubated with a biotinylated‐linked antibody for 20 min and with peroxidase‐labeled streptavidin at room temperature for 20 min. The chromogen used for the colour reaction was 3‐amino‐9‐ethyl‐carbazole. The areas labelled by caspase 3 immunoreactivity were quantified using an Olympus BX61 automated microscope (10× objective) using a Samba 2050 image analyser (Samba Technologies, Meylan, France).

Densitometric analysis

ImageJ 1.32 software from http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/download.html was used to quantify intensities of the bands obtained in Western blots and RT–PCR experiments.

Statistical analysis

Data shown in the figures indicate the means ± SE. Differences between groups were compared using the non‐parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Asterisks in the figures indicate statistically significant differences (p<0.05).

Results

Expression of RegI, RegII, RegIIIα and RegIIIγ in PAP/HIP−/− mice

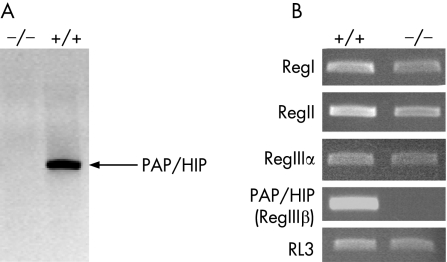

Before comparing PAP/HIP−/− and PAP/HIP+/+ mice during pancreatitis, we checked that their pancreatic weight as well as amylase, lipase and trypsinogen pancreatic contents were similar (not shown) and that during pancreatitis PAP/HIP was indeed expressed in wild‐type and not in PAP/HIP−/− mice (fig 1A). Also, because PAP/HIP (RegIIIβ) belongs to a family of five proteins whose functions could be similar, it was conceivable that the suppression of PAP/HIP expression induces, by a compensatory mechanism, the overexpression of other members. This had to be checked because such compensation should be taken into account when analyzing results involving PAP/HIP−/− mice. We assessed the expression of RegI, RegII, RegIIIα and RegIIIγ, in the pancreas of PAP/HIP−/− and PAP/HIP+/+ mice, after treatment with caerulein. As shown in figure 1B, no upregulation was observed in RegI, RegII and RegIIIα expressions, which were, on the contrary, slightly diminished. As expected, PAP/HIP (RegIIIβ) was not detected, nor RegIIIγ, whose expression does not occur in the pancreas.12

Figure 1 Expression of PAP/HIP family members in the pancreas of PAP/HIP+/+ and PAP/HIP−/− mice. A. Expression of PAP/HIP was analyzed by Western blotting, using a specific polyclonal antibody, in the pancreas of PAP/HIP+/+ and PAP/HIP−/− mice during acute pancreatitis. Expression is restricted to PAP/HIP+/+ mice, as expected. B. Expression of PAP/HIP family members in the pancreas of PAP/HIP+/+ and PAP/HIP−/− mice. Assessment of mRNA levels of RegI, RegII, RegIIIα and PAP/HIP (RegIIIβ) by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis of pancreatic RNA from PAP/HIP+/+ and PAP/HIP−/− mice, 9 hours after caerulein treatment. RL3 mRNA was used as a housekeeping control. Results from one representative mouse for each group are included. RegIIIγ could not be evidenced in PAP/HIP+/+, although the same primers could detect a transcript in intestinal RNA (not shown).

Caerulein‐induced pancreatic necrosis is more severe in wild‐type than in PAP/HIP‐deficient mice

