Abstract

Aims

To investigate the expression of the hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α (HIF‐1α) and the protein products of its target genes vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), erythropoietin (Epo) and angiopoietins (Angs), and the antiangiogenic pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF) in proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) epiretinal membranes.

Methods

Sixteen membranes were studied by immunohistochemical techniques.

Results

Vascular endothelial cells expressed HIF‐1α, Ang‐2 and VEGF in 15 (93.75%), 6 (37.5%) and 9 (56.25%) membranes, respectively. There was no immunoreactivity for Epo, Ang‐1 and PEDF. There were significant correlations between the number of blood vessels expressing the panendothelial marker CD34 and the numbers of blood vessels expressing HIF‐1α (r = 0.554; p = 0.026), Ang‐2 (r = 0.830; p<0.001) and VEGF (r = 0.743; p = 0.001). The numbers of blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 and VEGF in active membranes were higher than that in inactive membranes (p = 0.015 and 0.028, respectively).

Conclusions

HIF‐1α, Ang‐2 and VEGF may play an important role in the pathogenesis of PDR. The findings suggest an adverse angiogenic milieu in PDR epiretinal membranes favouring aberrant neovascularisation and endothelial abnormalities.

Pathological growth of new blood vessels is the common final pathway in proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), and often leads to catastrophic loss of vision due to vitreous haemorrhage and/or tractional retinal detachment. In diabetic retinopathy, hypoxia seems to be the primary stimulus for neovascularisation by upregulating the production of angiogenic stimulators and by reducing the production of angiogenic inhibitors, disturbing the balance between the positive and negative regulators of angiogenesis. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) promotes angiogenesis, mediating endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation.1 Pigment epithelium‐derived factor (PEDF), by contrast, has been shown to be a highly effective inhibitor of angiogenesis, as it specifically inhibits the migration of endothelial cells.2 Increased intraocular levels of the angiogenic VEGF3,4 and decreased intraocular levels of the antiangiogenic PEDF5 in patients with PDR have been demonstrated previously. In addition, strong evidence indicates that chronic, low‐grade subclinical inflammation is implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy.6

All the hypoxia‐dependent events in cells seem to share a common denominator: hypoxia‐inducible factor (HIF)‐1, which is a heterodimric transcription factor. HIF‐1 is composed of HIF‐1α and HIF‐1β subunits, both of which are members of the basic helix–loop–helix–PAS family of proteins. Although the β‐subunit protein is constitutively expressed, the stability of the α‐subunit and its transcriptional activity are precisely controlled by the intracellular oxygen concentration. Under normoxia, the level of HIF‐1α protein is kept low through rapid ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation. In cells under hypoxia, the ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of HIF‐1α protein is suppressed, resulting in accumulation of the protein to form an active complex with HIF‐1β.7,8,9 Under hypoxic conditions, HIF‐1 triggers the activation of a large number of gene‐encoding proteins, such as VEGF, erythropoietin (Epo) and angiopoietins (Angs), that regulate angiogenesis.10,11,12,13

The glycoprotein Epo hormone is produced in the kidney and liver in response to hypoxia. It circulates in the plasma and binds to receptors specifically expressed on erythroid progenitor and precursor cells, enabling them to proliferate and differentiate into red blood cells.14 Recent studies demonstrated that erythropoietin shows angiogenic activity on vascular endothelial cells.15,16

Ang‐1 and Ang‐2 have been identified as ligands for Tie 2, which is a receptor tyrosine kinase specifically expressed on endothelial cells. Ang‐1 binds to Tie 2 and stabilises mature vessels by promoting interactions between endothelial cells and their surrounding extracellular matrix and support cells. In addition, Ang‐1 limits the permeability‐inducing effects of VEGF. Ang‐1 is widely expressed in adult tissues and production of Ang‐1 inhibits angiogenesis because of this stabilising effect. Ang‐2, expressed at sites of vascular remodelling, competitively binds to Tie 2 and antagonises the stabilising action of Ang‐1, which results in destabilisation of vessels. These destabilised vessels may undergo regression in the absence of VEGF, but may undergo angiogenic changes in the presence of VEGF.17,18

Because hypoxia, a central pathogenic stimulus in PDR, induces HIF‐1α that can induce the angiogenic molecules VEGF, Epo and Angs, we investigated the expression of these proteins in PDR epiretinal membranes. In addition, we studied the expression of PEDF and the correlation between the number of leucocytes and the expression of angiogenic factors in PDR membranes. The levels of vascularisation and proliferative activity in PDR membranes were determined by immunodetection of the panendothelial marker CD34 and the proliferating cell marker Ki‐67.

