Coccidioidomycosis is usually localised in the eye either to the anterior or to the posterior segment, but only rarely to both.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 We present a case in which the initial infection involved the anterior segment, but was followed by extensive superficial retinal seeding after vitrectomy. Retinal involvement after vitrectomy raises the possibility of the anterior hyaloid face acting as a barrier to spread of the fungus posteriorly. A review of prior cases indicates that, in the absence of vitrectomy, retinal involvement does not occur in anterior segment coccidioidomycosis.

Case report

A 64‐year‐old man had been treated 3 years previously for iritis and secondary ocular hypertension with topical prednisolone acetate 1% and timolol 0.5%, with alleviation of symptoms. He presented with recurrence of similar symptoms that did not resolve with topical, retroseptal, and systemic corticosteroids and glaucoma drugs. A detailed systemic evaluation was negative.

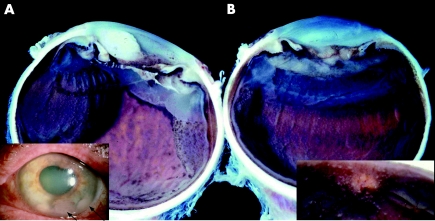

On examination, the right eye was unremarkable. Visual acuity of the left eye was perception of hand motion at 5 feet. Keratic precipitates and a white mass in the anterior chamber were seen (fig 1A, inset). An iris biopsy and anterior chamber aspiration showed numerous spherules.

Figure 1 The present case (Mondino–Glasgow–Holland). (A, B) Macrophotograph of the enucleated eye showing multiple rows of superficial granulomata lying on the surface of the retina. The inset in (A) shows hypopyon, iris synechiae and large fluffy masses in the inferior portion of the anterior chamber. The inset in (B) shows numerous granulomata coating the surface of the optic nerve head.

After treatment with oral fluconazole, intravenous amphotericin B, pars plana vitrectomy and lensectomy, the vitreous humor, retina and choroid appeared normal, but an infiltrate reformed in the anterior chamber soon after. Tissue plasminogen activator and intracameral amphotericin B were given, followed by another pars plana vitrectomy. At 1 month after the second vitrectomy, the eye was enucleated for intractable pain.

Examination of the eye showed granulomata with spherules on the retinal surface (fig 1B, inset), posterior chamber cornea, iris, ciliary body, and in the vitreous space (fig 1).

Comment

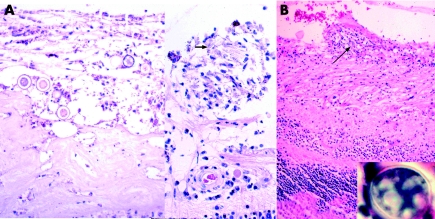

This case shows that retinal seeding may follow vitrectomy for anterior segment coccidioidomycosis. There are only two other reports of vitrectomy for anterior segment coccidioidomycosis.1,8,9 In each case, the eye was enucleated within weeks of the vitrectomy.1,9 Pathological sections from both cases were reviewed. One of the cases was subsequently shown to have superficial seeding of the retina after vitrectomy.9,10 The other was reported from our files and showed a tractional retinal detachment with granulomatous inflammation and adjacent cysts, but with no direct retinal involvement (fig 2B).1

Figure 2 (A) Right, photomicrograph of a retinal surface granuloma with a collapsed spherule, arrow (haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×300), left, numerous spherules lying on the extensive anterior fibrous tissue, proliferative vitreoretinopathy (haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×300). (B) Photomicrograph from the case published by Stone et al.1 The patient was a 26‐year‐old man with anterior segment coccidioidomycosis. After vitrectomy, there was evidence of posterior involvement, and the eye was subsequently enucleated. Illustrated is a granuloma on the surface of the retina (haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×120). The inset in (B) shows a spherule of coccidioidomycosis (haematoxylin and eosin, original magnification ×400).

The prognosis for anterior segment coccidioidomycosis is poor. Of the 10 histologically proved cases, seven did not have vitrectomy. Four of these seven cases were not enucleated and at least two retained vision.1,4,11,12 None of these four eyes had evidence of posterior segment involvement after treatment. In contrast, all three eyes that underwent vitrectomy were enucleated within months of the procedure, despite the extended course of the disease before the operation in two of the cases. The histological findings of superficial retinal involvement in our case suggest spread from the vitreous. Vitrectomy may be a factor in the dissemination of Coccidioides immitis to the posterior segment from infection of anterior tissues. Corticosteroid treatment did not seem to be an important factor, as it was initiated in four of the cases without vitrectomy, of which no evidence of posterior segment involvement was noticed. We hypothesise that vitrectomy disrupts the anterior hyaloid, thereby permitting spherules accumulated between the lens and anterior hyaloid (Berger space) to seed the posterior segment. We are uncertain of the role of vitrectomy in producing disease in the two cases where posterior infection may have followed vitrectomy, but clearly there was no improvement after vitrectomy. Taken together, the findings suggest that the anterior hyaloid may present a barrier to the spread of organisms, and that vitrectomy should be avoided in infection of C immitis that is confined to the anterior segment.

References

- 1.Moorthy R S, Rao N A, Sidikaro Y.et al Coccidioidomycosis iridocyclitis. Ophthalmology 19941011923–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glasgow B J, Brown H H, Foos R Y. Miliary retinitis in coccidioidomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 198710424–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zakka K A, Foos R Y, Brown W J. Intraocular coccidioidomycosis. Surv Ophthalmol 197822313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pettit T H, Learn R N, Foos R Y. Intraocular coccidioidomycosis. Arch Ophthalmol 196777655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foos R Y, Zakka K A. Coccidioidomycosis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, eds. Ocular infection and immunity. St Louis: Mosby‐Yearbook Inc, 19961430–1436.

- 6.Bell R, Font R L. Granulomatous anterior uveitis caused by Coccidioides immitis. Am J Ophthalmol 19727493–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown W C, Kellenberger R E, Hudson K E. Granulomatous uveitis associated with disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 195845102–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodenbiker H T, Ganley J P. Ocular coccidioidomycosis. Surv Ophthalmol 198024263–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone J L, Kalina R E. Ocular coccidioidomycosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1993116249–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gusack S V.Proceedings of the Human Pathology Society 1995. Salt Lake City, UT: Michael Hogan Eye Pathology Society 1995

- 11.Cunningham E T, Jr, Seiff S R, Berger T G.et al Intraocular coccidioidomycosis diagnosed by skin biopsy. Arch Ophthalmol 1998116674–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler J E, Binder P S, Paul T O.et al Metastatic coccidioidal endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 197896689–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]