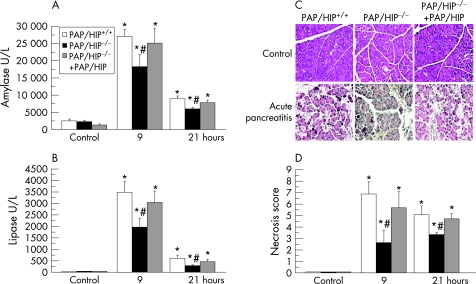

As previously described,28 wild‐type mice given intraperitoneal injections of the secretagogue caerulein at a supramaximal dose develop acute necrotizing pancreatitis. We compared the severities of caerulein‐induced pancreatitis in wild‐type and PAP/HIP−/− mice by measuring amylase and lipase levels in serum and by assessing the extent of acinar cell necrosis. As shown in figure 2, the induction of pancreatitis was followed by a time‐dependent increase in serum amylase and lipase levels. Amylasemia and lipasemia were, however, significantly higher in wild‐type than in PAP/HIP−/− mice, by 33% and 43%, respectively, suggesting that pancreatitis was more severe in wild‐type mice (fig 2). In the PAP/HIP−/− mice treated with recombinant PAP/HIP, serum levels of amylase and lipase were similar to those of wild‐type mice. Indeed, histological examination of pancreatic sections revealed that necrotic areas were more extended in wild‐type than in PAP/HIP−/− mice (fig 2).

Figure 2 Caerulein‐induced pancreatic necrosis is less severe in PAP/HIP−/− mice than in wild‐type mice. Plasmatic amylase (A) and lipase (B) levels were measured in control PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and PAP/HIP−/− treated with recombinant PAP/HIP mice at 9 and 21 hours after the first caerulein injection. (C) Representative images from control pancreas and pancreas after 9 hours of pancreatitis are shown. (D) Necrosis score of histological sections from control pancreas and pancreas after 9 and 21 hours after the induction of acute pancreatitis in PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and PAP/HIP−/− treated with recombinant PAP/HIP mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 8). #p<0.05 PAP/HIP−/− vs PAP/HIP+/+ mice. *p<0.05 vs respective control.

Pancreatic apoptosis in PAP/HIP‐deficient and wild‐type mice during caerulein‐induced pancreatitis

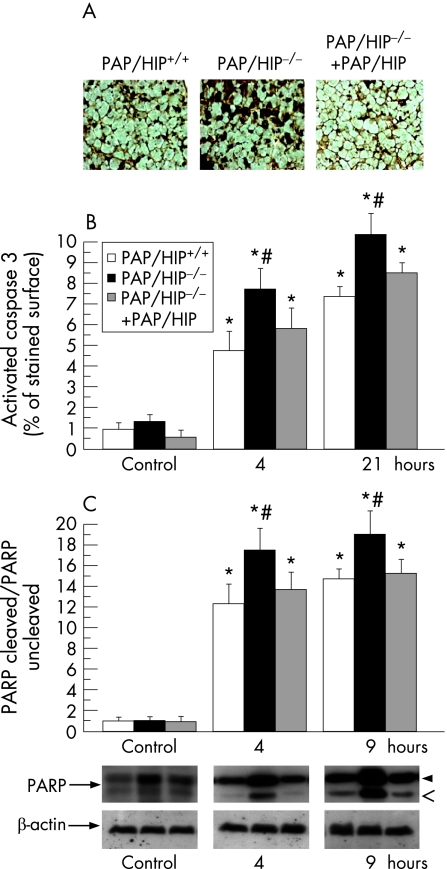

We compared the extent of pancreatic apoptosis in PAP/HIP−/− and wild‐type mice after the induction of pancreatitis by monitoring caspase 3 activity and PARP cleavage in pancreatic tissue. The percentage of cells showing caspase 3 activity was estimated by quantitative immunohistochemistry and the extent of PARP cleavage in tissue was assessed by Western blot. Significantly larger caspase 3‐labeled areas were observed in PAP/HIP−/− mouse pancreas, compared with wild‐type controls, revealing more abundant apoptosis in PAP/HIP−/− animals (fig 3). These areas were smaller when recombinant PAP/HIP was administered to PAP/HIP−/− mice before the induction of acute pancreatitis (fig 3). These findings were confirmed by the higher level of caspase‐specific PARP cleavage observed in PAP/HIP−/− mouse pancreas compared with wild‐type (fig 3). Again, that difference was almost completely abolished when PAP/HIP−/− mice were treated with recombinant PAP/HIP before starting pancreatitis induction (fig 3). These results indicate that, during caerulein‐induced pancreatitis, the pancreas is more sensitive to apoptosis in PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice, in agreement with the anti‐apoptotic effect attributed to PAP/HIP.15,20,21,22