Methods

Epiretinal membrane specimens

Epiretinal membranes were obtained from 16 patients with PDR during pars‐plana vitrectomy. Membranes were fixed in 10% formalin solution and embedded in paraffin wax. The clinical ocular findings were graded at the time of vitrectomy for the presence or absence of patent new vessels on the retina or optic disc. Patients with active PDR were graded as such on the basis of the presence (active PDR) or the absence (inactive PDR) of visible patent new vessels on the retina or optic disc. Active PDR was present in seven patients. The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Research Centre, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Immunohistochemical staining

Endogenous peroxidase was abolished with 2% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 min, and non‐specific background staining was blocked by incubating the sections for 5 min in normal swine serum. For Epo (N‐19), VEGF and Ki‐67 detection, antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections in 10 mM Tris‐EDTA buffer (pH 9) for 30 min. For CD34, CD45, Ang‐1 and Ang‐2 detection, antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6) for 30 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with the monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies listed in table 1. For CD34, HIF‐1α, Epo (H‐162), VEGF, PEDF and Ki‐67 immunohistochemistry, the sections were incubated for 30 min with goat anti‐rabbit or anti‐mouse immunoglobulins conjugated to peroxidase‐labelled dextran polymer (EnVision, Dako, Carpinteria, California, USA). For Ang‐1, Ang‐2 and Epo (N‐19) immunohistochemistry, the sections were incubated for 30 min with the biotinylated secondary antibody and reacted with the avidin‐biotinylated peroxidase complex (Dako). The reaction product was visualised by incubation for 10 min in 0.05 M acetate buffer at pH 4.9, containing 0.05% 3‐amino‐9‐ethylcarbazole (Sigma‐Aldrich, Bornem, Belgium) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide, resulting in bright‐red immunoreactive sites. The slides were faintly counterstained with Harris haematoxylin.

Table 1 Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies used in the study.

| Primary antibody | Dilution | Incubation time (min) | Source* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti‐CD34 (Clone My 10; mc) | 1/10 | 60 | BD Biosciences |

| Anti‐Ki‐67 (Clone MIB‐1; mc) | 1/100 | 60 | BioGenex |

| Anti‐CD45 (Clones 2B11 and PD7/26; mc) | 1/50 | 30 | Dako |

| Anti‐HIF‐1α (Clone ESEE122; mc) | 1/1000 | 60 | Abcam |

| Anti‐Epo (N‐19): SC‐1310 (pc) | 1/20 | 60 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Anti‐Epo (H‐162): SC‐7956 (pc) | 1/50 | 60 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Anti‐VEGF (A‐20): SC‐152 | 1/100 | 60 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Anti‐Ang‐1 (N‐18): SC‐6319 | 1/50 | 60 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Anti‐Ang‐2 (N‐18): SC‐7016 | 1/50 | 60 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

| Anti‐PEDF (H‐125): SC‐25594 | 1/50 | 60 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology |

Ang, angiopoietin; Epo, erythropoietin; HIF‐1α, hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α; mc, monoclonal; pc, polyclonal; PEDF, pigment epithelium‐derived factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

*Location of manufacturers: BD Biosciences, San Jose, California, USA; BioGenex, San Ramon, California, USA; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA.

Omission or substitution of the primary antibody with an irrelevant antibody of the same species and staining with chromogen alone were used as negative controls. Sections from patients with colorectal carcinoma and breast cancer were used as positive controls.