Figure 3 Caerulein‐induced pancreatic induces more apoptosis in PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice. (A) Immunohistochemistry of active caspase 3 on pancreatic paraffin sections from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice after 4 and 9 hours of pancreatic induction. Representative images from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice 4 hours after the first caerulein injection are shown. (B) The graph shows the percentage of surface with active caspase 3‐positive staining. No staining was observed in the absence of primary antibody (data not shown). (C) Assessment of poly(adenosine diphosphate‐ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage by Western blot analysis in pancreatic homogenates from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and PAP/HIP−/− treated with recombinant PAP/HIP mice at 4 and 9 hours after caerulein injection. Upper band corresponds to uncleaved PARP (116 kDa) and lower band to the cleaved fragment (85 kDa). β‐Actin was used as loading control. The intensity of bands was measured and the represented values correspond to the (PARP cleaved/PARP uncleaved)/β‐actin ratio. Representative images of the results are shown (lower panel). Results are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 8). #p<0.05 PAP/HIP−/− vs PAP/HIP+/+ mice. *p<0.05 vs respective control.

During experimental acute pancreatitis, the pancreatic inflammatory response is more severe in PAP/HIP‐deficient than in wild‐type mice

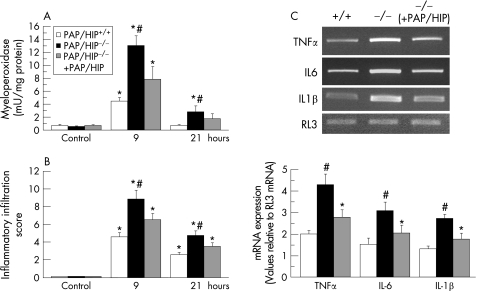

Contrary to apoptosis, the necrosis of pancreatic cells generates inflammation, as a result of the release of cell debris. Such inflammation is evidenced by polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocyte accumulation around the areas of tissue damage. To compare the extent of inflammation in PAP/HIP−/− and wild‐type mice upon the induction of pancreatitis, we assessed PMN leukocyte infiltration in the pancreas by monitoring the activity in tissue of myeloperoxidase, an enzyme specifically found in PMN leukocytes. On that basis, PMN leukocyte sequestration appeared significantly higher in PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice, but the increase was significantly reduced when mice were treated with recombinant PAP/HIP before the induction of pancreatitis (fig 4). Assessment of inflammation by quantitative histological analysis led to similar conclusions. During the course of pancreatitis, the inflammatory infiltrate (mainly neutrophils) was significantly more abundant in the pancreas of PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice and, again, that increase was more limited when PAP/HIP was administered before inducing pancreatitis (fig 4). Finally, expression of the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL6 and IL1β mRNAs were significantly higher in PAP/HIP−/− mice compared with PAP/HIP+/+ mice, and the expression of these cytokines was decreased after treating PAP/HIP−/− mice with recombinant PAP/HIP (fig 4). These results are, however, in agreement with the anti‐inflammatory function previously reported for PAP/HIP.17,24,25

Figure 4 Caerulein‐induced pancreatic inflammation is more severe in PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice. (A) Pancreatic myeloperoxidase activity was measured in the pancreas of control PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice 9 and 21 hours after caerulein injection. (B) The inflammatory cell infiltration score was quantified on histological sections from pancreas 0 (control), 9 and 21 hours after the induction of acute pancreatitis in PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 8). #p<0.05 PAP/HIP−/− vs PAP/HIP+/+ mice. *p<0.05 vs respective control. (C) Expression of tumour necrosis factor α, interleukin (IL) 6 and IL1β mRNA was assessed by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis in pancreatic RNA from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− mice and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice, 9 hours after caerulein treatment. RL3 mRNA was used as a housekeeping control. The intensity of bands was measured and the represented values correspond to the cytokine mRNA/RL3 mRNA ratio. Images from one representative mouse for each group are shown (upper panel). Results are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 5). #p<0.05 PAP/HIP−/− vs PAP/HIP+/+ mice. *p<0.05 vs respective control.

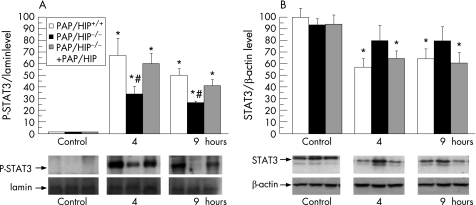

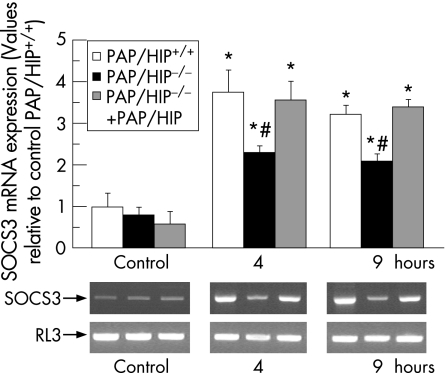

STAT3 activity and SOCS3 expression in the pancreas from PAP/HIP−/− mice

We compared wild‐type and PAP/HIP−/− mice to assess in vivo Jak/STAT3/SOCS3 activation by PAP/HIP. STAT3 is transiently activated in the pancreas with acute pancreatitis, as evidenced by Western blot of nuclear extracts from pancreatic cells (fig. 5). Interestingly, the phosphorylated (activated) STAT3 level was significantly higher in wild‐type than in PAP/HIP−/− mice (fig 5). Moreover, figure 5 shows that the induction of pancreatitis decreases the total STAT3 level in the pancreas of wild‐type mice. A smaller decrease was seen in the pancreas of PAP/HIP−/− mice. As a control, we monitored in the pancreas of these animals the concentration of SOCS3 mRNA, a STAT3‐specific target, which was actually found to be significantly higher in wild‐type than in PAP/HIP−/− mice (fig 6). In PAP/HIP−/− mice treated with recombinant PAP/HIP, STAT3 activation (fig 5) as well as SOCS3 mRNA expression (fig 6) reached values close to those found in wild‐type pancreas. These results support a role of PAP/HIP in activating the Jak/STAT3/SOCS3 anti‐inflammatory pathway in vivo, and confirm the results of our previous in‐vitro studies.17

Figure 5 STAT3 activation in PAP/HIP+/+ and PAP/HIP−/− mouse pancreas during caerulein‐induced acute pancreatitis. (A) Assessment of Tyr705‐phosphorylated STAT3 levels by Western blot analysis in nuclear pancreatic homogenates from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice, 4 and 9 hours after caerulein injection. Lamin b was used as nuclear extracts loading control. The intensity of bands was measured and the represented values correspond to the STAT3‐P/lamin b ratio. (B) Assessment of total STAT3 levels by Western blot analysis in pancreatic homogenates from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice, 4 and 9 hours after caerulein injection. β‐Actin was used as loading control. The intensity of bands was measured and the represented values correspond to the STAT3/β‐actin ratio. Representative images of the results are shown in each case (lower panels). Results are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 8). #p<0.05 PAP/HIP−/− vs PAP/HIP+/+ mice. *p<0.05 vs respective control.

Figure 6 SOCS3 expression in PAP/HIP+/+ and PAP/HIP−/− mouse pancreas during caerulein‐induced acute pancreatitis. Assessment of SOCS3 mRNA levels by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction analysis in pancreatic RNA from PAP/HIP+/+, PAP/HIP−/− and recombinant PAP/HIP‐treated PAP/HIP−/− mice, 4 and 9 hours after caerulein treatment. RL3 mRNA was used as a housekeeping control. The intensity of bands was measured and the represented values correspond to the ratio SOCS3/RL3. Representative images of the results are shown (lower panels). Results are expressed as mean ± SE (n = 8). #p<0.05 PAP/HIP−/− vs PAP/HIP+/+ mice. *p<0.05 vs respective control.