Double immunohistochemistry

To confirm the phenotype of cells expressing HIF‐1α, sequential double immunohistochemistry was performed. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6) for 30 min. The sections were incubated with anti‐HIF‐1α monoclonal antibody. Subsequently, the slides were incubated for 30 min with EnVision, peroxidase, mouse (Dako). The reaction product was visualised by incubation for 10 min in 0.05 M of acetate buffer at pH 4.9, containing 0.05% 3‐amino‐9‐ethylcarbazole (Sigma‐Aldrich) and 0.01% hydrogen peroxide, resulting in red immunoreactive sites. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with anti‐CD34 monoclonal antibody. The slides were then incubated for 30 min with EnVision, alkaline phosphatase, mouse (Dako). The blue reaction product was developed using 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indoxyl phosphate and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (Dako) for 30 min.

Quantitation

Blood vessels and cells were counted in five representative fields, using an eyepiece‐calibrated grid with ×40 magnification. With this magnification and calibration, the blood vessels and cells present in an area of 0.33×0.22 mm2 were counted. Data were expressed as mean (SD) values and analysed by the Mann–Whitney test. Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed to investigate the linear relationship between the variables investigated. A p value <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

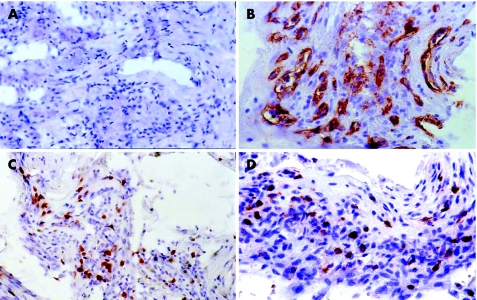

There was no staining in the negative control slides (fig 1A). All membranes showed blood vessels positive for the panendothelial marker CD34 (fig 1B), with a mean (SD; range) number of 34.4 (16.1;12–83). Nuclear immunoreactivity for the proliferating cell marker Ki‐67 (fig 1C) was present in 9 (56.25%) membranes, with a mean (SD; range) number of 22.2 (37.5; 0–114). Immunoreactivity for cells expressing the leucocyte common antigen CD45 (fig 1D) was present in 15 (93.75%) membranes, with a mean (SD; range) number of 47.2 (41.5; 0–125).

Figure 1 Proliferative diabetic retinopathy epiretinal membranes. (A) Negative control slide that was treated identically with an irrelevant antibody showing no labelling (original magnification ×25). (B) Immunohistochemical staining for CD34 showing blood vessels positive for CD34 (original magnification ×40). (C) Immunohistochemical staining for Ki‐67 showing nuclear immunoreactivity in proliferating cells (original magnification ×40). (D) Immunohistochemical staining for CD45 showing membranous immunoreactivity on leucocytes (original magnification ×40).

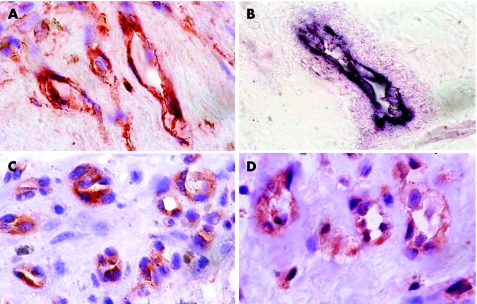

Immunoreactivity for HIF‐1α was noted on vascular endothelial cells (fig 2A) in 15 (93.75%) specimens, with a mean (SD; range) number of 20.7 (13.7; 0–50). Double immunohistochemistry confirmed that HIF‐1α‐positive cells were CD34‐positive vascular endothelial cells (fig 2B). Immunoreactivity for Ang‐2 was present on vascular endothelial cells (fig 2C) in 6 (37.5%) membranes, with a mean (SD; range) number of 7.8 (17.1; 0–69). Immunoreactivity for VEGF was noted on vascular endothelial cells (fig 2D) in 9 (56.25%) membranes, with a mean (SD; range) number of 9.6 (12.8; 0–42). VEGF immunoreactivity was also noted in pigmented and non‐pigmented cells outside blood vessels. VEGF and Ang‐2 were colocalised on vascular endothelial cells, particularly on those in highly vascularised regions. There was no immunoreactivity for Epo, Ang‐1 and PEDF.