Discussion

PAP/HIP was first identified as an additional secretory protein, appearing in rat pancreatic juice after the induction of experimental pancreatitis.1 It belongs to a five‐member family of secretory proteins containing a C‐type lectin‐like domain linked to a short N‐terminal peptide.29 Besides the exocrine pancreas, PAP/HIP is expressed in several other organs such as the endocrine pancreas, the intestine, the pituitary, the uterus and the motoneuron, either constitutively or after induction by a stress. PAP/HIP can also appear in tumours from tissues such as the colon and liver in which the protein is not expressed in normal conditions.8,10 Several functions have been suggested for PAP/HIP, some of them being apparently unrelated.29 What makes the protein unique and especially interesting, however, is that it can be mitogenic,6,19,20 anti‐apoptotic15,20,21,22 and anti‐inflammatory,7,24,25,26 suggesting that PAP/HIP is a key regulatory factor. It is noteworthy that other members of the PAP/HIP family may have different functions. For example, the RegIIIγ isoform, which is expressed in Paneth cells but not in the pancreas, is bactericidal and may participate in the control of intestinal flora.30 Because data on the function of PAP/HIP were obtained on different tissues using various experimental models, in vivo or in vitro, their integration into a general scheme of PAP/HIP function remains difficult. To gain further insight into this problem we used a PAP/HIP−/− mouse model to assess in vivo the consequences of PAP/HIP deletion on the pancreas during acute pancreatitis.

Induction by supramaximal doses of caerulein was chosen as model of pancreatitis because it is easy to implement, reproducible with homogeneous distribution of the necrotic lesions in the pancreas, and is not lethal. In this model we found that pancreatic necrosis was less severe in PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice. Amylase and lipase serum levels, two specific markers of severity, were lower in PAP/HIP−/− animals, and histological examination revealed that necrotic areas were more extensive in wild‐type mice. These results strongly suggest that pancreatic cells are less sensitive to necrosis in PAP/HIP−/− than in wild‐type mice. In addition, treatment of PAP/HIP−/− mice with recombinant PAP/HIP was able to reverse this effect, as shown in figure 2. During acute pancreatitis, acinar cell death occurs by necrosis or by apoptosis.31 Large areas of necrosis are found in severe acute pancreatitis, whereas mild forms of the disease are associated with abundant apoptotic cells and reduced areas of necrosis, if any. It is generally accepted that when a tissue is submitted to aggression, apoptosis is triggered to prevent cells from undergoing necrosis, a “clean” death avoiding the massive release of cell debris that might generate a necrosis–inflammation–necrosis vicious circle.32,33 If the aggression is sufficiently strong, however, as in our model of caerulein‐induced pancreatitis when used in wild‐type animals, necrosis occurs before apoptosis takes place. The induction of apoptosis might therefore reduce the severity of experimental pancreatitis. This was indeed shown in a mouse model of caerulein‐induced acute pancreatitis32 and confirmed in a rat model of caerulein‐induced pancreatitis when apoptosis was induced by an extract of Artemisia asiatica.34 On the contrary, inhibition of apoptosis worsens the disease. For example, mice deficient in the Cx32 gene, which are resistant to crambene‐induced apoptosis, are more susceptible to acute pancreatitis than their wild‐type counterparts.35 Therefore, one explanation for the lower level of necrosis observed in PAP/HIP−/− mice could be that the absence of PAP/HIP anti‐apoptotic activity favours apoptosis. As a control, we monitored two markers of apoptosis, caspase‐dependent PARP cleavage and caspase 3 activation, in the pancreas of PAP/HIP−/− and wild‐type animals during pancreatitis. Both were significantly higher in PAP/HIP−/− mice, confirming that the absence of PAP/HIP favours apoptosis, in agreement with the anti‐apoptotic role of PAP/HIP previously demonstrated in vitro.15,20,21,22 Further confirmation was obtained by showing that the administration of recombinant PAP/HIP to PAP/HIP−/− mice partly restored an anti‐apoptotic activity, as judged by decreased caspase 3 activation and PARP cleavage.

Pancreatic necrosis generates an inflammatory response during acute pancreatitis whose intensity correlates with the severity of pancreatitis. Because necrosis was significantly less abundant in PAP/HIP−/− animals, we expected that they would also show less inflammation. This was not the case, as PMN leukocyte accumulation and pro‐inflammatory cytokine expression were increased in pancreas from PAP/HIP−/− mice. Again, the administration of recombinant PAP/HIP to PAP/HIP−/− mice could reverse the phenomenon, corroborating the anti‐inflammatory role of PAP/HIP in vivo, in agreement with in‐vitro data.7,17,25 In addition, the intensity of inflammation in the absence of PAP/HIP, although necrosis was limited, suggests that in physiological conditions the anti‐inflammatory activity of PAP/HIP is quite strong.

In‐vitro studies17 demonstrated that the anti‐inflammatory function of PAP/HIP involves the Jak/STAT3/SOCS3 pathway. STAT3 is a cytoplasmic factor that translocates into the nucleus after its phosphorylation by the Jak kinase. Once in the nucleus, the activated STAT3 triggers the transcription of several genes including SOCS3, which in turn inhibits the pro‐inflammatory cytokine cascade. To evaluate the situation in vivo, we monitored STAT3 activity and SOCS3 concentrations in the pancreas of wild‐type and PAP/HIP−/− mice. The level of the activated (phosphorylated) form of STAT3 and the concentration of SOCS3 mRNA were indeed significantly lower in PAP/HIP−/− animals, consistent with the absence of PAP/HIP in pancreatic cells. That some STAT3 activity remains in PAP/HIP−/− animals is not surprising because it can also be activated by other cytokines,36 growth factors37 or various stress agents.38

Altogether, these results show that the anti‐apoptotic and anti‐inflammatory functions described in vitro for PAP/HIP are also observed in vivo. Therefore, PAP/HIP appears to be a key factor in the pancreatic response to acute pancreatitis injury.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grant FIS PI050599 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and from INSERM. MG is the recipient of a post‐vert (INSERM) fellowship and EF‐P is the recipient of a Ramón y Cajal research contract.