Figure 2 Proliferative diabetic retinopathy epiretinal membranes. (A) Immunohistochemical staining for hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α showing immunoreactivity on vascular endothelial cells (original magnification ×100). (B) Double immunohistochemistry staining for hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α (red) and CD34 (blue) showing hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α‐positive vascular endothelial cells coexpressing CD34. No counterstain was applied (original magnification ×100). (C) Immunohistochemical staining for angiopoietin‐2 showing immunoreactivity on vascular endothelial cells (original magnification ×100). (D) Immunohistochemical staining for vascular endothelial growth factor showing immunoreactivity on vascular endothelial cells (original magnification ×100).

The numbers of blood vessels expressing CD34, Ang‐2 and VEGF, cells expressing Ki‐67 and leucocytes expressing CD45 were significantly higher in active membranes than in inactive membranes (table 2). Table 3 shows Pearson's correlation coefficients between the numbers of the studied variables. The number of blood vessels expressing CD34 correlated significantly with the number of cells expressing Ki‐67, the number of leucocytes expressing CD45, and the numbers of blood vessels expressing HIF‐1α, Ang‐2 and VEGF. The number of cells expressing Ki‐67 correlated significantly with the number of leucocytes expressing CD45 and the numbers of blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 and VEGF. The number of leucocytes expressing CD45 correlated significantly with the numbers of blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 and VEGF. The number of blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 correlated significantly with the number of blood vessels expressing VEGF.

Table 2 Mean (SD) numbers in relation to type of proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

| Variable | Active PDR (n = 7) | Inactive PDR (n = 9) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood vessels expressing CD34 | 44.0 (17.9) | 27.0 (11.7) | 0.0386† |

| Cells expressing Ki‐67 | 49.0 (47.6) | 1.3 (2.2) | 0.0150† |

| Leucocytes expressing CD45 | 77.1 (46.7) | 23.9 (20.4) | 0.0497† |

| Blood vessels expressing HIF‐1α | 17.7 (16.8) | 23.0 (12.2) | 0.3401 |

| Blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 | 16.6 (24.6) | 0.9 (2.7) | 0.0149† |

| Blood vessels expressing VEGF | 18.3 (16.1) | 2.8 (4.1) | 0.0275† |

Ang, angiopoietin; HIF‐1α, hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

*Mann–Whitney test.

†Statistically significant at 5% level of significance.

Table 3 Pearson's correlation coefficients.

| Blood vessels expressing CD34 | Cells expressing Ki‐67 | Leucocytes expressing CD45 | Blood vessels expressing HIF‐1α | Blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells expressing Ki‐67 | 0.715, 0.002 | ||||

| Leucocytes expressing CD45 | 0.591, 0.016 | 0.828, <0.001 | |||

| Blood vessels expressing HIF‐1α | 0.554, 0.026 | 0.201, 0.457 | 0.039, 0.886 | ||

| Blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 | 0.830, <0.001 | 0.811, <0.001 | 0.533, 0.034 | 0.497, 0.050 | |

| Blood vessels expressing VEGF | 0.743, 0.001 | 0.924, <0.001 | 0.806, <0.001 | 0.201, 0.455 | 0.850, <0.001 |

Ang, angiopoietin; HIF‐1α, hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

The cell where the row and column meet shows the correlation coefficient (r) and the p value, respectively, for the corresponding two variables.

Discussion

There were four important findings in the present study: (1) PDR membranes showed immunoreactivity for HIF‐1α, Ang‐2 and VEGF on vascular endothelial cells, whereas there was no immunoreactivity for Epo, Ang‐1 and PEDF; (2) there were significant correlations between the number of blood vessels expressing the panendothelial marker CD34 and the numbers of blood vessels expressing HIF‐1α, Ang‐2 and VEGF; (3) the numbers of blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 and VEGF correlated significantly, and were significantly higher in active membranes than in inactive membranes; and (4) there were significant correlations between the number of leucocytes and the numbers of blood vessels expressing Ang‐2 and VEGF.