Abbreviations

IL - interleukin

PAP -

pancreatitis‐associated protein -

PARP - poly(adenosine diphosphate‐ribose) polymerase

PMN - polymorphonuclear

RT–PCR - reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

TBS - Tris‐buffered saline

TNFα - tumour necrosis factor α

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Keim V, Rohr G, Stockert H G.et al An additional secretory protein in the rat pancreas. Digestion 198429242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keim V, Iovanna J L, Rohr G.et al Characterization of a rat pancreatic secretory protein associated with pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 1991100775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iovanna J L, Keim V, Bosshard A.et al PAP, a pancreatic secretory protein induced during acute pancreatitis, is expressed in rat intestine. Am J Physiol 1993265G611–G618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsumata N, Chakraborty C, Myal Y.et al Molecular cloning and expression of peptide 23, a growth hormone‐releasing hormone‐inducible pituitary protein. Endocrinology 19951361332–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty C, Vrontakis M, Molnar P.et al Expression of pituitary peptide 23 in the rat uterus: regulation by estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1995108149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Livesey F J, O'Brien J A, Li M.et al A Schwann cell mitogen accompanying regeneration of motor neurons. Nature 1997390614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gironella M, Iovanna J L, Sans M.et al Anti‐inflammatory effects of pancreatitis associated protein in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2005541244–1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rechreche H, Montalto G, Mallo G V.et al Pap, reg I alpha and reg I beta mRNAs are concomitantly up‐regulated during human colorectal carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer 199981688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christa L, Simon M T, Brezault‐Bonnet C.et al Hepatocarcinoma–intestine–pancreas/pancreatic associated protein (HIP/PAP) is expressed and secreted by proliferating ductules as well as by hepatocarcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma cells. Am J Pathol 19991551525–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasserre C, Christa L, Simon M T.et al A novel gene (HIP) activated in human primary liver cancer. Cancer Res 1992525089–5095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iovanna J, Orelle B, Keim V.et al Messenger RNA sequence and expression of rat pancreatitis‐associated protein, a lectin‐related protein overexpressed during acute experimental pancreatitis. J Biol Chem 199126624664–24669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narushima Y, Michiaki U, Nakagawara K.et al Structure, chromosomal localization and expression of mouse genes encoding type III Reg, RegIIIα, RegIIIβ, RegIIIγ. Gene 1997185159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orelle B, Keim V, Masciotra L.et al Human pancreatitis‐associated protein. Messenger RNA cloning and expression in pancreatic diseases. J Clin Invest 1992902284–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusetti N J, Ortiz E M, Mallo G V.et al Pancreatitis‐associated protein I (PAP I), an acute phase protein induced by cytokines. Identification of two functional interleukin‐6 response elements in the rat PAP I promoter region. J Biol Chem 199527022417–22421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortiz E M, Dusetti N J, Vasseur S.et al The pancreatitis‐associated protein is induced by free radicals in AR4‐2J cells and confers cell resistance to apoptosis. Gastroenterology 1998114808–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccaro M I, Calvo E L, Suburo A M.et al Lipopolysaccharide directly affects pancreatic acinar cells: implications on acute pancreatitis pathophysiology. Dig Dis Sci 200045915–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folch‐Puy E, Granell S, Dagorn J C.et al Pancreatitis‐associated protein I suppresses NF‐kappa B activation through a JAK/STAT‐mediated mechanism in epithelial cells. J Immunol 20061763774–3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aggarwal S, Xie M H, Maruoka M.et al Acinar cells of the pancreas are a target of interleukin‐22. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2001211047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moucadel V, Soubeyran P, Vasseur S.et al Cdx1 promotes cellular growth of epithelial intestinal cells through induction of the secretory protein PAP I. Eur J Cell Biol 200180156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon M T, Pauloin A, Normand G.et al HIP/PAP stimulates liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy and combines mitogenic and anti‐apoptotic functions through the PKA signaling pathway. FASEB J 2003171441–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malka D, Vasseur S, Bodeker H.et al Tumor necrosis factor alpha triggers antiapoptotic mechanisms in rat pancreatic cells through pancreatitis‐associated protein I activation. Gastroenterology 2000119816–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimune H, Vasseur S, Wiese S.et al Reg‐2 is a motoneuron neurotrophic factor and a signalling intermediate in the CNTF survival pathway. Nat Cell Biol 20002906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieu H T, Batteux F, Simon M T.et al HIP/PAP accelerates liver regeneration and protects against acetaminophen injury in mice. Hepatology 200542618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heller A, Fiedler F, Schmeck J.et al Pancreatitis‐associated protein protects the lung from leukocyte‐induced injury. Anesthesiology 1999911408–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasseur S, Folch‐Puy E, Hlouschek V.et al P8 improves pancreatic response to acute pancreatitis by enhancing the expression of the anti‐inflammatory protein pancreatitis‐associated protein I. J Biol Chem 20032797199–7207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang H, Kandil E, Lin Y Y.et al Targeted inhibition of gene expression of pancreatitis‐associated proteins exacerbates the severity of acute pancreatitis in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol 200439870–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieu H T, Simon M T, Nguyen‐Khoa T.et al Reg2 inactivation increases sensitivity to Fas hepatotoxicity and delays liver regeneration post‐hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology 2006441452–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willemer S, Elsasser H P, Adler G. Hormone‐induced pancreatitis. Eur Surg Res 19922429–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iovanna J L, Dagorn J C. The multifunctional family of secreted proteins containing a C‐type lectin‐like domain linked to a short N‐terminal peptide. Biochim Biophys Acta 200517238–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cash H L, Whitham C V, Behrendt C L.et al Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science 2006313(5790)1126–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaiser A M, Saluja A K, Sengupta A.et al Relationship between severity, necrosis, and apoptosis in five models of experimental acute pancreatitis. Am J Physiol 1995269C1295–C1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhatia M, Wallig M A, Hofbauer B.et al Induction of apoptosis in pancreatic acinar cells reduces the severity of acute pancreatitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998246476–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mareninova O A, Sung K F, Hong P.et al Cell death in pancreatitis: caspases protect from necrotizing pancreatitis. J Biol Chem 20062813370–3381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hahm K B, Kim J H, You B M.et al Induction of apoptosis with an extract of Artemisia asiatica attenuates the severity of cerulein‐induced pancreatitis in rats. Pancreas 199817153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frossard J L, Rubbia‐Brandt L, Wallig M A.et al Severe acute pancreatitis and reduced acinar cell apoptosis in the exocrine pancreas of mice deficient for the Cx32 gene. Gastroenterology 2003124481–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hebenstreit D, Horejs‐Hoeck J, Duschl A. JAK/STAT‐dependent gene regulation by cytokines. Drug News Perspect 200518243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Calo V, Migliavacca M, Bazan V.et al STAT proteins: from normal control of cellular events to tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol 2003197157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu H M, Zhi J L, Cui Y.et al Role of the JAK–STAT pathway in protection of hydrogen peroxide preconditioning against apoptosis induced by oxidative stress in PC12 cells. Apoptosis 200611931–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]