HIF‐1 mediates the angiogenic response to hypoxia by upregulating the expression of multiple angiogenic factors.10,11,12,13 Overexpression of HIF‐1α in tumour tissues has been correlated with increased tumour angiogenesis, aggressive tumour growth and poor patient prognosis.19,20,21,22 In the present study, we demonstrated that HIF‐1α was specifically localised in vascular endothelial cells in PDR membranes. Our observations are consistent with previous reports showing that exposure to hypoxia induced a significant increase of HIF‐1α protein expression in vascular endothelial cells in vitro23,24 and in vivo.25 In vitro studies demonstrated that direct infection of vascular endothelial cells with Ad2/HIF‐1α/VP16 promotes endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation that was attributable to increased levels of VEGF and Ang‐2, but not Ang‐1. It was also demonstrated that HIF‐1 mediated the hypoxic upregulation of VEGF and Ang‐2 in vascular endothelial cells.13 These findings suggest that HIF‐1α is involved in angiogenesis in PDR membranes. Further evidence to support that HIF‐1α is associated with diabetes comes from Chavez et al,26 who demonstrated increased expression of HIF‐1α in the nerves of rats with diabetes.

Experimental studies demonstrated that VEGF and Ang‐2 contribute cooperatively in angiogenesis. Hypoxia upregulates VEGF and Ang‐2 in vascular endothelial cells in in vivo and in vitro systems.27 Hypoxia and VEGF directly increase Ang‐2 expression in endothelial cells.28 By contrast, Ang‐1 responds to neither of these stimuli.27,28 In the presence of endogenous VEGF, Ang‐2 promotes proliferation and migration of endothelial cells and stimulates sprouting of new blood vessels. By contrast, Ang‐2 promotes endothelial cell death and vessel regression if the activity of endogenous VEGF is inhibited.18,29 Consistent with this view, several studies showed a significant correlation between VEGF and Ang‐2 expression in various tumours. Furthermore, increased VEGF and Ang‐2 expression was significantly correlated with aggressive angiogenesis and poor prognosis.30,31,32 Our findings are in agreement with previous reports that demonstrated VEGF and Ang‐2 expression by vascular endothelial cells in fibrovascular membranes from patients with retinopathy of prematurity33 and patients with PDR.34 Ang‐1 was not generally observed, or was weakly expressed in these specimens.33,34 In addition, VEGF and Ang‐2 were upregulated in the retina of rats with diabetes, whereas Ang‐1 was similar between control rats with diabetes and those without diabetes.35 Our findings are also consistent with a previous study that demonstrated increased levels of VEGF and Ang‐2 that correlated significantly in the vitreous samples from patients with PDR.36

Strong evidence indicates that chronic, low‐grade subclinical inflammation is implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic retinopathy is associated with leucocyte recruitment and adhesion to the retinal vasculature, findings that correlate with the increased expression of retinal intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1) and CD18.6 Recently, Lemieux et al37 demonstrated the proinflammatory activities of Ang‐2 to mediate endothelial P‐selectin translocation and neutrophil adhesion onto activated endothelial cells. VEGF was also found to induce retinal ICAM‐1 expression and initiate early diabetic retinal leucocyte adhesion in vivo.38 In the present study, we demonstrated that the numbers of blood vessels expressing VEGF and Ang‐2 in PDR membranes correlated significantly with the number of leucocytes. Our findings confirm the capacity of VEGF and Ang‐2 to modulate proinflammatory activities in diabetic membranes. Ang‐1, by contrast, has been shown to decrease retinal ICAM‐1 and VEGF expression in diabetic retina, leading to reduction in leucocyte adhesion, endothelial cell injury and blood–retinal barrier breakdown.39 Ang‐1 also significantly reduced VEGF‐induced retinal vascular permeability and neovascularisation.40,41

In the present study, there was no immunoreactivity for the antiangiogenic PEDF in PDR membranes. This is in agreement with studies showing that the retinal and intraocular PEDF levels, in contrast to that of VEGF, are negatively correlated with pathological retinal neovascularisation.5,42 Several studies demonstrated increased levels of Epo in the vitreous fluid from patients with PDR as compared with patients without diabetes.16,43,44 In the present study, there was no immunoreactivity for Epo in PDR membranes. These findings suggest that increased Epo levels that were previously reported in the vitreous fluid from patients with PDR16,43,44 were probably due to increased local production in the ischaemic retina.16

In conclusion, the present data suggest production of HIF‐1α, VEGF and Ang‐2 by vascular endothelial cells in PDR membranes, and the local autocrine action of these proteins in stimulating angiogenesis. Selective expression of HIF‐1α, Ang‐2 and VEGF, but not Ang‐1 and PEDF, may favour aberrant neovascularisation and endothelial abnormalities. Clinically, manipulating the HIF‐1α pathway in the treatment of diabetic retinopathy might be an attractive choice in comparison to targeting VEGF and other growth factors that localise downstream. It has been demonstrated that the HIF‐1α pathway can be used as a therapeutic target for development of novel cancer therapeutics.45

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr Dustan Kangave, MSc, for statistical assistance, Mr Johan Van Even and Ms Christel Van den Broeck for technical assistance, and Ms Connie B Unisa‐Marfil for secretarial work. This work was supported by the College of Medicine Research Center, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Abbreviations

Ang - angiopoietin

Epo - erythropoietin

HIF‐1α - hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1α

ICAM‐1 - intercellular adhesion molecule‐1

PEDF - pigment epithelium‐derived factor

PDR - proliferative diabetic retinopathy

VEGF - vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Ferrara N. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in regulation of physiological angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001280C1358–C1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson D W, Volpert O V, Gillis P.et al Pigment epithelium‐derived factor: a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science 1999285245–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiello L P, Avery R L, Arrigg P G.et al Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med 19943311480–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamis A P, Miller J W, Bernal M T.et al Increased vascular endothelial growth factor levels in the vitreous of eyes with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1994118445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spranger J, Osterhoff M, Reimann M.et al Loss of the antiangiogenic pigment epithelium‐derived factor in patients with angiogenic eye disease. Diabetes 2001502641–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joussen A M, Poulaki V, Le M L.et al A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J 2004181450–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang B H, Semenza G L, Bauer C.et al Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 levels vary exponentially over a physiologically relevant range of O2 tension. Am J Physiol 1996271C1172–C1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G L, Jiang B H, Rue E A.et al Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 is a basic‐helix‐loop‐helix PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995925510–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang L E, Gu J, Schau M.et al Regulation of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 alpha is mediated by an O2‐dependent degradation domain via the ubiquitin‐proteasome pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998957987–7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirota K, Semenza G L. Regulation of angiogenesis by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 20065915–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunn H F, Gu J, Huang L E.et al Erythropoietin: a model system for studying oxygen‐dependent gene regulation. J Exp Biol 19982011197–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsythe J A, Jiang B H, Iyer N V.et al Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 1996164604–4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamakawa M, Liu L X, Date T.et al Hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 mediates activation of cultured vascular endothelial cells by inducing multiple angiogenic factors. Circ Res 200393664–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jelkmann W. Molecular biology of erythropoietin. Int Med 200443649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaquet K, Krause K, Tawakol‐Khodai M.et al Erythropoietin and VEGF exhibit equal angiogenic potential. Microvasc Res 200264326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe D, Suzuma K, Matsui S.et al Erythropoietin as a retinal angiogenic factor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med 2005353782–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yancopoulos G D, Davis S, Gale N W.et al Vascular‐specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature (London) 2000407242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lobov I B, Brooks P C, Lang R A. Angiopoietin‐2 displays VEGF‐dependent modulation of capillary structure and endothelial cell survival in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 20029911205–11210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Simopoulos C.et al Hypoxia inducible factors 1 alpha and 2 alpha are associated with VEGF expression and angiogenesis in gall bladder carcinomas. J Surg Oncol 200694242–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivridis E, Giatromanolaki A, Gatter K C.et al Association of hypoxia‐inducible factors 1 alpha and 2 alpha with activated angiogenic pathways and prognosis in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Cancer 2002951055–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuwai T, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S.et al Expression of hypoxia‐inducible‐1 alpha is associated with tumor vascularization in human colorectal carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2003105176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Theodoropoulos V E, Lazaris A C H, Sofras F.et al Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 alpha expression correlates with angiogenesis and unfavorable prognosis in bladder cancer. Eur Urol 200446200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung F, Haendeler J, Hofmann J.et al Hypoxic induction of the hypoxia‐inducible factor is mediated via the adaptor protein Shc in endothelial cells. Circ Res 20029138–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson J, Shibuya M, Wennstrom S. Differential activation of vascular genes by hypoxia in primary endothelial cells. Exp Cell Res 2004299476–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu A Y, Frid M G, Shimoda L A.et al Temporal, spatial, and oxygen‐regulated expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 in the lung. Lung Cell Mol Physiol 199819L818–L826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chavez J C, Almhanna K, Berti‐Mattera L N. Transient expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 alpha and target genes in peripheral nerves from diabetic rats. Neurosci Lett 2005374179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandriota S J, Pyke C, Di Sanza C.et al Hypoxia‐inducible angiopoietin‐2 expression is mimicked by iodonium compounds and occurs in the rat brain and skin in response to systemic hypoxia and tissue ischemia. Am J Pathol 20001562077–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh H, Takagi H, Suzuma K.et al Hypoxia and vascular endothelial growth factor selectively up‐regulate angiopoietin‐2 in bovine microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 199927415732–15739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu Y, Lee C, Shen F.et al Angiopoietin‐2 facilitates vascular endothelial growth factor‐induced angiogenesis in the mature mouse brain. Stroke 2005361533–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka F, Ishikawa S, Yanagihara K.et al Expression of angiopoietins and its clinical significance in non‐small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res 2002627124–7129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsutsui S, Inoue H, Yasuda K.et al Angiopoietin 2 expression in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: its relationship to the VEGF expression and microvessel density. Breast Cancer Res Treat 200698261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Yang N, Park J ‐ W.et al Tumor‐derived vascular endothelial growth factor up‐regulates angiopoietin‐2 in host endothelium and destabilizes host vasculature, supporting angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 2003633403–3412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Umeda N, Ozaki H, Yayashi H.et al Colocalization of the Tie 2, angiopoietin‐2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in fibrovascular membrane from patients with retinopathy of prematurity. Ophthalmic Res 200335217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takagi H, Koyama S, Seike H.et al Potential role of the angiopoietin/tie 2 system in ischemia‐induced retinal neovascularization. Invest J Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200344393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohashi H, Takagi H, Koyama S.et al Alterations in expression of angiopoietins and the tie‐2 receptor in the retina of streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Mol Vision 200410608–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe D, Suzuma K, Suzuma I.et al Vitreous levels of angiopoietin 2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2005139476–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lemieux C, Maliba R, Favier J.et al Angiopoietins can directly activate endothelial cells and neutrophils to promote proinflammatory responses. Blood 20051051523–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joussen A M, Poulaki V, Qin W.et al Retinal vascular endothelial growth factor induces intercellular adhesion molecule‐1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and initiates early diabetic retinal leukocyte adhesion in vivo. Am J Pathol 2002160501–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joussen A M, Poulaki V, Tsujikawa A.et al Suppression of diabetic retinopathy with angiopoietin‐1. Am J Pathol 20021601683–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nambu H, Umda N, Kachi S.et al Angiopoietin 1 prevents retinal detachment in an aggressive model of proliferative retinopathy, but has no effect on established neovascularization. J Cell Physiol 2005204227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nambu H, Nambu R, Oshima Y.et al Angiopoietin1 inhibits ocular neovascularization and breakdown of the blood‐retinal barrier. Gene Ther 200411865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao G, Li Y, Zhang D.et al Unbalanced expression of VEGF and PEDF in ischemia‐induced retinal neovascularization. FEBS Lett 2001489270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katsura Y, Okano T, Matsuno K.et al Erythropoietin is highly elevated in vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2005282252–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inomata Y, Hirata A, Takahashi E.et al Elevated erythropoietin in vitreous with ischemic retinal diseases. Neuroreport 200415877–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones D T, Harris A L. Identification of novel small‐molecule inhibitors of hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 transactivation and DNA binding. Mol Cancer Ther 200652193–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]